Host Developmental Stage and Vegetation Type Govern Root EcM Fungal Assembly in Temperate Forests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Design

2.2. Sampling and Molecular Analysis

2.3. PCR Amplification and Illumina Sequencing

2.4. Sequence Processing

2.5. Statistical Analyses

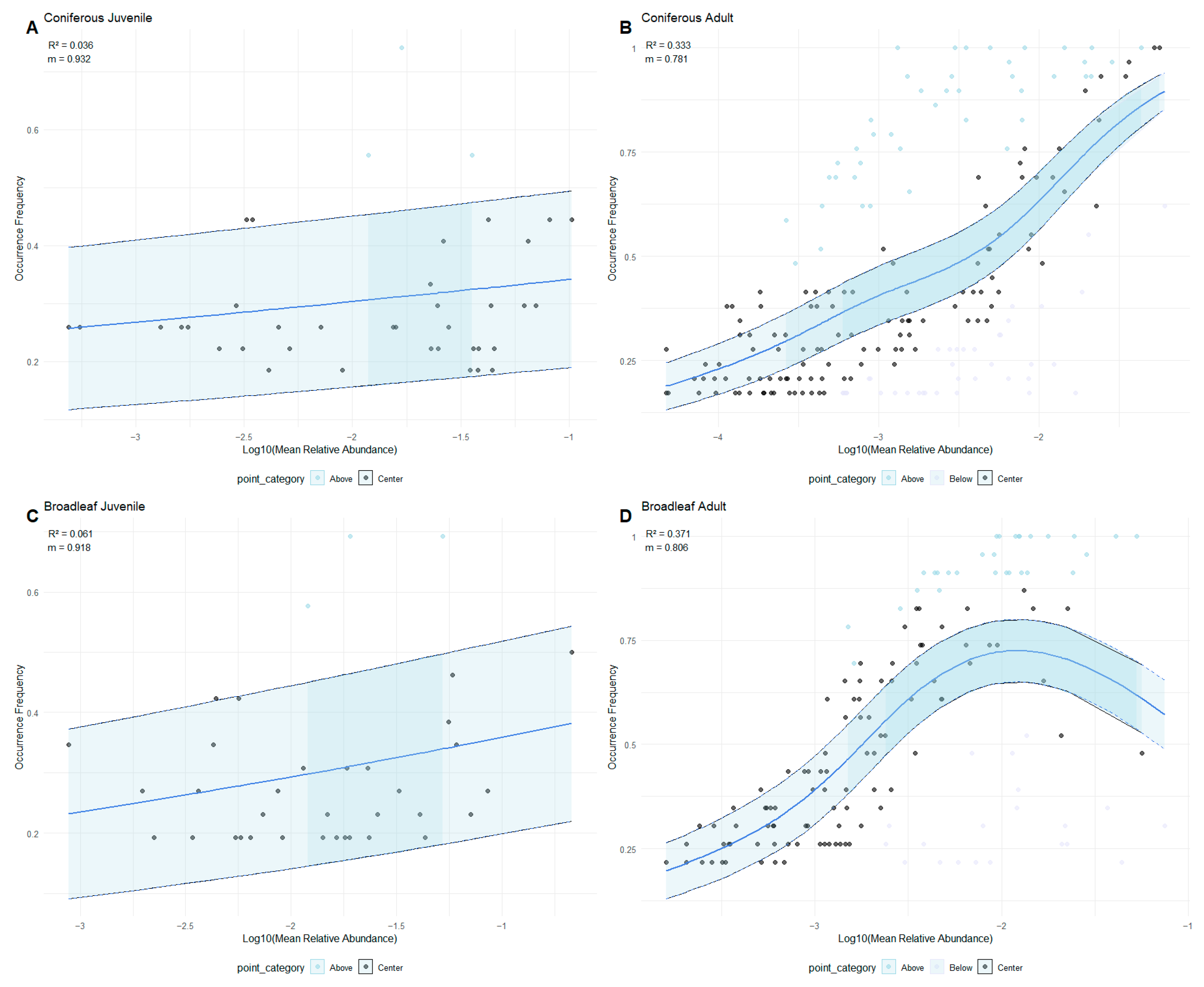

- High m values (m→1) indicate strong mismatch between observed and neutral expectations, reflecting increased migration rates or greater dynamic variability in species distribution.

- Low m values (m→0) suggest closer alignment with neutral predictions, implying a increased dispersal limitation.

