New Predefined Time Sliding Mode Control Scheme for Multi-Switch Combination–Combination Synchronization of Fractional-Order Hyperchaotic Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

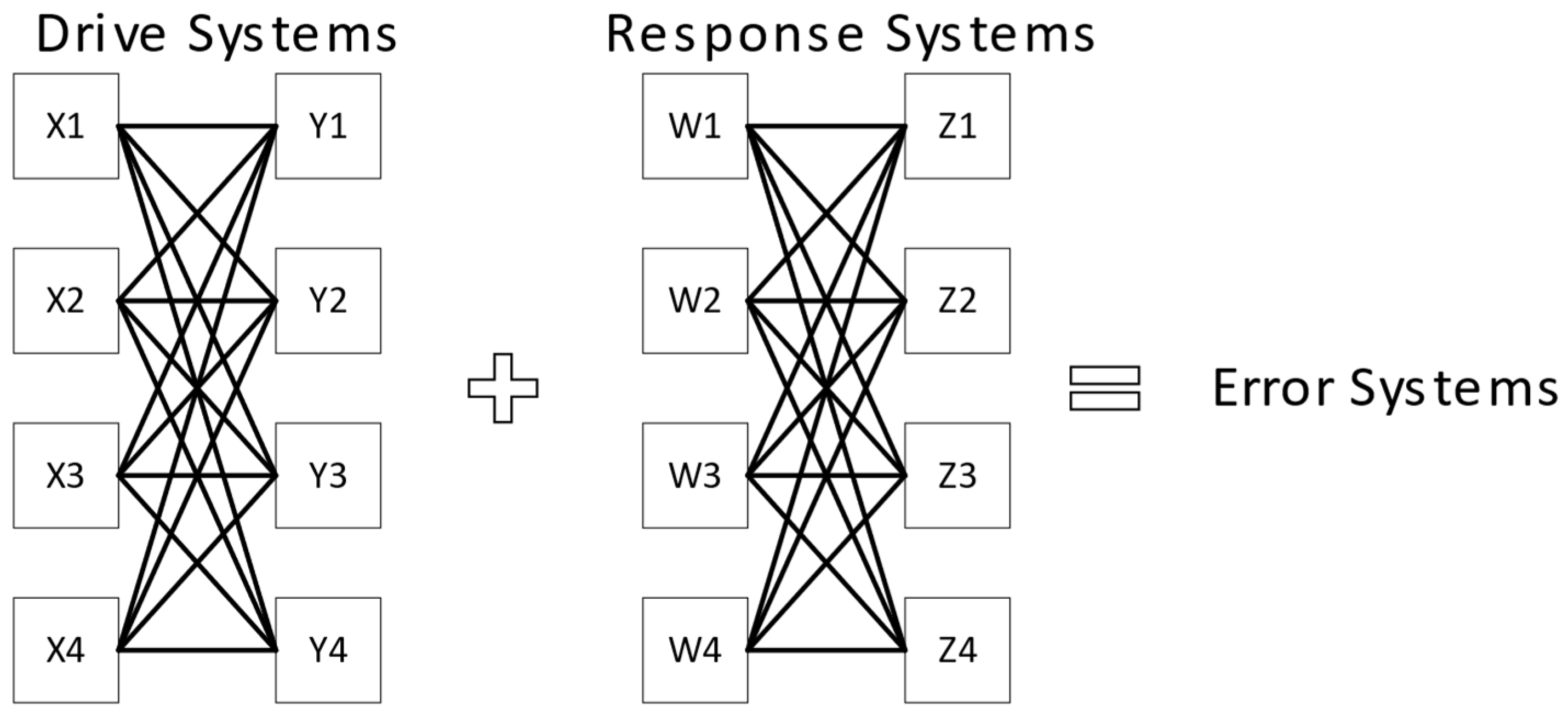

3. System and Problem Description

- Assume the origin of system (5) is fixed time stable [51], and the settling time is , which is a time function of the error.

