Abstract

Objective: To examine associations among psychological distress, perceptions of life changes, and perceptions of family support among college students during the quarantine period of the pandemic. Background: A supportive family can buffer psychological distress during crises. During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, many college students abruptly returned to their family home, disrupting a developmental stage typically oriented toward independence and peer connection. While previous research has highlighted the stressors of this period, less is known about the role of perceived family support in shaping students’ mental health outcomes. Method: Data from a cross-sectional sample of 339 college students were collected. Statistical analysis included a hierarchical multiple regression and moderated moderation to investigate the relationship between the life changes college students experienced due to COVID-19 and distress and how family support moderated this relationship while treating gender as a secondary moderator. Results: Perceptions of worsening life conditions due to COVID-19 were associated with higher levels of distress and vice versa. Perceptions of emotional forms of family support moderated this relationship, but only among male participants. Conclusions: This study contributes to our understanding of the mental health implications of the pandemic on college students by identifying emotional family support as a gender-specific protective factor. Implications: Insights from this study may inform mental health interventions that consider family dynamics and gender-specific coping during large-scale crises. These findings may also guide strategies for supporting students facing the long-term psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Introduction

Throughout history, families have stood at the crossroads of crises, both profoundly affected by disasters and serving as vital sources of support for stress reduction and resilience [1,2]. The COVID-19 pandemic, with its global scope and prolonged impact, brought unprecedented disruptions, including loss of life, economic hardship, and social isolation [3]. The pandemic’s toll on college students has received considerable scholarly attention due to their unique vulnerability as emerging adults and the preexisting mental health crisis among young people, where suicide was already the second leading cause of death [4,5,6].

A small but growing body of literature has emerged on the connections between family dynamics and college students’ mental health during the pandemic. Research indicates that most students lived with their families during campus closures Ref. [7], making family dynamics central to their experiences of coping and adaptation. Moreover, the shift to online learning further blurred the boundaries between academic life and family environments [8]. While studies have shown that family dynamics can either support or strain students’ well-being, depending on factors such as demographics Ref. [9], parental stress Ref. [10], and the quality of parent–child relationships Ref. [11], less attention has been given to disentangling the specific role of perceived family support. In particular, we still know little about how students’ perceptions of family support function as either a protective factor or a source of stress and how this support may buffer the impact of life changes on mental health during the pandemic. Furthermore, little is known about how gender differences may influence these relationships. Addressing these gaps is crucial for developing effective interventions around family support to improve student outcomes during future crises.

Thus, the current study investigates a specific dimension of family relationships—college students’ perceptions of family support—and its association with psychological distress and perceived life changes from before the pandemic through the quarantine period. It further explores whether family support moderated the relationship between perceived life changes and distress symptoms, with attention to how gender may have influenced this moderating effect. This research aims to deepen the understanding of how family dynamics shaped college students’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic and to inform more effective support strategies for students confronting future crises.

2. College Students’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Extensive research gives evidence of the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college students’ mental well-being [12,13]. Students experienced elevated symptoms of depression, anxiety, and fatigue compared to pre-pandemic levels [12,14], and one study identified being a college student itself as an added risk factor for psychological distress [15]. College students, along with children and healthcare workers, were found to be at a heightened risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [16]—potentially due to their developmental life stage, disruptions to key social supports, and the collapse of routine structures such as school, work, and peer interaction.

Additional studies have shown that students with preexisting depression experienced higher rates of anxiety, stress, and difficulty concentrating than peers without such histories [17], compounding their vulnerability during the pandemic. These heightened levels of distress have been linked to a range of factors, including concerns about academic performance [18], sleep disturbances [19], increased substance use [20], suicidal ideation [21], disrupted social lives [22], low resilience [23], and fear of infection or loss [24]. A longitudinal study tracking students across three time-points—pre-, mid-, and post-pandemic –found that stress levels continued to rise, demonstrating the lasting psychological toll of the pandemic [25].

College students are at a formative stage of life both socially (being at the pinnacle of developing autonomy and career pathways) and neurologically (as “appraisal-focused coping skills” are still being developed) [26,27]. Research shows that the prefrontal cortex, a brain region responsible for executive functioning and emotional regulation, continues to mature into the mid-20s [26,27,28]. While this has been cited as a possible contributor to challenges in coping with trauma and uncertainty, recent studies also highlight the importance of contextual factors, such as life experience, social support, and individual resilience, in managing stress [29,30]. Thus, vulnerability in this age group is not due solely to neurological development, but rather to a complex interaction of developmental and environmental factors.

This period is also marked by an increased susceptibility to psychosocial challenges [26,27,31,32,33]. Three-quarters of mental illnesses begin before age 24, and many college students experience the onset of symptoms during these formative years [34]. As a result, mental health challenges can significantly interfere with academic performance and long-term well-being. Understanding these unique vulnerabilities is essential for identifying how and when to intervene—especially in the face of crisis-level disruptions, like the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. College Students’ Perceptions of Life Changes During the Pandemic

Understanding how college students perceived changes in their lives from pre-pandemic to during the quarantine stage of the pandemic is important for exploring their responses to stressors. The Family Stress literature shows that both broader social contexts and individual experiences shape responses to crises [35,36,37]. During the pandemic, disruptions across every societal institution—higher education, labor markets, and families—created a complex backdrop for students’ experiences. However, research indicates that students’ subjective experiences of these disruptions varied and were influenced by demographics, socioeconomic contexts, and individual factors [38,39].

Many college students and their families faced challenges, including job losses, school and daycare closures, and limited access to essential services such as non-COVID healthcare and disability support [40]. These disruptions strained family resources and altered students’ support systems. The abruptness of campus closures, uncertainty about returning, and the rapid shift to remote learning compounded these challenges. Students lost access to on-campus resources, such as libraries, tutoring services, peer activities, and mental health support [41].

The research highlights the diversity of students’ experiences during the pandemic. While some struggled with academic difficulties, social isolation, and new family responsibilities [38], others reported positive experiences, including opportunities for personal growth and new skills [42]. Given this variability, it is important to investigate the extent to which students’ perceptions of the changes they experienced were related to psychological distress and whether family support made a difference in this relationship.

4. The Significance of Family Support During COVID-19

The research has long established the critical role of family in the lives of college students. During this pivotal stage of development and the transition to adulthood, family support has served as a crucial source of emotional stability and a buffer against distress [5,43,44,45,46,47]. Although college students often develop diverse social networks [48], they have continued to rely on their families for enduring support, which peers and mentors may not provide [44,49]. Even extended kinship ties have contributed positively, fostering higher self-worth, better grades, and lower levels of mental illness [49].

The COVID-19 pandemic abruptly disrupted the conventional trajectory of emerging adulthood, stripping many college students of their independence and forcing a return to the family home. This sudden transition placed considerable strain not only on students, but also their families. The research from prior crises underscores the importance of family support during disasters [50,51]. For example, studies following Hurricane Katrina found that families demonstrated greater resilience when they were characterized by low conflict and high connectedness [52]. More broadly, family support has been shown to buffer psychological distress, whereas family conflict tends to exacerbate it [53,54,55,56,57]. Parental and familial support also serves as a key predictor of children’s long-term mental health outcomes [58,59]. However, these experiences were not uniform across all households. Although this study does not directly investigate the sources of that variation, it is important to recognize that students’ perceptions of being home during the pandemic were likely shaped by a range of contextual factors, including preexisting family dynamics, cultural expectations, and household circumstances.

For many students, this sudden transition was a source of psychological strain, particularly when it disrupted growing independence or reactivated family tensions. The pandemic forced students into living arrangements that were not always conducive to their well-being. Living at home during the pandemic was characterized as a potentially turbulent experience for many college students [60]. Longitudinal research found a decline in family harmony during the pandemic, illustrating the strain on relationships [61]. Parental distress further shaped these dynamics; feelings of sadness and loneliness among parents hindered parenting quality and contributed to students’ negative internalizing and externalizing behaviors [54,62].