3. Results

3.1. Neutral Processes Dominated More in Adults than Juveniles, Modulated by Host Identity

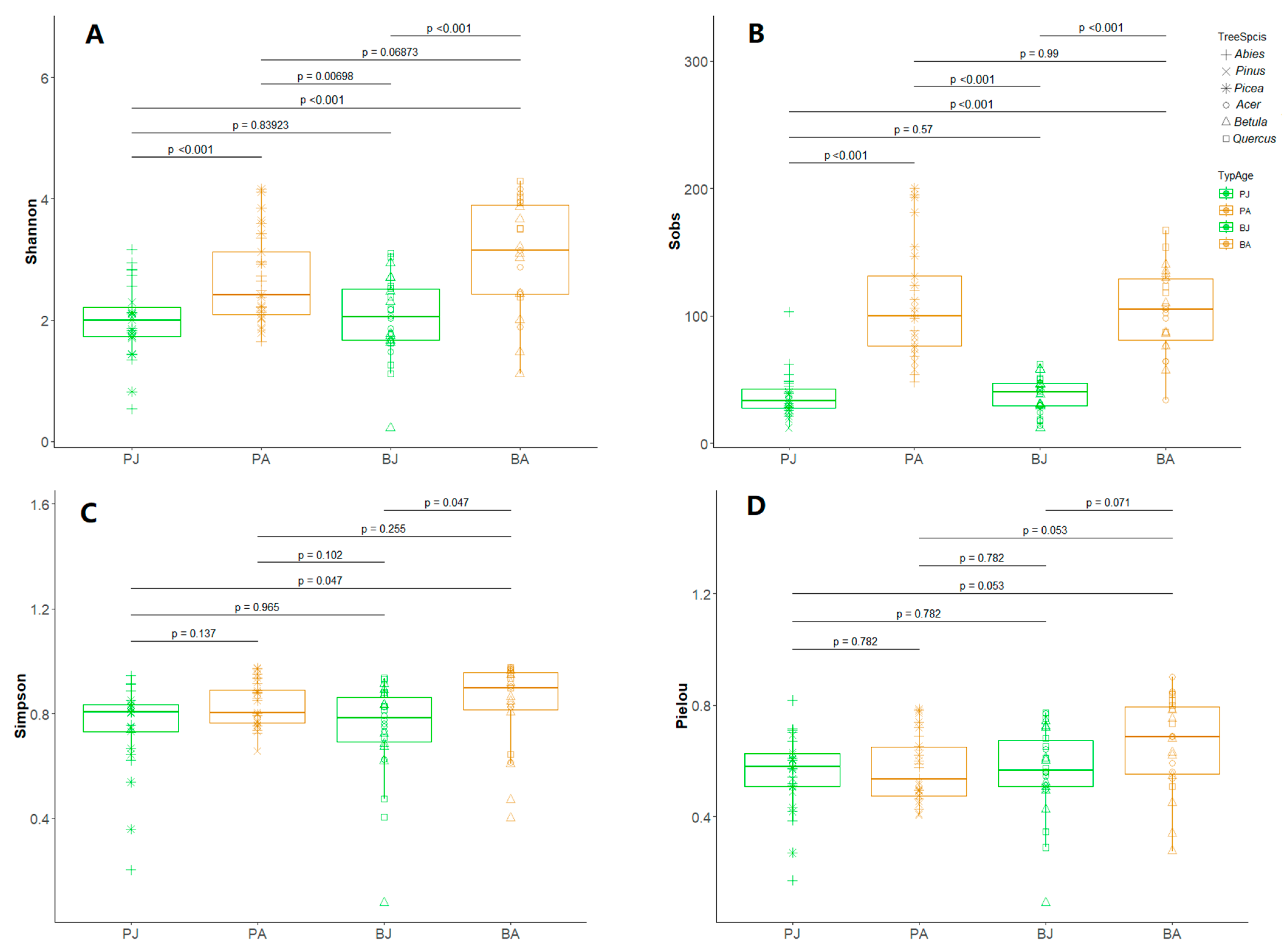

3.2. Alpha Diversity Increased with Host Maturity, Moderated by Host Identity

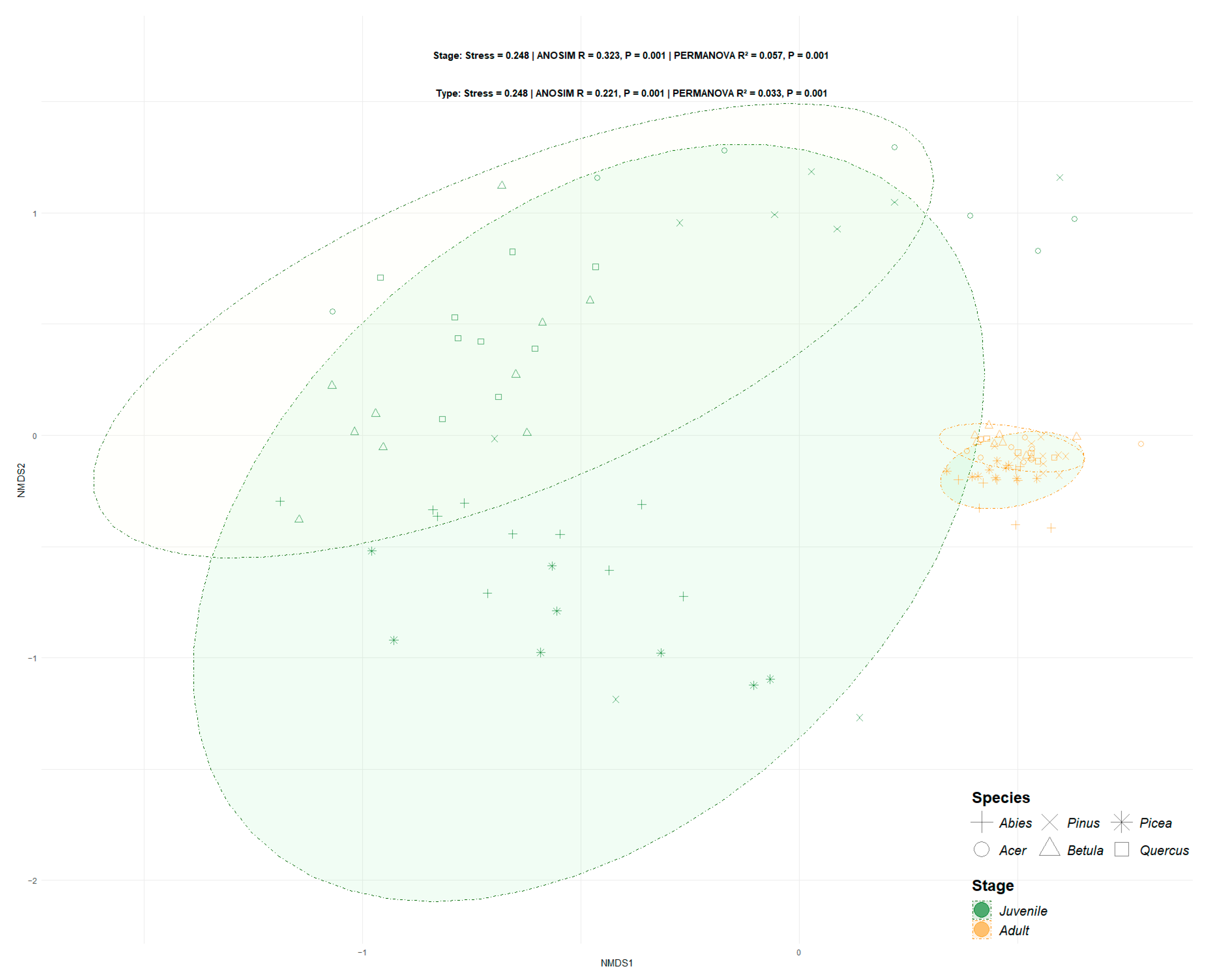

3.3. Beta Diversity Varied with Host Maturity and Species Identity

3.4. Stage-Specific Fungal Taxa

3.5. Host-Specific Fungal Taxa

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, D.X.; Bai, Z.; Yuan, Y.W.; Li, S.A.; Wei, Y.L.; Yuan, H.S. Ectomycorrhizal fungal community varies across broadleaf species and developmental stages. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg-Felten, J.; Martin, F.; Legue, V. Signalling in ectomycorrhizal symbiosis. Signal. Commun. Plants 2011, 11, 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Brundrett, M.C.; Tedersoo, L. Evolutionary history of mycorrhizal symbioses and global host plant diversity. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clasen, B.; Silveira, A.; Baldoni, D.; Fiuza Montagner, D.; Jacques, R.; Antoniolli, Z. Characterization of ectomycorrhizal species through molecular biology tools and morphotyping. Sci. Agric. 2018, 75, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Li, X.Z.; Kou, Y.P. Ectomycorrhizal fungi: Participation in nutrient turnover and community assembly pattern in forest ecosystems. Forests 2020, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, N.N.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, L.; Wubet, T.; Bruelheide, H.; Both, S.; Buscot, F.; Ding, Q.; et al. Community assembly of ectomycorrhizal fungi along a subtropical secondary forest succession. New Phytol. 2014, 205, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, P.S.; Gao, G.L.; Ren, Y.; Ding, G.D.; Zhang, Y. Niche differentiation shapes the community assembly of fungi associated with evergreen trees in the Horqin desert. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 204, 105739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Ye, J.; Liu, S.F.; Sun, H.H.; Yuan, Z.Q.; Mao, Z.K.; Fang, S.; Long, S.F.; Wang, X.G. Age-related conservation in plant-soil feedback accompanied by ectomycorrhizal domination in temperate forests in northeast China. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbrell, A.J.; Nelson, M.; Helgason, T.; Dytham, C.; Fitter, A.H. Relative roles of niche and neutral processes in structuring a soil microbial community. ISME J. 2010, 4, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegen, J.C.; Lin, X.J.; Fredrickson, J.K.; Chen, X.Y.; Kennedy, D.W.; Murray, C.J.; Rockhold, M.L.; Konopka, A. Quantifying community assembly processes and identifying features that impose them. ISME J. 2013, 7, 2069–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Chen, X.; Wei, K.Y.; Wu, R.; Wang, G. Stochastic and deterministic assembly processes of bacterial communities in different soil aggregates. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 193, 105153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.D.; Liu, W.J.; Li, X.; Feng, Y.Z. The ecology of microbiome on cultural relics: The linkage of assembly, composition and biodeterioration. J. Cult. Herit. 2025, 71, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Yang, L.; Mao, S.L.; Fan, M.C.; Shangguan, Z.P. Assembly and enrichment of rhizosphere and bulk soil microbiomes in Robinia pseudoacacia plantations during long-term vegetation restoration. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 187, 104835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroenyane, I.; Mendes, L.; Tremblay, J.; Tripathi, B.; Yergeau, É. Plant compartments and developmental stages modulate the balance between niche-based and neutral processes in soybean microbiome. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 82, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Turner, B.L. Ecological succession in a changing world. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerz, M.; Guillermo Bueno, C.; Ozinga, W.A.; Zobel, M.; Moora, M. Niche differentiation and expansion of plant species are associated with mycorrhizal symbiosis. J. Ecol. 2018, 106, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.W.; Gao, C.; Chen, L.; Buscot, F.; Goldmann, K.; Purahong, W.; Ji, N.N.; Wang, Y.L.; Lü, P.P.; Li, X.C.; et al. Host phylogeny is a major determinant of Fagaceae-associated ectomycorrhizal fungal community assembly at a regional scale. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linde, S.; Suz, L.M.; Orme, C.D.L.; Cox, F.; Andreae, H.; Asi, E.; Atkinson, B.; Benham, S.; Carroll, C.; Cools, N.; et al. Environment and host as large-scale controls of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Nature 2018, 558, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidt, H.; Wu, Y.T.; Wubet, T.; Trogisch, S.; Both, S.; Scholten, T.; Bruelheide, H.; Buscot, F. Forest age and plant species composition determine the soil fungal community composition in a Chinese subtropical forest. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66829. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.L.; Gao, C.; Chen, L.; Ji, N.N.; Wu, B.W.; Li, X.C.; Lü, P.P.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, L.D. Host plant phylogeny and geographic distance strongly structure Betulaceae-associated ectomycorrhizal fungal communities in Chinese secondary forest ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95, fiz037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, T.W.; Aime, M.C.; Chin, M.M.; Miller, S.L.; Vilgalys, R.; Smith, M.E. Ectomycorrhizal fungal sporocarp diversity and discovery of new taxa in Dicymbe monodominant forests of the Guiana Shield. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 2195–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.H.; Mi, X.C.; Liu, C.R.; Ma, K.P. Spatial patterns and associations in a Quercus-Betula forest in northern China. J. Veg. Sci. 2004, 15, 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Kałucka, I.L.; Jagodziński, A.M. Ectomycorrhizal fungi: A major player in early succession. In Mycorrhiza—Function, Diversity, State of the Art; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 187–229. [Google Scholar]

