Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Heritage about Medicinal Plants in a European Transboundary Area (La Raya: Extremadura, Spain—Alentejo, Portugal): Transdisciplinary Research for Curriculum Design in Health Sciences

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- How have rural communities arrived at the knowledge they have about the medicinal plants in their environment?

- How are medicinal plants perceived, classified, used, and administered by these communities?

- Do they establish traditional healing strategies with the plants in their environment?

- What traditional knowledge would help strengthen curriculum designs in university health sciences studies?

2.1. Research Context and Participants

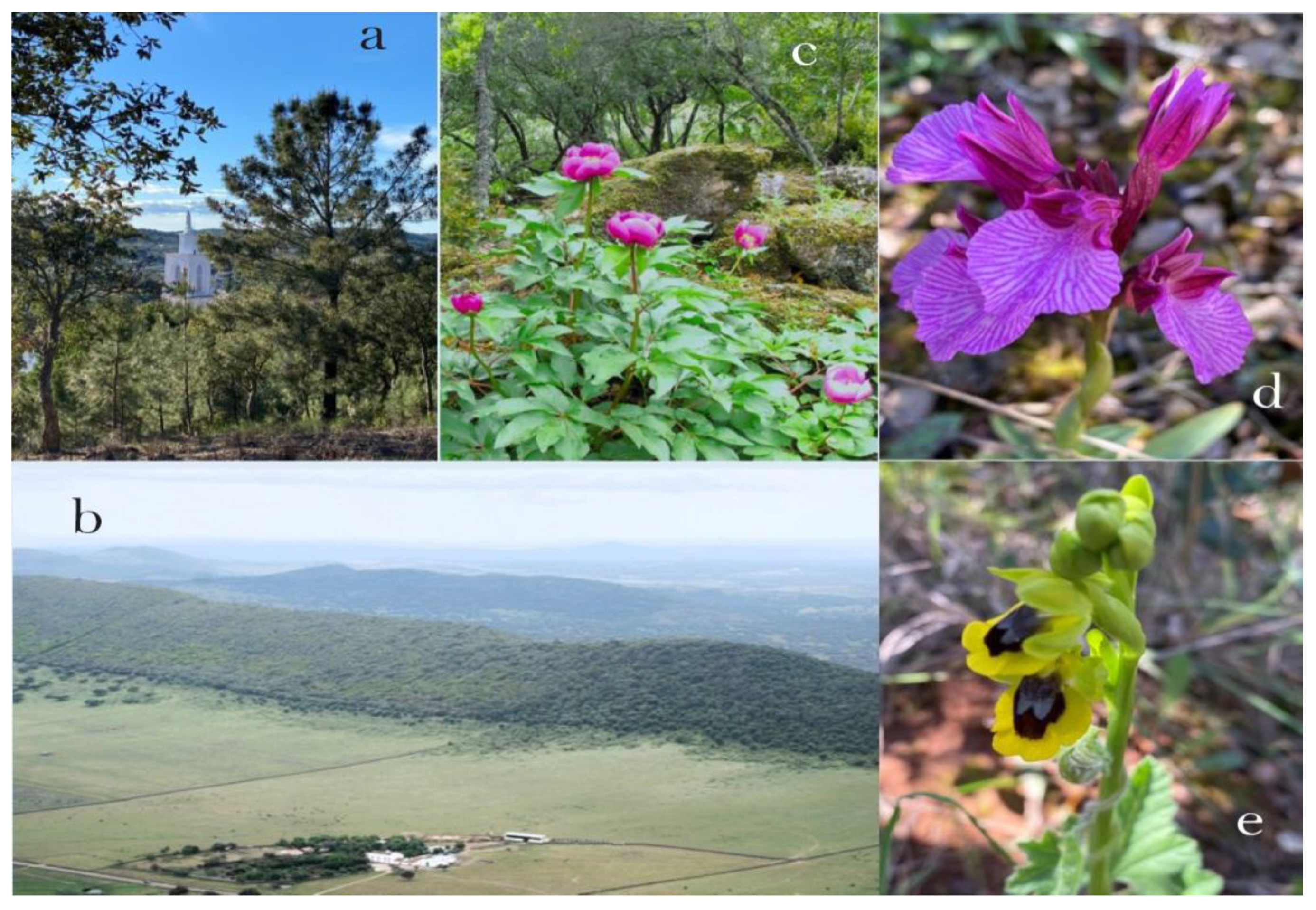

2.1.1. La Raya: Alor and São Mamede Mountain Ranges and Cross-Border Localities

2.1.2. The Higher School of Health (Portalegre, Portugal)

2.1.3. The Informants

3. Results: Data Collection and Analysis

3.1. Worldview of Informants in La Raya

3.1.1. Individual Interviews

3.1.2. Group Interviews

3.1.3. Student Responses

BLOC 1—Students’ Behavior When Faced with a Health Problem

BLOC 2—Consumption, Knowledge, and Cultural Transmission of Medicinal Plants

4. Discussion and Intervention Proposal

4.1. The Development of Competences and Professional Identity Working Ethnomedical Heritage

From what I have been able to see, from my experience of life leading me to death, that it only takes one behavioral or gestural break in the continuity of care for the whole quality of a team’s work to be destroyed. All it takes is one “black sheep” for the fragility of what takes life to be confronted with the most abrupt despair. The best professional technical skills are nullified by the breakdown of interpersonal respect and deprives the cared-for person of a voice to defend him/herself, because the realities of retaliation and persecution in care then appear. To all, I ask you to focus on life forces, to mobilize your vital resources in respect of the individual and humanity, to promote care and to promote life(taken from Pineda 2010) [79].

4.2. Tables of Contextual Cognition: The Student as a Researcher of Cultural and Intangible Heritage of Ethnomedical Character

4.2.1. Fieldwork on Local Knowledge about Medicinal Plants

4.2.2. Construction of Contextual Cognition Tables (CCTs)

4.2.3. Group Discussion of Results

4.2.4. Dialogue and Intercultural Sensitivity

5. Final Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| (A) DADOS SOCIOCULTURAIS E FORMAÇÃO DOS INFORMADORES |

| 1. Sexo: |

| (1 = Mulher 2 = Homem) |

| 2. Ano de nascimento: |

| 3. Origem: |

| 3.1. Em que país foi criado? |

| 1 = Espanha |

| 2 = Portugal |

| 3 = Outro país. Qual? |

| 3.2. Em que tipo de população foi criado? |

| 1 = Meio urbano |

| 2 = Meio rural |

| 3.3.1. Em relação ao progenitor 1 (mãe biológica), em que país cresceu? |

| 1 = Espanha |

| 2 = Portugal |

| 3 = Outro país. Qual? |

| 3.3.2. Em que tipo de população o progenitor 1 (mãe biológica) foi criado? |

| 1 = Meio urbano |

| 2 = Meio rural |

| 3.3.3. Ano de nascimento do progenitor 1 (mãe biológica): |

| 3.4.1. Em relação ao progenitor 2 (pai biológico ou outro parente em linha reta ascendente): em que país cresceu? |

| 1 = Espanha |

| 2 = Portugal |

| 3 = Outro país. Qual? |

| 3.4.2. Em que tipo de população o progenitor 2 foi criado (pai biológico ou outro parente em linha reta ascendente)? |

| 1 = Meio urbano |

| 2 = Meio rural |

| 3.4.3. Ano de nascimento do progenitor 2 (pai biológico ou outro parente em linha reta ascendente): |

| 4. Educação: |

| 4.1. O que é que está a estudar? |

| 1 = Enfermagem |

| 2 = Higiene Oral |

| 3 = Medicina |

| 4 = Fisioterapia |

| 5 = Outros (favor indicar) |

| 4.2. Em que ano do curso está? |

| (1º, 2º, 3º, 4º, 5º) |

| 4.3. Já realizou algum curso superior, cursos de formação profissional ou outros estudos anteriormente? |

