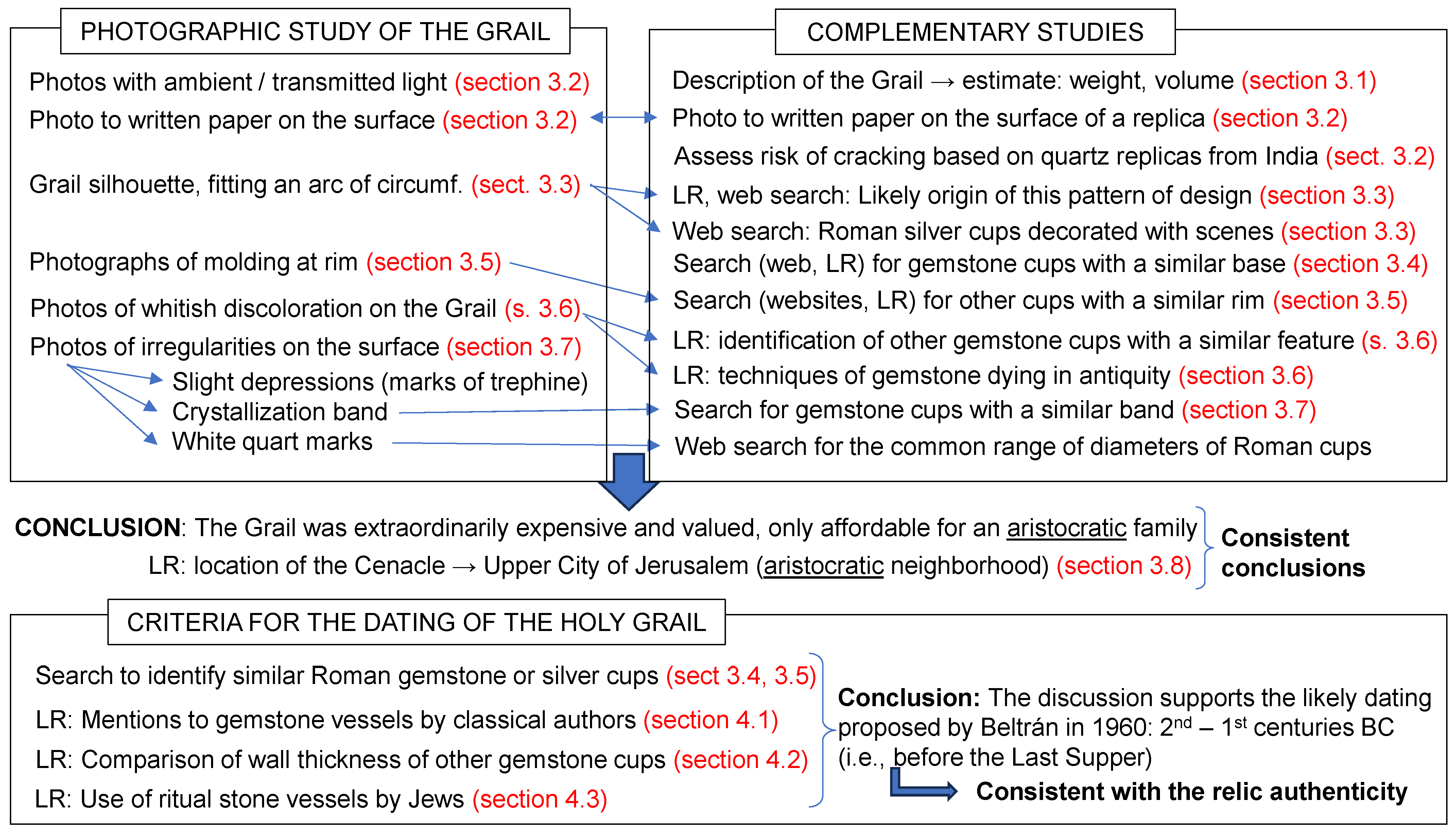

3.1. Overall Description of the Holy Grail

The Holy Chalice was kept for several centuries in the reliquary cabinet at the sacristy of Valencia’s Cathedral. In order to enable veneration by the faithful, it was moved to the former Chapter Room of the Cathedral in 1916, which was designated as the Chapel of the Holy Chalice (

Figure 2). The Chalice is located in a recessed reliquary behind the altar, with a golden background to highlight the artifact. Unfortunately, it has to be viewed at a minimum distance of about 4 m because the altar area (presbytery) is reserved for liturgical use, meaning that it is not possible to get closer to observe the beauty of this famous chalice. The color of the gemstone cup appears to be quite uniform because agate bands or stripes cannot be clearly appreciated at this distance, and the Grail looks rather opaque. In the publication by Beltrán [

23], photographs were in black and white, so subtle details could not be appreciated.

