Green Purchase Behaviour Gap: The Effect of Past Behaviour on Green Food Product Purchase Intentions among Individual Consumers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

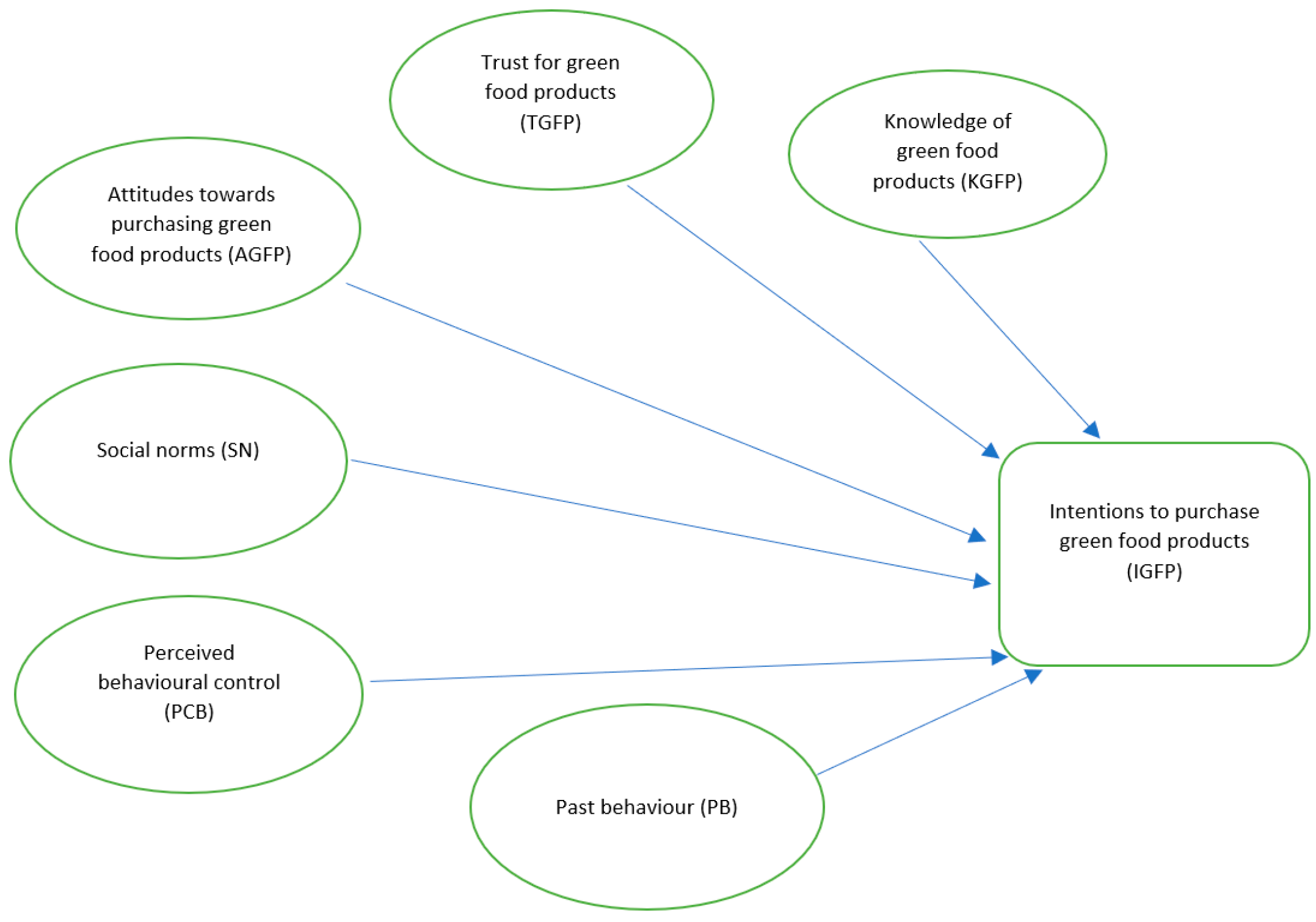

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

3. Research Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Past Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, S.N.B.B. Organic food: A study on demographic characteristics and factors influencing purchase intentions among consumers in klang valley, malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Yu, D.; Zubair, M.; Rasheed, M.I.; Khizar, H.M.U.; Imran, M. Health Consciousness, Food Safety Concern, and Consumer Purchase Intentions Toward Organic Food: The Role of Consumer Involvement and Ecological Motives. SAGE Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbiński, B.; Surmacz, T.; Kuźniar, W.; Witek, L. The role of the ecological awareness and the influence on food preferences in shaping pro-ecological behavior of young consumers. Agriculture 2021, 11, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, L.; Kuźniar, W. Green purchase behavior: The effectiveness of sociodemographic variables for explaining green purchases in emerging market. Sustainability 2020, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Rahman, M.K.; Rana, M.S.; Gazi, M.A.I.; Rahaman, M.A.; Nawi, N.C. Predicting Consumer Green Product Purchase Attitudes and Behavioral Intention during COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 760051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, L.; Li, J. Unearthing the effects of personality traits on consumer’s attitude and intention to buy green products. Nat. Hazards 2018, 93, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, S.B.; Kumar, H.; Negi, N. Consumers’ attitude and purchase intention towards ‘green’ products: A study of selected FMCGs. Int. J. Green Econ. 2019, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión Bósquez, N.G.; Arias-Bolzmann, L.G. Factors influencing green purchasing inconsistency of Ecuadorian millennials. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2461–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. Int. Strategy Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrita, U.W.; Mohiuddin, M.F. Impact of opportunity and ability to translate environmental attitude into ecologically conscious consumer behavior. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2020, 28, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, L. Attitude-Behaviour Gap Among Polish Consumers Regarding Green Purchases. Visegr. J. Bioecon. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S. Extending the theory of planned behavior to explain the effects of cognitive factors across different kinds of green products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Leng, K.; Xiong, H. Research on the influencing factors of consumers’ green purchase behavior in the post-pandemic era. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 69, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalanon, P.; Chen, J.-S.; Le, T.T.Y. “Why Do We Buy Green Products?” An Extended Theory of the Planned Behavior Model for Green Product Purchase Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Ploeger, A. Explaining consumers’ intentions towards purchasing green food in Qingdao, China: The amendment and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2019, 133, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.P. Consumers’ purchase behaviour and green marketing: A synthesis, review and agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, P.K.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.S.R.; da Costa, M.F.; Maciel, R.G.; Aguiar, E.C.; Wanderley, L.O. Consumer antecedents towards green product purchase intentions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers: Evidences from a developing nation. Appetite 2016, 96, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Why not green marketing? Determinates of consumers’ intention to green purchase decision in a new developing nation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Huque, S.M.R.; Hafeez, M.H.; Shariff, M.N.M. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalco, A.; Noventa, S.; Sartori, R.; Ceschi, A. Predicting organic food consumption: A meta-analytic structural equation model based on the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2017, 112, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, P.; Tarafder, T.; Pearson, D.; Henryks, J. Intention-behaviour gap and perceived behavioural control-behaviour gap in theory of planned behaviour: Moderating roles of communication, satisfaction and trust in organic food consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 81, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawan, A.; Noermijati, N.; Sunaryo, S.; Aisjah, S. Green product buying intentions among young consumers: Extending the application of theory of planned behavior. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2018, 16, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.-C. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior model to investigate purchase intention of green products among Thai consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, S.; Ahmed, M.J.; Ahmad, R.; Khan, B.S.; Xin, C. Factors influencing green purchase intention: Moderating role of green brand knowledge. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Luo, X.; Riaz, M.U. On the Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analysis Approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Chang, C.-Y.; Yansritakul, C. Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askadilla, W.L.; Krisjanti, M.N. Understanding indonesian green consumer behavior on cosmetic products: Theory of planned behavior model. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 15, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onel, N. Pro-environmental Purchasing Behavior of Consumers: The Role of Norms. Soc. Mark. Q. 2017, 23, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Bai, R. How Does Green Product Knowledge Effectively Promote Green Purchase Intention? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The Importance of Consumer Trust for the Emergence of a Market for Green Products: The Case of Organic Food. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Bernard, S.; Rahman, I. Greenwashing in hotels: A structural model of trust and behavioral intentions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Walker, T.; Barabanov, S. A psychological approach to regaining consumer trust after greenwashing: The case of Chinese green consumers. J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusyani, E.; Lavuri, R.; Gunardi, A. Purchasing eco-sustainable products: Interrelationship between environmental knowledge, environmental concern, green attitude, and perceived behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Suki, N. Green product purchase intention: Impact of green brands, attitude, and knowledge. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2893–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Direct Experience and the Strength of the Personal Norm-Behavior Relationship. Psychol. Mark. 2002, 19, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumudhini, N.; Kumaran, S.S. Factors Influencing on Purchase Intention towards Organic and Natural Cosmetics. SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Lin, C.-K.; Safdari, M.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chen, S.-H.; Hamilton, K. Using an integrated social cognition model to explain green purchasing behavior among adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khare, A. Green Apparel Buying: Role of Past Behavior, Knowledge and Peer Influence in the Assessment of Green Apparel Perceived Benefits. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2023, 35, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S. Exploring the interaction effects of norms and attitudes on green travel intention: An empirical study in eastern China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Bisai, S. Factors influencing green purchase behavior of millennials in India. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2018, 29, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.P.; Chakraborty, A.; Roy, M. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to explore circular economy readiness in manufacturing MSMEs, India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Deng, T. Research on the green purchase intentions from the perspective of Product knowledge. Sustainability 2016, 8, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, K.; Gillan, W.; Naquin, M. An Examination of College Students’ Knowledge, Perceptions, and Behaviors Regarding Organic Foods. Am. J. Health Educ. 2018, 49, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokan, K.V.; Lee, T.C.; Bhoyar, M.R. The intention of green products purchasing among Malaysian consumers: A case study of batu pahat, johor. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.J.; Hagger, M.S.; Morrissey, S.; Hamilton, K. Predicting fruit and vegetable consumption in long-haul heavy goods vehicle drivers: Application of a multi-theory, dual-phase model and the contribution of past behaviour. Appetite 2018, 121, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, E.W.L.; Chu, S.K.W. Students’ online collaborative intention for group projects: Evidence from an extended version of the theory of planned behaviour. Int. J. Psychol. 2016, 51, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, M.; Raats, M.M.; Shepherd, R. The Role of Self-Identity, Past Behavior, and Their Interaction in Predicting Intention to Purchase Fresh and Processed Organic Food. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 669–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Shahanjarini, A.; Makvandi, Z.; Faradmal, J.; Bashirian, S.; Hazavehei, M.M. An examination of the past behaviour-intention relationship in the case of brushing children’s teeth. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2016, 14, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeysekera, I.; Manalang, L.; David, R.; Grace Guiao, B. Accounting for Environmental Awareness on Green Purchase Intention and Behaviour: Evidence from the Philippines. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzyminska, M.; Jakubowska, D. The conceptualization of novel organic food products: A case study of Polish young consumers. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1884–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundala, R.R.; Nawaz, N.; Harindranath, R.M.; Boobalan, K.; Gajenderan, V.K. Does gender moderate the purchase intention of organic foods? Theory of reasoned action. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Braghieri, A.; Piasentier, E.; Favotto, S.; Naspetti, S.; Zanoli, R. Effect of information about organic production on beef liking and consumer willingness to pay. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetto, C.; Biondi, V.; Previti, A.; De Pascale, A.; Monti, S.; Alibrandi, A.; Zirilli, A.; Lanfranchi, M.; Pugliese, M.; Passantino, A. Willingness to Pay a Higher Price for Pork Obtained Using Animal-Friendly Raising Techniques: A Consumers’ Opinion Survey. Foods 2023, 12, 4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladwein, R.; Romero, A.M.S. The role of trust in the relationship between consumers, producers and retailers of organic food: A sector-based approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xiong, J.; Yan, J.; Wang, Y. Perceived quality of traceability information and its effect on purchase intention towards organic food. J. Mark. Manag. 2021, 37, 1267–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, K.; Lu, G.; Mahmoudi, M.; Lee, E.; Almenar, E. US Consumers’ Awareness, Purchase Intent, and Willingness to Pay for Packaging That Reduces Household Food Waste. Foods 2023, 12, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, L. Zachowania Nabywców Wobec Produktów Ekologicznych—Determinanty, Model i Implikacje dla Marketingu; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Rzeszowskiej: Rzeszów, Poland, 2019; pp. 232–234. [Google Scholar]

