1. Introduction

Forensic digital photography is an essential technique which plays a huge role throughout the entire investigation, including record purposes, crime and medicolegal issues [

1] and it is essential for fair trial [

2,

3,

4]. The documentation of the evidence is a very valuable aspect during crime investigation [

5,

6].

Photographic documentation of injuries, sequelae and traces observed during the legal medical examinations, both of the living and of the corpses, is one of the fundamental parts of the expert’s report and should be carried out whenever possible. It allows recording, with images, the aspects of this evidence at the specific moment of the inspection, preserving its initial aspects that, generally, cannot be observed again in circumstances different from those observed during the first inspection. Therefore, it is necessary that these photographic records have sufficient quality to show what was actually observed, safeguarding the reliability of the evidence and contributing to the correct judgment of the processes in the courts of law [

2,

7,

8].

Quality photographic documentation allows for sharing and discussing the findings with other experts in order to obtain their opinions, thus avoiding the possible need for a second examination of the victim or even an exhumation. It also allows the right of reply, based on the adversarial principle, when there is another expert appointed to monitor the judicial process [

8,

9,

10].

Considering the necessary criteria for good forensic photographic documentation, it is fundamental that forensic experts know what is important for legal professionals regarding photographic documentation in violent death autopsies, seeking to understand what is expected of the photographs that comprise expert reports in order to clarify the facts and assist in decision making in the courts.

Thus, the aim of this study was, through an online questionnaire form, to gain knowledge of the expectations and preferences of those involved in the production and interpretation of evidence, regarding the characteristics of the photographs that are part of the expert reports of violent death autopsies.

2. Materials and Methods

The survey was conducted through an online questionnaire, available on the “Google Forms” platform. The link was forwarded by email and the WhatsApp Messenger® application to 189 law enforcement operators in the city of Porto Velho, RO, Brazil, including eight judges, 55 prosecutors, 30 criminal lawyers and 96 police chiefs, as well as 53 forensic experts, involving 24 medical examiners, three forensic dentists and 26 criminal experts, totaling a target audience consisting of 242 subjects.

The form had six multiple choice questions and two essays. Among the multiple-choice questions, one asked about the role of the professional, and five addressed themes related to the photographs present in expert reports, such as: the color and size of the photographs, the use of evidence marking in photography and the use of explanatory texts in the image captions and what evidence would be important for photographic documentation. In the essay questions, one asked about other important characteristics that were not included in the questionnaire, and in the other, the professional could make any comment that they deemed pertinent.

For descriptive statistical analysis, participants were divided into two groups: Group A—legal practitioners, directly interested in the documented evidence (judges, prosecutors, criminal lawyers and police chiefs); Group B—forensic experts, responsible for producing the photographic documentation of the evidence (medical examiners, forensic dentists and criminal experts).

The exclusion criteria for participation in the research were professionals who do not work in the city of Porto Velho-RO and professionals from areas not related to the core of the research.

As for the Free and Informed Consent, this constituted the first section of the online form, as a requirement to proceed to the questions section of the questionnaire and present the details of the survey. The consent to participate in the research was given when the participant accepted to answer the proposed questions, and was considered complete consent when the participant answered the questionnaire until the end. Total confidentiality of the identity of the research subjects, their contact information and data that allow the correlation between the answers and the people were assured.

