Micro-Level Bicycle Infrastructure Design Elements: A Framework for Developing a Bikeability Index for Urban Areas

Abstract

Highlights

- This research introduced a new analytical bikeability index framework integrating micro-level indicators based on five internationally recognized bicycle infrastructure design principles: safety, comfort, attractiveness, directness, and coherence.

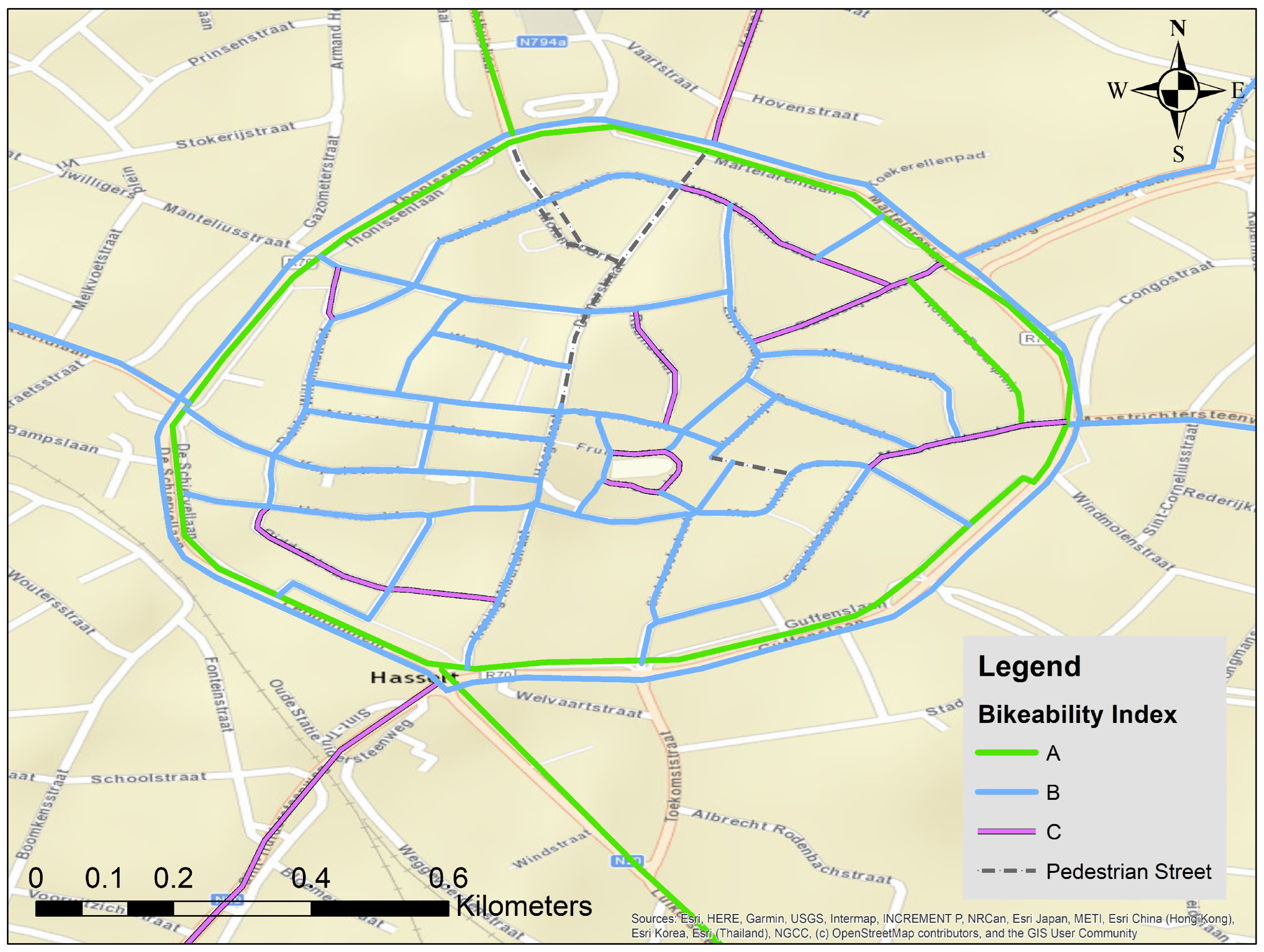

- The proposed framework was applied in Hasselt, Belgium, successfully identifying low and high-bikeable areas.

- The BI framework provides urban planners with a practical tool to identify low bikeability areas and suggests improvements in cycling infrastructure.

