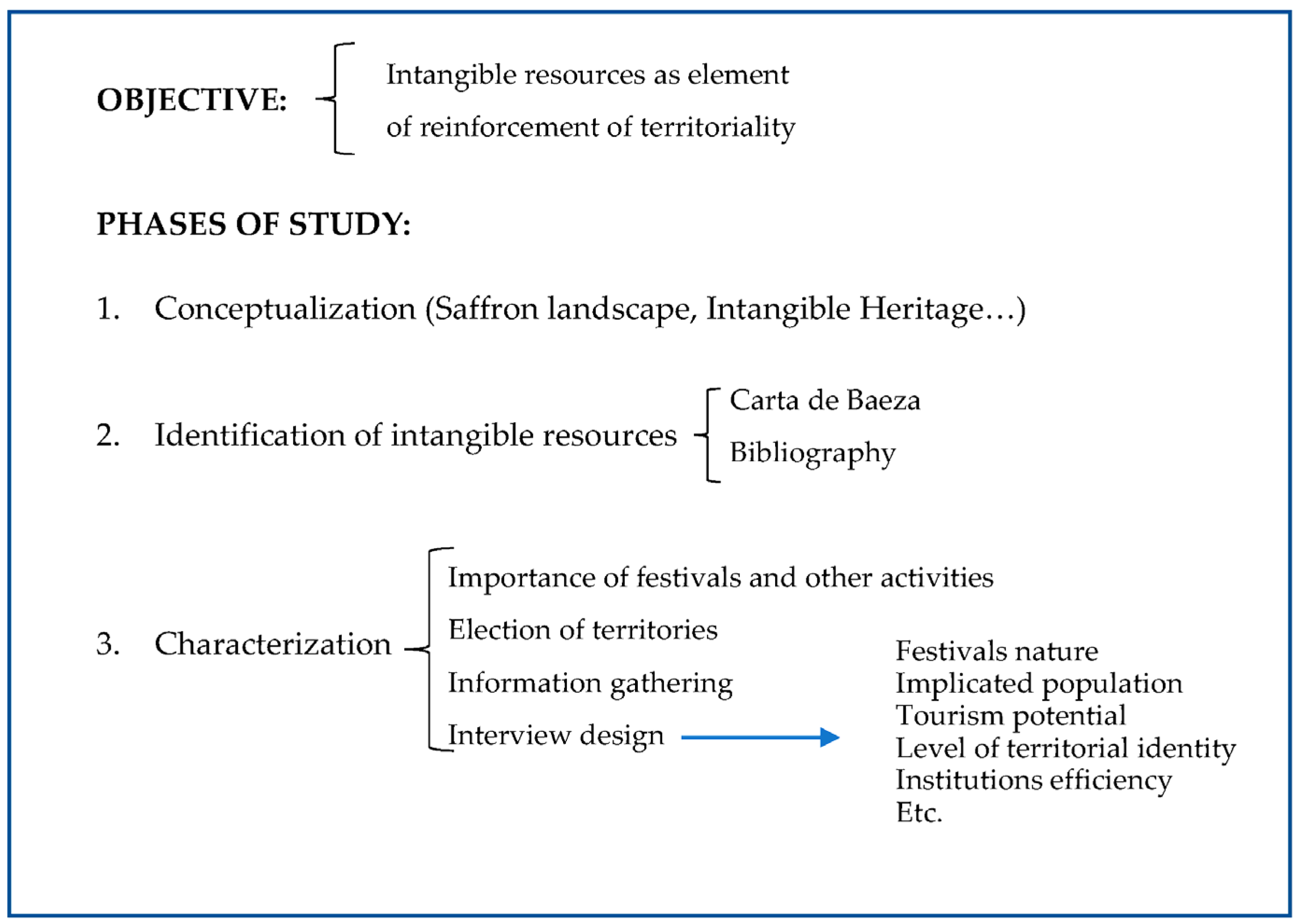

3.1. Saffron Cultivation in Castilla-La Mancha (Spain): General Characterisation

Since the beginning of the last century, saffron cultivation in Spain has been slowly declining, and it has disappeared in some regions in the interior of the country. The reasons for this are related to the dynamics of the rural areas themselves (priorities of the Common Agricultural Policy, labour shortages, etc.), together with competition from international markets. The graph below (

