Diagnosis and Management of Acanthamoeba Keratitis: A Continental Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

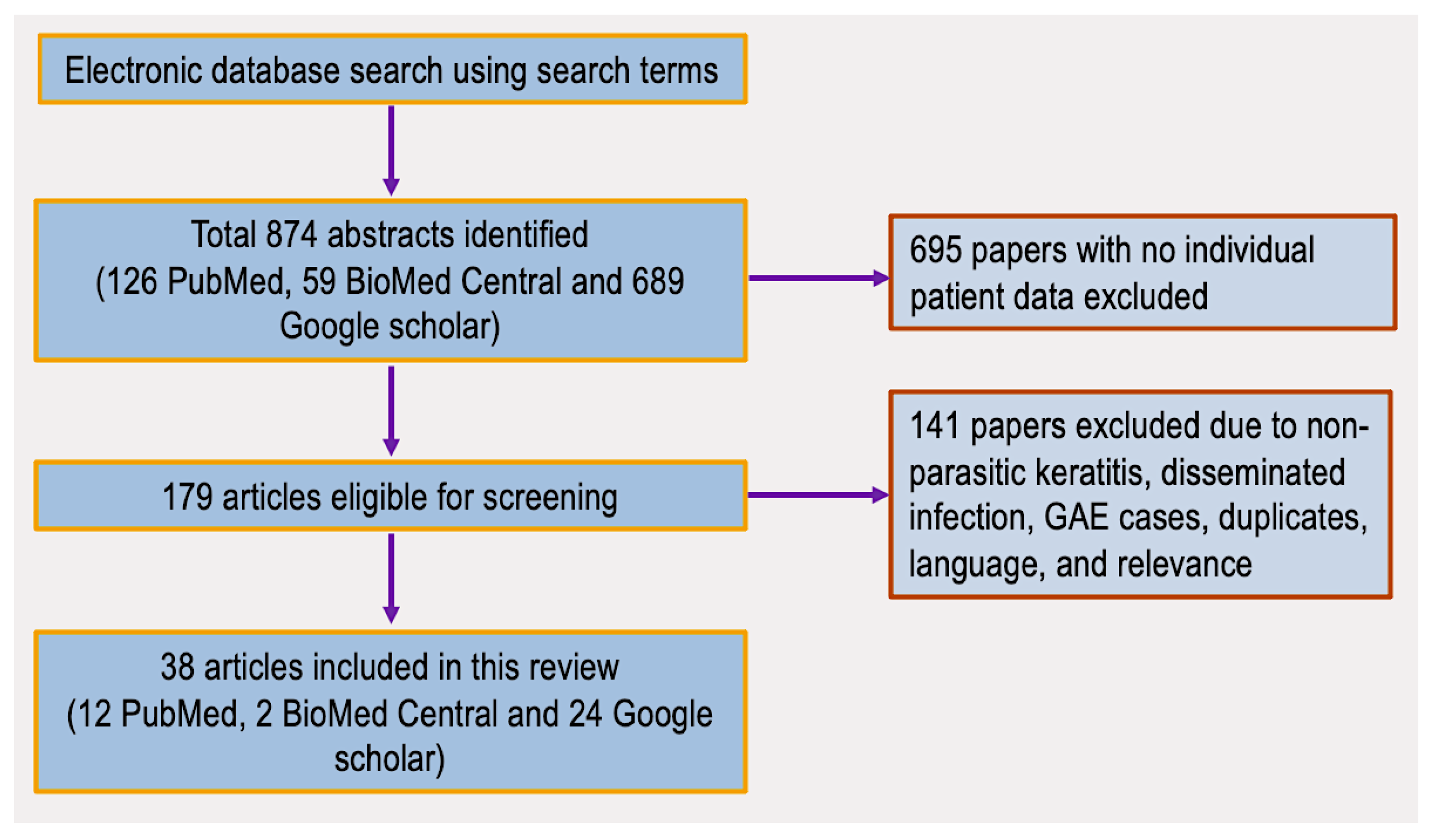

2.1. Literature Search Results

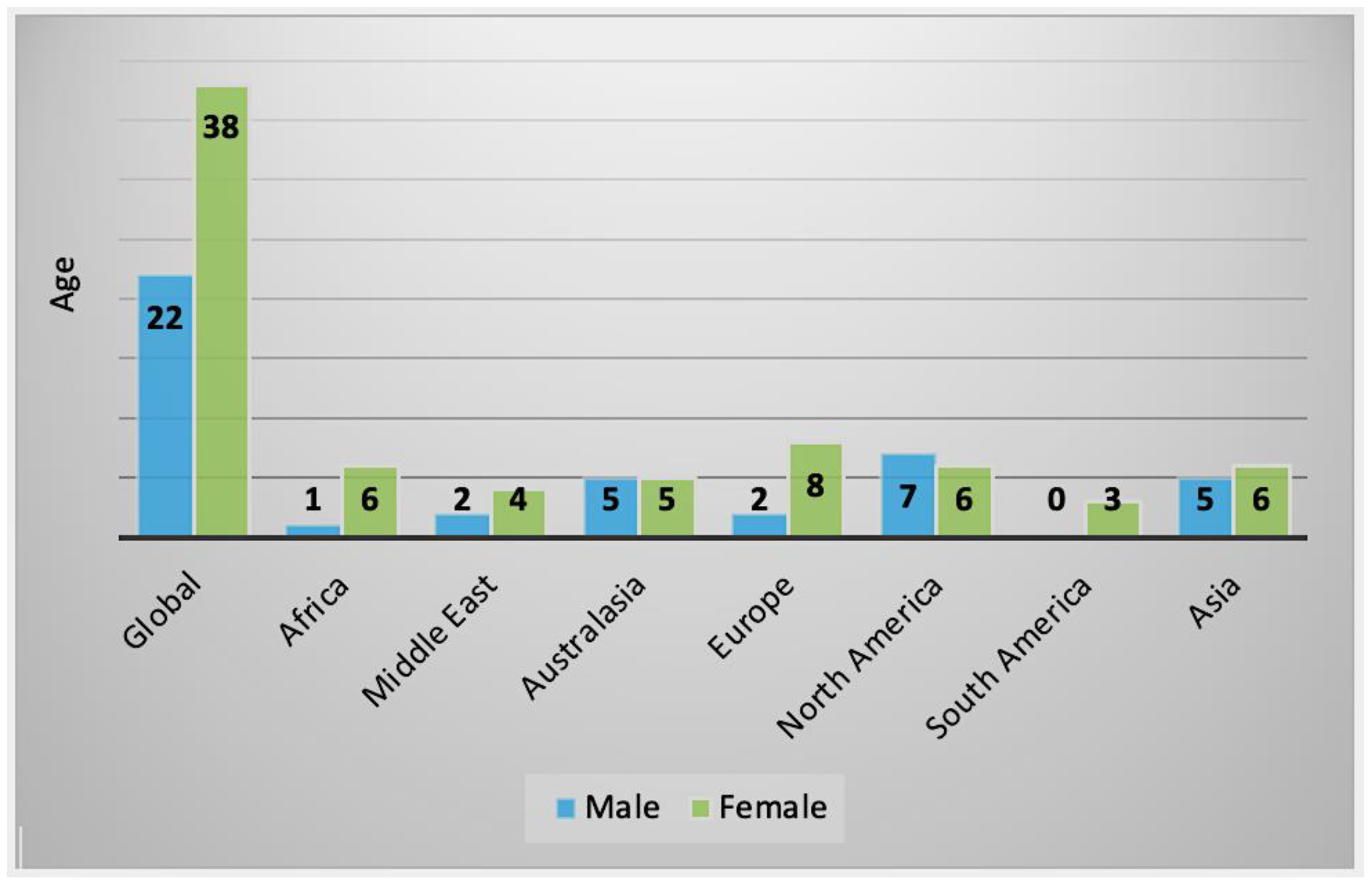

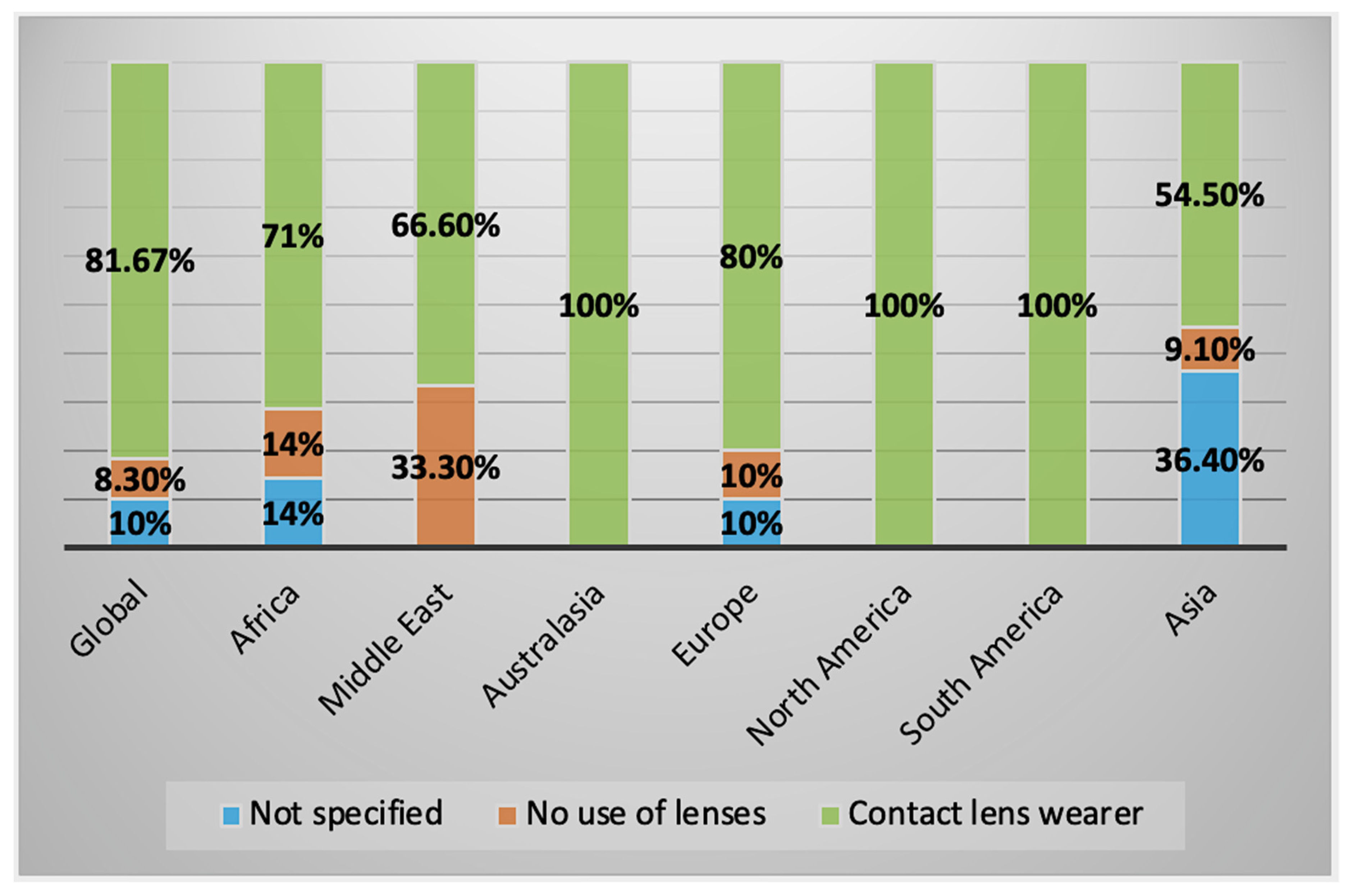

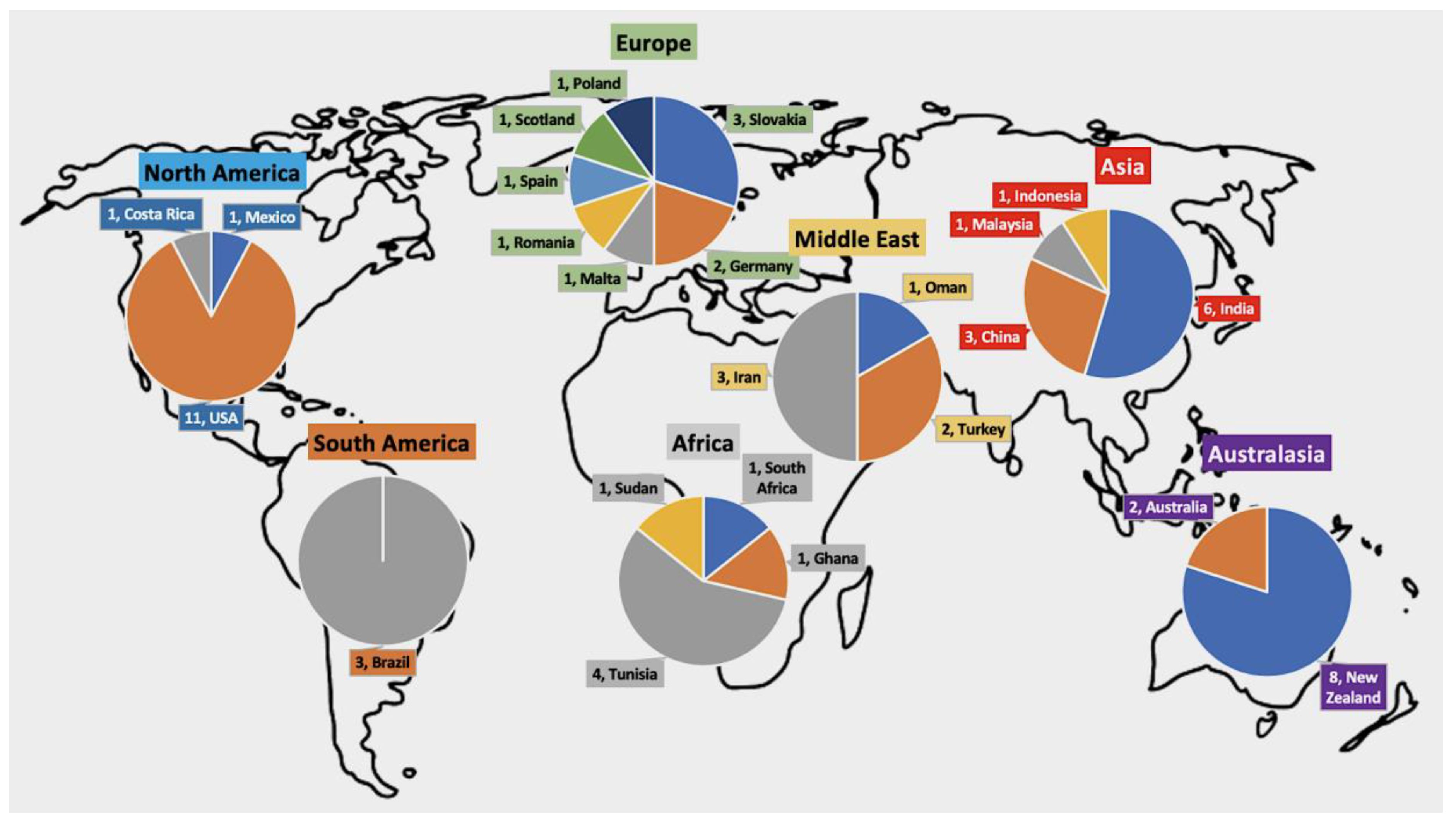

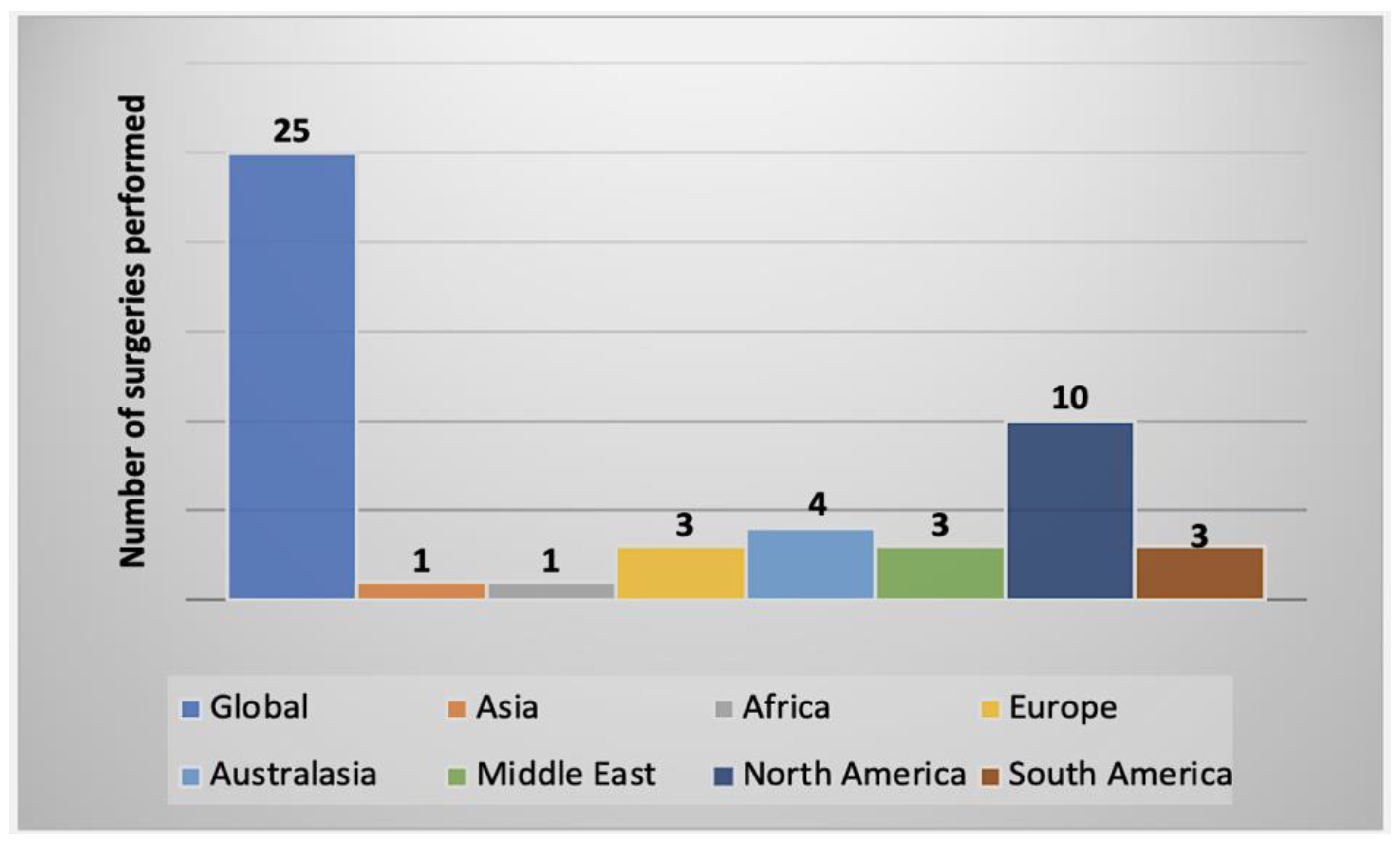

2.2. Summary of AK Cases Reported Worldwide

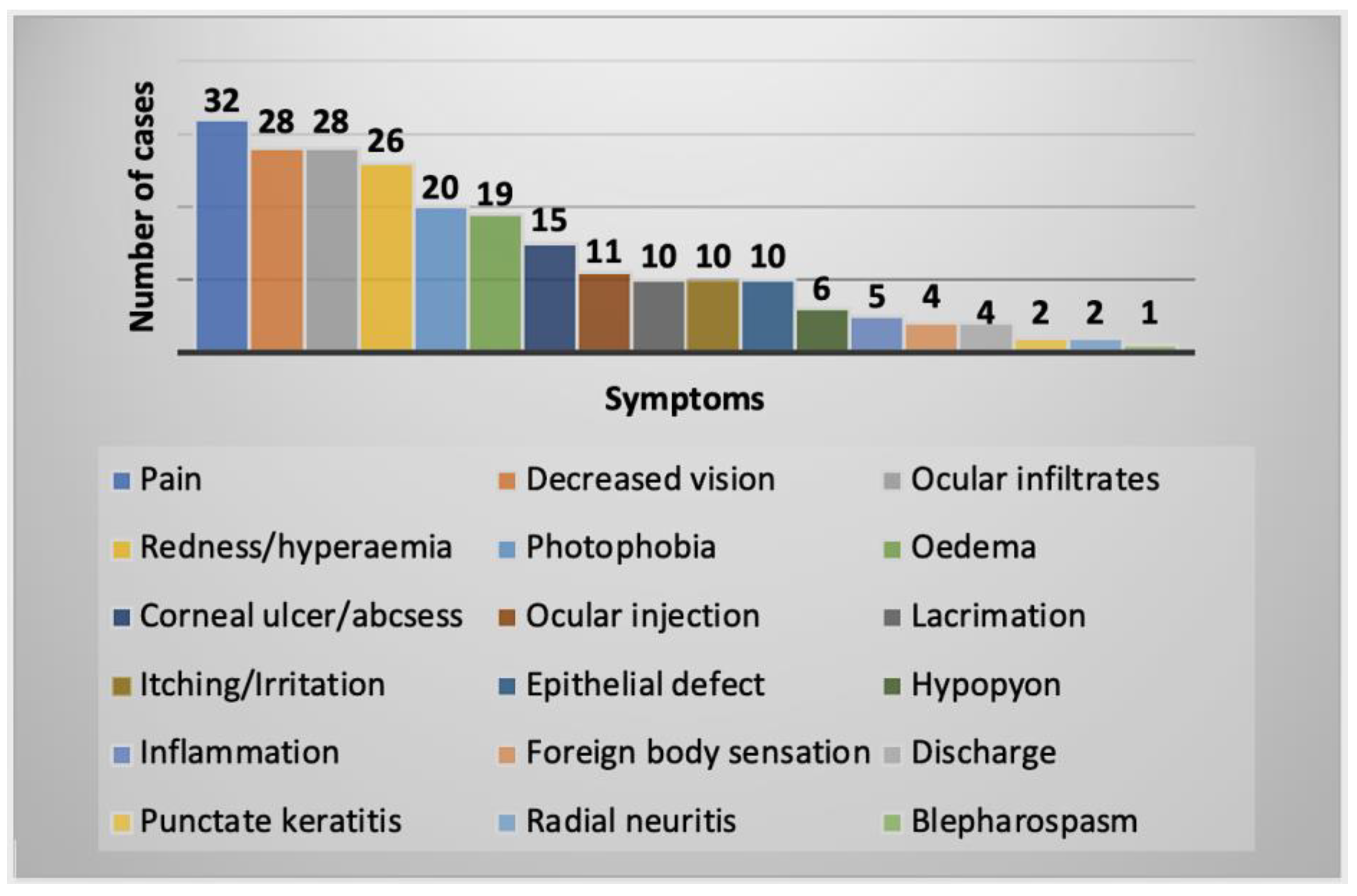

2.2.1. Clinical History and Symptoms

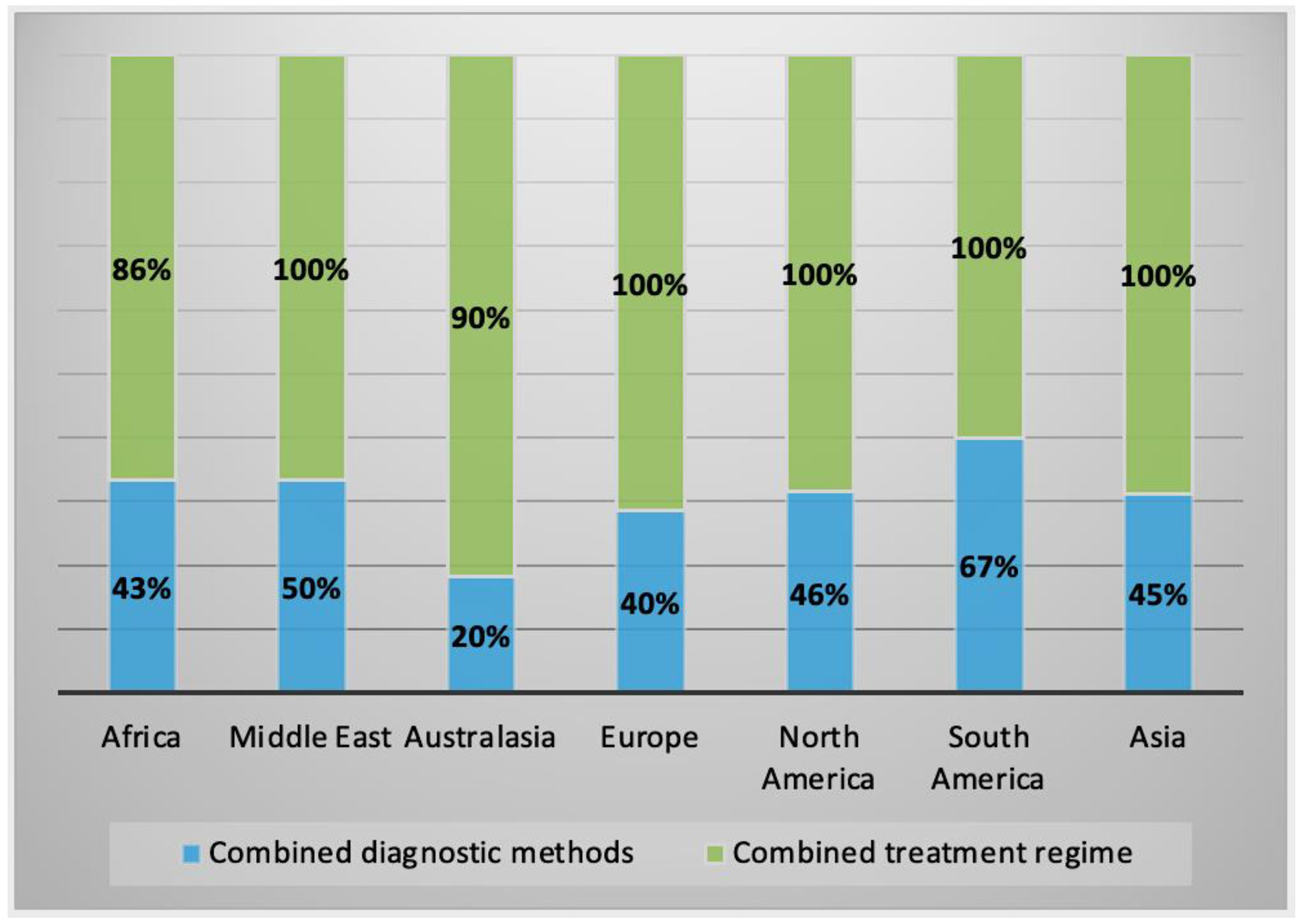

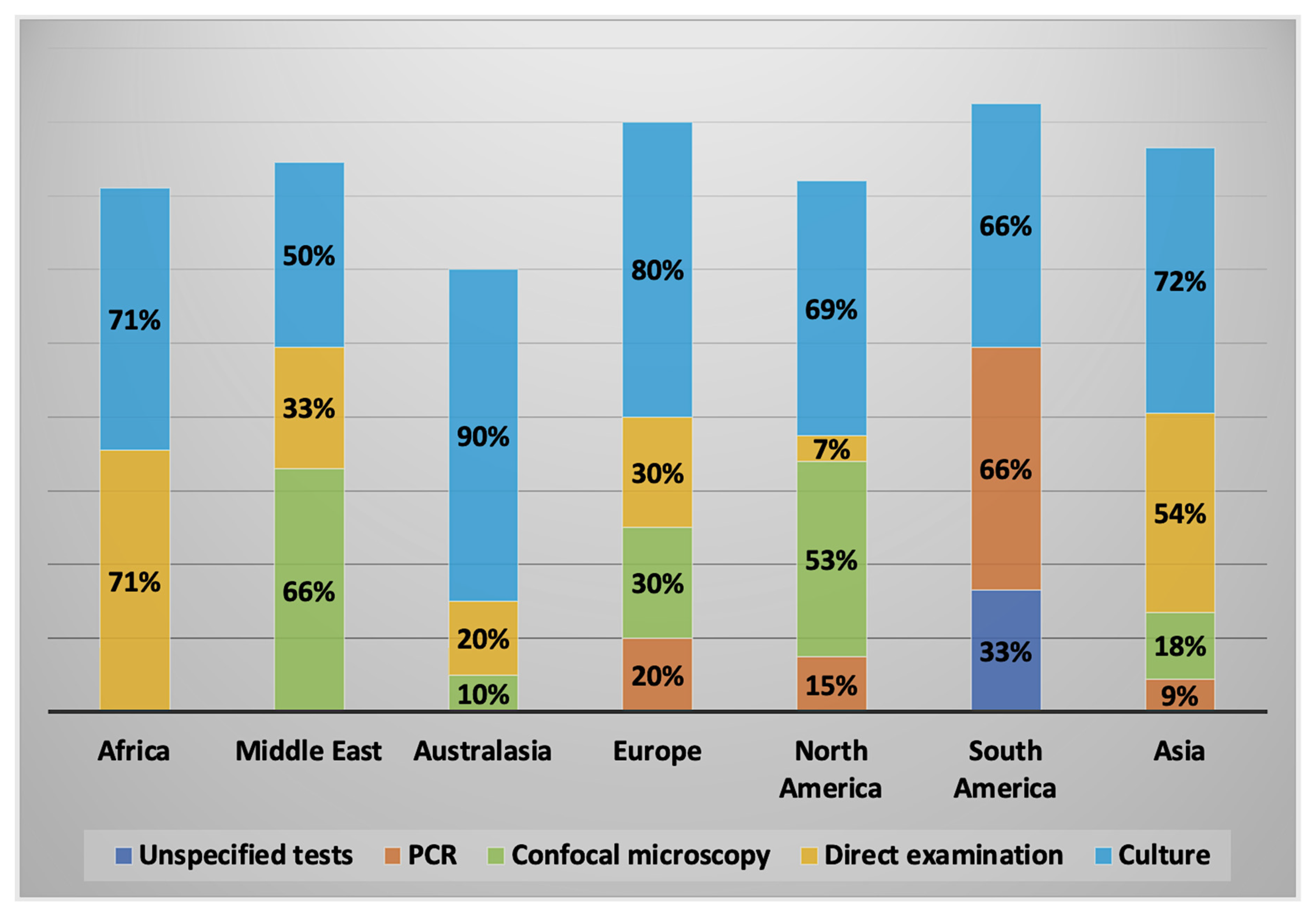

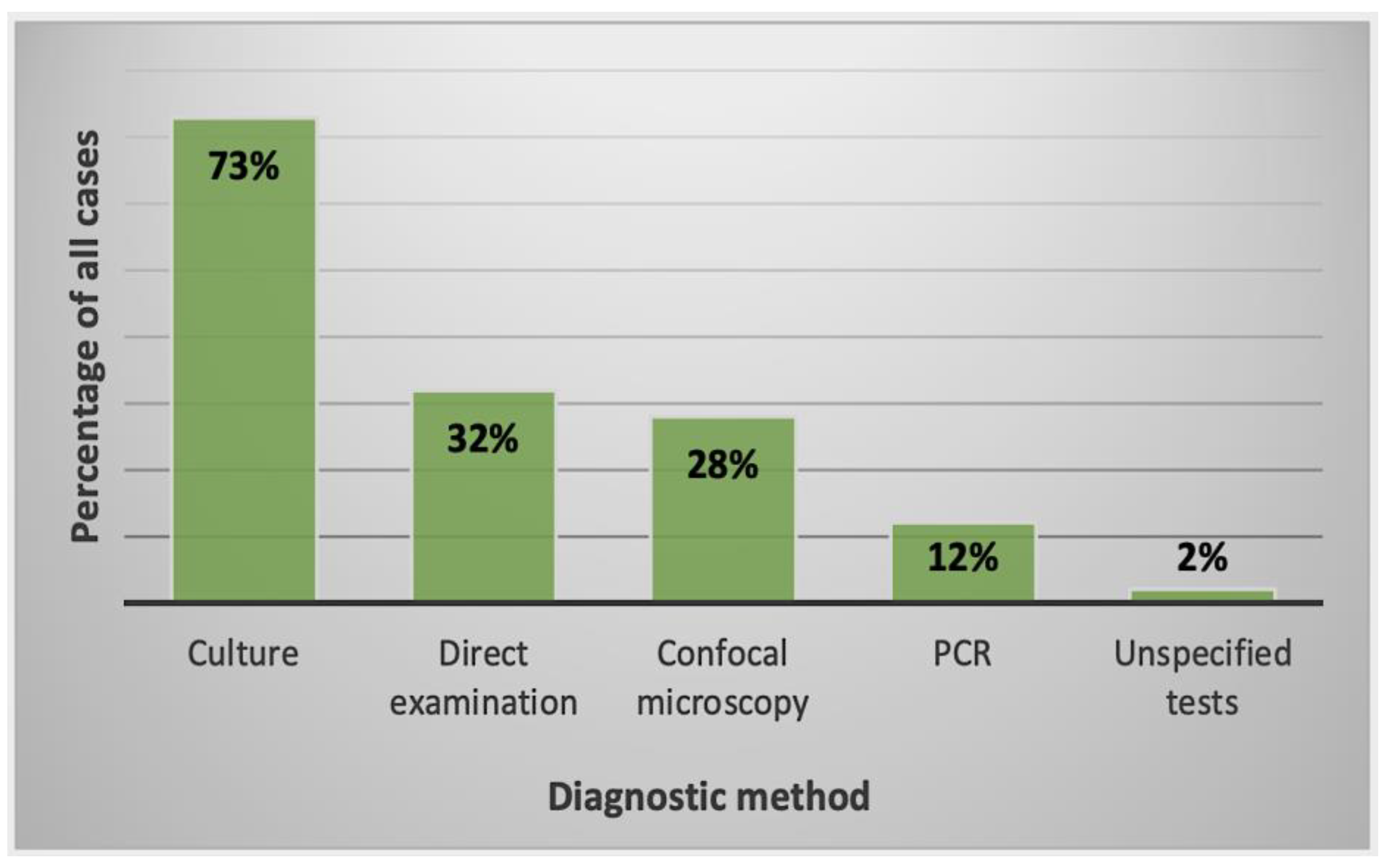

2.2.2. Diagnostic Methods Used

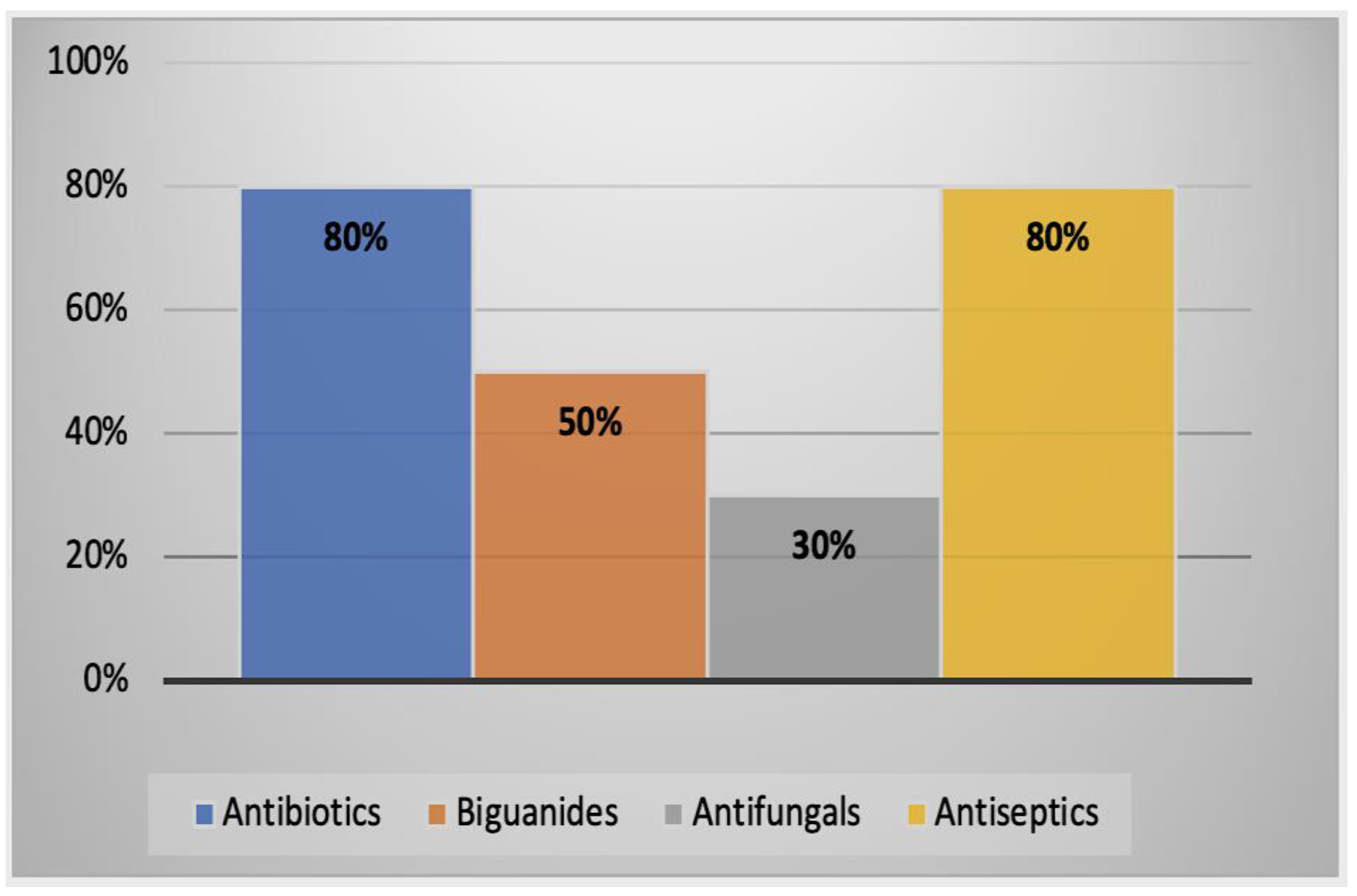

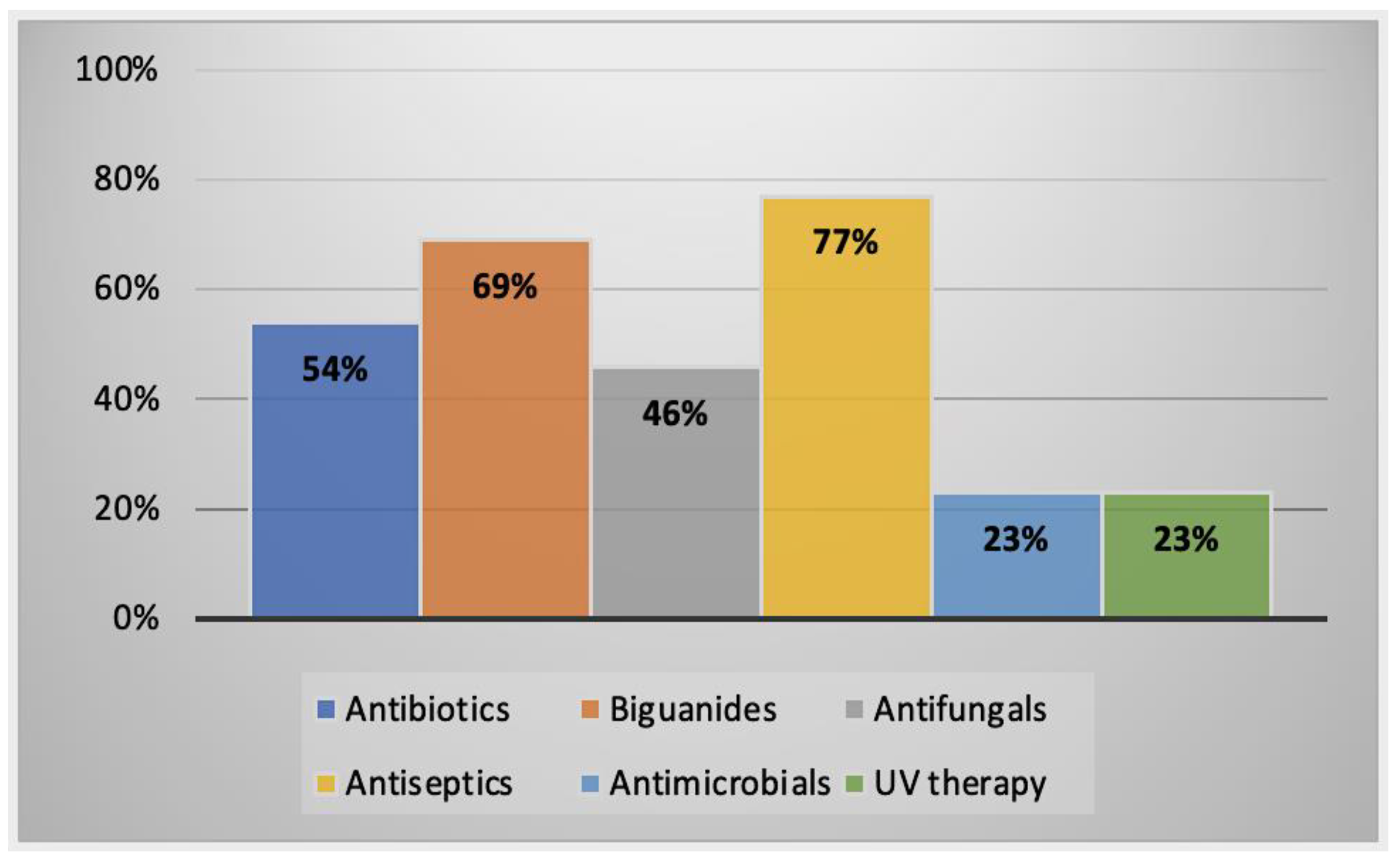

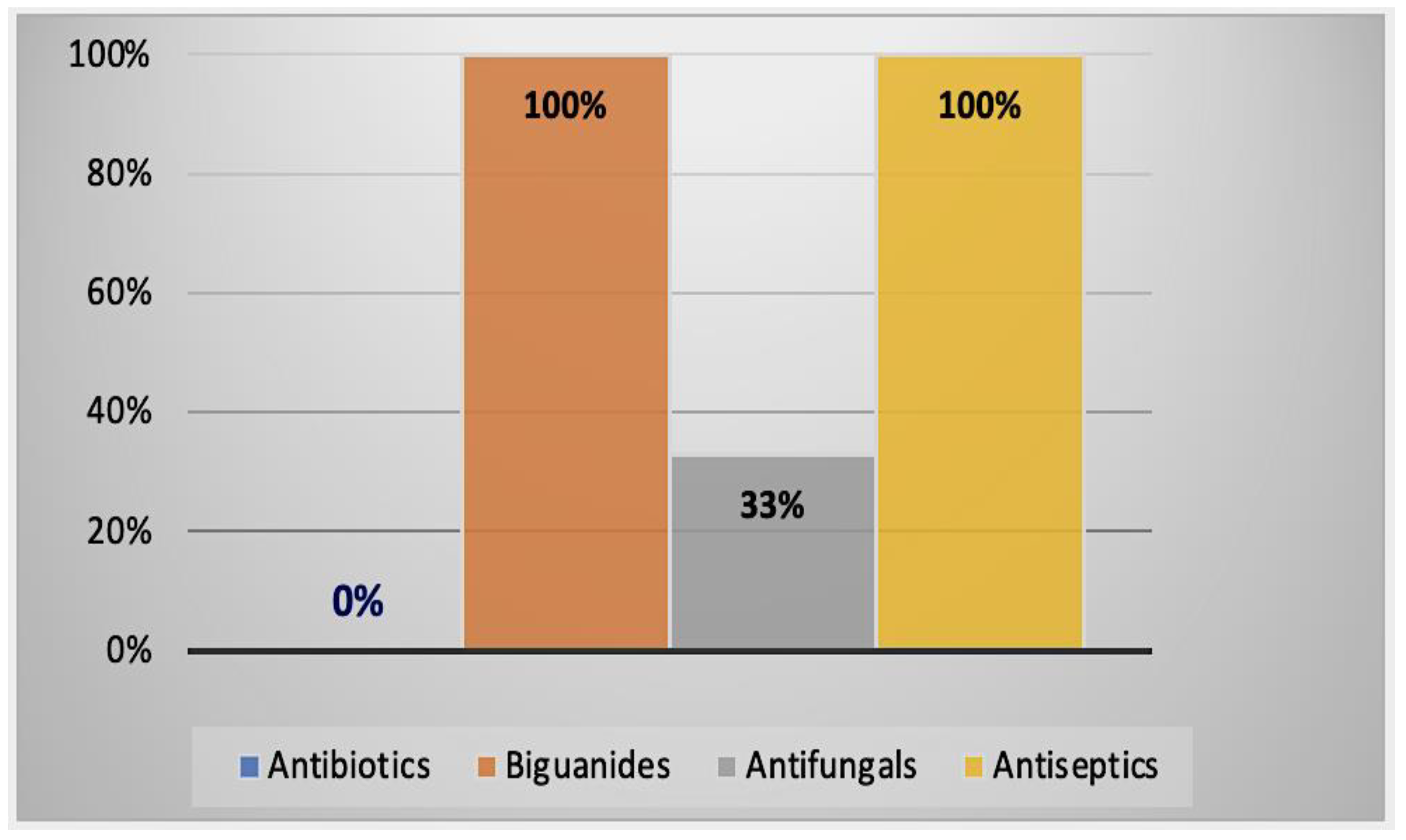

2.2.3. Alternative Treatment Methods

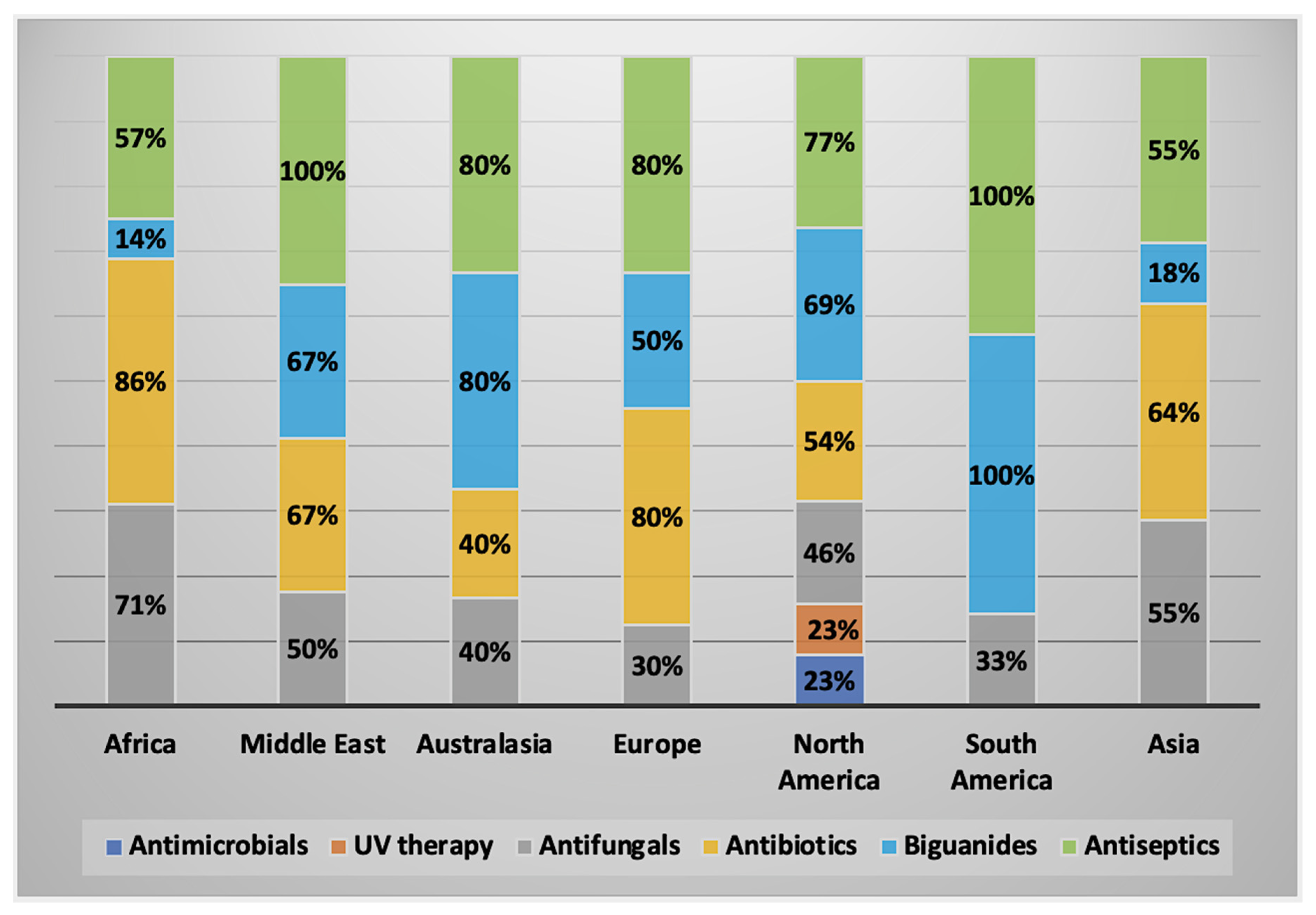

2.3. Characteristics of AK Cases by Geographical Regions

2.3.1. AK Cases in Africa

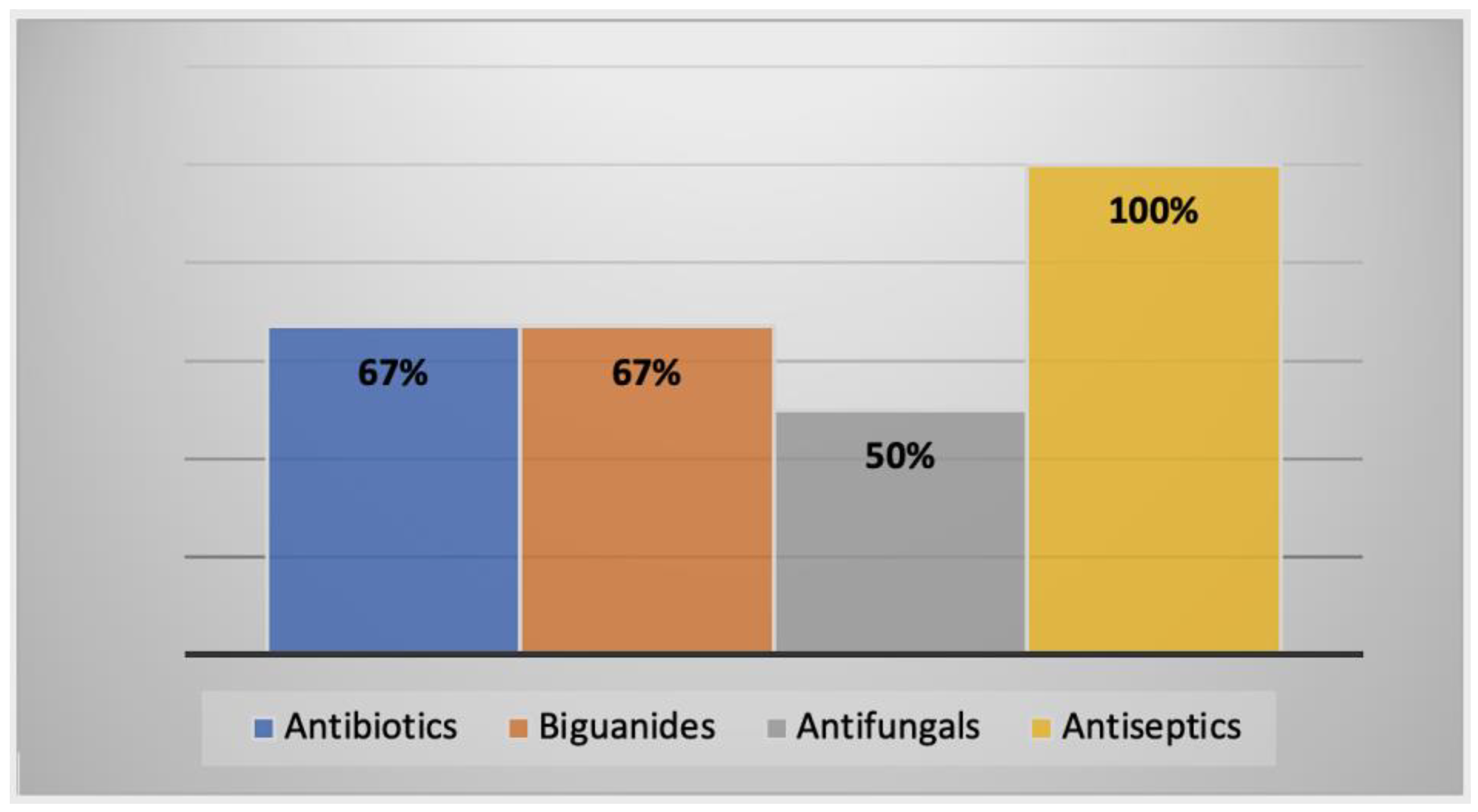

2.3.2. AK Cases in the Middle East

2.3.3. AK Cases in Australasia

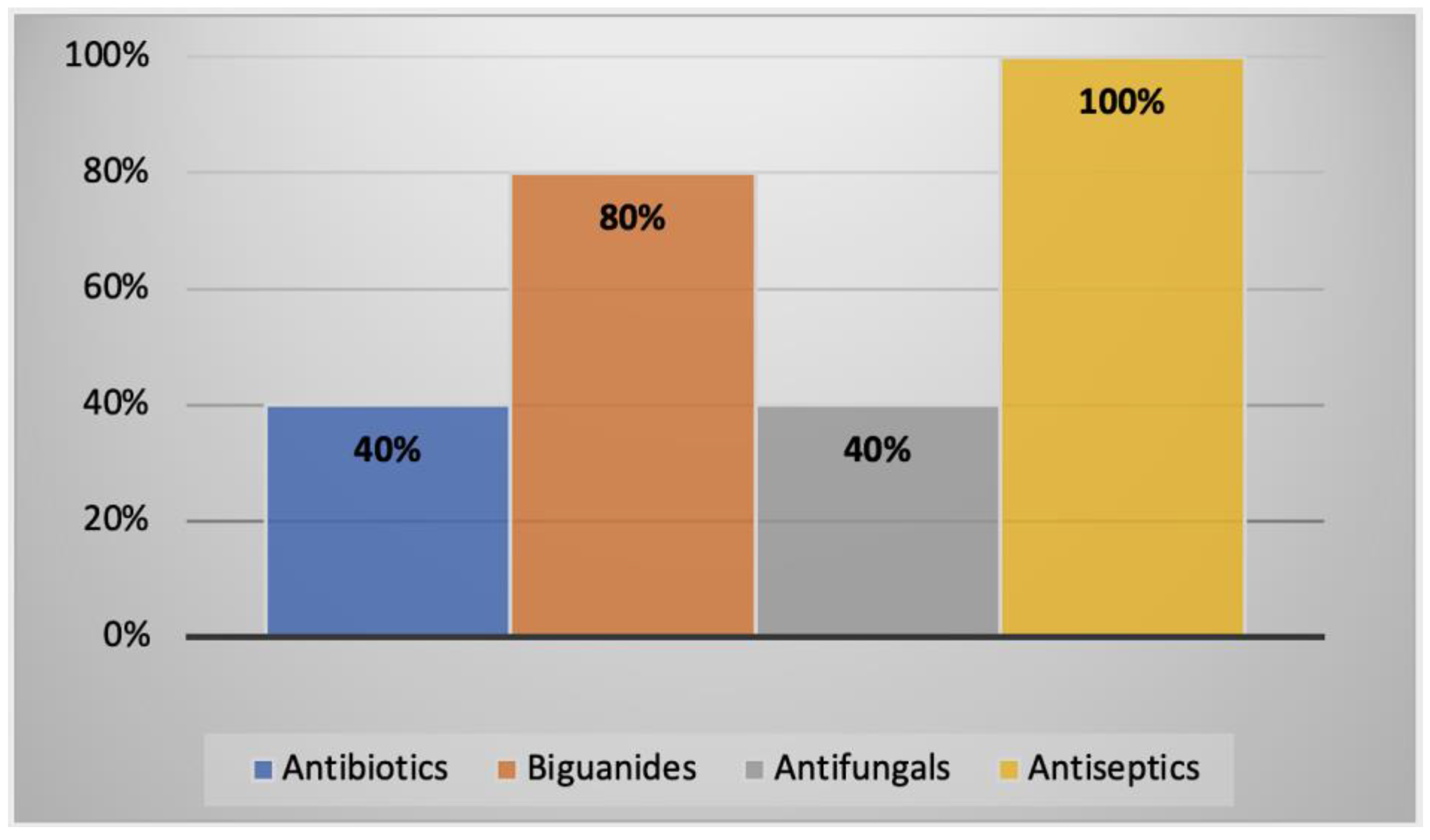

2.3.4. AK Cases in Europe

2.3.5. AK Cases in North America

2.3.6. AK Cases in South America

2.3.7. AK Cases in Asia

