Multi-Indices Diagnosis of the Conditions That Led to the Two 2017 Major Wildfires in Portugal

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Indices Description

2.2.1. The Fire Weather Index (FWI)

2.2.2. The Continuous Haines Index (CHI)

2.2.3. NFDRS: Burning Index (BI), Energy Release Component (ERC), Spread Component (SC), and Ignition Component (IC)

2.2.4. The Keetch–Byram Drought Index (KBDI)

2.2.5. The Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI)

2.3. Datasets

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Methodological Framework

- in Section 3.2.1, a comparison between the spatial patterns of FWI, BI, and FFDI is presented. These indices are associated with fire intensity.

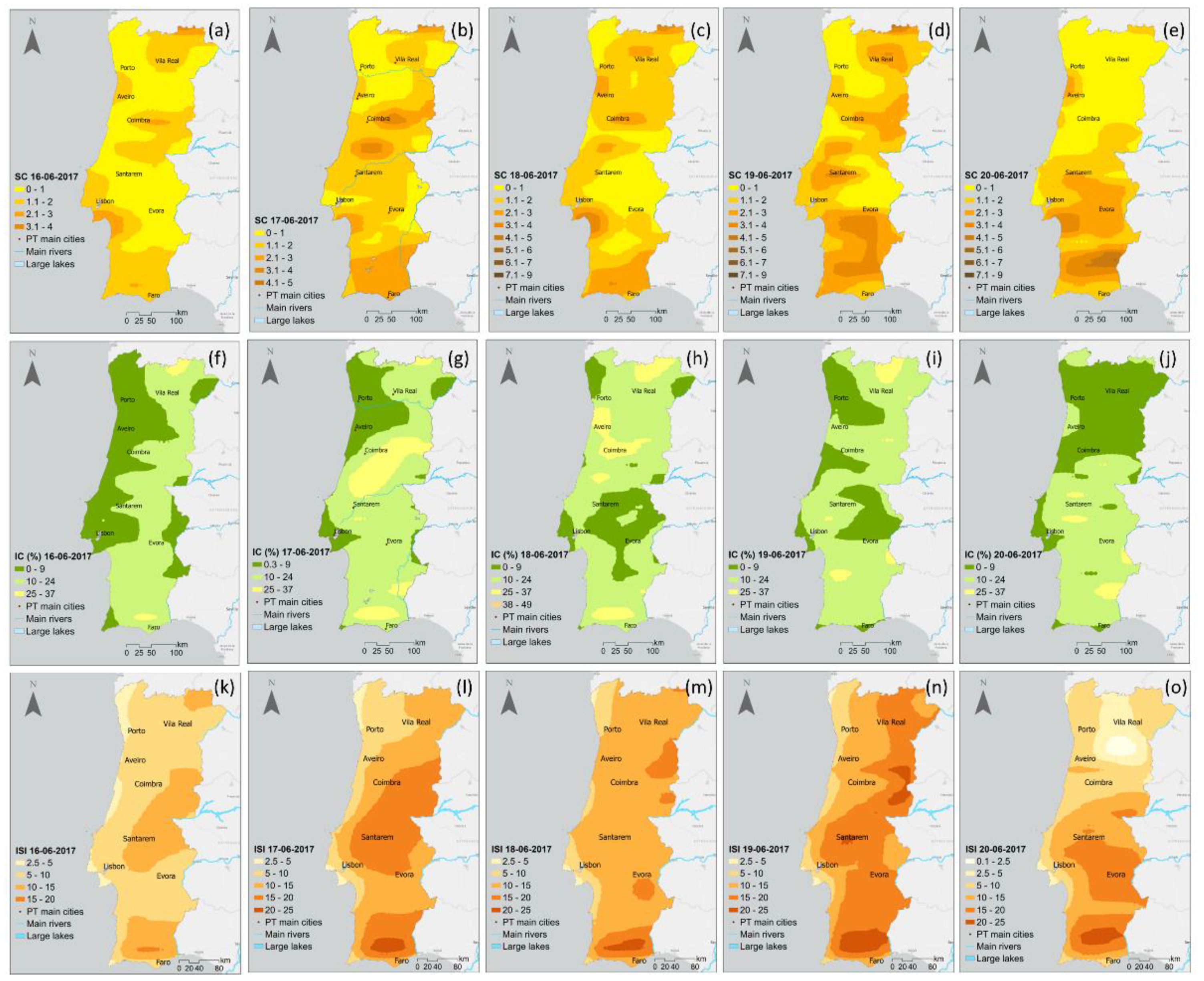

- in Section 3.2.2, the spatial patterns are presented and compared for the components with a daily scale variation, i.e., SC, ISI, associated with the spread of fires and IC with their ignition.

- in the next two sections, the indices with longer variation timescales

- o

- Section 3.2.3 KBDI which is associated with drought conditions.