From a typological standpoint, the Holy Grail is an agate bowl with reddish-brown tones, roughly hemispherical in shape with an ovoid tendency [

27] (p. 32). The different tones of brown between bands seem to be caused by dissimilar concentrations of the pigments providing the color. The bowl has a differentiated base or pedestal that is hidden by a platen joined to the chalice stem. This base, with a height of less than 1 cm, is not cylindrical but ring-shaped, with concave recessed molding at its junction with the bowl. According to Beltrán [

23] (p. 55), the cup measures about 6.5 cm in height (including the pedestal) and 9.5 cm in diameter, with a wall thickness of about 3 mm. The surface is smooth and perfectly polished. The only visible decorative motif is incoming molding at the rim, half-round, shallow, and of unequal width [

27] (p. 32).

Taking into account that the density of agate is 2.58–2.64 g/cm3, and based on a mathematical model with the dimensions of the Holy Grail, its weight has been estimated as 205 g (±15 g). In the experiments of April 2018, the total weight of the Holy Chalice was determined to be 677 g (±0.1 g), which implies that the agate cup accounts for about 30% of the total chalice weight.

The Holy Grail has a volume of around 220 mL. Considering that Jesus distributed the cup of wine among the apostles at the Last Supper (Mt 26:27), that cup would not be excessively full to prevent the wine from spilling. As such, it is estimated that the Holy Grail might have contained approximately 150 mL of wine in that ritual celebration, a volume that remains 1 cm below the rim.

3.2. Translucent Character and Wall Thickness

One of the most striking results of the research carried out is that the Grail is much more translucent than expected. When it is illuminated from within, the appearance changes dramatically. Some of the bands seem to be white when observed with reflexed light (

Figure 3a), but when applying transmitted light (

Figure 3b), it becomes apparent that these bands are translucent. The alternance of colorless vertical stripes with others, yielding reddish-brownish tones, leads to an extraordinarily beautiful image when applying warm lighting (

Figure 3b). This appearance is somewhat reminiscent of a burning flame. Based on this similarity, it has been speculated that one verse of the book of Revelation might be an implicit description of the Holy Grail: “a kind of translucent

sea mingled with fire” (Rev 15:2). The expression “a kind of sea” would indicate a figurative sense, maybe in reference to the Sea of Bronze of the ancient Temple (1 Kings 7:23–25), which had a hemispherical shape [

28]. As the Last Supper was celebrated with the light of candles or oil lamps (i.e., warm lighting), the appearance of the Holy Grail in

Figure 3b would be more or less the appearance of the agate cup when Jesus instituted the Eucharist.

The foot of the Holy Chalice is also made of stone, with perimetric goldsmithing (

Figure 3), which is rather uncommon for medieval chalices. This foot was described by Beltrán as being made of chalcedony, “very diaphanous against the light” [

23] (p. 57). Expert researchers in gemology have concluded that the upper cup and the gemstone at the foot can be classified as banded agate [

26] (p. 94). One discovery was that both gemstones acquire extraordinarily similar tones when the Chalice is illuminated from below and above (

Figure 3b). This color similarity was not expected because the foot is dated to the 10th–11th centuries AD [

23] (p. 112). This coincidence in the appearance of both gemstones composing the Holy Chalice leads to speculation that the foot was carefully sought to resemble the Grail as much as possible, which was not an easy task in medieval times given the scarcity of agate bowls in the Iberian Peninsula.

In order to qualitatively establish how translucent the Grail is, we wondered if it would be possible to read a text by looking from inside the cup and placing a written paper outside of it, touching the surface. The experiment was carried out, and indeed,

Figure 4a shows an infrared photograph revealing that a text written in Latin can be read [

29]. The same text was placed on the surface of an agate bowl (

Figure 4b), which is a replica of the Holy Grail purchased from Yasin Agate manufacturer, a local workshop in Khambhat, India. This bowl weights 213.5 g with a diameter at the rim of 9.8 cm, which implies similar dimensions and weight compared with the Grail.

The translucent overall character of both bowls, which is apparent from

Figure 4, is partly due to their rather thin walls. In Beltrán’s study, the wall thickness of the Holy Grail was described as about 3 mm [

23] (p. 54), but the detailed visual inspection of the Chalice the author carried out revealed that this thickness is slightly lower at the rim. Hence, it seems more correct to consider an approximate wall thickness of ≈4 mm. One part of the investigation performed was a metrological characterization of the Holy Chalice with a 3D scanner [

30]. Ongoing research based on this 3D model will provide an accurate description of the dimensions, which is of relevant interest in elucidating how the Grail was handcrafted and will enable a comparison with analogous gemstone vessels.

