Abstract

Automation and control systems are constantly evolving, using artificial intelligence techniques to implement new forms of control, such as fuzzy control, with advantages over classic control strategies, especially in non-linear systems. Water supply networks are complex systems with different operating configurations, uninterrupted operation requirements, equalization capacity and pressure control in the supply networks, and high reliability. In this sense, this work aims to develop a fuzzy pressure control system for a supply system with three possible operating configurations: a single motor pump, two motor pumps in series, or two motor pumps in parallel. For each configuration, an energy efficiency analysis was carried out according to the demand profile established in this case study. In order to validate the proposed methodology, an experimental water supply system was used, located in the Laboratory of Energy Efficiency and Hydraulics in Sanitation at the Federal University of Paraiba (LENHS/UFPB).

1. Introduction

Water is a fundamental resource for humans and other living things, and its conscious use should be preserved in relation to its importance. A major problem with water waste lies in excessive use of water for baths and showers, as well as open-air toilets. The problem is exacerbated by waste in supply systems such as pipes that leak. To address this problem, efficient methods of delivering water must be developed so that it reaches the intended location.

Global water loss averages 35%, or 48.6 billion cubic meters per year. This is due to water leakage during distribution from the basin to the end user. Leakage must be treated if the pressure on water resources is to be reduced because it causes significant waste. Awareness and conservation campaigns in living areas, on the other hand, are insignificant because the amount of water conserved through the allocation of indoor water use is not as important as the amount of conserved water released from water distribution systems [1].

Some solutions for attempting to deal with excess pressure in pipes, lines, and other installations include: Pump rotation is controlled by a frequency inverter and pressure-reducing valves. Pressure in water distribution networks can be controlled using frequency inverters (WDN). Pressure control is advantageous because it extends the useful life of pipes and accessories, improves system reliability, reduces hydraulic transients, and saves electrical energy. Pressure control is required for a supply system to perform satisfactorily in terms of both technical and economic performance. Pressure uniformity throughout the distribution network can reduce the frequency of ruptures, excessive water consumption caused by pressure, and volume lost due to leaks [2].

Another alternative is the installation of pressure-reducing valves (VRP). The pressure at the PRV outlet can be adjusted depending on the maximum pressure losses within the WDN and the minimum pressure required at each node. However, such control tends to be ineffective because of the constant fluctuations of the inflow and hence pressure losses within the WDN. Since the pressure at the PRV outlet is set according to the maximum pressure drop, the pressure at the critical node will be higher than required for most of the day, especially during the night hours when the inflow and consequently the pressure drop [3,4].

Several techniques based on artificial intelligence can be used to promote the pressure control in water system supply [5]. Thus, among the benefits of pressure control in water supply networks are the following: (a) Increasing the useful life of pipes and accessories, (b) increasing system reliability, (c) reducing hydraulic transients, and (d) reducing waste of electrical energy.

In this paper, we propose an energy efficiency analysis based on fuzzy logic from the implementation of pressure control of a water supply system to improve the operational performance of water pumping systems. The main contribution is an analysis of energy efficiency from pressure control of different pump operation configurations in water supply systems.

Complementary, the authors identify three main contributions of this work compared with related works:

- (i)

- Development of single-input multiple-output (SIMO);

- (ii)

- Evaluate the robustness of the controller when the supply system is subjected to variable demand;

- (iii)

- Compare the energy efficiency of a multi-pump pressure control system with different operating configurations (single pump, two pumps in series, and two pumps in parallel).

In order to validate the proposed methodology, an experimental water supply system was used, located in the Laboratory of Energy Efficiency and Hydraulics in Sanitation at the Federal University of Paraiba (LENHS/UFPB).

2. Related Works

In this section, a review of the main scientific works was carried out, highlighting relevant research that contributed to the construction of the methodology proposed in this article.

In [5], artificial intelligence techniques were used for efficient pressure control using plant modeling based on artificial neural networks and a fuzzy control system. This case study was implemented in a water supply network in Brazil, resulting in pressure control during night hours when pipes ruptured due to excess pressure in the supply network. In this way, it was possible to validate the practical application of artificial intelligence techniques in actual problems of the water supply system.

An optimal process for a photovoltaic water pumping system (PWPS) based on an induction machine and driving a centrifugal pump is investigated in [6]. The photovoltaic (PV) system was studied using conventional direct torque control (DTC), which includes a hysteresis controller; however, fuzzy logic control has been proposed to improve the efficiency of PV systems. Fuzzy logic control (FLC) performance on an induction motor has been tested and compared to conventional DTC. The simulation results show an increase in both the daily pumped quantity and a reduction in torque, stator current, and flux ripples as a result of FLC’s use of a comparator with hysteresis.

In [7], the level is controlled in a single tank using two types of controllers: PID and fuzzy. Fuzzy logic controllers provide improved performance and stability. The results show that the fuzzy logic controller outperforms the PID controller in terms of no overshoot, faster settling time, better set point tracking, and lower performances, such as integral of time and absolute error (ITAE), integral of time and squared error (ITSE), integral absolute error (IAE), and integral squared error (ISE).

In [8], a control system with a multilayer feedforward architecture based on an artificial neural network (ANN) was proposed for the operation of a water supply system with parallel pumps and electric motors driven by a frequency converter. In all experiments, the settling time was less than 30 s, and the maximum relative steady-state error was 2.9 percent. Furthermore, the generalization capacity of the ANN algorithm enabled an increase in hydraulic efficiency, energy savings, and equipment life.

In [9], the authors compared a fuzzy-PID controller and a conventional PID applied to a pumping system, which contains four pumps. The results presented showed that the fuzzy-PID controller showed better performance in its transient and permanent feature, with less dead-band time, rise time, and stabilization.

The authors of [10] implement artificial intelligence techniques in the implementation of a feedback system for indirect flow measurement. Among the contributions of this new technique are the design of the pressure controller using fuzzy logic theory, which eliminates the need to know the plant model, and the use of an artificial neural network to construct nonlinear models with the goal of indirectly estimating the flow.

The development of a proportional integral (PI) controller was carried out in [11], with the goal of increasing the energy efficiency and reliability of water pumping units with cascade pumps. The dynamic error for two cascade pumps was less than 3%, resulting in a 30% reduction in energy losses per day. In contrast, ref. [12] evaluates the operation of three pumping system settings: serial, parallel, and single pump, which proved stable in pressure control and the most efficient parallel operation.

A neuro-fuzzy system is another method for controlling pressure in water distribution systems. The technique controlled the rotation speed of the pumping system, primarily to increase energy efficiency. When compared to the other controllers, the neuro-fuzzy controller (NFC) demonstrated a significant increase in pumping system efficiency and a reduction in specific energy consumption of up to 79.7%. Under severe demand variation, target pressures were kept close to setpoint with low hydraulic transients and maintained satisfactory stability (error 8%). It is concluded that the NFC produced superior results when compared to the other controllers studied [13].

Several current control strategies are being developed, according to the literature review. However, most of the research cited above does not take into account the pump operating point for different operating topologies, but only analyzes the control stability and energy saving for a single pump. To address this limitation, this study proposes a fuzzy control to regulate the pressure in a water pumping system, seeking to compare the energy efficiency with different topologies of pump operation: single, two in series, and two in parallel—in addition to evaluating its robustness to variable consumption.

3. Proposed System

3.1. Experimental System

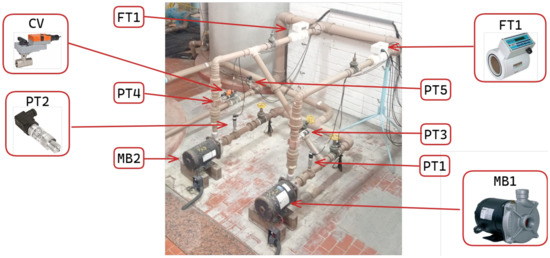

A water system helps meet the needs of the population by providing drinking water at the right amount and pressure. A control and automation strategy must be used to effectively manage and operate this type of system. In this work, an experimental system was used to emulate a water supply system with uncertain demand, as shown in Figure 1. This experimental system is located placed at the Energy Efficiency and Sanitation Laboratory (LENHS) at the Federal University of Paraiba (UFPB) in João Pessoa, Brazil.

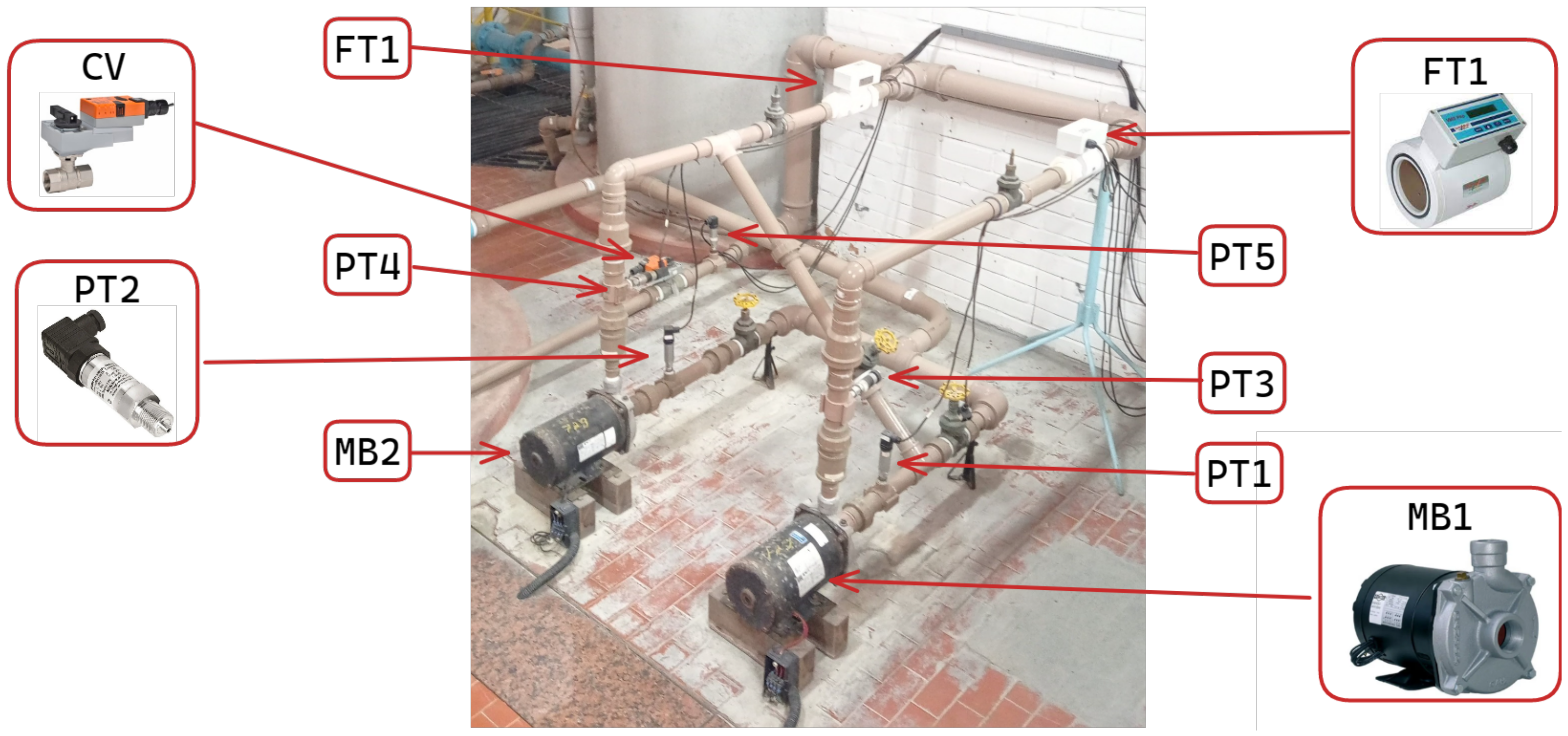

Figure 1.

Experimental setup.

Water from the reservoir is pumped by two centrifugal pumps (three-phase 220/380 V 3 hp) through Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) pipes and connections in the experimental system. The system supplies energy to the liquid in the form of pressure and flow, which are measured with pressure (PT) and flow (FT) transducers with maximum measurement limits of 42.21 mH2O and 11.34 L/s, respectively.

A frequency converter controls the rotation speed of the pump. Furthermore, at the system’s outlet is an automated proportional valve (VRP CV-1) that simulates variable water demand by regulating the cross-sectional area through which the water flows through the pipe.

The voltage from sensors are then converted to a digital signal by a data acquisition system (DAQ) model NI-USB 6229 with a sampling frequency of 10 Samples/s. The control algorithm was then applied, and an actuation signal was generated and sent from the PC to the frequency inverter via DAQ.

