1. Introduction

The social lockdown brought about by COVID-19 was suffered by many countries in the first half of 2020. In this context, Web 2.0 became one of the few spaces that made it possible for people to meet. As a result of this development, there was an international acceleration of the digitization process of museums that started in this period and was reflected in the increase in virtual content generated by museum institutions [

1,

2,

3]. While in some cases museums reacted to the situation according to their technical and human possibilities, leaving no time for reflection on the co-communicative actions they were carrying out virtually [

4], many other such institutions were identified and analyzed as examples of good edu-communicative practices in the context of Web 2.0 [

3,

5]—practices inspired by the theoretical proposals that had already begun to consolidate themselves before the pandemic [

6,

7].

The study of edu-communication for heritage—which began almost a decade ago in the disciplinary framework of heritage education [

8] and draws on Ibero-American epistemological references [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]—has shown that museum proposals in social networks are capable of activating awareness and human bonds around heritage [

14]. On the basis of these driving forces, it is possible to generate and consolidate heritage cybercommunities comparable in nature to the heritage communities recognized by the Faro Convention [

15], but with the added potential to develop civic actions both online and offline [

5,

7]. But 2.0 communities not only promote social participation for the conservation and transmission of heritage. As spaces where users create, share and generate new knowledge based on the contents proposed by museum institutions, mutual, spontaneous and dialogical learning is built inside them, thus giving rise to the so-called co-creative paradigm from the perspective of educational analysis [

16].

Social participation and education are, moreover, recognized by the UNESCO

Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage [

17] as essential elements of the latter (henceforth, ICH). Compared to previous normative texts by UNESCO in relation to cultural and natural heritage [

18], the agency of individuals and communities in the safeguarding of heritage manifestations was then urged for the first time [

17,

19,

20]. To achieve this involvement, the UNESCO 2003 Convention stresses in its Article 14 the importance of education as a means to raise community awareness.

In the Spanish case, and despite Spain being one of the countries with the largest scientific output in relation to heritage education [

21,

22], the pedagogical component for ICH is paradoxically neglected. The National Plan for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage [

23] does not incorporate the term “education” and delegates the dissemination of ICH to associations, social groups and museum institutions, while Spain’s law for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, enacted in the same year, only recommends that educational action be taken in the field of formal education. However, in line with UNESCO’s approach and with that generally espoused by heritage education, it is necessary to consider multidisciplinary and multifocal educational strategies for ICH which jointly involve actors from formal, non-formal and informal settings [

24,

25]. Given that the co-creative paradigm has already proven to be a pedagogical approach capable of engaging museums and communities in social-awareness-raising actions around tangible heritage, one could safely expect that this emerging model has the potential to also extend its collaborative synergies to schools as well as to secondary and higher education institutions, in order to fill this important gap in ICH education.

Consequently, we wonder to what extent and in what way the co-creative paradigm, which has demonstrated its pedagogical potential in the context of non-formal education, can also be applicable to the educational processes for ICH developed in formal educational institutions. To this end, we will first discuss the characteristics and implications of the recent recognition of ICH and, more specifically, of this edu-communicative model, originally proposed for the analysis of museum actions in social media based on experiences observed in museums devoted to archaeology and the plastic arts [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

14,

26]. In order to respond to the possible application of the co-creative paradigm in formal and informal education for ICH, two autoethnographic cases are proposed in the following section, since one of the authors of this article is a professor at the University of Lleida (Lleida, Spain) who furthermore collaborates with the Trepat Museum (Tàrrega, Spain). Both cases exemplify the capability of the co-creative paradigm to revitalize and expand the very manifestations of ICH, strengthen education and citizen involvement in the offline and online spheres, and build collaborative bridges between museums and formal education institutions. While implying certain limitations, this convergence of binary poles stands out for its activation of heritage bonds and the construction of new shared meanings through what we have called a process of “rhizomatic identization”.

2. A Discussion-Friendly Theorical Framework: ICH, Museums and the Co-Creative Paradigm

The

Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage marks a turning point in the definition of heritage, which since the 19th century had been based on the historical–artistic—and, to a lesser extent, scientific—value of monuments and tangible assets [

27,

28]. In contrast to this Eurocentric conception, the new text shifts towards an understanding of heritage that not only stresses the intangibility and mutability of its manifestations, but also emphasizes the subjectivity of the values that are attributed to it. ICH is shaped through a process of attribution of values by individuals and communities, and therefore comes close to the relational sense of heritage proposed by heritage education around the days of the 2003 Convention [

29,

30]. Thus, the reality of heritage ceases to be encapsulated in an immanent noun to acquire a processual, changing and dialogical nature—that conveyed by the term “heritagization”, which inevitably requires the involvement of people and the identity and symbolic bonds that they establish with the assets in their environment [

31,

32].

The notion of heritagization as a process derived from the communicative bridges that are built between people shows the epistemological influence that Freire’s critical pedagogy exerts on the theorizations and practices that stem from heritage education [

33,

34,

35]. The sociocritical, dialogical and emancipatory sense that the Brazilian thinker required for every educational act [

9,

10] pervades both the nature that heritage education attributes to the teaching–learning processes and the very notion of heritage. With regard to education, this is so because such a sense permeates it by advocating that it should work dialogically and on the basis of the contextually situated concerns and interests of the learners [

33], therefore aspiring to form a critical citizenry capable of taking part in the improvement of their sociocultural environment [

35,

36]. With regard to heritage, on the other hand, its perception from a humanizing perspective is enhanced. This perception is shaped by the meanings, identities and affections that people place on heritage assets and therefore challenges the “heritage authorized discourse” that is solely legitimized by institutions [

28], replacing it by processes of socialization and strengthening of ties that result from a symbolic–communicative exchange [

29,

31,

32].

The institutional definition of ICH and the 2.0 results of the co-creative paradigm reflect the impact that this humanistic, discursive and problematizing turn is having in the field of heritage education and heritage studies. Therefore, the pedagogical model proposed for ICH education should be consistent with these foundations. Although co-creative approaches seem to be the most appropriate for promoting horizontal dialogue, the collective recreation of meanings and the consolidation of participatory communities demanded by “intangible heritage education”, in order to make such a claim it is necessary to first answer a series of controversial questions.

