Exploring the Decisional Drivers of Deviance: A Qualitative Study of Institutionalized Adolescents in Malaysia

Abstract

1. Introduction

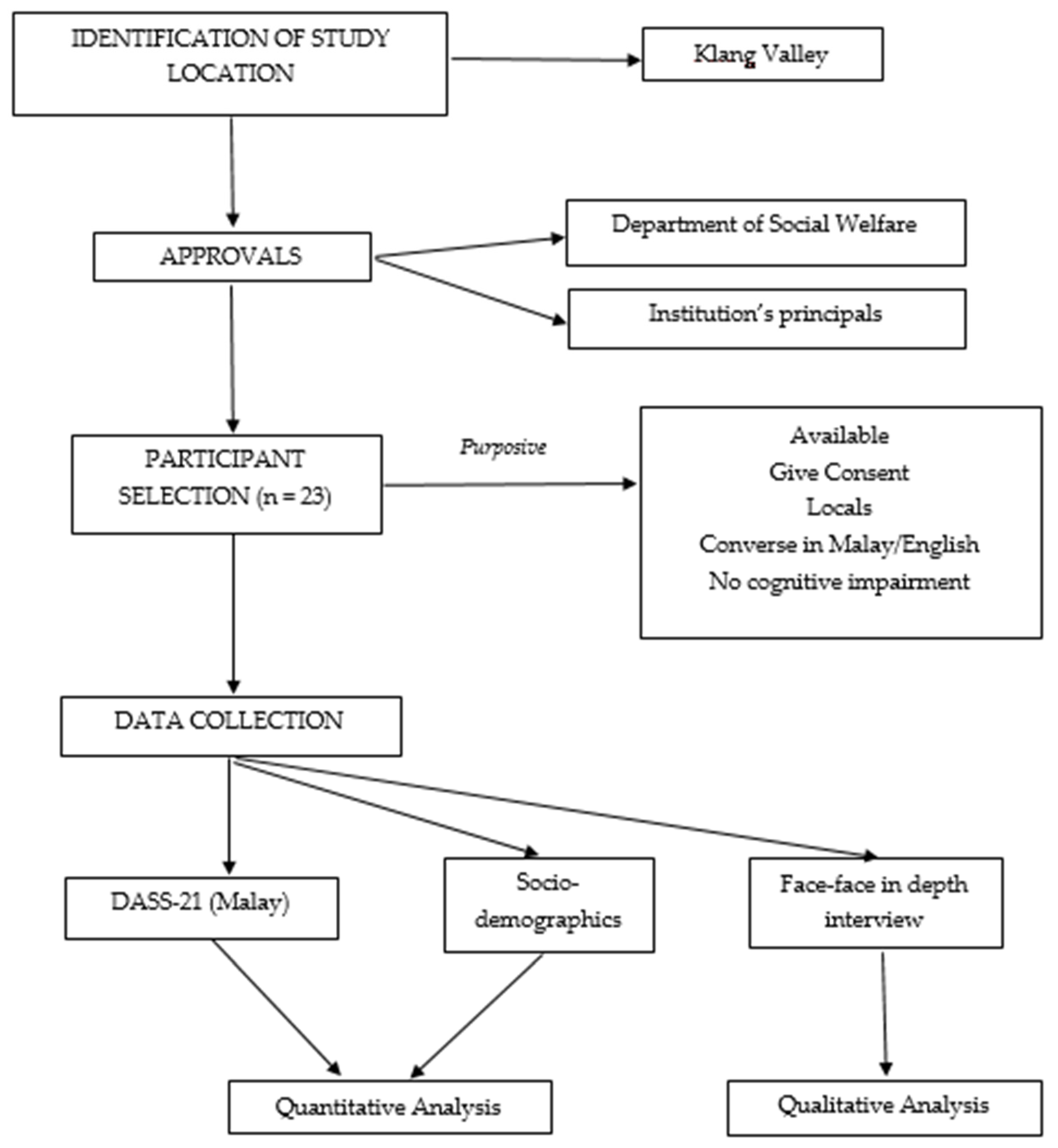

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Data Collection

2.2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Sources of Distress

3.1.1. Traumatic Family Circumstances

3.1.2. Internalizing Domestic Difficulties

3.1.3. Damaging Peer Interactions

3.1.4. Pressure to Conform

3.2. Theme 2: Drivers of Delinquency

3.2.1. Inadequate Parental Support

3.2.2. Laxity in Supervision

3.2.3. Peer Influence

3.2.4. Neighborhood Nuisance

3.2.5. Negative School Experience

3.2.6. Boredom

3.2.7. Social Media and Sexual Initiation

3.3. Theme 3: Adjustment Strategies for Coping with Distress

Substance Abuse

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, M.S.; Evans, T.D. Teacher disapproval, delinquent peers, and self-reported delinquency: A longitudinal test of labeling theory. Urban Rev. 1996, 28, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.E.; Siegel, L.J.; Senna, J.J. Juvenile Delinquency: Theory, Practice, and Law. Teach. Sociol. 1984, 11, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Greer, B.; Church, R. Juvenile delinquency, welfare, justice and therapeutic interventions: A global perspective. BJPsych Bull. 2017, 41, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center on Addiction Substance Abuse at Columbia University. Criminal Neglect: Substance Abuse, Juvenile Justice and the Children Left Behind; National Center on Addiction Substance Abuse at Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2004. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/criminal-neglect-substance-abuse-juvenile-justice-and-children-left (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Shong, T.S.; Abu Bakar, S.H.; Islam, M.R. Poverty and delinquency: A qualitative study on selected juvenile offenders in Malaysia. Int. Soc. Work 2019, 62, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J. The Mental Health Crisis in our Juvenile Detention Centers—Shared Justice. 2016. Available online: https://www.sharedjustice.org/domestic-justice/2016/8/8/the-mental-health-crisis-in-our-juvenile-detention-centers (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Loeber, R.; Farrington, D.P. Young children who commit crime: Epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications. Dev. Psychopathol. 2000, 12, 737–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Campos, E.; García-García, J.; Gil-Fenoy, M.J.; Zaldívar-Basurto, F. Identifying Risk and Protective Factors in Recidivist Juvenile Offenders: A Decision Tree Approach. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.C.S.; Luna, I.T.; Sivla, A.D.A.; Pinheiro, P.N.D.C.; Braga, V.A.B.; E Souza, A.M.A. Risk factors associated with mental health issues in adolescents: A integrative review. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2014, 48, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aida, S.; Aili, H.; Manveen, K.; Salwina, W.; Subash, K.; Ng, C.; Muhsin, A. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among juvenile offenders in Malaysian prisons and association with socio-demographic and personal factors. Int. J. Prison. Health 2014, 10, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (AADK) NADA. Maklumat Dadah 2013 (Drug Statistics 2013). Ministry of Home Affairs, Malaysia; 2014. Available online: https://www.adk.gov.my/orang-awam/statistik-dadah/?lang=en (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention; Centres for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Farrington, D.; Welsh, B.C. Saving Children from a Life of Crime: Early Risk Factors and Effective Interventions; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, S.N.; Zainuddin, A. Social Determinants of Drug Abuse Among Youth in Selangor: A Case Study in Serendah’s Rehabilitation Centre. J. Adm. Sci. 2021, 18, 219–236. [Google Scholar]

- Kuthoos, H.M.; Endut, N.; Selamat, N.H.; Hashim, I.H.; Azmawati, A.A. Juveniles and Their Parents: Narratives of Male & Female Adolescents in Rehabilitation Centres. World Appl. Sci. J. 2016, 34, 1834–1839. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, S.R.; Felitti, V.J.; Dong, M.; Chapman, D.P.; Giles, W.H.; Anda, R.F. Childhood Abuse, Neglect, and Household Dysfunction and the Risk of Illicit Drug Use: The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kort-Butler, L.A. Coping Styles and Sex Differences in Depressive Symptoms and Delinquent Behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 2008, 38, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, S.L.; Lopez-Duran, N.; Lunkenheimer, E.S.; Chang, H.; Sameroff, A.J. Individual differences in the development of early peer aggression: Integrating contributions of self-regulation, theory of mind, and parenting. Dev. Psychopathol. 2011, 23, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, L.C.; Suchman, N.E. Developmental Pathways to Substance Abuse. In Developmental Psychopathology, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 599–619. [Google Scholar]

- Nik Farid, N.; Dahlui, M.; Che’Rus, S.; Aziz, N.; Al-Sadat, N. Early Sexual Initiation among Malaysian Adolescents in Welfare Institutions: A Qualitative Study. Arts Soc. Sci. J. 2015, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, M.E.; Boat, T.; Warner, K.E. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilities; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, K.D.; Ritt-Olson, A.; Soto, D.W.; Unger, J. Variation in Family Structure Among Urban Adolescents and Its Effects on Drug Use. Subst. Use Misuse 2008, 43, 936–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E.T.; Aber, J.L.; Raver, C.C. Child Poverty in the United States: An Evidence-Based Conceptual Framework for Programs and Policies. In Handbook of Applied Developmental Science: Promoting Positive Child, Adolescent, and Family Development Through Research, Policies, and Programs; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2018; pp. 81–136. [Google Scholar]

