Abstract

The present research aims to propose resilient urban-design strategies to mitigate the risk of landslides in Huaraz. This study addresses the growing challenge of climate change and its influence on the occurrence of avalanches in Huaraz, Peru. The methodology employed included a literature review, site analysis using digital tools, and the formulation of resilient urban-design strategies. As a result, a Master Plan for Urban Resilience is proposed, using a detailed literature review, climate studies, and topographic evaluation to design urban strategies that enhance the city’s sustainability and safety. The proposed interventions, including channel expansion, installation of gabions and containment meshes, reforestation, and strategic relocation of housing, demonstrate significant potential to reduce vulnerability to avalanches. This multidisciplinary approach underscores the necessity of integrating urban adaptations in response to extreme climate variations in the Andean regions. The proposal stands out for its innovation and resilience, precisely aligning with the unique characteristics of Huaraz. The comprehensive strategy not only focuses on urban regeneration and risk prevention but also aims to significantly improve the community’s quality of life.

1. Introduction

Currently, climate change has become a critical challenge in a constantly transforming world, where cities face increasingly pressing issues related to climate change and growing exposure to natural risks [1]. In the Latin American context, climate change has taken a leading role in government agendas over the last two decades. This diverse and vast region has witnessed notable climate transformations that have had a significant impact on the lives of its inhabitants and the configuration of its urban areas [2].

Over the past two decades, climate change has emerged as a matter of paramount importance on the governmental agendas of Latin America. This concern is grounded in concrete data that demonstrate the growing impact of this phenomenon on the region. For instance, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, the average temperature in Latin America has increased by approximately 0.8 °C since the onset of the Industrial Revolution, surpassing the global average of 0.6 °C [3,4,5]. This thermal increase carries significant consequences for the region, exacerbating the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events such as hurricanes, floods, and droughts.

In the Caribbean, there has been an observed uptick in hurricane activity, with an average of 150 hurricanes per season in the last decade, contrasting with the 100 hurricanes per season in previous decades [6]. These extreme meteorological phenomena pose a threat to both population security and regional infrastructure. Furthermore, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) estimates that the economic damages caused by natural disasters related to climate change equate to 1.5% of the region’s annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [7,8,9].

Latin America has experienced an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, ranging from prolonged droughts to torrential rains and devastating floods. These phenomena are intrinsically linked to global climate change, which has altered climate patterns in the region and triggered a series of secondary effects on ecology, economy, and urban infrastructure [10,11].

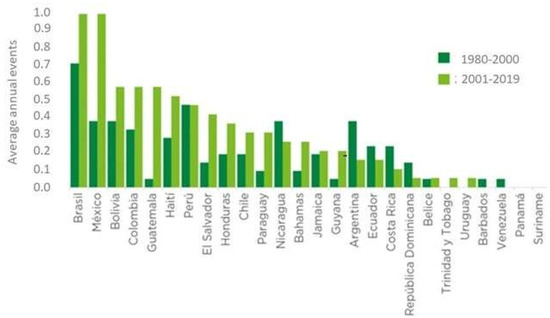

Figure 1 illustrates the behavior of climatic events experienced by the region, showing a notable increase in the occurrence of these phenomena, with Peru ranking fourth and sustaining indices above the regional average. This positioning emphasizes the urgent need to address and mitigate the risks associated with these events in the country.

Figure 1.

Frequency of extreme climate events in Latin America and the Caribbean 1980–2019 [1].

Peru, with its geographical diversity spanning from the Pacific coast to the high peaks of the Andes and the Amazon rainforest, has not been immune to these changes. The impacts of climate change have become evident nationwide, from the loss of glaciers in the mountains to decreased precipitation on the coast and the emergence of unpredictable climatic patterns in the rainforest [12,13].

In the regional context, the city of Huaraz, located in the Ancash region of Peru, faces significant challenges due to its vulnerability to extreme natural events. Despite being surrounded by majestic peaks and breathtaking natural beauty, the city is threatened by a range of hazards, including landslides, mudslides, and river floods, jeopardizing the safety of its residents, local infrastructure, and the community’s quality of life [14].

This vulnerability is exacerbated by concrete data revealing the frequency and severity of these events in the region. For instance, recent studies have shown an increase in the frequency of landslides and mudslides in mountainous areas such as the Ancash region [15]. Furthermore, climate change has heightened the magnitude and frequency of extreme weather events in Peru, including heavy rainfall and river overflow, escalating the risk of flash floods and related disasters [16].

In response to this situation, it is crucial for local and national authorities to implement disaster-risk-management measures and adopt sustainable urban-development strategies to mitigate the negative impacts of these events in Huaraz City and other vulnerable areas in the region [17].

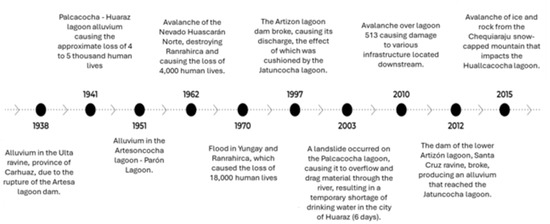

In particular, the catastrophic events in Huaraz’s history (Figure 2) still resonate in the collective memory of the city [18].

Figure 2.

Hazard history by year and location [19].