2.1. Can We Speak of Intangible Cultural Heritage?

The existence of ICH as a distinct reality within heritage phenomena has been widely debated. From the perspective of heritage studies and cultural anthropology, it has been argued that the 2003 Convention is problematic because it recognizes human culture in its broadest definition, thus valuing ICH as a metacultural production [

37,

38,

39,

40]. This critical tendency also points out the dangers of cultural objectification and institutionalization, which can denaturalize the original meaning that these sociocultural practices and manifestations originally had for the communities where they existed—because of their formalization and bureaucratization [

41,

42]. However, this “heritage phagocytization” of culture is being diagnosed on the basis of the axioms of the Global North: the 2003 Convention did not set out to devise a mere typology for heritage, but rather to incorporate into Western discourse a notion already existing in regions such as Japan, where the term

mukei bunzaki places value on certain intangible expressions of culture [

43]. From this point of view, there is an attempt to deconsecrate the concept of cultural heritage and secure protection for sociocultural phenomena that had previously been established as not needing any support from the community to perpetuate themselves [

39,

44,

45].

Similarly, in the fields of anthropology and cultural management, other perspectives have addressed the problematic distinction between ICH and other heritage typologies, such as ethnography or ethnology. Although it is true that what is understood as ICH coincides with what had traditionally been the object of study of ethnology, this conceptualization is nowadays freed from the ideological burden of this Western-based and positivist discipline [

38,

42,

46]. In this way, the ethnological concept of folklore should not be understood as equivalent to that of ICH, insofar as it derives from an approach that studies the sociocultural reality of the traditional and rural past as a justification for the identity-based specificities demanded by the nationalist ideologies of nineteenth-century Europe [

47].

A third group of critical authors—whose positions are close to a discursive and relational vision of heritage—have stressed that ICH is only the necessary extension of an institutional understanding of heritage, to date limited to alleged tangible and objective values [

20,

31]. Thus, regardless of the validity of this differentiation of tangible/intangible categories in operationalizing heritage management, from an ontological perspective, the definition for ICH provided by UNESCO is the one to be effectively recommended for the whole concept of heritage [

48,

49].

However, two counterarguments can be deployed to defend the need to consider ICH in a differentiated way in the field of heritage education. Firstly, and adapting the Cultural Values Model advocated by Stephenson [

50] for landscape interpretation, it can be observed that the 2003 Convention not only explicitly recognizes the relevance of

human relations and

practices as inherent parts of heritage, but also stresses the expression of these manifestations through

forms that pursue the same sensory purpose as material creations and result from the same process of value attribution. However, these forms are manifested as resulting from a very different materiality—a point made even by authors who have questioned the tangible heritage/intangible heritage dichotomy, but who accept the difference between autographic and allographic forms [

40]. Secondly, and as long as we aspire to a holistic treatment of heritage [

51] which educationally addresses these phenomena as part of the same comprehensive and complex system, heritage education should encourage the recognition and valuation of ICH on a par with tangible cultural heritage, thus overcoming the unequal status that is typically assigned to it by educators and learners [

52,

53,

54]. This means that the discipline should try to understand the specificities of ICH that provoke such a differentiated perception of heritage within the educational community and to promote didactic strategies aimed at the activation of bonds with the intangible [

55].

2.2. Can We Speak of Intangible Cultural Heritage Museums?

The recognition of ICH has been a fundamental driver of change in the nature of the museum institution in the 21st century [

19,

56,

57] by promoting the inclusion of community action and participation in accordance with the paradigms of the new museology [

58,

59,

60,

61]. Indeed, one of the main challenges for museums in safeguarding ICH is to achieve the effective participation of the community [

62,

63]. This point is critical if we are to take into account the identity-based and self-recognized sense of ICH, which, in turn, demands the democratization of the expert–non-expert dynamics that have generally prevailed in expositive languages [

64]. In order to achieve this transformation of the community–heritage–museum discourse links, several works have emphasized the potential of participatory models, such as the ecomuseum or the post-museum [

63,

65,

66], while also pointing out the need to attend to the museographic traditions of the creative communities within ICH [

67].

The intangible dimension is always present in museums, insofar as the contextualization of material assets involves attention to the sociocultural relations and practices that shaped their form [

68,

69]. However, there are those who claim that museums can be found where ICH constitutes the main focus of their discourse. On the one hand, ICH museums have been defined as spaces for ex profeso creation where “a particular ICH item is their main theme, the focus of museum work and what is to be expressed through the objects, activities and experiences” [

56] (p. 98). This tendency emphasizes the necessary participation of the creative communities that attribute value to such manifestations and gives rise to a model of the museum as a “third space”, a kind of hybrid between a cultural center and a meeting place for citizens [

70]. These theorists usually refer to recently created spaces, such as the Museo do Fado (Portugal), the Museo de Baile Flamenco (Spain) or the Museum Hof van Busleyden (Belgium) [

56,

70], which were established close to the 2003 Convention and therefore followed since their inception the institutional approaches to ICH. On the other hand, other authors advocate the possible reconversion of old ethnographic or ethnological collections as long as it becomes possible to deconstruct the top-down discourse of otherness previously sustained, thus accommodating the new cultural landscapes, interests and interventions of their communities [

41,

63,

65,

66].

2.3. Can We Speak of a Co-Creative Paradigm?

During the lockdown caused by COVID-19, the marketing orientation of museum discourses in social media inevitably shifted towards edu-communication processes in which cultural and educational action was completed entirely through such media. Edu-communication allows for the replacement of the “transmission” paradigm by another one based on the idea of “mediation” [

71]: one which revolves around the reappropriation of knowledge and reflects on interpretations in a relational way by emphasizing these processes within a freer space, focusing on the individual person in accordance with Freire’s proposals and taking into account the indispensable active participation of people [

3,

6,

7].

Along these lines, some authors have proposed that the notion of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) should be revised from a human and relational standpoint, i.e., transcending the instrumentalist conception; evolving from the unidirectional to the multiple and diverse, from the vertical to the horizontal; and moving from an elitist conception of school to the principle of education through social and cultural collaborative practices. Such an outlook is committed to the inclusion of the “R”, the essence of the relational factor, embedded in the term RICTs, an acronym for Relation, Information and Communication Technologies [

72,

73]. In the case of educational–communicative processes deployed in cyberspace, this entails profound changes focused on participation, creative collaboration and interaction in virtual environments [

74].

