Abstract

The genus Tarzetta is distributed mainly in temperate forests and establishes ectomycorrhizal associations with angiosperms and gymnosperms. Studies on this genus are scarce in México. A visual, morphological, and molecular (ITS-LSU) description of T. americupularis, T. cupressicola, T. davidii, T. durangensis, T. mesophila, T. mexicana, T. miquihuanensis, T. poblana, T. pseudobronca, T. texcocana, and T. victoriana was carried out in this work, associated with Abies, Quercus, and Pinus. The results of SEM showed an ornamented ascospores formation by Mexican Taxa; furthermore, the results showed that T. catinus and T. cupularis are only distributed in Europe and are not associated with any American host.

1. Introduction

Recently, the family Tarzettaceae (Pezizales, Pezizomycetes) was erected by Ekanayaka et al. [1] based on multigene phylogenetic analysis (ITS, LSU, SSU, and tef1-α, rpb2) and was segregated from the family Pyronemataceae according to Perry et al. [2]. Previously, the family Pyronemataceae was considered polyphyletic by Hansen et al. [3] with the Geopyxis lineage and by Kumar et al. [4] with the Tarzetta–Geopyxis lineage. Currently, this family is represented by Tarzetta (Cooke) Lambotte as the type genus Geopyxis (Pers.) Sacc, Hydnocystis Tul. & C. Tull., Hypotarzetta Donadini, Paurocotylis Berk., and Stephensia Tull. & C. Tul. [1]. However, the Index Fungorum (https://www.indexfungorum.org/, accessed on 15 January 2024) still considers it a monogeneric family. The genus Tarzetta has a restricted distribution mostly in temperate forests, which forms ectomycorrhizal associations, generally with trees and shrubs of the genera Abies Mill., Alnus Mill., Quercus L., Pinus L., and Pseudotsuga Carrière [3,5,6,7]. Tarzetta species are characterized as small to medium apothecia (2–30 mm), sessile to stipitate, deeply cupulate, and grey to beige but sometimes ochraceous or yellowish and rarely orange. Most of the species present a hymenium whitish or concolorous to the external zone of the apothecia, with a margin that is usually denticulate. Microscopically, it has simple to branched paraphyses, septate, and hyaline; asci operculated, inamyloid, 8-spored. Ascospores are broadly ellipsoid, ellipsoid to oblong-ellipsoid, single to bigutulated, and usually smooth although T. jafneospora W.Y. Zhuang & Jorf. has verrucose ornamentation [3,7].

Twenty-three species of Tarzetta have been described worldwide: 16 species from Europe: T. alnicola Van Vooren, T. alpina Van Vooren & Cheype, T. catinus (Holmsk.) Korf & J.K. Rogers, T. cupularis (L.) Lambotte, T. gaillardiana (Boud.) Korf & J.K. Rogers, T. gregaria Van Vooren, T. melitensis Sammut & Van Vooren, T. oblongispora M. Carbone, S. Saitta, L. Sánchez, García Blanco & Van Vooren, T. ochracea (Gillet) Van Vooren, T. pusilla Harmaja, T. quercus-ilicis Van Vooren & M. Carbone, T. scotica (Rea) Y.J. Yao & Spooner, T. sepultarioides Van Vooren, T. spurcata (Pers.) Harmaja, and T. velata (Quél.) Svrček; 4 species from China: T. confusa F.M. Yu, S. Wang, Q. Zhao & K.D. Hyde, T. linzhiensis F.M. Yu, S. Wang, Q. Zhao & K.D. Hyde, T. tibetensis F.M. Yu & Q. Zhao, and T. urceolata L. Lei & Q. Zhao; 3 species from the Americas: T. brasiliensis Rick from Brasil, T. microspora (Raithelh.) Raiithelh, from Argentina, and T. bronca (Peck) Korf & J.K. Rogers from the USA; and 1 species from New Zealand: T. jafneospora [7,8,9,10,11].

Studies on Tarzetta are scarce in Mexico. Some collections of T. catinus and T. cupularis are known from the states of Durango, Hidalgo, Mexico City, Mexico State, Michoacán, Morelos, Oaxaca, and Veracruz [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]; nevertheless, those collections lack complete taxonomic descriptions. Through molecular studies, Van Vooren et al. [7] sorted T. catinus and T. cupularis from the species previously cited with these names for the Americas, mentioning that the taxa in the continent should have greater taxonomic and phylogenetic exploration. This study aims to describe 11 new species of Tarzetta from Mexico, using morphological and molecular data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Colecting and Morphology

The specimens were collected in temperate forests from 2019 to 2023. The collected specimens were deposited in the José Castillo Tovar mycological herbarium of the Insti-tuto Tecnológico de Ciudad Victoria (ITCV), the herbarium of the Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas of the Instituto Politécnico Nacional (ENCB), the herbarium of the Facultad de Estudios Superiores Zaragoza (FEZA) of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and the Mycological Collection of the Universidad Estatal de Sonora (UES). Further, herbarium specimens were analyzed in ENCB, ITCV, and FEZA Herbaria.

The macroscopic morphological characteristics of specimens such as size, shape, and color were described [7]. The Illustrated Dictionary of Mycology was used for morphological terminology [20]. Apothecia colors are described according to Kornerup and Wanscher [21]. Longitudinal cuts of the apothecia were made and rehydrated with 70% alcohol, 5% KOH, water, and cotton blue to observe a possible ornamentation of the ascospores. The microscopic characters such as excipulum, paraphyses, asci, and ascospores were characterized for identification using an optical microscope (OM) (Axiostar plus, Zeiss, Jena, Germany; VE-B1, Velab, Ciudad de México, Mexico). The photographs were taken with a Rebel T-1i camera, a 100 mm macro lens (Canon, Tokyo, Japan), and a DCS-W630 camera (SONY, Tokyo, Japan). Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM; SU1510, Hitachi High Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) was used to observe the ornamentation of the ascospores.

2.2. Extraction, Amplification, and Sequencing of DNA

The DNA was extracted from dried herbarium specimens. Genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method [22]. Two molecular markers were used, and these were the Internal Transcribed Spacer region of nuclear ribosomal DNA (ITS1-5.8-ITS2 nrDNA; hereafter ITS) and the large subunit nrDNA (28S). PCR amplification included 35 cycles with an annealing temperature of 54 °C. It was carried out with the ITS5 and ITS4 primers [23] for the ITS nrDNA region and the LROR and LR5 primers [24] for the 28S nrDNA region (LSU). The PCR products were verified using agarose gel electrophoresis. The gels were run for 1 h at 95 V cm−3 in 1.5% agarose and 1× TAE buffer (Tris Acetate-EDTA, Saint Lois, MO, USA). The gel was stained with GelRed (Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA) and the bands were visualized in an Infinity 3000 transilluminator (Vilber Lourmat, Baden-Wurtemberg, Germany). The amplified products were purified with the ExoSAP Purification kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. They were quantified and prepared for the sequence reaction using a BigDye Terminator v. 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). These products were sequenced in both directions with an Applied Biosystems model 3730XL (Applied BioSystems, Waltham, MA, USA) at the Instituto de Biología of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM).

2.3. Sequence Assembly

The sequences of both strands of each of the genes were analyzed, edited, and assembled using BioEdit version 7.0.5 [25] to generate a consensus sequence, which was compared with those deposited in the GenBank of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), using the tool BLASTN 2.2.19 [26].

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

To study phylogenetic relationships, our newly produced sequences of twenty-six individuals were added to reference sequences of ITS and LSU nrDNA deposited in the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, accessed on 25 January 2024), and an alignment was performed based on the taxonomic sampling employed by Van Vooren et al. [7] and Healy et al. [27] (Table 1). Each region was aligned using the online version of MAFFT v. 7 [28,29]. The alignment was revised in PhyDE v. 10.0 [30], followed by minor manual adjustments to ensure character homology between taxa. The matrix was composed for ITS by 55 taxa (692 characters) and LSU by 61 taxa (800 characters). The data were analyzed using maximum parsimony (MP), maximum likelihood (ML), and Bayesian inference (BI). Maximum parsimony analyses were carried out in PAUP* 4.0b10 [31] using the heuristic search mode, 1000 random starting replicates, and TBR branch swapping with MULTREES and Collapse on.

Table 1.

Taxa information and GenBank accession numbers of the sequences used in this study.

Bootstrap values were estimated using 1000 bootstrap replicates under the heuristic search mode, each with 100 random starting replicates. Maximum likelihood analyses were carried out in RAxML v. 8.2.10 [32] with a GTR + G model of nucleotide substitution. To assess branch support, 10,000 rapid bootstrap replicates were run with the GTRGAMMA model. Bayesian inference was carried out in MrBayes v. 3.2.6 x64 [33] with four chains, and the best evolutionary model for alignment was sought using PartitionFinder v. 2 [34,35,36]. The information block for the matrix includes two simultaneous runs, four Montecarlo chains, a temperature set to 0.2, and a sampling of 10 million generations (standard deviation ≤ 0.1) with trees sampled every 1000 generations. The first 25% of samples were discarded as burn-in, and convergence was evaluated by examining the standard deviation of split frequencies among runs and by plotting the log-likelihood values from each run using Tracer v. 1 [37]. The remaining trees were used to calculate a 50% majority-rule consensus topology and posterior probabilities (PP). Trees were visualized and optimized in FigTree v. 1.4.4 [38].

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Analysis

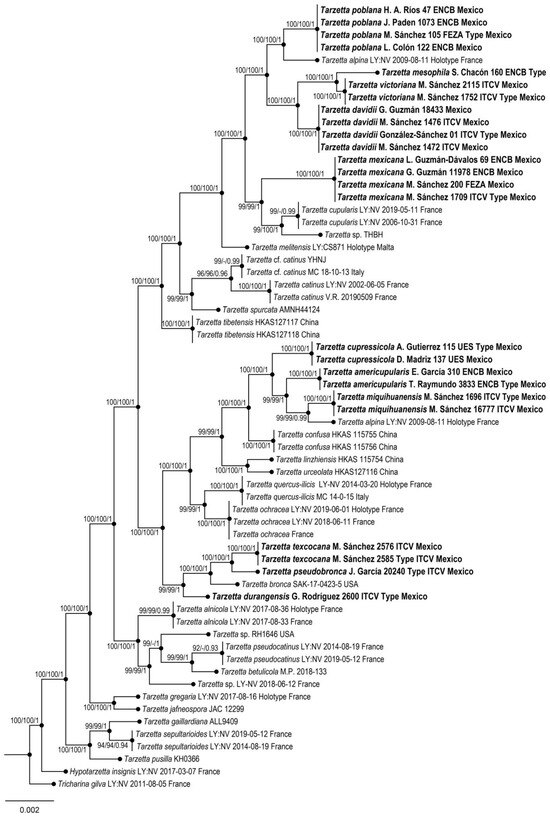

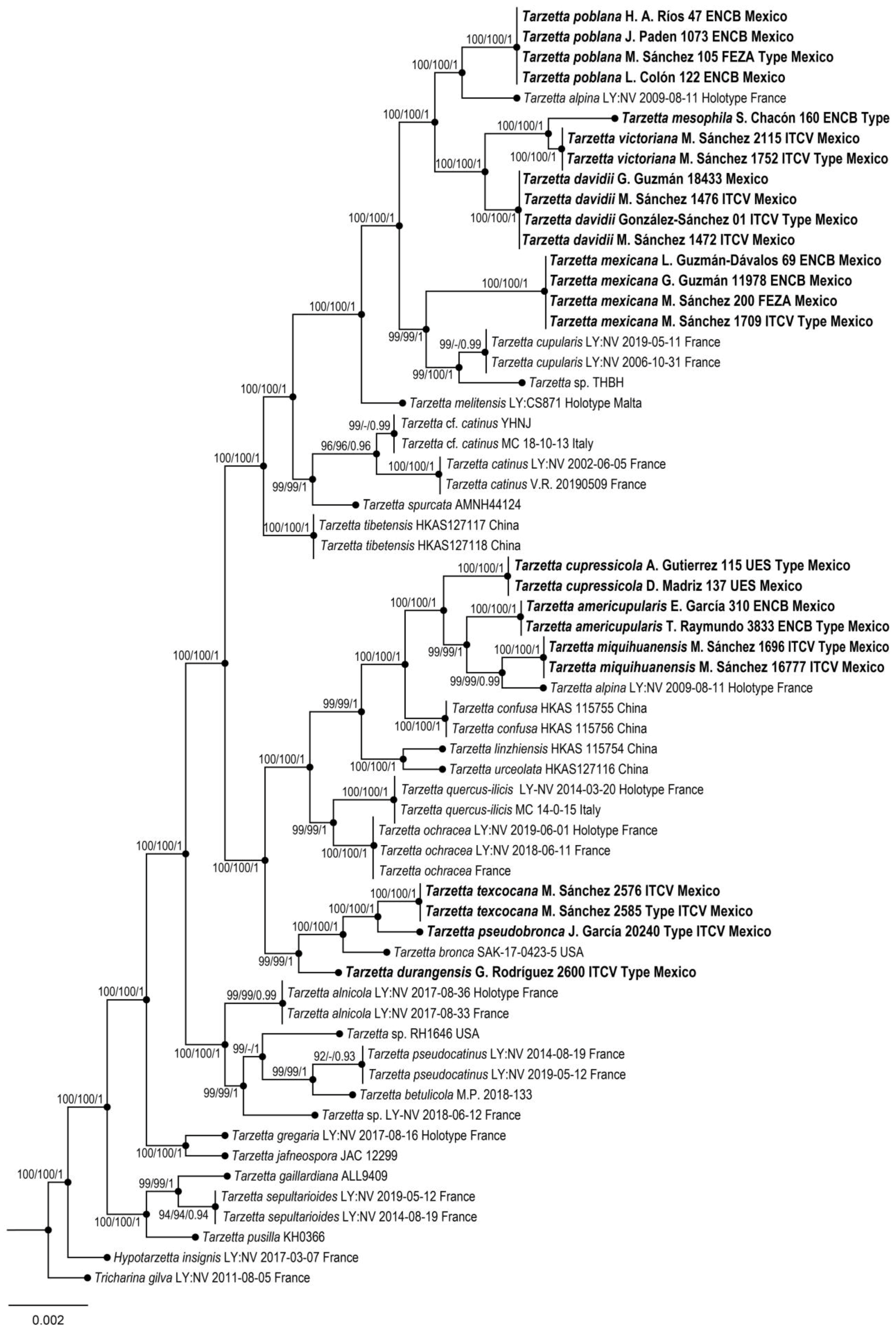

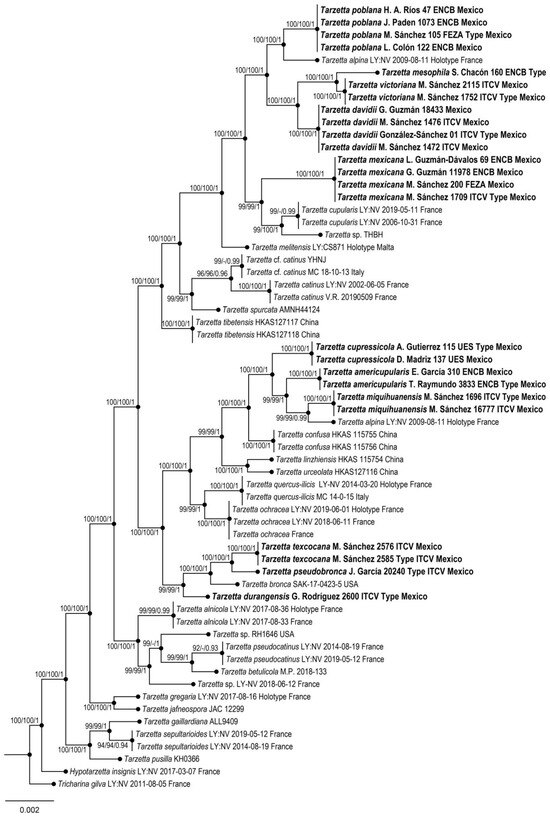

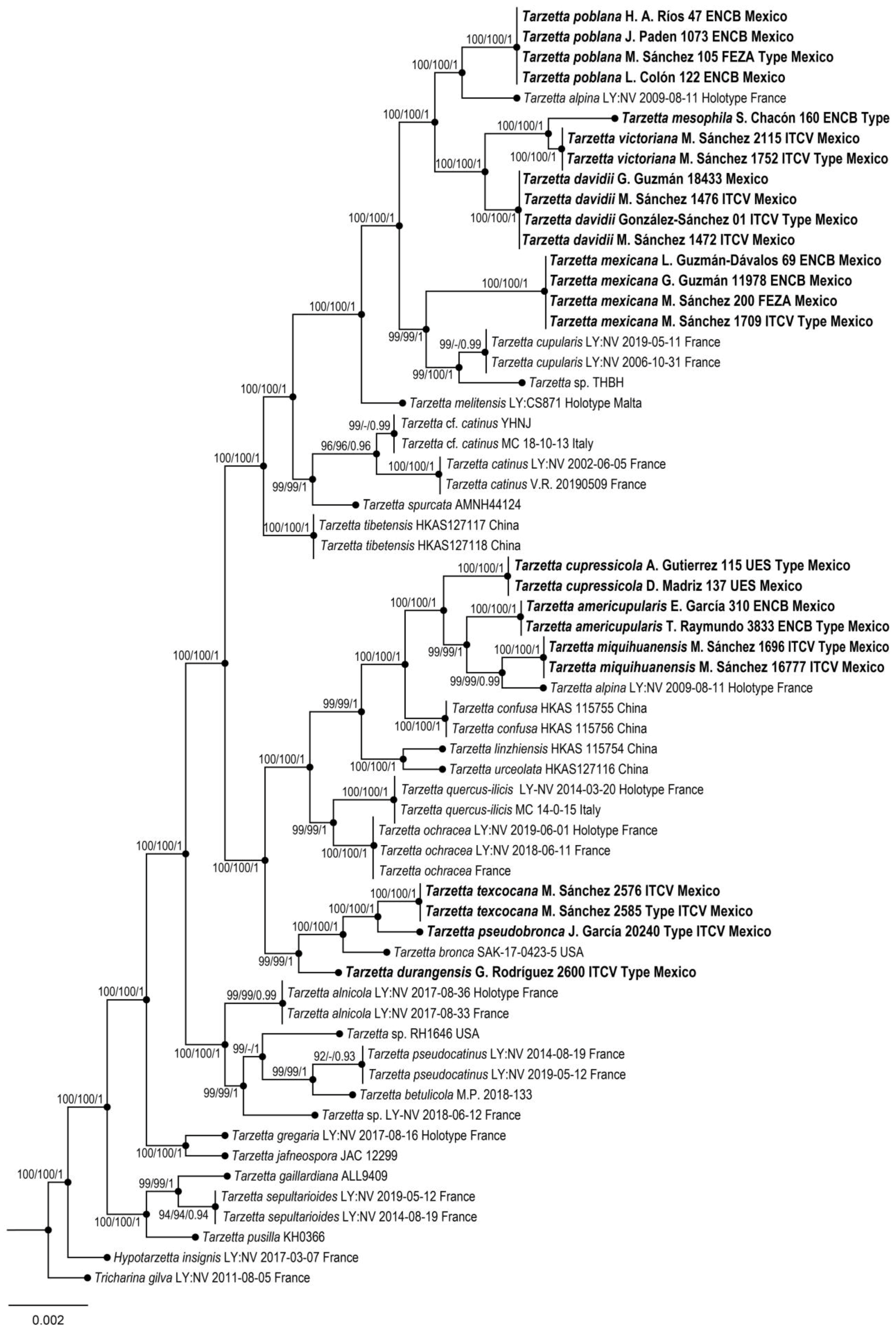

Phylogenetic reconstruction was based on the alignment of the nrITS + LSU dataset (56 taxa, 1520 characters, including gaps). The three phylogenetic analyses of the dataset, MP, ML, and BI, recovered similar topologies (Figure 1). No significant conflict (bootstrap value > 70%) was detected among the topologies obtained via separate phylogenetic analyses. The parsimony analysis of the alignment found 1205 trees of 291 steps (CI = 0.5022, HI = 0.1475, RI = 0.4785, RC = 0.3785). The best RA×ML tree with a final likelihood value of –44,572.924927 is presented. The matrix had 1095 distinct alignment patterns, with 5.15% undetermined characters or gaps. Estimated base frequencies were as follows: A = 0.114712, C = 0.191626, G = 0.180634, T = 0.213028; substitution rates AC = 1.007806, AG= 1.154719, AT = 1.290447, CG = 1.045887, CT = 4.696475, GT = 1.000000; and gamma distribution shape parameter α= 0.002898. In the Bayesian analysis, the standard deviation between the chains stabilized at 0.00002 after 3 million generations. No significant changes in tree topology trace or cumulative split frequencies of selected nodes were observed after approximately 0.25 million generations, which were discarded as 25% burn-in.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny based on the nrITS + LSU sequence data. Maximum parsimony and Bayesian analyses recovered identical topologies concerning the relationships among the main clades of the Tarzetta. For each node, the following values are provided: maximum parsimony bootstrap (%)/maximum likelihood bootstrap (%)/ and posterior confidence (p-value). The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide substitutions per site. The new species of Tarzetta are shown in bold.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny based on the nrITS + LSU sequence data. Maximum parsimony and Bayesian analyses recovered identical topologies concerning the relationships among the main clades of the Tarzetta. For each node, the following values are provided: maximum parsimony bootstrap (%)/maximum likelihood bootstrap (%)/ and posterior confidence (p-value). The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide substitutions per site. The new species of Tarzetta are shown in bold.

3.2. Taxonomy

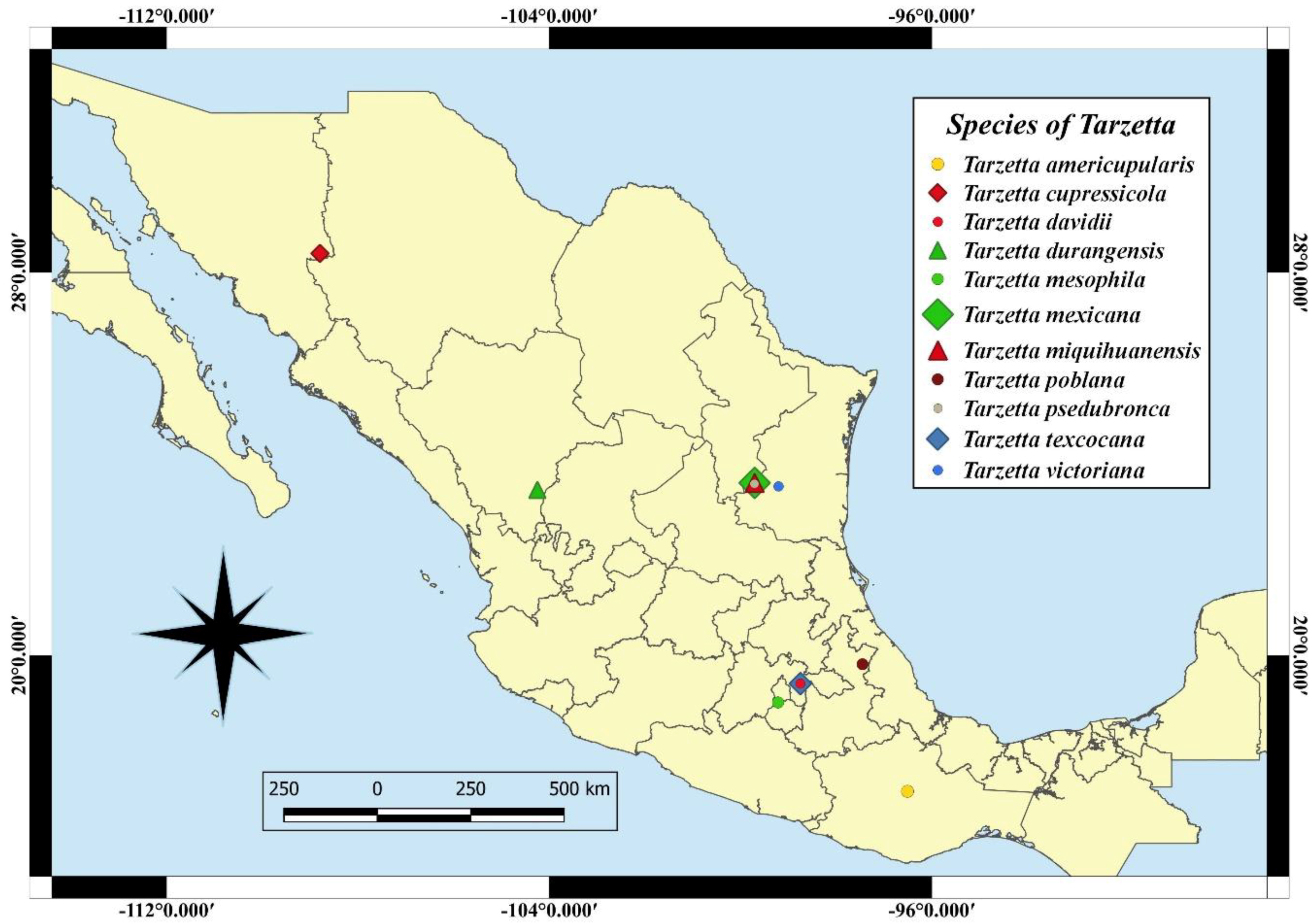

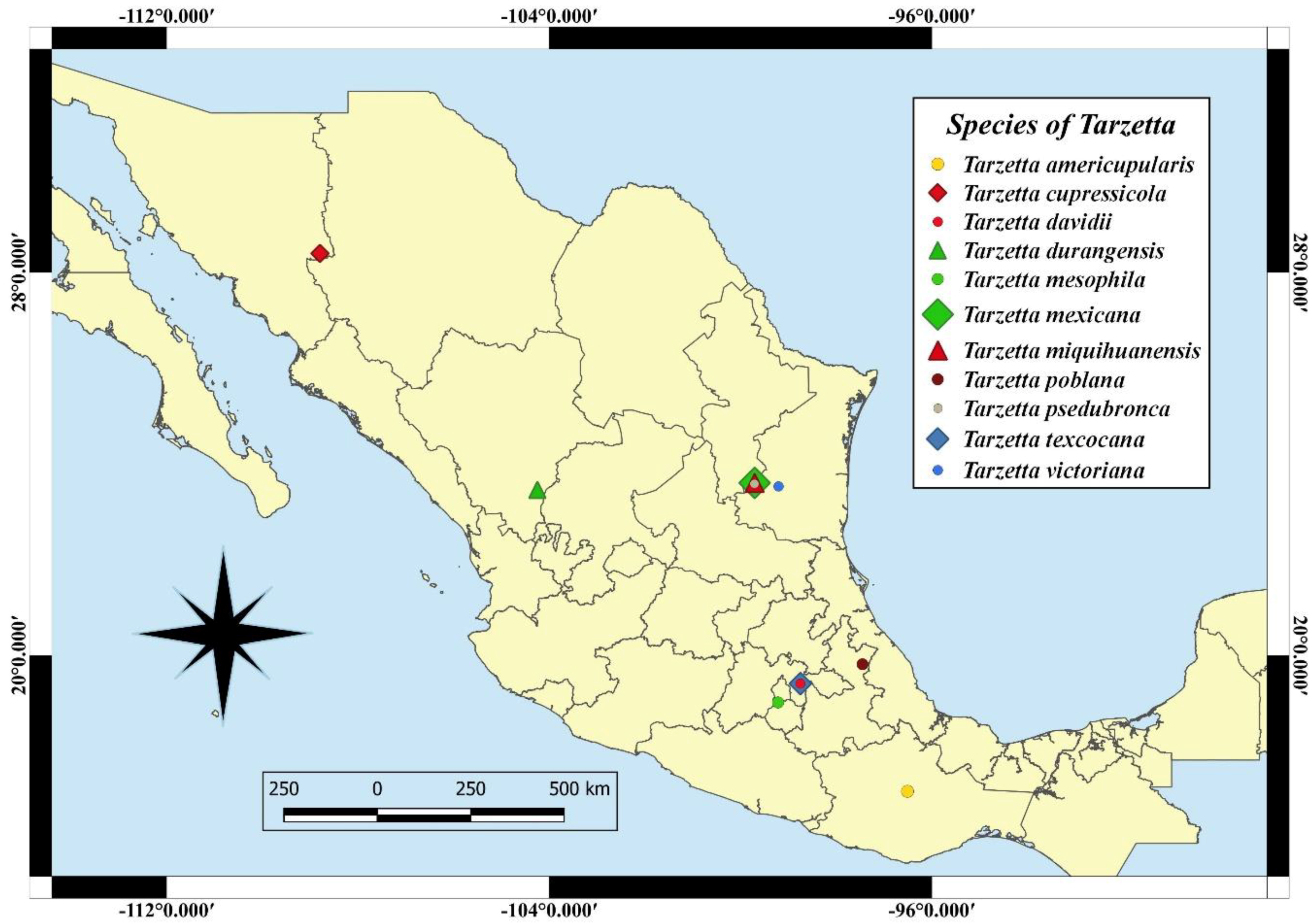

Eleven species of the genus Tarzetta are described as a new species, and they are based on morphological, ecological, and molecular characteristics. Furthermore, a map of Mexico shows the distribution of the type species (Figure 2); a comparative table of Mexican species and some American and European species with morphological and ecological characteristics (vegetation type and ectomycorrizal host) (Table 2) and the taxonomic key of the Mexican species of Tarzetta are included.