- This tool’s scalable and adaptable nature makes it relevant for cities committed to enhancing cycling environments and promoting a sustainable mode of transport by making cycling-friendly cities.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

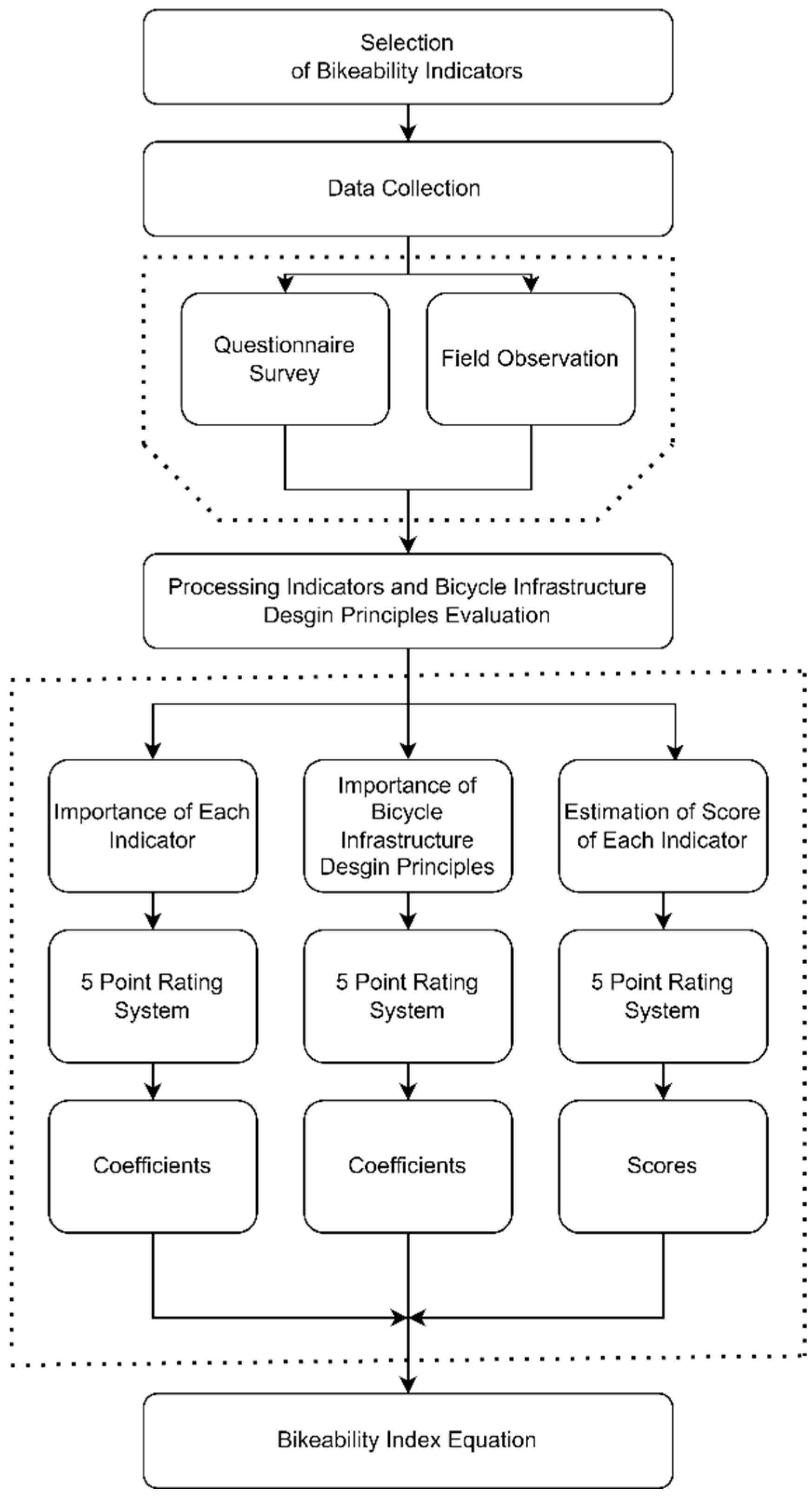

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Selection of Bikeability Indicators