| 1 = Sim 0 = Não |

| Se sim, quais? |

| Indique o local, onde os cursou? |

| 5. Os estudos são compatíveis com o trabalho? |

| 0 = Não 1 = Sim |

| (B) QUESTÕES PARA CONHECER O COMPORTAMENTO FRENTE A UM PROBLEMA DE SAÚDE E OS MOTIVOS QUE JUSTIFICAM O USO DE PLANTAS MEDICINAIS (PM) |

| 6. Perante um problema de saúde, com qual ou quais destas afirmações concorda mais? |

| 1 = Espero que passe sem tomar nada, e se não vou ao médico |

| 2 = Vou às urgências ou a uma consulta médica imediatamente |

| 3 = Quando se trata de uma doença ligeira eu costumo recorrer a remédios caseiros, incluindo plantas medicinais |

| 4 = Não é bom abusar dos medicamentos porque podemos criar resistências e por isso costumo consumir remédios alternativos |

| 5 = Uso medicamentos ou plantas medicinais de acordo com o tipo de doença |

| 7. Com qual ou quais destas afirmações está mais de acordo? |

| 1 = Eu acho que não é uma boa prática consumir PM (plantas medicinais) para o tratamento de doenças |

| 2 = Curar-se com PM ou com medicamentos são dois métodos que podem funcionar de forma igual |

| 3 = Curar-se com PM é mais saudável, não possuem efeitos secundários significativos e são eficazes para problemas menores |

| 4 = O consumo de PM não envolve riscos importantes, mas a crença na sua eficácia curativa é um mito |

| 5 = O consumo de PM não implica riscos importantes, mas acreditar que as plantas podem resolver problemas de saúde é uma atitude pseudocientífica |

| 8. No posto de saúde, o médico: |

| 1 = Receita-me sempre medicamentos |

| 2 = Receita-me tanto medicamentos como PM |

| 3 = Já me recomendou PM |

| 9. Se utiliza terapias alternativas ou complementares, esconde do médico que as usa? |

| 0 = Não. Porquê? |

| 1 = Sim. Porquê? |

| 2 = Depende. Quando? |

| 10. Ao fazer o historial, o médico pergunta-lhe: |

| 1 = Sobre o consumo de terapias alternativas ou complementares |

| 2 = Se consome plantas medicinais colhidas no campo |

| 3 = Se consome plantas medicinais, e onde as compro |

| 4 = Se consome plantas medicinais, mas não de onde procedem |

| 5 = Não me faz perguntas sobre terapias alternativas ou complementares |

| 11. Costuma usar PM ou os seus derivados? |

| 0 = Não |

| 1 = Sim |

| 12. Entre os motivos pelos quais NÃO usa plantas medicinais estão: |

| 1 = Falta de conhecimento sobre elas |

| 2 = Acho que curar com PM é mais saudável, e algumas curam pequenos problemas de saúde, mas não tenho tempo para preparar |

| 3 = Acho que usar PM é mais saudável e podem até curar problemas de saúde complicados, mas não tenho tempo para preparar |

| 4 = O efeito não é tão rápido como o dos medicamentos |

| 5 = São menos eficazes do que os medicamentos |

| 6 = São mais caras do que os medicamentos |

| 7 = Acho que não são eficazes, são apenas um placebo |

| 8 = Acho que podem ser eficazes para alguns problemas de saúde, mas a sua utilização envolve riscos para a saúde e não as uso |

| 9 = Outras razões (por favor indicar) |

| 13. Com que frequência toma plantas medicinais (PM) ou outros remédios caseiros (RC)? |

| 1 = Às vezes (uso pouco, costumo usar remédios) |

| 2 = Frequentemente (uso muito, mas não por rotina) |

| 3 = Geralmente (para prevenir e sempre que tenho dores) |

| 4 = Nunca consumo plantas medicinais para fins terapêuticos |

| 14. Além de fins terapêuticos, toma PM e / ou RC por outros motivos? |

| 0 = Bebidas sociais (por exemplo, para tomar um chá, chá de hortelã, etc. com os amigos) |

| 1 = Para prevenir doenças |

| Outros: Não |

| 15. As plantas medicinais beneficiam a saúde humana porque: |

| 1 = Têm poderes, mesmo que não estejam comprovados |

| 2 = Têm princípios ativos com atividade farmacológica |

| 3 = Outras causas, quais? |

| (C) PERGUNTAS PARA CONHECER A ORIGEM DE COMPORTAMENTOS POSITIVOS FRENTE ÀS PLANTAS MEDICINAIS |

| 16. Quem ou o que influenciou seu conhecimento sobre PM e RC? |

| 0 = Mãe 1 = Pai 2 = Avó 3 = Avô 4 = Outros parentes 5 = Professores 6 = Amigos 7 = Ninguém 8 = Internet 9 = Televisão 10 = Livros 11 = Acampamentos 12 = Cursos 13 = Outras atividades que lhe fizeram sair ao campo 14 = Nada |

| 17. Pertence a alguma associação que o influenciou neste assunto? |

| 0 = Sim 1 = Não |

| 18. Pense na maneira como normalmente se relaciona com o meio ambiente e como usa os recursos da natureza. Com qual das seguintes tendências se identifica? |

| 1 = Tradicional: integrado nos costumes rurais |

| 2 = Naturista: tendência em que são usados terapias e estilos de vida alternativos |

| 3 = Ecologista: pessoa que se preocupa ativamente com o meio ambiente |

| 4 = Pessoa que tem interesse no meio ambiente |

| 5 = Outro (por favor indicar): |

| 6 = Nenhuma |

| (D) PERGUNTAS SOBRE A CONFIANÇA, QUALIDADE E SEGURANÇA NO USO DE PLANTAS MEDICINAIS |

| 19. Quais as fontes que lhe dão mais confiança ao usar PM? |

| 1 = Parentes ou conhecidos (remédios transmitidos por conhecimentos tradicionais) |

| 2 = Televisão, rádio, Internet… (remédios disseminados pelos meios de comunicação, meios de comunicação) |

| 3 = Somente profissionais de saúde formados em medicina |

| 4 = Todos os tipos de profissionais de saúde ou qualificados cientificamente |

| 5 = Profissionais paramédicos (fitoterapeutas, quiropráticos, etc.) |

| 6 = Outros (indique) |

| 7 = Ninguém ou nada |

| 20. Numa escala de um a 10, qual o grau de qualidade e segurança que acha que têm as plantas medicinais compradas nas farmácias? |

| 21. Numa escala de um a 10, qual o grau de qualidade e segurança que acha que têm as plantas medicinais compradas em parafarmácias e fitoterapeutas? |

| 22. Numa escala de um a 10, qual o grau de qualidade e segurança que acha que têm as plantas medicinais compradas em feiras de colheita silvestre? |

| (E) PERGUNTAS PARA SABER QUAIS MEDICAMENTOS USAM, QUEM RECOMENDA, COMO OBTER, QUEM RECOMENDA E A SUA UTILIDADE |

| 23. Conhece pessoas que colhem PM para consumo? |

| 0 = Não, 1 = Sim |

| Qual é a sua relação com eles? |

| 1 = Mãe, 2 = Pai, 3 = Outros parentes (especifique o membro da família), 5 = Outros |

| 24. Como se abastece com PM? |

| 1 = Eu não os consumos e, portanto não os compro |

| 2 = Farmácias |

| 3 = Supermercados |

| 4 = Ervanárias, herbalistas |

| 5 = Mercados ou bancas de rua |

| 6 = Recolho-as no campo |

| 7 = Recolho-as no pomar ou jardim |

| 25. Das plantas que tomou, algumas agem para prevenir, curar ou fortalecer o corpo em caso de: |

