Abstract

In this paper, we define fractal bases and fractal frames of , where I and J are real compact intervals, in order to approximate two-dimensional square-integrable maps whose domain is a rectangle, using the identification of with the tensor product space . First, we recall the procedure of constructing a fractal perturbation of a continuous or integrable function. Then, we define fractal frames and bases of composed of product of such fractal functions. We also obtain weaker families as Bessel, Riesz and Schauder sequences for the same space. Additionally, we study some properties of the tensor product of the fractal operators associated with the maps corresponding to each variable.

1. Introduction

In a rapidly changing world, with unexpected outcomes, the scientific community has to make particular effort to provide a deeper knowledge and understanding of the reality and natural environment surrounding us. In this way, the adoption of new mathematical tools for a better treatment and study of the social, natural and physical phenomena and processes becomes essential. The framework of fractal interpolation makes it possible to enlarge and improve the classical methods of approximation theory. In previous papers, the author defined fractal functions constructed by means of iterated function systems (see, e.g, [1,2,3]). These maps are fractal perturbations of arbitrary continuous functions defined on compact intervals. The new functions interpolate the original mappings on a set of nodes. This approach can be extended to the space of p-integrable functions, defining the fractal analogues of standard maps in . A scale vector provides the necessary flexibility to approximate a highly irregular or discontinuous function. If the scale is chosen properly, one can obtain fractal bases of the most used functional spaces, beginning from any basis of these sets. This is done by means of a suitable bounded operator, , also known as fractal operator ([1,2,3,4,5]), transforming systems of ordinary spanning families into their fractal perturbations. In the case of multivariate maps, this operator can no longer be applied to get necessary functions, and some additional tools are required. While it is true that fractal approximation is an active field of research currently, and there is an abundant bibliography about multivariate fractal interpolation functions (see, e.g., [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]), our approach has some specificities. One of them is that the functions proposed are products of perturbations of classical maps, and consequently they can be as close to them as desired. In this way, the current approach has two main advantages regarding other existing results. The first one is that the functional bases proposed are a generalization of any product basis (classical or not). This fact provides a wide spectrum of maps, in order to choose the optimum for a particular application, extending the analytical, geometric and dynamical possibilities. The second advantage is the addition of properties, unfeasible for the standard known functions, such as non-differentiability, providing irregular maps whose geometric complexity can be quantified by means of the fractal dimension of their traces for instance.

Although the results presented are deeply theoretical, the potential applications of this type of functions include, but are not restricted to, all the applications of the approximation theory and analysis. These are, for instance, Fourier analysis (used extensively in signal theory), bivariate interpolation and numerical analysis in general, study of chaotic systems, graphical design, mechanical engineering, etc. In particular, all the applications involving the standard functions as polynomial, trigonometric, etc. have their counterpart in this fractal field.

The mappings presented own all the advantages of the traditional functions because they include them as particular cases (taking the scale vectors equal to zero). They also provide new non-smooth geometric objects to model complex behaviors. We could mention as inconveniences, in non-smooth cases, the implicit character of their definition that hinders (though does not prevent) punctual evaluations, and the computational demands for an accurate graphical representation.

In this paper, we define fractal bases and fractal frames of , in order to approximate two-dimensional square-integrable maps whose domain is a rectangle. This is accomplished by means of the identification of with the tensor product space

The paper is organized as follows. Iin Section 2, we introduce the fractal perturbation of a continuous function. In Section 3, we define fractal frames and bases of composed of products of fractal functions. We also obtain weaker families, as Bessel, Riesz and Schauder sequences. Additionally, we study some properties of the tensor product of the fractal operators previously mentioned, corresponding to each variable.

2. -Fractal Functions

In this section, we present the basics of the theory of fractal interpolation, initiated by M. Barnsley [18] and developed further by many authors, for instance, M. A. Navascués [2]. Consider a partition of a real compact interval , and a set of data . Define subintervals for , and the following Iterated Function System (IFS): , where the mappings are such that

for some . The maps are continuous functions satisfying a Lipschitz condition in the second variable:

for and . Additionally, must satisfy some join-up conditions:

for . According to [18] (Theorem 1) and [19] (Theorem 2 of Section 6.2), the described IFS owns a unique attractor that is the graph of a continuous function interpolating the given data. By definition, g is the fractal interpolation function (FIF) of the IFS defined and it is unique satisfying the fractional equation

for and .

