A Review of Computational Methods and Tools for Life Cycle Assessment of Traction Battery Systems †

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Traction Battery Technologies

- Component level variability, from cell components to module and pack assemblies.

- Chemistry level variability, considering both electrode (anode and cathode) compositions and all the other influencing factors such as the electrolyte composition and ceramic coating materials.

- Design level variability, which influences energy density and module assembly techniques.

- Production process variability, considering both the energy consumption and the specific technology in the extraction and manufacturing processes.

1.2. Life Cycle Assessment Overview

- Defining the functional unit and setting the system boundaries, such as cradle-to-gate (e.g., excluding end-of-life) or cradle-to-grave (e.g., including end-of-life).

- Availability of primary data on component inventory (weight, chemical composition, or pack configuration) or manufacturing processes (energy consumption, waste management, manufacturing technology, or direct emission).

- Geographical location of battery pack manufacturing and use.

- Realistic energy consumption for the use phase impact.

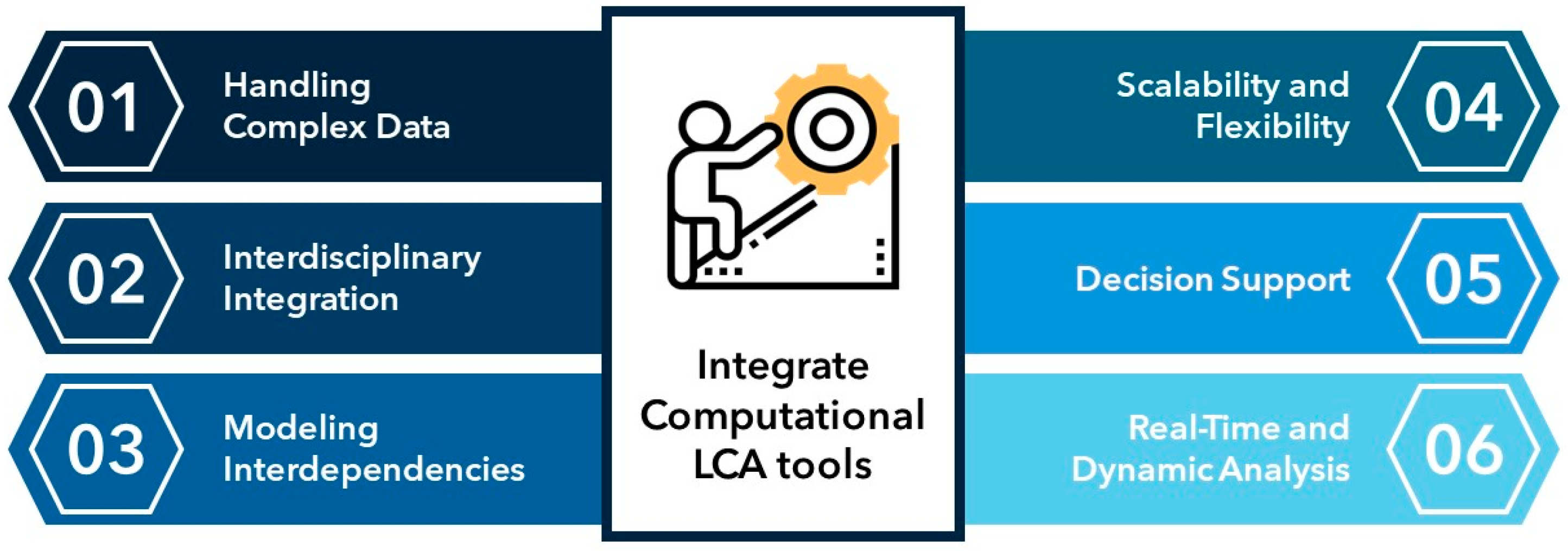

1.3. Integrating LCA Tools into Engineering: Requirements and Challenges

- Requirements from country regulations, market demands, and management strategies.

- Supply chain knowledge and deep comprehension of the product foreground system.

- Relevant single life cycle phase parameters (e.g., manufacturing or use phase).

- Direct information on the recyclability and EoL path from different countries.

2. Materials and Methods

- Starting from the collected articles from different literature engine databases—237 for Traction Battery SoA and 180 for Computational Tool SoA—the duplicates are excluded, deleting 30 and 9 studies, respectively.