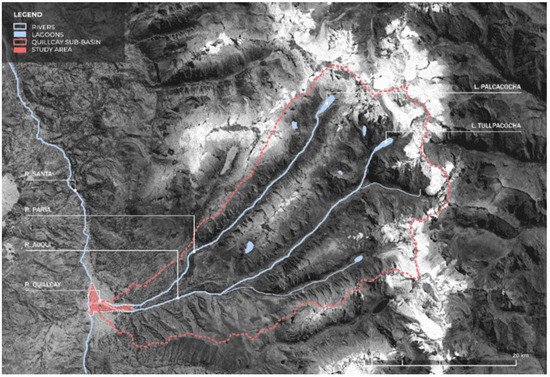

The melting of the snow-capped mountains and the consequent overflowing of the Palcacocha lagoon in 1941 unleashed a devastating flood that left a tragic toll of thousands of victims and a deep mark on the city (See Figure 2). In studies carried out after the earthquake, it was deduced that due to the depth of the rock basement at the bottom, there was an ancient alluvial channel, covered with later depositions of filling material; and in the vicinity of the Plaza de Armas, two alluvial horizons were found, which could be related to the same number of alluvial deposits that have passed through the Quillcay River. This tragic event is a perennial reminder of Huaraz’s vulnerability to natural hazards (See Figure 3), especially landslides, which threaten during the rainy season.

Figure 3.

Location of glaciers and snow peaks near the city of Huaraz [20].

Today, the city of Huaraz faces a new and growing set of challenges related to global climate change, which has intensified extreme weather patterns and increased the likelihood of heavy rain in and around Huaraz. The region has experienced an increase in the frequency of mudslides in recent years, with an average of five recorded events annually since 2018. This phenomenon has led to greater exposure of the city to landslides, mudslides, and river flooding. Urban planning and design play a fundamental role in reducing the city’s vulnerability to natural risks [21].

However, in Huaraz, the lack of adequate planning has led to the disorderly expansion of informal settlements and precarious housing in areas prone to floods [22]. The inadequacy of urban regulations is evident in the expansion of informal housing in peripheral areas and on the banks of rivers, where the population has settled without considering technical criteria or construction regulations [23]. According to the latest national census, over 60% of the population of Huaraz resides in areas vulnerable to mudslides and other natural disasters [24]. A prominent example of this problem is the urbanization of Nueva Florida, built in the alluvial cone formed by the 1941 disaster [25].

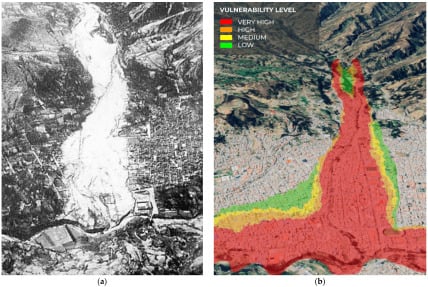

In the comparison presented, an intrinsic connection is evident between the past and present risks of landslides in Huaraz. The historic photograph, captured after the devastating 1941 flood, sheds light on the extent of the destruction suffered by the city at the time. This image of the past still resonates today, as demonstrated by Figure 4, which reveals that the alluvium pattern continues to be a latent threat on the danger map. The presence of housing and human activities in areas marked as dangerous highlights the lack of adequate planning and the inadequacy of urban regulations. This continuity in risk raises critical questions about urban resilience and the need for design and planning strategies to mitigate flood hazards in contemporary Huaraz.

Figure 4.

(a) Aerial photograph showing the white footprint of the 1941 alluvium, reprinted with permission from Ref. [26], 1947, Heim; (b) Vulnerability Map [27], 2023, Copernicus Satellite.

This pattern of inadequate and disorganized urban development has placed a significant portion of the population in a position of extreme vulnerability [28]. These inhabitants live in precarious housing that lacks the necessary conditions to resist the onslaught of natural events such as floods [29].

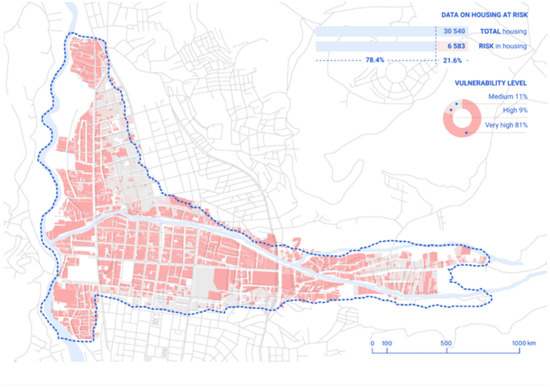

The vulnerability analysis of the study area reveals that 81% of homes have very high vulnerability, 8% have high vulnerability and 11% have medium vulnerability (See Figure 5). Regarding structures of local importance, 3% present very high vulnerability, 26% high vulnerability, 60% medium vulnerability, and 11% low vulnerability. These data underline the urgency of addressing the vulnerability of infrastructure and housing in Huaraz to guarantee the safety of the population against natural risks.

Figure 5.

Aerial photograph showing the white footprint of the 1941 alluvium, reprinted with permission from Ref. [22], 1947.

In this context, it is essential to understand how resilient urbanism, as a general approach, can provide effective solutions to address the growing threat of landslides and other natural disasters in urban areas [30]. The research introduces innovative methodologies such as the use of advanced modeling tools and risk-scenario simulations to enhance the precision and effectiveness of our urban-planning strategies. Resilience-oriented urban planning not only seeks to mitigate risks [31] but also promotes the adaptation of cities to changing climate conditions, guaranteeing the safety of their inhabitants and the long-term sustainability of urban communities [32]. By incorporating these innovative practices, we set a new standard for integrating technology and ecological considerations into the urban-planning process, thereby enhancing our ability to respond adaptively to environmental challenges.

Therefore, the objective of this research is to propose a master plan for urban resilience and flood prevention in Huaraz.