- St Quinton, T.; Morris, B.; Trafimow, D. Untangling the Theory of Planned Behavior's auxiliary assumptions and theoretical assumptions: Implications for predictive and intervention studies. New Ideas Psychol. 2021, 60, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budovska, V.; Torres Delgado, A.; Øgaard, T. Pro-environmental behaviour of hotel guests: Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour and social norms to towel reuse. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 20, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koklic, M.K.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K.; Zabkar, V. The interplay of past consumption, attitudes and personal norms in organic food buying. Appetite 2019, 137, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, H. Generational differences in perceptions of food health/risk and attitudes toward organic food and game meat: The case of the COVID-19 crisis in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miftari, I.; Haas, R.; Meixner, O.; Imami, D.; Gjokaj, E. Factors Influencing Consumer Attitudes towards Organic Food Products in a Transition Economy—Insights from Kosovo. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Ghosh, A.; Vashisht, D. The consumer perception and purchasing attitude towards organic food: A critical review. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 53, 578–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.U.; Zhang, Q.; Kubalek, J.; Al-Okaily, M. Beggars can’t be choosers: Factors influencing intention to purchase organic food in pandemic with the moderating role of perceived barriers. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 3249–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.H.; Nguyen, P.M. Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Norm Activation Model to Investigate Organic Food Purchase Intention: Evidence from Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loera, B.; Murphy, B.; Fedi, A.; Martini, M.; Tecco, N.; Dean, M. Understanding the purchase intentions for organic vegetables across EU: A proposal to extend the TPB model. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 4736–4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatwarnicka-Madura, B.; Nowacki, R.; Wojciechowska, I. Influencer Marketing as a Tool in Modern Communication—Possibilities of Use in Green Energy Promotion amongst Poland’s Generation Z. Energies 2022, 15, 6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, J.V.; Cook, L.A. Product knowledge and information processing of organic foods. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Diao, H.; Wu, L. Influence of the Framing Effect, Anchoring Effect, and Knowledge on Consumers’ Attitude and Purchase Intention of Organic Food. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-Y.; Chang, C.-C.; Lin, T.T. An analysis of purchase intentions toward organic food on health consciousness and food safety with/under structural equation modeling. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Broeckhoven, I.; Hung, Y.; Diem My, N.H.; De Steur, H.; Verbeke, W. Willingness to Pay for Food Labelling Schemes in Vietnam: A Choice Experiment on Water Spinach. Foods 2022, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items | Cronbach’s Alpha | Adapted From |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes towards purchasing green food products (AGFP) | AGFP 1. Purchasing green food products protects the natural environment. AGFP 2. When I buy green food products I am sure that I help protect my health. AGFP 3. When I buy green food products I am sure that I help protect my security. AGFP 4. I am sure that when I buy green food products, I buy products of higher quality. | 0.90 | [16,28,31] |

| Social norms (SN) | SN1. My family members buy green food products. SN2. My friends think that, I should choose green food products. | 0.77 | [24,35,46] |

| Perceived behavioural control (PCB) | PCB1. I can buy green food products even if they have a higher price. PCB2. I have the competence to search for green food products among others available in the store. PCB3. I have time to purchasing of green food products. PCB4. My current habits do not prevent me from purchasing green food products. PCB5. I have the income to buy green food products. | 0.73 | [29,47,48] |