3. Results

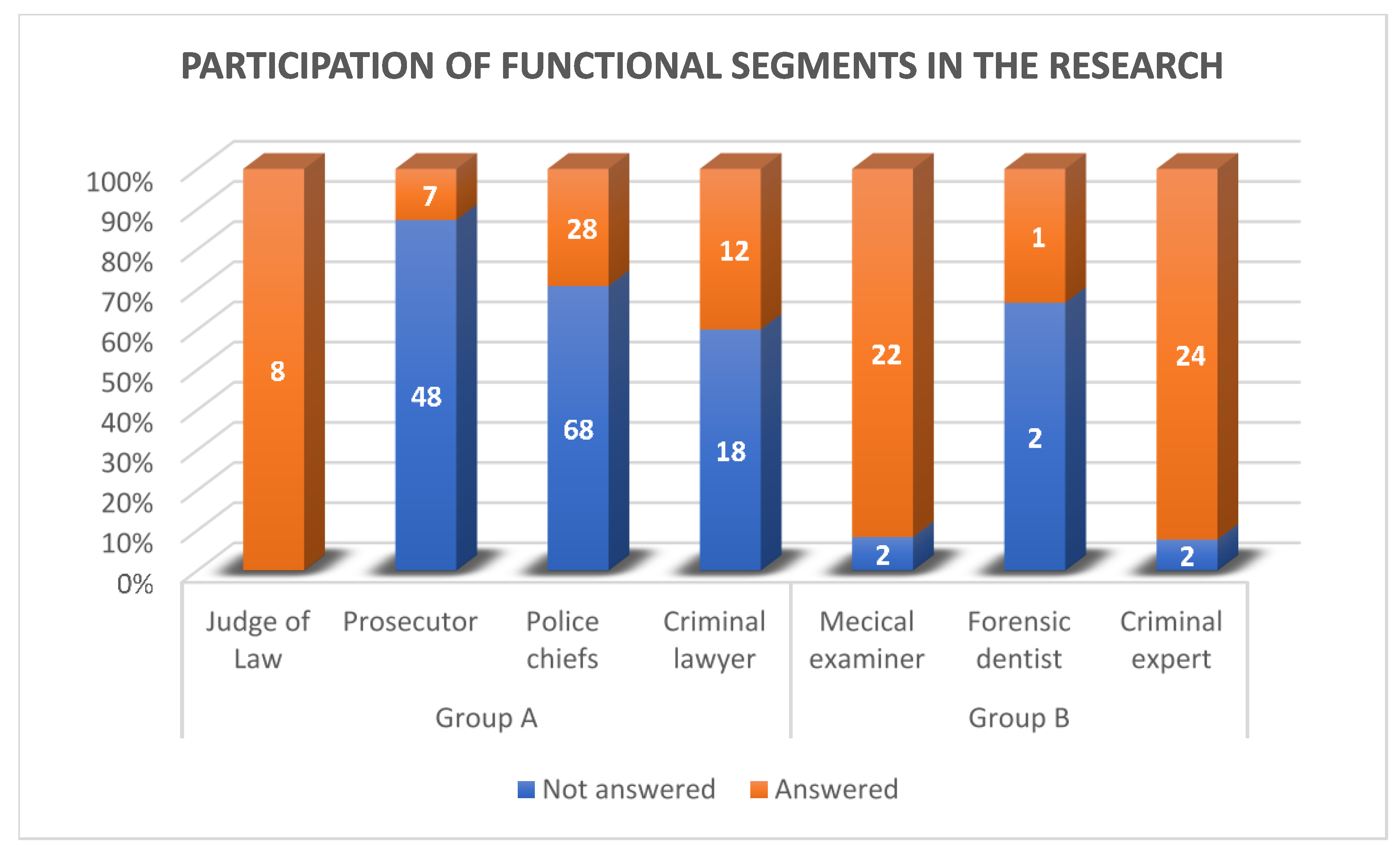

Of the 242 participants who received the survey link, only 102 (42.14%) responded to the questionnaire, distributed as shown in

Figure 1.

The participation of each professional segment is shown in

Figure 2.

Regarding the color of the photographs, the participants were unanimous (100%) in answering that they prefer color photographs in the expert reports of violent death, to the detriment of black and white photographs.

As for the size of the photographs to be included in expert reports, approximately half (50.90%) of the participants in Group A prefer to use large photographs, with dimensions of approximately 20 cm by 30 cm, which would occupy a sheet of A4 paper. However, 78.72% of Group B defend the incorporation of medium-sized photographs, measuring about 10 cm by 15 cm, which would allow the insertion of two images on an A4 sheet, as shown in

Figure 3.

When asked about the tagging or not tagging of evidence in the photographs and the presence of explanatory text in the captions of the images, it was found that most professionals in Group A and Group B prefer that evidence be tagged in the photographs and that there be explanations in the caption below the image (

Figure 4).