- o

- Section 3.2.4 BUI and ERC linked to fuel weight availability to the flame front are analyzed.

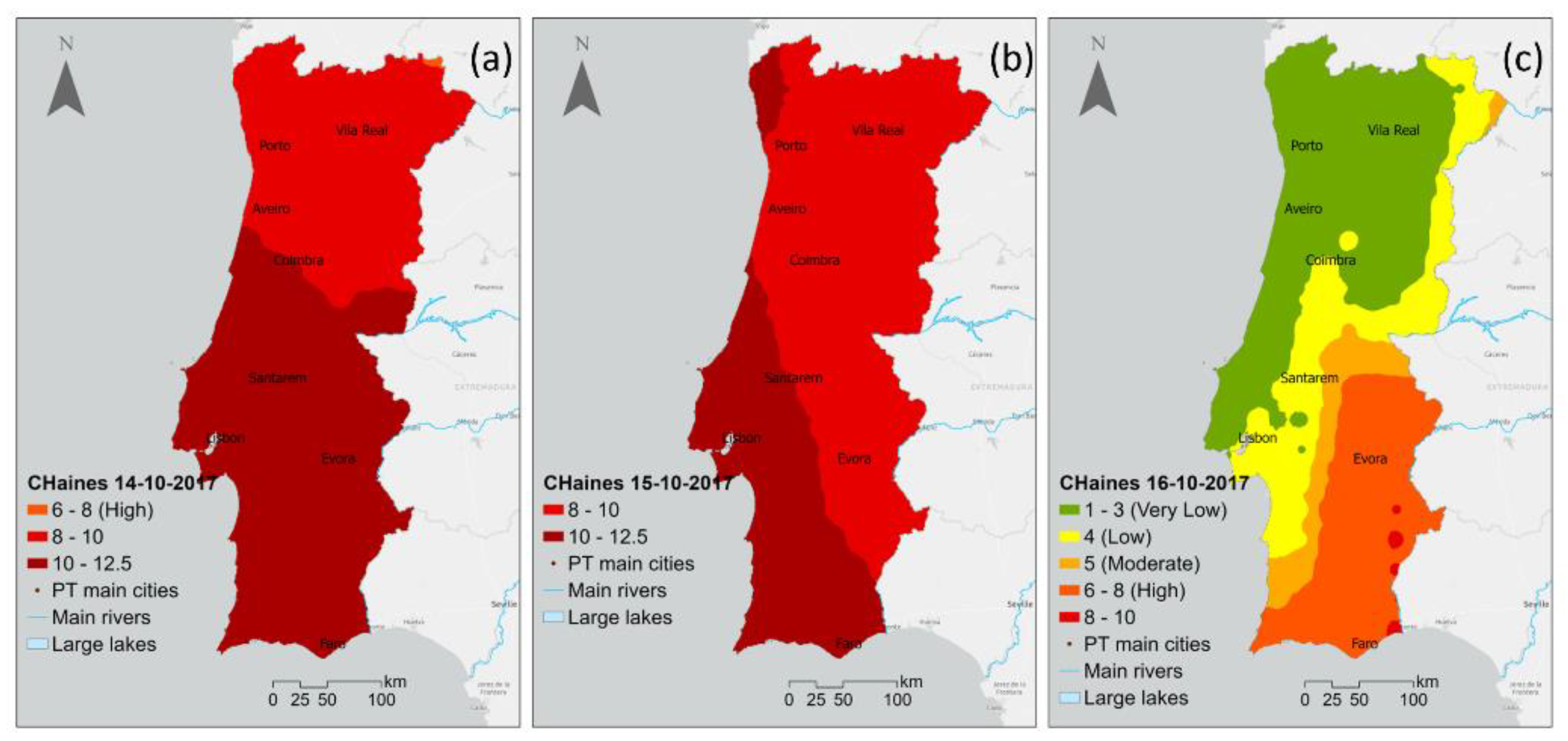

- in Section 3.2.5, the CHI daily spatial patterns for the two CEWEs are also shown. This index is related to the vertical atmospheric conditions.

