Skull Impact on Photoacoustic Imaging of Multi-Layered Brain Tissues with Embedded Blood Vessel Under Different Optical Source Types: Modeling and Simulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

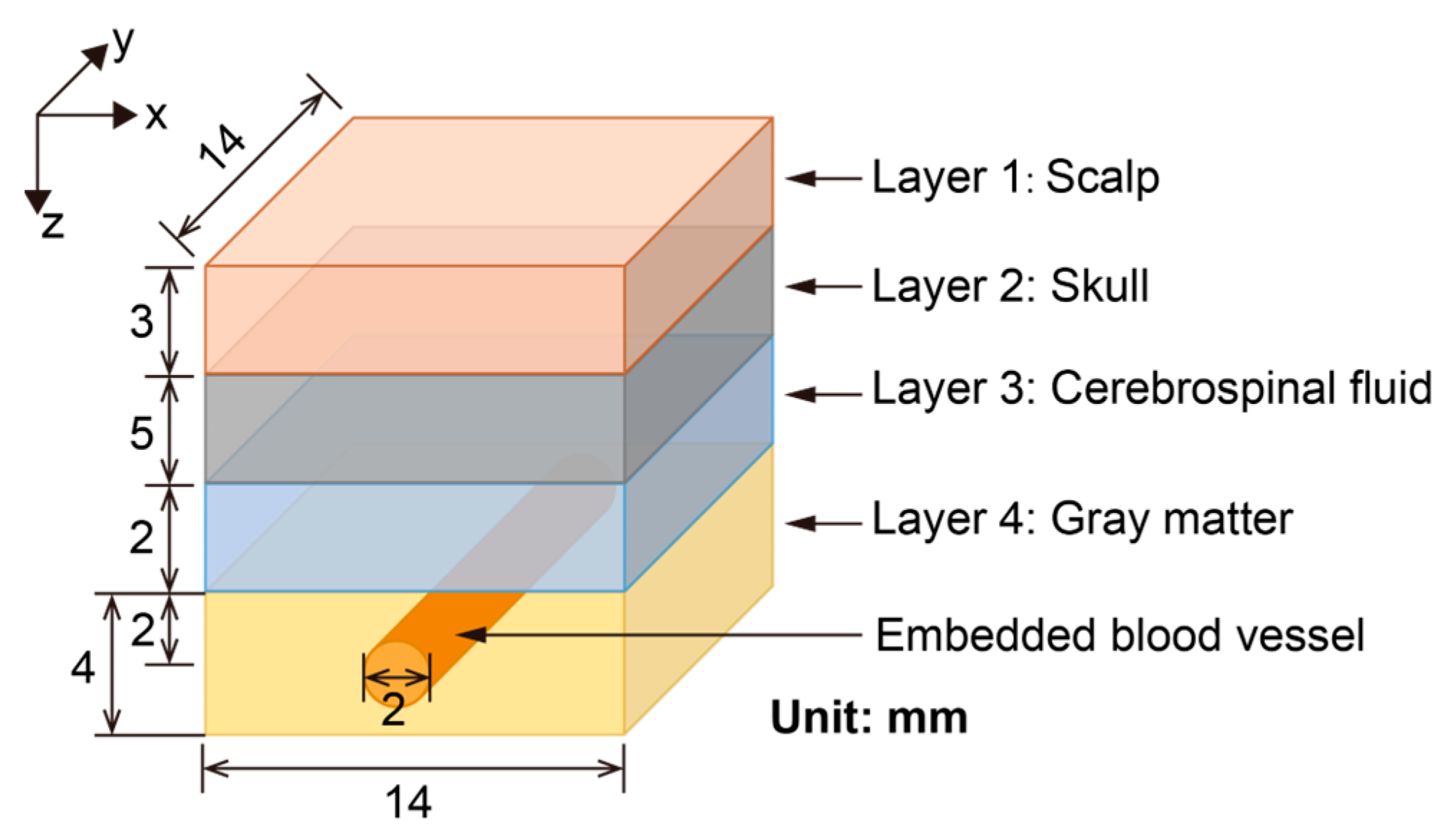

2.1. Brain Model

2.2. Various Types of Optical Sources

2.3. Optical Simulation

2.4. Acoustic Simulation

2.5. Image Reconstruction

2.6. Image Evaluation

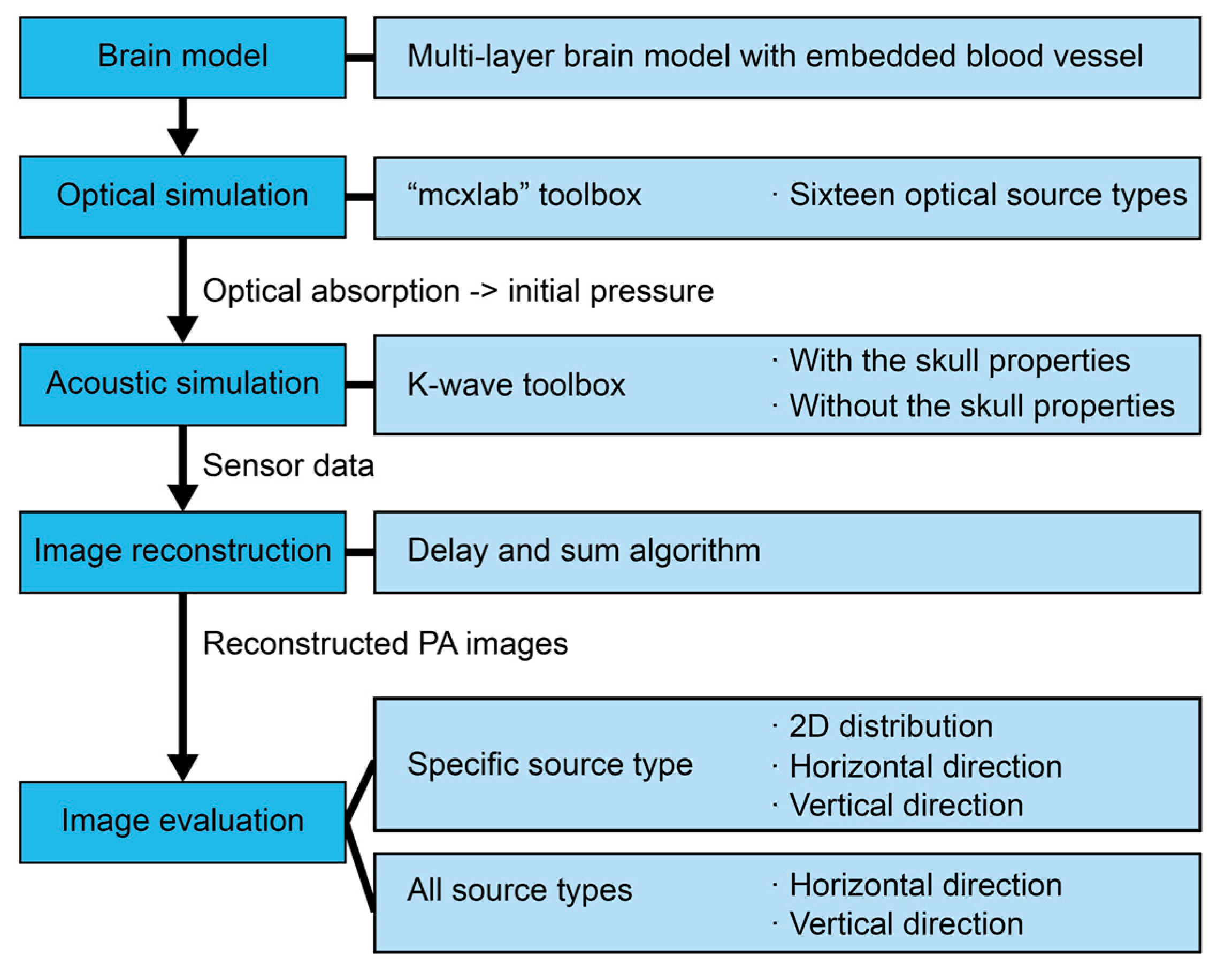

2.7. Overview of Method

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Distribution of 2D Images

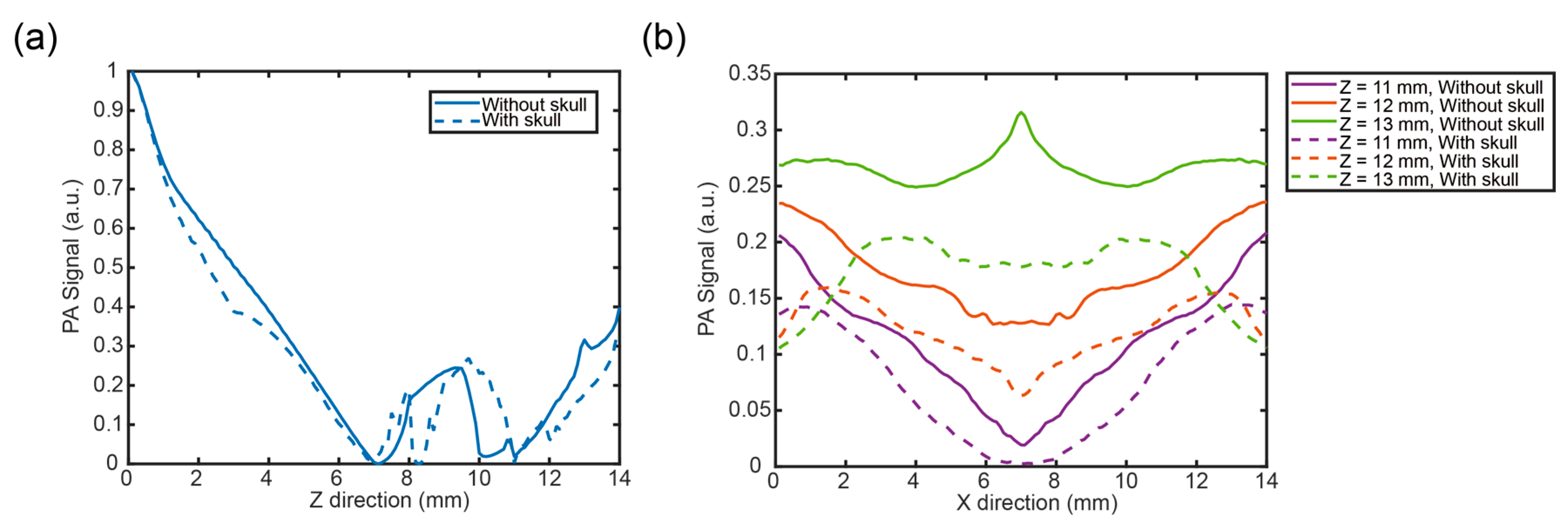

3.2. Analysis in Two Directions Under Specific Illumination of Pencil Beam

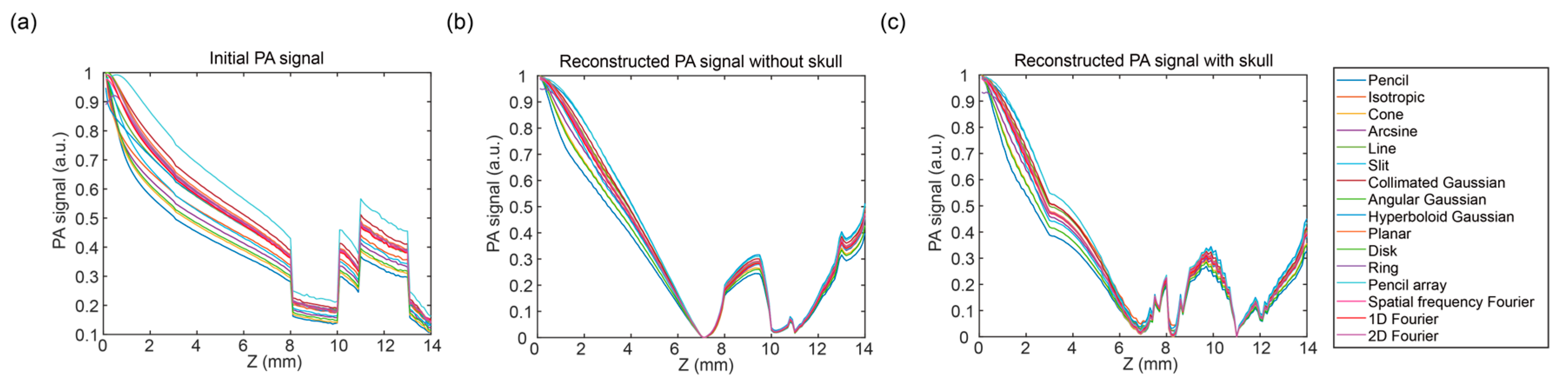

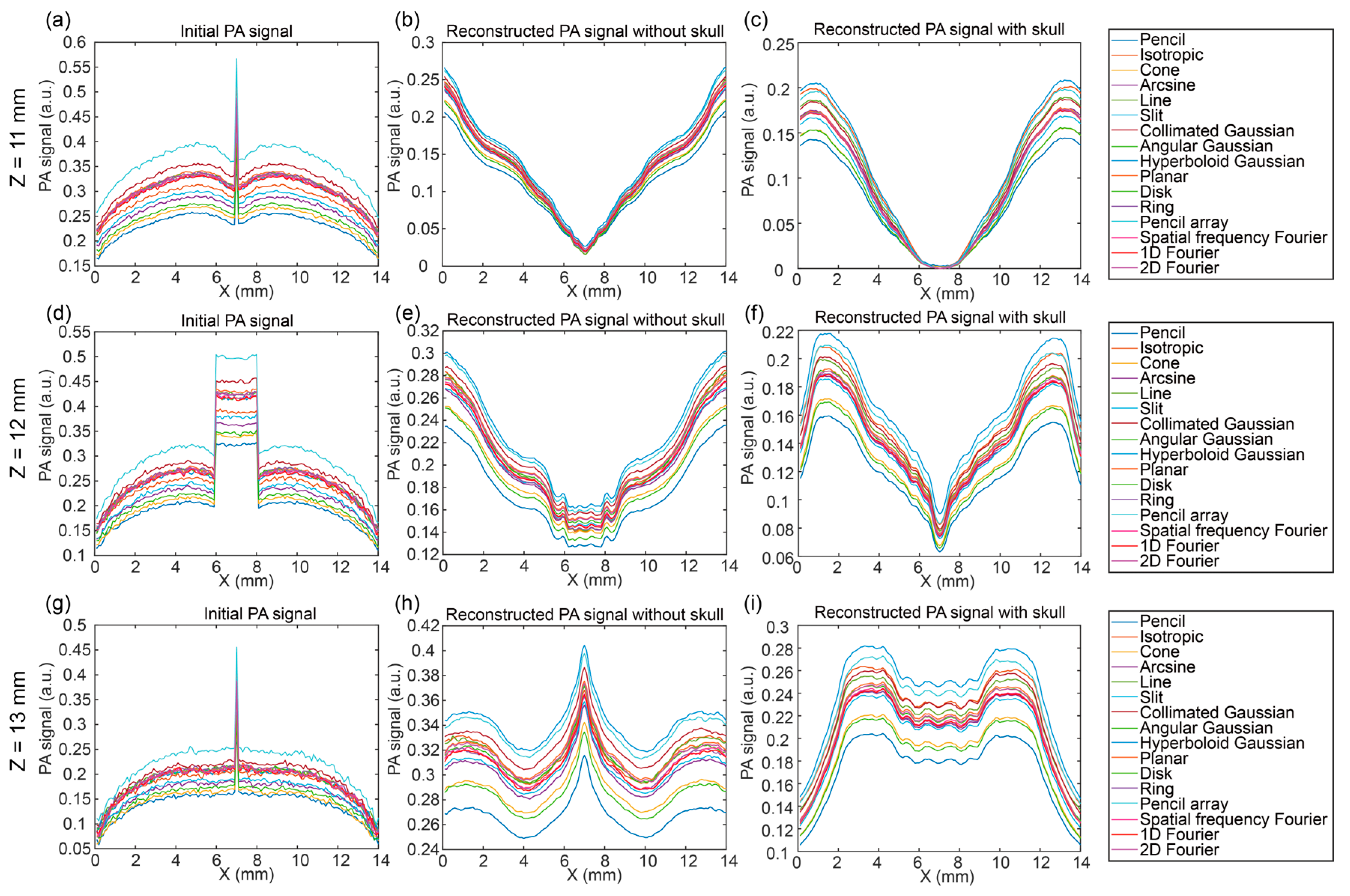

3.3. Photoacoustic Signal Distribution in Two Directions

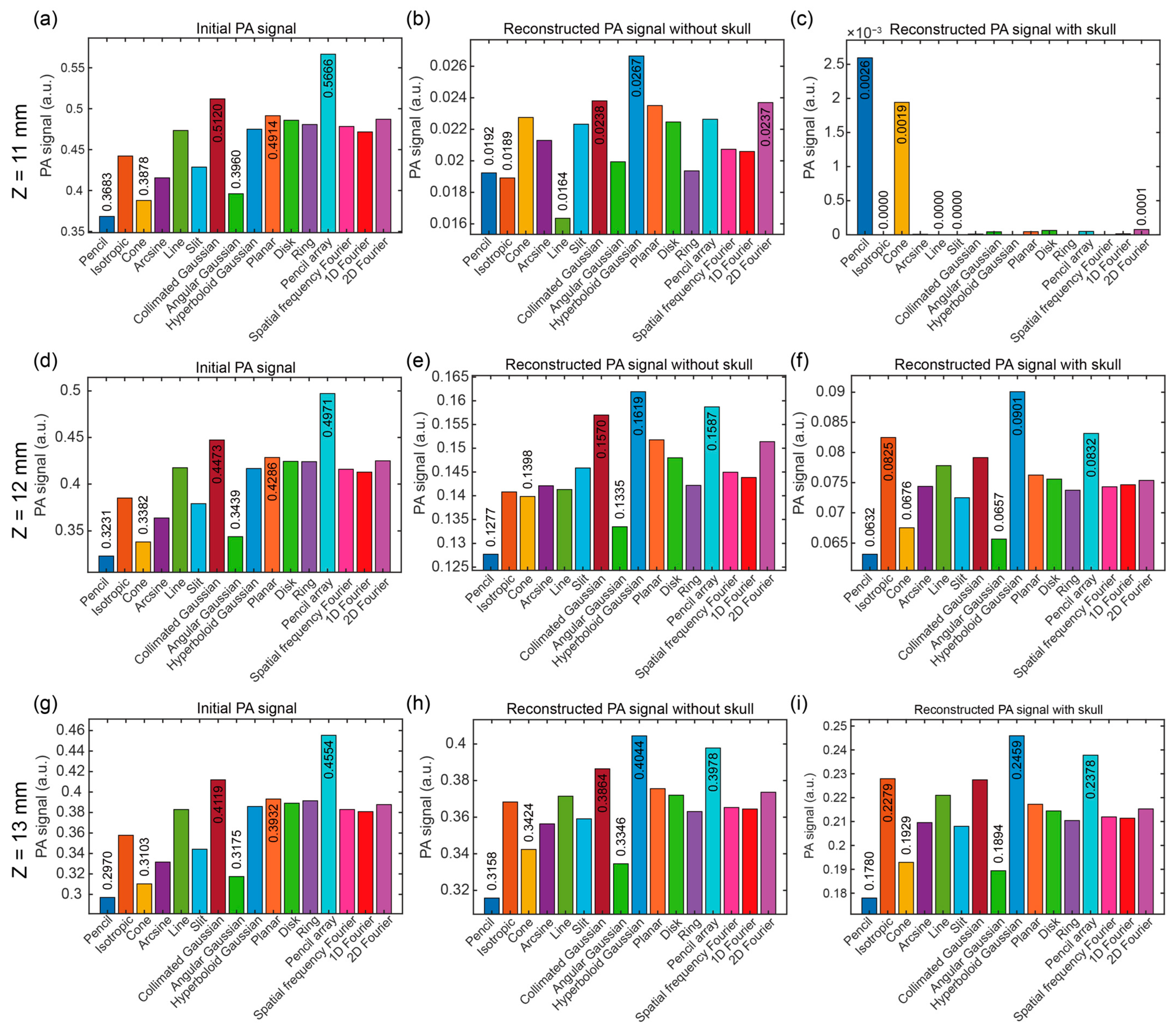

3.4. Discussion of Optical Source Types at Different Positions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Insel, T.R.; Landis, S.C.; Collins, F.S. The NIH BRAIN Initiative. Science 2013, 340, 687–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Wang, L.V. Photoacoustic brain imaging: From microscopic to macroscopic scales. Neurophotonics 