Regarding what is important to include in photographs in reports of violent death, most professionals in Group A (81.81%) understand that the reports must contain images of all evidence, both those found in external and internal examinations of the corpse, while in Group B there was a technical tie and only (51.06%) had the same preference (

Figure 5).

Regarding which photographs must necessarily be included in the report, two images were identified as fundamental in the report by both groups: the photograph of the face and the photographs that show the of firearm bullets’ paths, when applicable. Photographs of scars, particular marks and tattoos were identified as relevant for more than half of the professionals in Group A, despite being considered of lesser relevance for professionals in Group B (

Figure 6).

The essay question that allowed for information on which other images would be important for inclusion in the violent death autopsy report, which were not included in the multiple-choice questions, was answered only by the criminal experts. They replied that it would be important to incorporate the images of the crime scene, the clothes and belongings that accompany the corpse and the murder weapon.

4. Discussion

In the practice of forensic medicine, a forensic expert writes legal medicine reports about injuries and deaths, which are used by prosecutors to qualify the crime [

11]. No matter how good a description of a crime scene or a victim’s injuries is, photographs can describe them better and more easily as they freeze time and records the evidence [

12].

Autopsies and forensic cases are increasingly being recorded through photographs, and this practice tends to increase even more as digital photography becomes cheaper and operational procedures become easier [

10]. The ubiquity of digital cameras, especially those built into smart phones, have made capturing images easy, accessible, quick and free, offering a spectrum of perception, interpretation and execution [

13,

14,

15]. The forensic photographer must seek training to develop the skills necessary to record these injuries, producing high-quality photographs [

3,

16,

17]. Camera, lens, lighting, background and certain photographic techniques are among the factors considered to achieve precise images [

18,

19]. With the necessary technical knowledge, these photographic records must be made in accordance with forensic standards [

20], since only if the conditions are reproducible can photographs be considered adequate recording tools [

21].

Current guidance on evidence in criminal proceedings in Brazil, adduced by the Brazilian Code of Criminal Procedure [

22], directs the experts to include in the reports the photographic documentation of the traces presents in the criminal body and of all the injuries found in the corpse. It is essential that each photograph is taken in a standardized way to improve judicial decision [

23,

24,

25]. However, there is no direct guidance from the government on the issues of obtaining these photographs. Nor is there any existing published protocol that describes techniques for optimizing photographs or for appropriate positioning for photographing each body part and systematically evaluating the effectiveness of the protocol [

26,

27,

28].

The lack of this standard protocol allows forensic experts to incorporate photographs that, in practice, may not comply with one of the main objectives of photographic documentation, which is to facilitate the visualization and understanding of medicolegal details important to the case.

Photographs incorporated in reports must always be in color, as shown in the survey results. One of the signs used to estimate how long ago a lesion was produced is related to the different colors that this lesion will present over time. This criterion in medicolegal expertise is a fundamental issue that can lead to misinterpretations regarding the time of production of the lesions. If the expert is called to clarify doubts in the courts, he may be faced with the need to estimate the evolution time of an injury from a photographic record. In these cases, the color of the photograph can definitely influence the final verdict [

9]. They also need to include the forensic scale, especially in close-up photographs, to estimate their size [

10]. A study to determine the quality and nature of photographic images submitted to the National Injuries Database in the UK reported that only 24% were properly labeled with an index, while 64% had no measurement scales [

29]. The use of electronic flash, which has a color temperature similar to daylight, is recommended to avoid color distortions and prevent loss of focus due to camera shake [

30].

Regarding the detailing of evidence in the images, both groups prefer that the photographs include an evidence tag on the image itself, and that they should contain explanatory text in the captions below the images. Tags are visual cues used to highlight important aspects of images that should be observed more closely, especially when your visualization is not noticeable enough. These tags facilitate the understanding of the photographed evidence by eliminating the subjectivity of the description. An explanatory text must be included in the caption of those images where the size of the information cannot be inserted in the body of the image, due to the complexity of the tags or explanations with long text.

The photographic documentation of the firearm bullets’ path and the inclusion of these images in the reports was considered essential by more than 80% of the participants, in both groups of professionals participating in the research. The inclusion of these images favors the authorities’ understanding of the event’s dynamics. (

Figure 7).

