Synergistic Effect of Combination of Various Microbial Hurdles in the Biopreservation of Meat and Meat Products—Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

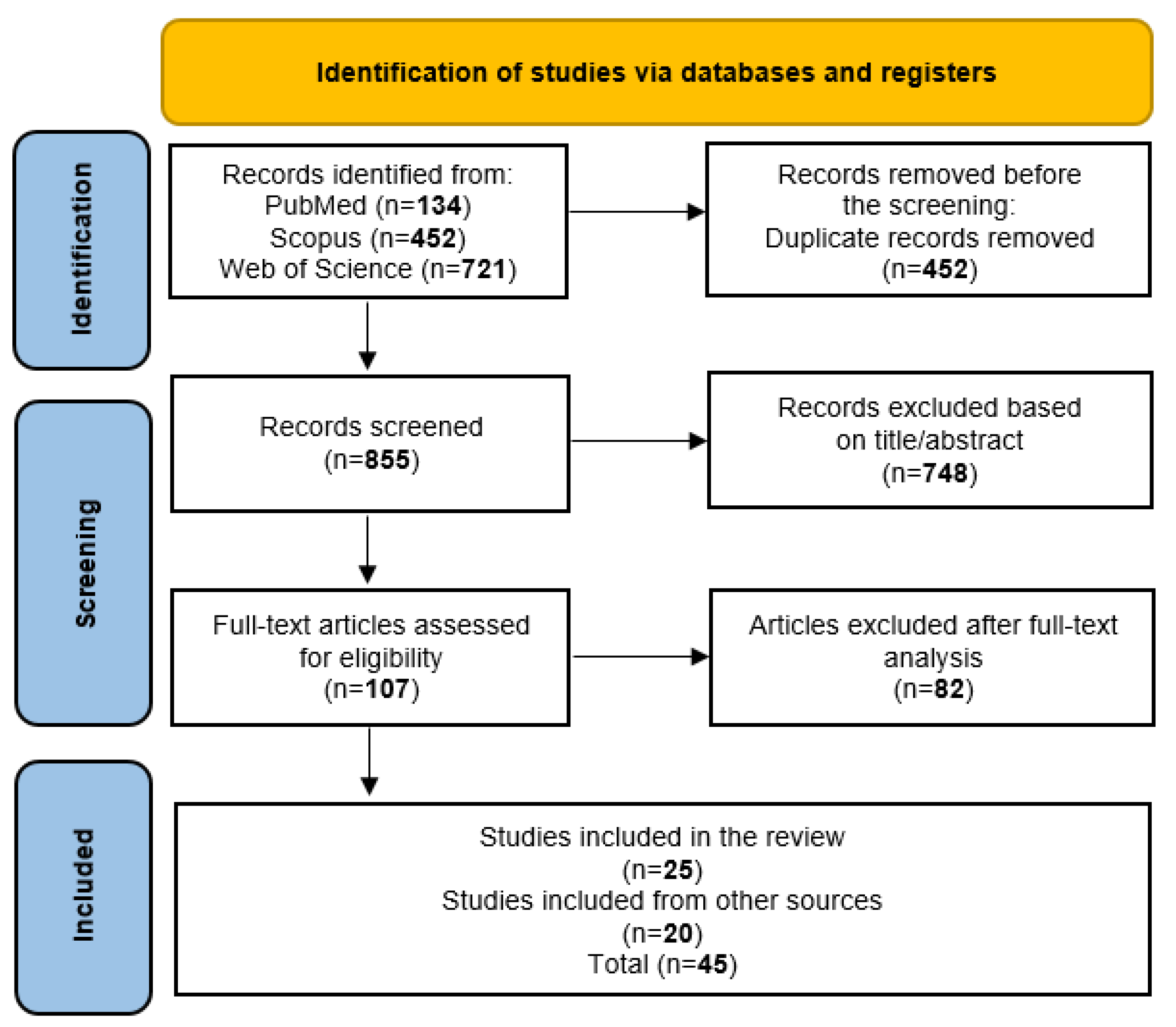

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focus Question

2.2. Protocol and Selection Criteria

2.3. Search Methods

2.4. Selection of Articles

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Search for Heterogeneity

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Risk of Bias

3.3. Main Findings

4. Discussion

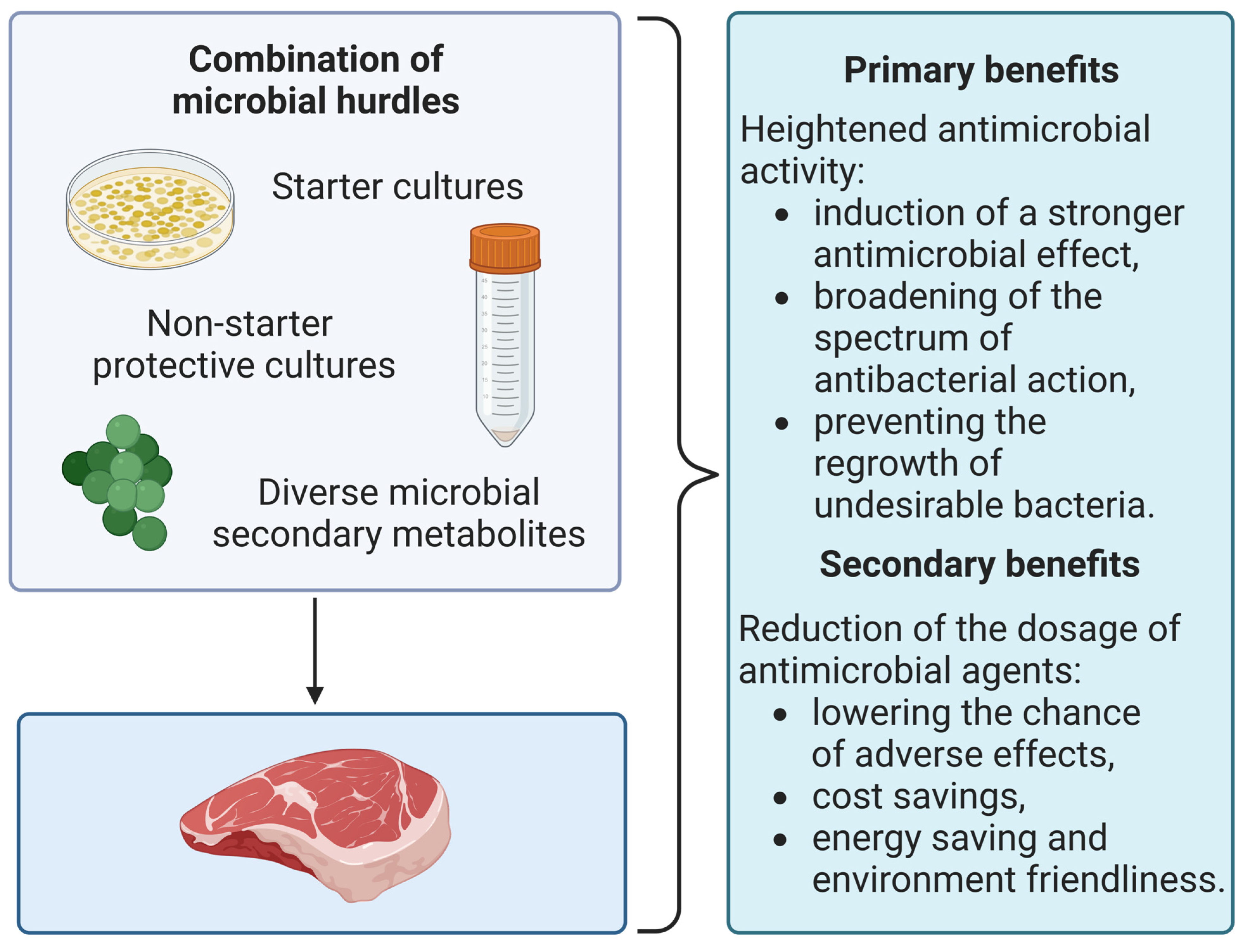

4.1. Combination of Various Microbial Hurdles against Foodborne Pathogens and Spoilage Microorganisms in Meat and Meat Products

4.1.1. Combination of Starter Cultures

| Mixture | Meat System | Target Microorganism(s) | Synergism Occurrence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starter cultures of Latilactobacillus sakei and Staphylococcus equorum | Traditional fermented sausages of Basilicata region | LAB, CNS, Enterobacteriaceae, gram-negative bacteria, molds, and yeasts | Yes | Bonomo et al. (2011) [30] |

| Starter cultures of Staphylococcus xylosus CVS11 or FVS21 with Latilactobacillus curvatus | Fermented sausages | Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococci, molds, yeast, LAB, and Micrococcaceae | Yes | Casaburi et al. (2007) [31] |

| Starter cultures of Pediococcus acidilactici (MC184, MS198, or MS200) and Staphylococcus vitulus RS34 | Traditional Iberian dry-fermented salchichón and chorizo | Various pathogens (Listeria, Salmonella, E. coli, S. aureus), Enterobacteriaceae, and Micrococcus | Yes | Casquete, et al. (2012) [32] |

