Abstract

The Memphite Necropolis of Saqqara is situated approximately 20 km south of modern Cairo on a plateau at the edge of the western desert and was in use as a funerary site for a period of nearly three and a half millennia. Today, the site is popular with visitors and archaeologists alike, but its ruinous condition and a proscribed visitor experience does little to offer visitors an understanding of the necropolis and how it was inhabited during the ancient past. This article examines the current documentary and excavation research on the Memphite Necropolis of Saqqara during the Late Period/early Ptolemaic era and considers its inhabitants, their routes of movement, and where they may have lived and worked. This article contends that the landscape of the necropolis was dynamic and full of activity. A mixture of priests, craftsmen, merchants, and others involved in the daily activities of the temples and cults, along with pilgrims, worshippers, and casual visitors, would have been moving in and around the necropolis daily.

1. Introduction

From the early years of the 19th century onwards, the Memphite necropolis of Saqqara (which lies approximately 20 km south of Cairo) became a focus of archaeological investigation, which led to the site now being one of the most visited archaeological areas in Egypt [1] (p. 61). Access to the necropolis is controlled by the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, and strict routes of movement are in place that guide the visitor to a limited number of tombs [1] (p. 61). Prior to the beginning of modern archaeological activity at the site, the necropolis was visited by early travellers [2] who were most often escorted by local fellahin, who acted as guides and souvenir vendors, and it is probable that at this time the site would have been generally deserted. The funerary necropolis is vast in size, and the tombs and temples appear unconnected and often empty. But what of the necropolis during the Late Period/early Ptolemaic era? Was access controlled as it is now, and who was allowed into the necropolis, were their movements constrained, and when was access permissible?

