Photobiological and Biochemical Characterization of Conchocelis and Blade Phases from Porphyra linearis (Rhodophyta, Bangiales)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Material and Conditions of Cultivation

2.2. Light Microscopy

2.3. Pigment Lipophilic Quantification

2.4. Hydrophilic Bioactive Compounds Extraction

2.5. Total Soluble Phycobiliproteins

2.6. Total Soluble Phenols

2.7. Total Soluble Carbohydrates

2.8. Total Soluble Proteins

2.9. Mycosporine-like Amino Acids (MAAs)

2.10. Antioxidant Activity

2.11. Photosynthesis and Energy Dissipation as In Vivo Chlorophyll a Fluorescence

2.11.1. In Vivo Measurements

2.11.2. Ex Vivo Measurements

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

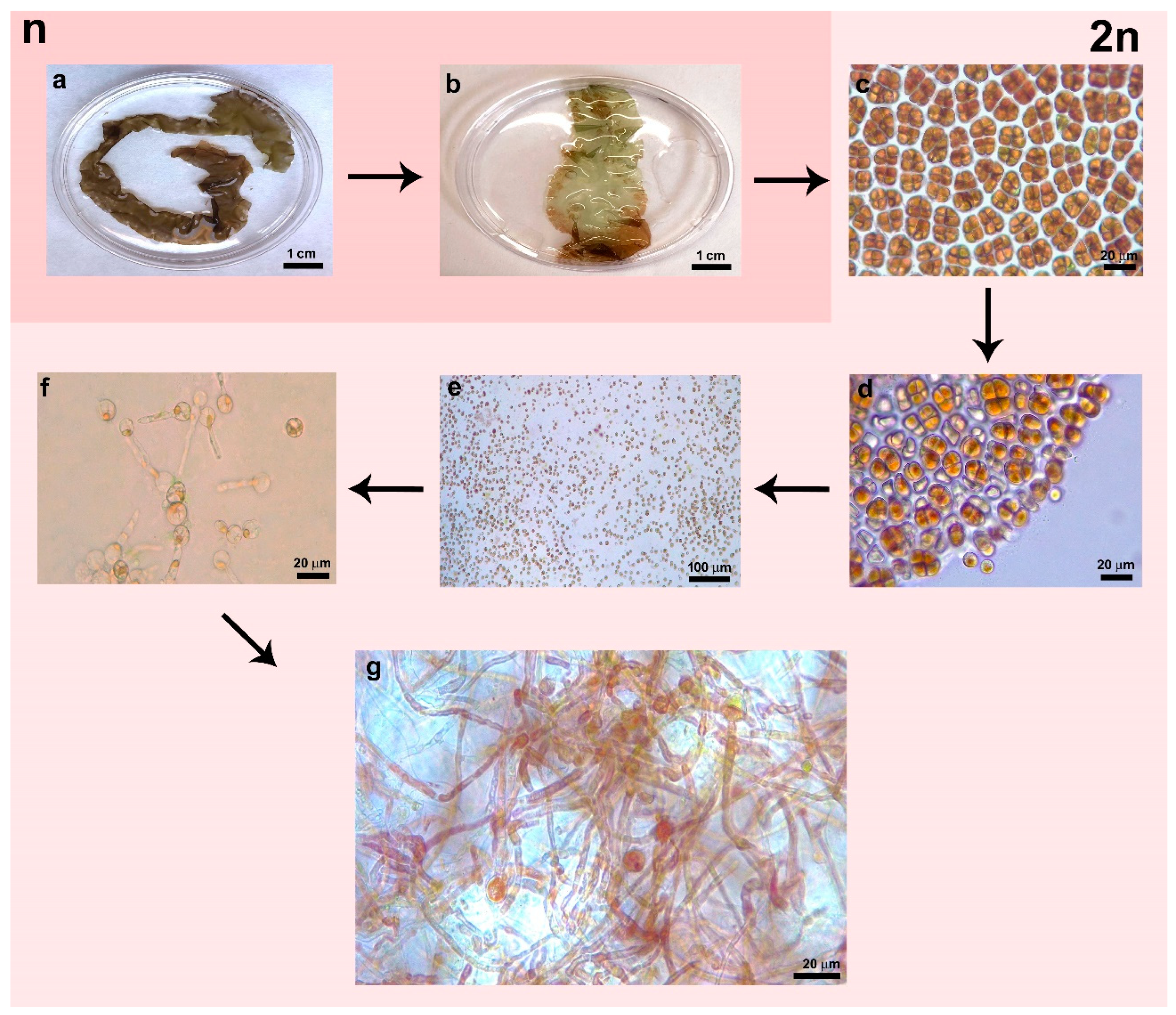

3.1. Microscopic Morphology

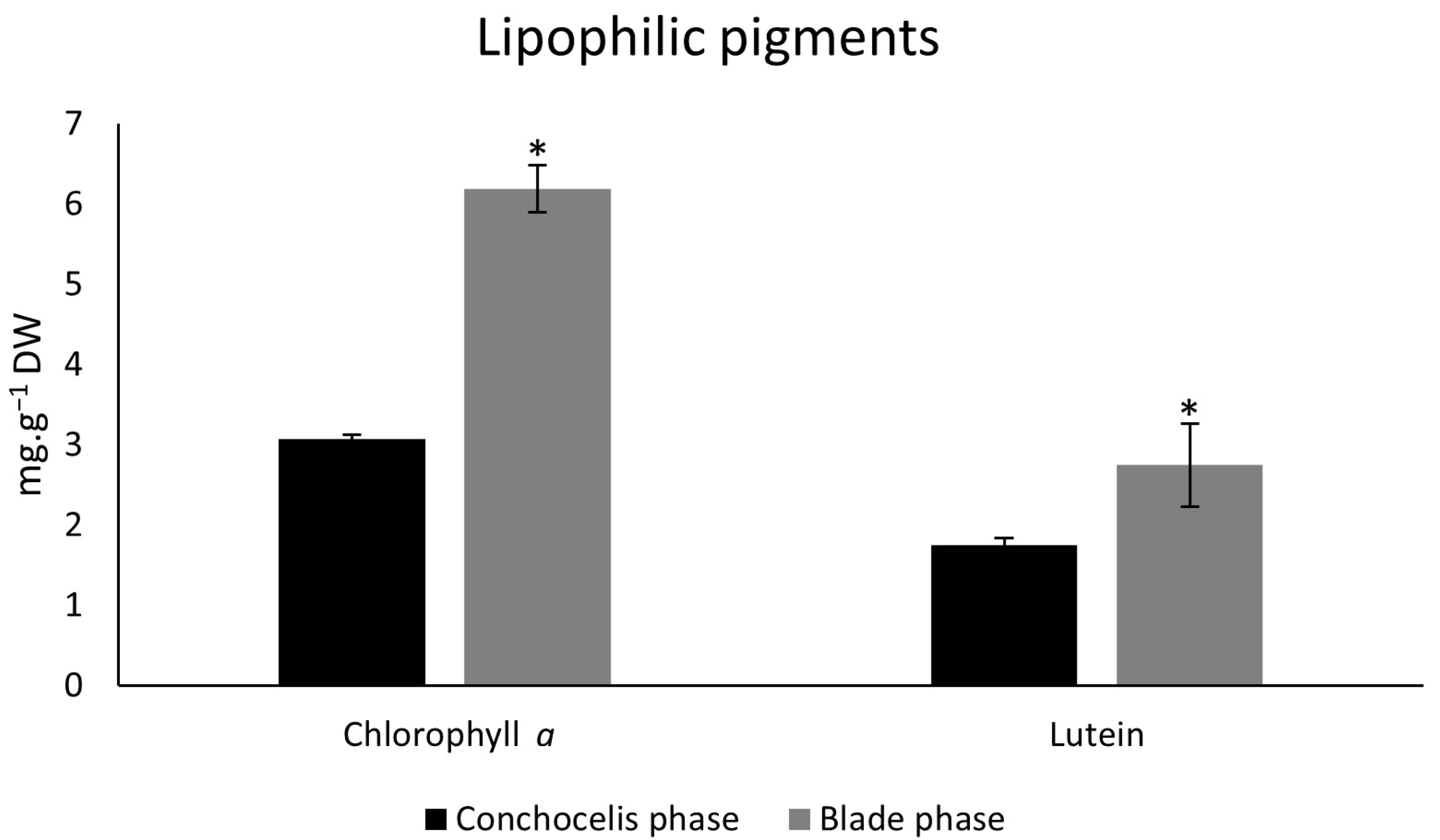

3.2. Concentrations of Lipophilic Photosynthetic Pigments: Chlorophyll a and Carotenoids

3.3. Concentrations of Hydrophilic Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity

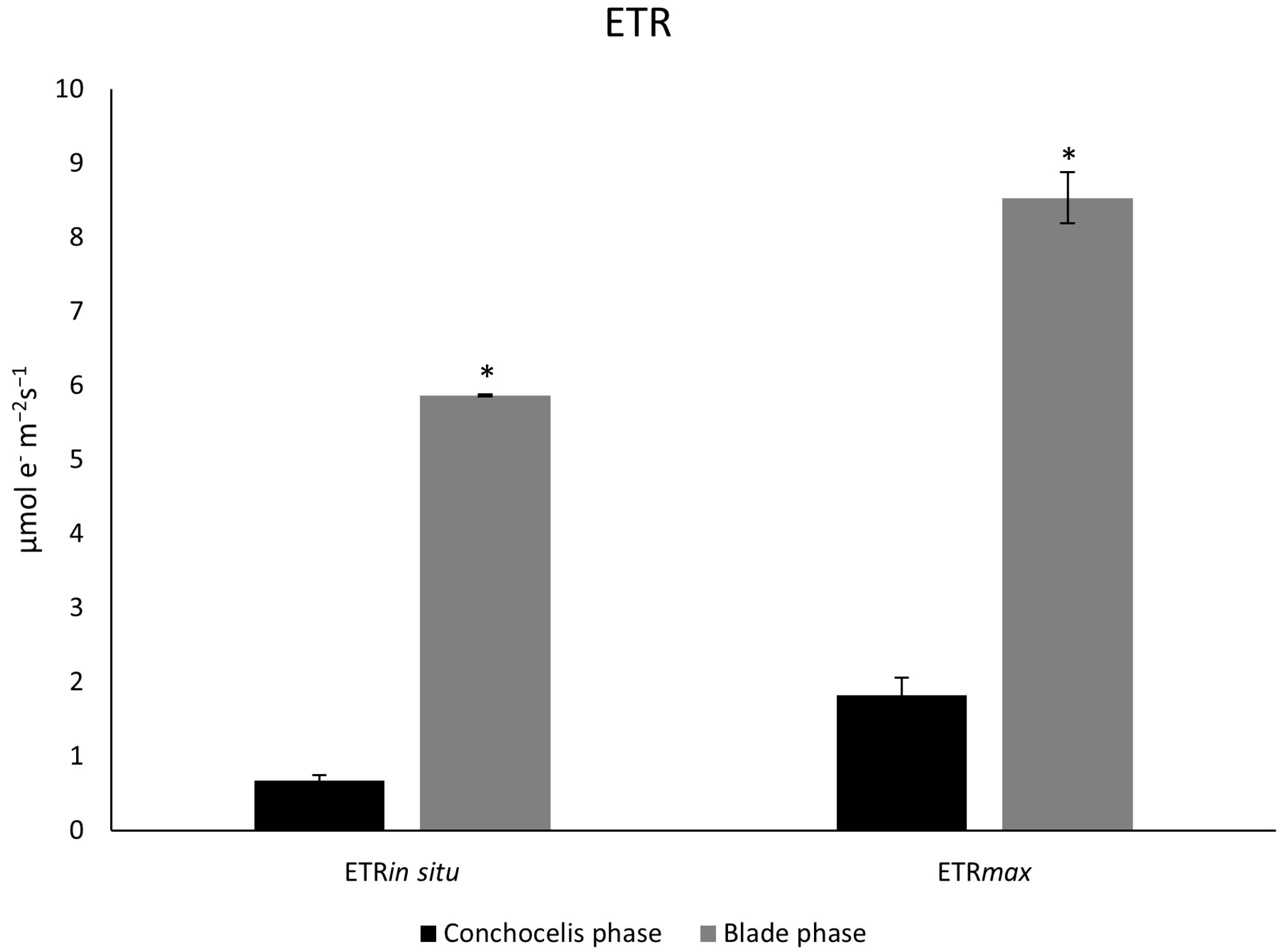

3.4. Photosynthetic Parameters (In Situ and Ex Situ)

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chan, C.X.; Zäuner, S.; Wheeler, G.; Grossman, A.R.; Prochnik, S.E.; Blouin, N.A.; Zhuang, Y.; Benning, C.; Berg, G.M.; Yarish, C.; et al. Analysis of Porphyra membrane transporters demonstrates gene transfer among photosynthetic eukaryotes and numerous sodium-coupled transport systems. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 2001–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Cui, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gong, Q.; Gao, X. Effects of desiccation, water velocity, and nitrogen limitation on the growth and nutrient removal of Neoporphyra haitanensis and Neoporphyra dentata (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). Water 2021, 13, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blouin, N.A.; Brodie, J.A.; Grossman, A.C.; Xu, P.; Brawley, S.H. Porphyra: A marine crop shaped by stress. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.T.; Batista, D.; Filipin, E.P.; Bouzon, Z.L.; Simioni, C. Effects of ultraviolet radiation (UVA+ UVB) on germination of carpospores of the red macroalga Pyropia acanthophora var. brasiliensis (Rhodophyta, Bangiales): Morphological changes. Photochem. Photobiol. 2019, 95, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, K.L.; Mehta, A. Health benefits and pharmacological effects of Porphyra species. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2019, 74, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, R.; Ma, H. Ultrasonic degradation, purification and analysis of structure and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from Porphyra yezoensis Udea. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 2046–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, É.A.; Silva, T.G.D.; Aguiar, J.S.; Barros, L.D.D.; Pinotti, L.M.; Sant’Ana, A.E. Cytotoxic activity of marine algae against cancerous cells. Ver. Bras. Farmacogn. 2013, 23, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, D.G.; Wagemaker, T.A.L.; Alves, V.M.; Benevenuto, C.G.; Gaspar, L.R.; Campos, P.M. In vivo photoprotective effects of cosmetic formulations containing UV filters, vitamins, Ginkgo biloba and red algae extracts. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2015, 153, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, T.; Cotas, J.; Pacheco, D.; Pereira, L. Seaweeds compounds: An ecosustainable source of cosmetic ingredients? Cosmetics 2021, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.; Schneider, G.; Moreira, B.R.; Herrera, C.; Bonomi-Barufi, J.; Figueroa, F.L. Mycosporine-like amino acids from red macroalgae: UV-photoprotectors with potential cosmeceutical applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F.L.; Aguilera, J.; Niell, F.X. Red and blue light regulation of growth and photosynthetic metabolism in Porphyra umbilicalis (L.) Kützing (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). Eur. J. Phycol. 1995, 30, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbee, N.; Huovinen, P.; Figueroa, F.L.; Aguilera, J.; Karsten, U. Availability of ammonium influences photosynthesis and the accumulation of mycosporine-like amino acids in two Porphyra species (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). Mar. Biol. 2005, 146, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Chukhutsina, V.U.; Nawrocki, W.J.; Schansker, G.; Bielczynski, L.W.; Lu, Y.; Karcher, D.; Bock, R.; Croce, R. Photosynthesis without β-carotene. eLife 2020, 9, e58984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tala, F.; Chow, F. Ecophysiological characteristics of Porphyra spp. (Bangiophyceae, Rhodophyta): Seasonal and latitudinal variations in northern-central Chile. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 2159–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.T.; Schmidt, É.C.; Filipin, E.P.; Pilatti, F.K.; Ramlov, F.; Maraschin, M.; Bouzon, Z.L.; Simioni, C. Effects of ultraviolet radiation on the morphophysiology of the macroalga Pyropia acanthophora var. brasiliensis (Rhodophyta, Bangiales) cultivated at high concentrations of nitrate. Acta Physiol. Plant 2020, 42, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, G.; Figueroa, F.L.; Vega, J.; Chaves, P.; Álvarez-Gómez, F.; Korbee, N.; Bonomi-Barufi, J. Photoprotection properties of marine photosynthetic organisms grown in high ultraviolet exposure areas: Cosmeceutical applications. Algal Res. 2020, 49, 101956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, E.