The quality of family relationships during the pandemic played a critical role in shaping college students’ mental health. Strained family dynamics and familial pressures were associated with negative mental health outcomes [60,63]. However, family disruptions predicted depressive and anxiety symptoms primarily when the relationship quality was low [64]. Dysfunctional home environments were also linked to poorer mental health overall [65], with family relationships emerging as one of the most significant predictors of psychological disorders [66].

While family conflict exacerbated mental health issues, several studies demonstrated the protective role of positive family dynamics. Family support consistently emerged as a buffer against mental health challenges [60,67]. Positive family communication buffered distress by fostering shifts in attitudes toward mental health support, increased self-efficacy, and reduced self-stigma [55,68,69]. Everyday micro-practices, such as encouraging words, shared activities, or small gift, contributed to students’ improved mental well-being [70]. Additionally, frequent face-to-face conversations or talking on the phone with family members reduced anxiety and depression [24,71].

The impact of family dynamics on mental health varied across cultural and social contexts. For example, a study of college students living on the U.S.–Mexico border found that while most reported no changes in their family relationships, those experiencing negative changes reported worse mental health outcomes. Conversely, students who experienced positive changes reported stronger familism values, which were linked to better mental health [72]. Additionally, family support was particularly crucial for vulnerable student populations. Among LGBTQ college students, affirming family relationships significantly reduced distress, demonstrating the protective role of supportive family dynamics for marginalized groups [73].

Overall, the pandemic magnified the importance of supportive family environments for college students. While the increased proximity to family during lockdown generated both resilience and distress, these outcomes were far from uniform. The quality of family relationships—shaped by cultural norms, social contexts, and individual identity—played a central role in determining whether students experienced support or strain. Supportive and communicative family dynamics helped buffer mental health challenges, whereas conflict or a lack of understanding often intensified stress. Despite extensive research on the role of family in college students’ mental health, important gaps remain—particularly in distinguishing the effects of emotional versus tangible forms of support. Most existing studies focus on emotional or relational support, leaving the impact of practical, material assistance underexplored [42,74]. Clarifying the unique contributions of these distinct support types is essential for designing more targeted and inclusive interventions.

5. Types of Family Support: Emotional and Instrumental Support

Family support takes different forms, each with distinct implications for psychological well-being. Two primary forms—emotional support and instrumental support—operate through different mechanisms and meet different needs. It is important to understand their distinct contributions to students’ mental health and perceptions of family support.

5.1. Emotional Support

Emotional support involves empathetic, understanding, and nurturing relationships. According to the Family Stress literature, the “caregiving system” underscores the importance of warm, responsive, and competent support in promoting well-being and reducing PTSD symptoms after traumatic events [36]. This study explores whether students felt loved, had someone to talk to, and felt their concerns were validated. The research highlights that relational support fosters feelings of safety, security, and care, which help individuals manage mental well-being during crises [74,75,76]. Caregivers play a critical role in building coping mechanisms and appraisal skills by helping students process stressors, interpret challenges, and establish routines that restore stability [74]. Emotional support contributes to the positive development under adversity by enhancing problem-solving skills, competence, and self-esteem. It can also strengthen family cohesion, fostering a reciprocal relationship where cohesive families consistently provide emotional support. When family members feel connected and responsible for one another, they are more likely to offer comfort and validation during times of distress [76].

5.2. Instrumental Support

Instrumental support encompasses tangible, practical assistance, such as providing resources or services essential for survival, safety, and restoring daily routines during periods of heightened need [74]. Although instrumental support has received less attention in the literature, research indicates that resource loss due to catastrophes increases the risk of mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, and distress [77]. Family stress theory suggests that limited resources can trigger cascading risks, accumulating stressors that undermine stability and functional capacity [78].

Unlike emotional support, which offers psychological comfort, instrumental support directly addresses material needs and logistical challenges. Studies on disasters reveal that resource loss heightens mental health risks, but instrumental support can mitigate distress, especially in the immediate aftermath of traumatic events [36,42]. During the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, instrumental support was linked to lower depression levels among young adults [42]. Additionally, a study of college students who survived Hurricane Katrina found that instrumental support—such as access to food, clothing, and shelter—significantly reduced PTSD symptoms, even more than emotional support [74]. Practical assistance played a pivotal role in stabilizing students’ lives, as many had limited resources [74]. However, how these dynamics unfolded during the prolonged disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic remains less clear.

For college students navigating the pandemic’s disruptions, instrumental support may have included assistance with tuition payments, the provision of meals, or creating suitable home study spaces for online learning. Under normal circumstances, colleges offer services such as childcare, housing support, and transportation assistance [79,80]. However, campus closures during the pandemic caused many students to lose access to essential resources, including on-campus jobs, tutoring services, health and disability accommodations, and food pantries [41]. Compounding these challenges, young adults experienced disproportionate job losses in the wider labor market, as they were overrepresented in low-wage service and retail sectors—some of the hardest-hit industries [81,82].

Consequently, many college students became acutely vulnerable, with their experiences shaped by their family’s ability or inability to provide tangible support. For instance, a parent’s sudden job loss could jeopardize a student’s ability to remain enrolled in college, leading to feelings of helplessness and distress. Conversely, if a parent could fund an online summer class, it might help the student reframe the loss of an internship as an opportunity for academic progress during the pandemic.

Understanding the distinct contributions of family-provided instrumental support to college students’ mental well-being, alongside emotional support, is essential for developing policies that promote family resilience and student well-being during future crises.

6. Gender as Moderated Moderator

Gender disparities significantly influence experiences during crises, shaping coping strategies and support systems. Research consistently shows that women face greater vulnerability during disasters, experiencing more severe mental distress and relying more on social support than men. Studies from the COVID-19 pandemic reinforce this trend, showing that female college students reported more pronounced mental health impacts than their male peers [12,83]. In addition, previous research has found that college women, in general, rely more heavily on family support to maintain their mental well-being during stressful periods [15,84,85]. Yet, despite these well-documented patterns, the ways in which family support shaped mental health outcomes or college women during the COVID-19 pandemic remain underexplored. This study investigates whether gender moderated the relationship between family support, psychological distress, and perceptions of life changes caused by the pandemic, highlighting the need to better understand gender differences in how support is experienced and its impact on well-being.

Gender-specific roles and responsibilities further shaped students’ experiences, particularly during quarantine. Women have historically shouldered disproportionate caregiving responsibilities during crises, a phenomenon known as “disaster labor” [26]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, caregiving responsibilities disproportionately fell on women, including adolescent girls, who spent significantly more time on domestic tasks than their male peers [54,86]. Such patterns, driven more by gender identity than employment status, often placed female college students in caregiving roles, such as caring for younger siblings [87].

The unequal distribution of caregiving responsibilities likely influenced college women’s perceptions of family support, contributing to increased psychological strain. Stress contagion, where individuals absorb stress from overwhelmed family members, may have heightened their distress [88]. Additionally, conflicts between academic responsibilities and family obligations may have diminished the perceived benefits of family support. In contrast, male students, who are typically less reliant on family support, may have experienced an increased dependence or family tension due to disrupted coping routines. Although male students reported lower distress levels, they were also less likely to seek help for mental health concerns, increasing their risk for isolation, substance abuse, and suicide [89]. Gendered expectations and caregiving roles may help shape students’ experiences and influence how effectively family support mitigates psychological distress in times of crisis.