| Starter cultures of Staphylococcus xylosus SX16 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum CMRC6 | Gourmet fermented dry sausage | LAB, CNS, and Enterobacteriaceae | Yes, but only concerning Enterobacteriaceae | Chen et al. (2020) [33] |

| Starter cultures of Pediococcus pentosaceus and Staphylococcus xylosus | Xiangxi sausages | TVC, LAB, Staphylococcus, and Enterobacteriaceae | No significant difference with the control sample | Du et al. (2019) [34] |

| Autochthonous starter culture of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 1K and Staphylococcus carnosus 4K1 | Traditional Croatian dry sausages | L. monocytogenes, Salmonella ssp., S. aureus, E. coli, Enterobacteriaceae, yeasts, and molds | Yes | Frece et al. (2014) [35] |

| Two starter cultures of Lyocarni BOX-74 (Carnobacterium divergens, Carnobacterium maltaromaticum, and Latilactobacillus sakei) and Lyocarni BOX-57 (Carnobacterium divergens, Carnobacterium maltaromaticum, and Latilactobacillus sakei bacteriocin producers) | Cooked cubed pork ham | LAB, L. monocytogenes, TVC | Yes | Iacumin et al. (2020) [36] |

| Two starter cultures of the mix of Pediococcus acidilactici, Latilactobacillus curvatus + Staphylococcus xylosus, and Latilactobacillus sakei + Staphylococcus carnosus | Sucuk, Turkish dry-fermented sausage | S. aureus, LAB, Micrococcus/Staphylococcus, Enterobacteriaceae | Yes | Kaban et al. (2006) [37] |

| Two starter cultures of the mix of Staphylococcus xylosus DD-34, Pediococcus acidilactici PA-2 + Latilactobacillus bavaricus MI-401, and S. carnosus MIII + Latilactobacillus curvatus Lb3 | Dry sausage | Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes | Yes | Lahti et al. (2001) [38] |

