Differences in Soil Fungal Communities between Forested Reclamation and Forestry Sites in the Alberta Oil Sands Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Descriptions

2.2. Sample Collection and Processing

2.3. Sporocarp Survey on Jack Pine Transects (2014)

2.4. Soil DNA Processing and Sequencing

2.5. Soil DNA Bioinformatic Analyses

2.6. Taxonomic Identification of Soil DNA OTUs

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Assessment of Forestry and Reclamation Stands (2013–2014)—Pyrosequenced Fungal Communities

3.2. Reclamation and Forestry Jack Pine Transects (2014)

3.2.1. Abiotic Attributes

3.2.2. Pyrosequenced Fungal Communities

3.2.3. Burn Intensity Effects from Pyrosequenced Fungal Communities

3.2.4. Illumina-Sequenced Fungal Communities

3.2.5. Sporocarp Survey

4. Discussion

4.1. General Differences in Community Composition and Function

4.2. Greater Fungal Richness and Diversity in Reclamation Soils

4.3. Ectomycorrhizae Composed a Greater Proportion of Fungal Taxa Associated with Forestry Soils

4.4. More Taxa with Unknown Functional Properties Were Detected in Reclamation Soils

4.5. Pathogens Were More Abundant and Richer in Taxa in Reclamation Soils

4.6. Accounting for Potentially Confounding Environmental Factors

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Strickland, M.S.; Rousk, J. Considering fungal:bacterial dominance in soils—Methods, controls, and ecosystem implications. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1385–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, D.A.; Bardgett, R.D.; Klironomos, J.N.; Setälä, H.; van der Putten, W.H.; Wall, D.H. Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Science 2004, 304, 1629–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Ramso, J.C.; Cale, J.A.; Cahill, J.F., Jr.; Simard, S.W.; Karst, J.; Erbilgin, N. Changes in soil fungal community composition depend on functional group and forest disturbance type. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zak, J.C. Response of soil fungal communities to disturbance. In The Fungal Community: Its Organization and Role in the Ecosystem; Carroll, G.C., Wicklow, D.T., Eds.; Marcel Dekker Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 403–425. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, E.B.; Allen, M.F.; Helm, D.J.; Trappe, J.M.; Molina, R.; Rincon, E. Patterns and regulation of mycorrhizal plant and fungal diversity. Plant Soil 1995, 170, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverdrup-Thygeson, A.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Ecological continuity and assumed indicator fungi in boreal forest: The importance of the landscape matrix. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 174, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Polme, S.; Koljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-Palacios, A.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Suija, A.; et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 2014, 346, 1256688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiny, J.B.H.; Bohannan, B.J.M.; Brown, J.H.; Colwell, R.K.; Fuhrman, J.A.; Green, J.L.; Horner-Devine, M.C.; Kane, M.; Krumins, J.A.; Kuske, C.R.; et al. Microbial biogeography: Putting microorganisms on the map. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.A.; Wilson, J.; Last, F.T. Mycorrhizal fungi of Betula spp.: Factors affecting their occurrence. Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 85, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocks, B.J.; Mason, J.A.; Todd, J.B.; Bosch, E.M.; Wotton, B.M.; Amiro, B.D.; Flannigan, M.D.; Hirsch, K.G.; Logan, K.A.; Martell, D.L.; et al. Large forest fires in Canada, 1959–1997. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2002, 107, FFR 5-1–FFR 5-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volney, W.J.A.; Hirsch, K.G. Disturbing forest disturbances. For. Chron. 2005, 81, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delong, S.C.; Tanner, D. Managing the pattern of forest harvest: Lessons from wildfire. Biodivers. Conserv. 1996, 5, 1191–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durall, D.M.; Jones, M.D.; Lewis, K.J. Effects of forest management on fungal communities. In The Fungal Community, Its Organization and Role in Ecosystems; Dighton, J., White, J.F., Oudermans, P., Eds.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2005; pp. 833–856. [Google Scholar]

