Can Non-farm Employment Improve Dietary Diversity of Left-Behind Family Members in Rural China?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

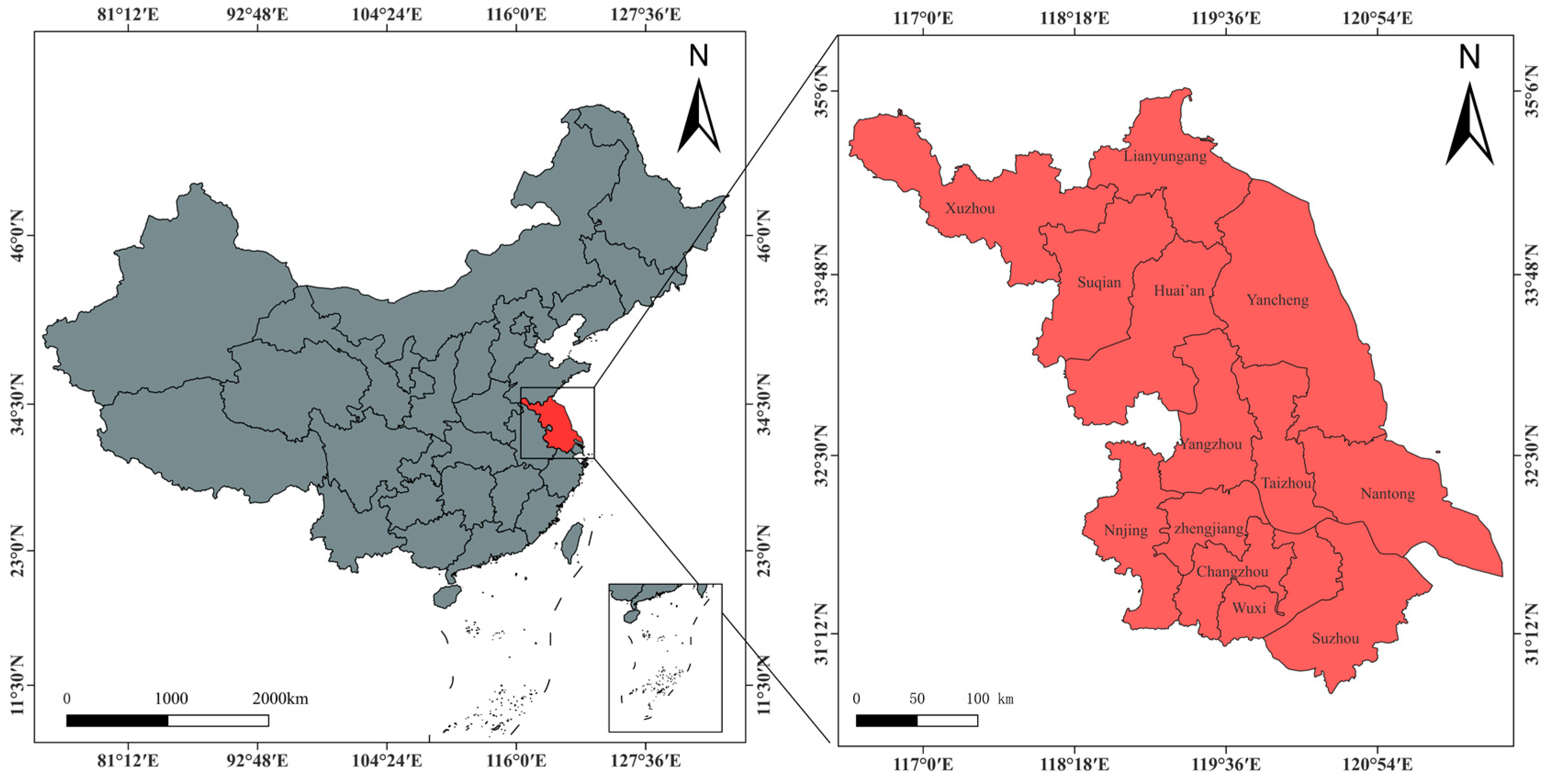

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Variable Design and Descriptive Statistics

