Abstract

With the growth in popularity of video games in our society many teachers have worked to incorporate gaming into their classroom. It is generally agreed that by adding something fun to the learning process students become more engaged and, consequently, retain more knowledge. However, although the characteristics of video games facilitate the dynamics of the educational process it is necessary to plan a pedagogical project that includes delimitation of learning goals and profile of the addressees, the conditions of application of the educational project, and the methodologies of evaluation of the learning progress. This is how we can make a real difference between gamification and video game based learning. The paper addresses the design of an educational resource for special education needs (SEN) students that aims to help teach communicative skills related to prosody. The technological choices made to support the pedagogic issues that underlie the educational product, the strategies to convert learning content into playful material, and the methodology to obtain measures of its playability and effectiveness are described. The results of the motivation test certified that the video game is useful in encouraging the users to exercise their voice and the indicators of the degree of achievement of the learning goals serve to identify the most affected prosodic skills.

1. Introduction

In recent years, we have seen the emergence of different initiatives for the integration of technological tools in educational environments, although it has been achieved in a very heterogeneous way. Even with the increasing availability of resources and applications in the educational world, it is hard to find the necessary documentation to profit from the potentialities of the digital devices and there is no training for teachers. Together with the emergence of the digital revolution, there is a perception that the current educational system has lost effectiveness. Technological changes and cultural digitalization have enhanced a fracture between the skills and knowledge that individuals need to develop as citizens and the formation received in school. The approach of serious games has been presented as a promising path to bridge this gap by adding something fun to the learning process, with the main aim of motivating students and keeping their attention, setting up a context that encourages the acquisition of proper habits for the learning process and completion of tasks.

The idea and use of the game as part of the educational process is not new. Besides motivation and participation, activities based on games improve the development of such social skills as the acceptance of norms or tolerance to frustration. Focusing on video games, the seminal studies in [1] and [2] have pointed out that the use of video game platforms improves general social skills and the psycho-motor development of players (also supported by [3,4,5,6,7]). Although the belief that games have a real impact in learning is not generally acknowledged (see the surveys of the research on the educational use of video games in [8,9]), there is a growing trend, from the initiative of teachers and some teacher training programs, to adopt them as strategies for teaching.

The selection of the video game as a didactic tool runs in parallel with the increase in the protagonism of the video game in the leisure and culture sector from the 1990s to the present, as shown by the evolution of its annual growth rate and the economic figures around it. To have a benchmark with other cultural sectors, the Interactive Software Federation of Europe (ISFE) reported in 2015 that the video game industry doubled the revenues obtained by the film industry and multiplied by ten those produced by the music sector. In Spain, according to the data regularly published by AEVI (Spanish Association of Video Games) to show the status and progress of the video game industry, the consumption of video games generated 1530 million euros in 2018, 12.6% more than in 2017. All this shows that the video game has become the cultural object of the 21st century by combining art, literature, image, social evolution of a community of characters, etc., and, for our purposes, this makes it a particularly interesting educational practice in a digital era.

This paper addresses the design of an educational resource for special education needs (SEN) students, particularly for individuals with Down Syndrome (hereinafter, DS), that aims to help in teaching communicative skills related to prosody. The project includes the delimitation of learning goals and learner characteristics, elements which need to be considered in the design of the game experience, and learning evaluation methodologies. This is how we can make a real difference between multimedia resources (any kind of educational activities where text, audio, images, animation, video, and interactivity are combined together), gamification (the application of typical elements of game playing in the educational context), and video game-based learning. Our methodological approach is framed within design-based research (DBR) in education, defined in [10] as “a systematic but flexible methodology aimed to improve educational practices through iterative analysis, design, development, and implementation, based on collaboration among researchers and practitioners in real-world settings, and leading to contextually-sensitive design principles and theories”. Adopted from the process of industrial development, this model conceives research as a means to guarantee the solidity, efficiency, and effectiveness of the educational products [11]. In this case, the outcome is the video game, aimed at improving the prosody of persons with DS, and the research process considers the following three moments that do not necessarily have to be carried out in a linear or unique way: (a) Analysis or conceptualization and diagnosis of the subject to detect the main needs and opportunities (Section 2); (b) Design and development; mainly, the technological choices made to support the pedagogic issues that underlie the educational product (Section 3.1), the design of the game activities (Section 3.2), and the definition of learning goals (Section 3.3); (c) Evaluation of the educational resource according to different parameters, namely establishing the extent to which user needs have been identified and user satisfaction met (Section 4.1) and observing the degree of achievement of learning goals (Section 4.2).

2. Analysis: Better Prosody, Better Communication, Better Integration

Individuals with DS present a myriad of profiles of development depending on IQ score, facial and physical features, etc., and, therefore, defining a unique linguistic behaviour is difficult, if not impossible. Among their most common language difficulties are the following: Articulation of sounds, phonological discrimination, understanding and producing morphological marks, and a very poor comprehension and production of syntax. Although they have higher command in lexico-semantic and pragmatic domains, they have less vocabulary and more problems understanding complex semantic relations than non intellectually impaired speakers. They also have difficulties with the use of mechanisms of discourse cohesion (anaphora, ellipsis, distinction between given and new information, etc.) and difficulties understanding and producing figurative language, to mention a few [12,13,14,15]. In the prosodic domain, reference [16] found better capacities of children with DS in the field of comprehension than in production and in certain tasks in which they could rely on meaning in contrast to tasks in which only the intonational pattern was offered. The case study of a sample of spontaneous speech of a moderately language-impaired adult with Down's syndrome, in [17], found a link between the number of syllables that a prosodic group contains and the phonatory and grammatical deficiencies.

The video game Pradia: Mystery in the City has been developed with the educational goal of improving the production and perception of the prosody of speakers with DS [18]. Our working hypothesis is that the correct pragmatic use of prosody is fundamental for the personal development and social integration of people with intellectual disabilities by enhancing both interaction with peers and socialization with the group. When we produce an utterance, we do not only articulate sounds, we also vary the intensity with which we speak, our tone of voice, and the speed of speech, to mention a few possible modifications. It is for this reason that we can perceive different interpretations of the same content, depending on which tone, intensity, or duration features have been chosen. These features are called prosodic or suprasegmental features, which act on continuous sequences of sounds and which are inherent to orality [19]. The prosodic features contribute significantly to the meaning of the utterances, to such an extent that sometimes we cannot understand the communicative function of a statement until we have this information [20]. The educational project proposed with the PRADIA video game is, as a global objective, that the players improve both the understanding of the messages and their production, thus gaining in communicative effectiveness.

The educational potential of the video game, and its novelty, is that the player must overcome a series of challenges and missions in an adventure developed in a stimulating game environment by means of a proper use of prosodic features (prosodic competence is understood as the ability to distinguish and produce those prosodic structures that are appropriate to given linguistic meanings, Diccionario de términos clave de ELE, Centro Virtual Cervantes). These milestones are located in a social setting of everyday situations that favour the practice of pragmatic competence (“the ability to use language effectively in order to achieve a specific purpose and to understand a language in context” [21]), and allow, as a consequence, a better command of communicative competence to be reached (“the intuitive functional knowledge and control of the principles of language usage” [22]).

2.1. ICT (Information Communications Technology) Resources for Special Education Needs

There are some existing video games targeted at people with SD that cover different topics to work on varied skills, including: Las aventuras de Spoti (The Adventures of Spoti <https://www.sindromedown.net/Spoti/default.htm>) aims to promote a healthy life, Mazi Mazorco (https://www.grupoenfoca.com/proyectos/mazi-mazorco/) explains the concept of celiac disease in a game environment, and Downtown: aventura en el metro (Downtown: a subway adventure, http://downtown.ceiec.es/proyecto/?setlang=en), through a classic story of cops and villains, collects everyday situations people with DS face when using the metro network with the goal of helping them to move on their own by public transport.