- Garbaye, J.; Le Tacon, F. Influence of mineral fertilization and thinning intensity on the fruit body production of epigeous fungi in an artificial spruce stand (Picea excelsa Link) in north-eastern France. Acta Oecol. Oecol. Plant. 1982, 3, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Last, F.T.; Mason, P.A.; Smith, R.; Pelham, J.; Shetty, K.A.B.; Hussain, A.M.M. Factors affecting the production of fruitbodies of Amanita muscaria in plantations of Pinus patula. Proc. Plant Sci. 1981, 90, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wästerlund, I.; Ingelög, T. Fruit body production of larger fungi in some young Swedish forests with special reference to logging waste. For. Ecol. Manag. 1981, 3, 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outerbridge, R.A.; Trofymow, J.A. Forest management and maintenance of ectomycorrhizae: A case study of green tree retention in south-coastal British Columbia. BC J. Ecosyst. Manag. 2009, 10, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofymow, J.A.; van den Driessche, R. Mycorrhizas. In Mineral Nutrition of Conifer Seedlings; Van den Driessche, R., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1991; pp. 183–228. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, S.; Maynard, D.; Danielson, R.M. Response of ecto- and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to clear-cutting and the application of chipped aspen wood in a mixedwood site in Alberta, Canada. Appl. Soil Ecol. 1998, 7, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, J.D.; Leopold, D.J.; Smallidge, P.J. Pathogens, Patterns, and Processes in Forest Ecosystems. BioScience 1995, 45, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.H.; Merler, H.; Norris, D. Detection, Recognition and Management of Armillaria and Phellinus Root Diseases in the Southern Interior of British Columbia; Canada-British Columbia Partnership Agreement on Forest Resource Development: FRDA II: Victoria, BC, Canada, 1992.

- Laflamme, G. Root diseases in forest ecosystems. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 32, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, R.M.; Visser, S.; Parkinson, D. Microbial activity and mycorrhizal potential of four overburden types used in the reclamation of extracted oil sands. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1983, 63, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E.; Henkel, T.W.; Rollins, J.A. How many fungi make sclerotia? Fungal Ecol. 2015, 13, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, G.C.; Wicklow, D.T. The Fungal Community: Its Organization and Role in the Ecosystem, 2nd ed.; Marcel Dekker Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bois, G.; Piche, Y.; Fung, M.Y.P.; Khasa, D.P. Mycorrhizal inoculum potentials of pure reclamation materials and revegetated tailing sands from the Canadian oil sand industry. Mycorrhiza 2005, 15, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermosilla, T.; Wulder, M.A.; White, J.C.; Coops, N.C.; Hobart, G.W.; Campbell, L.B. Mass data processing of time series Landsat imagery: Pixels to data products for forest monitoring. Int. J. Digital Earth 2016, 9, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckingham, J.D.; Archibald, J.H. Field Guide to the Ecosites of Northern Alberta; Special Report 5; Canadian Forest Service: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1996.

- Syncrude. Syncrude Gateway Hill (S4 Area) Reclamation Certification Application: Section 6.5 Soils; Syncrude Canada Ltd.: Fort McMurray, AB, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kalra, Y.P.; Maynard, D.G. Methods Manual for Forest Soil and Plant Analysis; Forestry Canada, Northwest Region, Northern Forestry Centre: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1991.

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes—Application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D.N. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System (http://www.barcodinglife.org). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõljalg, U.; Nilsson, R.H.; Abarenkov, K.; Tedersoo, L.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Bahram, M.; Bates, S.T.; Bruns, T.D.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Callaghan, T.M.; et al. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 5271–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.D.; Lee, S.B.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M., Gelfand, D., Shinsky, J., White, T., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Bérubé, J.A.; Gagné, P.N.; Ponchart, J.P.; Tremblay, E.D.; Bilodeau, G.J. Detection of Diplodia corticola spores in Ontario and Québec based on high throughput sequencing (HTS) methods. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 40, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huse, S.M.; Welch, D.M.; Morrison, H.G.; Sogin, M.L. Ironing out the wrinkles in the rare biosphere through improved OTU clustering. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunin, V.; Engelbrektson, A.; Ochman, H.; Hugenholtz, P. Wrinkles in the rare biosphere: Pyrosequencing errors can lead to artificial inflation of diversity estimates. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, J.; Knight, R. The ‘rare biosphere’: A reality check. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J.; et al. Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2460–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Kristiansson, E.; Ryberg, M.; Hallenberg, N.; Larsson, K.-H. Intraspecific ITS variability in the kingdom Fungi as expressed in the international sequence databases and its implications for molecular species identification. Evol. Bioinform. Online 2008, 4, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Huhndorf, S.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J.L.; Levesque, C.A.; Chen, W. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6241–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masella, A.P.; Bartram, A.K.; Truszkowski, J.M.; Brown, D.G.; Neufeld, J.D. PANDAseq: Paired-end assembler for Illumina sequences. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, P.N.; Bérubé, J.A. Illumicut, a C++ Program Specially Designed to Efficiently Detect and Remove forward and Reverse Sequencing Primers in Paired-End Reconstructed Sequences. 2017. Available online: https://github.com/Patg13/Illumicut (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Gagné, P.N.; Bérubé, J.A. HomopRemover, a Program Designed to Efficiently Remove Sequences Containing very Long Homopolymers. 2017. Available online: https://github.com/Patg13/HomopRemover (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Rognes, T.; Flouri, T.; Nichols, B.; Quince, C.; Mahé, F. VSEARCH: A versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dollive, S.; Peterfreund, G.L.; Sherrill-Mix, S.; Bittinger, K.; Sinha, R.; Hoffmann, C.; Nabel, C.S.; Hill, D.A.; Artis, D.; Bachman, M.A.; et al. A tool kit for quantifying eukaryotic rRNA gene sequences from human microbiome samples. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Giner, C.R.; Forn, I.; Romac, S.; Logares, R.; de Vargas, C.; Massana, R. Environmental sequencing provides reasonable estimates of the relative abundance of specific picoeukaryotes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 4757–4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2017. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Legendre, P.; Birks, H.J.B. From classical to canonical ordination. In Tracking Environmental Change Using Lake Sediments; Volume 5: Data Handling and Numerical Techniques; Birks, H.J.B., Lotter, A.F., Juggins, S., Smol, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 201–248. [Google Scholar]

