Gastronomic Curiosity and Consumer Behavior: The Impact of Television Culinary Programs on Choices of Food Services

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Research Model

2.1. Key Concepts

| Source | The Aim of the Study | Research Sample | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dixon et al., 2007 [39] | The effects of television advertisements for junk food on children’s food attitudes and preferences | 19 grade 5 and 6 students from schools in Melbourne, Australia | Positive if we advertise nutrition food |

| Ejsymont et al., 2010 [40] | Assessment of the impact of television culinary programs on shaping the nutritional behavior of viewers | 134 Internet users | Positive |

| Boulos et al., 2012 [41] | How television is influencing the obesity epidemic | Obese children in the USA | Negative |

| Lane and Fisher, 2015 [1] | To investigate the exposure of a student population to celebrity chef television programs and to assess the influence these figures have and how they are perceived | A survey through an online questionnaire distributed at Bath Spa University—238 persons | Positive |

| Villani et al., 2015 [2] | To investigate people’s attitudes and beliefs about popular television cooking programs and celebrity chefs | 207 participants undertook the questionnaire | Neutral |

| Temeloğlu and Taşpınar, 2018 [6] | To determine the relationship between the cooking shows on TV and the people’s intention of participating in gastronomic tourism | 391 tourists that participated in gastronomic tourism | Positive |

| Ngqangashe et al., 2018 [42] | The effect of TV cooking show consumption on children’s food choice behavior | A sample of 85 children (32 girls and 48 boys) from two schools with comparable student profiles in terms of sociodemographic characteristics | Positive |

| Kizileli et al., 2019 [33] | To examine how celebrity chefs influenced the nutrition planning of their viewers | The study population was adult television viewers (≥18 years of age)—244 female and 144 male | Neutral |

| Folkvord et al., 2020 [43] | To test the effects of a cooking program on healthy food decisions | Class settings in 5 different schools | Positive if we advertise nutrition food |

| Fraga et al., 2020 [44] | To verify the effects of buying television-advertised food on schoolchildren eating behavior | 797 children were evaluated, the mean age was 9.81 (0.59) years, 50.7% were female, and 32.4% were overweight | Neutral |

