Review of Bioinspired Composites for Thermal Energy Storage: Preparation, Microstructures and Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

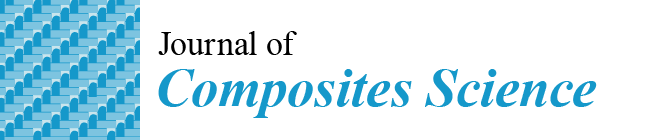

2. Bioinspired Structures for Thermal Energy Storage

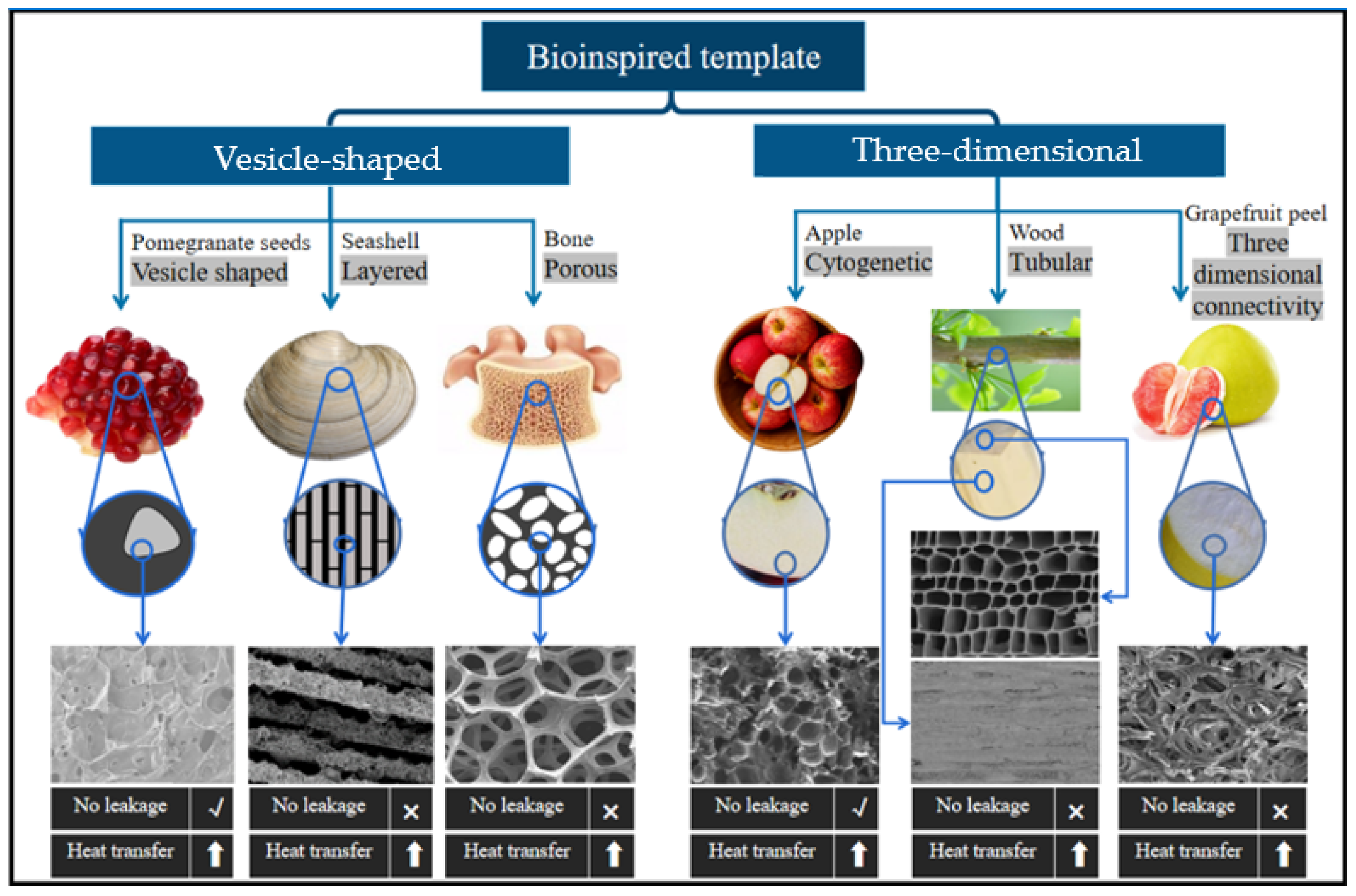

3. Preparation Process of Bioinspired Composites for Thermal Energy Storage