Participatory culture implies that individuals take control of social media and narrate their own discourses in their own settings, regardless of large companies, corporations and institutions. Therefore, it promotes the democratization and decolonization of heritage discourses. For the museum, it entails the renewal of practices, discourses and forms of organization and collective action. This new approach to understanding the museum narrative changes the traditional order of knowledge generation, in which it was the expert museum institution that created a story that it transmitted to recipients–users. The interactivity, interaction and accessibility that characterize 2.0 networks [

75] enable institutions to create an expanded universe of the heritage imaginary that calls for the co-creation of content together with users [

76].

This “participatory museum” 2.0, in which visitors socialize, share, create or resignify the contents of the institution, responds to a co-creative paradigm [

59,

61,

77] that can be embodied in social media through online communities [

78]. Eventually, it leads to the setting up of heritage cybercommunities which transfer into cyberspace the definition of heritage community promoted by the Faro Convention [

3].

The interaction with an edu-communicative purpose, when developed in social networks, generates a dynamic process where interventions feed back multidirectionally and knowledge is generated, following a model that we could call rhizomatic, according to Deleuze and Guattari [

79]. These authors’ thinking, with its notions of striated space and smooth space, provides us with rich possibilities for the analysis of the generation of knowledge through social media, where different relationships and different connections come into play. In a smooth space, such as the one afforded by social media, it is the trajectory that dominates the point. It is a non-plotted space that is dynamically defined according to transformation, events and affections.

In this sense, on the one hand, some authors have already pointed out the possible and ideal synergy between a participatory and dialogical use of social media and the safeguarding of ICH in non-formal settings [

80], since the correspondences that exist between these new digital and heritage paradigms are evident. On the other hand, although critical of formal teaching contexts, classical and contemporary theorists who have supported the tenets of edu-communication have likewise urged the latter’s use in classrooms [

9,

81]—a concern that we share in our line of research. The next step is to merge all of these elements: the co-creative paradigm, formal education, museums and ICH.

3. Cases of Intangible Extension of the Co-Creative Paradigm: Museum, Formal Education, Community

Throughout the 20th century, Spain experienced the mechanization of agricultural and industrial modes of production in an uneven process that involved the gradual transformation of previous ways of life and worldviews. It was at this socio-cultural junction that the J. Trepat agricultural machinery factory was founded. It began its operations in 1914 and experienced a period of expansion in the 1930s, when it became one of the state’s economic engines and revolutionized the way of working in the countryside. After its abandonment, the old factory was museumized just as it was on the last day it ceased to operate. Today, the museum strives to maintain its essence by showing inside its premises the tension between the agrarian and the industrialized ways of life, which nowadays have almost completely disappeared to make way for new models of production and consumption. This museum, which in principle we would call ethnological or industrial, clearly develops edu-communicative strategies around its legacy that make it a paradigmatic example of an ICH museum where education and community participation become its guiding principles.

One of the authors has established a long-term collaboration with the J. Trepat Factory Museum, working on the development of didactic activities in association with the University of Lleida (Spain). While theorizing about the co-creative paradigm within museum edu-communication [

16], it became evident that the experiences conducted at the Trepat Museum exemplified the co-creative potential, serving as a living example that expanded our understanding of the phenomenon of edu-communication. Autoethnography was then selected as our methodological approach due to its holistic orientation, which enables researchers to comprehend the entirety of their own memoirs and, consequently, to connect everyday experiences and analyze them through various techniques and tools [

82]. Furthermore, socialization scenarios are currently undergoing a transformation due to the impact of digital technologies, thus introducing new perspectives for ethnographic research [

83]. By adopting a constructivist research approach and aiming to discover how knowledge is constructed in two different media (online and offline), field notes derived from the participant observation of one of the authors (2021–2023) were analyzed and, subsequently, online posts and projects were subjected to observation to enrich our reflections.

The following are examples of several practices of special interest insofar as they promote strategies framed in the co-creative paradigm, provide keys to significant work around ICH and appeal to social participation. Such strategies can be extrapolated to formal education contexts as the ultimate goal of our work.

3.1. Case 1: Rhizomatic Learning at the Trepat Factory Museum: Social Media, Formal Education and Community

The first case to be highlighted was initiated by the 2.0 activity of the Trepat Factory Museum itself. In this case, a path is woven that starts with the dissemination of the museum’s project through social media and goes on to forge collaborative projects with secondary schools and higher education.