7. Current Study

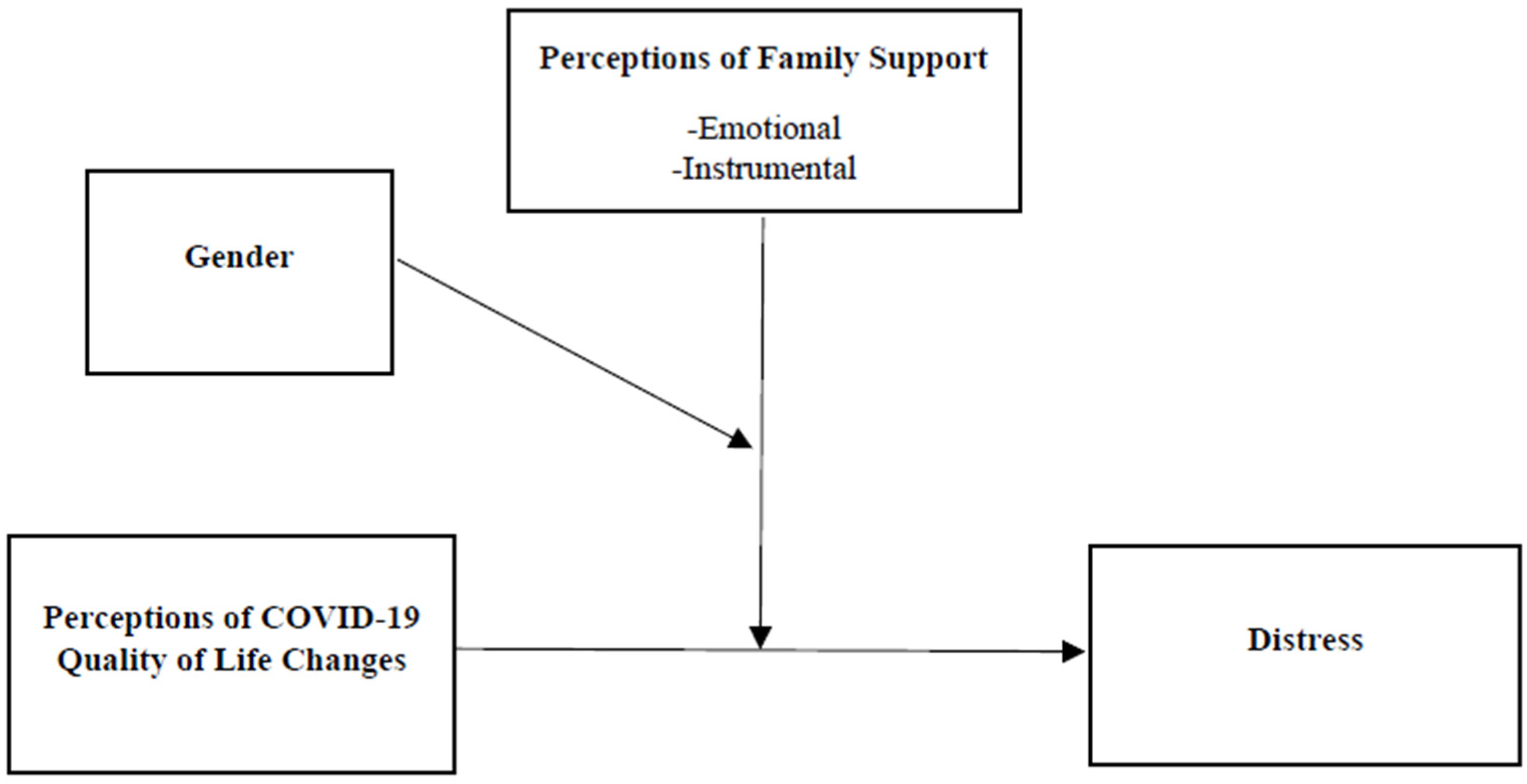

The goal of the current study was threefold and is illustrated in Figure 1. We first sought to investigate the relationship between college students’ psychological well-being and their perceptions of pandemic-related changes. Subsequently, we aimed to examine the moderating role of family support on the relationship between perceptions of COVID-19-induced life changes and levels of psychological distress. Finally, we aimed to explore how gender moderated the moderating influence of family support.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

We first hypothesized that shifts in perceived changes in life circumstances—spanning from pre-pandemic to lockdown conditions—would help predict psychological distress. An inclination towards a worse life appraisal during the pandemic would correspond to an increase in psychological distress. Conversely, perceiving an improvement in life circumstances would be associated with a decrease in psychological distress. Secondly, we hypothesized that family support, encompassing both emotional and instrumental dimensions, would buffer the association between perceptions of COVID-19 life changes and psychological distress. Lastly, we posited that gender would play a moderating role in the aforementioned family support interaction, particularly concerning emotional family support. Consistent with gendered patterns of coping and support-seeking highlighted in the Family Stress literature, we anticipated that the moderating effect would be more pronounced in women as compared to men.

8. Method

8.1. Procedure

This study employed a cross-sectional design at a small suburban undergraduate campus, part of a larger public university system situated in the Northeastern United States—an early COVID-19 hotspot. Data collection occurred during a crucial period, from 5 June to 22 June 2020, therefore capturing students’ distress levels at the peak of the lockdown. It is noteworthy that the county’s cumulative cases per 100,000 increased by 49% within this timeframe, surging from 842 on 5 May to 1252 on 22 June. Importantly, the local region had been under lockdown orders since 25 March, and the university had transitioned to remote learning throughout the Spring 2020 semester, a policy that remained in place during the summer months.

This research was approved by the university’s institutional review board, with data collection facilitated through an online survey administered via the Qualtrics platform. Access to the survey was provided to all enrolled students through a university email listserv and within various online courses. Participation criteria stipulated being an enrolled student and at least 18 years of age. Rigorous informed consent protocols were followed to ensure voluntary, anonymous, and non-coerced participation. While some instructors incentivized participation by offering extra credit points, no additional compensation was provided. To mitigate potential coercion effects, an online alternative assignment, equating in time and effort to the survey, was offered to students. Completion of either the survey or the alternative assignment redirected participants to a distinct URL, where they could provide identifying information for their respective course instructors, thereby maintaining participant anonymity. To minimize duplicate submissions, the Qualtrics platform’s “Prevent multiple submissions” function was employed. On average, participants spent 8 min and 23 s completing the survey, with a single outlier case where a participant began the survey and later returned to complete it after several hours.

8.2. Participants

The participation rate was 35%, with 339 out of 960 enrolled students successfully completing the survey. The mean age of participants was 20.8 years (SD = 3.1), and on average, respondents were in their 5th semester of college (M = 4.9, SD = 2.3). A majority of participants identified as women (n = 206, 60.8%) with a small fraction <1% (n = 3) reported as non-binary or preferred to not answer. In terms of household income distribution, slightly over half of the participants (n = 173, 51%) came from households earning more than USD 100,000 annually, and approximately one-in-five respondents (n = 66, 19.5%) reported households earning USD 200,000 or more. Conversely, almost a fifth (17.7%) (n = 60) indicated household incomes below USD 60,000 per year, with a subset of this group (n = 32, 9.4%) coming from households earning less than USD 30,000 annually. A significant proportion of participants (n = 207, 61%) had at least one parent with a four-year college degree.

Almost half of the participants (n= 149, 44%) reported being employed during this initial phase of the pandemic. The racial and ethnic distribution was predominately self-reported as white (n = 235, 63%) with comparatively lower representations in other categories: Asian (n = 59, 15.9%), Latinx (n = 27, 7.3%), black and/or African American (n = 21, 5.6%), American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 7, 1.9%), Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (n = 1, 0.2%), and other (n = 22, 5.9%) (Note: the cumulative percentage of race/ethnicity responses exceeds 100% due to participants identifying with more than one category.) The living arrangements of participants during lockdown revealed that the majority resided with parent(s) (n = 293, 86.4%), while nearly two-thirds lived with sibling(s) (n = 218, 64.3%). A minority of respondents (n = 35, 10%) lived with other family members. Moreover, an overwhelming majority (n = 322, 95%) of participants were located in the Northeast of the United States, an area characterized by stringent and comparably uniform quarantine measures.

