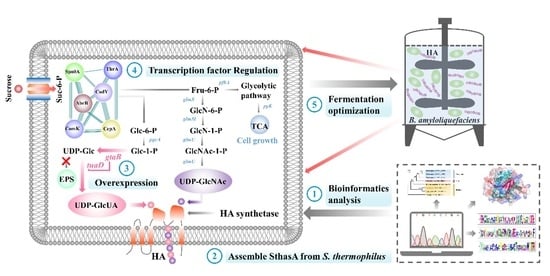

Heterologous Biosynthesis of Hyaluronic Acid Using a New Hyaluronic Acid Synthase Derived from the Probiotic Streptococcus thermophilus

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

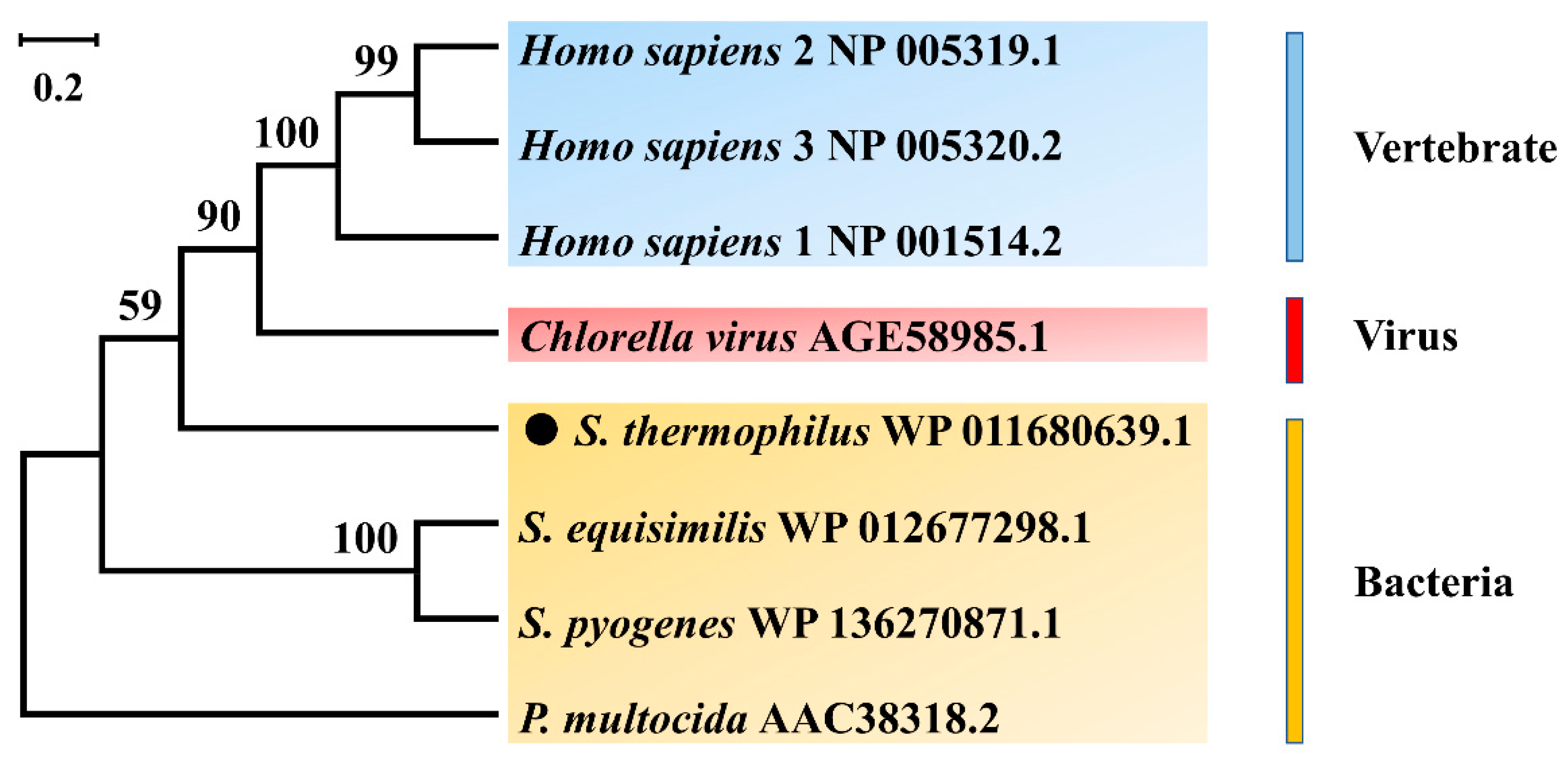

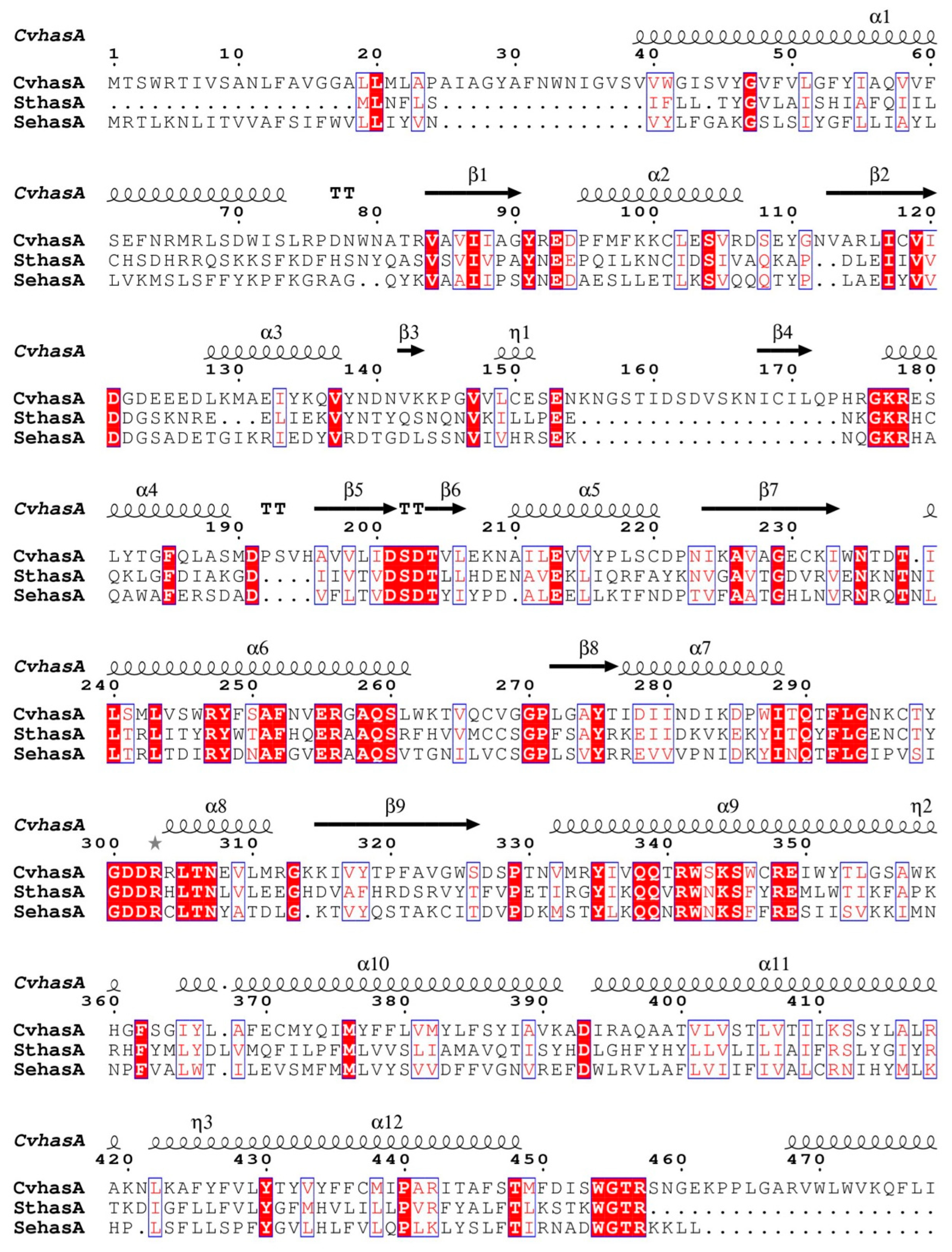

2.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.3. Construction of the Recombinant Strains

