Mediating Roles of Perceived Quality and Perceived Behaviour Control in Shaping Chinese Consumer’s Purchase Intention for Domestic Infant Milk Formula (IMF)

Abstract

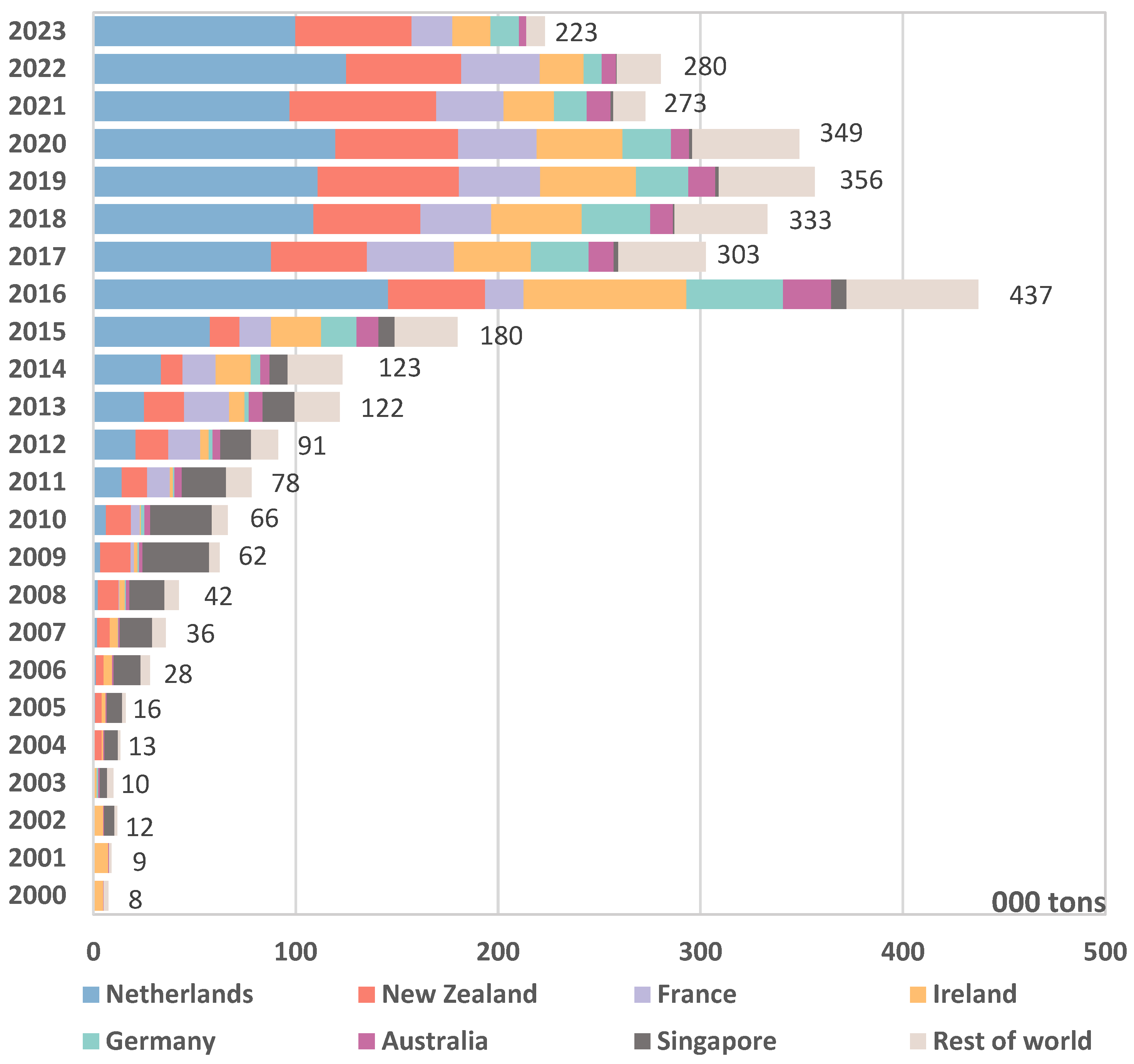

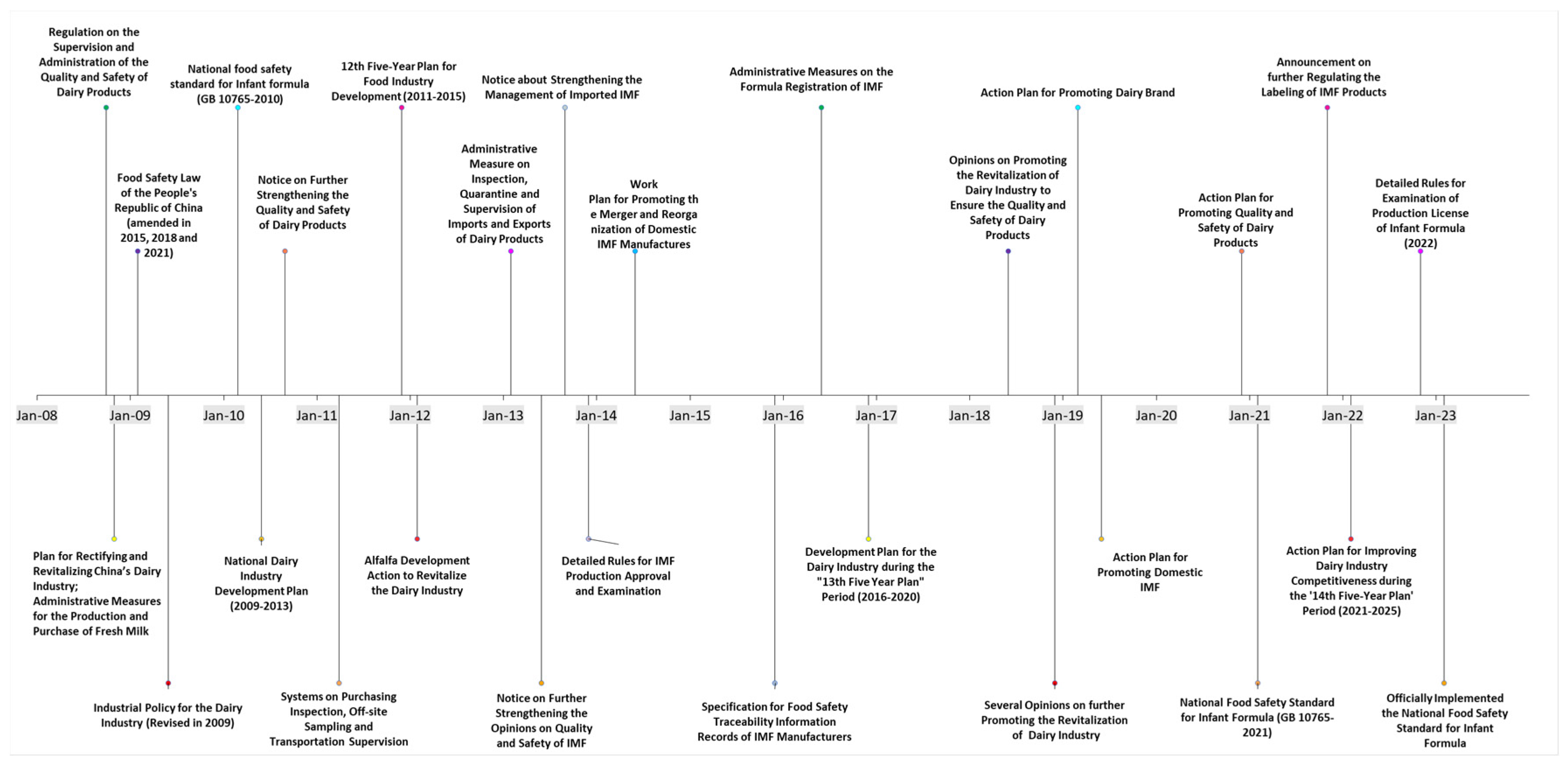

1. Introduction

2. Study Background and Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