- Furniss, T.J.; Larson, A.J.; Lutz, J.A. Reconciling niches and neutrality in a subalpine temperate forest. Ecosphere 2017, 8, e01847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabot, F.; Etienne, R.S.; Chave, J. Reconciling neutral community models and environmental filtering: Theory and an empirical test. Oikos 2008, 117, 1308–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twieg, B.D.; Durall, D.M.; Simard, S.W. Ectomycorrhizal fungal succession in mixed temperate forests. New Phytol. 2007, 176, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.Q.; Wang, X.H.; Howard, M.M.; Kou, Y.P.; Liu, Q. Functional shifts in soil fungal communities regulate differential tree species establishment during subalpine forest succession. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 861, 160616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, N.; Liu, X.X.; Kotze, D.J.; Jumpponen, A.; Francini, G.; Setälä, H. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities in urban parks are similar to those in natural forests but shaped by vegetation and park age. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01797-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Yuan, Z.Q.; Wang, D.M.; Fang, S.; Ye, J.; Wang, X.G.; Yuan, H.S. Ectomycorrhizal fungus-associated determinants jointly reflect ecological processes in a temperature broad-leaved mixed forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 135475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aponte, C.; García, L.V.; Marañón, T.; Gardes, M. Indirect host effect on ectomycorrhizal fungi: Leaf fall and litter quality explain changes in fungal communities on the roots of co-occurring Mediterranean oaks. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.R.; Wang, J.X.; Shi, Z.M.; Xu, J.; Hong, P.Z.; Ming, A.G.; Yu, H.L.; Chen, L.; Lu, L.H.; et al. Differential effects of conifer and broadleaf litter inputs on soil organic carbon chemical composition through altered soil microbial community composition. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.R.; Wang, J.X.; Shi, Z.M.; Lu, L.H.; Guo, W.F.; Jia, H.Y.; Cai, D.X. Dynamics and speciation of organic carbon during decomposition of leaf litter and fine roots in four subtropical plantations of China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 300, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Wang, R.; Lu, B.; Guerin-Laguette, A.; He, X.H.; Yu, F.Q. Mycorrhization of Quercus mongolica seedlings by Tuber melanosporum alters root carbon exudation and rhizosphere bacterial communities. Plant Soil 2021, 467, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.P.; Ding, J.X.; Yin, H.J. Temperature governs the community assembly of root-associated ectomycorrhizal fungi in alpine forests on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 176820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinnage, R.; Simonsen, A.K.; Barrett, L.G.; Cardillo, M.; Raisbeck-Brown, N.; Thrall, P.H.; Prober, S.M. Larger plants promote a greater diversity of symbiotic nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria associated with an Australian endemic legume. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Taniguchi, T.; Xu, M.; Du, S.; Liu, G.B.; Yamanaka, N. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities of Quercus liaotungensis along different successional stands on the Loess Plateau, China. J. For. Res. 2014, 19, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Qu, T.T.; Song, H.H.; Sun, Z.Z.; Zeng, H.; Peng, S.S. Ectomycorrhizal fungi respiration quantification and drivers in three differently-aged larch plantations. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 265, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Anslan, S.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Riit, T.; Liiv, I.; Kõljalg, U.; Kisand, V.; Nilsson, H.; Hildebrand, F. Shotgun metagenomes and multiple primer pair-barcode combinations of amplicons reveal biases in metabarcoding analyses of fungi. Mycokeys 2015, 10, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõljalg, U.; Nilsson, R.H.; Abarenkov, K.; Tedersoo, L.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Bahram, M.; Bates, S.T.; Bruns, T.D.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Callaghan, T.M.; et al. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 5271–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geml, J.; Leal, C.M.; Nagy, R.; Sulyok, J. Abiotic environmental factors drive the diversity, compositional dynamics and habitat preference of ectomycorrhizal fungi in Pannonian forest types. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1007935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Põlme, S.; Abarenkov, K.; Henrik Nilsson, R.; Lindahl, B.D.; Clemmensen, K.E.; Kauserud, H.; Nguyen, N.; Kjøller, R.; Bates, S.T.; Baldrian, P. FungalTraits: A user-friendly traits database of fungi and fungus-like stramenopiles. Fungal Divers. 2020, 105, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.; Liu, P.; Zhou, G.Y.; Xia, J.G. Using MicrobiomeAnalyst for comprehensive statistical, functional, and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 799–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, J.D.; Lutz, J.A.; Turner, B.L.; Karst, J. Divergent, age-associated fungal communities of Pinus flexilis and Pinus longaeva. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 494, 119277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, D.L.; Yuan, M.T.; Wu, L.W.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhou, X.S.; Yang, Y.F.; Arkin, A.P.; Firestone, M.K.; Zhou, J.Z. A quantitative framework reveals ecological drivers of grassland microbial community assembly in response to warming. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.; Solymos, P. Vegan: Community Ecology Package R Package Version 2.5-7; Vegan: Danvers, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Givaudan, N.; Suchail, S.; Rault, M.; Mouneyrac, C.; Capowiez, Y. Impact of apple orchard management strategies on earthworm (Allolobophora chlorotica) energy reserves. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 100, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nérée, O.; Kuyper, T. Importance of the ectomycorrhizal network for seedling survival and ectomycorrhiza formation in rain forests of south Cameroon. Mycorrhiza 2002, 12, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- García de Jalón, L.; Limousin, J.M.; Richard, F.; Gessler, A.; Peter, M.; Hättenschwiler, S.; Milcu, A. Microhabitat and ectomycorrhizal effects on the establishment, growth and survival of Quercus ilex L. seedlings under drought. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbell, S.P. The unified neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography (MPB-32). In Monographs in Population Biology; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.J.; Ning, H.L.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.C.; Shen, Q.R.; Ling, N.; Guo, S.W. Assemblages of rhizospheric and root endospheric mycobiota and their ecological associations with functional traits of rice. mBio 2024, 15, e02733-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara, K.; Nakaya, H.; Wu, B.Y.; Zhou, Z.H.; Hogetsu, T. Underground primary succession of ectomycorrhizal fungi in a volcanic desert on Mount Fuji. New Phytol. 2003, 159, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weißbecker, C.; Wubet, T.; Lentendu, G.; Kühn, P.; Scholten, T.; Bruelheide, H.; Buscot, F. Experimental evidence of functional group-dependent effects of tree diversity on soil fungi in subtropical forests. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Babalola, B.J.; Xiang, S.; Ma, J.; Su, Y.; Fan, Y. Stochastic processes dominate community assembly of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Picea crassifolia in the Helan Mountains, China. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1061819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Babalola, B.J.; Xiang, S.M.; Zhao, Y.L.; Fan, Y.J. Fungal diversity and community assembly of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with five pine species in Inner Mongolia, China. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 646821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumin, R.; Wang, D.D.; Zhao, W.; Huang, K.C.; Li, J.N.; Sun, Y.F.; Cui, B.K. Spatial distribution patterns and assembly processes of abundant and rare fungal communities in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica forests. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz, A.M.; Rożek, K.; Stanek, M.; Rola, K.; Zubek, S. Moderate effects of tree species identity on soil microbial communities and soil chemical properties in a common garden experiment. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 482, 118799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, B.Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.H.; Wang, Y.; Han, F.P. Rhizosphere soil metabolites mediated microbial community changes of Pinus sylvestris var mongolica across stand ages in the Mu Us Desert. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 169, 104222. [Google Scholar]