On the other hand, the web is a valuable source for educational software, videos, interactive exercises, and other digital materials with free access. If we confine the search to Special Education Needs in the Spanish context, educational goverment institutions and family associations offer a wide range of ICT solutions. To mention a few: Catálogo de Soluciones TIC para alumnado con Necesidades Específicas de Apoyo Educativo http://ticne.es/; Discapnet http://www.discapnet.es/Castellano/areastematicas/educacion/juegos_educativos/Paginas/Juegos_Educativos.aspx; Guía multimedia de recursos educativo para alumnado con necesidades educativas especiales http://redined.mecd.gob.es/xmlui/handle/11162/2471; Recursos TIC para Necesidades Educativas Especiales, http://www.educacontic.es/blog/recursos-tic-para-necesidades-educativas-especiales. Helping to improve the reading capabilities of children with DS is the goal of the app Yo también leo ("I also read") for the Spanish language, which combines images, text, and audio to offer children a playful educational environment that favors learning through visual memory (http://yotambienleo.com/app/).

However, there are no complete educational digital tools that offer, in addition to technological innovation, a theoretical and methodological reflection on what the incorporation ot these resources implies for special education needs. The focus has been on the creation of new tools, leaving how to draw up and implement a pedagogical plan that includes these tools to the choice of professionals and educators. Moreover, although the range of competences that the educational games for students with special needs aim to reach are widely varied, from learning to read to the practice of psychomotor skills with games of drag and click with the mouse [23,24], the relevance of prosody has been almost denied.

2.2. The Relevance of Prosody in ICT

In the field of speech therapy, we find tools that use the advantages of speech technologies (mainly automatic speech recognition systems (ASR)) to assist patients that have a speech disorder, in order to evaluate and treat speech and language pathologies (Computer-Aided Speech and Language Therapy or Computer-Aided Voice Therapy for altered voices). A good compilation for Spanish is distributed in the project Comunica, http://dihana.cps.unizar.es/~alborada/herramientas.html, which has a set of tools oriented towards children who need to train their phonatory, articulatory, and descriptive abilities [25]. Within the same research line, reference [26] developed a set of free activities called PreLingua for providing interactive voice therapy to a population of individuals with voice disorders. These tools are designed to train such voice skills as voice production, intensity, blow, vocal onset, phonation time, tone, and vocalic articulation for Spanish. To test the efficiency of the tool, PreLingua was applied in a population with voice disorders and pathologies in special education centers in Spain and Colombia. After 12 weeks of therapy, intensity, blow, and rhythm improved significantly in the users, while correct intonation was harder for the subjects to learn.

For English, reference [27] describes a system for automated speech therapy in childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) that is able to identify the three main types of errors commonly associated with this voice disorder, as follows: Grouping errors (delay in sound production), articulation errors (incorrect pronunciation of phones), and prosodic errors (inconsistent lexical stress). Other studies explore the advantages of transforming prosodic cues (pitch, duration, and intensity) into visual cues to improve expressive reading [28]. These authors carried out an experiment with children and the results suggest that beginner readers could benefit from explicit visual prosodic cues and thus enhance oral reading expressiveness.

From a more general point of view, there are thematic websites oriented towards helping the learner to separate the linguistic effects from the paralinguistic ones (emotions, attitude, etc.) in the prosodic domain, to identify the systematic and categorial aspects, and to recognize the phonological categories of prosody and associate them with the corresponding linguistic meaning [29].

However, the enormous difficulties of intelligibility that are present in the speech of persons with DS cause that the greatest efforts go to the analysis of the segmental level (loss of phonetic segments and simplification of syllables, stuttering or cluttering), leaving aside the relevance of the prosodic level. Our hypothesis is that a better command of prosodic features (accent, intonation, prosodic grouping) will aid in improviing the global quality of disordered voices.

3. Design and Development of the Video Game Experience

3.1. Technological Decisions

3.1.1. Features Motivated by Learner Characteristics

The potential users of the video game are young people with DS, a collective that, although they are digital natives [1], show a series of cognitive, learning, and attentional difficulties that limit the effectiveness of the ICT educational tools. Some of them are a lack of motivation, attention deficit disorder, decreased frustration tolerance, difficulty to process multimodal information, and working memory problems [12,30].

To cope with these limitations, several design decisions have been taken. First, in order to have an interesting plot that motivates the players and encourages their concentration, Pradia: mystery in the city (www.pradia.net) has been conceived as a graphic adventure based in a friendly storytelling style that moves between realistic and fantastic ambiences, as follows: The first settlers of the continent lived in peace with nature thanks to the protection of an ancient amulet that was responsible for maintaining harmony in the city. But suddenly the old amulet disappeared from the town hall, where it had been guarded. Without the amulet, the rains overflowed the rivers, the trees fell, and the animals fled the forest. Only the recovery of the ancient amulet will restore peace and harmony in the city. Will you be the one to get it?

Given the target audience of the game, the user experience should be simple enough not to frustrate his/her ability to play, but attractive enough to maintain his/her attention throughout the game time and his/her desire to play again in successive sessions. This is achieved thanks to the following characteristics:

- □

- The video game provides clear goals and objectives. The cinematic scenes that appear at the beginning and at the end of each episode recall for the player those events that have happened before or anticipate those that will happen soon in the story. This gives a clear vision of how much the player has advanced from the beginning and what he/she must achieve to accomplish his/her missions, therefore ensuring he/she has a reason to play again.

- □

- The adventure shows a clear and continuous progress. A map of the game world places the user in a location and point in time, so that he/she can calculate the path that remains to be traveled to achieve his/her final objective. So it is much easier for the user to recall the story when he/she comes back to the adventure and wants to continue playing.

- □

- The mechanics of the game include desirable rewards, the most important at the end of the adventure, when the player can choose between a set of prizes that crown him/her as a hero/heroine. Getting a prize, even the simple expectation of being able to achieve it, motivates the players to complete the activities in the game.

- □

- The arquitecture of the video game ensures continuity. Given the high degree of optionality in the routes that the player can take to reach the final goal, there are reasons to return to play.

The user interface is designed to be as easy to use as possible, from the perspective of accessibility [31,32]. To aid the understanding of the story, it uses simple scenarios with primary colors. The legibility of the cartoons that appear during the game has also been taken into account according to the European guidelines for developing easy-to-read materials [33]. The control of the game is based on simple actions, the combination of objects, or decision-making between elements shown on the screen. All the operations of the game are based on point and click, a common method in the graphic adventures subgenre of video games, which consists of placing the mouse cursor on different objects or interactive parts of the screen to control the characters and carry out the necessary actions. Thus, only one device is used, with no input from the keyboard. As for the fulfillment of the missions, the player has an inventory where the objects that are obtained and used throughout the adventure are automatically placed. This inventory remains visible all the time in order to facilitate the mechanics of the game.

Together with the reasons explained above —more details about the system architecture can be found in [34], where an earlier version of PRADIA is described—, other considerations have been taken into account when making technological decisions, as follows:

- □

- The PRADIA educational video game is not designed for use as a self-learning resource; instead, the sessions must be carried out with the support of a human assistant, who guides the player throughout the game sessions and who contributes in a personalized way to the quality of the gamer experience.

- □

- The player has a virtual assistant. To preserve as much as possible the playful nature of the application (minimizing external help), a virtual assistant (a talking parrot) stays with the player throughout the adventure. In addition to guiding the player in the achievement of the challenges of the adventure, it offers clues and explanations in any circumstance of error, blocking, or loss of attention. To enhance the fictional nature of the story, and profit from the positive guidance effect reported in [35], the pet has magical characteristics, including that it is endowed with the capacity of language, it knows when the player needs help, and it recognizes the reactions of the other characters and helps the player to interpret them appropriately.

- □

- The user is assisted with visual and auditory reinforcements. To complete the tasks, the player receives instructions from various auditory channels, including the talking parrot, the rest of the non-player characters, or a narrator’s voice. In addition to this, the player is provided with visual clues, such as the icon of a microphone when he/she is required to record an utterance.

- □

- All the actions are reinforced with positive messages of recognition and affirmation. The connection between learning and emotion [36] is specially relevant for individuals with DS, who learn better when they have succeeded in previous activities and when they immediately know the positive results of their activity, they show more interest in continuing to participate in the task [37].