In this paper, we consider the following mappings:

where the scale factor is such that . The coefficients of are

The functions are defined by means of two continuous functions f and b, , as

where and .

The fractal interpolation function of this IFS was called by [2] the -fractal function of f with respect to the partition , the scale vector , and the map b.

To define an operator given by , the first author considered in [2] another operator L such that

If is linear and bounded, with respect to the supremum norm

or with respect to -norm

and , , then is also linear and bounded regarding the respective norms.

The functional Equation (2) satisfied by is:

for A consequence of this expression provides a bound of the distance between f and

where is defined as .

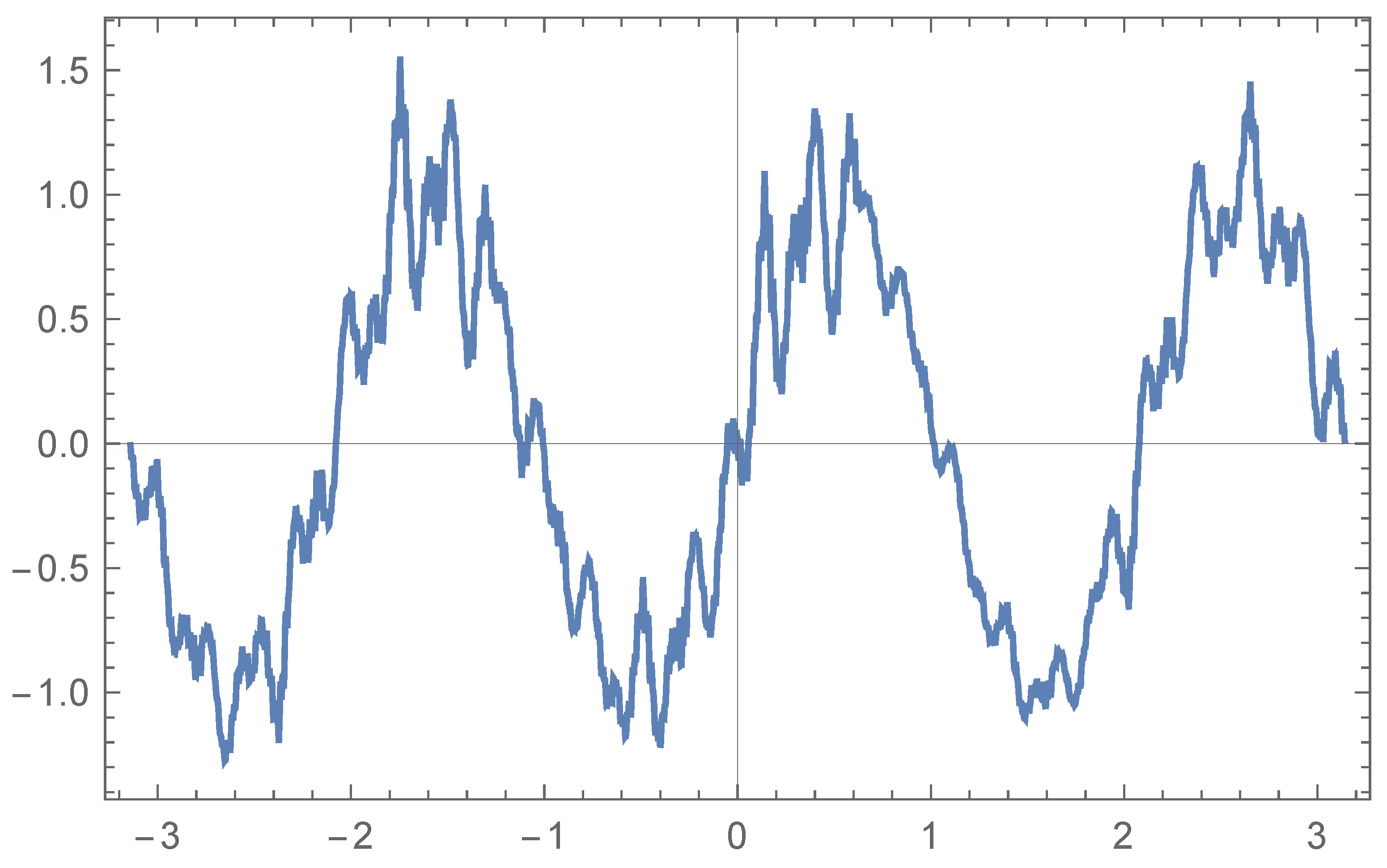

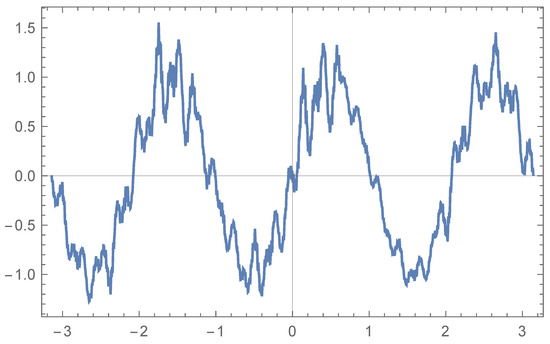

Figure 1 represents the graph of an -fractal function with respect to the operator , where and . The interval is , , the sampling is uniform and .

Figure 1.