4. New Predefined Time Sliding Mode Control Scheme

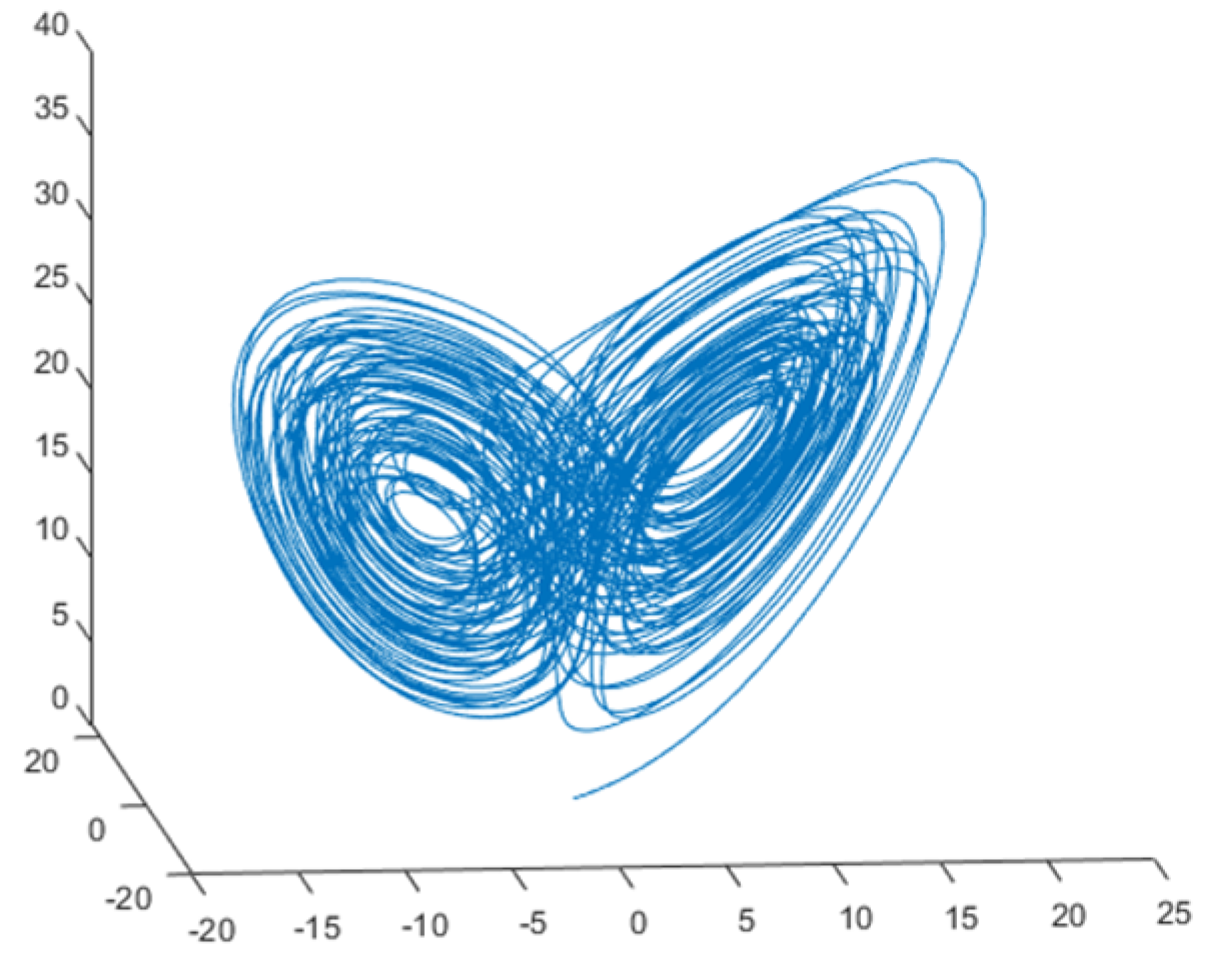

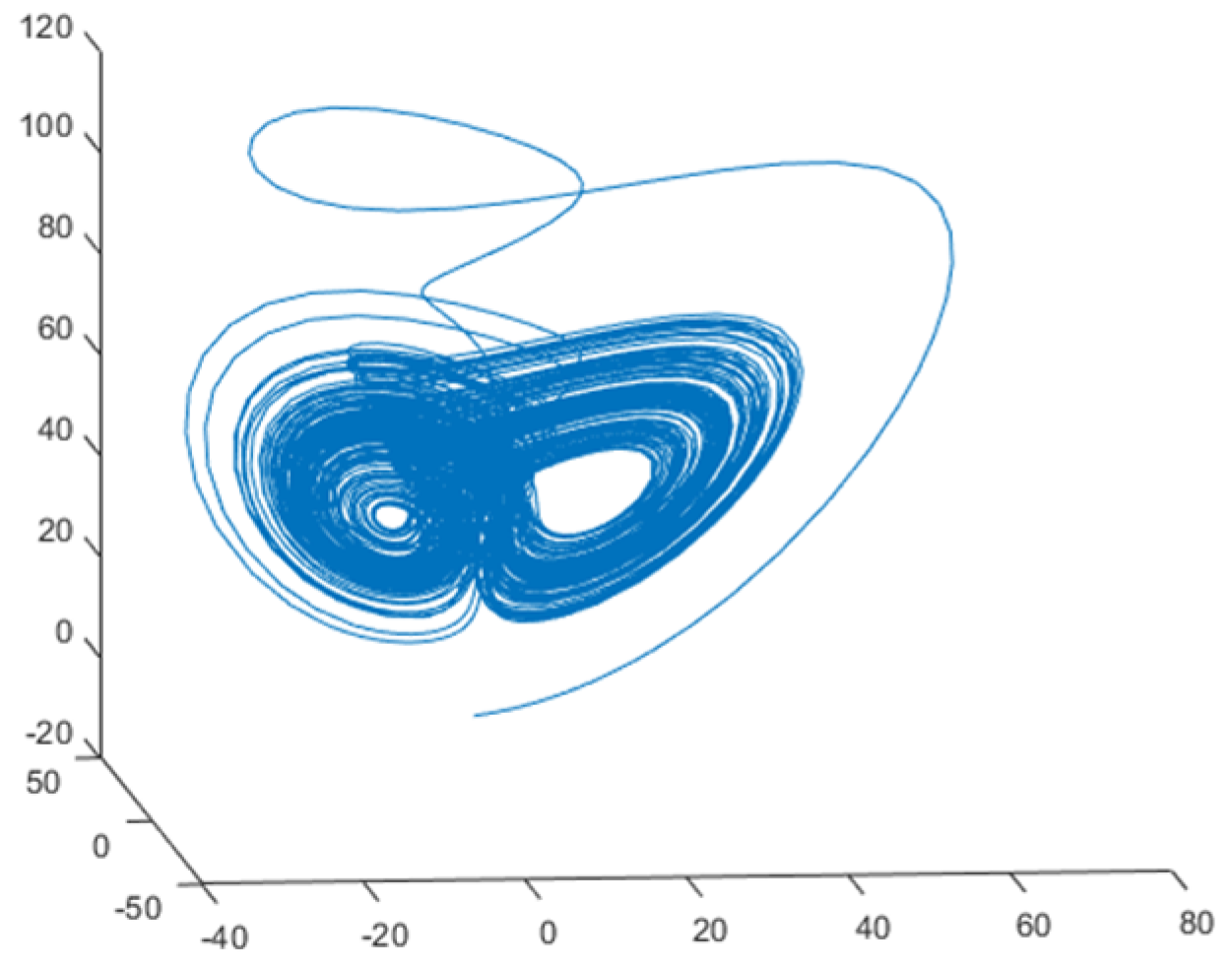

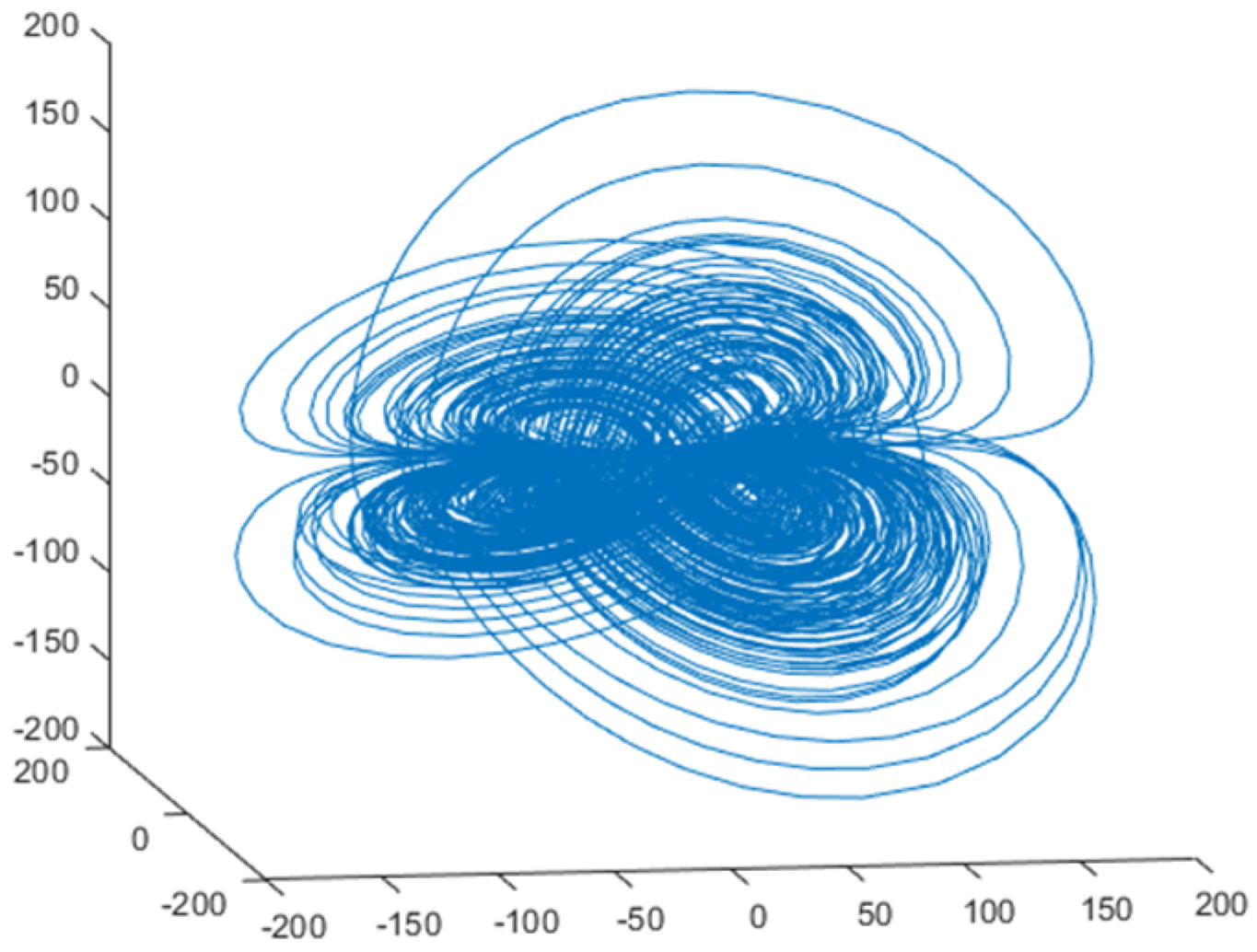

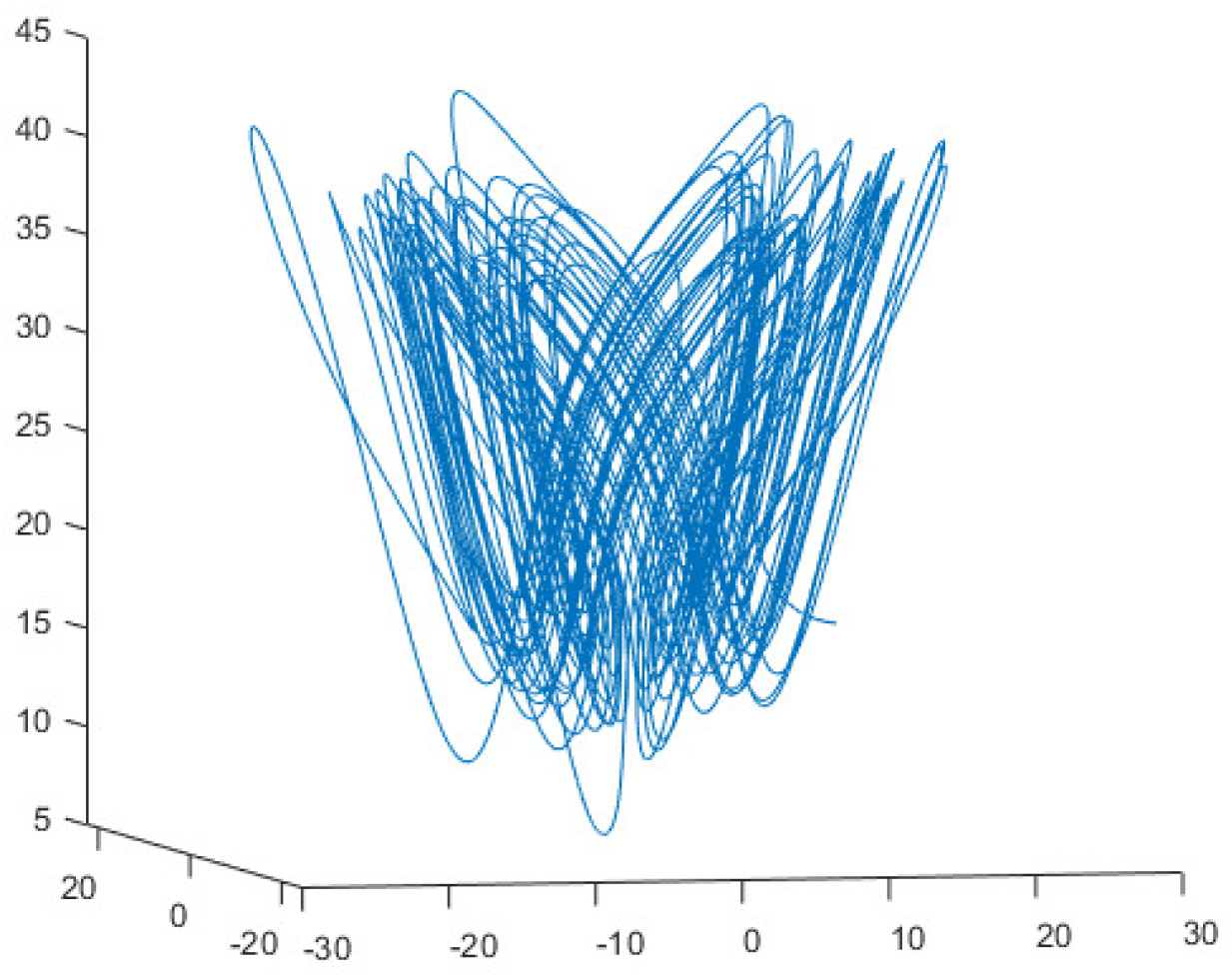

5. Numerical Simulation

- where the system parameters are , , , , , , , , , and , and , represent the state vectors of different hyperchaotic systems. Moreover, the parameter uncertainties and the external disturbances in drive FO hyperchaotic systems are

- where the system parameters are , , , , , , , and , and , are the state vectors of different hyperchaotic systems, and the time. Moreover, the parameter uncertainties and the external disturbances in response to FO hyperchaotic systems are

