1. Introduction

The study of ethnic identity development among mixed-background individuals is a growing field of study, as they represent a very diverse group whose experiences are rather unique (

Benet-Martínez and Haritatos 2005). This includes the way in which they develop and experience a sense of ethnic identity (or, in many cases, identities) and integration into the society where they live. The study of this heterogenous group has two important characteristics: (i) it is contextual, as what might be considered as mixed in one place might not be considered as such in another one (

Rodríguez-García 2015), and (ii) it is temporal, as people and attributes that were considered as members of a different group at a certain point in history might no longer be considered as such in our days (

Varro 2012).

In this study, the interviewed group was formed by parents of (Estonian–foreign) children living in Estonia. The term binational is used to refer to this group of families, as parents’ identities have developed in the context of different national states (

Fresnoza-Flot and Ricordeau 2017). This means that parents have what authors describe as a different national mental programme, which implies a particular relationship with the institutions, culture, and mentality of their country, which makes them react in particular ways across different areas of their life (

Gaspar 2008;

Hofstede 1993). National-foreign binational groups represent a subsegment of mixed-background populations that remains understudied in comparison to other groups. This is because old beliefs, such as the high level of integration or even automatic assimilation of the foreign partner resulting from their union with a local, among other misconceptions, have eclipsed their study (

Rodríguez-García et al. 2015;

Song 2009).

This article explores the role that identity complexity plays in the development of ethnic identity and acculturation outcomes among parents of binational (Estonian–foreign) children. Authors have explored the effect of intersectional characteristics such as gender, race, ethnicity, and social class among a variety of mixed-background populations on this process (

Benet-Martínez and John 1998;

Cheon et al. 2020;

Gaspar 2012;

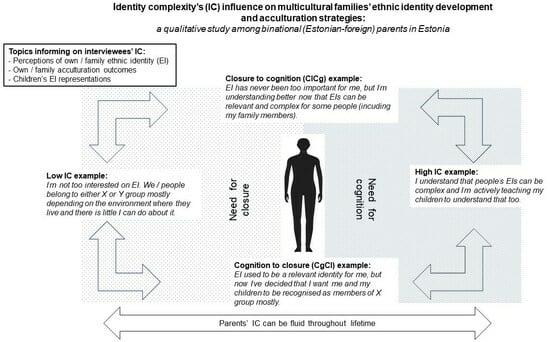

Mateos 2019). Nevertheless, this article proposes that other factors that might not be so visible, such as identity complexity, might also be very consequential. Social identity complexity theory suggests that individuals experience and report their belonging to different social identities (including ethnic identity) with different levels of complexity (

Miller et al. 2009;

Roccas and Brewer 2002). In this respect, most studies present a dichotomy—high identity complexity (HIC) vs. low identity complexity (LIC). HIC has been associated with cognitive strategies such as the need for cognition—a disposition to find more information to understand the different aspects of a particular subject, as well as with tolerant attitudes towards diversity and inclusiveness. Conversely, LIC is associated with the need for closure (i.e., being black or white), intergroup intolerance, and distinctiveness threat (

Brewer and Pierce 2005;

Knifsend and Juvonen 2014;

Miller et al. 2009;

Schmid et al. 2009;

Webster and Kruglanski 1994).

The identity complexity of parents of binational (Estonian–foreign) children was measured through interviews where they were prompted to talk about how they have experienced their own ethnic identity(ies), e.g., how they would describe themselves ethnically and how important ethnic identity has been throughout their lifetime, their (and their family’s) feelings of integration into the Estonian society plus, the way in which they represent their children’s ethnic identities, e.g., mostly Estonian/foreign, fifty–fifty, global citizen, etc. This contributes to the research on mixed-background individuals for a number of reasons. Firstly, even if the purpose was to interview the most diverse sample of parents, most of the interviewed informants can be described as cosmopolitan, as they are people who live and/or work in international environments (

Weenink 2008). Literature indicates that cosmopolitans enjoy different privileges, e.g., international mobility, integration dispensation, etc. (

Favell 2008;

Klarenbeek 2021). However, this group is, in many cases, treated as quite homogenous, and therefore, further research is necessary to understand their diversity (

Gaspar 2010). As an example of this, they might use a variety of coping strategies to cultivate (or in some cases, restrain from cultivating) different aspects of their families, such as the maintenance and transmission of language(s), cultural and religious practices as well as their children’s choice of names, citizenship, place of residence and schooling, as well as how they negotiate them with their partners and the society where they live. In a nutshell, this article treats cosmopolitans as a more heterogenous group from this angle.