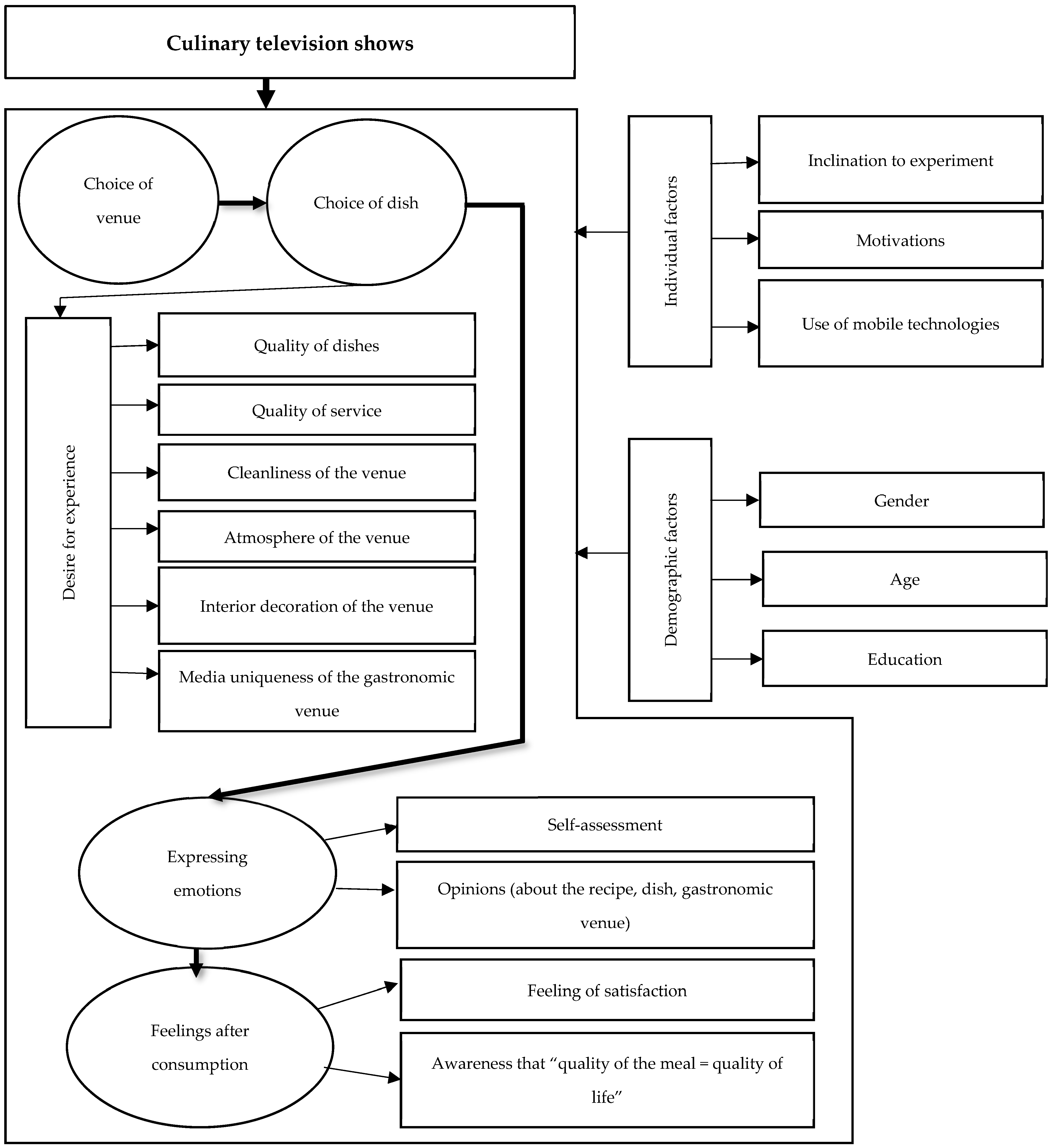

2.2. Conceptual Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Methodology

3.2. Objective of the Research and Hypotheses

- H1: Culinary television programs determine consumer behaviors by influencing a higher frequency of using gastronomic services.

- H2: Consuming meals at restaurants recommended in culinary television programs affects consumers’ perception of their quality of life.

- H3: The impact of culinary television programs on the frequency of using gastronomic services is greater the higher are the consumers’ propensity for experimentation, motivations, curiosity about the world, and use of new technologies.