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; García, V.; Pastén, A.; Rodríguez, K.; López, J.; Scala, K.D. Evaluation of physicochemical composition and bioactivity of a red seaweed (Pyropia orbicularis) as affected by different drying technologies. Dry. Technol. 2020, 38, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Hartmann, A.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Nunes, F.M.; Souto, E.B.; Santos, D.L.; Abreu, H.; Pereira, R.; Pacheco, M.; Galvão, I.; et al. Red seaweeds strengthening the nexus between nutrition and health: Phytochemical characterization and bioactive properties of Grateloupia turuturu and Porphyra umbilicalis extracts. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 3365–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Choi, S.J.; Lee, S. Effects of temperature and light on photosynthesis and growth of red alga Pyropia dentata (Bangiales, Rhodophyta) in a conchocelis phase. Aquaculture 2019, 505, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Xu, T.; Bao, M.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, T.; Li, Z.; Gao, G.; Li, X.; Xu, J. Response of the red algae Pyropia yezoensis grown at different light intensities to CO2-induced seawater acidification at different life cycle stages. Algal Res. 2020, 49, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, F.B.; Machado, M.; Cermeño, M.; Kleekayai, T.; Machado, S.; Rego, A.M.; Abreu, M.H.; Alves, R.C.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Fitz, G.R.J. Enzyme-assisted release of antioxidant peptides from Porphyra dioica conchocelis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.N.; Mohammad, F. Eutrophication: Challenges and solutions. In Eutroph: Causes, Consequences and Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goecke, F.; Imhoff, J.F. Microbial biodiversity associated with marine macroalgae and seagrasses. In Marine Macrophytes as Foundation Species, 1st ed.; Ólafsson, E., Ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Blouin, N.; Xiugeng, F.; Peng, J.; Yarish, C.; Brawley, S.H. Seeding nets with neutral spores of the red alga Porphyra umbilicalis (L.) Kützing for use in integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA). Aquaculture 2007, 270, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Kraemer, G.P.; Neefus, C.D.; Chung, I.K.; Yarish, C. Effects of temperature and ammonium on growth, pigment production and nitrogen uptake by four species of Porphyra (Bangiales, Rhodophyta) native to the New England coast. J. Appl. Phycol. 