Figure 2) shows that, in the short period shown, there was a slight upward trend in the cultivated area, which has stabilised at around 180–200 hectares in recent years, with a slight decrease in the last year for which we have data (2020). Production has fallen sharply since 2016, mainly due to climatic factors such as the lack of rainfall and higher temperatures in September and October, not to mention the low yields generally obtained in the first and second year of the harvest cycle.

In 2020, of the total area (196 hectares), approximately 90% was in the Castilla-La Mancha region, with 156 hectares dedicated to saffron cultivation. Geographical factors such as the optimal physical and chemical conditions of the soil, the adaptation of the crop to the climatic rigours of an inland Mediterranean climate, and other social and historical factors, favour its concentration in some central areas of the region, as can be seen in the following map with information on cultivation area and production in the municipalities included in the “La Mancha Saffron” (Azafrán de La Mancha) Protected Designation of Origin seal of quality, to which we will refer later on and whose towns are shown on the following maps (

Figure 3).

As we can see, in terms of the surface area dedicated to this crop, the areas around towns such as Villafranca de los Caballeros, in the province of Toledo, have the largest area with 16.96 hectares in 2021, as does Motilla del Palancar with 12.8 hectares, in the province of Cuenca, together with Pétrola with 9.66, Fuensanta with 7.51 and Munera with 6.67, all of them in the province of Albacete. In production, the same municipalities also produce the most, although their order varies: Motilla del Palancar with 65,267.91 kg in 2021, Villafranca de los Caballeros with 52,060.63 kg and Pétrola with 24,558.97 kg.

The periods of activity in the annual saffron cycle are defined by the planting and harvesting of the flower, with the latter being the most labour-intensive process, as it needs to be carried out by hand. It is a task that has to be carried out within a period of ten days to two weeks, in addition to extracting and toasting the stamens on the day they are picked [

20]. The production on each farm is usually in five-year cycles: the corms are planted in the first year and the yield is usually zero; optimum production is then reached in the second and third years, after which it declines in the following years. The corms (underground stems) are usually lifted after the fifth year or even earlier. The flowers emerge during the short flowering period, and yields usually range from 1.5 to 4 kg per hectare per day.

The general pattern of cultivation (

Figure 4) has been repeated for decades, as it is associated with small farms located on the outskirts of population centres that have optimum-quality land combining deep and permeable clay soils that are sensitive to problems of waterlogging and aeration, and that are well adapted to drought; specifically, with a minimum requirement of between 150 and 200 L of rainfall per year [

21].

The ownership structure is related to the existence of large landowners who were not interested in the mobility of day labourer families, so they encouraged these small family farms with a heavy manual workload focused on preparing the fields, harvesting, extracting and final toasting the stigmas. Furthermore, saffron cultivation can be easily combined with other crops, such as cereals, without hindering the need for labour. Currently, it is estimated that only 20% of producers are exclusively dedicated to saffron [

3]. The income obtained from its cultivation confirms this relationship, as 70% of the producers declare that saffron accounts for less than 20% of their annual income, in a context defined by a continued reduction in the number of producers that is small but constant. Historically, it has been considered a “savings product” because, after drying, its conservation was assured for a period that could last for several years, an aspect which, together with its high economic value in relation to its small physical size, made it an element that could be used to cover any unexpected expenses [

1] (p. 17).