- Next, a three-phase screening (title, followed by abstract, and finally the full text) is conducted, based on the connection between the study’s topic and the following research questions:

- Traction Battery SoA

- ∘

- Q1: How are technology variabilities (component, design, materials, and manufacturing processes) represented, and how do they influence the LCA results?

- ∘

- Q2: How does the inventory modeling (primary data, geographic locations, energy consumption) influence the environmental impacts of traction batteries?

- ∘

- Q3: How can the LCA results be standardized to account for the variability in system boundaries, functional units, and impact assessment methods?

- Computational Tool SoA

- ∘

- Q1: What are the main features and benefits of computational LCA tools used for assessing the environmental impacts of complex product systems?

- ∘

- Q2: What frameworks do computational LCA tools use to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the impact results, considering the technological and environmental variability? Are they flexible or scalable?

- ∘

- Q3: In what ways can computational tools support interdisciplinary groups in the product design process?

- 3.

- The selected studies are then in-depth reviewed and characterized according to various features (see Supplementary Materials Table S2). For traction batteries, both the technical aspects and environmental qualitative and quantitative data are analyzed; in contrast, for computational tools, the main topics, the general benefits, and the level of computational integration are evaluated.

- 4.

- Lastly, specific applications for the two topics—Computational modeling focus and Traction Battery focus—are identified in order to describe the computational LCA tools for battery traction, integrating insights from both the traction battery and computational tool perspectives.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Traction Battery State of the Art

3.1.1. Traction Battery State of the Art: Reviews

3.1.2. Traction Battery State of the Art: Cradle-to-Grave LCA

3.1.3. Traction Battery State of the Art: Manufacturing or Use Phase Focus

3.1.4. Traction Battery State of the Art: Recycling Assessment

- High technology process variability and lack of primary industrial-scale data.

- Different system boundaries.

- Chemistry of the cathode, which can affect the energy required in the recycling step.

- Recovery of non-valuable materials such as anode electrodes.

- Quality of the recycled materials.

- Geographic specificity of the recycling process (plant typology and electricity mix).

3.2. Computational Tool State of the Art

3.2.1. Computational Tool State of the Art: General and Theoretical Innovations

- Dynamic LCA (dLCA) incorporates the temporal dimension in evaluating the environmental impact of a product.

- Prospective LCA (pLCA) explores potential future scenarios of emerging technologies.

- Process-based LCA focuses on detailing how individual unit processes of a system are interconnected, using parameterized inventories to update newly available data.

- Hybrid-based LCA (hLCA) uses integrated assessment models (IAMs) to model parameterized current and future foreground systems, typically incorporating social or economic assessments for more realistic evaluations.

3.2.2. Computational Tool State of the Art: Practical Tool Applications

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

- Traction Battery SoA

- ∘

- Q1: How are technology variabilities (component, design, materials, and manufacturing processes) represented, and how do they influence the LCA results?

- ∘

- AnsQ1: The technological variabilities are typically represented and analyzed from the specific case study point of view through a detailed inventory database. These variabilities significantly influence the LCA results, making it challenging to identify the environmental benefits. These variabilities introduce a high degree of complexity, as they are often case-specific and can lead to considerable differences in results. The findings suggest that to accurately capture the environmental footprint of traction batteries, it is essential to consider a wide range of technological factors and to move beyond single case studies. Future research should focus on developing methods to systematically integrate these variabilities into LCA models.

- ∘

- Q2: How does the inventory modeling (primary data, geographic locations, energy consumption) influence the environmental impacts of traction batteries?

- ∘

- AnsQ2: Accurate inventory modeling ensures that the analysis reflects real-world conditions, leading to more accurate and reliable results. The academic interest is focusing on primary data for the manufacturing use phase and on sensitivity analysis based on geographical context and end-of-life route. Clearly, the environmental results are affected by specific case study assumptions that need to be accounted for by policymakers to improve the robustness of the results.

- ∘

- Q3: How can LCA results be standardized to account for the variability in system boundaries, functional units, and impact assessment methods?

- ∘

- AnsQ3: This study identified several challenges in the standardization of LCA results, primarily due to inconsistencies in system boundaries, functional units, and impact assessment methods across different studies. These differences make it difficult to compare results or draw general conclusions. The scientific community should work together to create clear guidelines and standardized practices for LCA. This will make it easier to compare and obtain reliable data for policymakers and industry stakeholders.

