Resilient Urban Communities: A Case Study of the Cvjetno Housing Estate, a Modern Period Predecessor in Urban Planning in Croatia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Concept of Resilient Communities

1.2. Natural Hazards as Context for Establishing Resilient Communities

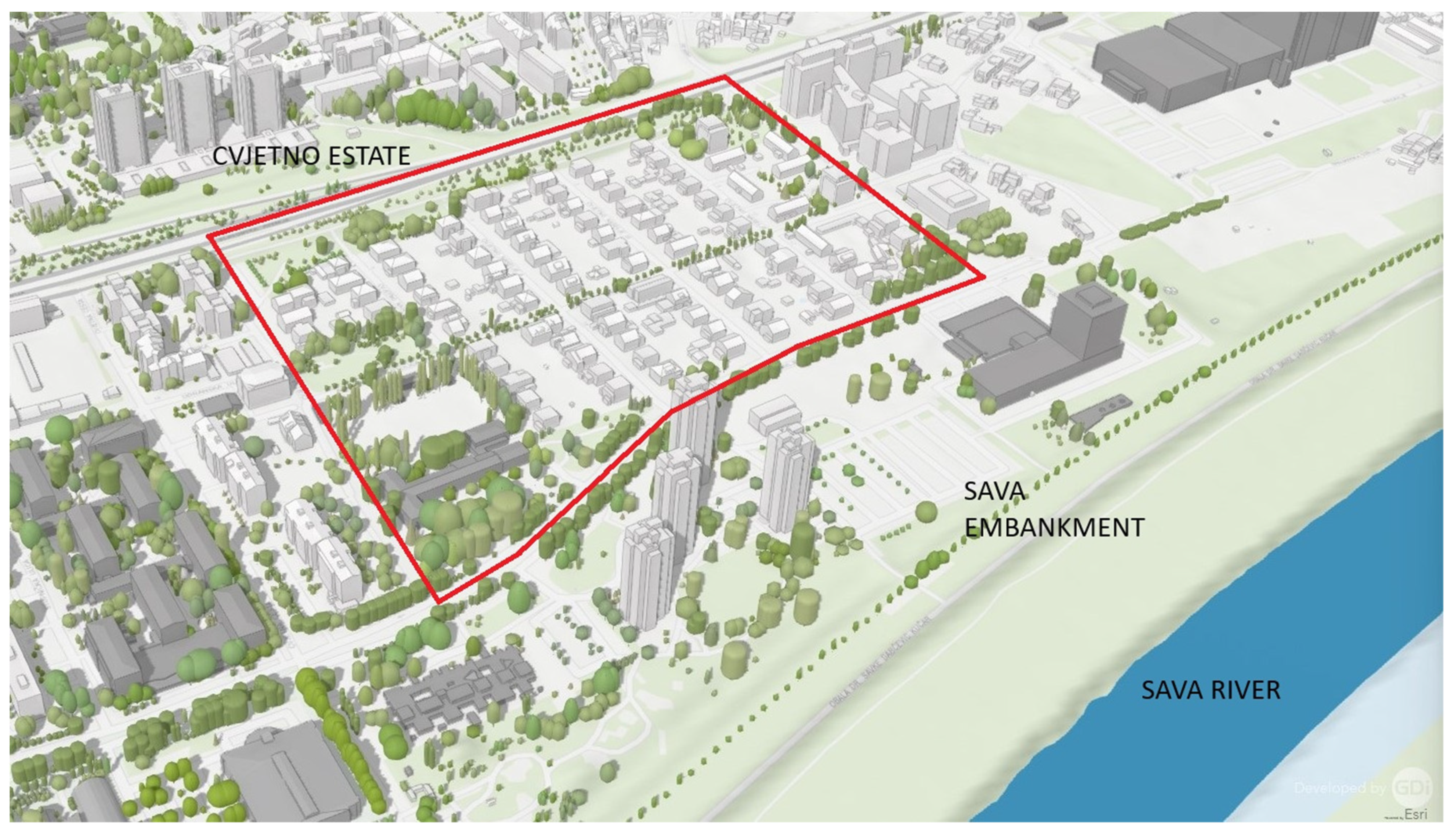

1.3. The Urbanization of Trnje and the Origins of the Cvjetno Housing Estate

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Planning for Community Resilience