The quality seal offered by the “La Mancha Saffron” Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) (

Figure 5) guarantees the physical, chemical and organoleptic properties of this product which has a high colouring power (the Technical Quality Specification requires a minimum colouring power of 200 units), a strong, exotic aroma and a slightly bitter taste. It is easily distinguished because the red stigmas protrude clearly from the flower (

Figure 6) and because the length of the style is very short. These characteristics make it a magnificent flavouring capable of transmitting deep aromas, and it has been an irreplaceable spice in numerous Spanish dishes, especially in La Mancha cuisine, from the Middle Ages to the present day. Saffron from the latest harvest is always used, as it loses its quality over time, and it is only presented to consumers as flexible and strong threads, with bright red stigmas, it is never sold as a powder. Its slow toasting gives it its presence and its intense aroma, higher safranal and colouring power content [

22].

3.2. Saffron Cultivation: Cultural Landscape and Regional Identity in Castilla-La Mancha

In Europe, the European Landscape Convention signed in Florence in 2000 gives great prominence to landscapes, which are now considered to be the “part of the land, as perceived by local people or visitors, which evolves through time as a result of being acted upon by natural forces and human beings” and these landscapes are beginning to be valued as fundamental elements of the human environment, “an expression of the diversity of their common cultural and natural heritage and the basis of their identity” [

23] (p. 3) and, as such, they are attracting a great deal of interest. Analysis of landscapes is now based on the assumption that they are complex and fragile realities, containing “ecological, cultural and heritage values that cannot be reduced to land value”, which makes them “non-renewable” assets [

24]. Moreover, their status as resources for socio-economic development, an important aspect in disadvantaged rural areas, gives them a strategic nature.

Landscapes, and in this case those associated with agriculture, are changeable and identity-defining. Society survives in them through their use and transformation, through crops, livestock or forestry activities, and this allows the social groups to identify with a specific geographical area, with particular characteristics derived from their culture and know-how over the course of time. They are “cultural” landscapes insofar as they result “from the interaction over time between people and the natural environment, the expression of which is a landscape perceived and valued for its cultural qualities, the product of a process and the support for the identity of a community”, as defined by the National Plan for Cultural Landscapes in Spain [

25]. These are changing realities that arise from the processes that take place over time in a geographical area, and they are complex because they are made up of natural and cultural, material and immaterial, and tangible and intangible components. A definition that is similar to the one that has been used by UNESCO since the 1990s, but which, in Spain, includes any type of landscape of cultural interest, as opposed to the necessary “outstanding universal value” required for inclusion on the World Heritage List.

According to the aforementioned National Cultural Landscape Plan, the landscapes related to saffron cultivation would fall into the category defined by “Agricultural, livestock and forestry activities, independently or associated (historical agro-sylvo-pastoral systems), marine, fluvial and hunting activities”. A grouping with numerous examples in Spain where landscapes are closely related to agricultural production systems, their heritage values and the artisanal activities associated with them. This allows us not only to understand the complex variables involved but also to broaden the basis on which to establish development strategies to include activities such as tourism. They represent “a cultural heritage, the product of the economic exploitation of the ecological potential carried out by the different agrarian societies and human groups that throughout history have occupied, exploited and organised the countryside” [

26] (p. 7). Their cultural interest is not so much linked to the beauty of the “end result” as to the intrinsic value they possess from a cultural point of view [

16]. In fact, in the culture of saffron cultivation, the tasks “are varied (weeding, combating field mice, tilling the soil, harrowing, etc.), but among all of these tasks, because of the demand for labour that it requires and also because it is concentrated into a few days of work, harvesting is the most important, including the collection of the flowers in the field, removing the stigmas at home, and the drying of the removed stigmas” [

2] (p. 204).

In the case of saffron in the region of Castilla-La Mancha, it is clear that this crop is linked to the region with different extra-economic meanings that give it social and cultural values that are not always recognised, in which the human presence is fundamental. From the first records of the crop in this region, several characteristics can be seen that are still present today and which we have already mentioned: small-scale plots, the high market value of the product, and a significant social value with considerable involvement by women. However, its uniqueness is also related to local dynamics, since, at the same time as large areas of cultivation were established, first in cereals and, from the 19th century onwards, also in vineyards, there was also a system of smallholdings with small plots of secondary products such as pasture, melons, vegetables, potatoes, hemp and also saffron. The transfer of these small plots of land, usually between one and two hectares, by the large landowners was part of the social and economic balance of the areas [

27]. Furthermore, saffron crocuses were frequently used as a dowry for newlyweds, as a basis on which to start their new life [

28], as well as giving saffron stigmas to brides and grooms as a symbol of the wish for prosperity.