8.3. Measures

Sociodemographics. This study controlled for a range of sociodemographic factors to align with prior research on mental well-being and the potential for confounding influences in the regression model and moderation analysis. These factors encompassed gender identity (coded as 0 = man, 1 = woman), age, household income (coded as 0 = >USD 100,000, 1 = <USD 100,000), employment status (coded as 0 = unemployed, 1 = employed), and first-generation college student status (coded as 0 = at least one parent had a 4-year college degree, 1 = no parent had at least a 4-year college degree). Gender identity was analyzed by considering male and female participants exclusively, acknowledging the minimal number of cases that reported identification outside the gender binary. It is worth noting that these gender-diverse cases were included in all other analyses. The demarcation for household income was set at USD 100,000, a figure reflective of both the median household income for the campus’ zip code and 1½ times the median income of the broader metropolitan region [90]. This demarcation was strategically established to differentiate between students from middle to middle-lower socioeconomic backgrounds and those belonging to more privileged upper middle-class and above backgrounds.

Psychological Distress. Psychological distress, the dependent variable, was measured with the Kessler 10 Psychological Distress scale which is a 10-item Likert style tool (on a scale of 1 to 5) for screening anxiety and depressive symptoms as experienced in the previous 30 days. The K10 is widely considered a reliable means of measurement [91]. It asks ten questions, including the following: In the past 30 days how often…did you feel tired for no good reason?…did you feel nervous?…did you feel hopeless? The cumulative responses to these ten questions provided the K10 score, where a higher sum score indicated higher psychological distress. For contextual interpretation, one utilization of the K10 measurement considered a score of 22 or beyond as indicative of being at risk of having a mental health disorder [92]. Cronbach’s alpha, a coefficient of reliability, showed high internal consistency (α = 0.92) for this measure.

COVID-19 quality of life changes were measured using an 11-item scale to assess students’ perceptions of how various aspects of their lives changed during the COVID-19 lockdown compared to pre-pandemic conditions. This measure was developed by the authors. Because this study was conducted during the earliest months of the pandemic, no validated instruments yet existed to capture the scope and nature of the disruptions students were experiencing. Participants responded to the question, “To what extent did your life improve or worsen during the COVID-19 lockdown compared to your life before the pandemic?” on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (much worse) to 5 (much better) for 11 different items. The items captured a wide array of life domains related to living arrangements, academic stability, financial strain, and social relationships that emerged as common areas of upheaval. Responses were reverse-coded so that higher scores indicated a greater deterioration in quality of life. The possible total score ranged from 11 (strong improvement in quality of life) to 55 (extreme deterioration in quality of life).

To assess the underlying structure of the scale, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using principal component analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was acceptable (KMO = 0.77), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (χ2 = 780.65, p < 0.001), indicating that the data were factorable. The analysis identified four distinct components reflecting different dimensions of students’ experiences: (1) college stability and home adjustment, (2) living conditions and health, (3) financial well-being and employment, and (4) social and romantic relationships.

Despite the identification of multiple components, the 11-item scale demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = 0.767), supporting its use as a single composite measure of overall perceived life changes during the pandemic. Given that the identified factors were conceptually interrelated and together represent a holistic measure of students’ COVID-19 experiences, we opted to retain the full scale as a single variable for analysis. This decision supports a holistic interpretation of students’ perceived quality of life changes during the pandemic.

Family support. The items that made up the family support measure were adapted from the NIIH (National Institute of Health) Toolbox for emotional and instrumental support. The emotional component comprised seven questions including, “People in my family listen to my problems” and “there are people in my family who understand me”. The instrumental component was also based on seven items and included questions such as, “my family helps me with my living costs”, “my family helps me fulfill my basic needs such as providing food or cooking meals”, and “my family helps me access my healthcare needs”. In both instrumental and emotional support scales, respondents were asked to respond using a Likert format from 1 (very low support) to 5 (very high support). Both scales were found to have high internal consistency: the instrumental support scale had a reliability coefficient of α= 0.89. The emotional support scale had a reliability coefficient of α= 0.95.

8.4. Statistical Procedures

SPSS v.29 was used to perform all statistical analysis. Missing data on all study variables were assessed and found to be missing at random. Categorical variables had less than 3% missing data and were handled with mode imputation. Continuous variables had less than 5% missing data and were managed with the expectation–maximization algorithm before the indices were computed. Multicollinearity statistics were computed to determine that all measures were within acceptable ranges for the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) (below 10), Tolerance (above 0.1), and Durban–Watson (between 1.5 and 2.5). Frequencies and percentages were computed for categorical variables, while for continuous variables means, standard deviations, and ranges were calculated. Correlations between all variables were then computed.

A hierarchical linear regression was conducted to test the main effects of the study variables on psychological distress. Predictors were ordered hierarchically in three steps. In step one, sociodemographic variables were entered as covariates to assess their contributions prior to an assessment of the independent variable contributions. In step two, the COVID-19 life changes variable was entered. In step three, the two forms of family support, emotional and instrumental, were entered to evaluate the main effects of perceived family support and the distinctions between emotional and instrumental forms. Moderation analyses were conducted using PROCESS v4.2 to investigate whether family support (emotional and/or instrumental) moderated the relationship between perceptions of COVID-19 life changes and psychological distress. Gender was treated as a secondary moderator to examine whether gender influenced the family support moderators. Covariates were added to the PROCESS models. Moderators were tested at three levels: one standard deviation below the mean, the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean.

9. Results

9.1. Descriptive Statistics

Univariate statistics for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Frequencies and percentages are presented for categorical variables, means, and standard deviations, and ranges are provided for continuous variables. Correlations are presented in Table 2. Psychological distress was significantly and positively associated with COVID-19 quality of life changes, gender (being a woman), and household income (being low-income). Psychological distress was significantly and negatively associated with having a paid job, perceived emotional family support, and perceived instrumental family support.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for study variables.

Table 2.

Simple bivariate correlations.

9.2. Hierarchical Multiple Regression

The hierarchical multiple regression result is presented in Table 3. Multicollinearity statistics were all within acceptable ranges. Standardized regression coefficients in the first model show that gender (being female) (β = 0.17, p < 0.01) and household income (being of lower income status) (β = 0.14, p < 0.05) were associated with an increase in psychological distress, while job status (being employed in a paid job) (β = −0.12, p < 0.05) predicted a decrease in psychological distress. In the second model, standardized regression coefficients show that gender (being female) (β = 0.15, p < 0.01) and perceptions of COVID-19 life changes (β = 0.398, p < 0.001) were associated with increased psychological distress. Standardized regression coefficients in the final model show that gender (being female) (β = 0.12, p < 0.01) and perceptions of COVID-19 life changes (β = 0.305, p < 0.001) were associated with an increase in psychological distress, while perceptions of emotional family support (β = −0.275, p < 0.001) predicted a decrease in psychological distress. The total model explained 28% of the variance in psychological distress. Perceptions of COVID-19 life changes and covariate variables explained 22% of the variance in distress symptoms, while the covariates alone explained only 6% of the variance in distress symptoms.

Table 3.

Hierarchical multiple regression.