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification and Selection of Studies

4.2. Eligibility Criteria

4.3. Information Sources

4.4. Data Charting Process

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Case No. | Country | Age | Sex | Eye Involved | Contact Lens Wearer | Diagnostic Method(s) | Therapeutic Regimen | Outcome of Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | South Africa | 31 | F | Right | Yes | Culture and direct examination | Topical neomycin and 0.02% PHMB drops q1h continued for 12 months. | Improvement of symptoms following treatment, but best visual acuity was limited to counting fingers. No noted recurrence. | [45] |

| 2 | Ghana | 25 | M | Unknown | No | Direct examination | Chloramphenicol, gentamicin, and Econazole; no dose specified. | Improvement of symptoms with scar formation after 21 days; visual acuity was hand movements only. Patient lost before final visit. | [46] |

| 3 | Tunisia | 27 | F | Left | Yes | Culture and direct examination | Nizoral® 1 tab BID. Fungizone® ED 6× per day. Sophtal® 6× per day. Vancomycin-Fortum® and Desomedine® ED q1h for 2 days, then spaced out for 3 weeks. Desomedine® continued for 4 months. | Improvement of symptoms with good visual acuity. No noted recurrence. | [47] |

| 4 | Sudan | 55 | F | Left | Unknown | Culture | Oral ketoconazole 200 mg BID for 2 months. Topical saline 0.9%. | Symptoms improved; cornea scarred with remaining vision loss. No noted recurrence. | [48] |

| 5 | Tunisia | 29 | F | Right | Yes | Culture | Hexamidine 1 drop q1h for 30 days, then 8 drops per day for 3 months. Neomycin 1 drop 6× per day for 30 days. IV fluconazole 200 mg per day for 15 days. | Improvement of symptoms with corneal scarring with intent of undergoing penetrating keratoplasty. No noted recurrence. | [49] |

| 6 | Tunisia | 20 | F | Both | Yes | Direct examination | Hexamidine 1 drop q1h for 1 month; after 1 month, 8× per day for 3 months. Neomycin 1 drop q1h for 1 month; dropped after 1 month. | Improvement of symptoms with only small superficial opacities affecting vision. No noted recurrence. | [49] |

| 7 | Tunisia | 17 | F | Left | Yes | Culture and direct examination | Hexamidine 1 drop q1h for 1 month, then 8 drops per day for 3 months. Neomycin 1 drop q1h for 1 month. Gentamicin and vancomycin 1× q1h for 1 month IV Cefotaxime-Fosfomycin for 15 days. | Improvement of symptoms with visual opacities affecting visual acuity. No noted recurrence. | [49] |

