Response to Sulfur Dioxide Addition by Two Commercial Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Inoculation, Fermentation, and Sampling

2.3. Residual Sugar Concentration

2.4. Yeast Abundance

2.5. Sulfur Dioxide Determination and Sulfite Resistance Assay

2.6. Hydrogen Sulfide Determination

2.7. Acetaldehyde Determination

2.8. Secondary Metabolite Analysis

2.8.1. Chemical Standards

2.8.2. Quality Assurance and Standard Curves

2.8.3. Sample Preparation

2.8.4. Instrumentation and Parameters

2.9. Strain-Typing

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

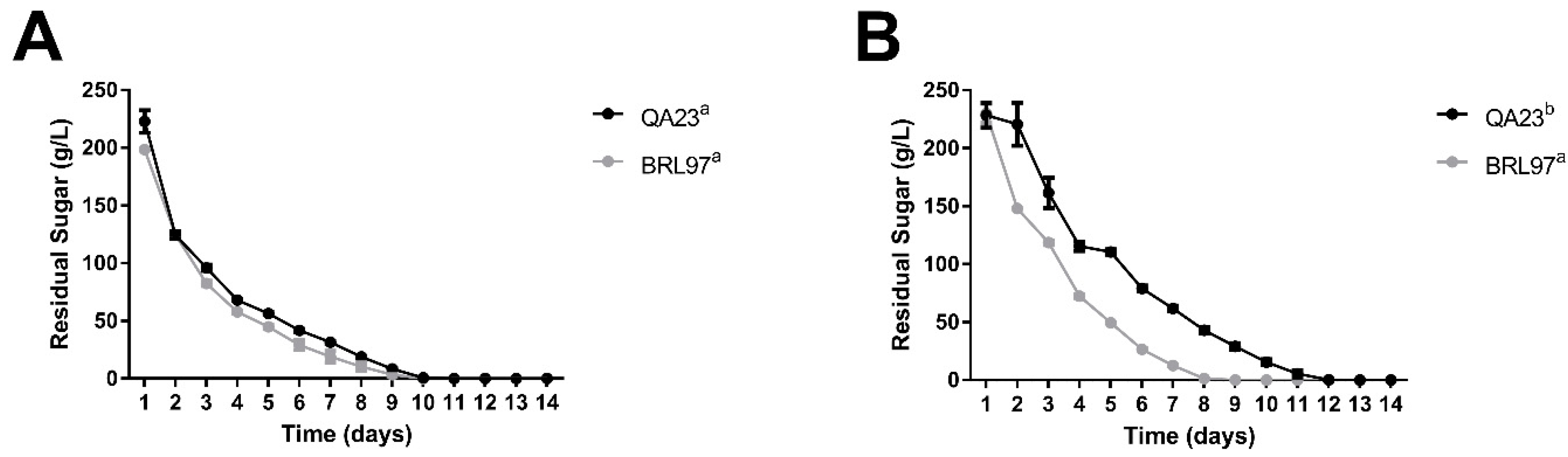

3.1. Fermentation Kinetics and Yeast Abundance

3.2. Sulfur Dioxide Concentration during Fermentation

3.3. Hydrogen Sulfide Production during Fermentation

3.4. Post-Fermentation Acetaldehyde Production

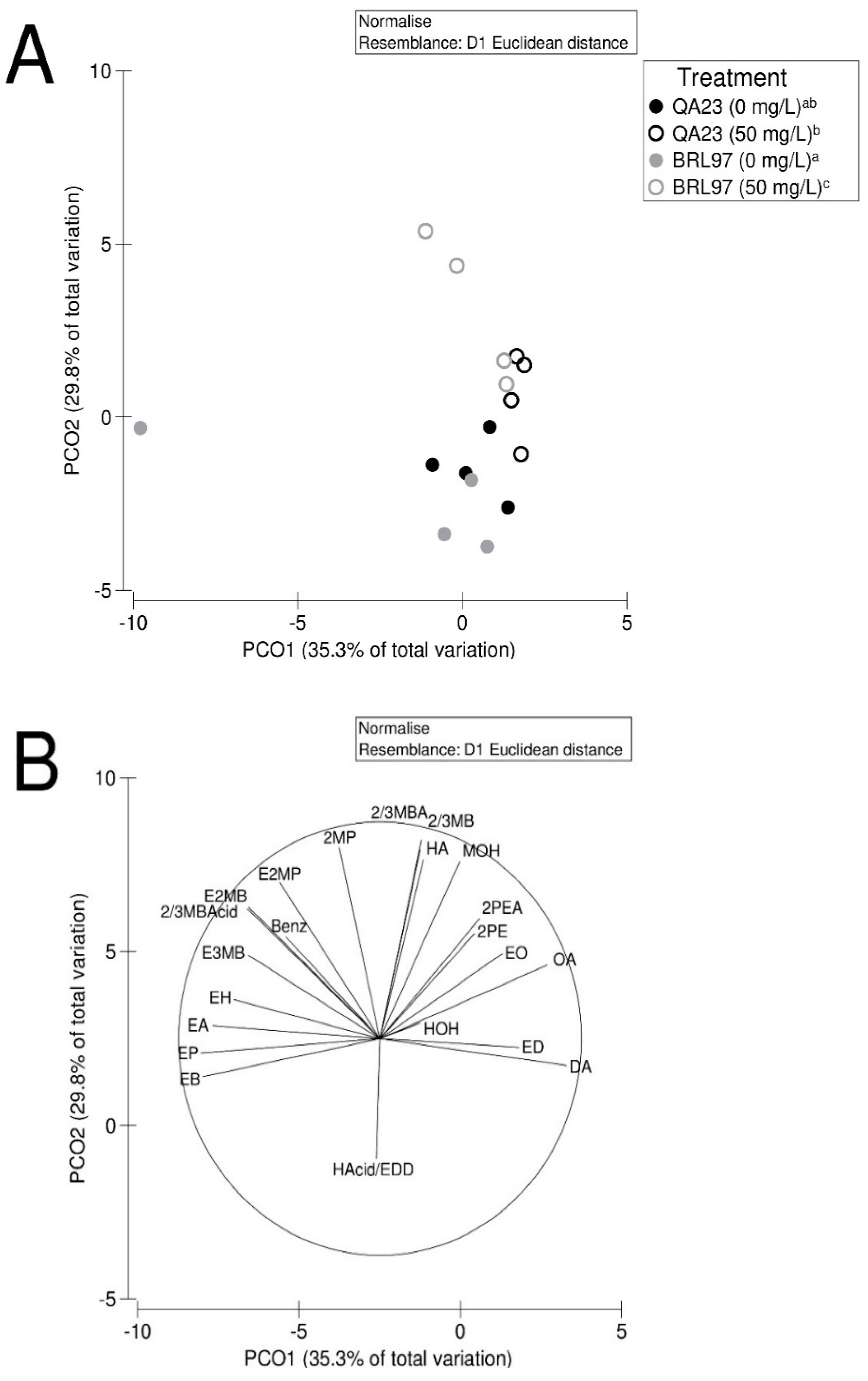

3.5. Yeast-Derived Secondary Metabolite Composition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Metabolite | Rt (min) | Quantitation Ion Mass | Confirmation Ion Mass | Scan Window (min) | Dwell Time (msec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethyl acetate | 3.78 | 43.00 | 29.0 | 0.12 | 40 |