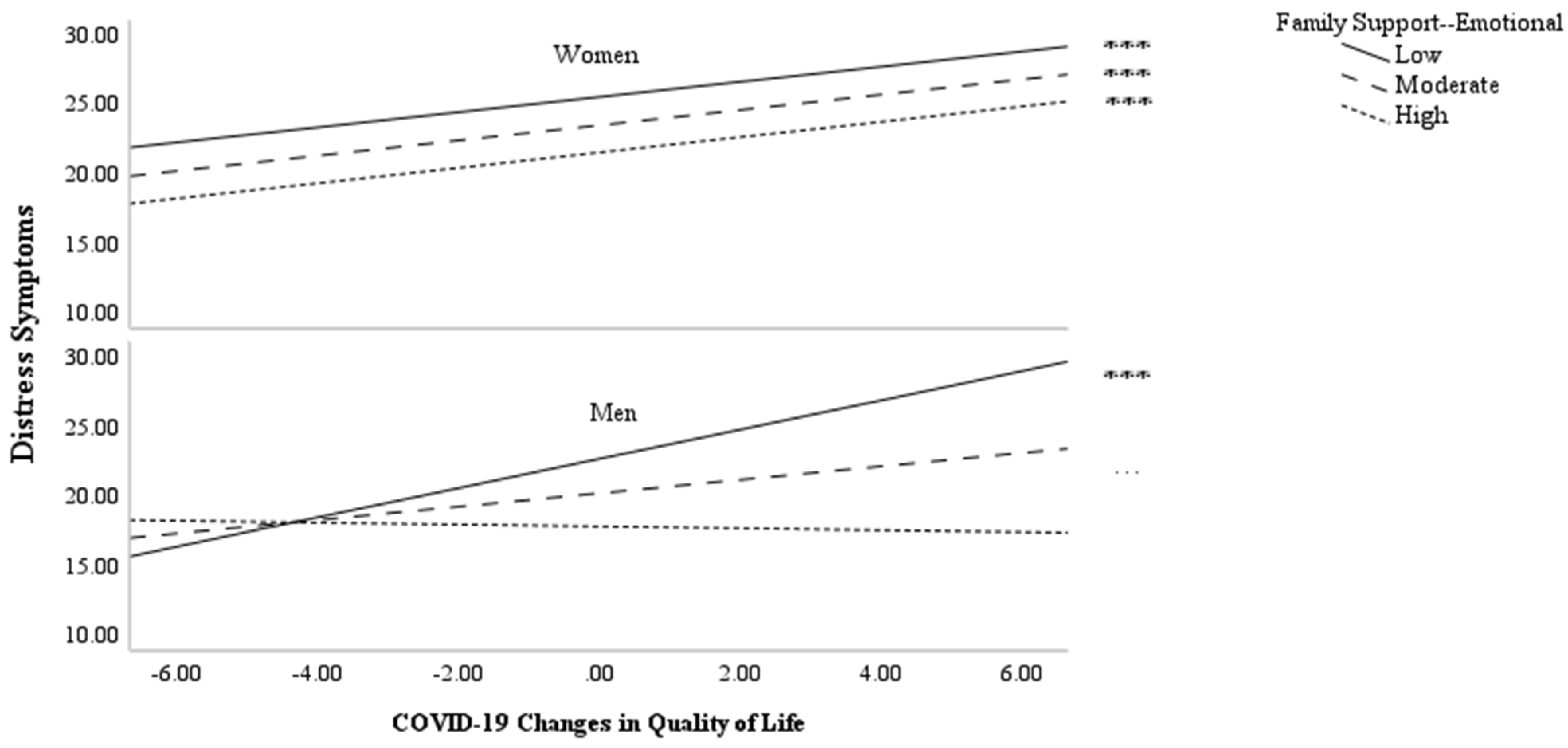

9.3. Moderated Moderation Analysis

In moderated moderation analyses, the perceived emotional family support was found to have a significant three-way moderating influence on the relationship between perceptions of COVID-19 quality of life changes and psychological distress with gender as the secondary moderator (F (1, 324) = 11.08, p = 0.001, ΔR2 = 0.02). Decreased emotional family support and increased COVID-19 life changes were found to be predictive of increased psychological distress for women, while there was no interactive effect (β = 0.000, p = 0.964). For men, there was a significant interaction (β = −0.08, p =< 0.001). As can be seen in Figure 2, the perceived emotional family support moderated the relationship between perceptions of COVID-19 life changes and psychological distress for men. The conditional effect of perceived emotional family support was significant for men who reported low levels (1 SD below the mean) (β = 1.05, p < 0.001) and moderate levels (at the mean) (β = 0.48, p < 0.001) of emotional family support. However, the conditional effect of perceived COVID-19 life changes on psychological distress at the high level of perceived emotional family support (1 SD above the mean) was not statistically significant. In the second moderated moderation analysis, perceived instrumental family support was found to have a nonsignificant three-way moderating influence on the relationship between perceptions of COVID-19 quality of life changes and psychological distress with gender as the secondary moderator (F (1, 324) = 1.25, p = 0.2637, ΔR2 = 0.002).

Figure 2.

Three-way interaction with family support moderating association between COVID-19 changes in quality of life and distress symptoms with gender as secondary moderator *** p < 0.001.

10. Discussion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, college students were triangulated between three different forces of change—personal/individual disruptions during a critical developmental stage as emerging adults, their role readjustment in the family, and external social, political, and economic forces induced by the pandemic. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationships between college students’ mental well-being, the changes they perceived to have experienced as a result of COVID-19, and their perceptions of family support. Another aim was to explore whether gender moderated the relationship between perceptions of change and psychological distress with gender as a secondary moderator.

The significant association we found between psychological distress and perceived changes as a result of COVID-19 supports our first hypothesis and lends additional support to earlier studies that have raised alarm about the psychological toll arising from the pandemic and the impact on college students in particular [12,13]. Our results show a strong association between a perceived decline in quality-of-life circumstances attributed to the pandemic and higher levels of psychological distress and vice versa. When quality of life was perceived as having worsened during lockdown, psychological distress increased. And when participants perceived their lives as better, psychological distress decreased.

A second aim of this study was to investigate the moderating roles of different types of family support on college students’ psychological distress during the early stage of the pandemic. Our second hypothesis was partially supported by our results. We found strong correlations between emotional family support, instrumental family support, and psychological distress in bivariate analyses. But in the regression analysis, after accounting for key sociodemographic variables and covariates, it was emotional, and not instrumental, family support that predicted lower levels of distress. When college students felt loved, when they had people to talk to, and when they felt understood and validated in their concerns they had less distress symptomology than those who did not feel like they had this same kind of support from their families. Our findings coalesce with previous scholarship that has demonstrated the significance of emotional support for young adults’ mental health [5,46,93,94] and suggests that emotionally supportive family relationships can help alleviate distress among college students. They also reinforce insights from the Family Stress literature, which emphasize the protective role of compassionate family dynamics during times of crisis, as well as the heightened vulnerability students may face when such support is absent.

The nonsignificance of instrumental support in our regression analysis sheds light on the already mixed findings in the literature regarding whether practical assistance leads to improved mental health outcomes. Given the widespread disruptions of the pandemic, we anticipated that college students might be particularly sensitive to tangible support from the family—such as financial help, transportation, or assistance with housing or food. Families themselves were often under strain due to job loss, healthcare access challenges, and economic uncertainty. Prior studies suggest that resource loss during traumatic events increases vulnerability to mental health problems [77].

In light of this, our finding appears counterintuitive. For example, among college students affected by Hurricane Katrina, tangible family support was found to significantly alleviate distress [74]. One possible reason for the difference is that Hurricane Katrina posed a more immediate physical threat, whereas the pandemic’s threat—while pervasive—unfolded more gradually and unevenly. Thus, instrumental support during the pandemic may have had less direct psychological impact in the early stages.

Importantly, a nonsignificant result does not imply that instrumental support—such as help paying for a summer class or getting to work—was irrelevant to students’ well-being. Rather, it suggests that such support may not have had a direct effect on mental health, at least not in the immediate context of the pandemic’s onset [47]. It is also possible that the impact of instrumental support varied by socioeconomic background. Lower-income students may have been more attuned to the presence or absence of tangible help, given their heightened exposure to financial insecurity, job loss, and reduced access to both academic and mental health resources [95,96,97]. Economic strain may have also limited families’ ability to provide emotional support, potentially compounding distress [62]. By contrast, students from higher-income households may have experienced fewer disruptions or had access to broader safety nets, which could buffer the psychological strain.

In our study, household income was significantly associated with both instrumental support and psychological distress in bivariate analyses. However, once we included students’ perceptions of COVID-19 life changes and family support in the regression model, income no longer predicted distress. This suggests that the effect of income may be mediated by how students experience and interpret their circumstances—particularly their sense of emotional support and perceived disruption. In other words, it may not be income itself, but the subjective meaning students make of their situation that most strongly predicts psychological well-being. This would reinforce the importance of centering students’ perceptions in the study of mental health and highlights the complex, often indirect pathways through which structural factors, like income, exert their influence.