3.3. Operationalization of the Conceptual Research Model

3.4. Questionnaire Development

3.5. Data Collections

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lane, S.R.; Fisher, S.M. The influence of celebrity chefs on a student population. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.M.; Egan, T.; Keogh, J.B.; Clifton, P.M. Attitudes and beliefs of Australian adults on reality television cooking programmes and celebrity chefs. Is there cause for concern? Descriptive analysis presented from a consumer survey. Appetite 2015, 91, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraher, M.; Lange, T.; Dixon, P. The influence of TV and celebrity chefs on public attitudes and behavior among the English public. J. Study Food Soc. 2000, 4, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisbord, S. McTV: Understanding the Global Popularity of Television Formats. Telev. New Med. 2004, 5, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, G. The Mass Production of Celebrity. Celetoids, Reality TV and the Demotic Turn. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2006, 2, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temeloğlu, O.; Taşpınar, E. Influence of Tv Cooking Shows on the Behavioral Intention of Participating in Gastronomic Tourism. J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 2018, 6, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J.; Crotts, J.C. Tourism and Gastronomy: Gastronomy’s Influence on How Tourists Experience a Destination. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, T. On the Line: Format, Cooking and Competition as Television Values. Crit. Stud. Telev. 2013, 8, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matwick, K.; Matwick, K. Storytelling on Cooking Shows. In Food Discourse of Celebrity Chefs of Food Network; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, T.; Gendron, D. Cooking up the “gastro-citizen” through school meal programs in France and Japan. Food Cult. Soc. 2019, 22, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roura, E.; Pareja, S.L.; Milà, R.; Cinca, N. Cooking and active leisure TAS Program, Spain: A Program Impact Pathways (PIP) analysis. Food Nutr. Bull. 2014, 35, S145–S153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angela, E. International Food Television Show Formats in the Digital Era. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 2018. Available online: https://theses.gla.ac.uk/30925/1/2018espositophd.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Almeida, S.S.; Nascimento, P.C.B.D.; Quaioti, T.C.B. Amount and quality of food advertisement on Brazilian television. Rev Saúde Pública 2002, 36, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinburn, B.; Shelly, A. Effects of TV time and other sedentary pursuits. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, S132–S136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifelli, B.; Kurp, J.; Clarke, T.B.; Clarke, I. A comparative exploration of celebrity chef influence on millennials. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2020, 23, 442–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giousmpasoglou, C.; Brown, L.; Cooper, J. The role of the celebrity chef. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkol, S.; Cifci, I. Delving into the role of celebrity chefs and gourmets in culinary destination marketing. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 26, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopiatis, A.; Melanthiou, Y. The celebrity chef phenomenon: A (reflective) commentary. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 538–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balwant, P.T. Is There a Bright Side to Destructive Leadership? How Gordon Ramsay Leads Change in Nightmare Kitchens. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2021, 14, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soneji, D.; Riedel, A.; Martin, B. How Gordon Ramsay appeals to consumers: Effects of self-concept clarity and celebrity meaning on celebrity endorsements. J. Strateg. Mark. 2015, 23, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, V. Konsumverhalten; Verlag, W. Kohlhammer GmbH: Stuttgart, Germany; Berlin, Germany; Köln, Germany, 1993; p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. Understanding Human Value; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Wiswede, G. Konsumsoziologie. In Konsum: Soziologische Ökonomische und Psychologische, Perspektiven, ed.; Rosenkranz, D., Schneider, N.F., Eds.; Leske + Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tanrikulu, C. Theory of consumption values in consumer behaviour research: A review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1176–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, J. Konsumpcja. Warunki, Zróżnicowania, Strategie; IFiS PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 1998; p. 406. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Languages. Available online: https://languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/ (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Konsum Virtueller Güter: Grundlagen, Motive und Kaufprozesse. Eine Explorative Studie. Europauniversität Flensburg. Dissertation zur Erlangung des Akademischen Grades Eines Doktor Rerum Politicarum (Dr. rer. pol.). Gutahter: Prof. Dr. Berthold, H. Hass, Europauniversität Flensburg; Prof. Dr. Jens Junge, Design Akademie Berlin, Vorgelegt von: Jens Frieling 28.04.2016. Available online: https://www.zhb-flensburg.de/fileadmin/content/spezial-einrichtungen/zhb/dokumente/dissertationen/frieling/konsum-virtueller-gueter-dissertation-jens-frieling.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Fong, Y. Impact of Television Cooking Shows on Food Preferences. 2015. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/6bce155970bb0c70884e60cdcf6c0496/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; López-Guzmán, T. Protection of culinary knowledge generation in Michelin-Starred Restaurants. The Spanish case. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2018, 14, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Solier, I. TV Dinners: Culinary television, education and distinction. Contin. J. Media Cult. Stud. 2005, 19, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizileli, M.; Çetin, K.; Akar Sahingoz, S. The effect of television shows on daily nutrition planning. Int. J. Contemp. Appl. Res. 2019, 6, 149–158. Available online: http://ijcar.net/assets/pdf/Vol6-No5-May2019/12.-THE-EFFECT-OF-TELEVISION-SHOWS-ON-DAILY-NUTRITION-PLANNING.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- The Harris Poll. Three in Ten Americans Love to Cook, While One in Five Do Not Enjoy It or Don’t Cook. 27 July 2010. Available online: http://www.harrisinteractive.com/NewsRoom/HarrisPolls/tabid/447/mid/1508/articleId/444/ctl/ReadCustom%20Default/Default.aspx (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- The Harris Poll. EVOO and Yummo! 30 Minute Meals Is America’s Favorite Cooking Show. 29 July 2010. Available online: http://www.harrisinteractive.com/NewsRoom/HarrisPolls/tabid/447/mid/1508/articleId/446/ctl/ReadCustom%20Default/Default.aspx (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Clifford, D.; Anderson, J.; Auld, G.; Champ, J. Good grubbing’: Impact of a TV cooking show for college students living off campus. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2009, 41, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.; Bargh, J.; Brownell, K. Priming effects of television food advertising on eating behavior. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, S.; Adams, J.; White, M. Nutritional content of supermarket ready meals and recipes by television chefs in the United Kingdom: Cross sectional study. BMJ 2012, 345, e7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, H.; Scully, M.; Wakefield, M.; White, V.; Crawford, D. The effects of television advertisements for junk food versus nutrition food on children’s food attitudes and preferences. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejsymont, J.; Zegan, M.; Kucharska, A.; Michota-Katulska, E. Wpływ telewizyjnych programów kulinarnych na zachowania żywieniowe. Zyw. Człowieka Metab. 2010, 37, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Boulos, R.; Vikre, E.; Oppenheimer, S.; Chang, H.; Kanerek, R.B. ObesiTV: How television is influencing the obesity epidemic. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 107, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngqangashe, Y.; De Backer, C.; Hudders, L.; Hermans, N. TV consumption as health catalyst? An experimental investigation of the effect of TV cooking show consumption on children’s food choice behavior. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkvord, F.; Anschütz, D.; Geurts, M. Watching TV Cooking Programs: Effects on Actual Food Intake Among Children. J. Nutr. Behav. 2020, 52, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, R.S.; Silva, S.L.R.; Santos, L.C.D.; Titonele, L.R.D.O.; Carmo, A.D.S. The habit of buying foods announced on television increases ultra-processed products intake among schoolchildren 2020. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00091419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogunia-Borowska, M. Fenomen Telewizji; Uniwersytet Jagieloński: Kraków, Poland, 2012; Available online: https://ruj.uj.edu.pl/xmlui/bitstream/handle/item/19857/bogunia-borowska_fenomen_telewizji_2012.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Kowalski, M. Obraz telewizyjny jako przestrzeń kultury zdrowia. In Przemoc i Zdrowie w Obrazach Telewizyjnych; Kowalski, M., Drożdż, M., Eds.; Oficyna Wydawnicza Impuls: Cracow, Poland, 2008; pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Aksaçlıoğlu, A.G.; Yılmaz, B. Öğrencilerin Televizyon İzlemeleri ve Bilgisayar Kullanmalarının Okuma Alışkanlıkları Üzerine Etkisi. Türk Kütüphaneciliği 2007, 21, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenlos, J.; Wormuth, B. Watching a food-related television show and caloric intake: A laboratory study. Appetite 2013, 61, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketchum, C. The essence of cooking shows. How the food network constructs consumer fantasies. J. Commun. Inq. 2005, 29, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, A.; Dias, Á.; Pereira, L.; Simões, A. Gastronomic Experience and Consumer Behavior: Analyzing the Influence on Destination Image. Foods 2023, 12, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.M. Culinary Tourism. J. Am. Folk. 2008, 121, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, S.S. Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. Culinary-gastronomic tourism—A search for local food experiences. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 44, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaciow, M.; Wolny, R. TV Cooking Programmes and Consumer Behaviour in the Market for Catering—A Conceptual Model. Handel Wewnętrzny 2018, 1, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Iwashita, C. Cooking identity and food tourism: The case of Japanese udon noodles. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2016, 41, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Power in Tourism Communities. In Tourism in Destination Communities; Informatics Publishing: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Child, J. The French Chef Cookbook; Random House USA Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Badania Odbioru Programów Radiowych i Telewizyjnych. Raporty Rządowe. Available online: https://www.krrit.gov.pl/dla-nadawcow-i-operatorow/kontrola-nadawcow/badania-odbioruprogramow-radiowych-i-telewizyjnych/rynek-telewizyjny/raporty-roczne/ (accessed on 30 April 2017).