- □

- The errors in the resolution of the activities are conceived as a sign of the state of learning that should allow for complementary pedagogical plans. To avoid the frustration caused by failed attempts in a player with cognitive difficulties and, consequently, to reduce the occurrence of error messages, the game progresses automatically after a certain number of attempts. The player never has to restart the game or repeat any scenario, the game does not finish until the end of the adventure. It is up to the educational agents to plan specific actions to reinforce the most affected content in each of the individuals once the game sessions are over.

- □

- The hero does not have any antagonist and there are no enemies to defeat. The intention is to favor the motivation to solve simple problems in a positive simulated world and to form enriching social relationships.

3.1.2. Features Motivated by Learning Goals

Since Pradia: mystery in the city is a video game developed with the aim of improving oral communication, the following key features characterize it:

- □

- Oral predominance: The voice is the player’s main means of interaction with the game. The player must solve missions that depend on the proper use of prosodic features.

- □

- Inclusion of perception and production fields: The focus of the video game is to enable the learner to communicate effectively in the various situations he/she would be likely to find him/herself and, therefore, it is important to differentiate prosodic meanings according to the purpose pursued as well as to produce the information with the appropiate prosodic features.

- □

- Importance of the quality of the speech in the video game: The voice-over and the voices of non-player characters (most importantly, the voice of the pet that accompanies the player along the adventure) are a part of the game play, creating interactions and enabling the plot to advance while giving instructions and a pronunciation model when needed. Moreover, given that the video game simulates reality, the quality of the voice and the coordination with the action is extremely important. For these reasons, the voices are not synthetic speech, but rather a group of actors and actresses recording the utterances of the different characters.

- □

- Value of the cultural and social context: Pradia: mystery in the city offers different daily scenarios for the practice of communication skills and social relationships and special attention has been devoted to the physical characteristics of the characters by including various ethnical groups and people with functional diversity.

3.2. Design of the Gameplay

The central challenge of integrating video game-based learning in school settings is helping learners make the connections between the knowledge learned in the game and the skills needed outside of school, while maintaining a high level of engagement with game narrative and gameplay. To face this challenge, and in order to not separate the learning process from the game experience, the virtual world simulates the social reality of the players and all the activities are integrated into the narrative script. To advance in the adventure, the hero must communicate with the rest of the non-player characters in varying social contexts, where different tasks that imply the correct use of prosodic features are presented, together with the practice of social skills and psychomotor abilities. The crucial point is that, in the video game, the appearance of each activity depends on the game writing and the storyplot, not on the learning objective pursued.

To cover both fields of speech comprehension and pronunciation, two types of game tasks have been designed, auditory discrimination activities (Section 3.2.1) and spoken oral activities (Section 3.2.2). In the case of production tasks in the video game, the learning contents are conveyed through combined strategies of reading aloud and resolution of various speech situations, which have a decisive impact on the process of social inclusion, as is the case of linguistic politeness. Both resources favor the cognitive, linguistic, emotional, and social development of people with DS and, consequently, their communicative competence.

The learning game materials are designed to address the specific needs of persons with SD in the domain of prosody but, in order to enhance playability, enjoyable and fun activities are also found along the adventure (Section 3.2.3).

3.2.1. Prosody Perception Tasks

Perception activities exercise discrimination based uniquely on prosodic differences. To improve the identification and interpretation of prosodic structures, the video game includes, throughout the adventure and in an integrated way in the narrative script, activities of auditory discrimination between minimum pairs (two sentences that coincide in all the phonemes and only differ in a suprasegmental category). These kinds of activities must be completed by selecting one of the two utterances that appear written in two boxes, of which only one is appropriate in the context. A voice-over reproduces each of the utterances and if the player needs to hear them again, he/she can click on the box the number of times he/she needs. Given the varied cognitive profile of people with DS, users hear the statements as many times as they need before deciding and, in case they fail, the talking parrot offers successive clues to select the correct answer. Some examples of these activities are presented in Section 3.3.

The success in the resolution of perception activities is evaluated automatically by the system and the player obtains a feedback that tells him if he/she is acting correctly.

3.2.2. Prosody Production Tasks

In production activities, the player practices the nuances and meanings of prosody with his/her own voice through reading, imitation, or guided production of the utterances. The player faces obstacles whose resolution depends on the pronunciation of the communicatively appropriate prosodic structures in the context. The differences in the tasks enrich the linguistic and cognitive skills trained in the video game, as follows:

- □

- Reading task: At the beginning of the activity, the virtual assistant introduces the activity to relate it to the conversation in progress. Later, the voice-over plays the sentence to be recorded. The player must record the sentence shown on the screen to continue the conversation with the character. The trainer must decide if the player has pronounced the sentence correctly or not. If the recording is correct, the game will show a positive feedback on the screen. If it is incorrect, the player can repeat the recording a certain number of times (2 or 3 times, depending on the activity). At the end, if the player cannot succeed, the game continues in order to avoid frustration.

- □

- Imitation task: The player hears the audio of the utterance but does not have the text on the screen. It is the talking parrot or the voice-over who offers a model of pronunciation of the utterance.

- □

- Elicited speech production task: There is neither a written text nor a spoken model; instead, the instructions of the talking parrot or the development of the game itself guide the player in the production of the target utterance.

- □

- Spontaneous speech production task: No instruction is given about the production, an open question is formulated or a requirement to express some linguistic emotion is present.

Success in the resolution of the production activities is judged by the professional that accompanies the player. In production activities, given the variability in the pronunciation of an utterance (with more or less intelligibility, speed, intensity, number of breaks, etc.) and the phonetic limitations of the speech of people with DS, the automatic systems are not reliable and it is necessary for a human to assess the degree of success of the response. Nevertheless, in order to preserve the ludic component, the evaluation is done using a different keyboard than the one used for the video game, so the judgments go unnoticed by the player. In the same way as in the activities of perception, the player hears a message from the video game itself that tells him/her to what extent he/she has achieved the objective of the challenge.

3.2.3. Mini-Games

Throughout the adventure, varied contents in puzzles and mini-games are included to enhance playability and to achieve an immersive game environment, that is, a story that makes the player want to be part of it and whose progression depends directly on the decisions they make. These mini-games help in the acquisition of implicit learning in such areas as psychomotor skills or the development of logical relationships.

3.3. Learning Goals

The content that the game conveys for its explicit learning is framed within the theory of intonational phonology [38], which considers the difference between linguistic and paralinguistic categories in the prosodic level. In accordance with this, we assume the existence of prosodic categories —prominence, phrasing, or organization of utterances in prosodic groups and intonation— that can be modified in their phonetic realization, depending on paralinguistic indices.

The following four action lines are described in Table 1: Prominence or levels of stress, phrasing or possibilities of division of the statements into smaller groups, and intonation, particularly the classification in sentence modalities. Regarding paralinguistic indices, the linguistic expression of politeness has been chosen due to its direct influence on the regulation of social events. All the categories are trained in speech comprehension and production (Table 2) according to the needs of the population of persons with DS, as detailed in the following sections.

Table 1.

Definitions of the prosodic concepts used in the educational project.

Table 2.

Learning goals of the video game.

The learning content is grounded in what is known about Spanish intonational phonology [29,39,40] and the prosodic deficiencies of persons with DS [13,16,17], combined with the conclusions drawn from the analysis of the following two databases collected during the research: a) First versions of the video game were used for recording a speech corpus of people with intellectual disabilities [41]; and b) an experimental corpus designed to address specific prosodic problems has been recorded with individuals affected by DS and with speakers of reference [42].

3.3.1. Prominence

In autosegmental–metrical terms, if a syllable has a certain level of prominence on the metrical tier (that is, stress in Spanish), we expect to find a pitch-accent on the autosegmental tier, while if the word belongs to the unstressed class, no pitch-accent is expected [38]. In Spanish, word-level stress and pitch-accent normally occur concurrently. In pragmatically neutral sentences, all stressed syllables will typically be pitch-accented, whereas unstressed syllables are not.