The origin of the raw agate rock (geode) from which the Grail was carved is unknown. According to Pliny the Elder (1st century AD), the size of agate “exceeds any other stones of this class”. The deposits of this material were located in India and in areas of the eastern Mediterranean such as Sicily, Phrygia, Thebes (Egypt), Cyprus, Trachinia, Mount Parnassus, the Isle of Lesbos, Messene, and Rhodes [

31].

In ancient times, many of the raw gemstones used to carve prized vessels, mainly the largest ones, came from India [

32] (p. 23), ref. [

33] (pp. 398–400). In this country, one of the places that has maintained the tradition of carving vessels from hard stones for centuries is the city of Khambhat [

32] (p. 23), ref. [

34]. A workshop in this city was requested to manufacture a few replicas of the Holy Grail in clear crystal quartz, with dimensions as similar as possible to the original and with a wall thickness of about 4 mm. Pictures of these cups are available from the author upon request. According to this workshop (Yasin Agate; owner, Yasin Bapu, 45 years in the business), the risk of cracking during the manufacture of bowls like this one increases considerably when the wall thickness is less than 5 mm. In fact, it turned out that five out of eight cups cracked while being crafted despite having an average thickness of about 6 mm. This wall thickness was estimated mathematically from the weight of the cups, assuming an approximately hemispherical shape and a density of 2.6 g/cm

3 for quartz. This experimental proof illustrates the considerable risk of fracture that would have existed in gemstone vessels in antiquity.

This same workshop was also commissioned to craft twelve replicas of the Grail in tiger-eye agate. The weight of these cups ranged from 209 g to 256 g, with seven of them being heavier than 220 g (i.e., the estimated upper boundary for the Grail’s weight). This result reveals a bias toward manufacturing bowls thicker than the Holy Grail, probably because the workshop intended to reduce the risk of cracking. Given the difficulty nowadays of carving gemstone cups with a wall thickness like that of the Holy Grail, despite the availability of modern techniques, this suggests that there would be a non-negligible risk of cracking or fracture during their manufacture in the Hellenistic–Roman period. Such risk is difficult to estimate (5/8 according to the experiment mentioned), but it would undoubtedly result in a higher cost for the final product (i.e., a 50% risk of cracking would double the price of a manufactured gemstone vessel sold in the market).

It is postulated that the wall thickness of the Holy Grail is similar to that of gemstone bowls from the time when it was carved. A thin wall was desirable for the greatest translucency, which was a highly appreciated property. In fact, regarding agate gemstones, Pliny mentions that “some persons set the highest value upon those stones which presented a transparency like that of glass” [

31]. A reduced wall thickness would favor the demand for these precious vessels, despite increasing their fragility and the risk of cracking during manufacture, ultimately resulting in a higher price.

3.3. Pattern of Design of the Holy Grail

Regarding the Grail’s typology, it is one of the simplest and most common forms of classical tableware. Therefore, the dating criteria that can be applied to this piece, for which the place and archeological context of the discovery are unknown, are based both on the type of material from which it was carved and on the shape or the pattern of the design [

24] (p. 167, 177).

According to a metrological characterization of the Holy Chalice carried out in 2018 with a high-resolution 3D scanner [

30], the diameter at the rim is about 9.7 cm (

Figure 5a), although Beltrán indicated a value of 9.5 cm [

23] (p. 55). One novel finding not reported yet is that the pattern of the design, or outline, of the Grail fits with surprising precision with an arc of radius of approximately 7.2 cm, the center of which is located on the upper edge, so the tangent line to this arc, at the rim, becomes vertical (

Figure 5a). However, in the side view of the Chalice, this silhouette is not so precise, with a maximum deviation from the target outline of about 2.5 mm near the base (

Figure 5b) but not on the opposite side. This outer pattern can be described as an ogival shape truncated at the base. An ogive is defined as a figure formed by two equal arcs of circumference intersecting at one of their ends, forming a tip.