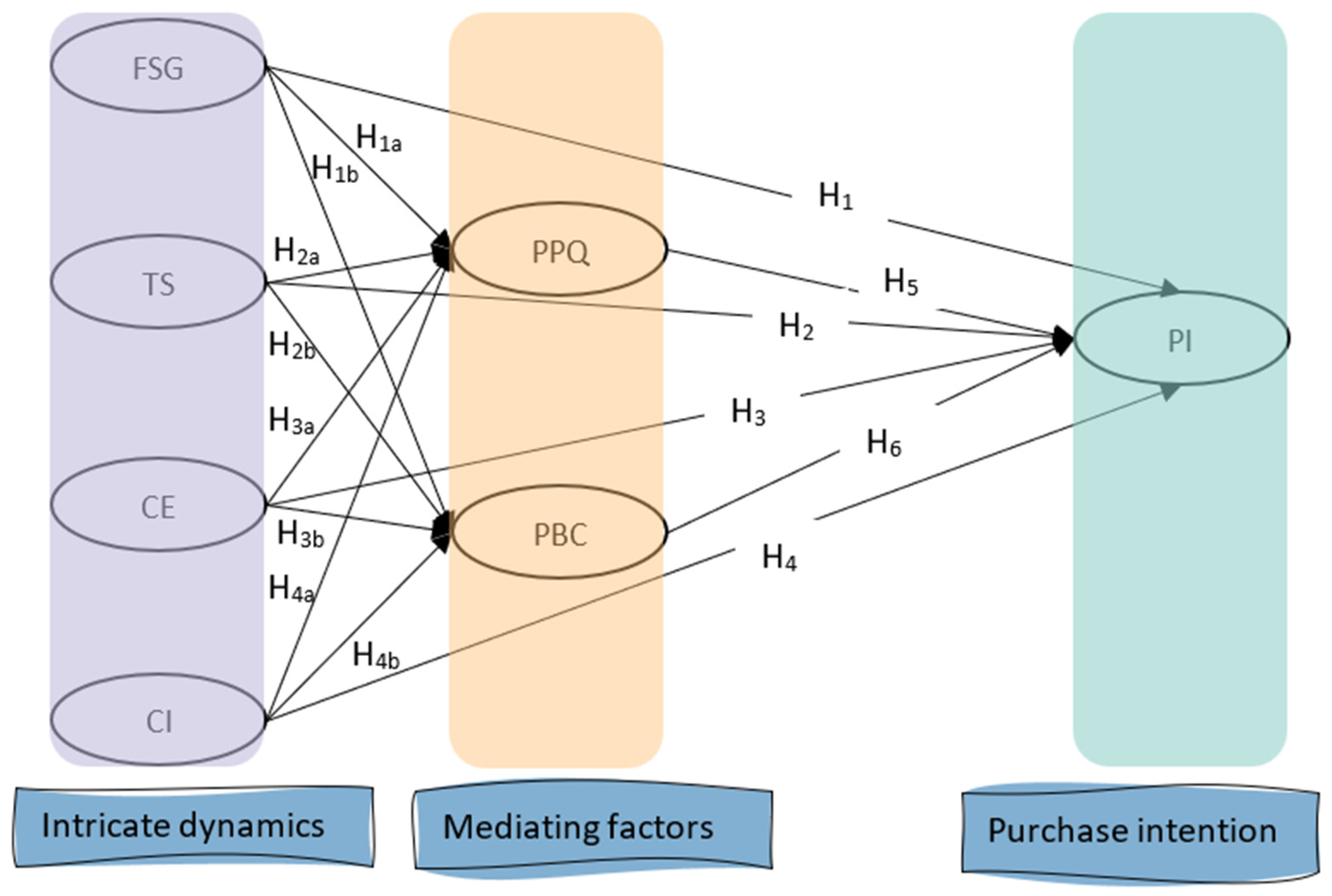

3.1. Hypotheses Development and Conceptual Model

3.1.1. Food Safety Governance (FSG)

3.1.2. Trust in Stakeholders (TS)

3.1.3. Consumer Ethnocentrism (CE)

3.1.4. Impact of COVID-19 (CI)

3.1.5. Perceived Product Quality (PPQ)

3.1.6. Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC)