2.4. Studies on Global Transcription Regulators

2.5. Box–Behnken Design and Response Surface Methodology Experiment

2.6. HA Overproduction in a 5 L Fermenter

2.7. Analytical Method

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Bioinformatics Analysis of a New HAS (SthasA) from S. thermophilus

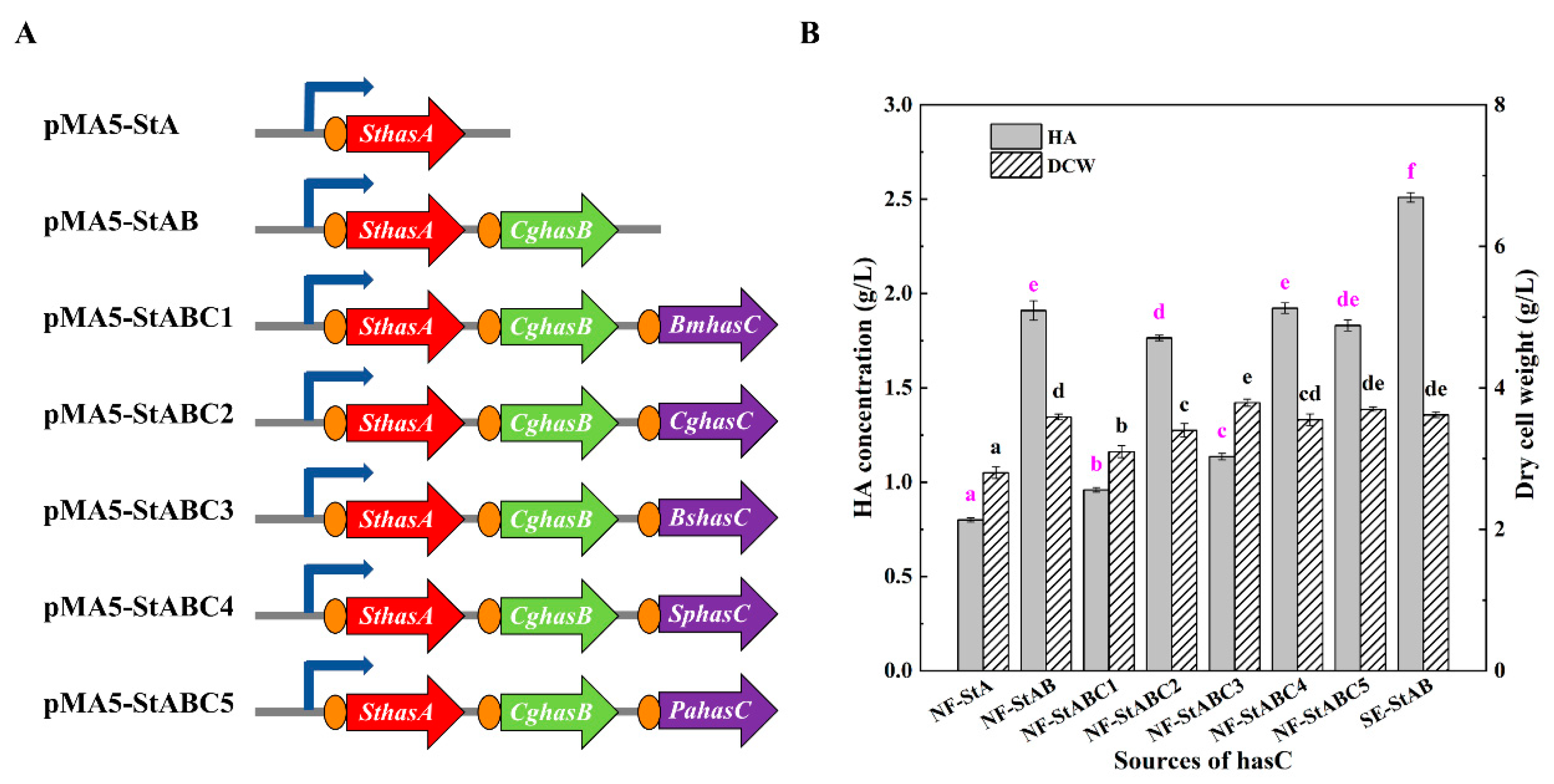

3.2. Construction and Optimization of the HA Synthesis Pathway in B. amyloliquefaciens

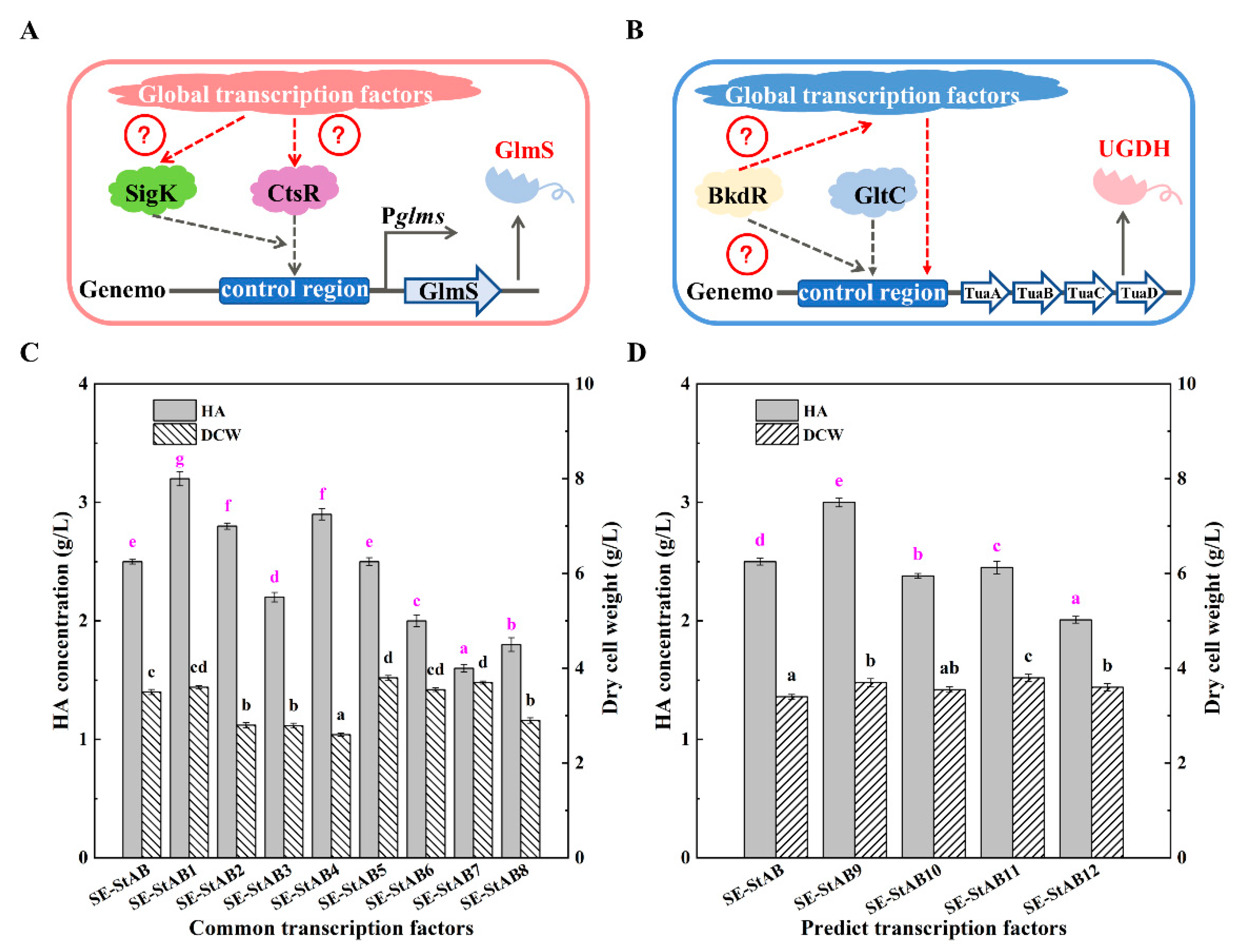

3.3. Study on Global Transcriptional Regulators of HA Synthesis in B. amyloliquefaciens

3.4. Culture Medium Optimization for HA Yield using Response Surface Methodology

3.5. Batch Fermentation Optimization of HA Production in a 5 L Fermenter

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Du, G.; Chen, J. Bio-Based Strategies for Producing Glycosaminoglycans and Their Oligosaccharides. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Kusche-Gullberg, M. Heparan Sulfate: Biosynthesis, Structure, and Function. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016, 325, 215–273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- How, K.N.; Yap, W.H.; Lim, C.L.H.; Goh, B.H.; Lai, Z.W. Hyaluronic Acid-Mediated Drug Delivery System Targeting for Inflammatory Skin Diseases: A Mini Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Zou, Y.; Xu, W. Research Progress on Preparation and Application of Hyaluronic Acid. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2022, 43, 440–447. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Xu, H.; Su, E. Current advances in the biosynthesis of hyaluronic acid with variable molecular weights. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 269, 118320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ialenti, A.; Di Rosa, M. Hyaluronic acid modulates acute and chronic inflammation. Agents Actions 1994, 43, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witting, M.; Boreham, A.; Brodwolf, R.; Vávrová, K.; Alexiev, U.; Friess, W.; Hedtrich, S. Interactions of hyaluronic Acid with the skin and implications for the dermal delivery of biomacromolecules. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.R.; Hammon, K.A.; Gafner, A.; Dahl, A.; Guttman, N.; Fong, M.; Schauss, A.G. Novel Hydrolyzed Chicken Sternal Cartilage Extract Improves Facial Epidermis and Connective Tissue in Healthy Adult Females: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2019, 25, 12–29. [Google Scholar]

- Boeriu, C.; Springer, J.; Kooy, F.; Broek, L.; Eggink, G. Production Methods for Hyaluronan. Int. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2013, 2013, 624967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Ren, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, G. Efficient production of high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid with a two-stage fermentation. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 36167–36171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miranda, R.B.; Weimer, P.; Rossi, R.C. Effects of hydrolyzed collagen supplementation on skin aging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 1449–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.B.; Ramachandran, K.B.; Jayaraman, G. Transcription analysis of hyaluronan biosynthesis genes in Streptococcus zooepidemicus and metabolically engineered Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 94, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmar, R.V.; Prasad, S.B.; Jayaraman, G.; Ramachandran, K.B. Chromosomal integration of hyaluronic acid synthesis (has) genes enhances the molecular weight of hyaluronan produced in Lactococcus lactis. Biotechnol. J. 2014, 9, 