3.2. Cvjetno Housing Estate as a Resilient Community

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thomsen, M.R.; Tamke, M. Preface. In Design for Resilient Communities—Proceedings of the UIA World Congress of Architects Copenhagen 2023; Rubbo, A., Du, J., Ramsgaard Thomsen, M., Tamke, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. xi–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo, A.; Chieffallo, L.; Virgilio, S. Re-generate resilience to deal with climate change. A data-driven pathway for a liveable, efficient and safe city. TeMA—J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. Spec. Issue 2024, 1, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, D. Designing Community. Charrettes, Masterplans and Form-Based Codes; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kulturno—povijesna cjelina Cvjetno naselje/Cultural and Historical Complex Cvjetno Naselje. 2004. Available online: https://registar.kulturnadobra.hr/#/details/Z-1543 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Ministartstvo Kulture. Izvod iz Registra Kulturnih Dobara Republike Hrvatske br. 4/2002—Lista Zaštićenih kulturnih dobara/Extract from the Register of Cultural Properties of the Republic of Croatia No. 4/2002—List of Protected Cultural Properties. 2004. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2004_08_111_2128.html (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Premerl, T. O prostorno-urbanističkom razvoju Zagreba/On the spatial and urban development of Zagreb. Arhitektura 1970, XXIV, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Premerl, T. CIAM i naša međuratna arhitektura/CIAM and our interwar architecture. Arhitektura 1984, XXXVII–XXXVIII, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Premerl, T. Hrvatska Moderna Arhitektura Između Dva Rata/Croatian Modern Architecture between the Two Wars; Nakladni zavod Matice Hrvatske: Zagreb, Croatia, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mahečić, D.R. Socijalno stanovanje međuratnog Zagreba/Social housing in interwar Zagreb. Rad. Inst. Povij. Umjet. 1993, 17, 141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Mahečić, D.R. Šutljiva zagrebačka arhitektura/Silent Zagreb architecture. Covjek. I Prost. 1994, XXXXI, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mahečić, D.R. Socijalno Stanovanje Međuratnog Zagreba/Social Housing in Interwar Zagreb; Horetzky: Zagreb, Croatia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mahečić, D.R. Činovničko stambeno naselje—Cvjetno naselje/Residential district for clerks—Cvjetno district. In Moderna arhitektura u Hrvatskoj 1930-ih/Modern architecture in Croatia in the 1930s; Radović Mahečić, D., Ed.; Institut za Povijest Umjetnosti & Školska knjiga: Zagreb, Croatia, 2007; pp. 441–446. [Google Scholar]