Secondly, the fact that local parents were also interviewed (in this case, Estonians) represents a relatively unexplored feature, which acknowledges that local partners can also experience the acculturation process of their foreign partners and of their mixed-background children in different ways (

Fresnoza-Flot and Ricordeau 2017). In this case, too, identity complexity might be an influential element. Finally, the literature suggests that mixed-background individuals’ identity representations contain powerful meanings about how they and other people around them perceive and experience their ethnic identities and their relationship with the society where they live (

Huynh et al. 2011;

Roccas and Brewer 2002;

Rodríguez-García 2015). Nevertheless, this article proposes that certain ethnic identity representations might have different meanings for different individuals in the studied group. In particular, the so-called global identity, which is common among cosmopolitans, deserves special attention. Finally, this article explores identity complexity as a more fluid and multidimensional concept than in previous studies (

Knifsend and Juvonen 2014;

Schmid et al. 2009). This means that individuals might fluctuate between the need for cognition and the need for closure, and the other way around, at different points in their life and for different reasons, just like they can move between the identity development stages of exploration, foreclosure, and achievement (

Phinney 1989,

1990). If that is the case, the dichotomy of high vs. low identity complexity might present more dimensions than previously explored.

Identity Complexity and Its Interplay with Ethnic Identity Development and Acculturation

Identity complexity refers to the way in which individuals recognise, experience, and express overlaps between the different social groups to which they belong, e.g., ethnicity, occupation, political and religious affiliation, etc. (

Roccas and Brewer 2002). Individuals with low identity complexity perceive strong and fixed overlaps between their and other people’s different social identities; for that reason, they tend to provide simple answers when asked to elucidate about them, e.g., I am/they are (just/only/simply) X and not Y or, all Ys are Zs. In contrast, individuals with high identity complexity accept perceived non-overlapping social identities and can provide more elaborate answers in an effort to explain the intricate connections of their own and other people’s different identities, e.g., I am/they are X and Y and (sometimes), I/they can also be Z.

The purpose of this study is not to provide a scale but to explore the variety of ways in which identity complexity can influence the perceptions and attitudes towards ethnic identity and acculturation of a group formed by parents of binational (Estonian–foreign) children. In order to achieve this, they were asked questions related to three main topics: (i) their perceptions of their own ethnic identity development, (ii) their feelings of acculturation (or, in the case of local parents, the acculturation of their family), and (iii) the way in which they describe their children’s ethnic identity(ies).

With regards to the first topic, authors have found associations between identity complexity and measures of cognitive style, such as the need for cognition, the need to engage and enjoy effortful cognitive activity (

Cacioppo et al. 1984), and the need for closure—a desire for predictability and discomfort with ambiguity (

Webster and Kruglanski 1994). In addition, research has shown that individuals with high identity complexity usually embrace more liberal ideas, are more tolerant of outgroups, and are acceptant of diversity and inclusiveness (

Brewer 2010;

Brewer and Pierce 2005). There are studies that focus on ethnic identity development outcomes among mixed-background individuals, and associations have been found between some intersectional characteristics such as race, gender, and ethnicity (

Huynh et al. 2011). However, the effects that identity complexity (and the cognitive strategies associated with it) have on the way ethnic identity is perceived as a more salient and valuable type of social identity among this group have not been explored. Parents of mixed-background individuals represent one of the most important antecedents of their ethnic identity development (

Gonzales-Backen 2013) but remain an understudied group. In particular, the literature indicates an existent research gap among binational families—traditionally a cosmopolitan group in Western societies (

Gaspar 2010;

Rodríguez-García 2015)—who are perceived as being somehow beyond the notion of ethnic identity and are usually more associated with concepts such as world or global citizenship. Finally, many articles on identity complexity present a dichotomy—high versus low identity complexity (

Knifsend and Juvonen 2014;

Schmid et al. 2009). Based on the premise that ethnic identity has different stages of development throughout an individual’s lifetime (

Phinney 1989,

1990), this study explores whether identity complexity can also be a more fluid element and whether there are any other layers beyond this traditional dichotomy.

For the second topic, the purpose of this study is not to determine informants’ acculturation outcomes but to assess how identity complexity interplays with their acculturation strategies. Berry’s acculturation theory (

Berry 1990) was used to determine informants’ acculturation, as it provides outcomes from the perspective of immigrant groups: integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalisation, as well as corresponding outcomes from the perspective of the host society: multiculturalism, melting pot, segregation and exclusion (

Berry 2011). Binational families, particularly in Western societies, are a middle-class phenomenon (

Rodríguez-García 2015), and many of them live and/or work in cosmopolitan environments. As a result of this, they might enjoy what authors call integration dispensation (

Klarenbeek 2021;

Saharso 2019). On the other hand, their acculturation challenges, e.g., a strong sense of in-betweenness among EU free-moving couples, have remained concealed and require further research (

Gaspar 2010). With that in mind, this study focuses on exploring the influence of the identity complexity of informants from the studied group on their acculturation outcomes, as well as the meaning they give to them. For example, it will be explored whether informants’ positions towards integration, multiculturalism, or global citizenship have similar meanings for informants based on their identity complexity.

Finally, for what concerns ethnic identity representations, authors have found that the ways in which mixed-background individuals casually express their ethnic identity(ies) contain very important messages about how they experience them (

Roccas and Brewer 2002). Authors refer to these as identity representations and are generally classified as follows: (i) blended, e.g., Estonian–foreign or fifty–fifty; (ii) dominant, e.g., predominantly Estonian/foreign; (iii) compartmentalised, e.g., Estonian in Estonian environments and French in French environments; (iv) merged, e.g., Estonian and foreign (100% and 100%); and (v) integrated biculturalism, e.g., world/global citizens (

Huynh et al. 2011). As mentioned before, parents are a relevant antecedent of ethnic identity among mixed-background individuals. Nevertheless, there is not much information about the way in which parents influence the way in which mixed-background individuals express their ethnic identities. This information is even more limited among binational family parents, among which studies available focus mostly on the choice of names and transmission of languages (

Cerchiaro 2017;

Le Gall and Meintel 2015). Just like in the case of acculturation, this article tries to explore the ethnic identity representations parents give to their children in a less fixed way in comparison to previous studies and looks at whether these have similar meanings for informants depending on their identity complexity, e.g., does global citizenship or fifty–fifty mean the same for informants with high or low identity complexity?

2. Materials and Methods

Individual semi-structured interviews (

Leech 2002) were conducted among binational (Estonian–foreign) family parents between January 2022 and June 2023 by the author of this article. Informants participated voluntarily and were identified and contacted through social media groups for foreign people living in Estonia, combined with snowball recruitment (

Leighton et al. 2021). The fact that the author of this article is a parent of binational (Estonian–foreign) children and lives in Estonia facilitated recruitment among the segment of recruited parents, as well as their openness during the interviews.

In total, forty participants were recruited and interviewed. Twenty of them were Estonian, and the rest had other nationalities that were categorised as follows: (i) other European Union (EU): Dutch, French, Latvian, Romanian, Spanish, and Italian; (ii) other Global North: British, Japanese, and American; and (iii) Global South: Brazilian, Lebanese, Iranian, and Mexican. Most participants were couples with common children. However, they were treated as individual informants as the purpose of this study was not to compare common or divergent positions between couple members. In addition, a few participants had children from previous or new unions (some of which are not binational children), and, in two cases, one partner from two different participating couples decided not to participate in the interviews but allowed their partners to participate instead. After responding to the recruitment call, participants were provided with an information sheet explaining the purpose of the research and its confidential nature. They were also given the option to receive the interview guide questionnaire in advance of the interview. After the interviews, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire with control questions. Control information revealed that most informants had young children. Most informants also expressed that they use their mother tongue to communicate with their children and use the English language to communicate with their partners.

Table 1 shows a breakdown of participants based on gender, age group, level of education, and Estonian/foreign background.

Interviews extracted relevant information about participants’ identity complexity, integration attitudes, and the way in which they represent their children’s ethnic identity(ies). They were conducted separately to allow participants to express their views more freely and had a duration of forty-five minutes. A guide questionnaire was prepared to ensure that all three topics were covered. It included questions such as, “How would you describe your ethnic identity and the ethnic identity of your children?” or “How integrated do you and your family feel in the place where you currently live?”. Nevertheless, every interview was semi-structured and varied depending on the personality and disposition of the informant, as well as on their capacity to understand and speak about concepts such as ethnic identity and acculturation. This was particularly the case among participants with low identity complexity, with whom questions had to be rephrased several times or additional questions had to be asked to prompt their answers.

Prior to the interviews, participants expressed their consent to record the interviews and were informed both verbally and through an information sheet that identification markers would be removed from their quotes to protect the confidential nature of the interviews. Interviews were carried out using videoconference software, such as Zoom and Teams, depending on the preference of participants. This made it possible to communicate with participants living in different locations, as well as coordinate to arrange interview times most convenient to the interviewees.

Using videoconference software also facilitated subsequent interview recording and transcription, which was agreed upon with participants in advance. Transcription was made by using the MS Word transcription functionality. Most interviews were conducted in English. However, other languages, e.g., Spanish, were used in cases where this made communication with participants easier.

Interview analyses started by determining whether informant answers revealed if they mostly perceived or not any overlaps when they spoke about ethnic identity and acculturation throughout the interviews.

Table 2 presents a summary of how participants formulated their positions towards the three interview topics according to the identified identity complexity group in which they were classed after the analysis: (i) high identity complexity (HIC)—mostly perceives overlaps; (ii) closure to cognition (ClCg)—increasingly perceives overlaps; (iii) cognition to closure (CgCl)—decided not to perceive any more overlaps; and (iv) low identity complexity (LIC)—mostly does not perceive overlaps.

Subsequently, thematic analysis was used to identify excerpts from the interviews that would show patterns and could be grouped into meaningful codes, which would show the variety of positions informants expressed across the interview topics—ethnic identity, acculturation, and children’s ethnic identity representations. These topics represented the analyses’ themes. Respondents’ comments on acculturation were coded and grouped in subthemes based on Berry’s acculturation theory, which considers outcomes from the points of view of both the newly arrived and the host society, e.g., integration /multiculturalism, assimilation/melting pot, separation/segregation, and marginalisation/exclusion (

Berry 2011). Ethnic identity representations were classed based on Roccas and Brewer’s classification (

Roccas and Brewer 2002).

Although the logic behind the analysis of respondent answers was deductive and, therefore, presented risks in its interpretation, the idea was to explore how the way in which they talked about the different topics contained in the interviews revealed their identity complexity. This process was not expected to be linear, unidimensional, or perfectly congruent, as concepts such as ethnic identity and integration can be, as mentioned earlier, per se difficult concepts to grasp and explain, particularly for respondents who might not be too close to them.

Finally, when transcribing quotes, all markers that could lead to the identification of participants were modified to protect their confidentiality, e.g., country names, number, and, in some cases, gender of children were modified. Informants were only identified by a code indicating the identity complexity group in which the interviewee was classed, their gender, and the interviewed couple number, e.g., HICF1 means “high identity complexity, female, couple 1”.

3. Results

The results show the variety of ways in which interviewed parents expressed their identity complexity. The topic that incited informants to start talking was ethnic identity, where informants with HIC were more able to elucidate on this topic and explain how their identities are formed by different elements that are not always convergent. As an example of this, some interviewed parents in this group mentioned that they ascribe in general to (a) certain ethnic group(s). In some cases, they expressed that they feel the need to justify that ascription when other people, either from those same groups or third groups, perceive that there is a mismatch between their expressed ethnic identity and elements such as observable physical traits, name, cultural or religious practices: “I’m Arab-African but I was born and raised in the Netherlands (…) When people ask me where I’m from, I tend to say that I’m Dutch but, very often I feel the need to explain a little bit of the complexity of the influences with which I grew up” (HICFF2).

HIC was expressed not only by interviewed parents with perceived salient non-converging traits but also by Estonian informants, who, in the case of this study, represent the dominant majority group: “Oh, that’s a very difficult question (to describe my ethnic identity), because, uh, you know, Estonians are also a mix of different nations. So, my father, he was Russian and my mother, she is Estonian, but we have always known that her relatives are from their Livonia area, which is like southern Estonia and partly like Latvia like northern Latvia. So ethnically, yeah, I’ve always thought them a mix, but I’ve grown up in the Estonian culture, and I think I’m Estonian”. (HICEF4). Conversely, for informants with LIC, it was more difficult to talk about ethnic identity in general. Expressions such as “I’ve never thought about it” or “I don’t think that ethnic identity is important” were recurrent among informants in this category. and in some cases, they could only associate it with the notion of race: “(I’d describe myself) as white Caucasian. (Interviewer: What elements do you see in that definition?) The informant shows the colour of the skin on his face and says: Isn’t it obvious? (…) It’s my appearance and my background, my parents.” (LICEM16).

In summary, the HIC/LIC dichotomy presented clear distinctions among informants’ attitudes and perceptions across the interview topics. While ethnic identity and integration were mostly relevant notions among HIC informants, LIC informants showed opposite attitudes, which were more related to the need for a closure strategy.

Nevertheless, in between the HIC and LIC groups, two other groups were revealed, in which answers were more ambiguous. The main characteristic of these groups is that they seem to have migrated from one cognition strategy to another at this point in their lives. Therefore, they are denominated in this article as the cognition to closure (CgCl) and the closure to cognition (ClCg) groups.

For informants in the latter ClCg group, ethnic identity and integration have not played a significant role in their lives. However, they expressed that they have somehow transitioned from a black or white attitude towards a more open disposition towards identity complexity, which they seem to have acquired and developed in the places where they grew up or have worked: “I was born and raised in the UK, where we have an open mindset, I think. But I’m working in an international company where there’s like so many other nationalities as well, so only by language, sometimes you realise OK like, and of course like some people have different skin colours and you can see like that they come from a different part of the world, right? So uh, but in general, on that side. like I don’t feel really matters like. We’re just people.” (ClCgM6).

On the other hand, informants in the CgCl group expressed the opposite, as for many of them, ethnic identity and integration were very relevant, particularly throughout childhood until young adulthood years. Nevertheless, they have decided that need for closure is a more suitable coping strategy to deal with these topics at this point in their lives: “I left my country when I was 14 and went to Australia, where there are people many parts of the world (…) I explored and even abandoned elements of my identity, such as language and religion then, but now the more I travel and I compare, the more I feel that my identity is winning and nobody can take me away from it” (CgClM9).

Although the nature of this study is not quantitative, the composition of both groups also showed certain interesting demographic trends (see

Table 3), with the HIC group mostly formed by Estonian females, other EU females with multicultural backgrounds, and men from the Global South, while in the LIC group, Estonian females with ethnic minority background and ethnic-Estonian males were more present. Trans-sectional analysis of informants also revealed that all informants in the ClCg group were males from either EU countries outside Estonia or other Global North regions outside the EU. The CgCl group was more diverse but was mainly characterised by featuring informants who were highly aware of their ethnic backgrounds, such as males and females from Estonia who have ethnic minority backgrounds, as well as foreigners from regions where religion plays an important role in society.

Another interesting finding was that some informants (mostly from the LIC group) assigned a more inclusive character to what they referred to as the European (meaning European Union) or Western identities in juxtaposition to other ethnic identities that they or some of their family members have, and which they perceive as more reluctant to include divergent elements, e.g., from appearance to cultural practices and social behaviours. As an example of this, some informants expressed that the European identity implies high levels of cultural awareness: “My partner is a very Western person. Everything has to be politically correct for her. Whereas me, I’m Eastern European, I don’t care about those things and I just say it as it is, and I’m more free” (LICM2). In other cases, informants expressed that this identity implies the inclusion of people who are diverse in appearance and character: “I am Romanian, but I feel more comfortable with European people—just a general mix of Europeans rather than just Romanian. Together, Romanians are great but with Europeans are more colourful and more fruitful if I may say” (LICF3). Finally, for other informants, the mixed character of their children might exclude them from full recognition in their countries of origin, as opposed to their better acceptance in Europe: “My children will never be recognised as one of us back in my country, where things are more fixed than in Europe. It’d be nice if they speak our language, but even if they do, they’ll always have an accent, and their behaviour will be different from ours” (LICF16).

3.1. Acculturation Strategies among Interviewed Parents

Interviewed parents were asked questions related to their feelings of integration in the Estonian society, including the integration of their families. Results show that their identity complexity also seems to have an influence on their attitudes and views in this process.

In this respect, informants from the HIC group expressed more favourable attitudes towards multiculturalism and integration, while in contrast, the LIC group featured views more associated with assimilation, segregation, and separation. Also, for HIC informants, the integration of their families was a process in which they participated more actively: “Either in Estonia or in Germany, I don’t want my children to feel like outsiders. I want them to fully speak both languages) and we also initiate them in my religion, so that they’re like fish in the water and are accepted wherever they go” (HICFF2).

As opposed to this, some LIC respondents expressed that acculturation is a more passive process in which they have relatively little agency. In their view, assimilation will come naturally to their children by growing up in Estonia and attending an Estonian-speaking school. In some cases, informants expressed that their children will be recognised as Estonians by the wider host society as long as they do not have any strongly differentiating markers, e.g., that their children have mostly Northern-European-looking features and fluently speak the Estonian language: “I haven’t thought about what’s (my children’s ethnic identity). It is not important for me to think about it, at least right now. (…) When you look at (them) you don’t make any difference, you know?” (LICEM1).

Among the other two groups, answers by ClCg informants can be categorised under the term melting pot, which implies that they perceive themselves as members of a dominant group—in this case, Global North males—which they feel is mostly welcome everywhere. This group has favourable attitudes towards diversity, particularly if it is not too divergent or oppositional to what is perceived as Western/European (meaning, again, EU) culture and values. Answers also revealed that some informants in this category believe that living and working in cosmopolitan environments where English is the common language facilitates this acculturation outcome. For example, some informants expressed that they have accepted the fact that they live and work in environments where English is the lingua franca adopted by most people, and therefore, learning the local language is not necessary: “I understand the basics of Estonian. However, I’ve given up on it and I’m fine with it. Anyway, I live in an area where English is widely spoken, most of my friends speak English and I speak English at work” (ClCgM11). In other cases, some informants mentioned that their English language and Anglo-Saxon culture are so internationally hegemonic that their children will just absorb it from international environments and the media as they grow up: “Language used to be a barrier for me to connect with people until I joined an international company, where I found a lot of people from my country and others, who speak English and like sports like me (…) it’s more important for my wife that our children feel Estonian than for me that they feel American because Estonia is such a small population and American culture and history, everybody knows it” (ClCgM6).

Acculturation outcomes among CgCl informants presented an interesting characteristic, as some parents in this group manifested that they have significantly modified their ethnic identities, e.g., abandoning language and social connections with their original group to transition to the dominant ethnic-Estonian group. In this respect, their answers revealed that throughout their lifetimes, they have transitioned from separation as members of an ethnic minority to segregation as newly ascribed members of the dominant group. This might also explain their transition from the need for cognition to the need for closure as a coping strategy that influences their current identity complexity: “I grew up in a Russian-speaking environment (…) I went to (an Estonian-speaking) high school in Tallinn and I realised that some this environment that I was in, I didn’t like it. And this environment and these people were like kind of… I understood that I don’t want to deal with this stuff that they are doing, it was not fine for me. So, I kind of left these people out of my life on purpose and just replaced them with my high school mates and everybody was new. Basically, I kind of migrated myself to the other side” (CgClM17).

3.2. Ethnic Identity Representations Ambivalence Based on Identity Complexity

Ethnic identity representations such as dominant, blended (fifty–fifty), compartmentalized, and global citizen were used by informants across all identified groups (see

Table 4). However, these representations have different meanings for them. As an example of this, the fifty–fifty (blended) and global citizen representations, which are recurrent among HIC respondents, have an active character. In this respect, they expressed that they are consciously and constantly working to develop a balanced multi-ethnic identity among their children, with or without the support of their partners. Global citizenship among HIC respondents also includes a vision where their children are actively exposed to people from other cultures and are even prepared to form unions with them and/or live in other countries. In some cases, they feel that their parents raised them for this too: “

I didn’t grow up with this plan of staying where I was. It was almost encouraged by my parents that I would go abroad and follow my path, and I think that how I first went away and study international business and then go to different places without any hesitation to move” (HICF2). Transmitting this appetite and comfort towards international exposure and mobility to their children was a desire that some informants expressed: “

I want my child to understand that there are millions of people and hundreds of nationalities in the world (…) and when she is and that she is a complex child from an international family, perhaps we can move on and live in other countries that would add up to her cultural rainbow bag” (HICF1).

Conversely, for LIC respondents, the term global citizen had more of an “end of the conversation” gist. Dominant representations were recurrent among many informants in this group, who expressed feelings of having very little agency vs. the environment to influence their children’s ethnic identity development. As they are now living in Estonia, their children (who are still young) will be mostly Estonian. Nevertheless, cases appeared where some of their children were born and lived abroad for longer periods of time. In those cases, the identity of those children is represented as mostly foreign: “When we lived in France, there were other French speaking kids at the playground and as I speak the language, I tried to pass it on to my children. But now we’re in Estonia and they’ve picked up the language. So answering your question (how would I describe my children’s ethnic identity?) I think it’s a little bit based on my background but mostly has influence from the environment, my circumstances—something I don’t control” (LICM20).

Dominant and blended representations also appeared among respondents in the ClCg group, who expressed a more active attitude towards developing their children’s sense of multi-ethnic identity. In this case, some informants from this group believed that it was easier to develop the Estonian identity of their kids at an early age first, while their second identity could be developed later in life. The opposite would be much more difficult, due to language barriers and their perception of Estonia, as a society where friendships and social connections are formed during the early years in Estonian-speaking neighbourhoods and schools: “In Estonia, everybody knows everybody and personal connections are very important (…) Besides, we don’t really have an equivalent to that (Estonian cultural traditions) in the UK, so I think it’s very easy to go from Estonia to the UK, because there’s not like a whole. I mean there is some stuff you have to take in, but I think the leap from Estonia to the UK is much smaller than it is to go from the the UK to Estonia. Like if we raised him as a British, or something like that, he would come to Estonia and be totally clueless. So, for me at least, of course, he’s a mix. He has both passports, both citizenships. He’s British and Estonian, but I probably see him as Estonian first” (ClCgM4).

Among the CgCl group, dominant representations meant, in many cases, a sense of hope for the assimilation of their children into the Estonian majority group or at least, as people recognised as having a cosmopolitan identity and Western/EU values: “Raising my children has been a journey, where you have your ideal views but then, reality makes connections. Certainly, I felt that I wanted to speak Russian to my children but then I realised that I’m not really connected to my Russian identity anymore. Maybe that’s why now I support more their identity as Estonians” (CgCl12).

Finally, compartmentalised representations appeared among informants across all groups. In this respect, identity complexity also seems to condition the level of commitment by informants to develop this identity. As an example of this, for HIC informants, compartmentalised meant the wish that their children feel and are recognised as 100% Estonian and 100% foreign independently of the environment where they are. As opposed to this for CgCl and LIC informants, a compartmentalised identity means a stronger separation, as they perceive many oppositional elements in the identities of their children: “Spanish and Estonians are very different. That’s why I’m planning to send my child to Spain when he is in high school, so that he knows how to behave among Spaniards and among Estonians and never feel like an outcast in either place” (CgClF17).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This article has explored and found that identity complexity seems to play a significant role in the perceptions and attitudes towards ethnic identity and acculturation among multicultural family members. By interviewing parents of Estonian–foreign children and analysing their answers, four positions towards these topics have been identified among informants based on their identity complexity. Answers were not straightforward in many cases (as ethnic identity and acculturation can be difficult notions to grasp), and some respondents also expressed opinions that could make them fall into the camp of high and low identity complexity depending on different points of their interview. This is in line with studies that have found cognitive incongruencies among respondents when trying to study their identity complexity (