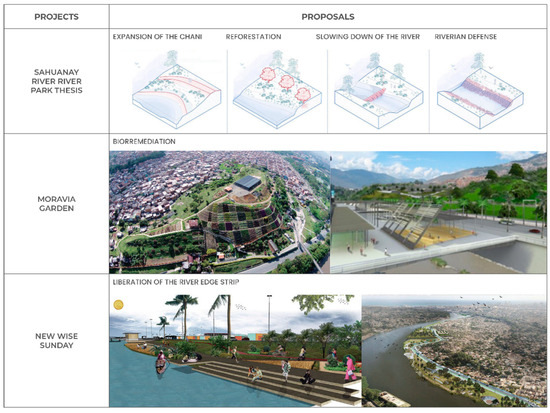

Figure 6 illustrates a variety of urban-regeneration projects that integrate ecological, social, and infrastructural improvements to enhance community life. The “Sahuanay River Park Thesis” focuses on the expansion of river channels, reforestation, and implementing measures to slow down the river flow, all aimed at preventing flooding while increasing green public spaces. ‘Moravia Garden’ showcases bioremediation techniques used to transform polluted sites into vibrant public parks that serve both ecological and recreational purposes. Lastly, the ‘Liberation of the River Edge Strip’ demonstrates a project dedicated to reclaiming riverbanks for public use, promoting accessibility and leisure activities alongside the river. These examples highlight approaches to urban design that prioritize environmental resilience and community well-being.

Figure 6.

Projects Proposals.

Some limitations that may arise in the research of “Resilient urban-design strategies for landslide risk mitigation in Huaraz, Peru” include the following:

- The participation and acceptance of the local community are crucial for the success of the proposed strategies. However, resistance or lack of understanding about the importance of the interventions may arise.

- Local policies and administrative bureaucracy can delay or hinder the implementation of strategies, especially without strong governmental support.

- Although the strategies are based on climatic studies, the unpredictable nature of climate change may introduce unforeseen variables affecting the effectiveness of proposed measures.

- Solutions specifically designed for Huaraz may not be easily scalable and replicable in other regions with different geographical and socioeconomic characteristics.

- The successful implementation of certain strategies may depend on access to advanced technologies and specialized knowledge that may not be locally available.

These limitations underscore the importance of addressing research and strategy implementation with a flexible and adaptive approach, considering local conditions and resources.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Scheme

Figure 7 describes the stages and process of the investigation. Phase 1 focuses on the literature review, where scientific publications, government reports, and relevant documents from reliable sources, including MDPI and government agencies, are consulted to identify risk indicators of alluvium in urban areas, specifically in Huaraz. Phase 2 addresses the detailed analysis of the site, examining the climate, flora, fauna, and topography of the region, using data from SENAMHI and the National Forest Service to determine the influence of these factors on the city’s vulnerability to floods.

Figure 7.

Research stages diagram.

In phase 3, the most effective resilient urban-design strategies are identified to address the problems detected, based on previous analyses. This phase includes the proposal of urban and architectural interventions that mitigate the risk of landslides. Phase 4 culminates with the discussion and conclusion, where the impact of the proposed strategies on risk mitigation is evaluated, comparing the findings with similar experiences in other urban areas and using data from scientific publications and government reports to validate the effectiveness of the suggested measures. This comprehensive methodological approach ensures a deep understanding of the problem and facilitates the generation of practical and replicable solutions for urban resilience in Huaraz.

This research is carried out under a non-experimental approach. It begins with the collection of information from scientific and government sources. Data relevant to the topic is then identified and classified. Finally, design strategies are applied to meet the study objectives.

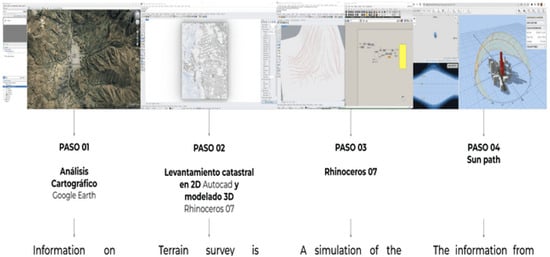

Figure 8 outlines the essential steps for the implementation of our proposed resilient urban-design strategies aimed at mitigating the risk of landslides in Huaraz. Step 01 involves using Google Earth to acquire data on terrain topography, road infrastructure, urban density, and proximity to bodies of water, providing a fundamental understanding of the city’s exposure to flood risks. Then, in Step 02, we use Rhinoceros 07 to carry out a terrain survey and create a three-dimensional model that calculates the topography of the study area. In Step 03, also using Rhinoceros 07, we simulate the raised terrain, considering factors such as rainfall and possible water channels that could be generated in the event of floods, allowing us to evaluate different risk scenarios.

Figure 8.

Steps for the implementation of the proposal.

2.2. Study Area

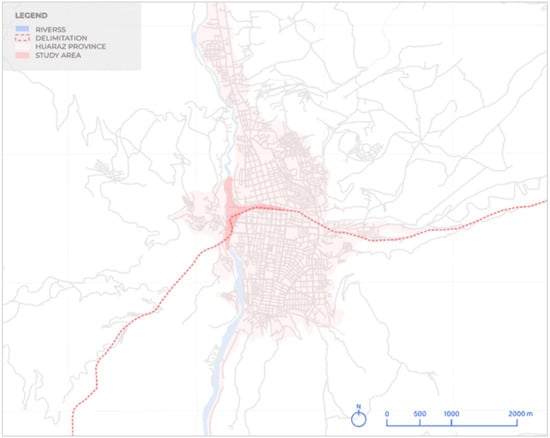

The city of Huaraz is located in the Áncash region, in northern Peru (Figure 8). It borders to the north with Independencia, to the east with Olleros, to the south with the district of Tarica, and to the west with the district of Recuay. Huaraz is located in the heart of the Andes Mountain range. It is crossed by the Santa and Quillcay rivers that form the basin in which it is located. The latitude is −9.5253847399186 and the longitude is −77.52861889191409 (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Location of the Province of Huaraz.