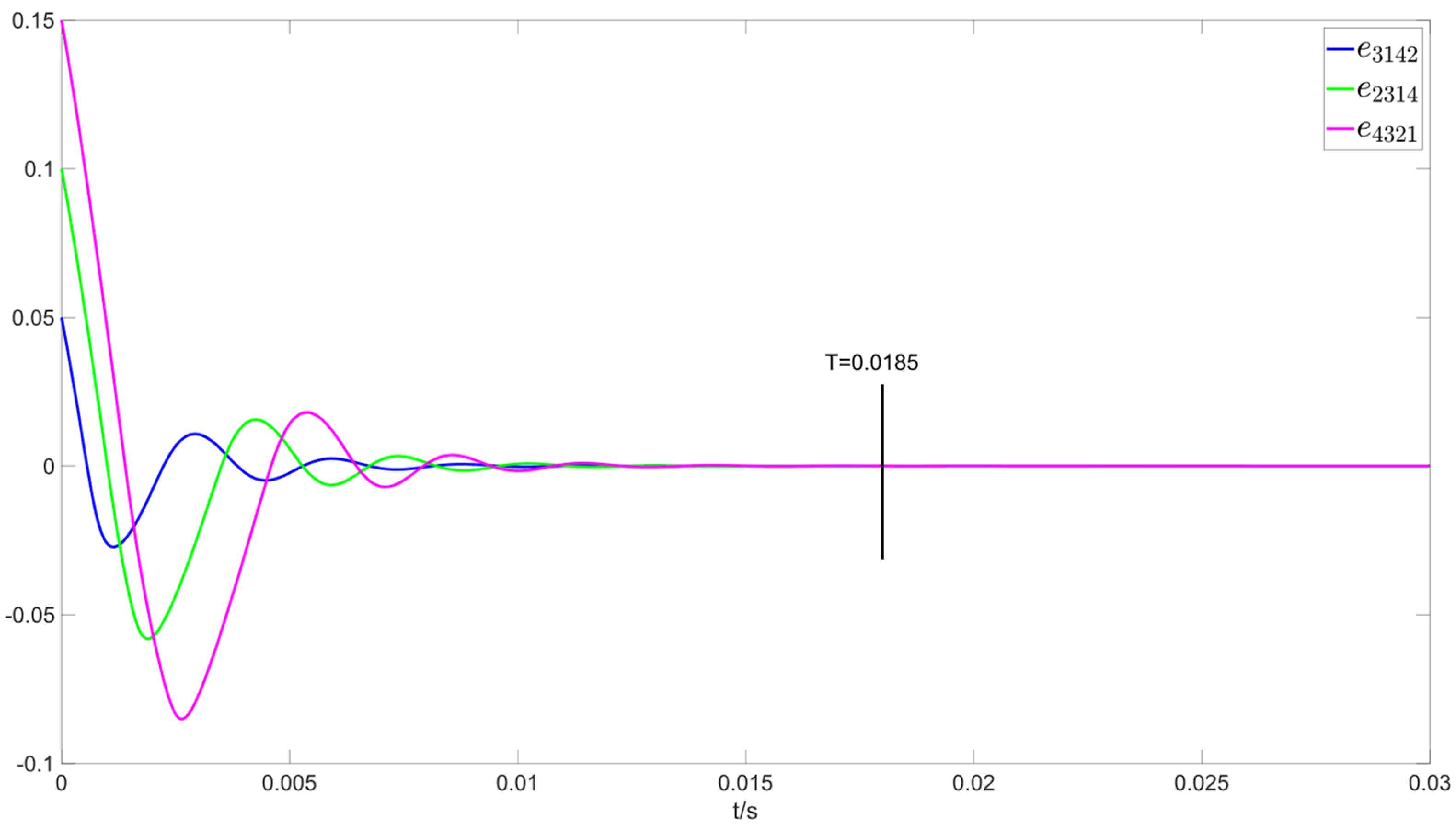

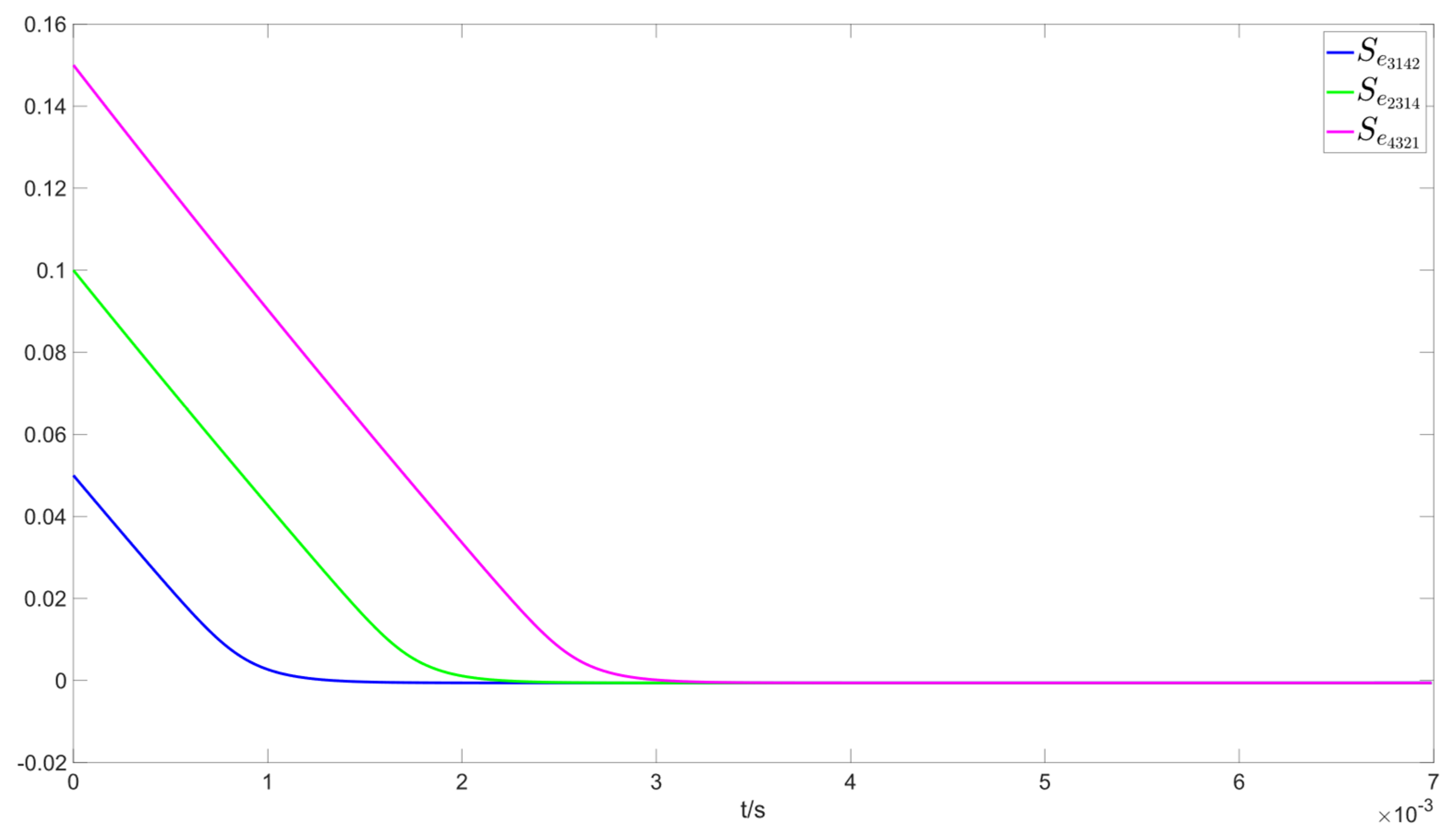

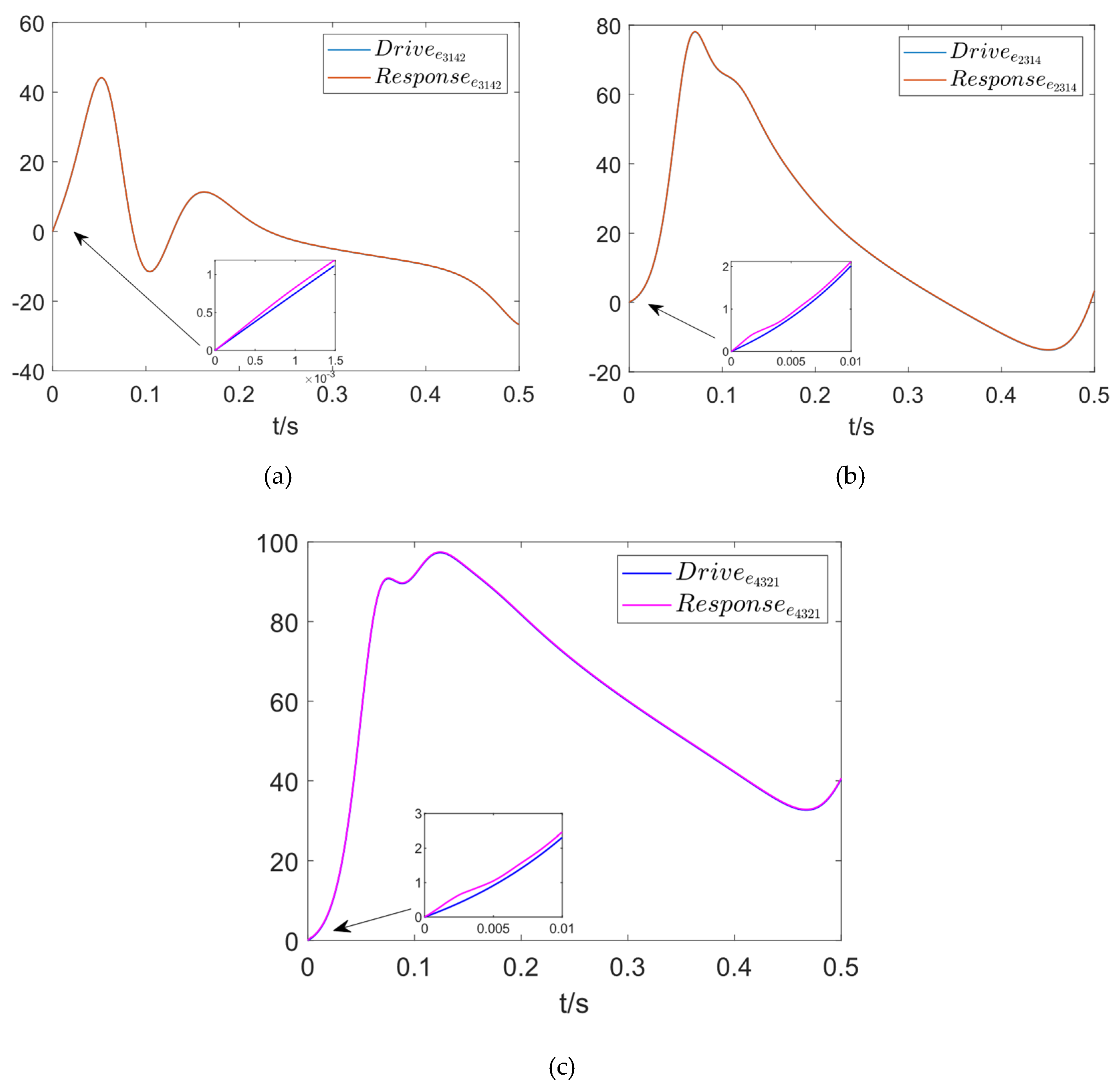

Predefined Time Multi-Switch Combination–Combination Synchronization

6. Results

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ye, K.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H. A Generalized Computationally Efficient Copula-Polynomial Chaos Framework for Probabilistic Power Flow Considering Nonlinear Correlations of PV Injections. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 136, 107727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeresha, P. The Efficient Fractional Order Based Approach to Analyze Chemical Reaction Associated with Pattern Formation. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 165, 112862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Gao, X.; An, H.; Jia, N.; Wang, A. Exploring Market Instability of Global Lithium Resources Based on Chaotic Dynamics Analysis. Resour. Policy 2024, 88, 104373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Qiu, K.; Deng, C.; Zhou, N. An Image Compression and Encryption Algorithm Based on Chaotic System and Compressive Sensing. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 115, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabil, H.; Tayeb, H. A Secure Communication Scheme Based on Generalized Modified Projective Synchronization of a New 4-D Fractional-Order Hyperchaotic System. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 095203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; An, X.; Xiong, L.; Yang, F.; Zhang, L. Dynamic Analysis of a Fractional-Order Hyperchaotic System and Its Application in Image Encryption. Phys. Scr. 2022, 97, 045201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaadi, F.E.; Jahanshahi, H.; Yao, Q.; Mou, J. Recurrent Neural Network-Based Technique for Synchronization of Fractional-Order Systems Subject to Control Input Limitations and Faults. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 173, 113717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwan, M.; Li, F.; Ahmad, S.; Wang, N. Mixed Obstacle Avoidance in Mobile Chaotic Robots with Directional Keypads and Its Non-Identical Generalized Synchronization. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 113, 2377–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecora, L.M.; Carroll, T.L. Synchronization in Chaotic Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 821–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, R.; Wang, T.; Qiu, J. Event-Triggered Adaptive Backstepping Dynamic Surface Control for Strict-Feedback Fractional-Order Nonlinear Systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 China Automation Congress (CAC), Xiamen, China, 25 November 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 3824–3828. [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoei, M.S. Fractional Order Chaotic Systems: History, Achievements, Applications, and Future Challenges. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2020, 229, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, L.-J.; Chen, H.-K.; Chen, J.-H.; Tam, L.-M. Chaos in a New System with Fractional Order. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2007, 31, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Li, S.; Banerjee, S.; Mou, J. A New Fractional-Order Complex Chaotic System with Extreme Multistability and Its Implementation. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 055201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefpour, A.; Jahanshahi, H.; Munoz-Pacheco, J.M.; Bekiros, S.; Wei, Z. A Fractional-Order Hyper-Chaotic Economic System with Transient Chaos. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 130, 109400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneev, I.A.; Semenov, V.V.; Slepnev, A.V.; Vadivasova, T.E. Complete Synchronization of Chaos in Systems with Nonlinear Inertial Coupling. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 142, 110459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Nigar, U. Combination Projective Synchronization in Fractional-Order Chaotic System with Disturbance and Uncertainty. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 2020, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lu, Y. Generalized Projective Synchronization of the Fractional-Order Chen Hyperchaotic System. Nonlinear Dyn. 2009, 57, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Srivastava, M.; Leung, A.Y.T. Hybrid Phase Synchronization between Identical and Nonidentical Three-Dimensional Chaotic Systems Using the Active Control Method. Nonlinear Dyn. 2013, 73, 2261–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S. Multi-Switching Combination Synchronization of Three Different Chaotic Systems via Nonlinear Control. Optik 2016, 127, 10247–10258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailong, Z.; Ding, Z.; Wang, L. Predefined-Time Multi-Switch Combination-Combination Synchronization of Fractional-Order Chaotic Systems with Time Delays. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Li, T.; Wang, Y. The Multi-Switching Sliding Mode Combination Synchronization of Fractional Order Non-Identical Chaotic System with Stochastic Disturbances and Unknown Parameters. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, U.E.; Saseyi, A.O.; McClintock, P.V.E. Multi-Switching Combination Synchronization of Chaotic Systems. Nonlinear Dyn 2015, 80, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.G.; Yoo, S.J. Predefined-time-synchronized Backstepping Control of Strict-feedback Nonlinear Systems. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2023, 33, 7563–7582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, X.; Ding, Q. Adaptive Neural Network Synchronization Control for Uncertain Fractional-Order Time-Delay Chaotic Systems. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Fang, Z.; Liu, H. Adaptive T-S Fuzzy Synchronization for Uncertain Fractional-Order Chaotic Systems with Input Saturation and Disturbance. Inf. Sci. 2024, 666, 120423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Luo, R.; Huang, M.; Fu, J. Practical Fixed Time Active Control Scheme for Synchronization of a Class of Chaotic Neural Systems with External Disturbances. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 157, 111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghvafard, H.; Erjaee, G.H. Phase and Anti-Phase Synchronization of Fractional Order Chaotic Systems via Active Control. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2011, 16, 4079–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, R.; Feng, Y.; Yan, D.; Oluwaseun Onasanya, B. Predefined-Time Sliding Mode Filtering Control of Memristor-Based Bao Hyper-Chaotic System. J. Vib. Control 2024, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Qu, S.; Tang, Q.; Du, X. Predefined-Time Sliding Mode Control for Synchronization of Uncertain Hyperchaotic System and Application. J. Vib. Control 2024, 10775463241228649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Vu, D.D.; Huang, S.