| Trust for green food products (TGFP) | TGFP1. I trust producers to ensure high quality. TGFP2. I trust manufacturers for selling products that protect health and the environment. TGFP2. I trust to friendly production methods. TGFP3. I trust environmentally friendly methods in production. | 0.92 | [37] |

| Knowledge of green food products (KGFP) | KGFP 1. I have knowledge about green food. KGFP 2. I have knowledge of environmentally friendly production methods. KGFP 3. I have knowledge about certification and labeling of green food. KGFP 4. I have knowledge about the availability of green food. | 0.81 | [28,49,50,51] |

| Past behaviour (PB) | PB1. I have bought green food at least once a week in the last 3 months. PB2. I have extensive experience with purchasing for green food. PB3. I am satisfied with my past purchases of green food. | 0.70 | [52,53,54,55] |

| Intentions to purchase green food products (IGFP) | IGFP 1. I plan to buy green food products in the next 3 months. IGFP 2. I am sure that during my next purchasing I will buy an green food product, even if it has a higher price. IGFP 3. I am willing to pay a higher price for an green product. IGFP 4. I am willing to switch to the ecological version of the product, but if the price and quality are similar. | 0.73 | [22,28,29] |

| Metrics | Items | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–24 | 13% |

| 25–35 | 30% | |

| 36–45 | 28% | |

| 46–55 | 17% | |

| 55 and more | 12% | |

| Gender | Male | 30% |

| Female | 70% | |

| Place of residence | Village | 31% |

| Town, up to 40 thousand | 19% | |

| Town, from 40 thousand to 100 thousand | 13% | |

| City, from 100 thousand to 500 thousand | 12% | |

| City, above 500 thousand inhabitants | 25% | |

| Number of children | 0 | 23% |

| 1 | 1% | |

| 2 | 10% | |

| 3–4 | 47% | |

| 5 and more | 19% |

| Statements/Scale * | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchasing green food products protects the natural environment. | 1.38% | 3.23% | 7.85% | 20.77% | 23.38% | 20.77% | 22.62% |

| When I buy green food products I am sure that I help protect my health. | 2.62% | 3.54% | 10.62% | 24.00% | 27.69% | 30.15% | 2.62% |

| When I buy green food products I am sure that I help protect my security. | 4.31% | 18.00% | 22.00% | 26.00% | 25.08% | 4.31% | 18.00% |

| I am sure that when I buy green food products. I buy products of higher quality. | 2.00% | 2.92% | 6.77% | 18.77% | 27.23% | 21.54% | 20.77% |

| Statements/Scale * | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My family members buy green food products. | 13.85% | 15.38% | 19.38% | 20.46% | 15.69% | 8.62% | 6.62% |

| My friends think that. I should choose green food products. | 15.38% | 20.00% | 24.92% | 16.62% | 9.85% | 4.15% | 15.38% |

| Statements/Scale * | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I can buy green food products even if they have a higher price. | 22.31% | 22.00% | 20.92% | 12.62% | 8.62% | 5.08% | 8.46% |

| I have the competence to search for green food products among others available in the store. | 12.15% | 7.54% | 13.38% | 20.15% | 18.92% | 14.46% | 12.15% |

| I have time to purchasing of green food products. | 17.23% | 3.54% | 5.69% | 9.54% | 18.00% | 12.46% | 17.23% |

| My current habits do not prevent me from purchasing green food products. | 3.69% | 6.62% | 15.08% | 22.15% | 16.15% | 17.08% | 19.23% |

| I have the income to buy green food products. | 4.92% | 7.23% | 17.23% | 18.77% | 25.08% | 21.85% | 4.92% |

| Statements/Scale * | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I trust producers to ensure high quality. | 6.15% | 13.54% | 18.46% | 25.08% | 19.85% | 12.46% | 6.15% |

| I trust manufacturers for selling products that protect health and the environment. | 6.15% | 11.85% | 18.77% | 22.00% | 22.77% | 13.54% | 6.15% |