- Nara, K. Ectomycorrhizal networks and seedling establishment during early primary succession. New Phytol. 2006, 169, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.H.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Liu, H.J.; Xiong, W.; Deng, X.H.; Zhang, N.; Li, R.; Shen, Q.R.; Dini-Andreote, F. Microbial community assembly in soil aggregates: A dynamic interplay of stochastic and deterministic processes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 163, 103911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.J.; David, A.S.; Menges, E.S.; Searcy, C.A.; Afkhami, M.E. Environmental stress destabilizes microbial networks. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, P. Responses of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi to Changes in Carbon and Nutrient Availability; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Upsala, Sweden, 2001; ISBN 91-576-6319-X. [Google Scholar]

- DeVan, M.R. Warming Up: Climate Change Related Shifts of Mycorrhizal Fungal Communities in High Latitude Ecosystems; The University of New Mexico: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Corrales, A.; Henkel, T.W.; Smith, M.E. Ectomycorrhizal associations in the tropics-biogeography, diversity patterns and ecosystem roles. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 1076–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, T.A.; Nara, K.; Hogetsu, T. Host effects on ectomycorrhizal fungal communities: Insight from eight host species in mixed conifer-broadleaf forests. New Phytol. 2007, 174, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Wu, X.H.; Li, H.W.; Ning, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; He, J.S.; Filimonenko, E.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.Y. Soil quality and r-K fungal communities in plantations after conversion from subtropical forest. Catena 2022, 219, 106584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toljander, J.F.; Eberhardt, U.; Toljander, Y.K.; Paul, L.R.; Taylor, A.F. Species composition of an ectomycorrhizal fungal community along a local nutrient gradient in a boreal forest. New Phytol. 2006, 170, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.B.; Zhang, P.P.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.B.; Zhang, T.X.; Liu, B. The ectomycorrhizal fungi and soil bacterial communities of the five typical tree species in the Junzifeng national nature reserve, southeast China. Plants 2023, 12, 3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ASVs | Species | Juvenile (%) | Adult (%) | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASV786 | Inocybe sp. | 3.069 ± 1.538 a | 0.1417 ± 0.0913 b | <0.01 |