The recognition of heritage resources associated with crops, such as in this case saffron, is linked to the theoretical reformulation of some concepts such as heritage, which is broadened from simply relating to a “monument” to incorporate elements and resources inherited from the past in all forms and aspects (practices, knowledge, landscapes, etc.), which are now interpreted from a holistic point of view and as cultural expressions. For its part, the land itself has come to be considered as a “non-renewable, essential and limited asset” [

12,

20] to be passed on, in the best possible condition, to future generations by ensuring the values of “each of its parts”, i.e., the landscape.

As with other agrarian cultural landscapes, those associated with saffron cultivation are the result of the transformation over time of natural landscapes by a social group; in this case rooted in an area within the Mediterranean agricultural tradition, where the culture is the agent, the natural area is the medium, and the landscape is the result. A humanised landscape in which the reassessment of culture is related to everything that is linked to heritage [

29] (p. 138), where this crop “also contributes to defining the character of the people who raise it, who take advantage of the resources it offers, and who experience them, in short” [

30] (p. 8), as more than its value as an agricultural product. People who perceive these resources in a unique way and who take an active part in understanding the set of customs and traditions that make up the tangible and intangible heritage, i.e., their legacy for the next generation.

With regard to the wealth of heritage resources linked to saffron cultivation in Castilla-La Mancha, we will base our approach, as mentioned in the methodological section, on applying the resource classification offered by the Baeza Charter on Agricultural Heritage [

31]. This is a document signed in 2012 that was created in Spain in response to the undervaluing of agricultural assets as cultural and heritage elements in a current context in which agriculture is only valued from a purely productive perspective. The Charter states that agricultural heritage “is made up of all the natural and cultural, tangible and intangible assets, generated and used by agricultural activity throughout history” [

27]. Consequently, agricultural heritage is appraised as representing values and meanings arising from agricultural activities, highlighting its contribution to food; its harmonious relationship with the land, manifested in a sustainable and dynamic use of natural resources; its essential identity as part of the relationship between culture and nature; and its essential contribution to biological and cultural diversity [

16]. On this basis, we can distinguish different groups of heritage resources related to this crop, such as Moveable Assets that include the utensils, implements or tools used for tillage and cultivation, in general, these are modest tools (hoes, bulrush baskets, wooden containers, textile and embroidered accessories to protect the stamen before and after toasting, small cookers for toasting, etc.) that form part of the rural culture itself and which have been progressively replaced by more modern versions. Today, they can be seen in the Saffron and Ethnographic Museum in the municipality of Madridejos (

Figure 7).

Singular Structural Assets include constructed elements which, in this case, are almost non-existent, given the small surface area of these plots of land. On the other hand, Group or Linear Structural Assets mainly consist of landscapes and agricultural fields, as well as rural settlements. We would highlight small towns where ruralisation is still present in Castilla-La Mancha such as Villafranca de los Caballeros, Madridejos and Consuegra in the province of Toledo, La Solana in the province of Ciudad Real, Motilla del Palancar in the province of Cuenca and Pétrola and Lezuza in the province of Albacete.

For their part, Intangible Assets, which we will examine in more detail below, are diverse and probably represent the most attractive assets within the legacy related to this crop. Starting with linguistic issues, there is an important collection of specific terms (bulbs, corm, threads, etc.), in fact, as an activity linked to society, saffron has developed its own vocabulary, which is expressed through more than 100 words and expressions that make up its lexicon in the region. Saffron and the people involved in its harvesting and processing play a leading role in the folklore of La Mancha, particularly in the ‘jotas manchegas’ (popular dances), as well as in the varied presence of saffron in songs and proverbs. Also important is the knowledge, the know-how, surrounding the uniqueness of this crop, especially in relation to peeling and toasting, together with the cuisine, where its function as a condiment is widely recognised, as well as, in general, the culinary culture associated with its use in dishes such as ‘gazpacho manchego’ stews, ‘gachas’ (savoury porridge) or ‘arroz con leche’ (rice pudding). Finally, the Natural and Genetic Heritage refers to local varieties and crop specificities with specific organoleptic properties that are different from those of other saffron fields.