Fractal function associated with

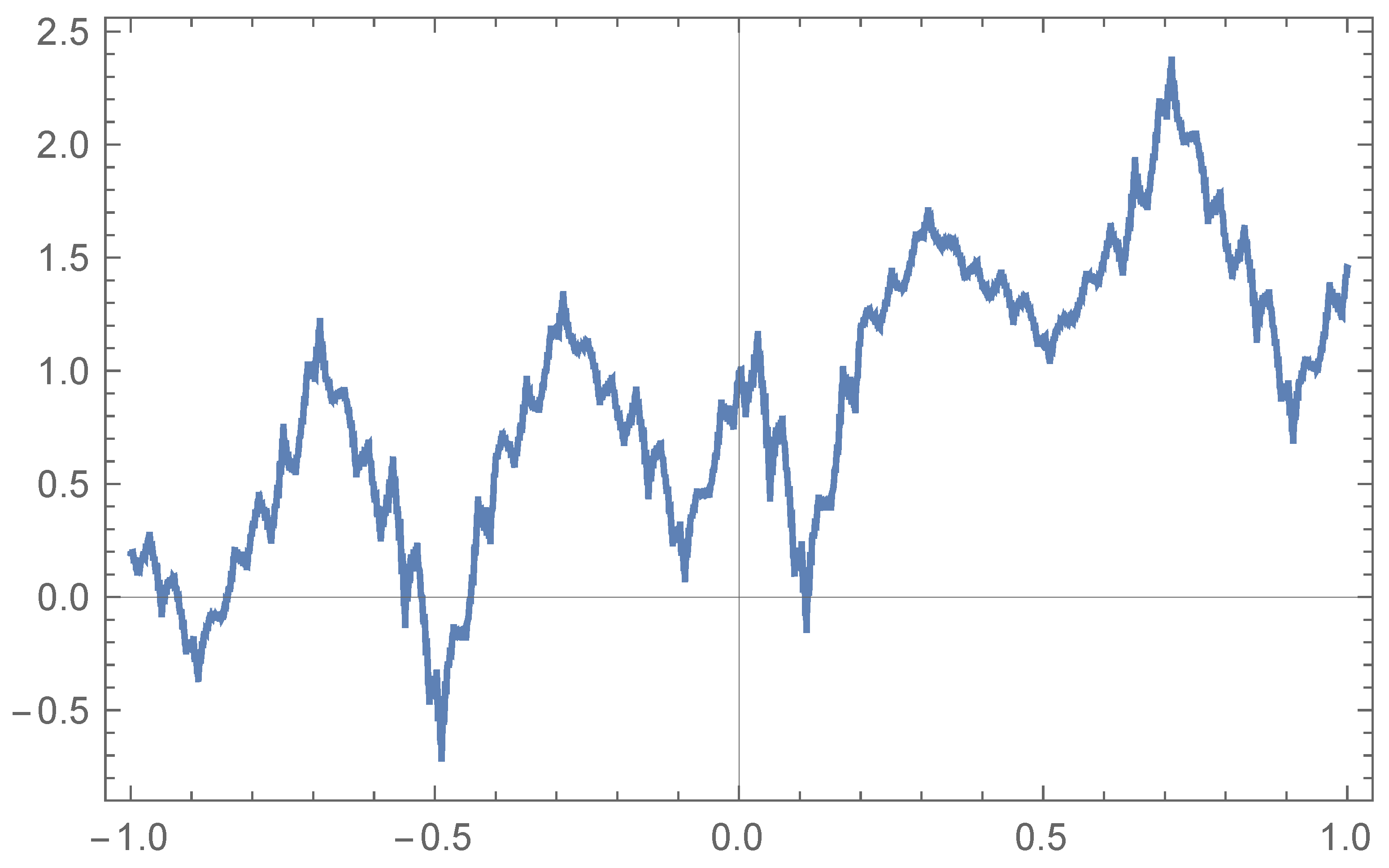

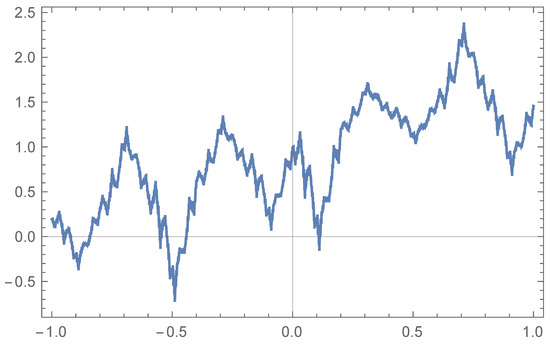

Figure 2 shows the graph of for the operator , the maps and . The interval is , the sampling is uniform and .

Figure 2.

Fractal function associated with

can be extended to , and in this way we obtain fractal perturbations of p-integrable functions ([1]). For convenience, in this paper, we denote as the operator extended to and represents the image of

represents the norm of the operator with respect to the mean square norm in

The operator enjoys many important properties ([1]). For instance, the following inequality holds:

where I is the identity and L is the extension to of the corresponding operator of

Moreover ([1]),

- If , then is injective and has a closed range.

- If , then is an isomorphism.

- If ,

Due to the last item, we can consider that the fractal maps are generalizations of any function.

3. Fractal Frames on the Rectangle

In this section, we analyze the spanning properties of the fractal functions on the rectangle where I and J are compact real intervals. For this purpose, we use the identification with the tensor product space

Let us recall the definition and properties of the tensor product of two Hilbert spaces and . One way of introducing the tensorial product is approached by means of linear operators ([20,21]). We consider spaces on the field R since we deal in general with spaces of real functions (although the extension to complex functions is straightforward). Thus,

Definition 1.

Let , be separable real Hilbert spaces. Their tensor product is defined as

where is an orthonormal basis of

Remark 1.

If is an orthonormal basis of then

The sum is independent of the basis chosen in every space . The operator is the adjoint of

The space is Hilbert with respect to the inner product:

that induces the norm

Remark 2.

The notation is reserved for the norm of A as linear and bounded operator.

Let us define now the tensor product of two vectors and as the operator

where . The main properties of this product are summarized as:

- .

- .

- .

- .

- If is an orthonormal basis of and is an orthonormal basis of , then is an orthonormal basis of

Let denote the dimension of the range of the operator Let us define

and

then

and

The identification of with comes from the equality:

where and Thus, is an integral operator whose kernel is . Similarly, has as kernel the sum The following result can be read in ([20], Th. 7.16)

Theorem 1.