In contrast to this generalization, the utterances of persons with DS frequently show the upgrading of unstressed syllables to accented syllables and, as a consequence, their speech sounds overaccented. A stress addition involves adding prominence to syllables that are not lexically marked for it. To revert this tendency, the video game includes dynamics to train the auditive discrimination between different prominence patterns, as shown in (1) below, and to practice the pronunciation of words with different levels of stress, as shown in (2) below.

(1)

[Type of dynamics: Perception task: auditory discrimination between two utterances.]

[setting] supermarket

[goal] search for an object necessary for the adventure

[non-player character: shop assistant] ¿En qué puedo ayudarte? [How can I help you?]

[elicitation task: The player must answer the question with his/her own words] Necesito una escalera [expected answer: I need a ladder.].

[non-player character: shop assistant] Puedo ofrecerte una escalera de cuerda o una escalera de hierro [I can offer you a rope ladder or an iron ladder.]

[voice-over] Tienes que responder eligiendo una de estas dos opciones. [You have to answer by choosing one of these two options]

a) Necesito una escalera de cuerda. [I need a rope ladder]

b) Necesito una escalera de CUERDA. [I need a ROPE ladder]

As explained in Section 3.2.1, the activity must be completed by selecting one of these two utterances that are written in two boxes. The player hears the utterances as many times as they need before deciding and then he/she selects the appropiate utterance in the context. The adventure goes on from activity (1) to activity (2), in which the player has to reproduce the effect of prominence on a lexical word with his/her own voice.

(2)

[Type of dynamics: Production task: reading.]

[setting] supermarket

[goal] search for an object necessary for the adventure

[non-player character: shop assistant] Pero el hierro es más fuerte ¿te doy la escalera de hierro? [But iron is stronger, shall I give you the iron ladder instead of the rope one?]

[reading task: The player must read the sentence that appears on the screen] No, no, la de CUERDA. [No, no, the ROPE ladder.]

3.3.2. Phrasing

As a rule, in Spanish, any pause or break juncture can appear inside a prosodic word or between prosodic words, and the first possible location for a pause or a tonal marking is found at the end of an intermediate phrase (ip or minor group) [29,43].

However, in the speech of persons with DS, the occurrence of pauses in wrong places and the prosodic marking of initial edges at the IP/ip domain (major and minor groups) are frequently found, two limitations that lead to a disfluent and overemphasized speech when combined [17]. To train the identification of the right boundaries between words and prosodic groups, the video game includes discrimination activities that show two sentences that coincide in all the phonemes, but differ in prosodic organization (the minimal pair procedure), as shown in (3).

(3)

[Type of dynamics: Perception task: auditory discrimination between two utterances.]

[goal] search for an object necessary for the adventure

[non-player character: shop assistant] La escalera de cuerda vale cinco euros. [The rope ladder costs five euros.]

[voice-over] Tienes que responder eligiendo una de estas dos opciones. [You have to answer by choosing one of these two options]

a. Sí, necesito una, la compraré. [Yes, I need one, I'll buy it.]

b. Si necesito una, la compraré. [If I need one, I'll buy it.]

Production activities cover the right production of different prosodic organizations, from one to three prosodic groups integrated by a variable number of syllables and combined with different sentence modalities. The example in (4) illustrates a reading task. At the beginning of the activity, the virtual assistant introduces the activity, relating it to the story in progress. Later, the voice-over plays the sentence to be recorded. The player must record the sentence shown on the screen to continue the interaction with the non-player character. The trainer must decide if the player has produced the sentence correctly or incorrectly (see Section 3.3.3). If the recording is correct, the game will show a positive feedback on the screen. If it is incorrect, the player can repeat the recording a certain number of times (two or three times, depending on the activity). If the player cannot make the recording correctly, the game goes on.

(4)

[Type of dynamics: Production task: reading]

[setting] Town hall

[goal] to talk with the mayor to obtain information about the current location of the magical stone

[non-player character: security guard] ¿En qué puedo ayudarte? [How can I help you?]

[reading task: The player must read with the correct fluidity the sentence written in the box.] Soy quien busca la piedra mágica. Necesito ver al alcalde. [I am the one who is looking for the magic stone. I need to see the mayor.]

3.3.3. Intonation

Intonation is used to carry a variety of information, ranging from grammatical structure, information structure, discourse function, or attitudes. Individuals with DS show difficulties when producing and understanding questions, signaling turn-taking, or keeping to topics in conversation [13,15], and abnormal suprasegmental characteristics, regarding rate of speech, stress, loudness, pitch, and quality of voice have all been reported [44]. In the design of the video game, special emphasis is given to the proper meaning-form mapping in the use of sentence modalities. We have assumed the description of the Spanish intonation forms in [45], including neutral statements (Necesito ver al alcalde, I need to see the mayor), biased statements expressing uncertainty (Es que no sé dónde está el amuleto… I do not know where the amulet is...), exclamative statements expressing desire (¡Ojalá pudieras venir conmigo! I wish you could come with me!), and the basic emotions of surprise (¡Hala, esa puerta no estaba aquí antes! Wow, that door wasn’t here before!), happiness (¡Ya vuelvo a casa! I'm going back home!), anger (¡Qué rabia! What anger!), and sadness (¡Qué triste es estar solo en este bosque! How sad it is to be alone in this forest!); yes-no questions (¿Sabes dónde vive la señora Luna? Do you know where Mrs. Luna lives?), wh-questions (¿Cuánto vale? How much does it cost?); and commands (Ábrete, puerta, y que brille la piedra. Open, door, and let the stone shine.).

The training of the perception of intonation patterns is based, as in the case of prominence and phrasing, on the selection between two utterances in which only the sentence modality is changed, as shown in (5).

(5)

[Type of dynamics: Perception task: auditory discrimination between two utterances]

[setting] bus station

[goal] to find the right number of bus that leads to a friend’s house

[non-player character: bus driver] ¡Buenos d´ıas! [Good morning!]

[voice-over] Tienes que responder eligiendo una de estas dos opciones. [You have to answer by choosing one of these two options]

¡Buenos d´ıas! Este es el autobu´ s 52. [Good morning! This is the bus 52.]

¡Buenos d´ıas! ¿Este es el autobu´ s 52? [Good morning! Is this the bus 52?]

As production is concerned, the field of expression of emotions by means of the right selection of melodic variation is particularly interesting because it establishes clear links between prosody and pragmatics, in addition to contributing to a better development of emotional competence [20]. Previous research has demonstrated that the ability of individuals with DS to express themselves through spoken language is more impaired than are the nonverbal cognitive skills [15,30,46]. In the video game, production tasks based on imitative pronunciation, such as (6), help to model the basic emotions of surprise, happiness, anger and sadness.

(6)

[Type of dynamics: Production task: imitative pronunciation]

[setting] the magic forest

[goal] the player has to find the entrance door to the lost temple

[imitation task: The voice-over reads aloud the utterance and the player must reproduce it with the same intonation patterns] ¡Hala, esa puerta no estaba aquí antes! [Wow, that door was not here before!]

3.3.4. Linguistic Expression of Politeness

Verbal politeness is essential to achieving effective communication, the main aim of the video game. According to [47], we understand linguistic politeness as forms of behaviour that establish and maintain commitment in any social interaction. Reference [48] reported that, although individuals with DS are able to produce a number of speech acts, such as request, suggest, or acknowledge, like non-intellectually impaired people, they do so with simpler linguistic means and not always using the indirect polite forms that normal people find appropriate. To practice this, in both fields of speech comprehension and production, the video game includes verbal actions that support politeness, including polite offers and requests, as shown in (7) and (8), together with greetings and farewells, thanks, and congratulations.

(7)

[Type of dynamics: Perception task: auditory discrimination between two utterances]

[setting] home environment

[goal] to socialize with others

[non-player character: old lady with a peaceful character]

[talking parrot] Si tuvieras hambre y quisieras que te ofrecieran galletas, ¿qué frase tendría que decirte la señora? [If you were hungry and you wanted to be offered cookies, what sentence would the lady have to say to you?]

a. Unas galletas [Some cookies.]

b. ¿Unas galletas? [Some cookies?]