| I trust to friendly production methods. | 6.77% | 12.62% | 16.77% | 19.69% | 20.62% | 14.46% | 9.08% |

| I trust environmentally friendly methods in production. | 4.31% | 7.08% | 10.00% | 18.15% | 24.62% | 18.31% | 17.54% |

| Statements/Scale * | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have knowledge about green food. | 2.77% | 11.54% | 18.62% | 46.01% | 15.54% | 5.23% | 0.30% |

| I have knowledge of environmentally friendly production methods. | 2.77% | 6.00% | 13.23% | 22.31% | 25.85% | 17.08% | 12.77% |

| I have knowledge about certification and labeling of green food. | 11.08% | 18.62% | 29.69% | 18.46% | 10.31% | 6.62% | 11.08% |

| I have knowledge about the availability of green food. | 19.08% | 12.31% | 8.00% | 16.46% | 26.31% | 19.08% | 12.31% |

| Statements/Scale * | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have bought green food at least once a week in the last 3 months. | 18.31% | 10.46% | 15.85% | 13.08% | 19.85% | 14.0% | 8.46% |

| I have extensive experience with purchasing for green food. | 1.08% | 1.85% | 5.23% | 13.69% | 20.15% | 20.00% | 38.00% |

| I am satisfied with my past purchases of green food. | 17.38% | 20.92% | 26.92% | 12.46% | 5.38% | 3.23% | 17.38% |

| Statements/Scale * | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I plan to buy green food products in the next 3 months. | 17.69% | 14.77% | 14.92% | 14.77% | 13.85% | 10.46% | 13.54% |

| I am sure that during my next purchasing I will buy an green food product. even if it has a higher price. | 12.77% | 13.69% | 18.31% | 16.00% | 12.15% | 14.77% | 12.77% |

| I am willing to pay a higher price for an green product. | 6.46% | 10.31% | 11.69% | 19.85% | 26.15% | 12.31% | 13.23% |

| I am willing to switch to the ecological version of the product. but if the price and quality are similar. | 3.54% | 4.31% | 9.85% | 17.08% | 21.08% | 40.15% | 3.54% |

| Constructs | AGFP | SN | PCB | IGFP | PB | TGFP | KGFP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGFP | 1 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.43 |

| SN | 0.45 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.41 |

| PCB | 0.05 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.34 |

| IGFP | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.21 | 1 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.52 |

| PB | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.61 | 1 | 0.39 | 0.49 |

| TGFP | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 1 | 0.55 |

| KGFP | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 1 |

| Specification | b* | Std. Err. b* | b | Std. Err. b | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.113 | 0.669 | 4.657 | 0.000004 *** | ||

| PB (X1) | 0.338 | 0.032 | 0.586 | 0.055 | 10.647 | 0.000000 *** |

| AGFP (X2) | 0.310 | 0.033 | 0.337 | 0.036 | 9.357 | 0.000000 *** |

| SN (X3) | 0.146 | 0.031 | 0.265 | 0.057 | 4.695 | 0.000003 *** |

| KGFP (X4) | 0.120 | 0.034 | 0.175 | 0.050 | 3.505 | 0.000488 *** |

| TGFP (X5) | 0.067 | 0.034 | 0.123 | 0.062 | 1.971 | 0.049157 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Witek, L.; Kuźniar, W. Green Purchase Behaviour Gap: The Effect of Past Behaviour on Green Food Product Purchase Intentions among Individual Consumers. Foods 2024, 13, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13010136

Witek L, Kuźniar W. Green Purchase Behaviour Gap: The Effect of Past Behaviour on Green Food Product Purchase Intentions among Individual Consumers. Foods. 2024; 13(1):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13010136

Chicago/Turabian StyleWitek, Lucyna, and Wiesława Kuźniar. 2024. "Green Purchase Behaviour Gap: The Effect of Past Behaviour on Green Food Product Purchase Intentions among Individual Consumers" Foods 13, no. 1: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13010136