3.3. Intangible Heritage and Social Practices in the Saffron Landscapes in Castilla-La Mancha

Today, oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge and practices relating to nature and the universe, and knowledge and skills linked to traditional craftsmanship are globally recognised as part of what is known as “intangible heritage”. UNESCO includes them under the category

intangible cultural heritage or “living heritage”, i.e., practices, expressions, knowledge or techniques transmitted by communities from generation to generation [

32]. It relates to a heritage that serves to foster regional identity and that can be recreated by local communities reflecting their environment, their interaction with nature and their history.

Despite its fragility, this heritage contributes to maintaining cultural diversity in the face of the media standardisation imposed by globalisation, serving as a dialogue between cultures and promoting respect for other ways of life [

33]. Its importance lies in the wealth of knowledge and skills that are passed down from generation to generation, and whose social and economic value is of relevance to social groups, especially in relation to crops such as the one being analysed here. Among the main characteristics of this type of resource, UNESCO [

28] highlights the following, which can be perfectly associated with the agrarian cultural landscapes created by the cultivation of saffron in Castilla-La Mancha and which has already been applied to other crops such as vineyards [

16]:

- -

It constitutes a traditional, contemporary and living heritage as it continues to be present in the agricultural structure of the region, albeit subject to market pressures. It bears witness to traditions inherited from the past, among which the most important are the work of peeling and toasting, which are carried out collectively and generally by women (

Figure 8).

- -

It is inclusive, as the expressions of heritage are similar in all the municipalities that grow saffron, grouped together in the “La Mancha Saffron” Protected Designation of Origin. All of them produce an identification with the cultural cycles of sowing, harvesting and transformation that have been passed down from generation to generation, thus contributing to social and cultural cohesion by fostering regional identity and a sense of belonging.

- -

It is representative, especially on the basis of its cultural uniqueness, with techniques and customs that are handed down from generation to generation.

- -

Finally, its link to the community that grows, processes and enjoys it is fundamental, as its cultural and heritage value is related to the recognition of the local population in a “bottom-up” heritage process. No one can decide for them that a particular expression or use is part of their heritage and thus of their regional identity.

Among all the resources included in the intangible or immaterial heritage associated with the saffron landscapes in Castilla-La Mancha, we will focus on some festivals linked to social and ritual uses that are representative of the agrarian culture in relation to this crop. Generally, they have been built on habits and customs that reflect the work of social groups linked to this crop and its associated socially shared activities. They also reaffirm identity in relation to both public practices (harvesting, peeling, etc.) and private practices (cuisine). A set of resources that, according to UNESCO [

34], help to mark the changes of seasons, times of agricultural work, and stages of human life, and are intimately linked to the worldview, history and memory of the communities.

In the areas where saffron is cultivated in Europe, and specifically in Spain, there are numerous rituals and festivals that are normally held around the time of the harvesting and toasting of saffron, while their value is not recognised universally, they are established in the regions and/or states in which they are found, the case of Spain being certainly unique in the European context. Occasionally, these social practices, rituals and festivals are profoundly affected by the changes that the communities are undergoing in modern societies, as they depend to a large extent on the broad participation of those who practise them. In the case of saffron, as in the case of other crops harvested at this time of year, these festivals in a way mark the beginning of autumn.