2007, 19, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, S.; Green, L.; Yarish, C.; Kim, J.; Neefus, C. New England Seaweed Culture Handbook: Nursery Systems, 1st ed.; Connecticut Sea Grant: Groton, CT, USA, 2014; pp. 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gheysen, L.; Demets, R.; Devaere, J.; Bernaerts, T.; Goos, P.; Van Loey, A.; Foubert, I. Impact of microalgal species on the oxidative stability of n-3 LC-PUFA enriched tomato puree. Algal Res. 2019, 40, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath-Wiley, P.; Neefus, C.D. An improved method for estimating R-phycoerythrin and R-phycocyanin contents from crude aqueous extracts of Porphyra (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). J. Appl. Phycol. 2007, 19, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folin, O.; Ciocalteu, V. On tyrosine and tryptophane determinations in proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1927, 73, 627–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbreit, W.W.; Burris, R.H. Method for glucose determination and other sugars. In Manome-Tric Techniques, 1st ed.; Burgess Publishing Co.: Clayton, NC, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, N.K.; Abdala-Díaz, R.T.; Figueroa, F.L.; Helbling, E.W. Ammonium and UV radiation stimulate the accumulation of mycosporine-like amino acids in Porphyra columbina (Rhodophyta) from Patagonia, Argentina. J. Phycol. 2004, 40, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves-Peña, P.; De La Coba, F.; Figueroa, F.L.; Korbee, N. Quantitative and qualitative HPLC analysis of mycosporine-like amino acids extracted in distilled water for cosmetical uses in four Rhodophyta. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.; Bárcenas-Pérez, D.; Fuentes-Ríos, D.; López-Romero, J.M.; Hrouzek, P.; Figueroa, F.L.; Cheel, J. Isolation of mycosporine-like amino acids from red macroalgae and a marine lichen by high-performance countercurrent chromatography: A strategy to obtain biological UV-filters. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, U.; Sawall, T.; Hanelt, D.; Bischof, K.; Figueroa, F.L.; Flores-Moya, A.; Wiencke, C. An inventory of UV-absorbing mycosporine-like amino acids in macroalgae from polar to warm-temperate regions. Bot. Mar. 1998, 41, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Barre, S.; Roullier, C.; Boustie, J. Mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) in biological photosystems. In Outstanding Marine Molecules; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KgaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, U.; Endo, T.; Mi, H.; Asada, K. Quenching analysis of chlorophyll fluorescence by the saturation pulse method: Particular aspects relating to the study of eukaryotic algae and cyanobacteria. Plant Cell Physiol. 