3.2. Estimation of Weights of Selected Indicators

3.3. Measuring Scores of Indicators

3.4. BI Mathematical Definition

3.5. Bikeability Classification in Categories

4. Results

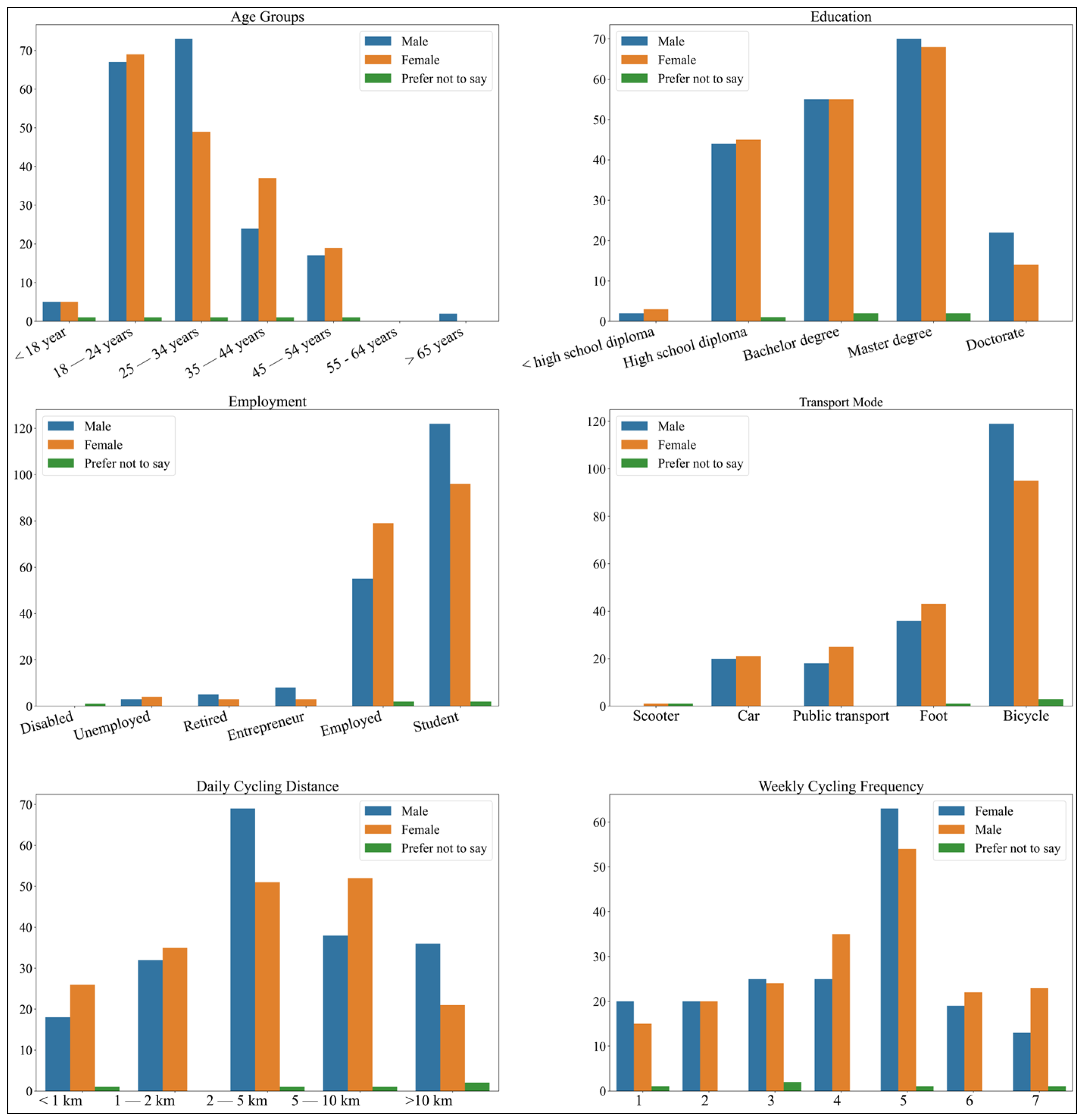

4.1. Summary Statistics

4.2. Coefficient and Scores of Bikeability Indicators

4.3. Bikeability Indicators Score

4.4. Bikeability of Streets and Lanes in Hasselt

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Participant Ratings of Sub-Indicators