| Starter cultures of Lactobacillus spp., Leuconostoc spp., Lactococcus spp., Pediococcus spp., and Weissella spp. | Fermented sausages | TVC, yeast mold, and LAB | Yes, but no significant difference with the commercial LAB starter culture used as a control sample | Lee et al. (2018) [39] |

| Starter culture of Latilactobacillus sakei, Staphylococcus xylosus, and Staphylococcus carnosus | Meat sausages | Escherichia coli ATCC25922, Salmonella Enteritidis ATCC13076, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC43300, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC29212, and Listeria monocytogenes CERELA | Yes | Mafra et al. (2020) [40] |

| Starter culture of Pediococcus pentosaceus and Staphylococcus carnosus with co-cultures of Limosilactobacillus reuteri and Bifidobacterium longum | Dry fermented sausages | Escherichia coli O157:H7 | Yes | Muthukumarasamy & Holley (2007) [41] |

| Starter culture of Latilactobacillus sakei (23K, BMG 95, or BMG 37) and Staphylococcus xylosus | Tunisian dry-fermented sausages | S. aureus, Salmonella spp., total coliforms, LAB, anaerobic sulphate-reducing bacteria, yeast, and molds | Yes | Najjari et al. (2021) [42] |

| Starter culture of Pediococcus pentosaceus LIV 01 and P. acidilactici FLE 01 | Sliced fresh beef | Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus, yeasts, molds, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella Typhimurium | Yes | Olaoye et al. (2010) [43] |

| Starter culture of Pediococcus pentosaceus GOAT 01 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum GOAT 012 | Goat meat | Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus, yeasts, molds, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella Typhimurium | Yes, but no significant difference with the control sample concerning yeast and mold counts | Olaoye et al. (2011) [44] |

| Starter cultures of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis I23 (Llac01) and Lactococcus lactis subsp. hordinae E91 (Llac02) | Pork meat | Brochothrix thermosphata | Yes | Olaoye et al. (2015) [45] |

| Starter cultures of Pediococcus pentosaceus and Staphylococcus carnosus with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum L125 | Traditional Greek dry-fermented sausage | Pseudomonas spp., Brochothrix spp., Enterobacteriaceae, yeasts, molds, and Listeria monocytogenes | Yes | Pavli et al. (2020) [46] |

| Commercial starter culture (FloraCarn) consisting of a mixture of Pediococcus pentosaceus and Staphylococcus xylosus in combination with a non-traditional meat starter culture of dairy or human intestinal origin | Hungarian salami | Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli O111 | Yes | Pidcock et al. (2002) [47] |

| Starter culture of Staphylococcus xylosus and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | Harbin dry sausage | TVC, LAB, and Enterobacteriaceae | Yes, but only concerning Enterobacteriaceae | Sun et al. (2016) [48] |

| Starter culture of Staphylococcus xylosus and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | Harbin dry sausage | TVC, LAB, and Enterobacteriaceae | Yes | Sun et al. (2019) [49] |

| Starter cultures of Limosilactobacillus fermentum S8 and Staphylococcus carnosus ATCC 51365 | Canned minced pork meat | TVC, LAB, Staphylococcus | Yes | Szymański et al. (2021) [50] |

| Starter cultures of diverse mix of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum CP1-15, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum CP2-11 and Pediococcus acidilactici CP7-3 | Thai fermented sausage “Sai-Krok-Prew” | LAB, E. coli, Salmonella, total staphylococci, and S. aureus | Yes | Vatanyoopaisarn et al. (2011) [51] |

| Starter culture of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum R2 and Staphylococcus xylosus A2 | Chinese dry fermented sausages | TVC, LAB, and Staphylococcus spp. | Yes | Xiao et al. (2020) [52] |

| Starter culture of Lactiplantibacillus pentosus, Pediococcus pentosaceus and Staphylococcus carnosus | Mutton sausages | LAB, TVC, micrococci–staphylococci | Yes | Zhao et al. (2011) [53] |

4.1.2. Combination of Non-Starter Protective Cultures

| Mixture | Meat System | Target Microorganism(s) | Synergism Occurrence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supernatants from Pediococcus acidilactici, Lacticaseibacillus casei, and Lacticaseibacillus paracasei | Frankfurters and cooked ham | L. monocytogenes | No significant difference with the control sample | Amézquita & Brashears (2002) [54] |

| Cultures of bacteriocin-producing strains of Latilactobacillus curvatus CRL705 and Lactococcus lactis CRL1109 | Frozen ground-beef patties | Escherichia coli O157:H7 | Yes | Castellano et al. (2011) [55] |

| Six strain combinations containing three different strains of Latilactobacillus sakei | Vacuum-packed or modified atmosphere-packed ground beef | Salmonella enterica Typhimurium, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Brochothrix thermosphacta | The growth of indicator strains was variable and depended on both the storage conditions and the amount of indigenous microbiota | Chaillou et al. (2014) [56] |

| Neutralized cell-free supernatants from Latilactobacillus sakei CWBI-B1365 and Latilactobacillus curvatus CWBI-B28 | Raw beef and poultry meat | Listeria monocytogenes | Yes | Dortu et al. (2008) [57] |

| Cultures of Lactobacillus acidophilus LA5, Lacticaseibacillus casei 01 and Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus HN001 | Marinated meat | L. monocytogenes, E. coli O157:H7, and S. Typhimurium | No | Gargi et al. (2021) [58] |

| Postbiotics from Latilactobacillus sakei and Staphylococcus xylosus | Chicken drumsticks | Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella Typhimurium, TVC, psychrotrophic bacteria, and LAB | Yes | Incili et al. (2022) [59] |

| Latilactobacillus sakei 27, 44 and 63 strains | Lamb meat | General anaerobic bacteria | Yes | Jones et al. (2010) [60] |