2.3. Climate Analysis

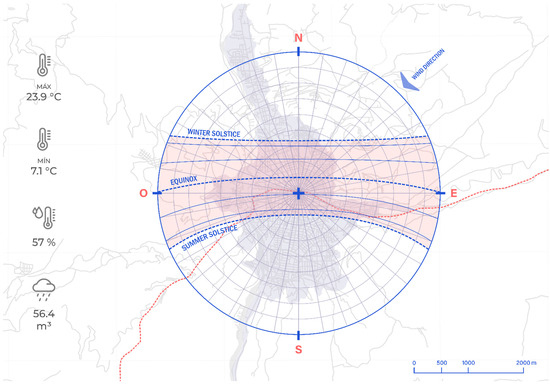

Figure 10 presents the analysis of the solar map of Huaraz, outlining the specific periods within the year characterized by greater solar exposure on the building facades.

Figure 10.

Climate analysis of Huaraz.

The climate in Huaraz plays a crucial role in the city’s vulnerability to landslides, particularly due to its unique topography and marked seasonal variations. Located in the Andean region, the city experiences dry winters and mild summers, with temperatures ranging between 27 °C and −1 °C. However, it is the rainfall pattern that deserves special attention in this analysis. Rainfall is most intense and frequent from January to March, reaching its maximum in February with 143 mm. This concentration of precipitation in a short period significantly increases the risk of landslides, given that the saturation of the soil, combined with the rugged topography, facilitates the rapid movement of material to lower areas.

Furthermore, the variability of humidity, which varies from 66% to 79% throughout the year, and the drastic decrease in rainfall to about 4 mm between June and August, highlight the importance of considering this rainfall in the design of resilient urbanism strategies. The predominant northeasterly winds and constant solar radiation directly affect evaporation and soil humidity, critical factors in the predisposition to landslides. Therefore, the analysis of precipitation is essential not only to identify the periods of greatest risk but also to inform the development of resilient infrastructure that mitigates the destructive effects of floods, thus ensuring the protection of the population and the integrity of Huaraz. face these climate challenges.

2.4. Environmental Analysis, Flora

The flora in Huaraz plays an essential role in preventing flood risks, particularly in mitigating soil erosion. The Andean region is home to a wide variety of plant species adapted to its unique environment. The native flora of Huaraz includes species such as queñual, puya, and ichu as well as various Andean plants adapted to challenging climatic and topographic conditions (See Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Flora and green areas of Huaraz.

These plant species have strong roots and anchoring systems that help stabilize soil in mountainous and steep areas. Its dense roots act as an effective soil retention system, preventing erosion and reducing the risk of landslides and mudslides. Additionally, its ability to retain water and release it slowly helps reduce runoff and prevent flooding during times of heavy rain [33,34].

The conservation and promotion of this native flora in resilient urban-design strategies are essential to prevent flood risks in Huaraz. By incorporating green areas, parks, and the preservation of existing vegetation in urban development, the city’s ability to withstand extreme natural events can be strengthened. Furthermore, these green areas not only improve the city’s resilience to floods but also contribute to the quality of life of the inhabitants and the long-term sustainability of the urban environment.

3. Results

3.1. Location of the Urban Proposal

The urban proposal is strategically located in the city of Huaraz, which, in the geographical context of the department of Ancash, Peru, faces significant challenges related to its vulnerability to floods. In this context, the land in question takes on great value, since it allows us to intervene directly in areas prone to natural risks.

The choice of Huaraz for the implementation of the master plan for urban resilience and flood prevention is based on the need to specifically and efficiently address the problems associated with the topography of the region. Furthermore, the city, surrounded by impressive natural beauty, offers a favorable setting to merge sustainable urban development with risk prevention, establishing an exemplary model that improves the quality of life of its inhabitants and serves as a reference to face geographical challenges. unique in the region (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Location of the Urban Planning proposal.

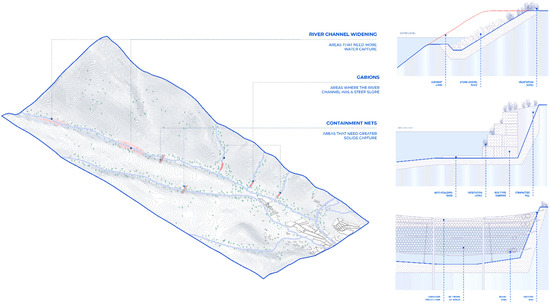

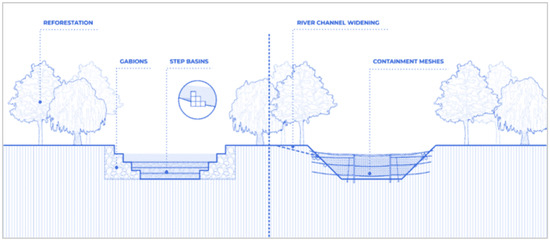

3.2. Master Plan

Figure 13 details the first phase of the upstream proposal. It shows the expansion of the Quillcay River channel, the strategic placement of gabions, the creation of a stepped bank, the installation of containment meshes, and the reforestation of the area. These measures are crucial to preventing risks from landslides, mitigating environmental impacts and improving community safety.

Figure 13.

Phase 1 Mitigation of the impact of the increase in flow of the Quillcay River.

In Phase 1, focused on mitigating the impact of the increased flow of the Quillcay River, we propose fundamental preventive strategies such as widening the river channel by 30 m in width to manage water flow and reduce the risk of overflows during extreme events. The proposed installation of containment meshes and gabions, along 2 km of the river, seeks to strengthen the riparian structures, offering resistance to possible erosion and contributing to the stability of the environment (Figure 13).