- Computational Tool SoA

- ∘

- Q1: What are the main features and benefits of computational LCA tools used for assessing the environmental impacts of complex product systems?

- ∘

- AnsQ1: The main features of computational LCA tools include the ability to handle large datasets, perform detailed and high-resolution modeling, and incorporate various factors such as temporal and geographic variability. This tool also offers the ability to simulate different scenarios and assess the effects of various design choices. Future research should focus on improving their usability and integration into broader decision-making processes.

- ∘

- Q2: What frameworks do computational LCA tools use to ensure the accuracy and reliability of impact results, considering the technological and environmental variability? Are they flexible or scalable?

- ∘

- AnsQ2: Current LCA frameworks are focusing mainly on the spatial and temporal flexibility of the results, leaving out the scalability of technological and scientific features of the product system. From the traction battery point of view, design flexibility (e.g., cell mass or battery pack composition) or real-world use phase data need to still be explored and embedded in a computational framework.

- ∘

- Q3: In what ways can computational tools support interdisciplinary groups in the product design process?

- ∘

- AnsQ3: These tools can combine insights from engineering, environmental science, and economics, among other fields, to provide a holistic view of the product’s environmental impact. By incorporating spatial and temporal factors, computational tools enable designers to consider the full life cycle of a product. This integrated approach facilitates more informed decision-making, helping to ensure that products are designed with sustainability in mind.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y. Lifecycle Battery Carbon Footprint Analysis for Battery Sustainability with Energy Digitalization and Artificial Intelligence. Appl. Energy 2024, 371, 123665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouter, A.; Guichet, X. The Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Automotive Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Statistical Review of Life Cycle Assessment Studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 344, 130994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeau-Bettez, G.; Hawkins, T.R.; Strømman, A.H. Life Cycle Environmental Assessment of Lithium-Ion and Nickel Metal Hydride Batteries for Plug-In Hybrid and Battery Electric Vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 4548–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notter, D.A.; Gauch, M.; Widmer, R.; Wäger, P.; Stamp, A.; Zah, R.; Althaus, H.-J. Contribution of Li-Ion Batteries to the Environmental Impact of Electric Vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 6550–6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, T.R.; Singh, B.; Majeau-Bettez, G.; Strømman, A.H. Comparative Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Conventional and Electric Vehicles. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 17, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Spangenberger, J.; Ahmed, S.; Gaines, L.; Kelly, J.C.; Wang, M. EverBatt: A Closed-Loop Battery Recycling Cost and Environmental Impacts Model; Argonne National Laboratory (ANL): Argonne, IL, USA, 2019; p. 1530874. [Google Scholar]

- Porzio, J.; Scown, C.D. Life-Cycle Assessment Considerations for Batteries and Battery Materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2100771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, F.; Lin, J.; Manurkar, N.; Fan, E.; Ahmad, A.; Tariq, M.-N.; Wu, F.; Chen, R.; Li, L. Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Critical Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 180, 106164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordelöf, A.; Messagie, M.; Tillman, A.-M.; Ljunggren Söderman, M.; Van Mierlo, J. Environmental Impacts of Hybrid, Plug-in Hybrid, and Battery Electric Vehicles—What Can We Learn from Life Cycle Assessment? Int. J. Life Cycle Assess 2014, 19, 1866–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, R.; Hughson, F.R.; Johnston, J.; Nann, T. On Battery Materials and Methods. Mater. Today Adv. 2020, 6, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; pp. 1–46.