| Latilactobacillus sakei CECT 4808, and Latilactobacillus curvatus CECT 904T | Vacuum-packaged sliced beef | Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp., Brochothrix thermosphacta, yeasts and molds, and LAB | No | Katikou et al. (2005) [61] |

| Three LAB strains (Lactiguard®)—La51 (Ligilactobacillus), M35 (Lactobacillus amylovorus), and D3 (Pediococcus acidilactici) in combination with their CFS | Frankfurters | Listeria monocytogenes | Yes | Koo et al. (2012) [62] |

| Supernatants from Lactobacillus acidophilus CRL641 and Latilactobacillus curvatus CRL705 | Bovine meat discs | Latilactobacillus sakei CRL1407 (exopolysaccharide producer) | Yes | Segli et al. (2021a) [63] |

| Supernatants from Lactobacillus acidophilus CRL641 and Latilactobacillus curvatus CRL705 | Bovine fresh lean meat | Latilactobacillus sakei CRL1407 (exopolysaccharide producer) | No | Segli et al. (2021b) [64] |

| Latilactobacillus sakei, Pediococcus pentosaceus, Staphylococcus xylosus, and Staphylococcus carnosus in various combinations | Lamb meat | Brochothrix thermosphacta, Pseudomonas spp., and Enterobacteriaceae | Yes | Xu et al. (2021) [65] |

| Mixed culture containing Staphylococcus carnosus and Latilactobacillus sakei | Beef mince | Aerobic counts, LAB, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp., Brochothrix thermosphacta | Yes | Xu et al. (2023) [66] |

4.1.3. Combination of a Variety of Secondary Microbial Metabolites

Combination of Bacteriocins

| Mixture | Meat System | Target Microorganism(s) | Synergism Occurrence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriocins from Latilactobacillus curvatus and Latilactobacillus sakei, in combination with nisin | Frankfurters | L. monocytogenes and psychrophilic microbiota | Yes | Castellano et al. (2018) [70] |

| Bacteriocins nisin, lactocin 705, and enterocin CRL35 in combinations | Fresh lean meat | Listeria monocytogenes FBUNT | Yes | Vignolo et al. (2000) [71] |

Combination of BLIS with Bacteriocin

| Mixture | Meat System | Target Microorganism(s) | Synergism Occurrence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriocin-like substance (BLIS) from Bacillus sp. strain P34 and nisin | Chicken sausage | Listeria monocytogenes | Yes | Sant’Anna et al. (2013) [72] |

Combination of Non-Starter Protective Cultures with Bacteriocins

| Mixture | Meat System | Target Microorganism(s) | Synergism Occurrence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nisin with neutralized cell-free supernatant obtained from Pediococcus pentosaceus ATCC 43,200 | Pork meat | Latilactobacillus sakei ATCC 15521 | No | de Souza de Azevedo et al. (2019) [68] |

| Latilactobacillus sakei C2 and sakacin C2 | Sliced cooked pork ham | L. monocytogenes CMCC 54002 | Yes | Gao et al. (2015) [67] |

Combination of Reuterin with Bacteriocin

| Mixture | Meat System | Target Microorganism(s) | Synergism Occurrence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reuterin (produced by Limosilactobacillus reuteri) and microcin J25 (produced by E. coli MC4100) | Chicken carcasses | The mixture of Salmonella Enteritidis, Salmonella Heidelberg, Salmonella Newport, and TVC | Yes | Zhang et al. (2021) [74] |

Combination of the Surface Layer Protein (S-Layer Protein/SLP) with Bacteriocin

| Mixture | Meat System | Target Microorganism(s) | Synergism Occurrence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface layer protein isolated from Lactobacillus crispatus K313 (SLP) and nisin | Minced chicken meat | Staphylococcus saprophyticus P2 | Yes | Sun et al. (2017) [73] |

Combination of PgAFP with Protective Cultures

| Mixture | Meat System | Target Microorganism(s) | Synergism Occurrence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small, basic, cysteine-rich antifungal protein PgAFP from Penicillium chrysogenum combined with Debaryomyces hansenii and/or Pediococcus acidilactic | Dry-fermented sausage | Mold, yeast, LAB, aflatoxin B1, and aflatoxin G1 | Yes | Delgado et al. (2018) [69] |

4.2. Mode of Synergistic Action

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- European Food Safety Authority; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union One Health 2021 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Possible Multistate Enteric (Intestinal) Disease Outbreaks in 2017–2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/outbreaks/multistate-outbreaks/annual-summaries/annual-summaries-2017-2020.html (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Bohrer, B.M. Review: Nutrient density and nutritional value of meat products and non-meat foods high in protein. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 65, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doulgeraki, A.I.; Ercolini, D.; Villani, F.; Nychas, G.-J.E. Spoilage microbiota associated to the storage of raw meat in different conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 157, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Jiménez-Colmenero, F.; Sánchez-Muniz, F.J. Development and assessment of healthy properties of meat and meat products designed as functional foods. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gardini, F.; Özogul, Y.; Suzzi, G.; Tabanelli, G.; Özogul, F. Technological Factors Affecting Biogenic Amine Content in Foods: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ockerman, H.W.; Basu, L. Preservation Methods of Animal Products. In Encyclopedia of Meat Sciences; Elsevier: London, UK, 2014; pp. 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mani-López, E.; Palou, E.; López-Malo, A. Biopreservatives as Agents to Prevent Food Spoilage. In Microbial Contamination and Food Degradation; Elsevier: London, UK, 2018; pp. 235–270. [Google Scholar]