Figure 2.

Localities of the type species in Mexico.

Figure 2.

Localities of the type species in Mexico.

Tarzetta americupularis Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez, R. Valenz. & Raymundo, sp. nov. (Figure 3, Figure 14A and Figure 15A)

Mycobank: #851432

Diagnosis: Apothecia 4–8 mm diameter, hymenium pale orange, margin crenate, granulate to prunoise; ascospores (15–) 17–25 (–26) × 9–13 (–14) µm, ellipsoid to oblong, grown under Quercus spp.

Type: MEXICO: Oaxaca state. Santa Catarina Lachatao municipality, Santa Martha Latuvi, place 3 caminos, La Muralla (17°09′43″ N, 96°30′35.4″ W), 2700 m asl, 2 September 2011, T. Raymundo 3833 (ENCB, holotype).

GenBank: ITS: PP825384, LSU: PP825427.

Etymology: The epithet refers to the morphological similarity with T. cupularis (L.) Lambotte but occurs on the American Continent.

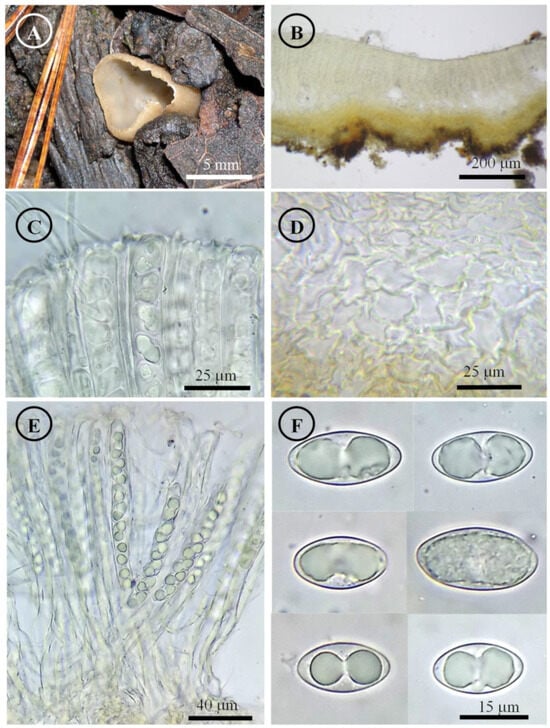

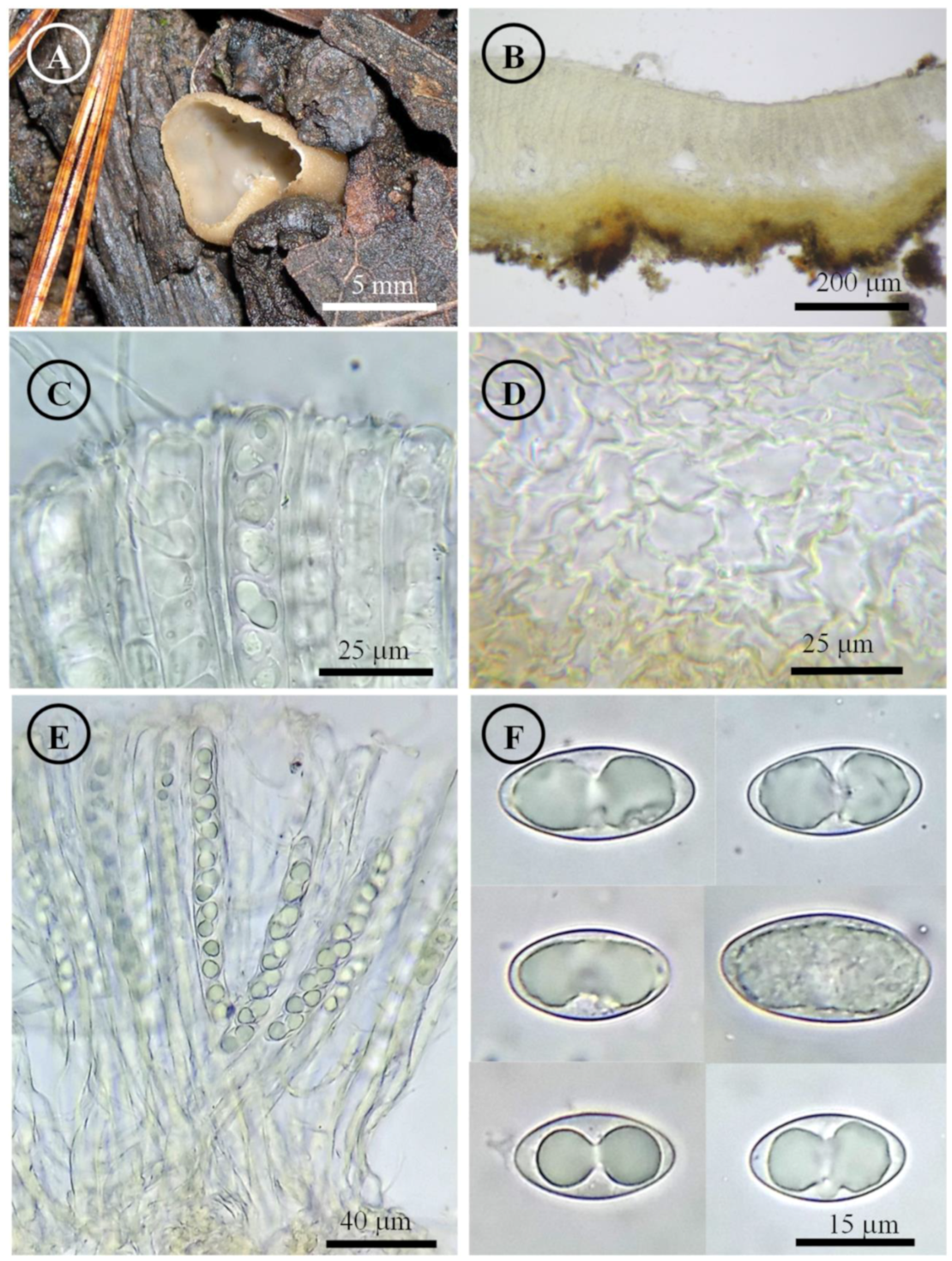

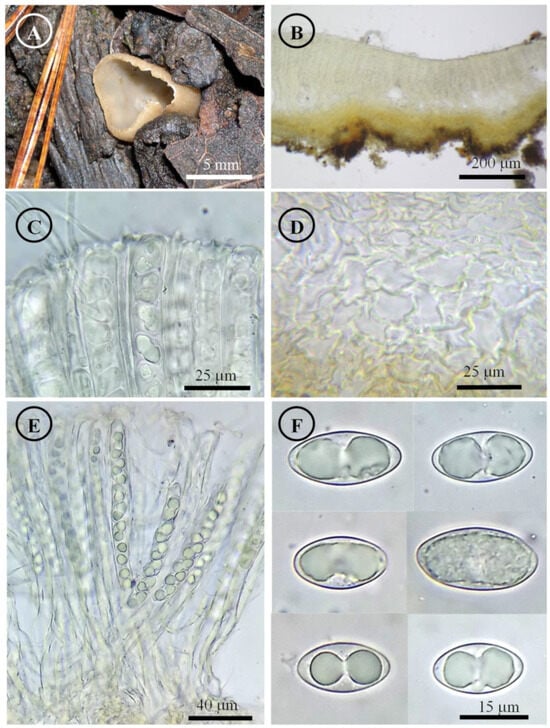

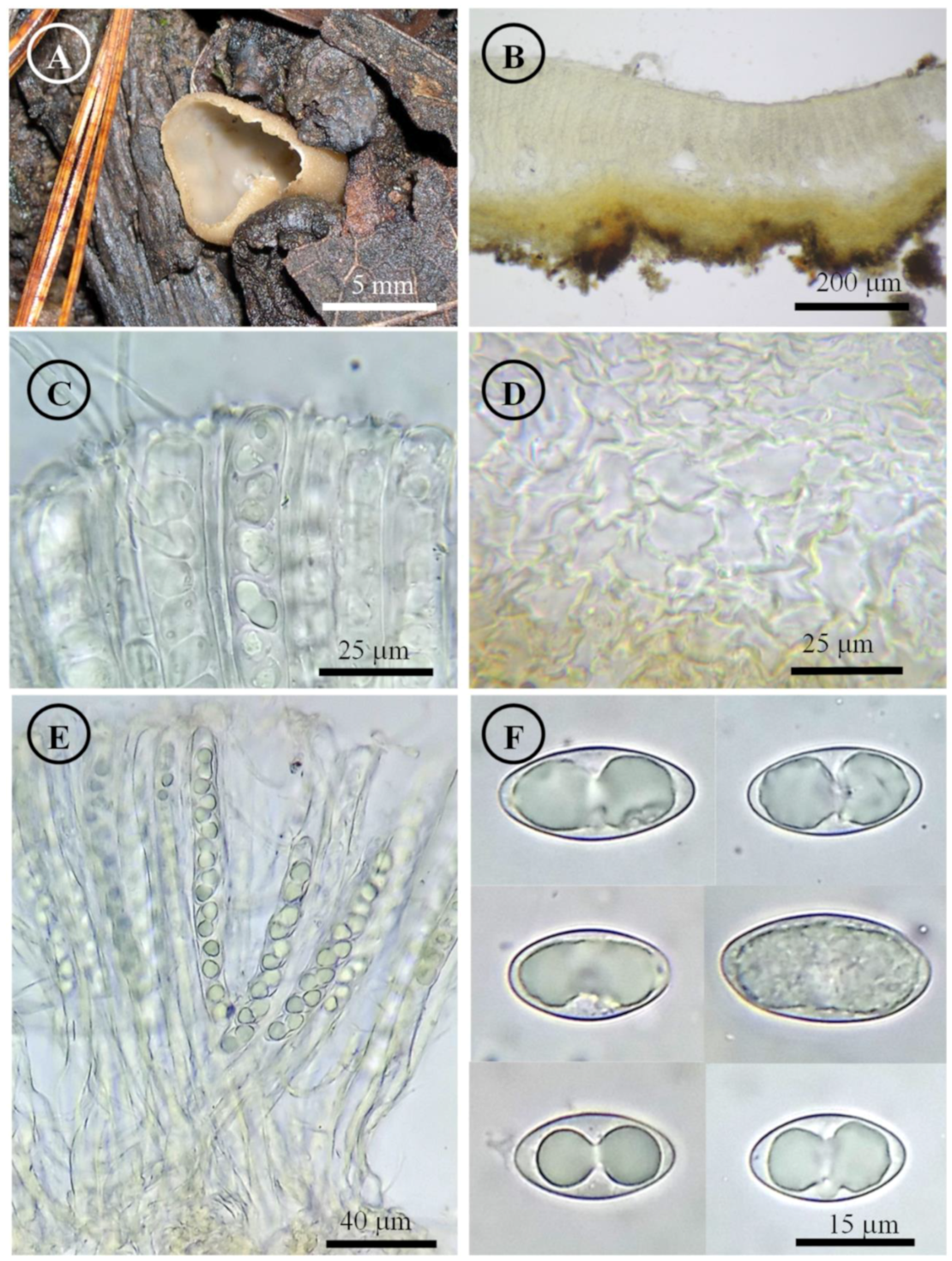

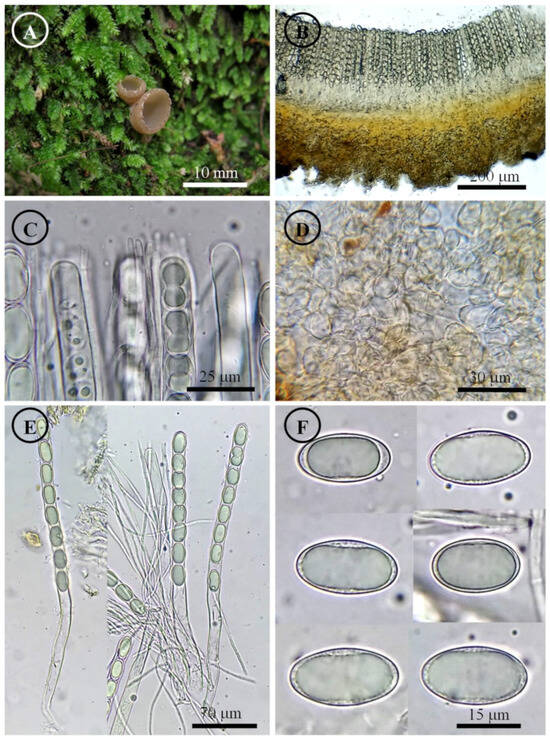

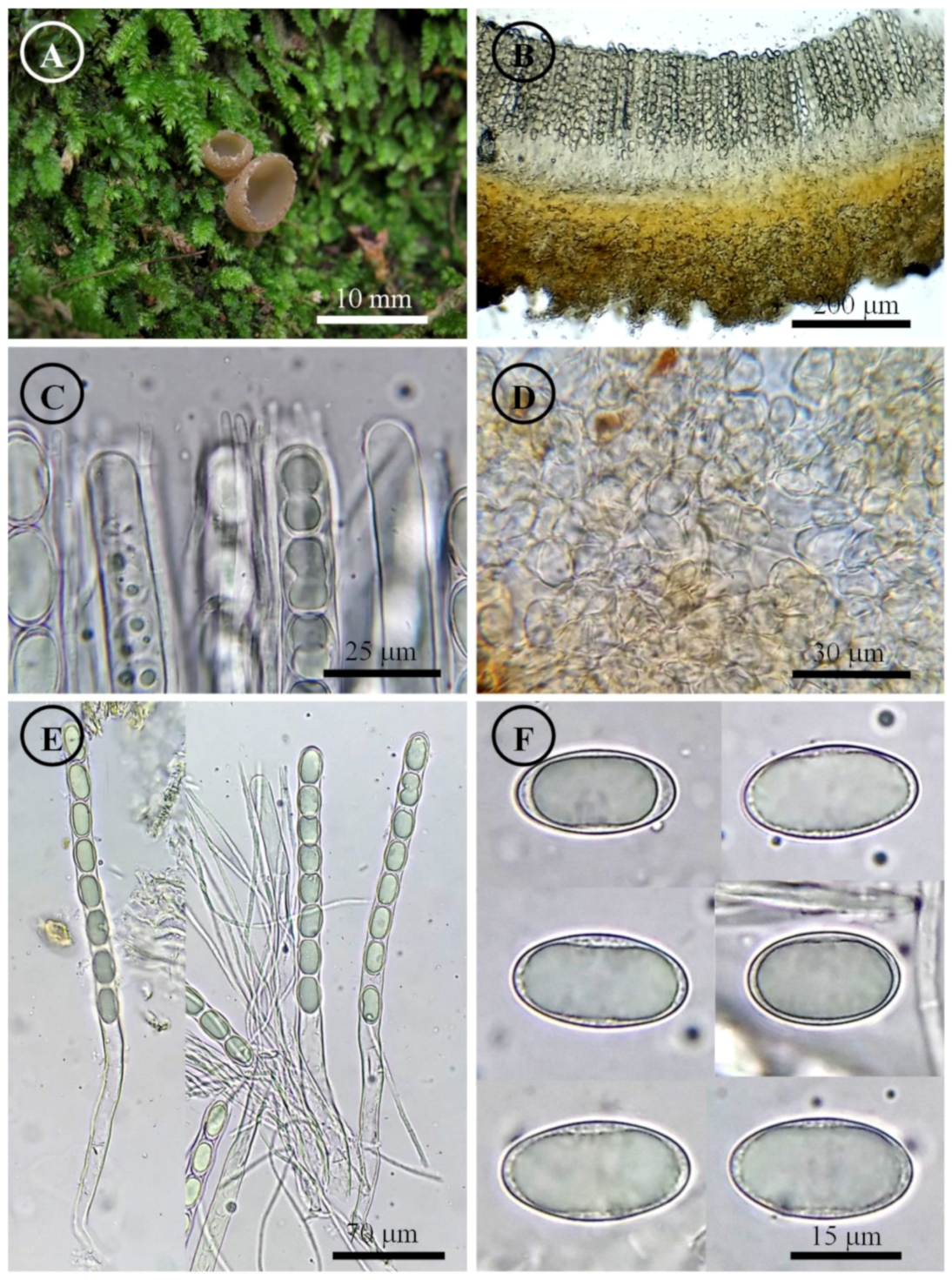

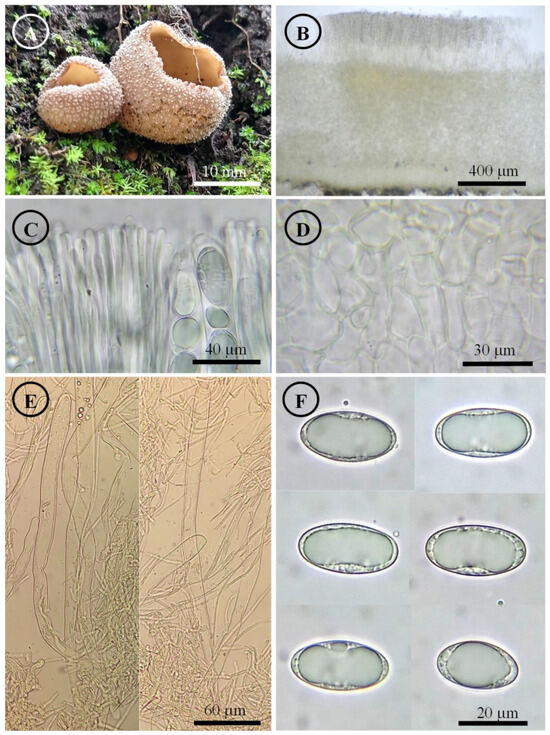

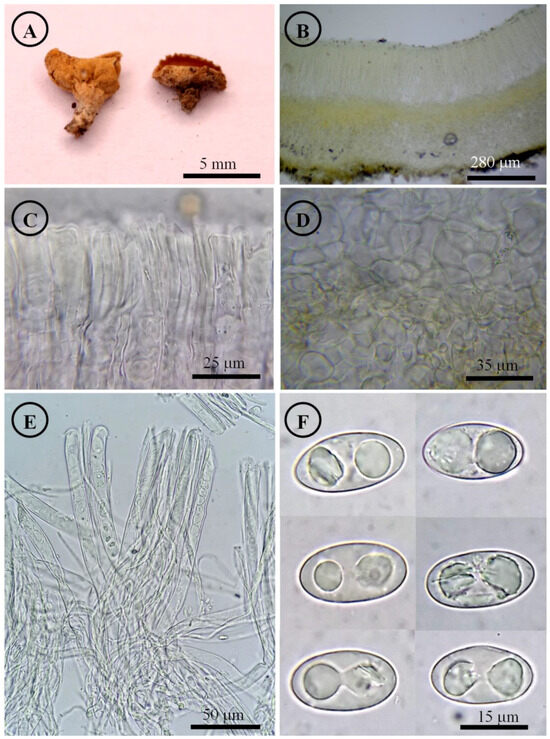

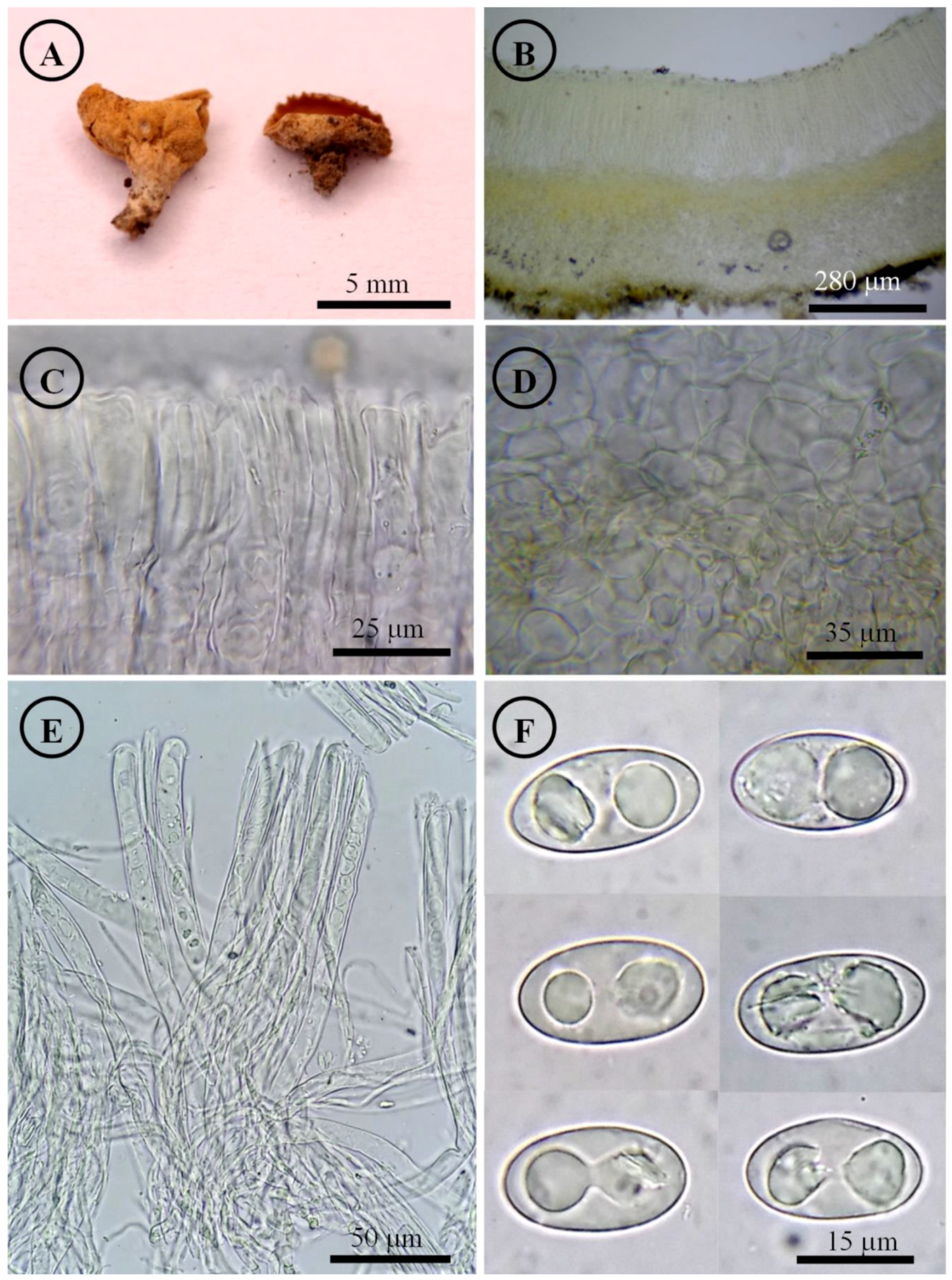

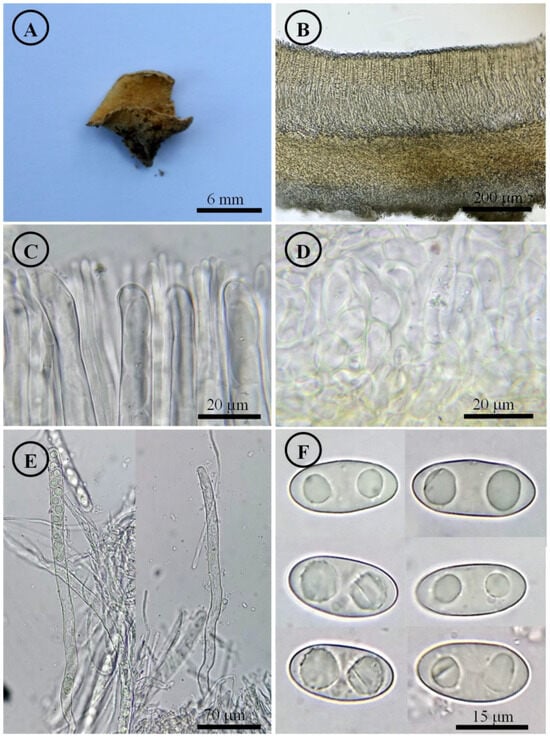

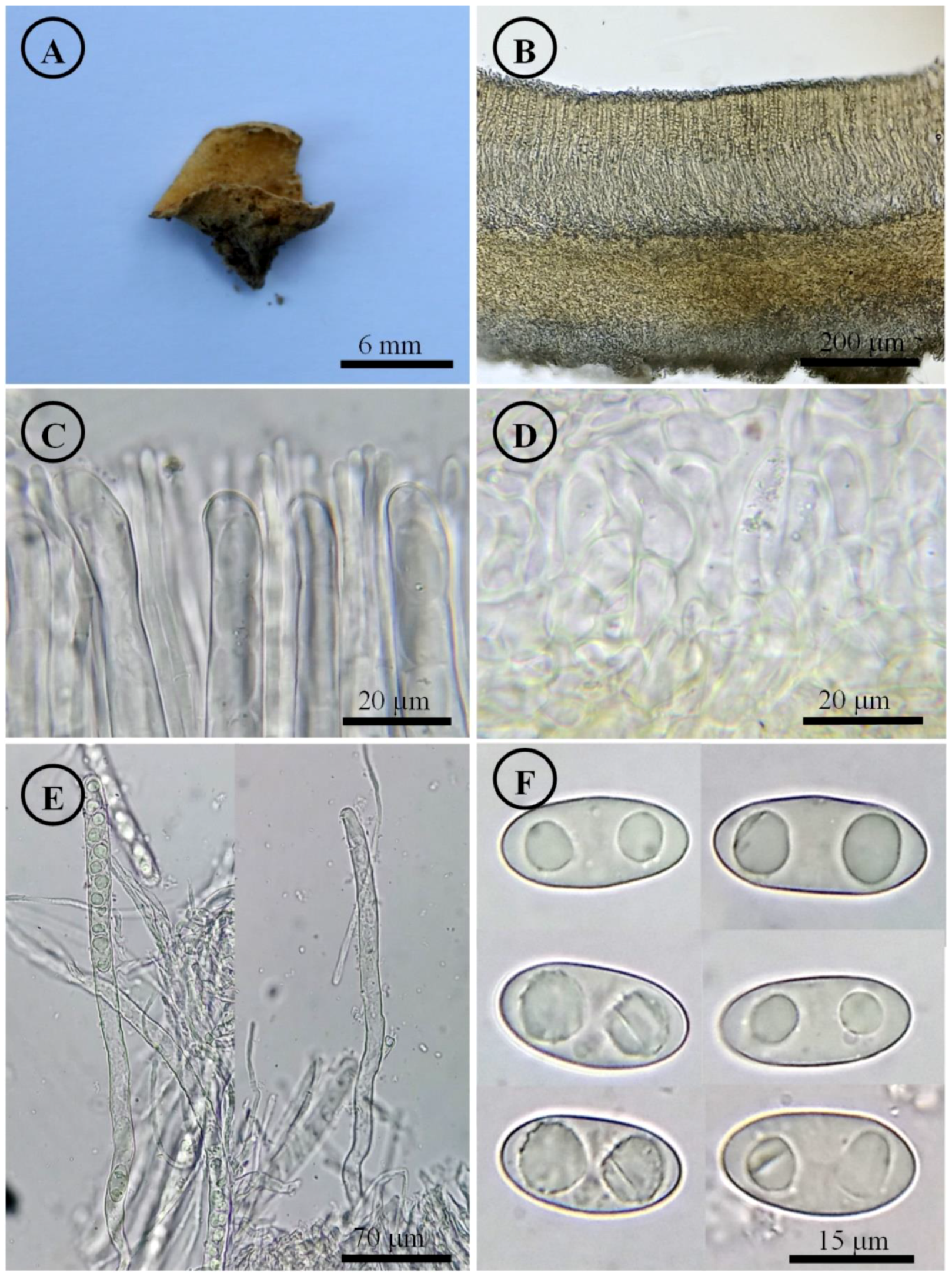

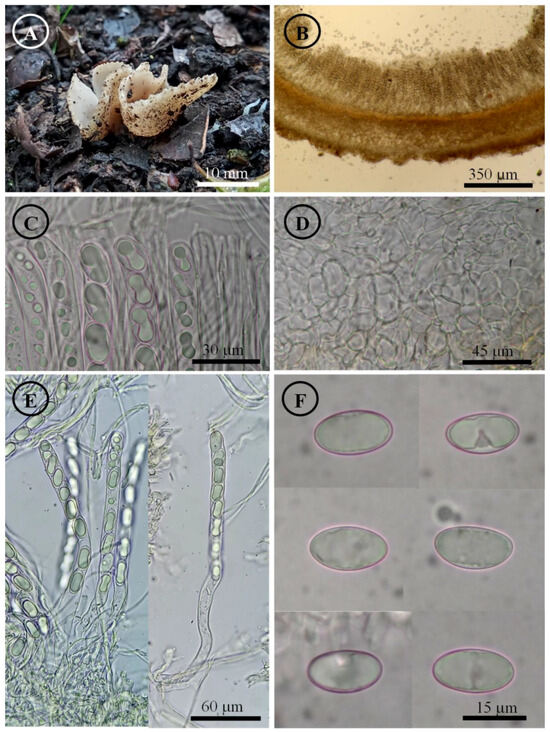

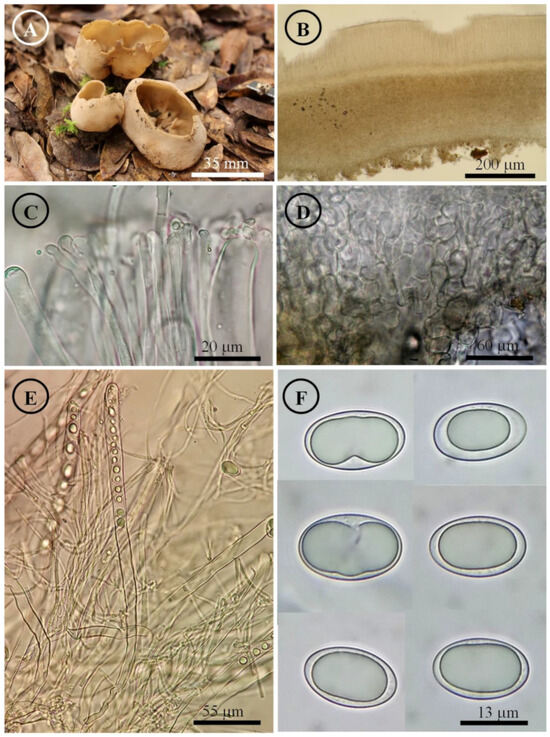

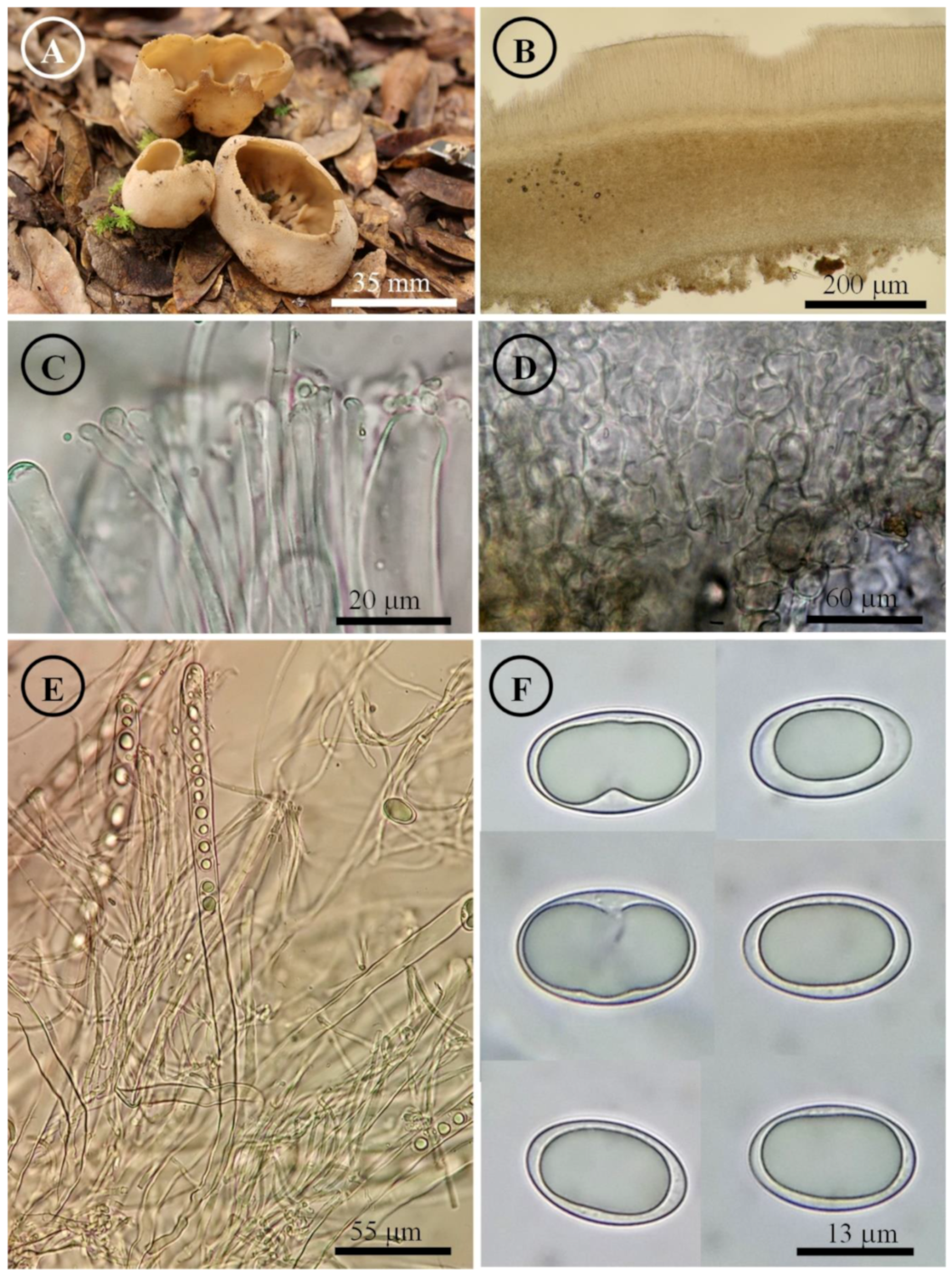

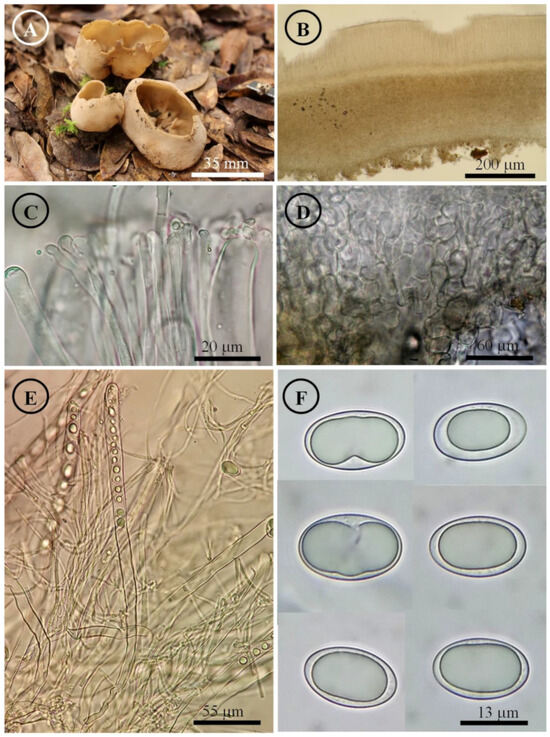

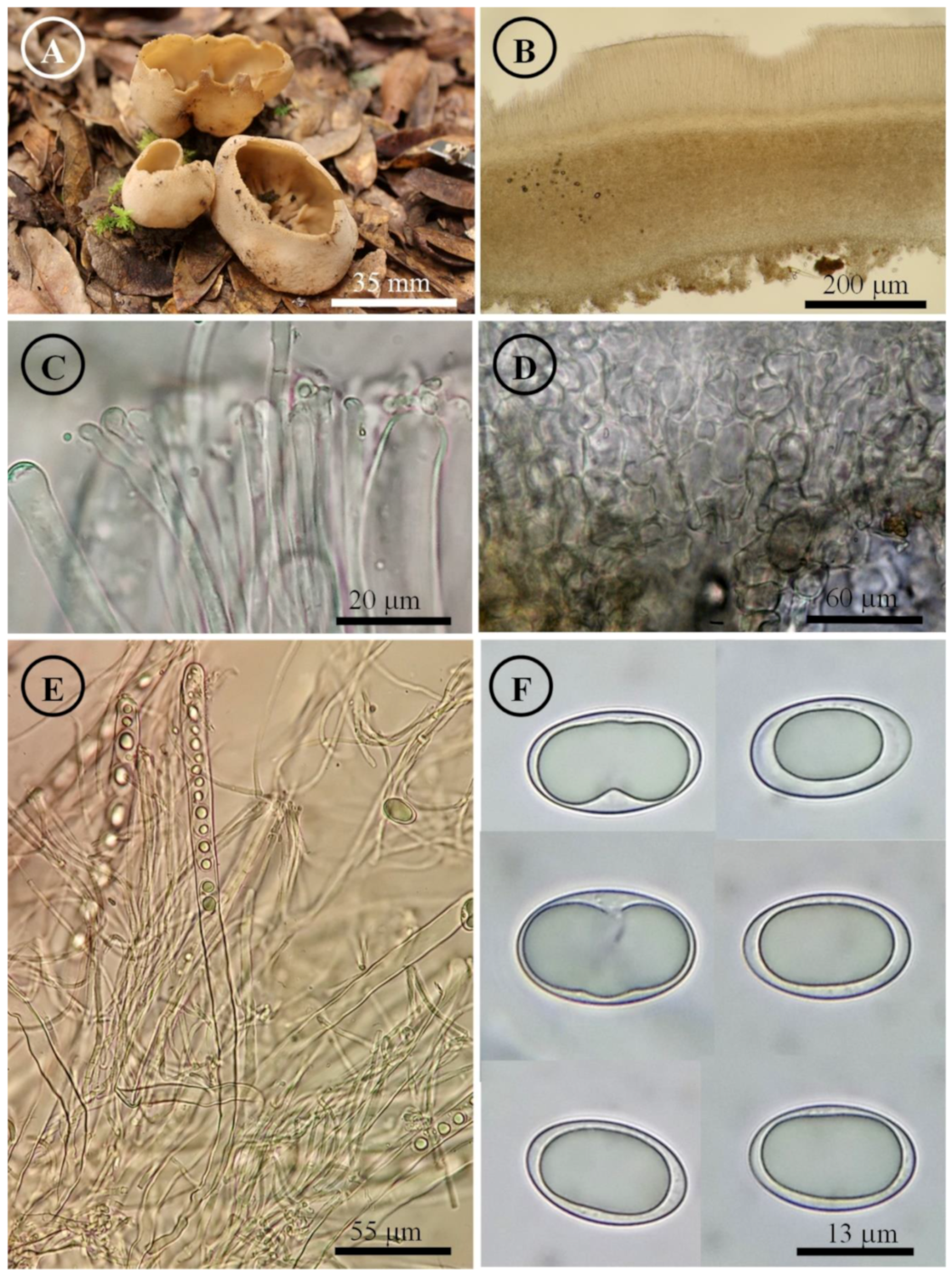

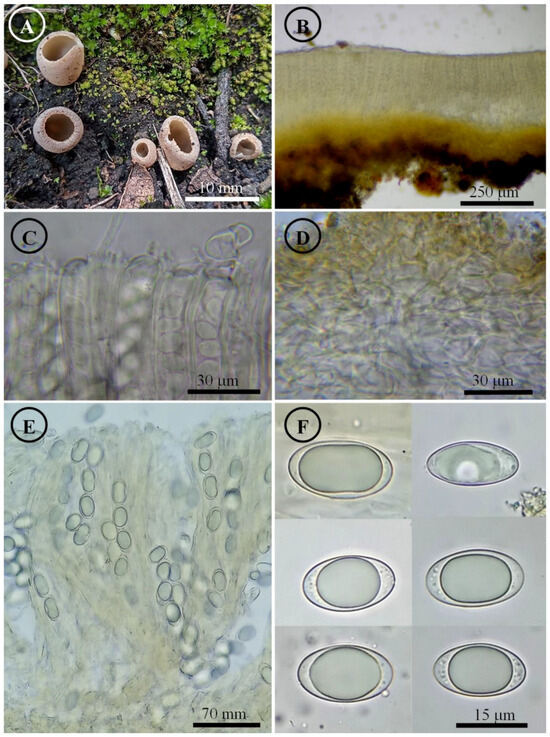

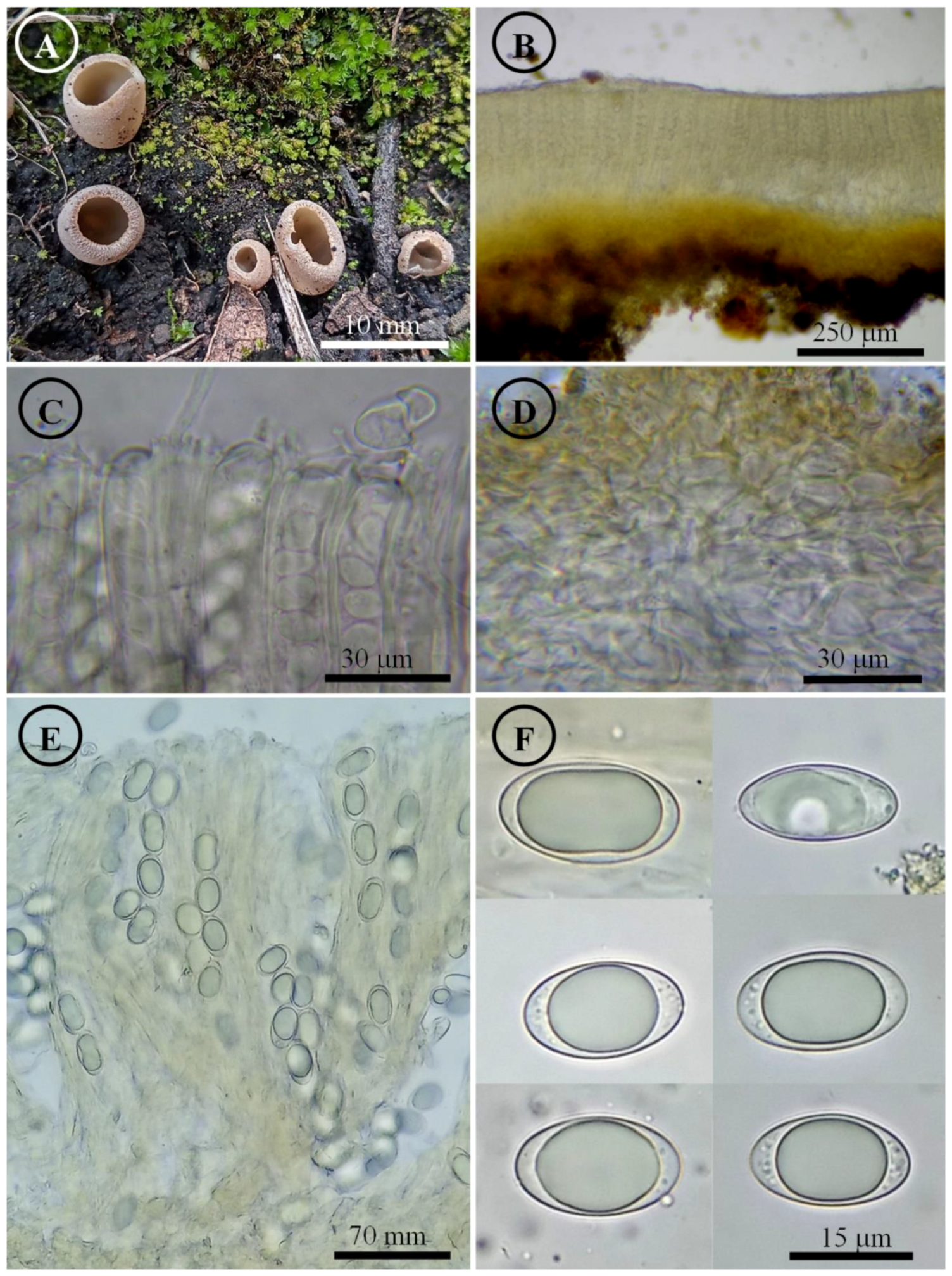

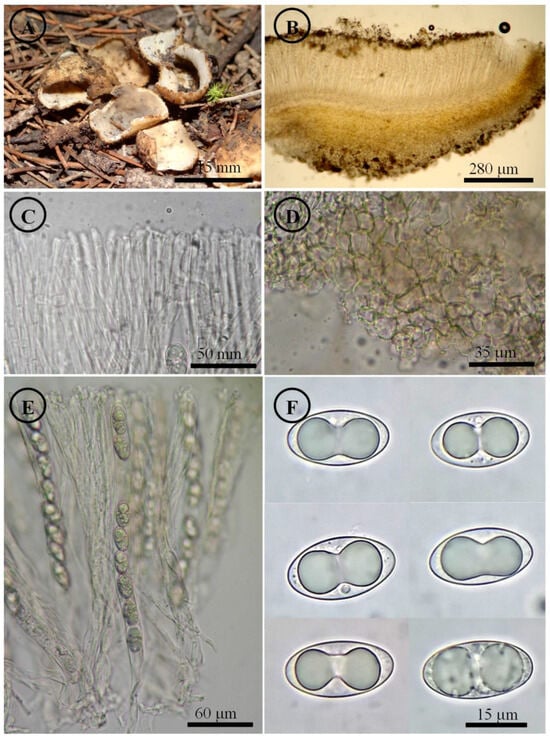

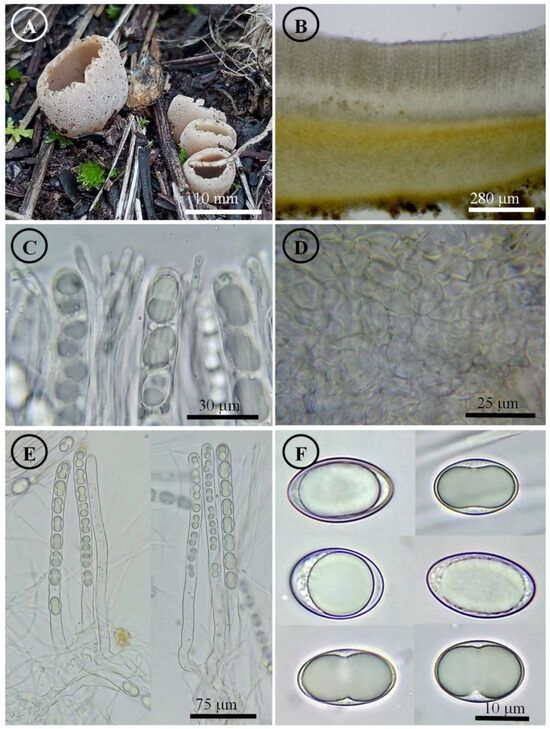

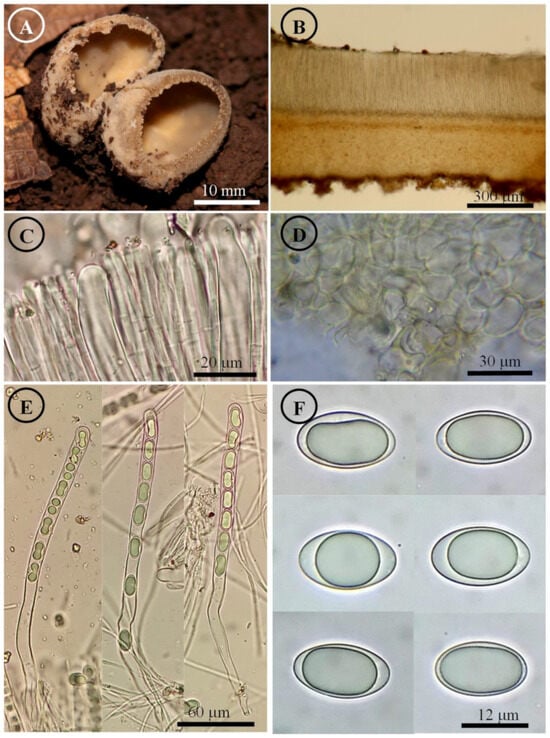

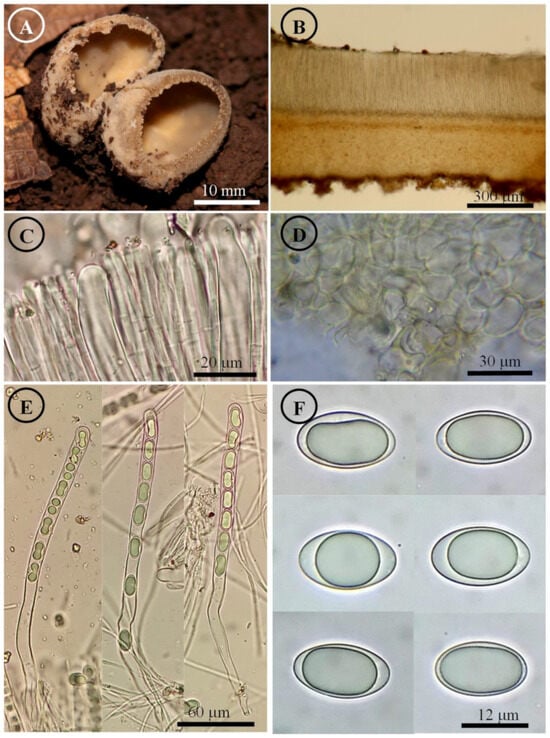

Figure 3.

Tarzetta americupularis. (A) Apothecium; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Figure 3.

