The Time Is Ripe: Thinking about the Future Reduces Unhealthy Eating in Those with a Higher BMI

Abstract

1. Introduction

Pilot Study

2. Materials and Methods

- a)

- Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI; [8]). Specifically, they completed the subscales of Present-Hedonistic (α = 0.77, e.g., “I take risks to put excitement in my life.”), Present Fatalistic (α = 0.80, e.g., “My life path is controlled by forces I cannot influence.”), and Future (α = 0.73, e.g., “I make lists of things to do.”).

- b)

- Consideration of Future Consequences Scales [6]: Immediate subscale (α = 0.79, e.g., “I only act to satisfy immediate concerns, figuring the future will take care of itself.”), and Future subscale (α = 0.84, e.g., “I consider how things might be in the future, and try to influence those things with my day to day behavior.”).

- c)

- Future Self-Continuity Scale [31]. This scale measures how similar people perceive their current self will be to their self 10 years in the future. Participants are presented with circle pairs with varying degrees of overlap, with one circle in each pair representing their current self, and the other circle representing their future self. Participants are asked to choose which circle pair best describes how similar and how connected they feel to their future self 10 years from now.

2.1. Experiment 1

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Design

2.1.3. Measures

- a)

- Consideration of Future Consequences Scales [6]. We used the validated French translation of this scale [33], which included the CFC-Immediate subscale (e.g., “I only act to satisfy immediate concerns, figuring the future will take care of itself”; α = 0.85), and the CFC-Future subscale (e.g., “I think it is more important to perform a behavior with important distant consequences than a behavior with less important immediate consequences”). Because the reliability of the full CFC-Future subscale was low (α = 0.50), we removed the least reliable question (“I am willing to sacrifice the immediate happiness or well-being in order to achieve future outcomes”), in order to increase the reliability of the subscale (α = 0.86). The scale ranged from 1 = does not correspond at all to me to 7 = corresponds completely with me. An overall CFC score was calculated by subtracting the CFC-Immediate subscale from the CFC-Future subscale. Thus, higher scores indicated a stronger future orientation.

- b)

- Mood was assessed with the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; [34]), consisting of two 10-item scales assessing the extent to which participants feel positive (α = 0.84) and negative affect (α = 0.81). Responses ranged from 1 = Not at all to 5 = Extremely.

- c)

- Participants’ levels of restrained eating was assessed with the restrained eating subscale of the DEBQ [32]. This subscale consists of five items such as “Do you watch exactly what you eat?” (α = 0.76). Responses ranged from 1 = Never to 5 = Very often.

- d)

- Hunger levels were assessed with two items that were embedded in the PANAS, which asked participants to what extent they felt satiated and to what extent they felt hungry (α = 0.67). Responses ranged from 1 = Not at all to 5 = Extremely.

- e)

- Participants’ BMI was calculated using measures of height (m) and weight (kg) taken by the researchers.