2. The Ancient Necropolis of Memphis

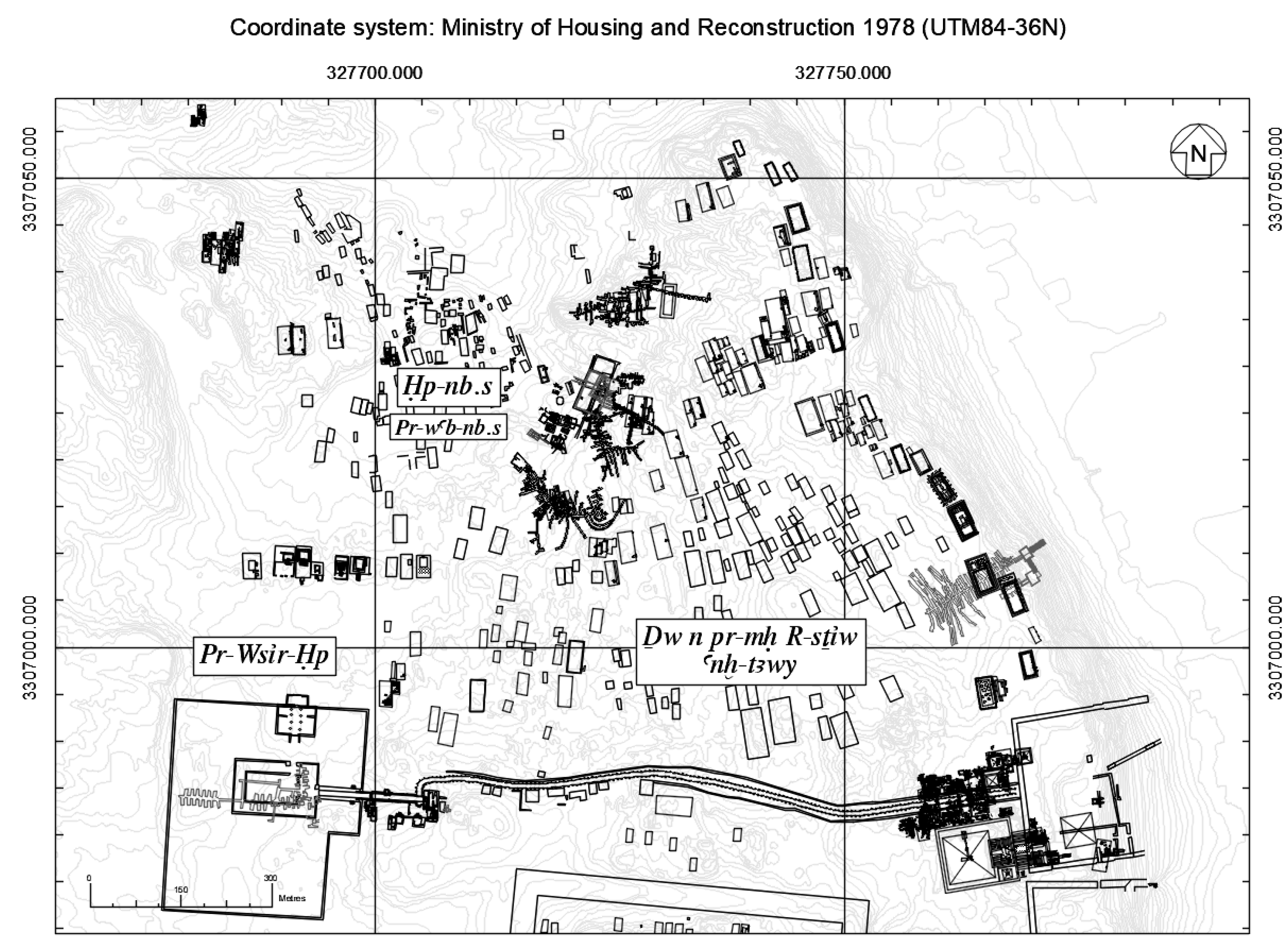

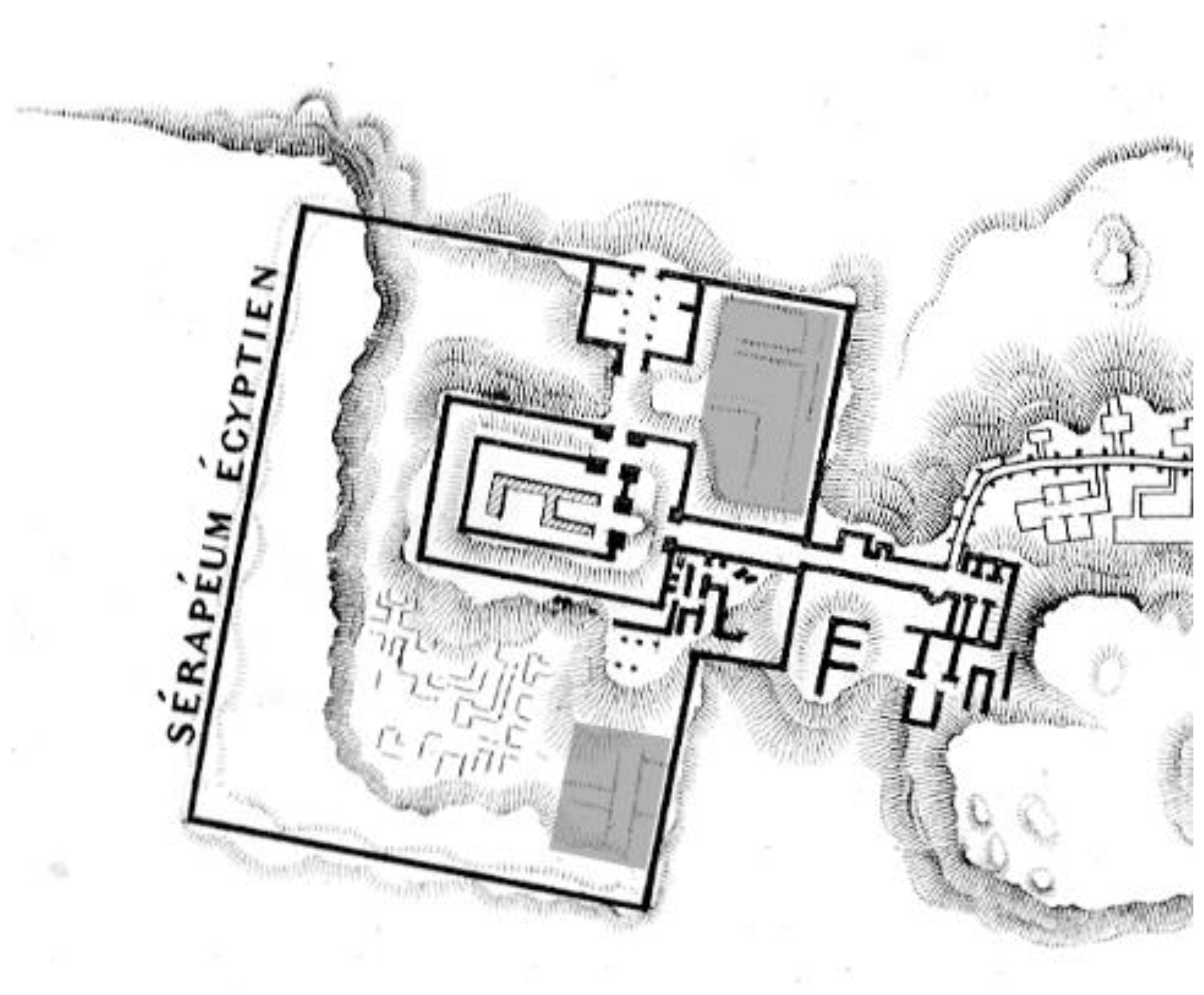

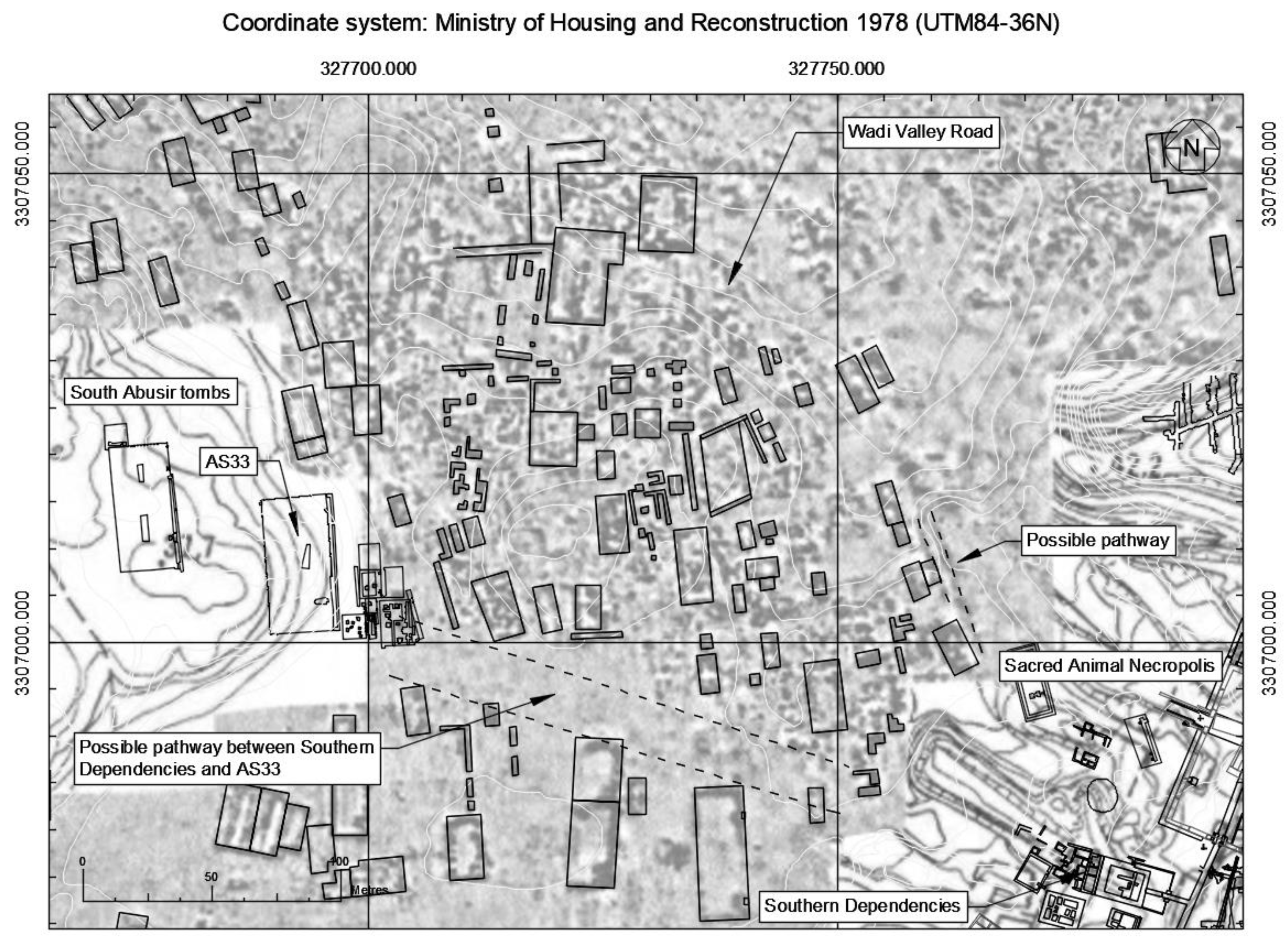

It should be mentioned here that the name by which the Memphite necropolis of Saqqara was known during the Late Period was anx-tAwy (aAnkhtawy’), and within the northern extent of anx-tAwy were the locations of Pr-Wsir-1p (the Serapeum) and 1p-nb.s (Hepnēbes) [3] (p. 3); [4] (pp. 146–147); [5] (p. 24). Each of these localities comprised smaller regions, often known through surviving texts (e.g., [4]), providing an indication of their general location (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Locations of the ancient place names of the Memphite necropolis at North Saqqara (source: author (Figures 1, 3–5, and 7–10 comprise map data compiled by the author in GIS from archival sources).

The title Serapeum, as we have come to understand it today, is synonymous with the hypogea of the Apis bulls, but the Late Period/Ptolemaic era use was more complicated. Indeed, Pr-Wsir-1p was a name that encapsulated the area of the Apis burials, enclosure, temple, and dromos, probably the ceremonial Serapeum Way and the landscape to the north where another sacred way led to and from 1p-nb.s [3] (p. 3). The associated locality of 1p-nb.s appears to define the area north of the Serapeum Precinct, and it is here that the burial site of the mother of Apis and the other cult temples and interments of the Sacred Animal Necropolis are located [4] (p. 148). The application of 1p-nb.s during the Late Period may have been interchangeable with that of Pr-Wsir-1p or simply used to differentiate the location of the northern animal galleries from that of the Apis burials. However, the title Pr-wab-nb.s is also applied to the region of 1p-nb.s [4] (p. 148); [5] (p. 27), although it appears to specifically relate to the temples and galleries of the Ibis and Hawks and may only signify a local designation [4] (pp. 148–9) (For a comprehensive map of place names and their locations within the necropolis, see [4] (p. 152) (Figure 3).

For clarity, the term Serapeum Precinct will be used to define the wider area of the Apis burials, including the dromos, enclosure, north gate, and temples. The Serapeum Way will refer to the ceremonial processional way leading west from the lower terraces of the valley, up through the Anubieion towards the Serapeum. The area of Hepnēbes to the north of the Serapeum Precinct will be referred to by its modern title of the Sacred Animal Necropolis (hereafter abbreviated to SAN), and this includes the main temple enclosure and subterranean catacombs of the mothers of Apis, Hawks, and Baboons, the North and South Ibis gardens and catacombs, and the Southern Dependencies. The ‘Lake of Pharaoh’ refers to the now dry lake or pool of Abusir [4] (p. 134), the vestiges of which are visible on satellite photography of the area.

3. Life at the Necropolis

A limited number of contemporary accounts of everyday life at the necropolis have survived (see [4,5,6,7], (Chapter 7 in [5])). The accounts date from the early Ptolemaic period, and it is probable that conditions were similar during the Late Period also. They generally describe the circumstances and tribulations of a few Memphite katochê during the Ptolemaic period (the term Katochê describes a detention within the boundaries of a shrine or temple and relates to individuals indentured therein, either through choice or obligation). These enkatachoi were sequestered within limits, often the temple boundaries, and in some circumstances they were restricted to their pastophorion or cells. Some individuals participated in temple community activities and industries, such as the procurement of food and water, for which they were financially remunerated. They were often financially supported by relatives residing away from the temples [5] (p. 207), and in [8] (p. 131) it is suggested that some may have been given license to beg. Certain states of katochê permitted the enkatachoi to leave their cells and access the wider temple areas and beyond.

The surviving accounts portray a cramped community environment within the precincts of the Serapeum [8] (p. 136), active with commerce, administration, and interaction with people from outside the temple districts [5] (p. 204). Despite the framework of constraints within this enclosed environment, merchants, workmen, and visitors, composing a transient population, were probably able to move in and out of the Serapeum Precinct.

The great temple enclosure of the Anubieion is also known to have been an important centre for administration and commerce, where a sizeable population would have lived and worked [5] (p. 23). It is here that the workers of the cults of the necropolis probably lived and conducted their business. Visitors to the necropolis may have passed through this settlement, sampling merchandise and purchasing votives as offerings to the gods.

During the later Late Period into early Ptolemaic times, the popularity of the animal cults was at its highest [9] (p. 49), and during the festival days of the cults it is probable that many pilgrims and visitors would have entered the necropolis for feasts, processions, worship, and offerings. Several caches of votive depositions are known from the area of the SAN [10], deposited as offerings for the gods. These votive items were purchased and donated by the pious who wished to receive oracles or favours from their gods [11], and their use provides examples of the trade and manufacture of such objects, possibly from merchants and workshops in the near vicinity.

4. Networks of Movement

In the past, as now, several pathways provided means to enter and negotiate the necropolis [5] (p. 18), and it is probable that these were used by both officials of the cults and visitors alike. Despite much of the necropolis terrain being predominantly shifting sand interspersed with discrete areas of bedrock, the paths of movement appear to have endured. Reich [12] (p. 14) considers two main routes that would convey people from Memphis to the necropolis. The first route he discusses appears to correspond to the location of the modern motor road into the necropolis, which probably follows an ancient pathway [5] (p. 18) originally leading to the south Bubastieion gateway. Dodson’s [13] (p. 3) argument against this as an ancient route into the necropolis does not preclude this being the case. For whilst he suggests that the modern road lies atop a build-up of debris accumulated over the centuries, and therefore is not the ancient route, this situation is not without parallel elsewhere in archaeology and the possibility of the modern route following an ancient one cannot be discounted.

The principal ancient route into the necropolis was along the wide wadi valley that extends southwards from the direction of Pr-Wsir (modern Abusir) [13,14]; [15] (p. 92, ); [16]. The ancient name of this wadi is unknown, and Dodson suggests that the use of this route as a formal processional way may date back to as early as the 2nd Dynasty, initially providing a route to the subterranean tombs of Hetepsekhemwy and Ninetjer [13] (p. 8). From the Late Period, at least, the great sarcophagi of the Apis bulls were transported south along this route to the Serapeum Enclosure [17] (p. 338).

Numerous other less important networks of movement would have also crossed the necropolis, formed through the daily activities of its inhabitants.