Appendix B. Structure of the CFA Model

References

- Heinen, E.; van Wee, B.; Maat, K. Commuting by Bicycle: An Overview of the Literature. Transp. Rev. 2010, 30, 59–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, F.; Babaei, S.H.; Coppola, P. Improving Urban Cyclability and Perceived Bikeability: A Decision Support System for the City of Milan, Italy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.M.; Costa, D.G. Enhancing Cycling Safety in Smart Cities: A Data-Driven Embedded Risk Alert System. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 1992–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Shekari, Z.; Moeinaddini, M.; Zaly Shah, M. A Bicycle Safety Index for Evaluating Urban Street Facilities. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2015, 16, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañon, U.N.; Ribeiro, P.J.G.; Mendes, J.F.G. Evaluating Urban Bikeability: A Comprehensive Assessment of Póvoa de Varzim’s Network. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Pirdavani, A.; Wets, G.; Janssens, D. Bicycle Infrastructure Design Principles in Urban Bikeability Indices: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.; Costa, D.G.; Lima, L.; Silva, I. iBikeSafe: A Multi-Parameter System for Monitoring, Evaluation and Visualization of Cycling Paths in Smart Cities Targeted at Cycling Adverse Conditions. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 1058–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Planning for Cycling in a Growing Megacity: Exploring Planners’ Perceptions and Shared Values. Cities 2020, 106, 102857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Pirdavani, A.; Janssens, D.; Wets, G. Utilizing Intelligent Portable Bicycle Lights to Assess Urban Bicycle Infrastructure Surfaces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellana, J.; Saltarín, M.; Larrañaga, A.M.; González, V.I.; Henao, C.A. Developing an Urban Bikeability Index for Different Types of Cyclists as a Tool to Prioritise Bicycle Infrastructure Investments. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 139, 310–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucher, J.; Buehler, R. Making Cycling Irresistible: Lessons from the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. Transp. Rev. 2008, 28, 495–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Carstensen, T.A.; Nielsen, T.A.S.; Olafsson, A.S. Bicycle-Friendly Infrastructure Planning in Beijing and Copenhagen—Between Adapting Design Solutions and Learning Local Planning Cultures. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 68, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Urban Transport Transitions: Copenhagen, City of Cyclists. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 33, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, T.; Dill, J. Bicycle Commuting and Facilities in Major U.S. Cities: If You Build Them, Commuters Will Use Them. Transp. Res. Rec. 2003, 1828, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Milakis, D.; Athanasopoulos, K. What about People in Cycle Network Planning? Applying Participative Multicriteria GIS Analysis in the Case of the Athens Metropolitan Cycle Network. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 35, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellstedt, D.K.; Spengler, J.O.; Foster, M.; Lee, C.; Maddock, J.E. A Scoping Review of Bikeability Assessment Methods. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhs, C.D.; Clifton, K.J. Do Characteristics of Walkable Environments Support Bicycling? Toward a Definition of Bicycle-Supported Development. J. Transp. Land Use 2016, 9, 147–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, P.P.; Wong, Y.D. Influence of Infrastructural Compatibility Factors on Walking and Cycling Route Choices. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartanto, K. Developing a Bikeability Index to Enable the Assessment of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Nodes: Case Study in Arnhem-Nijmegen Region, Netherlands. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marqués, R.; Hernández-Herrador, V.; Calvo-Salazar, M.; García-Cebrián, J.A. How Infrastructure Can Promote Cycling in Cities: Lessons from Seville. Res. Transp. Econ. 2015, 53, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahabi, S.A.H.; Chang, A.; Miranda-Moreno, L.F.; Patterson, Z. Exploring the Link between the Neighborhood Typologies, Bicycle Infrastructure and Commuting Cycling over Time and the Potential Impact on Commuter GHG Emissions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 47, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, B.W.; Vattikuti, V.R.; Brannick, M.T. Real-Time Human Perceptions: Toward a Bicycle Level of Service. Transp. Res. Rec. 1997, 1578, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, M.; Callister, D.; Gresham, M.; Moore, B. Assessment of Communitywide Bikeability with Bicycle Level of Service. Transp. Res. Rec. 2012, 2314, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.K.; Kohl, H.W.; Pérez, A.; Reininger, B.; Pettee Gabriel, K.; Salvo, D. Bikeability: Assessing the Objectively Measured Environment in Relation to Recreation and Transportation Bicycling. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 861–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anciaes, P.R.; Jones, P. Estimating Preferences for Different Types of Pedestrian Crossing Facilities. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 52, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. Bicycle Safety Evaluation; Auburn University, City of Chattanooga, and Chattanooga-Hamilton County Regional Planning Commission: Chattanooga, TN, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Epperson, B. Evaluating Suitability of Roadways for Bicycle Use: Toward a Cycling Level-of-Service Standard. Transp. Res. Rec. 1994, 1438, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, W.J. Bicycle Test Route Evaluation for Urban Road Conditions. In Proceedings of the Transportation Congress, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–26 October 1995; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 1995. Volumes 1 and 2: Civil Engineers—Key to the World’s Infrastructure. pp. 1063–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, B.W. Bicycle Interaction Hazard Score: A Theoretical Model. Transp. Res. Rec. 1994, 1438, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Harkey, D.L.; Reinfurt, D.W.; Knuiman, M. Development of the Bicycle Compatibility Index. Transp. Res. Rec. 1998, 1636, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemzadeh, K.; Laureshyn, A.; Winslott Hiselius, L.; Ronchi, E. Expanding the Scope of the Bicycle Level-of-Service Concept: A Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforiadis, A.; Basbas, S.; Mikiki, F.; Oikonomou, A.; Polymeroudi, E. Pedestrians-Cyclists Shared Spaces Level of Service: Comparison of Methodologies and Critical Discussion. Sustainability 2021, 13, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petritsch, T.A.; Landis, B.W.; Huang, H.F.; McLeod, P.S.; Lamb, D.; Farah, W.; Guttenplan, M. Bicycle Level of Service for Arterials. Transp. Res. Rec. 2007, 2031, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.B. Bicycle and Pedestrian Level-of-Service Performance Measures and Standards for Congestion Management Systems. Transp. Res. Rec. 1996, 1538, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozer, D. Calculating Multi-Mode Levels-of-Service. Int. Bicycl. Fund 1994, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Asadi-Shekari, Z.; Moeinaddini, M.; Zaly Shah, M. Non-Motorised Level of Service: Addressing Challenges in Pedestrian and Bicycle Level of Service. Transp. Rev. 2013, 33, 166–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghih Imani, A.; Miller, E.J.; Saxe, S. Cycle Accessibility and Level of Traffic Stress: A Case Study of Toronto. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 80, 102496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijana, Đ.; Tomić, N.; Tešić, D. Walkability and Bikeability for Sustainable Spatial Planning in the City of Novi Sad (Serbia). Sustainability 2023, 15, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Lassaube, U.; Chabaud, D.; Moreno, C. Mapping the Implementation Practices of the 15-Minute City. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 2094–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliou, N.; Galanis, A.; Proios, A. Evaluation of the Bikeability of a Greek City: Case Study “City of Volos”. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2009, 5, 545–555. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlgren, L.; Schantz, P. Bikeability and Methodological Issues Using the Active Commuting Route Environment Scale (ACRES) in a Metropolitan Setting. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoedl, S.; Titze, S.; Oja, P. The Bikeability and Walkability Evaluation Table: Reliability and Application. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 457–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, M.; Teschke, K.; Brauer, M.; Fuller, D. Bike Score®: Associations between Urban Bikeability and Cycling Behavior in 24 Cities. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Wei, H. Bikeway Prioritization to Increase Bicycle Network Connectivity and Bicycle-Transit Connection: A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Approach. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 129, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D.; Winters, M. Income Inequalities in Bike Score and Bicycling to Work in Canada. J. Transp. Health 2017, 7, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Joh, K. Exploring the Synergistic Economic Benefit of Enhancing Neighbourhood Bikeability and Public Transit Accessibility Based on Real Estate Sale Transactions. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 3480–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Shekari, Z.; Moeinaddini, M.; Zaly Shah, M. A Pedestrian Level of Service Method for Evaluating and Promoting Walking Facilities on Campus Streets. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaabbasi, M.; Moeinaddini, M.; Zaly Shah, M.; Asadi-Shekari, Z. A New Assessment Model to Evaluate the Microscale Sidewalk Design Factors at the Neighbourhood Level. J. Transp. Health 2017, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labdaoui, K.; Mazouz, S.; Acidi, A.; Cools, M.; Moeinaddini, M.; Teller, J. Utilizing Thermal Comfort and Walking Facilities to Propose a Comfort Walkability Index (CWI) at the Neighbourhood Level. Build. Environ. 2021, 193, 107627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Shekari, Z.; Moeinaddini, M.; Aghaabbasi, M.; Cools, M.; Zaly Shah, M. Exploring Effective Micro-Level Items for Evaluating Inclusive Walking Facilities on Urban Streets (Applied in Johor Bahru, Malaysia). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 49, 101563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellana, J.; Saltarín, M.; Larrañaga, A.M.; Alvarez, V.; Henao, C.A. Urban Walkability Considering Pedestrians’ Perceptions of the Built Environment: A 10-Year Review and a Case Study in a Medium-Sized City in Latin America. Transp. Rev. 2020, 40, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, O.; Maciejewska, M.; Nadal, J.; Marquet, O. Built Environment Bikeability as a Predictor of Cycling Frequency: Lessons from Barcelona. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2022, 16, 100725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolemeas, C.; Vassi, A.; Tsigdinos, S.; Bakogiannis, D.E. Measure the Ability of Cities to Be Biked via Weighted Parameters, Using GIS Tools. the Case Study of Zografou in Greece. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardinghaus, M.; Nieland, S.; Lehne, M.; Weschke, J. More than Bike Lanes—A Multifactorial Index of Urban Bikeability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Biljecki, F. Assessing Bikeability with Street View Imagery and Computer Vision. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 132, 103371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Querg, J.; Keler, A.; Grigoropoulos, G. The Munich Bikeability Index: A Practical Approach for Measuring Urban Bikeability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.J.; Wei, Y.H. Assessing Area-Wide Bikeability: A Grey Analytic Network Process. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 113, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, P.; Han, Z.; Cao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y. Using Open Source Data to Measure Street Walkability and Bikeability in China: A Case of Four Cities. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.T.M.; Zhao, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Minet, L.; Nguyen, T.; Balasubramanian, R. Cyclists’ Personal Exposure to Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Its Influence on Bikeability. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 88, 102563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beura, S.K.; Chellapilla, H.; Bhuyan, P.K. Urban Road Segment Level of Service Based on Bicycle Users’ Perception under Mixed Traffic Conditions. J. Mod. Transp. 2017, 25, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Dadashova, B. Review of Contextual Elements Affecting Bicyclist Safety. J. Transp. Health 2021, 20, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-McDonnell, L.; de-la-Fuente-Aragon, M.V.; Ros-McDonnell, D.; Carboneras, M.C. Development of a Biking Index for Measuring Mediterranean Cities Mobility. Int. J. Prod. Manag. Eng. 2020, 8, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenn, P.J.; Oja, P.; Titze, S. Development of a Bikeability Index to Assess the Bicycle-Friendliness of Urban Environments. Open J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 05, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, M.A.; Karbowiński, Ł. Why the Riverside Is an Attractive Urban Corridor for Bicycle Transport and Recreation. Cities 2023, 143, 104611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañon, U.N.; Ribeiro, P.J.G. Bikeability and Emerging Phenomena in Cycling: Exploratory Analysis and Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadi, I.; Aganze, R.; Moeinaddini, M.; Asadi-Shekari, Z.; Cools, M. A Participatory Assessment of Perceived Neighbourhood Walkability in a Small Urban Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, L.; Saffo, D.; Vitek, O.; Dunne, C.; Borkin, M.A. Effective Use of Likert Scales in Visualization Evaluations: A Systematic Review. Comput. Graph. Forum 2022, 41, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labdaoui, K.; Mazouz, S.; Moeinaddini, M.; Cools, M.; Teller, J. The Street Walkability and Thermal Comfort Index (SWTCI): A New Assessment Tool Combining Street Design Measurements and Thermal Comfort. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysling, L.; Purves, R.S. Where to Improve Cycling Infrastructure? Assessing Bicycle Suitability and Bikeability with Open Data in the City of Paris. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2022, 15, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-80519-7. [Google Scholar]