- Halford, J.; Boyland, E.; Hughes, G.; Stacey, L.; McKean, S.; Dovey, T. Beyond-brand effect of television food advertisements on food choice in children: The effects of weight status. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, S.; Tarabashkina, L.; Roberts, M.; Quester, P.; Chapman, K.; Miller, C. The effects of television and internet food advertising on parents and children. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 2205–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, A.; Suhrcke, M. The effect of TV viewing on children’s obesity risk and mental well-being: Evidence from the UK digital switchover. J. Health Econ. 2021, 80, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.M.; Richards, G. (Eds.) Tourism and Gastronomy; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Berbel-Pineda, J.M.; Palacios-Florencio, B.; Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M.; Santos-Roldán, L. Gastronomic experience as a factor of motivation in the tourist movements. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2019, 18, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyland, E.; Halford, J. Television advertising and branding: Effects on eating behavior and food preferences in children. Appetite 2013, 62, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Brochado, A.; Sousa, A.; Borges, A.P.; Barbosa, I. What’s on the menu?: How celebrity chef brands create happiness. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 2413–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, D.; Lin, M.S.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, L. Entertainer celebrity vs. celebrity chefs: The joint effect of celebrity endorsement and power distance belief on restaurant consumers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 106, 103291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipov, M.; Gale, F. Celebrity chefs, consumption politics and food labelling: Exploring the contradictions. J. Consum. Cult. 2020, 20, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matwick, K.; Matwick, K. Food Discourse of Celebrity Chefs of Food Network; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Raab, C.; Chen, C.-C. The Influence of Celebrity Chefs on Restaurant Customers’ Behavior. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen Revolution. Available online: https://kuchennerewolucje.tvn.pl (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Gustafsson, I.B.; Öström, Å.; Johansson, J.; Mossberg, L. The Five Aspects Meal Model: A tool for developing meal services in restaurants. J. Foodserv. 2006, 17, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Q.-L.; Ab Karim, S.; Awang, K.W.; Abu Bakar, A.Z. An integrated structural model of gastronomy tourists’ behaviour. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 11, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styś, A. Rynek Usług w Ujęciu Przestrzennym; Instytut Resortowo-Uczelniany Handlu i Usług Akademii Ekonomicznej, Instytut Handlu Wewnętrznego: Wrocław-Warszawa, Poland, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Scarso, S.G.; Squadrilli, L. Marketing Smaku; Edra Urban & Partner: Wrocław, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Styś, A.; Olearnik, J. Ekonomika i Organizacja Usług; PWE: Warsaw, Poland, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczuk, I. Zachowania Konsumentów na Rynku Usług Gastronomicznych–Aspekt Marketingowy; SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stolarska, A. Gospodarstwa domowe na rynku usług gastronomicznych w Polsce–tendencje i prognozy. Mark. Rynek 2015, 8, 699–709. [Google Scholar]