5. Casual Visitation

Visitors’ graffiti, dating mainly from the 18th and 19th Dynasties, are known from the complex of Djoser and the tomb of Horemheb [18] (p. 65) at North Saqqara. The graffiti, often etched into the stone of the monuments, appear to have been made predominantly by scribes for their own purposes, or perhaps on occasion for visitors accompanying them. The tradition of graffiti in the Djoser complex continued through into the Late Period, where examples are known from up to and including the 26th Dynasty. This accords well with the renewed interest and general archaism of this period with respect to the earlier dynasties [19] (pp. 83–88) and the Saite opening and restoration of the tunnels beneath the Step Pyramid [19] (p. 15). Although the dates of the graffiti in Horemheb’s tomb are unclear, it does suggest that visitors had access to certain tombs. Navrátilová [18] (p. 133) notes that it is difficult to determine whether the scribes who wrote on Horemheb’s tomb were on a leisure walk through the necropolis or there on official business, but the use of certain terminology may suggest that they were out walking and amusing themselves. A certain formula for New Kingdom visitors’ graffiti has been assigned in the nomenclature “the stroll”, appearing to demonstrate a visit of a casual character that may have been connected to sightseeing rather than a pious pilgrimage.

Based on the interpretation of these formulae, the probability that the wider necropolis was accessible to visitors is credible, with the graffiti evidence implying it was a destination visited by people for casual amusement. This does not preclude an element of controlled access to the funerary site, but it does appear to give the impression that in the ancient past, as now, the site generated interest not just for the pious pilgrim but also for sightseeing visitors who were able to negotiate the necropolis. The fact that graffiti were being etched into the monuments may also suggest that visitors moved around the site without official supervision or oversight. That said, it is entirely possible when visiting the necropolis nowadays either to avoid the site guards and view prohibited areas unhindered (although this is not entirely advisable) or to pay bakhsheesh to the guards to be given limited access, and this situation may have also occurred in the ancient past. The graffiti provide us with an insight into destinations at the necropolis that held a fascination for people unconnected with its daily activities and allow us to surmise that parts of the funerary site were accessible for such casual visitations. In addition to visiting popular monuments, people will also have come to the necropolis to donate offerings to their gods or to partake in religious festival days.

Spalinger [20] (pp. 241–260) concludes that religious festivals were commonly closed to the general populace, taking place within the seclusion of the temples, away from general view. He contends that Pharaonic religion provided a less-than-inclusive approach to religious practices. However, Assman [21] (p. 108) makes a clear distinction between everyday cultic activity and the religious festival, characterizing them as secret and public, respectively. He remarks that the everyday cultic activity was undertaken within the confines of the temple, strictly excluding the public, to whom it remained a mystery, but that it was through procession that the religious experience was made public and the cult activity taken into the outside world. Through this latter activity, the general populace participated in religious life and would have gathered from afar for such events.

6. Performance of Procession

The performance of procession would have engendered movement through the necropolis during religious festivals and attracted audiences [21] (p. 108) who may have lined the sacred ways. A small number of processional ways are known to have existed in the necropolis, with the Serapeum Way being perhaps the best known. The route began at the temple of Apis at Memphis, some 5 km away [22] (p. 109), and, approaching from the lower terraces of the Nile valley, traversed up the escarpment through the precinct of the Anubieion, continuing west to the Serapeum Precinct and the hypogea of the Apis bulls. The paved route was flanked on either side by mud-brick walls [12] (p. 37) to hold back the sand and lined with sphinx statues sitting atop plinths [23] (Mariette’s [24] (PL.II) plan depicts at least 162 sphinxes flanking the Serapeum Way beyond the Anubieion). At its apogee, this sacred route would have been a remarkable sight.

After death, the mummified Apis bull was transported from the embalming house at Memphis along this route, through various stages, to its final resting place within the necropolis. This journey was accompanied by considerable performance [5] (p. 186) and crowds of observers participating in this national event [5] (p. 188). If the audience was permitted to view the procession along the latter extent of its route, near the Serapeum Precinct, then the topography of the site would lend itself to favourable viewing conditions. The terrain on either side of the route along this section is dense with early mastabas (Figure 2) which, although probably badly denuded and (partially) buried by this time, would have provided possible viewing platforms, either as the remnants of the mud-brick structures themselves or from the sand piled atop them. This situation persists to this day, where conspicuous mounds of sand with eroded mud brick protruding through attest to the hidden structures beneath.

Figure 2.

Decaying mastaba tombs situated alongside the Serapeum Way, seen here protruding from the overburden of sand (to the left and right of the image) (photo: author).

Another two known processional ways at Saqqara are those of Anubis and Shabaka. These ceremonial routes are known only from writing, and their locations remain open to interpretation. The Demotic papyri (P. Dem. Memphis) [7] describe in rather vague terminology (this is Martin’s summarisation of the demotic text) the Processional Way of Anubis as running “along the eastern side of a sepulchre (whose western side is the gebel […]) and a tomb […], the other three neighbours of which were tombs, and that these tombs were in the southern part of the necropolis” [7] (p. 48). Whilst the description is ambiguous and not very helpful in locating the ceremonial route, it does evidence a processional way that is very probably associated with the precinct of the Anubieion.

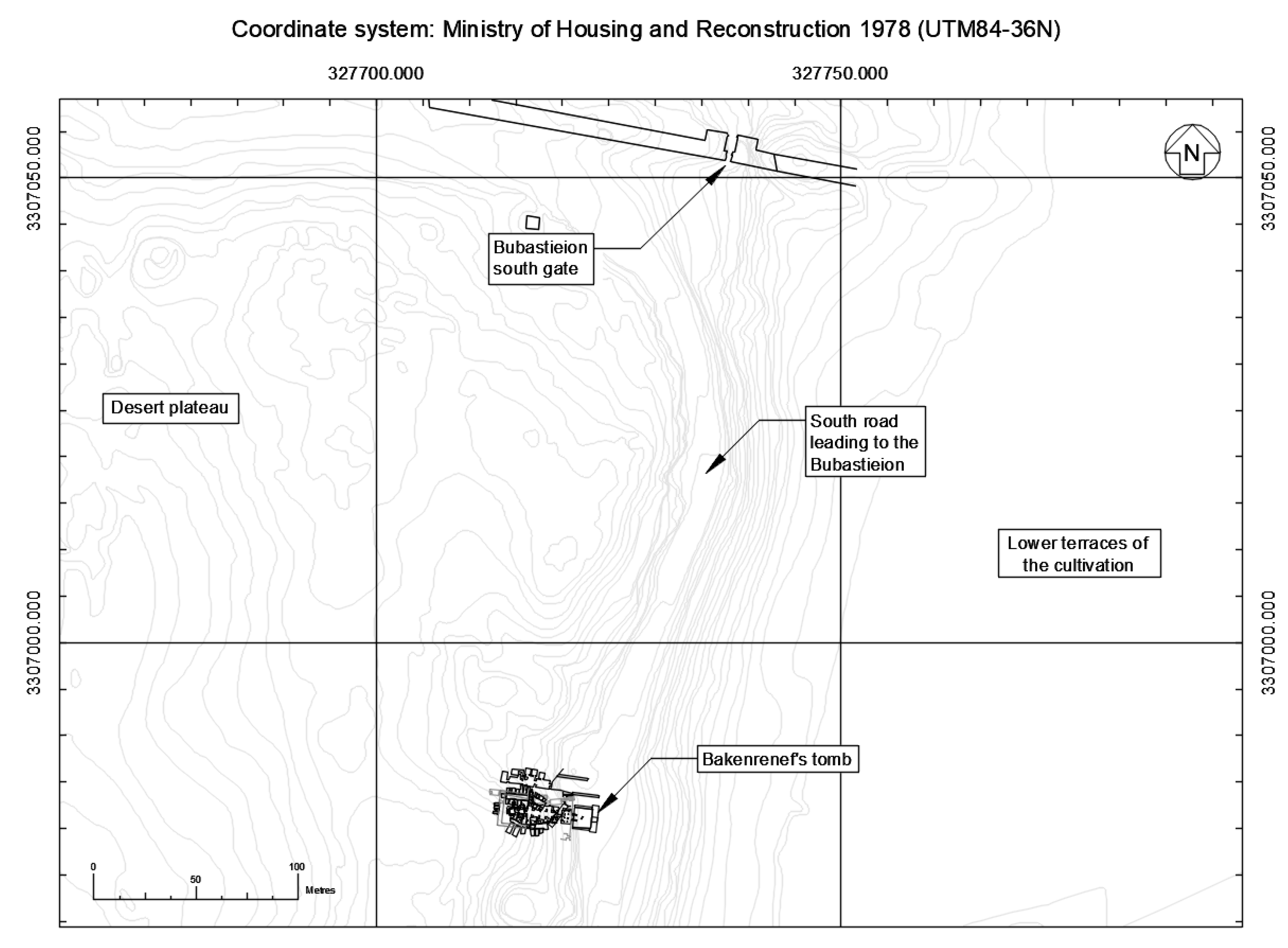

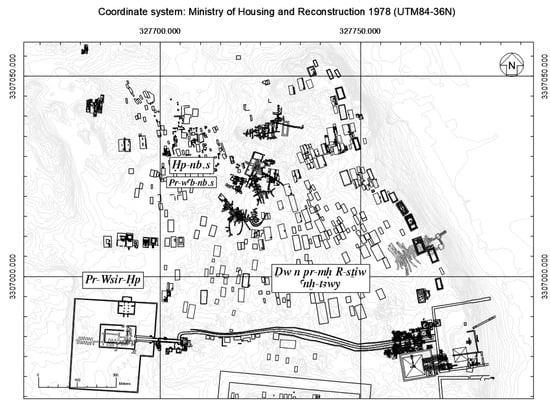

The tomb “whose western side is the gebel” may be that of Bakenrenef (Figure 3), a notable Late Period tomb in the desert escarpment towards the southern extent of North Saqqara. Smith [7] (p. 48, footnote 142) has suggested that the Processional Way of Anubis originated near the Ptah temple in Memphis and would have approached the Anubieion from the south, negotiating the escarpment along the route of the modern motor road, also suggested as an ancient pathway by Thompson [5] (p. 18), probably passing through the south gate of the Bubastieion precinct. It would appear, then, that the Processional Way of Anubis did not lead directly onto the plateau of the necropolis but instead traced the periphery of the escarpment towards the great Late Period temple precincts.

Figure 3.