3. Results

3.1. Monthly Mean Analysis

3.2. Daily Mean Analysis

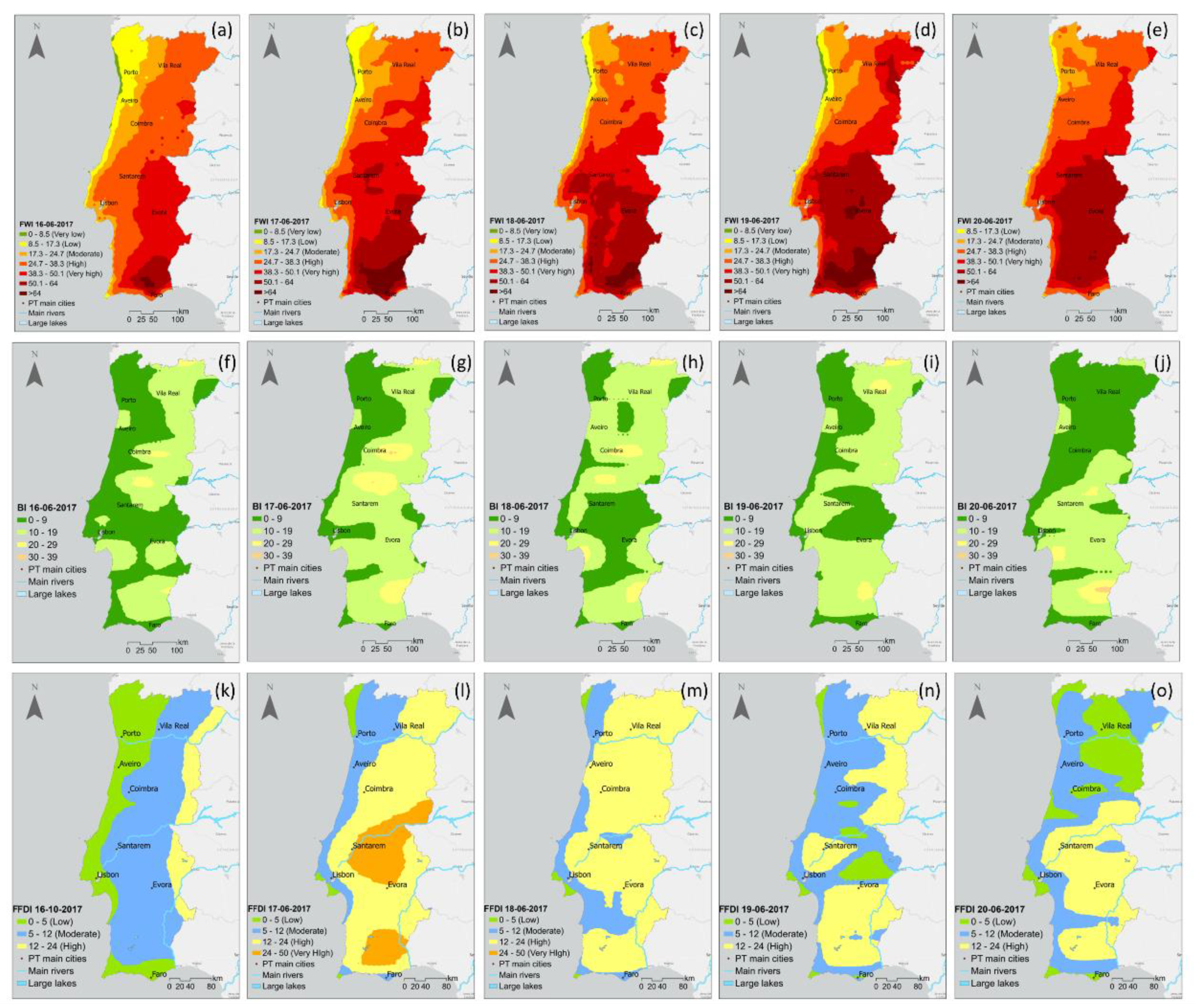

3.2.1. FWI, BI, and FFDI (Fire Intensity Indices)

3.2.2. SC, ISI (Fire Spread Related Components), and IC (Fire Ignition Related)

3.2.3. KBDI (Drought-Related Index)

3.2.4. BUI and ERC (Flame Front-Related Components)

3.2.5. CHI (Vertical Atmospheric Conditions)

3.3. Hotspot Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The maximum and mean monthly values for most of the indices were well above the average in 2017 in comparison with the control period, mainly in June and October. The mean monthly values for June/October of 2017 were statistically significant above the average (TST at a 5% S.L.) except for FFDI/CHI and FFDI, respectively.

- In June for CHI and BI, and in October for BI, statistically significant (MWW test at a 5% S.L.) high positive anomalies were observed in the vicinity of the major CEWEs.

- In September for BI, statistically significant anomalies (MWW test at a 5% S.L.) are already depicted, though with lower values in comparison with October. These results point out the long-term sensitivity of BI regarding CEWEs, even though its limitations are due to the actual scale.

- All indices presented higher danger values for October in comparison with June, except for CHI. In this case, the highest values were observed in June, thus portraying the contribution of atmospheric instability to the occurrence of this CEWE. Therefore, CHI helps understand the nature of the occurrences, besides the danger level, namely regarding the role of atmospheric instability in these events.

