Fractal Hankel Transform

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamental Definitions in Fractal Calculus

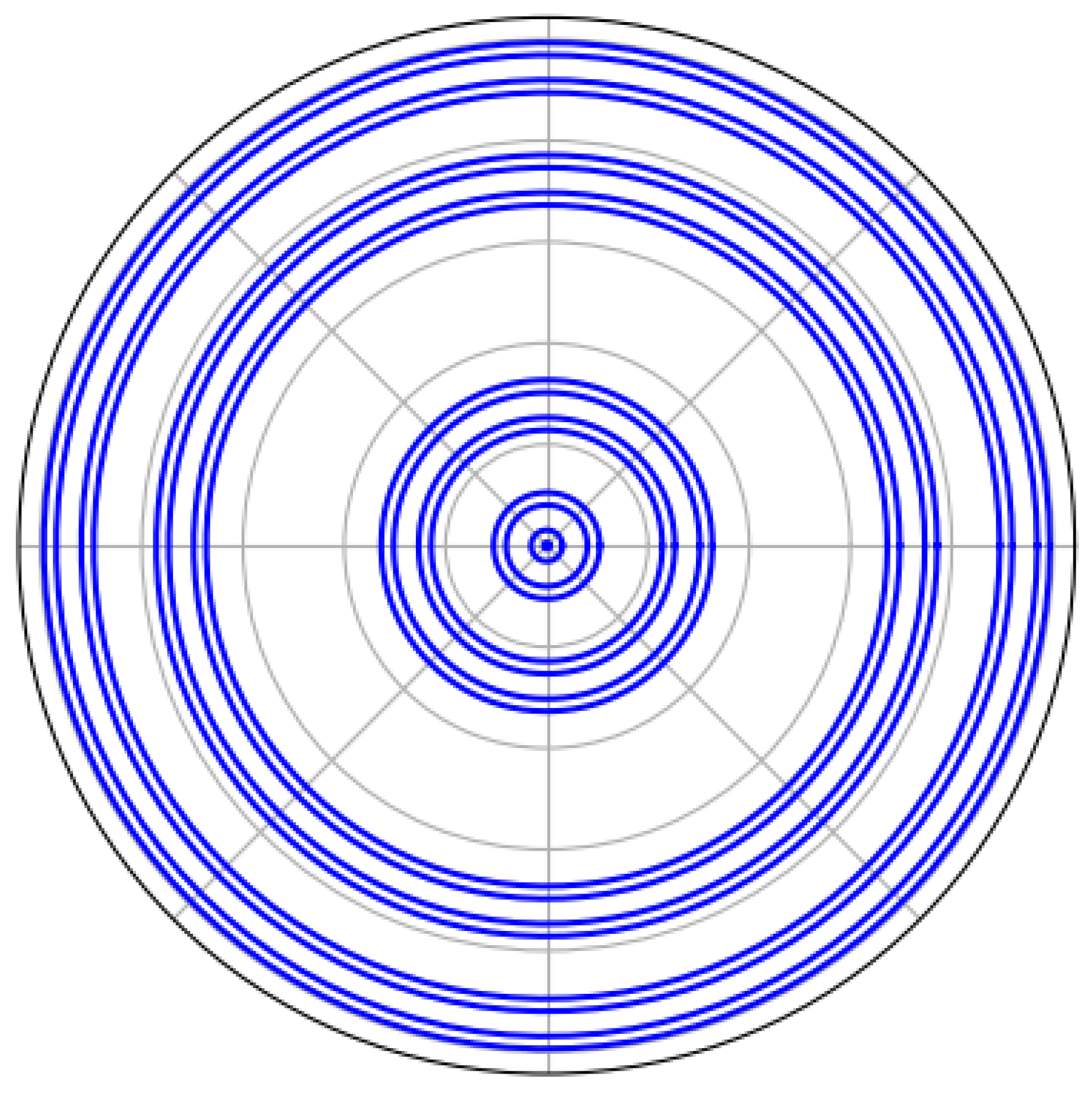

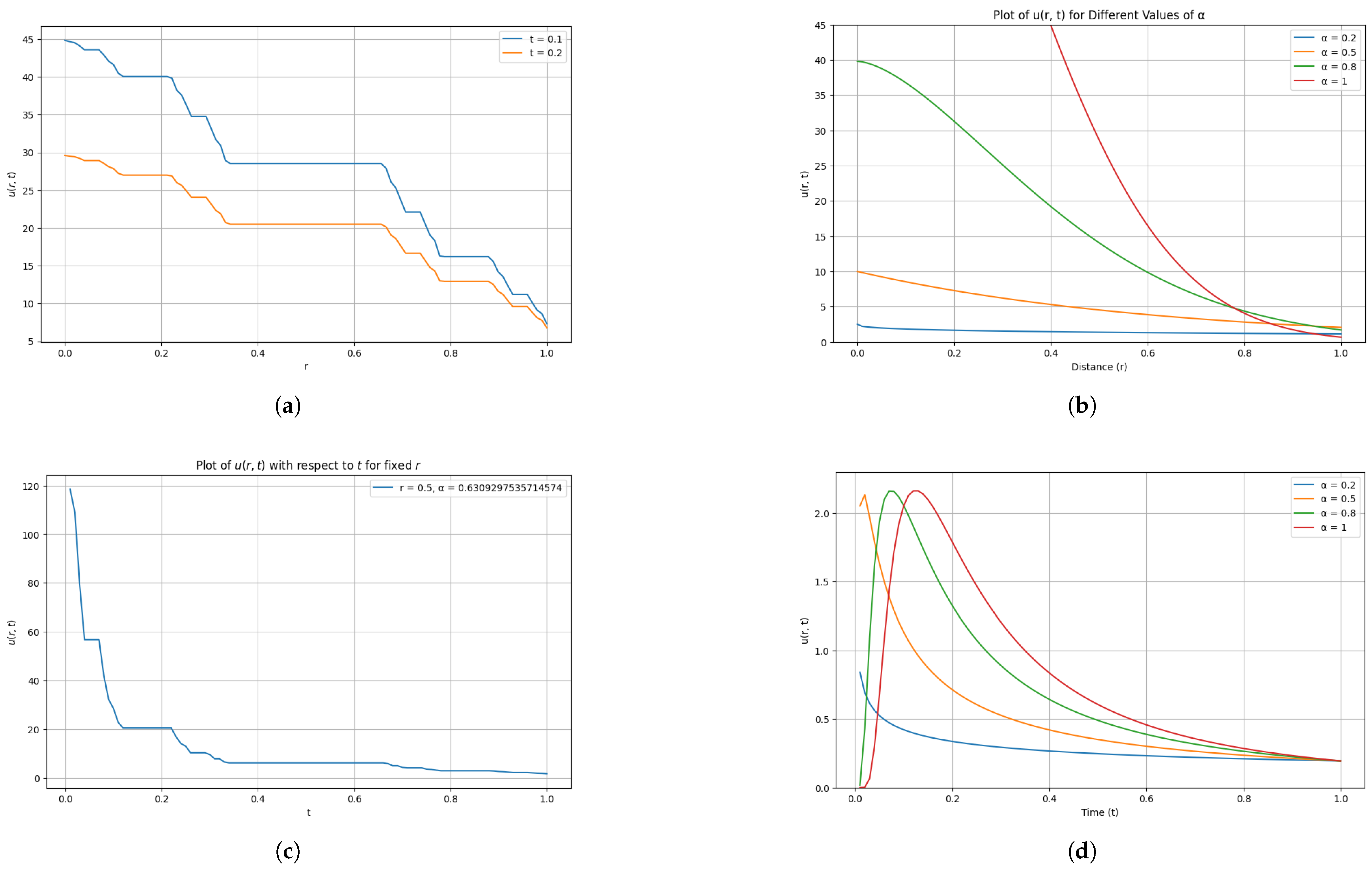

3. Fractal Hankel Transform

- 1.

- For :

- 2.

- For :

4. Application of Fractal Hankel Transform

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature; WH Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Massopust, P.R. Fractal Functions, Fractal Surfaces, and Wavelets; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, K. Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Feder, J. Fractals; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov, V.E. Fractional Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, M.T.; Perkins, E.A. Brownian motion on the Sierpinski gasket. Probab. Theory Relat. Fields 1988, 79, 543–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillinger, F.H. Axiomatic basis for spaces with noninteger dimension. J. Math. Phys. 1977, 18, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiberg, U.; Zähle, M. Harmonic calculus on fractals-a measure geometric approach I. Potential Anal. 2002, 16, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kigami, J. Analysis on Fractals; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, P.E.T. Harmonic Analysis: Smooth and Non-Smooth; CBMS Regional Conference Series in Mathematics; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2018; Volume 128, Smooth and non-smooth, Published for the Conference Board of the Mathematical Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, P.E. Analysis and Probability: Wavelets, Signals, Fractals; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 234. [Google Scholar]