Tarzetta americupularis. (A) Apothecium; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

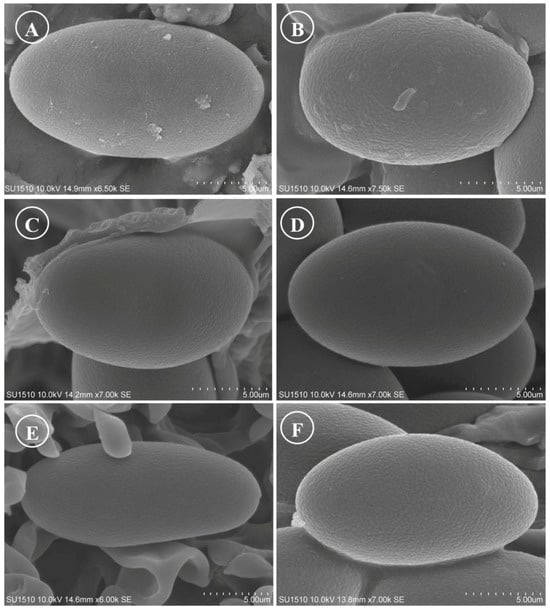

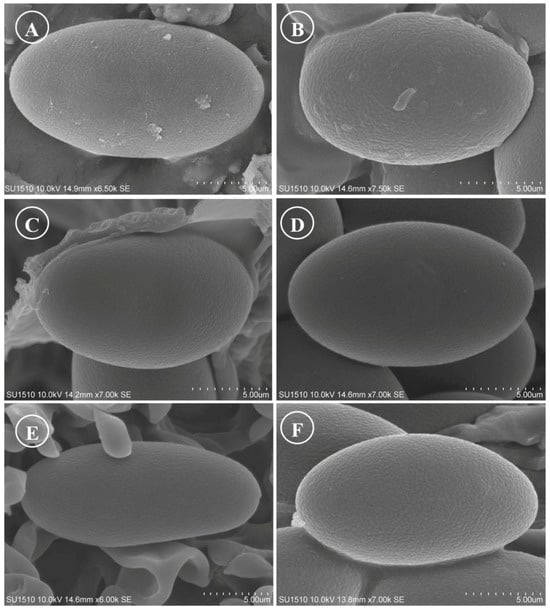

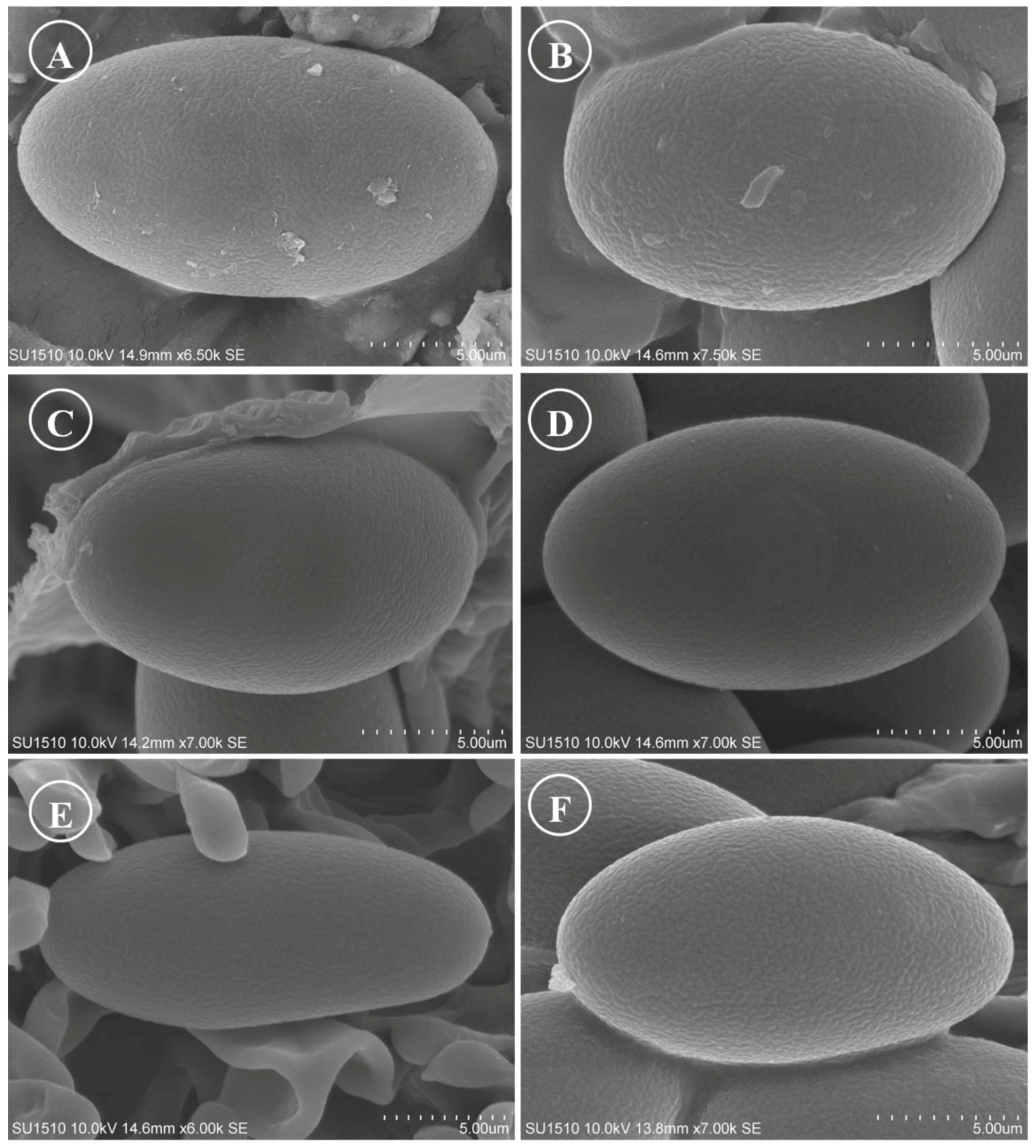

Apothecia 4–8 mm in diameter, cupuliform, solitary to scattered, sessile, hymenium pale orange (5A3), margin crenate that tears at maturity, external surface greyish orange (5B4), granulate to pruinose, asperulate. Ectal excipulum 30–90 µm thick, textura angularis with cells 12–27 × 9–18 µm, hyaline, thin-walled. Medullary excipulum 35–90 µm thick, textura intricata with hyphae 3–6 µm in diameter, hyaline. Subhymenium 8–20 µm thick. Hymenium 200–315 µm thick. Paraphyses 2–4 µm in diameter, filiform, septate, with rounded to abrupt apex. Asci 190–310 (–325) × 11–15 µm, cylindrical, 8-spored, hyaline, inamyloid. Ascospores (15–) 17–25 (–26) × 9–13 (–14) µm [x = 20.5 × 11.5 µm, n = 63], Q = (1.5–) 1.6–2.2 (–2.3) Qm = 1.9, ellipsoid to oblong, hyaline, 1–2 guttules, smooth on OM, very finely rugose on SEM.

Habit: On soil, in Pinus-Quercus and coniferous forest.

Distribution: MEXICO. Mexico City, Mexico State, and Oaxaca.

Material examined: Mexico, Mexico City, Álvaro Obregón town hall, Desierto de los Leones, 1 September 1972, E. García 310 (ENCB, paratype; ITS: PP825385, LSU: PP825428). Mexico State, Donato Guerra municipality, El Capulín, 25 September 1983, R.E. Santillán 487 (ENCB). Huixquilucan municipality, Santa Cruz, 23 September 2023, T. Raymundo 9367 (ENCB). Jilotepec municipality, El Cuzda hill, México-Querétaro highway, 28 August 1983, L. Guzmán-Dávalos 753 (ENCB). Tlalmanalco municipality, road Tlalmanalco-San Rafael, 25 September 1955, G. Guzmán 336-D (ENCB). Oaxaca state, Santa Catarina Ixtepeji municipality, Centro Ecoturistico La Cumbre, 7 September 2023, M. Sánchez 3278 (ITCV), 3281 (ITCV), 3285 (ITCV), 3288 (ITCV), 3294 (ITCV).