- The daily spatial distributions of FFDI and FWI, as well as KBDI and BUI, are quite similar. These indices can depict the dangerous conditions mainly for 17 June and 15 October. Since the information provided by them can be considered redundant, only one of the two pairs should be used to access the dangerous conditions.

- The spatial distributions of BI, SC, and ERC have had the best performance in capturing the locations for the occurrence of the two CEWEs with statistically significant hot hotspot superimposition areas.

- The ERC patterns revealed the amount of energy released in the locations of the two CEWEs.

- The higher IC values for October clearly show the areas affected by the 15 October wildfires with high values (30–59%) pointing out a high effort to suppress them.

- The spatial patterns of SC and its counterpart ISI, indicate high values associated with high velocities in the spread of these fires for the same target areas.

- The hotspot analysis allowed us to identify the type of clustering between the indices and the burned areas, thus defining statistically significant areas of high and low values.

- High-intensity clustering was depicted in the vicinity of the burned areas mainly for 15 October thus statistically linking the spatial distributions of most of the indices with them.

- For most of the indices, the locations of the statistically significant hot hotspots were depicted in regions in which the indices reached their maximum values. These results demonstrate the relevance of using several indices in helping to understand nature as well as identifying the locations of areas prone to the occurrence of CEWEs. These outcomes can serve as a case study to establish in the future a model to predict the dangerous conditions predisposed to the occurrence of wildfires in Portugal.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Pausas, J.G.; Vallejo, V.R. The role of fire in European Mediterranean ecosystems. In Remote Sensing of Large Wildfires; Chuvieco, E., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1999; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley, J.E.; Bond, W.J.; Bradstock, R.A.; Pausas, J.G.; Rundel, P.W. Fire in Mediterranean Ecosystems: Ecology, Evolution and Management; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ager, A.A.; Preisler, H.K.; Arca, B.; Spano, D.; Salis, M. Wildfire danger estimation in the Mediterranean area. Environmetrics 2014, 25, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedim, F.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Leone, V. Forest fires in Europe: Facts and challenges. In Wildfire Hazards, Dangers and Disasters; Paton, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, P.M.; Barros, A.M.G.; Pinto, A.; Santos, J.A. Characteristics and controls of extremely large wildfires in the western Mediterranean Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeo. 2016, 121, 2141–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Ascoli, D.; Safford, H.; Adams, M.A.; Moreno, J.M.; Pereira, J.M.; Catry, F.X.; Armesto, J.; Bond, W.; González, M.E.; et al. Wildfire management in Mediterranean type regions: Paradigm change needed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, J.; Werth, P. Haines Index climatology for the western United States. Fire Manag. Notes 1998, 58, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Littell, J.S.; McKenzie, D.; Peterson, D.L.; Westerling, A.L. Climate and wildfire area burned in western U.S. ecoprovinces, 1916–2003. Ecol. Appl. 2009, 19, 1003–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addington, R.N.; Hudson, S.J.; Hiers, J.K.; Hurteau, M.D.; Hutcherson, T.F.; Matusick, G.; Parker, J.M. Relationships among wildfire, prescribed fire, and drought in a fire-prone landscape in the south-eastern United States. Int. J. Wildland Fires 2015, 24, 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J.; Gill, A.M.; Moore, P.H.R. Seasonal Changes in Fire Behaviour in a Tropical Savanna in Northern Australia. Int. Int. J. Wildland Fires 2001, 8, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.; Contente, J. Köppen’s climate classification projections for the Iberian Peninsula. Clim. Res. 2020, 81, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köppen, W.; Geiger, R. Handbuch der Klimatologie; Gebrüder Bornträger: Berlin, Germany, 1930; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, A.N. Regional variability and driving forces behind forest fires in Portugal an overview of the last three decades (1980–2009). Appl. Geogr. 2012, 34, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M.; Loureiro, C.; Magalhães, M.; Ferreira, P.; Fernandes, M. Fuel age, weather and burn probability in Portugal. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2012, 21, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M. Variation in the Canadian Fire Weather Index Thresholds for Increasingly Larger Fires in Portugal. Forests 2019, 10, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meneses, B.M. Vegetation Recovery Patterns in Burned Areas Assessed with Landsat 8 OLI Imagery and Environmental Biophysical Data. Fire 2021, 4, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcasena, F.; Ager, A.; Le Page, Y.; Bessa, P.; Loureiro, C.; Oliveira, T. Assessing wildfire exposure to communities and protected areas in Portugal. Fire 2021, 4, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.M.; Rodrigues, A.; Lucas, D.; Viegas, D.X. The Impact on Structures of the Pedrógão Grande Fire Complex in June 2017 (Portugal). Fire 2020, 3, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, D.X.; Viegas, M.T. A relationship between rainfall and burned area for Portugal. Int. J. Wildland Fires 1994, 4, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, B.E. Atmospheric properties associated with large wildfires. Int. J. Wildland Fires 1996, 6, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Paula, S. Fuel shapes the fire—Climate relationship: Evidence from Mediterranean ecosystems. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuseppe, F.; Pappenberger, F.; Wetterhall, F.; Krzeminski, B.; Camia, A.; Libertá, G.; San Miguel, J. The Potential Predictability of Fire Danger Provided by Numerical Weather Prediction. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2016, 55, 2469–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolo, C.; Di Giuseppe, F.; Krzeminski, B.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J. A 1980–2018 global fire danger re-analysis dataset for the Canadian Fire Weather Indices. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 190032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ruano, A.; Mimbrero, M.R.; Jolly, W.M.; de la Riva Fernández, J. The role of short-term weather conditions in temporal dynamics of fire regime features in mainland Spain. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 241, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuseppe, F.; Vitolo, C.; Krzeminski, B.; Barnard, C.; Maciel, P.; San-Miguel, J. Fire Weather Index: The skill provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts ensemble prediction system. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 2365–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, D.A.; Main, W.A.; Simard, A.J. Operational validation of the NFDRS in the Northeast. In Proceedings of the Eight Conference on Fire and Forest Meteorology, Detroit, MI, USA, 29 April–2 May 1985; pp. 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagner, C.E. Development and Structure of the Canadian Forest Fire Weather Index System; Forestry Technical Report 35; Canadian Forest Service: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1987; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Stocks, B.J.; Lawson, B.D.; Alexander, M.E.; Van Wagner, C.E.; McAlpine, R.S.; Lynham, T.J.; Dube, D.E. The Canadian Forest Fire Danger Rating System: An overview. For. Chron. 1989, 65, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, B.E.; Goodrick, S. Performance of the Haines Index during August 2000 for Montana. In Proceedings of the 4th Symposium on Fire and Forest Meteorology, Reno, NV, USA, 13–15 November 2001; American Meteorological Society: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, B.E.; Winkler, J.A.; Dwight, F.W.; Ryan, P.S.; Xindi, B. Computing the low-elevation variant of the Haines Index for fire weather forecasts. Weather. Forecast. 2008, 23, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wagner, C.E.; Pickett, T.L. Equations and FORTRAN Program for the Canadian Forest Fire Weather Index System; Forestry Technical Report 33; Canadian Forestry Service, Petawawa National Forestry Institute: Chalk River, ON, Canada, 1985; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, D.X.; Reis, R.M.; Cruz, M.G. Calibração do Sistema Canadiano de Perigo de Incêndio para Aplicação em Portugal. Silva Lusit. 2004, 12, 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, A.; Flannigan, M.D.; Logan, K.; Miranda, A.I.; Borrego, C. Fire activity in Portugal and its relationship to weather and the Canadian Fire Weather Index System. Int. J. Wildland Fires 2008, 17, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaCamara, C.C.; Calado, T.J.; Ermida, S.L.; Trigo, I.F.; Amraoui, M.; Turkman, K.F. Calibration of the Fire Weather Index over Mediterranean Europe based on fire activity retrieved from MSG satellite imagery. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2014, 23, 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolo, C.; Di Giuseppe, F.; Barnard, C.; Coughlan, R.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Libertá, G.; Krzeminski, B. ERA5-based global meteorological wildfire danger maps. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPMA. Available online: htttps://www.ipma.pt/pt/media/noticias/newa.detail.jsp?f=/pt/media/noticias/arquivo/2017/rel-clima-outubro-2017.html (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- EFFIS. Available online: https://effis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Burgan, R.E. 1988 Revisions to the 1978 National Fire-Danger Rating System; Res. Pap. SE-273; U.S. Department of Agriculture; Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 1988; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- National Fire Danger Rating System (NFDRS). Van Nostrand’s Scientific Encyclopedia; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowdy, A.J.; Mills, G.A.; Finkele, K.; de Groot, W. Australian Fire Weather as Represented by the McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index and the Canadian Forest Fire Weather Index; CAWCR Technical Report No. 10; Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology: Canberra, Australia. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwi-3-uaoPn8AhXJUaQEHWD2BdIQFnoECAoQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cawcr.gov.au%2Ftechnical-reports%2FCTR_010.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1wJCf6EXqchLXtMc6fHcFx (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Noble, I.R.; Bary, G.A.V.; Gill, A.M. McArthur’s fire-danger meters expressed as equations. Aust. J. Ecol. 1980, 5, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keetch, J.J.; Byram, G.M. A Drought Index for Forest Fire Control; Research Paper SE-38; USDA Forest Service: Asheville, NC, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- ICNF. Available online: https://fogos.icnf.pt/sgif2010/ (accessed on 31 November 2021).