The creation of a stepped bank, proposed in sections of 500 m, not only improves the aesthetics of the landscape but also acts as a natural barrier, dissipating water energy in a controlled manner. These measures would be complemented by the reforestation of areas near the river, using native species in an area of 5 hectares, to preserve the local ecosystem and function as a natural water retention and landslide prevention system (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Trees, Gabions, Containment Mesh, Stepped Basin.

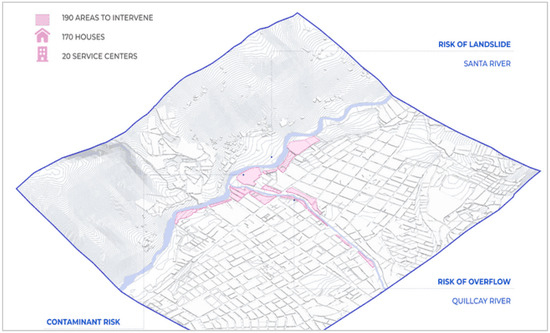

Phase 2 of the master plan proposes the strategic relocation of 170 homes and 20 service centers, a planned measure to free up critical areas and allow the implementation of resilient urban projects in Huaraz. This proposal seeks not only to develop valuable public spaces, such as outdoor esplanades, sports riverbanks, multifunctional terraces, and a large linear park but also to safeguard the population against possible natural risks.

The management of these relocated spaces is planned comprehensively, considering the creation of habitable, sustainable, and safe environments. In addition, it seeks to preserve social cohesion by maintaining essential services close to the new locations, thus promoting the quality of life of the community affected by the relocation (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Phase 2 Management of intervened spaces—areas with potential for relocation.

Within the second phase of our urban-resilience project in Huaraz, a series of key projects are proposed, such as the creation of an outdoor esplanade, a sports riverbank, multifunctional terraces, and a large linear park. These projects are designed to strengthen the city’s capacity to confront natural risks and improve the quality of life of its inhabitants.

The open-air esplanade, located at the confluence of the Santa River and the Quillcay River, is intended to be a multifaceted space for community events. This location is consciously chosen as a high-risk area, relocating homes to create an open space that encourages community integration and serves as a focal point for meaningful gatherings. The transformation of this area into an esplanade responds to a proactive approach to mitigation and adaptation, implementing specific security measures that counteract potential risks. By turning a place of vulnerability into a valuable community resource, it demonstrates a commitment to creating resilient and safe urban environments, while promoting cohesion and social well-being in Huaraz.

The sports riverfront, planned along these relocated areas, will boost physical activity and health in the community, equipped with sports facilities for various activities.

The multifunctional terraces will be strategically designed, and enriched with plant species such as queñual (Polylepis spp.), Puya raimondii, and ichu (Stipa ichu), selected for their ability to absorb CO2. These species will not only contribute to carbon capture but also the conservation of local biodiversity, functioning as viewpoints, plazas, and playgrounds that offer panoramic views and recreational areas (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Urban resilience master plan.

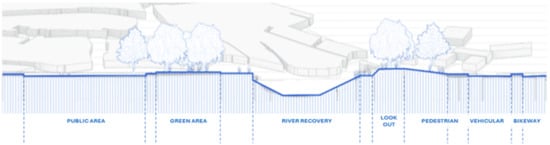

The large linear park, designed as the centerpiece of our urban initiative in Huaraz, stands as an emblem of sustainability and multifunctionality. This space actively promotes sustainable mobility through an extensive cycle path, strategically incorporated to encourage eco-friendly travel among citizens. In addition, responsible environmental management is encouraged through the inclusion of recycling stations, intended for the segregation and recycling of waste. Enriched with works of public art that narrate the history of the town, the park is illuminated with highly energy-efficient systems, specifically through the use of solar panels, which provide a source of clean and renewable energy, guaranteeing sustainable lighting during the night hours.

As for street furniture, it is manufactured from recycled materials such as recovered plastic and recycled wood, selected for their durability and low environmental impact. These materials not only give the park an attractive and contemporary aesthetic but also reflect a firm commitment to sustainability practices. By distributing approximately 200 LED solar lights throughout the park, optimal energy efficiency is ensured, reducing electricity consumption and contributing to the reduction of the community’s carbon footprint. This conscious and holistic design underscores our commitment to improving the urban environment and community well-being, positioning the large linear park not only as a place of recreation but also as a pillar of environmental education and sustainability for Huaraz (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Linear Park cut.

The urban and environmental regeneration project in Domingo Savio, Santo Domingo, stands out for its comprehensive approach to addressing significant challenges in the community. Its vision of connecting the sector with its environment and the city, facilitating internal mobility, and providing it with new public facilities [35], is a strategy that resonates with our proposal in the master plan for urban resilience and flood prevention in Huaraz. Both projects share the idea of generating multifunctional public spaces to improve the quality of life of residents. Furthermore, the priority of the Domingo Savio project to free the strip of the river’s edge and develop a linear river park with safety measures reflects our focus on the part before the river enters the city, where we propose the expansion of the channel, meshes of containment, gabions, and reforestation as preventive measures against alluvial risks. Although both projects share a comprehensive vision, our focus on Huaraz stands out for its emphasis on specific strategies for preventing flood risks, taking advantage of the knowledge of the topography and geographic conditions of the region [36].

The Rímac River Special Landscape Project in Lima stands out for its initiative in the face of the significant degradation of the river in the Historic Center. It addresses the physical-visual disconnection, pollution, and the loss of its character as a green corridor [23]. Similar to our urban-resilience master plan in Huaraz, both projects seek to generate a green corridor and promote sustainable mobility. The PEPRR identifies actions to address urban regeneration, improving the riverbed, creating public spaces, and promoting active mobility. As the PEPRR seeks to recover the essence of the ecological green corridor, our master plan not only shares that characteristic but incorporates innovative and resilient solutions that specifically align with the unique characteristics of Huaraz.