3.2. Data Analysis

3.3. Data Collection

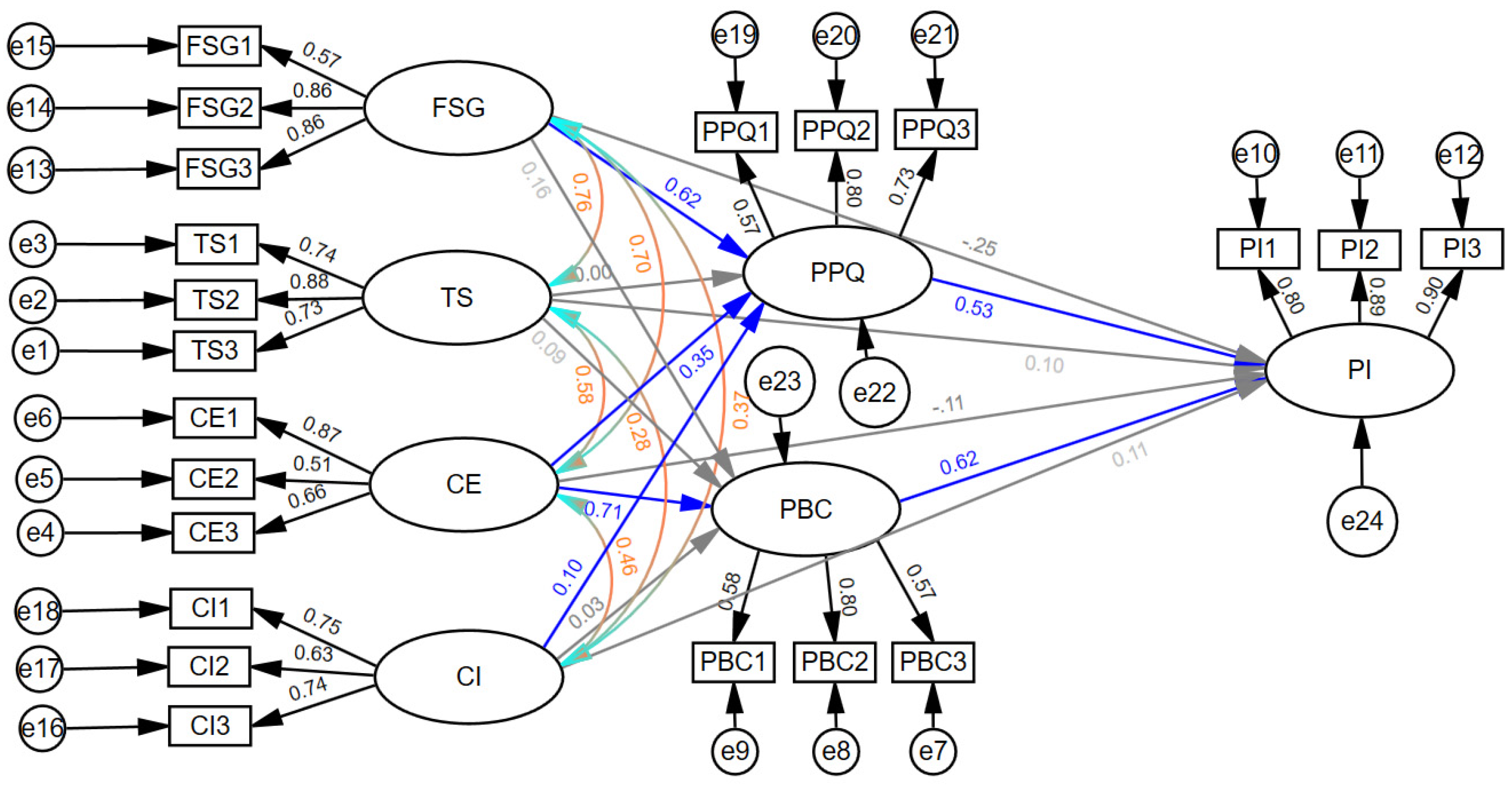

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.2. Structural Model Fit

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiu, C.; Klein, K.K. Melamine in milk products in China: Examining the factors that led to deliberate use of the contaminant. Food Policy 2010, 35, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custance, P.; Walley, K.; Jiang, D. Crisis brand management in emerging markets: Insight from the Chinese infant milk powder scandal. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Guo, T.; Klein, K.K. Melamine and other food safety and health scares in China: Comparing households with and without young children. Food Control 2012, 26, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yin, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, D. Effectiveness of China’s organic food certification policy: Consumer preferences for infant milk formula with different organic certification labels. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 62, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Ramsaran, R.; Wibowo, S. An investigation into the perceptions of Chinese consumers towards the country-of-origin of dairy products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Benni, N.; Stolz, H.; Home, R.; Kendall, H.; Kuznesof, S.; Clark, B.; Dean, M.; Brereton, P.; Frewer, L.J.; Chan, M.Y. Product attributes and consumer attitudes affecting the preferences for infant milk formula in China–a latent class approach. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.C.; Li, C.; Yu, Z.; Regan, Á.; Lu, T.; Wall, P. Consumer perceptions on the origin of infant formula: A survey with urban Chinese mothers. J. Dairy Res. 2021, 88, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.L.; Wang, H.H.; Olynk, N.J.; Wu, L.; Bai, J. Chinese consumers’ demand for food safety attributes: A push for government and industry regulations. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2012, 94, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Gao, Z.; Heng, Y.; Shi, L. Chinese consumers’ preferences for food quality test/measurement indicators and cues of milk powder: A case of Zhengzhou, China. Food Policy 2019, 89, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y. Consumer preference and willingness to pay for the traceability information attribute of infant milk formula: Evidence from a choice experiment in China. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Kornelis, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, S. Consumer confidence in the safety of milk and infant milk formula in China. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 8807–8818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Q.; Jackson, P. Consuming anxiety? Parenting practices in China after the infant formula scandal. Food Cult. Soc. 2012, 15, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitiniyazi, S.; Canavari, M. Exploring Chinese consumers’ attitudes toward traceable dairy products: A focus group study. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11257–11267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Tacken, G.M.; Liu, Y.; Sijtsema, S.J. Consumer trust in the dairy value chain in China: The role of trustworthiness, the melamine scandal, and the media. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 8554–8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Fang, L. Consumer Willingness to pay for food safety attributes in China: A meta-analysis. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2021, 33, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Peng, H.; Dong, X.; Li, L.; Zhu, W. Consumers’ brand preferences for infant formula: A grounded theory approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Waldron, S.; Dong, X. Evidence from a Choice Experiment in Consumer Preference towards Infant Milk Formula (IMF) in the Context of Dairy Revitalization and COVID-19 Pandemic. Foods 2022, 11, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.T. Rising Nationalism Spurs Chinese Consumers to Go Local. 2021. Available online: https://en.nikkoam.com/articles/2021/rising-nationalism-spurs-chinese-consumers-local#:~:text=Since%202018%2C%20Chinese%20consumers%20by,Chinese%20products%20in%20recent%20years (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- CBBC (China-Britian Business Council). The Rise and Fall of Guochao: China’s Nationalistic Branding Phenomenon. 2023. Available online: https://focus.cbbc.org/the-rise-and-fall-of-guochao-chinas-nationalistic-branding-phenomenon/ (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Zhou, C. China’s Domestic Brands Boom, Fuelled by Nationalism, with Li-Ning, Anta Standing Out from the Crowd. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3142815/chinas-domestic-brands-boom-fuelled-nationalism-li-ning-anta (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Zipser, D.; Hui, D.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, C. McKinsey China Consumer Report: A Time of Resilience. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/cn/~/media/mckinsey/locations/asia/greater%20china/our%20insights/2023%20mckinsey%20china%20consumer%20report%20a%20time%20of%20resilience/2023%20mckinsey%20china%20consumer%20report%20en.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Global Times. Huawei Mate 60 Pro Triggers Buying Spree among Chinese Consumers. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202309/1297757.shtml (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Hobbs, J.E. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 68, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Saxena, T.; Purohit, N. The new consumer behaviour paradigm amid COVID-19: Permanent or transient? J. Health Manag. 2020, 22, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, M. China Backs Local Infant Formula—But Weak Birth Rate Threatens Whole Market. Just Food. 2022. Available online: https://www.just-food.com/analysis/china-backs-local-infant-formula-but-weak-birth-rate-threatens-whole-market/?cf-view (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Bowes, M. Baby Bust Wipes $480m Off Company. Available online: https://www.news.com.au/finance/business/other-industries/480m-wiped-off-aussie-company-in-one-day/news-story/13325c2e94222a74eb25cca091eb0e66 (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Master, F. Analysis: New Rules Set to Shake Up China’s Shrinking Infant Formula Market. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/new-rules-set-shake-up-chinas-shrinking-infant-formula-market-2023-06-19/ (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Dalal, R.P.; Goldfarb, D.S. Melamine-related kidney stones and renal toxicity. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2011, 7, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, A.K.C.; Kwan, T.H.; Li, P.K.T. Melamine toxicity and the kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, C.G.; Thomas, J.D.; Osterloh, J.D. Melamine toxicity. J. Med. Toxicol. 