| ASV555 | Russula sp. | 0.2329 ± 0.1441 a | 0.0042 ± 0.0030 b | <0.001 |

| ASV930 | Sebacina sp. | 0.1064 ± 0.0245 a | 0.0007 ± 0.0007 b | <0.001 |

| ASV116 | Russula vinosobrunneola | 0.6107 ± 0.3074 b | 1.6185 ± 0.8141 a | <0.001 |

| ASV364 | Sebacina sp. | 0.5149 ± 0.3411 b | 1.3724 ± 0.5523 a | <0.001 |

| ASV1009 | Russula sp. | 0.8488 ± 0.3788 b | 0.9635 ± 0.5537 a | <0.001 |

| ASV209 | Russula sp. | 0 ± 0 b | 0.8983 ± 0.5476 a | <0.001 |

| ASV489 | Suillus flavidus | 0.0068 ± 0.0049 b | 0.7634 ± 0.3583 a | <0.001 |

| ASV642 | Amphinema diadema | 0.5812 ± 0.3338 b | 0.6917 ± 0.4717 a | <0.001 |

| ASV1165 | Inocybe sp. | 0 ± 0 b | 0.4652 ± 0.2546 a | <0.001 |

| ASV1104 | Sebacina sp. | 0.2043 ± 0.1479 b | 0.4614 ± 0.3157 a | <0.001 |

| ASV129 | Tomentella sp. | 0.0012 ± 0.0012 b | 0.4513 ± 0.3101 a | <0.001 |

| ASV1127 | Tomentella sp. | 0.2043 ± 0.1865 b | 0.4052 ± 0.1823 a | <0.001 |

| ASV1088 | Pseudotomentella sp. | 0.0209 ± 0.0145 b | 0.3359 ± 0.1813 a | <0.001 |

| ASV778 | Tomentella sp. | 0 ± 0 b | 0.2061 ± 0.1652 a | <0.001 |

| ASV97 | Sebacina sp. | 0.0525 ± 0.0524 b | 0.1479 ± 0.1343 a | <0.01 |

| ASV744 | Pseudotomentella sp. | 0.0744 ± 0.0712 b | 0.1437 ± 0.1039 a | <0.001 |

| ASV183 | Rhodoscypha sp. | 0.0105 ± 0.0105 b | 0.1412 ± 0.1020 a | <0.01 |

| ASV537 | Piloderma sp. | 0.0912 ± 0.0393 b | 0.1377 ± 0.1206 a | <0.05 |

| ASV500 | Russula sp. | 0.0033 ± 0.0026 b | 0.1207 ± 0.0148 a | <0.001 |

| ASV872 | Tarzetta sp. | 0.0239 ± 0.0199 b | 0.0824 ± 0.0496 a | <0.01 |

| ASV184 | Pseudotomentella sp. | 0.0000 ± 0.0000 b | 0.0759 ± 0.0108 a | <0.001 |

| ASV606 | Russula sp. | 0.0007 ± 0.0007 b | 0.0640 ± 0.0129 a | <0.001 |

| ASV462 | Sebacina sp. | 0.0279 ± 0.0185 b | 0.0572 ± 0.0515 a | <0.05 |

| ASV1079 | Tomentella sp. | 0.0097 ± 0.0064 b | 0.0543 ± 0.0481 a | <0.01 |

| ASV | Species | Pinaceae (%) | Broadleaved (%) | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASV364 | Sebacina sp. | 1.706 ± 0.5915 a | 0.0637 ± 0.0193 b | <0.01 |