Figure 18 presents a SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) of the urban-resilience plan for Huaraz, Peru. This analysis categorizes key aspects of the plan into four distinct areas: strengths, which highlight the plan’s advantages and positive attributes; weaknesses, which detail the limitations and areas for improvement; opportunities, which describe potential benefits and favorable external factors; and threats, which consider possible challenges and risks. Each category is further subdivided into social, environmental, cultural, and economic impacts, providing a comprehensive overview of the plan’s multifaceted approach to urban resilience. This SWOT analysis aids in identifying strategic areas that require attention and reinforcement, ensuring that the plan effectively addresses the diverse needs of Huaraz and sets a replicable model for other cities facing similar challenges.

Figure 18.

SWOT analysis.

4. Discussion

Latin America is particularly affected by climate change, posing a global challenge for communities worldwide. Analyzing real cases of cities facing similar challenges and taking measures to reduce risks associated with climate change and natural disasters highlights the need to address this issue comprehensively.

The example of Rotterdam in the Netherlands shows how cities can confront and adapt to the impacts of climate change globally. Rotterdam is renowned for its innovative urban-resilience strategy, implemented through actions such as constructing floating neighborhoods and developing green areas to absorb excess rainwater [37]. The implementation of this approach has positioned Rotterdam as a benchmark for urban resilience, demonstrating that adaptability and collaborative efforts among government, private sector, and community are effective tools to counteract the effects of climate change.

In Latin America, an outstanding example is Medellín, Colombia. This city has achieved impressive transformation in its infrastructure and urban planning to address the challenges of climate change. Innovative projects like the Spain Library Park were implemented in Medellín. In addition to providing community spaces, this project incorporates sustainable technologies and water management practices [38]. These measures have helped decrease the city’s vulnerability to natural phenomena and enhanced the well-being of its residents.

Another similar case is found in Buenos Aires, Argentina, which developed the Resilience Plan as a strategy addressing various urban challenges, including those related to climate change. This initiative was created by the city government with the purpose of increasing the city’s capacity to face, adapt to, and recover from both climate change and other adverse events [39]. Comparing this reference with the proposal in Huaraz, some significant similarities and differences can be observed. Both plans’ primary objective is to enhance cities’ capacity to face risks linked to extreme weather events such as floods and landslides. They both recognize the relevance of urban planning and resilient design to reduce vulnerability in local communities. However, cities present contrasts in terms of their geographical location and the specific obstacles they face. While Huaraz is situated in a mountainous area dealing with specific risks related to high peaks and glaciers, Buenos Aires is a coastal city facing challenges like urban flooding and rising sea levels.

Analyzing these cases in relation to the context presented in the baseline text about Huaraz, Peru, several significant insights can be gained. Firstly, it becomes evident that urban resilience does not follow a standard approach, and effective solutions must adapt to each city’s particularities and natural environment. Additionally, the success of any climate change adaptation initiative depends on collaboration across different sectors and community participation. However, it is noticeable that numerous cities in Latin America experience unique challenges, such as limited economic resources and the fragility of governmental entities, which may hinder adaptation actions. Therefore, it is essential for local governments to be supported both nationally and internationally to strengthen their capacity to address climate change.

In the research “Resilient urban-design strategies for landslide risk mitigation in Huaraz, Peru,” it is plausible that a generalized costing method has been used to establish priorities [40,41]. This comprehensive approach is crucial for accurately estimating costs associated with the construction, operation, and maintenance phases of various proposed interventions, such as reforestation, drainage system installation, and construction of retaining walls [42,43]. The use of a generalized costing method not only allows for detailed financial assessment but also facilitates the optimization of resource allocation. This ensures that prioritized interventions are those with the greatest impact on risk reduction and improvement of urban resilience, thereby maximizing return on investment in terms of safety and sustainability for the Huaraz community.

In summary, by analyzing urban resilience cases worldwide, we can leverage experiences from other cities and adapt lessons learned to our own local realities. Although each city faces unique challenges, building safer and more resilient cities in the future fundamentally depends on collaboration, innovation, and commitment to sustainability.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the urban resilience and flood prevention master plan in Huaraz stands out for its comprehensive approach and specific adaptation to the region’s geographical characteristics. This plan demonstrates an efficient use of detailed knowledge of local topography, prioritizing precise strategies to mitigate flood risks. The proposed measures, including river channel widening, installation of retaining walls and gabions, creation of stepped basins, and reforestation, not only address immediate hazards but also establish robust preventive infrastructure. This preventive approach is key to minimizing flood-related risks before the river enters the city, thus ensuring the long-term sustainability and safety of Huaraz. The combination of structural and natural solutions underscores the importance of integrating engineering interventions with ecological practices, promoting urban resilience that effectively adapts to the region’s specific environmental challenges.

Furthermore, the proposal for the urban area incorporates a series of elements designed to improve the quality of life and foster social integration, notable for its focus on sustainable development and the creation of multifunctional public spaces. The inclusion of an outdoor plaza for community events, a riverside sports area, multifunctional terraces serving as viewpoints, squares, and play areas, as well as an extensive linear park, not only beautify the urban environment but also provide versatile spaces adaptable to various community activities and needs. These interventions not only promote social cohesion by offering meeting points and recreational spaces but also support residents’ health and well-being by facilitating access to outdoor activities and promoting an active lifestyle. By integrating these elements, the proposal significantly contributes to urban sustainability, ensuring that public spaces are inclusive, accessible, and useful for everyone, ultimately reinforcing the social fabric and enhancing community resilience.

