1. Introduction

The term MPA (marine protected area) was first used in 1954 in London at the International Convention for the Prevention of Hydrocarbon Pollution of Marine Waters. Following this day, governments and communities became aware of the need of biodiversity conservation.

MPAs are defined by the regions at sea whose goal is to conserve and safeguard marine organisms that are considered sensitive or of biological significance.

They have been tools of maritime defense since that time. At the start of the 2000s, their global population has been growing [

1].

The existence of pro-connected pooling networks characterizes West Africa’s western coastline zone [

2].

These are cold ascending currents that rise to the surface, carrying nutrients that are normally present exclusively on the seafloor [

3]. This phenomenon is accompanied with fluviatile inputs rich in sediments from the Senegal and Gambia rivers, which flow into the same location. Because of the confluence of these two criteria, this coastal area is classified as an ecoregion or an unusual geographical location due to its unique characteristics.

It is critical to consider this area as an ecological continuity that extends beyond the territorial or political boundaries of the marine protected area, simply because migrations of birds from the northern hemisphere or the circulation of schools of fish contribute punctually to enriching this environment; thus, taking seasonal migrations of species into account is essential [

4].

Overexploitation of fish resources for commercial reasons is one of the dangers. This pressure will have the unintended consequence of disrupting the food chain.

Because of its popularity and influence, it is a grand example of how biodiversity protection may be boosted. Furthermore, it is particularly essential that local people utilizeit to safeguard their ancestors’ lands.

The RAMPAO is a structure that protects two million marine and coastal hectares; there are over 27 protected members of this network, which protects species found in diverse maritime locations where the network is active.

RAMPAO has significantly contributed to the improvement in MPA management efficiency over the last ten years, including, among other things, the networking of a set of representative MPAs, the rehabilitation and preservation of certain wildlife species, the interchange and mutual learning of network members, and the rehabilitation and restoration of certain critical habitats, as well as assistance for functional MPAs that achieve the conservation objectives that have been allocated to them.

2. Background of the RAMPAO

Indicating the prevalence of migratory species, shared transboundary habitat resources, and the mobility of users, notably fishermen, in the subregion, marine and coastal conservation stakeholders rapidly recognized the need to address coastal zone and resource management at the subregional level [

5]. To ensure the protection of the structure and functions of marine and coastal ecosystems at the regional level, a collaborative approach is required (Jennings, 2004).

The various groups of stakeholders engaged created a regional strategy for MPAs in 2002. The shared goal is a cohesive network of marine protected areas in West Africa, maintained by strong institutions in a participatory way that appreciate natural and cultural diversity in order to contribute to the region’s sustainable development [

6].

Through the signature of a general policy declaration by 10 ministers in responsibility of the environment, protected areas, and fisheries in seven countries in 2003, this regional plan swiftly gained considerable support from the political authorities of the nations concerned (Cape Verde, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Mauritania, and Senegal).

The Regional Network of Marine Protected Areas in West Africa (RAMPAO) was officially established in Praia, Cape Verde in 2007 as part of the execution of this regional plan. RAMPAO was therefore established as a consequence of the combined efforts and desire of the subnational regions and regional actors, while reacting concretely to the numerous international recommendations and promises made by the states in the context of biological conservation.

RAMPAO obtained official recognition from the authorities of the seven states in 2010 through the signing of a declaration of formal recognition of the network by fifteen ministers, allowing it to establish the network’s institutional credibility and promote its value as a contribution to the implementation of the states’ international commitments [

7].

Several studies on the network’s institutional, organizational, and financial autonomy were undertaken in 2015, acknowledging the necessity to strive toward its institutional, organizational, and financial autonomy [

2]. Following their deliberations, the network members decided to form a foreign association under Senegalese law and devised a timeline to finish the formation procedure.

RAMPAO has significantly contributed to the development of MPA management efficiency over the last 10 years, including, among other things, the networking of a set of representative MPAs and the rehabilitation and restoration of specific important habitats, the sharing and mutual learning of network members, as well as support for functional MPAs that achieve the conservation objectives that have been set to them [

3].

3. The benefits of RAMPAO

RAMPAO’s contributions to the conservation of West African marine protected areas may be divided into two categories [

3].

Social benefits: Individuals and the gathering of capacities of managers of marine protected areas benefit socially in a variety of ways, including the development of management plans, the development of business plans, marine surveillance, shared governance, exchanges, mutual reinforcement, economies of scale in terms of training, and meetings, collaborating on obstacles and making progress in a group setting.