| 1 = Infecções, infestações |

| 2 = Inflamações |

| 3 = Dores |

| 4 = Distúrbios nutricionais |

| 5 = Sistema respiratório |

| 6 = Sistema digestivo |

| 7 = Sistema circulatório |

| 8 = Pele, úlceras, feridas, tecidos subcutâneos |

| 9 = Sistema músculoesquelético, traumatismos |

| 10 = Sistema genito-urinário |

| 11 = Sistema sensorial |

| 12 = Sistema nervoso, doenças mentais |

| 13 = Gravidez, parto, doenças puerperais |

| 14 = Sistema endócrino, doenças metabólicas |

| 15 = Sistema imunitário |

| 16 = Doenças não específicas |

| 26. As partes das plantas que já tomou para prevenir, curar ou fortalecer o corpo são: |

| 1 = Folha |

| 2 = Caule |

| 3 = Raiz |

| 4 = Flores e estruturas florais |

| 5 = Parte aérea |

| 6 = Fruto |

| 7 = Semente |

| 8 = Outros |

| 27. Como prepara ou preparou plantas medicinais? |

| 1 = Infusão |

| 2 = Cataplasma |

| 3 = Antídoto |

| 4 = Supositórios |

| 5 = Tablete |

| 6 = Irrigação |

| 7 = Gotas |

| 8 = Inalador |

| 9 = Poção |

| 10 = Clister (enema) |

| 11 = Pomada |

| 12 = Colírio |

| 13 = Xarope |

| 14 = Gargarejo |

| 15 = Banho |

| 16 = Linimento |

| 17 = Emplastro |

| 18 = Ingestão oral simples |

| 19 = Lavagem |

| 20 = Outro |

| 28. Com que frequência usa as plantas medicinais? |

| 1= Eu não as uso |

| 2= Muito raramente |

| 3= Raramente |

| 4= Ocasionalmente |

| 5= Frequentemente |

| 6= Muito frequentemente |

| (F) RECONHECIMENTO DE PLANTAS MEDICINAIS ATRAVÉS DE IMAGENS |

| Serão mostradas as espécies de maior importância cultural (e.g., Hypericum perforatum) |

| 29. Olhe esta imagem, já viu esta planta alguma vez? |

| 0 = Não 1 = Sim |

| 30. Sabe o seu nome? |

| 0 = Não |

| 1 = Sim |

| 2 = Como se chama? |

| 31. Conhece o seu uso medicinal? |

| 0 = Não |

| 1 = Sim |

| 2 = Para que é usada? |

| (G) QUESTIONÁRIO ABERTO |

| 32. Quais são as plantas medicinais ou remédios caseiros que usa para tratar ou prevenir doenças? Para que servem cada um deles? |

| 33. Descreva brevemente as plantas que conhece e onde podem ser encontradas |

| 34. Como se preparam as plantas medicinais que conhece? (por exemplo: infusão, sumo, cozimento, etc.) |

| 35. De que forma aplica essas plantas? (por exemplo: cataplasma, banhos, infusão de bebida, vapor, etc.) |

| 36. Como é que conheceu estas plantas? De onde era a pessoa que lhe deu a conhecê-las? Que relação tinha consigo (pai, mãe, avós, amigos, vizinhos, companheiros, etc.)? Já teve conversas sobre o uso tradicional das plantas medicinais que conhece? |

| 37. Gostaria de participar, como investigador júnior, num projeto sobre recuperação de conhecimentos tradicionais? Em caso afirmativo, faz favor contacte (e-mail: joseramon.vallejo@uca.es) |

Appendix B

| SCIENTIFIC NAME | VERNACULAR NAMES | |

|---|---|---|

| EXTREMADURA | ALENTEJO | |

| Aegilops geniculata Roth | Trigo de perdiz | Trigo de perdiz |

| Asparagus acutifolius L. | Ferreña, Espárrago ferreño, Espárrago negro | Espargo menor do monte |

| Asparagus albus L. | Esparraguera blanca, Espárrago blanco | Espargo branco, bravo |

| Asteriscus aquaticus (L.) Less. | Yerbajo malo | - |

| Avena barbata Pott ex Link | Palanco, Vena loca | Balanco bravo |

| Barlia robertiana (Loisel.) Greuter | Orquídea grande | - |

| Bryonia dioica Jacq. | Parral bravo | - |

| Carlina gummifera L. | Cardo la liga, Cardoliga, Liga | Cardo do visco |

| Carthamus lanatus L. | Cártamo, cáncamo | - |

| Centaurea calcitrapa L. | Cardo curalotó | - |

| Centaurea melitensis L. | Cardo sudalamano | - |

| Centaurea ornata Willd. | Cardazol, Cardazoli, cardanzol, Cardo la olla | Cardazol, Lavapé |

| Centaurium erythraea Rafn. | Jiel de la tierra | Fel da-terra |

| Cistus albidus L. | Ogarso blanco | Roselha grande |

| Cistus crispus L. | Ogarso | - |

| Cistus ladanifer L. | Ogarso negro | Roselha, Xara |

| Crataegus monogyna Jacq. | Tila, Galapero | - |

| Cynara cardunculus L. | Cardo | Cardo-do-coalho |

| Cynara tournefortii Boiss. | Alcachofa, Alcachofa de las buenas | Alcachofra rastreira |

| Daphne gnidium L. | Travisca, travista | Trovisco, Trovisqueira |

| Daucus carota L. | Sindiente | Cenoura |

| Dittrichia viscosa (L.) Greuter | Pegajosa | - |

| Helichrysum stoechas (L.) Moench | Manzanilla brava, Manzanilla | Macela-real |

| Hypericum perforatum L. | Yerba de San Juan, Pericón, Árnica | Erva-de-São-João, Hipericão |

| Lavandula stoechas L. | Tomillo borriquero | Rosmaninho |

| Lavatera cretica L. | Malva | Malva bastarda |

| Lonicera implexa Aiton | Madreselva | Madresilva |

| Mentha aquatica L. | Menta | - |

| Mentha pulegium L. | Poleo | Poejo |

| Nasturtium officinale W.T. Aiton | Agrión, Berro de agua | Agrião |

| Olea europaea var. sylvestris Brot. | Azahuche, Aceuche | - |

| Origanum vulgare subsp. virens (Hoffmanns. & Link) Ietswaart | Orégano | Orégão |

| Oxalis pes-caprae L. | Agrio, canario | Erva-canária |

| Papaver rhoeas L. | Amapola mansa | Papoila |

| Pistacia lentiscus L. | Lentisco, Aruera, Aruera blanda | Aroeira |

| Pistacia terebinthus L. | Cuernicabra duro, Aruera dura | - |

| Quercus coccifera L. | Coscoja | - |

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Romero bravo | Alecrim |

| Ruta graveolens L. | Ruda basta | - |

| Ruta montana L. | Ruda, Ruda fina | Arrudão |

| Salvia officinalis L. | Salva | Salva |

| Sambucus nigra L. | Sauco | Sabugueiro |

| Scolymus hispanicus L. | Tagarnina | - |

| Senecio vulgaris L. | Tagna fuerte | Tasna |

| Thymus mastichina L. | Tomillo | Erva-ursa |

| Trifolium angustifolium L. | Trebol, Traballem | Trevo, Fofa |

| Trifolium campestre Schreb. in Sturm | Trebol, Traballem | - |

| Triticum turgidum L. | Sietespiguín | Trigo-duro |

| Verbascum sinuatum L. | Gordolobo | Verbasco |

Appendix C

| SERIOUS DRUG INTERACTIONS |

|---|

| (see Natural Medicines Database) [114,115,123] |

| • Alprazolam (Xanax, Trankimazin) |

| • Birth control pills (contraceptive drugs) |

| • Cyclosporine (Neoral, Sandimmune) |

| • Digoxin (Lanoxin) |

| • Docetaxel (Taxotere) |

| • Imatinib (Gleevec) |

| • Irinotecan (Camptosar) |

| • Ketamine (Ketalar) |

| • Medications changed by the liver (cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) substrates) |