Lastly, the innovation and resilience of our proposal are highlighted by specifically aligning with the unique characteristics of Huaraz, offering a comprehensive strategy addressing multiple dimensions of urban development. By focusing on both urban regeneration and risk prevention, the proposal not only mitigates environmental threats but also significantly improves the community’s quality of life. Measures such as river channel widening and reforestation in strategic areas before their entry into the city are crucial for reducing environmental risks, especially floods. These natural interventions not only manage immediate risks but also contribute to long-term ecological sustainability. On the other hand, the proposed urban facilities foster social cohesion and well-being, creating multifunctional public spaces that promote community interaction and a healthy lifestyle. This combination of risk mitigation infrastructure and integrated urban improvements demonstrates a holistic approach that not only protects Huaraz from environmental threats but also builds a more united and resilient community, prepared to face future challenges.

In summary, the master plan not only offers specific solutions to prevent natural risks but also proposes a complete vision of sustainable urban development. The combination of preventive strategies and innovative urban elements reflects our commitment to the resilience and comprehensive improvement of Huaraz.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E. and J.M.; methodology, L.S.; software, J.C.; validation, C.V., V.R. and D.E.; formal analysis, J.M.; investigation, L.S.; resources, C.V.; data curation, V.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.E.; writing—review and editing, J.M.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, C.V.; project administration, V.R.; funding acquisition, D.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data are in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our special thanks and gratitude to the colleagues who gave us the golden opportunity to carry out this wonderful project on resilient urban-design strategies for landslide risk mitigation in Huaraz, Peru.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Machado, R.; Beatriz, I. Urbanismo Resiliente Desde la Perspectiva del Cambio Climático en España. El Caso de las Inundaciones. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alejos, L.; Cuáles son los Riesgos Fiscales de los Eventos Climáticos Extremos y Cómo Enfrentarlos? Gestión Fiscal. Inter-Amernican Development Bank. 2021. Available online: https://blogs.iadb.org/gestion-fiscal/es/cuales-son-los-riesgos-fiscales-de-los-eventos-climaticos-extremos-y-como-enfrentarlos/ (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- IPCC. Informe Especial Sobre el Calentamiento Global de 1.5 °C; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, A.; Esenarro, D.; Martinez, P.; Vilchez, S.; Raymundo, V. Thermal Calculation for the Implementation of Green Walls as Thermal Insulators on the East and West Facades in the Adjacent Areas of the School of Biological Sciences, Ricardo Palma University (URP) at Lima, Peru 2023. Buildings 2023, 13, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenarro, D.; Vasquez, P.; Morales, W.; Raymundo, V. Interpretation Center for the Revaluation of Flora and Fauna in Cusco, Perú. Buildings 2023, 13, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Reyes, J.L.; Salcedo-Marcelo, S.S.; Montoya, O.D. Application of the Hurricane-Based Optimization Algorithm to the Phase-Balancing Problem in Three-Phase Asymmetric Networks. Computers 2022, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID). Informe Sobre el Impacto Económico de los Desastres Naturales en América Latina y el Caribe. Available online: https://www.iadb.org/es (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- USAID. Quillcay Plan de Accion Local Para la Adaptación al Cambio Climatico. Usaid.gov. Available online: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00KNV6.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil del Peru (INDECI). Informe de Emergencia; INDECI: Lima, Peru, 2023; Available online: https://portal.indeci.gob.pe/emergencias/informe-de-emergencia-no-931-5-4-2023-coen-indeci-0050-horas-informe-n-22-lluvias-intensas-en-el-departamento-de-lima-provincias-dee/ (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Benito, G.; Corominas, J.; Moreno, J.M. Impactos sobre los riesgos naturales de origen climático: Riesgo de crecidas fluviales. In Evaluación Preliminar de los Impactos en España por Efecto del Cambio Climático Proyecto ECCE—Informe Final; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2005; Volume 52, pp. 5–548. [Google Scholar]