The identification of with the function extends uniquely to an isometric isomorphism of with whose inverse identifies with the operator

Let The definition of the tensor product of implies that:

Definition 2.

A Riesz basis of a Hilbert space H is a system equivalent to an orthonormal basis , that is to say, there is an isomorphism such that for any m.

Definition 3.

A Riesz sequence of a Hilbert space H is a Riesz basis for its closed span . If , then it is a Riesz basis.

In [3], the following result is proved:

Theorem 2.

If is an orthonormal basis of and α is a scale factor such that , then is a Riesz basis of .

Remark 3.

This result is also true for a non-orthonormal basis since there is a topological isomorphism such that . With these hypotheses, is also an isomorphism and and are equivalent bases.

Let us recall now the tensor product of two linear operators.

Definition 4.

If S is a linear and bounded operator of and T is a linear and bounded operator of then

is defined as:

where is linear, bounded and satisfying .

The main properties of this tensor product are:

- is linear and bounded as operator of .

- .

- .

- .

- .

Remark 4.

The notation represents the norm as operator of (with respect to in ).

Let us define

Remark 5.

is the operator that maps a function into . is the operator defined in (6) for the second variable and β is the scale vector in the y-direction.

Theorem 3.

Let and be Riesz bases of and respectively, and let us consider scale vectors α and β satisfying and , then is a Riesz basis of .

Proof.

The tensor product is a Riesz basis. In this case, and are topological isomorphisms due to Theorem 2. Taking and in the properties 4 and 6 before Remark 4, we have that is an isomorphism. Then, is a basis equivalent to □

According to Property of the tensor product of operators:

Moreover (Theorem 3.3 of [1]),

and

Lemma 1.

If then

Proof.

If , the inequality (9) and the condition on imply that

Thus,

and

Remark 6.

If or , the norm reaches the bound given in the previous Lemma since , improving the limit provided in Theorem 3.7 of the reference [1].

Definition 5.

The constant C of a basis of a Banach space H is

where is the Nth partial sum operator of the expansion

for any that is to say, defined by

Proposition 1.

In the conditions of Theorem 3, the constant of the basis satisfies the inequality:

where C is the constant of the basis

Proof.

Let us consider and the expansion of the element defined as

where represent the coefficient of U with respect to the basis Then,

Definition 6.

A sequence , where H is a Hilbert space, is a frame if there exist constants such that for all

For the next results, we need additional properties of the fractal families in .

Proposition 2.

If is a frame and , then is a frame of .

Proof.

For the right inequality of (17), let us think that for ,

where k is the right bound of the frame (B in the expression (17)). For the left inequality, according to Proposition 4.8 and Theorem 4.18 of [1], is injective with closed range and is defined on the range of . For , and

Moreover, since is a frame,

where is is the left bound of the frame (A in the expression (17)). Using the inequality (18), the result is proved. □

Proposition 3.

If are frames and , then is a frame of .

Proof.

In this case, and are frames according to the previous proposition. The tensor product of frames is a frame (Theorem 2.3, [22]) and consequently by Property of Definition 4

is a frame. □

Definition 7.

A sequence of a Hilbert space H is a Bessel sequence if there exists a constant such that for any

Theorem 4.

If , are frames of and , then is a Bessel sequence for any scale vectors α, β.

Proof.

Let us consider any then

The first inequality is due to the fact that is a frame, and the last equality comes from Property (3) of Definition 4. □

In the following lemma, represents the adjoint of A, and the same notation is used for all the operators concerned.

Lemma 2.

If then , and

Moreover, if is bounded below, there exists a constant such that

and, if is bounded below, there exists a constant such that

Proof.

Let us take, for instance, the first element . It is linear and bounded operator from to and

and

where and are orthonormal bases of and , respectively. The proof of the rest of the inequalities is similar. □

Theorem 5.

Let and be orthonormal bases of and , respectively. If is a frame and is bounded below, then is a frame of

The upper frame constant is and the lower is , where M is the lower frame constant of and is such that

for any

Proof.