Ecological advantages include: the network’s coverage of two million marine and coastal hectares, the protection of more than 27 sites and network members, the preservation of species that grow in diverse maritime areas where the network is active, and the movement of species. The network allows for the preservation of a sample of the ecosystem, as well as the defense of multiple samples of the same ecosystem.

A network must satisfy four requirements, according to the US Interdisciplinary Partnership on Ocean Coastal Studies:

It must have adequate connection;

It must be consistent with conservation aims and (species, habitats, heritage, etc.);

It must be reflective of the diversity of species and habitats, as well as of the ecosystem;

Conservation objectives (species, ecosystems, heritage…) should be representative of the range of settings experienced, and have a strong conservation return based on costs and activities in balance.

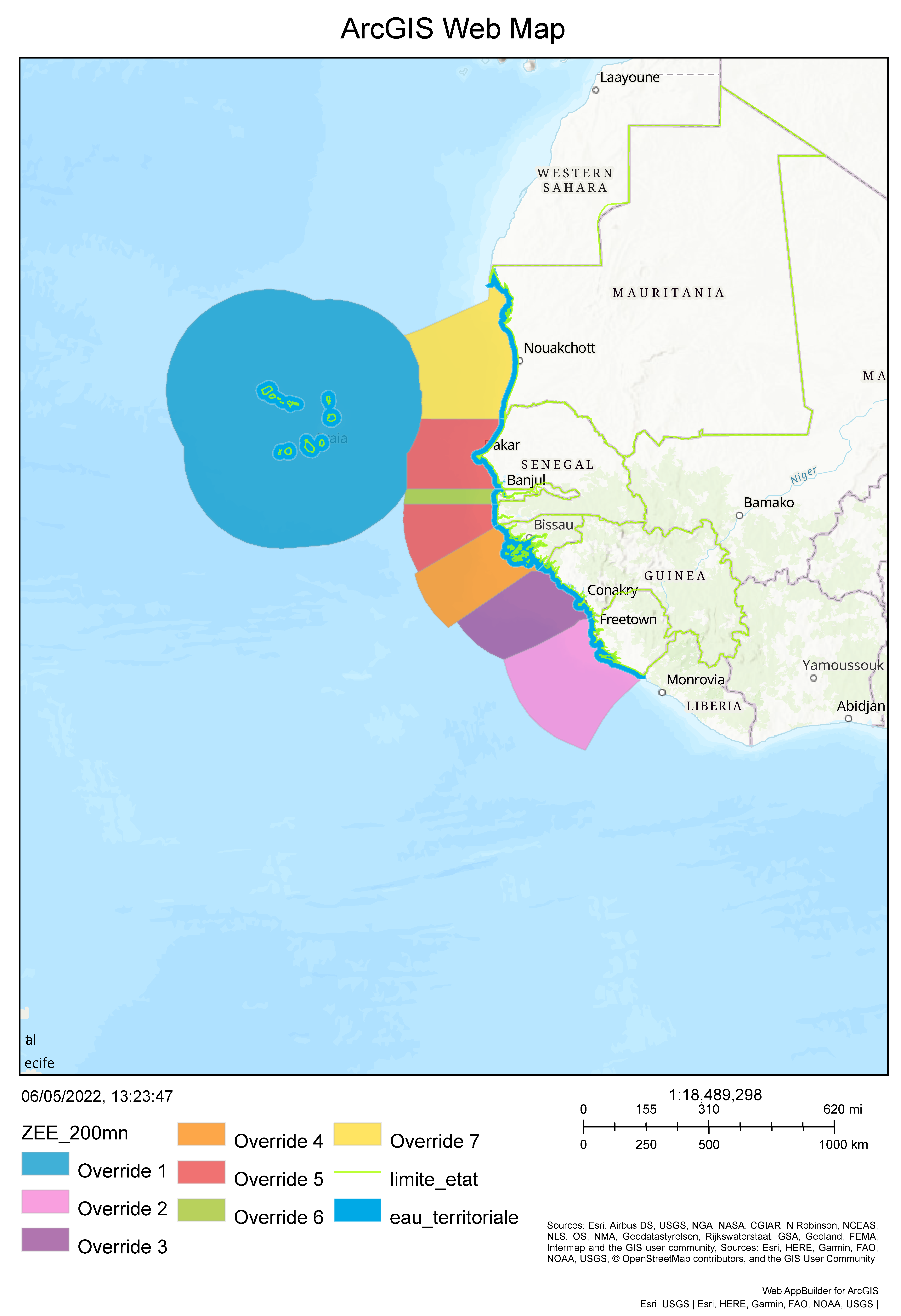

The West African maritime eco region extends over 3500 km of coastline and now includes seven nations, and faces a variety of difficulties (See

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

RAMPAO is made up of national parks, nature reserves, community marine protected areas, wetlands, wildlife sanctuaries, and indigenous and community heritage areas.