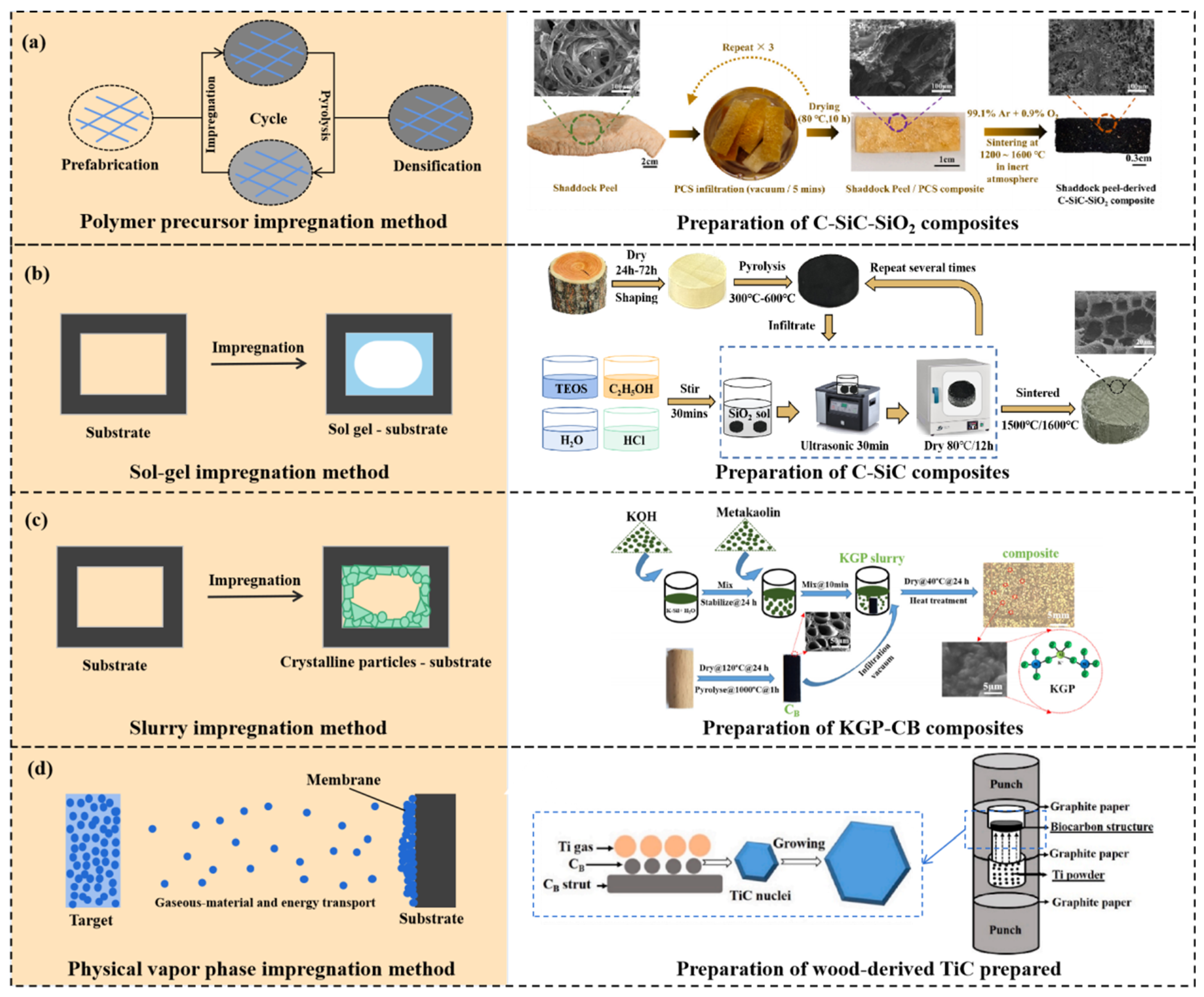

3.1. Processing of Skeleton Materials

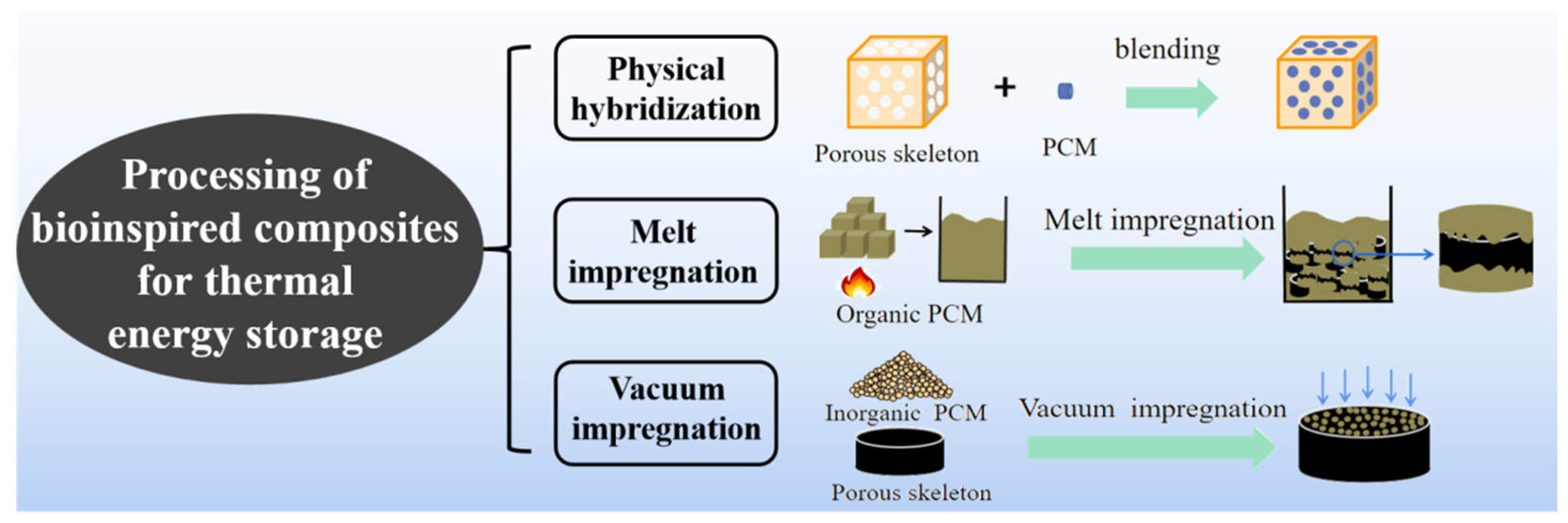

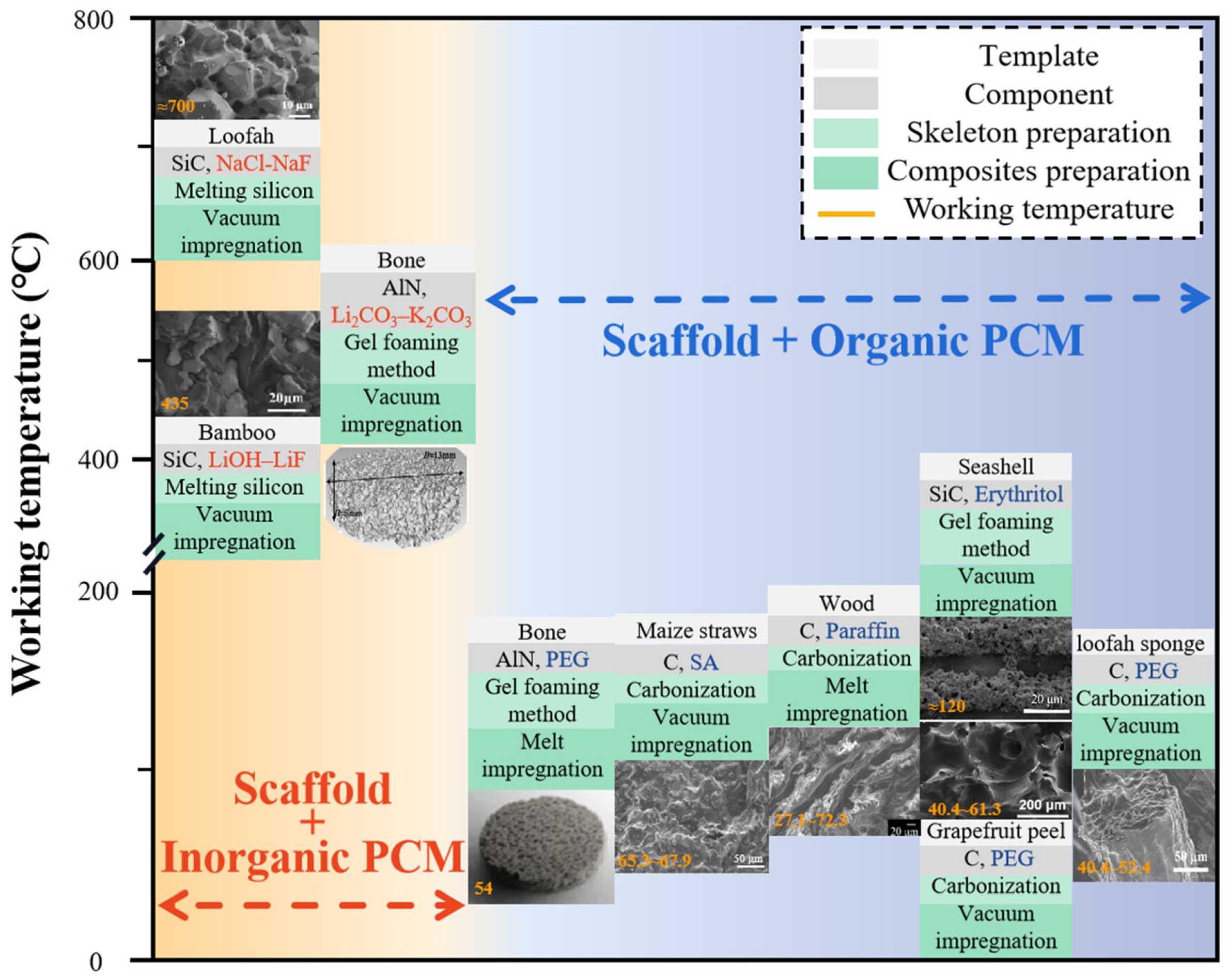

3.2. Processing of Bioinspired Composites for Thermal Energy Storage

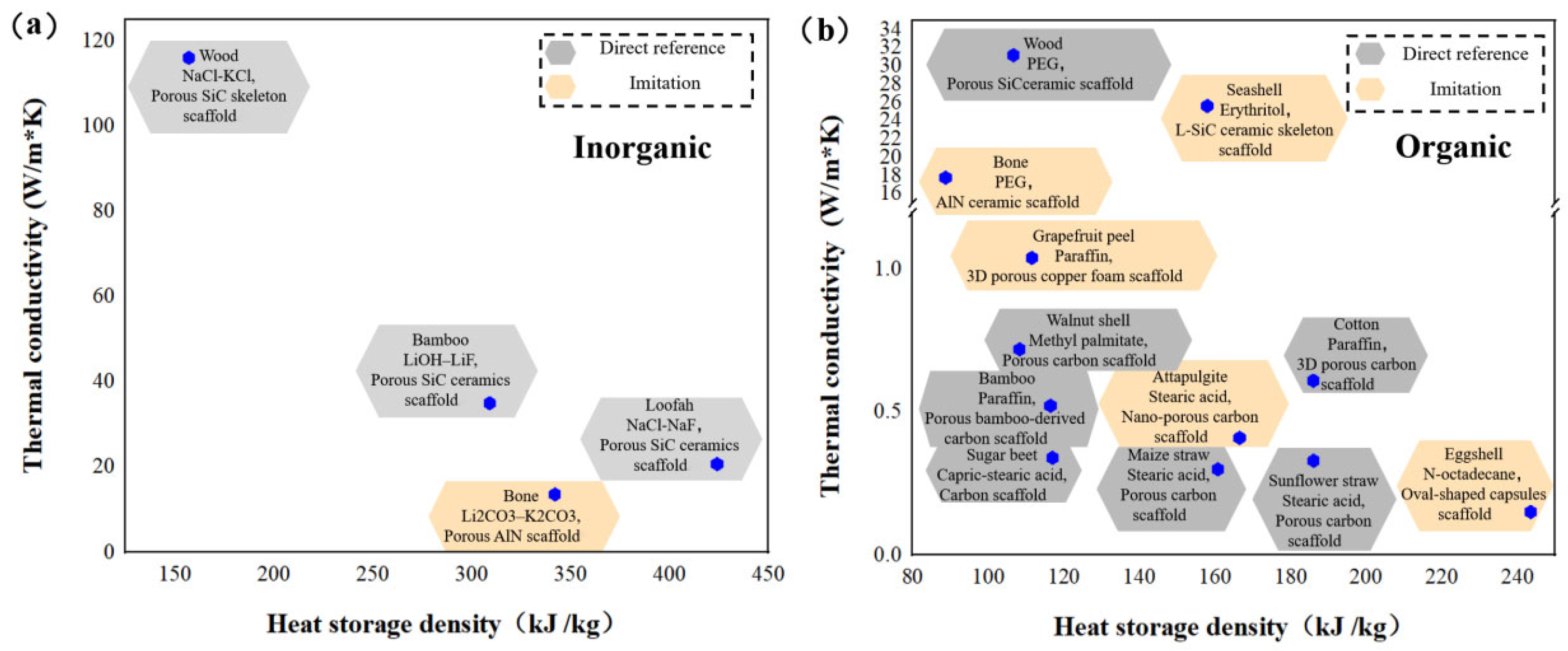

4. Properties of Bioinspired Composites for Thermal Energy Storage

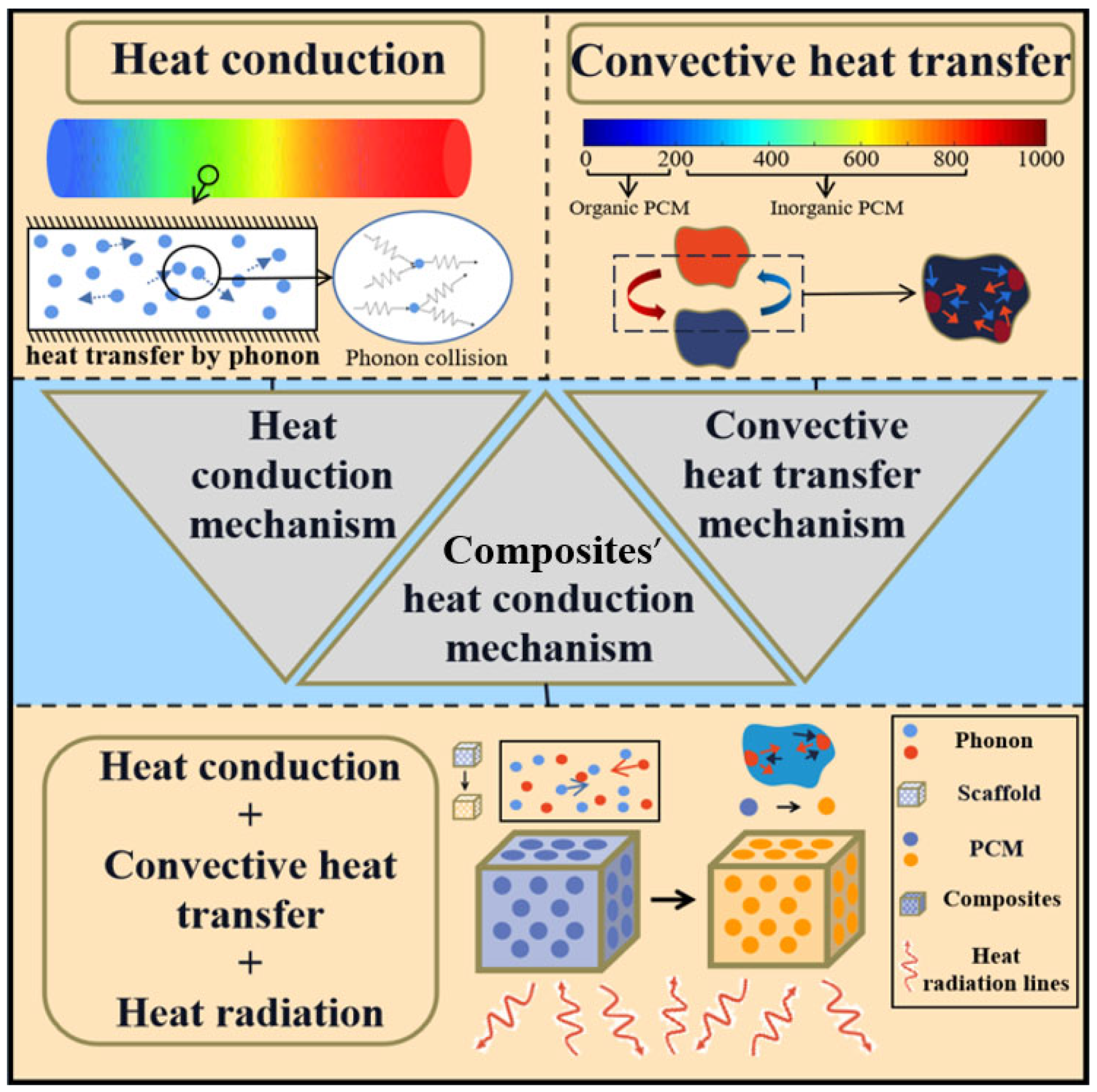