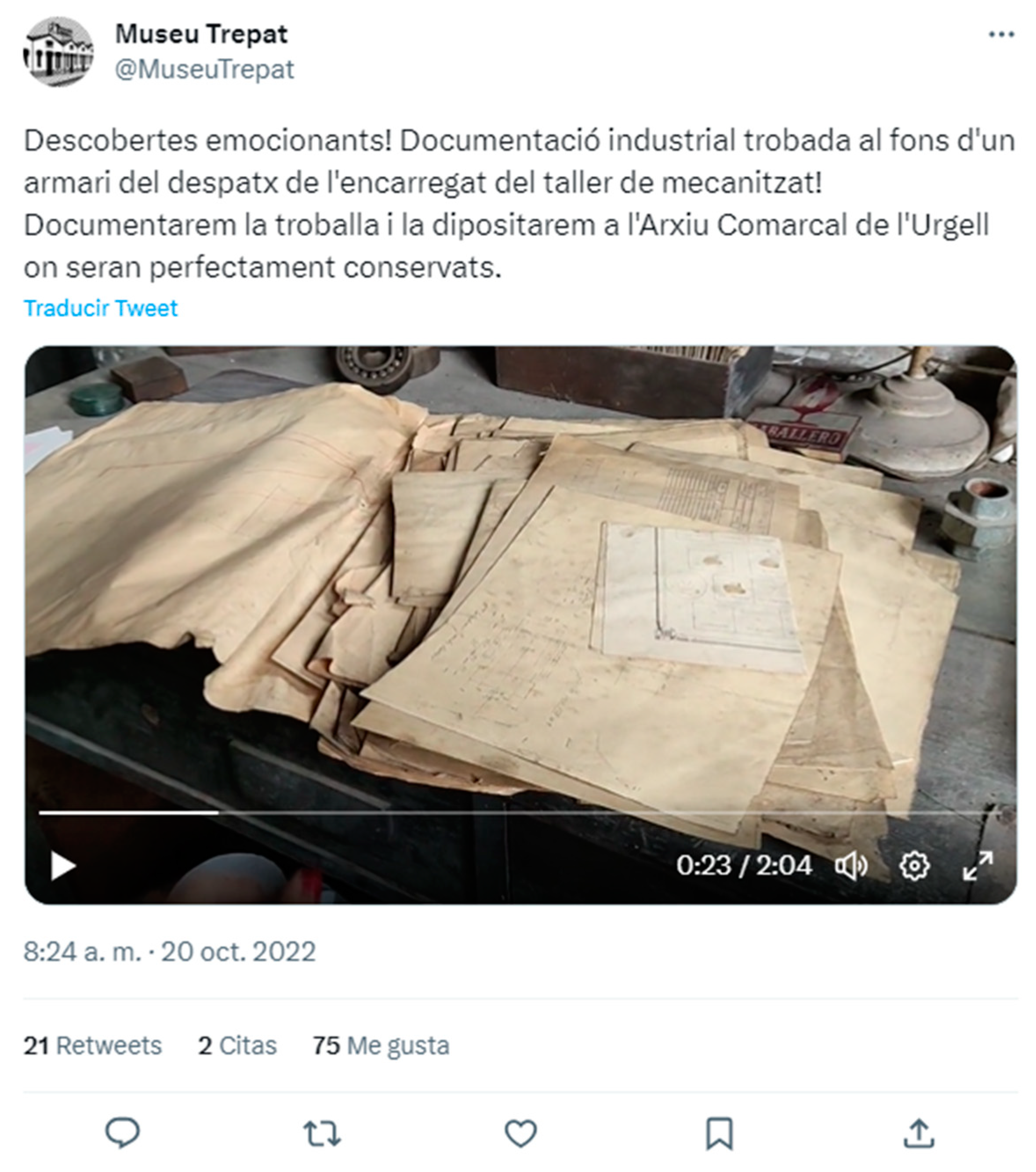

On 20 October 2022, the J. Trepat Factory Museum posted the following tweet:

“Exciting finds! Industrial documentation found in the back of a cabinet in the office of the person in charge of the machining workshop. We will document what we found and deposit it in the Regional Archive of Urgell where it will be perfectly preserved.” (

Figure 1)

The discovered file contained unpublished information related to the annual record of accidents that took place in the old factory, as well as graphic diagrams depicting the operation of industrial machines and the work that could be performed with them. From this tweet, a kind of synergy followed whereby the community of Tàrrega echoed the discovery. The museum received Whatsapps and emails from many people interested in the documents found, and this motivation brought with it the opportunity to start collaborative work with the community based on the rhizomatic model of Deleuze and Guattari.

Figure 1.

Tweet published by the J. Trepat Factory Museum communicating the discovery of the documentation: “Exciting finds! Industrial documentation found in the back of a cabinet in the office of the person in charge of the machining workshop. We will document what we found and deposit it in the Regional Archive of Urgell where it will be perfectly preserved”.

Figure 1.

Tweet published by the J. Trepat Factory Museum communicating the discovery of the documentation: “Exciting finds! Industrial documentation found in the back of a cabinet in the office of the person in charge of the machining workshop. We will document what we found and deposit it in the Regional Archive of Urgell where it will be perfectly preserved”.

As a result of the interest aroused by the various 2.0 notifications that fed this thread of inquiry, members of the community who had not previously visited the museum approached the institution to discover the role played by the regional archive in the custody of documents. Following all this research work and the engagement and interaction of users both virtually and in person with the museum, as well as the latter’s collection and work, the staff of the J. Trepat Factory Museum included in its narrative a collaborative proposal so that the local community could visit the museum to discover and share the findings. At the same time, audiovisual material was created that complements the documentation with oral testimonies of people from the community who had worked in the factory, thus co-constructing the story with the voices of the protagonists. The outcome of this co-creative action is currently exhibited in the museum–factory and is available on YouTube.

Due to the success of the educational visits around the workplace accidents in the old factory, the museum has continued to generate new learning proposals in the sphere of formal education. On 10 February 2023, an experience was launched for secondary-school students where this human narrative guides the visit to the J. Trepat Factory Museum as well as serving as a bridge to other skills and knowledge. Likewise, the museum encourages thought processes around social inclusion, leading students to consider the presence of different languages in social spaces and introducing experiences around the Braille alphabet—eye injuries caused by welding are some of the most frequently mentioned in the documents.

As a result of the impact of its 2.0 edu-communicative proposal, the Trepat Museum also started collaborating with formal higher education institutions within the framework of the project

El museu és escola (“The Museum is a School”), run by the University of Lleida (Spain). This project is based on the installation

The museum is a school; the artist learns to communicate, the public learns to make connections, a collaborative creation by Uruguayan activist and artist Luis Canmitzer: art—heritage in this case—is a dialogical process involving continuous reconstruction made possible by the social environment provided by the museum itself. Against this backdrop, the Spanish university is developing a project-based learning proposal which is materializing itself in the Trepat Museum. Among the educational experiences proposed by the students, mention must be made of

The Trepat Diagnosis, an installation that seeks to encourage reflection on working conditions in factories based on the data discovered in the museum’s mechanization facility (

Figure 2). In this way, the 2.0 thread initiated by the museum continues to be woven by the students and generates projects that address other aspects of the intangible heritage rescued by the Trepat Museum—from mowing techniques to technical vocabulary at risk of disappearing to women’s clothing.

3.2. Case 2: Bridges for the Transmission and Recreation of ICH: Museums, Formal Education and Community

This type of rhizomatic formation, initially planted by the Trepat Museum and fertilized by the University of Lleida, produced other ramifications involving different institutions. Let us highlight the partnership with the Asociación de Festes del Segar i Batre (Association of the Harvest and Threshing Festival), in charge of commemorating the namesake festivals since 1988 that recall the agricultural tasks that were regularly carried out until the twentieth century. As part of this synergy, the museum has been conducting interviews with older people who used to be involved in farming tasks and experienced this way of life. In this manner, the oral memory is compiled, with a special emphasis on the experiences of women, in order to make visible alternative discourses and narratives about agricultural life, which was traditionally masculinized. In 2015, the University of Lleida joined this partnership, and this initiative materialized itself in 2019 in the project “Presence and Absence of Women in the Trepat Factory”. And in 2022, within the framework of the project “The Museum is a School”, a group of pre-service teachers wove a new project around the wheat culture because one of the members of this group happened to come from a family who used to work in an old flour mill, so that hereditary ties were foregrounded in this project.