2014, 1, 011003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, S.; Russin, J.J.; Lin, L.; Yuan, X.; Hu, P.; Jann, K.B.; Yan, L.; Maslov, K.; Shi, J.; Wang, D.J.; et al. Massively parallel functional photoacoustic computed tomography of the human brain. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 6, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Y.H.; Xia, F.; Sawan, M. Photoacoustic imaging for monitoring of stroke diseases: A review. Photoacoustics 2021, 23, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Wang, R.; Yu, X.; Wei, J.; Song, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, P.; Qiu, J.; et al. Analysis of the influence of skull on photon transmission based on Monte Carlo method. In Proceedings of the 24th National Laser Conference & Fifteenth National Conference on Laser Technology and Optoelectronics, Shanghai, China, 17–20 October 2020; p. 1171722. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Wang, R.; Wei, J.; Song, L. Simulation study of the transmission of photons in mouse brain using Monte Carlo method. In Proceedings of the Biophotonics and Biomedical Microscopy, SPIE Photonex and Vacuum Expo, Online Only, 5–9 October 2020; p. 115750G. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodkalayeh, S.; Lu, X.; Ansari, M.A.; Li, H.; Nasiriavanaki, M. Optimization of light illumination for photoacoustic computed tomography of human infant brain. In Proceedings of the Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing 2018, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 January–1 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Chai, C.; Zuo, H.; Chen, Y.-H.; Shi, J.; Ma, C.; Sawan, M. Monte Carlo-Based Optical Simulation of Optical Distribution in Deep Brain Tissues Using Sixteen Optical Sources. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, B.; Wang, S.; Shen, F.; Liu, Q.H.; Gong, Y.; Yao, J. Acoustic impact of the human skull on transcranial photoacoustic imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 2021, 12, 1512–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneipp, M.; Turner, J.; Estrada, H.; Rebling, J.; Shoham, S.; Razansky, D. Effects of the murine skull in optoacoustic brain microscopy. J. Biophotonics 2016, 9, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, H.; Rebling, J.; Razansky, D. Prediction and near-field observation of skull-guided acoustic waves. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, H.; Rebling, J.; Razansky, D. Observation of skull-guided acoustic waves in a water-immersed murine skull using optoacoustic excitation. In Proceedings of the Optical Elastography and Tissue Biomechanics IV, SPIE BiOS, San Francisco, CA, USA, 28 January–2 February 2017; p. 1006710. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada, H.; Rebling, J.; Turner, J.; Razansky, D. Broadband acoustic properties of a murine skull. Phys. Med. Biol. 2016, 61, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, L.; Behnam, H.; Nasiriavanaki, M.R. Modeling skull’s acoustic attenuation and dispersion on photoacoustic signal. In Proceedings of the Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing 2017, SPIE BiOS, San Francisco, CA, USA, 28 January–2 February 2017; p. 100643J. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Y.; Gao, Z.; Yang, C.; Liang, M.; Gao, F.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H.; Gao, F. Photoacoustic digital brain and deep-learning-assisted image reconstruction. Photoacoustics 2023, 31, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Lu, M.; Zhou, T.; Bu, M.; Gu, W.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, X.; Ta, D. Removing Artifacts in Transcranial Photoacoustic Imaging With Polarized Self-Attention Dense-UNet. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2024, 50, 1530–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, E.; Delpy, D.T. Near-infrared light propagation in an adult head model. II. Effect of superficial tissue thickness on the sensitivity of the near-infrared spectroscopy signal. Appl. Opt. 2003, 42, 2915–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B.; Lang, S.; Dominietto, M.; Rudin, M.; Schulz, G.; Deyhle, H.; Germann, M.; Pfeiffer, F.; David, C.; Weitkamp, T. High-resolution tomographic imaging of microvessels. In Proceedings of the Developments in X-Ray Tomography VI, Optical Engineering + Applications, San Diego, CA, USA, 10–14 August 2008; p. 70780B. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Gong, H.; Luo, Q. Visualization of light propagation in visible Chinese human head for functional near-infrared spectroscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011, 16, 045001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Nina-Paravecino, F.; Kaeli, D.; Fang, Q. Scalable and massively parallel Monte Carlo photon transport simulations for heterogeneous computing platforms. J. Biomed. Opt. 2018, 23, 010504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.V.; Wu, H.