4.1. Thermal Conductivity Mechanism of Materials

4.2. Thermal Energy Storage Performance

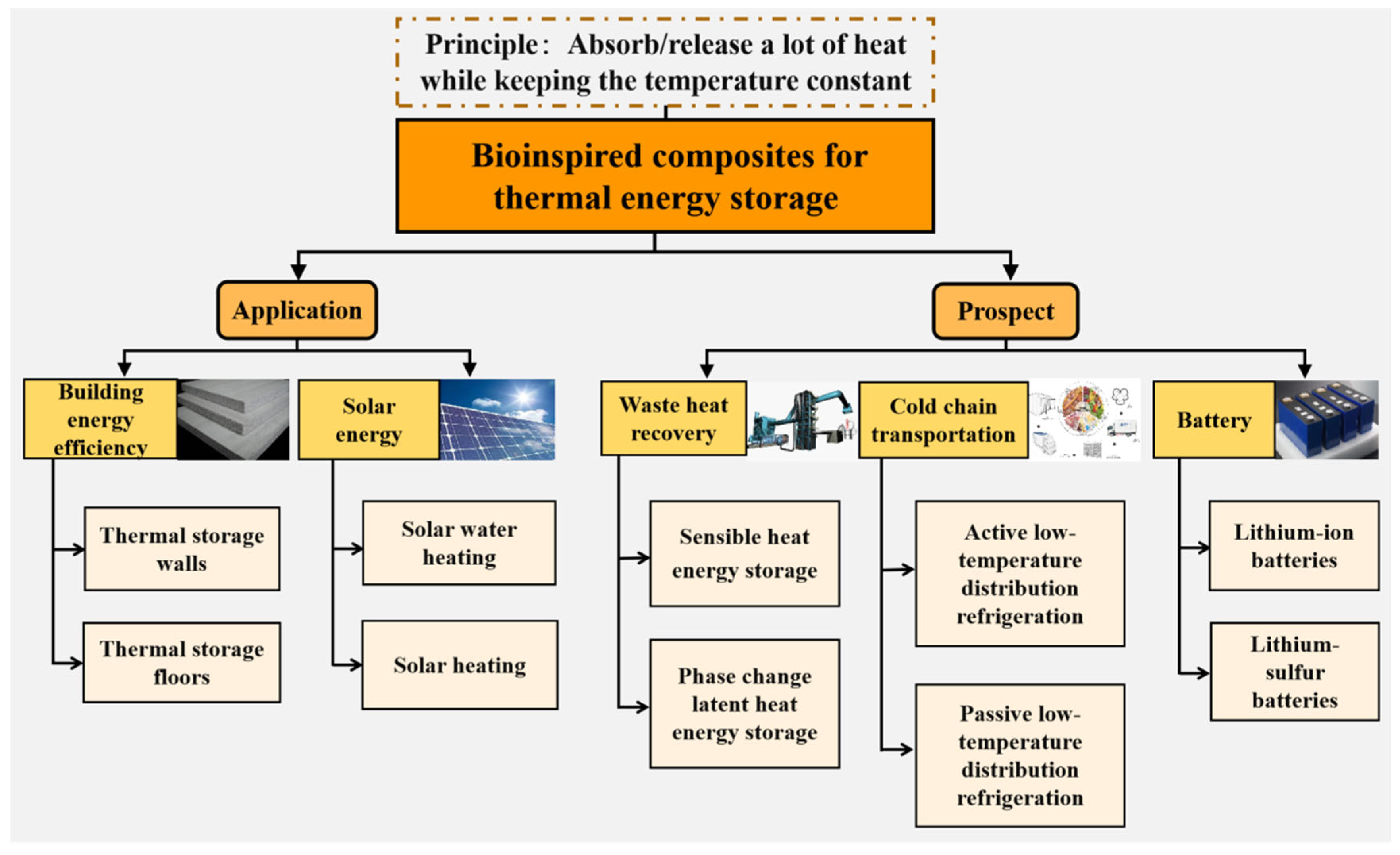

5. Applications

6. Conclusions and Outlook

- The skeleton preparation process of these bioinspired composites for thermal energy storage is meticulous, and how to simplify the preparation process so that it can be used on a large scale still needs to be explored.

- Most bioinspired composites for thermal energy storage cannot meet the rapid energy transfer and efficient energy storage demands at the same time.

- Nowadays, most bioinspired thermal energy storage composites are small disc types or elliptical spheres, while large-sized materials with good performance need to be further investigated.