| Case No. | Country | Age | Sex | Eye Involved | Contact Lens Wearer | Diagnostic Method(s) | Therapeutic Regimen | Outcome of Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Oman | 28 | F | Right | Yes | Confocal microscopy | 0.1% propamidine isethionate, 0.02% chlorhexidine, 0.02% polyhexamethylene biguanide. Medication not available and ordered from UK. Moxifloxacin 0.5% eye drops. Oral ketoconazole. | Moderate improvement of all clinical signs within 2 weeks. After 12 weeks, epithelial defect closed with no staining, leaving opacified cornea, which decreased visual acuity to hand motion. All medication continued. Follow-up 2 weeks later showed recurrence of symptoms. Advised to undergo therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty in India. Following graft cornea was clean with no pain and post-operatively treated with 0.1% propamidine isethionate, 0.5% moxifloxacin, and 0.1% dexamethasone eye drops. | [50] |

| 2 | Turkey | 41 | M | Right | Yes | Confocal microscopy | Propamidine isethionate 0.1% q1h. Moxifloxacin 2 drops 5× per day. Multi-purpose contact lens solution (PHMB and polyquaternium) q1h. Oral itraconazole 100 mg 2× BID. | After 6 months, visual acuity improved to 20/100 with improvement of most symptoms. | [51] |

| 3 | Iran | 28 | F | Left | Yes | Confocal microscopy and culture | Originally treated with Brolene® and Neosporin® for 2 months—no improvement. Treatment started using PHMB 0.02%, chlorhexidine gluconate 0.02% q2h. Oral fluconazole and cycloplegic ED. | No improvement for 1 week; symptoms subsequently worsened. Patient underwent debridement of necrotic tissue, penetrating keratoplasty, and amniotic membrane transplant. Prescribed chloramphenicol, Brolene®, and PHMB drops every 3 h. Oral fluconazole and acetazolamide every 6 h. Cleared 4 years post-operation. | [52] |

| 4 | Iran | 32 | M | Left | No | Confocal microscopy | Topical PHMB 0.02% and chlorhexidine 0.02% q1h during waking hours and q4h sleeping. Treatment altered to q4h for 1 week and tapered off to q6h for 1 month. | Gradual improvement over a 6-month period with no recurrence after treatment stopped. | [53] |

| 5 | Turkey | 5 | F | Right | No | Culture and direct examination | Topical 0.1% propamidine isethionate (Brolene®), topical neomycin sulfate, and polymyxin sulfate for 4 months | Complete symptom recovery with no visual loss or sequelae. | [54] |