(8)

[Type of dynamics: Production task: imitative pronunciation]

[setting] trip to a mountain by cable car

[goal] to buy a ticket to get on the cable car that will take the player to the mayor's house

[talking parrot] Puedes decirlo de muchas maneras: por ejemplo, ¿Me da un billete, por favor? [You can say it in many ways: for example, can you give me a ticket, please?]

4. Evaluation of the Educational Resource

Evaluation of the educational resource has been conducted in two areas, namely establishing the extent to which the video game met user satisfaction (Section 4.1) and observing the degree of achievement of the learning goals (Section 4.2).

4.1. Methodology

4.1.1. Speakers

The study sample consisted of 10 young adults with DS with an age range between 14.83 and 18.58 years. Half of them were recruited from DownCatalunya, a local Down Syndrome Foundation located in Barcelona (Spain) and the other half from Aura Foundation, a non-profit organization located in Barcelona (Spain) that aims to improve the quality of life of people with intellectual disabilities by helping to integrate them into society and find them employment. In order to obtain measures of verbal and cognitive development levels, all participants were administered with the receptive vocabulary tests in Peabody images and the Raven Progressive Matrices evaluation battery. The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Scale-III [49] was used to assess verbal mental age and Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices [50] served as a means to measure the non-verbal cognitive level. According to the Peabody test, the verbal mental age of the participants ranged between 5 and 8.25, with an average of 6.58 years. On the other hand, the direct scores of the Raven test were used to estimate the level of nonverbal cognitive development. These scores ranged from 10 to 22, with an average of 15.70. The range of scores observed at both the verbal and non-verbal cognitive levels is consistent with that usually found in people with DS [51,52], from which it follows that, despite the small sample size, the group of study participants was representative.

4.1.2. Experimental Setup

Each participant played with the Pradia video game for a total duration of 4 hours, distributed in 4 sessions of 1 hour per week. The participants were supported by a speech and language therapist who knew them in advance and was an expert at working with individuals with DS.

Previous to the sessions, the two therapists were provided with a rapport that defines the optimal conditions for the development of the game sessions and their own role along the game time [53]. The main function of the therapist is to explain the game, to help participants when needed, and to encourage them to continue with the activities. Due to the learner characteristics, it is especially important to reduce their frustration when they are not able to solve an enigma or complete a task. To avoid abandonment, apart from the practical help needed to understand instructions or to finish an activity, an emotional involvement is essential to reach a positive outcome.

Importantly, the therapist took notes about how each session developed, reporting the attitude of the player and any problem that could occur during the game time. In particular, she observed the level of motivation and the degree of autonomy of each of the speakers during each of the sessions. These data are one of the source data used to evaluate the educational resource. The second one concerns the perception of the players about the experience of the game. Once the game sessions were finished, the players received a questionnaire to fill in with questions about their feelings during the game experience, as follows:

- —

- Have you played video games before?

- —

- Did you like to play this video game?

- —

- Would you like to play it again?

- —

- Did you like the adventure?

- —

- Did you like to have a pet in the adventure?

- —

- Did you like to communicate with the characters of the adventure?

As a third source of data, the results obtained by each speaker in each activity were processed with the assessment tool described in [54]. Following the educational perspective that focuses on the need of evaluation for enhancing learning [55], leaving aside the evaluation of learning, we are interested in analyzing the degree of success in each of the activities included in the game associated with the prosodic and pragmatic categories defined as learning goals in Section 3.2. To obtain this information, the Test of Prosodic Skills of Pradia (THAP-PRADIA) was used. The exportation of the data and its processing allows us to obtain reports of results with different levels of detail. The scores can be grouped according to the learning objectives pursued by the video game, or a report can be extracted for each of the dynamics of the game. The organization of the results from the most general to the more particular allows us to obtain a global assessment of the communicative performance and the prosodic skills of the user, throughout the game time, and, at the same time, to observe the most significant shortcomings in order to propose new teaching strategies.

This experimental setup gives us different kinds of qualitative and quantitative information so as to achieve a more complete vision of the phenomenon under study, reflecting its complexity.

4.2. Results: Evaluation of the Motivation

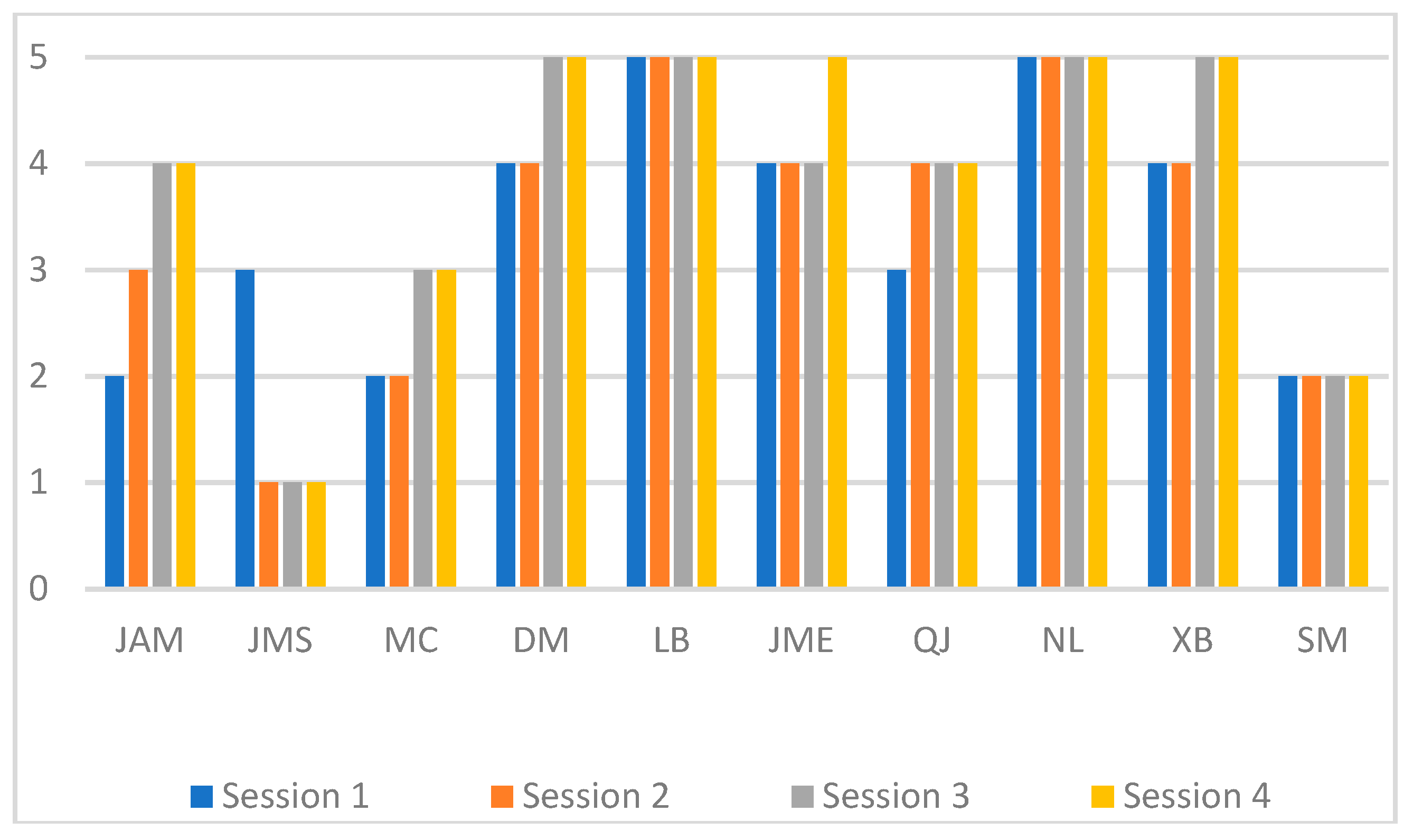

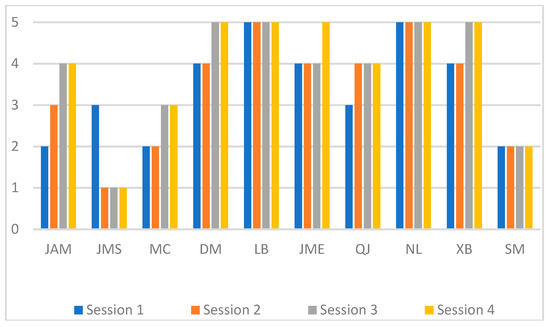

In the current state of research in serious games, the potential of video games to improve motivation and commitment in education is broadly accepted, but there is no data on their usability in the group of people with DS, who generally have low tolerance to frustration and a lack of motivation, as compared to the non-impaired population. To gather data about this, the reports of the therapists about the level of motivation were converted to a 1–5 scale, where 4–5 stand for a high level of motivation, 3 for an intermediate level, and 2–1 for a low level.