1554–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, J.; Sieber, V.; Rehm, B. Bacterial exopolysaccharides: Biosynthesis pathways and engineering strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, P.; Kang, Z.; Yuan, P.; Du, G.; Chen, J. Production of specific-molecular-weight hyaluronan by metabolically engineered Bacillus subtilis 168. Metab. Eng. 2016, 35, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Luozhong, S.; Guo, Z.; Yu, H.; Stephanopoulos, G. Enhanced Biosynthesis of Hyaluronic Acid Using Engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum Via Metabolic Pathway Regulation. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 12, 1700191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Yu, C.; Li, S.; Xu, H. Design and construction of a Bacillus amyloliquefaciens cell factory for hyaluronic acid synthesis from Jerusalem artichoke inulin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 205, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Sha, Y.; Lei, P.; Zhengshan, L.; Feng, X.; Li, S.; Xu, H. Development of a Robust Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Cell Factory for Efficient Poly(γ-glutamic acid) Production from Jerusalem Artichoke. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 9763–9774. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Du, S.; Yan, Y.; Pan, F.; Wang, R.; Li, S.; Xu, H.; Luo, Z. Systematic engineering of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens for efficient production of poly-γ-glutamic acid from crude glycerol. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Du, S.; Pan, F.; Li, S.; Xu, H.; Luo, Z. Metabolic Engineering of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens to Efficiently Synthesize L-Ornithine from Inulin. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 905110. [Google Scholar]