2.1.4. Procedure

2.2. Experiment 2

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Design and Procedure

2.2.3. Measures

2.2.4. Stop-Signal Task

3. Results

3.1. Pilot Study

3.2. Experiment 1

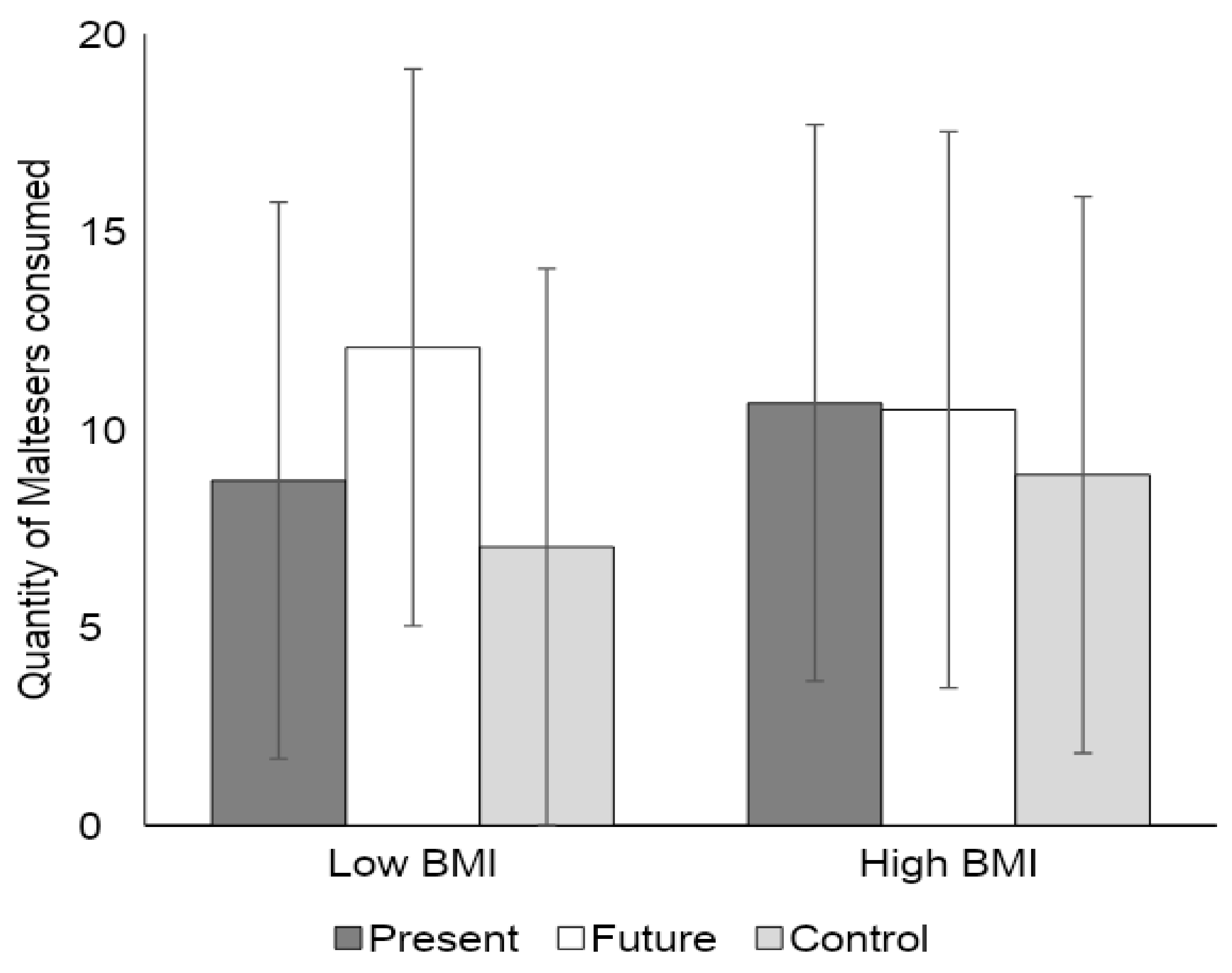

3.2.1. Malteser Consumption

3.2.2. Muesli Consumption

3.3. Experiment 2

3.3.1. Malteser Consumption

3.3.2. Muesli Consumption

3.3.3. Mediation by Impulsivity

3.3.4. Delay Discounting

3.3.5. Stop-Signal Task

4. Discussion

4.1. Experiment 1

4.2. Experiment 2

4.3. General Discussion

4.4. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, F.B. Dietary pattern analysis: A new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2002, 13, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbaraly, T.; Brunner, E.J.; Ferrie, J.E.; Marmot, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Singh-Manoux, A. Dietary pattern and depressive symptoms in middle age. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacka, F.N.; Mykletun, A.; Berk, M.; Bjelland, I.; Tell, G.S. The Association Between Habitual Diet Quality and the Common Mental Disorders in Community-Dwelling Adults. Psychosom. Med. 2011, 73, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J. Consideration of immediate and future consequences, smoking status, and body mass index. Health Psychol. 2012, 31, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, E. The Influence of Time Preferences on the Development of Obesity: Evidence from a General Population Longitudinal Survey. Available online: https://www.ces-asso.org/sites/default/files/E%20Gray%20Time%20Preference%20and%20Obesity%20CESHESG.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Strathman, A.; Gleicher, F.; Boninger, D.S.; Edwards, C.S. The consideration of future consequences: Weighing immediate and distant outcomes of behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beek, J.; Antonides, G.; Handgraaf, M.J. Eat now, exercise later: The relation between consideration of immediate and future consequences and healthy behavior. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2013, 54, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P.G.; Boyd, J.N. Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 1271–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipp, A.J.; Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Conceptualization and measurement of temporal focus: The subjective experience of the past, present, and future. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 110, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, S.; Loewenstein, G.; O’Donoghue, T. Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. J. Econ. Lit. 2002, 40, 351–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, J.R.; Brase, G.L. Taking time to be healthy: Predicting health behaviors with delay discounting and time perspective. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joireman, J.; Balliet, D.; Sprott, D.; Spangenberg, E.; Schultz, J. Consideration of future consequences, ego-depletion, and self-control: Support for distinguishing between CFC-Immediate and CFC-Future sub-scales. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2008, 45, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuscher, U.; Mitchell, S.H. Relation Between Time Perspective and Delay Discounting: A Literature Review. Psychol. Rec. 2011, 61, 613–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; Nettle, D. Time perspective, personality and smoking, body mass, and physical activity: An empirical study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griva, F.; Tseferidi, S.-I.; Anagnostopoulos, F. Time to get healthy: Associations of time perspective with perceived health status and health behaviors. Psychol. Health Med. 2014, 20, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthrie, L.C.; Butler, S.C.; Ward, M.M. Time perspective and socioeconomic status: A link to socioeconomic disparities in health? Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 2145–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amlung, M.; Petker, T.; Jackson, J.; Balodis, I.; MacKillop, J. Steep discounting of delayed monetary and food rewards in obesity: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 2423–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojek, M.M.; MacKillop, J. Relative reinforcing value of food and delayed reward discounting in obesity and disordered eating: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 55, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, A.M.; Culcea, I. Does a future-oriented temporal perspective relate to body mass index, eating, and exercise? A meta-analysis. Appetite 2017, 112, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, V.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D. Why do women of low socioeconomic status have poorer dietary behaviours than women of higher socioeconomic status? A qualitative exploration. Appetite 2005, 45, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; White, M. Time perspective in socioeconomic inequalities in smoking and body mass index. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Afshin, A.; Singh, G.; Mozaffarian, D. Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e004277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dassen, F.C.; Jansen, A.; Nederkoorn, C.; Houben, K. Focus on the future: Episodic future thinking reduces discount rate and snacking. Appetite 2016, 96, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Pham, M.T. Affect as a Decision-Making System of the Present. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.; Aron, E.N.; Smollan, D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershfield, H.E.; Cohen, T.R.; Thompson, L. Short horizons and tempting situations: Lack of continuity to our future selves leads to unethical decision making and behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2012, 117, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murru, E.C.; Ginis, K.A.M. Imagining the possibilities: The effects of a possible selves intervention on self-regulatory efficacy and exercise behavior. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2010, 32, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornil, Y.; Chandon, P. Pleasure as a Substitute for Size: How Multisensory Imagery Can Make People Happier with Smaller Food Portions. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 53, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papies, E.K.; Barsalou, L.W.; Custers, R. Mindful Attention Prevents Mindless Impulses. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2011, 3, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papies, E.K.; Pronk, T.; Keesman, M.; Barsalou, L.W. The benefits of simply observing: Mindful attention modulates the link between motivation and behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 108, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersner-Hershfield, H.; Garton, M.T.; Ballard, K.; Samanez-Larkin, G.R.; Knutson, B. Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow: Individual differences in future self-continuity account for saving. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2009, 4, 280–286. [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.R.; van Staveren, W.A.; Defares, P.B.; Deurenberg, P. The predictive validity of the Dutch Restrained Eating Scale. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus, G.; Berjot, S.; Ernst-Vintila, A. Validation française de l’échelle de prise en considération des conséquences futures de nos actes (CFC-14). Revue Internationale Psychologie Sociale 2014, 27, 35–63. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, K.N.; Petry, N.M.; Bickel, W.K. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1999, 128, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrickson, K.L.; Rasmussen, E.B.; Lawyer, S.R. Measurement and validation of measures for impulsive food choice across obese and healthy-weight individuals. Appetite 2015, 90, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, G.D.; Schachar, R.; Tannock, R. Impulsivity and Inhibitory Control. Psychol. Sci. 1997, 8, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, B.A.; Reed, D.D.; McKerchar, T.L. Using a Visual Analogue Scale to Assess Delay, Social, and Probability Discounting of an Environmental Loss. Psychol. Rec. 2014, 64, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, K.N.; Petry, N.M. Heroin and cocaine abusers have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than alcoholics or non-drug-using controls. Addiction 2004, 99, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreves, P.A.; Blackhart, G.C. Thinking into the future: How a future time perspective improves self-control. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 149, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Baumeister, R.F. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, T.H.; Crandall, A.K.; Temple, J.L. The effect of repeated episodic future thinking on the relative reinforcing value of snack food. J. Health Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, L.H.; Salvy, S.; Carr, K.A.; Dearing, K.K.; Bickel, W.K. Food reinforcement, delay discounting and obesity. Physiol. Behav. 2010, 100, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollins, B.Y.; Dearing, K.K.; Epstein, L.H. Delay discounting moderates the effect of food reinforcement on energy intake among non-obese women. Appetite 2010, 55, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimers, S.; Maylor, E.A.; Stewart, N.; Chater, N. Associations between a one-shot delay discounting measure and age, income, education and real-world impulsive behavior. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, J.N.; Kwan, D.; Green, L.; Myerson, J.; Craver, C.F.; Rosenbaum, R.S. Is it time? Episodic imagining and the discounting of delayed and probabilistic rewards in young and older adults. Cognition 2020, 199, 104222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, H.; Scheres, A.; de Water, E.; Graf, U.; Granic, I.; Luijten, M. Behavioral trainings and manipulations to reduce delay discounting: A systematic review. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2019, 26, 1803–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.; Panetta, G.; Leung, C.-M.; Wong, G.G.; Wang, C.K.J.; Chan, D.K.C.; Keatley, D.A.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. Chronic Inhibition, Self-Control and Eating Behavior: Test of a ‘Resource Depletion’ Model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laran, J. Choosing Your Future: Temporal Distance and the Balance between Self-Control and Indulgence. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, C.; Voss, A.; Schmitz, F.; Nuszbaum, M.; Tüscher, O.; Lieb, K.; Klauer, K.C. Behavioral components of impulsivity. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2014, 143, 850–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, R.L.; Levine, M.D. Questionnaire and behavioral task measures of impulsivity are differentially associated with body mass index: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 868–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia, M.S.; Palma, M.A.; Nayga, R.M. Can episodic future thinking affect food choices? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2020, 177, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, P.A.; Fong, G.T. The effects of a brief time perspective intervention for increasing physical activity among young adults. Psychol. Health 2003, 18, 685–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall Mean (n = 65) | Present (n = 23) | Future (n = 21) | Control (n = 21) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect | 3.16 (0.65) | 3.16 (0.69) | 3.22 (0.64) | 3.10 (0.62) |