- IPMA. Available online: https://www.ipma.pt/pt/riscoincendio/fwi/ (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Pinto, P.; Silva, Á.P.; Viegas, D.X.; Almeida, M.; Raposo, J.; Ribeiro, L.M. Influence of Convectively Driven Flows in the Course of a Large Fire in Portugal: The Case of Pedrógão Grande. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, D.A. A lower atmospheric severity index for wildland fire. Natl. Weather. Dig. 1988, 13, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, B.D.; Armitage, O.B. Weather Guide for the Canadian Forest Fire Danger Rating System; Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Northern Forestry Centre: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2008; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Palheiro, P.; Fernandes, P.; Cruz, M. A fire behaviour-based fire danger classification for maritime pine stands: Comparison of two approaches. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 234 (Suppl. S1), S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.; Kim, J.; Won, M.S. Spatial patterns and temporal variability of the Haines Index related to the wildland fire growth potential over the Korean Peninsula. J. Korean Geogr. Soc. 2006, 41, 168–187. [Google Scholar]

- Bugalho, L. Temporal variability of the Haines index and its relationship with forest fire in Portugal. In Advances in Forest Fire Research; Chapter 1—Fire Danger Management; Publisher’s Name: Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, R.H.; McArthur, A.G. Bushfires in Australia; Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra, Australia, 1986; p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- Wain, A.; Kepert, D. A Comprehensive, Nationally Consistent Climatology of Fire Weather Parameters; Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- EEA. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/ims/forest-fires-in-europe (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- ICNF. Available online: http://www2.icnf.pt/portal/florestas/dfci/inc/estat-sgif (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- ICNF—Cartografia da área Ardida. Available online: http://www2.icnf.pt/portal/florestas/dfci/inc/mapas (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- ECWMF. Available online: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Copernicus Datasets. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biom. Bull. 1945, 1, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Non-parametric tests against trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.B.; Schuurman, N.; Hameed, S.M. A GIS-based spatiotemporal analysis of violent trauma hotspots in Vancouver, Canada: Identification, contextualization and intervention. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e003642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stopka, T.J.; Krawczyk, C.; Gradziel, P.; Geraghty, E.M. Use of spatial epidemiology and hot spot analysis to target women eligible for prenatal women, infants, and children services. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104 (Suppl. 1), S183–S189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, D.X.; Almeida, M.F.; Ribeiro, L.M.; Raposo, J.; Viegas, M.T.; Oliveira, O.; Alves, D.; Pinto, C.; Jorge, H.; Rodrigues, A.; et al. O Complexo de Incêndios de Pedrógão Grande e Concelhos Limítrofes, iniciado a 17 de Junho de 2017. Centro de Estudos sobre Incêndios Florestais, CEIF- Universidade de Coimbra. Relatório. 2017, p. 238. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339213823_O_complexo_de_incendios_de_Pedrogao_Grande_e_concelhos_limitrofes_iniciado_a_17_de_junho_de_2017/link/5e446d70a6fdccd9659f9efc/download (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Oom, D.; Artes, T.; Viegas, D.X.; Fernandes, P.; Faivre, N.; Freire, S.; Moore, P.; Rego, F.; Castellnou, M. Forest fires in Portugal in 2017. In Science for Disaster Risk Management 2020: Acting Today, Protecting Tomorrow; Casajus Valles, A., Marin Ferrer, M., Poljanšek, K., Clark, I., Eds.; EUR 30183 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 978-92-76-18182-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, J.; Fonseca, C.; Salgueiro, A.; Fernandes, P.; Lopez, E.; de Neufville, R.; Mateus, F.; Castellnou, M.; Silva, J.S.; Moura, J.; et al. (Eds.) Análise e Apuramento dos Factos Relativos aos Incêndios que Ocorreram em Pedrógão Grande, Castanheira de Pêra, Ansião, Alvaiázere, Figueiró dos Vinhos, Arganil, Góis, Penela, Pampilhosa da Serra, Oleiros e Sertã entre 17 e 24 de Junho de 2017; Independent Technical Commission, Assembly of the Republic: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro, J.; Fonseca, C.; Salgueiro, A.; Fernandes, P.; Lopez, E.; de Neufville, R.; Mateus, F.; Castellnou, M.; Silva, J.S.; Moura, J.; et al. (Eds.) Relatório: Avaliação dos Incêndios Ocorridos Entre 14 e 16 de Outubro de 2017 em Portugal Continental; Independent Technical Commission, Assembly of the Republic, Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. Available online: https://www.parlamento.pt/Documents/2018/Marco/RelatorioCTI190318N.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Viegas, D.X.; Almeida, M.A.; Ribeiro, L.M.; Raposo, J.; Viegas, M.T.; Oliveira, R.; Alves, D.; Pinto, C.; Rodrigues, A.; Ribeiro, C.; et al. Análise dos Incêndios Florestais Ocorridos a 15 de outubro de 2017; Centro de Estudos sobre Incêndios Florestais: 2019. Available online: https://www.portugal.gov.pt/pt/gc21/comunicacao/documento?i=analise-dos-incendios-florestais-ocorridos-a-15-de-outubro-de-2017 (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Tatli, H.; Türkes, M. Climatological evaluation of Haines forest fire weather index over the Mediterranean Basin. Meteorol. Appl. 2014, 21, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberà, M.J.; Niclòs, R.; Estrela, M.J.; Valiente, J.A. Climatology of the stability and humidity terms in the Haines Index to improve the estimate of forest fire risk in the Western Mediterranean Basin (Valencia region, Spain). Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 1212–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, W.M.; Freeborn, P.H.; Page, W.G.; Butler, B.W. Severe Fire Danger Index: A Forecastable Metric to Inform Firefighter and Community Wildfire Risk Management. Fire 2019, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.; Contente, J.; Santos, J.A. Climate Change Projections of Dry and Wet Events in Iberia Based on the WASP-Index. Climate 2021, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.; Contente, J.; Santos, J.A. Climate Change Projections of Aridity Conditions in the Iberian Peninsula. Water 2021, 13, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M.; Davies, G.M.; Ascoli, D.; Fernández, C.; Moreira, F.; Rigolot, E.; Stoof, C.R.; Vega, J.A.; Molina, D. Prescribed burning in southern Europe: Developing fire management in a dynamic landscape. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, e4–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandes, P.M.; Rossa, C.G.; Madrigal, J.; Rigolot, E.; Ascoli, D.; Hernando, C.; Guiomar, N.; Guijarro, M. Prescribed burning in the European Mediterranean Basin. In Global Application of Prescribed Fire, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; Chapter 13; pp. 230–248. ISBN 9781032137179. [Google Scholar]