The third aim of this study was to explore the interaction between gender and the moderating influence of family support. The results partially support our third hypothesis. We expected emotional family support to significantly moderate the relationship between COVID-19 life changes and psychological distress, assuming this effect would be existent for both genders, albeit stronger for women. We found significant three-way interactions among both men and women, in that emotional family support significantly interacted with the relationship between perceptions of pandemic changes and psychological distress. However, the results unexpectedly demonstrated a significant moderating effect only among college men. This is despite the fact that gender (being female) predicted higher distress scores [84,85].

Although this finding deviated from our original hypothesis, it aligns with prior research suggesting that men may be particularly sensitive to the presence (or absence) of social support due to prevailing norms which discourage emotional vulnerability [98]. Prior studies indicate that men are less likely to independently seek psychological help and may therefore experience greater mental health benefits when family support is available [99]. In contrast, women may already utilize alternative social coping mechanisms, such as peer support, which could reduce their reliance on family support and the relative impact of family support on their distress levels [100].

Among men, the most pronounced association between perceptions of COVID-19 changes and psychological distress was evident at the lowest level of emotional family support. Notably, the relationship between these perceptions and distress remained statistically significant but weaker at a moderate level of support. This pattern suggests that additional family support correlated with reduced distress symptoms in men. Interestingly, at the highest level of family support, the moderator’s influence on the relationship between psychological distress and perceptions of life changes was nonsignificant. This may reflect a threshold effect: at the lowest level of emotional support, men experience heightened distress. As support increases, distress decreases—but only up to a point. At the highest levels of emotional support, further gains may offer diminishing returns; perhaps because men already feel emotionally secure and perceive themselves as coping independently.

This pattern may also reflect broader gendered differences in emotional self-regulation and perceived autonomy. While prior research suggests that men in distress are more likely to benefit from explicit emotional support, women—often socialized to process emotions more openly and draw on informal peer networks—may not experience comparable mental health gains from family interactions alone [100]. Moreover, the role of perceived autonomy may be key: men may interpret increased family support as a welcomed buffer against distress, whereas women, who often face greater social expectations to maintain emotional well-being within family settings, may not find the same level of relief, particularly if support feels obligatory or tied to caregiving roles.

Additional themes in the literature help explain why perceptions of emotional family support did not moderate psychological distress among college women in the context of COVID-19 life changes. Haney and Barber (2022) argue that women—especially during crises—often assume the role of emotional caretakers within the household, which increases their emotional burden and constrains the benefits they may receive from support offered by others. In such contexts, family-based emotional support may be perceived less as a source of relief and more as an extension of caregiving responsibilities [87]. This corresponds with bioecological research on “disaster labor”, which highlights gendered expectations that women will “pull things together” for the family during crises, often while suppressing their own struggles [26]. Even when support is available, it may be interpreted as part of their expected role rather than a distinct form of care. In a North American study conducted during the pandemic, Haney and Barber (2022) found that although women reported increased domestic responsibilities, their satisfaction with these roles remained unchanged—suggesting a possible internalization of these conditions [87]. In our sample, this internalization may have weakened the psychological salience of family support. In other words, while emotional family support was correlated with psychological distress, it did not function as a moderator among women—perhaps because it was not experienced as a distinct or meaningful variable in their coping process.

These findings have practical implications for designing preventive mental health interventions for college students. The moderating effect of emotional family support—particularly among male students—suggests that interventions should consider how to engage families in supportive roles, especially for students less likely to seek help independently. Programs that promote family communication, normalize emotional vulnerability for men, and provide education about recognizing signs of distress may be particularly beneficial. At the same time, interventions should also account for students who may lack reliable family support by promoting alternative sources of emotional connection, such as peer networks, mentoring programs, or campus-based support groups.

11. Future Directions

Future studies should explore whether these findings hold across different cultural and socioeconomic contexts to better understand the nuances of gendered emotional support and psychological distress during crises. It is particularly important to explore gender-specific stressors among college students in relation to family dynamics and their impact on mental health disparities. For instance, understanding why college men may be more vulnerable to a perceived lack of family support is critical, especially given public concerns linking masculinity, distress, and suicide [89]. Research on mass trauma suggests that boys are more likely to externalize distress (e.g., belligerence), while girls tend to internalize symptoms (e.g., anxiety) [59]. These gendered expressions, coupled with men’s lower likelihood of recognizing or seeking help for mental health problems, underscore the urgency of investigating how support is perceived and processed differently across genders—particularly in light of pandemic-related increases in suicide among men [101]. Examining these dynamics across socioeconomic groups is also essential, as access to support systems—and the meaning of that support—may vary significantly depending on students’ financial resources and structural disadvantages.

Building on these concerns, future research should investigate why emotional family support significantly moderated psychological distress for men but not for women. Qualitative studies could explore whether men perceive the absence of family support as more impactful due to their socialization toward self-reliance and limited access to alternative support networks. In contrast, women—who often navigate caregiving expectations—may rely on broader social relationships that dilute the relative influence of family-based support. Emotional burnout, the “superwomen” syndrome (belief in the need to manage everything without help), and “support erosion”—where overwhelmed family members become emotionally unavailable, which is consistent with research on the familial stress contagion—may also play a role [88]. Longitudinal studies could assess whether these gendered patterns persist or evolve over time, particularly as coping strategies shift in the post-pandemic context.

Research should also consider how parents’ perceptions of their children’s needs are shaped by gender norms. For example, young men may express emotional needs through externalizing behaviors like aggression, which can lead to parental misunderstandings or the underreporting of internalizing symptoms [57]. Additionally, qualitative research exploring intrafamilial adaptation and coping techniques could yield meaningful insights into how family processes operate under stress. Dyadic approaches, such as examining the caregiver–child relationship, could illuminate the interactive dynamics that shaped family functioning during the pandemic. Gathering perspectives from multiple family members would offer a fuller view of how caregiver stress affected the capacity to provide emotional support [57]. Future research could also examine how economic stress is internalized and expressed across households, particularly in relation to income differences and access to instrumental support. Such work would deepen our understanding of family resilience and inform interventions aimed at strengthening support systems for college students during future crises.

12. Limitations

This study was conducted in a single geographical region during the first COVID-19 lockdowns, capturing an unprecedented moment of disruption. While this timing enhances this study’s relevance, it also limits its ability to assess changes over time as the pandemic progressed. Geographic constraints further affect generalizability, as the economic and cultural variation across regions was not examined. Additionally, the demographic composition of our sample presents limitations for broader application.

Respondents were predominately white, which may not reflect the experiences of students in more racially diverse college environments. Household income was distributed roughly evenly above and below USD 100,000—a cutoff selected to reflect the median income of the local zip code and 1.5 times the regional median. While this captures a range of socioeconomic backgrounds, it may not represent students at institutions where economic hardship is more widespread. Research conducted since our data collection has shown that lower-income and racially minoritized students faced greater financial strain, food and housing insecurity, and unequal access to mental health resources during the pandemic [95,96]. These structural disadvantages may have shaped both perceived family support and distress in ways not fully captured in our study.

A further consideration relates to measurement. Because this study was conducted early in the pandemic, no validated instrument was yet available to assess COVID-19-related quality of life changes. To address this, we developed a measure tailored to the experiences of college students during that period. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was used to examine the structure of the scale, providing initial evidence of construct validity. While this approach was appropriate for the emergent context and aims of this study, future research during crisis may benefit from confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to further assess the measure’s structure across more diverse populations and settings. Moreover, our measure treated all life change items equally, though students may have experienced certain disruptions as more impactful than others. We also assessed students’ subjective perceptions of life changes, rather than objective conditions, limiting our ability to link specific external events to mental health outcomes.

Another consideration is our emphasis on the perceived quality of family support rather than family structure, focusing on how students experienced emotional connection, validation, and care within their households. While this focus aligns with this study’s goals, we did not analyze differences by family structure—such as single-parent, married, divorced, or blended households—which may influence both the availability and impact of support. As such, the absence of structural distinctions may be viewed as a limitation when considering the full context of family support.