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Key Independent Variable

3.2.3. Mechanism Variable

3.2.4. Instrumental Variable

3.2.5. Control Variable

3.3. Model

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Benchmark Regression

4.2. Endogenous Processing

4.3. Robustness Test

4.4. Impact Mechanism Testing

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, A.; Chai, L.; Liu, P. How much environmental burden does the shifting to nutritional diet bring? Evidence of dietary transformation in rural China. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 145, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; van Loo-Bouwman, C.; Zhang, Y.; Szeto, I.M.-Y. Dietary Diversity and Food Variety in Chinese Children Aged 3–17 Years: Are They Negatively Associated with Dietary Micronutrient Inadequacy? Nutrients 2018, 10, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Campos, B.C.; Peng, Y.; Glauben, T. Nutrition Transition with Accelerating Urbanization? Empirical Evidence from Rural China. Nutrients 2021, 13, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z. Does Internet use connect smallholder farmers to a healthy diet? Evidence from rural China. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, T.; Berg, M.v.D.; Heerink, N.; Cui, H.; Tan, F.; Fan, S. Can homestead gardens improve rural households’ vegetable consumption? Evidence from three provinces in China. Agribusiness 2023, 39, 1578–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Tang, S.; Chen, S.; Gong, S.; Jiang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Dietary Diversity and Nutrient Intake of Han and Dongxiang Smallholder Farmers in Poverty Areas of Northwest China. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arimond, M.; Wiesmann, D.; Becquey, E.; Carriquiry, A.; Daniels, M.C.; Deitchler, M.; Fanou-Fogny, N.; Joseph, M.L.; Kennedy, G.; Martin-Prevel, Y.; et al. Simple Food Group Diversity Indicators Predict Micronutrient Adequacy of Women’s Diets in 5 Diverse, Resource-Poor Settings. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 2059S–2069S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, S.; Delattre, C.; Karcheva-Bahchevanska, D.; Benbasat, N.; Nalbantova, V.; Ivanov, K. Plant-Based Diet as a Strategy for Weight Control. Foods 2021, 10, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.; Cudhea, F.; Singh, G.; Micha, R.; Shi, P.; Zhang, J.; Onopa, J.; Karageorgou, D.; Webb, P.; Mozaffarian, D. Estimated Global, Regional, and National Cardiovascular Disease Burdens Related to Fruit and Vegetable Consumption: An Analysis from the Global Dietary Database (FS01-01-19). Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz21–nzz28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, M.W.; Li, H.; Nekkalapudi, L.; Becerra, V.; Paredes, M. Nutritional Traits of Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris): Nutraceutical Characterization and Genomics. In Compendium of Crop Genome Designing for Nutraceuticals; Kole, C., Ed.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 611–638. ISBN 978-981-19-4169-6. [Google Scholar]