-C.; Giap, V.N. Fixed-Time Supper Twisting Disturbance Observer and Sliding Mode Control for a Secure Communication of Fractional-Order Chaotic Systems. J. Vib. Control 2024, 30, 2568–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modiri, A.; Mobayen, S. Adaptive Terminal Sliding Mode Control Scheme for Synchronization of Fractional-Order Uncertain Chaotic Systems. ISA Trans. 2020, 105, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; Zhao, X.; Yang, R. Recurrent Neural Networks with Finite-Time Terminal Sliding Mode Control for the Fractional-Order Chaotic System with Gaussian Noise. Indian J. Phys. 2024, 98, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, P.-Y.; Jahanshahi, H.; Alcaraz, R.; Chu, Y.-M.; Gómez-Aguilar, J.F.; Alsaadi, F.E. Spectral Entropy Analysis and Synchronization of a Multi-Stable Fractional-Order Chaotic System Using a Novel Neural Network-Based Chattering-Free Sliding Mode Technique. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 144, 110576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, M.; Zhang, J.; Iu, H.H.-C.; Yao, R.; Bai, L. A Novel Intermittent Sliding Mode Control Approach to Finite-Time Synchronization of Complex-Valued Neural Networks. Neurocomputing 2022, 513, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zang, H.; Bai, L. A New Predefined-Time Sliding Mode Control Scheme for Synchronizing Chaotic Systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 164, 112745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.A.; Osorio, M. Strict Lyapunov Functions for the Super-Twisting Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 2012, 57, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, C.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. Adaptive Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Control for Robot Manipulators with Input Saturation. Sensors 2024, 24, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Jahanshahi, H.; Bekiros, S.; Bezzina, F.; Chu, Y.-M.; Aly, A.A. Deep Recurrent Neural Networks with Finite-Time Terminal Sliding Mode Control for a Chaotic Fractional-Order Financial System with Market Confidence. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 146, 110881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Finite-Time Synchronization of Fractional Multi-Wing Chaotic System. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 115224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Luo, R.; Fu, J.; Huang, M. Fixed Time Control and Synchronization of a Class of Uncertain Chaotic Systems with Disturbances via Passive Control Method. Math. Comput. Simul. 2022, 198, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Li, L.; Cao, P.; He, Y. A Fixed-Time Robust Controller Based on Zeroing Neural Network for Generalized Projective Synchronization of Chaotic Systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 169, 113279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assali, E.A. Predefined-Time Synchronization of Chaotic Systems with Different Dimensions and Applications. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 147, 110988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wan, Y.; Cao, J. Predefined-Time Synchronization for FitzHugh-Nagumo Neural Networks With External Disturbances and Multiple Time Scales: An Adaptive Control Approach. In IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jian, J. Predefined-Time Synchronization of Fractional-Order Memristive Competitive Neural Networks with Time-Varying Delays. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 174, 113790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, M. Linear Models of Dissipation Whose Q Is Almost Frequency Independent—II. Geophys. J. Int. 1967, 13, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations; Elsevier Science and Technology: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Monje, C.A.; Chen, Y.; Vinagre, B.M.; Xue, D.; Feliu-Batlle, V. Fractional-Order Systems and Controls: Fundamentals and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84996-335-0. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, G.; Hu, J. Fixed/Predefined-Time Projective Synchronization for a Class of Fuzzy Inertial Discontinuous Neural Networks with Distributed Delays. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2024, 483, 108925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, W.; Yu, W. The Lag Projective (Anti-)Synchronization of Chaotic Systems with Bounded Nonlinearity via an Adaptive Control Scheme. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2013, 2013, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Xiao, J. Novel Predefined-time Control for Fractional-order Systems and Its Application to Chaotic Synchronization. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2024, 47, 5427–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Liu, S.; Song, Z.; Zhang, F. Fixed-Time Control of a Class of Fractional-Order Chaotic Systems via Backstepping Method. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 167, 113076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazi, A.S.; Matouk, A.E. Dynamical Behaviors and Synchronization in the Fractional Order Hyperchaotic Chen System. Appl. Math. Lett. 2011, 24, 1938–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liang, C.; Wu, Q.; Yuan, H. A New Fractional-Order Hyperchaotic System and Its Modified Projective Synchronization. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2015, 76, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, L.; Sun, K. Chaos Synchronization between Two Different Fractional-Order Hyperchaotic Systems. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2011, 16, 2628–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Xi, Z. New Predefined Time Sliding Mode Control Scheme for Multi-Switch Combination–Combination Synchronization of Fractional-Order Hyperchaotic Systems. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030147

Zhang H, Xi Z. New Predefined Time Sliding Mode Control Scheme for Multi-Switch Combination–Combination Synchronization of Fractional-Order Hyperchaotic Systems. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(3):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030147

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hailong, and Zhaojun Xi. 2025. "New Predefined Time Sliding Mode Control Scheme for Multi-Switch Combination–Combination Synchronization of Fractional-Order Hyperchaotic Systems" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 3: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030147

APA StyleZhang, H., & Xi, Z. (2025). New Predefined Time Sliding Mode Control Scheme for Multi-Switch Combination–Combination Synchronization of Fractional-Order Hyperchaotic Systems. Fractal and Fractional, 9(3), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9030147