1995, 36, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.; Moreira, B.R.; Avilés, A.; Bonomi-Barufi, J.; Figueroa, F.L. Short-term effects of light quality, nutrient concentrations and emersion on the photosynthesis and accumulation of bioactive compounds in Pyropia leucosticta (Rhodophyta). Algal Res. 2024, 81, 103555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F.L.; Escassi, L.; Pérez-Rodríguez, E.; Korbee, N.; Giles, A.D.; Johnsen, G. Effects of short-term irradiation on photoinhibition and accumulation of mycosporinelike amino acids in sun and shade species of the red algal genus Porphyra. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2003, 69, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F.L.; Domínguez-González, B.; Korbee, N. Vulnerability and acclimation to increased UVB radiation in three intertidal macroalgae of different morpho-functional groups. Mar. Environm. Res. 2014, 97, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilers, P.H.C.; Peeters, J.C.H. A model for the relationship between light intensity and the rate of photosynthesis in phytoplankton. Ecol. Model. 1988, 42, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, A.; Singh, N.K.; Dhoke, R.; Madamwar, D. Influence of light on phycobiliprotein production in three marine cyanobacterial cultures. Acta Physiol. Plant 2013, 35, 1817–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gu, T.; Khan, I.; Zada, A.; Jia, T. Research progress in the interconversion, turnover and degradation of chlorophyll. Cells 2021, 10, 3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Gao, K. Effects of UV radiation on the photosynthesis of conchocelis of Porphyra haitanensis (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). Phycologia 2008, 47, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.T.; Korbee, N.; Vega, J.; Figueroa, F.L. Advancing Porphyra linearis (Rhodophyta, Bangiales) culture: Low cost artificial seawater, nitrate supply, photosynthetic activity and energy dissipation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 3509–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Stekoll, M. Responses of chlorophyll a content for conchocelis phase of Alaskan Porphyra (Bangiales, Rhodophyta) species to environmental factors. Adv. Biosci. Bioeng. 2013, 1, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aple, K.; Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species, metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottuparambil, S.; Shin, W.; Brown, M.T.; Han, T. UV-B affects photosynthesis, ROS production and motility of the freshwater flagellate, Euglena agilis Carter. Aquat. Toxicol. 