- Khuri, S.; Bakker, F.T.; Dunwell, J.M. Phylogeny, function, and evolution of the cupins, a structurally conserved, functionally diverse superfamily of proteins. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001, 18, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maloney, F.P.; Kuklewicz, J.; Corey, R.A.; Bi, Y.; Ho, R.; Mateusiak, L.; Pardon, E.; Steyaert, J.; Stansfeld, P.J.; Zimmer, J. Structure, substrate recognition and initiation of hyaluronan synthase. Nature 2022, 604, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broeker, N.K.; Gohlke, U.; Müller, J.J.; Uetrecht, C.; Heinemann, U.; Seckler, R.; Barbirz, S. Single amino acid exchange in bacteriophage HK620 tailspike protein results in thousand-fold increase of its oligosaccharide affinity. Glycobiology 2013, 23, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelly, J.C.; Lin, H.Y.; de Brevern, A.G.; Chuang, T.J.; Chen, F.C. Selective constraint on human pre-mRNA splicing by protein structural properties. Genome Biol. Evol. 2012, 4, 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widner, B.; Behr, R.; Von Dollen, S.; Tang, M.; Heu, T.; Sloma, A.; Sternberg, D.; Deangelis, P.L.; Weigel, P.H.; Brown, S. Hyaluronic acid production in Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 3747–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahooti, M.; Harwood, C.R. Transcriptional analysis of the Bacillus subtilis teichuronic acid operon. Microbiology 1999, 145, 3409–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeeswara Reddy, K.; Karunakaran, K. Purification and characterization of hyaluronic acid produced by Streptococcus zooepidemicus strain 3523-7. J. BioSci. Biotechnol. 2020, 2, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Welti, D.; Rees, D.A.; Welsh, E.J. Solution conformation of glycosaminoglycans: Assignment of the 300-MHz 1H-magnetic resonance spectra of chondroitin 4-sulphate, chondroitin 6-sulphate and hyaluronate, and investigation of an alkali-induced conformation change. Eur. J. Biochemi. 1979, 94, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngör, G.; Gedikli, S.; Toptaş, Y.; Sezgin, D.; Demirbilek, M.; Yazihan, N.; Aytar Çelik, P.; Denkbas, E.; Çabuk, A. Bacterial hyaluronic acid production through an alternative extraction method and its characterization. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 94, 1843–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, H.; Moxley, J.; Nevoigt, E.; Fink, G.R.; Stephanopoulos, G. Engineering yeast transcription machinery for improved ethanol tolerance and production. Science 2006, 314, 1565–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wu, H.; Bai, Y.P. Transcription Factor Engineering for High-Throughput Strain Evolution and Organic Acid Bioproduction: A Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Villatoro-Hernandez, J.; Weme, R.D.O.; Frenzel, E.; Kuipers, O.P. Boosting heterologous protein production yield by adjusting global nitrogen and carbon metabolic regulatory networks in Bacillus subtilis. Metab. Eng. 2018, 49, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Z.; Teo, C.H. Cloning and expression of hyaluronan synthase (hasA) in recombinant Escherichia coli BL21 and its hyaluronic acid production in shake flask culture. Malays. J. Microbiol. 2019, 15, 575–582. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Zhong, Q.; Liu, J.; Yang, F.; Lu, C.; Xiong, H.; Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, L. Efficient expression of chondroitinase ABC I for specific disaccharides detection of chondroitin sulfate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 143, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westbrook, A.W.; Ren, X.; Moo-Young, M.; Chou, C.P. Application of hydrocarbon and perfluorocarbon oxygen vectors to enhance heterologous production of hyaluronic acid in engineered Bacillus subtilis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018, 115, 1239–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, L.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Du, G.; Kang, Z. Eliminating the capsule-like layer to promote glucose uptake for hyaluronan production by engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, X.; Tang, D.; Su, D.; Yao, W.; Gao, X. Metabolic engineering of Bacillus subtilis for the efficient biosynthesis of uniform hyaluronic acid with controlled molecular weights. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 132, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Yu, H.; Stephanopoulos, G. Engineering Corynebacterium glutamicum for high-titer biosynthesis of hyaluronic acid. Metab. Eng. 2019, 55, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunguroğlu, C.; Sezgin, D.E.; Aytar Çelik, P.; Çabuk, A. Higher titer hyaluronic acid production in recombinant Lactococcus lactis. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 48, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain or Plasmid | Relevant Characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | F-, φ80dlacZΔM1, Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169, deoR, recA1, endA1, hsdR17 (rk-, mk+), phoA, supE44, λ − thi-1, gyrA96, relA1 | This lab |