In parallel, within the Trepat Factory Museum, one of the signatories of this paper coordinates the project “Museums and Collections in the villages of the Segrià region in Lleida”, promoted by the Consell Comarcal del Segrià. The aim of this project is to make visible the local heritage created at an individual, family or community level. One of these collections is the private museum of Pepe Guillermo in Almatret (Lleida, Spain). Pepe Guillermo has collected and exhibited numerous farm tools used for sowing, harvesting and threshing wheat, while recovering several terms related to these traditional tasks (

Figure 3).

This collection was shown to a group of students of the University of Lleida by its owner, whose efforts in preserving agricultural terms of yore awakened in the group the motivation to undertake the “Beyond Words” project—after realizing that the same tool could take different names in different locations, even when the latter were geographically close. “Beyond Words” is a digital and interactive proposal, where users can add the different words they know which designate farming tools. And once again, from this initiative, new synergies unfolded, as this group of students visited the exhibition D’escriure la terra (“Of writing the land”) by artist Jaume Geli, an event hosted at the “Espai Guinovart” in Agramunt (Lleida, Spain). The exhibition explores the process of deconstruction of the words that are being lost in the agricultural areas of Lleida and generates creations that aim to build new community narratives that, in turn, give rise to new heritage assets. “The word is born from the need to name a new tool, but when this is no longer used, it seems as if the earth had swallowed it up”, claimed the artist. In addition, the students’ experience was complemented by a visit to the “Lo Pardal-Guillem Viladot Foundation”, where various everyday objects—including agricultural tools—become the protagonists of visual poems that play with letters and alphabets.

As a result of both museum experiences, the students created

Art Era—playing with the double meaning of the word “era”, which in Catalonia refers to a piece of land used for farming and threshing. It is a learning environment located outside the Trepat Museum that simulates a cemetery, in which the country tools are half-buried, signifying the (in)visibility of the words that name them while inviting viewers to dig them up and recover their use. This project, in turn, engaged the participation of the sixth-grade boys and girls from the Jacint Verdaguer elementary school in Tarrega. Moreover, these co-construction initiatives elicited in parallel a new collaboration with students of a bachelor’s degree in digital design and creative technologies. They developed the project

Mechanical Metamorphosis to digitally show the transformation of the tools used for manual sowing and harvesting into the mechanization brought about by the Trepat machines (

Figure 4). Both projects have recently traveled to the Pepe Guillermo Museum in Almatret, where they are being shared with the community in the course of a festive event that aims to continue collecting new testimonies and diverse voices for intangible cultural heritage.

Finally, it should be noted that the exposure of this event in social media has caused the Asociación de Festes del Segar i Batre to become interested in the projects developed at the Trepat Factory and request the presence of both “Art Era” and “Mechanical Metaformosis” in the upcoming 2024 edition of these festivals, thus nourishing these synergies further.

4. Discussion

Digitally co-creative museums and schools provide us with the opportunity to rethink the roles of their actors and reflect on their own organizations. This is not about either or both institutions losing their status, since “the social web does not presuppose the disappearance of the exercise of power, but its reformulation into other models suited to the operational logic of the digital medium” [

84] (p. 29, our translation). It is a matter of establishing a different type of interaction between users, in a smooth space of communication where knowledge is co-created in the rhizomatic manner enunciated by Deleuze and Guattari [

79]. As has been seen in the cases collected, this type of knowledge construction can occur autonomously, without previous approaches or triggers for these synergies to take place; sometimes there is an initial trigger that leads to the development of events that we cannot even envisage but that undoubtedly enrich the whole process. In this way, Web 2.0 spaces become co-creation meeting points for users and institutions: they act as bridges that connect and multiply, on the basis of informal edu-communicative strategies, the pedagogical and social impacts of museums and formal educational establishments, as well as the inherent qualities of ICH.

In relation to the intangible manifestations of heritage, and due to their difficult preservation and documentation (which ultimately depend, to a large extent, on community awareness and commitment), the implementation of the co-creative paradigm is certainly important, since it ensures that the socio-cultural realities of the past are updated, resignified and expanded intergenerationally through the bonds that people forge with them. In addition, it should be noted that this process of co-creation makes it possible to recover the testimonies that build up a more comprehensive and plural, and therefore richer, picture of the ICH. Thanks to this paradigm, the hierarchical configuration of heritage discourse is inverted, or rather becomes multidirectional and isocephalic, as can be seen in the Art Era project. It is the interests and affections of learners that modify the narratives of various museum institutions in a process that brings together the voices of the entire community, in order to subsequently devolve to the latter new meanings and values. By directly impacting the communities through the contents and meanings exhibited by the museum, the institution becomes an ICH museum and succeeds in including citizen participation, so that the Trepat Factory, as a museum, becomes completely interconnected with the ICH of the Festes del Segar i Batre and Pepe’s collection.

Likewise, heritage edu-communication affords the opportunity for ICH to be reactivated, updated and even transformed into new modes of cultural expression by refreshing bonds that provide a creative impulse for contemporary forms of symbolic communication [

31]. However, it is worth asking ourselves whether the bonds that these expanded communities forge with such an updated heritage will really manage to endure over time in a sustainable manner [

62,

80]. As happens with the material manifestations of heritage, the conservation of ICH needs to be educationally addressed in great depth at all levels of the heritagization sequence [

30,

32]. In order for individuals and communities to commit themselves to its care and transmission, it must first be understood, valued and ingrained in public awareness. However, the transmission of ICH requires its effective, periodical and regular performance, which sometimes involves conceptual and procedural knowledge, technical means and highly specific attitudes. The spontaneous and often ephemeral nature of non-formal and informal 2.0 interactions does not necessarily guarantee the development of these competencies [

80]. Consequently, the effects of the co-creative paradigm will be enhanced if primary and secondary schools, as well as universities, are fully involved, since their structured and stable status as traditionally striated spaces will make it possible to overcome the shortcomings of ICH conservation—as observed in both cases.