| Negative Affect | 1.47 (0.48) | 1.65 (0.59) | 1.22 (0.21) | 1.52 (0.47) |

| Hunger | 3.74 (1.15) | 3.83 (1.21) | 3.71 (1.02) | 3.67 (1.26) |

| CFC-Immediate | 3.45 (1.25) | 3.94 (1.36) | 3.12 (1.22) | 3.24 (1.01) |

| CFC-Future | 4.82 (1.23) | 4.53 (1.29) | 5.18 (1.02) | 4.77 (1.30) |

| CFC-Mean | 1.37 (2.14) | 0.59 (2.10) | 2.07 (2.10) | 1.52 (2.04) |

| Restrained Eating | 2.42 (0.88) | 2.35 (0.76) | 2.28 (0.94) | 2.66 (0.93) |

| BMI | 21.95 (3.03) | 22.03 (3.27) | 21.51 (3.03) | 22.29 (2.86) |

| Quantity of Maltesers eaten (in grams) | 10.05 (9.03) | 9.30 (8.39) | 12.38(10.67) | 8.52 (7.85) |

| Quantity of muesli eaten (in grams) | 5.52 (7.64) | 3.59 (2.75) | 7.05 (6.58) | 6.12 (11.31) |

| Maltesers B | Muesli B | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | BMI | 0.12 (0.37, 0.38) | 0.01 (0.28, 0.31) |

| Restraint | −0.05 (−0.54, 1.34) | −0.1–0.17 (−1.46, 1.10) | |

| CFC | 0.26 (1.11, 0.55) * | 0.35 (1.25, 0.45) ** | |

| Time vs. Control | 0.13 (0.85, 0.80) | −0.06 (−0.30, 0.65) | |

| Future vs. Present | 0.07 (0.80, 1.40) | 0.09 (0.83, 1.15) | |

| F | 1.45 | 2.38 * | |

| R2 | 0.11 | 0.06 | |

| Step 2 | BMI | 0.15 (0.44, 0.35) | 0.17 (0.44, 0.31) |

| Restraint | −0.10 (−1.03, 1.23) | −0.20 (−1.77, 1.06) | |

| CFC | 0.26 (1.10, 0.49) * | 0.31 (1.11, 0.42) | |

| Time vs. Control | 0.03 (0.17, 0.72) | −0.14 (−0.73, 0.62) | |

| Future vs. Present | 0.10 (1.06, 1.26) | 0.15 (1.41, 1.09) | |

| BMI × Time vs. Control | −0.12 (−0.27, 0.28) | −0.22 (−0.42, 0.24) | |

| BMI × Future vs. Present | −0.25 (−0.88, 0.39) * | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.33) | |

| Restraint × Time vs. Control | 0.30 (2.16, 0.89) * | 0.42 (2.57, 0.77) ** | |

| Restrained × Future vs. Present | 0.22 (2.79, 1.46) + | 0.07 (0.75, 1.26) | |

| CFC × Time vs. Control | 0.01 (0.04, 0.36) | −0.14 (−0.36, 0.31) | |

| CFC × Future vs. Present | 0.27 (1.39, 0.59) * | 0.15 (0.65, 0.50) | |

| F | 3.15 ** | 2.84 ** | |

| R2 | 0.40 | 0.37 |

| Overall Mean (N = 136) | Present (n = 51) | Future (n = 45) | Control (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect | 3.01 (0.64) | 3.08 (0.72) | 2.99 (0.56) | 2.93 (0.61) |