- Barcenilla, C.; Ducic, M.; López, M.; Prieto, M.; Álvarez-Ordóñez, A. Application of lactic acid bacteria for the biopreservation of meat products: A systematic review. Meat Sci. 2022, 183, 108661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.P. Recent approaches in food bio-preservation—A review. Open Vet. J. 2018, 8, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Microorganisms & Microbial-Derived Ingredients Used in Food (Partial List). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/generally-recognized-safe-gras/microorganisms-microbial-derived-ingredients-used-food-partial-list (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- European Food Safety Authority. Management Board Members; Executive Director; Operational Management. Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS). Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/qualified-presumption-safety-qps (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Gorris, L.G.M. Hurdle Technology. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology; Elsevier: London, UK, 2014; pp. 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Nie, R.; Liu, Y.; Mehmood, A. Combined antimicrobial effect of bacteriocins with other hurdles of physicochemic and microbiome to prolong shelf life of food: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 154058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gragg, S.; Brashears, M. Microbiological Safety of Meat|Hurdle Technology. In Encyclopedia of Meat Sciences; Elsevier: London, UK, 2014; pp. 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Braïek, O.; Smaoui, S. Chemistry, Safety, and Challenges of the Use of Organic Acids and Their Derivative Salts in Meat Preservation. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 6653190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielski, G.M.; Evangelista, A.G.; Luciano, F.B.; de Macedo, R.E.F. Non-conventional cultures and metabolism-derived compounds for bioprotection of meat and meat products: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laranjo, M.; Potes, M.E.; Elias, M. Role of Starter Cultures on the Safety of Fermented Meat Products. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martín, I.; Rodríguez, A.; Delgado, J.; Córdoba, J.J. Strategies for Biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes Using Lactic Acid Bacteria and Their Metabolites in Ready-to-Eat Meat- and Dairy-Ripened Products. Foods 2022, 11, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosario, D.K.A.; Rodrigues, B.L.; Bernardes, P.C.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Principles and applications of non-thermal technologies and alternative chemical compounds in meat and fish. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1163–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.; Domingues, F.C.; Nerín, C. Trends in microbial control techniques for poultry products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, I.; Wilhelm, B.J.; Cahill, S.; Nakagawa, R.; Desmarchelier, P.; Rajić, A. A Rapid Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Slaughter and Processing Interventions to Control Nontyphoidal Salmonella in Beef and Pork. J. Food Prot. 2016, 79, 2196–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, H.H.; Chin, Y.-W.; Paik, H.-D. Application of Natural Preservatives for Meat and Meat Products against Food-Borne Pathogens and Spoilage Bacteria: A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration for Environmental Evidence. CEE Critical Appraisal Tool—Environmental Evidence. Available online: https://environmentalevidence.org/cee-critical-appraisal-tool/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sato, H.; Kawaguti, H. (Eds.) Biotechnological Production of Organic Acids. In Biotechnological Production of Natural Ingredients for Food Industry; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2016; pp. 164–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bramer, W.M.; De Jonge, G.B.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Mast, F.; Kleijnen, J. A systematic approach to searching: An efficient and complete method to develop literature searches. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018, 106, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, M.G.; Ricciardi, A.; Salzano, G. Influence of autochthonous starter cultures on microbial dynamics and chemical-physical features of traditional fermented sausages of Basilicata region. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaburi, A.; Aristoy, M.-C.; Cavella, S.; DI Monaco, R.; Ercolini, D.; Toldrá, F.; Villani, F. Biochemical and sensory characteristics of traditional fermented sausages of Vallo di Diano (Southern Italy) as affected by the use of starter cultures. Meat Sci. 2007, 76, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casquete, R.; Benito, M.J.; Martín, A.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Aranda, E.; Cordoba, M.D.G. Microbiological quality of salchichón and chorizo, traditional Iberian dry-fermented sausages from two different industries, inoculated with autochthonous starter cultures. Food Control 2012, 24, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mi, R.; Qi, B.; Xiong, S.; Li, J.; Qu, C.; Qiao, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, S. Effect of proteolytic starter culture isolated from Chinese Dong fermented pork (Nanx Wudl) on microbiological, biochemical and organoleptic attributes in dry fermented sausages. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2021, 10, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Cheng, H.; Ma, J.-K.; Li, Z.-J.; Wang, C.-H.; Wang, Y.