- Mlinar, I.; Trošić, M. Parkovi zagrebačkih stambenih naselja izgrađenih između dva svjetska rata/Parks of the Housing Developments in Zagreb Built between the two World Wars. Prostor 2004, 12, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, E.; Rupnik, I. Project Zagreb: Transition as Condition, Strategy, Practice; Actar D: Barcelonam, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maroević, I. Cvjetno naselje—Put prema nestanku/Cvjetno eatate—the road to extinction. In O Zagrebu Usput i s Razlogom. Izbor Tekstova o Zagrebačkoj Arhitekturi i Urbanizmu (1970–2005); Institut za Povijest Umjetnosti: Zagreb, Croatia, 2007; pp. 355–357. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanković, V. Arhitekt Vladimir Antolić—Zagrebački urbanistički opus između dva svjetska rata/Architect Vladimir Antolić and his Urban Plans of Interwar Zagreb. Prost. Znan. Časopis Za Arhit. I Urban 2009, 17, 268–282. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, A.; Twigg, J.; Burayidi, M.A.; Wamsler, C. Urban resilience: State of the art and future prospects. In The Routledge Handbook of Urban Resilience; Burayidi, M.A., Allen, A., Twigg, J., Wamsler, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 476–487. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Yu, Y.; Yang, S.; Lv, Y.; Sarker, M.N.I. Urban Resilience for Urban Sustainability: Concepts, Dimensions, and Perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN HABITAT, Trends in Urban Resilience. 2017. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/Trends_in_Urban_Resilience_2017_smallest.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiKov-v-cGHAxXxxAIHHaZML6cQFnoECBAQAw&usg=AOvVaw2xTlxhDHqaDWWNPAquBt4u (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Braì, E.; Mangialardi, G.; Scarpelli, D. Circular living. A resilient housing proposal. Tema. J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2022, 15, 447–469. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, A.; Currà, E. The Role of Urban Built Heritage in Qualify and Quantify Resilience. Specific Issues in Mediterranean City. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 18, 181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Normandin, J.-M.; Therrien, M.-C.; Pelling, M.; Shona, P. The Definition of Urban Resilience: A Transformation Path Towards Collaborative Urban Risk Governance. In Urban Resilience for Risk and Adaptation Governance. Resilient Cities; Brunetta, G., Caldarice, O., Tollin, N., Rosas-Casals, M., Jordi, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Moreau, M.; Ménascé, D. Urban resilience: Introducing this issue and summarizing the discussions. Field Actions Sci. Rep. Spec. Issues 2018, 18, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Barchetta, L.; Petrucci, E.; Xavier, V.; Bento, R. A Simplified Framework for Historic Cities to Define Strategies Aimed at Implementing Resilience Skills: The Case of Lisbon Downtown. Buildings 2023, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR), Living with Risk. A Global Review of Disaster Reduction Initiatives; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters, Proceedings of the World Conference on Disaster Reduction, Kobe, Japan, 18–22 January 2005; A/CONF.206/6; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNISDR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://www.undrr.org/media/16176 (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- D’Amico, A.; Currà, E. Resilienza urbana dei centri storici italiani. Strategie di pianificazione preventive. Techne 2018, 15, 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Zulfahmi, A.; Chu, H.-J.; Kuo, Y.-L.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Wong, H.-K.; Al, Z. Muhammad. Residential Flood Loss Assessment and Risk Mapping from High-Resolution Simulation. Water 2019, 11, 751. [Google Scholar]

- LaGro, J.J. Urban open space systems: Multifunctional infrastructure. In The Routledge Handbook of Urban Resilience; Burayidi, M.A., Allen, A., Twigg, J., Wamsler, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Lank, P.; Gnatz, D.M.; Wilhelmi, O.; Hayden, M. Urban Sustainability and Resilience: From Theory to Practice. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. Climate justicescape and implications for urban resilience in American cities. In The Routledge Handbook of Urban Resilience; Burayidi, M.A., Allen, A., Twigg, J., Wamsler, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlicke, C.; Kabisch, S.; Rink, D. Urban resilience and urban sustainability. In The Routledge Handbook of Urban Resilience; Burayidi, M.A., Allen, A., Twigg, J., Wamsler, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockefeller Foundation and Arup, City Resilience Index. 2015. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.arup.com/globalassets/downloads/insights/city-resilience-index.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwipi8L6-sGHAxXxFBAIHSPdMkEQFnoECBAQAQ&usg=AOvVaw12sHf98BWdBOG7zz9RtbB2 (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Cavaye, J.; Ross, H. Community resilience and community development: What mutual opportunities arise from interactions between the two concepts? Community Dev. 2019, 50, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magis, R. Community Resilience: An Indicator of Social Sustainability. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliou, M.; van de Lindt, J.W.; McAllister, T.P.; Ellingwood, B.R.; Dillard, M.; Cutler, H. State of the research in community resilience: Progress and challenges. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2018, 5, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.F.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPREAD 2050, Scenarios for Sustainable Lifestyles 2050: From Global Champions to Local Loops. 2012. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.cscp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Scenarios-for-Sustainanle-Lifestyles_2050.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiWiNOg-8GHAxXxQVUIHVKvAJkQFnoECA8QAQ&usg=AOvVaw2JE2NYQU_RBnkvUjWork09 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Grad Zagreb. Procjena rizika od velikih nesreća za područje Grada Zagreba/Assessment of the Risk of Major Accidents for the Area of the City of Zagreb; Gradska Skupština Grada Zagreba: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anić, T. Društvena povijest Trnja u prvoj polovini dvadesetog stoljeća. In Trnje—Prostor i Ljudi; Strukić, K., Ed.; Muzej Grada Zagreba: Zagreb, Croatia, 2020; pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Marušić, J. Stručni prikaz: 55 godina od katastrofalne poplave Zagreba krajem listopada 1964./Expert report: 55 years since the catastrophic flood of Zagreb at the end of October 1964. Hrvat. Vode 2019, 27, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Marušić, J. Iz povijesti vodnog gospodarstva: Studija regulacije i uređenja rijeke Save/From the history of water management: A study of the regulation and organization of the Sava River. Hrvat. Vode 2022, 30, 255–259. [Google Scholar]