The most significant manifestations of intangible heritage related to the festivals in the Castilla-La Mancha region (Spain) are songs, popular dances, works of literature, paintings, etc. The following are some of the most important ones: the Jornadas del Azafrán held for the last 15 years in Madridejos (Toledo); the Fiesta de la Rosa del Azafrán in Consuegra (Toledo), which has been held since 1963 and has been declared a Festival of Regional Tourist Interest, in connection with which the peeling competition and the Folklore Festival are a significant part; the Semana de la Zarzuela in La Solana (Ciudad Real), an annual event in the village where Romero y Fernández set the play “La Rosa del Azafrán”, with music by Jacinto Guerrero, which premiered in 1930 (in the past there was also a peeling competition); and in Albacete, the Festival de la Rosa del Azafrán in Santa Ana, which has been held for over 30 years, but with a more local character than the previous events. We will focus on the first two because of their national and international character, their extensive experience, together with the existence of a strategic plan that integrates elements from different spheres under saffron as an integrating concept.

3.4. Case Studies: Las Jornadas del Azafrán in Madridejos (Toledo)

These events have been organised since 2007 and have arisen from an annual local celebration, with the aim of promoting the celebration on a wider scale outside the region, with a more ambitious strategy. After a first few years of development and growth, the event is now in a consolidation phase. The objectives that the town has set itself with this highly social annual event are as follows:

- (a)

Promote saffron from an integral point of view as a symbol of tradition in Madridejos.

- (b)

Position the Saffron and Ethnographic Museum as a major tourist attraction.

- (c)

Promote other local tourist resources, such as the mills and cave houses (these are called “silos” in Spanish).

- (d)

Promote the cultivation and use of saffron among young people.

From the point of view of the built heritage, the main element of reference is the Saffron and Ethnographic Museum, whose inauguration in 2008 is the main cornerstone of this initiative (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). The museum is housed in a unique building, a Franciscan monastery that has been renovated and refurbished for a dual purpose: on the one hand, to house an extensive ethnographic collection, with pieces and elements related to the culture of La Mancha; and on the other, to dedicate a large exhibition area to saffron culture, including its cultivation process, its importance in the local context and its economic significance and social impact in La Mancha.

Other related structural resources are cave houses and ancient dwellings carved out of limestone rock that served as humble dwellings in the past. The vast majority of them have now disappeared or are privately owned by families in the town. Two of them (the Silo del Tío Zoquete and the Silo de Tío Colorao) have remained as examples of this unusual structure and they are also part of the elements that form the backbone of the Jornadas del Azafrán.

Based on the museum as a tangible asset, a festival has been developing whose main characteristic is its heterogeneity, as it integrates cultural, musical, culinary, recreational, educational, academic and tourist activities. Therefore, under the umbrella of saffron, multiple events are brought together, which, as a consequence, have different target audiences. The local public is the most important element, both in terms of the target audience and in terms of participation, with a special focus on children, who will learn more about the historical importance of saffron through visits and educational and recreational activities. Visitors, generally from the region and neighbouring regions, along with international visitors, are the target group for culinary and leisure initiatives. Increasingly, the appeal of the event as a tourist attraction motivates people who may be attracted by more specialised culinary and academic activities, in addition to the range of leisure packages offered outside the region. The week-long event features guided tours of the fields and other heritage buildings, such as the cave houses and mills.

We do not have official participation figures, so we cannot have a quantified record of how the event has developed. However, according to information provided by the museum’s management, participation in registered activities (guided tours, tastings, culinary events, etc.) is booked up well in advance, an example of the interest aroused by this resource. The management and promotion of the event are based on local public and private participation led by Madridejos Town Council and including local agents, cultural associations, producers and local packaging companies. Social participation is mainly coordinated through the “El Carpío” Cultural Association, which aims to maintain local culture through different collaborative initiatives, such as its involvement in maintaining the unique elements of the structural heritage, both the aforementioned museum and the local cave houses that are open and can be visited. Behind this management core is the institutional and financial support of the regional administration and the cooperation of various businesses in the town, especially restaurateurs and leisure establishments.