| • Medications changed by the liver (cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) substrates) |

| • Medications for HIV/AIDS (nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)) |

| • Medications for HIV/AIDS (protease inhibitors) |

| • Medications for HIV/AIDS (nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)) |

| • Medications for HIV/AIDS (nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)) |

| • Omeprazole (Prilosec) • Oxycodone (Oxycontin) |

| • Phenobarbital (Luminal) |

| • Phenprocoumon (Marcoumar, others) |

| • Phenytoin (Dilantin) |

| • Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) |

| • Tacrolimus (Prograf) |

| • Warfarin (Coumadin) |

| RISKS |

| (see Natural Medicines Database) [114,115,123] |

| It is complex to verify the effectiveness and safety of products based on this species due to differences in content related to the time of year, the climate, and the location of the crop. The CANMAT Taskforce recommends standardized formulations (0.2–0.3% hypericin and/or 5–6% hyperforin). |

| • Pregnancy: |

| This medicinal plant may not be safe when taken by mouth. It may cause birth defects in babies. •Breastfeeding: It may not be safe when taken by mouth. Babies may experience colic, drowsiness, and irritability. |

| • Children: |

| It is possibly safe when taken orally for up to 8 weeks in children aged 6 to 17 years. •Alzheimer’s disease: It may worsen dementia. •Bipolar disorder: It may cause mania. It may also speed up the cycle between depression and mania. |

| • Schizophrenia: |

| St. John’s wort may cause psychosis. |

| • Surgery: |

| St. John’s wort may affect serotonin levels in the brain, which could interfere with surgical procedures. Also, in people who have used it, anesthesia can cause serious heart complications during surgery. |

References

- Wardle, J.L.; Adams, J. Indirect and non-health risks associated with complementary and alternative medicine use: An integrative review. EuJIM 2014, 6, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Arye, E.; Samuels, N.; Goldstein, L.H.; Mutafoglu, K.; Omran, S.; Schiff, E.; Charalambous, H.; Dweikat, T.; Ghrayeb, I.; Bar-Sela, G.; et al. Potential risks associated with traditional herbal medicine use in cancer care: A study of Middle Eastern oncology health care professionals. Cancer 2016, 122, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Wang, B.; Jiang, J.; Fitzgerald, M.; Huang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J.; Yang, C.; et al. Heavy metal contaminations in herbal medicines: Determination, comprehensive risk assessments, and solutions. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 595335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verde, A.; Rivera, D.; Vallejo, J.R.; Fajardo, J.; Obón, C.; Valdés, A. Ethnopharmacology in Elementary, Primary and Secondary Education: Current Perspectives and Future Prospects. In Ethnopharmacology; Heinrich, M., Jäger, A.K., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Olivé Morett, L.; Argueta Villamar, A.; Puchet Anyul, M. Interdisciplina y transdisciplina frente a los conocimientos tradicionales. Rev. Iberoam. Cienc. Tecnol. Soc. 2018, 13, 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Robles-Piñeros, J.; Ludwig, D.; Baptista, G.C.S.; Molina-Andrade, A. Intercultural science education as a trading zone between traditional and academic knowledge. Stud. Hist. Philos. Biol. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 84, 101337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hani, C.; Poliseli, L.; Ludwig, D. Beyond the divide between indigenous and academic knowledge. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. 2022, 91, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, J.A.; Bernardos, S.; Amich, F. Plant Conservation vs. Folk Traditions: The Case of Ophrys scolopax Cav. (Orchidaceae) in Central Western Spain. Biology 2022, 11, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sneader, W. Drug Discovery: A History; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, R.; Davidson, P. Improving Access to Care in America. In dividual and Contextual Indicators. In Changing the U.S. Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management; Kominski, G.F., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, M.J.; Albarracín, G.; Caminal, J.; Rodríguez, N. Grupo de Investigación en MCA. Práctica y productos terapéuticos en medicinas complementarias y alternativas, ¿mercado regulado o mercado libre? Aten. Primaria 2008, 40, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.E.; Gage, A.D.; Arsenault, C.; Jordan, K.; Leslie, H.H.; Roder-DeWan, S.; Adeyi, O.; Barker, P.; Daelmans, B.; Doubova, S.V.; et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1196–e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isles, M. Patient safety issues associated with the use of compounded medicines as alternatives to approved pharmaceutical products in Europe and how best practice can improve outcomes. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 2020, 31, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, L.; Perkiss, S.; Dean, B.A.; Moroney, T. Nursing and the Sustainable Development Goals: A Scoping Review. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2021, 53, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador-Mata, B.; Raffio, V.; Cortiñas-Rovira, S. Análisis cualitativo de la percepción de las pseudociencias en el colectivo médico español. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2020, 11, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, R. Indigenous Sciences are not Pseudoscience. In Indigenizing the University: Diverse Perspectives; Widdowson, F., Ed.; Frontier Center for Public Policy: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2021; pp. 175–198. [Google Scholar]

- Cortiñas-Rovira, S.; Salvador-Mata, B. Pseudociencia y Sociedad en España: Estado de la Cuestión e Investigaciones Recientes; Cuadernos Artesanos de Comunicación: La Laguna (Tenerife), Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Foghis, M.; Bungau, S.G.; Bungau, A.F.; Vesa, C.M.; Purza, A.L.; Tarce, A.G.; Tit, D.M.; Pallag, A.; Behl, T.; Ul Hassan, S.S.; et al. Plants-based medicine implication in the evolution of chronic liver diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 158, 114207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malo, B.; Meyer, S.B.; Filice, E.; Graham, J.E.; MacDonald, N.E.; Bettinger, J.A.; Greyson, D.; MacDonald, S.E.; Driedger, S.M.; Kawchuk, G.; et al. “If I’m a naturopath, It’s because I trust nature above everything else”: Canadian naturopaths’ construction of vaccination as a risk object. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2023, 3, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdiguero, E. El fenómeno del pluralismo asistencial: Una realidad por investigar. Gac. Sanit. 2004, 18, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, C.A. The role of evidence in alternative medicine: Contrasting biomedical and anthropological approaches. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 2646–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdiguero, E. Comprender el pluralismo médico. Investig. Cienc. 2019, 514, 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, A.; Smith, M.; Falkenberg, T. Building WHO’s global Strategy for Traditional Medicine. EuJIM 2015, 7, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodworth, K.; Stewart, E. Legitimating complementary therapies in the NHS: Campaigning, care and epistemic labour. Health 2022, 26, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicho, M.; Nikolaeva, R.; Lages, C. Complementary and Alternative Medicine legitimation efforts in a hostile environment: The case of Portugal. Sociol. Health Illn. 2023, 45, 890–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, C. Los Enfermos en la España Barroca y el Pluralismo Médico. Espacios, Estrategias y Actitudes; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2018.