The tomb of Bakenrenef set into the desert escarpment. The modern motor road can be seen to the right of the tomb (source: author).

The second processional way mentioned in the papyri is that of Pharaoh Shabaka. This processional route is known only from a single line in the papyri’s text, and little information is given. As with the Processional Way of Anubis, an abstruse description of the route’s location is offered, which Martin summarises as being “located in the southern part of the Memphite necropolis, to the east of a tomb whose northern and western neighbours are sepulchres” [7] (p. 50). Despite the obscure description, it is certain that the route threads its way between tombs and sepulchres, implying that it crosses the plateau within the boundaries of the necropolis. No detail is provided regarding the use of this processional route, but its existence serves as evidence that prescribed routes of movement were in use.

7. Settlements of the Necropolis

The living population of the funerary site was probably made up of both occasional visitors and (semi-)permanent residents, and the necropolis would have included defined areas of settlement. Whether these settlements were permanently or infrequently occupied is uncertain. The limitations of living on a desert plateau at a distance from the nearest source of water emphasise the difficulties of permanent occupation. However, Thompson [5] (206) notes that water carriers would have journeyed daily from the plateau to the valley below, making permanent occupation a possibility.

The primary locations where settlement activity could be expected to be found are the enclosures of the Bubastieion and Anubieion, the Serapeum Precinct, and the greater area of the Sacred Animal Necropolis. The wadi valley leading from the Lake of Pharaoh southward into the necropolis may also have hosted an established settlement. There may well have been other minor settlements on the plateau.

7.1. Anubieion

Adjacent to the Bubastieion, situated beyond its northern boundary, lies the enclosure of the Anubieion. This substantial monument has benefitted from a greater extent of archaeological investigation than its neighbour to the south, and, as a result, more is known of the settlement within its boundary walls. Jeffreys and Smith [25] (p. 25) contend that the Anubieion settlement was a dependency of the temple complex, due to its position between the main sanctuaries and the western boundary wall. Thompson [5] (p. 23) remarks that papyri evidence suggests the Anubieion complex was an important administrative centre, where official documents were registered in the grapheion, and that the stratêgos, the area governor, had a local representative based here. Additionally, a unit of police was stationed in the complex, which also housed a prison. The area comprised houses, storehouses, and mills, and was densely populated by people of various trades.

Archaeological excavation in the settlement area within the Anubieion has provided evidence of densely arranged shelters, storerooms, and domestic structures with kitchens replete with food preparation areas, firepits, and subterranean storage cells [25] (pp. 26–27). There is evidence that the settlement area may have been surrounded by a compound wall [25] (p. 27), within which the building squares appear to have been laid out in a regular pattern that respected the alignment of the Anubieion complex. Small streets offered access into the buildings, and open areas in the vicinity are presumed to be for cattle tethering. Walled courtyards have been interpreted as being for external domestic activities such as food preparation and washing [25] (p. 27). Amongst the domestic buildings are probable guest houses or hostels, suggested by long communal rooms whose rapid accumulation of floor layers concealed quantities of coins, perhaps received in payment, or hidden away and subsequently lost. Documentation supports the view that parts of the Anubieion complex were given over to hostelry, giving rise to this interpretation [25] (p. 29).

Over time, the settlement solidified from a transitory foundation to a stable community of a reasonable size, with densely arranged buildings set around a communal area adjoined by kitchens, storage and, farther out, residential properties and hostelries [25] (p. 29).

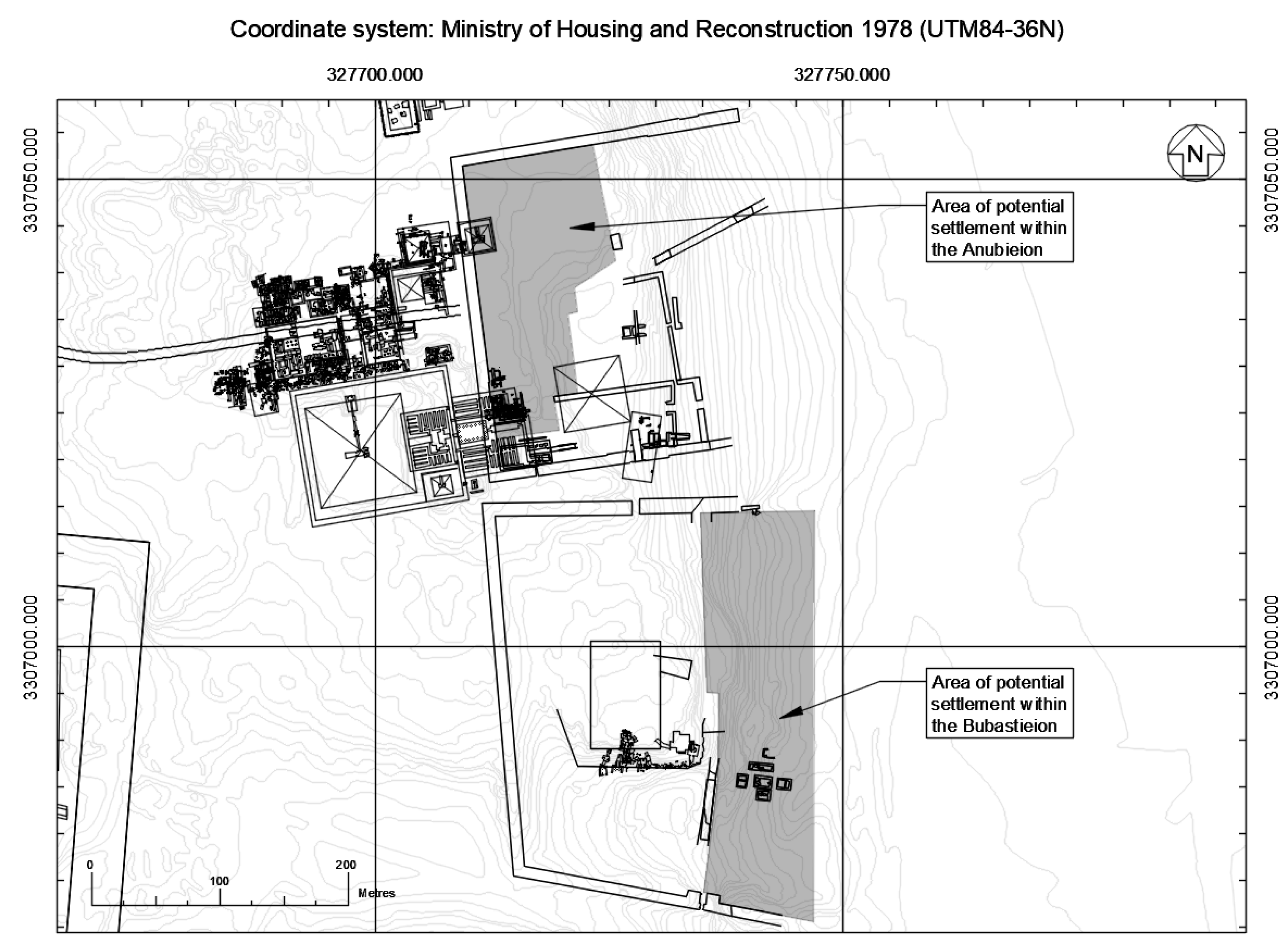

The archaeological evidence suggests a flourishing community occupying a crowded settlement of buildings situated within the greater Anubieion temple enclosure. A similar situation is likely to have been extant in the Bubastieion, where the structures discussed above appear, in plan at least, to be very like those of the Anubieion settlement.

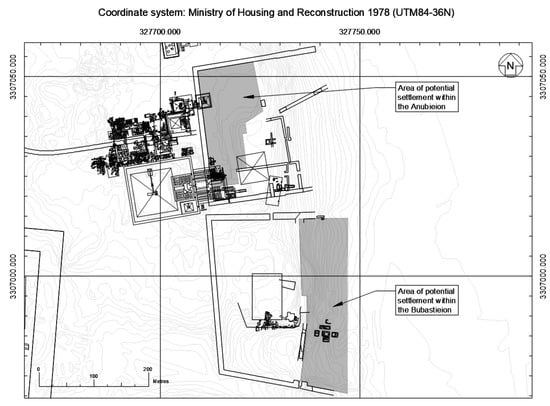

7.2. Bubastieion

Limited information is available for the Bubastieion. Beyond the work of Jeffreys and Smith [25] and Zivie [26,27,28], little else is known about the archaeological remains. Thompson [5] (p. 19) remarks that the Bubastieion (Pr-bAstt) housed at least two and probably three stone temples, in addition to subsidiary shrines, dwellings for the priesthood, and additional buildings. The Temple of the Peak was probably located within the great enclosure. This important monument to the Falcon, Hawk, and Ibis cults was administered by priestly scribes of the temple and men of the cults, who oversaw the windows of appearance. The Asklepieion, a temple of great importance dedicated to the scribe and architect Imhotep, was located somewhere nearby, and buildings of the temple personnel and other Egyptians of many professions bordered the structure [5] (p. 22).

Vestiges of mud-brick structures within the Bubastieion area can be seen along the lower terraces of the plateau. These denuded and heavily sanded features were excavated some time prior to 1925, although by whom remains unclear, and no report has been published [25] (p. 78). The buildings appear to lie within the boundary of the great enclosure [25] (Figure 1) and respect the general orientation of the temple complex. Jeffreys and Smith [25] (p. 78) contend that these buildings were situated on terraces connected by stairs or ramps, and that the entire area of the lower enclosure may have been occupied by similar brick buildings on the same scale (Figure 4). They surmise that this may represent the domestic and administrative quarter of the temple. This would reflect the situation as recorded within the Anubieion temple complex situated to the north.

Figure 4.

The temple enclosures of the Bubastieion and Anubieion. Potential settlement locations are shaded grey (source: author).