- Bilska, B.; Grzesińska, W.; Tomaszewska, M.; Przybylski, W. Ocena wpływu wybranych czynników na wybór lokali gastronomicznych. Rocz. Nauk. Stowarzyszenia Ekon. Rol. Agrobiznesu 2014, 16, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gajewska, P.; Szewczyk, I. Zarządzanie na rynku doznań w branży gastronomicznej. Zesz. Nauk. Wyższej Szkoły Humanit. Zarządzanie 2012, 2, 114–133. [Google Scholar]

- Grębowiec, M. Czynniki warunkujące jakość oraz ich wpływ na podejmowanie decyzji nabywczych na rynku gastronomicznym. Zesz. Nauk. Szkoły Głównej Gospod. Wiej. Warszawie Ekon. Organ. Gospod. Żywnościowej 2010, 80, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.; Trziszka, T.; Otto, J. Pozycja jakości posiłków wśród czynników kształtujących preferencje nabywców usług gastronomicznych. Żywność. Nauka. Technologia. Jakość 2008, 3, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, W.B. Zarządzanie Jakością Obsługi w Restauracjach i Hotelach; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Kraków, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Emre Cetin, K.B. Islamic lifestyle and Emine Beder's TV cookery show Kitchen Love. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2017, 20, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolny, R. Zachowania młodych konsumentów na rynku usług gastronomicznych. Handel Wewnętrzny 2006, 6, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, J. Marketing w Gastronomii; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Węziak-Białowolska, D. Operacjonalizacja i skalowanie w ilościowych badaniach społecznych. Zesz. Nauk. Inst. Stat. Demogr. SGH 2011, 16, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Brzeziński, J. Metodologia Badań Psychologicznych; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2004; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E. Badania Społeczne w Praktyce; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2004; p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- Zakrzewska-Bielawska, A. Modele badawcze w naukach o zarządzaniu. Organ. Kier. 2018, 2, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jaciow, M. Ekwiwalencja w Międzynarodowych Badaniach Rynku; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2018; pp. 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kopyciński, P.; Mamica, Ł. Operacjonalizacja Metodologii Badań Foresight; Małopolska Szkoła Administracji Publicznej Akademii Ekonomicznej w Krakowie: Cracow, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sagan, A. Zmienne Ukryte w Badaniach Marketingowych; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Krakowie: Cracow, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Portal “Wirtualnemedia”. Available online: https://www.wirtualnemedia.pl/artykul/kuchenne-rewolucje-tvn-koniec-2023-rok (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Portal “Wirtualnemedia”. Available online: https://www.wirtualnemedia.pl/artykul/gdzie-ogladac-kuchenne-rewolucje-jesien-2022-wyniki-ogladalnosci (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Clark, M.A.; Wood, R.C. Consumer loyalty in the restaurant industry—A preliminary exploration of the issues. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1998, 10, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; O'Neill, M.; Liu, Y.; O'Shea, M. Factors Driving Consumer Restaurant Choice: An Exploratory Study From the Southeastern United States. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, S.; Joohyang, K. Restaurant Choice. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2004, 7, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, K.; Jones, S.; Benefield, M.; Walton, J. Building consumer relationships in the quick service restaurant industry. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auty, S. Consumer Choice and Segmentation in the Restaurant Industry. Serv. Ind. J. 1992, 12, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibril, A.B.; Adzovie, D.E. Understanding the moderating role of E-WoM and traditional media advertisement toward fast-food joint selection: A uses and gratifications theory. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2022, 27, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Dhir, A.; Bala, P.K.; Kaur, P. Why do people use food delivery apps (FDA)? A uses and gratification theory perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngqangashe, Y.; Maldoy, K.; De Backer, C.J.S.; Vandebosch, H. Exploring adolescents’ motives for food media consumption using the theory of uses and gratifications. Communications 2022, 47, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.C.; Meyer, T.; Kinard, B. Implementing a Delight Strategy in a Restaurant Setting: The Power of Unsolicited Recommendations. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 57, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, E.; Xu, M. Beyond the authentic taste: The tourist experience at a food museum restaurant. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamatha, M.; Shivakumar, S.; Thriveni, J.; Venogopal, K.R. Restaurant Based Emotion Detection Of Images From Social Media Sites Using Deep Learning Model. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 2023, 11, 267–276. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.S.; Azizzadeh, F.; Zupok, S.; Hosseini, A.; Jones-Esan, L. Service Employees’ Expressions of Emotions in Restaurants: A Transcendental Phenomenology Study. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2022, 13, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, M.; Kim, S. Role of Emotions in Fine Dining Restaurant Online Reviews: The Applications of Semantic Network Analysis and a Machine Learning Algorithm. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2022, 23, 875–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.-H.; Goh, Y.-N.; Lim, C.-N. Linking customer positive emotions and revisit intention in the ethnic restaurant: A Stimulus Integrative Model. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, M.S.; Niu, X.; Hossain, M.S. How dissimilarity attributes at restaurants trigger negative emotions and associated behavioral intentions: The role of attribute performance. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022, 6, 2199–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curnutt, H. Cooking on Reality TV: Chef-Participants and Culinary Television, Food, Media and Contemporary Culture: The Edible Image; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollows, J.; Jones, S. Please don't try this at home: Heston Blumenthal, cookery TV and the culinary field. Food Cult. Soc. 2011, 3, 521–5370. [Google Scholar]