The areas of community and indigenous heritage are more than thirty MPAs have been established throughout the subregion in the previous two decades with the assistance of states and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Protected fishing areas (zones de pêche protégée—ZPP) are another form of MPA in Senegal, beside with artificial reef immersion zone (ZIRA), regulated exploitation zone, no-take zone, and zone of fishing, which were established in Senegal under the PRAO project (Regional Fisheries Program in West Africa). These MPAs are distinguished by a co-management governance model (Failler et al., 2018).

In 2009, the regional network of marine protected areas (MPAs) in West Africa (RAMPAO) included 19 MPAs from 4 countries out of the 24 officially recognized MPAs in 6 of the 7 countries of the West African marine ecoregion.

In 2015, part of the seven nations’ territorial seas were protected owing to the RAMPAO’s 32 MPAs, which covered an area of 2,188,826 hectares (see

Table 2 below).

In 2018, RAMPAO included 32 officially recognized MPAs in the western African marine ecoregion [

1].

RAMPAO is made up of National Parks, Nature Reserves, Community Marine Protected Areas, Wetlands, Wildlife Sanctuaries, and Indigenous and Community Heritage Areas.

4. RAMPAO’s Activities and Objectives

The goal of RAMPAO’s strategic orientations and work plan is to support, in a sufficient and harmonic manner, the efforts made by RAMPAO’s many actors to enhance the coherence and functionality of the network in order to accomplish the specified objectives.

At the official website, (

https://www.rampao.org/Nos-activites.html?lang=fr (accessed on 2 September 2021)) of RAMPAO, we encountered that the current 2020–2024 work plan has been focused on consolidating the network’s successes and development since its inception in 2007, specifically on: increasing the efficacy of MPA administration; institutional and financial strengthening of the network; and the services provided to its members.

To guarantee: the collaboration of a coherent set of MPAs representative of critical ecosystems and habitats required for the dynamic functioning of environmental processes essential for the regeneration of marine and coastal natural resources, the rehabilitation and reconstruction of critical habitats, and the preservation of biodiversity;

The maintenance and sustainable use of the West African maritime and coastal ecoregion’s biodiversity and ecosystem services, as well as its heritage, natural, and cultural resources, for the benefit of the region’s people, particularly local communities, via a functional regional network of MPAs.

Support: networking and synergies between managers on the one hand, and managers and other technical players involved in the administration of MPAs in the region on the other.

The promotion of exchange and mutual learning among association members and other actors involved in the management of MPAs in the region, activities likely to make the region’s MPAs more functional and operational in the long term;

Ensuring connectivity and resilience, particularly in the face of climate change impacts;

Increasing knowledge of the ecological and socioeconomic importance of the region’s MPAs and the biological resources they contain, as well as ways and means of fairly and equitably sharing the benefits of their use, particularly with local populations;

Promotion of the establishment and inclusion of additional MPAs in the region’s network.

5. RAMPAO’s SWOT

According to [

3], the health status of the network’s protected areas is one of the network’s biggest strengths. They are home to numerous animal and plant speciesanda diverse range of environments.

The major opportunity is, above all, the subecological region’s riches. This wealth must be increased and protected. Within their limits, protected zones provide excellent protection. Within their bounds, they provide protection.

Reasoned eco-tourism might aid in the strengthening of local capacities in the face of external demands. The primary risks are many and dispersed. As a result, precisely isolating them is challenging. Managers of maritime protected zones are concerned about industry, oil extraction, and fishing.

Natural dangers are also significant. The table on the next page goes into further information about the key items gleaned from the surveys.

Strengths

Healthy protected areas overall;

Legal framework to build on;

Good involvement of local populations;

Effectiveness and enforceability of protection measures;

Subregional approach;

Present existence of entities and partners;

Working for the promotion of MPAs (RAMPAO, PRCM, NGOs, international cooperation…).

Weaknesses

Low MPA budget;

Low human capacity;

Lack of infrastructure;

Institutional instability;

Instability of MPA funding;

Lack of basic knowledge (habitats, key species, basic MPA of the MPAs, scientific studies…);

Communication still in need of improvement;

Volunteers are not valued enough;

Gaps in coherence, connectivity, and representativeness of the network.