| Negative Affect | 1.40 (0.41) | 1.47 (0.46) | 1.39 (0.41) | 1.34 (0.34) |

| Hunger | 1.91 (1.16) | 2.04 (1.15) | 1.73 (1.21) | 1.95 (1.13) |

| CFC-Immediate | 3.50 (1.23) | 3.57 (1.07) | 3.43 (1.43) | 3.50 (1.19) |

| CFC-Future | 4.77 (1.06) | 4.96 (0.99) | 4.56 (1.23) | 4.75 (0.93) |

| CFC-Mean | 1.26 (1.93) | 1.39 (1.76) | 1.18 (2.21) | 1.26 (1.83) |

| Restrained Eating | 2.68 (0.94) | 2.80 (0.95) | 2.48 (0.99) | 2.77 (0.86) |

| BMI | 22.65 (4.36) | 23.51 (4.75) | 22.27 (3.96) | 22.04 (4.08) |

| Quantity of Maltesers eaten (in grams) | 5.98 (4.28) | 6.43 (4.75) | 6.07 (4.72) | 5.30 (3.78) |

| Quantity of muesli eaten (in grams) | 3.15 (2.52) | 3.39 (2.59) | 3.27 (2.59) | 2.70 (2.36) |

| Budget | 289.63 (384.76) | 341.57 (536.62) | 226.05 (232.83) | 291.75 (263.25) |

| Stop-Signal RT (ms) | 101.70 (1586.46) | 218.75(150.89) | 257.70 (148.05) | −223.77 (290.30) |

| Stop-Signal ACC | 0.68 (0.15) | 0.66(0.17) | 0.67 (0.12) | 0.71 (0.15) |

| Money discounting | 0.038 (0.050) | 0.039 (0.056) | 0.032 (0.037) | 0.044 (0.055) |

| Food discounting | 0.231 (0.190) | 0.220 (0.187) | 0.254 (0.204) | 0.218 (0.182) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Malteser consumption | ||||||||

| 2. Muesli consumption | 0.370 ** | |||||||

| 3. Money discounting | 0.079 | 0.128 | ||||||

| 4. Food discounting | 0.066 | 0.080 | 0.135 | |||||

| 5. Stop-Signal RT | 0.011 | −0.011 | −0.037 | −0.103 | ||||

| 6. Stop-Signal ACC | −0.121 | −0.187 * | −0.134 | 0.103 | −0.037 | |||

| 7. BMI | 0.094 | 0.118 | 0.126 | −0.046 | 0.051 | −0.076 | ||

| 8. CFC | 0.024 | 0.010 | −0.127 | −0.054 | 0.156 | −0.086 | 0.121 | |

| 9. Restraint | 0.005 | 0.055 | 0.054 | −0.178 * | −0.040 | 0.021 | 0.250 * | 0.216 * |

| Maltesers B | Muesli B | Stop-Signal Task RT B | Stop-Signal Task ACC B | Money Discounting | Food Discounting | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | BMI | 0.08 (0.08, 0.09) | 0.10 (0.06, 0.05) | 0.04 (13.55, 33.40) | −0.06 (−0.00, 0.00) | 0.12 (0.04, 0.02) * | <0.001 (<0.001, 0.01) |

| Restraint | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.42) | 0.04 (0.11, 0.25) | −0.07 (−116.72, 157.65) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.02) | 0.04 (0.06, 0.09) | −0.13 (−0.16, 0.07) * | |

| CFC | 0.02 (0.04, 0.20) | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.12) | 0.16 (130.45, 74.31) | −0.08 (−0.01, 0.01) | −0.14 (−0.11, 0.04) ** | −0.008 (−0.005, 0.03) | |

| Time vs. Control | 0.09 (0.29, 0.27) | 0.108 (0.198, 0.16) | 0.12 (138.79, 104.79) | −0.13 (−0.014, 0.01) | −0.08 (−0.09, 0.06) | 0.03 (0.03, 0.04) | |

| Future vs. Present | −0.027 (0.289, 0.27) | −0.004 (−0.012, 0.26) | 0.02 (32.72, 170.07) | 0.00 (0.01, 0.02) | 0.05 (0.09, 0.09) | −0.04 (−0.06, 0.07) | |

| F | 0.50 | 0.70 | 1.14 | 0.75 | 3.30 ** | 1.69 | |

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | |

| Step 2 | BMI | 0.03 (0.03, 0.093) | 0.12 (0.07, 0.06) | 0.05 (17.76, 33.67) | −0.03 (−0.00, 0.02) | 0.10 (0.04, 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.003, 0.01) |