- Borcard, D.; Legendre, P.; Avois-Jacquet, C.; Tuomisto, H. Dissecting the spatial structure of ecological data at multiple scales. Ecology 2004, 85, 1826–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinez-Dominguez, E.; Freire, J. Information-theoretic approach for selection of spatial and temporal models of community organization. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2003, 253, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borcard, D.; Legendre, P.; Drapeau, P. Partialling out the spatial component of ecological variation. Ecology 1992, 73, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.K.; Cunningham, A.A.; Patel, N.G.; Morales, F.J.; Epstein, P.R.; Daszak, P. Emerging infectious diseases of plants: Pathogen pollution, climate change and agrotechnology drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.W.; Hoeksema, J.D.; Gehring, C.A.; Johnson, N.C.; Klironomos, J.N.; Abbott, L.K.; Pringle, A. The promise and the potential consequences of the global transport of mycorrhizal fungal inoculum. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, T.D.; Laidly, P.R. Pinus banksiana. In Silvics of North America; Volume 1: Conifers; Agriculture Handbook 654; Burns, R.M., Honkala, B.H., Eds.; USDA Forest Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; pp. 280–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hättenschwiler, S.; Tiunov, A.V.; Scheu, S. Biodiversity and litter decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. System 2005, 36, 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, K.L.; Fierer, N.; Bateman, C.; Treseder, K.K.; Turner, B.L. Fungal community composition in neotropical rain forests: The influence of tree diversity and precipitation. Microb. Ecol. 2012, 63, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofymow, J.A.; Shay, P.-E.; Myrholm, C.L.; Tomm, B.; Bérubé, J.A.; Ramsfield, T.D. Fungi associated with tree species at an Alberta oil sands reclamation area as determined by sporocarp assessments and high-throughput DNA sequencing. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 147, 103359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubartova, A.; Ranger, J.; Berthelin, J.; Beguiristain, T. Diversity and decomposing ability of saprophytic fungi from temperate forest litter. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 58, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsfield, T.; Shay, P.-E.; Trofymow, T.; Myrholm, C.; Tomm, B.; Gagné, P.; Bérubé, J. Distance from the forest edge influences soil fungal communities colonizing a reclaimed soil borrow site in boreal mixedwood forest. Forests 2020, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeksema, J.D.; Piculell, B.J.; Thompson, J.N. Within-population genetic variability in mycorrhizal interactions. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2009, 2, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, T.; Dell, B.; Malajczuk, N. Variation in mycorrhizal development and growth stimulation by 20 Pisolithus isolates inoculated on to Eucalyptus grandis W. Hill ex Maiden. New Phytol. 1994, 127, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweitzer, J.A.; Bailey, J.K.; Fischer, D.G.; LeRoy, C.J.; Lonsdorf, E.V.; Whitham, T.G.; Hart, S.C. Plant-soil-microorganism interactions: Heritable relationship between plant genotype and associated soil microorganisms. Ecology 2008, 89, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwuchekwa, N.E.; Zwiazek, J.J.; Quoreshi, A.; Khasa, D.P. Growth of mycorrhizal jack pine (Pinus banksiana) and white spruce (Picea glauca) seedlings planted in oil sands reclaimed areas. Mycorrhiza 2014, 24, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finzi, A.C.; Van Breemen, N.; Canham, C.D. Canopy tree soil interactions within temperate forests: Species effects on soil carbon and nitrogen. Ecol. Appl. 1998, 8, 440–446. [Google Scholar]