It is possible that the buildings associated with the Bubastieion may have extended beyond the boundaries of the temple enclosure, with additional structures being located outside the temple walls, similar perhaps to the pyramid towns of Kahun or Giza (see [29] (pp. 64–68 and pp. 179–180), which developed beyond and away from the structures with which they were associated. Unfortunately, future excavation of this area which could support or disprove this hypothesis is unlikely due to modern construction.

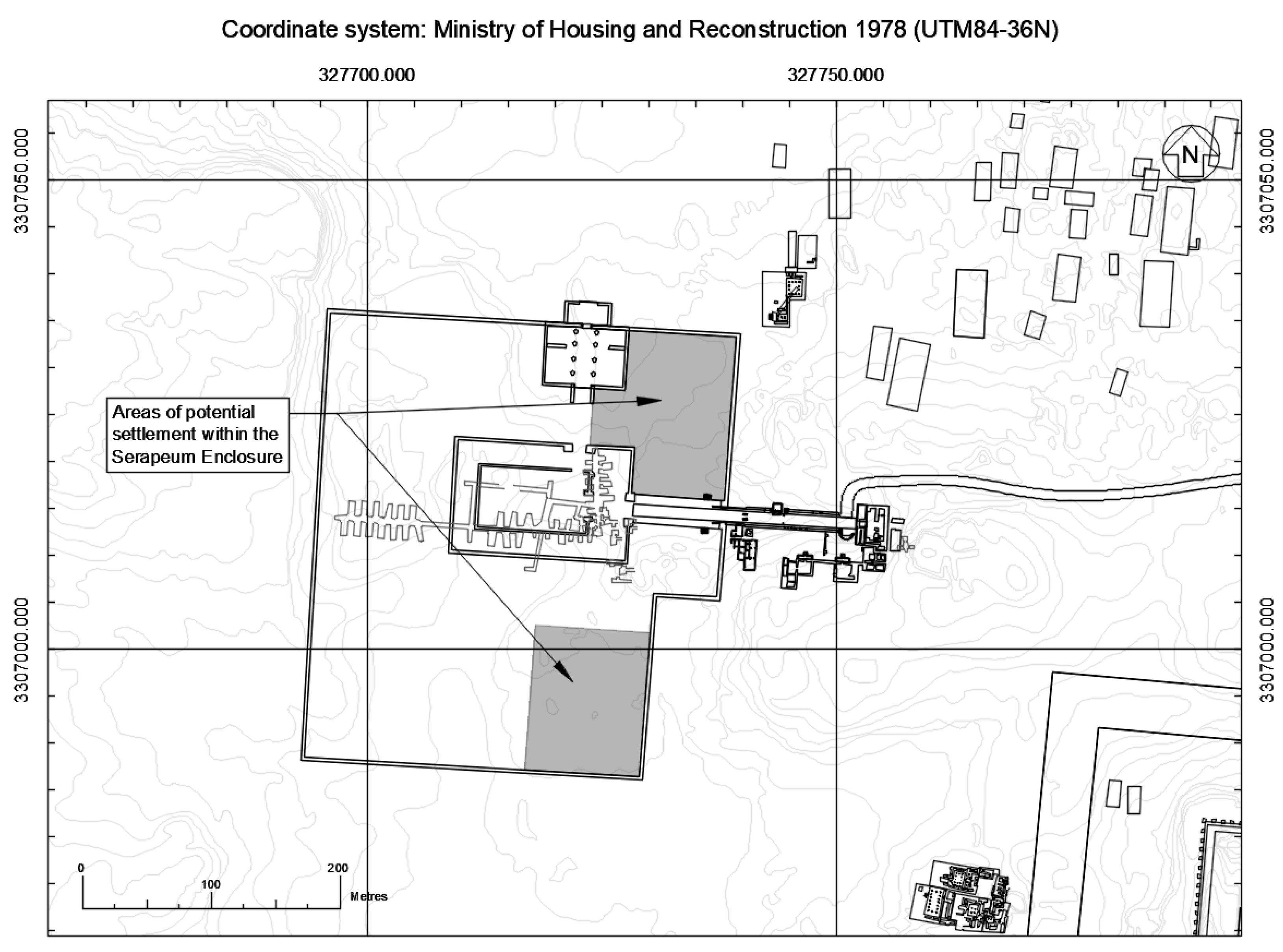

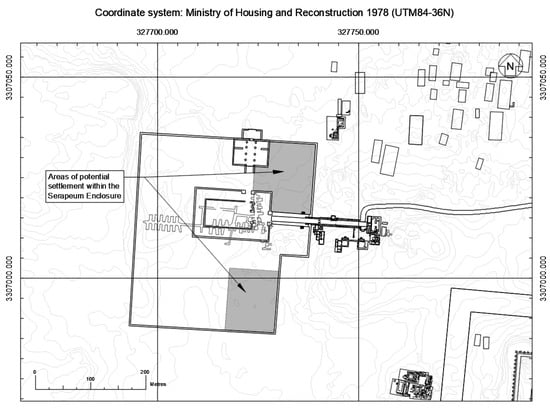

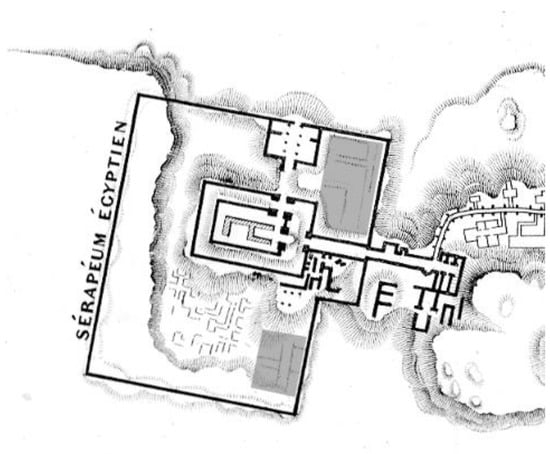

7.3. Serapeum

There is much documentary evidence (see [5,30,31]) providing details of life in the greater precinct of the Serapeum, as discussed above. However, archaeological evidence for structures within the enclosure is limited and, where observed, poorly recorded. The excavations of the Serapeum and its dromos, carried out under Mariette in the mid-1800s, are not particularly well published, with little information available to aid understanding of all but the major features of the precinct. It is understood from Mariette’s plan of the Serapeum dromos [32] (Abb.5) that a structured layout of temples, shrines, and buildings, for priests and presumably katochê, were constructed outside of the main enclosure. Unfortunately, Mariette’s [24] (Pl.II) plan of the enclosure’s internal features is lacking this type of detail.

That a busy settlement was situated here is almost certain, but how it was laid out or precisely where it was situated is more difficult to clarify (Figure 5). Excavation has provided some clues for the locations of buildings that have been interpreted as either dwellings or guesthouses associated with the Serapeum. Smith describes a katalumata [33] (p. 421) excavated by Macramallah [34] (p. 77), situated in the location of the Serapeum. The buildings, dating to the Late/Greco-Roman Period, are comparably constructed to those settlement structures already described within the Bubastieion and Anubieion temple complexes and comprise a collection of small rooms adjoining and abutting one another in a regular grid-like pattern. This small cluster of buildings was interpreted by Macramallah either as possible shelters or guesthouses for pilgrims and visitors or as dwellings for the servants of the gods of the Serapeum temples.

Figure 5.

The Serapeum temple complex. Potential settlement locations are shaded grey (source: author).

Mariette’s 1854 plan appears to suggest that rectilinear features are present in the north-eastern corner of the Serapeum Enclosure [24] (Pl.II). These features (Figure 6) appear to respect the general alignment of the temple complex in the same manner as those of the Bubastieion and Anubieion. Similar features are present in the south-eastern corner to the south of the fragmentary plan of a temple structure situated adjacent to the central temple compound. These features appear somewhat ephemeral on the plan, presenting little more than an indication of something beneath the sand. It is possible that Mariette noted their presence and alignments but did not investigate further.

Figure 6.

Possible settlement archaeology (shaded grey) depicted as hatched lines on the Mariette plan [24] (Pl.II).