- The research of bioinspired composites for thermal energy storage is at early stage, and their applications are mostly in the stage of laboratory verification. Energy storage efficiency, lifespan, cost and technology maturity still need to be further verified and improved.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jouhara, H.; Żabnieńska-Góra, A.; Khordehgah, N.; Ahmad, D.; Lipinski, T. Latent thermal energy storage technologies and applications: A review. Int. J. Thermofluids 2020, 5–6, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, A.; Barreneche, C.; Navarro, M.E.; Ding, Y. Thermal energy storage technologies for concentrated solar power—A review from a materials perspective. Renew. Energy 2020, 156, 1244–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Gu, H.; Zhang, M.; Huang, A.; Chen, D.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J. Preparation and characterization of a heat storage ceramic with Al-12 wt% Si as the phase change material. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 28042–28052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Yan, J.; Li, M.; Tao, Z.; Yang, M.; Wang, G. High thermal conductive shape-stabilized phase change materials based on water-borne polyurethane/boron nitride aerogel. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 8945–8951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasim, S.; Dastager, S.G.; Alahmdi, M.I.; Hamdalla, T.A.; Panneerselvam, C.; Makandar, M.B. Novel Biogenic Synthesis of Pd/TiO@BC as an electrocatalytic and possible energy storage materials. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 15874–15883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Su, H.; Huang, Z.; Lin, P.; Yin, T.; Sheng, X.; Chen, Y. Biomass-based phase change material gels demonstrating solar-thermal conversion and thermal energy storage for thermoelectric power generation and personal thermal management. Sol. Energy 2022, 239, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, G.; Du, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Cui, X.; Cui, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, T. A novel composite for thermal energy storage from alumina hollow sphere/paraffin and alkali-activated slag. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 15947–15957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, M.M.; Zhang, Y.; Iqbal, K.; Zhang, S.; Tang, B. Novel strategies and supporting materials applied to shape-stabilize organic phase change materials for thermal energy storage–A review. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 846–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Chen, H.; Du, X.; Shi, T.; Zhang, D. Preparation and Performance Analysis of Form-Stable Composite Phase Change Materials with Different EG Particle Sizes and Mass Fractions for Thermal Energy Storage. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 34436–34448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Jing, R.; Wu, B.; Xu, F.; Sun, L.; Xia, Y.; Rosei, F.; Peng, H.; et al. Shape-stabilized phase change composites enabled by lightweight and bio-inspired interconnecting carbon aerogels for efficient energy storage and photo-thermal conversion. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 13556–13569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mu, W.; Wang, C.; Sun, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, A. Carbonized clay pectin-based aerogel for light-to-heat conversion and energy storage. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 224, 106524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Shen, Y.; Yang, B.; Lv, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y. Polyethylene glycol / nanofibrous Kevlar aerogel composite: Fabrication, confinement effect, thermal energy storage and insulation performance. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 104011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Xie, D.; Yin, L.; Gong, K.; Zhou, K. Influences of reduction temperature on energy storage performance of paraffin wax/graphene aerogel composite phase change materials. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, Y.; Feng, F.; Tong, Q.; Qv, W.; Wang, H. Microstructure and thermal properties of a paraffin/expanded graphite phase-change composite for thermal storage. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 1339–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, D.; Fei, H.; Xu, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Ye, W. Preparation and properties of lauric acid-octadecanol/expanded graphite shape-stabilized phase change energy storage material. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, H.; Gao, H.; Wang, X.; Ma, B. Effects of porous silicon carbide supports prepared from pyrolyzed precursors on the thermal conductivity and energy storage properties of paraffin-based composite phase change materials. J. Energy Storage 2022, 56, 106046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gao, L.; Liu, M.; Xia, S.; Han, Y. Self-crystallization behavior of paraffin and the mechanism study of SiO2 nanoparticles affecting paraffin crystallization. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekimoğlu, G.; Sarı, A. A review on phase change materials (PCMs) for thermal energy storage implementations. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 58, 1360–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Tyagi, V.V.; Chen, C.R.; Buddhi, D. Review on thermal energy storage with phase change materials and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 318–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Stonehouse, A.; Abeykoon, C. Encapsulation methods for phase change materials—A critical review. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 200, 123458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Min, X.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.g.; Wu, X.; Fang, M. Honeycomb-like structured biological porous carbon encapsulating PEG: A shape-stable phase change material with enhanced thermal conductivity for thermal energy storage. Energy Build. 2018, 158, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Arco, L.; Poma, A.; Ruiz-Perez, L.; Scarpa, E.; Ngamkham, K.; Battaglia, G. Molecular bionics—Engineering biomaterials at the molecular level using biological principles. Biomaterials 2019, 192, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, D.; Kang, S.; Adstedt, K.M.; Kanhaiya, K.; Bockstaller, M.R.; Brinson, L.C.; Buehler, M.J.; Coveney, P.V.; Dayal, K.; El-Awady, J.A.; et al. Hierarchically structured bioinspired nanocomposites. Nat. Mater. 2023, 22, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Navarro Rivero, M.E.; Liu, X.; She, X.; Xuan, Y.; Ding, Y. A novel composite phase change material for medium temperature thermal energy storage manufactured with a scalable continuous hot-melt extrusion method. Appl. Energy 2021, 303, 117591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H.; Chen, D. Enhanced thermal conductivity of form-stable composite phase-change materials with graphite hybridizing expanded perlite/paraffin. Sol. Energy 2020, 209, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, R.; Parameshwaran, R.; Vinayaka Ram, V.; Srinivas, P.V. Bio-based hexadecanol impregnated fly-ash aggregate as novel shape stabilized phase change material for solar thermal energy storage. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 56, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Han, T.; Zhang, M.; Cheng, D.; Zhai, M.; Zhou, P.; Li, J. A Bio-Inspired Structurally-Responsive and Polysulfides-Mobilizable Carbon/Sulfur Composite as Long-Cycling Life Li−S Battery Cathode. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 3966–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Fei, H.; Zhou, J.; Liang, X.; Pan, Y. Utilization of carbonized water hyacinth for effective encapsulation and thermal conductivity enhancement of phase change energy storage materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 372, 130841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, D.; Zuo, X.; Tang, A.; Yang, H. Nano-porous carbon-enabled composite phase change materials with high photo-thermal conversion performance for multi-function coating. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 248, 112025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Kou, Y.; Dong, H.; Ye, S.; Zhao, D.; Liu, J.; Shi, Q. The design of phase change materials with carbon aerogel composites for multi-responsive thermal energy capture and storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liang, W.; Tang, Z.; Jia, J.; Liu, F.; Yang, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, A. Enhanced light-thermal conversion efficiency of mixed clay base phase change composites for thermal energy storage. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 189, 105535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.; Zhang, W.; Lv, Z.; Huang, Z.; Gao, W. A novel composite Phase change material of Stearic Acid/Carbonized sunflower straw for thermal energy storage. Mater. Lett. 2018, 215, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhu, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Gao, W. Enhanced thermal properties of stearic acid/carbonized maize straw composite phase change material for thermal energy storage in buildings. J. Energy Storage 2021, 36, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarı, A.; Hekimoğlu, G.; Karabayır, Y.; Sharma, R.K.; Arslanoğlu, H.; Gencel, O.; Tyagi, V.V. Capric-stearic acid mixture impregnated carbonized waste sugar beet pulp as leak-resistive composite phase change material with effective thermal conductivity and thermal energy storage performance. Energy 2022, 247, 123501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, J.; Chai, Z.; Zhang, B.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y. High thermal conductivity and high energy density compatible latent heat thermal energy storage enabled by porous Al2O3@Graphite ceramics composites. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 19864–19872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Luvnish, A.; Su, X.; Meng, Q.; Liu, M.; Kuan, H.; Saman, W.; Bostrom, M.; Ma, J. Advancements in polymer (Nano)composites for phase change material-based thermal storage: A focus on thermoplastic matrices and ceramic/carbon fillers. Smart Mater. Manuf. 2024, 2, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zhang, G.-j.; Saunders, T. Wood-derived ultra-high temperature carbides and their composites: A review. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 5536–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-Q.; Yu, M.; Luo, H.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Fu, R.-L.; Gucci, F.; Saunders, T.; Zhu, K.-J.; Zhang, D. Low-temperature thermally modified fir-derived biomorphic C–SiC composites prepared by sol-gel infiltration. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 9523–9533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, D.; Yuan, G. Bioinspired mineralized wood hydrogel composites with flame retardant properties. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegst, U.G.; Bai, H.; Saiz, E.; Tomsia, A.P.; Ritchie, R.O. Bioinspired structural materials. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, G.; Saunders, T. Biomorphic wood-derived titanium carbides prepared by physical vapor infiltration-reaction synthesis. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 11459–11464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Qi, X.-d.; Huang, T.; Tang, C.-y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y. Preparation and application of three-dimensional filler network towards organic phase change materials with high performance and multi-functions. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 419, 129620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.H.; Hazell, P.J.; Wang, H.; Escobedo, J.P.; Ameri, A.A.H. Lessons from nature: 3D printed bio-inspired porous structures for impact energy absorption—A review. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 58, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-Q.; Yu, M.; Lin, G.-W.; Wang, Y.-L.; Yang, L.-X.; Liu, J.-X.; Gucci, F.; Zhang, G.-J. Enhanced strength and thermal oxidation resistance of shaddock peel-polycarbosilane-derived C–SiC–SiO2 composites. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 27516–27526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Bernardo, E.; Colombo, P.; Romero, A.R.; Tatarko, P.; Kannuchamy, V.K.; Titirici, M.-M.; Castle, E.G.; Picot, O.T.; Reece, M.J. Preparation and properties of biomorphic potassium-based geopolymer (KGP)-biocarbon (CB) composite. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 12957–12964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihan, E.; Berent, H.K.; Demir, H.; Öztop, H.F. Entropy analysis and thermal energy storage performance of PCM in honeycomb structure: Effects of materials and dimensions. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2023, 38, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wei, Q.; Cai, Y. Dual-encapsulated multifunctional phase change composites based on biological porous carbon for efficient energy storage and conversion, thermal management, and electromagnetic interference shielding. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Feng, L.; Li, W.; Zheng, J.; Tian, W.; Li, X. Shape-stabilized phase change materials based on polyethylene glycol/porous carbon composite: The influence of the pore structure of the carbon materials. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2012, 105, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sharma, R.K.; Khalid, M.; Goyal, R.; Sarı, A.; Tyagi, V.V. Evaluation of carbon based-supporting materials for developing form-stable organic phase change materials for thermal energy storage: A review. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 246, 111896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Jia, Y.; Alva, G.; Fang, G. Review on thermal conductivity enhancement, thermal properties and applications of phase change materials in thermal energy storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2730–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S. Application and research progress of phase change energy storage in new energy utilization. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 343, 117554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, S.; Samimifar, M.; Doranehgard, M.H.; Li, L. Organic Phase Change Materials. Encycl. Smart Mater. 2020, 2, 441–449. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Al-Sulaiman, F.A.; Ibrahim, N.I.; Zahir, M.H.; Al-Ahmed, A.; Saidur, R.; Yılbaş, B.S.; Sahin, A.Z. A review on current status and challenges of inorganic phase change materials for thermal energy storage systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielichowska, K.; Pielichowski, K. Phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 65, 67–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greil, P.; Lifka, T.; Kaindl, A. Biomorphic Cellular Silicon Carbide Ceramics from Wood: I. Processing and Microstructure. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 1998, 18, 1961–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, N.; Ning, Y.-H.; Hu, P.; Feng, Y.; Li, Q.; Lin, C.-H.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Zeng, J.-L. Silica-confined composite form-stable phase change materials: A review. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 7077–7097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Liu, X.; Luo, Q.; Tian, Y.; Dang, C.; Yao, H.; Song, C.; Xuan, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ding, Y. Loofah-derived eco-friendly SiC ceramics for high-performance sunlight capture, thermal transport, and energy storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 45, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Feng, Y.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, X. Evaluation of thermal performance for bionic porous ceramic phase change material using micro-computed tomography and lattice Boltzmann method. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 179, 107621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, M.; Xu, Q.; Gao, K.; Dang, C.; Li, P.; Luo, Q.; Zheng, H.; Song, C.; Tian, Y.; et al. Bamboo derived SiC ceramics-phase change composites for efficient, rapid, and compact solar thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 240, 111726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Liu, X.; Luo, Q.; Song, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, M.; Xuan, Y.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y. Bifunctional biomorphic SiC ceramics embedded molten salts for ultrafast thermal and solar energy storage. Mater. Today Energy 2021, 21, 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyed Afghahi, S.S.; Golestani Fard, M.A. Design and synthesis of a novel core-shell nanostructure developed for thermal energy storage purposes. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 15866–15875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, S.; Yin, Z.; Shi, W.; Tao, M.; Liu, W.; Gao, Z.; Ma, C. Foam-gelcasting preparation and properties of high-strength mullite porous ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 6873–6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Yan, K.; Feng, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X. Bionic hierarchical porous aluminum nitride ceramic composite phase change material with excellent heat transfer and storage performance. Compos. Commun. 