| Restraint | −0.00(−0.01, 0.44) | 0.05 (0.12, 0.26) | −0.15 (−251.03, 160.47) | 0.07 (0.012, 0.02) | 0.03 (0.05, 0.09) | −0.11 (−0.14, 0.07) | |

| CFC | 0.01 (0.03, 0.21) | 0.01 (0.01,0.12) | 0.26 (208.58, 76.81) | −0.09 (−0.01, 0.01) | −0.13 (−0.10, 0.04) | <0.001 (<0.001, 0.03) | |

| Time vs. Control | 0.08 (0.26, 0.28) | 0.11 (0.20, 0.16) | 0.09 (101.67, 102.78) | −0.11 (−0.01, 0.01) | −0.10 (−0.12, 0.06) | 0.05 (0.04, 0.04) | |

| Future vs. Present | −0.03 (−0.16, 0.45) | −0.01 (−0.02 ,0.27) | 0.01 (14.66, 165.41) | 0.02 (.04, 0.02) | 0.06 (0.12, 0.09) | −0.05 (−0.07, 0.07) | |

| BMI × Time vs. Control | 0.07 (0.05, 0.07) | −0.04 (−0.018, 0.04) | −0.08 (−21.84, 25.08) | −0.01 (0.00, 0.00) | −0.05 (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.14 (0.03, 0.01) ** | |

| BMI × Future vs. Present | −0.18 (−0.21, 0.11) * | 0.13 (0.09, 0.06) | 0.01 (2.53, 38.90) | 0.17 (0.01, 0.00) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.02) | −0.08 (−0.03, 0.02) | |

| Restraint × Time vs. Control | −0.06 (−0.21, 0.34) | 0.02 (0.04,0.20) | 0.18 (225.55, 125.04) | −0.07 (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.002 (0.002, 0.07) | −0.05 (−0.04, 0.05) | |

| Restrained × Future vs. Present | −0.12 (−0.65, 0.47) | 0.020 (0.06, 0.28) | 0.011 (20.51, 174.21) | −0.08 (−0.01, 0.02) | 0.11 (0.21, 0.09) * | 0.04 (0.06, 0.08) | |

| CFC × Time vs. Control | −0.05 (−0.09, 0.16) | 0.050 (0.05, 0.09) | −0.34 (−209.06, −59.22) ** | 0.16 (0.01, 0.01) | −0.02 (−0.01, 0.03) | 0.008 (0.004, 0.03) | |

| CFC × Future vs. Present | 0.01 (0.02, 0.23) | −0.121 (−0.18, 0.14) | −0.01 (−6.96, 84.73) | −0.04 (−0.00, 0.01) | 0.04 (0.04, 0.05) | −0.002 (−0.001, 0.04) | |

| F | 1.05 | 0.68 | 1.86 * | 0.86 | 2.45 ** | 1.56 | |

| R2 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, B.P.I.; Claassen, M.A.; Klein, O. The Time Is Ripe: Thinking about the Future Reduces Unhealthy Eating in Those with a Higher BMI. Foods 2020, 9, 1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9101391

Chang BPI, Claassen MA, Klein O. The Time Is Ripe: Thinking about the Future Reduces Unhealthy Eating in Those with a Higher BMI. Foods. 2020; 9(10):1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9101391

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Betty P. I., Maria Almudena Claassen, and Olivier Klein. 2020. "The Time Is Ripe: Thinking about the Future Reduces Unhealthy Eating in Those with a Higher BMI" Foods 9, no. 10: 1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9101391

APA StyleChang, B. P. I., Claassen, M. A., & Klein, O. (2020). The Time Is Ripe: Thinking about the Future Reduces Unhealthy Eating in Those with a Higher BMI. Foods, 9(10), 1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9101391