Balanced Scorecard: History, Implementation, and Impact

Definition

1. Introduction

2. Historical Development

3. Conceptual Foundation

3.1. Key Concepts

3.2. Stepwise Development of the BSC

4. Conceptual Evolution

5. Implementation and Use

6. Impact and Popularity

7. Criticism and Challenges

8. Future Research Directions

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tawse, A.; Tabesh, P. Thirty years with the balanced scorecard: What we have learned. Bus. Horiz. 2022, 66, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Z. 20 years of studies on the Balanced Scorecard: Trends, accomplishments, gaps and opportunities for future research. Br. Account. Rev. 2014, 46, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindle, T. Guide to Management Ideas and Gurus; The Economist in Assocation with Profile Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The balanced scorecard—Measures that drive performance. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1992, 70, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamel, G.; Prahalad, C.K. Competing for the Future; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, H.T.; Kaplan, R.S. Relevance Lost: The Rise and Fall of Management Accounting; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, T. Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, K.A.; Van der Stede, W.A. Management Control Systems: Performance Measurement, Evaluation and Incentives, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sibbet, D. 75 years of management ideas and practice 1922–1997. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Gargallo, C.; Zaragoza-Sáez, P. A Comprehensive Bibliometric Study of the Balanced Scorecard. Eval. Program Plan. 2023, 97, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S.M.d.S.; Ventura, J.B.; Rua, O.L.; Bernardes, Ó. Contributions of the balanced scorecard as a support instrument in strategic decision-making: A bibliometric study. Int. J. Bibliometr. Bus. Manag. 2023, 2, 210–245. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, V.; Thaker, K. Studying research in balanced scorecard over the years in performance management systems: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Prince, N.; Baker, H.K. Balanced Scorecard: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Issues. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2022, 11, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Lim, W.M.; Sureka, R.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Bamel, U. Balanced scorecard: Trends, developments, and future directions. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 2397–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Kader, M.; Moufty, S.; Laitinen, E.K. Balanced Scorecard Development: A Review of Literature and Directions for Furture Research. In Review of Management Accounting Research; Abdel-Kader, M.G., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2011; p. 214. [Google Scholar]