Despite the observed weaknesses, the cases presented here prove that constructing a triad that combines ICH and formal teaching–learning processes with online edu-communication has an identity-building potential that goes beyond that diagnosed in social media around museumized archaeological or artistic heritage [

14,

26]. Those analyses stressed that the existence of emotional and identity bonds with local heritage were a necessary condition for the creation of cybercommunities [

3]: users had already internalized as heritage the assets they discussed, shared and created via Web 2.0 and had symbolically appropriated them through an identization process that gave rise to an online community [

32]. In the case of the J. Trepat Factory Museum, the heritagization process had not even begun in some of its edu-communication proposals, in which citizens (re)discovered and visited the museum for the first time following a Twitter post, or students generated research and created projects after learning about agricultural tools and words that were new to them. Even so, authentic identification processes collectively sprouted from these small stems of the rhizome, in which discussion, reconstruction and consensus around heritage values built online and offline communities. To the rhizomatic learning outcomes that derive from edu-communication in social media, one should add the potential for “rhizomatic identization”.

Even so, we must not forget that both rhizomatic learning and identization are only potential benefits of edu-communication. This is revealed by the initiatives collected here. The growth of the rhizome in the formal sphere apparently stops at this ramification, since we do not know if the involvement of the students is perpetuated beyond the museum spaces or leads to new prosocial actions. To achieve the complete flourishing of these proposals—whether they are incorporated into formal education institutions or limited only to the scope of the museum; whether they are specifically intended for the intangible or for other types of heritage manifestations—thoughtful planning around their pedagogical objectives [

6,

7,

14] along with the willingness of the participants to adopt principles of dialogue compatible with the co-creative paradigm are sine qua non conditions.

All of these considerations lead us to raise new interesting questions to be explored in future research: What trajectory do the groups involved in these processes continue to follow either jointly or along new ramifications? What happens as a result of this trigger, or how do synergies lead over time to actions or events that may be interrelated? How will these participants specifically design their future praxis in formal education? Will they be able to generate contexts of co-creation with the environment, museums and ICH so as to significantly affect the development of the school curriculum?

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

The co-creative paradigm theorized on the basis of museum 2.0 edu-communication practices reveals itself to be capable of being transferred to formal education settings as a pedagogical model aimed at consolidating heritagization, identization and community participation processes around ICH. In this way, the edu-communicative model contributes to addressing some of the issues tagged as priorities in education for ICH: the intergenerational transmission of knowledge, procedures and attitudes; the focus on multiculturalism and on the diverse understandings and valuations of heritage; and the sustainable preservation of these manifestations for the purpose of social and environmental advancement [

25]. The cases presented also show that this synergy between institutions can provide keys to overcome the possible limitations of the co-creative paradigm in non-formal settings: the non-perpetuation over time of learning relevant to the safeguarding of ICH and of the communities generated around this learning.

Moreover, co-creative practices prove to be capable of integrating past worldviews and identities with contemporary experiences and identity resignifications. They manage to distance the ICH and its educational understanding from the folklorist, traditionalist and rural vision that has usually been attributed to these manifestations, to show how the activation of links between (cyber)heritage communities gives rise to intellectual exchange, artistic creation and the generation of new shared symbolic referents. These practices are generated through encounters with contemporary artistic practices, as these encounters have the capacity to generate ruptures in our ways of being and acting. It becomes clear that when contemporary art breaks into heritage, it allows us to generate projects that lead to the production of more heritage. This point of view proposes that heritage should be considered a zone of uncertainty, in which a future for educational, social and community transformation can be forged.

This work has been intended as a first reflection, in the way of an exploratory approach, on the educational and creative potential derived from the ICH–edu-communication 2.0 symbiosis. However, this exploration has only been possible through first-hand knowledge of socio-cultural phenomena in which the authors are involved participants. Consequently, for the moment, (auto)ethnography or case studies are the only methodologies capable of making visible and interpreting the co-creative actions that link the museum and the school, given that the institutions do not make known to the digital public the practices developed with other centers, communities and individuals as a result of the edu-communicative action in social media. This article aims to highlight the value of this type of 2.0 pedagogical practices, whose proper planning, evaluation and dissemination should be considered by museum managers and educators as part of the social impact of their institutions.

Continuing to delve into the potentialities and shortcomings observed in the interaction between museums, local communities and schools requires extending our gaze nationally and internationally into other co-creation experiences around ICH, following the example of the research already conducted on the topic of edu-communication via museums’ social media. This implies considering not only the pedagogical and relational meaning of the messages intended to edu-communicate for ICH, but also the inherent characteristics of the media and channels where these proposals are materialized—social media, collaborative applications, hybrid contexts, etc. On the other hand, the different impacts of the co-creative proposals carried out among students encourage us to explore the factors responsible for their uneven reception through qualitative analyses, focusing on the heritage and pedagogical conceptions of teachers and students involved in education for ICH. If these results contribute to consolidating the co-creative paradigm for ICH, a bridge will be laid across the artificially created gap between non-formal education and formal education and progress will be made towards a discursive, relational and holistic conception of heritage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R., G.J.-M. and A.R.-N.; Methodology, G.J.-M.; Formal Analysis, P.R., G.J.-M. and A.R.-N.; Investigation, P.R., G.J.-M. and A.R.-N.; Resources, G.J.-M.; Data Curation, G.J.-M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, G.J.-M. and A.R.-N.; Writing—Review & Editing, P.R., G.J.-M. and A.R.-N.; Visualization, A.R.-N.; Supervision, P.R. and G.J.-M.; Project Administration, P.R. and G.J.-M.; Funding Acquisition, P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was funded by the Ministerio de Universidades (Spain)–Ayudas para la Formación de Profesorado Universitario (FPU), grant number FPU21/06564, as part of a predoctoral research project. Besides, this research project was funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, PID2020-115288RB-I00: “Competencias Digitales, procesos de aprendizaje y toma de conciencia sobre el patrimonio cultural: educación de calidad para ciudades y comunidades sostenibles”, and by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR TED2021-131174B-I00 “Herramientas digitales participativas para el apoyo a cibercomunidades patrimoniales”.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created. The analyzed art projects are openly and voluntarily displayed online and can be found on the website

https://museuesunaescola.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 28 September 2023).