2010, 6, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Interim Melamine and Analogues Safety/Risk Assessment. Available online: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170111174252/http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodborneIllnessContaminants/ChemicalContaminants/ucm164658.htm (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- WHO. Toxicological and Health Aspects of Melamine and Cyanuric Acid: Report of a WHO Expert Meeting in Collaboration with FAO, Supported by Health Canada, Ottawa, Canada, 1–4 December 2008. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44106/9789241597951_eng.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- Pei, X.; Tandon, A.; Alldrick, A.; Giorgi, L.; Huang, W.; Yang, R. The China melamine milk scandal and its implications for food safety regulation. Food Policy 2011, 36, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Song, P.; Wen, J. Melamine and food safety: A 10-year review. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 30, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Guo, T.; Klein, K.K. Melamine in Chinese milk products and consumer confidence. Appetite 2010, 55, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.W.; Chen, Z.H.U.; Chen, Q.H.; Liu, Y.M. Consumer confidence and consumers’ preferences for infant formulas in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1793–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Comtrade. UN Comtrade Database. Available online: https://comtrade.un.org/ (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- State Council Policy Document Library. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengcewenjianku/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs—Policies and Regulations. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/gk/zcfg/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- State Administration for Market Regulation. Available online: https://www.samr.gov.cn/zw/index.html (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- National Development and Reform Committee. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. Available online: https://www.miit.gov.cn/zwgk/index.html (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- SAMR (State Administration for Market Regulation). Measures for the Registration and Administration of Infant Milk Formula. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2016/content_5145569.htm (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- MARA (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China). The 13th China Dairy Industry Conference and the 2022 China Dairy Top 20 (D20) Summit Were Held in Jinan, Shandong. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/xw/zwdt/202209/t20220906_6408797.htm (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- China Customs. Customs Statistical Data Online Inquiry Platform. Available online: http://stats.customs.gov.cn/ (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Loxton, M.; Truskett, R.; Scarf, B.; Sindone, L.; Baldry, G.; Zhao, Y. Consumer behaviour during crises: Preliminary research on how coronavirus has manifested consumer panic buying, herd mentality, changing discretionary spending and the role of the media in influencing behaviour. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Manikas, A.S.; Barone, M.J. (Not) near and dear: COVID-19 concerns increase consumer preference for products that are not “near me”. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2022, 7, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia, M.; Grashuis, J.; Skevas, T. Consumer preferences for grocery purchasing during the COVID-19 pandemic: A quantile regression approach. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 3595–3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HTI (Hai Tong International). IMF—Structural Opportunities in Stable Market. China Staples Research Report. Available online: https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202204281562141678_1.pdf?1651165454000.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Bettman, J.R. Consumer psychology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1986, 37, 257–289. Available online: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev.ps.37.020186.001353 (accessed on 26 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Morwitz, V.G.; Kumar, V. Sales forecasts for existing consumer products and services: Do purchase intentions contribute to accuracy? Int. J. Forecast. 2000, 16, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.; Shin, J.T.; Kim, Y.W. An exploration and investigation of edible insect consumption: The impacts of image and description on risk perceptions and purchase intent. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Z.; Liu, X.; Gao, H. Exploring the mechanism of consumer purchase intention in a traditional culture based on the theory of planned behavior. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1110191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.G. Purchase intentions and purchase behavior. J. Mark. 1979, 43, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullet, G.M.; Karson, M.J. Analysis of purchase intent scales weighted by probability of actual purchase. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, C.R.; Klemz, B.R.; Boshoff, C. Managerial implications of predicting purchase behavior from purchase intentions: A retail patronage case study. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.A.; Taylor, D.C. Experimental approach to assessing actual wine purchase behavior. Int. J. Wine Res. 2013, 25, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, C.S.; Ariff, M.S.B.M.; Zakuan, N.; Tajudin, M.N.M.; Ismail, K.; Ishak, N. Consumers perception, purchase intention and actual purchase behavior of organic food products. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2014, 3, 378. Available online: https://vwww.sibresearch.org/uploads/3/4/0/9/34097180/riber_b14-173_378-397.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Morwitz, V.G.; Schmittlein, D. Using segmentation to improve sales forecasts based on purchase intent: Which “intenders” actually buy? J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemmaor, A.C. Predicting behavior from intention-to-buy measures: The parametric case. J. Mark. Res. 1995, 32, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morwitz, V.G.; Steckel, J.H.; Gupta, A. When do purchase intentions predict sales? Int. J. Forecast. 2007, 23, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Tiwari, M.K.; Chan, F.T. Predicting the consumer’s purchase intention of durable goods: An attribute-level analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Jiang, H.; Deng, H.; Zhang, T. The influence of the diffusion of food safety information through social media on consumers’ purchase intentions: An empirical study in China. Data Technol. Appl. 2019, 53, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.Y.; Chang, C.C.; Lin, T.T. Triple bottom line model and food safety in organic food and conventional food in affecting perceived value and purchase intentions. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wright, M.J.; Gao, H.; Liu, H.; Mather, D. The effects of brand origin and country-of-manufacture on consumers’ institutional perceptions and purchase decision-making. Int. Mark. Rev. 2021, 38, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Guo, X.; Guo, J.; Wu, J. China’s dairy crisis: Impacts, causes and policy implications for a sustainable dairy industry. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2011, 18, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guan, L.; Jin, S. Trust and consumer confidence in the safety of dairy products in China. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 3644–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimp, T.A.; Sharma, S. Consumer ethnocentrism: Construction and validation of the CETSCALE. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlegh, P.W.; Steenkamp, J.B.E. A review and meta-analysis of country-of-origin research. J. Econ. Psychol. 1999, 20, 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankarmahesh, M.N. Consumer ethnocentrism: An integrative review of its antecedents and consequences. Int. Mark. Rev. 2006, 23, 146–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siamagka, N.T.; Balabanis, G. Revisiting consumer ethnocentrism: Review, reconceptualization, and empirical testing. J. Int. Mark. 2015, 23, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, B.N.; Khanh Giao, H.N. The impact of perceived brand globalness on consumers’ purchase intention and the moderating role of consumer ethnocentrism: An evidence from Vietnam. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2020, 32, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ramaswamy, V.; Alden, D.L.; Steenkamp, J.B.E.; Ramachander, S. Effects of brand local and nonlocal origin on consumer attitudes in developing countries. In Cultural Psychology, 1st ed.; Maheswaran, D., Shavitt, S., Eds.; Psychology Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2014; pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rammal, H.G.; Rose, E.L.; Ghauri, P.N.; Jensen, P.D.Ø.; Kipping, M.; Petersen, B.; Scerri, M. Economic nationalism and internationalization of services: Review and research agenda. J. World Bus. 2022, 57, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekakis, E.J. Economic nationalism and the cultural politics of consumption under austerity: The rise of ethnocentric consumption in Greece. J. Consum. Cult. 2017, 17, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.Y. Consumer Nationalism in China: Examining its Critical Impact on Multinational Businesses, 1st ed.; Anthem Press: London, UK, 2024; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- El Banna, A.; Papadopoulos, N.; Murphy, S.A.; Rod, M.; Rojas-Méndez, J.I. Ethnic identity, consumer ethnocentrism, and purchase intentions among bi-cultural ethnic consumers: “Divided loyalties” or “dual allegiance”? J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, P.; Boffelli, A.; Elia, S.; Fratocchi, L.; Kalchschmidt, M.; Samson, D. What can we learn about reshoring after COVID-19? Oper. Manag. Res. 2020, 13, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou-Llusar, J.C.; Camisón-Zornoza, C.; Escrig-Tena, A.B. Measuring the relationship between firm perceived quality and customer satisfaction and its influence on purchase intentions. Total Qual. Manag. 2001, 12, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tao, J.; Chu, M. Behind the label: Chinese consumers’ trust in food certification and the effect of perceived quality on purchase intention. Food Control 2020, 108, 106825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions in relation to organic foods in Taiwan: Moderating effects of food-related personality traits. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 1008–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Chung, J.E. Consumer purchase intention for organic personal care products. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Hancer, M. The role of attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and moral norm in the intention to purchase local food products. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, C.; Dong, H.; Lee, Y.A. Factors influencing consumers’ purchase intention of green sportswear. Fash. Text. 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Wang, X.; Nasiri, A.; Ayyub, S. Determinant factors influencing organic food purchase intention and the moderating role of awareness: A comparative analysis. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 63, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitiniyazi, S.; Canavari, M. Understanding Chinese consumers’ safety perceptions of dairy products: A qualitative study. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 1837–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Mediation Analysis. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R; Classroom Companion: Business; Hair, J.F.M., Jr., Hult, G.T., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N.P., Ray, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, R.; Cote, J.A.; Baumgartner, H. Multicollinearity and measurement error in structural equation models: Implications for theory testing. Mark. Sci. 2004, 23, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C.K. An SAS macro for implementing the modified Bollen-Stine bootstrap for missing data: Implementing the bootstrap using existing structural equation modeling software. Struct. Equ. Model. 2005, 12, 620–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koemle, D.; Yu, X. Choice experiments in non-market value analysis: Some methodological issues. For. Econ. Rev. 2020, 2, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; Van Trijp, H.; Jan Renes, R.; Frewer, L. Understanding consumer confidence in the safety of food: Its two-dimensional structure and determinants. Risk Anal. 2007, 27, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; Van Trijp, J.C.M.; van der Lans, I.A.; Renes, R.J.; Frewer, L.J. How trust in institutions and organizations builds general consumer confidence in the safety of food: A decomposition of effects. Appetite 2008, 51, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; Van Trijp, H.; Goddard, E.; Frewer, L. Consumer confidence in the safety of food in Canada and the Netherlands: The validation of a generic framework. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; Van Trijp, H.; Renes, R.J.; Frewer, L.J. Consumer confidence in the safety of food and newspaper coverage of food safety issues: A longitudinal perspective. Risk Anal. 2010, 30, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yieh, K.; Chiao, Y.C.; Chiu, Y.K. Understanding the antecedents to customer loyalty by applying structural equation modeling. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2007, 18, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Laroche, M.; Papadopoulos, N. Cosmopolitanism, consumer ethnocentrism, and materialism: An eight-country study of antecedents and outcomes. J. Int. Mark. 2009, 17, 116–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voon, J.P.; Ngui, K.S.; Agrawal, A. Determinants of willingness to purchase organic food: An exploratory study using structural equation modeling. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 103–120. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1875186 (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Al-Gahtani, S.S. Empirical investigation of e-learning acceptance and assimilation: A structural equation model. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2016, 12, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.M.; Bayat, A.; Olutuase, S.O.; Abdul Latiff, Z.A. Factors affecting consumers’ intention towards purchasing halal food in South Africa: A structural equation modelling. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2019, 25, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Huang, I.Y.; Manning, L. The role of media reporting in food safety governance in China: A dairy case study. Food Control 2019, 96, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miftari, I.; Cerjak, M.; Tomic Maksan, M.; Imami, D.; Prenaj, V. Consumer ethnocentrism and preference for domestic wine in times of COVID-19. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2021, 123, 103–113. Available online: http://real.mtak.hu/136228/1/2173_Prenaj.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Yang, R.; Ramsaran, R.; Wibowo, S. Do consumer ethnocentrism and animosity affect the importance of country-of-origin in dairy products evaluation? The moderating effect of purchase frequency. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook 2022. 2022. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/Statisticaldata/yearbook/ (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B. A focus on reliability in developmental research through Cronbach’s Alpha among medical, dental and paramedical professionals. Asian Pac. J. Health Sci. 2016, 3, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujang, M.A.; Omar, E.D.; Baharum, N.A. A review on sample size determination for Cronbach’s alpha test: A simple guide for researchers. Malays. J. Med. Sci. MJMS 2018, 25, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, B.; Muthen, B.; Alwin, D.F.; Summers, G.F. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociol. Methodol. 1977, 8, 84–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modelling, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, B.M. The ethical use of fit indices in structural equation modeling: Recommendations for psychologists. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 783226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, A.; Dillon, W.R. A simulation study to investigate the use of cutoff values for assessing model fit in covariance structure models. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Evaluating model fit: A synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, London, UK, 19–20 June 2008; pp. 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: New Boston, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 6, pp. 497–516. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X.; Yu, H.; Ploeger, A. Exploring influential factors including COVID-19 on green food purchase intentions and the intention–behaviour gap: A qualitative study among consumers in a Chinese context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyarugwe, S.P.; Linnemann, A.R.; Ren, Y.; Bakker, E.J.; Kussaga, J.B.; Watson, D.; Fogliano, V.; Luning, P.A. An intercontinental analysis of food safety culture in view of food safety governance and national values. Food Control 2020, 111, 107075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.L.; Nien, H.P. Who are ethnocentric? Examining consumer ethnocentrism in Chinese societies. J. Consum. Behav. 2008, 7, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Gunessee, S.; Hoffmann, R.; Hui, W.; Larner, J.; Ma, Q.P.; Thompson, F.M. Chinese consumer ethnocentrism: A field experiment. J. Consum. Behav. 2012, 11, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.Q. Chinese products for Chinese people? Consumer ethnocentrism in China. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.M.; Guo, C. How consumer ethnocentrism (CET), ethnocentric marketing, and consumer individualism affect ethnocentric behavior in China. J. Glob. Mark. 2018, 31, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.M.; Nam, H. How inter-country similarities moderate the effects of consumer ethnocentrism and cosmopolitanism in out-group country perceptions: An Asian perspective. Int. Mark. Rev. 2020, 37, 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Chen, R.; Zuo, Y.; Liu, R.; Gong, R.; Huang, L.; Chen, C.; Xue, B. Why do Chinese people prefer domestic products: The role of consumer ethnocentrism, social norms and national identity. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 2582–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, B. Chinese Parents Increasingly Trust and Buy Local Infant Formula Brands. The China Project. 2022. Available online: https://thechinaproject.com/2022/09/29/chinese-parents-increasingly-trust-and-buy-local-infant-formula-brands/ (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Cao, Y. Investigating Consumer Behavior in China during the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Creative Industry and Knowledge Economy (CIKE 2022), Online, 25–27 March 2022; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.C. The Surge of Nationalist Sentiment among Chinese Youth during the COVID-19 Pandemic. China Int. J. 2022, 20, 4. Available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/871868 (accessed on 26 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Costa-Font, M.; Gil, J.M.; Traill, W.B. Consumer acceptance, valuation of and attitudes towards genetically modified food: Review and implications for food policy. Food Policy 2008, 33, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, V.A.M.; Teixeira, R.; Ladeira, W.J.; de Oliveira Santini, F. A meta-analytic review of food safety risk perception. Food Control 2020, 112, 107089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, E.; Houghton, J.R.; Krystallis, A.; Pfenning, U.; Rowe, G.; Van Dijk, H.; Van der Lans, I.A.; Frewer, L.J. Consumer evaluations of food risk management quality in Europe. Risk Anal. 2007, 27, 1565–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, M.; Freeman, B. A baby formula designed for Chinese babies: Content analysis of milk formula advertisements on Chinese parenting apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e14219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Feng, G.; Liu, H.; Peng, H.; Dong, X. Sustainable market? The impact of downstream market concentration on high-quality agricultural development: Evidence from China’s dairy industry. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1453115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Socio-Demographic Information | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 41.9 |