This particular pattern of design, which was achieved with astonishing precision (

Figure 5a), undoubtedly indicates that the Grail was carved according to a model existing at the time. The likely origin of this pattern is discussed next. If an ogival profile, typical of a Gothic arch, is rotated around its axis of symmetry, it becomes an ogival surface of revolution, which is characteristic of ancient Persian domes. This fact leads to the hypothesis that the outer pattern of the Grail (i.e., a flat-based ogival shape) can be traced back to Persian culture. In fact, this ogival shape is found in a terracotta bowl (4200–3800 BC) preserved at the Louvre Museum (Paris), discovered in the Persian city of Susa (

Figure 6a) [

35]. Another similar bowl was found in Tall-i Bakun, near Persepolis (present-day Iran), dating to the beginning of the 4th millennium BC [

36].

This typology was maintained during the Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 BC). The commercial development of this empire supposedly led to the expansion of this pattern throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Subsequently, this design was assimilated by Classical Greece in fused glass bowls (see [

37] as an example) and in ceramic vessels. Some Greek terracotta skyphos also present an ogival shape with a flat base, such as one at the Met Museum in New York, dated around 460 BC (

Figure 6b) [

38]. The ogival typology mentioned persisted in the Hellenistic world until the 1st–2nd centuries BC with the name “mastos”, a Greek word meaning udder (see

Figure 6c [

39] as an example of an attic black-figure mastos, 520–500 BC).

Figure 6.

(

a) Terracotta bowl decorated with wavy lines, Susa I (4200–3800 BC). Louvre Museum, Paris, France (Near Eastern Antiquities, Room 7) [

35]. (

b) Greek terracotta skyphos, ca. 460 BC, on view at the Met Museum (New York, NY, USA), gallery 171 [

38]. (

c) Attic black-figure mastos (520–500 BC), on view at Getty Villa (Los Angeles, CA, USA), ref. 90.AE.122 [

39].

Figure 6.

(

a) Terracotta bowl decorated with wavy lines, Susa I (4200–3800 BC). Louvre Museum, Paris, France (Near Eastern Antiquities, Room 7) [

35]. (

b) Greek terracotta skyphos, ca. 460 BC, on view at the Met Museum (New York, NY, USA), gallery 171 [

38]. (

c) Attic black-figure mastos (520–500 BC), on view at Getty Villa (Los Angeles, CA, USA), ref. 90.AE.122 [

39].

Gemstone cups from the Hellenistic–Roman period like the Grail are supposed to imitate the goblets decorated with scenes, which were very popular throughout the Mediterranean area among the aristocratic classes to inspire discussion at refined banquets and as a sign of opulence to impress guests [

24] (p. 167). Many of these silver cups are preserved in museums and private collections, dating from the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD, most of them with handles and a differentiated foot.

Figure 7a shows a Roman silver goblet dated between 25 BC and 100 AD, with an ogival profile [

40]. Another similar vessel is the so-called Warren Cup (15 BC–15 AD) found near Jerusalem (

Figure 7b) [

41].

3.4. Base of the Holy Grail

The base or pedestal of the Grail is not observed, as it is hidden by a small gold bowl joined to the Chalice stem. According to Beltrán [

23] (p. 55), this bowl has a height of 1 cm and a diameter of 5 cm, which implies that the base of the Holy Grail is slightly smaller, about 4.5 cm in diameter [

24] (p. 166), or perhaps up to about 4.7 cm. In comparison with the outline of two other similar Roman cups on display at the British Museum [

42,

43], it has been estimated that the pedestal of the Grail has a height of about 7 mm. This base cannot be cylindrical; otherwise, the firm attachment of the Grail to the Chalice stem would not be possible. On the contrary, this pedestal is assumed to be shaped as a convex molding at the bottom and concave at the joint with the cup. This recessed molding, annular or ring-shaped, allows the gemstone to be fastened to the gold stem by means of a toothed platen that remains hidden in the aforementioned gold bowl.

This pattern of design at the Grail’s pedestal is probably intended to somehow imitate the foot of silver Roman cups (

Figure 7). The same profile as the Grail’s base is found in two sardonyx bowls displayed at the British Museum, already mentioned, both dated around 1–50 AD [

42,

43], as well as in a skyphos carved in rock crystal at the time of Emperor Augustus (27 BC–14 AD) (

Figure 8a), with decorations of leaves, preserved at the National Archeological Museum of Naples, Italy [

44]. An agate cup belonging to a private collection, dating from the 1st century BC, has an outline very similar to that of the Holy Grail, including the ring-shaped base and molding at the rim (

Figure 8b) [

32] (p. 79), ref. [

45]. This resemblance reinforces the hypothesis of a similar dating for the Grail.