The right inequality of (17) is proved in the previous theorem. The tensor product of orthonormal bases is an orthonormal basis and the constant K of the previous theorem is equal to one.

For the left one, let us consider any then

and

Consequently,

The previous inequality is due to the fact that is a frame. Since is bounded below,

applying the previous lemma. □

Proposition 4.

Let and be orthonormal bases. If and then is a frame.

Proof.

It is a consequence of Theorem 2 ( is a Riesz basis) and Proposition 2 ( is a frame). □

Corollary 1.

Let and be orthonormal bases. If is a frame, then is a frame.

Proof.

In this case, () and is bounded below. Applying Theorem 5, one obtains the result. In addition, note that the tensor product of frames is a frame. □

The following lemma can be read in [22], Theorem 2.6.

Lemma 3.

If Q is a linear and bounded invertible operator of H and is a frame of , then the sequence is also a frame of

Theorem 6.

If and are frames of and , respectively, then is a frame.

Proof.

Let us consider the former lemma for and . With the hypothesis on , is invertible and consequently is a frame. Let us see that .

for every . This completes the proof. □

Lemma 4.

If Q is an invertible, linear and bounded operator of K and is a frame of , then is also a frame.

Proof.

It can be read in [22], Corollary 2.11. □

Theorem 7.

If and are frames of and , respectively, then is a frame.

Proof.

With the hypothesis on the scale vector , is invertible. Consequently, is as well. Since is a frame, applying the previous lemma, is a frame.

Let us prove now that

For any ,

This equality completes the proof. □

Theorem 8.

If , and are frames, then is a frame.

Proof.

By definition of the tensor product of operators,

Let us consider now that, according to the previous theorem,

Since is invertible, is a frame. Then,

is a frame, using Theorem 6. □

Proposition 5.

If and then is injective and

Proof.

With the hypotheses on and , and are injective with closed range (Proposition 4.8 and Theorem 4.18 of [1]). Let us denote Then, if , due to the properties of the tensor product of vectors:

On the other side,

(The inverse operators are defined on the range of and respectively). The continuity and linearity of imply that

For the other content, if , then there exists such that Since

The equality of ranges (19) implies that is a Hilbert space and then closed. To prove the injectivity of , let us consider that, if

then

according to Properties and of the tensor product of operators. □

Corollary 2.

If and then is bounded below.

Proof.

In these hypotheses, and are injective and and are isomorphisms on and , respectively.

is bounded on and thus

for any □

Corollary 3.

If and then is surjective.

Proof.

In general,

However, is injective and is closed, thus is also closed ([23]). Consequently, the operator quoted is surjective. □

Definition 8.

A sequence , where H is a Hilbert space, is a frame sequence if it is a frame for its closed span .

Proposition 6.

If and and and are frames, then is a frame sequence.

Proof.

According to the definition of frame sequence, we need to prove that there exist constants such that, for all ,

The right inequality is already proved in Theorem 4. According to Proposition 5, is bounded on the range of

If , since

then

As is a frame,

Definition 9.

A sequence of a Hilbert space H is a Riesz sequence if there exist such that for any

Theorem 9.

Let and be Riesz bases of and , respectively. If and is a Riesz sequence of

Proof.

In these hypotheses, is a topological isomorphism on its range, and thus it preserves the bases. □

Definition 10.

A sequence of a Banach space is a Schauder sequence if it is a Schauder basis ([24]) for .

Theorem 10.

If are Riesz bases of , and , then is a Schauder sequence of .

Proof.

With the hypotheses given is a topological isomorphism from on and the isomorphisms preserve the bases. □

Proposition 7.

If the operators are defined as , where are fixed mappings strictly increasing, continuous and such that and , then 1 belongs to the point spectrum of

Proof.

In this case, 1 belongs to the point spectrum of and (Proposition 2 of [2]) and the product of eigenvalues is an eigenvalue of the tensor product. □

4. Conclusions

In this article, we define Riesz bases of the Hilbert space composed of products of single variable fractal functions. The factors are of type -fractal functions, which constitute a generalization (or perturbation) of any map defined on a compact real interval. An operator maps any (classical) function into its counterpart (-fractal). This operator is generalized in the paper to a two-dimensional operator via tensor product.

