In Vitro Analysis of TGF-β Signaling Modulation of Porcine Alveolar Macrophages in Porcine Circovirus Type 2b Infection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Isolation of PAM Cells

2.2. Virus Preparation for Infection

2.3. Detection of PCV2 in PAMs

2.4. RNA Extraction and cDNA Preparation

2.5. RT2 Profiler PCR Array Assay

2.6. Analysis of TGF-β Expressions

2.7. Co-Expression Network Analysis

2.8. Statistic Analysis

3. Results

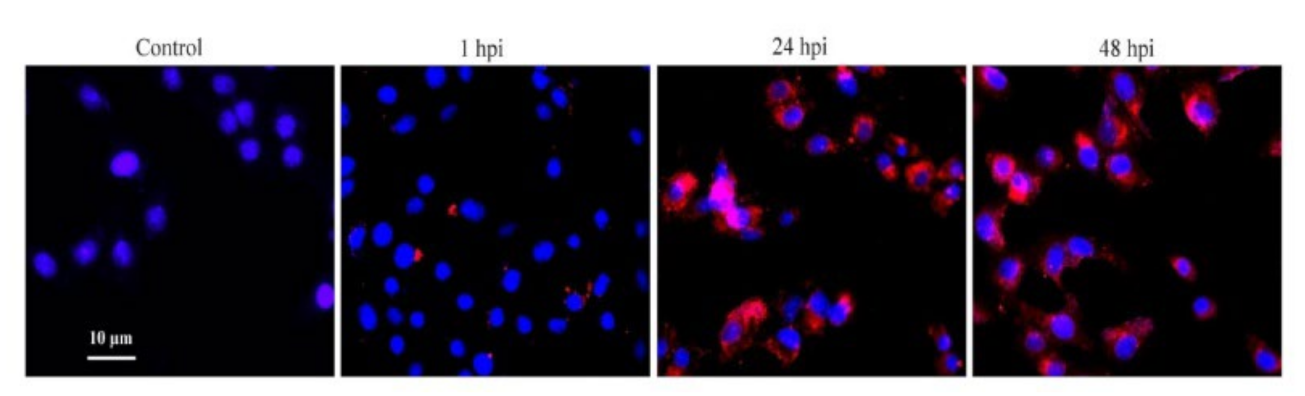

3.1. Confirmation of PCV2b Infection in PAMs

3.2. MRNA Expression Profiles

3.3. Expression Analyses of TGF-β in PCV2b-Infected PAMs

3.4. Network Modularity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, X.J. Spread like a wildfire--the omnipresence of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) and its ever-expanding association with diseases in pigs. Virus Res. 2012, 164, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, X.; Wang, F.; Guo, X.; Yang, H. Porcine circovirus type 2 and its associated diseases in China. Virus Res. 2012, 164, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segales, J.; Rose, C., II; Domingo, M. Pathological findings associated with naturally acquired porcine circovirus type 2 associated disease. Vet. Microbiol. 2004, 98, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwich, L.; Segales, J.; Domingo, M.; Mateu, E. Changes in CD4(+), CD8(+), CD4(+) CD8(+), and immunoglobulin M-positive peripheral blood mononuclear cells of postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome-affected pigs and age-matched uninfected wasted and healthy pigs correlate with lesions and porcine circovirus type 2 load in lymphoid tissues. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2002, 9, 236–242. [Google Scholar]