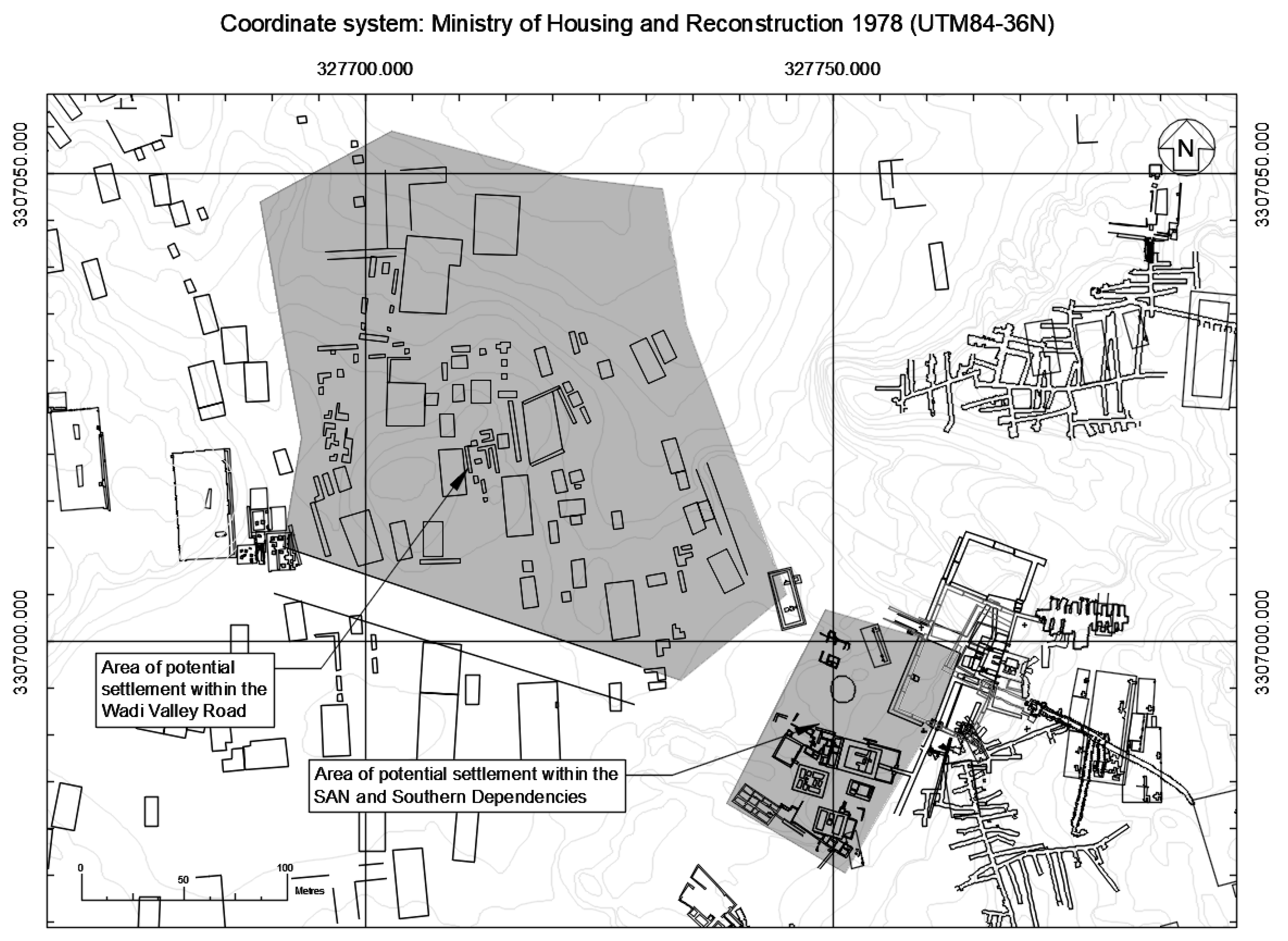

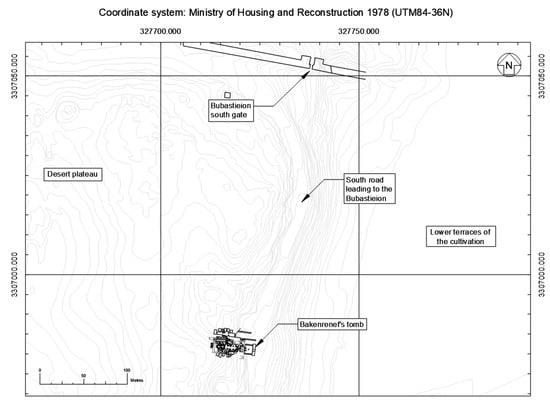

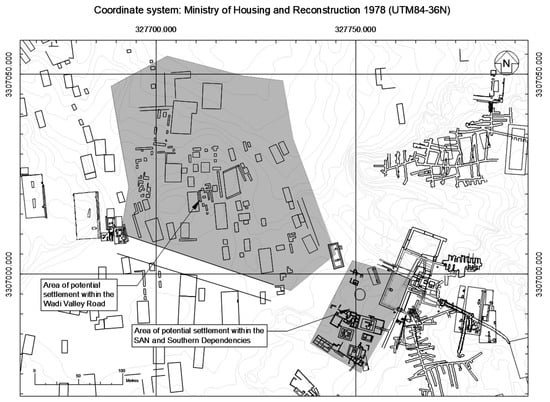

7.4. Sacred Animal Necropolis

The SAN is located towards the northern extent of the necropolis and covers an extensive area. The SAN encompasses the North and South Ibis catacombs and the catacombs of the Hawks, Baboons, and the mother of Apis, along with the Main Temple Enclosure (hereafter abbreviated to MTE) and its Southern Dependencies. Beneath the later phases of the MTE, and beyond its southern and western walls (Figure 7), archaeological excavation has revealed small rectilinear structures of varying dimensions, interpreted as “workmen’s houses” [35] (pp. 67–730); [36] (p. 18). Within the MTE, the crude buildings were constructed upon the sloping sand of the escarpment, therefore pre-dating much of the structure. They may have been contemporary with the earliest phases, but Smith has associated with them with the secondary phases of the temples’ expansion [35] (p. 72). Similarly, a workers village observed within the Southern Dependencies was discovered, situated beneath mud-brick platforms and enclosures attesting to its earlier date. To the west of the MTE west wall, the building foundations observed there were constructed on the sand of the escarpment slope. These mud- and tafl-brick structures were similar in construction to the other presumed workmen’s houses, and their topographical location suggests an associated function. Jeffreys postulates that not all the buildings are of the same date, some being earlier than others [35] (p. 175), suggesting an evolving, albeit transitory settlement.

Figure 7.

The SAN and Wadi Valley Road potential settlement locations, shaded grey (source: author).

The settlements of the Bubastieion, Anubieion, and Serapeum are presumed to have accommodated workers of the cults, their families, visitors, and guests, and were contemporaneous with the functioning of the temple complexes. The character of the workers village of the SAN, however, is quite different. It appears to be a temporary settlement for labourers employed in the construction of the MTE and subsidiary buildings, and as such, it was abandoned once these tasks were completed. It is unclear where those occupied with the cults would have resided.

7.5. The Wadi Valley Road

The central area of the Abusir wadi valley is currently devoid of visible structural remains; however, that is not to say that this was always so. Several authors contend that this route was the principal approach to the necropolis during ancient times [14]; [13] (p. 6); [15] (p. 92); [16], leading south towards the monumental tombs of the 2nd and 3rd Dynasty rulers. It would seem appropriate, then, that a settlement may have evolved at the opening of this routeway, close to the Lake of Pharaoh.

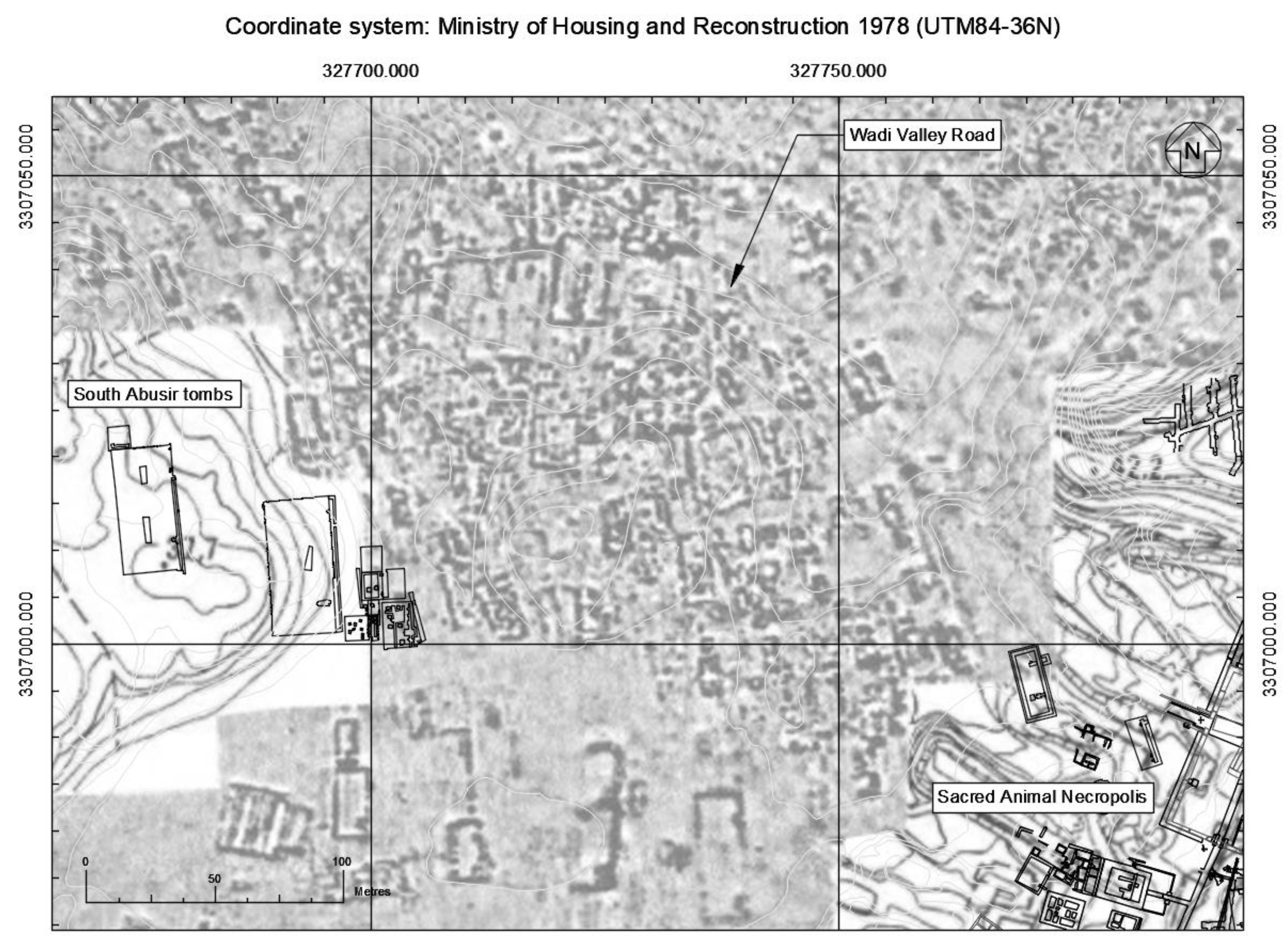

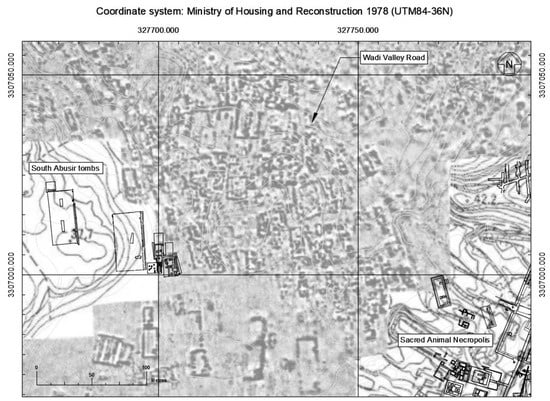

Geophysical prospection, conducted by the Saqqara Geophysical Survey Project (hereafter abbreviated to SGSP) across the greater necropolis [37] has provided potential evidence of a dense settlement along the wadi road (Figure 8). Individual structures, perhaps surrounded by smaller more ephemeral features, are clearly visible, although without excavation there can be no definitive understanding of what is represented by the data, in terms of whether the features were contemporary with one another or with their surroundings, when their use began, or when they were abandoned.