- Lueg, R.; Carvalho e Silva, A.L. When one size does not fit all: A literature review on the modifications of the balanced scorecard. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2013, 11, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, D.; Bilodeau, B. A History of Bain’s Management Tools & Trends Survey; Bain & Company, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, D.; Bilodeau, B.; Ronan, K. Management Tools & Trends 2023; Bain & Company, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S. Yesterday’s Accounting Undermines Production. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1984, 62, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, P.H. Value Driven Intellectual Capital: How to Convert Intangible Corporate Assets into Market Value; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, T. The Wealth of Knowledge: Intellectual Capital and the Twenty-First Century Organization; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Managing Intellectual Capital; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The Strategy-Focused Organization: How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the New Business Environment; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Execution Premium: Linking Strategy to Operations for Competitive Advantage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Niven, P.R. Balanced Scorecard Diagnostics: Maintaining Maximum Performance; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Niven, P.R. Balanced Scorecard: Step-By-Step for Government and Nonprofit Agencies, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Niven, P.R. Balanced Scorecard Evolution: A Dynamic Approach to Strategy Execution; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, M. Essentials of Balanced Scorecard; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hannabarger, C.; Buchman, F.; Economy, P. Balanced Scorecard Strategy for Dummies; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, K.G.; Holving, P.A. Balansert Målstyring—Strategisk Virksomhetsstyring Satt i System, 2nd ed.; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Olve, N.G.; Sjostrand, A. The Balanced Scorecard; Capstone: Chichester, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Olve, N.G.; Petri, C.G.; Roy, J.; Roy, S. Making Scorecards Actionable—Balancing Strategy and Control; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bukh, P.N.; Fredriksen, J.; Hegaard, M.W. Balanced Scorecard På Dansk: Ti Virksomheders Erfaringer; Børsen Forlag A/S: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bukh, P.N.; Bang, H.K.; Hegaard, M.W. Strategikort: Balanced Scorecard Som Strategiværktøj—Danske Erfaringer; Børsens Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, K.S.; Bukh, P.N. Succes Med Balanced Scorecard; Gyldendal A/S: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S. Mobil USM&R (A): Linking the Balanced Scorecard; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, R.L.; Dávila, A. Citibank: Performance Evaluation; Harvard Business School Case 198-048; Harvard Business Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ax, C.; Bjørnenak, T. Bundling and diffusion of management accounting innovations—The case of the balanced scorecard in Sweden. Manag. Account. Res. 2005, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olve, N.G.; Roy, J.; Wetter, M. Balanced Scorecard i Svensk Praktik; LIBER: Malmö, Sweden, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, B. Key Performance Indicators for Dummies; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lueg, R. Strategy maps: The essential link between the balanced scorecard and action. J. Bus. Strategy 2015, 36, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucianetti, L. The impact of the strategy maps on balanced scorecard performance. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2010, 12, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.J.; Ezzamel, M.; Qu, S.Q. Popularizing a Management Accounting Idea: The Case of the Balanced Scorecard. Contemp. Account. Res. 2017, 34, 991–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speckbacher, G.; Bischof, J.; Pfeiffer, T. A descriptive analysis of the implementation of balanced scorecards in German-speaking countries. Manag. Account. Res. 2003, 14, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.A.; Balakrishnan, R.; Booth, P.; Cole, J.M.; Groot, T.; Malmi, T.; Roberts, H.; Uliana, E.; Wu, A. New directions in management accounting research. J. Manag. Account. Res. 1997, 9, 79–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ittner, C.D.; Larcker, D.F. Coming up short on nonfinancial performance measurement. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Putting the balanced scorecard to work. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 315, 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Alignment: Using the Balanced Scorecard to Create Corporate Synergies; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van Grembergen, W.; Saull, R.; De Haes, S. Linking the IT balanced scorecard to the business objectives at a major Canadian financial group. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 2003, 5, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B.E.; Huselid, M.A.; Ulrich, D. The HR Scorecard: Linking People, Strategy, and Performance; Harvard Business Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fottler, M.D.; Erickson, E.; Rivers, P.A. Bringing human resources to the table: Utilization of an HR balanced scorecard at Mayo Clinic. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Wisner, P.S. Using a balanced scorecard to implement sustainability. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2001, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, F.; Hahn, T.; Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. The sustainability balanced scorecard–linking sustainability management to business strategy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, A.; Schaltegger, S. The sustainability balanced scorecard as a framework for eco efficiency analysis. J. Ind. Ecol. 2005, 9, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehimi, M.; Naro, G. Balanced Scorecards and sustainability Balanced Scorecards for corporate social responsibility strategic alignment: A systematic literature review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 367, 122000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Gómez, A.M.; Pineda-Ganfornina, M.; Ávila-Gutiérrez, M.J.; Agote-Garrido, A.; Lama-Ruiz, J.R. Balanced Scorecard for Circular Economy: A Methodology for Sustainable Organizational Transformation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiraeus, D.; Creelman, J. How to Build an Agile and Adaptive Balanced Scorecard. In Agile Strategy Management in the Digital Age: How Dynamic Balanced Scorecards Transform Decision Making, Speed and Effectiveness; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Fabac, R. Digital Balanced Scorecard System as a Supporting Strategy for Digital Transformation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrie, G.; Cobbold, I. Third-generation balanced scorecard: Evolution of an effective strategic control tool. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2004, 53, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudan, A. Balanced Scorecard typology and organisational impact. KM Online J. Knowl. Manag. 2005, 2, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Soderberg, M.; Kalagnanam, S.; Sheehan, N.T.; Vaidyanathan, G. When is a balanced scorecard a balanced scorecard? Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2011, 60, 688–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M.; Grey, A.; Remmers, H. What do we really mean by “Balanced Scorecard?”. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2014, 63, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, D.Ø.; Stenheim, T. Perceived problems associated with the implementation of the balanced scorecard: Evidence from Scandinavia. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2014, 12, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, D.Ø.; Stenheim, T. Perceived benefits of balanced scorecard implementation: Some preliminary evidence. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2014, 12, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, D.Ø. Interpretation and use of the Balanced Scorecard in Denmark: Evidence from suppliers and users of the concept. Dan. J. Manag. Bus. 2014, 78, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lueg, R.; Vu, L. Success factors in Balanced Scorecard implementations—A literature review. Manag. Rev. 2015, 26, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ax, C.; Greve, J. Adoption of management accounting innovations: Organizational culture compatibility and perceived outcomes. Manag. Account. Res. 2017, 34, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagensveld, J. The Travel and Translation of Balanced Scorecards. Ph.D. Thesis, Radboud University Nijmegen: Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wongkaew, W. Managing Multiple Dimensions of Performance: A Field Study of Balanced Scorecard Translation in the Thai Financial Services Organisation; University of Warwick: Coventry, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Braam, G.; Heusinkveld, S.; Benders, J.; Aubel, A. The Reception Pattern of the Balanced Scorecard: Accounting for Interpretative Viability; Nijmegen School of Management, University of Nijmegen: Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Braam, G.; Nijssen, E. Performance effects of using the Balanced Scorecard: A note on the Dutch experience. Long Range Plan. 2004, 37, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueg, R.; Julner, P. How are Strategy Maps Linked to Strategic and Organizational Change? A Review of the Empirical Literature on the Balanced Scorecard. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2014, 11, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Geuser, F.; Mooraj, S.; Oyon, D. Does the Balanced Scorecard Add Value? Empirical Evidence on Its Effect on Performance. Eur. Account. Rev. 2009, 18, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucianetti, L. Antecedents and consequences of Balanced Scorecard. Econ. Aziend. Online 2013, 4, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.; Albright, T. An investigation of the effect of Balanced Scorecard implementation on financial performance. Manag. Account. Res. 2004, 15, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisel, L.S. Performance Measurement Practices Survey; American Institute of Public Accountants: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Silk, S. Automating the balanced scorecard. Manag. Account. 1998, 79, 38–40, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Balanced scorecard is fast becoming a must have process for corporate change. Manag. Serv. 2001, 45, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kald, M.; Nilsson, F. Performance measurement at Nordic Companies. Eur. Manag. J. 2000, 188, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olve, N.G.; Petri, C.J. Balanced Scorecard i Svenska Teknikföretag. Rapport til Teknikföretagen. Hösten 2004; Teknikföretaget: Stockholm, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Malmi, T. Balanced scorecards in Finnish companies: A research note. Manag. Account. Res. 2001, 12, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.; Sørensen, R. Motives, diffusion and utilisation of the balanced scorecard in Denmark. Int. J. Account. Audit. Perform. Eval. 2004, 1, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, D.; Madsen, D.Ø. Balansert målstyring—Et dynamisk styringsverktøy? Utviklingen i praksis og fremtidig potensial. In Fokus På Fremtidens Foretaksløsninger; Nesheim, T., Stensaker, I., Eds.; Fagbokforlaget: Bergen, Norway, 2017; pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Johanson, D.; Madsen, D.Ø.; Stenheim, T. Balansert målstyring som økonomistyringsverktøy i norske foretak: Utviklingstendenser i perioden 2015–2018. In Aktuelle Tema i Regnskap og Revisjon; Stenheim, T., Baksaas, K.M., Kulset, E.M., Eds.; Cappelen Damm Akademisk: Oslo, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Johanson, B.D.; Drevvatne, B.; Skredderhaugen, M.; Madsen, D.Ø. Økonomistyring og digitale verktøy: En deskriptiv analyse av Balansert Målstyring og Business Intelligence blant norske virksomheter. Magma 2023, 26, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, D.; Bilodeau, B. Bain’s global 2007 management tools and trends survey. Strategy Leadersh. 2007, 35, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, D. Management Tools 2015: An Executive’s Guide; Bain & Company, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, D. Management Tools 2017: An Executive’s Guide; Bain & Company, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Braam, G. Balanced Scorecard’s Interpretative Variability and Organizational Change. Bus. Dyn. 21st Century 2012, 1, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Aidemark, L.G. The Meaning of Balanced Scorecards in the Health Care Organization. Financ. Account. Manag. 2001, 17, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.; Mouritsen, J. Strategies and Organizational Problems: Constructing Corporate Value and Coherences in Balanced Scorecard Processes. In Controlling Strategy: Management, Accounting and Performance Measurement; Chapman, C.S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Modell, S. Bundling management control innovations: A field study of organisational experimenting with total quality management and the balanced scorecard. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2009, 22, 59–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadallah, E.A.; Allam, A. A Critique of the Balanced Scorecard as a Performance Measurement Tool. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D.J.; Ezzamel, M. A Critical Analysis of the Balanced Scorecard: Towards a More Dialogic Approach. In Pioneers of Critical Accounting: A Celebration of the Life of Tony Lowe; Haslam, J., Sikka, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2016; pp. 201–230. [Google Scholar]

