Degree of Polarization of Cathodoluminescence from a GaAs Facet in the Vicinity of an SiN Stripe

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. DOP as a Function of Strain

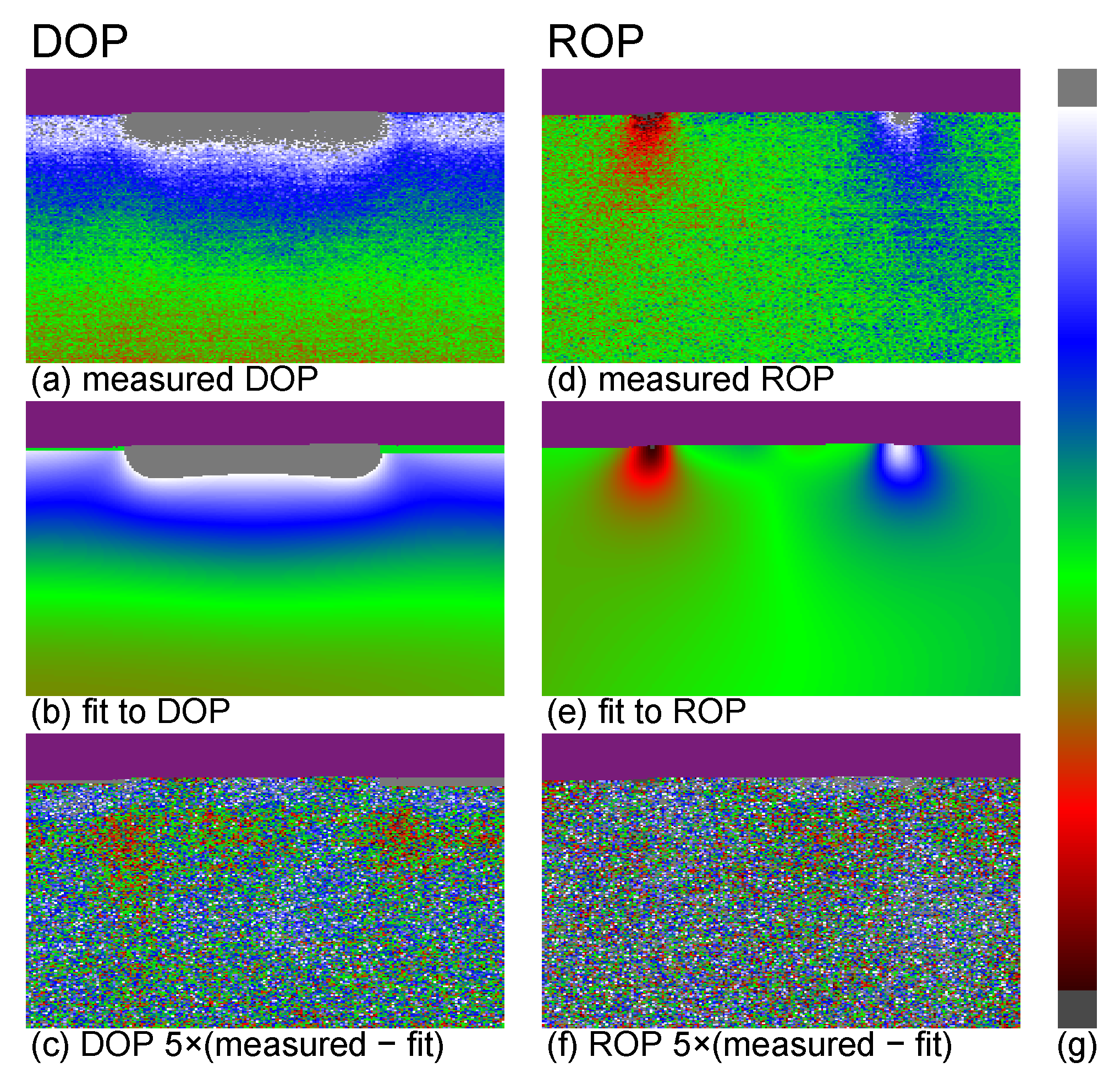

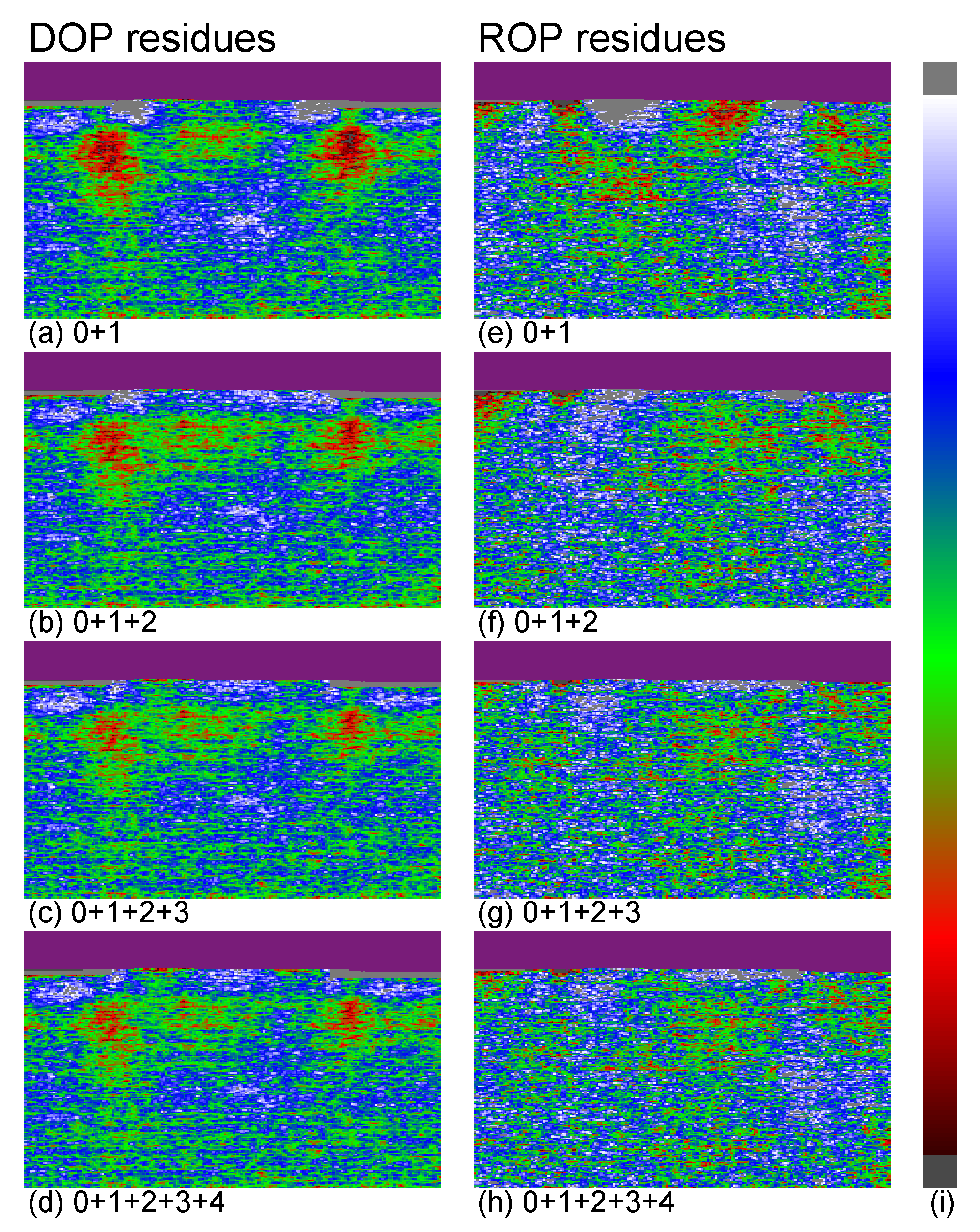

1.2. Least Squares Fits

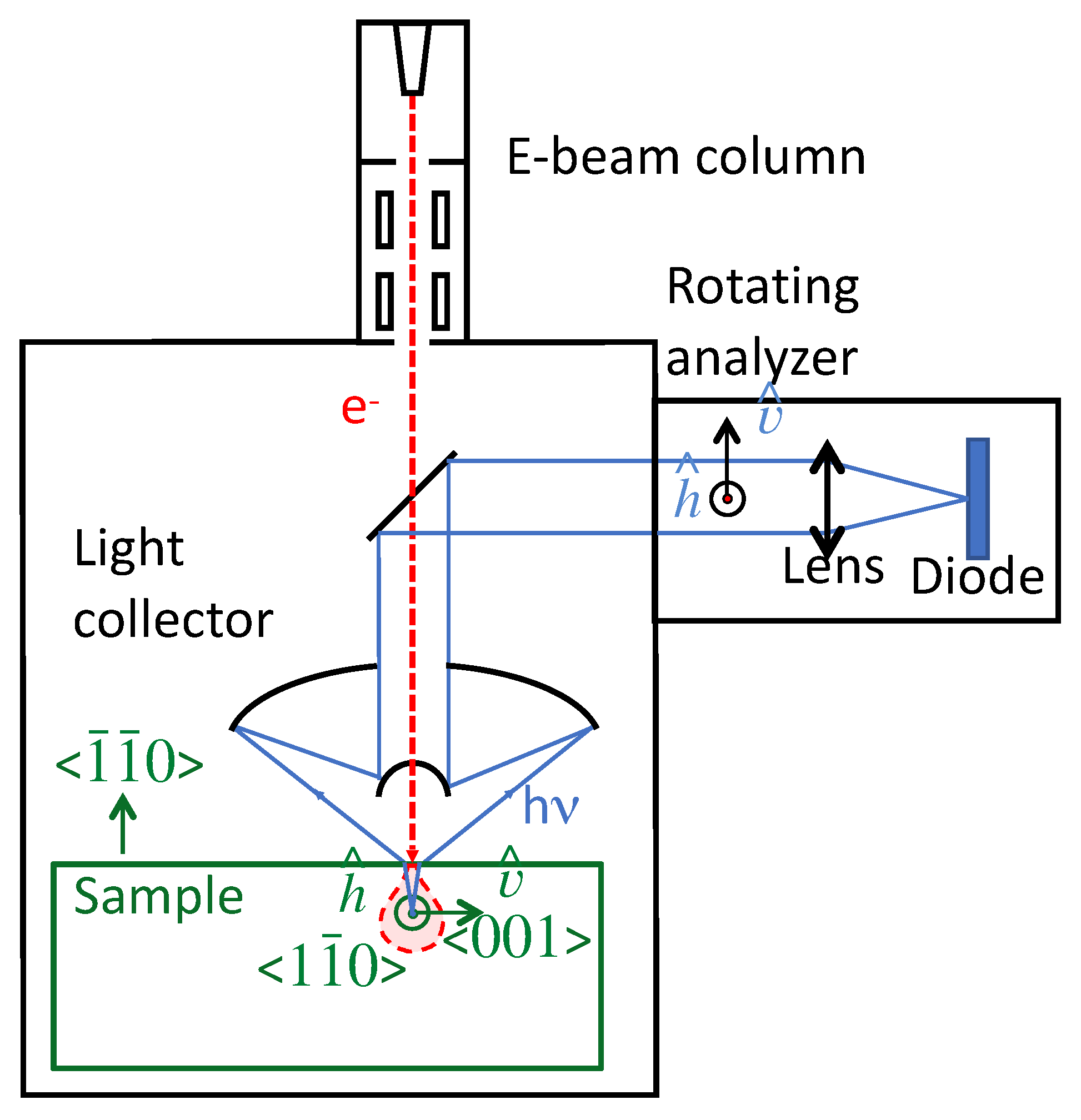

2. Sample and SEM Measurements

2.1. SiN Stripes on GaAs

2.2. SEM Data

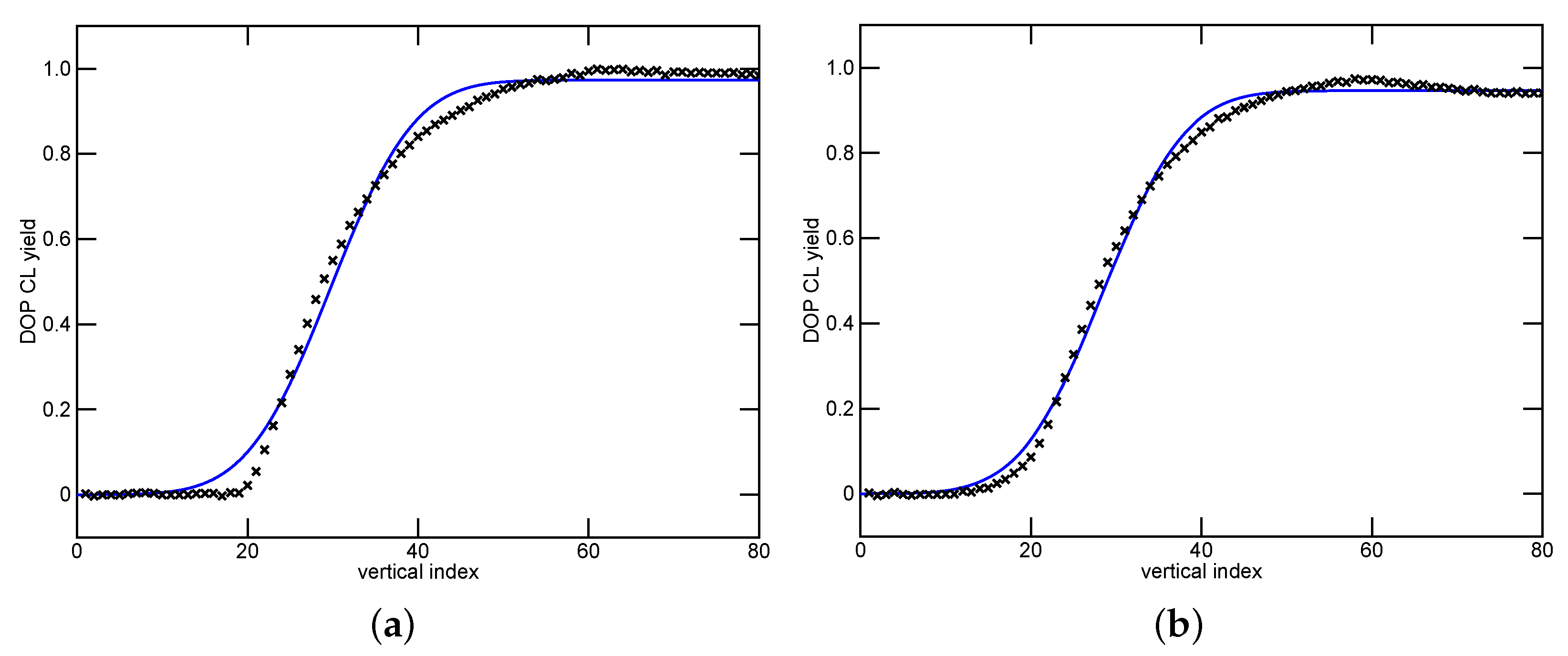

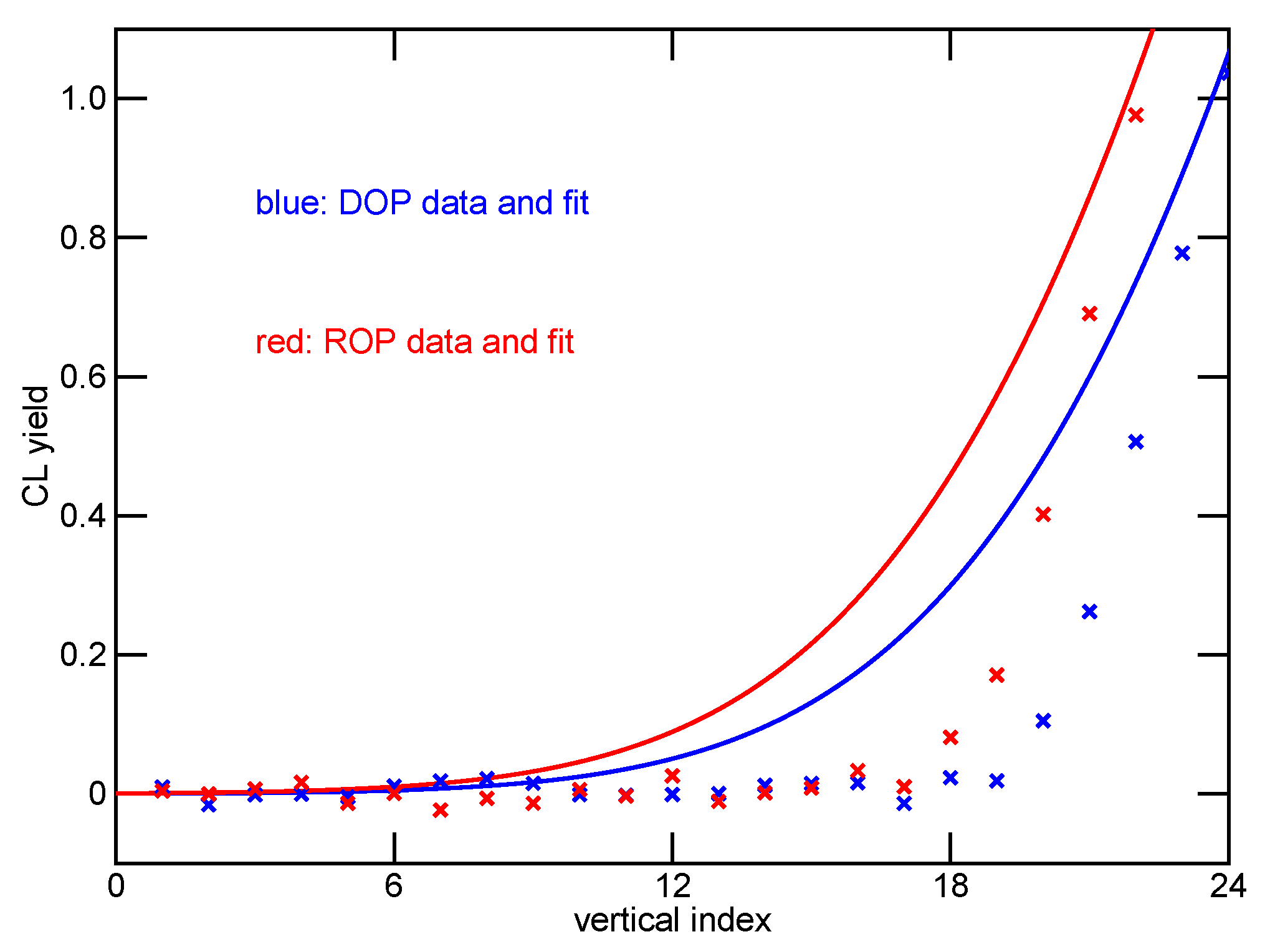

3. Fits to the CL Yield

4. Fits of FEM Simulations to the DOP and ROP Data

4.1. Some Details on the FEM Simulations

4.2. Fits to the Data

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knapp, E.; Battaglia, M.; Jenatsch, S.; Ruhstaller, B. Machine learning assisted material and device parameter extraction from measurements of thin film semiconductor devices. In Proceedings of the Numerical Simulation of Optoelectronic Devices. International Conference NUSOD, Turin, Italy, 12–16 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hildenstein, P.; Feise, D.; Ostermay, I.; Paschke, K.; Traenkle, G. Precise prediction of optical behaviour of mechanically stressed edge emitting GaAs devices. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2022, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, A.; Coriasso, C.; Codato, S.; Paoletti, R. Degree of polarization of high-power laser diodes: Modeling and statistical experimental investigation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3253–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Chang, Y.H.; Zhao, Y.C.; Khan, Z.; Ahmad, Z.; Hung Lee, C.; Chang, J.S.; Liu, C.Y.; Shi, J.W. Low-noise, single-polarized, and high-speed vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers for very short reach data communication. J. Lightwave Technol. 2022, 40, 3845–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.H.; Zhou, S. Bonding stress and reliability of low-polarization quantum-well superluminescent diode. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostructures 2019, 109, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammou, B.; Abdelal, A.; Landesman, J.P.; Levallois, C.; Mascher, P. Strain engineering in III-V photonic components through structuration of SiNx films. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2022, 40, 012202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Fu, T.; Qi, A.; Qu, H.; Xing, X.; Zheng, W. High peak power density and low mechanical stress photonic-band-crystal diode laser array based on non-soldered packaging technology. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2022, 20, 07403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, P.; Ma, C.; Sheng, X. Study on die-bonding of single emitter high power laser diodes. Opt. Eng. 2022, 61, 036101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, B.; Yang, G.; Li, T.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Bai, S. Influence of strain on performance of independent emitters in high power quasi-continuous semiconductor laser array. Acta Photon. Sin. 2020, 49, 0914001. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Choi, W.J.; Kim, K.; Kim, D. Nondestructive evaluation of detuned wavelength for as-grown VCSEL epi-wafer. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2022, 34, 1246–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbourne, P.D.; Cassidy, D.T. Observation of dislocation stresses in InP using polarization-resolved photoluminescence. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1992, 61, 1174–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbourne, P.D.; Cassidy, D.T. Imaging of stresses in GaAs diode lasers using polarization resolved photoluminescence. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1993, 29, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, D.T.; Lam, S.K.K.; Lakshmi, B.; Bruce, D.M. Strain mapping by measurement of the degree of photoluminescence. Appl. Opt. 2004, 43, 1811–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coenen, T.; Haegel, N.M. Cathodoluminescence for the 21st century: Learning more from light. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2017, 4, 031103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouchier, M.; Rochat, N.; Pargon, E.; Landesman, J.P. Polarized cathodoluminescence for strain measurement. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2019, 90, 043701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, D.T.; Landesman, J.P. Degree of polarization of luminescence from GaAs and InP as a function of strain: A theoretical investigation. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 5506–5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahder, T.B. Analytic disperson relations near the Γ point in strained zinc-blende crystals. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahder, T.B. Eight-band k · p model of strained zinc-blende crystals. Phys. Rev. B 1990, 41, 11992–12001, Erratum in Phys. Rev. B 1992, 46, 9913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkby, P.A.; Selway, P.R.; Westbrook, L.D. Photoelastic waveguides and their effect on stripe-geometry GaAs/Ga1-xAlxAs lasers. J. Appl. Phys. 1979, 50, 4567–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, D.T.; Adams, C.S. Polarization of the output of InGaAsP semiconductor diode lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1989, 24, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbourne, P.D. Measurement of Stress in III–V Semiconductors using the Degree of Polarization of Luminescence. Ph.D. Thesis, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Colbourne, P.D.; Cassidy, D.T. Dislocation detection using polarization-resolved photoluminescence. Can. J. Phys. 1992, 70, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurgaftman, I.; Meyer, J.R.; Ram-Mohan, L.R. Band parameters for III–V compound semiconductors and their alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 89, 5815–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, J.F. Physical Properties of Crystals; Oxford Unversity Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, D.T.; Lam, S.K.K. Degree of polarization of luminescence from facets of InP as a function of strain: Some experimental evidence. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, 4502–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PDE Solutions, Inc. FlexPDE 7, Version 7.17; PDE Solutions, Inc.: Spokane, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Attolight Webpage. Available online: https://attolight.com (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Lascos, S.J.; Cassidy, D.T. Optical phase and intensity modulation from a rotating optical flat: Effect on noise in degree of polarization measurements. Appl. Opt. 2009, 48, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Technical Notes. 2022. Available online: https://www.pdesolutions.com/help/coordinatescaling.html (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Dunstan, D.J. Stiffness of GaAs. In Properties of Gallium Arsenide, 3rd ed.; Brozel, M.R., Stillman, G.E., Eds.; Inspec: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Landesman, J.P.; Cassidy, D.T.; Tomm, J.W.; Biermann, M.L. Strain measurement. In Quantum-Well Laser Array Packaging: Nanoscale Packaging Techniques; Tomm, J.W., Jiménez, J., Eds.; McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bevington, P.R.; Robinson, D.K. Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| File | h | A | (nm) | (nm) | FWHM (nm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 464 | 20,817.0 | 747 | 201 | 473 | ||