| Ethyl propanoate | 4.45 | 43.00 | 57.0 | 0.66 | 20 |

| Ethyl 2-methylpropanoate | 4.54 | 43.00 | 57.0 | 0.85 | 20 |

| Ethyl butanoate | 5.51 | 31.00 | 88.0 | 0.72 | 25 |

| Ethyl 2-methylbutanoate | 5.84 | 102.00 | 87.0 | 0.68 | 20 |

| Ethyl 3-methylbutanoate | 6.04 | 88.00 | 130.0 | 0.48 | 30 |

| 2-methyl propanol | 6.55 | 41.00 | 43.0 | 0.88 | 30 |

| 2-methylbutyl acetate | 7.00 | 87.00 | 72.0 | 0.60 | 30 |

| 3-methylbutyl acetate | 7.10 | 87.00 | 72.0 | 0.80 | 30 |

| 2-methyl butanol | 9.10 | 42.00 | 56.0 | 1.80 | 100 |

| 3-methyl butanol | 9.20 | 42.00 | 56.0 | 2.00 | 100 |

| Ethyl hexanoate | 9.65 | 88.00 | 99.0 | 1.10 | 100 |

| Hexyl acetate | 10.63 | 69.00 | 73.0 | 1.44 | 100 |

| Hexanol | 12.56 | 45.00 | 56.0 | 2.72 | 30 |

| Ethyl octanoate | 14.76 | 88.00 | 101.0 | 2.52 | 100 |

| 1-octanol (internal standard) | 17.65 | 56.00 | 41.0 | 4.30 | 100 |

| Ethyl decanoate | 19.68 | 101.00 | 157.0 | 2.36 | 100 |

| 2-methylbutanoic acid | 20.28 | 61.00 | 73.0 | 1.26 | 100 |

| 3-methylbutanoic acid | 20.28 | 61.00 | 73.0 | 1.26 | 100 |

| Methionol | 21.38 | 106.00 | 61.0 | 1.56 | 100 |

| 2-phenylethyl acetate | 23.60 | 65.00 | 104.0 | 3.20 | 100 |

| Hexanoic acid | 24.12 | 101.00 | 60.0 | 1.14 | 100 |

| Ethyl dodecanoate | 24.20 | 101.00 | 60.0 | 1.30 | 100 |

| Benzyl alcohol | 24.82 | 79.00 | 51.0 | 0.74 | 80 |

| 2-phenylethanol | 25.56 | 91.00 | 92.0 | 1.42 | 100 |

| Octanoic acid | 28.44 | 60.00 | 73.0 | 2.88 | 100 |

| Decanoic acid | 32.33 | 73.00 | 139.0 | 4.66 | 100 |

| C11 | C3 | C4 | C8 | YOR267c | YLR177w | YML091c | YPL009c | |||||||||

| A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | |

| QA23 | 191 | 216 | 115 | 121 | 312 | 312 | 140 | 146 | 306 | 312 | 125 | 125 | 268 | 317 | 422 | 434 |

| BRL97 | 194 | 202 | 121 | 121 | 244 | 250 | 143 | 143 | 280 | 280 | 125 | 125 | 302 | 302 | 446 | 446 |

| C11 | C3 | C4 | C8 | YOR267c | YLR177w | YML091c | YPL009c | |||||||||

| A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | A1 | A2 | |

| QA23 | 191 | 216 | 115 | 121 | 312 | 312 | 140 | 146 | 306 | 312 | 125 | 125 | 268 | 317 | 422 | 434 |

| BRL97 | 194 | 202 | 121 | 121 | 244 | 250 | 143 | 143 | 280 | 280 | 125 | 125 | 302 | 302 | 446 | 446 |

References

- Divol, B.; du Toit, M.; Duckitt, E. Surviving in the presence of sulphur dioxide: Strategies developed by wine yeasts. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnolucci, M.; Rea, F.; Sbrana, C.; Cristani, C.; Fracassetti, D.; Tirelli, A.; Nuti, M. Sulphur dioxide affects culturability and volatile phenol production by Brettanomyces/Dekkera bruxellensis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 143, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnolucci, M.; Cristani, C.; Maggini, S.; Rea, F.; Cossu, A.; Tirelli, A.; Nuti, M. Impact of sulphur dioxide on the viability, culturability, and volatile phenol production of Dekkera bruxellensis in wine. Ann. Microbiol. 2013, 64, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divol, B.; Lonvaud-Funel, A. Evidence for viable but nonculturable yeasts in botrytis-affected wine. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piškur, J.; Rozpedowska, E.; Polakova, S.; Merico, A.; Compagno, C. How did Saccharomyces evolve to become a good brewer? Trends Genet. 2006, 22, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salma, M.; Rousseaux, S.; Sequeira-Le Grand, A.; Divol, B.; Alexandre, H. Characterization of the Viable but Nonculturable (VBNC) State in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.D.; Ponting, J.D.; Sanshuck, D.W.; Jackson, R.; Mihara, K. Factors affecting death of yeast by sulfur dioxide. J. Food Prot. 1981, 44, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, P.A.; Worobo, R.; Sacks, G.L. Conventional measurements of sulfur dioxide (SO2) in red wine overestimate SO2 antimicrobial activity. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Bakalinsky, A.T. SSU1 mediates sulphite efflux in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2000, 16, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, D.; Leid, M.; Bakalinsky, A.T. Fzf1p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a positive regulator of SSU1 transcription and its first zinc finger region is required for DNA binding. Yeast 1999, 15, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, T.; Corich, V.; Giacomini, A.; Blondin, B. A sulphite-inducible form of the sulphite efflux gene SSU1 in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine yeast. Microbiology 2010, 156, 1686–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aa, E.; Townsend, J.P.; Adams, R.I.; Nielsen, K.M.; Taylor, J.W. Population structure and gene evolution in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. Rev. 2006, 6, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto-Yamamoto, N.; Kitano, K.; Shiki, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Iwata, T.; Yamane, Y.; Hara, S. SSU1-R, a sulfite resistance gene of wine yeast, is an allele of SSU1 with a different upstream sequence. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1998, 86, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, T.E.; Bramley, B.; Solomon, M. Hydrogen sulfide: Aroma detection threshold study in white and red wines. AWRI Tech. Rev. 2009, 183, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Swiegers, J.H.; Bartowsky, E.J.; Henschke, P.A.; Pretorius, I.S. Yeast and bacterial modulation of wine aroma and flavour. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2005, 11, 139–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalone, E.; Colella, C.M.; Daly, S.; Gallori, E.; Moriani, L.; Polsinelli, M. Mechanism of resistance to sulphite in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 1992, 22, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratford, M.; Morgan, P.; Rose, A.H. Sulphur dioxide resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomycodes ludwigii. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1987, 133, 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, A.; Jiménez-Martí, E.; Orozco, H.; Matallana, E.; Del Olmo, M. Sulfur and adenine metabolisms are linked, and both modulate sulfite resistance in wine yeast. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 5839–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Hwang, Y.-S. Genome-wide transcriptional responses to sulfite in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadai, C.; Treu, L.; Campanaro, S.; Giacomini, A.; Corich, V. Different mechanisms of resistance modulate sulfite tolerance in wine yeasts. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, A. What mRNA abundances can tell us about metabolism. Metabolites 2012, 2, 614–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa Abreu, R.; Penalva, L.O.; Marcotte, E.M.; Vogel, C. Global signatures of protein and mRNA expression levels. Mol. Biosyst. 2009, 5, 1512–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, C.; Marcotte, E.M. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrimpf, S.P.; Weiss, M.; Reiter, L.; Ahrens, C.H.; Jovanovic, M.; Malmström, J.; Brunner, E.; Mohanty, S.; Lercher, M.J.; Hunziker, P.E.; et al. Comparative functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster proteomes. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7, e1000048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, T.; Lü, H.; Yu, Z.; Li, X. Effect of added sulphur dioxide levels on the fermentation characteristics of strawberry wine. J. Inst. Brew. 2016, 122, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroski, M.; Crupi, P.; Tamborra, P.; Antonacci, D.; Toci, A.T. Influence of winemaking techniques with low sulphur dioxide on wine varieties Chardonnay, Pinot and Montepulciano. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 56, 326–334. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M.C.; Nunes, C.; Rocha, M.A.M.; Rodrigues, A.; Rocha, S.M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Coimbra, M.A. High pressure treatments accelerate changes in volatile composition of sulphur dioxide-free wine during bottle storage. Food Chem. 2015, 188, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borneman, A.R.; Forgan, A.H.; Kolouchova, R.; Fraser, J.A.; Schmidt, S.A. Whole genome comparison reveals high levels of inbreeding and strain redundancy across the spectrum of commercial wine strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2016, 6, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, S.C.; Scholl, C.M.; Benson, N.L.; Stone, M.L.; Durall, D.M. Sulfur dioxide addition at crush alters Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain composition in spontaneous fermentations at two Canadian wineries. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 244, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, K.S.; Cozzolino, D.; Bartowsky, E.J.; Fleet, G.H.; Henschke, P.A. Metabolic profiling as a tool for revealing Saccharomyces interactions during wine fermentation. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006, 6, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, J.J.; Watson, T.L.; Walker, M.E.; Gardner, J.M.; Lang, T.A.; Borneman, A.; Forgan, A.; Tran, T.; Jiranek, V. Use of a wine yeast deletion collection reveals genes that influence fermentation performance under low-nitrogen conditions. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018, 18, foy009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentine, G.D.S.; Walker, M.E.; Gardner, J.M.; Schmid, F.; Jiranek, V. Brief temperature extremes during wine fermentation: Effect on yeast viability and fermentation progress. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2019, 25, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondini, F.; Lang, T.; Chen, L.; Herderich, M.; Jiranek, V. Linking gene expression and oenological traits: Comparison between Torulaspora delbrueckii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 294, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, D.; Wilkinson, K.; Taylor, D.; Jiranek, V. Novel wine yeast for improved utilisation of proline during fermentation. Fermentation 2018, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoecklein, B.W.; Fugelsang, K.C.; Gump, B.H.; Nury, F.S. Wine Analysis and Production; Chapman & Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, S.C.; Tantikachornkiat, M.; Scholl, C.M.; Benson, N.L.; Cliff, M.A.; Durall, D.M. The effect of sulfur dioxide addition at crush on the fungal and bacterial communities and the sensory attributes of Pinot gris wines. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 290, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lopez, N.I.; Bakalinsky, A.T. Use of sulfite resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a dominant selectable marker. Curr. Genet. 1999, 36, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggerty, J.; Bowyer, P.K.; Jiranek, V.; Taylor, D.K. Comparative study on the sensitivity of solid-phase microextraction fibre coatings for the analysis of fermentation bouquet compounds. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2014, 20, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, I.L.; Newton, J.L. Determining wine aroma from compositional data. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2005, 11, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, H. Quantitation and sensory studies of character impact odorants of different white wine varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 3027–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, R.A.; Mauricio, J.C.; Moreno, J. Aromatic series in sherry wines with gluconic acid subjected to different biological aging conditions by Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. capensis. Food Chem. 2006, 94, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, R.A.; Moreno, J.; Medina, M.; Mauricio, J.C. Changes in volatile compounds and aromatic series in sherry wine with high gluconic acid levels subjected to aging by submerged flor yeast cultures. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004, 26, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salo, P. Determining the odor thresholds for some compounds in alcoholic beverages. J. Food Sci. 1970, 35, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, T.E.; Smyth, H.E.; Capone, D.L.; Neuwöhner, C.; Pardon, K.H.; Skouroumounis, G.K.; Herderich, M.J.; Sefton, M.A.; Pollnitz, A.P. Stable isotope dilution analysis of wine fermentation products by HS-SPME-GC-MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2005, 381, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggerty, J.J.; Taylor, D.K.; Jiranek, V. Monitoring volatile aroma compounds during fermentation in a chemically defined grape juice medium deficient in Leucine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2016, 67, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, Q.; Luo, S.; Zhang, J.; Huang, M.; Chen, F.; Zheng, F.; Ab, X.S.; Li, H. Characterization of key aroma compounds in Meilanchun sesame flavor style baijiu by application of aroma extract dilution analysis, quantitative measurements, aroma recombination, and omission/addition experiments. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 23757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; López, R.; Cacho, J.F. Quantitative determination of the odorants of young red wines from different grape varieties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legras, J.L.; Ruh, O.; Merdinoglu, D.; Karst, F. Selection of hypervariable microsatellite loci for the characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005, 102, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, K.D.; Goddard, M.R.; Gardner, R.C. A database of microsatellite genotypes for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 96, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholl, C.M.; Morgan, S.C.; Stone, M.L.; Tantikachornkiat, M.; Neuner, M.; Durall, D.M. Composition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains in spontaneous fermentations of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2016, 22, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.; Gorley, R. PRIMER v6: User Manual/Tutorial 2006; Plymouth Marine Laboratory: Plymouth, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Swadener, M.; Sakamoto, K.; Mills, D.A.; Bisson, L.F. Sulfur dioxide treatment alters wine microbial diversity and fermentation progression in a dose-dependent fashion. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2014, 66, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henick-Kling, T.; Edinger, W.; Daniel, P.; Monk, P. Selective effects of sulfur dioxide and yeast starter culture addition on indigenous yeast populations and sensory characteristics of wine. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 84, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andorrà, I.; Landi, S.; Mas, A.; Guillamón, J.M.; Esteve-Zarzoso, B. Effect of oenological practices on microbial populations using culture-independent techniques. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantí, M.; Reguant, C.; Poblet, M.; Zamora, F.; Mas, A.; Guillamon, J.M. Molecular analysis of yeast population dynamics: Effect of sulphur dioxide and inoculum on must fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1998, 41, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocolin, L.; Mills, D.A. Wine yeast inhibition by sulfur dioxide: A comparison of culture-dependent and independent methods. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2003, 54, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Pateraki, C.; Paramithiotis, S.; Doulgeraki, A.I.; Kallithraka, S.; Kotseridis, Y.; Drosinos, E.H. Effect of sulfur dioxide addition in wild yeast population dynamics and polyphenolic composition during spontaneous red wine fermentation from Vitis vinifera cultivar Agiorgitiko. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2014, 239, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linderholm, A.L.; Findleton, C.L.; Kumar, G.; Hong, Y.; Bisson, L.F. Identification of genes affecting hydrogen sulfide formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.E.; Bekker, M.Z.; Smith, P.A.; Wilkes, E.N. Sources of volatile sulfur compounds in wine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2015, 21, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartowsky, E.J.; Pretorius, I.S. Microbial Formation and Modification of Flavor and Off-Flavor Compounds in Wine. In Biology of Microorganisms on Grapes, in Must and in Wine; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.-Q.; Pilone, G.J. An overview of formation and roles of acetaldehyde in winemaking with emphasis on microbiological implications. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2000, 35, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, C. Production of sulfur dioxide-binding compounds and of sulfur dioxide by two Saccharomyces yeasts. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1969, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Divol, B.; Miot-Sertier, C.; Lonvaud-Funel, A. Genetic characterization of strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae responsible for “refermentation” in Botrytis-affected wines. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 100, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capece, A.; Siesto, G.; Romaniello, R.; Lagreca, V.M.; Pietrafesa, R.; Calabretti, A.; Romano, P. Assessment of competition in wine fermentation among wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains isolated from Sangiovese grapes in Tuscany region. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 54, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.J.; Jiménez, M.; Pastor, A.; Huerta, T. Yeast starter cultures affecting wine fermentation and volatiles. Food Res. Int. 2001, 34, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, G.; Moser, S.; Román, T.; Mazzi, E.; Larcher, R. Effect of juice turbidity on fermentative volatile compounds in white wines. Vitis - J. Grapevine Res. 2011, 50, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Herraiz, T.; Reglero, G.; Herraiz, M.; Martin-Alvarez, P.J.; Cabezudo, M.D. The influence of the yeast and type of culture on the volatile composition of wines fermented without sulfur dioxide. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1990, 41, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Saberi, S.; Cliff, M.A.; van Vuuren, H.J.J. Impact of mixed S. cerevisiae strains on the production of volatiles and estimated sensory profiles of Chardonnay wines. Food Res. Int. 2012, 48, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.; Carcel, C.; Dulau, L.; Samson, A.; Aguera, E.; Agosin, E.; Günata, Z. Influence of a mixed culture with Debaryomyces vanriji and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on the volatiles of a Muscat wine. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubeda Iranzo, J.F.; González Magaña, F.; González Viñas, M.A. Evaluation of the formation of volatiles and sensory characteristics in the industrial production of white wines using different commercial strains of the genus Saccharomyces. Food Control 2000, 11, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Metabolite | Abbreviation | Aroma | Threshold (µg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethyl esters | Ethyl acetate | EA | fruity, solvent a,b | 7500 |