- Cerdas, F. Integrated Computational Life Cycle Engineering for Traction Batteries|SpringerLink; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISSN 2194-0541. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Hu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Huang, K.; Wang, L. The Environmental Footprint of Electric Vehicle Battery Packs during the Production and Use Phases with Different Functional Units. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess 2021, 26, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, P.; Cerdas, F.; Dettmer, T.; Frey, C.; Hentschel, J.; Herrmann, C.; Mirfabrikikar, T.; Schueler, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Natural Graphite Production for Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes Based on Industrial Primary Data. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chordia, M.; Nordelöf, A.; Ellingsen, L.A.-W. Environmental Life Cycle Implications of Upscaling Lithium-Ion Battery Production. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess 2021, 26, 2024–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesage, P.; Mutel, C.; Schenker, U.; Margni, M. Uncertainty Analysis in LCA Using Precalculated Aggregated Datasets. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess 2018, 23, 2248–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucci, C.; Piantini, S.; Savino, G.; Pierini, M. Motorcycle Helmet Selection and Usage for Improved Safety: A Systematic Review on the Protective Effects of Helmet Type and Fastening. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2021, 22, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VOSviewer—Visualizing Scientific Landscapes. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com// (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Nastasi, L.; Fiore, S. Environmental Assessment of Lithium-Ion Battery Lifecycle and of Their Use in Commercial Vehicles. Batteries 2024, 10, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasapu, U.; Hehenberger, P. A Design Process Model for Battery Systems Based on Existing Life Cycle Assessment Results. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 407, 137149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accardo, A.; Dotelli, G.; Spessa, E. A Study on the Cradle-to-Gate Environmental Impacts of Automotive Lithium-Ion Batteries. In Proceedings of the Procedia CIRP; Settineri, L., Priarone, P.C., Eds.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 122, pp. 1077–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Hao, Z.; Cai, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y. Study on the Life Cycle Assessment of Automotive Power Batteries Considering Multi-Cycle Utilization. Energies 2023, 16, 6859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, F.; Yang, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium Nickel Cobalt Manganese Oxide (NCM) Batteries for Electric Passenger Vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 123006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raugei, M.; Winfield, P. Prospective LCA of the Production and EoL Recycling of a Novel Type of Li-Ion Battery for Electric Vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accardo, A.; Dotelli, G.; Musa, M.; Spessa, E. Life Cycle Assessment of an NMC Battery for Application to Electric Light-Duty Commercial Vehicles and Comparison with a Sodium-Nickel-Chloride Battery. APPLIED Sci. 2021, 11, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, D.; Marconi, M.; Pietroni, G. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Two Different Battery Technologies: Lithium Iron Phosphate and Sodium-Sulfur. In Proceedings of the Procedia CIRP; Dewulf, W., Duflou, J., Eds.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 105, pp. 482–488. [Google Scholar]