- Esenarro, D.; Cho, A.; Vargas, N.; Calderon, O.; Raymundo, V. Chinchero as Tourism Hub and Green Corridor as a Social Integrator in Cusco Peru 2023. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.S.; Alfthan, B.; Baker, E.; Hesping, M.; Schoolmeester, T.; Verbist, K. El Atlas de Glaciares y Aguas Andinos: El Impacto del Retroceso de los Glaciares Sobre los Recursos Hídricos; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Amaya, P.; Vega, V.; Esenarro, D.; Cuya, O.; Raymundo, V. Evaluation of the Functional Connectivity between the Mangomarca Fog Oasis and the Adjacent Urban Area Using Landscape Graphs. Bosques 2024, 15, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, J.A.S. Huaraz a 52 Años del Terremoto de 1970: Lecciones no Aprendidas. Desde Sur 2022, 14, e0006. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2415-09592022000100006&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed on 6 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Ambiente del Peru. Informe Nacional sobre Cambio Climático 2022; Ministerio del Ambiente: Lima, Peru, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huaraz Provincial Municipality. Plan de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres de la Ciudad de Huaraz; Municipalidad Provincial de Huaraz: Huaraz, Peru, 2023; Available online: https://sigrid.cenepred.gob.pe/sigridv3/documento/15169 (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil del Peru (INDECI). Reporte Anual de Desastres 2023; INDECI: Lima, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner, S.A. Lo que el Agua se llevó Consecuencias y Lecciones del Aluvión de Huaraz de 1941. Nota Técnica n° 7. 2014. Available online: https://repositoriodigital.minam.gob.pe/handle/123456789/834 (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- [INAIGEM] Informe de Evaluación del Riesgo por Aluvión en la Ciudad de Huaraz, distritos de Huaraz e Independencia, provincia de Huaraz, Departamento de Ancash. (Biblioteca SIGRID). Gob.pe. Available online: https://sigrid.cenepred.gob.pe/sigridv3/documento/12502 (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Satelite Copernicus. Ubicación de Glaciares y Nevados Cercanos a la Ciudad de Huaraz. Google.com. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/search/Huaraz/@-9.49835074,-77.43760689,4008.95124293a,55018.15912516d,35y,0h,0t,0r/data=CigiJgokCSYlWvo0QjFAEZs0QqBfHTnAGVRLbtVpRznAIcei2bHAe2DAOgMKATA (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Barton, J.R.; Irarrázaval, F. Adaptación al Cambio Climático y Gestión de Riesgos Naturales: Buscando síntesis en la Planificación Urbana. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2016, 63, 87–110. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?pid=S0718-34022016000100006&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 14 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Vilaró Caldera, R. Vulnerabilidad Urbana Asociada a Riesgos de Desastres Área Central y Pericentral de Puerto Montt. 2017. Available online: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/144205 (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Alvarez Jaramillo, M.M.; Rosales Leon, D.Y. Las Construcciones Informales y el Impacto en la Imagen Urbana de la Franja Marginal Malecón del Sector 4 Provincia de Huaraz, Ancash-2022. Master’s Thesis, Universidad César Vallejo, Trujillo, Peru, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática del Peru (INEI). Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2020; INEI: Lima, Peru, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- SENAMHI—Peru. Gob.pe. Available online: https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?p=pronostico-detalle-turistico&localidad=0013 (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Heim, A. Fotografía Aérea Mostrando la Huella Blanca del Aluvión, Peru. 1941. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Terminal-moraine-failure-Huaraz-Peru-Photos-Hans-Kinzl-and-Erwin-Schneider-above_fig8_313428924 (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Satelite Copernicus. Ciudad de Huaraz. Google.com. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/search/Huaraz/@-9.52452843,-77.51793915,3116.83828451a,4196.90067736d,35y,88.97440882h,77.84739653t,0r/data=CigiJgokCSYlWvo0QjFAEZs0QqBfHTnAGVRLbtVpRznAIcei2bHAe2DAOgMKAT (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands. Climate Adaptation Strategy for the City of Rotterdam. 2020. Available online: https://www.government.nl/topics/themes/building-and-housing (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Alcaldía de Medellín. Parque Biblioteca España. Sin Fecha. Available online: https://www.medellin.gov.co/irj/portal/medellin?NavigationTarget=navurl://d0b45dab06b2c2e5c059c1571a5e911d (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Plan de Resiliencia de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. 2021. Available online: https://buenosaires.gob.ar/jefedegobierno/secretariageneral/buenos-aires-ciudad-resiliente (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Mula, J.; Poler, R.; García, J.P. Evaluación de Sistemas para la Planificación y Control de la Producción/Evaluation of Production Planning and Control Systems. Inf. Tecnol. 2006, 17, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armela Blanco, L. El costeo objetivo en el proceso de planeación. Cofin Habana 2017, 11, 192–205. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2073-60612017000200014&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Lara Pulido, J.A.; Estrada Díaz, G.; Zentella Gómez, J.C.; Guevara Sanginés, A. Los costos de la expansión urbana: Aproximación a partir de un modelo de precios hedónicos en la Zona Metropolitana del Valle de México. Estud. Demogr. Urbanos 2017, 32, 37–63. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0186-72102017000100037&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed on 6 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Pérez Pulido, L.A.; Romo Aguilar, M.D.L. Planes de desarrollo urbano: Instrumentos de legitimación en la expansión urbana de Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. Estud. Demogr. Urbanos 2022, 37, 85–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomeque, R.; Gerardo, L. Método Sistemático de Rehabilitación de Grandes Conjuntos Urbanos. In Proceedings of the II Jornadas de Investigación en Arquitectura y Urbanismo, Madrid, Spain, 17–19 June 2009; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Cubillos González, R.A.; Trujillo, J.; Cortés Cely, O.A.; Rodríguez Álvarez, C.M.; Villar Lozano, M.R. La habitabilidad como variable de diseño de edificaciones orientadas a la sostenibilidad. Rev. Arquit. 2014, 16, 114–125. Available online: https://revistadearquitectura.ucatolica.edu.co/article/view/64 (accessed on 29 August 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tapia, M. La Rehabilitación de los Centros Históricos: Criterios de Análisis para una Intervención Inclusiva en Galicia. 2021. Available online: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/CyTET/article/view/82763/66708 (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Soto Salazar, P. Gestión del riesgo en Copiapó: Hacia la Construcción de una Propuesta Metodológica Resiliente. 2019. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_url?url=https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/170456&hl=es&sa=T&oi=gsb&ct=res&cd=0&d=15983604176501525579&ei=Yx4NZarSAb6vy9YPzeClwAQ&scisig=AFWwaeaiX5gkiehJg8G-klu43HzU (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Aguinaga Arancibia, P. Borde Nueva Chaitén: Parque de Mitigación: Diseño Urbano Resiliente para la Capital Provincial de Palena, Región de Los Lagos. 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/169964 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- González-Besada Allué, P. Vivienda Resiliente: Estrategias de Autosuficiencia Frente a Crisis. Arquitectura. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Echevarría, C.; Alipio, A. Análisis de la Composición de la Flora Vascular del Departamento de Áncash (Peru); Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos: Lima, Peru, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Procesos de Regeneración Urbana en Asentamientos Humanos Informales. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355241917_Procesos_de_regeneracion_urbana_en_asentamientos_humanos_informales (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Proyecto Especial Paisajístico Río Rímac. Available online: https://smia.munlima.gob.pe/uploads/documento/4f3a30ece4627ece.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).