| Ethyl propanoate | EP | fruity, solvent a,b | 1800 | |

| Ethyl 2-methylpropanoate | E2MP | Fruity a | 15 | |

| Ethyl butanoate | EB | apple, strawberry a | 20 | |

| Ethyl 2-methylbutanoate | E2MB | apple, strawberry a | 1–18 | |

| Ethyl 3-methylbutanoate | E3MB | apple, strawberry a | 3 | |

| Ethyl hexanoate | EH | fruity, fermented pear a | 5–14 | |

| Ethyl octanoate | EO | fruity, fatty b | 2 | |

| Ethyl decanoate | ED | Grape b | 200 | |

| Ethyl dodecanoate 1 | EDD | soapy, estery b | 25,619 * | |

| Acetates | 2-methylbutyl acetate 2 | 2MBA | Fruity b | 160 |

| 3-methylbutyl acetate 2 | 3MBA | Banana b | 30 | |

| Hexyl acetate | HA | fruity, herby b | 670 | |

| 2-phenylethyl acetate | 2PEA | rose, honey b | 250 | |

| Acids | 2-methylbutanoic acid 3 | 2MBAcid | butter, cheese b | 1500 |

| 3-methylbutanoic acid 3 | 3MBAcid | sweat, rancid b | 33.4 | |

| Hexanoic acid 1 | HAcid | sour, vinegar-like a | 420 | |

| Octanoic acid | OA | sweat, cheese a,b | 500 | |

| Decanoic acid | DA | Sour a, rancid/fatty b | 1000–8100 | |

| Alcohols | 2-methyl propanol | 2MP | roasted nuts a, solvent b | 40,000 |

| 2-methyl butanol 4 | 2MB | Onion b | 65,000 | |

| 3-methyl butanol 4 | 3MB | roasted nutsa, whisky b | 30,000 | |

| Hexanol | HOH | green, floral a,b | 8000 | |

| 2-phenylethanol | 2PE | honey, spice, floral b | 10,000–14,000 | |

| Benzyl alcohol | Benz | sweet, floral b | 900,000 | |

| Methionol | MOH | cooked potato a | 1000 |

| Source | df | SS | MS | Pseudo-F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast strain (Y) | 1 | 79.963 | 79.963 | 5.3215 | 0.002 * |

| Sulfite addition (S) | 1 | 43.755 | 43.755 | 2.9119 | 0.009 * |

| Y × S | 1 | 25.965 | 25.965 | 1.7279 | 0.13 |

| Residual | 12 | 180.32 | 15.026 | ||

| Total | 15 | 330 |

| Compound(s) | QA23 (0 mg/L SO2) | QA23 (50 mg/L SO2) | BRL97 (0 mg/L SO2) | BRL97 (50 mg/L SO2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA | 4.10 ± 0.13 | 4.21 ± 0.156 | 4.64 ± 0.41 | 3.96 ± 0.20 |

| EP | 0.206 ± 0.012 | 0.19 ± 0.007 | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 0.150 ± 0.016 |