| 6 | Turkey | 44 | F | Left | Yes | Culture and direct examination | 0.1% propamidine isethionate and chlorhexidine. Topical vancomycin (50 mg/mL) and ceftazidime (100 mg/mL) alternating. | No Acanthamoeba growth detected 2 months after treatment, but outcome not specified. | [54] |

| Case No. | Country | Age | Sex | Eye Involved | Contact lens Wearer | Diagnostic Method(s) | Therapeutic Regimen | Outcome of Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | New Zealand | 41 | M | Left | Yes | Culture | Initial treatment, Brolene® and Neosporin® drops started. One week later, oral itraconazole started. Symptoms worsened and readministered Neosporin®, Brolene®, 1% miconazole q1h, and prednisolone acetate 0.12% QID. Medication stopped after 3 weeks due to toxicity fears, started on 0.02% PHMB q2h to replace all but prednisolone acetate, now TID. | Symptoms improved after PHMB treatment, but cataract began swelling, which was treated using posterior chamber intraocular lens insertion and phacoemulsification. Treatment tapered off after 2 months with no recurrence. Visual acuity showed no improvement. | [55] |

| 2 | New Zealand | 27 | F | Left | Yes | Culture | 200 mg oral itraconazole, topical miconazole 1% q1h. No improvement, and patient underwent penetrating keratoplasty. | All therapy stopped after penetrating keratoplasty with clear graft after 1 year with improvement of symptoms. | [56] |

| 3 | New Zealand | 29 | F | Left | Yes | Culture and direct examination | 0.1% propamidine q1h, Neosporin® q1h, oral 200 mg itraconazole QD. Topical 1% miconazole q2h. After graft given 0.12% prednisolone drops QD. | Treatment had little effect, late diagnosis, and required penetrating keratoplasty. Patient required trabeculectomy for persistent glaucoma. Acuity was 6/6 after graft. | [56] |

| 4 | New Zealand | 41 | M | Unknown | Yes | Culture | 0.1% propamidine q1h, Neosporin® q1h, 0.1% miconazole q1h, oral itraconazole 200 mg QD and prednisolone 0.1%. This treatment did not cure AK. Patient given PHMB 0.02% q1h and prednisolone 0.12% TID. | Keratitis cured within 3 months of treatment, but patient developed cataract, which required surgery. Optic atrophy noted, which was possibly due to neurotoxicity from Neosporin® use. | [56] |

| 5 | New Zealand | 30 | M | Unknown | Yes | Culture | 0.02% PHMB q1h, 0.1% propamidine q1h. Propamidine stopped after 1 month, and PHMB reduced to q2h for 4 months. | Keratitis completely resolved after 4 months of treatment, with corrected vision being 6/6. | [56] |

| 6 | New Zealand | 35 | F | Unknown | Yes | Culture | PHMB 0.02% and 0.1% propamidine 6× per day 1% prednisolone TID. After 4 months, acuity dropped because of propamidine toxicity and was stopped thereafter. After 5 months, 0.1% chlorhexidine added to PHMB, both used QID. After 7 months, infection still present, and PHMB fortified to 0.1% 6× per day. Chlorhexidine stopped after 11 months of initial treatment. | After 11 months, patient needed total epithelial debridement with a stop on chlorhexidine. Twenty months later, cornea healed with ring of stromal scarring. Lens is clear and corrected, vision is 6/6. | [56] |

| 7 | New Zealand | 50 | M | Left | Yes | Direct examination | 0.02% PHMB 6× per day. | Cornea clear after 6 weeks of treatment and therefore stopped. | [56] |

| 8 | New Zealand | 26 | F | Unknown | Yes | Culture | 0.02% PHMB and propamidine q2h. Treatment showed no effect. Perforated cornea required penetrating keratoplasty after 11 months. | Graft remained clear with patient undergoing cataract extraction. Post-surgery given topical steroids, acetazolamide, and timolol. Best corrected vision is 6/18. | [56] |

| 9 | Australia | 17 | M | Both eyes | Yes | Culture | Initial treatment PHMB 0.02% q1h, Prednisolone phosphate 0.5% QID, Acyclovir ointment QID, and cyclopentolate 1% TID. Analgesia included naproxen 250 mg TID with codeine phosphate/paracetamol 30/500 mg 2 tables QID. Debridement completed daily for 3 days to remove tissue. Acyclovir stopped after herpes simplex negative diagnosis. After 7 days, reduced PHMB to qih during daytime and 0.1% propamidine isethionate q2h added. PHMB reduced over 4 weeks. Topical therapies reduced to BID 1 month later, then stopped after another 2 months. | Symptoms improved without recurrence after 2 months. Visual acuity for the left eye was 6/5. | [57] |

| 10 | Australia | 47 | F | Left | Yes | Culture and confocal microscopy | Initial treatment included 0.02% PHMB q2h and chlorhexidine 0.006% and propamidine isethionate 0.1% q2h. Atropine 1% QD, oral sodium diclofenac 50 mg BID. Fortified gentamicin 1.2% q2h was used with cephalothin q2h in alternation. Antimicrobial drops were administered round the clock for 24 h, then hourly during waking hours until day 3. At day 3, antimicrobial drops were reduced to q4h with 0.1% fluorometholone q4h. At day 6, gentamicin replaced with 0.3% gentamicin. | All antibacterial therapy stopped after day 10; after day 21, amoebic treatment reduced to 5× per day with slight visual improvement. Pain medication stopped after 3 months. Gradual improvement over 12 months with no cysts present at 18 months. Central subepithelial scar present with best corrected visual acuity 6/6 + 1. | [58] |

| Case no. | Country | Age | Sex | Eye Involved | Contact lens Wearer | Diagnostic Method(s) | Therapeutic Regimen | Outcome of Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Slovakia | 53 | M | Right | Unknown | Culture | Initial treatment involved misdiagnosis, and antibiotics used were ineffective. Itraconazole 200 mg split into 2 doses per day for 5 weeks. Loratadinum tablets. Analgesics included 400 mg Ibuprofenum. Neomycin, Polymixin B, and phenylephrine; no dose specified. 5× per day hypromellosum ED. | Between December and January 1999–2000, partial improvement seen, and therapy continued. Keratoplasty performed with no improvement resulting in enucleation of globe. | [59] |

| 2 | Slovakia | 39 | M | Left | Yes | Culture | Only drug available at time of diagnosis was Itraconazole; no dose specified. Once 0.1% Brolene® obtained, used every 30 min. Combined with oflaxicine and cephazoline ED; no dose specified. White deposits identified, and subsequently, itraconazole stopped. | Improvement of symptoms after 3 weeks. Treatment continued until satellite infiltrations appeared when attempts to stop therapy occurred. Cornea cleared and vision improved with corneal defect correcting patient myopia. | [59] |

| 3 | Slovakia | 16 | F | Both eyes | Yes | Culture and direct examination | Brolene® 5× per day, Acyclovir and Neomycin; no dose specified. | After 2 months, symptoms improved with improved visual acuity 5/7.5 to 5/5 for the right and 5/15 to 5/10. | [59] |

| 4 | Germany | 55 | F | Left | Yes | Culture | Brolene®, Lavasept®, and Polyspectran® used in rotation every 15 min for 3 days, including during sleep. Atropine ED TID. Therapy then reduced to every half hour with breaks at night. Patient discharged, and Brolene® continued, biguanide ED and 2.5% prednisolone ED TID. Corneregel® Fluid every 30 min and Acyclovir 800 mg 5× per day. | After 17 days, symptoms worsened with patient returning. After 6 weeks, symptoms improved, leaving corneal scar and a vision of 0.6. | [60] |

| 5 | Malta | 17 | F | Both eyes | Yes | Culture | Atropine 1% BID per day and 0.15% dibromopropamidine BID. Propamidine isethionate 0.02% chlorhexidine, 0.02% PHMB ordered from abroad. Once arrived, PHMB and chlorhexidine q2h, Propamidine isethionate q1h. | Treatment improved symptoms 4 days after medication arrived. Dibromopropamidine and atropine stopped. 750 mg ciprofloxacin prescribed BID. After 21 days patient discharged, but follow-ups done abroad. | [61] |

| 6 | Germany | 22 | F | Left | Yes | Culture | Brolene® ED, Polyspectran®, and Lavasept® half-hourly. Treatment altered to only Polyspectran® after 4 weeks. | Symptoms improved to levels similar to before infection. | [62] |

| 7 | Romania-Belgium | 9 | F | Left | No | Confocal microscopy | Received treatment with different antimicrobials when misdiagnosed. After no improvement, patient sent to Belgium as treatment not available in Romania. | Outcome unknown since traveled for treatment but received “appropriate care”. | [63] |

| 8 | Spain | 29 | F | Right | Yes | Culture, direct examination, and confocal microscopy | Chlorhexidine 0.02% ED q2h, 0.1% propamidine isethionate q1h. Single-dose of azithromycin dihydrate q4h. | Patient pregnant during infection—lack of literature in terms of pregnancy and amoebicidal drugs—lacrimal punctal plugs given. Melting ulcer appeared with seemingly no Acanthamoeba present—stopped amoebicidal drugs and converted to dexamethasone phosphate ED, Azydrop, and artificial tears. Patient gave birth at 35 weeks with no complications. | [64] |

| 9 | Scotland | 73 | F | Left | Yes | Direct examination (slit-lamp) and PCR. | Biguanide and diamidine; no dose specified. | After 4 weeks, still positive for Acanthamoeba. Patient underwent 1 failed and 1 successful corneal transplant. Second was clear and no recurrence. | [65] |

| 10 | Poland | 48 | F | Left | Yes | Culture, PCR, and confocal microscopy | 0.2% PHMB, 0.1% propamidine isethionate, neomycin with ketoconazole. Three months after treatment, symptoms did not improve, and patient underwent penetrating keratoplasty. | After transplant, cataract developed which required another, which patient is awaiting. Visual acuity limited to hand movements. | [66] |

| Case no. | Country | Age | Sex | Eye Involved | Contact Lens Wearer | Diagnostic Method(s) | Therapeutic Regimen | Outcome of Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | 61 | M | Right | Yes | Confocal microscopy | Treated for presumed bacterial infection with no improvement. 0.02% PHMB, 0.1% propamidine isethionate, and 0.02% chlorhexidine ED q1h. Little improvement after 1 month treated with UVA and B2 with continuation of medication. | After treatment, ulcers began closing and closed completely after 6 weeks Patient had central corneal scars which affected visual field and underwent penetrating keratoplasty. No recurrence after 12 months. | [41] |

| 2 | USA | 35 | M | Right | Yes | Culture and direct examination | 0.02% chlorhexidine gluconate, 0.02% PHMB, and 0.1% propamidine isethionate started q1h for 14 days. No improvement after 45 days. Started UVA and B2 treatment with continuation of medication. | After treatment, ulcers began closing and closed completely after 3 weeks Patient had central corneal scars which affected visual field and underwent penetrating keratoplasty. No recurrence after 8 months. | [41] |

| 3 | Costa Rica | 30 | M | Left | Yes | Culture and confocal microscopy | 0.02% chlorhexidine gluconate q1h, 0.02% PHMB q30 min. After 30 days, no improvement, and patient underwent UVA and B2 treatment. | After treatment, ulcers began closing and closed completely after 7 weeks Patient left with semi-transparent scar not in visual axis with no cysts present under confocal microscopy. No indication of recurrence after 4 months. | [41] |

| 4 | USA | 53 | F | Left | Yes | Culture and confocal microscopy | Treated with anti-herpetic drugs with no effect with continuation of anti-viral drugs. Diagnosis of AK meant PHMB, no dose specified, started with removal of anti-virals. Desomedine™ added; no dose specified. Patient developed concurrent fungal infection, which was treated with oral fluconazole and amphotericin B; no dose specified. Underwent penetrating keratoplasty. | Two months post-operation, corrected visual acuity limited to 20/100 with a clear graft. Anti-amoebic treatment stopped. | [67] |

| 5 | Mexico | 38 | F | Left | Yes | Culture | 0.3% netilmicin, 100 mg/12 h oral itraconazole, and phenylephrine/tropicamide. | Symptoms improved, and after 8 months of treatment, infection ceased leaving small puncture not affecting visual acuity. | [68] |

| 6 | USA | 54 | M | Left | Yes | Culture | Initial treatment involved steroids, antibiotics for suspected herpetic endotheliitis. Symptoms did not improve and started on voriconazole, polymyxin B, and PHMB; no dose specified. Patient received corneal bandage and amniotic extracellular matrix placement. | Further biopsies showed persistent infection with corneal cross-linking performed. After 1 year, visual acuity was limited to hand motion with neovascularisation and conjunctivalisation of the cornea. | [16] |