We also obtain weaker spanning systems of square integrable functions on the rectangle as Bessel, Riesz, Schauder and frame sequences and frames. All of them are composed of products of fractal functions. The frames own a greater flexibility in order to choose good approximations of mappings. We deduce also frame and Bessel constants, in terms of the bounds of the unperturbed (non-fractal) functions. We construct functions defined on the rectangle in order to simplify the formalism, but the definition and properties are straightforwardly generalizable to higher dimensions, considering products of three factors (functions on a parallelepiped) and more. The advantages and inconveniences are similar to the two-variable case. Of course, the higher dimensionality complicates the computational work, cost and graphical performances.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.N. and R.M.; methodology, M.A.N.; supervision, M.A.N. and R.M; visualization, M.N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.A.; writing—review and editing, M.N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Navascués, M.A. Fractal approximation. Complex Anal. Oper. Theory 2010, 4, 953–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navascués, M.A. Fractal polynomial interpolation. Z. Anal. Anwend 2005, 25, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navascués, M.A. Fractal bases of spaces. Fractals 2012, 20, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.N.; Prasad, M.G.P.; Navascués, M.A. Fractal Jacobi systems and convergence of Fourier-Jacobi expansions of fractal interpolation functions. Mediterr. J. Math. 2016, 13, 3965–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, P.; Navascués, M.A. A fractal operator on some standard spaces of functions. Proc. Edinb. Math. Soc. 2017, 60, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnsley, M.F.; Massopust, P.R. Bilinear fractal interpolation and box dimension. J. Approx. Theory 2015, 192, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouboulis, P.; Dalla, L.; Drakopoulos, V. Construction of recurrent bivariate fractal interpolation surfaces and computation of their box-counting dimension. J. Approx. Theory 2006, 141, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bouboulis, P.; Dalla, L. A general construction of fractal interpolation functions on grids of Rn. Eur. J. Appl. Math. 2007, 18, 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, A.K.B.; Kapoor, G.P. Hidden variable bivariate fractal interpolation surfaces. Fractals 2003, 11, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla, L. Bivariate fractal interpolation functions on grids. Fractals 2002, 10, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakopoulos, V.; Manousopoulos, P. On non-tensor product bivariate fractal interpolation surfaces on rectangular grids. Mathematics 2020, 8, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar M., N.; Prasad, M.G.P.; Navascués, M.A. More general fractal functions on the sphere. Mediterr. J. Math. 2019, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, D.P.; Massopust, P.R. Fractal interpolation functions from Rn into Rm and their projections. Z. Anal. Anwendungen 1993, 12, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzer, W.; Yun, C.H. Construction of fractal interpolation surfaces on rectangular grids. Int. J. Bifurcationand Chaos Appl. Sci. Eng. 2010, 20, 4079–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.J.; Xu, Q. Fractal interpolation surfaces on rectangular grids. Bull. Aust. Math. Soc. 2015, 91, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Sun, H. The study on bivariate fractal interpolation functions and creation of fractal interpolated surfaces. Fractals 1997, 5, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N. Construction and application of fractal interpolation surfaces. Vis. Comput. 1996, 12, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnsley, M.F. Fractal functions and interpolation. Constr. Approx. 1986, 2, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnsley, M.F. Fractal Everywhere; Academic Press, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Folland, G.B. A Course in Abstract Harmonic Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kadison, R.V.; Ringrose, J.R. Fundamental of the Theory of Operator Algebras, Volume I; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi, A.; Asgari, M.S. Frames and bases in tensor product of Hilbert spaces. Int. Math. J. 2003, 4, 527–537. [Google Scholar]

- Lebedev, L.P.; Vorovich, I.I.; Gladwell, G.M.L. Functional Analysis, 2nd ed.; Kluwer Academic Publ.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Heil, C. A Basis Theory Primer; Birkhhauser: Basel, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).