| E2MP * | 0.081 ± 0.005 a | 0.08 ± 0.003 a | 0.103 ± 0.013 ab | 0.131 ± 0.011 b |

| EB | 0.334 ± 0.008 | 0.316 ± 0.018 | 0.421 ± 0.10 | 0.272 ± 0.003 |

| E2MB | 0.026 ± 0.0027 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 0.027 ± 0.004 | 0.033 ± 0.004 |

| E3MB | 0.025 ± 0.005 | 0.022 ± 0.003 | 0.0345 ± 0.006 | 0.033 ± 0.006 |

| 2MP * | 1.02 ± 0.066 a | 1.07 ± 0.027 ab | 0.928 ± 0.11 a | 1.35 ± 0.074 b |

| 2/3MBA * | 0.730 ± 0.020 a | 1.04 ± 0.031 b | 0.738 ± 0.041 a | 1.21 ± 0.042 c |

| 2/3MB * | 54.2 ± 1.7 ab | 55.7 ± 1.9 ab | 47.8 ± 1.4 a | 58.5 ± 3.1 b |

| EH | 11.1 ± 0.41 | 13.1 ± 0.82 | 13.2 ± 2.6 | 10.2 ± 1.3 |

| HA * | 0.322 ± 0.020 a | 0.57 ± 0.046 b | 0.386 ± 0.020 a | 0.581 ± 0.039 b |

| HOH | 3.57 ± 0.11 | 3.37 ± 0.05 | 3.45 ± 0.13 | 3.47 ± 0.11 |

| EO | 38.8 ± 3.0 | 45.0 ± 4.2 | 36.4 ± 4.2 | 40.0 ± 2.3 |

| ED | 11.7 ± 1.6 | 10.8 ± 1.2 | 9.61 ± 3.0 | 10.1 ± 0.90 |

| 2/3MBAcid * | 0.213 ± 0.010 ab | 0.196 ± 0.006 a | 0.236 ± 0.025 ab | 0.277 ± 0.014 b |

| MOH * | 0.066 ± 0.009 a | 0.078 ± 0.009 a | 0.0480 ± 0.0074 a | 0.122 ± 0.0076 b |

| 2PEA * | 1.28 ± 0.038 b | 1.65 ± 0.061 c | 0.843 ± 0.018 a | 1.35 ± 0.012 b |

| HAcid/EDD * | 2.44 ± 0.18 ab | 2.06 ± 0.13 ab | 2.66 ± 0.31 b | 1.71 ± 0.095 a |

| Benz | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.015 ± 0.001 | 0.016 ± 0.0007 |

| 2PE * | 35.1 ± 1.4 b | 41.84 ± 1.8 c | 22.3 ± 0.70 a | 32.2 ± 1.5 b |

| OA * | 4.85 ± 0.16 ab | 5.64 ± 0.063 b | 4.77 ± 0.33 a | 5.46 ± 0.10 ab |

| DA | 5.51 ± 0.19 | 5.71 ± 0.29 | 4.41 ± 1.1 | 4.84 ± 0.074 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morgan, S.C.; Haggerty, J.J.; Johnston, B.; Jiranek, V.; Durall, D.M. Response to Sulfur Dioxide Addition by Two Commercial Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains. Fermentation 2019, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation5030069

Morgan SC, Haggerty JJ, Johnston B, Jiranek V, Durall DM. Response to Sulfur Dioxide Addition by Two Commercial Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains. Fermentation. 2019; 5(3):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation5030069

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorgan, Sydney C., Jade J. Haggerty, Britney Johnston, Vladimir Jiranek, and Daniel M. Durall. 2019. "Response to Sulfur Dioxide Addition by Two Commercial Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains" Fermentation 5, no. 3: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation5030069

APA StyleMorgan, S. C., Haggerty, J. J., Johnston, B., Jiranek, V., & Durall, D. M. (2019). Response to Sulfur Dioxide Addition by Two Commercial Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains. Fermentation, 5(3), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation5030069