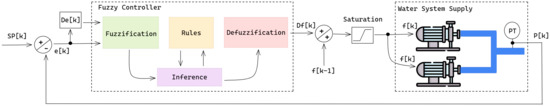

3.2. Controller Implementation

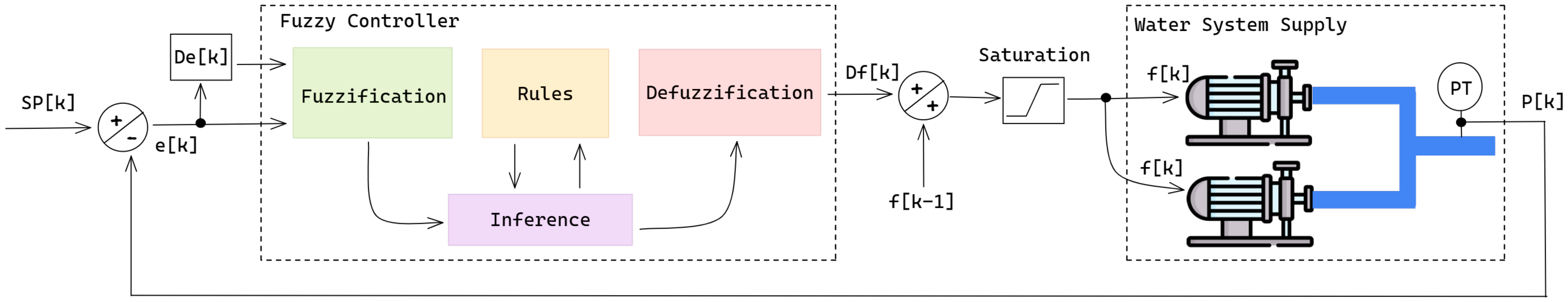

The structure of the fuzzy controller is depicted in Figure 2, whose goal is to generate control actions to modify the value of the dynamic pressure response at the system output. The control is of the SIMO (single-input multiple-output) type, with P representing the control variable (pressure). The current error is represented by , which is the reference pressure value. ; is the error variation given by ; is the actuation signal increment or decrement (speed of rotation of the pump set). The last value of the frequency used for actuation is , and the updated value of the frequency of the inverter, which is used as an actuation variable on the motor pump, is . A saturator was used in this diagram to prevent the motor pump from operating outside of its operating range.

Figure 2.

Fuzzy pressure control system.

The structure of the fuzzy controller proposed is illustrated in Figure 2, whose goal is to generate control actions to modify the value of the dynamic pressure response at the system output. The control is of the SIMO (single-input multiple-output) incremental type, with P representing the control variable (pressure) and representing the reference pressure value and the current error. ; is the error variation given by ; is the actuation signal increment (speed of rotation of the pump set); is the last value of the frequency used for actuation; and is the updated value of the inverter frequency, which is used as an actuation variable on the motor-pump.

The proposed control aims to maintain stable the pressure at the outlet of the system, represented by the PT-5 sensor in Figure 1. In this system, it is also possible to emulate the variation of the water demand by regulating the opening angle of the control Valve at the outlet of the system.

3.2.1. Range of the Variables

To implement the proposed fuzzy controller is the fuzzification of the input variables. The ranges of the controller variables are pressure, pressure error, pressure error variation, and frequency variation.

The limits for the variable membership function were determined by evaluating the system’s response after starting the pump at rated speed (60 Hz), which revealed that the maximum pressure obtained is 18 mH2O and the greatest variation in the error is 4 mH2O. These values are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ranges related to each variable.

3.2.2. Fuzzification

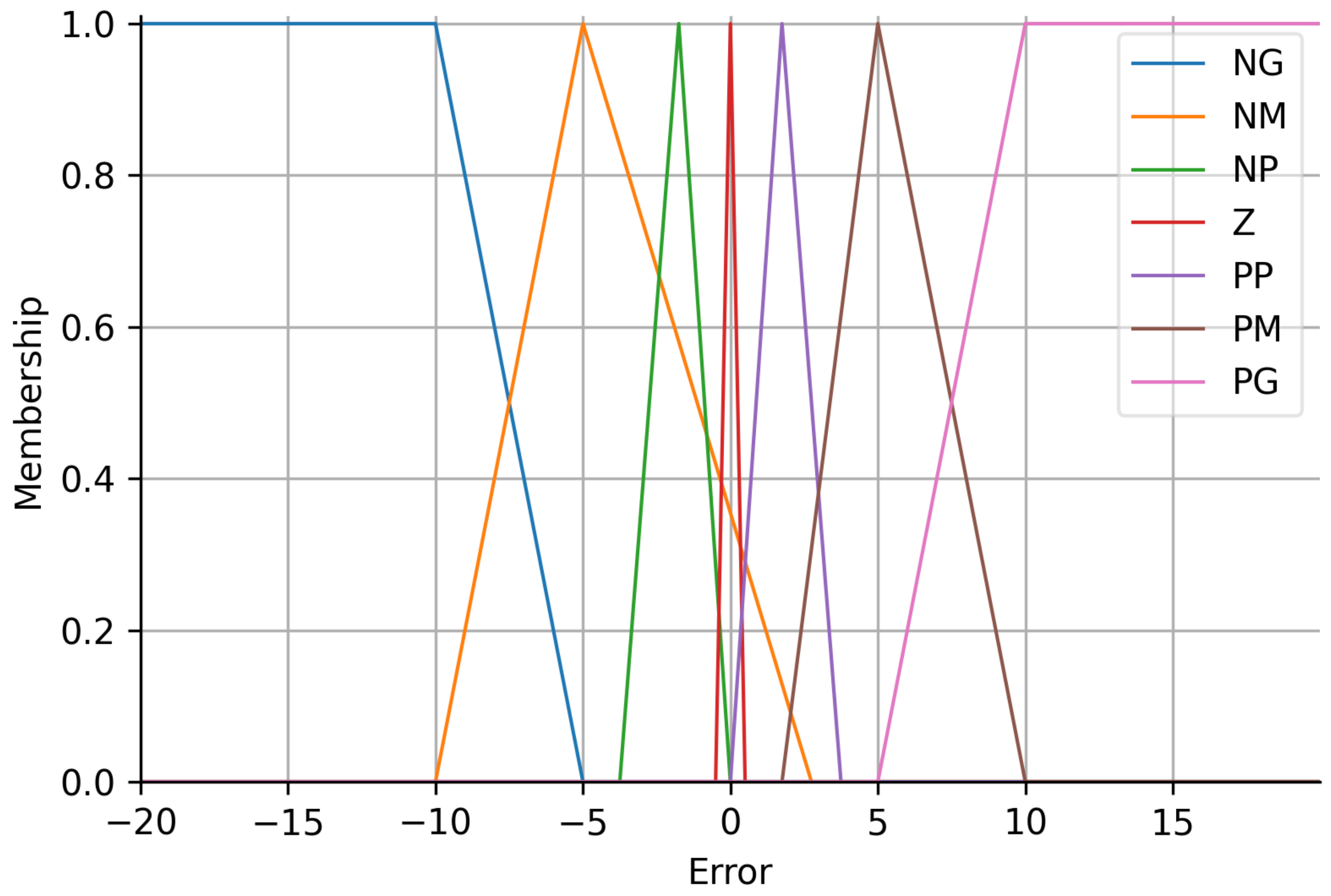

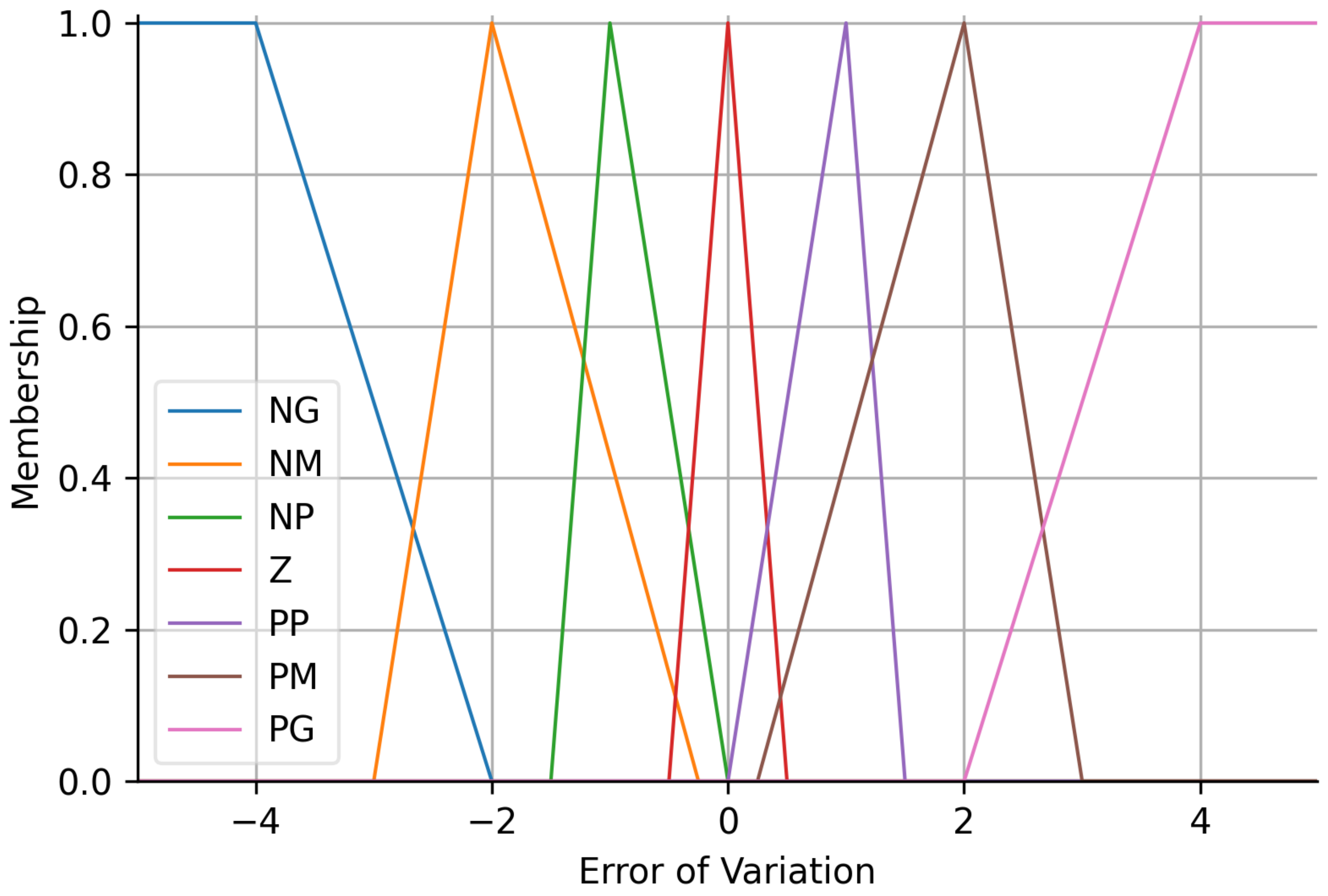

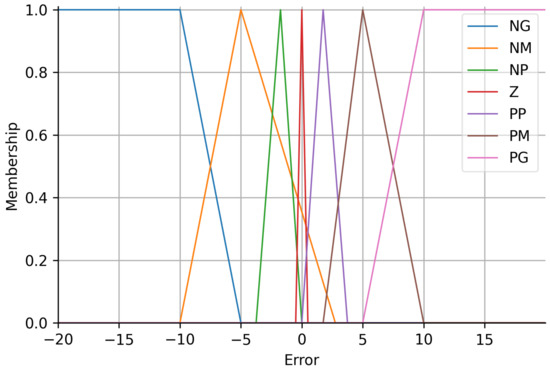

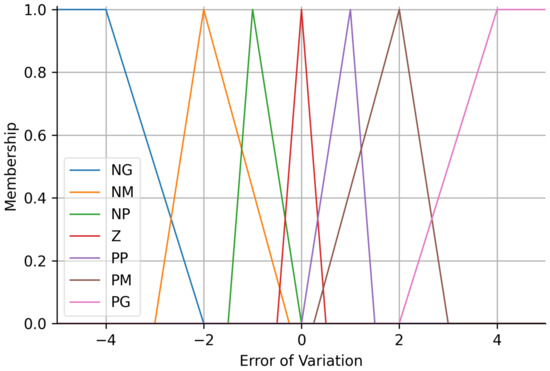

The membership functions of the controller input variables are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. The input linguistic variables could have seven different values: negative big (NB), negative medium (NM), negative small (NS), zero (Z), positive small (PS), positive medium (PM), and positive big (PB). Numerical boundaries for each category were defined considering prior knowledge of platform behavior, and the membership functions chosen were triangular and trapezoidal.

Figure 3.

Membership function of the error of variation input variables (input variables).

Figure 4.

Membership function of the error (input variables).