Notes: This species is characterized by forming apothecia 4–8 mm in diameter and ellipsoid to oblong ascospores [Q = (1.5–) 1.6–2.2 (–2.3) µm]. Microscopically, it is similar to T. cupularis, but T. americupularis has wider ascospores 21–25 (–26) × (–12.5) 13–15 µm; furthermore, phylogenetically it is found in different clades [7]. T. mexicana shares a similar distribution but differs for its smaller ascospores [(18–) 19–22 × 10–12 µm]. On the other hand, T. poblana has a distribution towards the central and east of Mexico (Mexico State, Puebla and Tlaxcala) and forms smaller apothecia (2–5 mm diameter), asci (170–205 × 13–15 µm), and ascospores (16–22 × 9–12 µm). T. texcocana differs in its ascospore size [17–21 (–22) × 11–14 (–15) µm] and shape (broadly ellipsoid).

Tarzetta cupressicola Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez, Esqueda & Raymundo, sp. nov. (Figure 4, Figure 14B and Figure 15B)

Mycobank: #851433

Diagnosis: Apothecia 5–8 mm diameter, hymenium salmon color, margin serrate to crenate, pruinose to fine-grained; ascospores 18–22 (–23) × 11–13 µm, ellipsoid, grown under Cupressus lusitanica.

Type: MEXICO. Sonora state. Yecora municipality, Los Pilares (28°23′48.9″ N, 108°47′43.6″ W), 1297 m asl, 18 September 2021, A. Gutiérrez 115 (UES10645, holotype; ENCB, isotype).

GenBank: ITS: PP825386, LSU: PP825429.

Etymology: The epithet refers to the ascocarp collected under the canopy of Cupressus.

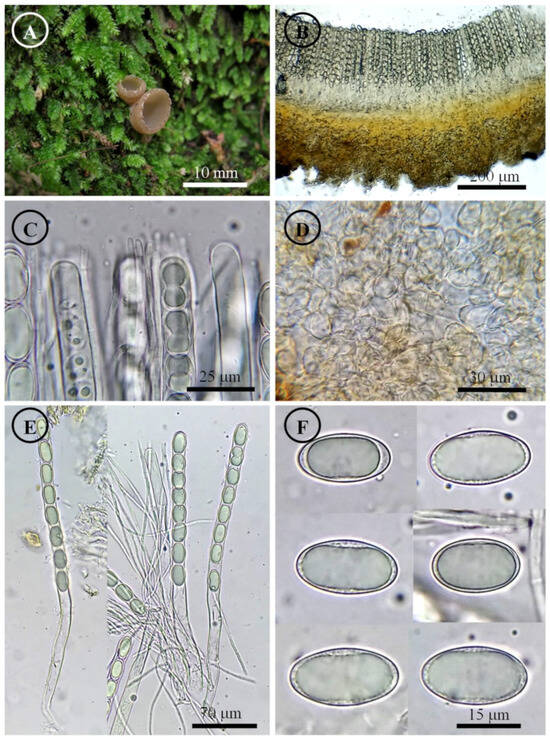

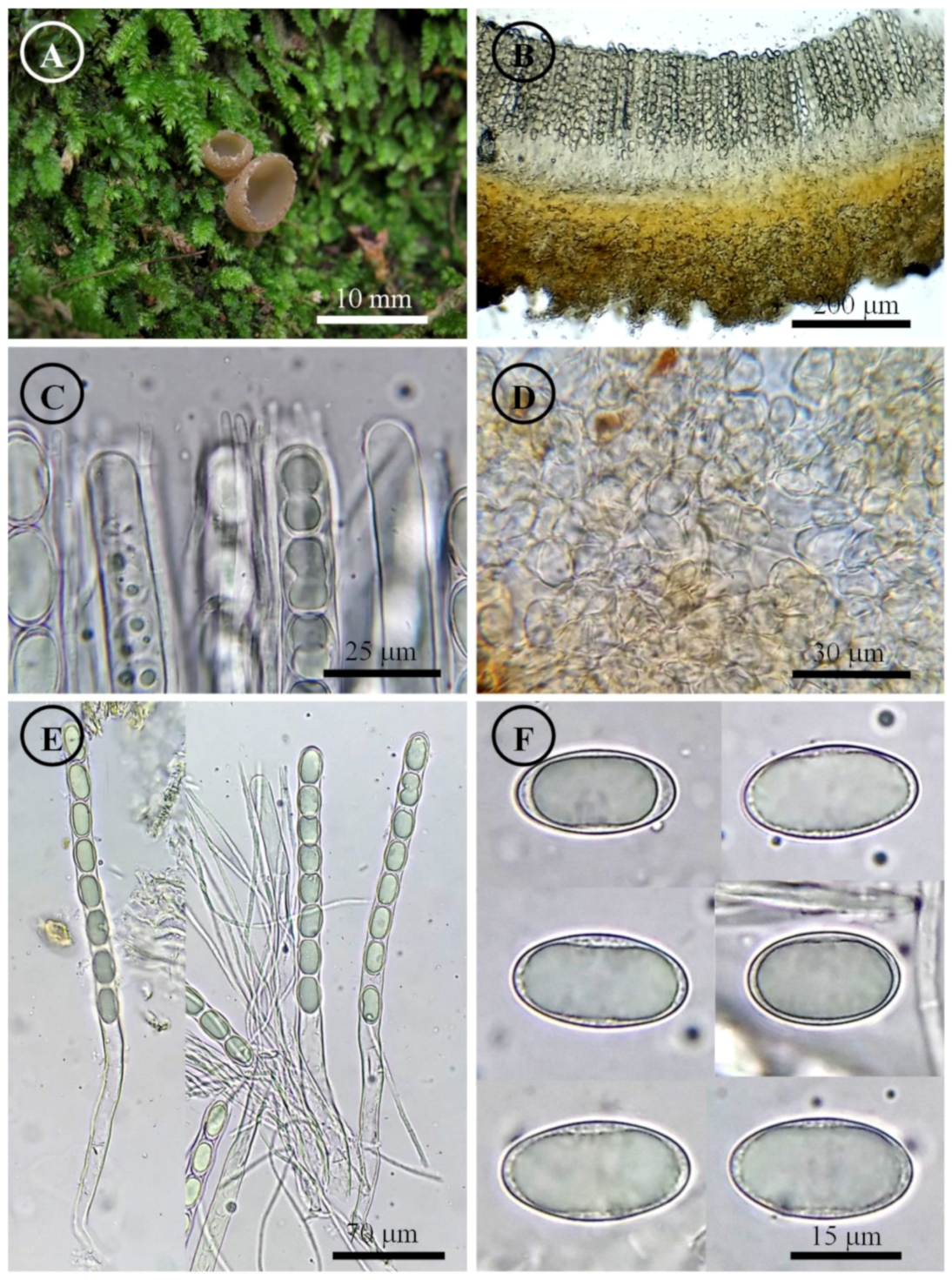

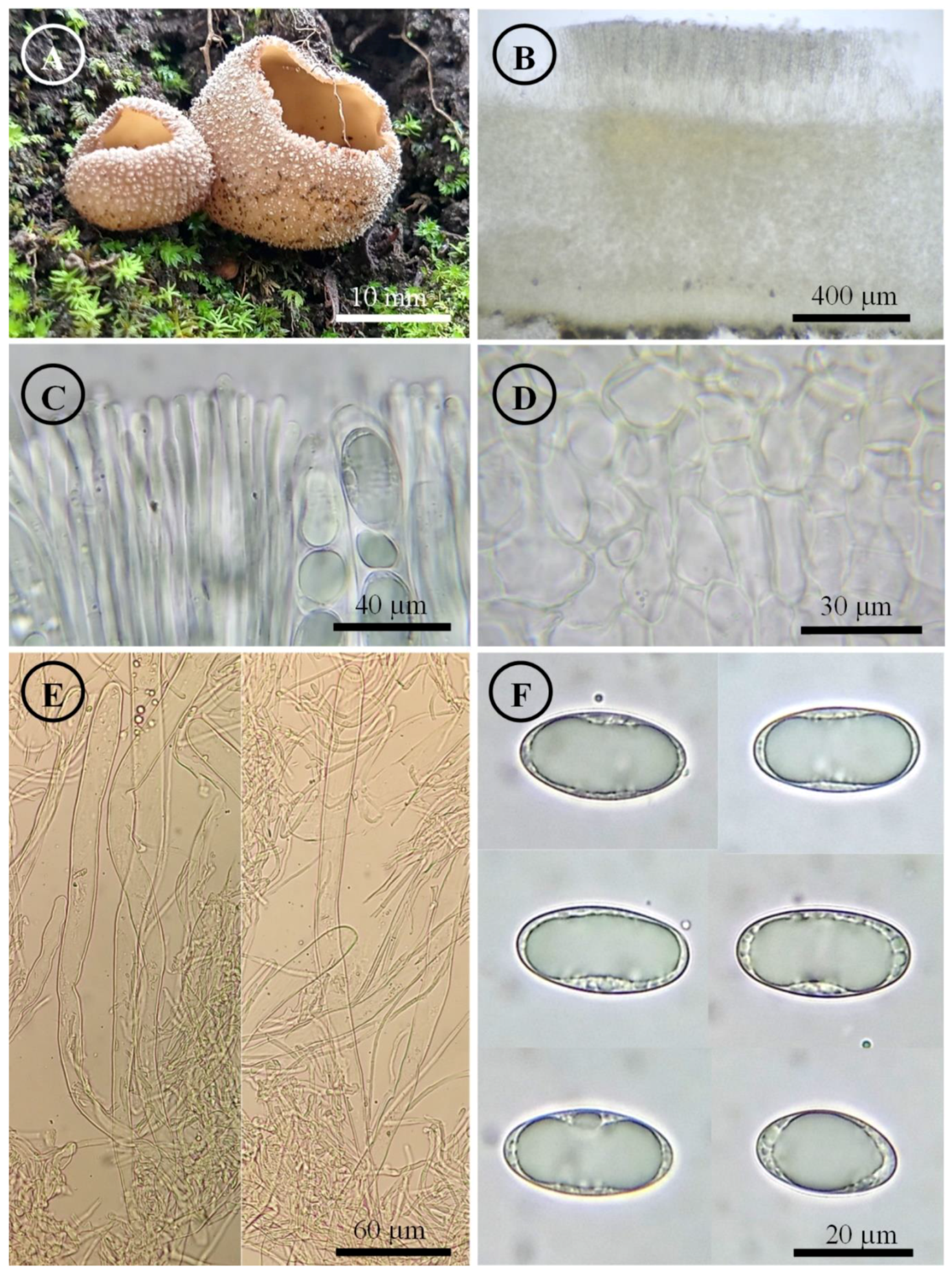

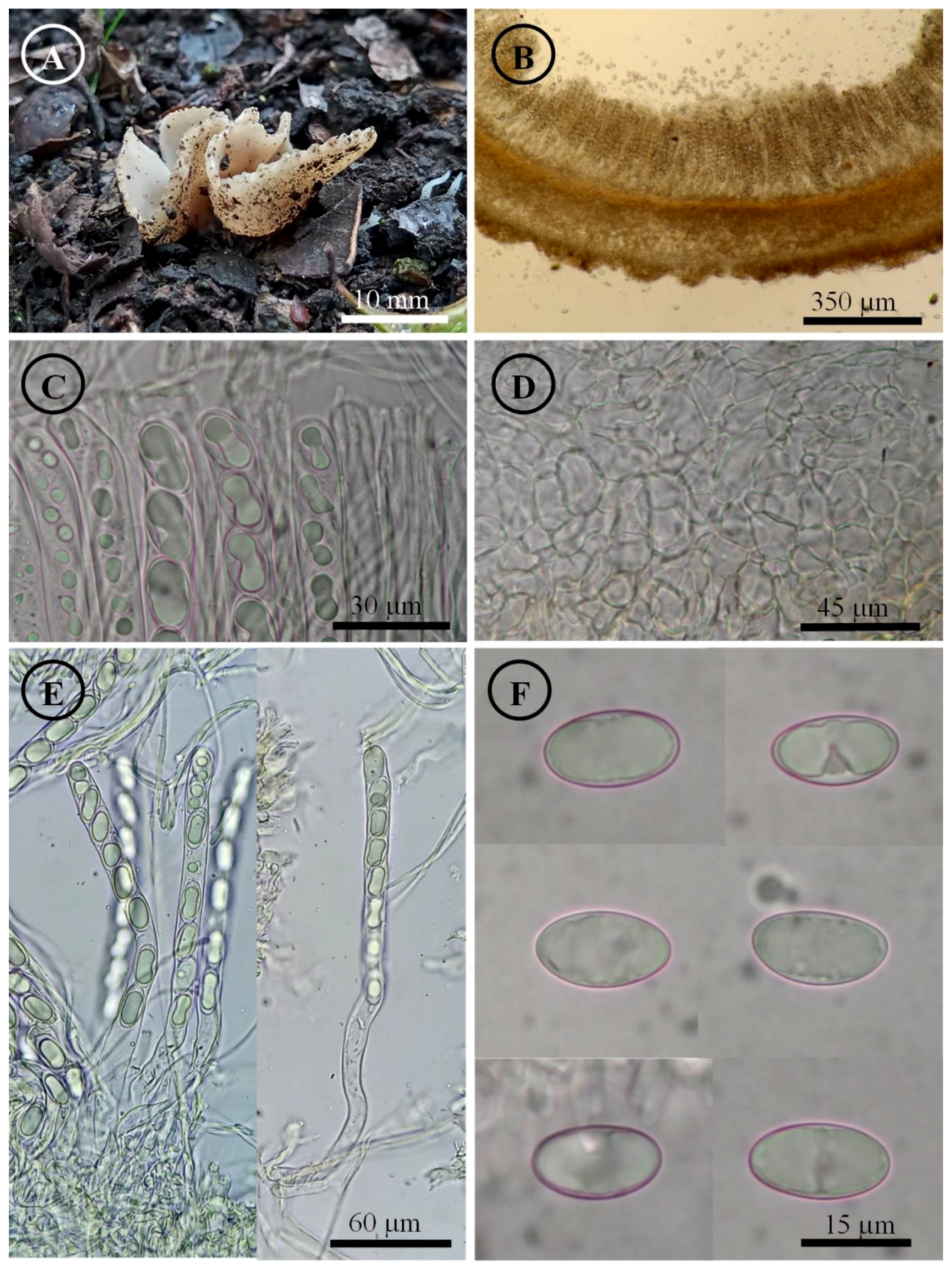

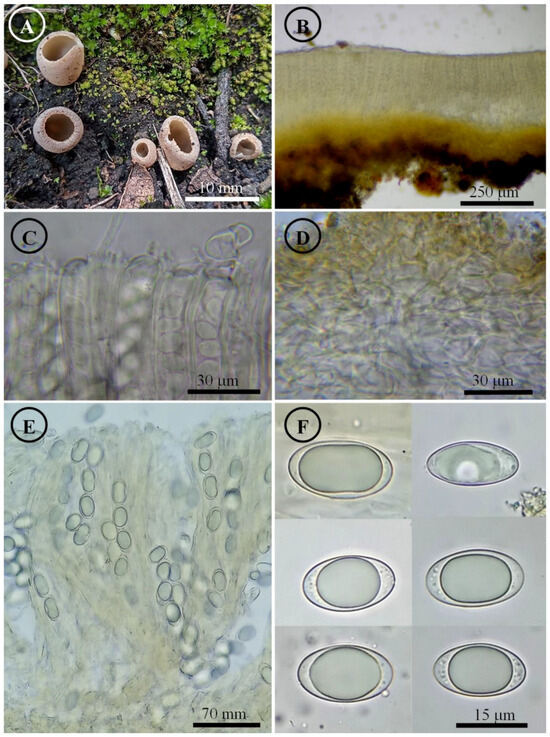

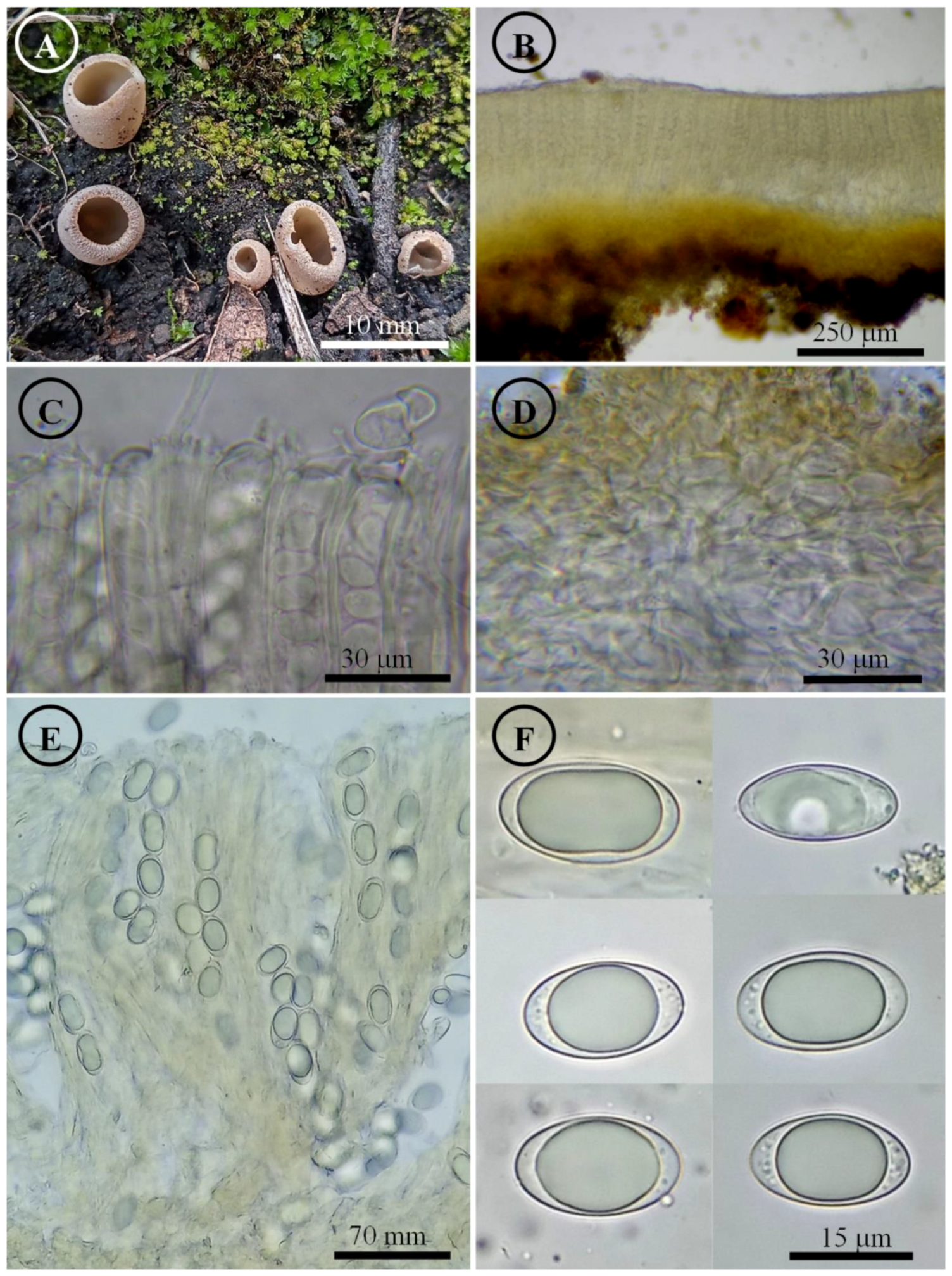

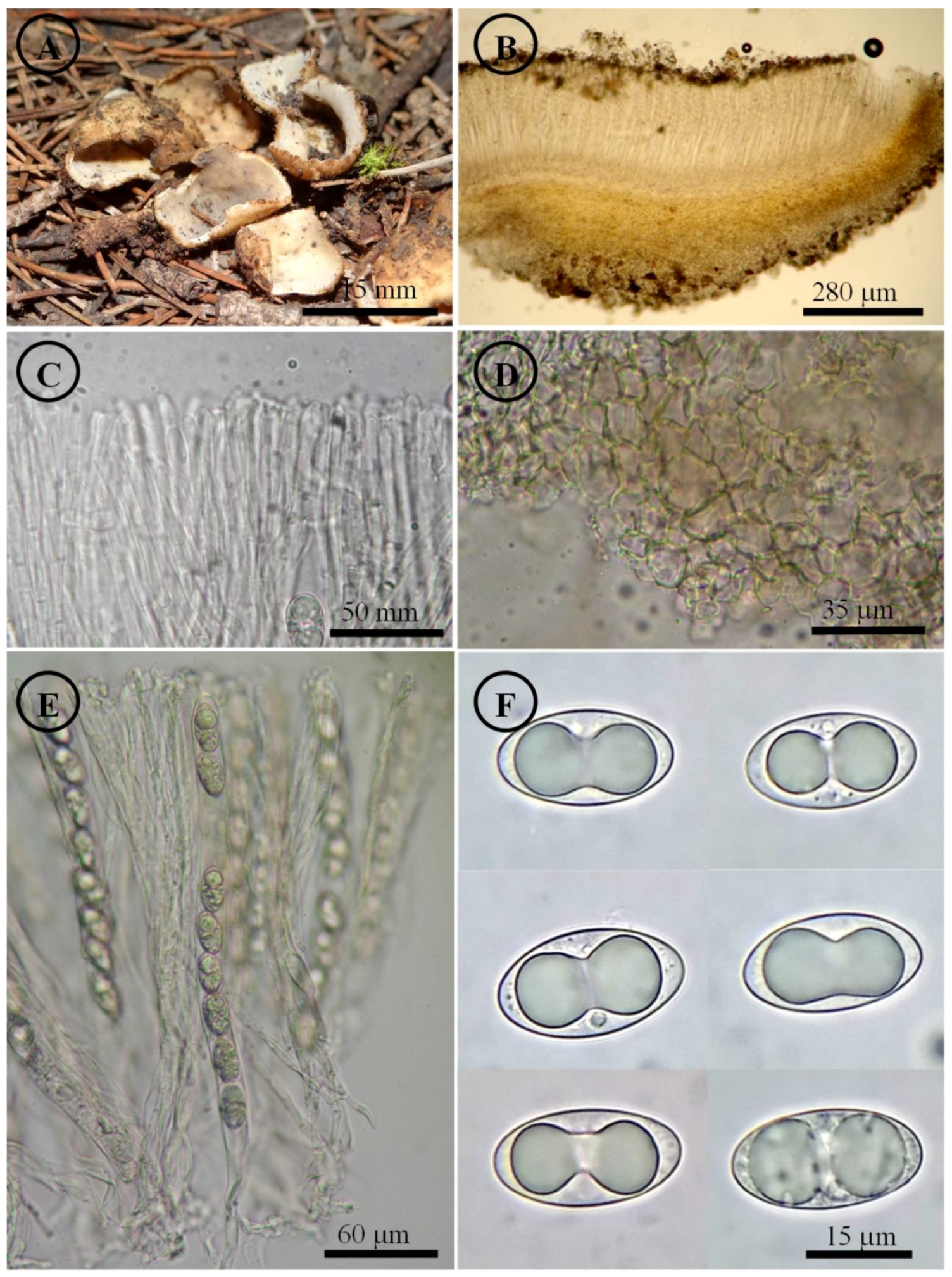

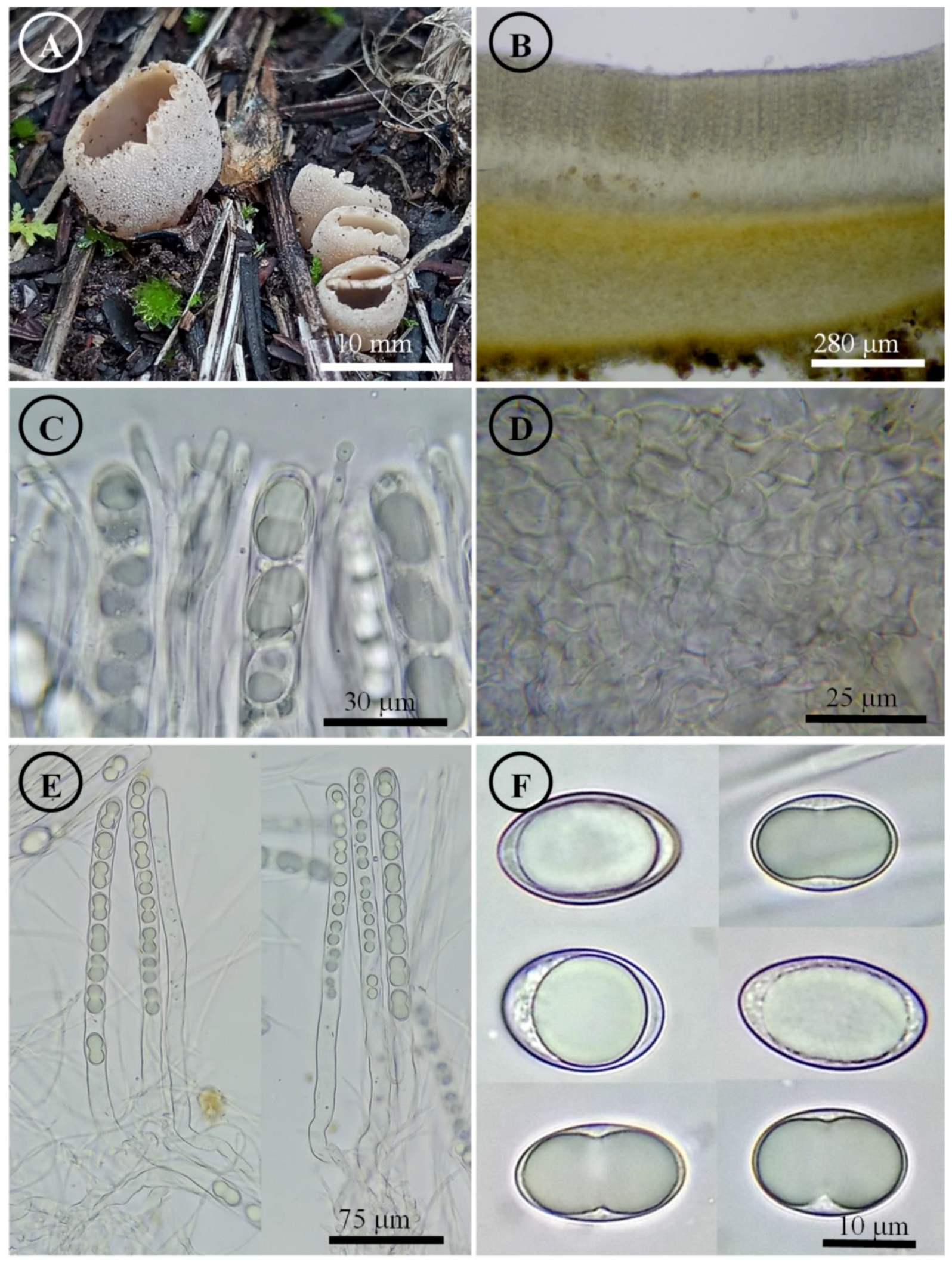

Apothecia 5–8 mm in diameter, cupuliform, solitary, sessile, hymenium salmon (6A4), margin serrate to crenate, external surface pale orange (6A3), pruinose to fine-grained. Ectal excipulum 100–135 µm thick, textura globulosa/angularis with cells 6–19 × 5–13 µm, subhyaline, thin-walled, ectal hyphae 25–70 × 5–6 µm with 1–3 septa, hyaline. Medullary excipulum 55–85 µm thick, textura intricata with hyphae 3–6 µm in diameter, subhyaline. Subhymenium undifferentiated. Hymenium 250–280 µm thick. Paraphyses 2–3 µm in diameter with few septa, filiform, apex rounded, bifurcated. Asci 240–290 × 12–14 µm, cylindrical, 8-spored, uniseriate, hyaline, inamyloid. Ascospores 18–22 (–23) × 11–13 µm [x = 20 × 12 µm, n = 69], Q = 1.5–2, Qm = 1.75, ellipsoid, hyaline, 1–2 guttules, smooth on OM, finely rugose on SEM.

Habit: Growing between moss under the canopy of Cupressus lusitanica in mixed forest.

Distribution: MEXICO. It is only known from the type locality.

Material examined: Mexico, Sonora state, Yecora municipality, Los Pilares (28°23′31.5″ N, 108°47′29.8″ W), 1225 m asl, 13 September 2020, D. Madriz 52 (UES10641), 39 (UES10642); loc. cit. 17 September 2021, D. Madriz & A. Preciado 92 (UES10643), 93 (UES10644); loc. cit. (28°23′42.0″ N, 108°47′34.8″ W), 1267 m asl, 18 September 2021, D. Madriz 137 (ENCB, UES10646, paratype; ITS: PP825387, LSU: PP825430), T. Raymundo 8715 (ENCB).