-I. Biomedical Optics: Principles and Imaging; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Treeby, B.E.; Cox, B.T. k-Wave: MATLAB toolbox for the simulation and reconstruction of photoacoustic wave fields. J. Biomed. Opt. 2010, 15, 021314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Adaptive dual-speed ultrasound and photoacoustic computed tomography. Photoacoustics 2022, 27, 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, M. Improving tangential resolution with a modified delay-and-sum reconstruction algorithm in photoacoustic and thermoacoustic tomography. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2014, 31, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Srishti; Periyasamy, V.; Pramanik, M. Photoacoustic imaging depth comparison at 532-, 800-, and 1064-nm wavelengths: Monte Carlo simulation and experimental validation. J. Biomed. Opt. 2019, 24, 121904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xue, C.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Wu, L. Photon penetration depth in human brain for light stimulation and treatment: A realistic Monte Carlo simulation study. J. Innov. Opt. Health Sci. 2017, 10, 1743002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Brain Tissues | Absorption Coefficient, μa (1/mm) | Scattering Coefficient, μs (1/mm) | Anisotropy Factor, g | Refractive Index, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scalp | 0.018 | 19.0 | 0.9 | 1.37 |

| Skull | 0.016 | 16.0 | 0.9 | 1.43 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid | 0.004 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 1.33 |

| Gray matter | 0.036 | 22.0 | 0.9 | 1.37 |

| Blood vessel | 0.223 | 50.0 | 0.99 | 1.4 |

| Position | Optical Sources of the First Three Maximum PA Signals | Optical Sources of the First Three Minimum PA Signals |

|---|---|---|

| z = 11 mm, x = 7 mm | 1. Pencil array (0.5666 a.u.) 2. Collimated Gaussian (0.5120 a.u.) 3. Planar (0.4914 a.u.) | 1. Pencil (0.3683 a.u.) 2. Cone (0.3878 a.u.) 3. Angular Gaussian (0.3960 a.u.) |

| z = 12 mm, x = 7 mm | 1. Pencil array (0.4971 a.u.) 2. Collimated Gaussian (0.4473 a.u.) 3. Planar (0.4286 a.u.) | 1. Pencil (0.3231 a.u.) 2. Cone (0.3382 a.u.) 3. Angular Gaussian (0.3439 a.u.) |