The general strategy is based on creating a competitive event and promoting it beyond the local area, centred on the local identity, with saffron as the main theme and not only in its agricultural dimension. Its progressive consolidation reinforces the local identity around the historical significance of saffron. The greatest threat identified in the interviews is the same as the one that applies to the saffron sector itself: the lack of replacement by the next generation of producers, which is gradually reducing the cultivation base and local production. This problem contrasts with the growth of the event, which is increasing in popularity and demand every year, a contradiction that calls for greater institutional attention.

3.5. Case Studies: Fiesta de la Rosa del Azafrán in Consuegra (Toledo)

The Fiesta de la Rosa del Azafrán in Consuegra has been held since 1963 and has always had an aspect related to the world of agriculture and livestock farming in La Mancha. It is a well-established and well-renowned event, with a programme of activities that is very similar from one year to the next. Nowadays, it is a week of celebrations with entertainment events that attract people from outside the area. It presents two fundamental objectives:

- (a)

Maintain the awareness of people from outside the area and act as a focus for tourism.

- (b)

Group all the local activities under the same strategy.

It maintains an agricultural and rural profile, with a trade fair showcasing local agricultural and livestock products, including producers, together with the exhibition and sale of agricultural machinery, and the exhibition space is shared with stalls for leisure activities and culinary demonstrations. Various socio-ethnographic events linked to the world of agriculture in general and saffron, in particular, are held over the course of a week: competitions in flower harvesting, tractor driving skills, traditional wheat milling, etc. Folklore is closely linked to the festive programme, with various traditional and modern music activities that culminate in the National Saffron Rose Folk Festival, which brings together folk music and dance groups from all over the Iberian Peninsula. In short, almost all the activities revolve around saffron, both of a local nature (sports competitions, contests, etc.) and the more widely publicised tourist-oriented events.

This festival is a regional, national and world landmark, due to its longevity and established nature, and it has been declared a Festival of Regional Tourist Interest (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). The programming and management are mainly supported by the municipal services, involving various areas, especially the Department of Tourism, and it has institutional support from other high-level administrations. There is significant local participation, structured through local associations and companies that support the performance of the activities, where the presence of local assets is especially evident in the parallel events, less related to the nature of the festival itself, such as sports, competitions or demonstrations far removed from the world of agriculture. These activities are interwoven within the Rosa del Azafrán theme in order to integrate the week’s leisure and cultural events into the week as a whole.

There are no official data on participation, although large crowds are evident throughout the week and especially during the weekend. The presence of tourists and visitors is evident, along with the local festive atmosphere. As a result, this celebration is highly competitive and deeply rooted as a local landmark and as the main economic and cultural asset recognised outside the local area. It reinforces Consuegra’s local identity and raises its visibility outside the local area based on the values and meanings shared by the local population.

Saffron is the main focus of the event as a whole. Harvesting the flowers and peeling and toasting them form the starting point around which the rest of the activities are organised. However, its actual presence is diluted by the abundance of other events. This loss of prominence is the result of the problem of generational replacement and crop continuity, a real threat to the sustainability of the crop in future generations. Nevertheless, saffron continues to be a motivating, distinctive and catalytic element of sufficient importance that it can be used to create unique events that take place at the same time as those in Madridejos, which are differentiated in terms of their profile and implementation. Of particular relevance is the fact that the two towns are barely 8 km apart and that both events coincide on the same dates, a situation that influences the interpretation and complementarity of these events.

As saffron is a crop so dependent on its annual cycle, especially for the harvest, which is concentrated in just 10 days in autumn, the time frame for scheduling a festival around it is quite limited, which explains the coincidence in the dates the festivals take place. In fact, several nearby towns also have festivals related to saffron on the same dates, but without the character and profile of the two we are describing here. The festival in Consuegra has an unquestionably long-standing tradition, while Madridejos launched its festival later and with a strategy that has sought, from the beginning, to differentiate its character from that of the neighbouring festival. This has allowed both to create their own spaces, which to some extent complement each other, although there has thus far been no initiative for synergy or integration between the two festivals. However, in both cases, the main problem stems from the worrying trend in cultivation as such, which is suffering from a slow but progressive decline and a lack of young people to take over.