2012, 122, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Osto, L.; Lico, C.; Alric, J.; Giuliano, G.; Havaux, M.; Bassi, R. Lutein is needed for efficient chlorophyll triplet quenching in the major LHCII antenna complex of higher plants and effective photoprotection in vivo under strong light. BMC Plant Biol. 2006, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovchenko, A.E.; Khozin-Goldberg, I.; Didi-Cohen, S.; Cohen, Z.; Merzlyak, M.N. Effects of light and nitrogen starvation onthe content and composition of carotenoids of the green microalga Parietochloris incisa. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 55, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero, I.; Mogedas, B.; Ruiz-Domínguez, M.C.; Vega, J.M.; Vílchez, C. Light-mediated lutein enrichment of an acid environment microalga. Algal Res. 2014, 6, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, S.; Rajasree, S.R.; Suman, T.Y.; Aranganathan, L.; Thriuganasambandam, R.; Narendrakumar, G. Induction of β, ε-carotene-3, 3′-diol (lutein) production in green algae Chlorella salina with airlift photobioreactor: Interaction of different aeration and light-related strategies. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2021, 11, 2003–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, J.; Takatani, N.; Kobayashi, N.; Mikami, K.; Miyashita, K.; Yamano, Y.; Wada, A.; Maoka, T.; Hosokawa, M. Carotenoid profiling of a red seaweed Pyropia yezoensis: Insights into biosynthetic pathways in the order Bangiales. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talarico, L.; Maranzana, G. Light and adaptive responses in red macroalgae: An overview. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2000, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratelli, C.; Burck, M.; Amarante, M.C.A.; Braga, A.R.C. Antioxidant potential of nature’s “something blue”: Something new in the marriage of biological activity and extraction methods applied to C-phycocyanin. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 107, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, G.A.; El-Sheekh, M.M.; Samy, R.M.; Gheda, S.F. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antiviral activities of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles by phycobiliprotein crude extract of the cyanobacteria Spirulina platensis and Nostoc linckia. Bionanoscience 2021, 11, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarico, L. Phycobiliproteins and phycobilisomes in red algae: Adaptive responses to light. Sci. Mar. 1996, 60, 205–222. [Google Scholar]