- Ste-Marie, C.; Houle, D. Forest floor gross and net nitrogen mineralization in three forest types in Quebec, Canada. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 2135–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, J.; Miller, M.; Kjøller, A. Fungal–bacterial interaction on beech leaves: Influence on decomposition and dissolved organic carbon quality. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1999, 31, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, M.D.; Quideau, S.A. Microbial community structure and nutrient availability in oil sands reclaimed boreal soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2010, 44, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanney, J.B.; Douglas, B.; Seifert, K.A. Sexual and asexual states of some endophytic Phialocephala species of Picea. Mycologia 2016, 108, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumpponen, A.; Trappe, J.M. Dark septate endophytes: A review of facultative biotrophic root-colonizing fungi. New Phytol. 1998, 140, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, M. The Fungi: 1, 2, 3 … 5.1 million species? Am. J. Bot. 2011, 98, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, P.J.; Dobson, A.P.; Lafferty, K.D. Is a healthy ecosystem one that is rich in parasites? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006, 21, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, K.E.; Bever, J.D. Maintenance of diversity within plant communities: Soil pathogens as agents of negative feedback. Ecology 1998, 79, 1595–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, A.; Clay, K. Soil pathogens and spatial patterns of seedling mortality in a temperate tree. Nature 2000, 404, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, P.M.; Cannon, P.F.; Minter, D.W.; Stalpers, J.A. (Eds.) Dictionary of the Fungi, 10th ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Agriculture, Victoria, Forest Pathology Herbarium (DAVFP). 2018. Available online: http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/forests/research-centres/pfc/13493 (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- Ragazzi, A.; Moricca, S.; Capretti, P.; Dellavalle, I.; Turco, E. Differences in composition of endophytic mycobiota in twigs and leaves of healthy and declining Quercus species in Italy. For. Pathol. 2003, 33, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmschlager, E.; Kowalski, T. The mycobiota in nonmycorrhizal roots of healthy and declining oaks. Can. J. Bot. 2004, 82, 1446–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certini, G. Effects of fire on properties of forest soils: A review. Oecologia 2005, 143, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouginot, C.; Kawamura, R.; Matulich, K.L.; Berlemont, R.; Allison, S.D.; Amend, A.S.; Martiny, A.C. Elemental stoichiometry of Fungi and Bacteria strains from grassland leaf litter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 76, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.L.; Holmes, A.J.; Westoby, M.; Oliver, I.; Briscoe, D.; Dangerfield, M.; Gillings, M.; Beattie, A.J. Spatial scaling of microbial eukaryote diversity. Nature 2004, 432, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramette, A.; Tiedje, J.M. Multiscale responses of microbial life to spatial distance and environmental heterogeneity in a patchy ecosystem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 2761–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, P.E.; Winder, R.S.; Trofymow, J.A. Nutrient-cycling microbes in coastal Douglas-fir forests: Regional-scale correlation between communities, in situ climate, and other factors. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Area | Site | Tree Species | Latitude (N) | Longitude (W) | Soil Placed | Regeneration Year | Disturbance Type | Samples 2013–2014 | Samples 2014 | Forest Floor Depth (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | TR1B1 | Jack pine | 57.54356 | 111.36559 | NA | 2012 | Severe burn | 1 | 0.2 | |

| FC | TR2H | Jack pine | 57.51772 | 111.40374 | NA | 1996 | Harvest | 1 | 1.5 | |

| FC | TR3L | Jack pine | 57.48267 | 111.51478 | NA | 1954 | Light partial burn | 1 | 1.5 | |

| FC | TR4U | Jack pine | 57.42612 | 111.59225 | NA | 1950 | Undisturbed | 1 | 20.0 | |

| FC | TR1B2 | Jack pine | 57.54317 | 111.36305 | NA | 2012 | Severe burn | 1 | 3 | 0.2 |