- Razali, A.; Madon, Z. Issues and Challenges of Drug Addiction among Students in Malaysia. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2016, 3, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L. Qualitative research methods in family medicine: What and why? Malays. Fam. Physician 2008, 3, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, A. Qualitative methods in general practice research: Experience from the Oceanpoint Study. Fam. Pract. 1996, 13, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.; Read, S.; Priest, H. Use of reflexivity in a mixed-methods study. Nurse Res. 2013, 20, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuckett, A.G. Applying thematic analysis theory to practice: A researcher’s experience. Contemp. Nurse 2005, 19, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H.L.; Steinberg, L. Relations between neighborhood factors, parenting behaviors, peer deviance, and delinquency among serious juvenile offenders. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Jalal, F.H. Family Functioning and Adolescent Delinquency in Malaysia. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Troxel, W.M.; Matthews, K.A. What are the costs of marital conflict and dissolution to children’s physical health? Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 7, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, L.; Sewpaul, V. The life experiences of adolescent sexual offenders: Factors that contribute to offending behaviours. Soc. Work. Werk 2014, 50, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ormston, R.; Spencer, L.; Barnard, M.; Snape, D. The foundations of qualitative research. Qual. Res. Pract. A Guide Soc. Sci. Stud. Res. 2014, 2, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G.B. Designing Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korstjens, I.; Moser, A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meester, A.; Aelterman, N.; Cardon, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Haerens, L. Extracurricular school-based sports as a motivating vehicle for sports participation in youth: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, A.F.; Matjasko, J.L. The Role of School-Based Extracurricular Activities in Adolescent Development: A Comprehensive Review and Future Directions. Rev. Educ. Res. 2005, 75, 159–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E.; MacKenzie, M.J.; Schwalbe, C.S.; Brewer, K.B.; Ibrahim, R.W. Prevalence of Mental Health and Behavioral Problems Among Adolescents in Institutional Care in Jordan. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, M.; Goldbeck, L.; Nuetzel, J.; Fegert, J.M. Prevalence of mental disorders among adolescents in German youth welfare institutions. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2008, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulman, E.P.; Cauffman, E. Coping While Incarcerated: A Study of Male Juvenile Offenders. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011, 21, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | ||

| 16–17 | 7 | 38.9 |

| 18–19 | 11 | 61.1 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 11 | 61.1 |

| Female | 7 | 38.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Malay | 18 | 100 |

| Others | 0 | 0 |

| Educational level | ||

| Completed secondary education | 5 | 27.8 |

| Still schooling | 4 | 22.2 |

| Did not complete secondary education | 9 | 50.0 |

| Family structure | ||

| Two biological parents | 5 | 27.8 |

| Single parent | 9 | 50.0 |

| Both parents deceased | 4 | 22.2 |

| Residential area | ||

| Rural | 5 | 27.8 |

| Sub-urban | 12 | 66.7 |

| Urban | 1 | 5.5 |

| History of drug use | ||

| Yes | 10 | 55.6 |

| No | 8 | 44.4 |

| History of sexual intercourse | ||

| Yes | 7 | 38.9 |

| No | 11 | 61.1 |

| Duration of institutionalization | ||

| Less than 6 months | 2 | 11.1 |

| More than 6 months | 16 | 88.9 |

| Total | 18 | 100 |

| Main Themes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sources of Distress | Drivers of Delinquency | Adjustment Strategies for Coping with Distress |

| Subthemes | ||

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| ||

| ||

| ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoga Ratnam, K.K.; Nik Farid, N.D.; Wong, L.P.; Yakub, N.A.; Abd Hamid, M.A.I.; Dahlui, M. Exploring the Decisional Drivers of Deviance: A Qualitative Study of Institutionalized Adolescents in Malaysia. Adolescents 2022, 2, 86-100. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2010009

Yoga Ratnam KK, Nik Farid ND, Wong LP, Yakub NA, Abd Hamid MAI, Dahlui M. Exploring the Decisional Drivers of Deviance: A Qualitative Study of Institutionalized Adolescents in Malaysia. Adolescents. 2022; 2(1):86-100. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoga Ratnam, Kishwen Kanna, Nik Daliana Nik Farid, Li Ping Wong, Nur Asyikin Yakub, Mohd Alif Idham Abd Hamid, and Maznah Dahlui. 2022. "Exploring the Decisional Drivers of Deviance: A Qualitative Study of Institutionalized Adolescents in Malaysia" Adolescents 2, no. 1: 86-100. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2010009

APA StyleYoga Ratnam, K. K., Nik Farid, N. D., Wong, L. P., Yakub, N. A., Abd Hamid, M. A. I., & Dahlui, M. (2022). Exploring the Decisional Drivers of Deviance: A Qualitative Study of Institutionalized Adolescents in Malaysia. Adolescents, 2(1), 86-100. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2010009