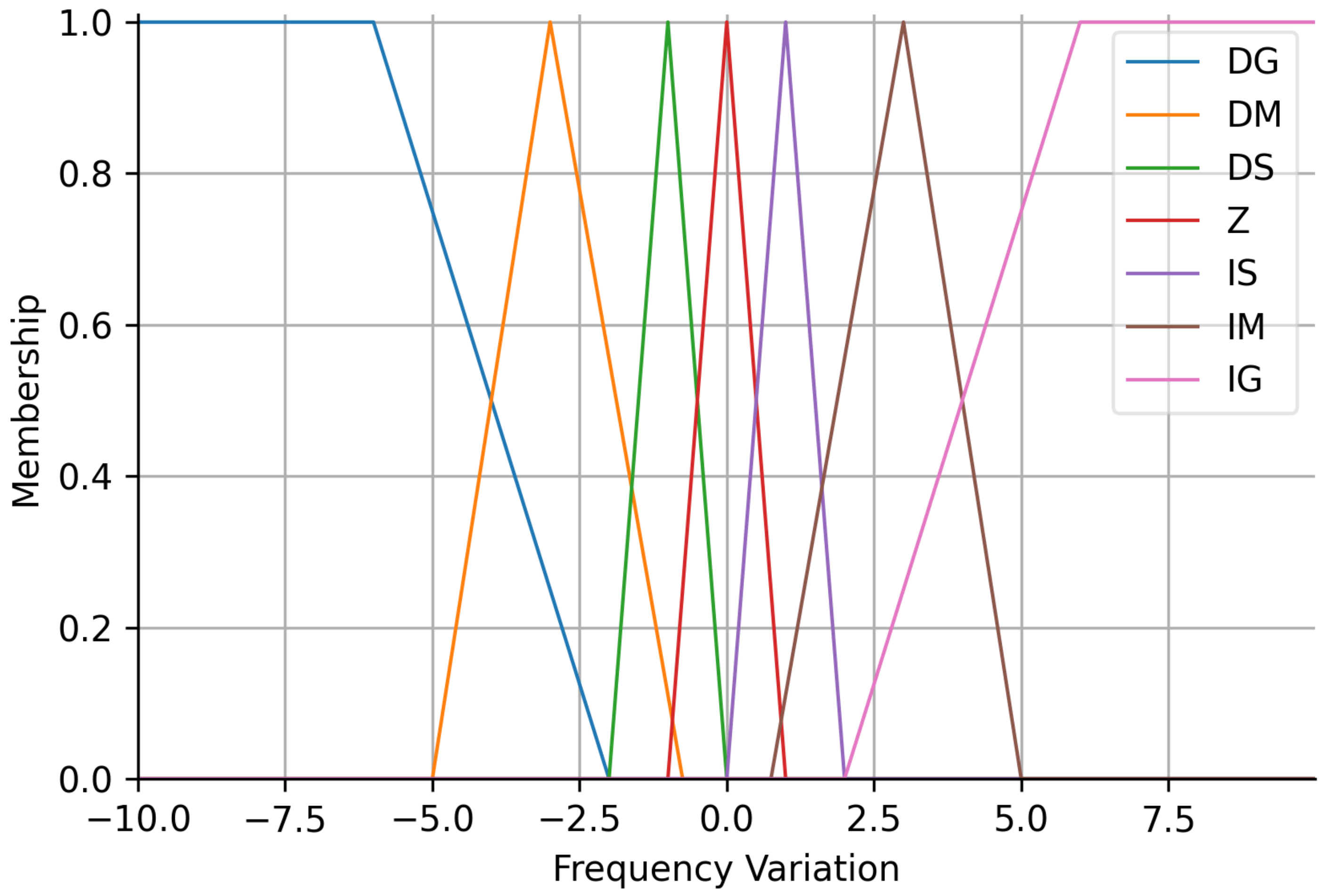

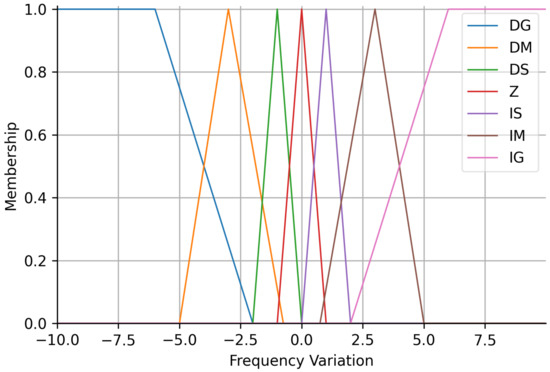

The membership functions of the fuzzy control output variable is shown in Figure 5. The determination of these functions is based on the acceleration ramp of the frequency inverter used to drive the pump set, which has a maximum rotation frequency of 4 Hz. Decrease small (DS), decrease medium (DM), decrease big (DB), zero (Z), increase big (IB), increase medium (IM), and increase small (IS) are the linguistic variables of the output.

Figure 5.

Membership function of the frequency variation (output variable).

3.2.3. Rules Determination

When drafting the rules, we tried to obtain first-order responses with near-zero error. These properties are the result of the study of the system. The presence of high overhangs and abrupt increases in the acting signal cause over-rotation, resulting in rupturing of the channels, and damage to the auxiliary machinery due to seasonal overcurrents during this period.

Table 2 contains 49 rules created empirically by an expert, for the purpose of stabilizing the system at a steady state, in addition to showing a smooth response between the output rules according to the input rules. To deal with language rules, the Mamdani type inference procedure [14] was used, and for the defuzzification step, the centroid method was used.

Table 2.

Fuzzy control rules.

3.2.4. Defuzzification

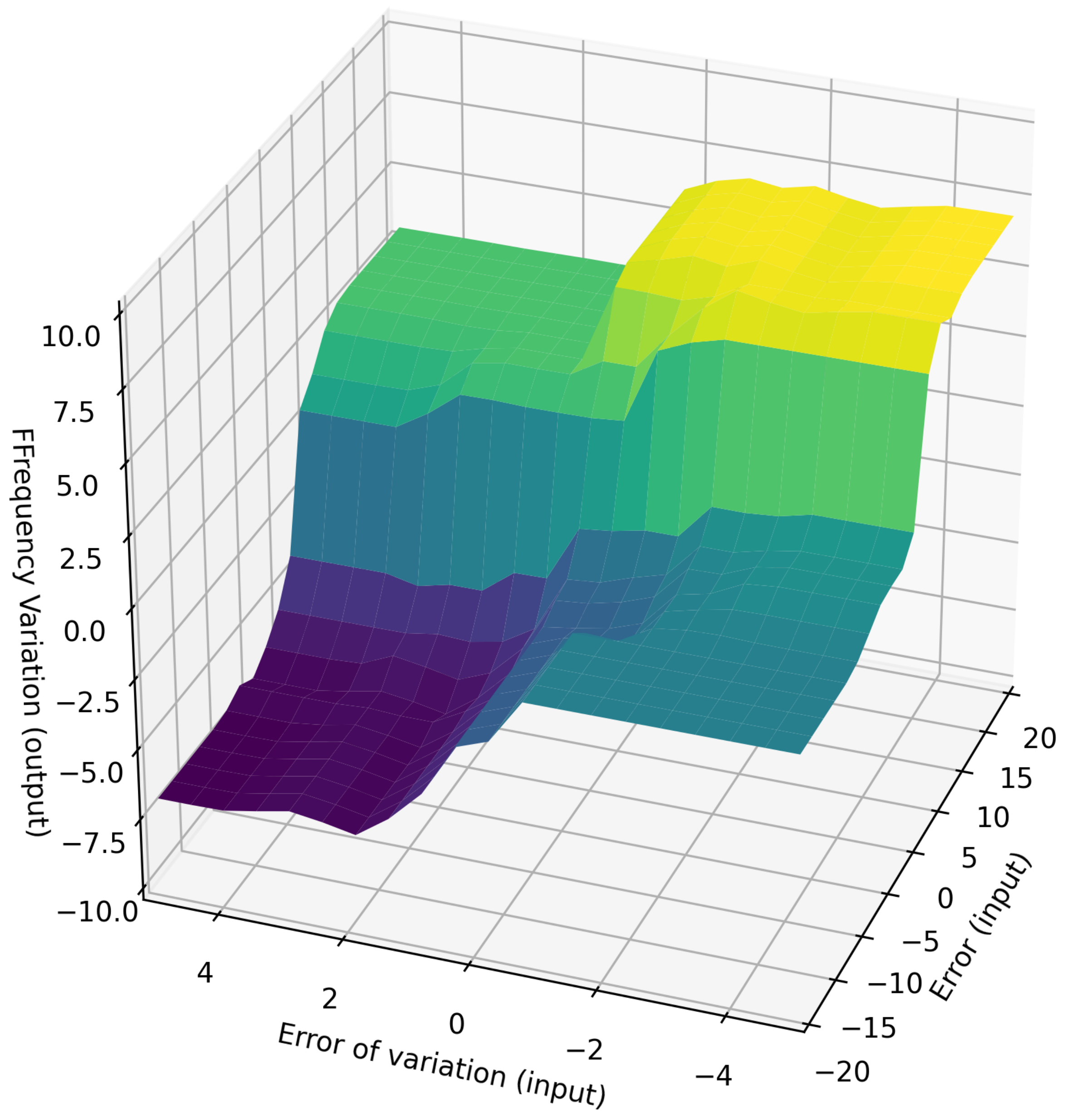

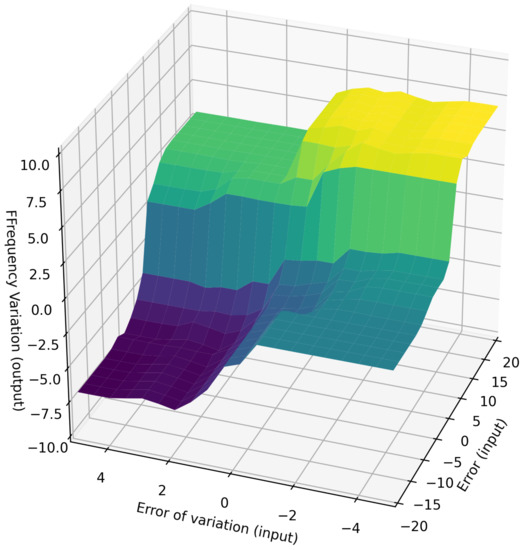

From the rules, the defuzzification process was performed using the mean of maximum method. Figure 6 shows a surface with error and variation of error as the inputs and the frequency variation as the output.

Figure 6.

Relationship between: the inputs—Error variation and error; the output—frequency.

Note in the illustration Figure 6 that the surface can be divided into three sub-regions, as follows:

- Saturation region: with values equal to ±6 Hz, the surface has two saturation regions (negative saturation in blue and positive saturation in yellow). When the error or/and frequency variation are far from zero, the system output reaches these values.

- Steady region: this region is shown in light green and represents the state where frequency variation is almost non-existent. This happens when the error is very small or relatively high, but the error variation is already large enough.

- Convergence region: this area represents the other cases that occur when the system is operating in the intermediate regions in order to reach the surface center.

4. Experimental Results

In this section, the results of the proposed methodology are presented, evaluating the performance of the fuzzy controller, presented in Section 3. The main objective of these experiments is to relate different topologies of motor pump operations to their performance. The experiments are:

- Experiment I: Closed loop test for fuzzy control applied to a single pump set, where the characteristics of the response due to variation of the setpoint and water demand were evaluated.

- Experiment II: Closed loop test for the fuzzy control applied to two sets of pumps connected both in series and in parallel, where we evaluated the characteristics of the response due to variation of the setpoint and water demand.

4.1. Experiment I

The objective of the following experiments was to verify the functioning of the proposed fuzzy controller acting in a single pump and what is its impact on the system performance for each operating point, the following tests were performed:

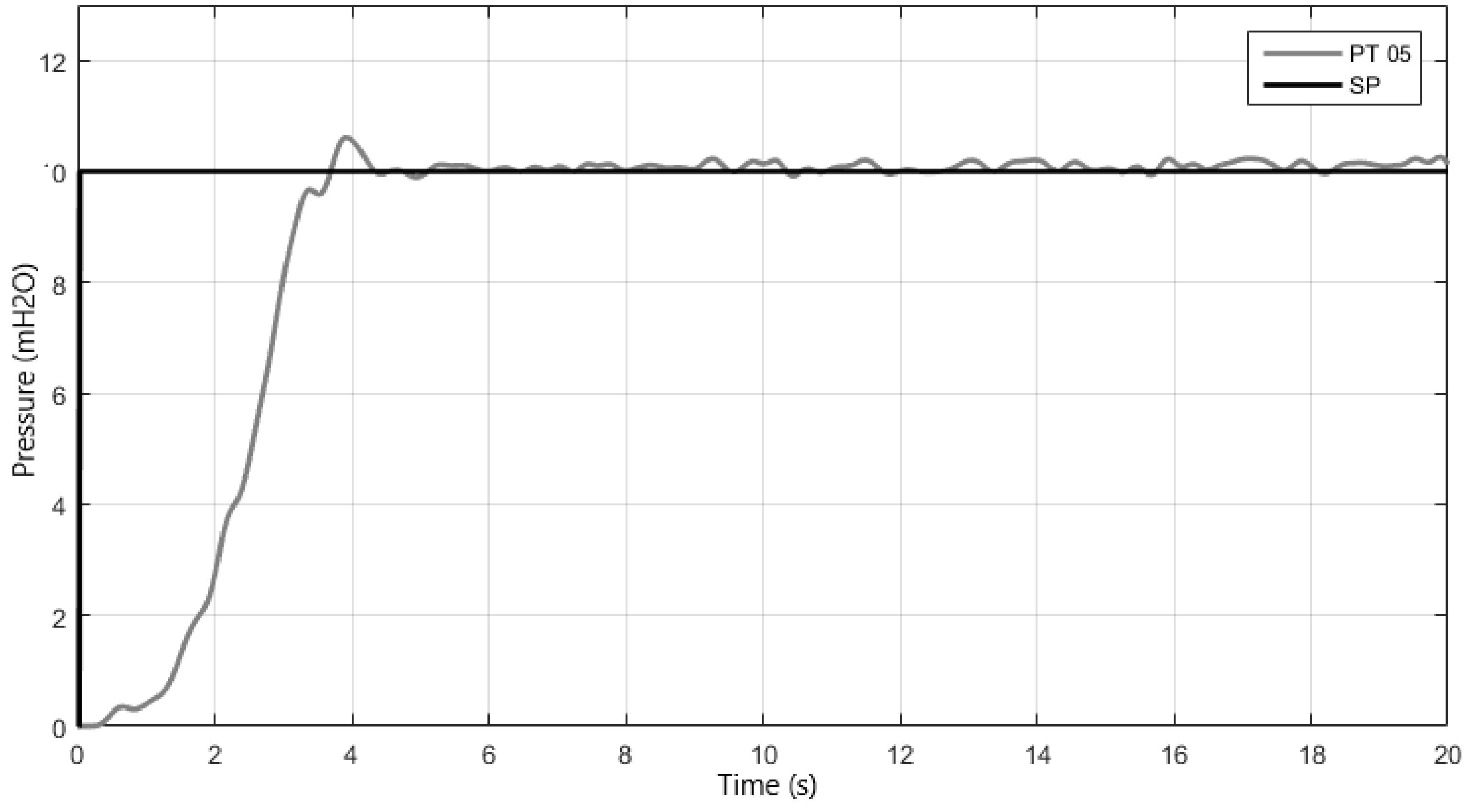

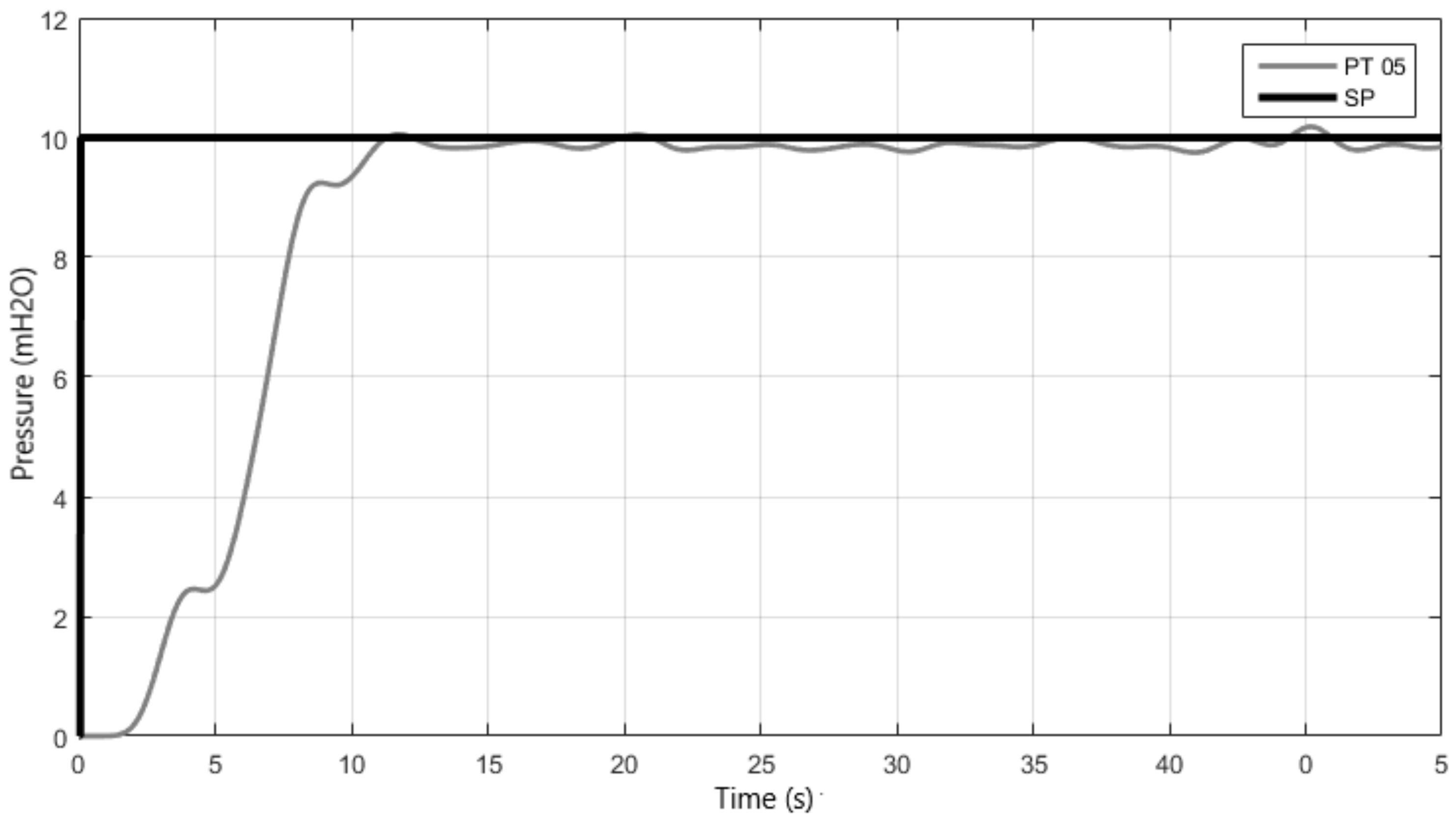

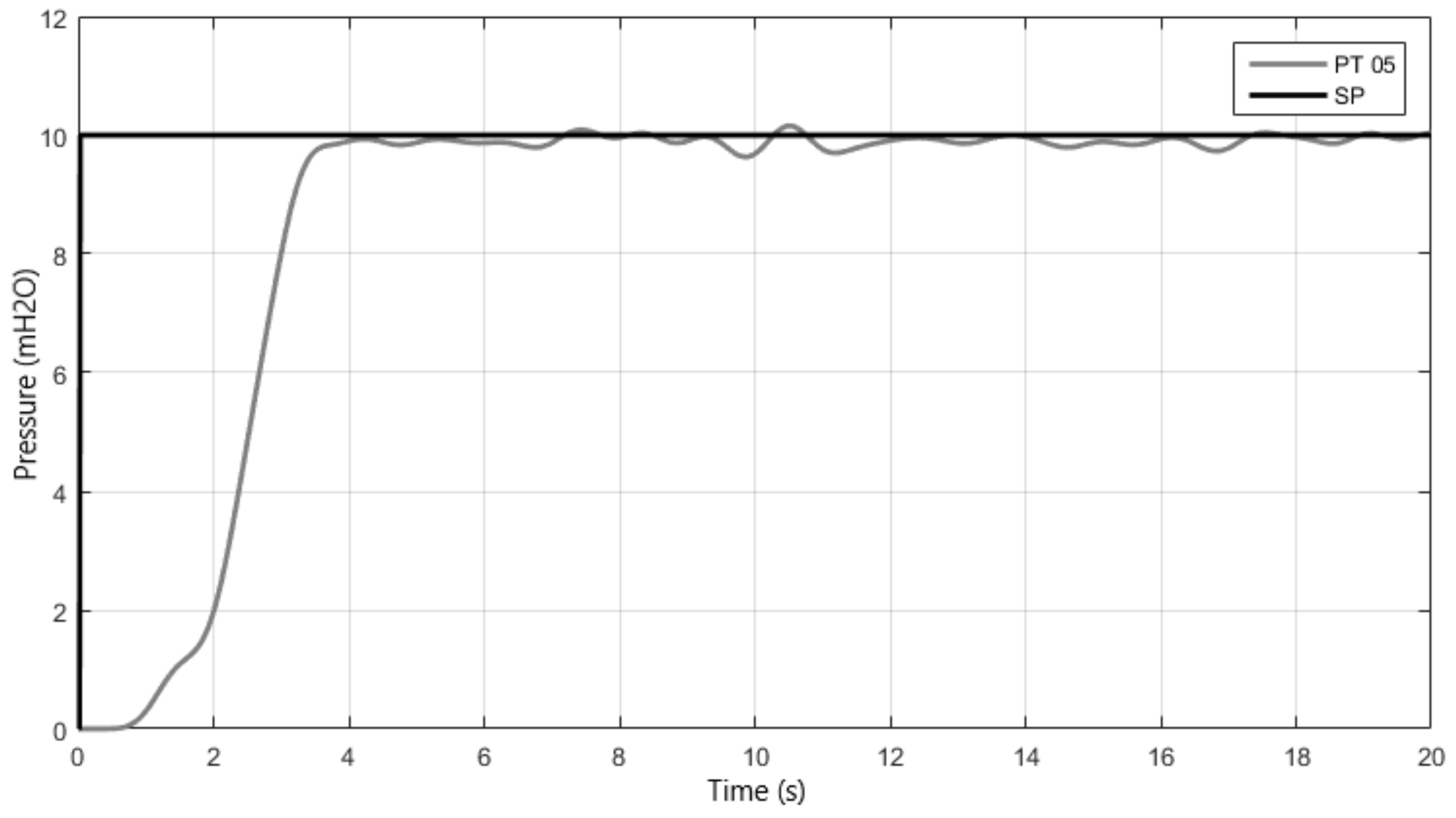

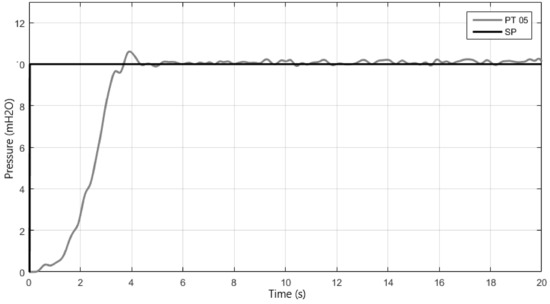

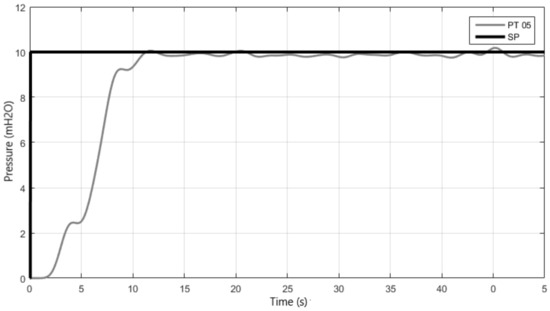

4.1.1. Step Response with Single Pump

The first test was performed with the motor pump 1 (MB 1) starting from rest, i.e., at zero frequency and with the control valve angle (VRP) equal to 35°, this value corresponds to the minimum demand. The desired value equal to 10 mH2O was applied.

In this procedure, it was sought to evaluate the control system in the following aspects: rise time, settling time, percentage overshoot, and error in permanent regime. The response of this controller is presented in Figure 7 and the cited characteristics are present in Table 3.

Figure 7.

Relationship between the set-point and the pressure for the step response of the proposed fuzzy controller.

Table 3.

Time characteristics of the proposed fuzzy controller response (single pump).

4.1.2. Energy Efficiency of the System Operating with a Single Pump

In this experiment, we calculate the energy efficiency of the motor-pump set for different set point. For this, Equation (1) defined by [15] was used, where the system was initially at rest, i.e., the frequency applied to the motor-pump set is equal to zero and the control valve (VRP) angle is equal to 35°.

where:

- : Efficiency (%);

- : Specific weight of fluid;

- Q: Flow;

- H: Pressure;

- P: Electric power (kW).

This way, the initial desired value was set equal to 8 mH2O, and it was incremented with a step of 2 mH2O until it reached 14 mH2O, then decremented with the same step, until it reached 8 mH2O again. These results are illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Energy efficiency of the system with fuzzy control (MB 1).

Analyzing Table 4, one notices that the flow decreases as the pressure increases. This occurs because the pump operates close to the nominal rotation, thus requiring maximum power, that is, exceeding the system’s ideal operating point.