- Šegvić, N.Š.; Šute, I. “Pola grada pod vodom”. Zbrinjavanje stradalih od poplave u Zagrebu 1964. godine, te plan za daljnju obnovu/»Half the city under water.« Taking care of the victims of the floods in Zagreb in 1964 and a plan for further reconstruction. Ekon. I Ekohist. 2021, 17, 66–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bonevska, T.; Grlić, M.; Horvat, M.; Miholić, L.; Martinić, I. Zagrebački potres 2020. Geogr. Horiz. 2020, 66, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Vukić, F.; Vukić, J. Potres i identitet grada: živimo li kognitivnu apokalipsu/The earthquake and the identity of the city: Are we living a cognitive apocalypse. In Obnova povijesnog središta Zagreba nakon potresa, pristup, problemi i perspektive, Zbornik priopćenja sa znanstveno stručne konferencije; Hrvatska Akademija Znanosti i Umjetnosti: Zagreb, Croatia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zagreb, G. Plan djelovanja civilne zaštite Grada Zagreba/City of Zagreb Civil Protection Action Plan. 2019. Available online: https://zagreb.hr/plan-djelovanja-civilne-zastite-grada-zagreba/148812 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- ARIA Damage Proxy Map. 2020. Available online: https://maps.disasters.nasa.gov/arcgis/home/webmap/viewer.html?layers=db20d487cee24810bd7b8cc96ccbcf3b (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- DHMZ. Climate Assessments. 2014–2023. Available online: https://meteo.hr/klima_e.php?section=klima_pracenje¶m=ocjena&MjesecSezona=godina&Godina=2023 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- State Geodetic Administration. Geoportal. 2024. Available online: https://geoportal.dgu.hr/ (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Doklestić, B. Grad na Savi/City on the Sava. In Zagrebačke Urbanističke Promenade/Zagreb City Promenade; Dominović d.o.o.: Zagreb, Croatia, 2010; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Jukić, T.; Mlinar, I.; Smokvina, M. Zagreb—Stanovanje u Gradu i Stambena Naselja/Zagreb—Housing in the City and Residential Areas, Zagreb: Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Arhitektonski Fakultet, Zavod za Urbanizam, Prostorno Planiranje i Pejsažnu Arhitekturu; Gradski Ured za Strategijsko Planiranje i Razvoj Grada: Grad Zagreb, Croatia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mlinar, I. Urbanizacija i arhitektura Trnja/Urbanization and architecture of Trnje. In Trnje—Prostor i Ljudi/Trnje—Space and People; Strukić, K., Ed.; Muzej Grada Zagreba: Zagreb, Croatia, 2020; pp. 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mlinar, I. Urbanističko-arhitektonski leksikon Trnja/Urban-architectural lexicon of Trnje. In Trnje—Prostor i Ljudi/Trnje—Space and People; Strukić, K., Ed.; Muzej Grada Zagreba: Zagreb, Croatia, 2020; pp. 133–158. [Google Scholar]

- Strukić, K. Kvartovske priče iz Trnja/Neighborhood stories from Trnje. In Trnje—Prostor i Ljudi/Trnje—Space and People; Strukić, K., Ed.; Muzej Grada Zagreba: Zagreb, Croatia, 2020; pp. 11–41. [Google Scholar]

- Podnar, I. Identity Reevaluation of a Place on the Example of Cvjetno Naselje in Zagreb. Defin. Archit. Space—Avant-Garde Archit. 2022, 4, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