| 7 | USA | 18 | M | Left | Yes | Culture | Treatment for misdiagnosed herpetic keratitis with no improvement. Patient given PHMB and chlorhexidine; no dose specified. | After 4 months, patient-reported symptoms returned to baseline. Tapered off corticosteroid and discontinued PHMB, chlorhexidine after 1 month. | [16] |

| 8 | USA | 28 | M | Left | Yes | Culture | Patient underwent total corneal epithelial debridement. 0.02% chlorhexidine q1h started and stopped after day 5. PHMB 12.5 mg/0.1 mL q1h started and, over the course of a few weeks, was tapered down. | Symptoms healed after 5 days treatment. After 3 months, corrected vision was 20/20 with no recurrence. | [69] |

| 9 | USA | 43 | M | Both eyes | Yes | Culture | Initial treatment for misdiagnosed HK. Underwent epithelial debridement. 0.02% chlorhexidine q1h. Besifloxacin 0.1% q1h. After 12 weeks, chlorhexidine stopped. | Symptoms healed fully, and at 7-month check, acuity had improved from 20/100 to 20/30 for right eye and 20/150 to 20/70 for left, respectively. | [69] |

| 10 | USA | 38 | F | Left | Yes | Confocal microscopy and PCR | Treated with voriconazole, moxifloxacin, chlorhexidine, oral fluconazole, and valacyclovir; no dose specified. Treatment had no effect, and symptoms worsened. Treated with IV pentamidine for 2 weeks. Underwent penetrating keratoplasty. After operation, treated with oral miltefosine, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and voriconazole for 6 months. | Improved after penetrating keratoplasty, with no recurrence after 3 years. Patient underwent cataract surgery to improve vision. | [70] |

| 11 | USA | 59 | F | Left | Yes | Confocal microscopy and culture | Treated for initial fungal keratitis until Acanthamoeba diagnosis with voriconazole, moxifloxacin, acyclovir; no dose specified. After diagnosis chlorhexidine, no dose specified, added. Miltefosine added, and 1 month later, patient underwent deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty. After 2 weeks, voriconazole and miltefosine stopped. | Patient symptoms improved over 3 years with cataract surgery used to restore acuity. | [70] |

| 12 | USA | 71 | F | Left | Yes | PCR and confocal microscopy | Initial treatment with ofloxacin and propamidine isethionate; no dose specified. Recurrence of infection led to adding moxifloxacin and chlorhexidine. Signs continued to deteriorate and underwent deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty. Treated with chlorhexidine, voriconazole, and acyclovir. Miltefosine was also given. | Two months after deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty, recurrence of infection occurred. Continued with chlorhexidine but PHMB added, no dose specified. Patient underwent penetrating keratoplasty. Miltefosine discontinued due to patient issues. Cataract surgery was performed to improve vision which required another penetrating keratoplasty for allograft failure. PHMB stopped, and patient given guarded prognosis. | [70] |

| 13 | USA | 46 | F | Right | Yes | Confocal microscopy | PHMB, tobramycin, voriconazole, vancomycin, valacyclovir; no dose specified. Added miltefosine and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Patient underwent penetrating keratoplasty. | Outcome affected by worsening symptoms with the need for corneal transplant. Inflammation affected graft, and third penetrating keratoplasty required, as well as cataract surgery. Healing not aided by neurotrophic keratopathy. | [70] |

| Case no. | Country | Age | Sex | Eye Involved | Contact Lens Wearer | Diagnostic Method(s) | Therapeutic Regimen | Outcome of Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brazil | 19 | F | Both eyes | Yes | Unspecified lab tests | 0.02% PHMB, 0.1% propamidine isethionate ED q1h. 200 mg ketoconazole BID over the period of 4 months. Symptoms worsened, and patient underwent corneal transplantation for both eyes. Cancelled due to massive orbital hemorrhage. | Recovery was difficulty, patient suffered ocular perforation requiring a penetrating corneal transplant. Given 0.5% timolol maleate and 0.2% brimonidine tartrate TID and 250 mg acetazolamide BID. Underwent phacoemulsification with trabeculectomy and lens implantation. Patients’ corneal grafts were clear with no signs or symptoms of infection, but visual acuity was 0.2. Patient lost to follow-up. | [71] |

| 2 | Brazil | 27 | F | Left | Yes | Culture and PCR | Treatment with Chlorhexidine, Biguanide, and Brolene® for 6 months. Underwent corneal transplant. | After transplant, acuity improved with no recurrence. | [72] |

| 3 | Brazil | 28 | F | Unknown | Yes | Culture and PCR | Biguanide and Brolene® ED. Patient underwent emergency penetrating keratoplasty after 3 months due to corneal opacification. | After surgery, vision returned to 20/20. No noted recurrence. | [73] |

| Case no. | Country | Age | Sex | Eye Involved | Contact Lens Wearer | Diagnostic Method(s) | Therapeutic Regimen | Outcome of Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | India | 26 | F | Left | Unknown | Culture and direct examination | 10 mg/mL topical miconazole, Neosporin® q6h. After 13 days miconazole replaced with 5 mg/mL metronidazole for 9 days. | Symptoms improved with minimal scar present after 4.5 months. Slight improvement in visual acuity. | [74] |

| 2 | India | 40 | M | Left | Unknown | Culture and direct examination | Metronidazole q6h, Neosporin® q6h, and atropine TID. After second culture, miconazole replaced metronidazole. After day 23, metronidazole added once again to therapy. | After day 40, symptoms improved, and patient was advised keratoplasty but refused. Returned later with worsened symptoms with no more specified outcome. | [74] |

| 3 | India | 47 | M | Right | Unknown | Culture and direct examination | Treatment with Miconazole q1h, Neosporin® q6h. | Patient discharged from hospital on request with advice to continue treatment. Symptoms did not improve, and patient remained positive for Acanthamoeba after follow-ups. Patient lost and outcome unknown. | [74] |

| 4 | India | 30 | M | Left | Unknown | Culture and direct examination | Metronidazole ED q7h. After 7 days, symptoms worsened. Metronidazole replaced with 1% ketoconazole q1h and Neosporin® q6h and BID 1% atropine. Analgesics were also given. | After 7 days, symptoms improved; after 18 days, patient discharged and instructed to continue Ketoconazole q4h, Neosporin®, and 1% atropine BID. No follow-up. | [74] |

| 5 | India | 40 | F | Left | Yes | Culture | Neosporin® ED, 2% ketoconazole q1h for 2 days then q2h from the third day. 1% cyclopentolate BID and other analgesics added. | After 6 weeks, symptoms improved with scarring present. Last seen still using Neosporin® TID with discontinuation of ketoconazole. | [75] |

| 6 | Malaysia | 40 | F | Right | Yes | Direct examination | After initial culture tested positive for bacteria, patient given gentamicin then Neosporin, ketoconazole, and miconazole. Symptoms worsened, and Brolene® ED ordered as not available in Malaysia. | Patient discharged with instructions to seek treatment abroad, outcome not known. | [76] |

| 7 | China | 9 | M | Right | Yes | Culture | 0.02% PHMB, 0.1% propamidine isethionate ED q1h. | After 3 days, considerable improvement seen, with treatment ending after 4 months. Faint scarring observed at the last check-up. | [77] |

| 8 | Indonesia | 32 | F | Left | Yes | Culture | Initial treatment showed little improvement, started on Brolene®, neomycin, polymyxin, gramicidin ED q1h. | Improvement of symptoms after 2 weeks, then no further improvement. Patient underwent amniotic membrane transplant after 6 weeks. Treatment continued for 2 months. Scarring meant corneal transplant scheduled for patient. | [78] |

| 9 | India | 9 | M | Right | No | Direct examination, culture and PCR | 0.02% PHMB q1h. 1% atropine ED TID and tear supplements TID. After 1 week, no improvement, and 0.02% chlorhexidine added q1h. | After 3 weeks, improvement noted, and frequency of drugs decreased. PHMB 8× per day, Chlorhexidine QID. After 8 weeks, complete healing of lesion observed. Scarring affected visual acuity. | [79] |

| 10 | China | 21 | F | Left | Yes | Confocal microscopy | Chlorhexidine 0.02% q1h. After 4 days, cysts still present, and chlorhexidine changed to q2h for 4 weeks. After 1 month, patient given 0.02% chlorhexidine QID and sodium hyaluronate 0.3% ED. | Symptoms improved; after 70 days, corrected vision returned to 20/20. Corneal opacity was noted but small and medication discontinued. No noted recurrence after 6 months. | [80] |

| 11 | China | 17 | F | Left | Yes | Confocal microscopy | 0.02% chlorhexidine ED q1h for 7 days. After 7 days, symptoms improved, and regime altered to q2h for 4 weeks, then q4h during the next 4. | After 2 months, symptoms improved, with corrected vision being 20/20. Slight corneal opacity noted, and medication discontinued with no recurrence after 7 months. | [80] |