- de Vet, H.C.W.; Mokkink, L.B.; Mosmuller, D.G.; Terwee, C.B. Spearman–Brown Prophecy Formula and Cronbach’s Alpha: Different Faces of Reliability and Opportunities for New Applications. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 85, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf Javid, M.; Ali, N.; Abdullah, M.; Campisi, T.; Shah, S.A.H. Travelers’ Adoption Behavior towards Electric Vehicles in Lahore, Pakistan: An Extension of Norm Activation Model (NAM) Theory. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 2021, 7189411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Some Contributions to Efficient Statistics in Structural Models: Specification and Estimation of Moment Structures. Psychometrika 1983, 48, 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.K.S.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Lagura, F.C.; Ramos, R.N.; Sigua, K.M.; Villas, J.A.; Nadlifatin, R.; Young, M.N.; Diaz, J.F.T. Determining Tricycle Service Quality and Satisfaction in the Philippine Urban Areas: A SERVQUAL Approach. Cities 2023, 137, 104339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellapilla, H.; Beura, S.K.; Bhuyan, P.K. Modeling Bicycle Activity on Multi-Lane Urban Road Segments in Indian Context and Prioritizing Bicycle Lane to Enhance the Operational Efficiency. In Proceedings of the 12th Transportation Planning and Implementation Methodologies for Developing Countries (TPMDC), Bombay, India, 19–21 December 2016; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, I.; Almoshaogeh, M.; Ahmed, T.; Moeinaddini, M.; Jamal, A.; Alharbi, F. An Empirical Framework to Quantify the Individual Traffic Congestion Cost for Private Motorized Vehicle Users. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241249801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizek, K.J.; Barnes, G.; Thompson, K. Analyzing the Effect of Bicycle Facilities on Commute Mode Share over Time. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2009, 135, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, A.; O’Holleran, C. Bicycle Infrastructure: Can Good Design Encourage Cycling? Urban Plan. Transp. Res. 2014, 2, 369–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkova, S.; Ettema, D.; Dijst, M. How Do Design Aspects Influence the Attractiveness of Cycling Streetscapes: Results of Virtual Reality Experiments in the Netherlands. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2022, 162, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardinghaus, M.; Papantoniou, P. Evaluating Cyclists’ Route Preferences with Respect to Infrastructure. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černá, A.; Černý, J.; Malucelli, F.; Nonato, M.; Polena, L.; Giovannini, A. Designing Optimal Routes for Cycle-Tourists. Transp. Res. Procedia 2014, 3, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Indicators | Notation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort | Presence of bicycle infrastructure | CMF01 | [24,52,53,54,55,56] |