| FC | TR1P | Jack pine | 57.54206 | 111.36395 | NA | 1954 | Partial burn | 1 | 3 | 0.8 |

| GH | M6 | White spruce | 56.99657 | 111.56528 | 1990 | 1990 | Reclamation | 1 | 2.4 | |

| GH | M14 | White spruce | 56.99309 | 111.57028 | 1984 | 1985 | Reclamation | 1 | 3.5 | |

| GH | M8 | Siberian larch | 56.99588 | 111.56616 | 1990 | 1990 | Reclamation | 1 | 5.3 | |

| GH | M2 | Jack pine | 56.99269 | 111.56274 | 1982 | 1983 | Reclamation | 1 | 3 | 1.8 |

| GH | M7 | Jack pine | 56.99566 | 111.56574 | 1990 | 1990 | Reclamation | 1 | 3 | 3.4 |

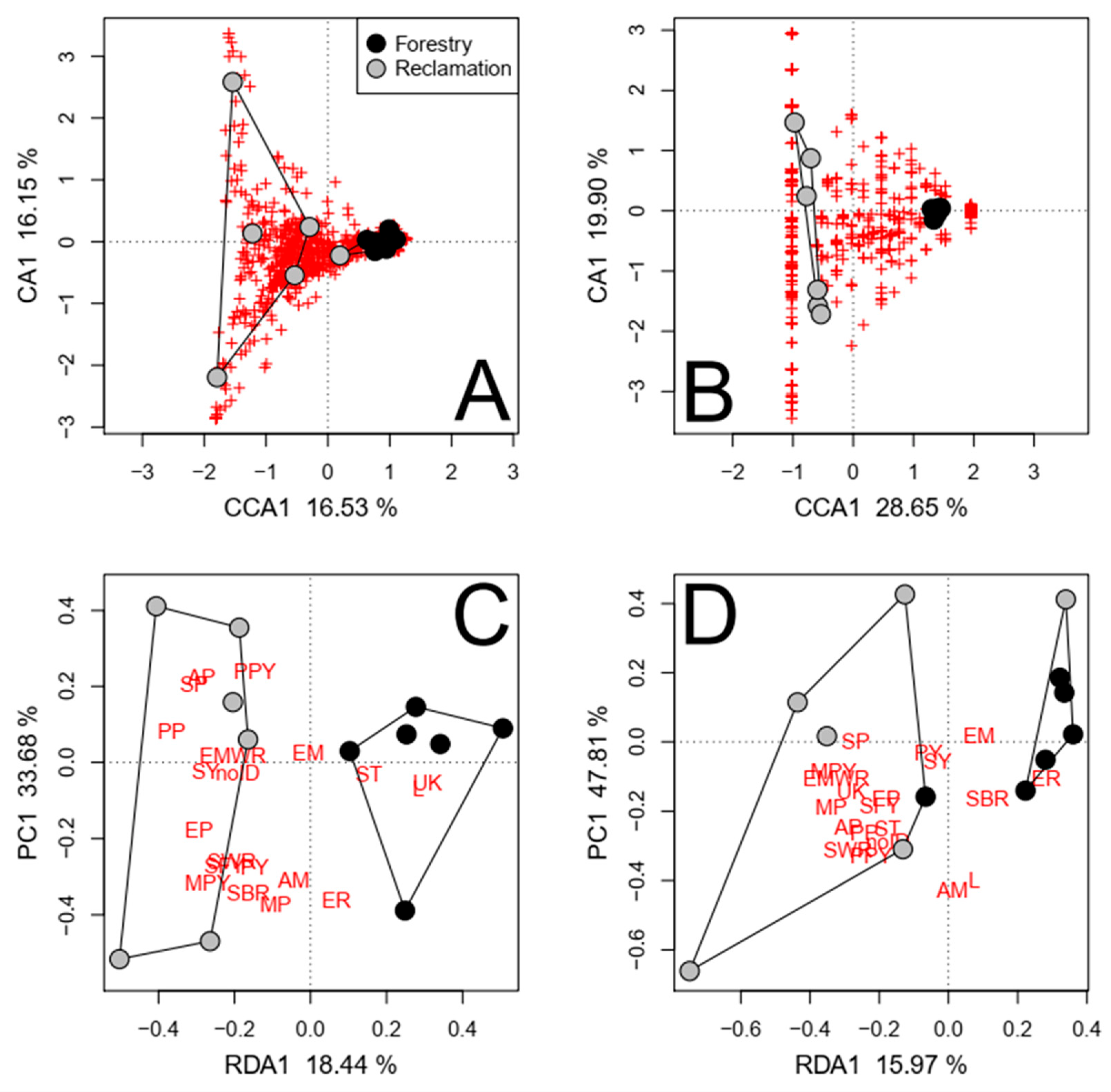

| Response | Soil Fraction | Reclamation Status | Shared | Other Factors | Residual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Fungal taxa | |||||