- Adesogan, A.T.; Havelaar, A.H.; McKune, S.L.; Eilittä, M.; Dahl, G.E. Animal source foods: Sustainability problem or malnutrition and sustainability solution? Perspective matters. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 25, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.P.; Allen, L.H. Nutritional importance of animal source foods. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3932S–3935S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Ni, D.; Taitz, J.; Pinget, G.V.; Read, M.; Senior, A.; Wali, J.A.; Nanan, R.; King, N.J.C.; Grau, G.E.; et al. Dietary protein increases T-cell-independent sIgA production through changes in gut microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta-Triana, F.; Verdejo-Bravo, C.; Fernandez-Perez, C.; Martin-Sanchez, F.J. Effect of Milk and Other Dairy Products on the Risk of Frailty, Sarcopenia, and Cognitive Performance Decline in the Elderly: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S105–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struijk, E.A.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Lopez-Garcia, E. Consumption of meat in relation to physical functioning in the Seniors-ENRICA cohort. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dror, D.K.; Allen, L.H. The importance of milk and other animal-source foods for children in low-income countries. Food Nutr. Bull. 2011, 32, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillenberger, M.; Neumann, C.G.; Murphy, S.P.; Bwibo, N.O.; Weiss, R.E.; Jiang, L.; Hautvast, J.G.A.J.; West, C.E. Intake of micronutrients high in animal-source foods is associated with better growth in rural Kenyan school children. Brit J. Nutr. 2006, 95, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, W.; Huang, J. Boosting rural labor off-farm employment through urban expansion in China. World Dev. 2022, 151, 105727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Sun, M.; Xu, X.; Bai, Y.; Fu, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, L. Non-farm employment promotes nutritious diet without increasing carbon footprint: Evidence from rural China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 369, 133273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.-L.; Zeng, X.-Y.; Fu, C.; Zhang, L.-X. Off-farm employment, agriculture production activities, and household dietary diversity in environmentally and economically vulnerable areas of Asia. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Hou, L.-L.; Hermann, W.; Huang, J.-K.; Mu, Y.-Y. The impact of migration on the food consumption and nutrition of left-behind family members: Evidence from a minority mountainous region of southwestern China. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1780–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.K. Urbanization and population aging: Converging trends of demographic transitions in modern world. Arch. Gerontol. Geriat 2022, 101, 104709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Hao, Y.; Ma, J. Family Income Level, Income Structure, and Dietary Imbalance of Elderly Households in Rural China. Foods 2024, 13, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Lv, M.; Qin, Y.; Li, K. Sleep quality in relation to social support and resilience among rural empty-nest older adults in China. Sleep. Med. 2021, 82, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, D.; Wu, X.-N.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Li, H.-P.; Wang, W.-L.; Zhang, J.-P.; Zhou, L.-S. Depression and social support between China’ rural and urban empty-nest elderly. Arch. Gerontol. Geriat 2012, 55, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, R.; Lu, J.; Xue, Y.; Hou, L.; Li, M.; Zheng, X.; Yang, T.; Zheng, J. Health promoting lifestyles and influencing factors among empty nesters and non-empty nesters in Taiyuan, China: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, G. A theory of social interactions. J. Polit. Econ. 1974, 82, 1063–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, Q.; Ho, K.W.; Ho, K.C. Altruism Within the Family: A Comparison of Father and Mother Using Life Happiness and Life Satisfaction. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 111, 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, K.S.; Gaiha, R.; Thapa, G. Does non-farm sector employment reduce rural poverty and vulnerability? Evidence from Vietnam and India. J. Asian Econ. 2015, 36, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Huang, J. Rural transformation, income growth, and poverty reduction by region in China in the past four decades. J. Integr. Agr. 2023, 22, 3582–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Vatsa, P.; Zheng, H.; Rahut, D.B. Nonfarm employment and consumption diversification in rural China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twumasi, M.A.; Zheng, H.; Asante, I.O.; Ntiamoah, E.B.; Amo-Ntim, G. The off-farm income and organic food expenditure nexus: Empirical evidence from rural Ghana. Cogent Food Agr. 2023, 9, 2258845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Y. Does off-farm work alleviate rural households’ energy poverty in China? Comparative analysis based on livelihood patterns. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 427, 139144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.C.; Gajanan, S.N.; Hallam, J.A. Chapter 4—Microeconomic Nutrition Policy. In Nutrition Economics; Babu, S.C., Gajanan, S.N., Hallam, J.A., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 43–62. ISBN 978-0-12-800878-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Chen, C.-P.; Li, Y.; Qin, L.; Qin, M. How Internet usage contributes to livelihood resilience of migrant peasant workers? Evidence from China. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 96, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkhowa, P.; Qaim, M. Mobile phones, off-farm employment and household income in rural India. J. Agric. Econ. 2022, 73, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, S. The Impact of Internet Use on Rural Women’s Off-Farm Work Participation: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, K.; Luo, Y. The bright side of digitization: Assessing the impact of mobile phone domestication on left-behind children in China’s rural migrant families. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1003379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellacci, F.; Tveito, V. Internet use and well-being: A survey and a theoretical framework. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhao, Q.-R.; Glauben, T.; Si, W. The impact of Internet access on household dietary quality: Evidence from rural China. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, X. Internet use and Chinese older adults? Subjective well-being (SWB): The role of parent-child contact and relationship. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, X. The Relationship between WeChat Use by Chinese Urban Older Adults Living Alone and Their Subjective Well-Being: The Mediation Role of Intergenerational Support and Social Activity. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1543–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Tang, Z. Should manufacturers open live streaming shopping channels? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S. Employment, emerging labor markets, and the role of education in rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2002, 13, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ruan, J. Cultural diversity, social network, and off-farm employment: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 89, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Xu, D.; Liu, S. Social Network Influences on Non-Agricultural Employment Quality for Part-Time Peasants: A Case Study of Sichuan Province, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Lee, C.-C.; Morrison, A.M. The effects of foreign product demand-labor transfer nexus on human capital investment in China. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Vatsa, P.; Ma, W. Can mechanized pesticide application help reduce pesticide use and increase crop yield? Evidence from rice farmers in Jiangsu province, China. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2227809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wen, X.; Liu, X. The Mediating Role of Psychological Balance on the Effects of Dietary Behavior on Cognitive Impairment in Chinese Elderly. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2227809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Zhen, L.; Wei, Y. Changes in Household Dietary Diversity in Herder Communities over the Past 20 Years: Evidence from Xilin Gol Grassland of China. Foods 2023, 12, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gina, K.; Terri, B.; MarieClaude, D. Guidelines for Measuring Household and Individual Dietary Diversity; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Tian, X. Food accessibility, diversity of agricultural production and dietary pattern in rural China. Food Policy 2019, 84, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H. The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Consumption and Dietary Quality of Rural Households in China. Foods 2022, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Shen, Y. Effects of land transfer quality on the application of organic fertilizer by large-scale farmers in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 105124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grable, J.E.; Cupples, S.; Fernatt, F.; Anderson, N. Evaluating the Link between Perceived Income Adequacy and Financial Satisfaction: A Resource Deficit Hypothesis Approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 1109–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Shan, L.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, Y. Internet accessibility and incident depressive symptoms in middle aged and older adults in China: A national longitudinal cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 340, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthelon, M.; Bettinger, E.; Kruger, D.I.; Montecinos-Pearce, A. The Structure of Peers: The Impact of Peer Networks on Academic Achievement. Res. High. Educ. 2019, 60, 931–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.E.; De Brauw, A. Migration and Incomes in Source Communities: A New Economics of Migration Perspective from China. Econ. Dev. Cult. 2003, 52, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wei, T.; Zhu, N. Determinants of Consumption Structure of Livestock Products among Rural Chinese Residents: Household Characteristics and Regional Heterogeneity. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Food Group | Consumption (g) | Recommended Scope (g) |