Acknowledgments

This article has been possible thanks to the University Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences of Aragón (IUCA) at the University of Zaragoza and the research group ARGOS (S50_23R), as well as the research collaboration developed in the framework of RED2022-134252-T. RED14—Red de investigación en enseñanza de las ciencias sociales (MCIN/AEI 10.13039/501100011033). The authors also acknowledge the support received from Roser Miarnau (Museu Fabrica Trepat de Tárrega, Spain); the Consell Comarcal del Segrià for the project “Museum and Collections in the villages of the Segrià region in Lleida”; the private museum of Pepe Guillermo in Almatret (Lleida, Spain); and the students from the University of Lleida who created the projects “The Trepat Diagnosis”, “Art era” and “Mechanical Metamorphosis”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agostino, D.; Arnaboldi, M.; Lampis, A. Italian State Museums during the COVID-19 Crisis: From Onsite Closure to Online Openness. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2020, 35, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, E.; Beresford, A.M.; Warwick, C.; Impett, L. Understanding Levels of Online Participation in the U.K. Museum Sector. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, P.; Navarro-Neri, I.; García-Ceballos, S.; Aso, B. Spanish Archaeological Museums during COVID-19 (2020): An Edu-Communicative Analysis of Their Activity on Twitter through the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, J.; McAvoy, E.N.; Ostrowska, A. Negotiating Hybridity, Inequality, and Hyper-Visibility: Museums and Galleries’ Social Media Response to The COVID-19 Pandemic. Cult. Trends 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ceballos, S.; Rivero, P.; Molina-Puche, S.; Navarro-Neri, I. Educommunication and Archaeological Heritage in Italy and Spain: An Analysis of Institutions’ Use of Twitter, Sustainability, and Citizen Participation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aso, B. Los Museos de Arte Contemporáneo En Las Redes Sociales: Educomunicación Web 2.0. In Ciencias Sociales, Educación y Futuro. Investigaciones en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales: VII Simposio Internacional de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales en el Ámbito Iberoamericano; López-Facal, R., Ed.; Red14—Universidad de Santiago de Compostela: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2017; pp. 780–791. [Google Scholar]

- Aso, B.; García-Ceballos, S.; Rivero, P. La Educomunicación Web 2.0 de Los Museos En La Sociedad Digital. In Re-Visiones Sobre Arte, Patrimonio y Tecnología en la Era Digital; Foradada, C., Irala-Hortal, P., Eds.; Gobierno de Aragón: Zaragoza, Spain, 2019; pp. 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Cáceres, M.J.; Cuenca, J.M. Educomunicación Del Patrimonio. Educ. Siglo XXI 2015, 33, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogía del Oprimido; Siglo XXI Editores: Mexico City, Mexico, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. ¿Extensión o Comunicación? La Concientización en el Medio Rural; Siglo XXI Editores: Mexico City, Mexico, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplún, M. Una Pedagogía de La Comunicación; Ediciones de la Torre: Madrid, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Barbas, Á. Educomunicación: Desarrollo, Enfoques y Desafíos En Un Mundo Interconectado. Foro Educ. 2012, 10, 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Aparici, R.; Silva, M. Pedagogy of Interactivity. Comunicar 2012, 19, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aso, B. Educación Patrimonial En Tiempos Digitales: Estudio de La Educomunicación EN Redes Sociales del Museo Diocesano de Jaca. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society; Council of Europe: Faro, Portugal, 2005; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Rivero, P.; Jové, G.; Sebastian, C. Educomunicación En Las Redes Sociales de Los Museos En La Era Post Covid: El Paradigma Co-Creativo. Her Mus Herit. Museography 2021, 22, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2003; Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/2003_Convention_Basic_Texts-_2022_version-EN_.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Blake, J. Museums and Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage—Facilitating Participation and Strengthening Their Function in Society. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2018, 13, 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.; Campbell, G. The Tautology of “Intangible Values” and the Misrecognition of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Herit. Soc. 2017, 10, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontal, O. Educación Patrimonial: Retrospectiva y Prospectivas Para La Próxima Década. Estud. Pedagóg. 2016, 42, 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontal, O.; Ibañez-Etxeberria, A. Research on Heritage Education. Evolution and Current State through Analysis of High Impact Indicators. Rev. Educ. 2017, 375, 184–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Plan Nacional de Salvaguardia Del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/planes-nacionales/planes-nacionales/salvaguardia-patrimonio-cultural-inmaterial.html (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Fontal, O.; Martínez-Rodríguez, M. Evaluation of Educational Programmes on Intangible Cultural Heritage. Estud. Pedagóg. 2017, 43, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrador, A.M. Integrating ICH and Education: A Review of Converging Theories and Methods. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2022, 17, 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Neri, I. Educomunicación En Twitter de Los Museos Arqueológicos Españoles: Estudio de Estrategias de Educación Patrimonial. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Choay, F. L’Allégorie Du Patrimoine, 1st ed.; Éditions du Seuil: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontal, O. La Educación Patrimonial: Teoría y Práctica Para El Aula, El Museo e Internet; Trea: Gijón, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fontal, O. La Educación Patrimonial: Del Patrimonio a Las Personas; Trea: Gijón, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fontal, O. La Educación Patrimonial Centrada En Los Vínculos: El Origami de Bienes, Valores y Personas; Trea: Gijón, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fontal, O.; Gómez-Redondo, C. Heritage Education and Heritagization Processes: SHEO Metodology for Educational Programs Evaluation. Interchange 2016, 47, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolentinho, Á. Patrimonial Education in School, with School and beyond School: A Conversation with Teachers in Dialogue with Paulo Freire. Cad. Sociomuseologia 2022, 63, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scifoni, S. Heritage and Education in Brazil: What Is New? Educ. Soc. 2022, 43, e255310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S. Cultural Heritage Education: Cultural Lectures for Citizenship. Estud. Pedagóg. 2006, 32, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, J.M.; Martín-Cáceres, M.J.; Estepa, J. Teacher Training in Heritage Education: Good Practices for Citizenship Education. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendix, R. Heritage between Economy and Politics: An Assessment from the Perspective of Cultural Anthropology. In Intangible Heritage; Smith, L., Akagawa, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, C. La Problemática Del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. Culturas. Rev. Gest. Cult. 2014, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafstein, V.T. Learning to Live with ICH: Diagnosis and Treatment. In UNESCO on the Ground: Local Perspectives on Intangible Cultural Heritage; Foster, M.D., Gilman, L., Eds.; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2015; pp. 143–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. Intangible Heritage as Metacultural Production. Mus. Int. 2014, 66, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivizatou, M. Intangible Heritage and Erasure: Rethinking Cultural Preservation and Contemporary Museum Practice. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2011, 18, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, C. Globalising Intangible Cultural Heritage? Between International Arenas and Local Appropriations. In Heritage and Globalisation; Labadi, S., Long, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurin, R. Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage in the 2003 UNESCO Convention: A Critical Appraisal. Mus. Int. 2004, 56, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizpe, L. Intangible Cultural Heritage, Diversity and Coherence. Mus. Int. 2004, 56, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzerini, F. Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Living Culture of Peoples. Eur. J. Int. Law 2011, 22, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torantore, J.L. Du Patrimoine Ethnologique Au Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel: Suivre La Voie Politique de L’Immatérialité Culturelle. In Le Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel: Enjeux d’une Nouvelle Catégorie; Bortolotto, C., Ed.; Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de L’homme: París, France, 2011; pp. 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, A.B. Ethnographic Museums and Intangible Cultural Heritage Return to Our Roots. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 2016, 5, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggles, D.F.; Silverman, H. From Tangible to Intangible Heritage. In Intangible Heritage Embodied; Silverman, H., Ruggles, D.F., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Akagawa, N. Introduction. In Intangible Heritage; Smith, L., Akagawa, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, J. The Cultural Values Model: An Integrated Approach to Values in Landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, J.M. El Patrimonio en La Didáctica de Las Ciencias Sociales: Análisis de Concepciones, Dificultades y Obstáculos para su Integración en La Enseñanza Obligatoria. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Huelva, Huelva, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Fernández, B.; Castro-Calviño, L.; Conde-Miguélez, J.; López-Facal, R. Concepciones Del Profesorado Sobre El Uso Educativo Del Patrimonio. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2020, 95, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, J.A.; Medina, S.; López, M.J.; García-Morís, R. Perceptions of Heritage among Students of Early Childhood and Primary Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Cepeda, S.; Fontal, O. Secondary Education Student’s Perceptions around Heritage. Arte Individuo Soc. 2021, 33, 917–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, M. La Educación Patrimonial Inmaterial: Análisis Del Currículo y Evaluación de Programas. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Yulfo, A. Transforming Museum Education Through Intangible Cultural Heritage. J. Mus. Educ. 2022, 47, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K. The Museum and the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Mus. Int. 2004, 56, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. Museums and Education: Purpose, Pedagogy, Performance, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience Revisited, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, V.; Gray, C. Museums and the ‘New Museology’: Theory, Practice and Organisational Change. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2014, 29, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N. The Participatory Museum; Museum 2.0: Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, J. Engaging “Communities, Groups and Individuals” in the International Mechanisms of the 2003 Intangible Heritage Convention. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2019, 26, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A. Os Museus e o Patrímónio Cultural Imaterial. Algumas Considerações. In Ensaios e Práticas em Museologia; Semedo, A., Costa, P., Eds.; Universidade do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2011; pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, C. ICH and Safeguarding: Museums and Contemporary ICH. In Research Handbook on Contemporary Intangible Cultural Heritage: Law and Heritage; Waelde, C., Cummings, C., Pravis, M., Enright, H., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 273–293. [Google Scholar]