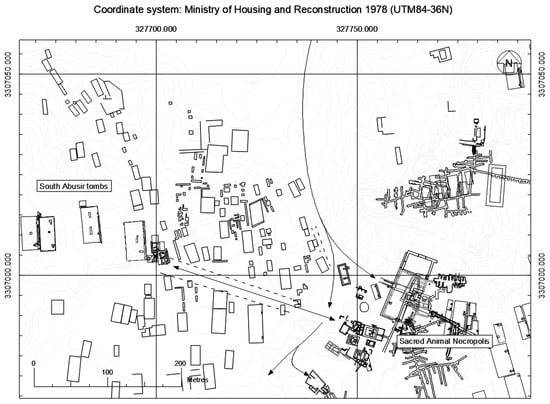

Figure 8.

The SGSP geophysical survey data [37] of the area of the Wadi Valley Road between the Abusir South tombs and the SAN (source: author), overlaid onto the Ministry of Housing and Reconstruction map of 1978.

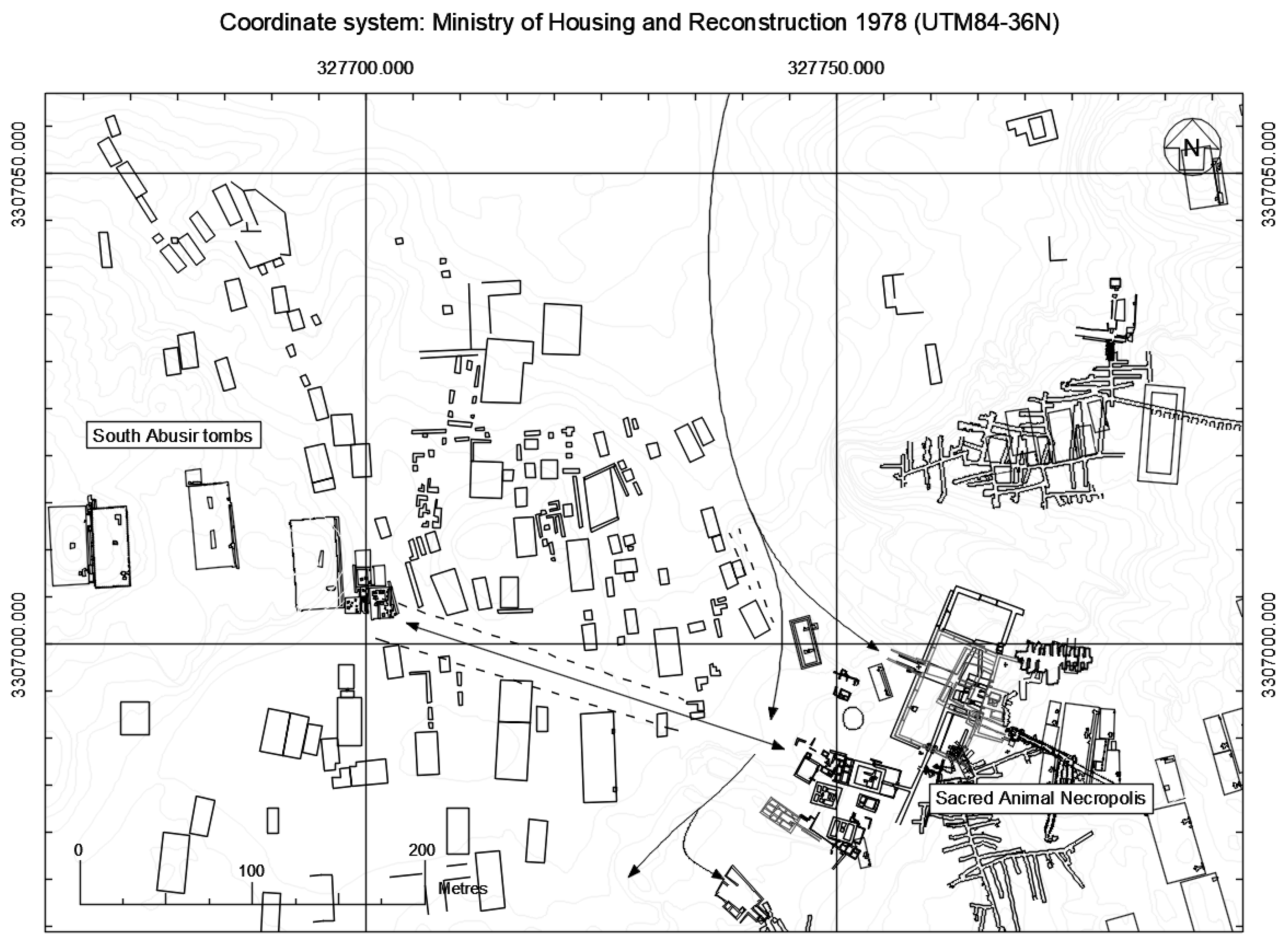

A general alignment is discernible within the layout of the features, which appear to follow a roughly north–south orientation, with some deviations. The structures appear to follow the orientation of unexcavated mastaba tombs situated slightly farther south. The directionality is at odds with the orientation of the wadi valley, which is aligned north-north-east to south-south-west, setting the structures obliquely across the routeway. A scarcity of structures along the eastern edge of the wadi valley may suggest that the route along the wadi road from the Lake of Pharaoh may have been directed up the eastern side of the valley, towards the MTE and Southern Dependencies (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Author’s interpretation of the SGSP geophysical survey data [37]. The postulated route of the Wadi Valley Road leading into the necropolis and towards the SAN is indicated by the black arrows (source: author).

The structural features set against the western escarpment of the wadi valley appear to respect the alignment of the edge of the valley and follow its orientation, and it is probable that the features spreading to the north-west are small mastaba tombs, like those excavated by the Czech mission (see [14,38,39,40,41,42]). There is an intriguing linear transect across the wadi valley, situated between the presumed settlement activity to the north and the mastaba tomb structures to the south (Figure 10). This feature is aligned roughly south-south-east to north-north-west and appears to communicate between the area of the Southern Dependencies and the palace-façaded 3rd Dynasty mastaba AS33, situated on the opposite side of the wadi valley. Mastaba AS33 was reused during the Late Period for bovid burials, which were deposited into pits carved in the denuded upper surface of the tomb [40] (p. 181).

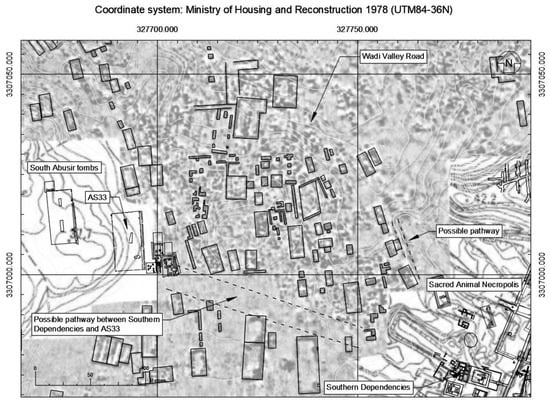

Figure 10.

Two possible pathways in the Wadi Valley Road visible in the interpretation of the SGSP survey data [37] (source: author), overlaid onto the Ministry of Housing and Reconstruction map of 1978.

The subsurface anomalies displayed on the geophysical plot may represent a small, organic settlement in the location where Smith suggests the houses and workshops of embalmers and other tradespersons may have been located [43] (pp. 69–70). The postulated settlement may have housed both permanent and transient workers and craftsmen, serving both the temples of the sacred animals and the living ibis on the Lake of Pharaoh. Future excavation in these areas would provide evidence to support or disprove this hypothesis.

8. Discussion

The landscape of the necropolis during the Late Period/early Ptolemaic era was dynamic and full of activity. Reich [12] (p. 38) discusses pilgrims visiting the Serapeum and remarks that the great dromos was used like a marketplace, with the government auctioning state property there. Both Reich [12] (p. 39) and Ray [30] (p. 701) provide lists of a variety of professions all working and living together, which characterises the Serapeum as more like a market town than a funerary institution for the Apis bull. Ray [30] (p. 701) comments that the settlements of the Serapeum may have resembled the expansive workers villages at Kahun and Deir el-Medina (see [29] (pp. 64–68) for Kahun and [29] (pp. 74–86) for Deir el-Medina). There would have been the addition of guesthouses for pilgrims, apartments for dream interpretation, shops, and inns that catered to the needs of visitors [30] (p. 701). The population of the Serapeum Precinct would have increased during the festivals of the cults, when an influx of the general populace would have journeyed to the necropolis.

During the public religious festivals, the necropolis landscape near and around the cult centres may have been busy with people who had come to observe the processions and partake in the religious experience. Public participation could have encouraged the rising popularity of the animal cults, which Nicholson contends were a “religious expression of nationalistic feeling” [9] (p. 49). The embalming and burial of animals reminded the people of less troubled times than those in which they lived [9] (p. 49), and the purchasing of a mummified animal or votive offering for the gods may have engendered a closeness with those gods whom they worshipped and revered, creating a shared identity.