Opportunities

Biological richness of the subregion;

Beneficial effects of MPAs;

Important tourist potential;

Organized and motivated partners acting at the scale of the subregion (PRCM, RAMPAO, NGOs, international cooperation…);

Margin of progression of the network;

RAMPAO is an interesting lobbying tool for the promotion of the network.

Threats

Increase in the pressure;

Anthropic pressure (demography, agriculture, extraction of natural resources…);

Physical phenomena: erosion, invasive species…;

Phenomena accelerated by climate change and human activity;

Increasing exploitation of fishery resources;

Poverty of the populations;

Lack of environmental awareness on the part of the population;

Pollution: offshore oil exploitation.

The proposal, dated 5 July 2021, emphasizes a 2050 vision and a 2030 objective, specifically, “By 2050, biodiversity is appreciated, preserved, restored, and intelligently exploited, preserving ecosystem services, sustaining a healthy world, and delivering benefits important for all people.” The draft frameworks state that there will be “urgent action across society to conserve and sustainably use biodiversity and ensure the fair and equitable sharing of benefits from the use of genetics resources, to put biodiversity on a path to recovery by 2030 for the benefit of planet and people” in the period up to 2030.

The 17 sustainable development goals are the centerpiece of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The 17 goals cover almost all important development themes, including access to education, clean water and renewable energy, infrastructure, industry, agriculture, biodiversity protection, and climate change.

At the United Nations Summit in New York in September 2015, world leaders endorsed “The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” The agenda gives the world a fresh push and direction for moving toward a more sustainable and resilient future. Its 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) aim to strike a balance between the economic, social, and environmental aspects of development. They want to spur action in areas that are vital to the world and humanity during the next 15 years [

8].

In this sense, and according to the SDG, the RAMPAO objective is the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and ecosystem services as well as the heritage, natural, and cultural resources of the marine and coastal ecoregion of West Africa for the well-being of the populations of the region, by particularly local communities, through a functional regional network of MPAs.

6. Conclusions

RAMPAO was established as part of the West African Regional Program for the Conservation of the Marine and Coastal Zone. The goal of this network is to link together the existing maritime protected areas, both biogeographically and humanly: to bring together the administrators of these marine protected areas to debate the issue and to conserve this network as best as possible [

8].

It is a network that has given itself the goal of preserving coherent ecosystems that are critical for the operation of ecological processes in order to protect biodiversity and safeguard the legacy and services of related ecosystems [

6].

It is a network that aims to reach seven West African countries: Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea Sierra Leone, and the Cape Verde Islands.

This network is the result of a long-term effort and was created to put an end to similar problems that marine protected areas face, because they face the same challenges in terms of conservation of marine and coastal resources. They share trans-boundary habitats, crossing of marine borders by marine spaces, and a concerted approach to be able to face all of these problems; and from there, RAMPAO was born.

From 2004 to 2007, ongoing meetings were on the schedule to reflect on the network’s functioning and aims, culminating in 2007 with the network’s official establishment as such during its consultative assembly in Cape Verde.

A regional plan for marine protected areas was created in 2002, prompting political recognition and interest from the Ministers of Fisheries and Environment of the nations involved, who signed a policy statement emphasizing the relevance of this network.

All of these benefits are obviously transferable to RAMPAO. The major advantages now are precisely the social ones. The cohesiveness between the many managers of West African MPAs, national institutions, and foreign partners has improved. Members’ exchange visits have been carried out [

9].

These proved to be fruitful and satisfying for the participants.

Local communities are better heard, and the formation of mixed-management committees allows everyone to be heard. The network has produced substantial synergies between MPAs and among the network’s partners. A similar scenario has been found in the Mediterranean MPA network [

10].

Furthermore, MPAs with low visibility benefit from the RAMPAO, the centralization of data, and data and information enable for an examination of documents at the network size. RAMPAO has one of these responsibilities.

This endeavor stimulates the generation of knowledge, and this job promotes knowledge creation and identifies gaps in fundamental understanding about marine and coastal species, as well as coastal species and ecosystems in the subregion. Benefits are also flowing to the network’s member managers at the operational level. They may, indeed, count on logistical and financial help [

10].

The Secretariat of the Small Grants Program encourages conservation actions and allows managers to carry out certain costly measures.

Finally, one of the axes on which the secretariat has been working for a long time is the strengthening of the capacities of network members through, among other things, papers for managers [

11].