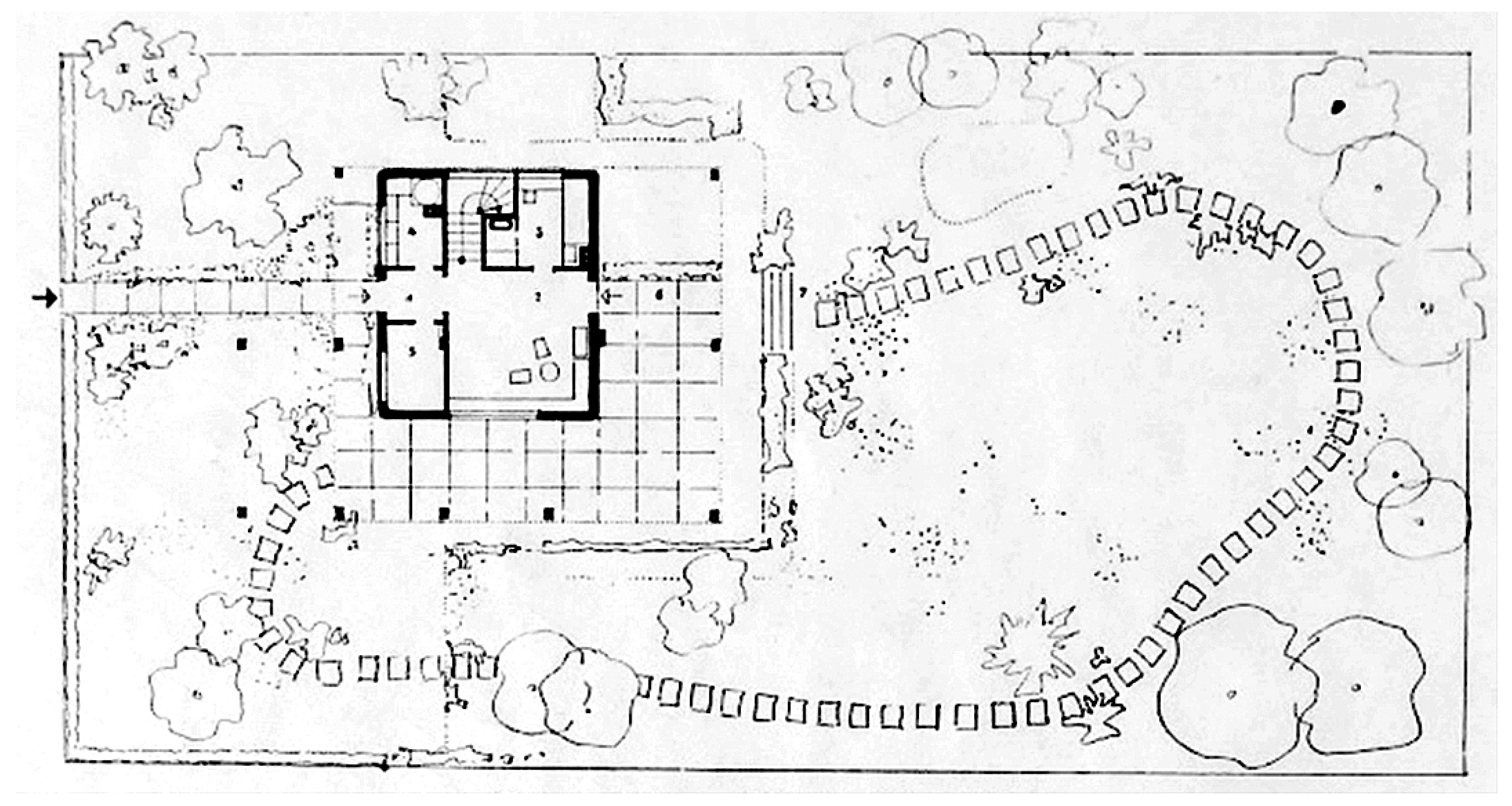

- Antolić, V. Cvjetno naselje u Zagrebu/Cvjetno estate in Zagreb. Inženjer 1940, 3–4, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Šririć, E. Vlado Antolić. Arhitektura 1998, LI, 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- Klarin, T.B. Radna grupa Zagreb—Osnutak i javno djelovanje/Zagreb Group—Foundation and Public Activities in Croatian Cultural Context. Prostor 2005, 13, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zagreb, G.; Gradski Ured za Gospodarstvo, Ekološku Održivost i Strategijsko Planiranje/City of Zagreb, City Office for Economy, Environmental Sustainability, and Strategic Planning. ZG3D: 3D Model Grada Zagreba/ZG3D: 3D model of Zagreb. Available online: https://zagreb.gdi.net/zg3d/ (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Mumford, E. CIAM and Its Outcomes. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Shen, J.-K.; Xiang, W.-N.; Wang, J.-Q. Identifying characteristics of resilient urban communities through a case study method. J. Urban Manag. 2018, 7, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q. Policies and practices on urban resilience in China. In The Routledge Handbook of Urban Resilience; Burayidi, M.A., Allen, A., Twigg, J., Wamsler, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 130–142. [Google Scholar]

- Državni arhiv u Zagrebu/Sate Archive in Zagreb, HR-DAZG-1122-620/1. Available online: http://zagreb.arhiv.hr/en/hr/hda/fs-ovi/o-hda.htm (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Buljan, I.H. Prilog za biografiju arhitekta Zvonimira Kavurića (1901–1944.)/A Contribution to the Biography of Architect Zvoni mir Kavurić (1901–1944). Rad. Inst. za Povij. Umjet. 2006, 30, 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Khale, D. Architect Zlatko Neumann—Works after the Second World War (1945–1963). Prostor 2016, 24, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, D.; Martins, H.; Marta-Almeida, M.; Rocha, A.; Borrego, C. Urban resilience to future urban heat waves under a climate change scenario: A case study for Porto urban area (Portugal). Urban Clim. 2017, 19, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rędzińska, K.; Piotrkowska, M. Urban Planning and Design for Building Neighborhood Resilience to Climate Change. Land 2020, 9, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamukcu-Albers, P.; Ugolini, F.; La Rosa, D.; Grădinaru, S.R.; Azevedo, J.C.; Wu, J. Building green infrastructure to enhance urban resilience to climate change and pandemics. Landsc. Ecol 2021, 3, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Državni arhiv u Zagrebu/State Archive in Zagreb, HR-DAZG-1122-624/7. Available