Figure 1 depicts the data for each session of each player. It can be observed that the individual variability is very high, since some players show a high level of motivation from the first session to the last (DM, LB, JME, NL, XB), whereas others did not find the game sufficiently attractive in any of the sessions (SM) or their interest dropped after the first session (JMS). These cases with a low degree of motivation coincided with the reports of the therapists about behavioural problems; the user was tired, upset, felt sick, etc. Interestingly, the degree of motivation of some of the players (JAM, QJ) increased as sessions were repeated.

Figure 1.

Indicators of degree of motivation (4–5: High; 3: Intermediate; 2–1: Low) for each session of each player.

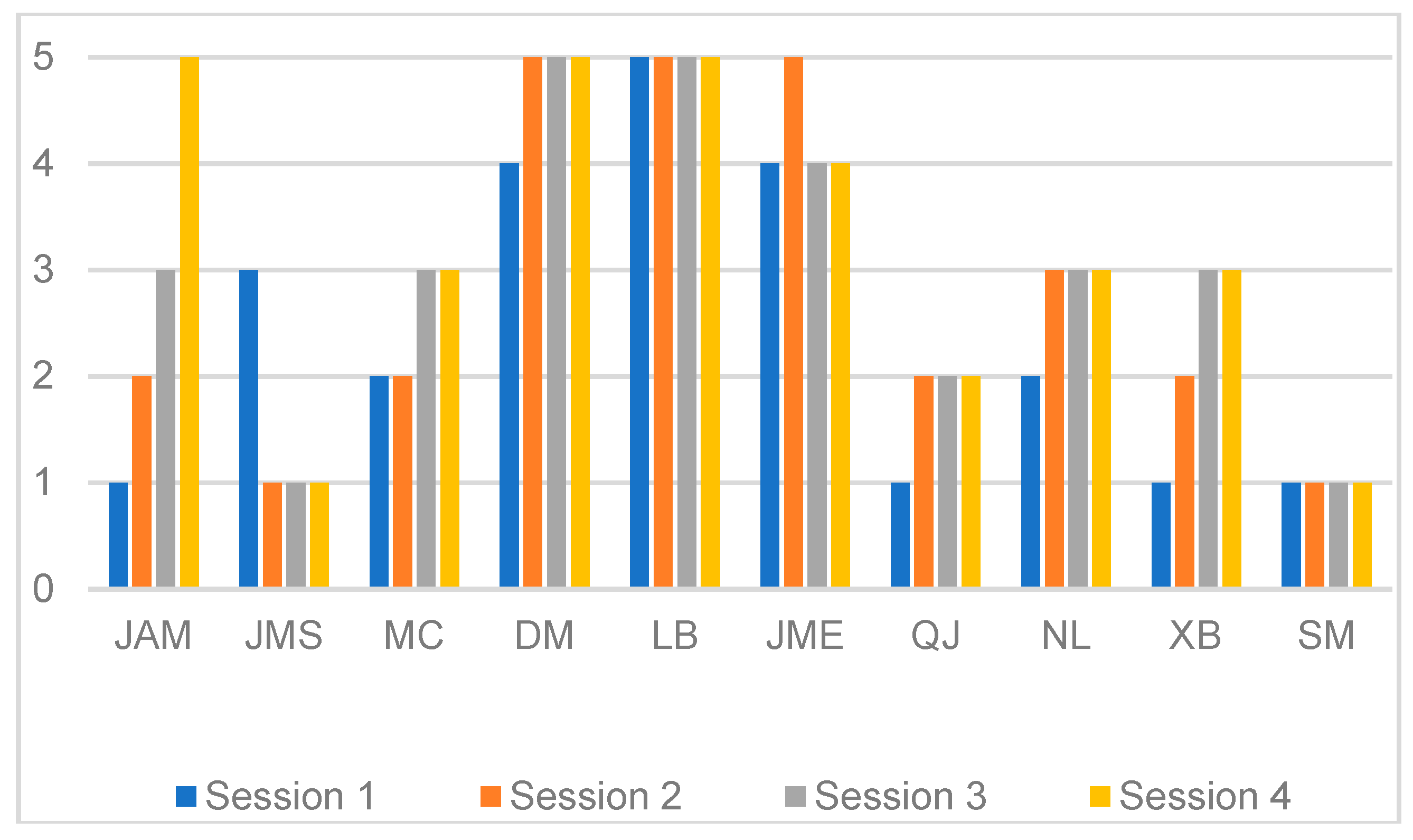

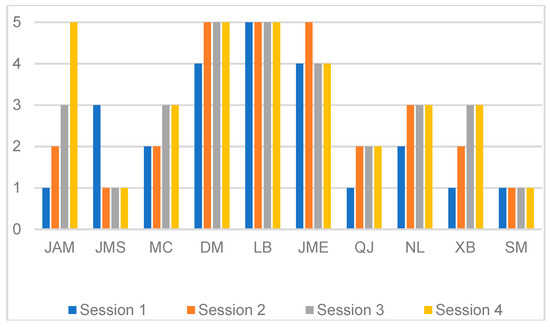

Although the autonomy is not the final objective of the video game, since it is not a self-learning resource (as explained in Section 3.3.3), data about this feature were also gathered to observe if it was related with motivation. If we compare the less motivated players in Figure 1 and Figure 2, we can observe that the lack of autonomy negatively affects how motivated the player is. In these cases, moreover, the therapists reported difficulties in understanding the instructions of the game and the development of the adventure and the feeling that the video game was a time-consuming activity.

Figure 2.

Indicators of degree of autonomy (4–5: High; 3: Intermediate; 2–1: Low ) for each session of each player.

The opinions gathered from the group of players by means of the questionnaire support the idea that, in general, they feel motivated to play. Eight out of ten players enjoyed playing the game and would like to play it again in the future. They also liked the story and the parrot as companion. One of the players (SM) reported a negative opinion, saying that this was not a recreational activity, but a school task, probably because he showed difficulties in understanding the thread of the story and to follow the instructions. Despite this, all the players liked interacting with the characters of the video game.

4.3. Results: Evaluation for Enhancing Learning

The Test of Prosodic Skills of Pradia (THAP-Pradia) has been developed as a complementary tool of the Pradia video game to offer educators a way to monitor the progress of each person separately and to give students information about their own learning process [54]. This is crucial in the perspective of applying evaluation to enhance learning for SEN students [55,56], in which both educators’ and students’ perspectives are considered. As for educators, by pointing out the specific shortcomings of each of the players, the evaluation allows work to be done, specifically, on those competences in which the individual with DS has achieved less success. As for students, the simplified graphs showing their strengths and weaknesses motivate them to continue the training.

The THAP-PRADIA is based on associating each of the activities with the learning contents, so that at the end of the game a report is made with a quantitative score assigned to each area. For the purpose of this study, only those results obtained by the participants in the areas related to prosody are shown—more details about the evaluation system of the game in connection to learning objectives can be found in Reference [54]. The scores are representative of four evaluation headings, as follows:

- 10.00–9.00: Excellent command of the required competences;

- 8.99–7.00: Good command of the required competences;

- 6.99–5.00: Sufficient command of the required competences;

- 4.99–1.00: Poor command of the required competences.