- Tsekos, I.; Niell, F.X.; Aguilera, J.; López-Figueroa, F.; Delivopoulos, S.G. Ultrastructure of the vegetative gametophytic cells of Porphyra leucosticta (Rhodophyta) grown in red, blue and green light. Phycol. Res. 2002, 50, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Lu, F.; Bi, Y.; Hu, Z. Effects of light intensity and quality on phycobiliprotein accumulation in the cyanobacterium Nostoc sphaeroides Kützing. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 37, 1663–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shick, J.M.; Dunlap, W.C. Mycosporine-like amino acids and related gadusols: Biosynthesis, accumulation, and UV-protective functions in aquatic organisms. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 2002, 64, 223–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.; Kuniyil, A.M.; Sreenikethanam, A.; Gugulothu, P.; Jeyakumar, R.B.; Bajhaiya, A.K. Microalgae as a source of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs); advances and future prospects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huovinen, P.; Gomez, I.; Figueroa, F.L.; Ulloa, N.; Morales, V.; Lovengreen, C. Ultraviolet-absorbing mycosporine-like amino acids in red macroalgae from Chile. Bot. Mar. 2004, 47, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.T.; Korbee, N.; Vega, J.; Figueroa, F.L. The role of nitrate supply in bioactive compound synthesis and antioxidant activity in the cultivation of Porphyra linearis (Rhodophyta, Bangiales) for future cosmeceutical and bioremediation applications. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsler, C.D.; Fairhead, V.A. Defensive and sensory chemical ecology of brown algae. Adv. Bot. Res. 2006, 43, 1–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ki, J.S. Molecular identification, differential expression and protective roles of iron/manganese superoxide dismutases in the green algae Closterium ehrenbergii against metal stress. Eur. J. Protistol. 2020, 74, 125689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Segovia, I.; Lerma-García, M.J.; Fuentes, A.; Barat, J.M. Characterization of Spanish powdered seaweeds: Composition, antioxidant capacity and technological properties. Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frei, E.; Preston, R.D. Non-cellulosic structural polysaccharides in algal cell walls-II. Association of xylan and mannan in Porphyra umbilicalis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1964, 160, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, B.Z.; Siegel, S.M. The chemical composition of algal cell walls. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 1973, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldan, B.; Andolfo, P.; