Abstract

Physical activity is essential for women with physical disabilities. This review aims to identify the barriers they face in practicing sport. A systematic review was conducted using the PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science databases in January 2023, with an update in March 2023. The eligibility criteria used for inclusion were as follows. (i) Women with physical disabilities; (ii) women who engage in or want to engage in physical activities and/or sport, both adapted and non-adapted; (iii) identification of women’s barriers to such practice; (iv) research articles; and (v) papers written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals. The exclusion were as follows. (i) Women with illness, injury or transient physical activity difficulties; (ii) mention of rehabilitative physical activity; and (iii) results showing no differentiation in barrier types by gender. This review identified different barriers, grouped into eight types according to the differentiating factor, thus showing that disable people’s participation in physical activity is directly related to some specific barriers which seem to differ according to their gender. Therefore, the success of participation in physical activities depends not only on the user’s concern, but also on an inclusive social environment.

1. Introduction

An estimated 1.3 billion people, or 16% of the world’s population, currently suffer from some form of disability [1]. About 1.5 billion people live with a physical, mental, sensory, or intellectual disability worldwide [2], of which women are the most affected, [3], making up 58.6% of the total. It is well known that regular physical activity is essential for maintaining good health and preventing disease [4,5,6]; the beneficial effects of exercise and physical activity on numerous aspects of health are now well known and generally accepted [7,8,9]. The practice of physical activity improves the physical, mental, and social state of the individual [10]. However, only 40% of women take part in the minimum recommended amount of physical activity [4,11], and in general, people with disabilities are in poorer health than the general population [2,12,13]. People with different disabilities such as cerebral palsy or spinal cord injury often face significant barriers to participating in physical activity [14,15,16], and in particular, women with physical disabilities often face unique and multiple challenges to practicing physical activity, including social, psychological, and physical barriers [17].

There is growing awareness of the importance of physical activity for people with physical disabilities, and as a result, there are several research studies on the benefits of physical activity for people with physical disabilities [18,19,20,21], and some suggestions for the adaptation of activities, e.g., for mothers with physical disabilities [22] or interventions for the assistance of people with a spinal cord injury [23]. Physical/sports activities for people with disabilities contribute to their functional independence, improve their physical condition, performance and physical capacity, favor the prevention and correction of deformities and postural defects, reduce stress, and improve self-confidence, emotional states, relationships with others, enjoyment and interest, among other things [24,25,26]. Within the Spanish population specifically, there is no study on the sporting habits of people with disabilities [27], although there are studies on the low levels of participation in sports practice [28], and on barriers to sport, both for different types of disabilities [14,15,16,29,30] and for people with physical disabilities in particular. However, the involvement of gender differences in these barriers is not appreciated [31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. However, when it comes to participation in physical activity (between women and men with disabilities), [14,16,20] women show poorer levels of participation. Differences gender-wise are found in the perception of barriers to physical activity according to gender [14]. Therefore, it is vitally important to highlight the needs of women with disabilities by identifying the barriers that have been identified in the literature and making this reality visible, in order to encourage participation in physical activity by women with disabilities.

Studies can be found in the literature that examine different types of barriers and their multiple classifications, such as social barriers, including discrimination and stigma; psychological barriers, including low levels of self-esteem and lack of motivation; and physical barriers, such as lack of access to adapted facilities and equipment [38,39,40]. Moreover, there exist intra-personal barriers, such as poor body image or fear of injury [41], and interpersonal barriers, such as lack of support or disapproval from others [12]. It is worth noting the existence of the differentiation in types of barriers according to gender [42]. Ways to overcome these barriers should be explored and the most effective strategies to increase the participation of women with physical disabilities in physical activity should be discussed.

The aim of this research is to raise awareness of the specific barriers faced by women with physical disabilities in relation to physical activity, and to ensure that they are addressed by management to the greatest extent of their responsibilities, in order to promote greater participation in physical activity. For these reasons, this article presents the results of a systematic review of the literature on barriers to physical activity for women with physical disabilities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Searching Strategies

The present research is a systematic review that seeks to identify the perceived barriers to women with physical disabilities who engage in or want to engage in physical activity. The research was conducted according the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [43]. This allowed an adequate structuring of the review, which answers the following question: what are the perceived barriers of women with physical disabilities who engage in or want to engage in physical activity, both adapted and non-adapted?

The following databases were used to conduct a structured search: PUBMED/MEDLINE, Web of Science (WOS) and Scopus. Using these high-quality databases, the search was completed without limitation to any specific year, and results were included up to and including 31 March 2023. Articles were retrieved from electronic databases using the following search strategy (Table 1): Barrier* AND “physical activit*” OR “adapted physical activit*” OR sport* AND disab* AND women OR woman, with these terms appearing in the title or abstract. Keywords were selected based on background reading. Articles considered relevant to this field of activity were obtained using the snowball strategy linked to this equation. In addition, all relevant studies were found by reviewing the titles and abstracts of articles in databases and the results of literature searches. These articles were considered potentially relevant and were analyzed for their compliance with the inclusion criteria for the final analysis. In addition, the reference sections of all articles found were examined, and all titles and abstracts obtained were cross-checked in order to detect possible duplication or lack of actual studies on the topic. Titles and abstracts were also selected for further full-text review. Two different authors searched for previous studies separately (J.O.-I. and N.U.-O.), and possible discrepancies were discussed with a third author (P.L.-G.).

Table 1.

Search strategy.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

No discrimination was made by country, race, or age, in order to obtain the most possible research. Articles published in English or Spanish and only research articles were filtered out.

The eligibility criteria used for inclusion were (i) women with physical disabilities; (ii) women who engage in or want to engage in physical activity and/or sport, both adapted and non-adapted; and (iii) the identification of barriers to women’s physical activity and/or sport. The exclusion criteria applied to the research were the following: (i) women with illnesses (i.e., those not identified as a disability, such as women with cancer), injuries or situations of difficulty for physical activity of a specific or transient duration, such as pregnant women; (ii) women engaging in rehabilitation physical activity, as they have access to physical therapy activities; and (iii) results not showing gender differentiation within the type of perceived barrier.

2.3. Quality Criteria

Two authors assessed quality in terms of the methodology used, along with any risk of bias (J.O.-I. and N.U.O.). Lack of consensus was submitted to third party assessment (P.L-G.), following the protocol for search and selection of studies [44]. All the following points of the protocol were carried out. (1) Whether the selected studies met the eligibility criteria or not was determined; (2) all the papers found were compared with each other to find out whether the studies overlapped or not; and (3) the selection process was then carried out. (A) The search results were combined by identifying the DOI of each article (if not available, one was assigned to each article). (B) All the searches were input in a database, and duplicates removed by DOI for a first screening. (C) For the second screening, studies were sorted by title, and publication data were compared to remove duplicates, taking into account the title, authors, journal, year, and number and/or volume of the study. (D) All the identified full texts were recruited for analysis. (E) The decision to include a paper in the study was made considering the favorable opinion of two researchers (J.O.-I. and N.U.-O.); if there was a difference in opinion, it is a third researcher (A.C.-B.) who decides with a third opinion (following point 4 of the protocol, an established process of inclusion criteria in the case of disagreement, and point 5, the reason for the exclusion of the excluded studies).

2.4. Data Processing

All the selected articles had to identify a study outcome that referred specifically to women. These outcomes were grouped according to the type of outcome, corresponding to a differentiating factors which were as a result of an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) that explained 56.5% of the total variance: personal, physical, psychological, leadership, media support, coaching role, economic, others’ attitudes, social, and cultural/religious support [17]. The barriers identified in each study were categorized and unified according to each grouping factor. In addition to the results, the profile of the subjects and the type of intervention carried out in these studies were added to obtain the results of each study.

3. Results

3.1. Search Process

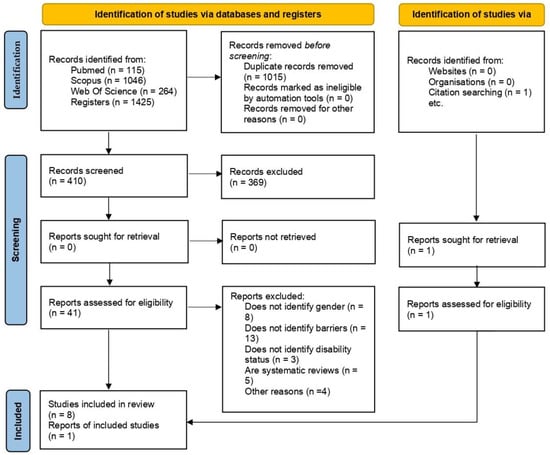

Of the 1425 articles found after searching different databases, only 9 articles were identified that met all the inclusion criteria for the purposes of the systematic review, which are presented in the flowchart [45] (Figure 1). Of these 1425 articles, 1015 were removed as duplicates. Of the remaining 410 articles, 369 were eliminated after examination of titles or abstracts. Of the 41 full-text articles assessed for eligibility, a further 33 papers were discarded because they did not identify gender in the type of barrier (n = 8), did not specify the type of barrier (n = 13), did not specify the type of disability of the subjects (n = 3), were systematic reviews of another topic (n = 5), or were not related to the defined object of study (n = 4). On the other hand, one article was found after the citation search [39]. Thus, the present systematic review included nine studies [39,41,46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection.

3.2. Differentiating Factor and Characteristics of Barriers

The different types of barriers identified as differentiating factors were based on the work of Bakhtiary et al.; the characteristics detected in each of them and the studies in which these barriers are mentioned are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies included in the systematic review: characteristics of barriers and relevant studios.

Table 2 shows that there is no study that confirms that there are barriers according to the differentiating factors of media support and cultural/religious support.

Table 3 shows all the studies found with the most complete data on the study subjects, the intervention methodology used, and the types of barriers identified according to the corresponding factor. The most frequently mentioned factor as a barrier was the psychological factor (n = 7), with a lack of motivation predominating. This was followed by the management (n = 6) of the offers or possibilities to practice sport for women with physical disabilities, and the lack of social support (n = 6), understood as the lack of support both from the immediate environment and from other people in society for access to or the possibility of engaging in physical activity.

Table 3.

Data extraction and synthesis.

4. Discussion

The current review aims to identify the perceived barriers of women with disabilities to engaging in physical activity or sport. We did not find any existing studies with such objectives. Therefore, the main objective has been to identify several types of very complex barriers that cover several aspects through which they can be approached; we propose that knowledge of these will help professionals to guide and favor women with physical disabilities in accessing sports or physical activity, as happens in populations with other physical needs [53]. A total of eight types of barriers (personal, physical, psychological, direction, coach’s role, economic, others’ attitudes, and social support) were identified from nine studies.

This research has yielded many significant insights. First, the results demonstrate that the barriers to physical activity for women with physical disabilities are multiple and complex, and span multiple dimensions. Many women with physical disabilities find it difficult to be physically active [54]; this study has revealed that personal barriers such as age, fatigue, loneliness, lifestyle, or simply being a woman may limit participation in any physical activity. All these factors are responsible for the low participation of women with physical disabilities in sport, since women have been shown to be less likely to participate in sports than men [16].

There is sufficient theoretical evidence on the benefits of sporting activity [55]; in the case of people with disabilities, it contributes to their functional independence, improves their physical condition, performance and physical capacity, favors the prevention and correction of deformities and postural defects, reduces stress, improves self-confidence, emotional state, relationships with others, and enjoyment and interest, among other things [26,56,57,58]. However, a second important finding of this review is that barriers related to physical disability, such as health, mobility, or the degree of dependence on others, also prevent women from practicing sport, thus reducing the possibility of appropriating all the benefits mentioned above.

Another barrier to participation is often linked to psychological factors. Within the psychological variables, motivation is one of the best known, although it is well known that motivation can be influenced by different factors [59] and is considered the most prominent factor in adherence to physical activity [13,60], The same factors were found in this study, wherein women with disabilities experience different situations that lead to a lack of motivation being a barrier to practicing sport [41,46,47,49,50,52]. In addition to motivation, other psychological factors, such as fear [41,50,52], the perception of not being able to engage in physical activity [50], or a negative self-perception [39], form a barrier for women with physical disabilities.

Such women should have opportunities for physical activity in a safe and adapted environment in accordance with their needs, under the Sport Law 2007 [61]; moreover, society as a whole must be committed to making this a reality [62]. However, this study has shown that these people encounter many management barriers, such as poor accessibility or lack of adaptations to sports centers, lack of transport to sports facilities, lack of co-communication between professionals, and poor organizational management. Confined spaces and equipment that does not easily accommodate mobility limitations also prevent them from making full use of exercise equipment and space [16], and the lack of communication between different professionals is also often one of the main barriers [63] that leads to a lack of opportunities [64]. Therefore, we believe that it is necessary to theorize about the structure of sporting institutions, starting with an inclusive atmosphere that can then be implemented into the wider sporting culture and activities, in which all people belonging to the community can be participants, as also pointed out in another study [62].

The role of a coach is essential for the proper performance of physical activities to ensure the safety of the participant and the benefits of physical activity and sport [65]; the important role of trainers is evident [15]. Therefore, health and physical activity professionals should consider individuals’ abilities, needs, limitations, values, personality types and aptitudes in order to customize an adapted program and minimize the effects of possible barriers [53,66]. This study shows that training staff lack training in adapting physical activity or programs to the needs of users. There is a great lack of knowledge about the different sports modalities available for people with disabilities, especially those that are specific (e.g., boccia, slalom and goalball) [67]. Therefore, we believe that personalized attention may be the key to increasing levels of participation in sports, and to keeping programs challenging and attractive for people with physical disabilities. In addition, there should be a variety of offers, so that the user can select a program that best suits his or her needs [64,67].

It is clear that for women with physical disabilities to benefit from sport requires an approach that involves a wider range of programs. However, the economic context of the users must also be considered, as this barrier can have a crucial impact on participation in sport [35]. Taking into account that resources for this group are limited [31], when the financial costs of sporting activities increase, a barrier to participation is formed. In this sense, being a woman can also be an added barrier, as it can be more difficult to obtain sporting sponsors [68]. It is clear that for women with physical disabilities to benefit from sport, an approach that involves a wider range of programs is required. However, the economic context of the users must also be considered, as this barrier can have a crucial impact on participation in sport. Among the benefits of sports practice mentioned above, the improvement of relationships with others is defined by the following [21,26]; however, we should take into account the differentiation between social support in relationships with non-disabled people and in relationships with people with disabilities. Studies have shown an improvement in happiness as a result of perceived social support among people with disabilities [33]; however, this same improvement is not felt as a result of support from people without disabilities [46,47,49,51]. In addition to this, we would have to differentiate between social support from family and from acquaintances and other people. Family support [69] and the support of partners is fundamental, although barriers may exist [41,49,50]; however, the support of society and institutions also has an impact on successful sports practice [14,47,49]. Users are therefore more likely to show reduced adherence to exercise without this support [70,71]. It should also be noted that there are differences in social support according to gender [72]; in one study, it was found that men received more support from family and friends than women [73], just as in this study, wherein a lack of social support can be observed as a barrier to physical activity. Women’s participation in physical activity was shown to be lower than the participation of men with disabilities [14,16,20]; these differences are also significant when it comes to the perception of barriers to physical activity, according to gender [14], between men and women.

It is also worth noting that another barrier identified was social attitudes towards people with disabilities. Negative attitudes may become barriers to the full realization of human potential [38], and because physical disabilities are visible to others, they can lead to stigmatizing social experiences [53,74]. It is therefore necessary to eliminate disability stigma, as people with disabilities who perceive stereotyping to a high degree also perceive a lower quality of life [33,75]. A society that does not recognize and value people with functional diversity loses all the potential they have to offer [76]. Other barriers identified as differentiating factors were culture and media [17], but in this research, they were far less represented.

Limitations

As this is a systematic review, our limitations are related to the studies inserted here. Although the selected sample is composed of a specific population (women with disabilities who want to perform or perform physical activity or sport), it is heterogeneous in terms of age, the type of physical limitation within the physical disability, and the context of the physical activity or sport performed by the women in the studies.

5. Conclusions

This review has enabled the identification of the barriers that women with physical disabilities encounter when performing physical activities. These findings highlight that participation in sports practice does not only depend on the participant. Society must know the barriers that women with physical disabilities face in practicing sports; this review publicizes those barriers in order to improve our best practices. Understanding and raising awareness of these barriers will allow interventions to be adapted to address the barriers, and to provide more targeted support and guidance to women with physical disabilities. As people with physical disabilities themselves have demonstrated and demonstrate every day, we must not forget that they are people with great abilities who want to participate, on equal terms, in physical activity. As active members of the society to which they belong, they have the right to live as independently as possible and with the highest possible quality of life. A society that does not recognize the value of people with functional diversity will lose all the potential they have to offer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.U.-O. and J.O.-I.; Formal analysis: N.U.-O. and J.O.-I.; Investigation: N.U.-O., J.O.-I., A.C.-B. and P.L.-G.; Methodology: N.U.-O., J.O.-I., A.C.-B. and P.L.-G.; Writing and Reviewing; writing—original draft preparation N.U.-O. and J.O.-I.; Project administration: J.O.-I.; Data curation: A.C.-B. and P.L.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- OMS. Discapacidad: Datos y Cifras. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Ginis, K.A.M.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Foster, C.; Lai, B.; McBride, C.B.; Ng, K.; Pratt, M.; Shirazipour, C.H.; Smith, B.; Vásquez, P.M.; et al. Participation of people living with disabilities in physical activity: A global perspective. Lancet 2021, 398, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolkka, T.; Williams, T. Gender and disability sport participation: Setting a sociological research agenda. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 1997, 14, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, N.F.; Rivas, A.D. Actividad física y ejercicio en la mujer. Rev. Colomb. Cardiol. 2018, 25, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Ginis, K.A.; Ma, J.K.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Rimmer, J.H. A systematic review of review articles addressing factors related to physical activity participation among children and adults with physical disabilities. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.J. Benefits and barriers to physical activity for individuals with disabilities: A social-relational model of disability perspective. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 2030–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blauwet, C.A.; Iezzoni, L.I. From the paralympics to public health: Increasing physical activity through legislative and policy initiatives. PMR 2014, 6, S4–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, N.M.; van Ravensberg, C.D.; Hobbelen, J.S.M.; Olde Rikkert, M.G.M.; Staal, J.B.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G. Effects of physical exercise therapy on mobility, physical functioning, physical activity and quality of life in community-dwelling older adults with impaired mobility, physical disability and/or multi-morbidity: A meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2012, 11, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health benefits of physical activity: A systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2017, 32, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozols Rosales, M.A. Editorial—Actividad Física y Discapacidad. MHSalud Rev. en Ciencias del Mov. Hum. y Salud 2007, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kızar, O.; Demir, G.T.; Genç, H. Examination of the Effect of National and Amateur Disabled Athletes’ Disabilty Types on Sports Participation Motivation. Eur. J. Phys. Educ. Sport Sci. 2021, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Úbeda-Colomer, J.; Monforte, J.; Devís-Devís, J. Physical activity of university students with disabilities: Accomplishment of recommendations and differences by age, sex, disability and weight status. Public Health 2019, 166, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzen, M.; Brurok, B.; Roeleveld, K.; Hoff, M.; Jahnsen, R.; Wouda, M.F.; Baumgart, J.K. Changes in physical activity and basic psychological needs related to mental health among people with physical disability during the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 101126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dėdelė, A.; Chebotarova, Y.; Miškinytė, A. Motivations and barriers towards optimal physical activity level: A community-based assessment of 28 EU countries. Prev. Med. 2022, 164, 107336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J.J.; Spencer, N.L.I. “A Really Strong Bond”: Coaches in Women Athletes’ Experiences of Inclusion in Parasport. Int. Sport Coach. J. 2021, 8, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, D.E.; Yoshida, K.; Renwick, R.; Bailey, C. Negotiating participation: How women living with disabilities address barriers to exercise. Health Care Women Int. 2009, 30, 743–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhtiary, F.; Noorbakhsh, M.; Noorbakhsh, P.; Sepasi, H. Development and Validation of a Tool for Assessing Barriers to Participation in Team Sports for Women with Physical-Mobility Disabilities. Ann. Appl. Sport Sci. 2020, 8, e809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sañudo Corrales, B. Actividad físico—Deportiva para personas con discapacidad física. In Actividad Física en Poblaciones Especiales: Salud y Calidad de Vida; Wanceulen: Sevilla, Spain, 2012; pp. 97–132. ISBN 978-84-9993-260-6. [Google Scholar]

- Charron, S.; McKay, K.A.; Tremlett, H. Physical activity and disability outcomes in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review (2011–2016). Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2018, 20, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullagh, R.; Fitzgerald, P.; Murphy, R.P.M.; Cooke, G. Long-term benefits of exercising on quality of life and fatigue in multiple sclerosis patients with mild disability: A pilot study. Clin. Rehabil. 2008, 22, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, R.J. Benefits of sport and physical activity for the disabled: Implications for the individual and for society. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1991, 23, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.O.; Becker, H.; Andrews, E.E.; Phillips, C.S. Adapting a health behavioral change and psychosocial toolkit to the context of physical disabilities: Lessons learned from disabled women with young children. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 100977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, L.S.; Lima, M.B.; Salvador, E.P. Interventions for promoting physical activity among individuals with spinal cord injury: A systematic review. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbour, K.P.; Latimer, A.E.; Ginis KA, M.; Jung, M.E. Moving beyond the stigma: The impression formation benefits of exercise for individuals with a physical disability. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2007, 24, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asonitou, K.; Mpampoulis, T.; Irakleous-Paleologou, H.; Koutsouki, D. Effects of an adapted physical activity program on physical fitness of adults with intellectual disabilities. Adv. Phys. Educ. 2018, 8, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, M.; Duque, R. Beneficios de la práctica de actividad física deportiva en personas con discapacidad física. Año 2022, 20, 152–172. [Google Scholar]

- Perez Tejero, J.; Ocete Calvo, C. Personas con discapacidad y práctica deportiva en España. In Libro Blanco del Deporte de Personas con Discapacidad en España; Cermi. Ediciones Cinca: Madrid, Spain, 2019; ISBN 978-84-16668-69-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Muñoz, A.; Sanz de Gabiña, L.; Figueroa de la Paz, A. Estudio Sobre Los Hábitos Deportivos en Las Personas con Discapacidad en la Provincia de Guipúzcoa; Gobierno de España, Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad: Gipúzcoa, Spain, 2007; ISBN 9788527729833. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandra, D.; Rojas, C.; Valentina, J.; Castrillon, D.; Cabrera, V.G.; Marcela, L.; González, E.; Marcela, P.; Garzón, M.; Muñoz-hinrichsen, F.; et al. Estado del arte de la investigación en discapacidad y actividad física en Sudamérica. Una Revisión Narrativa. Retos 2023, 2041, 945–968. [Google Scholar]

- Rincón, F.; Aydé, C.; Giraldo, R.; Alexis, F. Percepción de beneficios, barreras y nivel de actividad física de estudiantes universitarios. Investig. Andin. 2015, 17, 1391–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Braza, D.W.; Iverson, M.; Lee, K.; Hennessy, C.; Nelson, D. Promoting physical activity by creating awareness of adaptive sports and recreation opportunities: An academic–community partnership perspective. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2018, 12, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffart, L.M.; Westendorp, T.; Van Den Berg-Emons, R.J.; Stam, H.J.; Roebroeck, M.E. Perceived barriers to and facilitators of physical activity in young adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities. J. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 41, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Cho, J.; Fuller, D.K.; Kang, M. Correlates of physical activity among people with disabilities in South Korea: A multilevel modeling approach. J. Phys. Act. Health 2015, 12, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulligan, H.; Miyahara, M.; Nichols-Dunsmuir, A. Multiple perspectives on accessibility to physical activity for people with long-term mobility impairment. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2017, 19, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scelza, W.M.; Kalpakjian, C.Z.; Zemper, E.D.; Tate, D.G. Perceived barriers to exercise in people with spinal cord injury. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 84, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.; Papathomas, A.; Martin Ginis, K.A.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. Understanding physical activity in spinal cord injury rehabilitation: Translating and communicating research through stories. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 2046–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Úbeda-Colomer, J.; Monforte, J.; Granell, J.C.; Goig, R.L.; Cabrera, M.Á.T.; Devis-Devis, J. Reasons for sport practice and drop-out in university students with disabilities: Influence of age and disability grade. Cult. Cienc. y Deport. 2018, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricia, J.; Miranda, A.; Yulieth, L.; Urquijo, G. Barreras contextuales para la participación de las personas con discapacidad física. Salud UIS 2013, 45, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, E.V.; Smith, B.; Papathomas, A. Disability and the gym: Experiences, barriers and facilitators of gym use for individuals with physical disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 1950–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Han, A.; Nguyen, M.C. The contribution of physical and social activity participation to social support and happiness among people with physical disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 100974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.M.; Wozencroft, A.; Bedini, L.A. Adolescent girls’ involvement in disability sport: A comparison of social support mechanisms. J. Leis. Res. 2008, 40, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascondo, J.; Martín-López, A.; Iturricastillo, A.; Granados, C.; Garate, I.; Romaratezabala, E.; Martínez-Aldama, I.; Romero, S.; Yanci, J. Analysis of the Barriers and Motives for Practicing Physical Activity and Sport for People with a Disability: Differences According to Gender and Type of Disability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McGuinness, L.; McDonald, S.; Stewart, L.A.; Thomas, J.; et al. Pravila PRISMA 2020. Med. Flum. 2021, 57, 444–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, C.; Glanville, J.; Briscoe, S.; Littlewood, A.; Marshall, C.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; Noel-Storr, A.; Rader, T.; Shokraneh, F.; Thomas, J.; et al. Searching for and Selecting Studies; Wiley Online Library: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugonski, D.; Joyce, R.J.; Motl, R.W. Meanings, motivations, and strategies for engaging in physical activity among women with multiple sclerosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 2148–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K.A.; Bedini, L.A. “I have a soul that dances like tina turner, but my body can’t”: Physical activity and women with mobility impairments. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1995, 66, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odette, F.; Israel, P.; Li, A.; Ullman, D.; Colontonio, A.; Maclean, H.; Locker, D. Barriers to Wellness Activities for Canadian Women with Physical Disabilities. Health Care Women Int. 2003, 24, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Cárdenas, J.P.; Perdomo Vargas, I.R.; Garzón Patrana, G.; Vargas Reyes, J.D. Percepción de factores que inciden en la participación y competencia de mujeres atletas en Para Powerlifting. Educ. Física y Cienc. 2021, 23, e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Fekete, C.; Cieza, A.; Geyh, S.; Meyer, T. Participation in physical activity in persons with spinal cord injury: A comprehensive perspective and insights into gender differences. Disabil. Health J. 2013, 6, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.V.; Smith, B.; Papathomas, A. Collective stories of exercise: Making sense of gym experiences with disabled peers. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2017, 34, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimmer, J.H.; Rubin, S.S.; Braddock, D. Barriers to exercise in African American women with physical disabilities. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000, 81, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, E.; Coelho, J.; Rogado, P.; Correia, R.; Castro, C.; Fernandes, J.B. Barriers to Gait Training among Stroke Survivors: An Integrative Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2022, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacEachern, S.; Forkert, N.D.; Lemay, J.F.; Dewey, D. Physical Activity Participation and Barriers for Children and Adolescents with Disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2022, 69, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa-Granados, S.; Urrea-Cuellar, A. Influencia del deporte y la actividad física en el estado de salud físico y mental. Katharsis 2018, 25, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, R.M. Physical activity and quality of life in the elderly. A narrative review. Rev. Habanera Cienc. Med. 2018, 17, 813–825. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, E.V.V.; Cano, A.G.B.; Chasipanta, W.G.A.; Navarrete, L.R.P.; Ipiales, E.N.P.; Frómeta, E.R. Programa de actividades físico-recreativas para desarrollar habilidades motrices en personas con discapacidad intelectual. Rev. Cuba. Investig. Biomed. 2017, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco-Benítez, C.A.; Reyes-Oyola, F.A. Niveles de actividad física, calidad de vida relacionada con la salud, autoconcepto físico e índice de masa corporal: Un estudio en escolares colombianos. Biomédica 2018, 38, 451–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwood, C.G.; Keegan, R.J.; Smith, J.M.J.; Raine, A.S. A systematic review of the intrapersonal correlates of motivational climate perceptions in sport and physical activity. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 18, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monforte, J.; Úbeda-Colomer, J.; Pans, M.; Pérez-Samaniego, V.; Devís-Devís, J. Environmental barriers and facilitators to physical activity among university students with physical disability-a qualitative study in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de España. REAL DECRETO 1363/2007, de 24 de Octubre, por el que se Establece la Ordenación General de las Enseñanzas Deportivas de Régimen Especial. 2007; pp. 45945–45960. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2007/10/24/1363 (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- López González, S.P. El derecho humano a la educación. Derecho Glob. Estud. Sobre Derecho y Justicia 2016, 2, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginis, K.A.M.; West, C.R. From guidelines to practice: Development and implementation of disability-specific physical activity guidelines. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 3432–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.; Roberts, R.; Bowman, G.; Crettenden, A. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity participation for children with physical disability: Comparing and contrasting the views of children, young people, and their clinicians. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos Izquierdo, A. Los profesionales de la actividad física y el deporte como elemento de garantía y calidad de servicios. Cult. Cienc. y Deport. 2007, 3, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.B.; Fernandes, S.B.; Almeida, A.S.; Vareta, D.A.; Miller, C.A. Older adults’ perceived barriers to participation in a falls prevention strategy. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, R. Propuesta de intervención para la mejora de actitudes hacia personas con discapacidad a través de actividades deportivas y recreativas. Lect. Educ. Física y Deport. 2003, 59, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Dashper, K. “It’s a Form of Freedom”: The experiences of people with disabilities within equestrian sport. Ann. Leis. Res. 2010, 13, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichsen, F.I.M.; Aros, A.F.M.; Miranda, F.H. Transcultural translation and adaptation of the questionnaire for children «Barriers and facilitators of sports in children with physical disabilities (BaFSCH)» for use into Spanish in Chile. Retos 2021, 44, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, B.; González, A.; Pasten, E.; Concha-Cisternas, Y. Sports family climate and the level of physical activity in adolescents. Retos 2022, 45, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero Solís, M.; Tapia Serrano, M.Á.; Cerro Herrero, D.; Sánchez Miguel, P.A. Importancia del rol familiar en la práctica de actividad física e IMC de escolares adolescentes. Sport. Sci. J. Sch. Sport. Phys. Educ. Psychomot. 2019, 5, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Martín, D.; Ruiz-Tendero, G.; Fernández-García, E. Relación entre la práctica de actividad física y el apoyo social percibido de los adolescentes de la provincia de Soria. Sport TK-Revista Euroam. Ciencias del Deport. 2021, 10, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D.R.; Sylva, K.; Morgan, P.J. Factors associated with physical activity in a sample of British secondary school students. Aust. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 7, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- López Alvarado, M.C.; De Andrés, S.; Gonzalez Martín, R. Discapacidad: Estigma y concienciación. Comun. e Cid. Rev. Int. Xorn. Soc. 2007, 1, 202–223. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, L.F.; Martín, N.; Molero, F. Stigma consciousness and quality of life in persons with physical and sensory disability. Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 28, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iáñez, A. Cuerpo y modernidad. El procesos de estigmatización en las personas con diversidad funcional física. Trib. Abierta 2009, 2009, 105–122. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).