3.5. Molding at the Rim of the Holy Grail

Luxurious Roman silver cups commonly had a plain rim, clearly differentiated from the main body decorated with varied motifs (see

Figure 7 as examples). The rim of the Grail has been described as half-round molding: shallow and unequal in width [

27] (p. 32). It is like a groove running along the cup perimeter, below the rim. This molding was rather common in gemstone cups. In fact, the repertory of Del Bufalo [

32] comprises at least seven Roman cups with a rim like that of the Holy Grail, with the following references: 21 (p. 50), 49 (p. 56), 78 (p. 63), 124 (p. 79), 270 (p. 131), 302 (p. 144), and 303 (p. 144).

The design of the Grail’s rim might be considered merely aesthetic, trying to imitate the luxurious silver cups of that time. However, there might be certain functionality for this molding. When drinking from a conventional glass or cup without any type of molding at the rim, which is the common case nowadays, it is well known that a small amount of liquid slowly drips from the edge downward. This is not a problem if the liquid is transparent, but in the case of wine, in a context in which the cup is held for a long time like at a banquet, these drops can drain and fall to the floor or stain clothes. However, with the molding at the rim of the Holy Grail, being like a shallow incision, the surface tension of the liquid would allow this small amount of wine to be channeled horizontally following the groove of this molding, achieving a reduction in dripping. Hence, the molding at the rim of the Grail suggests that this cup was carved for the purpose of containing wine, since such molding would not be necessary in a water cup given that water drops do not stain. It is appealing that the cup of blessing presumably used by Jesus to institute the Eucharist was carved deliberately with the intention of containing wine.

After searching on the internet for images of Roman silver cups, one was found whose rim looks quite similar to that of the Grail. It is the so-called Cup with Cranes (

Figure 9), dated between 25 BC and 50 AD. Its relief decoration with cranes recalls the landscape of the Nile River, which suggests that the cup was crafted in Alexandria, Egypt, according to the museum curators [

46]. This bowl has a diameter at the rim of 10.3 cm, which is slightly higher than the Grail, which is 9.7 cm [

30].

Although the silhouette of the Cup with Cranes is slightly different from that of the Holy Grail, being rounded at the base and not flat, the rim molding has an irregular appearance, not very marked, just like the Grail. Moreover, the width (relative to the cup height) coincides in both cups, as shown in

Figure 9. In contrast, Roman silver cups usually had a wider plain rim (see right section of

Figure 9). The resemblance of the rim between the Cup with Cranes and the Grail suggests similar dating and that the latter was probably crafted in Alexandria as well. Beltrán [

23] (p. 76) also considers this possibility, although he broadens the likely place of manufacture to the workshops of Egypt, Syria, or Palestine, from Alexandria to Antioch.

The supposed manufacture of the Cup with Cranes in Alexandria is relevant to the present research because most vessels carved in precious stone in the Roman world are assumed to have been produced in this Mediterranean city. In Egypt, there was an ancient tradition of manufacturing containers carved with lathes from hard stones like granite, diorite, syenite, basalt, etc. [

47]. This is confirmed by the enormous number of these vessels, more than ten thousand, found at the Saqqara site near Memphis [

48]. Some of them, dated to about 3100–2500 BC, are on view at Cairo’s Museum.

The Egyptians built the so-called Canal of the Pharaohs, joining the Nile River with the Red Sea. Its construction may have started as early as ca. 1850 BC, but scholars suggest that it was either re-dug or possibly completed by Darius the Great (522–486 BC) [

49]. This maritime route enabled navigation from the Nile River to the Indian Ocean, which favored the economic development of Egypt by getting rid of the caravan peoples of Arabia who demanded payment for customs. In 331 BC, Alexander the Great founded the city of Alexandria as the capital of Egypt, which became the main Greco-Roman center of culture and business.

Since the reign of Ptolemy II (285–246 BC) but especially at the end of the 2nd century BC, Egyptians have explored the sea routes of Africa and India. Permanent routes to India were opened, with commercial ships leaving from Alexandria. The Indus River area was rich in deposits of different varieties of quartz, particularly agate, carnelian, rock crystal, onyx, and sardonyx. These raw gems traveled to Egypt, mainly to Alexandria. Faced with a supply of relatively large precious geodes from India, the lapidary craftsmen of Alexandria boosted the manufacture of gemstone vessels, which were shipped throughout the Roman Empire. As a result, this city became the main producing center for precious vessels [

32] (p. 23), ref. [

33] (pp. 398–400), which formed part of the tableware used by the elites as a symbol of social distinction [

24] (p. 177).

3.6. Whitish Discoloration on the Surface of the Gemstone

The Grail has a fracture as a result of an accidental fall suffered in 1744 [

23] (p. 56). A silversmith recomposed the larger fragments, with the exception of a small shard, approximately triangular in shape, which is missing at the rim [

27] (p. 32), as can be observed in

Figure 10a.