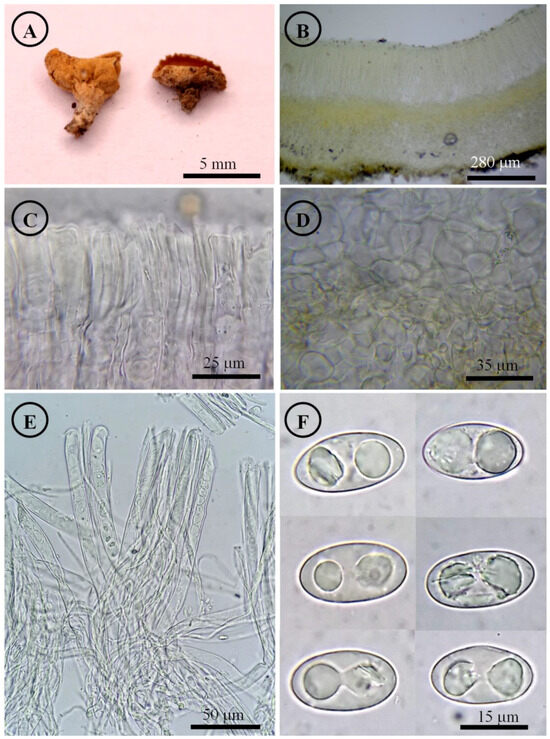

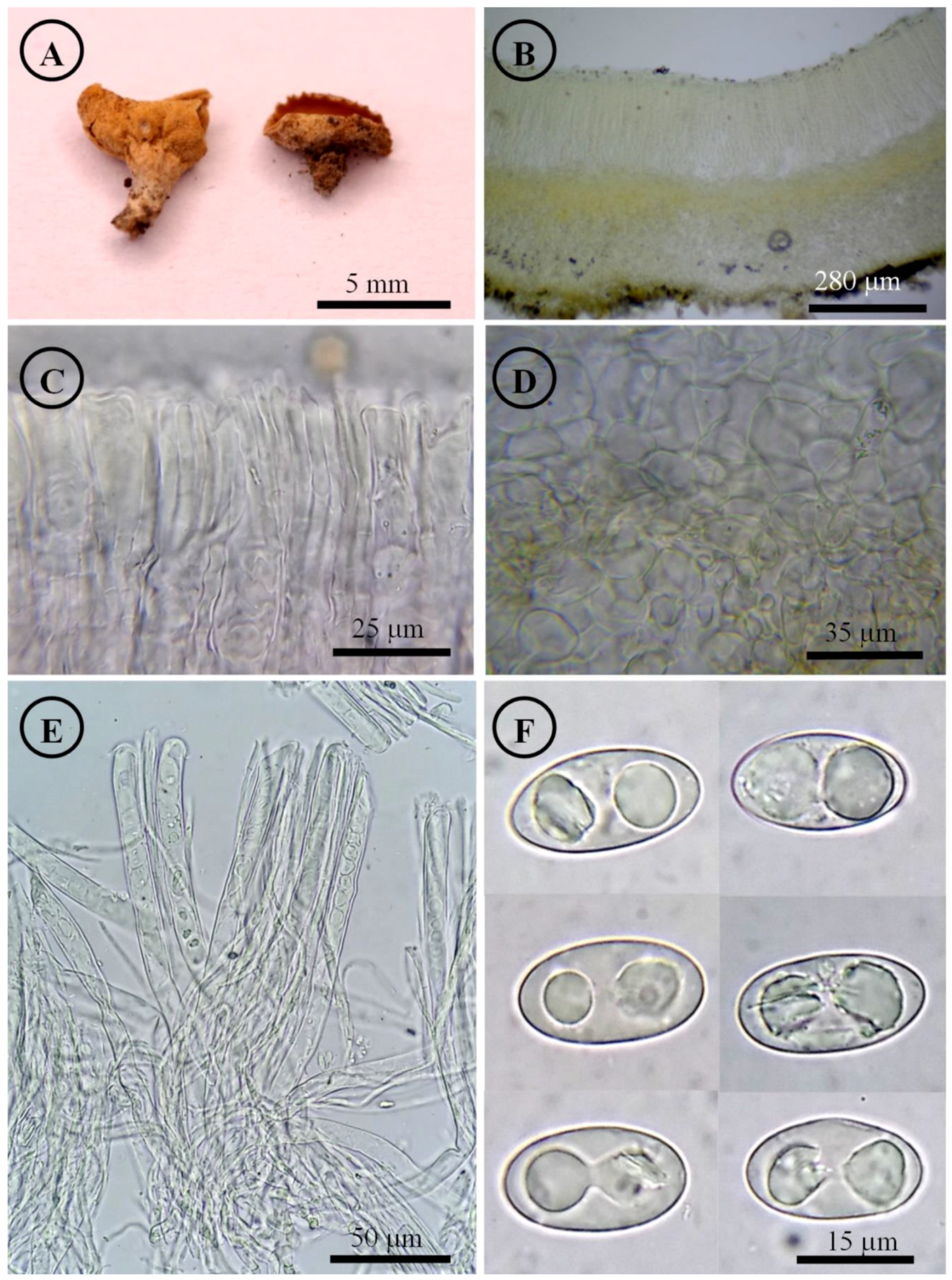

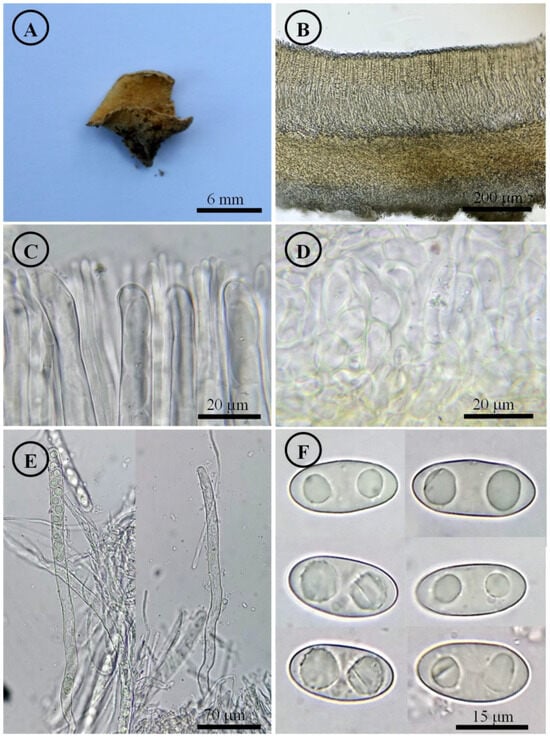

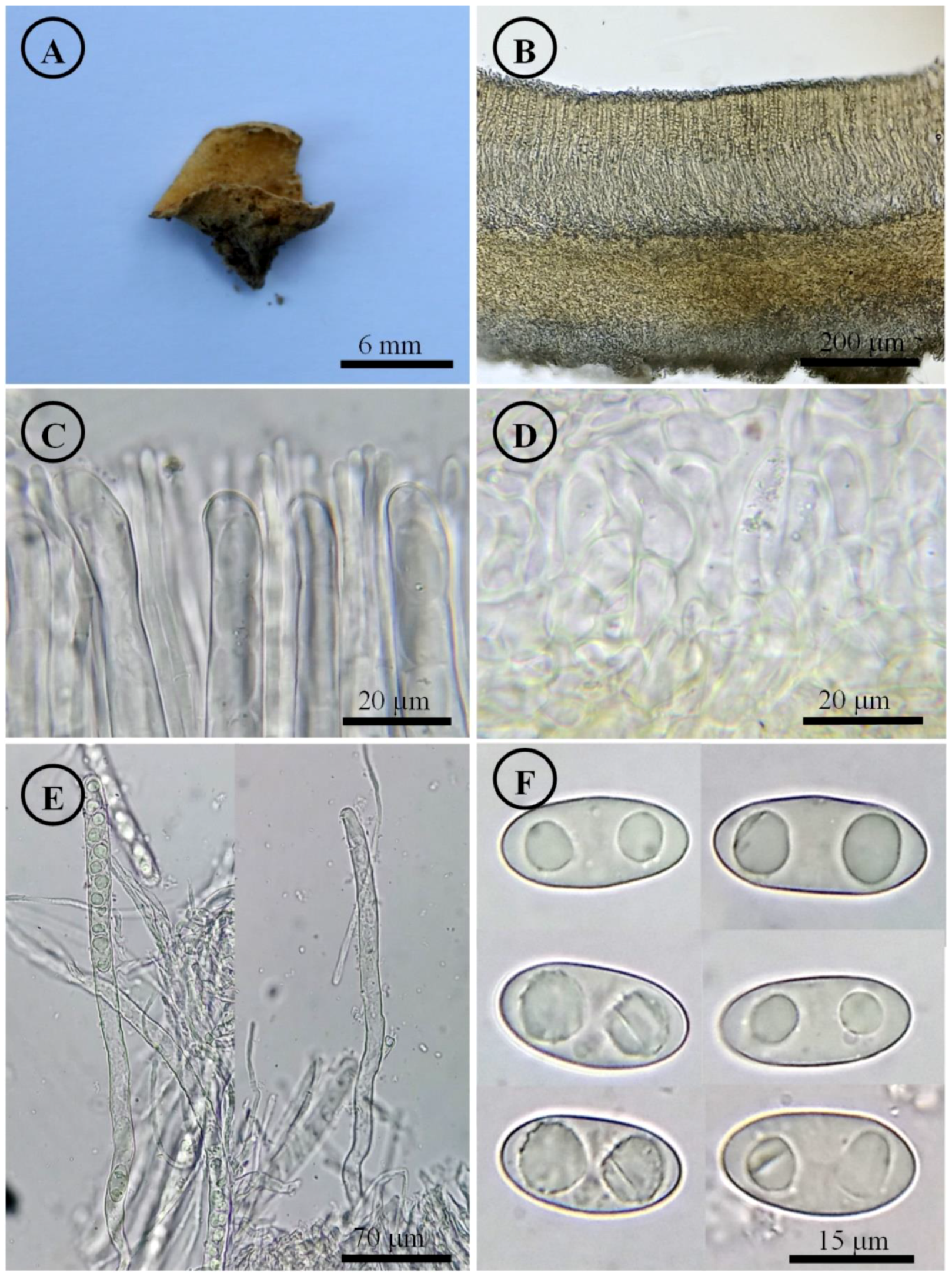

Figure 4.

Tarzetta cupressicola. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Figure 4.

Tarzetta cupressicola. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Notes: This species is characterized by forming apothecia 5–8 mm in diameter and ellipsoid ascospores [18–22 (–23) × 11–13 µm]; although it grows under the canopy of Cupressus lusitanica, this does not indicate that it has a mycorrhiza with this tree species. T. texcocana is similar in morphology but differs due to its ascospores size of 17–21 (–22) × 11–14 (–15) µm and wider paraphyses 3–4 µm in diameter. T. durangensis differs by having a small stipe (1.5 mm long), slightly wider paraphyses (3–4 µm), and slightly longer ascospores 20–24 × 11–13 µm.

Tarzetta davidii Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez, de la Fuente & Raymundo, sp. nov. (Figure 5, Figure 14C and Figure 15C)

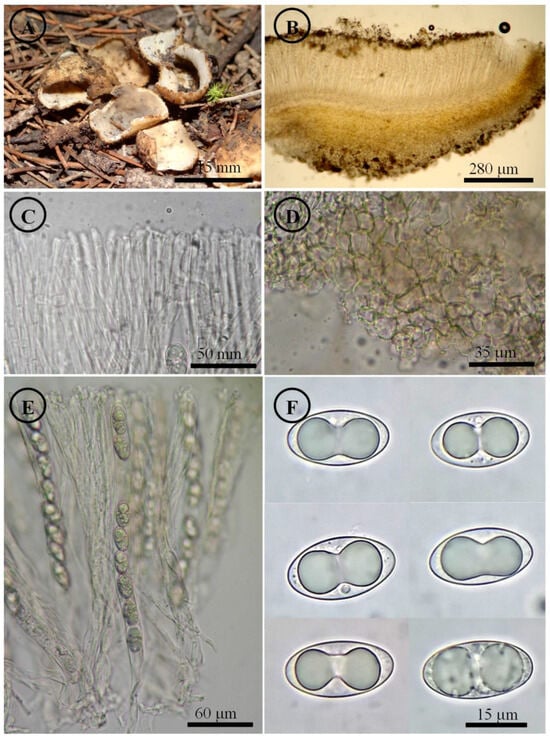

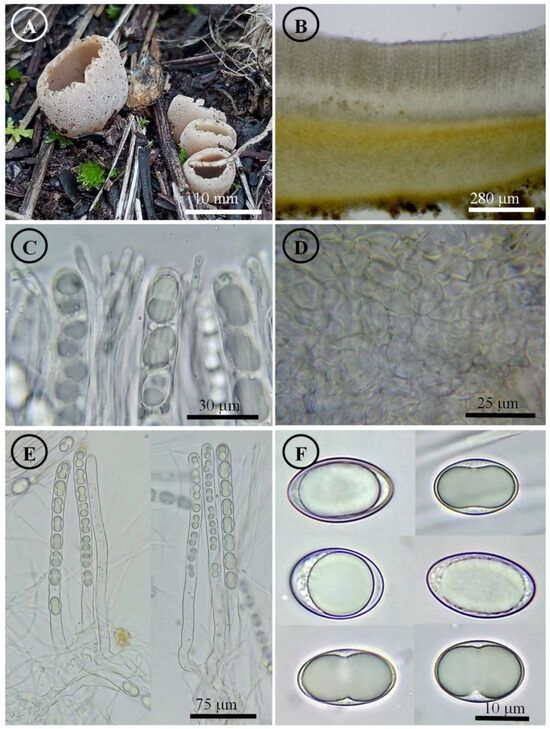

Figure 5.

Tarzetta davidii. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci; and (F) ascospores.

Figure 5.

Tarzetta davidii. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci; and (F) ascospores.

Mycobank: #851434

Diagnosis: Apothecia 15–22 mm diameter, hymenium pale orange, margin crenate to toothed, warty; ascospores (20–) 21–25 (–28) × 11–14 µm, ellipsoid to oblong, grown under Abies religiosa.

Type: MEXICO. Mexico State. Texcoco municipality, Mount Tlaloc (19°24′43.82″ N, 98°44′58.86″ W), 3559 m asl, 9 August 2021, D. González-Sánchez 1 (ITCV, holotype; ENCB, isotype).

GenBank: ITS: PP825390, LSU: PP825433.

Etymology: It is dedicated to David González-Sánchez, who found one of the specimens and encouraged the study of this species, nephew of M. Sánchez-Flores.

Apothecia 15–22 mm in diameter, cupuliform, solitary to scattered, sessile, hymenium pale orange (5A3), margin crenate to toothed, a cleft forms at the base of the apothecium in its connection to the substrate when it matures, external surface color greyish brown (5B3), warty. Ectal excipulum 70–230 µm thick, textura angularis with cells 9–37 × 6–23 µm, subhyaline, thick-walled. Medullary excipulum 543–595 µm thick, textura intricata with hyphae 4–7 µm in diameter, hyaline. Subhymenium undifferentiated. Hymenium 318–375 µm thick. Paraphyses 3–5 µm in diameter, filiform with septate, hyaline, apex rounded with irregular protrusions. Asci 314–350 × 15–18 µm, cylindrical, 8-spored, uniseriate, hyaline, inamyloid. Ascospores (20–) 21–25 (–28) × 11–14 µm [x = 22.8 × 12.2 µm, n = 57], Q = 1.5–2 (–2.2) Qm = 1.8, ellipsoid to oblong, hyaline, with a guttule covering almost the entire spore, smooth on OM, very finely rugose on SEM.

Habit: On soil, in Abies forest, growing under Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. & Cham.

Distribution: MEXICO. Transverse Neovolcanic Axis.

Material examined: Mexico, Mexico City, Álvaro Obregón town hall, Parque Nacional Desierto de los Leones, 4 September 1957, G. Guzmán 1036 (ENCB); loc. cit., 16 August 1969, B.E. Martínez Cosa 26 (ENCB); loc. cit., 29 september 1974, G. Guzmán 12019 (ENCB). Cuajimalpa town hall, Puerto Las Cruces, 10 September 1967, J. Vargas 77 (ENCB). Magdalena Contreras town hall, Los Dinamos, 20 August 1967, G. Hernández Zuñiga 95 (ENCB); loc. cit., 7 October 1974, I. García 40 (ENCB). Tlalpan town hall, Cerro Ocopiazo, 8 August 1968, G. Guzmán 6922 (ENCB). Parres, 24 July 1982, G. Rodríguez 431 (ENCB). Hidalgo state, Mineral del Monte municipality, Parque Nacional El Chico, 6 October 1974, Huerta 23 (ENCB), D. Ramos Zamora 124 (ENCB); loc. cit., 25 September 1977, G. Guzmán 16863 (ENCB), G. Vázquez 31 (ENCB); loc. cit., 22 September 1979, G. Guzmán 17859 (ENCB); loc. cit., 5 October 1980, G. Guzmán 19105 (ENCB); loc. cit., 18 July 1981, S. Acosta 618 (ENCB), 640 (ENCB); loc. cit., 1 August 1981, J. García 1597 (ITCV); loc. cit., 17 October 1982, R. Hirata 451 (ENCB), R. Valenzuela 844 (ENCB); loc. cit., 18 September 1983, R.E. Santillán 461 (ENCB). Near to Real del Monte, 23 August 1970, A. Medina López 24 (ENCB). Mineral del Chico municipality, Parque Nacional El Chico, 5 September 2023, M. Sánchez 3274 (ITCV). Mexico State, Amecameca municipality, Amecameca, 31 August 1969, J. Uribe 9 (ENCB). Donato Guerra municipality, El Capulín, 16 September 1984, L. Colón 891 (ENCB). Ixtapaluca municipality, Parque Nacional Llano Grande, 26 July 1970, M. Vázquez Hurtado 5 (ENCB). Naucalpan municipality, near to Chimalpa, 22 August 1969, J. Gimate 122-B (ENCB). Ocoyoacac municipality, Parque Nacional Insurgente Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, July 1963, E. González 383 (ENCB); loc. cit., 13 August 1967, F. García 160 (ENCB); loc. cit., 8 September 1970, G. Guzmán 8269 (ENCB). Temascaltepec municipality, San Francisco Oxtotilpan, 21 August 1983, L. Colón 115 (ENCB). Road to Nevado de Toluca, 10 October 1977, N. Mora 120 (ENCB). Texcoco municipality, Mount Tlaloc (19°24′43.82″ N, 98°44′58.86″ W), 3559 m asl, 9 August 2021, M. Sánchez 2465 (ITCV); loc. cit., 14 November 2021, M. Sánchez 2599 (ITCV); loc. cit., 16 September 2022, M. Sánchez 2896 (ITCV), 2900 (ITCV); loc. cit., 18 September 2022, M. Sánchez 2961 (ITCV), 2971 (ITCV), L. Sánchez-Correa no number (ITCV); loc. cit., 21 September 2022, M. Sánchez 2996 (ITCV), 3016 (ITCV); loc. cit., 1 October 2023, M. Sánchez 3338 (ITCV). Zinacantepec municipality, deviation to La Peñuela, 23 July 1982, G. Guzmán 21654 (ENCB). Michoacán state, Cd. Hidalgo municipality, La Cabaña, no date, J.T. Martínez Jiménez 1 (ENCB). Pátzcuaro municipality, Los Tanques, 15 August 1980, G. Guzmán 18433 (ENCB; ITS: PP825391, LSU: PP825434). Morelos state, Huitzilac municipality, Parque Nacional Lagunas de Zempoala, 1 August 1982, R.E. Chio 374 (ENCB), G. Rodríguez 475 (ENCB). Colonia Atlixtac, 3 August 1975, G. Guzmán 12315 (ENCB). Querétaro state, Arteaga municipality, El Pingüical hill, 18 August 1990, J. García 6806 (ITCV). Tlaxcala state, Ixtenco municipality, Estación Científica La Malinche, east slope of La Malinche volcano (19°14′43.51″ N, 97°59′40.02″ W), 3166 m asl, 8 December 2018, M. Sánchez 1472 (ENCB; ITS: PP825389, LSU: PP825432), 1475 (ENCB), 1476 (ENCB, paratype; ITS: PP825388, LSU: PP825431); loc. cit., 1 October 2022, M. Sánchez 3060 (ITCV), 3067 (ITCV), 3070 (ITCV). San Pablo del Monte municipality, Parque Nacional La Malinche, 14 September 1983, González Fuentes 466 (ENCB). Tlaxco municipality, on the highway to Zacatlán, 16 September 1979, H. Matamoros 74 (ENCB).

Notes: This species is characterized by forming apothecia 15–22 mm in diameter, on which a cleft forms at the base of the apothecium in connection to the substrate when it matures, and ellipsoid to oblong ascospores [(20–) 21–25 (–28) × 11–14 µm]. It differs from T. miquihuanensis by the apothecia size and smaller ascospores (17–) 18–21 (–22) × 10–13 µm. T. mesophila is a similar species but a cleft does not form at the base of the apothecium at its connection to the substrate, while microscopically shows smaller asci 248–300 × 12–15 µm and slightly narrower ascospores (10–12 µm).

Tarzetta durangensis Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez, R. Valenz. & Raymundo, sp. nov. (Figure 6, Figure 14D and Figure 15D)

Mycobank: #851435

Diagnosis: Apothecia 4–5 mm diameter, pseudostipitate 1.5 mm, margin entire to serrated, hymenium orange, pruinose to asperulate; ascospores 20–24 × 11–13 µm, oblong.

Type: MEXICO. Durango state. Súchil municipality, Stream El Temazcal, paddock Las Alazanas, al W de la Reserva de la Biosfera de Michilía (23°27′28.57″ N, 104°14′55.10″ W), 2200 m asl, 3 September 1983, G. Rodríguez 2600 (ENCB, holotype).

GenBank: ITS: PP825392, LSU: PP825435.

Etymology: The epithet refers to the state where it was collected.

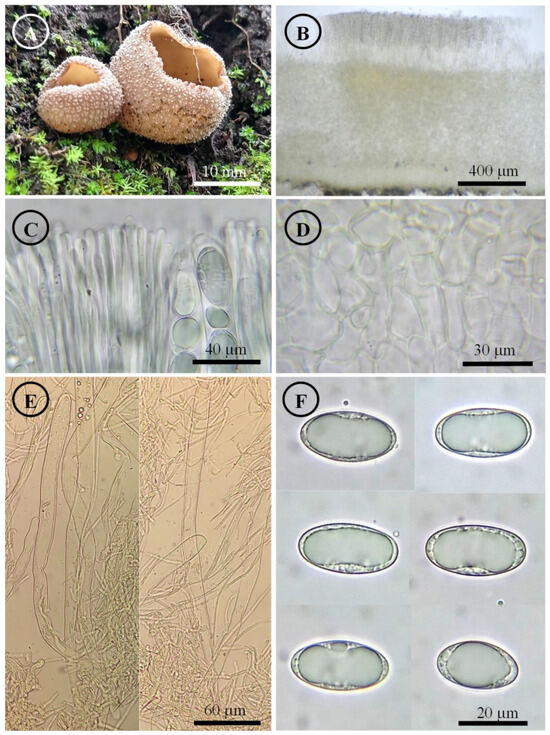

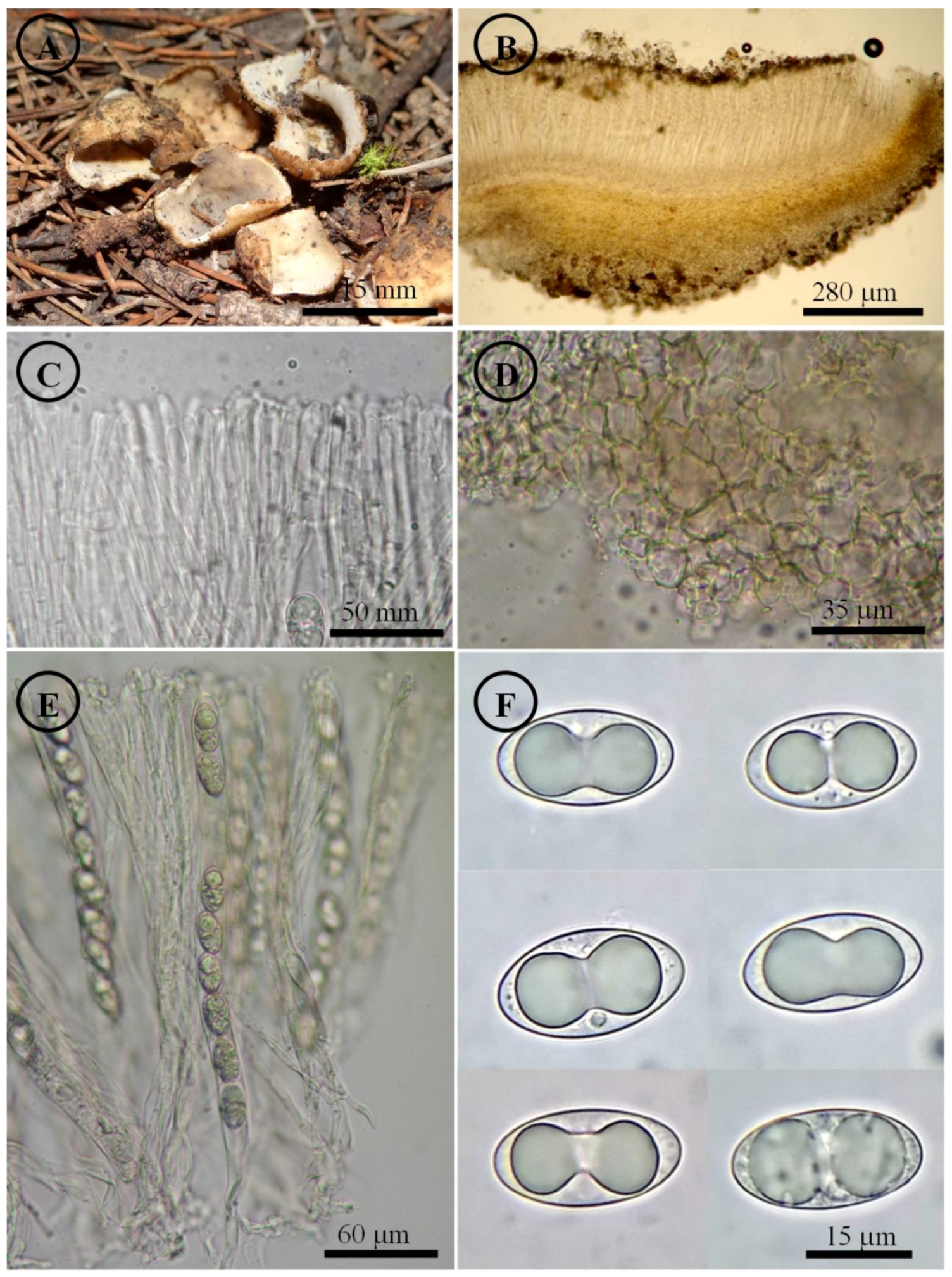

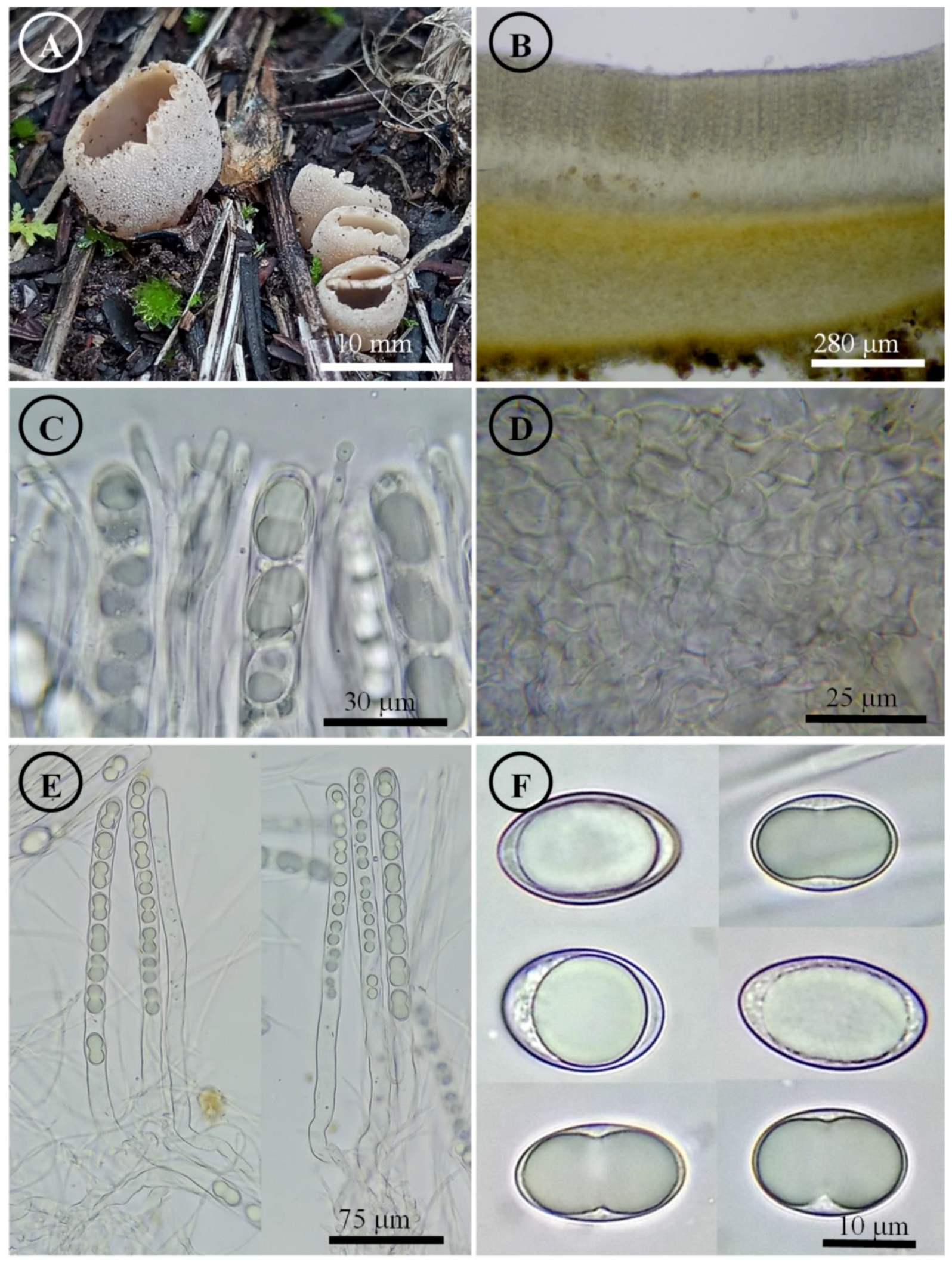

Apothecia 4–5 mm in diameter, cupuliform to discoid, solitary, with a pseudostipitate 1.5 mm long, hymenium orange (5A7), margin entire to serrated, external surface light orange (5a5) to greyish orange (5b5), pruinose to asperulate. Ectal excipulum 80–130 µm thick, textura globulosa/angularis with cells 13–31 × 7–18 µm, hyaline to subhyaline, thin-walled. Medullary excipulum 75–125 µm thick, textura intricata with hyphae 4–7 µm in diameter, hyaline. Subhymenium 55–90 µm thick. Hymenium 230–269 µm thick. Paraphyses 3–4 µm in diameter, septate, filiform, apex rounded, slightly wider, bifurcated. Asci 240–260 × 12–15 µm, cylindrical, 8-spored, uniseriate, hyaline, inamyloid. Ascospores 20–24 × 11–13 µm [x = 21.9 × 12.4 µm, n = 71], Q = 1.5–2.1, Qm = 1.8, oblong, hyaline, 1–2 guttules, smooth on OM, very finely rugose on SEM.