Finally, because our data relied on self-reporting, recall bias is a potential limitation—particularly given the stress of the pandemic, which may have influenced how students remembered or interpreted family support. Those experiencing greater distress may have also been less likely to recognize or recall the support they received. Our focus was on understanding how students’ perceptions of life changes during the pandemic interacted with perceived family support to shape psychological distress, rather than on isolating causal impacts of the pandemic itself or preexisting mental health conditions. Finally, while our quantitative approach provided valuable insights, the absence of qualitative data limits our understanding of how family support was experienced or provided. Future research incorporating interviews or mixed methods could offer deeper insights into the mechanisms behind family support’s impact on student well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., J.R., L.M., M.K., N.R. and T.K.; data collection, J.P.; formal analysis J.P. and L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P., J.R. and L.M.; writing—review and editing, J.P., J.R., L.M., M.K., N.R. and T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board (STUDY00013478) on 16 October 2019. Although designed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, data were collected in June 2020 and incorporated questions about participants’ pandemic-related experiences. All procedures adhered to approved ethical guidelines involving human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study, in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of Pennsylvania State University.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author upon request. Although the data are anonymous, they originate from a single institutional source. Any sharing of materials will be subject to ensuring institutional confidentiality and responsible data use.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Walsh, F. Strengthening Family Resilience; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Prime, H.; Wade, M.; Browne, D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluver, L.; Lachman, J.M.; Sherr, L.; Wessels, I.; Krug, E.; Rakotomalala, S.; Blight, S.; Hillis, S.; Bachman, G.; Green, O. Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kola, L.; Kumar, M.; Kohrt, B.A.; Fatodu, T.; Olayemi, B.A.; Adefolarin, A.O. Strengthening public mental health during and after the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2022, 399, 1851–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbs, B.J.; Rostain, A. The Stressed Years of Their Lives: Helping Your Kid Survive and Thrive During Their College Years; St. Martin’s Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dolsen, E.A.; Nishimi, K.; LeWinn, K.Z.; Byers, A.L.; Tripp, P.; Woodward, E.; Khan, A.J.; Marx, B.P.; Borsari, B.; Jiha, A.; et al. Identifying correlates of suicide ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional analysis of 148 sociodemographic and pandemic-specific factors. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 156, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucejo, E.M.; French, J.; Araya, M.P.U.; Zafar, B. The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. J. Public Econ. 2020, 191, 104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmolejo, F.J.; Groccia, J.E. Reimagining and Redesigning Teaching and Learning in the Post-Pandemic World. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2022, 2022, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Bettis, A.H.; Watson, K.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Dunbar, J.P.; Williams, E.; Thigpen, J.C. Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.; Lionetti, F.; Pastore, M.; Fasolo, M. Parents’ stress and children’s psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; MacGeorge, E.L.; Myrick, J.G. Mental health and its predictors during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic experience in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Marinovich, C.; Rajkumar, R.; Besecker, M.; Zhou, S.; Jacob, L.; Koyanagi, A.; Smith, L. COVID-19 dimensions are related to depression and anxiety among US college students: Findings from the Healthy Minds Survey 2020. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 292, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krendl, A.C. Changes in stress predict worse mental health outcomes for college students than does loneliness; evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elharake, J.A.; Akbar, F.; Malik, A.A.; Gilliam, W.; Omer, S.B. Mental health impact of COVID-19 among children and college students: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 54, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.-H.; Yang, H.-L.; Yang, Y.-Q.; Liu, D.; Li, Z.-H.; Zhang, X.-R.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Shen, D.; Chen, P.-L.; Song, W.-Q.; et al. “Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptom, and the demands for psychological knowledge and interventions in college students during COVID-19 epidemic: A large cross-sectional study”: Corrigendum. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketwa, A.; Kang’ethe, S.M. Manifestation of the Socio-Psychological Impact of COVID-19 in Selected Contexts around the Globe. Perspect. Glob. Dev. Technol. 2024, 23, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husky, M.M.; Kovess-Masfety, V.; Gobin-Bourdet, C.; Swendsen, J. Prior depression predicts greater stress during COVID-19 mandatory lockdown among college students in France. Compr. Psychiatry 2021, 107, 152234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, N.B. The Impact of COVID-19 on Student Academic Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Alliant International University, Alhambra, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Leonelli, B.R. Insomnia, Distress Tolerance, and Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ph.D. Thesis, Kent State University, Kent, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ryerson, N.C. Behavioral and psychological correlates of well-being during COVID-19. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 125, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravaca-Sánchez, F.; Muyor-Rodríguez, J.; Juan Sebastián, F.-P. Risk and protective factors associated with suicidal behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis amongst college students in Spain. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2022, 20, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlin, A.R.; Barney, S.T. Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 on College Student Academic and Social Lives. Res. High. Educ. J. 2022, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Yang, X. The influence of resilience on stress reaction of college students during COVID-19: The mediating role of coping style and positive adaptive response. Curr. Psychol. A J. Divers. Perspect. Divers. Psychol. Issues 2023, 43, 12120–12131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tai, Z.; Hu, F. Prevalence and coping of depression and anxiety among college students during COVID-19 lockdowns in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 348, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Zheng, X.; Ye, W.; Fu, W.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Huang, C. Changes of college students’ psychological stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: A two-wave repeated survey. J. Health Psychol. 2024, 30, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, M.L.K. An Interdisciplinary Perspective on Disasters and Stress: The Promise of an Ecological Framework. Sociol. Forum 1998, 13, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arbeloff, T.C.; Kim, M.J.; Knodt, A.R.; Radtke, S.R.; Brigidi, B.D.; Hariri, A.R. Microstructural integrity of a pathway connecting the prefrontal cortex and amygdala moderates the association between cognitive reappraisal and negative emotions. Emotion 2018, 18, 912–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, B.; Galván, A.; Somerville, L.H. Beyond simple models of adolescence to an integrated circuit-based account: A commentary. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmakis, K.A.; Chiodo, L.M.; Kent, N.; Meyer, J.S. Adverse childhood experiences, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, and self-reported stress among traditional and nontraditional college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 68, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Motti-Stefanidi, F. Multisystem resilience for children and youth in disaster: Reflections in the context of COVID-19. Advers. Resil. Sci. 2020, 1, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allem, J.-P.; Unger, J.B. Emerging adulthood themes and hookah use among college students in Southern California. Addict. Behav. 2016, 61, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowker, J.C.; Stotsky, M.T.; Etkin, R.G. How BIS/BAS and psycho-behavioral variables distinguish between social withdrawal subtypes during emerging adulthood. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2017, 119, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulisa, F. Application of bioecological systems theory to higher education: Best evidence review. J. Pedagog. Sociol. Psychol. 2019, 1, 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- MacPhee, J.; Ponte, K. How Parents Can Support Their College Students’ Mental Health; National Alliance on Mental Illness: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kamo, Y.; Henderson, T.L.; Roberto, K.A. Displaced Older Adults’ Reactions to and Coping with the Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. J. Fam. Issues 2011, 32, 1346–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmer, R.P.a.V.G.-R. (Ed.) Introduction: Attending to Ecology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shahinfar, A.; Vishnevsky, T.; Kilmer, R.P.; Gil-Rivas, V. Service Needs of Children and Families Affected by Hurricane Katrina. In Helping Families and Communities Recover from Disaster; Kilmer, R.P., Gil-Rivas, V., Tedeschi, R.G., Calhoun, L.G., Eds.; The American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Son, C.; Hegde, S.; Smith, A.; Wang, X.; Sasangohar, F. Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Liang, S.; Yang, W.; Peng, X.; Cai, C.; Huang, A.