| Female | 58.1 | |

| Age (years) | 20–30 | 36.9 |

| 30–40 | 57.4 | |

| 40–50 | 5.0 | |

| Over 50 | 0.7 | |

| Education | Junior high school or lower | 1.1 |

| Senior high school (Inc vocational education) | 10.8 | |

| College (2–3 years) | 22.9 | |

| Bachelor’s degree (University) | 53.6 | |

| Postgraduate and beyond | 11.6 | |

| Family size | 2 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 40.7 | |

| 4 | 30.6 | |

| 5 | 17.9 | |

| 6 and more | 10.3 | |

| Income (CNY) | ≤100,000 | 10.7 |

| 100,000–200,000 | 47.1 | |

| 200,000–300,000 | 26.1 | |

| 300,000–400,000 | 10.1 | |

| >400,000 | 6.0 |

| Latent Variables | Cronbach’s α | Manifest Variables | Item Wording | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase intention (PI) | 0.899 | PI1 | I am willing to pay for domestically produced IMF, even if the price is slightly higher | 4.85 | 1.4532 |

| PI2 | I will recommend domestic IMF to my relatives and friends | 5.21 | 1.4009 | ||

| PI3 | I will continue to buy domestic IMF even after the epidemic is over | 5.31 | 1.4484 | ||

| Perceived product quality (PPQ) | 0.733 | PPQ1 | The raw materials used in the production of domestic IMF are reliable | 4.17 | 1.5007 |

| PPQ2 | The manufacturing technology utilized for domestic IMF production has achieved a world-class standard | 5.01 | 1.4379 | ||

| PPQ3 | The formula standards established by Chinese regulatory authorities are better tailored to the needs of Chinese infants | 5.42 | 1.3199 | ||

| Perceived behaviour control (PBC) | 0.665 | PBC1 | Most of my relatives and friends are using domestic IMF for their infants | 4.49 | 1.6275 |

| PBC2 | My knowledge regarding domestic brands and their attributes surpasses my knowledge of imported brands | 4.90 | 1.6122 | ||

| PBC3 | I possess greater proficiency in handling post-purchase matters related to domestic IMF | 4.86 | 1.5088 | ||

| Food safety governance (FSG) | 0.796 | FSG1 | I trust the enforcement efforts of regulatory agencies | 5.45 | 1.2832 |