Habit: On soil, in Pinus-Quercus forest.

Distribution: MEXICO. It is only known from the type locality.

Material examined: Mexico, Durango state, Súchil municipality, Trampa El Olvido, Reserva de la Biosfera de Michilía, 16 August 1984, R.E. Santillán 979 (ENCB).

Notes: This species is characterized by forming apothecia 4–5 mm in diameter, with pseudostipitate, oblong ascospores (20–24 × 11–13 µm). Due to its distribution, it could be confused with T. cupressicola; however, this species has larger apothecia of 5–8 mm in diameter, while microscopically, it has smaller ascospores of 18–22 (–23) × 11–13 µm. T. victoriana is close but differs by forming smaller ascospores 17–20 × (–9) 10–11 µm.

Figure 6.

Tarzetta durangensis. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci; and (F) ascospores.

Figure 6.

Tarzetta durangensis. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci; and (F) ascospores.

Tarzetta mesophila Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez & Raymundo, sp. nov. (Figure 7, Figure 14E and Figure 15E)

Mycobank: #851436

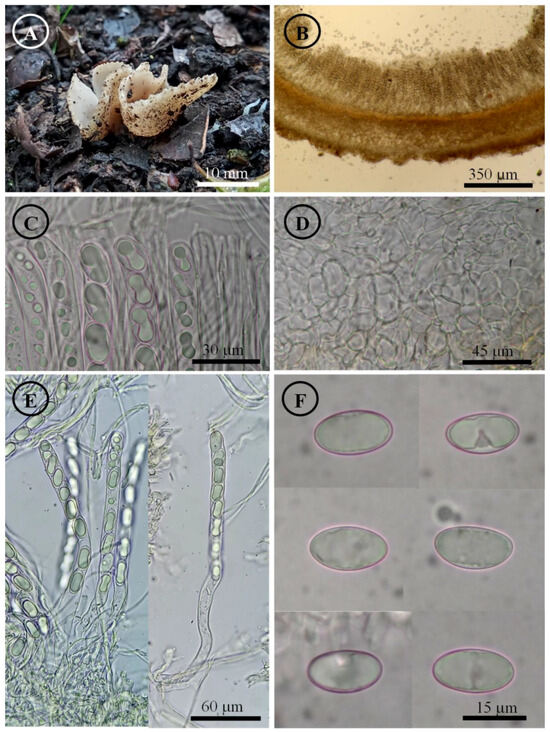

Figure 7.

Tarzetta mesophila. (A) Apothecium; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Figure 7.

Tarzetta mesophila. (A) Apothecium; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Diagnosis: Apothecia 5–9 mm diameter, hymenium light orange, margin toothed to crenate, pruinose; ascospores 19–25 (–26) × 10–12 µm, oblong to cylindrical.

Type: MEXICO. Morelos state. Huitzilac municipality, Sierra Encantada, 4 km S of Tres Marías, old México-Cuernavaca highway (19°1′10.64″ N, 99°12′59.69″ W), 10 July 1982, S. Chacón 160 (ENCB, holotype).

GenBank: ITS: PP825393, LSU: PP825436.

Etymology: The epithet refers to the “mesophyll” or tropical montane cloud forest type of vegetation.

Apothecia 5–9 mm in diameter, cupuliform, solitary to scattered, sessile, hymenium light orange (5A4), margin toothed to crenate, external surface greyish orange (5B3), pruinose to fine-grained. Ectal excipulum 115–170 µm thick, textura angularis with cells 16–30 × 8–18 µm, hyaline to pale yellow with thick-walled. Medullary excipulum 140–210 µm thick, textura intricata with hyphae 4–6 µm in diameter, hyaline. Subhymeniium undifferentiated. Hymenium 255–300 µm thick. Paraphyses 3–4 µm in diameter, filiform, septate, hyaline, apex rounded, irregular. Asci 248–300 × 12–15 µm, cylindrical, 8-spored, uniseriate, hyaline, inamyloid. Ascospores 19–25 (–26) × 10–12 µm [x = 21.7 × 10.7 µm, n = 71], Q = (1.7–) 1.8–2.2 (–2.4) Qm = 1.9, oblong to cylindrical, hyaline, 1–2 guttules, smooth on OM, very finely rugose on SEM.

Habit: On soil, in tropical montane cloud forest

Distribution: MEXICO. Mexico State, Morelos, and Veracruz.

Material examined: Mexico, Mexico State, Tepoztlán municipality, Sierra de Acaparrosa, 7 August 1979, G. Calderón s/n (ENCB). Morelos state, Huitzilac municipality, Tres Marías, 25 August 1967, P. Domínguez 82 (ENCB). Veracruz state, Las Vigas de Ramírez municipality, 30 October 1982, G. Guzmán 22860 (ENCB).

Notes: This species is characterized by forming apothecia 5–9 mm in diameter and oblong to cylindrical ascospores [19–25 (–26) × 10–12 µm]. It differs macroscopically from T. davidii by not forming a cleft at the base of the apothecium with its connection to the substrate, while microscopically, T. mesophila presents larger asci 248–300 × 12–15 µm and smaller ascospores unlike T. davidii [(20–) 21–25 (–28) × 11–14 µm]. T. miquihuanensis has similar morphology but is distributed in northeastern Mexico and is macroscopically larger at 33–57 mm in diameter, while microscopically, it forms smaller asci (225–335 × 9–13 µm) and ascospores [(17–) 18–21 (–22) × 10–13 µm].

Tarzetta mexicana Sánchez-Flores, Raymundo, de la Fuente & García-Jiménez, sp. nov. (Figure 8, Figure 14F and Figure 15F)

Mycobank: #851437

Diagnosis: Apothecia 5–17 mm diameter, hymenium whitish yellow, margin erose to crenate, granular pruinose; ascospores (18–) 19–22 × 10–12 µm, ellipsoid to oblong, grown under Quercus spp.

Type: MEXICO. Tamaulipas state, Miquihuana municipality, km 12 road Peña-Aserradero (23°36′03.79″ N, 99°42′22.88″ W), 2663 m asl, 03 October 2019, M. Sánchez, 1709 (ITCV, holotype; ENCB, isotype).

GenBank: ITS: PP825395, LSU: PP825438.

Etymology: The epithet refers to the country of origin of the specimens.

Apothecia 5–17 mm in diameter, cupuliform, solitary to gregarious, sessile, color orange-gray (5B2), margin erose to crenate, hymenium smooth, whitish yellow (4A2), external surface somewhat granular pruinose. Ectal excipulum 95–160 µm thick, textura angularis with cells 7–36 × 5–27 µm, subhyaline, ectal hyphae 3–5 µm in diameter, hyaline. Medullary excipulum 50–138 µm thick, textura intricata with hyphae 2.5–6 µm in diameter, hyaline. Subhymenium 25–58 µm thick. Hymenium 250–315 µm thick. Paraphyses 2–3 µm in diameter, filiform, hyaline, septate, slightly branched. Asci 220–310 × 11–14 µm, cylindrical, 8-spored, uniseriate, nailed, hyaline, inamyloid. Ascospores (18–) 19–22 × 10–12 µm [x = 19.9 × 11 µm, n = 74], Q = 1.5–2.1, Qm = 1.8, ellipsoid to oblong, hyaline, with a guttule that covers almost all spore, smooth on OM, finely rugose on SEM.

Habit: On soil, in forest Quercus-Pinus, grown under Quercus spp.

Distribution: MEXICO. Hidalgo, Jalisco, Puebla, Querétaro, and Tamaulipas.

Material examined: Mexico. Hidalgo state, Zacualtipan municipality, La Mojonera, 5 September 2023, M. Sánchez 3264 (ITCV). Jalisco state, road Ciudad Guzmán-San Andrés Ixtlán-El Corralito, 24 August 1974, G. Guzmán 11978 (ENCB; ITS: PP825397, LSU: PP825440). Mexico State, Iturbide municipality, Presa Iturbide, 3 October 1980, L. Guzmán-Dávalos 69 (ENCB; ITS: PP825396, LSU: PP825439). Puebla state, Atempan municipality, Canoas, soccer field, 14 September 2014, M. Sánchez 200 (FEZA; ITS: PP825398, LSU: PP825441); loc. cit., 8 October 2022, M. Sánchez, 3099 (ITCV). Capitanco hill, 7 October 2022, M. Sánchez, 3088 (ITCV), 3090 (ITCV), 3093 (ITCV). Querétaro state, Amealco municipality, Laguna de Servín (20°16′9.59″ N, 100°15′12.94″ W), 2738 m asl, 16 September 2011, J. García 18851 (ITCV, paratype; ITS: PP825394, LSU: PP825437).

Figure 8.

Tarzetta mexicana. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Figure 8.

Tarzetta mexicana. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Notes: This species is characterized by forming apothecia 5–17 mm in diameter and ellipsoid ascospores [(18–) 19–22 × 10–12 µm]. Tarzetta mexicana differs from T. victoriana by having smaller ascospores (17–20 × (9–) 10–11 µm) and wider paraphyses (2–5 µm). Tarzetta poblana is similar in morphology but with smaller asci (170–205 × (11–) 13–15 µm) and ascospores [(16–22 × 9–12 (–13) µm]. Microscopically, it differs from T. americupularis by the larger ascospores of (15–) 17–25 (–26) × 9–13 (–14) µm. Tarzetta texcocana shows larger apothecia (4–14 mm in diameter) and wider ascospores [17–21 (–22) × 11–14 (–15) µm].

Tarzetta miquihuanensis Sánchez-Flores, Raymundo, Hernández-Muñoz & García-Jiménez, sp. nov. (Figure 9, Figure 14G and Figure 16A)

Mycobank: #851438

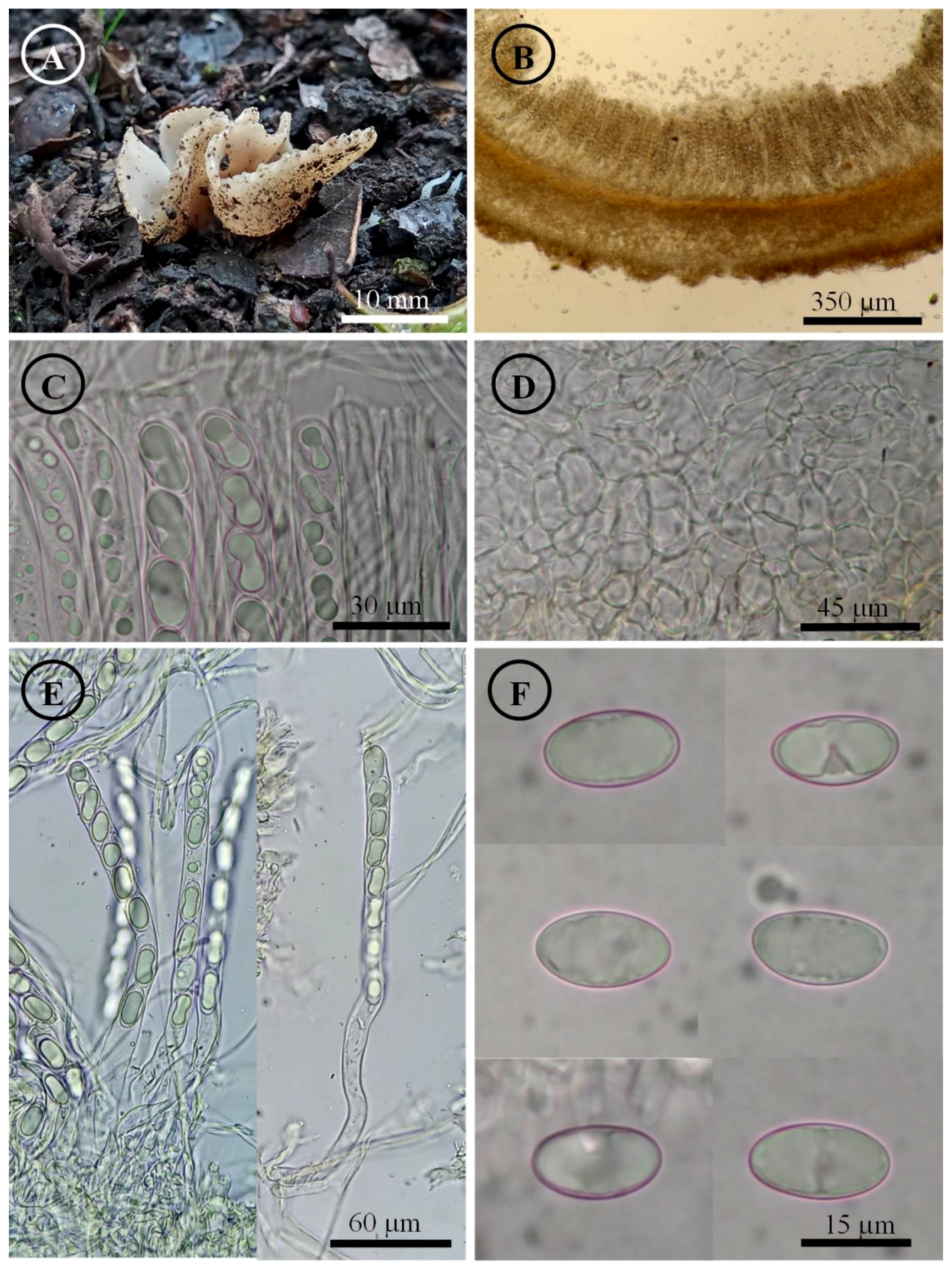

Diagnosis: Apothecia 33–57 mm diameter, hymenium pale orange, margin entire to crenate, grainy; ascospores (17–) 18–21 (–22) × 10–13 µm, ellipsoid, grown under Quercus ariifolia and Q. pablillensis.

Type: MEXICO. Tamaulipas state. Miquihuana municipality, km 12 road Peña-Aserradero, La Peña (23°36′03.79″ N, 99°42′22.88″ W), 2663 m asl, 3 October 2019, M. Sánchez 1696 (ITCV, holotype; ENCB, isotype).

GenBank: ITS: PP825399, LSU: PP825442.

Etymology: The epithet refers to the municipality where it was collected.