| ASV642 | Amphinema diadema | 1.186 ± 0.5288 a | 0.0070 ± 0.0020 b | <0.01 |

| ASV319 | Tylospora sp. | 1.153 ± 0.5281 a | 0.0391 ± 0.0276 b | <0.05 |

| ASV244 | Russula sp. | 1.004 ± 0.4452 a | 0.0400 ± 0.0196 b | <0.01 |

| ASV488 | Russula sp. | 0.6762 ± 0.5568 a | 0.0057 ± 0.0016 b | <0.05 |

| ASV178 | Sebacina sp. | 0.6349 ± 0.4949 a | 0.0006 ± 0.0004 b | <0.001 |

| ASV890 | Amphinema sp. | 0.5575 ± 0.2705 a | 0.0532 ± 0.0344 b | <0.05 |

| ASV1127 | Tomentella sp. | 0.5529 ± 0.2401 a | 0.0191 ± 0.0044 b | <0.05 |

| ASV221 | Sebacina sp. | 0.4730 ± 0.2948 a | 0.0018 ± 0.0017 b | <0.01 |

| ASV928 | Sebacina sp. | 0.4667 ± 0.1670 a | 0.0121 ± 0.0032 b | <0.01 |

| ASV129 | Tomentella sp. | 0.4042 ± 0.2885 a | 0.0183 ± 0.0062 b | <0.05 |

| ASV984 | Sebacina sp. | 0.3016 ± 0.1803 a | 0.0633 ± 0.0631 b | <0.01 |

| ASV386 | Russula sp. | 0.2761 ± 0.1801 a | 0.0003 ± 0.0002 b | <0.05 |

| ASV699 | Tomentella sp. | 0.2445 ± 0.1347 a | 0.0001 ± 0.0001 b | <0.05 |

| ASV42 | Tuber californicum | 0.2357 ± 0.2231 a | 0.0018 ± 0.0013 b | <0.05 |

| ASV778 | Tomentella sp. | 0.1840 ± 0.1536 a | 0.0085 ± 0.0029 b | <0.05 |

| ASV1129 | Inocybe sp. | 0.1515 ± 0.1048 a | 0.0003 ± 0.0002 b | <0.01 |

| ASV183 | Rhodoscypha sp. | 0.1401 ± 0.0951 a | 0.0011 ± 0.0007 b | <0.05 |

| ASV227 | Genea sp. | 0.1344 ± 0.0431 a | 0.0095 ± 0.0054 b | <0.05 |

| ASV969 | Lactarius sp. | 0.1146 ± 0.0672 a | 0.0023 ± 0.0012 b | <0.05 |

| ASV556 | Cenococcum sp. | 0.0543 ± 0.0181 a | 0.0000 ± 0.0000 b | <0.001 |

| ASV1098 | Sebacina sp. | 0.0454 ± 0.0198 a | 0.0003 ± 0.0003 b | <0.05 |

| ASV1170 | Tomentella sp. | 0.0164 ± 0.0131 a | 0.0004 ± 0.0003 b | <0.05 |

| ASV871 | Sebacina sp. | 0.0074 ± 0.0032 a | 0.0000 ± 0.0000 b | <0.05 |

| ASV130 | Tomentella sp. | 0.0049 ± 0.0040 b | 1.758 ± 1.135 a | <0.01 |

| ASV820 | Russula sp. | 0.0336 ± 0.0175 b | 0.9874 ± 0.3098 a | <0.001 |

| ASV1123 | Russula sp. | 0.0000 ± 0.0000 b | 0.3256 ± 0.1549 a | <0.001 |

| ASV857 | Sebacina sp. | 0.0641 ± 0.0375 b | 0.1185 ± 0.0756 a | <0.05 |

| ASV543 | Pachyphlodes nemoralis | 0.0121 ± 0.0108 b | 0.1033 ± 0.0481 a | <0.01 |

| ASV994 | Cenococcum sp. | 0.0076 ± 0.0033 b | 0.0902 ± 0.0415 a | <0.01 |

| ASV1137 | Laccaria parva | 0.0012 ± 0.0012 b | 0.0701 ± 0.0306 a | <0.001 |

| ASV1018 | Piloderma sp. | 0.0002 ± 0.0002 b | 0.0463 ± 0.0188 a | <0.01 |

| ASV1290 | Genea zamorana | 0.0000 ± 0.0000 b | 0.0018 ± 0.0009 a | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, D.-X.; Wei, Y.-L.; You, Z.-Q.; Bai, Z.; Yuan, H.-S. Host Developmental Stage and Vegetation Type Govern Root EcM Fungal Assembly in Temperate Forests. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11040307

Zhao D-X, Wei Y-L, You Z-Q, Bai Z, Yuan H-S. Host Developmental Stage and Vegetation Type Govern Root EcM Fungal Assembly in Temperate Forests. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(4):307. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11040307

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Dong-Xue, Yu-Lian Wei, Zi-Qi You, Zhen Bai, and Hai-Sheng Yuan. 2025. "Host Developmental Stage and Vegetation Type Govern Root EcM Fungal Assembly in Temperate Forests" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 4: 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11040307

APA StyleZhao, D.-X., Wei, Y.-L., You, Z.-Q., Bai, Z., & Yuan, H.-S. (2025). Host Developmental Stage and Vegetation Type Govern Root EcM Fungal Assembly in Temperate Forests. Journal of Fungi, 11(4), 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11040307