-L. Effect of starter culture on microbiological, physiochemical and nutrition quality of Xiangxi sausage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frece, J.; Kovačević, D.; Kazazić, S.; Mrvčić, J.; Vahčić, N.; Ježek, D.; Hruškar, M.; Babić, I.; Markov, K. Comparison of Sensory Properties, Shelf-Life and Microbiological Safety of Industrial Sausages Produced with Autochthonous and Commercial Starter Cultures. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2014, 52, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Iacumin, L.; Cappellari, G.; Colautti, A.; Comi, G. Listeria monocytogenes Survey in Cubed Cooked Ham Packaged in Modified Atmosphere and Bioprotective Effect of Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaban, G.; Kaya, M. Effect of starter culture on growth of Staphylococcus aureus in sucuk. Food Control 2006, 17, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, E.T.; Johansson, T.; Honkanen-Buzalski, T.; Hill, P.; Nurmi, E. Survival and detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Listeria monocytogenes during the manufacture of dry sausage using two different starter cultures. Food Microbiol. 2001, 18, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, O.Y.; Hur, S.J. Analysis for change in microbial contents in five mixed Kimchi starter culture and commercial lactic acid bacterial-fermented sausages and biological hazard in manufacturing facilities. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 28, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafra, J.F.; Cruz, A.I.C.; de Santana, T.S.; Ferreira, M.A.; Araújo, F.M.; Evangelista-Barreto, N.S. Probiotic characterization of a commercial starter culture used in the fermentation of sausages. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumarasamy, P.; Holley, R.A. Survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in dry fermented sausages containing micro-encapsulated probiotic lactic acid bacteria. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjari, A.; Boumaiza, M.; Jaballah, S.; Boudabous, A.; Ouzari, H. Application of isolated Lactobacillus sakei and Staphylococcus xylosus strains as a probiotic starter culture during the industrial manufacture of Tunisian dry-fermented sausages. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 4172–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaoye, O.A.; Onilude, A.A. Investigation on the potential application of biological agents in the extension of shelf life of fresh beef in Nigeria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaoye, O.A.; Onilude, A.A.; Idowu, O.A. Microbiological Profile of Goat Meat Inoculated with Lactic Acid Bacteria Cultures and Stored at 30 °C for 7 days. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2011, 4, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaoye, O.; Onilude, A.; Ubbor, S.C. Control of Brochothrix thermosphacta in Pork Meat Using Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis I23 Isolated from Beef. Appl. Food Biotechnol. 2015, 2, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavli, F.G.; Argyri, A.A.; Chorianopoulos, N.G.; Nychas, G.-J.E.; Tassou, C.C. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum L125 strain with probiotic potential on physicochemical, microbiological and sensorial characteristics of dry-fermented sausages. Lebenson. Wiss. Technol. 2020, 118, 108810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidcock, K.; Heard, G.; Henriksson, A. Application of nontraditional meat starter cultures in production of Hungarian salami. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 76, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Chen, Q.; Li, F.; Zheng, D.; Kong, B. Biogenic amine inhibition and quality protection of Harbin dry sausages by inoculation with Staphylococcus xylosus and Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Control 2016, 68, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Sun, F.; Zheng, D.; Kong, B.; Liu, Q. Complex starter culture combined with vacuum packaging reduces biogenic amine formation and delays the quality deterioration of dry sausage during storage. Food Control 2019, 100, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymański, P.; Łaszkiewicz, B.; Kern-Jędrychowska, A.; Siekierko, U.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. The Use of the Mixed Bacteria Limosilactobacillus fermentum and Staphylococcus carnosus in the Meat Curing Process with a Reduced Amount of Sodium Nitrite. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanyoopaisarn, S.; Prapatsornwattana, K. Potential use of lactic acid bacteria with bacteriocin-like activity against Staph-ylococcus aureus as dual starter cultures in Thai fermented sausage “Sai Krok Prew”. Int. Food Res. J. 2011, 18, 697–704. Available online: http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my/18%20(02)%202011/(32)%20IFRJ-2010-238.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Xie, T.; Li, P. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum and Staphylococcus xylosus on flavour development and bacterial communities in Chinese dry fermented sausages. Food Res. Int. 2020, 135, 109247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Jin, Y.; Ma, C.; Song, H.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, S. Physico-chemical characteristics and free fatty acid composition of dry fermented mutton sausages as affected by the use of various combinations of starter cultures and spices. Meat Sci. 2011, 88, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amézquita, A.; Brashears, M.M. Competitive Inhibition of Listeria Monocytogenes in Ready-to-Eat Meat Products by Lactic Acid Bacteria. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, P.; Belfiore, C.; Vignolo, G. Combination of bioprotective cultures with EDTA to reduce Escherichia coli O157:H7 in frozen ground-beef patties. Food Control 2011, 22, 1461–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaillou, S.; Christieans, S.; Rivollier, M.; Lucquin, I.; Champomier-Vergès, M.; Zagorec, M. Quantification and efficiency of Lactobacillus sakei strain mixtures used as protective cultures in ground beef. Meat Sci. 2014, 97, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dortu, C.; Huch, M.; Holzapfel, W.; Franz, C.; Thonart, P. Anti-listerial activity of bacteriocin-producing Lactobacillus curvatus CWBI-B28 and Lactobacillus sakei CWBI-B1365 on raw beef and poultry meat. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 47, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargi, A.; Sengun, I.Y. Marination liquids enriched with probiotics and their inactivation effects against food-borne pathogens inoculated on meat. Meat Sci. 2021, 182, 108624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incili, G.K.; Karatepe, P.; Akgöl, M.; Güngören, A.; Koluman, A.; Ilhak, O.I.; Kanmaz, H.; Kaya, B.; Hayaloğlu, A.A. Characterization of lactic acid bacteria postbiotics, evaluation in-vitro antibacterial effect, microbial and chemical quality on chicken drumsticks. Food Microbiol. 2022, 104, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Wiklund, E.; Zagorec, M.; Tagg, J. Evaluation of stored lamb bio-preserved using a three-strain cocktail of Lactobacillus sakei. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katikou, P.; Ambrosiadis, I.; Georgantelis, D.; Koidis, P.; Georgakis, S. Effect of Lactobacillus-protective cultures with bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances’ producing ability on microbiological, chemical and sensory changes during storage of refrigerated vacuum-packaged sliced beef. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, O.-K.; Eggleton, M.; O’Bryan, C.A.; Crandall, P.G.; Ricke, S.C. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria against Listeria monocytogenes on frankfurters formulated with and without lactate/diacetate. Meat Sci. 2012, 92, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segli, F.; Melian, C.; Muñoz, V.; Vignolo, G.; Castellano, P. Bioprotective extracts from Lactobacillus acidophilus CRL641 and Latilactobacillus curvatus CRL705 inhibit a spoilage exopolysaccharide producer in a refrigerated meat system. Food Microbiol. 2021, 97, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segli, F.; Melian, C.; Vignolo, G.; Castellano, P. Inhibition of a spoilage exopolysaccharide producer by bioprotective extracts from Lactobacillus acidophilus CRL641 and Latilactobacillus curvatus CRL705 in vacuum-packaged refrigerated meat discs. Meat Sci. 2021, 178, 108509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.M.; Kaur, M.; Pillidge, C.J.; Torley, P.J. Evaluation of the potential of protective cultures to extend the microbial shelf-life of chilled lamb meat. Meat Sci. 2021, 181, 108613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.M.; Kaur, M.; Pillidge, C.J.; Torley, P.J. Culture-Dependent and Culture-Independent Evaluation of the Effect of Protective Cultures on Spoilage-Related Bacteria in Vacuum-Packaged Beef Mince. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, X. Effects of Lactobacillus sakei C2 and sakacin C2 individually or in combination on the growth of Listeria monocytogenes, chemical and odor changes of vacuum-packed sliced cooked ham. Food Control 2015, 47, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, P.O.D.S.D.; Converti, A.; Gierus, M.; Oliveira, R.P.D.S. Application of nisin as biopreservative of pork meat by dipping and spraying methods. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2019, 50, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.; Rodríguez, A.; García, A.; Núñez, F.; Asensio, M.A. Inhibitory Effect of PgAFP and Protective Cultures on Aspergillus parasiticus Growth and Aflatoxins Production on Dry-Fermented Sausage and Cheese. Microorganisms 2018, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castellano, P.; Peña, N.; Ibarreche, M.P.; Carduza, F.; Soteras, T.; Vignolo, G. Antilisterial efficacy of Lactobacillus bacteriocins and organic acids on frankfurters. Impact on sensory characteristics. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignolo, G.; Palacios, J.; Farías, M.E.; Sesma, F.; Schillinger, U.; Holzapfel, W.; Oliver, G. Combined effect of bacteriocins on the survival of various Listeria species in broth and meat system. Curr. Microbiol. 2000, 41, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna, V.; Quadros, D.A.; Motta, A.S.; Brandelli, A. Antibacterial activity of bacteriocin-like substance P34 on Listeria monocytogenes in chicken sausage. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 1163–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, Z.; Li, P.; Liu, F.; Bian, H.; Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Zou, Y.; Sun, C.; Xu, W. Synergistic antibacterial mechanism of the Lactobacillus crispatus surface layer protein and nisin on Staphylococcus saprophyticus. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Ben Said, L.; Diarra, M.S.; Fliss, I. Inhibitory Activity of Natural Synergetic Antimicrobial Consortia against Salmonella enterica on Broiler Chicken Carcasses. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 656956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Díez, J.; Saraiva, C. Use of Starter Cultures in Foods from Animal Origin to Improve Their Safety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignolo, G.; Fontana, C.; Fadda, S. Semidry and Dry Fermented Sausages. In Handbook of Meat Processing; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 379–398. [Google Scholar]