online: https://portal.ehri-project.eu/institutions/hr-004567 (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Epstein-Pliouchtch, M.; Abramovich, T. From “White City” to “Bauhaus City”—Tel Aviv’s urban and architectural resilience. Docomomo J. 2019, 61, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Goal | Indicator | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health and wellbeing | Minimal human vulnerability | Safe and affordable housing | Robust construction and protective infrastructure |

| Health and wellbeing | Diverse livelihood and employment | Supportive financing mechanisms | Cost-efficient building and affordable loan repayment |

| Economy and society | Collective identity and community support | Cohesive community | Integrated community |

| Infrastructure and ecosystems | Reduces exposure to fragility | Protective infrastructure | Robust protective infrastructure and physical environment |

| Leadership and strategy | Effective leadership and management | Appropriate government decision-making | Support in affordable housing |

| Integrated development planning | Appropriate land use and zoning | Rational and appropriate use of space |

| Layer | Performance Dimension | Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental layer | Spatial pattern | Multi-functionality | Parcels with multi-functional spaces for living and food growing Rational planning |

| Flexibility | Flexible and adaptable living spaces | ||

| Environmental components | Interactivity | Public spaces support community interaction of different age groups | |

| Diversity | Different types of equipment in public spaces offer diverse activities | ||

| Core layer | Public service | Intelligence | - |

| Humanity | Planned public spaces within walking distance | ||

| Top layer | Management system | Prediction | Houses planned and constructed to adapt to flooding and absorb the effect of earthquakes |

| Collaboration | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kostešić, I. Resilient Urban Communities: A Case Study of the Cvjetno Housing Estate, a Modern Period Predecessor in Urban Planning in Croatia. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8030102

Kostešić I. Resilient Urban Communities: A Case Study of the Cvjetno Housing Estate, a Modern Period Predecessor in Urban Planning in Croatia. Urban Science. 2024; 8(3):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8030102

Chicago/Turabian StyleKostešić, Iva. 2024. "Resilient Urban Communities: A Case Study of the Cvjetno Housing Estate, a Modern Period Predecessor in Urban Planning in Croatia" Urban Science 8, no. 3: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8030102