- Balaguer, E.; Ballester, R.; Bernabeu, J.; Perdiguero, E. La utilización de fuentes antropológicas en la historiografía médica española contemporánea. Dynamis 1990, 10, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dykhuizen, M.; Marshall, K.; Walker, R.L.; Saddleback, J. Holistic Health of Two Spirit People in Canada: A Call for Nursing Action. J. Holist. Nurs. 2022, 40, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, M.O.; Gates, M.F. Teaching holistic nursing: The legacy of Nightingale. Nurs. Clin. North. Am. 2007, 42, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libster, M.M. A history of shaker nurse-herbalists, health reform, and the American botanical medical movement (1830–1860). J. Holist. Nurs. 2009, 27, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffin, P.T. A history of massage in nurse training school curricula (1860–1945). J. Holist. Nurs. 2011, 29, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, U.P.; Ludwig, D.; Feitosa, I.S.; de Moura, J.M.B.; Gonçalves, P.H.S.; da Silva, R.H.; da Silva, T.C.; Gonçalves-Souza, T.; Ferreira Junior, W.S. Integrating traditional ecological knowledge into academic research at local and global scales. Reg. Environ. Change 2021, 21, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, J.R.; Verde, A.; González, J.A.; Fajardo, J.; de Sousa Lopes, H.M.; Carrasco Ramos, M.C.; Postigo-Mota, S. La transmisión del conocimiento tradicional como herramienta educativa para promocionar la salud y el envejecimiento activo en mayores. Rev. ROL Enferm. 2022, 45, 288–295. [Google Scholar]

- López, F. El análisis del contenido como método de investigación. Educ. XXI 2002, 4, 167–179. [Google Scholar]

- Mira, J.J.; Pérez-Jover, V.; Lorenzo, S.; Aranaz, J.; Vitaller, J. La investigación cualitativa: Una alternativa también válida. Aten. Prim. 2004, 34, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisterna, F. Categorización y triangulación como procesos de validación del conocimiento en investigación cualitativa. Theoria 2005, 14, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.C. La dicotomía cualitativo-cuantitativo: Posibilidades de integración y diseños mixtos. Campo Abierto 2015, 1, 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bressan, V.; Bagnasco, A.; Aleo, G.; Timmins, F.; Barisone, M.; Bianchi, M.; Pellegrini, R.; Sasso, L. Mixed-methods research in nursing—A critical review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 2878–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honkavuo, L. Nursing students’ perspective on a caring relationship in clinical supervision. Nurs. Ethics 2020, 27, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smajic, E.; Avdic, D.; Pasic, A.; Prcic, A.; Stancic, M. Mixed methodology of scientific research in healthcare. Acta Inform. Med. 2022, 30, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, J.R.; Arco, H.; Roque, S.; González, J.A.; Carrasco, M.C.; Gómez-Navarro, M.E.; Postigo-Mota, S. International project about the introduction of traditional Knowledge on medicinal plants among students of health sciences. In Proceedings of the ICERI 15th Annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville, Spain, 7–9 November 2022; p. 2121. [Google Scholar]

- Galeano Calzado, J. La Medicina Popular en Oliva de la Frontera: Una Aproximación; Universidad de Extremadura: Badajoz, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Penco, A.D. Medicina popular veterinaria en la comarca de Zafra. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gregori, M.P. Medicina popular en Valencia del Mombuey. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, J.R. La etnomedicina en Guadiana del Caudillo (Badajoz). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

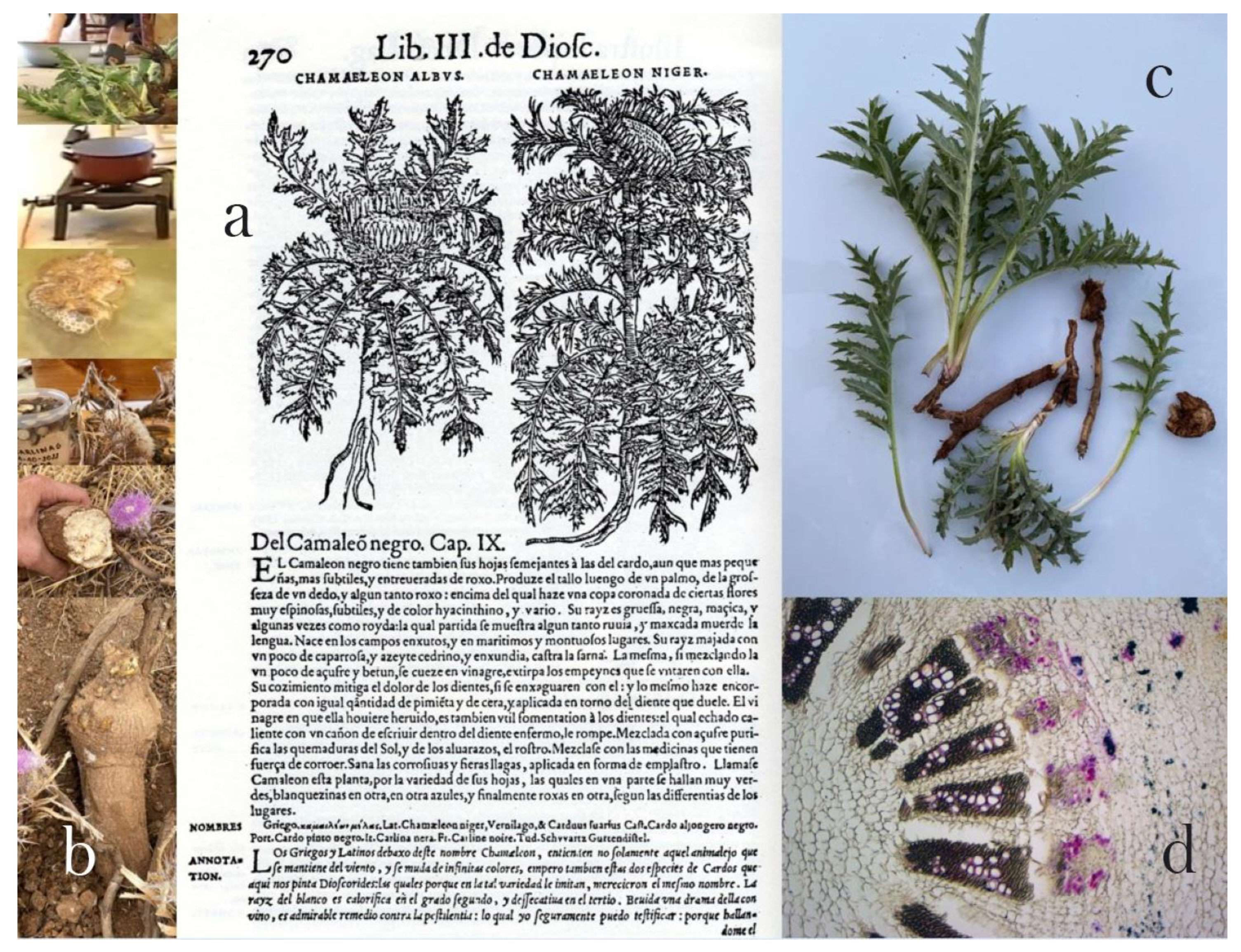

- Vallejo, J.R.; Pardo de Santayana, M.; Peral, D.; Carrasco, M.C.; López, D. Uso medicinal de Atractylis gummifera en Guadiana del Caudillo (Badajoz, España), toxicidad y especies afines. Rev. Fitoterapia 2008, 8, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Alvarado, M.Á. Medicina popular en la ciudad de Badajoz. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Altimiras, J. La transmisión de la medicina popular en Atalaya (Badajoz, Extremadura). Ph.D. Thesis, (unpublished and unread Ph.D. Thesis) [Author’s edition: Vic (Barcelona), Spain, 2014 (DL B-3111-14)]. Universidad de Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fontal Merillas, O.; Marín Cepeda, S. Enfoques y modelos de educación patrimonial en programas significativos de OEPE. Educ. Art. 2011, 2, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Achille, C.; Fiorillo, F. Teaching and Learning of Cultural Heritage: Engaging Education, Professional Training, and Experimental Activities. Heritage 2022, 5, 2565–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castroviejo, S. (coord. gen.). Flora Iberica; Real Jardín Botánico—CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 1986–2021.