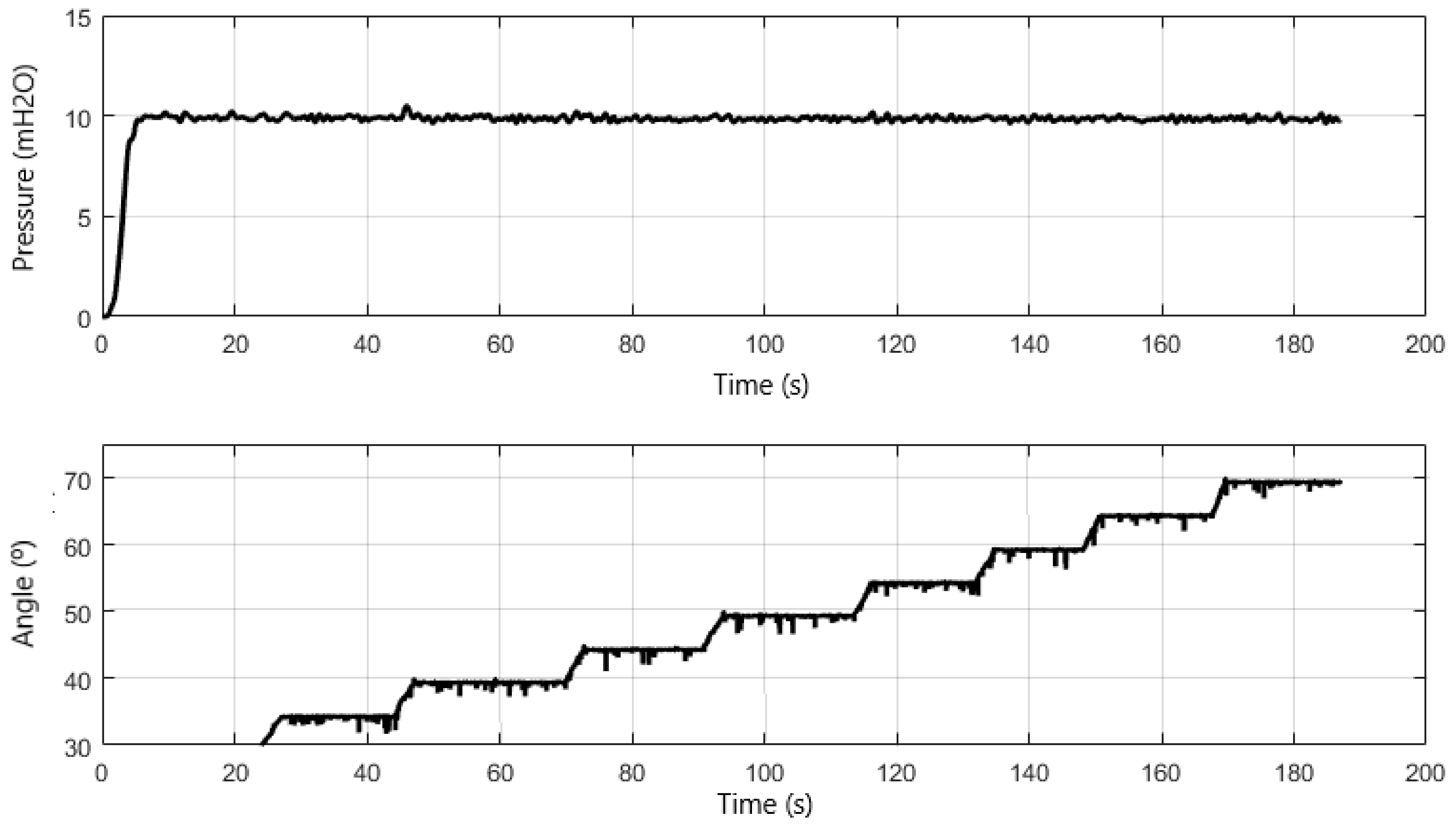

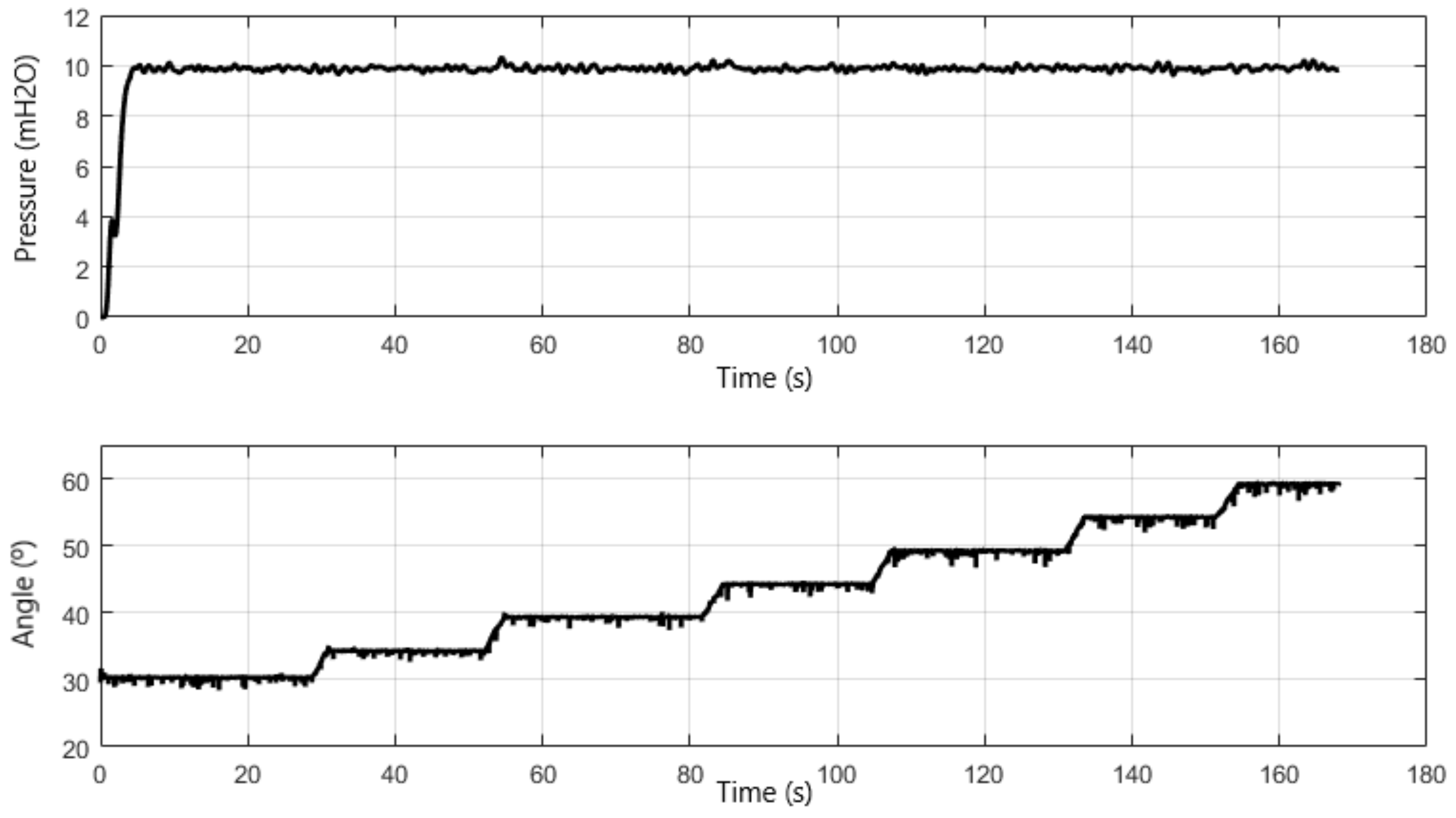

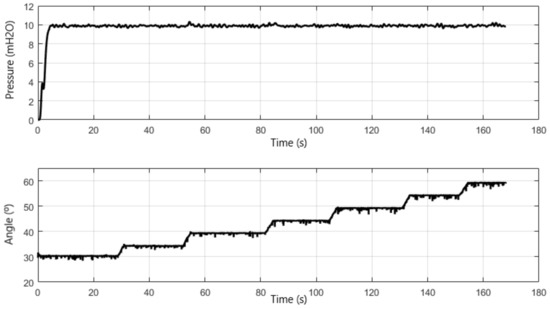

4.1.3. Response of Fuzzy Control to Variable Water Demand for a Single Pump

In this experiment, the with pump set 1 (MB 1) starts with frequency equal to zero and with the control valve (VRP) angle equal to 30°. Therefore, a virtual instrument was developed in LabVIEW software to emulate the water demand over time through remote operation of the proportional valve (VRP).

Note in Figure 8 that the controller response remains constant throughout the test. To determine the steady state error, all the values in the time interval from 10 to 180 s were averaged and subtracted from the desired value, yielding a value of 0.47%.

Figure 8.

Response of the controlled system under varying water demand for a single pump (MB 1).

4.2. Experiment II

This experiment aims to evaluate the application of fuzzy control for series and parallel motor pump configurations in a water supply system for energy efficiency.