2021, 27, 100892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Song, Y.; Xu, Q.; Luo, Q.; Tian, Y.; Dang, C.; Wang, H.; Chen, M.; Xuan, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Nacre-like ceramics-based phase change composites for concurrent efficient solar-to-thermal conversion and rapid energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2021, 230, 111240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, A.; Shuai, Y. Experimental and numerical study on flow characteristic and thermal performance of macro-capsules phase change material with biomimetic oval structure. Energy 2022, 238, 121830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Liu, Y.; Dong, S.; Wang, J. Study on novel molten salt-ceramics composite as energy storage material. J. Energy Storage 2020, 28, 101237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hua, W. Review of preparation technologies of organic composite phase change materials in energy storage. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 336, 115923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnasamy, V.; Heo, J.; Jung, S.; Lee, H.; Cho, H. Shape stabilized phase change materials based on different support structures for thermal energy storage applications–A review. Energy 2023, 262, 125463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Geng, Y.; Liao, Y.; Chen, S.; Sun, K.; Li, M. Shape-stable phase change composites based on carbonized waste pomelo peel for low-grade thermal energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2022, 47, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Hu, Y.; Feng, D.; He, Y.; Yan, Y. Magnetically-accelerated photo-thermal conversion and energy storage based on bionic porous nanoparticles. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 217, 110681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhou, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, D. High latent heat and recyclable form-stable phase change materials prepared via a facile self-template method. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 396, 125265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Xi, S.; Xie, H.; Yu, W. 3D porous copper foam-based shape-stabilized composite phase change materials for high photothermal conversion, thermal conductivity and storage. Renew. Energy 2021, 175, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Han, W.; Ge, C.; Guan, H.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X. Form-stable oxalic acid dihydrate/glycolic acid-based composite PCMs for thermal energy storage. Renew. Energy 2019, 136, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhao, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, R.; Sheng, N.; Rao, Z. Anisotropically thermal transfer improvement and shape stabilization of paraffin supported by SiC-coated biomass carbon fiber scaffolds for thermal energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2022, 46, 103866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Liu, X.; Luo, Q.; Yao, H.; Wang, J.; Lv, S.; Dang, C.; Tian, Y.; Xuan, Y. Eco-friendly and large porosity wood-derived SiC ceramics for rapid solar thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2023, 251, 112174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Qiu, C.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, C.; Fan, M.; Wu, Y.; Sun, W.; Guo, X. Biomimetic bone tissue structure: An ultrastrong thermal energy storage wood. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 457, 141351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; He, H.; Wang, Y.; Shao, L.; Wang, Q.; Wei, Q.; Cai, Y. Shape-stabilized phase change composites supported by biomass loofah sponge-derived microtubular carbon scaffold toward thermal energy storage and electric-to-thermal conversion. J. Energy Storage 2022, 56, 105891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Zhang, R.; Jin, X.; Zhang, X.; Bao, G.; Qin, D. Bamboo-derived phase change material with hierarchical structure for thermal energy storage of building. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekimoğlu, G.; Sarı, A.; Kar, T.; Keleş, S.; Kaygusuz, K.; Tyagi, V.V.; Sharma, R.K.; Al-Ahmed, A.; Al-Sulaiman, F.A.; Saleh, T.A. Walnut shell derived bio-carbon/methyl palmitate as novel composite phase change material with enhanced thermal energy storage properties. J. Energy Storage 2021, 35, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, G.; Ghafoor, M.A.; Yousaf, M.; Imran, M.; Zaman, M.; Elkamel, A.; Haq, A.; Rizwan, M.; Wilberforce, T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; et al. Low temperature phase change materials for thermal energy storage: Current status and computational perspectives. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 50, 101808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira da Cunha, J.; Eames, P. Thermal energy storage for low and medium temperature applications using phase change materials—A review. Appl. Energy 2016, 177, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, Q.; Lu, X.; Ge, R.; Du, Y.; Xiong, Y. Inorganic salt based shape-stabilized composite phase change materials for medium and high temperature thermal energy storage: Ingredients selection, fabrication, microstructural characteristics and devel-opment, and applications. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Shi, B.; Jiang, M.; Fu, B.; Song, C.; Tao, P.; Shang, W.; Deng, T. Biological and Bioinspired Thermal Energy Regulation and Utilization. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 7081–7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; He, J.; Rai, A.; Hun, D.; Shrestha, S. Size Effects in the Thermal Conductivity of Amorphous Polymers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2020, 14, 44023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Feng, D.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, X. Enhanced thermal energy storage of sodium nitrate by graphene nanosheets: Experimental study and mechanisms. J. Energy Storage 2022, 54, 105294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.-X.; Zhu, C.-Y.; Huang, B.-H.; Duan, X.-Y.; Gong, L.; Xu, M.-H. Thermal behaviors and performance of phase change materials embedded in sparse porous skeleton structure for thermal energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Deng, Y.; Wu, F.; Wang, H. Effect of functional modification of porous medium on phase change behavior and heat storage characteristics of form-stable composite phase change materials: A critical review. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Paz, A.M.; Cañon-Davila, D.F.; Londoño-Restrepo, S.M.; Jimenez-Mendoza, D.; Pfeiffer, H.; Ramírez-Bon, R.; Rodriguez-Garcia, M.E. Fabrication and characterization of bioinspired nanohydroxyapatite scaffolds with different porosities. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 32173–32184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Fang, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, B.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, H. High interface compatibility and phase change enthalpy of heat storage wood plastic composites as bio-based building materials for energy saving. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tang, Y.; Zuo, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H. Preparation of hierarchical porous microspheres composite phase change material for thermal energy storage concrete in buildings. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 232, 106771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Ji, J.; Zhang, X. Research progress of phase change cold energy storage materials used in cold chain logistics of aquatic products. J. Energy Storage 2023, 60, 106568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Peng, H. Polyurethane foam based composite phase change microcapsules with reinforced thermal conductivity for cold energy storage. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 652, 129875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; He, H.; Li, J.-h.; He, H.; Chen, S.; Deng, C. Waste sugarcane skin-based composite phase change material for thermal energy storage and solar energy utilization. Mater. Lett. 2023, 342, 134320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Biomimetic Straw-Like Bundle Cobalt-Doped Fe2 O3 Electrodes towards Superior Lithium-Ion Storage. Chemistry 2019, 25, 3343–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Tao, M.; Jia, Y.; Hou, B.; Wang, X. Cabbage-like nitrogen-doped graphene/sulfur composite for lithium-sulfur batteries with enhanced rate performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 753, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Publication Year | Materials and Structures (Porosity, Pore Size) | Preparation Process | Performance | Application Temperature (°C) | Application System | Geometric Dimensions (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Storage Density (kJ/kg): | Thermal Conductivity (W/m*K): | Leakage: | Number of Cycles: | ||||||