- Devesa Alcaraz, J.A. Vegetación y Flora de Extremadura; Universitas Editorial: Badajoz, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, F.M.; García, D.; Márquez, F.; Gutiérrez, M.; Barrena, M.J.; Palacios, M.J.; Sánchez, A. Catálogo Regional de Especies Amenazadas Vegetales de Extremadura; Consejería de Industria Energía y Medio Ambiente—Junta de Extremadura: Badajoz, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ANTHOS. Anthos. Sistema de Información Sobre Plantas de España; Fundación Biodiversidad—Real Jardín Botánico—CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2012–2023. Available online: http://www.anthos.es (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- FLORA-ON. Flora-On. An Interactive Flora of Portugal; Sociedade Portuguesa de Botânica: Alverca do Ribatejo, Portugal, 2012–2022; Available online: https://flora-on.pt (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Vallejo, J.R.; Peral, D.; Gemio, P.; Carrasco, M.C.; Heinrich, M.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Atractylis gummifera and Centaurea ornata in the province of Badajoz (Extremadura, Spain)–Ethnopharmacological importance and toxicological risk. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 126, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo de Santayana, M.; Morales, R.; Aceituno, L.; Molina, M. (Eds.) . Inventario Español de los Conocimientos Tradicionales Relativos a la Biodiversidad. Fase I; Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2014.

- Holubarsch, C.J.F.; Colucci, W.S.; Eha, J. Benefit-risk assessment of Crataegus extract WS 1442: An evidence-based review. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2018, 18, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbella, D.; Fajardo, A. (Eds.) . Español y Portugués en Contacto: Préstamos Léxicos e Interferencias; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG: Berlin, Germany, 2017; Volume 419. [Google Scholar]

- González Salgado, J.A. El proyecto de investigación FRONTESPO y la “fala de Xálima”. Limite 2019, 13, 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, M.F.R. A agonia do português em Olivença. Rev. Filolog. Románica 2001, 18, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, N. Amareleja. Linguagem Regional e Popular; Câmara Municipal de Moura: Moura, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lois González, R.C.; Carballo Lomba, A. La frontera hispano-lusa en la actualidad: Una visión geográfica. Rev. Historiograf. 2015, 23, 191–214. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, F.M. Anotaciones corológicas a la Flora en Extremadura [013 Cynara tournefortii Boiss. & Reuter]. Folia Bot. Extremadurensis 2008, 2, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Anadón, J.; Hernández, C.; Rodríguez, A. Patrimonio y fiestas. La fiesta de San Isidro. In El Patrimonio y la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales; Ballesteros, D., Fernández, C., Molina, J.A., Moreno, P., Eds.; Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha: Cuenca, Spain, 2003; pp. 543–554. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo de Santayana, M.; Morales, R.; Tardío, J.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Molina, M. (Eds.) Inventario Español de los Conocimientos Tradicionales Relativos a la Biodiversidad. Fase II (3 vols.); Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tardío, J.; Pardo de Santayana, M.; Morales, R.; Molina, M.; Aceituno-Mata, L. (Eds.) Inventario Español de los Conocimientos Tradicionales Relativos a la Biodiversidad Agrícola; Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Volumes 2022–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Barrón, T.C. La Educación Basada en Competencias en el Marco de los Procesos de Globalización. Formación en Competencias y Certificación Profesional; CESU—UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zabala, A.; Arnau, L. 11 Ideas Clave. Cómo Aprender y Enseñar Competencias; Graó: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno Sacristán, J. (Ed.) Educar por Competencias, ¿qué hay de Nuevo? Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Victorino Ramírez, L.; Medina, G. Educación basada en competencias y el proyecto Tuning en Europa y Latinoamérica. Su impacto en México. Ide@s CONCYTEG 2008, 3, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Resplandor, G. Tendencias mundiales en la educación por competencias. Guayana Sustentable 2015, 14, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Villa Sánchez, A. Competence-based learning: Development and implementation in the university field. REDU Rev. Doc. Univer. 2020, 18, 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, A. Modelo Institucional de Educación Basado en Competencias. In Innovación Curricular en las Instituciones de Educación Superior; Medina, L., Guzmán, L.L., Eds.; ANUIES: Mexico City, Mexico, 1997; pp. 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Zarate Grajales, R.A. La gestión del cuidado de enfermería. Index Enferm. 2004, 13, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Rodríguez, P.A.; García Campos, M.L. La importancia del cuidado de enfermería. Rev. Enferm. Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2009, 17, 109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara, B.; Evies, A.; Rengifo, J.; Salas, B.; Manrique, D.; Palacio, C. El cuidado de enfermería: Una visión integradora en tiempos de crisis. Enferm. Glob. 2014, 33, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, C. Problemas éticos de la delegación del cuidado de enfermería en personal auxiliar de enfermería. Bachelor’s Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zahourek, R.P. What is Holistic Nursing Research? Is it Different? Beginnings 2006, 26, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Borges, A.M.; Ceolin, T.; Barbieri, R.L.; Heck, R.M. La inserción de las plantas medicinales en la práctica de enfermería: Un creciente desafío. Enferm. glob. 2010, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libster, M.M. The Nurse-Herbalist: Integrative Insights for Holistic Practice; Golden Apple Publications: Wauwatosa, WI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- López Ruiz, J. Els instruments complementaris de les cures infermeres. Àgora Infermer. 2000, 4, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- May, J. What is integrative health? BMJ 2011, 343, d4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perurena, F.C. Institucionalização de práticas integrativas e complementares no Sistema Único de Saúde!? Hist. Cienc. Saude Manguinhos 2014, 21, 361–363. [Google Scholar]