| FSG2 | The pass rate of sampling inspection of IMF is the highest in the food sector (was 99.9% in 2021) | 4.83 | 1.4748 | ||

| FSG3 | China’s supervision of IMF quality and safety is “most rigorous in history” | 4.89 | 1.5684 | ||

| Trust of stakeholders (TS) | 0.822 | TS1 | I have trust in dairy farmers’ practices | 5.04 | 1.3546 |

| TS2 | I trust IMF manufacturers | 4.94 | 1.3227 | ||

| TS3 | I trust IMF distributors | 4.72 | 1.3316 | ||

| Consumer Ethnocentrism (CE) | 0.759 | CE1 | Purchasing domestically manufactured can contribute to the revitalization of China’s dairy industry | 5.31 | 1.3494 |

| CE2 | Purchasing imported IMF may negatively impact Chinese businesses and employment | 4.61 | 1.4615 | ||

| CE3 | Purchasing domestic IMF can support the stimulation of “internal circulation” in Chinese economy | 5.39 | 1.3483 | ||

| COVID-19 Impact (CI) | 0.744 | CI1 | I would have concerns about the possibility of imported IMF carrying the coronavirus | 5.19 | 1.5955 |

| CI2 | I would be worried that cross-border logistics could not ensure a consistent supply of imported IMF | 5.54 | 1.1973 | ||

| CI3 | My perception of how foreign governments handled the pandemic could influence my trust in imported IMF | 5.24 | 1.5039 | ||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.933 | ||||

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 6237.18 | |||

| df | 190 | ||||

| Sig. | <0.001 | ||||

| Category | Index | Value | Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute fit | Chisq/df | 3.183 | ChiSq/df < 5.0 |

| SRMR | 0.049 | SRMR < 0.08 | |

| RMSEA | 0.062 | RMSEA < 0.08 | |

| Incremental fit | GFI | 0.914 | GFI > 0.90 |

| AGFI | 0.883 * | AGFI > 0.90 | |

| CFI | 0.942 | CFI > 0.90 | |

| TLI | 0.928 | TLI > 0.90 | |

| IFI | 0.943 | IFI > 0.90 | |

| NFI | 0.919 | NFI > 0.90 | |

| Parsimonious fit | PGFI | 0.669 | PGFI > 0.50 |

| PNFI | 0.739 | PNFI > 0.50 |

| Parameter | Std Estimates | Bootstrap 95% CI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile | Bias-Corrected | ||||||||||

| Lower | Upper | p | Lower | Upper | p | ||||||

| Direct effect | |||||||||||

| From | To | ||||||||||

| FSG | ---> | PI | −0.249 | −1.370 | −0.005 | 0.094 | −0.832 | 0.082 | 0.223 | ||

| TS | ---> | PI | 0.098 | −0.053 | 0.253 | 0.226 | −0.072 | 0.247 | 0.289 | ||

| CE | ---> | PI | −0.109 | −0.819 | 0.091 | 0.298 | −0.524 | 0.193 | 0.686 | ||

| CI | ---> | PI | 0.111 | −0.038 | 0.188 | 0.191 | 0.013 | 0.213 | 0.082 | ||

| Indirect effect | |||||||||||

| From | Pass | To | |||||||||

| FSG | ---> | PPQ | ---> | PI | 0.332 | 0.100 | 1.282 | 0.010 | 0.083 | 0.899 | 0.020 |

| FSG | ---> | PBC | ---> | PI | 0.101 | 0.006 | 0.210 | 0.084 | 0.012 | 0.227 | 0.071 |

| TS | ---> | PPQ | ---> | PI | 0.001 | −0.158 | 0.082 | 0.955 | −0.165 | 0.078 | 0.955 |

| TS | ---> | PBC | ---> | PI | 0.054 | −0.036 | 0.203 | 0.265 | −0.029 | 0.204 | 0.234 |

| CE | ---> | PPQ | ---> | PI | 0.183 | 0.103 | 0.971 | 0.010 | 0.066 | 0.508 | 0.036 |

| CE | ---> | PBC | ---> | PI | 0.442 | 0.361 | 1.247 | 0.010 | 0.325 | 1.143 | 0.018 |

| CI | ---> | PPQ | ---> | PI | 0.054 | 0.013 | 0.210 | 0.019 | 0.012 | 0.184 | 0.022 |

| CI | ---> | PBC | ---> | PI | 0.019 | −0.056 | 0.109 | 0.633 | −0.050 | 0.116 | 0.547 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Waldron, S.; Dong, X.; Dai, X. Mediating Roles of Perceived Quality and Perceived Behaviour Control in Shaping Chinese Consumer’s Purchase Intention for Domestic Infant Milk Formula (IMF). Foods 2024, 13, 3099. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13193099

Zhang J, Waldron S, Dong X, Dai X. Mediating Roles of Perceived Quality and Perceived Behaviour Control in Shaping Chinese Consumer’s Purchase Intention for Domestic Infant Milk Formula (IMF). Foods. 2024; 13(19):3099. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13193099

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jing, Scott Waldron, Xiaoxia Dong, and Xin Dai. 2024. "Mediating Roles of Perceived Quality and Perceived Behaviour Control in Shaping Chinese Consumer’s Purchase Intention for Domestic Infant Milk Formula (IMF)" Foods 13, no. 19: 3099. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13193099

APA StyleZhang, J., Waldron, S., Dong, X., & Dai, X. (2024). Mediating Roles of Perceived Quality and Perceived Behaviour Control in Shaping Chinese Consumer’s Purchase Intention for Domestic Infant Milk Formula (IMF). Foods, 13(19), 3099. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13193099