One of the most striking aspects that arises when observing the Holy Grail is a whitish discoloration present on one side in its rearview (

Figure 10a). The Holy Chalice has always been displayed in the Cathedral chapel in its front view so that this discoloration is not noticeable to visitors, and it remains largely unknown. Surprisingly, there is no written reference to this whitish area in the first documents describing the Chalice, probably because it was considered a natural characteristic of the stone [

26] (p. 102).

This faded color is very apparent; it extends up to the rim but, curiously, not inside the cup. In fact, this discoloration is barely noticeable when the Grail is illuminated from within (

Figure 3b), which implies that it is very superficial, and hence, it was not present in the original raw gemstone. This discoloration had to occur on the carved vessel, but it is unknown how and when it happened. It can only be stated that it was produced prior to 1663 because the whitened area is represented in an engraving of the Holy Chalice from that date, which is exhibited at the Museum of Valencia’s Cathedral.

It has been postulated that the faded area could have been produced by the application of some product on the Grail’s surface [

27] (p. 32), assuming that it was caused accidentally by some substance with which only one area of the cup was in contact. Maybe some type of acid, perhaps soaked on a cloth. Osacar and Naya speculate that it could be sulfuric acid [

26] (p. 102), but this hypothesis requires experimental investigation.

Scholars have always assumed that the color of the Holy Grail is natural for the raw agate stone from which the cup was carved. Hence, discoloration would have occurred in this area because of some aggressive agent producing superficial damage, eliminating the natural coloring pigment [

26]. By contrast, another possibility would be that the original stone from which the Grail was crafted was whitish in appearance and the cup was dyed once carved, so the whitish discoloration would be a depigmentation or fading of the artificially dye added.

The hypothesis that the Grail was dyed raises some concerns. For example, it becomes uncertain why some translucent bands alternate with others yielding brownish tones. If the Grail was dyed after being carved, it would be expected to find all bands with pigment, to a greater or lesser extent. Experts explain that the amount of dye absorbed depends on the degree of compaction of the quartz microcrystals [

50]. Given the crystalline structure of agate, its layers can absorb different amounts of dye, while other layers can absorb none at all [

32] (p. 26). Quartz is a crystalline mineral composed of silicon dioxide (SiO

2), so the atoms are linked in a continuous framework of silicon–oxygen tetrahedra that does not allow for the diffusion of organic dyes. Agate and other varieties of chalcedony are also composed of silicon dioxide, but the crystal structure is less compact, allowing for the diffusion of coloring substances. In agate, not all bands have exactly the same degree of compactness in the crystal structure, mainly because of the speed at which that layer is formed (i.e., a slower speed gives rise to more compact crystals). Thus, when agate vessels are dyed, the more compact bands hinder the diffusion of the coloring pigment inward [

50].

There is strong evidence supporting that it was common in antiquity to dye gemstone vessels. The British Museum exhibits a fragment of an agate bowl with a flat base from the Neo-Assyrian period (production date, 680–669 BC) found in Nineveh (present-day northern Iraq) [

51].

Figure 10b displays a broken section of this bowl. It can be observed that the inner part of the agate is less colored and that the pigment has diffused only through a few millimeters; it has not penetrated the full thickness of the stone [

32] (p. 51). Although this bowl is much older than the Holy Grail, it proves that the pigmentation of gemstones was common in ancient times to improve their visual appearance [

50]. One of the methods was cooking with honey [

32] (p. 24–25), as described by Pliny the Elder: “

these are said to be boiled in honey without interruption for seven days and nights (…) In general, all gems are rendered more colorful by being cooked thoroughly in honey” [

52].

This artificial coloring is also apparent in some gemstone vessels that have partially lost their color. For example, one Roman agate cup from a private collection (c. 1st BC–c. 1st AD) has lost some caramel brown coloration on the rim [

32] (p. 30, 111). The Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna exhibits a large agate dish that appears rather whitened, probably because of the dilution of the caramel treatment over the centuries [

32] (p. 31, 46). A similar case is a skyphos at the Louvre Museum in Paris, with a whitened pale appearance, probably because it lost its dye treatment with honey caramel [

32] (p. 67). The same applies to a vase held at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London [

32] (p. 58).