The complex settlements associated with the large temples and the sacred animal cults suggest that there was an abundance of people moving around the necropolis. These settlements appear to have begun as somewhat transitory collections of poorly built structures which developed over time into permanent villages comprising residential and commercial properties. Their character is generally one of diverse structures adjoining and abutting one another in an arranged pattern of small holdings, accessed by passageways and courtyards. At the large temple enclosures of the Bubastieion, Anubieion, and Serapeum, the settlements appear to have developed around or near the central temples within the enclosure precinct. The SAN does not follow this pattern, as the postulated village appears to be external to the main temple enclosure, situated along the approach to the necropolis in the wadi valley. The residents of this settlement may have served both the MTE where the catacombs of the mother of Apis, Baboons, and Falcons are situated, the North and South Ibis catacombs, and the ibis breeding grounds at the Lake of Pharaoh. The hypotheses regarding the conjectural settlements are tentative, being based on a series of inferences made on untested data. Targeted archaeological excavation would be required to support or disprove them.

9. Conclusions

The research considered here suggests that during the Late Period/early Ptolemaic era, a mixture of priests, craftsmen, merchants, and others involved in the daily activities of the temples and cults, along with pilgrims, worshippers, and casual visitors, would have been moving around the necropolis. It should be noted, however, that the Memphite necropolis is vast, and whilst specific areas may have been bustling, much of the rest of the site was probably primarily without activity. This presents a situation that is comparable to the modern ambience of the historic site, which is often active and dynamic, where popular areas area busy with people, sounds, and smells.

However, the motivations for visiting the necropolis were manifestly different. In the Late Period/early Ptolemaic era (and other periods of the ancient past when the site was a focus for funerary deposition), the predominant motivation for visiting the necropolis appears to have been religious. Funerals, priestly duties, worship, and pilgrimage all exist within this category. Non-religious employment within the necropolis would have also drawn many people to the site, which is comparable to the situation in modern times. Casual sightseeing, which is the predominant motivation for visits today, appears to have been a limited phenomenon during the Late Period/early Ptolemaic era. Each of these diverse reasons for being in the necropolis would have influenced the personal experience of those visiting the site. However, the general atmosphere of bustling activity—albeit in specific areas—in both the ancient past and modern times is probably comparable.

Funding

This research formed part of the author’s PhD thesis, and as such was assisted by a tuition-fee bursary, generously awarded by Cardiff University’s School of History, Archaeology and Religion.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to extend gratitude and thanks to Paul Nicholson, Steve Mills, Harry Smith, Sue Davies, Dorothy Thompson, Salima Ikram, Aidan Dodson, and Lidija Mcknight.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bresciani, E. Memphis and the Saqqara Necropolis. In The North Saqqara Archaeological Site: Handbook for the Environmental Risk Analysis; Ago, F., Bresciani, E., Giammarusti, A., Eds.; Università di Pisa: Pisa, Italy, 2003; pp. 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Baber, T. Ancient Corpses as Curiosities: Mummymania in the Age of Early Travel. J. Anc. Egypt. Interconnect. 2016, 8, 60–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S. The Sacred Animal Necropolis at North Saqqara. The Mother of Apis and Baboon Catacombs. The Archaeological Report; Egypt Exploration Society: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, J.D. The Archive of Hor; Egypt Exploration Society: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D.J. Memphis Under the Ptolemies, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Legras, B. Les reclus grecs du Sarapieion de Memphis: Une enquête sur l’hellénisme égyptien. In Studia Hellenistica; Peeters Publishers: Leuven, Belgium, 2011; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C.J. Demotic Papyri from the Memphite Necropolis in the Collections of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, the British Museum and the Hermitage Museum; Brepols: Turnhout, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, J.D. Reflections of Osiris. Lives from Ancient Egypt; Profile Books: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, P.T. The Sacred Animal Necropolis at North Saqqara. The Cults and Their Catacombs. In Divine Creatures. Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt; Ikram, S., Ed.; The American University in Cairo Press: Cairo, Egypt, 2005; pp. 44–71. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, P.T.; Smith, H.S. An unexpected cache of bronzes. Egypt. Archaeol. 1996, 9, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling, J.; Manti, P.; Nicholson, P.T. Discovery and conservation of a hoard of votive bronzes from the Sacred Animal Necropolis at North Saqqara. PalArch 2004, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, N.J. New Documents from the Serapeum of Memphis. Mizraim 1933, 1, 9–129. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson, A. Go west: On the ancient means of approach to the Saqqara Necropolis. In Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt. Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David; Price, C., Foreshaw, R., Chamberlain, A., Nicholson, P.T., Eds.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2016; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bárta, M.; Vachala, B. The Tomb of Hetepi at Abusir South. Egypt. Archaeol. 2001, 19, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Malek, J. The Temples at Memphis. Problems Highlighted by the EES Survey. In The Temple in Ancient Egypt: New Discoveries and Recent Research; Quirke, S., Ed.; British Museum Press: London, UK, 1997; pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Reader, C. On Pyramid Causeways. J. Egypt. Archaeol. 2004, 90, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.S. À l’ombre d’Auguste Mariette [avec un dépliant]. Bull. De L’institute Français D’archaéolgie Orient 1981, 81.1, 331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Navrátilová, H. The Visitors’ Graffiti of Dynasties XVIII and XIX in Abusir and Northern Saqqara; Czech Institute of Egyptology: Prague, Czech Republic, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stammers, M. The Elite Late Period Egyptian Tombs of Memphis; BAR International Series 1903; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Spalinger, A. The Limitations of Formal Ancient Egyptian Religion. J. Near East. Stud. 1998, 57, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assman, J. Das ägyptische Prozessionfest. In Das Fest und das Heilige: Religiöse Kontrapunkte zur Alltagswelt; Assman, J., Sundermeier, T., Eds.; Gütersloher Verlagshaus G. Mohn: Gütersloh, Germany, 1991; pp. 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, D. Temples of the Last Pharaohs; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mariette, A. Le Sérapeum de Memphis; Gide: Paris, France, 1882. [Google Scholar]

- Mariette, A. Choix de Monuments et de Dessins Découverts ou Exécutés Pendant le Déblaiement du Sérapeum de Memphis; Gide et J. Baudry: Paris, France, 1856. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys, D.G. and Smith, H.S. The Anubieion at Saqqâra I. The Settlement and the Temple Precinct; Egypt Exploration Society: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zivie, A. Les Tombes de la Falaise du Bubasteion à Saqqarah: Tombes D’importants Personnages, Nécropole de Chats, la Falaise du Bubasteion est Décidemment Riche en Enseignements et en Surprises de Toutes Sortes; Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique: Paris, France, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Zivie, A. La Tombe de Maïa. Mère Nourricière du roi Toutânkhamon et Grande du Harem; Caracara édition: Toulouse, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zivie, A. La tombe de Thoutmes, directeur des peintres dans la place de Maât; Caracara Edition: Toulouse, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Snape, S. The Complete Cities of Ancient Egypt; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, J.D. The House of Osorapis. In Man, Settlement and Urbanism; Ucko, P.J., Tringham, R., Dimbleby, G.W., Eds.; Duckworth: Gloucester, UK, 1972; pp. 699–704. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, J.D. The World of North Saqqara. World Archaeol. 1978, 10, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, D. Die Heiligen Tiere und der König. Teil 1, Beiträge zu Organisation, Kult und Theologie der Spätzeitlichen Tierfriedhöfe; Otto Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.S. Saqqara: Late Period. In Lexikon der Ägyptologie V; Helck, W., Otto, E., Eds.; Otto Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1975; pp. 412–428. [Google Scholar]

- Macramallah, R. Un Cimetière Archaèque de la Classe Moyenne du Peuple à Saqqarah; Imprimerie Nationale: Cairo, Egypt, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.S.; Davies, S.; Frazer, K. The Sacred Animal Necropolis. The Main Temple Complex. The Archaeological Report; Egypt Exploration Society: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, G.T. The Sacred Animal Necropolis at North Saqqara. The Southern Dependencies of the Main Temple Complex; Egypt Exploration Society: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson, I.; Dittmer, J. The Geophysical Survey of North Saqqara, 2001–7. J. Egypt. Archaeol. 2007, 93, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárta, M.; Černy, V.; Strouhal, E.; Abusir, V. The Cemeteries at Abusir South I; Set Out: Prague, Czech Republic, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bárta, M.; Bezděk, A.; Černy, V.; Ikram, S.; Kočár, P.; Křivánek, R.; Kujanová, M.; Pokorný, P.; Reader, C.; Sůvová, Z.; et al. Abusir XIII. Abusir South 2. Tomb Complex of the Vizier Qar, His Sons Qar Junior and Senedjemib, and Iykai; Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of the Arts, Charles University in Prague: Prague, Czech Republic, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bárta, M.; Coppens, F.; Vymazalová, H.; Kytnarová, K.A.; Bezděk, A.; Březinová, H.; Cίlek, V.; Dvořák, M.; Háva, J.; Lang, M.; et al. Abusir XIX: Tomb of Hetepi (AS 20), Tombs AS 33–35 and AS 50–53; Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of the Arts, Charles University in Prague: Prague, Czech Republic, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bárta, M.; Abe, Y.; Kytnarová, K.A.; Havelková, P.; Hegrlík, L.; Jirásková, L.; Malá, P.; Nakai, I.; Novotný, V.; Ogidani, E.; et al. Abusir XXIII. The tomb of the Sun Priest Neferinpu (AS 37); Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of the Arts, Charles University in Prague: Prague, Czech Republic, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vymazalová, H.; Kytnarová, K.A.; Beneš, J.; Bezděk, A.; Březinová, H.; Pokorná, A.; Sůvová, Z.; Šuláková, H.; Varadzin, L.; Malá, P.Z. Abusir XXII. The Tomb of Kaiemtjenenet (AS38) and the Surrounding Structures (AS 57–60); Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of the Arts, Charles University in Prague: Prague, Czech Republic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.S. A Visit to Ancient Egypt: Life at Memphis & Saqqara, c. 500–30 B.C; Aris & Phillips: Warminster, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).