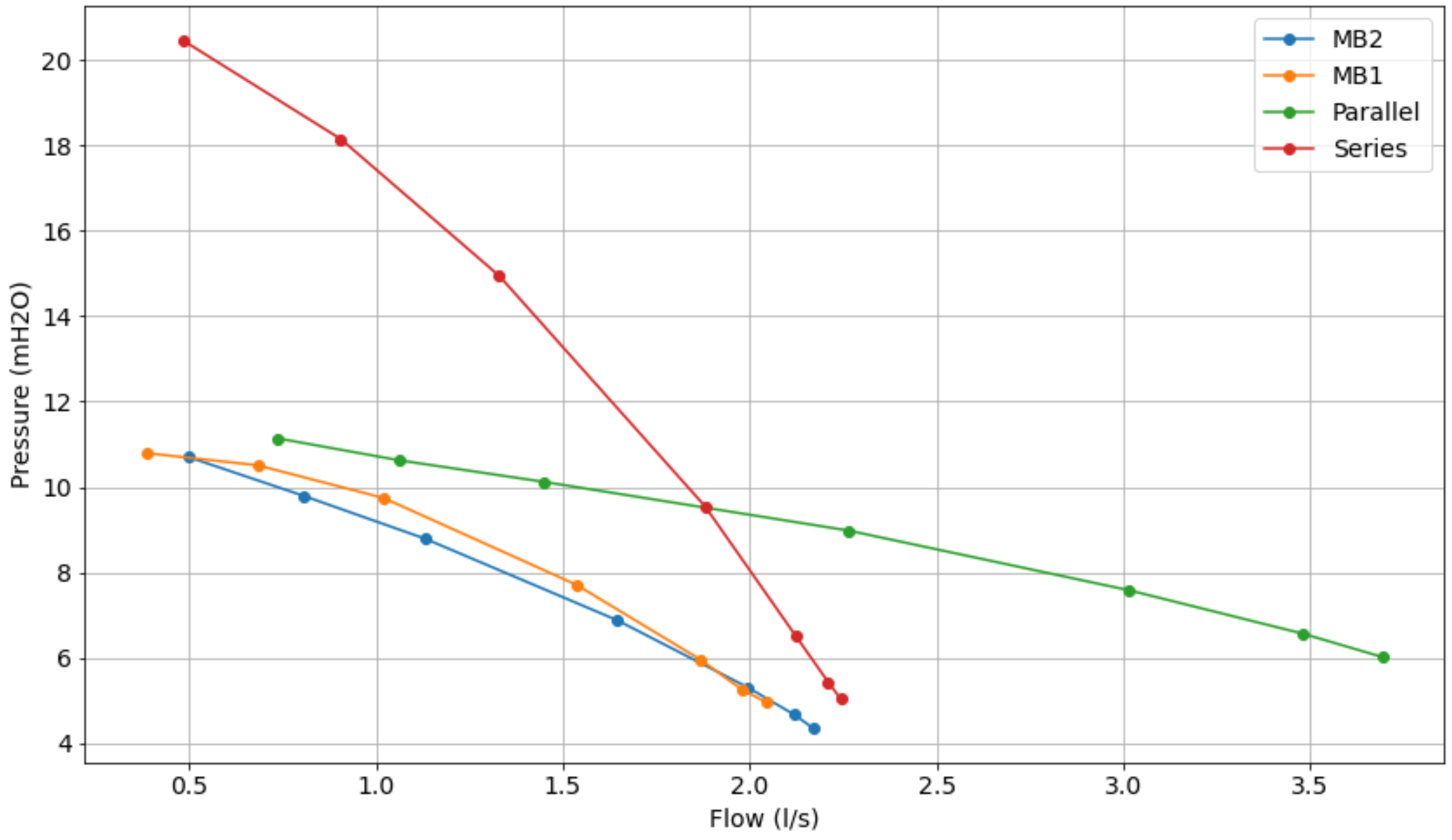

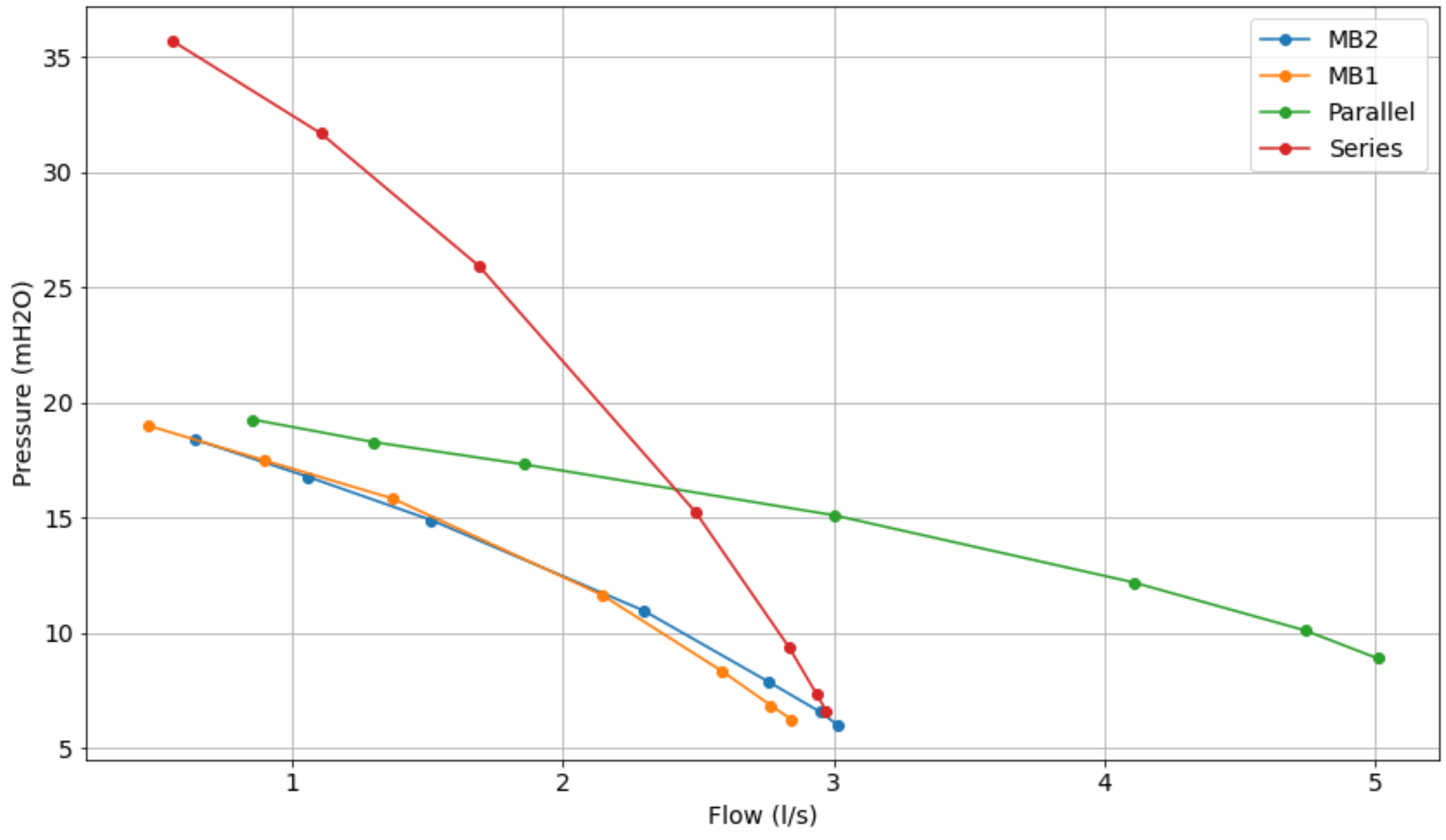

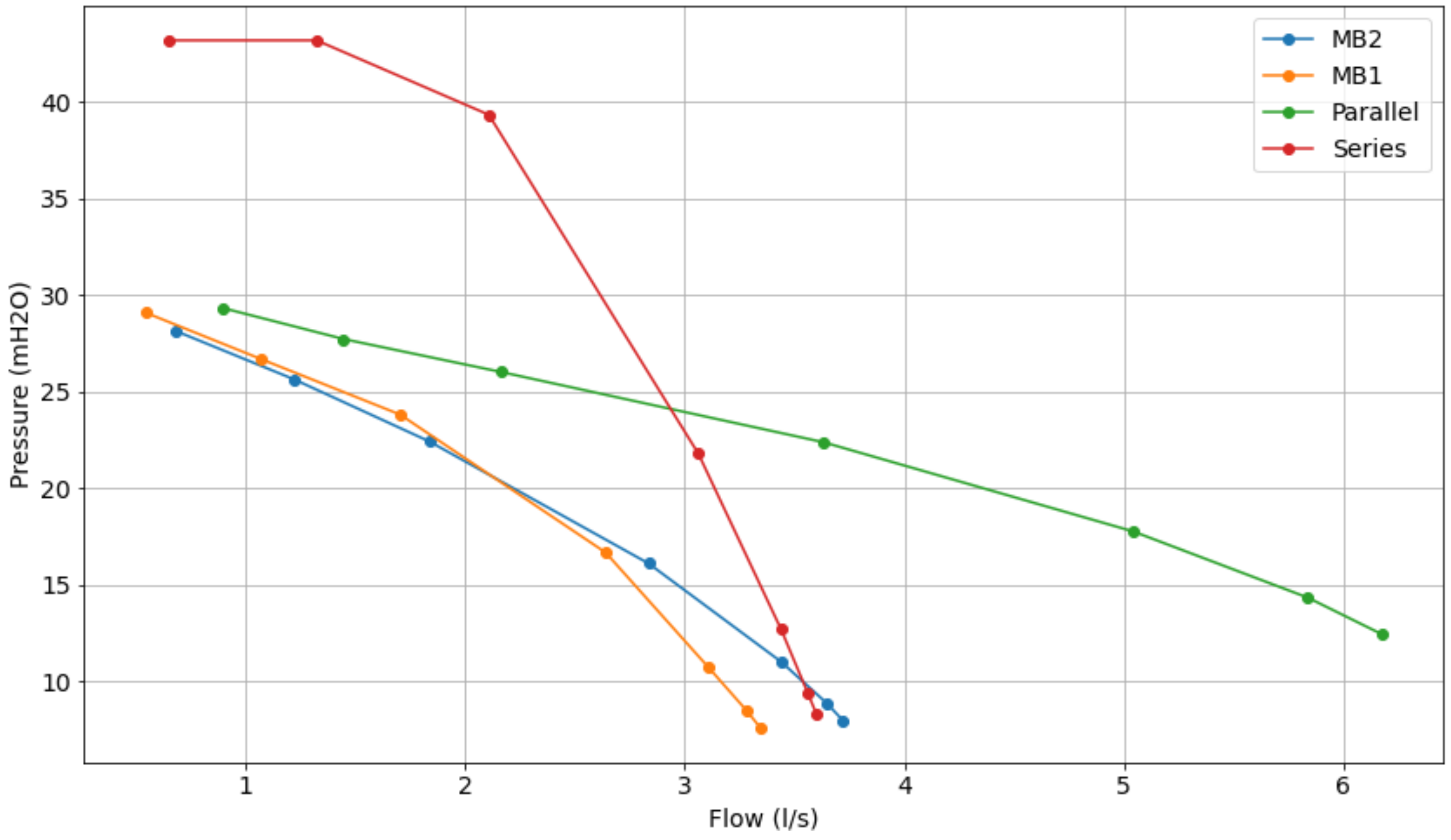

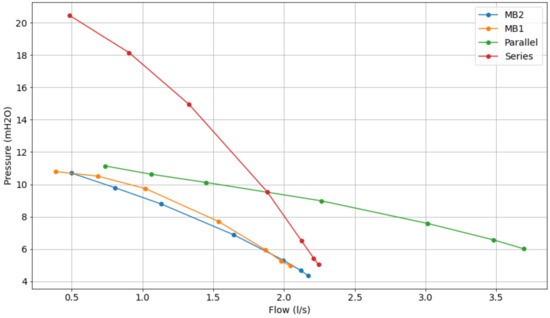

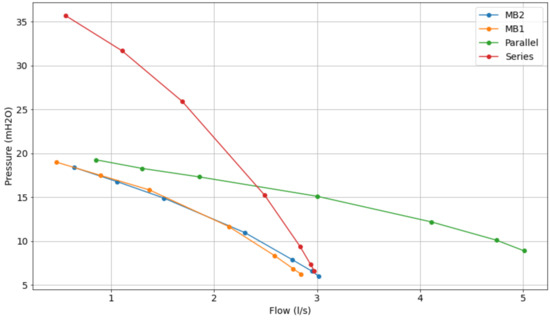

4.2.1. Pump Characteristics Curve

In the first place, before the application of the proposed controller, comparative analyses of the characteristic curves of the pumps were performed. The objective of this experiment is to compare the operating and efficiency range of the pump sets for the following situations: a single pump operating, two pumps connected in series, and two pumps connected in parallel.

The series and parallel configurations were obtained from the manual closing of the registers present on the experimental bench. Initially, the system was considered with the pumps starting with a rotation frequency equal to zero and the control valve equal to 90°. After this, the frequencies 30, 40, and 50 Hz were applied, and for each of these frequencies the valve was positioned at the following angle values: 90°, 60°, 50°, 40°, 30°, 20°, 10°, and 0°, emulating the decay of the manometric height at the discharge of the system.

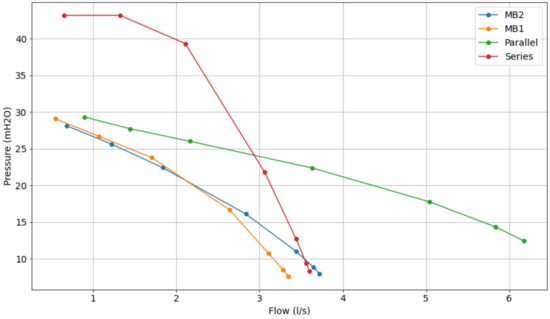

In Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, it can be seen that the series operation of the pumps reaches the sum of the individual pressure heights and the flow value approaches that of the operation of a single pump. The parallel connection gives the average of the individual pressures and approximately the sum of the flow rates of the two pumps.

Figure 9.

Comparative characteristic curve of pumps operating at 30 Hz.

Figure 10.

Comparative characteristic curve of pumps operating at 40 Hz.

Figure 11.

Comparative characteristic curve of pumps operating at 50 Hz.