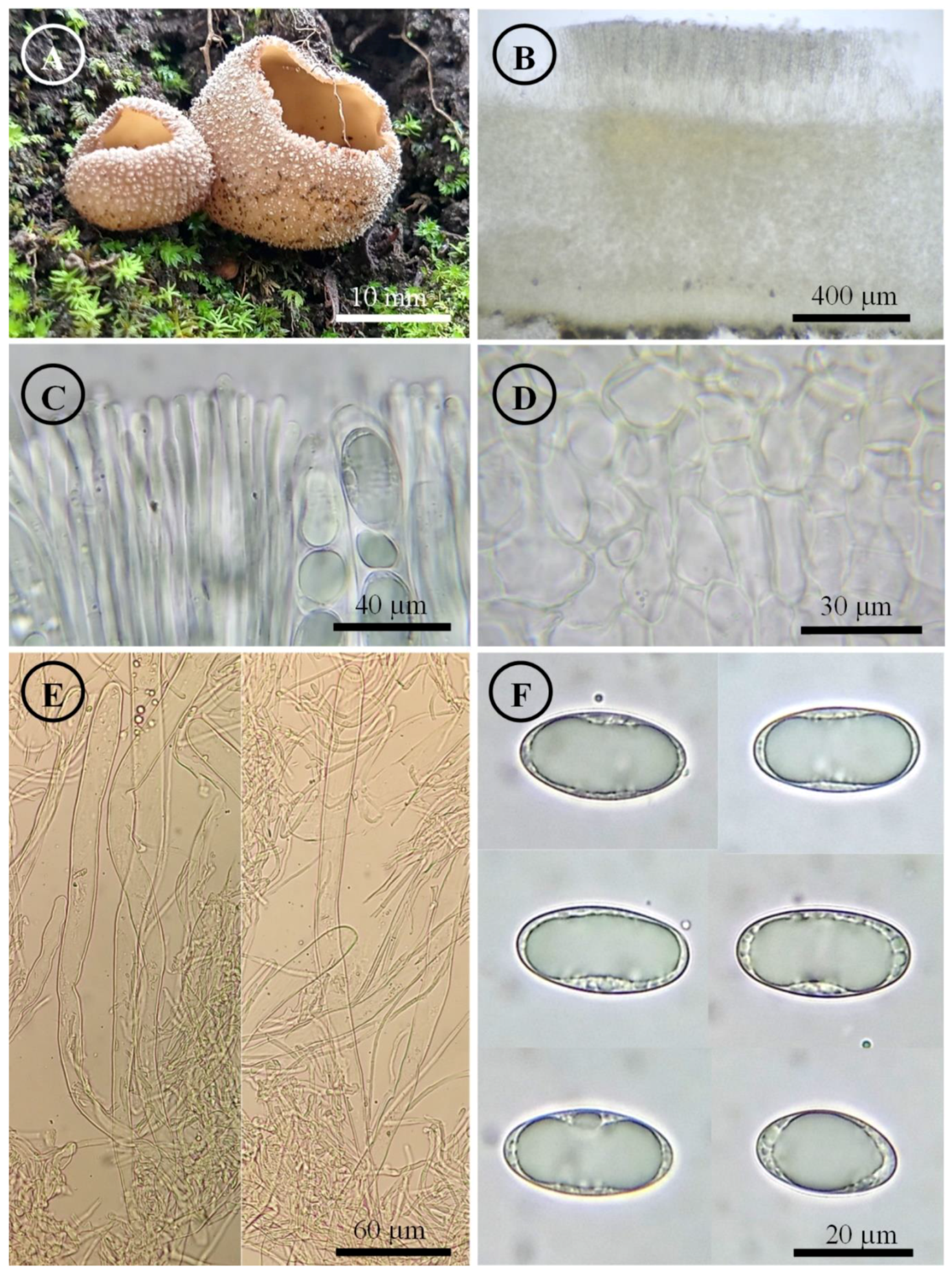

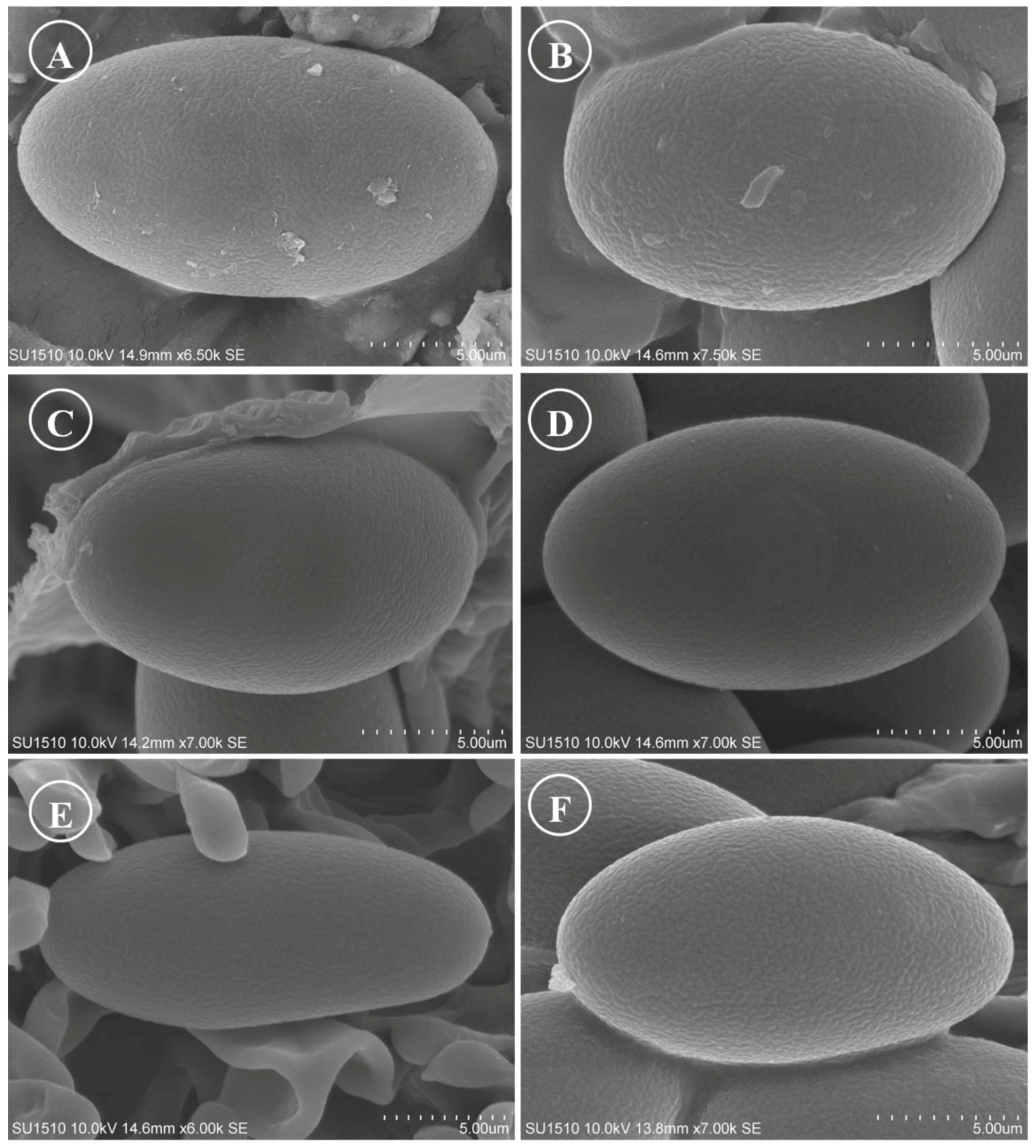

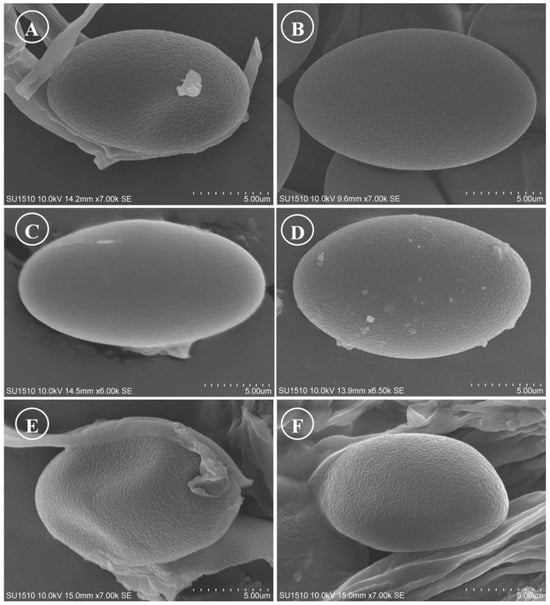

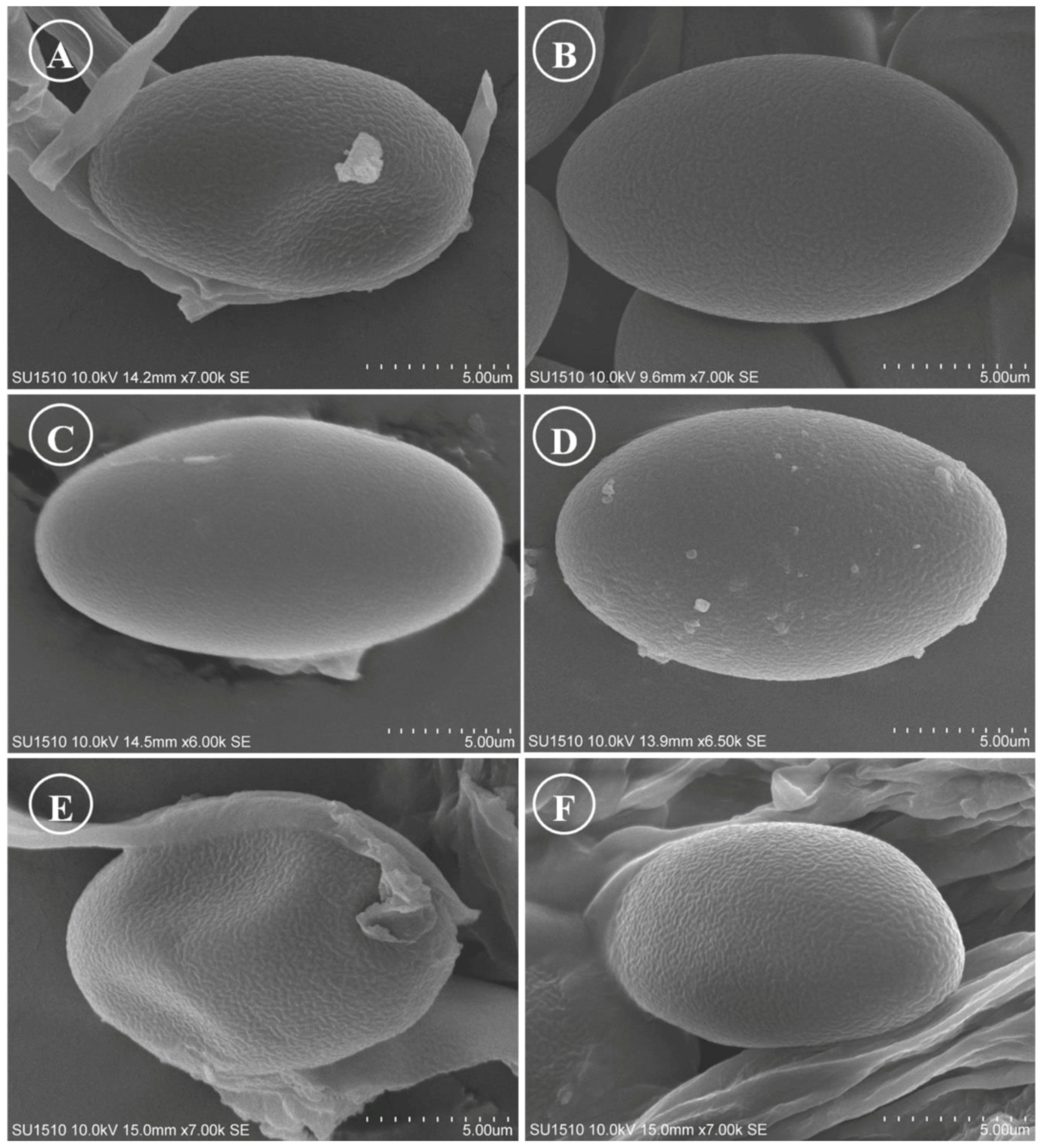

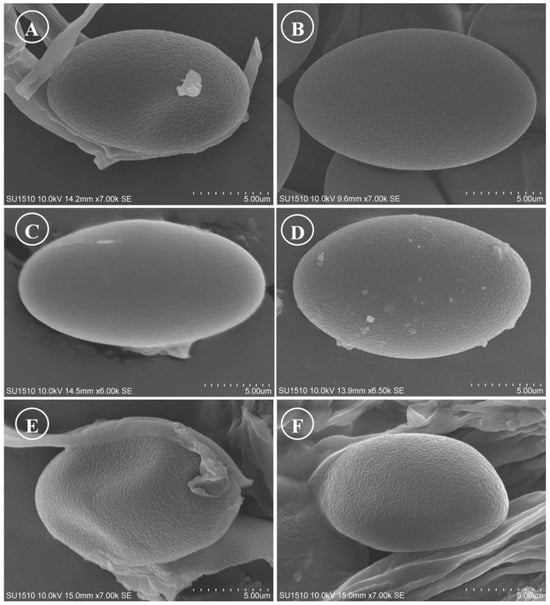

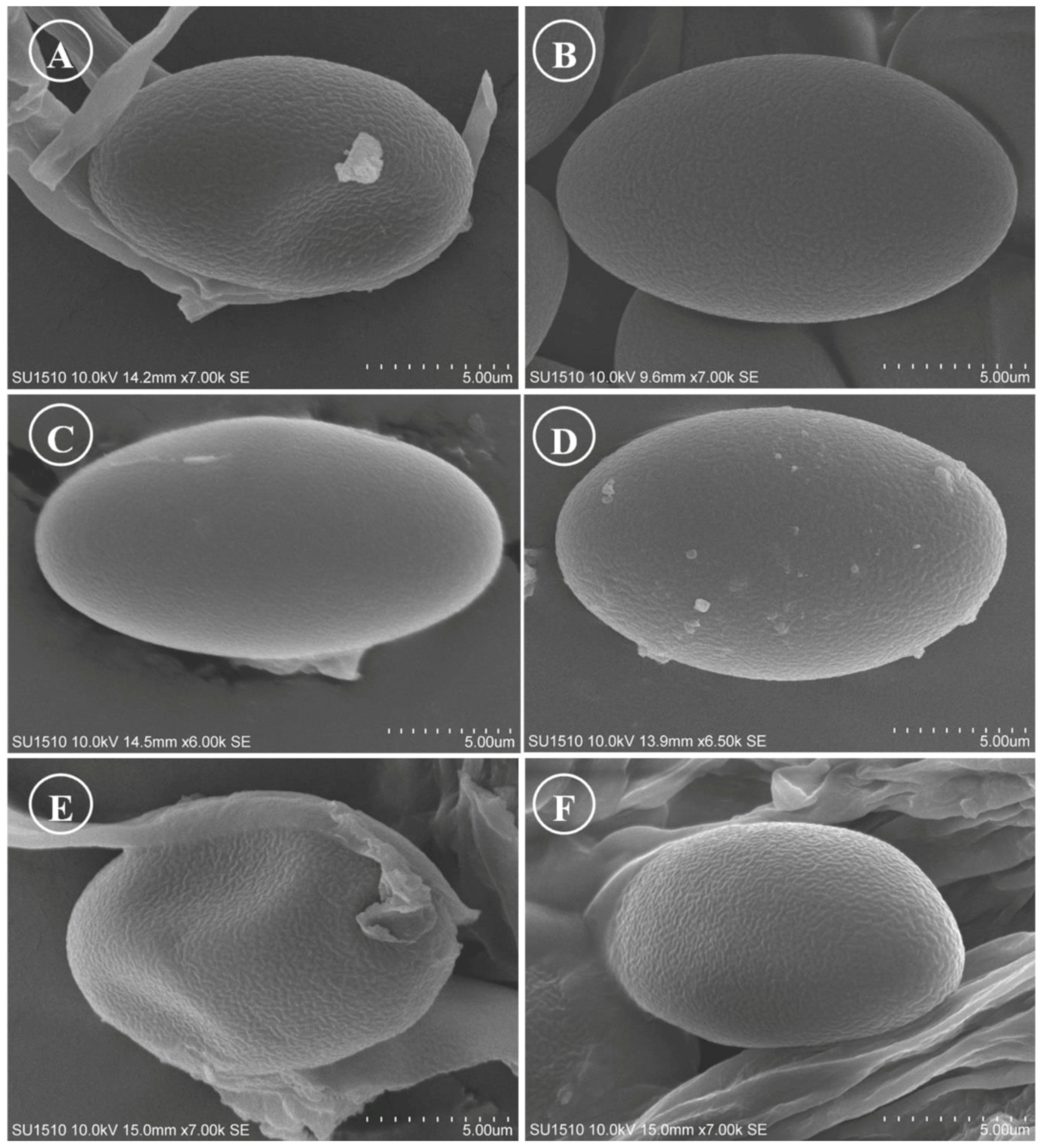

Apothecia 33–57 mm in diameter, cupuliform, solitary to gregarious, sessile, color pale orange (5A3), margin entire to crenate, hymenium smooth, colorless, folded to join the substrate, external surface somewhat granular pruinose whitish and grainy. Ectal excipulum 95–250 µm thick, textura globulosa/angularis with cells by 8–48 × 6–22 µm, subhyaline, thin wall. Medullary excipulum 240–520 µm thick, textura intricata with hyphae 3–5 µm in diameter, subhyaline. Subhymenium 30–75 µm thick. Hymenium 225–340 µm thick. Paraphyses 2–5 µm in diameter, filiform, hyaline, markedly septate, bifurcated. Asci 225–335 × 9–13 µm, cylindrical, 8-spored, nailed, hyaline, inamyloid. Ascospores (17–) 18–21 (–22) × 10–13 µm [x = 18.8 × 11.4 µm, n = 65], Q = 1.3–1.8 (–2), Qm = 1.6, ellipsoid, hyaline, one guttule that covers almost the entire spore, sometimes two guttules, smooth on OM, finely rugose on SEM.

Habit: On soil, in Quercus-Pinus forest, grown under Quercus ariifolia Trel. and Q. pablillensis C.H. Mull.

Distribution: MEXICO. Nuevo León and Tamaulipas.

Material examined: Mexico, Nuevo León state, Santiago municipality, El Tejocote, 18 October 1980, S. Chacón 54 (ENCB). Zaragoza municipality, El Tropezón, La Encantada, 11 July 1985, E. Cázares s/n (ITCV). Tamaulipas state, Miquihuana municipality, km 12 road Peña-Aserradero, La Peña (23°36′03.79″ N, 99°42′22.88″ W), 2663 m asl, 3 October 2014, J. García 20185 (ITCV); loc. cit., 3 October 2019, M. Sánchez 1698 (ITCV), 1705 (ITCV), 1707 (ITCV), 1710 (ITCV); loc. cit., 19 October 2019, M. Sánchez 1777 (ITCV, FEZA paratype; ITS: PP825400, LSU: PP825443). La Marcela port, 27 September 2013, J. García 19411 (ITCV).

Notes: This species is characterized by forming large apothecia 33–57 mm in diameter and ellipsoid ascospores of (17–) 18–21 (–22) × 10–13 µm. It differs from the other species of the genus by having larger apothecia and markedly septate paraphyses, even when immature. T. davidii is close but the apothecia is smaller (15–22 mm diameter) and the ascospores are larger (20–) 21–25 × 11–14 µm and it grows under Abies religiosa.

Figure 9.

Tarzetta miquihuanensis. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Figure 9.

Tarzetta miquihuanensis. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Tarzetta poblana Sánchez-Flores, Raymundo, Avila-Ortiz & García-Jiménez, sp. nov. (Figure 10, Figure 14H and Figure 16B)

Mycobank: #851439

Diagnosis: Apothecia 2–7 mm diameter, hymenium brownish orange, margin involute, entire to crenate, finely warty; ascospores 16–22 × 9–12 (–13) µm, ellipsoid to oblong.

Figure 10.

Tarzetta poblana. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Figure 10.

Tarzetta poblana. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Type: MEXICO. Puebla state. Atempan municipality, Capitanco hill (19°49′1″ N, 97°27′5.43″ W), 2064 m asl, 13 September 2014, M. Sánchez 105 (FEZA, holotype; ENCB, isotype).

GenBank: ITS: PP825403, LSU: PP825446.

Etymology: The epithet refers to the state where the type specimen was collected.

Apothecia 2–7 mm in diameter, cupuliform, solitary to scattered, sessile, hymenium brownish orange (5C3) to yellowish white (4A2), margin involute, entire to crenate, lacerated when aged, external surface somewhat granular pruinose pale orange (5A3) to yellowish white (4A2), finely warty. Ectal excipulum 48–75 µm thick, textura angularis with cells 9–28 × 6–25 µm, hyaline, thin-walled. Medullary excipulum 60–120 µm thick, textura intricata with hyphae 3–6 µm in diameter, hyaline. Subhymenium 15–30 µm thick. Hymenium 180–210 µm thick. Paraphyses 2–3 µm in diameter, septate, filiform, apex rounded. Asci 170–205 × (11–) 13–15 µm, cylindrical, 8-spored, uniseriate, hyaline, inamyloid. Ascospores 16–22 × 9–12 (–13) µm [x = 19 × 11 µm, n = 68], Q = 1.5–2.1, Qm = 1.8, ellipsoid to oblong, hyaline, rare subcylindrical, one guttule, smooth on OM, very finely rugose on SEM.

Habit: On soil, in Pinus-Quercus and coniferous forest.

Distribution: MEXICO. East and central Mexico.

Material examined: Mexico, Mexico State, Amecameca municipality, Ameyalco ravine, 29 January 1980, R. Valenzuela 204 (ENCB). Road to Amecameca-Tlamacas, 23 September 1975, J. Paden 1073 (ENCB; ITS: PP825402, LSU: PP825445). Temascaltepec municipality, around of San Francisco Oxtotilpan, Parque Nacional Nevado de Toluca, 21 August 1983, L. Colón 122 (ENCB; ITS: PP825404, LSU: PP825447). Puebla state, Atempan municipality, Las Canoas, soccer field, 8 October 2022, M. Sánchez 3096 (ITCV). Juan Galindo municipality, Necaxa, August 1967, H.A. Ríos 47 (ENCB, paratype; ITS: PP825401, LSU: PP825444). Tlaxcala state, Jilotepec municipality, road Villa de Mariano, 30 September 2022, M. Sánchez 3051 (ITCV), 3052 (ITCV), 3054 (ITCV), 3055 (ITCV), 3056 (ITCV), 3058 (ITCV).

Notes: This species is characterized by forming small apothecia 2–7 mm in diameter and ellipsoid to oblong ascospores [16–22 × 9–12 (–13) µm]. Tarzetta mexicana is a similar species but has larger apothecia (5–17 mm), smaller ascospores of (18–) 19–22 × 10–12 µm, slightly wider paraphyses (2–4 µm), and less septate than T. poblana. Tarzetta texcocana is also similar but shows larger apothecia (4–14 mm), more crenate edge, asci of 260–280 × 12–15 µm, and slightly wider ascospores of 17–21(–22) × 11–14 (–15) µm.

Tarzetta pseudobronca Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez, Martínez-González & Raymundo, sp. nov. (Figure 11, Figure 14I and Figure 16C)

Mycobank: #851440

Diagnosis: Apothecia 13–18 mm diameter, with a pseudostipitate of 2 mm long, hymenium light orange, margin entire to crenate, pruinose to granular; ascospores 21–25 × 12–15 µm, ellipsoid to oblong, grown under Pinus cembroides.

Type: MEXICO. Tamaulipas state. Miquihuana municipality, Km 12 road Peña-Aserradero (23°36′03.79″ N, 99°42′22.88″ W), 2661 m asl, 3 October 2014, J. García 20240 (ITCV, holotype; ENCB, isotype).

GenBank: ITS: PP825405, LSU: PP825448.

Etymology: The epithet refers to the morphological similarity with T. bronca (Peck) Korf & J. K. Rogers.

Apothecia 13–18 mm in diameter, cupuliform, gregarious, with a 2 mm long pseudostipite, hymenium light orange color (5A4), margin entire to crenated that tear with maturity, external surface light brown (7D7) with pruinose to granular texture. Ectal excipulum 82.5–150 µm thick, textura angularis with cells 13–25 × 7–20 µm, subhyaline, thin-walled, ectal hyphae 22–33 × 5–9 µm, hyaline. Medullary excipulum 175–305 µm thick, textura intricata with hyphae 4–7 µm in diameter, hyaline. Subhymenium undifferentiated. Hymenium 250–255 µm thick. Paraphyses 3–6 µm in diameter, filiform, hyaline, septate, branched, slightly widening towards the apex. Asci 215–250 × 13–15 µm, cylindrical, 8-spored, uniseriate, hyaline, inamyloid. Ascospores 21–25 × 12–15 µm [x = 22.1 × 12.5 µm, n = 65], Q = 1.5–2, Qm = 1.7, ellipsoid to oblong, hyaline, 1–2 guttules, smooth on OM, very finely rugose on SEM.

Habit: On soil, in Quercus-Pinus forest, grown under Pinus cembroides Zucc.

Distribution: MEXICO. It is only known from the municipality of the type locality.

Figure 11.

Tarzetta pseudobronca. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Figure 11.

Tarzetta pseudobronca. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Material examined: Mexico, Tamaulipas state, Miquihuana municipality, km 6 road Peña-Aserradero, La Peña (23°34′55.31″ N, 99°42′40.03″ W), 2257 m asl, 27 September 2008, J. García 17554 (ITCV).

Notes: This species is characterized by forming small apothecia 13–18 mm in diameter and ellipsoid to oblong ascospores (21–25 × 12–15 µm). Tarzetta bronca is a similar species but with larger apothecia (10–35 mm in diameter), asci (250–350 × 12–16 µm), and ascospores (20–24 × 12–14 µm) [39,40] vs. T. pseudobronca.

Mycobank: #851441

Figure 12.

Tarzetta texcocana. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Figure 12.

Tarzetta texcocana. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Diagnosis: Apothecia 4–14 mm diameter, hymenium greyish orange, margin entire, crenate to lacerate, grained; ascospores 17–21 (–22) × 11–14 (–15) µm, broadly ellipsoid, grown under Quercus spp.

Type: MEXICO. Mexico state, Texcoco municipality, Mount Tlaloc (19°24′43.82″ N, 98°44′58.86″ W), 3559 m asl, 14 November 2021, M. Sánchez 2585 (ITCV, holotype; ENCB, FEZA, isotype).

GenBank: ITS: PP825407, LSU: PP825450.

Etymology: The epithet refers to the municipality of origin of the specimens.

Apothecia 4–14 mm in diameter, cupuliform when young to discoid when old, solitary to scattered, sessile, hymenium greyish orange (5B3), margin entire, crenate to lacerate, external surface orange-white (5A2) to pale orange (5A3), grained. Ectal excipulum 65–115 µm thick, textura angularis with cells 11–30 × 8–20 µm, hyaline, thin wall, terminals hyphae 14–31 × 5–6 µm, hyaline. Medullary excipulum 145–210 µm thick, textura intricata with hyphae 3–7 µm in diameter, hyaline. Subhymenium 63–100 µm thick. Hymenium 255–290 µm thick. Paraphyses 3–4 µm in diameter, filiform, septate, apex rounded, nodulose, bifurcated at the base. Asci 260–280 × 12–15 µm, cylindrical, 8-spored, uniseriate, hyaline, inamyloid. Ascospores 17–21 (–22) × 11–14 (–15) µm [x = 19.5 × 13 µm, n = 64], Q = 1.2–1.7, Qm = 1.4, broadly ellipsoid, hyaline, one guttule that covers almost the entire ascospore, smooth on OM, finely rugose on SEM.

Habit: On soil, in mixed forest, grown under Quercus spp.

Distribution: MEXICO. It is only known from the type locality.

Material examined: Mexico, Mexico State, Texcoco municipality, Mount Tlaloc (19°24′43.82″ N, 98°44′58.86″ W), 3559 m asl, 14 November 2021, M. Sánchez 2576 (ITCV, FEZA, paratype; ITS: PP825406, LSU: PP825449), 2587 (ITCV), 2590 (ITCV), 2593 (ITCV), 2597 (ITCV); loc. cit., 16 September 2022, M. Sánchez 2890 (ITCV), 2894 (ITCV), 2902 (ITCV), 2904 (ITCV), 2906 (ITCV), 2910 (ITCV), 2912 (ITCV); loc. cit., 18 September 2022, M. Sánchez 2977 (ITCV); loc. cit., 21 September 2022, M. Sánchez 2994 (ITCV), 2999 (ITCV), 3002 (ITCV), 3007 (ITCV), 3012 (ITCV); loc. cit., 4 October 2022, M. Sánchez 3079 (ITCV); loc. cit., 1 October 2023, M. Sánchez 3339 (ITCV); loc. cit., 4 October 2023, M. Sánchez 3374 (ITCV).

Notes: This species is characterized by forming small apothecia 4–14 mm in diameter, and broadly ellipsoid ascospores [17–21 (–22) × 11–14 (–15) µm]. Tarzetta cupressicola is a similar species but with narrower paraphyses (2–3 µm) and ascospores of 18–22 × 11–13 µm and is associated with Cupressus lusitanica. Tarzetta poblana is a similar species but with apothecia smaller than 2–7 mm, narrower paraphyses (2–3 µm), asci of 170–205 × 13–15 µm, and ascospores of 17–21 (–22) × 9–12 µm. Tarzetta mexicana differs by forming narrower ascospores of (18–) 19–22 × 10–12 µm.

Tarzetta victoriana Sánchez-Flores, Raymundo, Hernández-Del Valle & García-Jiménez, sp. nov. (Figure 13, Figure 14K,L and Figure 16E,F)

Mycobank: #851442

Diagnosis: Apothecia 2–25 mm diameter, hymenium pale orange, margin involute to crenate, pruinose to grainy; ascospores 17–20 × (9–) 10–11 µm, ellipsoid, grown under Quercus rysophylla and Q. polymorpha.

Type: MEXICO. Tamaulipas state. Victoria municipality, Puerto El Paraíso community (23°31′38.99″ N, 99°12′20.04″ W), 1650 m asl, 17 October 2019, M. Sánchez 1752 (ITCV, holotype; ENCB, isotype).

GenBank: ITS: PP825409, LSU: PP825452.

Etymology: The epithet refers to the municipality where it was collected and described for the first time.

Apothecia 2–25 mm in diameter, cupuliform, solitary to gregarious, sessile, sometimes pseudostipitate, hymenium pale orange (5A3) to brownish orange (5C3), margin involute to crenate, hymenium smooth, external surface greyish orange color (5B4) to brownish orange (5C3), pruinose to grainy. Ectal excipulum 55–125 µm thick, textura globulosa/angularis with cells 10–33 × 7–26 µm, subhyaline, with ectal hyphae of 3–6 µm in diameter, hyaline. Medullary excipulum 85–128 µm thick, textura intricata with hyphae 2–5 µm in diameter, subhyaline. Subhymenium undifferentiated. Hymenium 225–295 µm thick. Paraphyses 2–5 µm in diameter, filiform, hyaline, septate, branched, with the apex slightly widened and irregular. Asci 225–280 × 11–13 µm, cylindrical, 8-spored, nailed, hyaline, inamyloid. Ascospores 17–20 × (9–) 10–11 µm [x = 18.8 × 10.2 µm, n = 66], Q = 1.6–2 (–2.1), Qm = 1.8, ellipsoid, hyaline, one guttule spanning all spore, smooth on OM, finely rugose on SEM.

Figure 13.

Tarzzetta victoriana. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

Figure 13.

Tarzzetta victoriana. (A) Apothecia; (B) longitudinal section of the apothecium; (C) hymenium; (D) ectal excipulum cells; (E) asci and ascospores; and (F) ascospores.

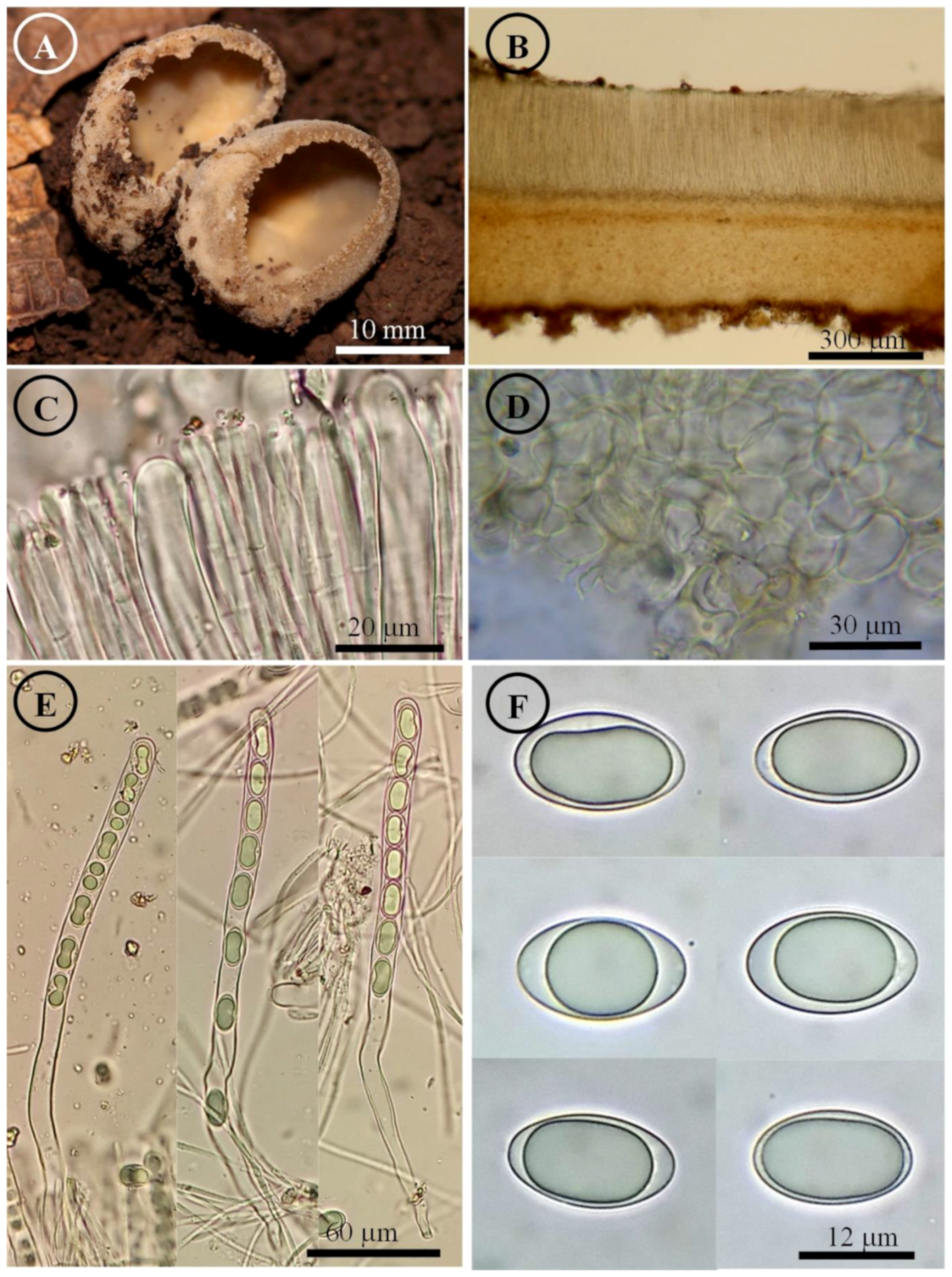

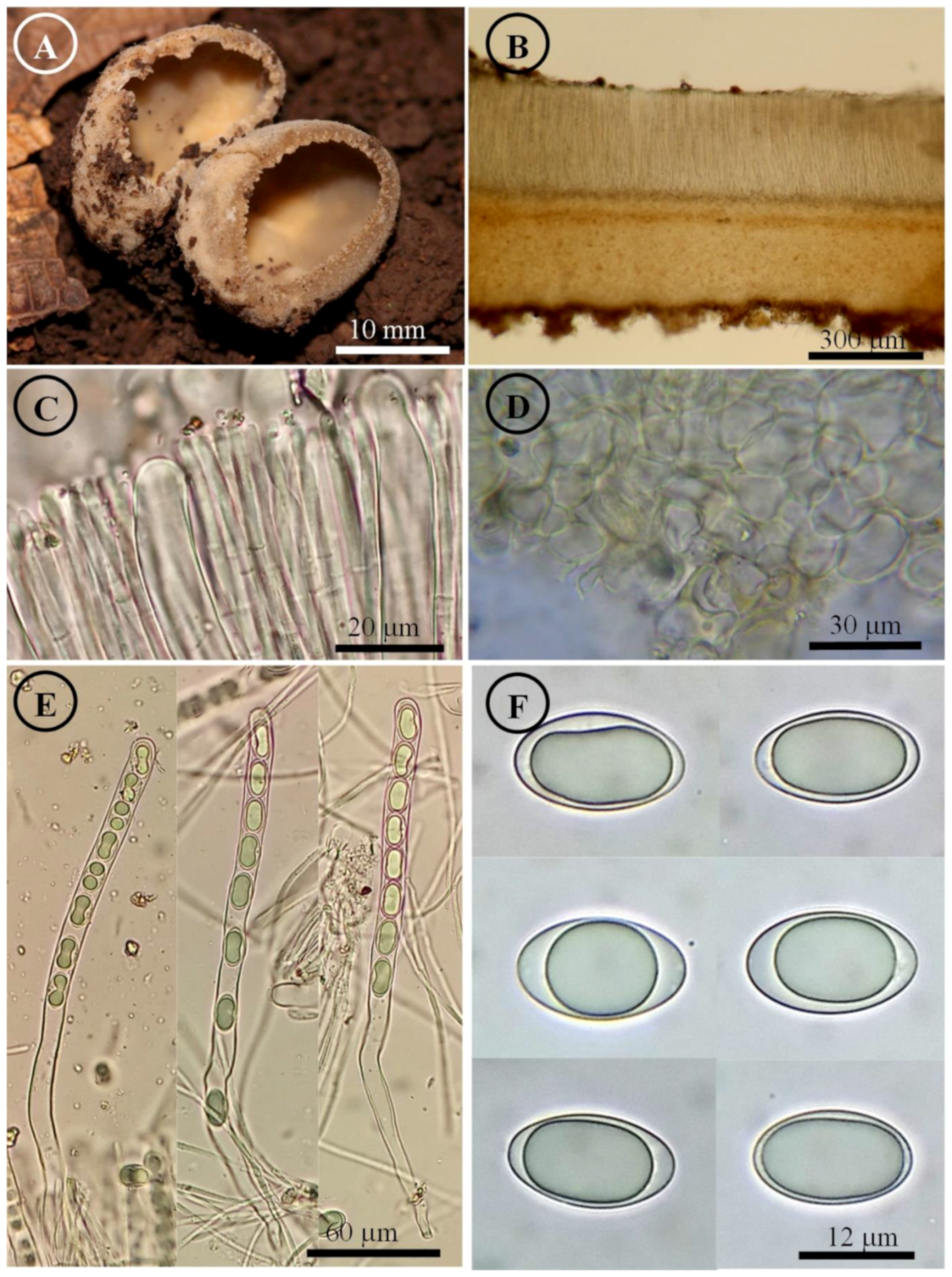

Figure 14.

Ascospores on OM. (A) Tarzetta americupularis; (B) T. cupressicola; (C) T. davidii; (D) T. durangensis; (E) T. mesophile; (F) T. mexicana; (G) T. miquihuanensis; (H) T. poblana; (I) T. pseudobronca; (J) T. texcocana; and (K,L) T. victoriana.

Figure 14.

Ascospores on OM. (A) Tarzetta americupularis; (B) T. cupressicola; (C) T. davidii; (D) T. durangensis; (E) T. mesophile; (F) T. mexicana; (G) T. miquihuanensis; (H) T. poblana; (I) T. pseudobronca; (J) T. texcocana; and (K,L) T. victoriana.

Habit: On soil, in Quercus spp. forest grown under Quercus rysophylla Weath and Q. polymorpha Schltdl. & Cham.

Distribution: MEXICO. It is only known from the state of Tamaulipas.

Material examined: Mexico, Tamaulipas state, Jaumave municipality, Sierra Madre, 8 November 2019, M. Sánchez 1862 (ITCV), 1863 (ITCV). Victoria municipality, Puerto El Paraíso community (23°31′38.99″ N, 99°12′20.04″ W), 1650 m asl, 17 October 2019, M. Sánchez 1754 (ITCV), 1768 (ITCV), 1773 (ITCV); loc. cit., 1 November 2019, M. Sánchez 1830 (ITCV), 1845 (ITCV); loc. cit., 21 November 2019, M. Sánchez 1923 (ITCV), 1928 (ITCV); loc. cit., 4 September 2020, M. Sánchez 2080 (ITCV); loc. cit., 13 September 2020, M. Sánchez 2100 (ITCV), 2115 (ITCV, ENCB, paratype; ITS: PP825408, LSU: PP825451), 2120 (ITCV); El Madroño, km 19 road Ciudad Victoria-Tula (23°36′16.32″ N, 99°13′45.20″ W), 1443 m asl, 11 November 2019, M. Sánchez 1883 (ITCV), 1896 (ITCV), 1898 (ITCV); Las Mulas, 26 August 2020, M. Sánchez 2075 (ITCV).

Notes: This species is characterized by forming small apothecia 2–25 mm in diameter and ellipsoid ascospores [17–20 × (9–) 10–11 µm]. The microscopic differences among T. pseudobronca, T. victoriana, and T. mexicana are the spore length and width; T. victoriana has the smallest and narrowest spores, while T. pseudobronca has the largest and widest spores (21–25 × 12–15 µm). T. mexicana has smaller and narrower ascospores (18–) 19–22 × 10–12 µm than T. pseudobronca.