- Aryani, Y.A.; Setiawan, D. Balanced Scorecard: Is It Beneficial Enough? A Literature Review. Asian J. Account. Perspect. 2020, 13, 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nørreklit, H. The balance on the balanced scorecard a critical analysis of some of its assumptions. Manag. Account. Res. 2000, 11, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukh, P.N.; Malmi, T. Re-examining the cause-and-effect principle of the balanced scorecard. In Northern Lights in Accounting; Mourtisen, J., Jönsson, S., Eds.; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Voelpel, S.C.; Leibold, M.; Eckhoff, R.A. The tyranny of the Balanced Scorecard in the innovation economy. J. Intellect. Cap. 2006, 7, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonsen, Y. The downside of the Balanced Scorecard: A case study from Norway. Scand. J. Manag. 2014, 30, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, D.Ø.; Slåtten, K. The Balanced Scorecard: Fashion or Virus? Adm. Sci. 2015, 5, 90–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braam, G.; Benders, J.; Heusinkveld, S. The balanced scorecard in the Netherlands: An analysis of its evolution using print-media indicators. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2007, 20, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, D.; Slåtten, K. The Role of the Management Fashion Arena in the Cross-National Diffusion of Management Concepts: The Case of the Balanced Scorecard in the Scandinavian Countries. Adm. Sci. 2013, 3, 110–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S. A sociological analysis of the rise and dissemination of management accounting innovations: Evidence from the balanced scorecard. In Proceedings of the Fourth Asia Pacific Interdisciplinary Research in Accounting Conference, Singapore, 4–6 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Frigo, M.L. The balanced scorecard: 20 years and counting. Strateg. Financ. 2012, 94, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, Z. 20th Anniversary of the balanced scorecard. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørreklit, H. The balanced scorecard: What is the score? A rhetorical analysis of the balanced scorecard. Account. Organ. Soc. 2003, 28, 591–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørreklit, H.; Mitchell, F. The balanced scorecard. In Issues in Management Accounting; Hopper, T., Northcott, D., Scapens, R.W., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nørreklit, H.; Nørreklit, L.; Mitchell, F.; Bjørnenak, T. The rise of the balanced scorecard! Relevance regained? J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2012, 8, 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andon, P.; Baxter, J.; Mahama, H. The Balanced Scorecard: Slogans, Seduction and State of Play. Aust. Account. Rev. 2005, 15, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittner, C.D.; Larcker, D.F. Innovations in performance measurement: Trends and research implications. J. Manag. Account. Res. 1998, 10, 205–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, A.; Malleret, V.; Nørreklit, H. The American balanced scorecard versus the French tableau de bord: The ideological dimension. Manag. Account. Res. 2004, 15, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessire, D.; Baker, C.R. The French Tableau de bord and the American Balanced Scorecard: A critical analysis. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2005, 16, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.; Manzoni, J. The Balanced Scorecard and Tableau de Bord: A Global Perspective on Translating Strategy into Action. 1997. Available online: https://flora.insead.edu/fichiersti_wp/inseadwp1997/97-82.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Johanson, U.; Skoog, M.; Backlund, A.; Almqvist, R. Balancing dilemmas of the balanced scorecard. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2006, 19, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooraj, S.; Oyon, D. The Balanced Scorecard: A necessary good or unnecessary evil? Eur. Manag. J. 1999, 17, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modell, S. The Politics of the Balanced Scorecard. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2012, 8, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, F.R.M.S.; Callado, A.L.C. A bibliometric analysis of the Balanced Scorecard from 2000 to 2016. Custos E @ Gronegócio 2018, 14, 17–36. Available online: http://www.custoseagronegocioonline.com.br/numero2v14/OK%202%20BSC%20english.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Johanson, D.; Lepp, S.; Abbas, A.; Madsen, D.Ø. The viral trajectory of a management idea: A longitudinal case study of the Balanced Scorecard in a Norwegian bank. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2208704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarras, A.; Anagnostopoulos, T.; Salmon, I.; Psaromiligkos, Y.; Vryzidis, L. A Change Management Approach with the Support of the Balanced Scorecard and the Utilization of Artificial Neural Networks. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida Marques, P.C.d.; Oliveira, P. Integrating Artificial Intelligence and the Balanced Scorecard: Strengthening Organisational Resilience in Times of Crisis. 2024. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5050488 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Niven, P.R.; Lamorte, B. Objectives and Key Results: Driving Focus, Alignment, and Engagement with OKRs; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vellore, V. OKRs for All: Making Objectives and Key Results Work for Your Entire Organization; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Michalski, D. Operationalization of ESG-Integrated Strategy Through the Balanced Scorecard in FMCG Companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiling, D. Balanced Scorecard implementation in German non-profit organisations. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2010, 59, 534–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, Å. Balanced scorecard: Theoretical perspectives and public management implications. Manag. Audit. J. 2001, 16, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, T.; Madsen, D.Ø.; Stenheim, T. Diffusion and Evolution of Management Accounting Innovations in the Public Sector–A Comparative Case Study. In Revisiting New Public Management and its Effects: Experiences from a Norwegian Context; Strømmen-Bakhtiar, A., Timoshenko, K., Eds.; Waxmann: Munster, Germany, 2021; pp. 147–176. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.; Baines, C. Performance management in UK universities: Implementing the Balanced Scorecard. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2012, 34, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.; Oliveira, A.; Fijałkowska, J.; Silva, R. Implementation of Balanced Scorecard: Case study of a Portuguese higher education institution. Manag. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2021, 26, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.; Lemoine, J. What a difference a word makes: Understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.; Lemoine, J. What VUCA really means for you. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 92. [Google Scholar]