- Alivizatou, M. Intangible Heritage and the Museum: New Perspectives on Cultural Preservation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes-Giménez, M.V. La Musealización Del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kreps, C. Indigenous Curation, Museums, and Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Intangible Heritage; Smith, L., Akagawa, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Burden, M. Museums and Intangible Heritage: The Case Study of the Afrikaans Language Museums. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2007, 2, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Stefano, M.L. Safeguarding Intangible Heritage: Five Key Obstacles Facing Museums of the Nort East of England. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2009, 4, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić Đerić, T.; Neyrinck, J.; Seghers, E.; Tsakiridis, E. Museums and Intangible Cultural Heritage: Towards a Third Space in the Heritage Sector; Werkpaats Immaterieel Erfgoed: Bruges, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marta-Lazo, C. Education and Communication Compass. Rev. Mediterr. Comun. 2018, 9, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabelas, J.A.; Marta-Lazo, C.; Aranda, D. Por Qué Las TRIC y No Las TIC. COMeIN 2012, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabelas, J.A.; Marta-Lazo, C. La Era TRIC: Factor Relacional y Educomunicación; Egregius: Sevilla, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marfil-Carmona, R.; Hergueta Covacho, E.; Villalonga Gómez, C. El Factor Relacional Como Elemento Estratégico en La Comunicación Publicitaria. Anàlisi Quad. Comum. Cult. 2015, 52, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Sánchez, I. Interactividad, Interacción y Accesibilidad En El Museo Transmedia. ZER Rev. Estud. Comun. 2015, 20, 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, M. La Mediación Social; Ediciones Akal: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca-Amigo, M.; Zabala-Inchaurraga, Z. Reflexiones obre La Participación como Co-Creación en El Museo. Her Mus Herit. Museography 2018, 19, 122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Atochero, A. Ciberantropología. Cultura 2.0; Editorial UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F. Mille Plateaux: Capitalisme et Schizophrénie; Les Éditions de Minuit: Paris, France, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Stuedahl, D.; Mörtberg, C. Heritage Knowledge, Social Media and The Sustainability of The Intangible. In Heritage and Social Media: Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture; Giaccardi, E., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Marta-Lazo, C.; Gabelas, J.A. Diálogos Posdigitales: Las TRIC como Medios para La Transformación Social; Editorial Gedisa: Zaragoza, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, P.; Delamont, S.; Housley, W. Contours of Culture. Complex Ethnography and the Ethnography of Complexity; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Figaredo, D. Escenarios Híbridos, Narrativas Transmedia, Etnografía Expandida. Rev. Antropol. Soc. 2012, 21, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ortega, N. Discursos y Narrativas Digitales desde La Perspectiva de La Museología Crítica. Mus. Territ. 2011, 4, 14–29. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).