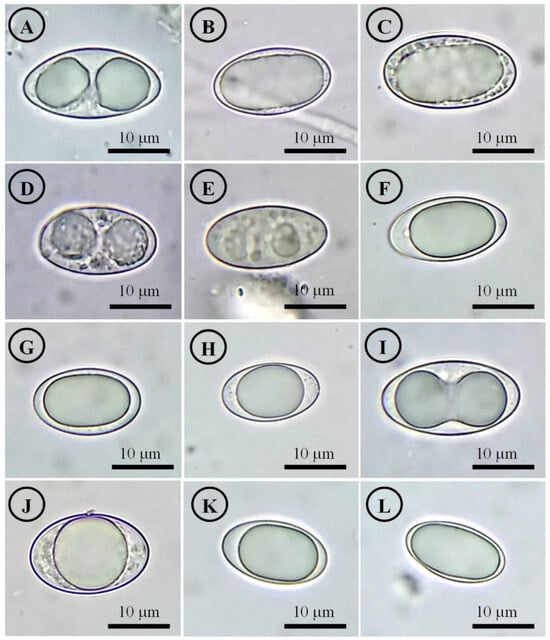

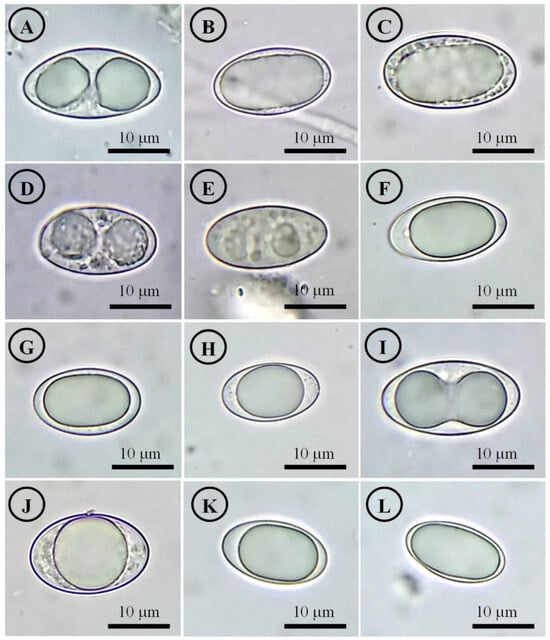

Figure 15.

Ascospores on SEM. (A) Tarzetta americupularis; (B) T. cupressicola; (C). T. davidii; (D) T. durangensis; (E) T. mesophila; and (F). T. mexicana.

Figure 15.

Ascospores on SEM. (A) Tarzetta americupularis; (B) T. cupressicola; (C). T. davidii; (D) T. durangensis; (E) T. mesophila; and (F). T. mexicana.

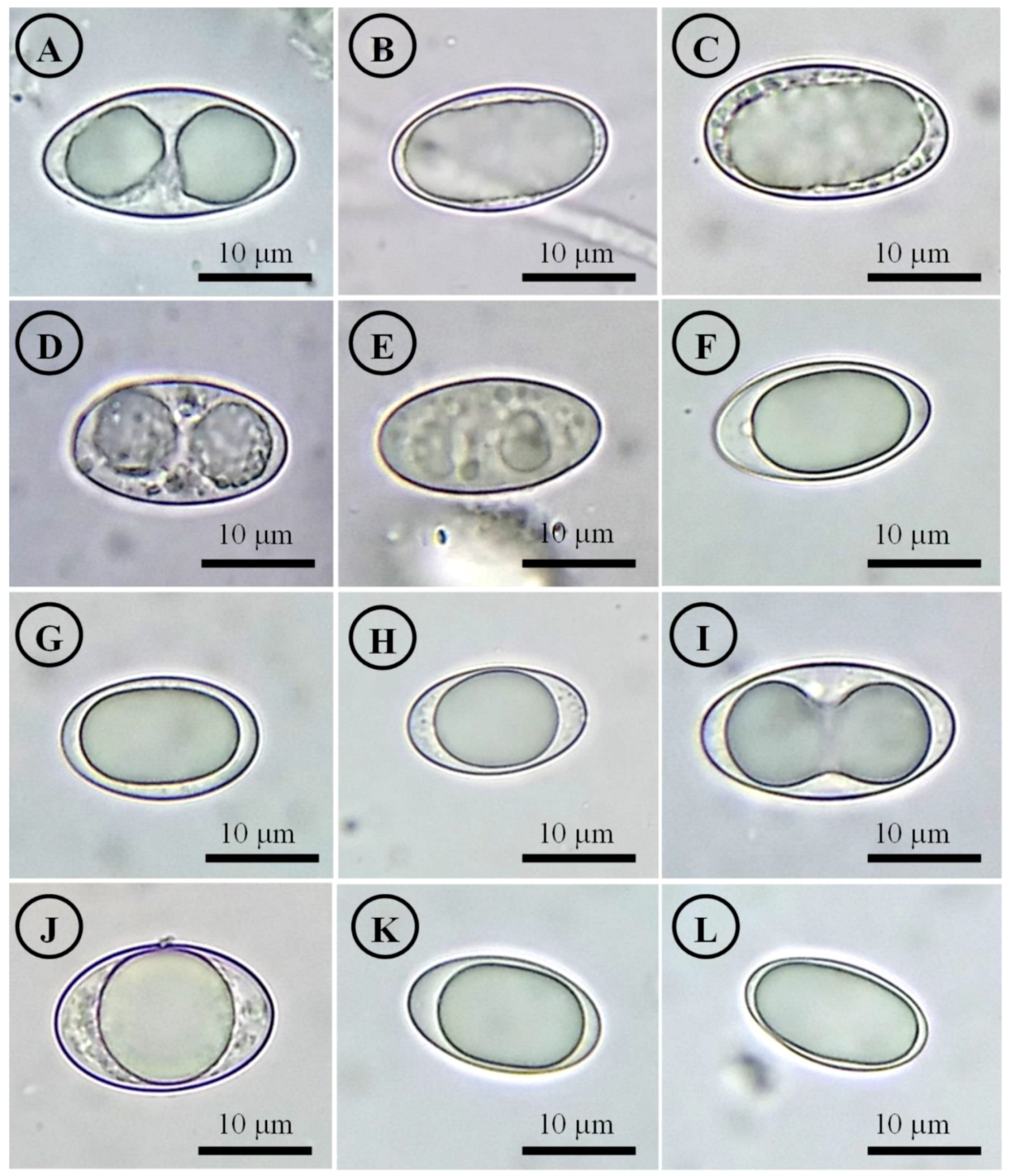

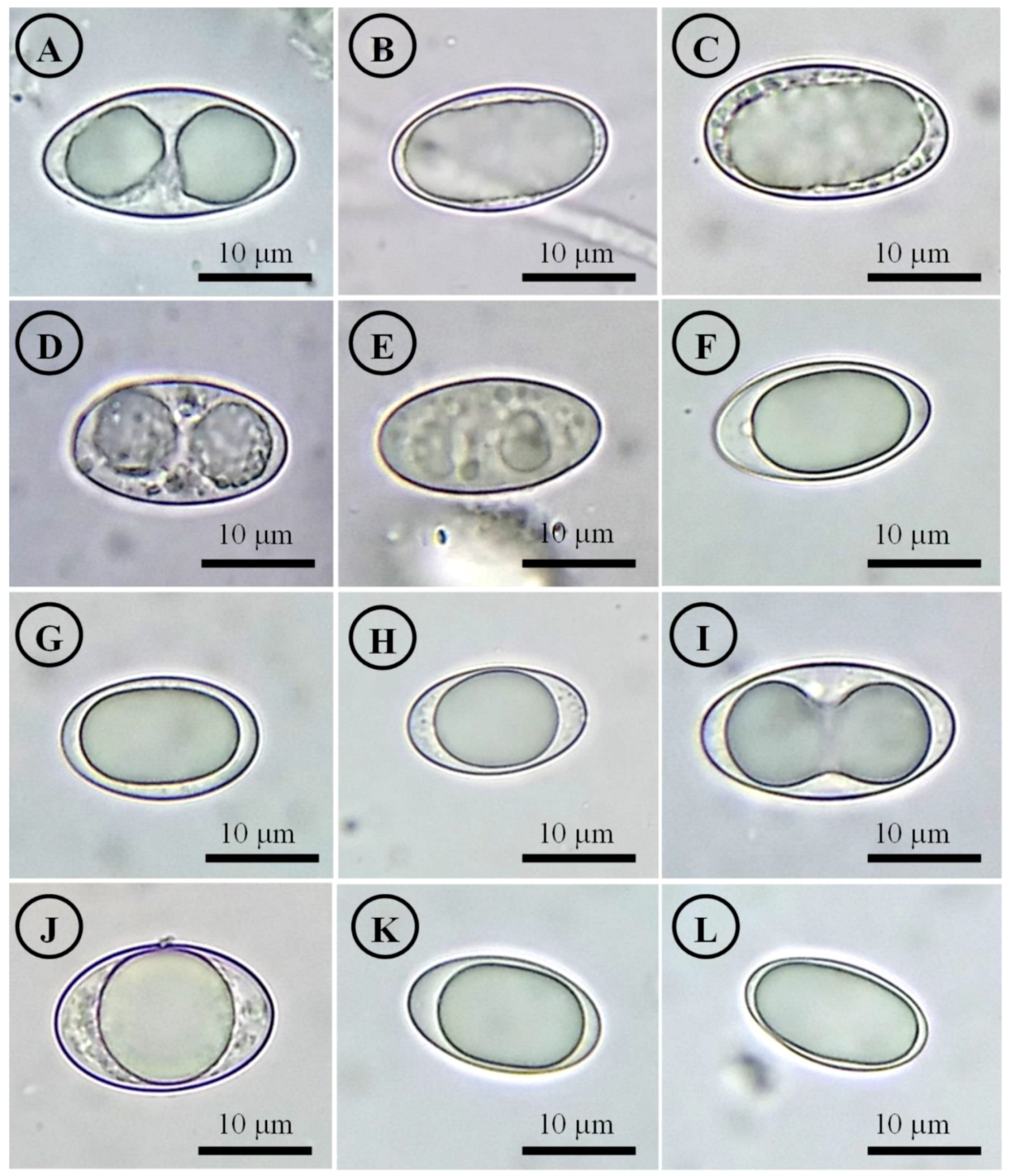

Figure 16.

Ascospores on SEM. (A) Tarzetta miquihuanensis; (B) T. poblana; (C) T. pseudobronca; (D) T. texcocana; and (E,F) T. victoriana.

Figure 16.

Ascospores on SEM. (A) Tarzetta miquihuanensis; (B) T. poblana; (C) T. pseudobronca; (D) T. texcocana; and (E,F) T. victoriana.

Table 2.

Comparison of Tarzetta species.

Table 2.

Comparison of Tarzetta species.

| Tarzetta | Country | Vegetation | Apothecia, Diameter, and Color | Margin and Edge of the Apothecia | Paraphysis | Asci | Ascospores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. americupularis Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez, R. Valenz. & Raymundo | México (This study) | Pinus-Quercus and coniferous forest | 4–8 mm diameter, cupuliform, greyish orange to pale orange color | Crenate | 2–4 µm, filiform, rounded to abrupt apex | 190–310 (–325) × 12–15 µm | (15–) 17–25 (–26) × 9–13 (–14) µm, ellipsoid to oblong, very finely rugose on SEM |

| T. bronca (Peck) Korf & J. K. Rogers | USA [39,40] | Not indicated | 10–35 mm diameter, cupuliform, deep olive beige to beige-yellow color. | Crenulated | Size not indicated, septate, simple, forked to branched, gnarled to claviform towards the apex | 250–350 × 12–16 µm | 20–24 × 12–14 µm, ellipsoid, smooth |

| T. catinus (Holmsk.) Korf & J. K. Rogers | England [41] | Not indicated | 40–50 mm diameter | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | (19.5–) 20–24 × 11–14 µm, ellipsoid, smooth |

| T. cupressicola Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez, Esqueda & Raymundo | Mexico (This study) | Mixed forest | 5–8 mm diameter, greyish brown to yellowish brown color | Sawn to slightly crenate | 2–3 µm, filiform, apex rounded, little septate, forked | 240–290 × 12–14 µm | 18–22 (–23) × 11–13 µm, ellipsoid, finely rugose on SEM |

| T. cupularis (L.) Lambotte | England [41] | Not indicated | <20 mm diameter | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | 21–25 (–26) × (12.5–) 13–15 µm, ellipsoid to broadly ellipsoid, smooth |

| T. davidii Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez & Raymundo | Mexico (This study) | Abies forest | 15–22 mm diameter, cupuliform, greyish brown to pale orange color | Crenate to dentate | 3–5 µm, filiform, deeply septate, apex rounded, with irregular protuberances. | 314–350 × 15–18 µm | (20–) 21–25 (–28) × 11–14 µm, ellipsoid to oblong, very finely rugose on SEM |

| T. durangensis Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez, R. Valenz. & Raymundo | Mexico (This study) | Pinus-Quercus forest | 4–5 mm diameter, cupuliform to discoid, light orange, greyish orange to orange color, with a pseudostipitate | Sawed | 3–4 µm, filiform, septate, slightly forked, apex rounded | 240–260 × 12–15 µm | 20–24 × 11–13 µm, oblong very finely rugose on SEM |

| T. mesophila Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez & Raymundo | Mexico (This study) | Tropical montane cloud forest | 5–9 mm diameter, cupuliform, greyish orange to light orange color | toothed to crenate | 3–4 µm, filiform, septate, apex rounded to rarely irregular | 248–300 × 12–15 µm | 19–25 (–26) × 10–12 µm, oblong to subcylindrical, very finely rugose on SEM |

| T. mexicana Sánchez-Flores, Raymundo, de la Fuente & García-Jiménez | México (This study) | Quercus-Pinus forest | 5–17 mm diameter, cupuliform, greyish orange to yellowish white color | erose to crenate | 2–3 µm, filiform, septate, slightly branched | 220–310 × 11–14 µm. | (18–) 19–22 × 10–12 µm, ellipsoid to oblong, finely rugose on SEM |

| T. miquihuanensis Sánchez-Flores, Raymundo, Hernández-Muñoz & García-Jiménez | México (This study) | Quercus-Pinus forest | 33–57 mm diameter, cupuliform, pale orange color | Entire to crenate | 2–5 µm, filiform, deeply septate, bifurcated | 225–335 × 9–13 µm. | (17–) 18–21 (–22) × 10–13 µm, ellipsoid, finely rugose on SEM |

| T. poblana Sánchez-Flores, Raymundo, Avila-Ortiz & García-Jiménez | Mexico (This study) | Pinus-Quercus and coniferous forest | 2–7 mm diameter, pale orange, cupuliform, brownish orange to yellowish white color | Involute, entire to crenate | 2–3 µm, filiform, septate, apex rounded | 170–205 × (11–) 13–15 µm | 16–22 × 9–12 (–13) µm, ellipsoid to oblong, very finely rugose on SEM |

| T. pseudobronca Sánchez-Flores, García-Jiménez, Martínez-González & Raymundo | México (This study) | Quercus-Pinus and Pinus cembroides forest | 13–18 mm diameter, cupuliform, greyish brown to light orange color, with a pseudostipitate | Entire to crenate | 3–6 µm, filiform, septate, branched, widening towards the apex | 215–250 × 13–15 µm | 21–25 × 12–15 µm, ellipsoid to oblong, very finely rugose on SEM |

| T. texcocana Sánchez-Flores | Mexico (This study) | Coniferous forest | 4–14 mm diameter, cupuliform, orange white, pale orange to greyish brown color | Entire to crenate | 3–4 µm, filiform, scarcely septate | 260–280 × 12–15 µm | 17–21 (–22) × 11–14 (–15) µm, broadly ellipsoid, finely rugose on SEM |

| T. victoriana Sánchez-Flores, Raymundo, Hernández-del Valle & García-Jiménez | México (This study) | Quercus spp. forest | 2–25 mm diameter, cupuliform, greyish orange, brownish orange, pale orange to brownish orange color, sessile to pseudostipitate | Crenate | 2–5 µm, filiform, septate, branched, with the apex slightly widened to irregular | 225–280 × 11–13 µm | 17–20 × (9–) 10–11 µm, ellipsoid, finely rugose on SEM |

Key to Tarzetta species from Mexico

| 1. Apothecia growing in coniferous or mixed forests in temperate regions | 2 |

| 1. Apothecia growing in Quercus forests or tropical montane cloud forests | 8 |

| 2. Apothecia growing in coniferous forests | 3 |

| 2. Apothecia growing in mixed forests | 5 |

| 3. Apothecia less than 10 mm with margin crenate, color salmon grown under Cupressus lusitanica | T. cupressicola |

| 3. Apothecia larger than 10 mm | 4 |

| 4. Apothecia associated with Pinus cembroides, excipule light brown | T. pseudobronca |

| 4. Apothecia associated with Abies religiosa, excipule greyish brown warty | T. davidii |

| 5. Apothecia with external surface warty | 6 |

| 5. Apothecia with external surface asperulate | 7 |

| 6. Apothecia color pale orange margin entire, involute to crenate, ascospores 16–22 × 9–12 (–13) µm, ellipsoid-oblong | T. poblana |

| 6. Apothecia color greyish orange with margin crenate, ascospores 17–21 (–22) × 11–14 (–15) µm, broadly ellipsoid | T. texcocana |

| 7. Apothecia substipitate, ascospores 20–24 × 11–13 µm, oblong with blunt ends | T. durangensis |

| 7. Apothecia sessile, ascospores (15–) 17–25 (–26) × 9–13 (–14) µm, ellipsoid to oblong with acute ends | T. americupularis |

| 8. Apothecia growing in tropical montane cloud forest, ascospores 19–25 (–26) × 10–12 µm, subcylindrical | T. mesophila |

| 8. Apothecia growing in Quercus forests, ascospores ellipsoid | 9 |

| 9. Apothecia larger than 30 mm, margin entire to crenate | T. miquihuanensis |

| 9. Apothecia small, less than 25 mm, margin crenate to eroded | 10 |

| 10. Apothecia substipitate, color pale orange, margin involute crenate, associated with Quercus rysophylla and Q. polymorpha | T. victoriana |

| 10. Apothecia sessile, color orange-gray to whitish, margin eroded, associated with several species of Quercus | T. mexicana |

4. Discussion

In this study, 11 species of Tarzetta are described from Mexico, based on ecological, morphological, and molecular data. Combined analyses of two datasets (ITS and LSU) showed two strongly supported clades described as follows: Clade I, with most of the species growing on the Sierra Madre Oriental, is mainly associated with Quercus species, except T. davidii, which is putatively associated with Abies religiosa at least within the Transversal Neovolcanic Axis [42]. Species of this clade show paraphyses generally slightly branched, filiform, and septate. Clade II, with most of the species growing on the Sierra Madre Occidental, is associated with conifers; T. texcocana and T. pseudobronca seem to be the exception, where the former may be associated with Quercus species, while the second associated with Pinus cembroides. Most of the species of this clade have paraphyses bifurcate with few septa; nevertheless, T. pseudobronca can show branched paraphysis.

According to Van Vooren et al. [7], the main diagnostic characteristics for the description of Tarzetta species are the size of the ascoma and ascospores, as well as the host. In this work, two clades are observed, separated mainly by the paraphyses structure. Van Vooren et al. [7] considered this character of little taxonomic value because the apical area of the paraphyses seems to be highly variable in the same species, depending on the development stage of the area where the observations are made. However, there is a tendency for Mexican species to group, according to this character, although it is not consistent. According to the host, a marked separation of the clades is observed, with the species of Clades I and II mostly associated with conifers and Quercus species, respectively. In the case of T. cupressicola, this species grows under Cupressus lusitanica; however, there is no evidence that it is directly associated with mycorrhiza.

Although most species of this genus have been described and cited with smooth spores, except J. jafneospora with verrucose ascospores [7,9,39], all Mexican species seen in OM are smooth but under SEM they show finely rugose ornamentation (Figure 14 and Figure 15). Likewise, it is suggested to carefully review European and American species under SEM to confirm the smooth ascospores.

5. Conclusions

Our results obtained in this study confirm that T. catinus and T. cupularis are not distributed in the American continent and they are restricted to Europe, as mentioned by Van Vooren et al. [6]. Therefore, it is inferred that the genus Tarzetta is an open field with more taxa for the American continent, waiting to be described. In the case of T. brasiliensis and T. microspora, these taxa must be reviewed due to the lack of information, and their taxonomic position must also be validated. Tarzetta species are ectomycorrhizal, where the species described in our study are mainly associated with Abies, Pinus, and Quercus in the temperate forests of Mexico, showing finely rugose ascospores and ornamentation not previously reported in the genus.

Author Contributions

M.S.-F. conceived this study, contributed to field work, photographs, described the new species, taxonomic key, reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.G.-J. conceived this study, contributed to field work, photographs, reviewed and edited the manuscript. T.R. conceived this study, contributed to field work, taxonomic key, reviewed and edited the manuscript. C.R.M.-G. helped with the phylogenetic analyses, reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.F.H.-D.V. contributed to field work, reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.A.H.-M. contributed to field work, reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.I.d.l.F. contributed to field, taxonomic key, reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.E. contributed to field work, photographs, reviewed and edited the manuscript. A.Á.O. contributed to field work, reviewed and edited the manuscript. R.V. contributed to field work, photographs, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

M.S.-F., J.F.H.-V. and J.I.d.l.F. thank CONAHCYT for the financial support. A.Á.O. and M.A.H.-M. thank the project UNAM-DGAPA-PAPIME PE207819. M.S.-F., J.G.-J., C.R.M.-G. and J.F.H.-V. thank Tecnológico Nacional de México-Instituto Tecnológico de Ciudad Victoria. J.G.-J., T.R., M.E. and R.V. thank SNI for the financial support. T.R. and R.V. are grateful to COFAA and IPN-SIP for the financial support for their projects SIP20230017; SIP-20230642; SIP20240029; and SIP20240367.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All newly generated sequences were deposited in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/ (accessed on 25 January 2024)).

Acknowledgments

M.S.-F. thanks María Mercedes Rodríguez Palma for the logistical assistance at Estación Científica La Malinche. All authors thank María Berenit Mendoza Garfias, from the Laboratorio de Microscopia y Fotografía de la Biodiversidad 1 (LaNaBio, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), for the photographs and SEM of ascospores, Laura Márquez and Nelly López (LaNaBio, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) for sequencing the PCR products, Sigrid Cazares for technichal support, and Aldo Gutiérrez for the support with the template.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ekanayaka, A.H.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G.; Zhao, Q. Taxonomy and phylogeny of operculate discomycetes: Pezizomycetes. Fungal Divers. 2018, 90, 161–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B.A.; Hansen, K.; Pfister, D.H. A phylogenetic overview of the family Pyronemataceae (Ascomycota, Pezizales). Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 549–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, K.; Perry, B.A.; Dranginis, A.W.; Pfister, D.H. A phylogeny of the highly diverse cup-fungus family Pyronemataceae (Pezizomycetes, Ascomycota) clarifies relationships and evolution of selected life history traits. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2013, 67, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, L.M.; Smith, M.E.; Nouhra, E.R.; Orihara, T.; Sandoval Leyva, P.; Pfister, D.H.; McLaughlin, D.J.; Trappe, J.M.; Healy, R.A. A molecular and morphological re-examination of the generic limits of truffles in the Tarzetta-Geopyxis linage—Densocaropa, Hydnocystis and Paurocotylis. Fungal Biol. 2017, 121, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis; Academic Press: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tedersoo, L.; May, T.W.; Smith, M.E. Ectomycorrhizal lifestyle in fungi: Global diversity, distribution, and evolution of phylogenetic lineages. Mycorrhiza 2010, 20, 217–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Vooren, N.; Carbone, M.; Sammut, C.; Grupe, A.C. Preliminary notes on the genus Tarzetta (Pezizales) with typifications of some species and description of six new species. Ascomycete.org 2019, 11, 309–334. [Google Scholar]

- Beug, M.; Bessette, A.E.; Bessette, A.R. Ascomycete Fungi of North America a Mushroom Reference Guide; University of Texas Press: Texas, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, M.; Saitta, S.; Sánchez, L.; García Blanco, A.; Van Vooren, N. Tarzetta oblongispora (Pezizales, Tarzettaceae), a new species from the Mediterranean basin, a new records of Tarzetta based on an updated phylogeny. Ascomycete.org 2023, 15, 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, K.D.; Suwannarach, N.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Manawasinghe, I.S.; Liao, C.F.; Doilom, M.; Cai, L.; Zhao, P.; Buyck, B.; Phukhamsakda, C.; et al. Mycosphere notes 325–344—Novel species and records of fungal taxa from around the world. Mycosphere 2021, 12, 1101–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, I.C.; Rossi, W.; Leonardi, W.; Weir, A.; McHugh, M.; Rajeshkumar, K.C.; Verma, R.J.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Tibpromma, S.; Ashtekar, N.; et al. Fungal Diversity notes 1611–1716: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions on fungal genera and species emphasis in south China. Fungal Divers. 2023, 122, 161–403. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, G. Identificación de los Hongos Comestibles, Venenosos, Alucinantes y Destructores de la Madera; Limusa: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez del Mercado, N.M. Estudio Sobre los Hongos del Grupo de los Pezizales, Principalmente de los Estados de Veracruz y Oaxaca. Bachelor’s Thesis, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Ciudad de México, Mexico, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mapes, C.; Guzmán, G.; Caballero, J. Etnomicología Purépecha. El Conocimiento y uso de los Hongos en la Cuenca de Pátzcuaro. Dirección General de Cultura Popular, Serie Etnociencia, Cuadernos de Etnomicología 2; Sociedad Mexicana de Micología e Instituto de Biología Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Zarco, J.F. Contribución al Conocimiento de la Distribución ecológica de los Hongos, Principalmente Macromicetos, del Valle de México. Bachelor’s Thesis, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Ciudad de México, Mexico, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Chacón, S.; Guzmán, G. Especies de macromicetos citadas de México, V. Ascomycetes, parte II. Bol. Soc. Mex. Micol. 1983, 18, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Villarruel-Ordaz, J.; Cifuentes, J. Macromicetos de la Cuenca del Río Magdalena y zonas adyacentes, Delegación la Magdalena Contreras, México, D.F. Rev. Mex. Micol. 2007, 25, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Raymundo, T.; Díaz-Moreno, R.; Bautista-Hernández, S.; Aguirre-Acosta, E.; Valenzuela, R. Diversidad de ascomicetes macroscópicos en Bosque Las Bayas, municipio de Pueblo Nuevo, Durango, México. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2012, 83, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymundo, T.; Aguirre-Acosta, E.; Bautista-Hernández, S.; Contreras-Pacheco, M.; Garma, P.; León-Avendaño, H.; Valenzuela, R. Catálogo de los Ascomycota en los bosques de Santa Martha Latuvi, Sierra Norte, Oaxaca, México. Boletín Soc. Micológica Madr. 2013, 37, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa, M.; Hanlin, R.T. Nuevo Diccionario Ilustrado de Micología; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kornerup, A.; Wanscher, J.H. Methuen Handbook of Colour; Eyre Methuen: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-González, C.R.; Ramírez-Mendoza, R.; Jiménez-Ramírez, J.; Gallegos-Vázquez, C.; Luna-Vega, I. Improved method for genomic DNA extraction for Opuntia Mill. (Cactaceae). Plant Methods 2017, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.D.; Lee, S.B.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 135–322. [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 72, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Schwarts, S.; Wagner, L.; Miller, W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J. Comput. Biol. 2000, 7, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, R.A.; Arnold, A.E.; Bonito, G.; Huang, Y.L.; Lemmond, B.; Pfister, D.H.; Smith, M.E. Endophytism and endolichenism in Pezizomycetes: The exception or the rule. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 1974–1983. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2017, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Quandt, D.; Müller, J.; Neinhuis, C. PhyDE®-Phylogenetic Data Editor. Program Distributed by the Authors, ver. 10.0. 2005. Available online: https://www.phyde.de (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Swofford, D.L. PAUP* Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (and Other Methods); Version 4.0b10; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F. MrBayes: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfear, R.; Calcott, B.; Kainer, D.; Mayer, C.; Stamatakis, A. Selecting optimal partitioning schemes for phylogenomic datasets. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frandsen, P.B.; Calcott, B.; Mayer, C.; Lanfear, R. Automatic selection of partitioning schemes for phylogenetic analyses using iterative k-means clustering of site rates. BMC Evol. Biol. 2015, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanfear, R.; Frandsen, P.B.; Wright, A.M.; Senfeld, T.; Calcott, B. Partition Finder 2: New methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 772–773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A. FigTree v.1.4.2. A Graphical Viewer of Phylogenetic Trees. 2014. Available online: https://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/sofware/figtree (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Kanouse, B.B. A study of Peziza bronca Peck. Mycologia 1950, 42, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korf, R.P. Some new discomycete names. Phytologia 1971, 21, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.-J.; Spooner, B.M. Notes on British species of Tarzetta (Pezizales). Mycol. Res. 2002, 106, 1243–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Miranda, R.; Romero-Sánchez, M.E.; González-Hernández, A.; Pérez-Sosa, E.; Flores-Ayala, E. Distribución del Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. & Cham. bajo escenarios de cambio climático en el Eje Neovolcánico, México. Agroproductividad 2017, 10, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).