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J. Impact of family functioning on mental health problems of college students in China during COVID-19 pandemic and moderating role of coping style: A longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, E. Relapsing Left and Right: Trying to Overcome Addiction in a Pandemic; The New York Times: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kamenetz, A. When Colleges Shut Down, Some Students Have Nowhere to Go; National Public Radio: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.H.; Zhang, E.; Wong, G.T.F.; Hyun, S.; Hahm, H.C. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintre, M.G.; Yaffe, M. First-Year Students’ Adjustment to University Life as a Function of Relationships with Parents. J. Adolesc. Res. 2000, 15, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larose, S.; Boivin, M. Attachment to Parents, Social Support Expectations, and Socioemotional Adjustment during the High School—College Transition. J. Res. Adolesc. 1998, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintre, M.G.; Ames, M.E.; Pancer, S.M.; Pratt, M.W.; Polivy, J.; Birnie-Lefcovitch, S.; Adams, G.R. Parental Divorce and First-Year Students’ Transition to University: The Need to Include Baseline Data and Gender. J. Divorce Remarriage 2011, 52, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.R.; Fish, M.C. Adjustment to College in Nonresidential First-Year Students: The Roles of Stress, Family, and Coping. J. First-Year Exp. Stud. Transit. 2013, 25, 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Levens, S.M.; Elrahal, F.; Sagui, S.J. The role of family support and perceived stress reactivity in predicting depression in college freshman. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 35, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkody, E.; Moussa Rogers, M.; McKinney, C. Positive health benefits of social support: Examining racial differences. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2021, 7, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budescu, M.; Silverman, L. Kinship Support and Academic Efficacy Among College Students: A Cross-Sectional Examination. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 1789–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, T.L.; Hildreth, G. Experiences in the Face of Disasters: Children, Teachers, Older Adults, and Families. J. Fam. Issues 2011, 32, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, M.L.; Self-Brown, S.; Le, B.; Bosson, J.V.; Hernandez, B.C.; Gordon, A.T. Predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms in children following Hurricane Katrina: A prospective analysis of the effect of parental distress and parenting practices. J. Trauma Stress 2010, 23, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osofsky, H.J.; Osofsky, J.D.; Kronenbrg, M.; Brenna, A.; Hansel, T.C. Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Children after Hurricane Katrina: Predicting the Need for Mental Health Services. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2009, 79, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhoit, S.A.; Trentacosta, C.J.; Beeghly, M.; Boeve, J.L.; Lewis, T.L.; Thomason, M.E. Household Chaos and Early Childhood Behavior Problems: The Moderating Role of Mother–Child Reciprocity in Lower-Income Families. Fam. Relat. 2021, 70, 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, M.L.; Rasmussen, H.F.; Fanning, K.A.; Braaten, S.M. Parenting During COVID-19: A Study of Parents’ Experiences Across Gender and Income Levels. Fam. Relat. 2021, 70, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Hong, P. COVID-19 and Mental Health of Young Adult Children in China: Economic Impact, Family Dynamics, and Resilience. Fam. Relat. 2021, 70, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfin, D.R.; Silver, R.C.; Gil-Rivas, V.; Guzmán, J.; Murphy, J.M.; Cova, F.; Rincón, P.P.; Squicciarini, A.M.; George, M.; Guzmán, M.P. Children’s reactions to the 2010 Chilean earthquake: The role of trauma exposure, family context, and school-based mental health programming. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2014, 6, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Rivas, V.; Kilmer, R.P.; Hypes, A.W.; Roof, K.A. The Caregiver-Child Relationship and Children’s Adjustment Following Hurricane Katrina. In Helping Families and Communities Recover from Disaster: Lessons Learned from Hurricane KATRINA and Its Aftermath; Kilmer, R.P., Gil-Rivas, V., Tedeschi, R.G., Calhoun, L.G., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Chapter xiv; pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, A.K.; Dougherty, J.G. Mass trauma: Disasters, terrorism, and war. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2014, 23, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Narayan, A.J. Child development in the context of disaster, war, and terrorism: Pathways of risk and resilience. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 227–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worley, T.R.; Mucci-Ferris, M. Parent–student relational turbulence, support processes, and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2021, 38, 3010–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Z. Evaluation of changes in college students’ experience of family harmony before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 23378–23386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singletary, B.; Schmeer, K.K.; Purtell, K.M.; Sayers, R.C.; Justice, L.M.; Lin, T.-J.; Jiang, H. Understanding family life during the COVID-19 shutdown. Fam. Relat. 2022, 71, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benhayoun, A.; Yamada, A.-M. Family matters: A qualitative study of stressors experienced by korean american college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 73, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.D.; DeLaney, E.N.; Moreno, O.; Santana, A.; Fuentes, L.; Muñoz, G.; Elias, M.d.J.; Johnson, K.F.; Peterson, R.E.; Hood, K.B.; et al. Interactions between COVID-19 family home disruptions and relationships predicting college students’ mental health over time. J. Fam. Psychol. 2023, 37, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ma, Z.; McReynolds, L.S.; Lin, D.; Chen, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Mental Health Among College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China: A 2-Wave Longitudinal Survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.P.; Li, S.; Fan, L.P. Risk Factors of Psychological Disorders After the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Mediating Role of Social Support and Emotional Intelligence. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Su, X.; Si, M.; Xiao, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Gu, X.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; et al. The impacts of coping style and perceived social support on the mental health of undergraduate students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in China: A multicenter survey. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Xiang, M.; Cheung, T.; Xiang, Y.-T. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, E.; Cohen, F.; Wolf, K.; Burghardt, L.; Anders, Y. Changes in parents’ home learning activities with their children during the COVID-19 lockdown–The role of parental stress, parents’ self-efficacy and social support. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 682540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Morales, J.; Garcia, Y. Beyond undocumented: Differences in the mental health of Latinx undocumented college students. Lat. Stud. 2021, 19, 374–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otanga, H.; Tanhan, A.; Musılı, P.M.; Arslan, G.; Buluş, M. Exploring College Students’ Biopsychosocial Spiritual Wellbeing and Problems during COVID-19 through a Contextual and Comprehensive Framework. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpert-Esmond, H.I.; Marquez, E.D.; Camacho, A.A. Family relationships and familism among Mexican Americans on the U.S.–Mexico border during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2023, 29, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Farina, R.E.; Lawrence, S.E.; Walters, T.L.; Clark, A.N.; Hanna-Walker, V.; Lefkowitz, E.S. How social support and parent–child relationship quality relate to LGBTQ+ college students’ well-being during COVID-19. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, Z.B.; Wang, D.C.; Lee, C.; Barnes, H.; Abouezzeddine, T.; Canada, A.; Aten, J. Social support, religious coping, and traumatic stress among Hurricane Katrina survivors of southern Mississippi: A sequential mediational model. Traumatol. Int. J. 2021, 27, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, D.M.; Weems, C.F. Family and peer social support and their links to psychological distress among hurricane-exposed minority youth. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Suarez, G.; Rabionet, S.E.; Zorrilla, C.D.; Perez-Menendez, H.; Rivera-Leon, S. Pregnant Women’s Experiences during Hurricane Maria: Impact, Personal Meaning, and Health Care Needs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, A.; Nakagawa, Y. How Does Reciprocal Exchange of Social Support Alleviate Individuals’ Depression in an Earthquake-Damaged Community? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.S.; Skjerdingstad, N.; Ebrahimi, O.V.; Hoffart, A.; Johnson, S.U. Parenting in a Pandemic: Parental stress, anxiety and depression among parents during the government-initiated physical distancing measures following the first wave of COVID-19. Stress Health 2022, 38, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajwad, M.I.a.S.B. Seen and Unseen Effects of COVID-19 School Disruptions; The Brookings Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, E.H. Families Are Important for College Student Success; The University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Crayne, M.P. The traumatic impact of job loss and job search in the aftermath of COVID-19. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S180–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Serido, J.; Vosylis, R.; Sorgente, A.; Lep, Ž.; Zhang, Y.; Fonseca, G.; Crespo, C.; Relvas, A.P.; Zupančič, M.; et al. Employment disruption and wellbeing among young adults: A cross-national study of perceived impact of the COVID-19 lockdown. J. Happiness Stud. Interdiscip. Forum Subj. Well-Being 2023, 24, 991–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]