| Pavement type | CMF02 | [10,23,55] | |

| Bike lane width | CMF03 | [10,23,55,57] | |

| Presence of sidewalk | CMF04 | [42,55,58] | |

| Grade | CMF05 | [10,53,55,59] | |

| Safety | Presence of bicycle infrastructure | SFT01 | [6,10] |

| Motorized traffic speed | SFT02 | [10,23,60,61] | |

| Traffic control devices | SFT03 | [51,55,56] | |

| Street lightening | SFT04 | [54,55,62] | |

| Car parking along the cycle path | SFT05 | [52,62] | |

| Attractiveness | Trees/green area and landscaping | ATR01 | [51,54,57,59,61,63,64] |

| Bicycle parking | ATR02 | [6,56,62,65] | |

| Directness and Coherence | Presence of cycle facilities at a traffic signal | DC01 | [54] |

| Road signage | DC02 | [24,55,62] | |

| Interruptions | DC03 | [51] |

| BI % Rating | Score | Description | Improvements Needed |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 81–100 | Extremely Bikeable | Very few improvements are needed |

| B | 61–80 | Bikeable | Few improvements are needed |

| C | 41–60 | Fairly Bikeable | Some improvements are needed |

| D | 21–40 | less Bikeable | Major improvements are needed |

| E | 0–20 | Not Bikeable | Extensive improvements are needed |

| Rotated Component Matrix | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | ||||

| Facilities | Comfort | Infrastructure | Traffic | |

| DC01 | 0.669 | |||

| ATR02 | 0.634 | |||

| SFT04 | 0.628 | |||

| SFT03 | 0.622 | |||

| DC02 | 0.619 | |||

| ATR01 | 0.490 | |||

| CMF04 | 0.742 | |||

| CMF05 | 0.648 | |||

| CMF03 | 0.609 | |||

| CMF02 | 0.603 | |||

| CMF01 | 0.787 | |||

| SFT01 | 0.705 | |||

| SFT05 | 0.753 | |||

| DC03 | 0.687 | |||

| SFT02 | 0.534 | |||

| CMIN | DF | p | CMIN/DF | RMR | GFI | AGFI | NFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA model | 194.259 | 79 | 0.000 | 1.977 | 0.047 | 0.95 | 0.923 | 0.864 | 0.902 | 0.926 | 0.051 |

| Criteria | Criteria Weights | Indicators | Weights of Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort | 0.86 | CMF01 | 0.595 |

| CMF02 | 0.646 | ||

| CMF03 | 0.653 | ||

| CMF04 | 0.598 | ||

| CMF05 | 0.302 | ||

| Safety | 1 | SFT01 | 0.753 |

| SFT02 | 0.640 | ||

| SFT03 | 0.561 | ||

| SFT04 | 0.471 | ||

| SFT05 | 0.423 | ||

| Attractiveness | 0.70 | ATR01 | 0.477 |

| ATR02 | 0.486 | ||

| Directness and Coherence | 0.76 | DC01 | 0.658 |

| DC02 | 0.555 | ||

| DC03 | 0.334 |

| Criteria | Indicators | Sub-Indicators | Scores |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort | CMF01 | Solitary bike path | 1.00 |