- Golestanbagh, N.; Miraghajani, M.; Amani, R.; Symonds, M.E.; Neamatpour, S.; Haghighizadeh, M.H. Association of Personality Traits with Dietary Habits and Food/Taste Preferences. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 12, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.G.; Strycker, L.A. Personality traits and eating habits: The assessment of food preferences in a large community sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2002, 32, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, C. Influence of livestreamers’ intimate self-disclosure on tourist responses: The lens of parasocial interaction theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 57, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarmino, A. Application of theory to literary tourism: A comparison of parasocial interaction theory and co-creation theory. J. Herit. Tour. 2023, 18, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, S.D. The role of the notion of communication in the psychological theory of activity. Vopr. Psikhologii 2015, 3, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Hou, J.; Jiang, B. The Impact of Communication Style Similarity on Customer’s Perception of Virtual Advisory Services: A Similarity Theory Perspective. In Proceedings of the 12th Wuhan International Conference on E-Business, WHICEB 2013, Wuhan, China, 25–26 May 2013; pp. 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J. Understanding customer brand engagement in brand communities: An application of psychological ownership theory and congruity theory. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 969–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Seo, H.; Koo, H. Exploring the spatio-temporal clusters of closed restaurants after the COVID-19 outbreak in Seoul using relative risk surfaces. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdzik, B.; Jaciow, M.; Wolny, R. Types of E-Consumers and Their Implications for Sustainable Consumption—A Study of the Behavior of Polish E-Consumers in the Second Decade of the 21st Century. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Description |

|---|---|

| Celebrity chef endorsement | Viewers are often drawn to restaurants featured or endorsed by famous chefs seen on TV. |

| Food presentation on TV | Visually appealing dishes showcased on television can pique viewers’ interest in trying them in person. |

| Unique and exotic ingredients | TV programs often introduce novel or exotic ingredients, sparking curiosity among viewers to taste them. |

| Host recommendations | If the TV host recommends a specific restaurant or dish, viewers tend to trust their judgment and visit. |

| Location and ambiance | The location and ambiance portrayed on TV can attract viewers who seek a similar dining atmosphere. |

| Positive reviews and ratings | Favorable reviews and ratings mentioned on TV programs can influence people’s dining choices. |

| Cultural exploration | Culinary shows that explore diverse cuisines and cultures inspire viewers to try new food experiences. |

| Social media influence | Social media buzz and trends related to culinary TV programs can lead people to featured restaurants. |

| Dietary compatibility | Some viewers choose restaurants aligned with their dietary restrictions or preferences as seen on TV. |

| Emotional connection | TV programs that evoke emotions or nostalgia can motivate viewers to visit places associated with those feelings. |

| Accessibility and convenience | Proximity and ease of access to the featured restaurant play a role in the decision-making process. |

| Budget and affordability | The cost of dining at a featured restaurant may impact the choice, depending on one’s budget. |

| Word of mouth | Recommendations from friends and family who watched the same TV show can strongly influence choices. |