| E. coli GM2163 | F-, ara-14 leuB6 thi-1 fhuA31 lacY1 tsx-78 galK2 galT22 supE44 hisG4 rpsL 136 (Strr) xyl-5 mtl-1 dam13::Tn9 (Camr) dcm-6 mcrB1 hsdR2 mcrA | This lab |

| B. amyloliquefaciens NB | NX-2S derivate, BamHI::PHpaII-pgsR | This lab |

| B. amyloliquefaciens NF | NBΔpgsBCA | This lab |

| B. amyloliquefaciens SE | NFΔepsA-OΔsacB | This lab |

| pMA5 | E. coli and B. amyloliquefaciens Shuttle expression vector; AmpR, KmR | This study |

| pMA5-StA | pMA5 derivate consists of the SthasA gene between BamHI and NdeI | This study |

| pMA5-StAB | pMA5-StA derivate consists of the tuaD gene CghasB | This study |

| pMA5-StABC1 | pMA5-StAB derivate consists of the gtaB gene BmhasC | This study |

| pMA5-StABC2 | pMA5-StAB derivate consists of the gtaB gene CghasC | This study |

| pMA5-StABC3 | pMA5-StAB derivate consists of the gtaB gene BshasC | This study |

| pMA5-StABC4 | pMA5-StAB derivate consists of the gtaB gene SphasC | This study |

| pMA5-StABC5 | pMA5-StAB derivate consists of the gtaB gene PahasC | This study |

| pMA5-StAB1 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene CcpA | This study |

| pMA5-StAB2 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene CodY | This study |

| pMA5-StAB3 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene ThrA | This study |

| pMA5-StAB4 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene ComK | This study |

| pMA5-StAB5 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene Spo0A | This study |

| pMA5-StAB6 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene AbrB | This study |

| pMA5-StAB7 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene Rex | This study |

| pMA5-StAB8 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene FruR | This study |

| pMA5-StAB9 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene BkdR | This study |

| pMA5-AB10 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene CtsR | This study |

| pMA5-StAB11 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene GltC | This study |

| pMA5-StAB12 | pMA5-AB derivate consists of the translation factor gene SigA | This study |

| Assay | Factors | HA Concentration (g/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | Observed | Predicted | |