|---|---|---|

| Grains | 200–300 | |

| Score = 1 | 200–300 | |

| Score = 0.5 | 100–200 or 300–450 | |

| Score = 0 | Else | |

| Potatoes | 50–100 | |

| Score = 1 | 50–100 | |

| Score = 0.5 | 25–50 or 100–150 | |

| Score = 0 | Else | |

| Beans | 25–35 | |

| Score = 1 | 25–35 | |

| Score = 0.5 | 12.5–25 or 35–52.5 | |

| Score = 0 | Else | |

| Vegetables | 300–500 | |

| Score = 1 | 300–500 | |

| Score = 0.5 | 150–300 or 500–750 | |

| Score = 0 | Else | |

| Fruits | 200–350 | |

| Score = 1 | 200–350 | |

| Score = 0.5 | 100–200 or 350–525 | |

| Score = 0 | Else | |

| Meat | 40–75 | |

| Score = 1 | 40–75 | |

| Score = 0.5 | 20–40 or 75–112.5 | |

| Score = 0 | Else | |

| Eggs | 40–50 | |

| Score = 1 | 40–50 | |

| Score = 0.5 | 20–40 or 50–75 | |

| Score = 0 | Else | |

| Aquatic products | 40–75 | |

| Score = 1 | 40–75 | |

| Score = 0.5 | 20–40 or 75–112.5 | |

| Score = 0 | Else | |

| Milk | 300–500 | |

| Score = 1 | 300–500 | |

| Score = 0.5 | 150–300 or 500–750 | |

| Score = 0 | Else |

| Variable Type | Variable Definition | Variable Description and Assignment | Mean Value | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Dietary diversity | Dietary diversity score | 7.261 | 1.542 |

| Animal-based food diversity | Animal-based food diversity score | 3.061 | 0.946 | |

| Plant-based food diversity | Plant-based food diversity score | 4.200 | 0.920 | |

| Chinese Food Guide Pagoda | Chinese Food Guide Pagoda score | 2.990 | 1.154 | |

| Independent variable | Non-farm employment | Number of family non-farm employment | 1.631 | 1.249 |

| Mechanism variable | Income quality | Annual household income (logarithmic) | 10.992 | 1.157 |

| Satisfaction with family life prosperity (housing area, disposable income, etc.) | 3.622 | 0.917 | ||

| Internet accessibility | Number of home smartphones | 2.484 | 1.675 | |

| Number of computers with Internet access at home | 0.603 | 0.901 | ||

| Education level | Number of higher education talents | 0.493 | 0.752 | |

| Annual education expenditure (logarithmic) | 3.338 | 4.414 | ||

| Control variable | Age | Age (years) | 61.575 | 11.388 |

| Age2 | Age squared term/100 | 39.211 | 13.233 | |

| Gender | Male = 1; Female = 0 | 0.715 | 0.452 | |

| Education | Education level (years in school) | 7.032 | 3.965 | |

| Cadre | Do you have a position in this village? Yes = 1, No = 0 | 0.152 | 0.359 | |

| Health | Self-perceived health status (1 = loss of labor ability; 2 = poor; 3 = moderate; 4 = good; 5 = excellent) | 3.974 | 1.070 | |

| Land scale | Contracted land area (hectare) | 0.189 | 0.822 | |

| The number of people eating at home | The number of people eating at home in the past week | 2.988 | 1.816 | |