The other answers obtained in the form were divergent between the groups of professionals who participated in the research, revealing that the legal practitioners have different expectations to those presented by the forensic experts, responsible for producing the evidence, in relation to various aspects of photographic documentation. This disagreement can be detrimental to the proper interpretation and judgment of the expert evidence and can be explained by the lack of a protocol to standardize these photographs, which makes it difficult to obtain photographic documentation of evidence in autopsies of violent death. This certainty can be seen in recent research on photographic art in autopsies of violent death, carried out at the Dr. José Adelino da Silva Medical Institute, in the city of Porto Velho, RO, Brazil, where the study found that more than half (52.6%) of the photographs present in the reports were technically unfeasible [

31].

Approximately half of Group A professionals prefer to include full-size photographs. This choice of large photographs in the expert report is disadvantageous in terms of cost versus benefit, as it does not mean that a large image has more quality. When it comes to digital images, more important than photo size is the production of high-resolution images. This ensures an optimal level of detail and sharpness when displaying evidence, no matter how large the photograph is. To directly incorporate the expertise text, it must be included in the reports in the size of a postcard, that is, 4 by 6 inches (10 cm by 15 cm), allowing the insertion of two images on the same sheet. This size, in addition to reducing the amount of paper needed to print the expert report (in cases where a physical print is required), is sufficient for detailing and sharpening the evidence [

8].

Processing the crime scene is not part of the routine of Brazilian medical examiners and forensic dentists, leaving the belongings and the murder weapon, when recovered, in the possession of forensic experts for use in the due expert procedures. Therefore, photographic documentation of the crime scene and the murder weapon is not typically incorporated into violent death autopsies. These images are included in criminal forensic reports. Occasionally, when it is necessary to compare certain evidence found on the corpse and relate it to the murder weapon, the forensic experts can go to the Institute of Forensic Medicine morgue at the time of the autopsy and present the weapon for confrontation; in these cases, the weapon is also photographed in a way that demonstrates compatibility and causality with the evidence found in the body.

All evidence found in the external and internal examination of the corpse, however insignificant it may appear, must be documented with photographs. It is also clear that the absence of injuries, sequelae or traces must be documented, as it is the best way for the expert to demonstrate that he was careful to look for evidence, having not, however, found it [

8].

Despite photographing everything, the aim of the authors of this article is to include in autopsy reports of violent death only the relevant photos that prove the causal link of death. All other photographs are filed on the institute’s server and are available for review by the authorities if requested. Photographs of the face, scars, tattoos and particular signs are only included when the body is unknown or unidentified until delivery of the final report.

Thus, it is essential that there is, in the forensic practice of official expert agencies, a standard operational protocol that regulates photographic documentation procedures in forensic autopsies, in a practical and economically viable way, in order to ensure the reliability of the evidence material [

31]. The protocol must be up-to-date regarding the preferences of legal practitioners in relation to the details of the photographs that are present in the expert reports, so that these fulfill their main role.

5. Conclusions

This research revealed that the inclusion of color photographs in expert reports is indispensable for all research participants, as it can influence the final verdict in the judgments. The tagging of evidence in the images and the inclusion of explanatory text in the captions was also pointed out as something important, as was an image simulating the firearm bullets’ path, if any. Regarding the other aspects, it can be concluded that the opinion of the participants was divergent between the groups of research professionals, revealing that the legal practitioners have different expectations to those of official experts in relation to expert evidence, which can be detrimental to the proper interpretation and judgment of evidence in the courts.

Such results are important for guiding forensic experts in the preparation of their reports, guiding them to include quality photographs in the reports that will be used for the proper judgment of cases of violent death. More detailed regulation and a standard operational protocol are required for photographic documentation to be included in reports produced by official expertise.

Ethics statement: Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to fact that The Free and Informed Consent Form was the first section of the online form, and was a requirement to access the questions section of the questionnaire and present the details of the research. Total confidentiality of the identity of the research subjects, their contact information and data that would allow the correlation between the answers and the people were assured.

Consent statement: The consent to participate in the research was given when the participant accepted to answer the proposed questions, and was considered complete consent when the participant answered the questionnaire until the end.