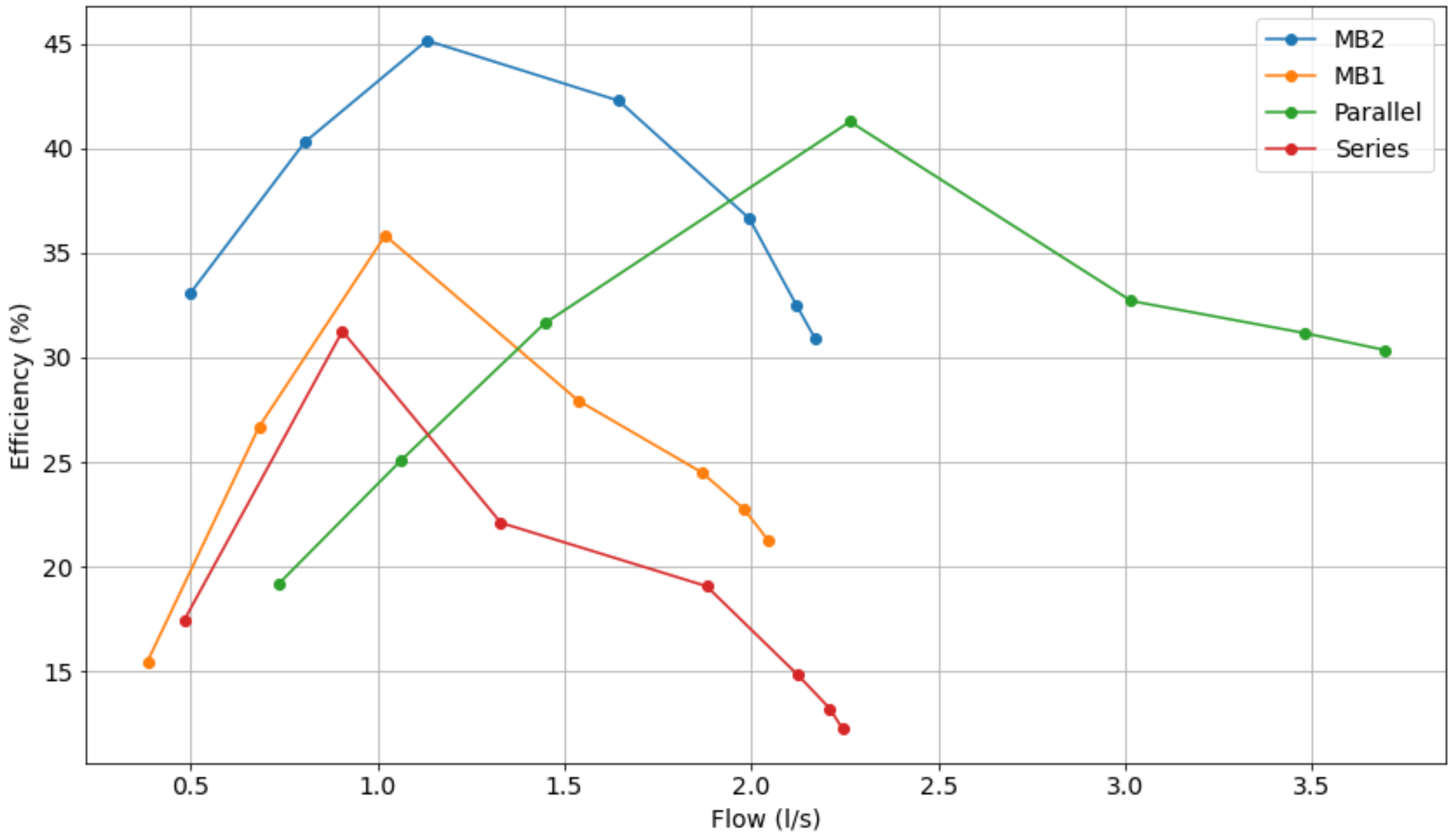

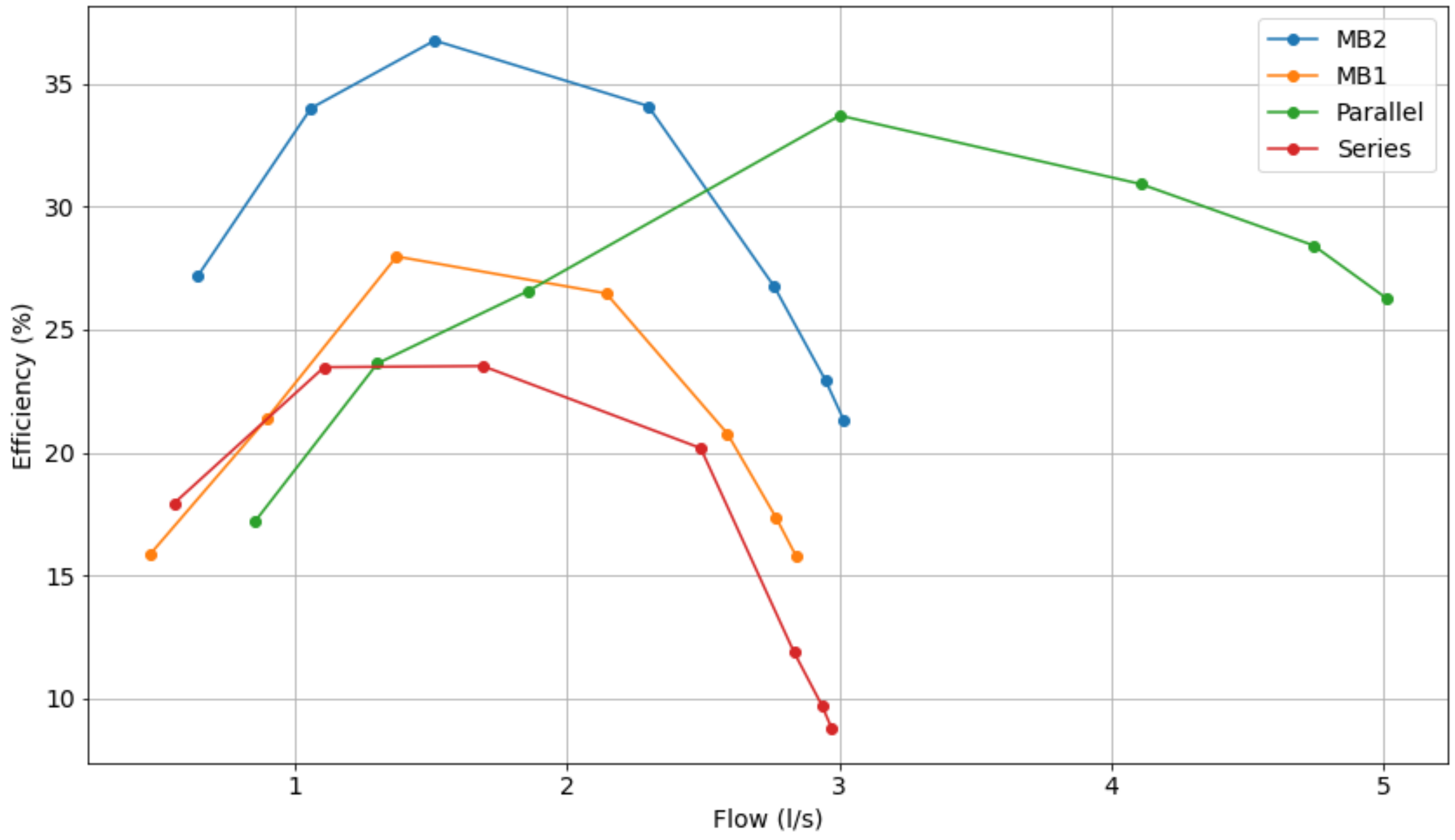

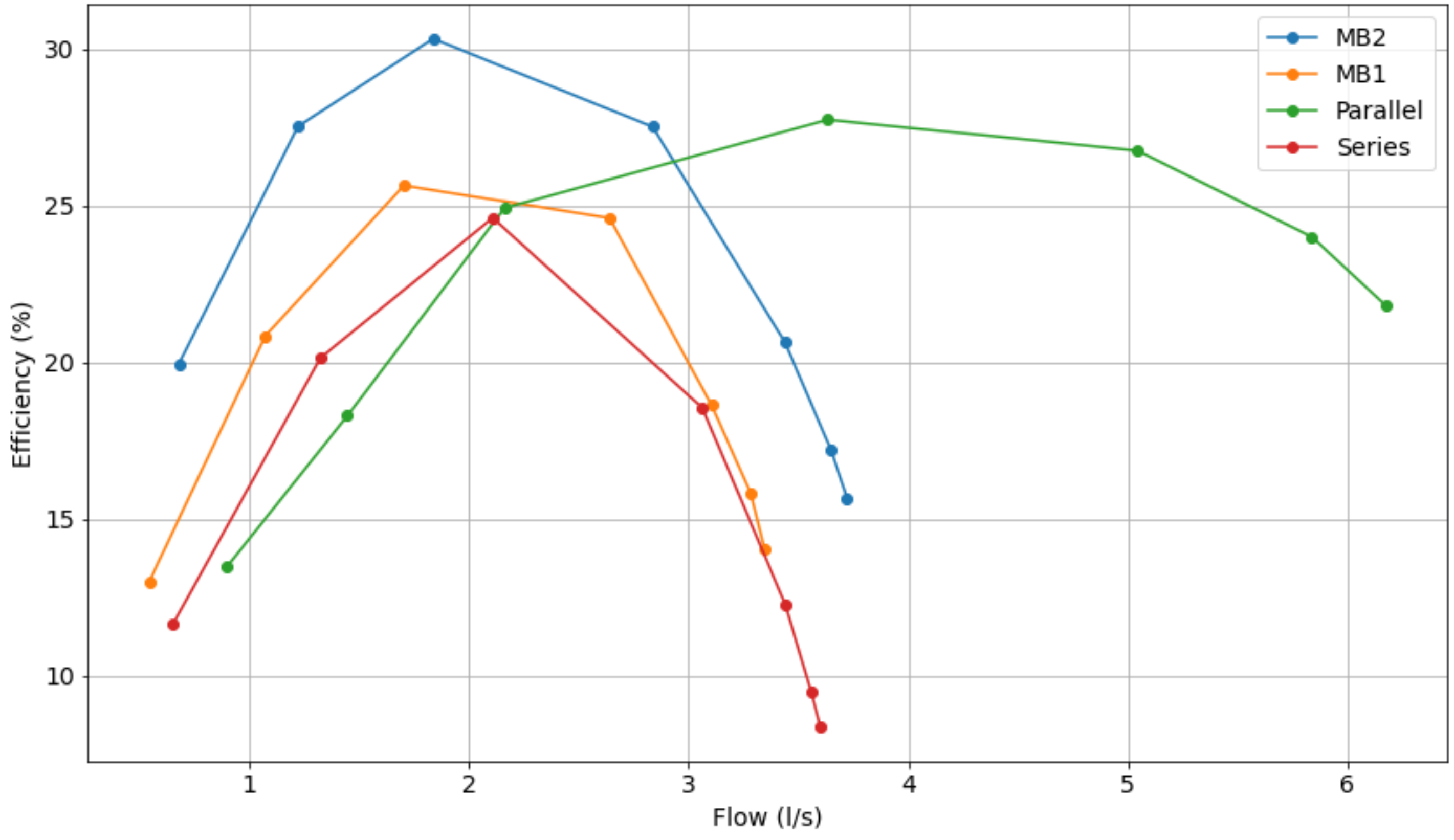

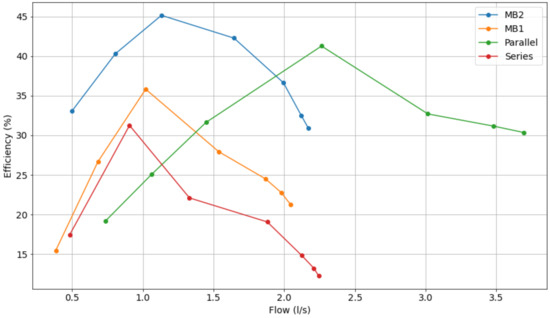

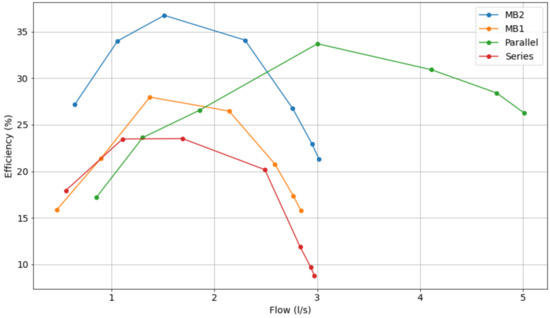

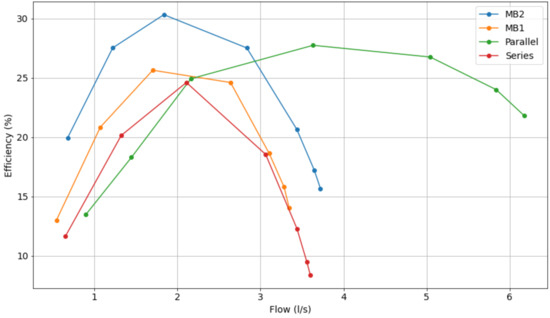

In addition, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14 show the comparative curve of energy efficiency for various operating points, showing which operating configuration is more viable, i.e., at which times series or parallel operation is more efficient than using a single pump.

Figure 12.

Comparative characteristic curve of the energy efficiencies of pumps operating at 30 Hz.

Figure 13.

Comparative characteristic curve of the energy efficiencies of pumps operating at 40 Hz.

Figure 14.

Comparative characteristic curve of the energy efficiencies of pumps operating at 50 Hz.

The procedure for choosing the configuration with the highest efficiency for a given system operating point consists in using the curves in Figure 9 and Figure 11, where the pressure of 10 mH2O was taken as the desired value; thus, a line parallel to the x-axis was drawn on the curve in Figure 9, this line intersects the 4 characteristic curves of the pump, where the flows are: 1 L/s (MB 1), 0.9 L/s (MB 2), 1.5 L/s (parallel), and 1.8 L/s (series).

Selecting the flow values mentioned in the previous paragraph in the curve of Figure refcurve04, one can determine the corresponding yield, as follows: 35% (MB 1), 42.5% (MB 2), 23% (parallel) and 30.5% (series). Note that the efficiency of pump motor set 2 is the highest, so the system will operate using this configuration.

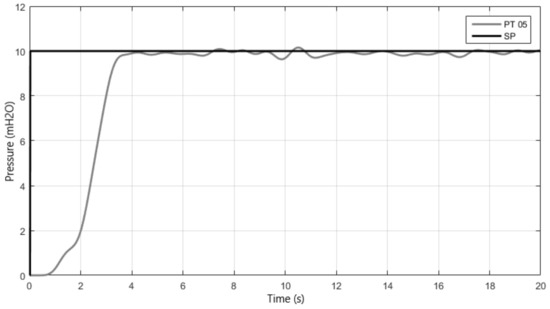

4.2.2. Fuzzy Control for the Pumps Operating in Series

In this experiment, the pump sets 1 and 2 connected in series, starting with rotation speed equal to zero, with the control valve (VRP) angle equal to 35° and desired value equal to 10 mH2O. The step response curve is shown in Figure 15 and the time characteristics in Table 5.

Figure 15.

Response of fuzzy control with pumps operating in series.

Table 5.

Time characteristics of the response of fuzzy control with pumps operating in series.