| z = 13 mm, x = 7 mm | 1. Pencil array (0.4554 a.u.) 2. Collimated Gaussian (0.4119 a.u.) 3. Planar (0.3932 a.u.) | 1. Pencil (0.2970 a.u.) 2. Cone (0.3103 a.u.) 3. Angular Gaussian (0.3175 a.u.) |

| Position | Optical Sources of the First Three Maximum PA Signals | Optical Sources of the First Three Minimum PA Signals |

|---|---|---|

| z = 11 mm, x = 7 mm | 1. Hyperboloid Gaussian (0.0267 a.u.) 2. Collimated Gaussian (0.0238 a.u.) 3.2D Fourier (0.0237 a.u.) | 1. Line (0.0164 a.u.) 2. Isotropic (0.0189 a.u.) 3. Pencil (0.0192 a.u.) |

| z = 12 mm, x = 7 mm | 1. Hyperboloid Gaussian (0.1619 a.u.) 2. Pencil array (0.1587 a.u.) 3. Collimated Gaussian (0.1570 a.u.) | 1. Pencil (0.1277 a.u.) 2. Angular Gaussian (0.1335 a.u.) 3. Cone (0.1398 a.u.) |

| z = 13 mm, x = 7 mm | 1. Hyperboloid Gaussian (0.4044 a.u.) 2. Pencil array (0.3978 a.u.) 3. Collimated Gaussian (0.3864 a.u.) | 1. Pencil (0.3158 a.u.) 2. Angular Gaussian (0.3346 a.u.) 3. Cone (0.3424 a.u.) |

| Position | Optical Sources of the First Three Maximum PA Signals | Optical Sources of the First Three Minimum PA Signals |

|---|---|---|

| z = 11 mm, x = 7 mm | 1. Pencil (0.0026 a.u.) 2. Cone (0.00019 a.u.) 3.2D Fourier (0.0001 a.u.) | 1. Isotropic (0.0000 a.u.) 2. Line (0.0000 a.u.) 3. Slit (0.0000 a.u.) |

| z = 12 mm, x = 7 mm | 1. Hyperboloid Gaussian (0.0901 a.u.) 2. Pencil array (0.0832 a.u.) 3. Isotropic (0.0825 a.u.) | 1. Pencil (0.0632 a.u.) 2. Angular Gaussian (0.0657 a.u.) 3. Cone (0.0676 a.u.) |

| z = 13 mm, x = 7 mm | 1. Hyperboloid Gaussian (0.2459 a.u.) 2. Pencil array (0.2378 a.u.) 3. Isotropic (0.2279 a.u.) | 1. Pencil (0.1780 a.u.) 2. Angular Gaussian (0.1894 a.u.) 3. Cone (0.1929 a.u.) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Chai, C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Sawan, M. Skull Impact on Photoacoustic Imaging of Multi-Layered Brain Tissues with Embedded Blood Vessel Under Different Optical Source Types: Modeling and Simulation. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12010040

Yang X, Chai C, Chen Y-H, Sawan M. Skull Impact on Photoacoustic Imaging of Multi-Layered Brain Tissues with Embedded Blood Vessel Under Different Optical Source Types: Modeling and Simulation. Bioengineering. 2025; 12(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xi, Chengpeng Chai, Yun-Hsuan Chen, and Mohamad Sawan. 2025. "Skull Impact on Photoacoustic Imaging of Multi-Layered Brain Tissues with Embedded Blood Vessel Under Different Optical Source Types: Modeling and Simulation" Bioengineering 12, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12010040

APA StyleYang, X., Chai, C., Chen, Y.-H., & Sawan, M. (2025). Skull Impact on Photoacoustic Imaging of Multi-Layered Brain Tissues with Embedded Blood Vessel Under Different Optical Source Types: Modeling and Simulation. Bioengineering, 12(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12010040