- Withers, W. Fundamental theorems of calculus for Hausdorff measures on the real line. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1988, 129, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Su, W. Some fundamental results of calculus on fractal sets. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 1998, 3, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiorno, D. Derivatives not first return integrable on a fractal set. Ric. Mat. 2018, 67, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiorno, D.; Corrao, G. On the fundamental theorem of calculus for fractal sets. Fractals 2015, 23, 1550008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiorno, D.; Corrao, G. An integral on a complete metric measure space. Real Anal. Exch. 2015, 40, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, N.; Jebali, H. On the construction of recurrent fractal interpolation functions using Geraghty contractions. Electron. Res. Arch. 2023, 31, 6866–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, N.; Jebali, H.; Guedri, R. On a class of Hausdorff measure of cartesian product sets in metric spaces. Topol. Methods Nonlinear Anal. 2023, 62, 601–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Li, Z.; Selmi, B. Upper metric mean dimensions with potential on subsets. Nonlinearity 2021, 34, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkay, D.E.; Jorgensen, P.E. Wavelets on fractals. Rev. Mat. Iberoam. 2006, 22, 131–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, P.E.; Pedersen, S. Dense analytic subspaces in fractal L 2-spaces. J. Anal. Math. 1998, 75, 185–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraev, D.A.; Mammadzada, N.M. Fractals and Its Applications. Karshi Multidis. Int. Sci. J. 2024, 1, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Parvate, A.; Gangal, A.D. Calculus on fractal subsets of real line-I: Formulation. Fractals 2009, 17, 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvate, A.; Gangal, A. Calculus on fractal subsets of real line-II: Conjugacy with ordinary calculus. Fractals 2011, 19, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satin, S.E.; Parvate, A.; Gangal, A. Fokker-Planck equation on fractal curves. Chaos Solit. Fractals 2013, 52, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmankhaneh, A.K. Fractal Calculus and Its Applications; World Scientific: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Golmankhaneh, K.A.; Welch, K.; Serpa, C.; Jørgensen, P.E. Fractal Mellin transform and non-local derivatives. Georgian Math. J. 2024, 31, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchuin, R. Noise analysis of electrical circuits on fractal set. COMPEL-Int. J. Comput. Math. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2022, 41, 1464–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchuin, R. Nonlocal fractal calculus based analyses of electrical circuits on fractal set. Compel-Int. J. Comput. Math. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2022, 41, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmankhaneh, A.K.; Welch, K. Equilibrium and non-equilibrium statistical mechanics with generalized fractal derivatives: A review. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2021, 36, 2140002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nottale, L. Fractal Space-Time and Microphysics: Towards a Theory of Scale Relativity; World Scientific: Singapore, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pietronero, L.; Tosatti, E. Fractals in Physics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Deppman, A.; Megías, E.; Pasechnik, R. Fractal Derivatives, Fractional Derivatives and q-Deformed Calculus. Entropy 2023, 25, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shlesinger, M.F. Fractal Time in Condensed Matter. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1988, 39, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrobel, S. Fractal Time; World Scientific: Singapore, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, K. A Fractal Topology of Time: Deepening into Timelessness; Fox Finding Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Golmankhaneh, K.A.; Welch, K.; Serpa, C.; Rodríguez-López, R. Fractal Laplace transform: Analyzing fractal curves. J. Anal. 2024, 32, 1111–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmankhaneh, A.K.; Welch, K.; Serpa, C.; Jørgensen, P.E. Non-standard analysis for fractal calculus. J. Anal. 2023, 31, 1895–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmankhaneh, A.K.; Welch, K.; Serpa, C.; Stamova, I. Stochastic processes and mean square calculus on fractal curves. Random Oper. Stoch. Equ. 2024, 32, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.C.; Shivamoggi, B.K. Integral Transforms for Engineers; SPIE Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1999; Volume 66. [Google Scholar]

- Poularikas, A.D.; Grigoryan, A.M. Transforms and Applications Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, L.; Bhatta, D. Integral Transforms and Their Applications; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cree, M.; Bones, P. Algorithms to numerically evaluate the Hankel transform. Comput. Math. Appl. 1993, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, A.I. Handbook of Function and Generalized Function Transformations; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bracewell, R.; Kahn, P.B. The Fourier transform and its applications. Am. J. Phys. 1966, 34, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, I.N. Fourier Transforms; Courier Corporation: Mineola, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, G.N. A Treatise on the Theory of Bessel Functions; The University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1922; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Columbu, A.; Fuentes, R.D.; Frassu, S. Uniform-in-time boundedness in a class of local and nonlocal nonlinear attraction–repulsion chemotaxis models with logistics. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2024, 79, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Frassu, S.; Viglialoro, G. Combining effects ensuring boundedness in an attraction–repulsion chemotaxis model with production and consumption. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 2023, 74, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Golmankhaneh, A.K.; Şevli, H.; Cattani, C.; Vidović, Z. Fractal Hankel Transform. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030135

Golmankhaneh AK, Şevli H, Cattani C, Vidović Z. Fractal Hankel Transform. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(3):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030135

Chicago/Turabian StyleGolmankhaneh, Alireza Khalili, Hamdullah Şevli, Carlo Cattani, and Zoran Vidović. 2025. "Fractal Hankel Transform" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 3: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030135

APA StyleGolmankhaneh, A. K., Şevli, H., Cattani, C., & Vidović, Z. (2025). Fractal Hankel Transform. Fractal and Fractional, 9(3), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030135