- Held, M.; Schücking, M. Utilization Effects on Battery Electric Vehicle Life-Cycle Assessment: A Case-Driven Analysis of Two Commercial Mobility Applications. Transp. Res. Part D-Transp. Environ. 2019, 75, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenu, S.; Deviatkin, I.; Hentunen, A.; Myllysilta, M.; Viik, S.; Pihlatie, M. Reducing the Climate Change Impacts of Lithium-Ion Batteries by Their Cautious Management through Integration of Stress Factors and Life Cycle Assessment. J. Energy Storage 2020, 27, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lai, X.; Gu, H.; Tang, X.; Gao, F.; Han, X.; Zheng, Y. Investigating Carbon Footprint and Carbon Reduction Potential Using a Cradle-to-Cradle LCA Approach on Lithium-Ion Batteries for Electric Vehicles in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 369, 133342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, S.; Lim, S. Identification of Principal Factors for Low-Carbon Electric Vehicle Batteries by Using a Life Cycle Assessment Model-Based Sensitivity Analysis. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 64, 103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, F.; Schütte, M. Life Cycle Assessment of the Energy Consumption and GHG Emissions of State-of-the-Art Automotive Battery Cell Production. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, J.; Cerdas, F.; Heidrich, O. An Integrated Model to Conduct Multi-Criteria Technology Assessments: The Case of Electric Vehicle Batteries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 5056–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lai, X.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Lu, L.; Sun, Y.; Ouyang, M.; et al. A Critical Comparison of LCA Calculation Models for the Power Lithium-Ion Battery in Electric Vehicles during Use-Phase. Energy 2024, 296, 131175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Garcia, R.; Kulay, L.; Freire, F. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium-Ion Batteries for Electric Vehicles Addressing Capacity Fade. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Du, C.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Shen, X.; Wang, D.; Yu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Gao, D.; Yin, Y.; et al. A Strategy to Assess the Use-Phase Carbon Footprint from Energy Losses in Electric Vehicle Battery. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 460, 142569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Shi, M.; Hu, X.; Yang, H.; Yan, X. Comparison of Life Cycle Assessment of Different Recycling Methods for Decommissioned Lithium Iron Phosphate Batteries. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess 2024, 68, 103871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Ma, Q.; Xie, J.; Xia, Z.; Liu, Y. Environmental Impact and Economic Assessment of Recycling Lithium Iron Phosphate Battery Cathodes: Comparison of Major Processes in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 203, 107449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, B.; Tang, Y.; Evans, S. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Recycling Technologies for Ternary Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 389, 136008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallitsis, E.; Korre, A.; Kelsall, G.H. Life Cycle Assessment of Recycling Options for Automotive Li-Ion Battery Packs. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 371, 133636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinne, M.; Elomaa, H.; Porvali, A.; Lundström, M. Simulation-Based Life Cycle Assessment for Hydrometallurgical Recycling of Mixed LIB and NiMH Waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 170, 105586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimaitis, J.; Allen, S.; Vagg, C. Are Future Recycling Benefits Misleading? Prospective Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Ind. Ecol. 2023, 27, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douziech, M.; Besseau, R.; Jolivet, R.; Shoai-Tehrani, B.; Bourmaud, J.-Y.; Busato, G.; Gresset-Bourgeois, M.; Pérez-López, P. Life Cycle Assessment of Prospective Trajectories: A Parametric Approach for Tailor-Made Inventories and Its Computational Implementation. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolivet, R.; Clavreul, J.; Brière, R.; Besseau, R.; Prieur Vernat, A.; Sauze, M.; Blanc, I.; Douziech, M.; Pérez-López, P. Lca_algebraic: A Library Bringing Symbolic Calculus to LCA for Comprehensive Sensitivity Analysis. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess 2021, 26, 2457–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutel, C. Brightway: An Open Source Framework for Life Cycle Assessment. JOSS 2017, 2, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, P.J.; Björklund, A. Futura: A New Tool for Transparent and Shareable Scenario Analysis in Prospective Life Cycle Assessment. J. Ind. Ecol. 2022, 26, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigné, Y.; Gutiérrez, T.; Gibon, T.; Schaubroeck, T.; Popovici, E.; Shimako, A.; Benetto, E.; Tiruta-Barna, L. A Tool to Operationalize Dynamic LCA, Including Time Differentiation on the Complete Background Database. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardellini, G.; Mutel, C.L.; Vial, E.; Muys, B. Temporalis, a Generic Method and Tool for Dynamic Life Cycle Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.; Li, L.; Yu, S. An Innovative Eco-Design Approach Based on Integration of LCA, CAD\CAE and Optimization Tools, and Its Implementation Perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- César, J.C.; Ortiz, J.C.; Ochoa, G.V.; Restrepo, R.R.; Nuñez Alvarez, J.R. A New Computational Tool for the Development of Advanced Exergy Analysis and Lca on Single Effect Libr–H2o Solar Absorption Refrigeration System. Lubricants 2021, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, V.; Mamounakis, I.; Seitaridis, A.; Tagkoulis, N.; Kourkoumpas, D.-S.; Iliadis, P.; Angelakoglou, K.; Nikolopoulos, N. An Integrated Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Costing Approach towards Sustainable Building Renovation via a Dynamic Online Tool. Appl. Energy 2023, 334, 120710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agavanakis, K.; Quitard, R.; Kousias, N.; Mellios, G.; Elkaim, E. Driving Sustainability in Logistics Value Chains: A Telematics Data Hub Implementation for Accurate Carbon Footprint Assessment and Reporting Using Global Standards-Based Tools. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 3018, 020058. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdas, F. Concept Development: Integrated Computational Life Cycle Engineering for Traction Batteries. In Integrated Computational Life Cycle Engineering for Traction Batteries; Sustainable Production, Life Cycle Engineering and Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 87–128. ISBN 978-3-030-82933-9. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Innocenti, E.; Guadagno, M.; Berzi, L.; Pierini, M.; Delogu, M. A Review of Computational Methods and Tools for Life Cycle Assessment of Traction Battery Systems. Eng. Proc. 2025, 85, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025085010

Innocenti E, Guadagno M, Berzi L, Pierini M, Delogu M. A Review of Computational Methods and Tools for Life Cycle Assessment of Traction Battery Systems. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 85(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025085010

Chicago/Turabian StyleInnocenti, Eleonora, Maurizio Guadagno, Lorenzo Berzi, Marco Pierini, and Massimo Delogu. 2025. "A Review of Computational Methods and Tools for Life Cycle Assessment of Traction Battery Systems" Engineering Proceedings 85, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025085010

APA StyleInnocenti, E., Guadagno, M., Berzi, L., Pierini, M., & Delogu, M. (2025). A Review of Computational Methods and Tools for Life Cycle Assessment of Traction Battery Systems. Engineering Proceedings, 85(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025085010