| Dong, Yan 2022 [65] | n-octadecane Oval-shaped capsules | 3D printing | 243.5 | 0.1505 | No | / | / | solar thermal chemical reactions | Oval a = 50 b = 40 c = 30 |

| Shi, Lei 2020 [70] | paraffin@magneticTiO, paraffin@magneticFe3O4 | two-step method | 353.2 (PMF) 377.6 (PMT) | >0.55 (PMF) >0.18 (PMT) | / | / | 88.6 (PMF) 94.2 (PMT) | solar direct absorption collectors | Globosity D = (1~2) × 10−4 |

| Feng, Guangpeng 2022 [58] | Li2CO3–K2CO3, porous aluminum nitride biomorphic porous (55%) | Gel foaming method | 342 | 13.6 | No | / | / | / | Disc-shaped D = 13 H = 5 |

| Li, Shaowei 2022 [70] | polyethylene glycol (PEG), Carbonized grapefruit peel [100 μm(pipeline), 3.91 nm(Mesoporous)] | Vacuum impregnation | 162.4 | / | No | >200 | 40.4~ 61.3 | solar thermal conversion and thermoelectric conversion | Cuboid |

| Tan, Yunzhi 2020 [71] | polyethylene glycol (PEG) spherulite crystals, Crosslinked polymer (CPA) | In situ polymerization | 188.8 | / | No | >100 | 60.2 | Energy-saving and insulation of buildings and waste heat utilization of factories | Vesicle-like |

| Qiu, Lin 2021 [63] | polyethylene glycol (PEG), aluminium nitride (AlN) ceramic (<500 μm) | Gel foaming method | 88.73 | 17.16 | / | / | 54.75 | solar power stations, industrial waste heat recovery | Disc-shaped D = 12 |

| Zhang, Hongyun 2021 [72] | Paraffin, copper foam, carbon material (graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide) (95%, 100~300 μm) | Vacuum impregnation and physical blending | 111.53 | 1.04 | No | / | 57.96~ 59.5 | Solar energy absorption and storage | Disc-shaped D = 12 |

| Wang, Jie 2019 [73] | oxalic acid dihydrate/glycolic acid, hydrothermal carbon | Physical blending | 318.8 | 1.3867 | No | >101 | 72 | low temperature architecturalthermal applications | / |

| Xu, Qiao 2022 [57] | NaCl-NaF, porous SiC ceramics (64–87%) | Molten silicon, Melting impregnation | 424 | 20.7 | No | >1000 | ≈700 | harvesting solar thermal energy | Disc-shaped |

| Xu, Q. 2021 [60] | NaCl-KCl molten salts, wood-like biomorphic porous SiC skeleton | Melting impregnation | 157 | 116 | / | / | / | harvest solar and thermal energy simultaneously | Disc-shaped D = 12.7 H = 3 |

| Liu, Xianglei 2022 [59] | LiOH–LiF, Porous Bamboo SiC ceramics (66~77%) | Vacuum impregnation | 309 | 35.0 | No | >2500 | 435 | High performance solar thermal conversion and storage | Disc-sedhap D = 18 |

| Liu, Xianglei 2021 [64] | Erythritol-TiN composite powder, L-SiC ceramic skeletons | Vacuum impregnation | 157.93 | 25.63 | No | / | ≈120 | Fast and efficient solar energy harvesting and thermal energy storage | Layered |

| Zhu, C 2022 [74] | Paraffin, 3D porous carbon scaffolds consisted of SiC-wrapped biomass carbon fibers | Vacuum impregnation | 186 | 0.61 | No | 100 | 27.1~ 72.3 | storage systems and advanced thermal management | Disc-shaped D = 20 H = 10 |

| Xu, Qiao 2023 [75] | PEG, porous SiC (80%) >100 μm | Molten silicon, Melting impregnation | 106.67 | 31.2 | No | >50 | 52~60 | environmentally friendly, and scalable route for efficient solar and thermal energy storage | Disc-shaped D = 12.7 H = 3 |

| Lin, Xianxian 2023 [76] | Polyurethane (PEG monomers:isophorone diisocyanate cross-linker 1:2) | Chemical modification, Vacuum impregnation | 116.1 | / | No | / | 32.4~ 54.4 | Directional load-bearing projects for energy conservation and temperature regulation in the automotive and building sectors | / |

| Wen, Ruilong 2021 [33] | Stearic acid Carbonized maize straw | Vacuum impregnation | 160.74 | 0.3 | No | 200 | 65.3~ 67.9 | Solar heat energy storage system and energy-efficient buildings | / |

| Wen, Ruilong 2018 [32] | Stearic acid Carbonized sunflower straw | Vacuum impregnation | 186.1 | 0.33 | / | / | 65.9~ 66.4 | Solar heat energy storage system and energy conservation buildings. | Disc-shaped |

| Tang, Yili 2022 [29] | Stearic acid Nano-porous carbon | Vacuum impregnation | 166.5 | 0.41 | No | 200 | 68~71.9 | Solar energy collection and storage | Disc-shaped |

| Sarı,Ahmet 2022 [34] | Capric-stearic acid eutectic Sugar beet pulp | Vacuum impregnation | 117 | 0.34 | No | 1000 | 23~24.5 | Temperature controlling of buildings | Diamonds |

| Song, Jiayin 2022 [77] | PEG, loofah sponge (3.9~4.7 nm) | Vacuum-assisted impregnation | 137.6 | / | No | >100 | 40.4~ 52.4 | Thermal management systems (intelligent and thermoregulated textiles and infrared stealth of military target) | Cylinder |

| Yue, Xianfeng 2023 [78] | Paraffin, porous bamboo-derived carbon (34%) | Chemical modification, Vacuum impregnation | 116.5 | 0.522 | No | >100 | 26~29 | Building temperature regulation | Disc-shaped |

| Hekimoğlu, Gökhan 2021 [79] | Methyl palmitate, walnut shell carbon | Chemical modification, Vacuum impregnation | 108.32 | 0.72 | No | 1000 | 26.27 | Solar thermal controlling of buildings | Disc-shaped |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, M.; Wang, M.; Xu, C.; Zhong, W.; Wu, H.; Lei, P.; Huang, Z.; Fu, R.; Gucci, F.; Zhang, D. Review of Bioinspired Composites for Thermal Energy Storage: Preparation, Microstructures and Properties. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9010041

Yu M, Wang M, Xu C, Zhong W, Wu H, Lei P, Huang Z, Fu R, Gucci F, Zhang D. Review of Bioinspired Composites for Thermal Energy Storage: Preparation, Microstructures and Properties. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Min, Mengyuan Wang, Changhao Xu, Wei Zhong, Haoqi Wu, Peng Lei, Zeya Huang, Renli Fu, Francesco Gucci, and Dou Zhang. 2025. "Review of Bioinspired Composites for Thermal Energy Storage: Preparation, Microstructures and Properties" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9010041

APA StyleYu, M., Wang, M., Xu, C., Zhong, W., Wu, H., Lei, P., Huang, Z., Fu, R., Gucci, F., & Zhang, D. (2025). Review of Bioinspired Composites for Thermal Energy Storage: Preparation, Microstructures and Properties. Journal of Composites Science, 9(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9010041