- Segales, J.; Domingo, M.; Chianini, F.; Majo, N.; Dominguez, J.; Darwich, L.; Mateu, E. Immunosuppression in postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome affected pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 2004, 98, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Carino, C.; Duffy, C.; Sanchez-Chardi, A.; McNeilly, F.; Allan, G.M.; Segales, J. Porcine circovirus type 2 morphogenesis in a clone derived from the l35 lymphoblastoid cell line. J. Comp. Pathol. 2011, 144, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrioli, L.; Sarli, G.; Panarese, S.; Baldoni, S.; Marcato, P.S. Apoptosis and proliferative activity in lymph node reaction in postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome (PMWS). Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2004, 97, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Opriessnig, T.; Kitikoon, P.; Nilubol, D.; Halbur, P.G.; Thacker, E. Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) distribution and replication in tissues and immune cells in early infected pigs. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2007, 115, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.M.; Jeng, C.R.; Hsiao, S.H.; Liu, J.P.; Chang, C.C.; Chiou, M.T.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chia, M.Y.; Pang, V.F. Immunopathological characterization of porcine circovirus type 2 infection-associated follicular changes in inguinal lymph nodes using high-throughput tissue microarray. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 149, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwich, L.; Mateu, E. Immunology of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2). Virus Res. 2012, 164, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikstrom, F.H.; Fossum, C.; Fuxler, L.; Kruse, R.; Lovgren, T. Cytokine induction by immunostimulatory DNA in porcine PBMC is impaired by a hairpin forming sequence motif from the genome of Porcine Circovirus type 2 (PCV2). Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2011, 139, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Han, D.; Song, J.Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Kang, K.S.; Yoon, S. Genomic expression profiling in lymph nodes with lymphoid depletion from porcine circovirus 2-infected pigs. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 2585–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.Q.; Yin, S.H.; Guo, H.C.; Jin, Y.; Shang, Y.J.; Liu, X.T. Genetic typing of classical swine fever virus isolates from China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2013, 60, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrommatis, B.; Offord, V.; Patterson, R.; Watson, M.; Kanellos, T.; Steinbach, F.; Grierson, S.; Werling, D. Global gene expression profiling of myeloid immune cell subsets in response to in vitro challenge with porcine circovirus 2b. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qin, Y.; Li, H.; Qiao, J. TLR2/MyD88/NF-kappaB signalling pathway regulates IL-8 production in porcine alveolar macrophages infected with porcine circovirus 2. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, N.; Krieglstein, K. Mechanisms of TGF-beta-mediated apoptosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2002, 307, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J. The Role of Tripartite Motif Family Proteins in TGF-beta Signaling Pathway and Cancer. J. Cancer Prev. 2018, 23, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ebert, P.J.; Li, Q.J. T cell receptor (TCR) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) signaling converge on DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase to control forkhead box protein 3 (foxp3) locus methylation and inducible regulatory T cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 19127–19139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oh, S.A.; Li, M.O. TGF-beta: Guardian of T cell function. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 3973–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.O.; Sanjabi, S.; Flavell, R.A. Transforming growth factor-beta controls development, homeostasis, and tolerance of T cells by regulatory T cell-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Immunity 2006, 25, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, M.O.; Wan, Y.Y.; Flavell, R.A. T cell-produced transforming growth factor-beta1 controls T cell tolerance and regulates Th1- and Th17-cell differentiation. Immunity 2007, 26, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Derynck, R.; Zhang, Y.E. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature 2003, 425, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, V.; Manickam, C.; Patterson, R.; Dodson, K.; Murtaugh, M.; Torrelles, J.B.; Schlesinger, L.S.; Renukaradhya, G.J. Cross-protective immunity to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus by intranasal delivery of a live virus vaccine with a potent adjuvant. Vaccine 2011, 29, 4058–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeRoith, T.; Hammond, S.; Todd, S.M.; Ni, Y.; Cecere, T.; Pelzer, K.D. A modified live PRRSV vaccine and the pathogenic parent strain induce regulatory T cells in pigs naturally infected with Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2011, 140, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renukaradhya, G.J.; Alekseev, K.; Jung, K.; Fang, Y.; Saif, L.J. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus-Induced Immunosuppression Exacerbates the Inflammatory Response to Porcine Respiratory Coronavirus in Pigs. Viral. Immunol. 2010, 23, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renukaradhya, G.J.; Dwivedi, V.; Manickam, C.; Binjawadagi, B.; Benfield, D. Mucosal vaccines to prevent porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome: A new perspective. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2012, 13, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera, A.; Ballester, M.; Nofrarias, M.; Sibila, M.; Aragon, V. Differences in phagocytosis susceptibility in Haemophilus parasuis strains. Vet. Res. 2009, 40, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, S.; Liu, B.; Yin, S.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Khan, M.U.Z.; Liu, X.; Cai, J. Porcine Circovirus Type 2 Induces Single Immunoglobulin Interleukin-1 Related Receptor (SIGIRR) Downregulation to Promote Interleukin-1beta Upregulation in Porcine Alveolar Macrophage. Viruses 2019, 11, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McIntosh, K.A.; Tumber, A.; Harding, J.C.; Krakowka, S.; Ellis, J.A.; Hill, J.E. Development and validation of a SYBR green real-time PCR for the quantification of porcine circovirus type 2 in serum, buffy coat, feces, and multiple tissues. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 133, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L.; Shang, Y.J.; Wang, D.; Yin, S.H.; Cai, J.P.; Liu, X.T. Diagnosis of porcine circovirus type 2 infection with a combination of immunomagnetic beads, single-domain antibody, and fluorescent quantum dot probes. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 2325–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Morris, J.H.; Demchak, B.; Bader, G.D. Biological network exploration with cytoscape 3. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2014, 47, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bader, G.D.; Hogue, C.W. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinform. 2003, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, D.; Lee, Y.G.; Liu, H.C.; Yuan, R.Y.; Chiou, H.Y.; Hung, C.H.; Hu, C.J. Identification of TLR downstream pathways in stroke patients. Clin. Biochem. 2013, 46, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trager, U.; Andre, R.; Lahiri, N.; Magnusson-Lind, A.; Weiss, A.; Grueninger, S.; McKinnon, C.; Sirinathsinghji, E.; Kahlon, S.; Pfister, E.L.; et al. HTT-lowering reverses Huntington’s disease immune dysfunction caused by NFkappaB pathway dysregulation. Brain A J. Neurol. 2014, 137, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.G.; Cunningham, G.L.; Sanford, S.E. Circovirus vaccination in pigs with subclinical porcine circovirus type 2 infection complicated by ileitis. J. Swine Health Prod. 2011, 19, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, N.M.; Meng, X.J. Efficacy and future prospects of commercially available and experimental vaccines against porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2). Virus Res. 2012, 164, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, T.W. A review of evidence for immunosuppression due to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet Res 2000, 31, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, C.J.; Liao, C.H.; Wang, F.H.; Lin, C.M. Transforming growth factor-beta induces apoptosis in antigen-specific CD4+ T cells prepared for adoptive immunotherapy. Immunol. Lett. 2003, 86, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldin, C.H.; Landstrom, M.; Moustakas, A. Mechanism of TGF-beta signaling to growth arrest, apoptosis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009, 21, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Capelo, A. Dual role for TGF-beta1 in apoptosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005, 16, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilpin, D.F.; McCullough, K.; Meehan, B.M.; McNeilly, F.; McNair, I.; Stevenson, L.S.; Foster, J.C.; Ellis, J.A.; Krakowka, S.; Adair, B.M.; et al. In vitro studies on the infection and replication of porcine circovirus type 2 in cells of the porcine immune system. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2003, 94, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.W.; Jeng, C.R.; Lin, T.L.; Liu, J.J.; Chiou, M.T.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chia, M.Y.; Jan, T.R.; Pang, V.F. Immunopathological effects of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) on swine alveolar macrophages by in vitro inoculation. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2006, 110, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.W.; Jeng, C.R.; Liu, J.J.; Lin, T.L.; Chang, C.C.; Chia, M.Y.; Tsai, Y.C.; Pang, V.F. Reduction of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) infection in swine alveolar macrophages by porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2)-induced interferon-alpha. Vet. Microbiol. 2005, 108, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conery, A.R.; Cao, Y.; Thompson, E.A.; Townsend, C.M., Jr.; Ko, T.C.; Luo, K. Akt interacts directly with Smad3 to regulate the sensitivity to TGF-beta induced apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhurst, R.J.; Hata, A. Targeting the TGFbeta signalling pathway in disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 790–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heldin, C.H.; Miyazono, K.; ten Dijke, P. TGF-beta signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature 1997, 390, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollah, S.; MaciasSilva, M.; Tsukazaki, T.; Hayashi, H.; Attisano, L.; Wrana, J.L. T beta RI phosphorylation of Smad2 on Ser(465) and Ser(467) is required for Smad2-Smad4 complex formation and signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 27678–27685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Letai, A.G. Diagnosing and exploiting cancer’s addiction to blocks in apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory, S.; Huang, D.C.S.; Adams, J.M. The Bcl-2 family: Roles in cell survival and oncogenesis. Oncogene 2003, 22, 8590–8607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cain, D.W.; O’Koren, E.G.; Kan, M.J.; Womble, M.; Sempowski, G.D.; Hopper, K.; Gunn, M.D.; Kelsoe, G. Identification of a tissue-specific, C/EBPbeta-dependent pathway of differentiation for murine peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 4665–4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruffell, D.; Mourkioti, F.; Gambardella, A.; Kirstetter, P.; Lopez, R.G.; Rosenthal, N.; Nerlov, C. A CREB-C/EBPbeta cascade induces M2 macrophage-specific gene expression and promotes muscle injury repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17475–17480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tamura, A.; Hirai, H.; Yokota, A.; Sato, A.; Shoji, T.; Kashiwagi, T.; Iwasa, M.; Fujishiro, A.; Miura, Y.; Maekawa, T. Accelerated apoptosis of peripheral blood monocytes in Cebpb-deficient mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 464, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papa, S.; Zazzeroni, F.; Bubici, C.; Jayawardena, S.; Alvarez, K.; Matsuda, S.; Nguyen, D.U.; Pham, C.G.; Nelsbach, A.H.; Melis, T.; et al. Gadd45 beta mediates the NF-kappa B suppression of JNK signalling by targeting MKK7/JNKK2. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchimochi, K.; Otero, M.; Dragomir, C.L.; Plumb, D.A.; Zerbini, L.F.; Libermann, T.A.; Marcu, K.B.; Komiya, S.; Ijiri, K.; Goldring, M.B. GADD45beta enhances Col10a1 transcription via the MTK1/MKK3/6/p38 axis and activation of C/EBPbeta-TAD4 in terminally differentiating chondrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 8395–8407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, W.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Deng, F.; Yan, W.; Yang, K.; Chen, H.; He, Q.; Charreyre, C.; Audoneet, J.C. Transcription analysis of the porcine alveolar macrophage response to porcine circovirus type 2. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Gene Symbol | Description | Fold Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 hpi | 24 hpi | 48 hpi | ||