| Physically separated (by height or space) bicycle lane | 0.66 | ||

| Bicycle lane | 0.41 | ||

| Bicycle prioritized streets | 0.63 | ||

| Suggested bicycle paths | 0.14 | ||

| Bicycle paths shared with motorized traffic | 0.00 | ||

| CMF02 | Asphalt paved | 1.00 | |

| Concrete paved | 0.79 | ||

| Paving slabs | 0.42 | ||

| Cobblestones paved | 0.00 | ||

| CMF03 | Unidirectional wide (≥2 meters) | 1.00 | |

| Unidirectional narrow (<2 meters) | 0.40 | ||

| Double direction wide (≥3 meters) | 0.93 | ||

| Double direction narrow (<3 meters) | 0.00 | ||

| Shared | 0.30 | ||

| CMF04 | Buffered from cycle lane | 1.00 | |

| Adjacent to cycle lane | 0.48 | ||

| Shared with cyclist | 0.00 | ||

| CMF05 | Low (1–3%) | 1.00 | |

| Medium (3–6%) | 0.57 | ||

| High (>6%) | 0.00 | ||

| Safety | SFT01 | Solitary bike Path | 1.00 |

| Physically separated (by height or space) bicycle lane | 0.80 | ||

| Bicycle lane | 0.44 | ||

| Bicycle prioritized streets | 0.60 | ||

| Suggested bicycle paths | 0.21 | ||

| Bicycle paths shared with motorized traffic | 0.00 | ||

| SFT02 | Shared with motorized traffic | 0.91 | |

| Adjacent cycle paths next to a road with a speed limit of 30 km/h | 1.00 | ||

| Adjacent cycle paths next to a road with a speed limit of 50 km/h | 0.67 | ||

| Adjacent cycle paths next to a road with a speed limit of 70 km/h | 0.00 | ||

| SFT03 | Availability of traffic signals at intersections | 1.00 | |

| Non-availability of traffic signals | 0.00 | ||

| SFT04 | Good street Lighting (not exceeding 60 m apart from one another) | 1.00 | |

| Limited street lighting (the distances between the light poles are longer) | 0.38 | ||

| No street lighting | 0.00 | ||

| SFT05 | No car parking | 1.00 | |

| Car parking with a buffer area | 0.65 | ||

| Car parking without a buffer area | 0.00 | ||

| Attractiveness | ATR01 | Bicycle route/lane along trees and landscaping or water area | 1.00 |

| Bicycle route/lane without trees and landscaping or water area | 0.00 | ||

| ATR02 | Parking facilities at key destinations (e.g., shops, stations, etc.) | 1.00 | |

| No parking facilities at key destinations (e.g., shops, stations, etc.) | 0.00 | ||

| Directness and Coherence | DC01 | Presence of bicycle facilities at intersections | 1.00 |

| Partial presence of bicycle facilities at intersections | 0.88 | ||

| Non-presence of bicycle facilities at intersections | 0.00 | ||

| DC02 | Well signposted | 1.00 | |

| Partial signposted/signage missing at key location | 0.47 | ||

| No signage available | 0.00 | ||

| DC03 | 1 or no interruption | 1.00 | |

| 2 or more interruptions | 0.00 |

| Criteria | Criteria Weight (1) | Indicators (2) | Indicators Weight (3) | Score of Indicators (4) | Indicators Weighed Score (5) = (3) × (4) | BIMS (6) = (3) × 1 | BIW (7) = (1) × ∑(5) | BIMP (8) = (1) × ∑(6) | BI% = ∑(7)/∑(8) × 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort | 0.86 | CMF01 | 0.595 | 1.00 | 0.595 | 0.595 | 1.849 | 2.403 | 86.26 |

| CMF02 | 0.646 | 1.00 | 0.646 | 0.646 | |||||

| CMF03 | 0.653 | 0.93 | 0.607 | 0.653 | |||||

| CMF04 | 0.598 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.598 | |||||

| CMF05 | 0.302 | 1.00 | 0.302 | 0.302 | |||||

| Safety | 1 | SFT01 | 0.753 | 1.00 | 0.753 | 0.753 | 2.848 | 2.848 | |

| SFT02 | 0.640 | 1.00 | 0.640 | 0.640 | |||||

| SFT03 | 0.561 | 1.00 | 0.561 | 0.561 | |||||

| SFT04 | 0.471 | 1.00 | 0.471 | 0.471 | |||||

| SFT05 | 0.423 | 1.00 | 0.423 | 0.423 | |||||

| Attractiveness | 0.7 | ATR01 | 0.477 | 1.00 | 0.477 | 0.477 | 0.674 | 0.674 | |

| ATR02 | 0.486 | 1.00 | 0.486 | 0.486 | |||||

| Directness and Coherence | 0.76 | DC01 | 0.658 | 1.00 | 0.658 | 0.658 | 0.754 | 1.176 | |

| DC02 | 0.555 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.555 | |||||

| DC03 | 0.334 | 1.00 | 0.334 | 0.334 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, T.; Pirdavani, A.; Wets, G.; Janssens, D. Micro-Level Bicycle Infrastructure Design Elements: A Framework for Developing a Bikeability Index for Urban Areas. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8020046

Ahmed T, Pirdavani A, Wets G, Janssens D. Micro-Level Bicycle Infrastructure Design Elements: A Framework for Developing a Bikeability Index for Urban Areas. Smart Cities. 2025; 8(2):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8020046

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Tufail, Ali Pirdavani, Geert Wets, and Davy Janssens. 2025. "Micro-Level Bicycle Infrastructure Design Elements: A Framework for Developing a Bikeability Index for Urban Areas" Smart Cities 8, no. 2: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8020046

APA StyleAhmed, T., Pirdavani, A., Wets, G., & Janssens, D. (2025). Micro-Level Bicycle Infrastructure Design Elements: A Framework for Developing a Bikeability Index for Urban Areas. Smart Cities, 8(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8020046