| FWI | Color Code | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0–8.5 | Green | Very low |

| 8.5–17.3 | Yellow | Low |

| 17.3–24.7 | Light orange | Moderate |

| 24.7–38.3 | Orange | High |

| 38.3–50.1 | Red | Very high |

| 50.1–64 | Dark red | Extreme/Maximum |

| >64 | Brown |

| CHI | Probable Fire Behavior and Fire Prediction Reliability |

|---|---|

| <4 | Easily controlled fire. Models easily predict the path of the fire. |

| 4–8 | Fires can be difficult to control, and their behavior can be erratic. The modeling of the behavior of the fire is likely to be close to reality. |

| 8–10 | Fires will be difficult to control, and the behavior of the fire will be erratic. Modeling the behavior of the fire likely underestimates reality. |

| >10 | Fires are uncontrollable and extremely difficult to extinguish. Modeling of fire behavior dramatically underestimates reality. |

| BI | Fire Behavior and Suppression |

|---|---|

| <40 | Fires can be attacked at the head or flanks by firefighters using hand tools. The hand line should hold the fire. |

| 40–80 | Fires are too intense for a direct attack on the head by firefighters using hand tools. The hand line cannot be relied on to hold fire. Equipment such as dozers, pumpers, and retardant aircraft can be more effective. |

| 80–110 | Fires may present serious control problems torching out, crowning, and spotting. Control efforts at the fire head will probably be ineffective. |

| >110 | Crowning, spotting, and major fire runs are probable. Control efforts at the head of the fire are ineffective. |

| KBDI | Fire Behavior and Suppression |

|---|---|

| 0–50 | Soil moisture and large-class fuel moistures are high and do not contribute much to fire intensity. Typical of the spring dormant season following winter precipitation. |

| 50–100 | Typical of late spring, early growing season. Lower litter and duff layers are drying and beginning to contribute to fire intensity. |

| 100–150 | Typical of late summer, or early fall. Lower litter and duff layers actively contribute to fire intensity and will burn. |

| 150–200 | Often associated with more severe drought with increased wildfire occurrence. Intense, deep-burning fires with significant downwind spotting can be expected. Live fuels can also be expected to burn actively at these levels. |

| Date | District | Urban Areas (ha) | Bush Areas (ha) | Total Burnt Area (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 June 2017 | Leiria | 30,359.00 | 0.15 | 30,359.18 |

| Coimbra | 9483.30 | 8037.64 | 17,521.45 | |

| 47,880.63 | ||||

| 15 October 2017 | Coimbra | 89,638.08 | 11,014.75 | 11,1582.20 |

| Guarda Castelo Branco | 24,836.50 21,290.01 | 17,664.23 12,991.67 | 47,649.22 35,790.34 | |

| Leiria | 19,283.93 | 984.40 | 20,741.06 | |

| Viseu | 11,969.01 | 4623.15 | 18,013.13 | |

| Aveiro | 8787.08 | 1875.89 | 11,421.33 | |

| 245,197.30 |

| 2001–2021 | 2017 | 2007 | 2001–2021 | 2017 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum FWI | Mean FWI | |||||