| Regulation of Transcription and Transcription Factor Activity | ||||

| C/EBPB | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), beta | 4.96 | 2.87 | 2.55 |

| CREBBP | CREB binding protein | 8.75 | 4.33 | 3.66 |

| HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | 7.53 | 4.49 | 3.50 |

| IL10 | Interleukin 10 | 5.97 | 4.69 | 4.68 |

| GADD45B | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, beta | 5.62 | 2.71 | 3.07 |

| NFKBIA | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha | 8.67 | 5.95 | 3.99 |

| RYBP | RING1 and YY1 binding protein | 3.42 | 1.59 | 1.54 |

| ID3 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 3, dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein | 1.28 | 6.84 | 28.03 |

| RUNX1 | Runt-related transcription factor 1 | 5.78 | 1.03 | 1.76 |

| MBD1 | Methyl-CpG binding domain protein 1 | 1.95 | 1.49 | 1.65 |

| SERPINE1 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E (nexin, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1), member 1 | 4.17 | –1.12 | 1.93 |

| ID2 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 2, dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein | 1.84 | –1.01 | 2.99 |

| ATF4 | Activating transcription factor 4 (tax-responsive enhancer element B67) | 2.08 | 1.26 | 1.15 |

| ATP1B1 | ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, beta 1 polypeptide | 5.83 | 1.49 | −1.22 |

| BACH1 | BTB and CNC homology 1, basic leucine zipper transcription factor 1 | 5.48 | 1.06 | −1.04 |

| BHLHE40 | Basic helix-loop-helix family, member e40 | 2.76 | 1.32 | 1.43 |

| FOXO1 | Forkhead box O1 | 1.85 | 1.15 | 1.33 |

| PTK2B | PTK2B protein tyrosine kinase 2 beta | 1.79 | −1.01 | −1.01 |

| TXNIP | Thioredoxin interacting protein | 1.55 | −1.28 | 1.19 |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor-A | 12.49 | 1.52 | 1.91 |

| MAPK8 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 | 1.54 | −1.01 | −1.31 |

| IFRD1 | Interferon-related developmental regulator 1 | 3.87 | 1.04 | −1.25 |

| LOC396709 | Retinoic acid receptor alpha | 2.89 | 1.15 | 1.17 |

| HSP90AA1 | 90-kDa heat shock protein | 1.50 | 1.36 | 1.15 |

| LOC100620797 | Focal adhesion kinase 1-like | 1.39 | 1.39 | 1.79 |

| CTNNB1 | Catenin (cadherin-associated protein), beta 1, 88 kDa | 1.43 | 1.67 | 1.02 |