| Distance | The distance from the village committee to the nearest highway entrance (kilometers) | 13.030 | 16.209 | |

| Instrumental variable | The proportion of non-farm employment households in the village | The proportion of households in non-farm employment in the sample at the village level | 0.777 | 0.102 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal-Based Foods | Plant-Based Foods | Dietary Diversity | |

| Non-farm employment | 0.033 *** | 0.027 ** | 0.060 *** |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.021) | |

| Age | −0.013 | 0.018 ** | 0.005 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.014) | |

| Age2 | 0.008 | −0.018 ** | −0.009 |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.012) | |

| Gender | −0.004 | 0.002 | −0.001 |

| (0.031) | (0.031) | (0.050) | |

| Education | 0.038 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.064 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.006) | |

| Cadre | 0.123 *** | 0.062 * | 0.185 *** |

| (0.033) | (0.035) | (0.056) | |

| Health | 0.067 *** | 0.044 *** | 0.111 *** |

| (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.022) | |

| Land scale | 0.020 | 0.014 * | 0.034 * |

| (0.013) | (0.008) | (0.020) | |

| Number of people eating at home | 0.086 *** | 0.061 *** | 0.147 *** |

| (0.024) | (0.018) | (0.042) | |

| Distance | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| Time fixed effects | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional fixed effects | YES | YES | YES |

| _cons | 2.666 *** | 3.210 *** | 5.876 *** |

| (0.262) | (0.267) | (0.459) | |

| N | 4892 | 4892 | 4892 |

| R2 | 0.148 | 0.082 | 0.130 |

| Variable | Animal-Based Foods | Plant-Based Foods | Dietary Diversity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 2 | Phase 1 | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | |

| Non-farm employment | 0.253 *** (0.089) | 0.377 *** (0.092) | 0.630 *** (0.157) | |||

| Instrumental variable | 2.240 *** (0.234) | 2.240 *** (0.234) | 2.240 *** (0.234) | |||

| Control variable | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| F-statistic | 88.214 | 88.214 | 88.214 | |||

| N | 4892 | 4892 | 4892 | 4892 | 4892 | 4892 |

| OLS | 2SLS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) CFGPS | (2) Phase 2 | (3) Phase 1 |

| Non-farm employment | 0.017 | 0.295 *** | |

| (0.016) | (0.114) | ||

| Instrumental variable | 2.240 *** | ||

| (0.234) | |||

| Control variable | YES | YES | YES |

| Time fixed effects | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional fixed effects | YES | YES | YES |

| R2 | 0.062 | ||

| F-statistic | 88.214 | ||

| N | 4892 | 4892 | 4892 |

| Income Level | Internet Accessibility | Education Level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) Income | (2) Satisfaction | (3) Smartphones | (4) Computers | (5) Higher Education | (6) Education Expenditure |

| Non-farm employment | 0.274 *** | 0.053 *** | 0.483 *** | 0.129 *** | 0.203 *** | 0.246 *** |

| (0.021) | (0.011) | (0.026) | (0.011) | (0.010) | (0.078) | |

| Control variable | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 2101 | 4874 | 4828 | 4892 | 4892 | 4771 |

| R² | 0.377 | 0.094 | 0.359 | 0.188 | 0.220 | 0.258 |

| Animal-Based Foods | Plant-Based Foods | Dietary Diversity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) Couple | (2) Alone | (3) Couple | (4) Alone | (5) Couple | (6) Alone |

| Non-farm employment | 0.025 | −0.010 | −0.000 | −0.031 | 0.025 | −0.041 |

| (0.019) | (0.052) | (0.021) | (0.055) | (0.034) | (0.088) | |

| Control variable | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Regional fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 1244 | 313 | 1244 | 313 | 1244 | 313 |

| R2 | 0.104 | 0.197 | 0.071 | 0.126 | 0.096 | 0.173 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T. Can Non-farm Employment Improve Dietary Diversity of Left-Behind Family Members in Rural China? Foods 2024, 13, 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13121818

Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wang T. Can Non-farm Employment Improve Dietary Diversity of Left-Behind Family Members in Rural China? Foods. 2024; 13(12):1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13121818

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yonghu, Yifeng Zhang, and Tingjin Wang. 2024. "Can Non-farm Employment Improve Dietary Diversity of Left-Behind Family Members in Rural China?" Foods 13, no. 12: 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13121818

APA StyleZhang, Y., Zhang, Y., & Wang, T. (2024). Can Non-farm Employment Improve Dietary Diversity of Left-Behind Family Members in Rural China? Foods, 13(12), 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13121818