- Habimorad, P.H.L.; Catarucci, F.M.; Bruno, V.H.T.; Silva, I.B.D.; Fernandes, V.C.; Demarzo, M.M.P.; Spagnuolo, R.S.; Patricio, K.P. Implementation of Brazil’s National Policy on Complementary and Integrative Practices: Strengths and weaknesses. Cien. Saude Colet. 2020, 25, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, J.R.; Carrasco Ramos, M.C.; González, J.A.; Reinares Rueda, M.E.; López Herranz, M.L.; Postigo Mota, S. Plantas medicinales de interés en el tratamiento de úlceras y heridas. Rev. ROL Enferm. 2021, 44, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Apaydin, E.A.; Maher, A.R.; Shanman, R.; Booth, M.S.; Miles, J.N.; Sorbero, M.E.; Hempel, S. A systematic review of St. John’s wort for major depressive disorder. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.I.; Pinho, C.; Sarmento, B.; Dias, A.C. Neuroprotective activity of Hypericum perforatum and its major components. Front. Plant. Sci. 2016, 7, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifritz, E.; Hatzinger, M.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E. Efficacy of Hypericum extract WS 5570 compared with paroxetine in patients with a moderate major depressive episode—A subgroup analysis. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2016, 20, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel, A.; Kan, Y.; Yesilada, E.; Akın, O. Effect of St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) oily extract for the care and treatment of pressure sores; a case report. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 196, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Q.X.; Venkatanarayanan, N.; Ho, C.Y. Clinical use of Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) in depression: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 210, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matić, I.Z.; Ergün, S.; Đorđić Crnogorac, M.; Misir, S.; Aliyazicioğlu, Y.; Damjanović, A.; Džudžević-Čančar, H.; Stanojković, T.; Konanç, K.; Petrović, N. Cytotoxic activities of Hypericum perforatum L. extracts against 2D and 3D cancer cell models. Cytotechnology 2021, 73, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revuelta, J. Aportaciones etnobotánicas al estudio Cynara tourmefortii Boiss & Reut. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arber, A. Herbals: Their Origin and Evolution; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, J. Flora Medica: A botanical account of all the more important plants used in medicine, in different parts of the world; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Pensamento e Linguagem [M. Resende, Trans.]; Antídoto: Lisboa, Portugal, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.S.; Collins, A.; Duguid, P. A cognição situada e a cultura da aprendizagem. Pesqui. Educ. 1989, 18, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, X.; Crawford, B.A. Ensinar ciência como um modo cultural de conhecer: Mesclando investigação autêntica, natureza da ciência e estratégias multiculturais. Estud. Cultur. Educação Ciências 2011, 6, 525–547. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, G.C.S. Tables of Contextual Cognition: A proposal for intercultural research in science education. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2018, 13, 845–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkin, N.L. Anthropological methods in ethnopharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1993, 38, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Jäger, A.K. Ethnopharmacology: A short history of a multidisciplinary field of research. In Ethnopharmacology; Heinrich, M., Jäger, A.K., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, J.R.; González, J.A.; Gómez-Navarro, M.E.; López-Cepero, J.M. Histological study of glandular variability in the skin of the natterjack toad—Epidalea calamita (Laurenti, 1768)—Used in Spanish historical ethnoveterinary medicine and ethnomedicine. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, F.; Garbe, L.A. How to approach a study in ethnopharmacology? Providing an example of the different research stages for newcomers to the field today. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2023, 11, e01109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, B.A. O que é natureza da Ciência e qual sua relação com a História e Filosofia da Ciência? Rev. Bras. Hist. Ciên. 2014, 7, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Laso, M.C.; Amores Ampuero, A.; Viciano, J. Experimentando la antropología forense a través del aprendizaje basado en problemas. In Retos y Experiencias de la Renovación Pedagógica y la Innovación en las Ciencias Sociales; Soria Rodríguez, C., Martín López, M.A., Eds.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Galeotti, N. Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) beyond depression: A therapeutic perspective for pain conditions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 200, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesecke, A.; Mabberley, M. (Eds.) A Cultural History of Plants in Antiquity; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Istikoglou, C.I.; Mavreas, V.; Geroulanos, G. History and therapeutic properties of Hypericum Perforatum from antiquity until today. Psychiatriki 2010, 21, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Vega, L. Pharmacopea de la Armada o Real Catálogo de Medicamentos Pertenecientes a las Enfermedades Medicas…; Imp. D. Manuel Ximenez Carreño: Cádiz, Spain, 1759. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, S.E.; Rocha, I.C.; Williamson, E.M.; Heinrich, M. (Eds.) Phytopharmacy: An Evidence-Based Guide to Herbal Medicinal Products; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Butterweck, V. St. John’s Wort: Quality issues and active compounds. In Botanical Medicine: From Bench to Bedside; Cooper, R., Kronenberg, F., Eds.; Mary Ann Liebert Inc.: Larchmont, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Schepetkin, I.A.; Özek, G.; Özek, T.; Kirpotina, L.N.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Quinn, M.T. Chemical composition and immunomodulatory activity of Hypericum perforatum essential oils. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanaclocha, B.; Risco, E.; Cañigueral, S. Interacciones entre preparados vegetales y fármacos de síntesis: Revisión de las monografías de la EMA y ESCOP. Rev. Fitoter. 2014, 14, 5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vanaclocha, B.; Cañigueral, S. Tabla de Interacciones entre Preparados Vegetales y Fármacos de Síntesis, Basada en las Monografías de la EMA y ESCOP (updated 24 July 2021). Available online: www.fitoterapia.net (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy. ESCOP Monographs, The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products; Online series; Hyperci herba (St. John’s Wort); ESCOP: Exeter, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- EMA/HMPC/101304/2008; European Medicines Agency (EMA)—Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). Community Herbal Monograph on Hypericum perforatum L., herba (well-Established Medicinal Use). EMA: London, UK, 2009.

- EMA/188804/2017; European Medicines Agency (EMA)—Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). European Union Herbal Monograph on Hypericum perforatum L., herba (Traditional Use) Draft. EMA: London, UK, 2018.

- EMA/HMPC/7695/2021; European Medicines Agency (EMA)—Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). European Union Herbal Monograph on Hypericum perforatum L., herba (well Stablished and Traditional Use) 2nd Draft—Revision 1. EMA: London, UK, 2021.

- EMA/HMPC/244315/2016; European Medicines Agency (EMA)—Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). Assessment report on Hypericum perforatum L., herba. 2nd Draft—Revision 1. EMA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021.

- EMA/HMPC/45511/2017; European Medicines Agency (EMA)—Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). List of references supporting the assessment of Hypericum perforatum L., herba. 2nd Draft—Revision 1. EMA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021.

- Avila, C.; Whitten, D.; Evans, S. The safety of St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) in pregnancy and lactation: A systematic review of rodent studies. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 1488–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natural Medicines Database. Denver: Therapeutic Research Center. Available online: https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Vuko, E.; Dunkić, V.; Ruščić, M.; Nazlić, M.; Mandić, N.; Soldo, B.; Šprung, M.; Fredotović, Ž. Chemical composition and new biological activities of essential oil and hydrosol of Hypericum perforatum L. ssp. veronense (Schrank) H. Lindb. Plants 2021, 10, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMA. Medicine (Herbal) [Internet]. European Medicines Agency’s [updated 18 April 2021], Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Available online: www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/herbal (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Antonovsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelmark, M.B.; Bauer, G.F. Salutogenesis as a Theory, as an Orientation and as the Sense of Coherence. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis, 2nd. ed.; Mittelmark, M.B., Bauer, G.F., Vaandrager, L., Pelikan, J.M., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Lindström, B., Magistretti, C.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sagy, S. Salutogenesis beyond Health. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis, 2nd. ed.; Mittelmark, M.B., Bauer, G.F., Vaandrager, L., Pelikan, J.M., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Lindström, B., Magistretti, C.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 223–224. [Google Scholar]

- Pelikan, J.M. Applying salutogenesis in healthcare settings. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis, 2nd. ed.; Mittelmark, M.B., Bauer, G.F., Vaandrager, L., Pelikan, J.M., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Lindström, B., Magistretti, C.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Makoge, V.; Maat, H. Using salutogenesis to understand people-environment interactions that shape health in a context of poverty. In Global Handbook of Health Promotion Research, Vol. 3: Doing Health Promotion Research; Jourdan, D., Potvin, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Zapatero, M.; Pardo de Santayana, M. Conocimiento y uso de plantas medicinales en estudiantes universitarios. Rev. Fitoter. 2015, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz-Santillán, M.P.; Mejía Coico, F.; Ramírez Vargas, R.; Mejía Ruíz, B. Utilidad, uso y formas de consumo de plantas medicinales relacionadas a variables sociodemográficas en estudiantes universitarios 2017. REBIOL 2018, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, M.T.Á.D.; Pereira de Carvalho, V.; Porcino, C. Representações sociais de doença, usos e significados atribuídos às Práticas Integrativas e Complementares por universitários. Saúde em Debate 2019, 43, 848–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badke, M.R.; Bastos Cogo, S.; Dutra, G.; Monteiro, A.S.; Ferreira Scopel, M.; Martorell-Poveda, M.A. Significados do uso de plantas medicinais para docentes do curso de enfermagem na Catalunha. Saúde Soc. 2021, 30, e200963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio-Cantalejo, I.M.; Simón-Lorda, P.; Melguizo, M.; Escalona, I.; Marijuán, M.I.; Hernando, P. Validación de la Escala INFLESZ para evaluar la legibilidad de los textos dirigidos a pacientes. An. Sist. Sanit. Navarra 2008, 31, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| TREATED AILMENT | TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE (ETHNOMEDICINE) | HISTORICAL KNOWLEDGE | SCIENTIFIC OR ACADEMIC KNOWLEDGE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recorded information on empirical or magical uses | Main constituents | Academic validations | Pharmacological action | ||