| 98 | 630 | 19,465.2 | 785 | 203 | 477 | ||

| 102 | 630 | 19,463.4 | 782 | 203 | 478 | ||

| 106 | 673 | 19,452.2 | 748 | 205 | 482 | ||

| 190 | 480 | 20,990.3 | 766 | 204 | 480 | ||

| 18 | 464 | 21,549.1 | 705 | 204 | 481 | ||

| 98 | 664 | 20,073.7 | 740 | 203 | 479 | ||

| 102 | 659 | 20,087.5 | 737 | 203 | 478 | ||

| 106 | 705 | 20,268.2 | 706 | 207 | 487 | ||

| 192 | 461 | 21,603.6 | 727 | 206 | 486 |

| Elements | Influence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: biaxial SiN stress | |||||

| 2: uniaxial stress | |||||

| 3: biaxial interface stress | |||||

| 4: biaxial etch stress | |||||

| 0 | 0: background only |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cassidy, D.T.; Landesman, J.-P.; Mokhtari, M.; Pagnod-Rossiaux, P.; Fouchier, M.; Monachon, C. Degree of Polarization of Cathodoluminescence from a GaAs Facet in the Vicinity of an SiN Stripe. Optics 2023, 4, 272-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt4020019

Cassidy DT, Landesman J-P, Mokhtari M, Pagnod-Rossiaux P, Fouchier M, Monachon C. Degree of Polarization of Cathodoluminescence from a GaAs Facet in the Vicinity of an SiN Stripe. Optics. 2023; 4(2):272-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt4020019

Chicago/Turabian StyleCassidy, Daniel T., Jean-Pierre Landesman, Merwan Mokhtari, Philippe Pagnod-Rossiaux, Marc Fouchier, and Christian Monachon. 2023. "Degree of Polarization of Cathodoluminescence from a GaAs Facet in the Vicinity of an SiN Stripe" Optics 4, no. 2: 272-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt4020019

APA StyleCassidy, D. T., Landesman, J.-P., Mokhtari, M., Pagnod-Rossiaux, P., Fouchier, M., & Monachon, C. (2023). Degree of Polarization of Cathodoluminescence from a GaAs Facet in the Vicinity of an SiN Stripe. Optics, 4(2), 272-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/opt4020019