| Special offers and promotions | Discounts or promotions offered by restaurants featured on TV can attract viewers. |

| Specification | Element of the Operationalization Process |

|---|---|

| Dependent variables | 1. Variables for the G indicator: Did you visit the restaurant influenced by the “Kitchen Revolutions” program? (response: yes/no) 2. Variables for the DE indicator: (Z1) How do you rate the quality of the dish ordered (from Magda Gessler’s menu)? (response on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is very low, 5 is very high) (Z2) How do you rate the quality of service? (response on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is very low, 5 is very high) (Z3) How do you rate the cleanliness of the establishment? (response on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is very dirty, 5 is very clean) (Z4) How do you rate the atmosphere of the establishment? (response on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is very unpleasant, 5 is very pleasant) (Z5) How do you rate the decor of the establishment? (response on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is very ugly, 5 is very nice) (Z6) How do you rate the media uniqueness of the establishment? (response on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is very low, 5 is very high) 3. Variables for the EM index: (V1) What emotions did you feel after leaving the restaurant? (answers on a scale of 1 to 5) (V1.1) Negative surprise—Positive surprise; (V1.2) Disappointment—Satisfaction; (V1.3) Sadness—Joy; (V1.4) Regret spending money—Visit worth its price; (V1.5) Visit was a waste of time—Time well spent; (V1.6) Felt underfed—Felt very full; (V1.7) Disappointed by the taste of ordered dishes—Delighted by the taste of ordered dishes (V2) Whom did you tell about your emotions related to the restaurant visit? (answer: family, friends, work colleagues, wrote a review on social media, wrote a review on an Internet forum, wrote a review on the restaurant’s website, other ways, which?) (V3) How many people did you tell about your emotions related to the restaurant visit? 4. Variables for the SC index: (Y1) How do you rate the taste of the ordered dishes? (Y1.1) Disappointed by the taste of the ordered starter—Delighted by the taste of the ordered starter; (Y1.2) Disappointed by the taste of the ordered soup—Delighted by the taste of the ordered soup; (Y1.3) Disappointed by the taste of the ordered main dish—Delighted by the taste of the ordered main dish; (Y1.4) Disappointed by the taste of the ordered dessert—Delighted by the taste of the ordered dessert (Y2) How do you rate the appearance of the ordered dishes? (Y2.1) Disappointed by the appearance of the ordered starter—Delighted by the appearance of the ordered starter; (Y2.2) Disappointed by the appearance of the ordered soup—Delighted by the appearance of the ordered soup; (Y2.3) Disappointed by the appearance of the ordered main dish—Delighted by the appearance of the ordered main dish; (Y2.4) Disappointed by the appearance of the ordered dessert—Delighted by the appearance of the ordered dessert (Y3) Do you agree with the following statement (on a scale of Strongly disagree to Strongly agree): Eating meals at restaurants recommended by Magda Gessler affects the quality of my life. |

| Independent variables | 1. Personality profile Please rate on a scale of 1 to 5 your approach to life: I like to experiment, I am a fan of technology, I like to engage, I set goals for myself and achieve them, I am curious about the world. 2. Demographic profile Gender (female, male), Age, Education (primary, vocational, secondary, higher) |

| Indicators | Season 25 (from September 2022 to December 2022) | Season 27 (from September 2023 to October 2023) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viewers aged 4+ | AMR * | 1,304,732 | 1,082,940 |

| SHR % ** | 12.01% | 10.09% | |

| RCH (1 min) *** | 2,459,282 | 2,010,720 | |

| Viewers aged 16–49 | AMR | 620,573 | 496,222 |

| SHR % | 15.89% | 13.11% | |

| RCH (1 min) | 1,119,977 | 869,494 | |

| Viewers aged 20–54 | AMR | 243,017 | 574,130 |

| SHR % | 17.88% | 12.53% | |

| RCH (1 min) | 405,484 | 1,027,244 | |

| Characteristics | Item | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 61.6 |

| Male | 38.4 | |

| Age (years) | 18–24 | 29.0 |

| 25–29 | 28.6 | |

| 30–39 | 19,4 | |

| 40 and more | 23.0 | |

| Education | Primary | 1.4 |

| Vocational | 7.5 | |

| Secondary | 35.6 | |

| Higher | 55.5 |

| Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of the food | 1.4 | 5.2 | 24.0 | 51.0 | 18.4 |