References

- Khan, N.A. Acanthamoeba: Biology and increasing importance in human health. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 30, 564–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seal, D.; Stapleton, F.; Dart, J. Possible environmental sources of Acanthamoeba spp. in contact lens wearers. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1992, 76, 424–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Visvesvara, G.S.; Stehr-Green, J.K. Epidemiology of free-living ameba infections. J. Protozool. 1990, 37, 25S–33S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekkla, A.; Sutthikornchai, C.; Bovornkitti, S.; Sukthana, Y. Free-living ameba contamination in natural hot springs in Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2005, 36 (Suppl. 4), 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, E.; Cowmeadow, W.; Elsheikha, H.M. Should veterinary practitioners be concerned about Acanthamoeba keratitis? Parasitologia 2021, 1, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano-Cabral, F.; Puffenbarger, R.; Cabral, G.A. The increasing importance of Acanthamoeba infections. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2000, 47, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewitt, H. Contact lenses. Infections and hygiene. Ophthalmologe 1997, 94, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N.; Nagra, P.; Hammersmith, K. Emerging trends in contact lens-related infections. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 27, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMonnies, C.W. Hand hygiene prior to contact lens handling is problematical. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2012, 35, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbleton, K.A.; Woods, C.A.; Jones, L.W.; Fonn, D. The relationship between compliance with lens replacement and contact lens-related problems in silicone hydrogel wearers. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2011, 34, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnt, N.; Hoffman, J.M.; Verma, S.; Hau, S.; Radford, C.F.; Minassian, D.C.; Dart, J.K.G. Acanthamoeba keratitis: Confirmation of the UK outbreak and a prospective case-control study identifying contributing risk factors. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilvington, S.; Gray, T.; Dart, J.; Morlet, N.; Beeching, J.R.; Frazer, D.G.; Matheson, M. Acanthamoeba keratitis: The role of domestic tap water contamination in the United Kingdom. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salameh, A.; Bello, N.; Becker, J.; Zangeneh, T. Fatal Granulomatous Amoebic Encephalitis caused by Acanthamoeba in a patient with kidney transplant: A case report. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2015, 2, ofv104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpek, G.; Uslu, A.; Huebner, T.; Taner, A.; Rapoport, A.P.; Gojo, I.; Akpolat, Y.T.; Ioffe, O.; Kleinberg, M.; Baer, M.R. Granulomatous amebic encephalitis: An under-recognized cause of infectious mortality after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2011, 13, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentmáryn, N.; Daas, L.; Shi, L.; Laurik, K.L.; Lepper, S.; Milioti, G.; Seitz, B. Acanthamoeba keratitis - Clinical signs, differential diagnosis and treatment. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2019, 31, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Srikumaran, D.; Zafar, S.; Salehi, M.; Liu, T.S.; Woreta, F.A. Case series: Delayed diagnoses of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2020, 19, 100778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claerhout, I.; Goegebuer, A.; Van Den Broecke, C.; Kestelyn, P. Delay in diagnosis and outcome of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2004, 242, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretz, A.; Geffen, Y.; Socea, S.D.; Pastukh, N.; Graffi, S. Comparison of fluorescence microscopy and different growth media culture methods for Acanthamoeba Keratitis diagnosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 93, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maycock, N.J.; Jayaswal, R. Update on Acanthamoeba Keratitis: Diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Cornea 2016, 35, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, A.; Nair, A.V.; Kavitha, N.; Venkatapathy, N.; Rammohan, R. Voriconazole in the successful management of a case of Acanthamoeba-Cladosporium keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2021, 22, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borin, S.; Feldman, I.; Ken-Dror, S.; Briscoe, D. Rapid diagnosis of acanthamoeba keratitis using non-nutrient agar with a lawn of E. coli. J. Ophthalmic. Inflamm. Infect. 2013, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yera, H.; Ok, V.; Lee Koy Kuet, F.; Dahane, N.; Ariey, F.; Hasseine, L.; Delaunay, P.; Martiano, D.; Marty, P.; Bourges, J.L. PCR and culture for diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 105, 1302–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheikha, H.M.; Siddiqui, R.; Khan, N.A. Drug discovery against Acanthamoeba infections: Present knowledge and unmet needs. Pathogens 2020, 9, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, G.; Matuska, S.; Rama, P. Double-biguanide therapy for resistant acanthamoeba keratitis. Case. Rep. Ophthalmol. 2011, 2, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.H.; Gabison, E.E.; Kato, T.; Azar, D.T. Corneal neovascularization. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2001, 12, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Day, D.M.; Head, W.S. Advances in the management of keratomycosis and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea 2000, 19, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scruggs, B.A.; Quist, T.S.; Zimmerman, M.B.; Salinas, J.L.; Greiner, M.A. Risk factors, management, and outcomes of Acanthamoeba keratitis: A retrospective analysis of 110 cases. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2022, 25, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataillie, S.; Van Ginderdeuren, R.; Van Calster, J.; Foets, B.; Delbeke, H. How a devastating case of Acanthamoeba sclerokeratitis ended up with serious systemic sequelae. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2020, 11, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Y.W.; Boase, D.L.; Cree, I.A. How could contact lens wearers be at risk of Acanthamoeba infection? A Review. J. Optom. 2009, 2, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y.T.; Zhu, H.; Harmis, N.Y.; Iskandar, S.Y.; Willcox, M.; Stapleton, F. Profile and frequency of microbial contamination of contact lens cases. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2010, 87, E152–E158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnt, N.; Stapleton, F. Strategies for the prevention of contact lens-related Acanthamoeba keratitis: A review. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2016, 36, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rayamajhee, B.; Willcox, M.D.; Henriquez, F.L.; Petsoglou, C.; Carnt, N. Acanthamoeba keratitis: An increasingly common infectious disease of the cornea. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e345–e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Garg, P.; Rao, G.N. Patient characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment of non-contact lens related Acanthamoeba keratitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 84, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, C.; Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Acanthamoeba keratitis: Clinical characteristics and management. Ocul. Surf. 2015, 13, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, L.A.; Gotuzzo, E. Intestinal protozoan infections in the immunocompromised host. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 26, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evering, T.; Weiss, L.M. The immunology of parasite infections in immunocompromised hosts. Parasite Immunol. 2006, 28, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarova, A.; Tussupova, K.; Berndtsson, R.; Kalishev, M.; Sharapatova, K. Protozoan parasites in drinking water: A system approach for improved water, sanitation and hygiene in developing countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosado-García, F.M.; Guerrero-Flórez, M.; Karanis, G.; Hinojosa, M.D.C.; Karanis, P. Water-borne protozoa parasites: The Latin American perspective. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 783–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, C.F.; Minassian, D.C.; Dart, J.K.G. Acanthamoeba keratitis in England and Wales: Incidence, outcome, and risk factors. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nadia, B.A.; Anis, M.; Ali, S.M.; Ahmed, M.; Sana, R.; Mohamed, G.; Hechemi, M.; Leila, K.; Fethi, K. Acanthamoeba keratitis in contact lens wearers in a tertiary center of Tunisia, North Africa. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 70, 102834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.A.; Kashiwabuchi, R.T.; Martins, S.A.; Castro-Combs, J.M.; Kalyani, S.; Stanley, P.; Flikier, D.; Behrens, A. Riboflavin and ultraviolet light a therapy as an adjuvant treatment for medically refractive Acanthamoeba keratitis: Report of 3 cases. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, K.J.; O’Day, D.M.; Head, W.S.; Neff, R.J.; Elliott, J.H. Herpes simplex masquerade syndrome: Acanthamoeba keratitis. Curr. Eye Res. 1987, 6, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, W.D.; Goldberg, M.A.; Sutphin, J.E.; Ditkoff, J.W.; Folberg, R. Coexistent Acanthamoeba keratitis and herpetic keratitis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1997, 115, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo-Morales, J.; Khan, N.A.; Walochnik, J. An update on Acanthamoeba keratitis: Diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. Parasite 2015, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dini, L.A.; Cockinos, C.; Frean, J.A.; Niszl, I.A.; Markus, M.B. Unusual case of Acanthamoeba polyphaga and Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis in a contact lens wearer from Gauteng, South Africa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leck, A.K.; Matheson, M.M.; Hagan, M.; Ackuaku, E. Acanthamoeba keratitis in Ghana. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonia, A.; Narjess Ben, A.; Ines, M.; Leila, N.; Emira, K.; Slah, B.; Saida, A.; Kalthoum, K.; Emna, C. Acanthamoeba keratitis: Diagnosis to consider. Sante 2008, 18, 209–213. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, A.M.; Mahgoub, E.S. Blindness due to Acanthamoeba: First case report from Sudan. Int. J. Health Sci. 2008, 2, 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fathallah, A.; Ben Rayana, N.; Knani, L.; Meksi, S.G.; Saghrouni, F.; Ghorbel, M.; Hamida, F.B.; Ben Said, M. Acanthamoeba keratitis. Report of 3 cases diagnosed in central Tunisia. Tunis Med. 2010, 88, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Al Kharousi, N.S.; Wali, U.K. Culture negative confoscan positive Acanthamoeba Keratitis: A relentless course. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2009, 9, 338–340. [Google Scholar]

- Sengor, T.; Yuzbasioglu, E.; Aydın Kurna, S.; Irkec, M.; Altun, A.; Kökcen, K.; Yalcin, N.G. Dacryoadenitis and extraocular muscle inflammation associated with contact lens-related Acanthamoeba keratitis: A case report and review of the literature. Orbit 2017, 36, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadpour, M.; Rahimi, F.; Khorrami-Nejad, M. Total necrosis of cornea, iris and crystalline lens with exposure of vitreous hyaloid face in the context of recalcitrant acanthamoeba keratitis. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2018, 30, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyman, A.; Pourazizi, M.; Peyman, M.; Kianersi, F. Natural honey-induced Acanthamoeba keratitis. Middle East. Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 26, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alver, O.; Baykara, M.; YÜrÜk, M.; TÜzemen, N.Ü. Acanthamoeba keratitis and Acanthamoeba conjunctivitis: A case report. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2020, 15, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, T.B.; Gross, K.A.; Cursons, R.T.M.; Shewan, J.F. Acanthamoeba keratitis: A sobering case and a promising new treatment. Aust. N. Z. J. Ophthalmol. 1994, 22, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdoch, D.; Gray, T.B.; Cursons, R.; Parr, D. Acanthamoeba keratitis in New Zealand, including two cases with in vivo resistance to polyhexamethylene biguanide. Aust. N. Z. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 26, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajdatsy, A.D.; Kosmin, A.; Barrett, G.D. Coexistent adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2000, 28, 434–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, F.; Ozkan, J.; Jalbert, I.; Holden, B.A.; Petsoglou, C.; McClellan, K. Contact lens-related Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2009, 86, E1196–E1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondriska, F.; Mrva, M.; Lichvár, M.; Ziak, P.; Murgasová, Z.; Nohýnková, E. First cases of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Slovakia. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2004, 11, 335–341. [Google Scholar]

- Scheid, P.; Zöller, L.; Pressmar, S.; Richard, G.; Michel, R. An extraordinary endocytobiont in Acanthamoeba sp. isolated from a patient with keratitis. Parasitol. Res. 2008, 102, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachia Markham, M.; Mercieca, F. Bilateral Acanthamoeba keratitis. The Synapse 2012, 1, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Grün, A.-L.; Stemplewitz, B.; Scheid, P. First report of an Acanthamoeba genotype T13 isolate as etiological agent of a keratitis in humans. Parasitol. Res. 2014, 113, 2395–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristina, S.; Cristina, V.; Mihaela, P. Acanthamoeba keratitis challenges a case report. Rom. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 60, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Borja Domínguez-Serrano, F.; Caro-Magdaleno, M.; Perea-Pérez, R.; Rodríguez-de-la-Rúa, E.; Montero-Iruzubieta, J. Case report: Acanthamoeba Keratitis management in a first-trimester pregnant patient. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2018, 95, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, L.; Anijeet, D.; Alexander, C.L. A descriptive case of persistent Acanthamoeba keratitis: Raising awareness of this complex ocular disease. Access Microbiol. 2019, 2, acmi000084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel-Dudzińska, D. Atypical presentation of Acanthamoeba Keratitis-case report and review of the literature. Ann. Clin. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Knickelbein, J.E.; Kovarik, J.; Dhaliwal, D.K.; Chu, C.T. Acanthamoeba keratitis: A clinicopathologic case report and review of the literature. Hum. Pathol. 2013, 44, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omaña-Molina, M.; Vanzzini-Zago, V.; Hernández-Martínez, D.; Reyes-Batlle, M.; Castelan-Ramírez, I.; Hernández-Olmos, P.; Salazar-Villatoro, L.; González-Robles, A.; Ramírez-Flores, E.; Servín-Flores, C.; et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis in Mexico: Report of a clinical case and importance of sensitivity assays for a better outcome. Exp. Parasitol. 2019, 196, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shekhawat, N. Acanthamoeba epitheliopathy: Importance of early diagnosis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2022, 26, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Ashraf, N.; Haghnegahdar, M.; Goins, K.; Newman, J.R. Acanthamoeba Keratitis: A single-institution series of four cases with literature review. Cureus 2022, 14, e21112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, S.J.d.F.; Dias, V.G.; Marcomini, L.A.G. Bilateral Acanthamoeba ulcer in a user of disposable soft contact lenses: A tragic incident or a consequence of the aggressive policy of soft contact lens trading? Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2008, 71, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabres, L.F.; Maschio, V.J.; dos Santos, D.L.; Kwitko, S.; Marinho, D.R.; de Araújo, B.S.; Locatelli, C.I.; Rotta, M.B. Virulent T4 Acanthamoeba causing keratitis in a patient after swimming while wearing contact lenses in Southern Brazil. Acta Parasitol. 2018, 63, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, D.d.S.M.M.; Gonçalves, G.S.; Moraes, A.S.; Alves, L.M.; Carmo Neto, J.R.d.; Hecht, M.M.; Nitz, N.; Gurgel-Gonçalves, R.; Bernardes, G.; Castro, A.M.d. The first Acanthamoeba keratitis case in the Midwest region of Brazil: Diagnosis, genotyping of the parasite and disease outcome. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2018, 51, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Srinivasan, M.; George, C. Diagnosis of acanthamoeba keratitis-A report of four cases and review of literature. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 1990, 38, 50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, M.; Channa, P.; Gopala Raju, C.; George, C. Acanthamoeba keratitis in hard contact lens wearer. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 1993, 41, 187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, A.G.M.; Norazah, A. First case of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Malaysia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1995, 89, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.Y.; Chi, S.C.C.; Lam, D.S.C. Good visual outcome after prompt treatment of Acanthamoeba Keratitis associated with overnight orthokeratology lens wear. Eye Contact Lens 2007, 33, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitri, M.; Ratna, S.; Lukman, E. Acanthamoeba keratitis: A challenge in diagnosis and the role of amniotic membrane transplant as an alternative therapy. Med. J. Indones. 2018, 27, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Acharya, M.; Jose, N.; Gandhi, A.; Sharma, S. 18S rDNA sequencing aided diagnosis of Acanthamoeba jacobsi keratitis—A case report. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 67, 1886–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xie, H.-T. Orthokeratology lens-related Acanthamoeba keratitis: Case report and analytical review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 030006052110009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bouten, M.; Elsheikha, H.M. Diagnosis and Management of Acanthamoeba Keratitis: A Continental Approach. Parasitologia 2022, 2, 167-197. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia2030016

Bouten M, Elsheikha HM. Diagnosis and Management of Acanthamoeba Keratitis: A Continental Approach. Parasitologia. 2022; 2(3):167-197. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia2030016

Chicago/Turabian StyleBouten, Maxime, and Hany M. Elsheikha. 2022. "Diagnosis and Management of Acanthamoeba Keratitis: A Continental Approach" Parasitologia 2, no. 3: 167-197. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia2030016

APA StyleBouten, M., & Elsheikha, H. M. (2022). Diagnosis and Management of Acanthamoeba Keratitis: A Continental Approach. Parasitologia, 2(3), 167-197. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia2030016