| SP1 | Sp1 transcription factor | −1.01 | 1.52 | 1.41 |

| PTGS2 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase-2 | 21.61 | 2.25 | −5.99 |

| RGS4 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 4 | 2.39 | 7.21 | −2.49 |

| FURIN | Furin-like | 2.50 | −1.18 | −1.57 |

| JARID2 | Jumonji, AT rich interactive domain 2 | 1.63 | −1.12 | −1.74 |

| EMP1 | Epithelial membrane protein 1 | 3.35 | −1.52 | −3.65 |

| TNFSF10 | Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 10 | −4.98 | 3.95 | 13.72 |

| MAPK14 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 | −1.95 | 1.67 | 1.63 |

| STC2 | Stanniocalcin 2 | −2.06 | −1.57 | −1.52 |

| ME2 | Malic enzyme 2, NAD(+)-dependent, mitochondrial | −1.63 | −1.18 | −1.60 |

| GTF2I | General transcription factor IIi | −3.86 | −1.07 | 1.34 |

| PPARA | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha | −3.69 | 1.41 | 1.39 |

| Regulation of programmed cell death and apoptosis | ||||

| TGFB2 | Transforming growth factor, beta 2 | 1.76 | 3.94 | 6.36 |

| S100A8 | S100 calcium binding protein A8 | 2.91 | 14.55 | 20.75 |

| SMAD6 | SMAD family member 6 | 2.10 | −1.01 | 1.44 |

| BCL2L1 | BCL2-like 1 | 1.16 | 1.68 | 1.59 |

| CDKN1B | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (p27, Kip1) | −1.22 | 1.73 | 2.20 |

| FOS | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | −2.63 | 2.37 | 18.83 |

| FN1 | Fibronectin 1 | 1.74 | −1.12 | 3.78 |

| MMP2 | Matrix metallopeptidase 2 (gelatinase A, 72kDa gelatinase, 72kDa type IV collagenase) | −1.96 | 1.23 | 2.88 |

| ACVR1 | Activin A receptor, type I | −1.15 | −1.58 | −1.82 |

| ACVRL1 | Activin A receptor type II-like 1 | −1.18 | −1.69 | −1.78 |

| MYC | V-myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog (avian) | −1.39 | −3.56 | −6.66 |

| HES1 | Hairy and enhancer of split 1, (Drosophila) | −1.33 | −2.15 | −3.09 |

| JUP | Junction plakoglobin | −1.30 | 1.00 | −3.28 |

| SMAD1 | SMAD family member 1 | −2.66 | −2.60 | 1.17 |

| SMAD3 | SMAD family member 3 | −2.12 | −4.28 | −1.08 |

| EPHB2 | EPH receptor B2 | −1.00 | −1.73 | −1.21 |

| No explicit function annotation | ||||

| CRYAB | Crystallin, alpha B | −1.25 | −2.25 | 1.56 |

| SREBF2 | Sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 2 | −1.41 | −1.90 | −5.81 |

| ENG | Endoglin | 1.58 | 1.39 | 2.08 |

| BRF2 | Zinc finger protein 36, C3H type-like 2 | 1.33 | 1.21 | 1.93 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Zafar Khan, M.U.; Liu, B.; Humza, M.; Yin, S.; Cai, J. In Vitro Analysis of TGF-β Signaling Modulation of Porcine Alveolar Macrophages in Porcine Circovirus Type 2b Infection. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9030101

Yang S, Zafar Khan MU, Liu B, Humza M, Yin S, Cai J. In Vitro Analysis of TGF-β Signaling Modulation of Porcine Alveolar Macrophages in Porcine Circovirus Type 2b Infection. Veterinary Sciences. 2022; 9(3):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9030101

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Shunli, Muhammad Umar Zafar Khan, Baohong Liu, Muhammad Humza, Shuanghui Yin, and Jianping Cai. 2022. "In Vitro Analysis of TGF-β Signaling Modulation of Porcine Alveolar Macrophages in Porcine Circovirus Type 2b Infection" Veterinary Sciences 9, no. 3: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9030101

APA StyleYang, S., Zafar Khan, M. U., Liu, B., Humza, M., Yin, S., & Cai, J. (2022). In Vitro Analysis of TGF-β Signaling Modulation of Porcine Alveolar Macrophages in Porcine Circovirus Type 2b Infection. Veterinary Sciences, 9(3), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9030101