| Trauma, injuries and wounds | Present study and IECTB Healing wounds, bumps and inflammations, nappy rash, rashes, chafing, burns, bumps, sprains, strains, sprains, blood and bruises It is prepared by macerating the flowers in alcohol or wine, or by frying them in lard or decoctions [68,87] (see 68, pp. 145–154) Present study and IECTB In general, to treat all types of skin conditions. St. John’s wort oil has also been applied to diaper rash [68] (pp. 145–154) | Documented by ancient Greek medicals for the healing of burns and superficial wounds [107,108]. The most relevants were Hippocrates (ca. 460-370 b.C.), Theophrastus (371-286 b.C.), Dioscorides (first century) and Galen (ca. 130–220) [107,108]. In the Renaissance, Paracelsus (1493- 1541 AD) stands out for his Theory of Signatures and the works Gerard (1597, 1633) and Culpeper (1652) [107,108]. Soldier’s or military Weed: the military had to wear it in wars [107,108,109]. In the 18th century, it was used by European surgeons, and was part of the drugs taught at the Royal Colleges of Surgery as the surgical college of the Navy of Cadiz. Included in Pharmacopoeia of the Spanish Navy by D. Leandro de Vega [110] and the first London Pharmacopoeia [107,108,109] | Dianthronol and anthranolic derivative pigments, flavonoids in the flowers and essential oil, especially rich in α- pinene (monoterpenes) Naphthodianthrones (hypericin), pseudohypericin, isohypericin and protohypericin. Hyperforin, a prenylated derivative of floroglucinol Flavones and flavonols (quercetin, quercetin, isoquercitrin and rutin) Catechin tannins, xanthones and biflavonoids, phenolic acids (caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid and ferulic acid) [111,112,113] | Approved for use of oil extracts in skin inflammations (sunburn) and in the healing of minor or superficial wounds by Commission E as ESCOP monograph and EMA [111,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123] Scientifically validated oil preparations and essential oil as antibacterial. Anti- inflammatory, antifungal and antiviral activity [111,123] | Vulnerate effect due to its tannin and essence content. Reduces the inflammatory reaction in the wound or bruise. Hyperforin is the component responsible for its anti-inflammatory activity. Mechanism: Inhibits both protein kinase C and NF-kB (nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells) activation and inhibition of arachidonic acid and leukotriene B4 release. Strengthening the skin’s barrier function by reducing radical formation and collagen synthesis in vitro. Antiseptic and antimicrobial action due to hypericin and hyperforin [111,124] |

| TREATED AILMENT | TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE (ETHNOMEDICINE) | HISTORICAL KNOWLEDGE | SCIENTIFIC OR ACADEMIC KNOWLEDGE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recorded information on empirical or magical uses | Main constituents | Academic validations | Pharmacological action | ||

| Emotional disorders and mental illnesses | Present study Depression and mood disorders IECTB Treat depression, nerves and anxiety by infusing a handful of flowers. They are also used together with the dried fruit [68] (pp. 145–154) | Ancient Greek medicals: Treatment for depression or melancholy [107,108,109] Middle Ages: "Fuga daemonum" (see Gulielmus van Limborch, 1679), it frightened the demons (in Spain: “espanta diablillos”), their dried bundles were burnt, which were hated by the demons. Used in the inquisition to force confessions of guilt [107,108,109] | Hyperforin and adhyperforin stand out above all. In addition, there are other interesting components such as hypericin [89,90,91,92,93,114,115,125] | Level of evidence for mild depression: "strong scientific evidence” [89,90,91,92,93,125] Various medical associations recommend its use for mild to moderate depression (see for example, American College of Physicians recommendations, the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, CANMAT). The European Medicines Agency [125] updated its monograph and documentation about St. John’s wort in 2021. This readjustment highlights the updated drug assessment report [120] and a document listing the references analyzes [121]. | Mechanism: Suspension of monoamine oxidase (MAO) and serotonin reuptake suspension [109] |

| TREATED AILMENT | TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE (ETHNOMEDICINE) | HISTORICAL KNOWLEDGE | SCIENTIFIC OR ACADEMIC KNOWLEDGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circulatory disorders | Data in the IECTB Lowering blood pressure on its own or with other spices, and as a cardiac tonic [68] (pp. 145–154) Present study and IECTB Anti-hemorrhoidal use [68] (pp. 145–154) | — | — |

| Digestive diseases | Data in the IECTB Oral antiseptic and toothache with rinsing or chewing. Spirits and infusions with digestive properties. Treats diarrhoea and stomach pains caused by nerves. It is also said to have the opposite properties (laxative) and to cleanse the liver [68] (pp. 145–154) | Ancient Greek medicals as Galen, recommended it as treatment for gastrointestinal distress [107,108] | — |

| Genito-urinary diseases | Data in the IECTB Incontinence in the elderly, treatment of kidney stone, to "clear the urine" Recommended to be taken together with horsetail (Equisetum sp.), to treat urinary tract infections. Infusions have been taken to relieve menstrual cramps [68] (pp. 145–154) | Ancient Greek medicals recommended it as treatment for diuretic and menstrual cramping. [107,108] | — |

| Respiratory disorders | Data in the IECTB Bronchial remedy, as an anticatarrhal and anti-influenza, sometimes mixed with mallow flower (Malva sylvestris L.) [68] (pp. 145–154) | — | — |

| Ailments in sense organs | Data in the IECTB Cure otitis with macerated flowers. with Infusion of the inflorescence used in eye drops as an ocular antiseptic [68] (pp. 145–154) | — | — |

| Parasitic diseases | Data in the IECTB The infusion of the flowers has been used to treat intestinal worms [68] (pp. 145–154) | Ancient Greek medicals recommended it as treatment for intestinal worms [107,108] | — |

| Poisonings and intoxications | Data in the IECTB Insect bites are treated with St. John’s wort oil [68] (pp. 145–154) | Ancient Greek medicals recommended it as treatment for snake or reptile bites. In the 16th and 17th century for stings and bites of poisonous animals (see Gerard, 1597 and 1633, Culpeper, 1652) [107,108] | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vallejo, J.R.; Baptista, G.C.S.; Arco, H.; González, J.A.; Santos-Fita, D.; Postigo-Mota, S. Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Heritage about Medicinal Plants in a European Transboundary Area (La Raya: Extremadura, Spain—Alentejo, Portugal): Transdisciplinary Research for Curriculum Design in Health Sciences. Heritage 2024, 7, 225-258. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7010012

Vallejo JR, Baptista GCS, Arco H, González JA, Santos-Fita D, Postigo-Mota S. Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Heritage about Medicinal Plants in a European Transboundary Area (La Raya: Extremadura, Spain—Alentejo, Portugal): Transdisciplinary Research for Curriculum Design in Health Sciences. Heritage. 2024; 7(1):225-258. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleVallejo, José Ramón, Geilsa Costa Santos Baptista, Helena Arco, José A. González, Dídac Santos-Fita, and Salvador Postigo-Mota. 2024. "Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Heritage about Medicinal Plants in a European Transboundary Area (La Raya: Extremadura, Spain—Alentejo, Portugal): Transdisciplinary Research for Curriculum Design in Health Sciences" Heritage 7, no. 1: 225-258. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7010012

APA StyleVallejo, J. R., Baptista, G. C. S., Arco, H., González, J. A., Santos-Fita, D., & Postigo-Mota, S. (2024). Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Heritage about Medicinal Plants in a European Transboundary Area (La Raya: Extremadura, Spain—Alentejo, Portugal): Transdisciplinary Research for Curriculum Design in Health Sciences. Heritage, 7(1), 225-258. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7010012