- De Godoy, M.F.; Ribas Filho, D. Facing the BANI world. Int. J. Nutrology 2021, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pilar Barrera-Ortegon, A.; Medina-Ricaurte, G.F.; Jimenez-Hernandez, P.R. Organizational Elements to Confront Turbulent and Fragile VUCA to BANI Scenarios. In Organizational Management Sustainability in VUCA Contexts; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 20–43. [Google Scholar]

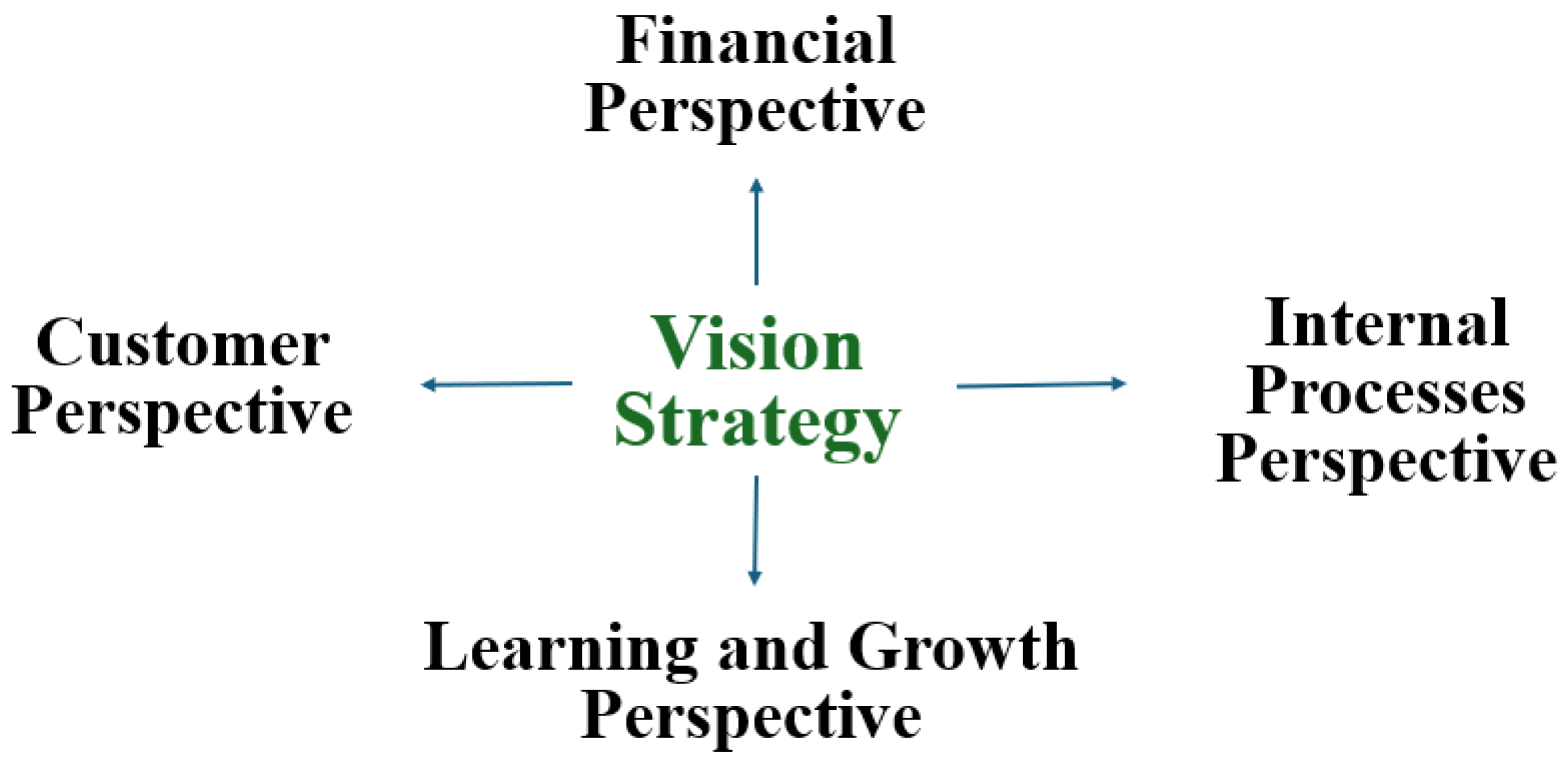

| Perspective | Focus | Examples of KPIs |

|---|---|---|

| Financial | Profitability, cost efficiency, and shareholder value | Return on investment (ROI), revenue growth, and net profit margin |

| Customer | Customer satisfaction, retention, and market share | Customer retention rates, net promoter score (NPS), and market share percentage |

| Internal Processes | Operational efficiency and effectiveness | Cycle time reduction, defect rates, and process innovation metrics |

| Learning and Growth | Employee development, innovation, and knowledge management | Employee training hours, innovation rate, and employee satisfaction index |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madsen, D.Ø. Balanced Scorecard: History, Implementation, and Impact. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5010039

Madsen DØ. Balanced Scorecard: History, Implementation, and Impact. Encyclopedia. 2025; 5(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadsen, Dag Øivind. 2025. "Balanced Scorecard: History, Implementation, and Impact" Encyclopedia 5, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5010039

APA StyleMadsen, D. Ø. (2025). Balanced Scorecard: History, Implementation, and Impact. Encyclopedia, 5(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5010039