| Relative abundance | |||||

| Coarse soils † | 16.53 *** | 1.78 | 10.91 | 70.78 | |

| Coarse soils ‡ | 18.14 ** | 0 | 13.29 | 68.57 | |

| Fine soils ‡ | 18.58 *** | 0.07 | 14.10 | 67.25 | |

| Forest floors ‡ | 15.86 ** | 1.02 | 14.62 | 68.50 | |

| Roots ‡ | 13.22 ** | 0 | 0 | 86.78 | |

| Both roots and coarse soils ‡,§ | 8.59 *** | 2.23 | 19.61 | 69.57 | |

| All soil fractions ‡,§ | 5.56 *** | 2.20 | 14.40 | 77.84 | |

| Presence/absence | |||||

| Coarse soils † | 28.65 ** | 0 | 0 | 71.35 | |

| Coarse soils ‡ | 21.94 ** | 0 | 0 | 78.06 | |

| Fine soils ‡ | 21.21 ** | 5.16 | 14.32 | 59.31 | |

| Forest floors ‡ | 16.61 * | 2.96 | 27.83 | 52.60 | |

| Roots ‡ | 15.20 *** | 1.47 | 10.35 | 72.98 | |

| Both roots and coarse soils ‡,§ | 11.14 *** | 4.25 | 19.72 | 64.89 | |

| All soil fractions ‡,§ | 7.33 *** | 6.21 | 21.51 | 64.95 | |

| (B) Functional groups | |||||

| Relative abundance | |||||

| Coarse soils † | 18.44 ** | 0 | 34.65 | 46.91 | |

| Coarse soils ‡ | 30.05 *** | 0 | 18.10 | 51.85 | |

| Fine soils ‡ | 17.45 * | 6.97 | 29.84 | 45.74 | |

| Forest floors ‡ | 15.36 | 0 | 22.82 | 61.82 | |

| Roots ‡ | 11.53 | 0.54 | 13.73 | 74.20 | |

| Both roots and coarse soils ‡,§ | 14.57 *** | 0 | 20.18 | 65.25 | |

| All soil fractions ‡,§ | 9.33 *** | 0.87 | 10.59 | 79.21 | |

| Number of taxa | |||||

| Coarse soils † | 15.97 * | 21.16 | 16.46 | 46.41 | |

| Coarse soils ‡ | 46.46 ** | 0 | 0 | 53.54 | |

| Fine soils ‡ | 34.19 ** | 1.25 | 16.28 | 48.28 | |

| Forest floors ‡ | 11.63 | 16.88 | 16.01 | 55.48 | |

| Roots ‡ | 30.91 *** | 0 | 0 | 69.09 | |

| Both roots and coarse soils ‡,§ | 33.18 *** | 0 | 13.70 | 53.12 | |

| All soil fractions ‡,§ | 25.82 *** | 0.43 | 10.19 | 63.56 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trofymow, J.A.; Shay, P.-E.; Tomm, B.; Bérubé, J.A.; Ramsfield, T. Differences in Soil Fungal Communities between Forested Reclamation and Forestry Sites in the Alberta Oil Sands Region. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9111110

Trofymow JA, Shay P-E, Tomm B, Bérubé JA, Ramsfield T. Differences in Soil Fungal Communities between Forested Reclamation and Forestry Sites in the Alberta Oil Sands Region. Journal of Fungi. 2023; 9(11):1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9111110

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrofymow, John. A., Philip-Edouard Shay, Bradley Tomm, Jean A. Bérubé, and Tod Ramsfield. 2023. "Differences in Soil Fungal Communities between Forested Reclamation and Forestry Sites in the Alberta Oil Sands Region" Journal of Fungi 9, no. 11: 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9111110

APA StyleTrofymow, J. A., Shay, P.-E., Tomm, B., Bérubé, J. A., & Ramsfield, T. (2023). Differences in Soil Fungal Communities between Forested Reclamation and Forestry Sites in the Alberta Oil Sands Region. Journal of Fungi, 9(11), 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9111110