| May | 31.1 | 33.6 | 25.6 | 14.3 | 14.5 | 10.7 |

| Jun | 42.5 | 48.9 | 27.3 | 24.3 | 31.8 | 14.7 |

| Jul | 49.7 | 53.1 | 50.3 | 33.0 | 36.1 | 30.2 |

| Aug | 51.0 | 54.7 | 51.0 | 34.4 | 38.1 | 31.9 |

| Sep | 46.6 | 51.2 | 43.2 | 25.0 | 34.2 | 19.6 |

| Oct | 32.0 | 64.7 | 24.0 | 12.0 | 28.9 | 11.0 |

| Maximum CHI | Mean CHI | |||||

| May | 8.9 | 9.4 | 10.2 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.7 |

| Jun | 9.4 | 10.8 | 9.1 | 4.8 | 6.1 | 3.5 |

| Jul | 10.0 | 10.8 | 10.9 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 5.4 |

| Aug | 9.9 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 4.8 |

| Sep | 9.2 | 9.6 | 9.7 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 4.9 |

| Oct | 9.0 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 4.0 | 6.7 | 4.4 |

| Maximum KBDI | Mean KBDI | |||||

| May | 13.6 | 14.7 | 8.5 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 4.0 |

| Jun | 28.2 | 38.3 | 12.7 | 18.8 | 26.1 | 7.2 |

| Jul | 49.0 | 59.3 | 30.9 | 37.7 | 48.3 | 19.3 |

| Aug | 68.2 | 79.2 | 48.3 | 58.7 | 70.3 | 40.8 |

| Sep | 75.7 | 88.1 | 54.0 | 65.9 | 82.7 | 45.7 |

| Oct | 62.2 | 95.8 | 27.4 | 45.5 | 85.5 | 18.6 |

| Maximum BI | Mean BI | |||||

| May | 11.1 | 10.8 | 10.0 | 5.5 | 4.9 | 4.9 |

| Jun | 12.9 | 13.7 | 9.3 | 8.0 | 9.6 | 5.6 |

| Jul | 14.8 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 10.3 | 11.2 | 10.5 |

| Aug | 14.1 | 15.9 | 14.7 | 10.0 | 11.1 | 10.1 |

| Sep | 12.7 | 14.4 | 12.7 | 7.0 | 9.8 | 6.1 |

| Oct | 10.2 | 18.2 | 10.9 | 4.3 | 8.5 | 5.4 |

| Maximum FFDI | Mean FFDI | |||||

| May | 8.7 | 8.8 | 7.1 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 3.2 |

| Jun | 12.9 | 16.9 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 8.5 | 3.9 |

| Jul | 17.4 | 20.8 | 18.6 | 9.3 | 11.3 | 8.3 |

| Aug | 18.9 | 20.3 | 16.5 | 10.5 | 12.5 | 8.7 |

| Sep | 15.9 | 21.9 | 12.4 | 7.9 | 10.5 | 5.9 |

| Oct | 9.8 | 21.0 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 10.6 | 3.7 |

| p-Values | FWI | CHI | KBDI | BI | FFDI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2021 | 2017 | 2007 | 2017 | 2007 | 2017 | 2007 | 2017 | 2007 | 2017 | 2007 |

| May | 0.715 | 0.016 | 0.126 | 0.792 | 0.101 | 0.000 | 0.952 | 0.866 | 0.005 | 0.006 |

| Jun | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.368 | 0.122 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.441 | 0.000 |

| Jul | 0.018 | 0.061 | 0.281 | 0.793 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.034 | 0.002 | 0.020 |

| Aug | 0.016 | 0.311 | 0.037 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.032 | 0.008 | 0.000 |

| Sep | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.127 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.883 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Oct | 0.000 | 0.233 | 0.115 | 0.076 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.099 | 0.206 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andrade, C.; Bugalho, L. Multi-Indices Diagnosis of the Conditions That Led to the Two 2017 Major Wildfires in Portugal. Fire 2023, 6, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire6020056

Andrade C, Bugalho L. Multi-Indices Diagnosis of the Conditions That Led to the Two 2017 Major Wildfires in Portugal. Fire. 2023; 6(2):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire6020056

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndrade, Cristina, and Lourdes Bugalho. 2023. "Multi-Indices Diagnosis of the Conditions That Led to the Two 2017 Major Wildfires in Portugal" Fire 6, no. 2: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire6020056

APA StyleAndrade, C., & Bugalho, L. (2023). Multi-Indices Diagnosis of the Conditions That Led to the Two 2017 Major Wildfires in Portugal. Fire, 6(2), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire6020056