| Quality of the service | 1.9 | 6.5 | 22.7 | 51.2 | 17.7 |

| Cleanliness | 1.0 | 1.6 | 10.4 | 62.8 | 24.3 |

| Ambience | 0.3 | 3.3 | 12.1 | 60.2 | 24.2 |

| Design | 0.7 | 5.4 | 17.4 | 57.3 | 19.3 |

| Uniqueness | 3.0 | 11.8 | 46.1 | 29.2 | 9.9 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative surprise | 2.8 | 6.5 | 23.6 | 40.6 | 26.5 | Positive surprise |

| Disappointment | 4.7 | 6.9 | 13.6 | 39.1 | 35.7 | Satisfaction |

| Sadness | 3.4 | 3.0 | 19.0 | 41.4 | 33.2 | Joy |

| Regret for money spent | 6.4 | 6.6 | 20.1 | 34.2 | 32.7 | A visit worthwhile |

| The visit was a waste of time | 4.9 | 3.7 | 14.7 | 33.9 | 42.8 | Time very well spent |

| Feeling unfulfilled | 3.0 | 4.5 | 14.7 | 34.0 | 43.8 | Feeling very full |

| Disappointed with the taste of the food | 5.4 | 5.3 | 15.3 | 47.8 | 26.2 | Delightful taste of the food |

| Items | % |

|---|---|

| Friends | 69.9 |

| Family | 62.9 |

| Colleagues at work | 38.3 |

| Social media opinion | 7.1 |

| Internet forum | 4.0 |

| Restaurant website review | 3.4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The appetizer’s taste disappointed me | 4.5 | 5.9 | 20.6 | 43.9 | 25.1 | The appetizer’s taste was delightful |

| The soup’s taste disappointed me | 3.7 | 6.0 | 18.8 | 43.5 | 28.0 | The soup’s taste was delightful |

| The main course’s taste disappointed me | 4.0 | 4.7 | 14.9 | 44.0 | 32.3 | The main course’s taste was delightful |

| The dessert’s taste disappointed me | 2.7 | 4.5 | 17.6 | 41.8 | 33.4 | The dessert’s taste was delightful |

| The appetizer’s look disappointed me | 2.3 | 4.9 | 17.6 | 48.3 | 26.8 | The appetizer’s look was delightful |

| The soup’s look disappointed me | 2.8 | 5.1 | 21.2 | 45.6 | 25.3 | The soup’s look was delightful |

| The main course’s look disappointed me | 2.8 | 2.9 | 16.1 | 48.0 | 30.2 | The main course’s look was delightful |

| The dessert’s look disappointed me | 2.5 | 3.1 | 18.3 | 41.9 | 34.1 | The dessert’s look was delightful |

| Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Mean | Median | Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I do not like to experiment | 2.8 | 4.3 | 19.3 | 31.7 | 41.9 | 4.05 | 4.0 | I like to experiment |

| I am not a fan of technology | 4.3 | 6.2 | 23.5 | 35.2 | 30.7 | 3.81 | 4.0 | I am a fan of technology |

| I do not like to engage | 4.2 | 6.5 | 21.0 | 33.3 | 35.0 | 3.88 | 4.0 | I like to engage |

| I do not set goals for myself | 2.6 | 3.7 | 18.4 | 36.2 | 39.2 | 4.06 | 4.0 | I set goals for myself and achieve them |

| I am not curious about the world | 2.0 | 1.4 | 9.1 | 25.6 | 61.9 | 4.44 | 5.0 | I am curious about the world |

| Traits | Pearson’s Chi-Squared Test | df | Asymptotic Significance (Two-Sided) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propensity for experimentation | 19.625 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Interest in technology | 13.161 | 4 | 0.011 |

| Engagement | 5.534 | 4 | 0.237 |

| Achieving goals | 9.749 | 4 | 0.045 |

| Curiosity about the world | 8.410 | 4 | 0.078 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gajdzik, B.; Jaciow, M.; Wolniak, R.; Wolny, R. Gastronomic Curiosity and Consumer Behavior: The Impact of Television Culinary Programs on Choices of Food Services. Foods 2024, 13, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13010115

Gajdzik B, Jaciow M, Wolniak R, Wolny R. Gastronomic Curiosity and Consumer Behavior: The Impact of Television Culinary Programs on Choices of Food Services. Foods. 2024; 13(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleGajdzik, Bożena, Magdalena Jaciow, Radosław Wolniak, and Robert Wolny. 2024. "Gastronomic Curiosity and Consumer Behavior: The Impact of Television Culinary Programs on Choices of Food Services" Foods 13, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13010115

APA StyleGajdzik, B., Jaciow, M., Wolniak, R., & Wolny, R. (2024). Gastronomic Curiosity and Consumer Behavior: The Impact of Television Culinary Programs on Choices of Food Services. Foods, 13(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13010115