One of the singularities of the Holy Grail is that the agate bands or stripes are arranged vertically (

Figure 11a,b). This feature is quite atypical because agate is formed when a rock cavity is progressively covered on the inside in concentric layers that grow inward. Agates are most commonly found as nodules within the cavities of volcanic rocks, denoted as geodes. Cavities are then filled in with silica-rich fluids. Layers are slowly deposited on the cavity walls, working their way inward. Therefore, if a cup is carved from a conventional agate geode, the bands cannot be parallel but concentric.

The aforementioned workshop in Khambhat was asked about what type of agate or variety of chalcedony could give rise to a bowl with parallel bands like in the Holy Grail. This inquiry led to a type of whitish agate originally from the Jhagadia area in Gujarat (India). A picture of this material (

Figure 11c) reveals the presence of parallel bands with a whitish appearance, which can render red-brown tones after being dyed (

Figure 4b). Interestingly, the tone of these bands in

Figure 11c is quite similar to the appearance observed in the whitish discoloration of the Grail (

Figure 10a).

3.7. Irregularities in the Surface of the Gemstone

A visual inspection of the Holy Chalice also revealed other details of interest. Slight depressions can be observed at different points on the outer surface of the Grail [

24] (p. 166–167), ref. [

27] (p. 32), which supposedly originated during the carving and polishing process. Such irregularities are typical of a piece handcrafted with traditional techniques. Some of these imperfections seem to be marks of a trephine, an instrument used in ancient times to drill holes in rocks, which was the precursor of modern drills. The diameter of the trephine used to carve the Grail might be estimated from some of these marks.

In the front view, a translucent band with a porous appearance is observed both on the outer face (

Figure 12a) and inner face (

Figure 12b) of the Grail. This band acquires a whitish appearance when illuminated with transmitted light. It is a natural veining that reaches almost half the cup height, with a porous appearance conferred by the presence of larger quartz crystals [

23] (p. 32). A similar crystallization band is observed in a fragment of an onyx bowl with a grooved rim kept at the British Museum [

53].

Such distinct quartz crystallization in this part of the Grail is common in agate geodes. In fact, when the cavity of rock where agate is formed becomes practically covered by silica, the deposition of material from the outside is much slower, which favors a more perfect crystallization, giving rise to small visible crystals. This crystallization band in the Grail could be considered a slight aesthetic defect, though the band is translucent and does not clash too much. Nevertheless, if the lapidary craftsman who carved the Grail had intended to avoid this differentiated band, the cup size would have become smaller, reducing its volume and, therefore, its commercial value.

Regarding other details of interest on the surface, white quartz marks or spots can be observed in a lateral view of the Grail, as well as concentric bands around these marks (

Figure 13a). Such irregularities unfavorably impact the aesthetic appearance of the gemstone. However, this defect cannot be observed at all on the inside (

Figure 13b), which leads one to speculate that the inner volume was carved first. These whitish marks on the outer wall correspond to the limit of the raw agate from which the cup was carved [

26] (p. 96). Hence, the marks pertain to the irregularities of the wall of the cavity in the rock where the silica began to be deposited, gradually forming the agate stone.

The presence of these irregularities, together with the crystallization band, suggests that the cup was carved trying to achieve the largest possible size. This conclusion seems reasonable since a greater cup volume would lead to a higher price on the market. An internet search was carried out for Roman silver goblets, which showed an average diameter at the rim of about 11 cm. Only around 10% of them have a diameter lower than the case of the Holy Grail. Although further research is required to better estimate this percentage, this suggests that the Grail’s size is in a low percentile compared with the silver cups of the Roman period, which would justify the lapidary’s desire to maximize its diameter as much as possible when carving the gemstone.

A recent study speculates that perhaps the Grail’s owner had it carved to be used as a Jewish blessing cup for the Passover Dinner since its volume exceeds the minimum requirement for cups reserved for that ritual dinner [

13] (p. 238). However, this hypothesis is arguable because it is unknown what the Jewish blessing cups looked like at that time, given that Jewish art is characterized by aniconism. It seems more reasonable to assume that the Grail is a Hellenistic–Roman cup that a wealthy Jewish family purchased to be used as a ritual chalice. Moreover, the minimum volume established for Jewish ritual cups is also a matter of debate. According to rabbinic sources, each cup should contain at least one revi’ith of wine, but unfortunately, there is no consensus about this biblical measure of capacity, ranging from 73 to 160 mL according to different scholars [

54].

3.8. Archeological Evidence about the Location of the Cenacle

The Last Supper took place in a large two-story house with servants (Lk 22:10.12) that would have belonged to a wealthy family. Mark’s gospel insinuates that it was the house of a discreet disciple of Jesus (Mk 14:12–15). A literature review was carried out regarding archeological studies about the Cenacle in order to elucidate its exact location and to find evidence supporting the house belonging to a rich family. This review is presented next, starting with the oldest texts mentioning the Cenacle.