The results in Table 3 show a high degree of variability, with speakers that have difficulties achieving the level of sufficient command of the required competences, moving around 5, and other speakers with a good command of the prosodic skills, with scores above 8. The speakers with the worst results show great difficulties in prominence and phrasing (a common deficit in speech with SD, as documented by [13]).

Table 3.

Scores obtained by each of the players in communicative skills related to prosody and in the domains of speech comprehension and production.

In accordance with what was found in [16], the results in general are better in the tasks of auditory discrimination of prosodic structures than in the tasks of oral expression of prosodic structures, except for two speakers, indicating once again the interspeaker variability.

The speakers’ voice heterogeneity in the collective of individuals with DS is due to the variability in their cognitive and linguistic skills, and this heterogeneity has proved to be the main obstacle in the introduction of a module for the automatic evaluation of prosody into the video game [57]. For this reason, the identification of the most affected areas must serve educators to propose additional activities, external to the video game, that reinforce the benefits of the educational intervention. Although it is necessary, in any field of education, to consolidate the knowledge through the use of reinforcement and generalization activities, in the case of students with specific educational support needs derived from disability, these activities outside the video game are even more important. We think that the concept of an educational video game as an ecosystem, that is, as a community of characters whose vital processes are related to each other and developed according to environmental factors, allows educators to design a project that combines the intrinsic advantages of the game with the ease of planning transversal activities (before and after the use of the digital tool), a concept that combines well with the methodology of project-based learning and the principle of learning-by-doing [58,59].

5. Discussion

The low oral communication proficiency of individuals with DS is an important barrier to their social integration. They generally present serious limitations in their language skills, with better speech comprehension than production. In some cases, their speech is almost unintelligible and they have difficulties understanding and producing indirect speech, such as polite offers or questions [12,13,15,17]. To this respect, some authors have defended language therapy targeting the practice of expressive language as a method to increase communicative effectiveness [60]. The study in [61] adds weight to the argument that it is important to train prosody so as to gain quality in the speech of people with DS and the tool Pradia is a step forward in this line. The study in [61] has also shown the importance of intonation and rhythm in the automatic identification of a voice, as pertaining to individuals with DS. In this study, a perception test was performed using samples where the prosody of utterances from a group of typically developing individuals was transferred to the utterances of a group of individuals with DS. The results of the test showed the high importance of the prosodic variables of frequency, energy, and temporal domains to identify a voice as atypical speech, even though the voice quality is not modified. Nevertheless, as shown by [26], intonation is hard to train in a population with voice disorders.

With the growth in popularity of video games in our society, a good strategy is to incorporate gaming elements into the training process, as in the case of Pradia. Nevertheless, although the general characteristics of video games facilitate the dynamics of the educational process, we cannot omit the importance of planning a whole pedagogical project that includes the delimitation of learning goals and the profile of the addressees, conditions of application of the educational project, and methodologies of evaluation of learning progress.

Defining learner characteristics is the first step towards a conceptual research framework. The way in which a user communicates with a technological solution, in this case a video game, must be considered in the design of the tool in order to gain efficiency and acceptability. That is why it is important to define the potential audience to whom the video game is aimed. This decision conditions the rest of the educational project in a meaningful way, not only because of the content it includes and the kind of competences that must be achieved throughout the process, but also because of the cognitive scheme on which the video game is based.

The second crucial aspect to deal with is to go from content to game and answer the question of how the prosodic concepts are transformed into a gamified perspective. To do this, a catalogue of categories serves as a baseline to design the elements of a video game, such as the game play rules and the narrative structures, with the final goal of training oral expression in a natural way and from a communicative approach. We have adopted the strategy of incorporating the learning content into the missions and challenges that the player must solve throughout the adventure. The correct use of the nuances of expression is what enables the player to find an object, obtain information, etc., so he/she can continue advancing in the story.

Since the global learning goal of the video game is oral expression, going beyond text is a must that has been accomplished by using voice as the main element of user interface. The player hears the voice-over instructions and the pet's messages, which provide assistance and advice, deciding between options in the speech comprehension activities and recording his/her own voice in the production tasks. Moreover, the video game records all the responses.

Finally, for a correct validation of learning progress, the establishment of evaluation methods is necessary. In video games aimed at students with SED, the approach of evaluation learning moves to the question of how educators can enhance learning processes. From this perspective, on the one hand, the results of the motivation test have certified that the strategy of the video game provides students with emotional comfort and pleasure, so the video game has proven to be useful in encouraging the users to exercise their voice. On the other hand, the indicators of the degree of achievement of the competences required serve to identify the most affected prosodic skills and to elaborate a personal training program to improve them.

6. Conclusions

The video game Pradia: misterio en la ciudad is an educational resource set within a Design-based research (DBR) methodology in which all the phases of conceptualization, design and evaluation are equally relevant and interact with each other. This study aims to offer professionals and educators not only a new tool, but also orientation on how to draw up and implement a pedagogical plan that includes this tool. Moreover, this work is a good example of how prosodic knowledge can be applied and used in the field of teaching oral communication with a video game-based learning approach. The competences trained in the game include the main aspects of prosody (intonation, phrasing, and prominence), and additionally, it helps with learning politeness.

The video game-based learning approach is particularly suitable for students with special needs given that the video game, thanks to its particular characteristics, enhances the learning of soft skills (psychomotor skills, logical thinking, conceptual relationships, etc.), while multimediality (sound, image, text) offers the most appropriate solution for practising prosody, as it allows the incorporation of audio files to capture the differences between pronunciations (to train in speech comprehension) and to record the utterances of the players (to practice the melodic variations). The video game is a complete tool that is freely available for therapists, families, and educational centres for facilitating open education (http://pradia.net).

Funding

The experiments described in this work were funded by BBVA Foundation (2015-2017) in the framework of the project PRADIA: Pragmatics and prosody: the graphic adventure game. The research continues in the project funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades and the European Regional Development Fund FEDER (TIN2017-88858-C2-1-R, 1/2018-12/2020) and in the project funded by Junta de Castilla y León (VA050G18).

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my acknowledgements to all of those with whom I have worked during this project: David Escudero-Mancebo, Valentín Cardeñoso-Payo, Mario Corrales-Astorgano, Pastora Martínez-Castilla, Ferran Adell, Yurena M. Gutiérrez-González. Mario Corrales-Astorgano was responsible for the technical implementation of the video game and Patricia Sinobas for the design of the scenarios.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, J.P. What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Comput. Entertain. 2003, 1, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberría, F. Videojuegos y educación. Comunicar 1998, 10, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, B. Videojuegos y Aprendizaje; Graó: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wuang, Y.P.; Chiang, C.S.; Su, C.Y.; Wang, C.C. Effectiveness of virtual reality using Wii gaming technology in children with Down syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girard, C.; Ecalle, J.; Magnan, A. Serious games as new educational tools: How effective are they? A meta-analysis of recent studies. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2013, 29, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granic, I.; Lobel, A.; Engels, R.C. The benefits of playing video games. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fromme, J.; Unger, A. Computer Games and Digital Game Cultures: An Introduction. In Computer Games and New Media Cultures: A Handbook of Digital Games Studies; Fromme, J., Unger, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vandercruysse, S.; Vandewaetere, M.; Clarebout, G. Game-based learning: A review on the effectiveness of educational games. In Handbook of Research on Serious Games as Educational, Business and Research Tools; IGI Global: Harrisburg, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 628–647. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Hannafin, M.J. Design-based research and technology-enhanced learning environments. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2005, 53, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Benito Crosetti, B.; Ibáñez, J.M.S. La investigación basada en diseño en Tecnología Educativa. Rev. Interuniv. Investig. Tecnol. Educ. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.E.; Klusek, J.; Estigarribia, B.; Roberts, J.E. Language characteristics of individuals with Down syndrome. Top. Lang. Disord. 2009, 29, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, R.D.; Vorperian, H.K. Speech impairment in Down syndrome: A review. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2013, 56, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, J.; Pulsifer, M.; Seligsohn, K.; Skotko, B.; Schwartz, A. Down syndrome: Cognitive and behavioral functioning across the lifespan. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2015, 169, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.; Næss, K.A.B.; Jarrold, C. Assessing pragmatic communication in children with Down syndrome. J. Commun. Disord. 2017, 68, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanovik, V. Prosodic deficits in children with Down syndrome. J. Neurolinguist. 2011, 24, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heselwood, B.; Bray, M.; Crookston, I. Juncture, rhythm and planning in the speech of an adult with Down’s syndrome. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 1995, 9, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adell, F.; Aguilar, L.; Corrales-Astorgano, M.; Escudero-Mancebo, D. Proceso de innovación educativa en educación especial: Enseñanza de la prosodia con fines comunicativos con el apoyo de un videojuego educativo. In Proceedings of the 1st Congreso Internacional en Humanidades Digitales, Valladolid, Spain, 17–19 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cruttenden, A. Intonation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barth-Weingarten, D.; Dehé, N.; Wichmann, A. Where Prosody Meets Pragmatics; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. Cross-Cultural Pragmatic Failure, 1983. Rpt. In World Englishes: Critical Concepts in Linguistics; Bolton, K., Kachru, B.B., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2006; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Hymes, D.H. On communicative competence. In Sociolinguistics: Selected Readings; Pride, J.B., Holmes, J., Eds.; Penguin: Harmondsworth, UK, 1972; pp. 269–293. [Google Scholar]

- Tangarife-Chalarca, D.; Blanco-Palencia, S.M.; Díaz-Cabrera, G.M. Tecnologías y metodologías aplicadas en la enseñanza de la lectoescritura a personas con síndrome de Down. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2016, 29, 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- González, J.L.; Cabrera, M.; Gutiérrez, F.L. Diseño de Videojuegos aplicados a la Educación Especial. In Actas del VIII Congreso Internacional de Interacción Persona Ordenador (INTERACCIÓN 2007); Macías Iglesias, J.A., Ed.; Dialnet: Logroño, Spain, 2007; pp. 35–44. Available online: http://aipo. es/articulos/1/12410.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Saz, O.; Yin, S.C.; Lleida, E.; Rose, R.; Vaquero, C.; Rodríguez, W.R. Tools and technologies for computer-aided speech and language therapy. Speech Commun. 2009, 51, 948–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, W.R.; Saz, O.; Lleida, E. A prelingual tool for the education of altered voices. Speech Commun. 2012, 54, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M.; Ahmed, B.; Parnandi, A.; Karappa, V.; McKechnie, J.; Ballard, K.J.; Gutierrez-Osuna, R. Tabby Talks: An automated tool for the assessment of childhood apraxia of speech. Speech Commun. 2015, 70, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, L.; de-la-Mota, C.; Prieto, P. Guía Multimedia de la Prosodia del Español. 2009–2014. Available online: http://prado.uab.cat/guia/es/ (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Patel, R.; Kember, H.; Natale, S. Feasibility of augmenting text with visual prosodic cues to enhance oral reading. Speech Commun. 2014, 65, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R.; Hesketh, L. Language, cognition, and short-term memory in individuals with down syndrome. Syndr. Res. Pract. 2001, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ponce, F.J. Accesibilidad, Educación y Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación, CNIC-MEC. 2007. Available online: http://ares.cnice.mec.es/informes/17/contenido/indice.htm (accessed on 26 April 2019).

- Tercedor, M. Materiales Multimedia Para Todos. Inclusión y Accesibilidad en Educación; Tragacanto: Granada, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, M.; Nielsen, G.S.; Tronbacke, B. Guidelines for easy-to-read materials. IFLA Prof. Rep. 2010, 120, 1. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ferreras, C.; Escudero-Mancebo, D.; Corrales-Astorgano, M.; Aguilar-Cuevas, L.; Flores-Lucas, V. Engaging Adolescents with Down Syndrome in an Educational Video Game. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2017, 33, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R.; Mayer, R.E. Role of guidance, reflection, and interactivity in an agent-based multimedia game. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T. Learning and Emotion: Perspectives for Theory and Research. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 9, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, G. What General Educators Have To Say About Successfully Including Students With Down Syndrome in Their Classes. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2001, 16, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, D.R. Intonational Phonology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa, J.M. La Entonación del Español: Su Estructura Fónica, Variabilidad y Dialectología; Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hualde, J.I.; Prieto, P. Intonational variation in spanish: Euro- pean and american varieties. In Intonational in Romance; Frota, S., Prieto, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 350–391. [Google Scholar]

- Corrales-Astorgano, M.; Escudero-Mancebo, D.; Gutiérrez-González, Y.; Flores-Lucas, V.; González-Ferreras, C.G.; Cardeñoso-Payo, V. On the use of a serious game for recording a speech corpus of people with intellectual disabilities. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2016), Portorož, Slovenia, 23–28 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Corrales-Astorgano, M.; Escudero-Mancebo, D.; González-Ferreras, C. Acoustic analysis of anomalous use of prosodic features in a corpus of people with intellectual disability. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Speech and Language Technologies for Iberian Languages, Lisbon, Portugal, 23–25 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nespor, M.; Vogel, I. Prosodic Phonology: With a New Foreword; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2007; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg, L.D.; Widder, C.J. Speech and prosody characteristics of adults with mental retardation. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 1990, 33, 627–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAE-ASALE (La Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española). Nueva Gramática Básica de la Lengua Española; Espasa: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Abbeduto, L.; Pavetto, M.; Kesin, E.; Weissman, M.; Karadottir, S.; O’Brien, A.; Cawthon, S. The linguistic and cognitive profile of Down syndrome: Evidence from a comparison with fragile X syndrome. Syndr. Res. Pract. 2001, 7, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, G. Principles of Pragmatics; Longman: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Rondal, J.; Comblain, A. Language in adults with Down syndrome. Syndr. Res. Pract. 1996, 4, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.; Dunn, L.; Arribas, D. Test de Vocabulario en Imágenes Peabody; TEA: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, J.; Raven, J.C.; Court, J. Test de Matrices Progresivas: Manual/Manual for Raven’s Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales, Number 159.9. 072; J C Raven Ltd.: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, R.S.; Hesketh, L. The behavioral phenotype of Down syndrome. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2000, 6, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, E. Evaluación de la capacidad intelectual en personas con síndrome de Down. Rev. Sindr. 2001, 21, 134–149. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, L.; Adell, F. Guía Pedagógica y Manual de Juego del Videojuego Educativo Pradia: Misterio en la Ciudad. Available online: www.pradia.net (accessed on 26 April 2019).

- Aguilar, L.; Adell, F. Instrumento de evaluación de un videojuego educativo facilitador del aprendizaje de habilidades prosódicas y comunicativas. Rev. Educ. Distancia. 2018, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadfoot, P.; Daugherty, R.; Gardner, J.; Harlen, W.; James, M.; Stobart, G. Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles: Research-Based Principles to Guide Classroom Practice; Assessment Reform Group-ARG: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, A.; D’Alessio, S. Assessment for learning and pupils with special educational needs. A discussion of the findings emerging from the Assessment in Inclusive Settings project. Ric. J. 2009, 1, 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Corrales-Astorgano, M.; Martínez-Castilla, P.; Escudero-Mancebo, D.; Aguilar, L.; González-Ferreras, C.; Cardeñoso-Payo, V. Automatic Assessment of Prosodic Quality in Down Syndrome: Analysis of the Impact of Speaker Heterogeneity. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajcik, J.S.; Blumenfeld, P. Project-based learning. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences; Sawyer, R.K., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 317–334. [Google Scholar]

- Schunk, D.H. Learning Theories an Educational Perspective, 6th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, R.S. Language development in children and adolescents with Down syndrome. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 1997, 3, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales-Astorgano, M.; Escudero-Mancebo, D.; González-Ferreras, C. Acoustic characterization and perceptual analysis of the relative importance of prosody in speech of people with Down syndrome. Speech Commun. 2018, 99, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).