- Krockel, L. The Role of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Safety and Flavour Development of Meat and Meat Products. In Lactic Acid Bacteria—R & D for Food, Health and Livestock Purposes; Kongo, M., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laranjo, M.; Elias, M.; Fraqueza, M.J. The Use of Starter Cultures in Traditional Meat Products. J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 9546026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Landeta, G.; Curiel, J.A.; Carrascosa, A.V.; Muñoz, R.; de Las Rivas, B. Characterization of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from Spanish dry cured meat products. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Flores, M.; Toldrá, F. Microbial enzymatic activities for improved fermented meats. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiling, L.; Xianna, H.; Yanbin, Y.; Baokun, L.; Chengjian, X.; Qingling, W. Proteolytic effect of starter culture during ripening of smoked horse sausage. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulou, D.A.; De Maere, H.; Berardo, A.; Janssens, B.; Filippou, P.; De Vuyst, L.; De Smet, S.; Leroy, F. Species Pervasiveness within the Group of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Associated with Meat Fermentation Is Modulated by pH. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moradi, M.; Mardani, K.; Tajik, H. Characterization and application of postbiotics of Lactobacillus spp. on Listeria monocytogenes in vitro and in food models. Lebenson. Wiss. Technol. 2019, 111, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, H.A.; Wilke, T.; Erdmann, R. Efficacy of bacteriocin-containing cell-free culture supernatants from lactic acid bacteria to control Listeria monocytogenes in food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 146, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prudêncio, C.V.; dos Santos, M.T.; Vanetti, M.C.D. Strategies for the use of bacteriocins in Gram-negative bacteria: Relevance in food microbiology. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 5408–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Landete, J.M. A review of food-grade vectors in lactic acid bacteria: From the laboratory to their application. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017, 37, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Granados, M.J.; Franco-Robles, E. Postbiotics in human health: Possible new functional ingredients? Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Kousheh, S.A.; Almasi, H.; Alizadeh, A.; Guimarães, J.T.; Yılmaz, N.; Lotfi, A. Postbiotics produced by lactic acid bacteria: The next frontier in food safety. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 3390–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, P.D.; Ross, R.; Hill, C. Bacteriocins—A viable alternative to antibiotics? Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013, 11, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Fan, L.; Jiang, Y.; Doucette, C.; Fillmore, S. Antimicrobial activity of bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria isolated from cheeses and yogurts. AMB Express 2012, 2, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dicks, L.M.T.; Dreyer, L.; Smith, C.; Van Staden, A.D. A Review: The Fate of Bacteriocins in the Human Gastro-Intestinal Tract: Do They Cross the Gut–Blood Barrier? Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Connor, P.M.; Kuniyoshi, T.M.; Oliveira, R.P.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P.; Cotter, P.D. Antimicrobials for food and feed; a bacteriocin perspective. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, C.R.; Coburn, P.S.; Gilmore, M.S. Enterococcal Cytolysin: A Novel Two Component Peptide System that Serves as a Bacterial Defense against Eukaryotic and Prokaryotic Cells. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2005, 6, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gálvez, A.; Abriouel, H.; López, R.L.; Ben Omar, N. Bacteriocin-based strategies for food biopreservation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 120, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holley, R.; Cordeiro, R. Microbiological Safety of Meat|Listeria monocytogenes. In Encyclopedia of Meat Sciences; Elsevier: London, UK, 2014; pp. 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.A.; Tulini, F.L.; dos Reis-Teixeira, F.B.; Rabinovitch, L.; Chaves, J.Q.; Rosa, N.G.; Cabral, H.; De Martinis, E.C.P. Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances (BLIS) produced by Bacillus cereus: Preliminary characterization and application of partially purified extract containing BLIS for inhibiting Listeria monocytogenes in pineapple pulp. Lebenson. Wiss. Technol. 2016, 72, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizani, D.; Morrissy, J.A.; Dominguez, A.P.; Brandelli, A. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes in dairy products using the bacteriocin-like peptide cerein 8A. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 121, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ramos, A.; Madi-Moussa, D.; Coucheney, F.; Drider, D. Current Knowledge of the Mode of Action and Immunity Mechanisms of LAB-Bacteriocins. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, A.C.L.; Almeida, R.C. Antibacterial efficacy of nisin, bacteriophage P100 and sodium lactate against Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat sliced pork ham. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2017, 48, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Singh, T.P.; Malik, R.K.; Bhardwaj, A.; De, S. Antibacterial efficacy of nisin, pediocin 34 and enterocin FH99 against L. monocytogenes, E. faecium and E. faecalis and bacteriocin cross resistance and antibiotic susceptibility of their bacteriocin resistant variants. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asare, P.T.; Zurfluh, K.; Greppi, A.; Lynch, D.; Schwab, C.; Stephan, R.; Lacroix, C. Reuterin Demonstrates Potent Antimicrobial Activity against a Broad Panel of Human and Poultry Meat Campylobacter spp. Isolates. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaefer, L.; Auchtung, T.; Hermans, K.E.; Whitehead, D.; Borhan, B.; Britton, R.A. The antimicrobial compound reuterin (3-hydroxypropionaldehyde) induces oxidative stress via interaction with thiol groups. Microbiology 2010, 156, 1589–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pum, D.; Toca-Herrera, J.L.; Sleytr, U.B. S-Layer Protein Self-Assembly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 2484–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klotz, C.; Goh, Y.J.; O’Flaherty, S.; Barrangou, R. S-layer associated proteins contribute to the adhesive and immunomodulatory properties of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Gao, S.-M.; Zhang, Q.-X.; Lu, R.-R. Murein hydrolase activity of surface layer proteins from Lactobacillus acidophilus against Escherichia coli. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 79, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martín, A.; Acosta, R.; Liddell, S.; Núñez, F.; Benito, M.J.; Asensio, M.A. Characterization of the novel antifungal protein PgAFP and the encoding gene of Penicillium chrysogenum. Peptides 2010, 31, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.; Owens, R.A.; Doyle, S.; Núñez, F.; Asensio, M.A. Quantitative proteomics reveals new insights into calcium-mediated resistance mechanisms in Aspergillus flavus against the antifungal protein PgAFP in cheese. Food Microbiol. 2017, 66, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Núñez, F.; Lara, M.S.; Peromingo, B.; Delgado, J.; Sánchez-Montero, L.; Andrade, M.J. Selection and evaluation of Debaryomyces hansenii isolates as potential bioprotective agents against toxigenic penicillia in dry-fermented sausages. Food Microbiol. 2015, 46, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalska-Krochmal, B.; Dudek-Wicher, R. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance. Pathogens 2021, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, G.; Bayram, A.; Zer, Y.; Balci, I. Synergy Tests by E Test and Checkerboard Methods of Antimicrobial Combinations against Brucella melitensis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eagly, A.H.; Wood, W. Using Research Syntheses to Plan Future Research. In The Handbook of Research Synthesis; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, H.; Field, D.; Rea, M.C.; Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P. Bacteriocin-Antimicrobial Synergy: A Medical and Food Perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meletiadis, J.; Pournaras, S.; Roilides, E.; Walsh, T.J. Defining Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index Cutoffs for Additive Interactions Based on Self-Drug Additive Combinations, Monte Carlo Simulation Analysis, and In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation Data for Antifungal Drug Combinations against Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karbowiak, M.; Szymański, P.; Zielińska, D. Synergistic Effect of Combination of Various Microbial Hurdles in the Biopreservation of Meat and Meat Products—Systematic Review. Foods 2023, 12, 1430. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12071430

Karbowiak M, Szymański P, Zielińska D. Synergistic Effect of Combination of Various Microbial Hurdles in the Biopreservation of Meat and Meat Products—Systematic Review. Foods. 2023; 12(7):1430. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12071430

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarbowiak, Marcelina, Piotr Szymański, and Dorota Zielińska. 2023. "Synergistic Effect of Combination of Various Microbial Hurdles in the Biopreservation of Meat and Meat Products—Systematic Review" Foods 12, no. 7: 1430. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12071430

APA StyleKarbowiak, M., Szymański, P., & Zielińska, D. (2023). Synergistic Effect of Combination of Various Microbial Hurdles in the Biopreservation of Meat and Meat Products—Systematic Review. Foods, 12(7), 1430. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12071430