Epiphanius of Salamis (ca. 392 AD) narrates the journey of Emperor Hadrian to Jerusalem, which occurred in 130 AD:

He went up to Jerusalem, the famous and illustrious city which Titus, the son of Vespasian, overthrew in the second year of his reign. And he found the Temple of God trodden down and the whole city devastated, except for a few houses and the church of God, which was small, where the disciples, when they had returned after the Savior had ascended from the Mount of Olives, went to the upper room. For there it had been built, in that portion of Zion which escaped destruction, together with blocks of houses in the neighborhood of Zion and seven synagogues which alone remained standing [

55].

In Epiphanius’ time, this upper room to which the apostles returned after Jesus’ ascension was associated with the place where they lived in Jerusalem (Acts 1:13) and where the Last Supper took place. It was also considered the place where Jesus appeared to the apostles after his resurrection (Jn 20:19.26) and where the Holy Spirit descended on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:1–4) [

56] (p. 40). Nonetheless, some scholars speculate that it could be the home of James, a relative of Jesus (Gal 1:19; 2:9) whose house was a regular meeting place for Christians in Jerusalem (Acts 12:17; 21:18).

According to Epiphanius, this upper room was located on Mount Zion. This name refers to the ancient Jebusite fortress conquered by King David (2 Sam 5:7), considered equivalent to the “city of David” (1 Kings 8:1; 2 Chron 5:2). This fortress was located at the southern end of the eastern hill of Jerusalem (Ophel) between the Temple and the pool of Siloam [

57]. At the time of Jesus, this area of Jerusalem was called the Lower City, which was inhabited by merchants, artisans, and the lower classes. However, Christians began to refer to the western hill of Jerusalem as Zion, where the neighborhood known as the Upper City was located.

Epiphanius indicates that the whole city was destroyed in 70 AD except for the area of Mount Zion, where the Cenacle Church remained, standing “together with blocks of houses in the neighborhood of Zion and seven synagogues”. Those houses were probably built or rebuilt in the decades that followed, as the Jews returned a few years after the destruction of Jerusalem. This is attested to by Eutychius of Alexandria (10th century):

When the Christians, who had previously fled in the face of the Jews, had crossed the Jordan and settled in these areas, learned that Titus had destroyed the Holy City and killed the Jews, they returned to its ruins and settled there. They built a church and chose a second bishop by the name of Simon, son of Cleophas. […] This occurred in the fourth year of the reign of Vespasian [

56] (pp. 19–20).

Apparently, in the fourth year of Vespasian (73/74 AD), a group of Judeo-Christians who fled from Jerusalem returned and erected a small church on the ruins of the southern part of Mount Zion, which Epiphanius calls the “Church of God”. The place chosen was most likely the location of the house where the fundamental events of the Church’s birth took place: the Eucharist and Pentecost.

Hadrian decided to rebuild Jerusalem in 131 AD, but not the Temple, and renamed the city Aelia Capitolina. It was smaller than the original city, and new walls were built. Curiously, the old sanctuary of Mount Zion was left outside the walls, which preserved its location, and it remained accessible to the Christian community [

56] (pp. 26, 134, 191). Various authors such as Saint Jerome, Eucherius, Sophronius, and Cyril of Jerusalem mention the “Church of the Apostles where the Holy Spirit descended upon them” [

58] (pp. 84, 94, 158, 351–353).

In order to honor the location of this upper chamber, Christians built a large basilica between 379 and 381 AD called

Hagia Sion (Holy Zion), which was attached to the small Cenacle Church [

56] (p. 36). It became an important center of Christianity in Jerusalem, the “mother of all churches,” competing in importance with the Church of the Holy Sepulcher consecrated in 335 AD. Archeological studies suggest that the current Cenacle building was a Christian religious construction from its beginnings, which was a small adjacent structure separate from

Hagia Sion. This implies that this structure surely already existed when the great basilica was built [

56] (pp. 142, 150, 151, 191), probably the one described by Epiphanius.

Hagia Sion was damaged by the Persians in 614 AD [

58] (p. 353), but it was partially rebuilt years later. After its destruction by the Muslim caliph Al-Hakim in 1009, the crusaders erected here a church dedicated to the Virgin.

In short, although there is no certainty about the exact location of the Cenacle, it is very likely that it stood in the Upper City: the aristocratic neighborhood about 400 m away from Herod’s palace [

59]. These houses, which were distinguished by their grandeur and decoration, offered a fabulous view of the Temple.