| 1 | 25.00 (−1) | 5.00 (−1) | 6.00 (0) | 4.35 ± 0.03 | 4.36 |

| 2 | 55.00 (1) | 5.00 (−1) | 6.00 (0) | 3.95 ± 0.06 | 3.94 |

| 3 | 25.00 (−1) | 15.00 (1) | 6.00 (0) | 3.85 ± 0.06 | 3.86 |

| 4 | 55.00 (1) | 15.00 (1) | 6.00 (0) | 4.29 ± 0.10 | 4.29 |

| 5 | 25.00 (−1) | 10.00 (0) | 4.00 (−1) | 3.61 ± 0.08 | 3.61 |

| 6 | 55.00 (1) | 10.00 (0) | 4.00 (−1) | 3.56 ± 0.11 | 3.58 |

| 7 | 25.00 (−1) | 10.00 (0) | 8.00 (1) | 3.79 ± 0.09 | 3.77 |

| 8 | 55.00 (1) | 10.00 (0) | 8.00 (1) | 3.81 ± 0.10 | 3.81 |

| 9 | 40.00 (0) | 5.00 (−1) | 4.00 (−1) | 3.63 ± 0.08 | 3.63 |

| 10 | 40.00 (0) | 15.00 (1) | 4.00 (−1) | 3.80 ± 0.03 | 3.79 |

| 11 | 40.00 (0) | 5.00 (−1) | 8.00 (1) | 4.06 ± 0.10 | 4.07 |

| 12 | 40.00 (0) | 15.00 (1) | 8.00 (1) | 3.76 ± 0.10 | 3.76 |

| 13 | 40.00 (0) | 10.00(0) | 6.00 (0) | 4.82 ± 0.06 | 4.82 |

| 14 | 40.00 (0) | 10.00 (0) | 6.00 (0) | 4.82 ± 0.08 | 4.82 |

| 15 | 40.00 (0) | 10.00 (0) | 6.00 (0) | 4.83 ± 0.10 | 4.82 |

| 16 | 40.00 (0) | 10.00 (0) | 6.00 (0) | 4.81 ± 0.06 | 4.82 |

| 17 | 40.00 (0) | 10.00 (0) | 6.00 (0) | 4.84 ± 0.04 | 4.82 |

| Source | SS a | DF b | MS c | F-Value | Probe > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 3.89 | 9 | 0.43 | 2355.53 | <0.0001 d |

| X1 | 1.7 × 10−5 | 1 | 1.69 × 10−5 | 0.092 | 0.7702 |

| X2 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.01 | 58.83 | 0.0001 |

| X3 | 0.08 | 1 | 0.08 | 443.63 | <0.0001 d |

| X1X2 | 0.18 | 1 | 0.18 | 956.21 | <0.0001 d |

| X1X3 | 1.18 × 10−3 | 1 | 1.18 × 10−3 | 6.45 | 0.0387 |

| X2X3 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.06 | 303.50 | <0.0001 d |

| X12 | 0.73 | 1 | 0.73 | 3974.35 | <0.0001 d |

| X22 | 0.37 | 1 | 0.37 | 2003.03 | <0.0001 d |

| X32 | 2.15 | 1 | 2.15 | 11729.38 | <0.0001 d |

| Residual | 1.28 × 10−3 | 7 | 1.83 × 10−4 | - | - |

| Lack of Fit | 8.17 × 10−4 | 3 | 2.72 × 10−4 | 2.33 | 0.2155 |

| Pure Error | 4.67 × 10−4 | 4 | 1.17 × 10−4 | - | - |

| Cor Total | 3.89 | 16 | - | - | - |

| Strain | HAS Source | Carbon Source | Yield (g/L) | MW (Da) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis 168 | S. zooepidemicus | Sucrose | 19.38 | 6.6 × 103 | [15] |

| C. glutamicum 13032 | S. pyogenes | Glucose | 74.10 | 5.3 × 104 | [36] |

| S. equisimilis | Glucose | 28.7 | 2.1 × 105 | [38] | |

| B. subtilis 168 | P. multocida | Glucose | 6.80 | 4.6 × 106 | [37] |

| L. lactis CES15 | S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus | Sucrose | 6.09 | - | [39] |

| B. amyloliquefaciens CF-AB | S. equisimilis | Jerusalem artichoke inulin | 2.89 | 1.5 × 106 | [17] |

| B. amyloliquefaciens SE-StAB | S. thermophilus | Sucrose | 5.78 | 1.7 × 106 | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, Q.; Ma, Y.; Xu, D.; Lei, P.; Li, S.; Xu, H.; Qiu, Y. Heterologous Biosynthesis of Hyaluronic Acid Using a New Hyaluronic Acid Synthase Derived from the Probiotic Streptococcus thermophilus. Fermentation 2023, 9, 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9060510

Zhong Q, Ma Y, Xu D, Lei P, Li S, Xu H, Qiu Y. Heterologous Biosynthesis of Hyaluronic Acid Using a New Hyaluronic Acid Synthase Derived from the Probiotic Streptococcus thermophilus. Fermentation. 2023; 9(6):510. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9060510

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Qian, Yanqin Ma, Delei Xu, Peng Lei, Sha Li, Hong Xu, and Yibin Qiu. 2023. "Heterologous Biosynthesis of Hyaluronic Acid Using a New Hyaluronic Acid Synthase Derived from the Probiotic Streptococcus thermophilus" Fermentation 9, no. 6: 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9060510

APA StyleZhong, Q., Ma, Y., Xu, D., Lei, P., Li, S., Xu, H., & Qiu, Y. (2023). Heterologous Biosynthesis of Hyaluronic Acid Using a New Hyaluronic Acid Synthase Derived from the Probiotic Streptococcus thermophilus. Fermentation, 9(6), 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9060510