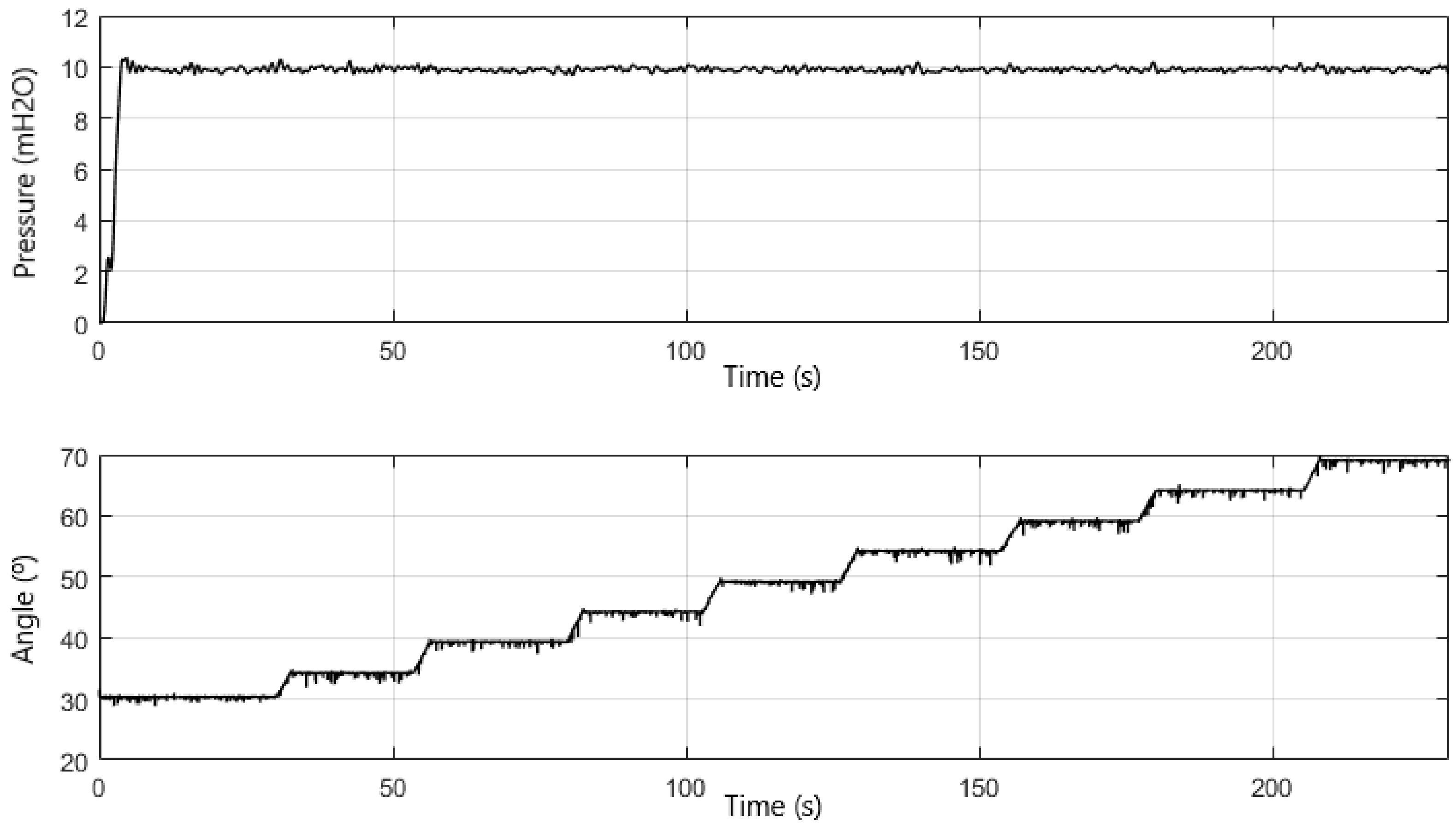

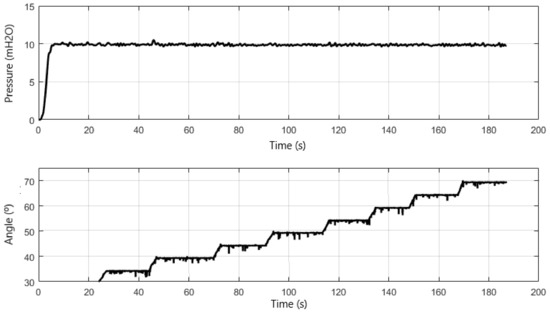

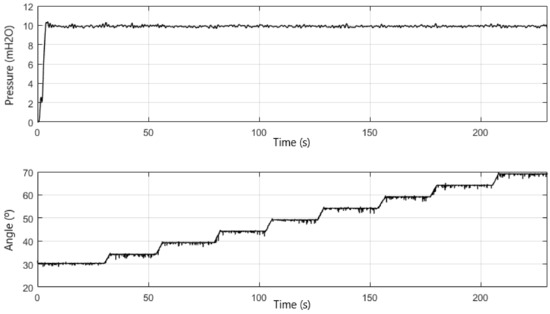

In addition, the robustness of the proposed control system when there is a variation in water demand was verified. To emulate this scenario, the proportional valve was remotely actuated over time with different values, initially at 30°, and this angle was incremented until it reached 60°. The result of this experiment is shown in Figure 16, where the proposed controller is robust to the variation of water demand, remaining stable and with error in permanent regime near zero.

Figure 16.

Response of the system operating with pumps in series to varying water demand.

The energy efficiency of the controlled system for different setpoints was finally evaluated. For this, we considered the motor-pump set starting with rotation speed equal to zero, the angle of the control valve (VRP) equal to 35°, and the initial desired value equal to 8 mH2O. After that, this value was incremented with a step of 2 mH2O until reaching 14 mH2O, then decremented with the same step, until reaching 8 mH2O again. These results are illustrated in Table 6.

Table 6.

Energy efficiency of the system operating with two pumps in series for different setpoints.

4.2.3. Fuzzy Control for the Pumps Operating in Parallel

This test was performed with pump sets 1 and 2 connected in parallel, starting from rest and with the control valve angle (VRP) equal to 35°. The desired value equal to 10 mH2O was applied. The step response curve is shown in Figure 17, and the time characteristics in Table 7.

Figure 17.

Response of fuzzy control with pumps operating in parallel.

Table 7.

Time characteristics of the response of fuzzy control with pumps operating in parallel.

To verify the robustness of the proposed control system, the water demand was varied. For this, a proportional valve was remotely activated over time with different opening angles; initially at 30°, and this angle was incremented until it reached 60°. The result of this experiment is shown in Figure 18, where the controller proved to be robust to the variation of water demand, remaining stable and with permanent error near zero.

Figure 18.

Response of the system operating with pumps in parallel to varying water demand.

Furthermore, the energy efficiency of the controlled system was evaluated for different desired values. For this, we considered the motor-pump set starting from rest, the control valve angle (VRP) equal to 35°, and the initial desired value equal to 8 mH2O, after which this value was increased with a step of 2 mH2O until reaching 14 mH2O, and then decreased with the same step, until reaching 8 mH2O again. These results are illustrated in Table 8.

Table 8.

Energy efficiency of the system operating with two pumps in parallel for different setpoints.

Table 9 presents a comparative analysis of the efficiencies obtained for the 3 types of configurations studied. For this, we used the average of the efficiencies of the desired value presented in Table 4, Table 6 and Table 8.

Table 9.

Comparison of energy efficiency for different topologies of controlled water pumping system operation.

Considering the value of the operation with a single pump as a reference, the operation of the system with pumps in parallel presents an increase of 23.41% in efficiency compared to a single pump. On the other hand, when it is desired to operate in series, there is a decrease in percentage terms of 10.42% in the value of the efficiency of operation of a single pump.

Therefore, fuzzy control, with its ability to handle uncertainty and imprecision, its flexibility, and its ability to mimic human-like decision making, provides a unique and efficient approach compared to traditional control methods such as proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control, model-based control, or rule-based control in managing water supply systems. In the context of pumping systems, fuzzy controllers offer a number of several advantages and unique features:

- Robustness: are able to handle uncertainty and imprecision in the system, making them well suited for applications where the system parameters are not known exactly;

- Flexibility: can be easily modified to handle changes in the system, or to incorporate new control strategies;

- Simplicity: do not require complex mathematical models of the system, making them relatively easy to design and implement;

- Human-like decision making: are able to mimic human-like decision making process, which is suitable for applications where the judgment of human operator is required to be mimicked for a better performance;

- Nonlinearity handling: Nonlinearity is inherent in many systems and fuzzy controllers are well suited for handling nonlinearity;

- Handling multiple inputs and outputs: can handle multiple inputs and outputs, which makes them well suited for complex systems with multiple interacting variables;

- Handling multiple set points: are able to handle multiple and variable set points, rather than a fixed set point, which is not possible with conventional controllers;

- Handling time varying set point: can handle variable set point with respect to time;

- Handling large variations in process variable: are able to handle large variations in process variables that is difficult for conventional controllers.

These are just some of the advantages observed in our paper. It should be noted that, as with any control system, the specific performance of a fuzzy controller will depend on the design and implementation of the controller as well as the characteristics of the system being controlled.

5. Conclusions

In this work, fuzzy controllers have shown to be an effective method for controlling water supply systems with parallel and series pumps. Due to its ability to handle uncertainty and imprecision, its flexibility, and its ability to mimic human-like decision making, fuzzy controllers are well suited for managing the complexity of these systems. Fuzzy controllers can handle multiple inputs and outputs, as well as multiple and variable set points. They are able to handle nonlinearity and large variations in process variable and controller parameters, which is difficult for conventional controllers to handle. The implementation of fuzzy controllers can result in an improved system performance and stability, and can lead to a more efficient and cost-effective management of water supply systems with parallel and series pumps.

The results obtained showed that the fuzzy controller was able to stabilize the hydraulic pressure of the water pumping system, regardless of the topology adopted (single pump, two pumps in series or parallel), in less than 5 s, with a steady state error close to zero. Moreover, in all cases, it was verified the robustness of the control system when the system is subjected to variable water demand, emulated by the variation of the proportional valve.

Operating water pumps in series or parallel can offer several advantages depending on the specific application and system requirements. Pumps in series allow for the total head (pressure) of the pumps to be added together, resulting in a higher overall system pressure, making it a more efficient use of energy, and improving system reliability. On the other hand, operating pumps in parallel allows for the flow rate to be increased without increasing the system pressure, improved system reliability, reduced maintenance, and increased redundancy. It is important to note that whether to operate the pumps in series or parallel depends on the specific system requirements, such as the desired flow rate, head and pressure, and the system reliability and availability. Both operating the pumps in series and parallel have their own specific advantages, and a balance must be struck between the two approaches to achieve optimal performance for the specific system at hand.

In terms of energy efficiency, the efficiency and pump operation curves show that there are operation points where the pumping system reaches maximum energy efficiency. Comparing the single pump operation, series, and parallel, as illustrated in Table 9, it is noticeable that the use of two pumps in parallel presents higher efficiency, since it is possible to supply the water demand with less rotation, and consequently less electrical energy.

In future research, we will seek to develop a mechanism that can calculate and compare the efficiencies of different operation topologies (single pump, two pumps in parallel or in series), through which it will be possible to switch the controller to one of these configurations, in order to achieve the maximum energy efficiency of the system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.S.F. and J.M.M.V.; methodology, T.K.S.F. and J.M.M.V.; software, T.K.S.F.; validation, T.K.S.F., J.M.M.V. and H.P.G.; formal analysis, T.K.S.F.; investigation, T.K.S.F.; resources, H.P.G.; data curation, T.K.S.F. and J.M.M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K.S.F., J.M.M.V., T.K.S.F., J.M.M.V. and H.P.G.; visualization, J.M.M.V.; supervision, J.M.M.V.; project administration, J.M.M.V.; funding acquisition, J.M.M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank CNPq, CAPES, the PostGraduate Program in Electrical Engineering of UFPB and the LENHS Laboratory of UFPB for the financial and material support in the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WDN | Water Distribution Networks |

| LENHS | Laboratory of Energy Efficiency and Hydraulics in Sanitation |

| UFPB | Federal University of Paraiba |

| VRP | Pressure-Reducing Valves |

| SIMO | Single Input Multiple Output |

| PWPS | Photovoltaic Water Pumping System |

| DTC | Direct Torque Control |

| FLC | Fuzzy Logic Control |

| ITAE | Integral of Time and Absolute Error |

| ITSE | Integral of Time and Squared Error |

| IAE | Integral Absolute Error |

| ISE | Integral Squared Error |

| NFC | neuro-fuzzy controller |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| PT | Pressure Transducers |

| FT | Flow Transducers |

| DAQ | Data Acquisition System |

| mH2O | Meter of Water Column |

| MB 1 | Motor Pump 1 |

| MB 2 | Motor Pump 2 |

| PC | Personal Computer |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| PI | Proportional Integral |

| PId | Proportional Integral Derivative |

References

- Al-washali, T.; Sharma, S.; Kennedy, M. Methods of assessment of water losses in water supply systems: A review. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 4985–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaco, E.; Campisano, A.; Franchini, M.; Modica, C. Unsteady flow modeling of pressure real-time control in water distribution networks. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brentan, B.; Meirelles, G.; Luvizotto, E., Jr.; Izquierdo, J. Joint operation of pressure-reducing valves and pumps for improving the efficiency of water distribution systems. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, N.; Giugni, M.; Glielmo, L.; Marini, G.; Zollo, R. Real-time control of pressure for leakage reduction in water distribution network: Field experiments. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2018, 144, 04017096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos de Araújo, J.V.; Villanueva, J.M.M.; Cordula, M.M.; Cardoso, A.A.; Gomes, H.P. Fuzzy Control of Pressure in a Water Supply Network Based on Neural Network System Modeling and IoT Measurements. Sensors 2022, 22, 9130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errouha, M.; Derouich, A.; Motahhir, S.; Zamzoum, O.; El Ouanjli, N.; El Ghzizal, A. Optimization and control of water pumping PV systems using fuzzy logic controller. Energy Rep. 2019, 5, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, L.A.; Al-mshat, H.A. Implementation of fuzzy and PID controller to water level system using LabView. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 116, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Barros Filho, E.G.; Salvino, L.R.; Bezerra, S.D.T.M.; Salvino, M.M.; Gomes, H.P. Intelligent system for control of water distribution networks. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2018, 118, 1270–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, J.; Qiu, A.; Cao, L. Design of constant pressure water supply control system based on fuzzy-PID. In Proceedings of the 2018 33rd Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation (YAC), Nanjing, China, 18–20 May 2018; pp. 891–894. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, T.K.S.; Villanueva, J.M.M.; Gomes, H.P.; Catunda, S.Y. Indirect feedback measurement of flow in a water pumping network employing artificial intelligence. Sensors 2020, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechenik, M.; Burian, S.; Pushkar, M.; Zemlianukhina, H. Analysis of the Energy Efficiency of Pressure Stabilization Cascade Pump System. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Modern Electrical and Energy Systems (MEES), Kremenchuk, Ukraine, 23–25 September 2019; pp. 490–493. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, T.K.; Villanueva, J.M.; Catunda, S.Y.; Gomes, H.P. Fuzzy pressure control system in water supply networks with series-parallel pumps. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), Auckland, New Zealand, 20–23 May 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, H.A.M.; Gomes, H.P.; Villanueva, J.M.M.; de Tarso Marques Bezerra, S. Real-time neuro-fuzzy controller for pressure adjustment in water distribution systems. Water Supply 2021, 21, 1177–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, T.J. Fuzzy logic with engineering applications. In Fuzzy Logic with Engineering Applications; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Volume 2, p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- Latifi, M.; Farahi Moghadam, K.; Naeeni, S.T. Pressure and energy management in water distribution networks through optimal use of Pump-As-Turbines along with pressure-reducing valves. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2020, 147, 04021039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).