Brewer and Pierce 2005). What makes the four groups distinctive is that answers by respondents reveal a general inclination towards the cognitive strategies of need for cognition (I am aware and want to know more) or need for closure (I am relatively aware but do not need to know more), which are associated respectively with high and low identity complexity (

Miller et al. 2009;

Webster and Kruglanski 1994) and therefore, can influence their attitudes towards ethnic identity development and acculturation. Furthermore, inconsistencies were expected among the interviewed group, as ultimately, even those respondents who were classed as belonging to the LIC group have decided to form unions and have children with a person born and raised in a different country, and therefore, are aware that their family has more complex characteristics.

Another important consideration is that even if each identified group presents distinctive traits, the purpose of this study is not to present an identity complexity scale but a snapshot of where the interviewed parents were standing, with regards to the discussed topics, during the time when they were interviewed and to show the way in which identity complexity has influenced this process.

In this respect, one of the main findings of this article is that there is more to the concept of identity complexity than the dichotomy of high and low identity complexity among the studied group than that which is presented in other studies (

Brewer 2010;

Brewer and Pierce 2005;

Schmid et al. 2009). To show this, this article has identified two other groups, which have been named not by using titles that denote intermediate degrees, e.g., semi-high/semi-low, but through the use of names that suggest a transition from one cognitive strategy to another (in this case, from need to cognition to need to closure and vice versa) as a way to cope with the challenges of being either a minority group member or having a multicultural family. In summary, identity complexity seems to be a fluid trait, and longitudinal studies might be required to better understand its development throughout the lifetime of different populations.

Most of the interviewed parents belong to the social category that some authors denominate as cosmopolitans—traditionally, middle-class individuals with relatively high levels of education and income and access to international mobility (

Favell 2008;

Rodríguez-García 2006;

Weenink 2008). Results suggest that identity complexity is an element that can help differentiate individuals among this group, which has been traditionally treated as homogeneous (

Gaspar 2010), as it seems to prompt parents’ active or passive attitudes towards their own and their family’s ethnic identity development and acculturation outcomes. Among the transitional groups, results suggest that the move from one cognitive strategy to the other is a reaction towards external elements, which in the case of the ClCg group are the increased interaction with a more international environment and in the case of the CgCl group is their migration from the ethnic minority group to the dominant majority group.

As opposed to other studies that acculturation outcomes and explore identity representations (

Huynh et al. 2011;

Roccas and Brewer 2002), another important finding from this study is that respondents from the identified groups ascribe them with very different meanings. In this sense, the integration outcome is a process where HIC respondents play an active role, while in the case of LIC respondents, it is a passive process that depends mostly on the characteristics of the environment where they live.

Concerning ethnic identity representations, the meaning of the term global citizen is practically oppositional among HIC vs. LIC informants, with the former group actively looking for exposure to other cultures and preparing themselves and their children for a potential life across borders and the latter group using this term mostly as an attempt to avoid talking about ethnic identity or integration. Dominant, blended (fifty–fifty), and compartmentalised representations also meant different things across groups, with LIC informants expressing very low levels of agency to compete vis-à-vis the environment and CgCl informants hoping for the ultimate assimilation and recognition of their children as part of the dominant group. Finally, some informants also used the term European (meaning EU) or Western to refer to a type of identity that they perceive as forward-looking and inclusive of elements that can be considered very divergent. Further studies could be useful to better capture the different meanings that mixed-background populations give to identity representations, considering identity complexity as a relevant aspect in this process.

Finally, as mentioned before, the interviewed sample was composed mainly of highly educated parents with young children who had a very good command of the English language and jobs that allowed them to arrange online interviews at their convenience, even during working hours. This is, at the same time, a limitation and a strength of this study. In the first sense, it would be useful to think of strategies for reaching binational families from other socio-economic segments in future studies to further diversify the sample and compare potential differences. Nevertheless, the characteristics of the sample revealed new diversity traits among a cosmopolitan population, which might be useful to further explore in future studies.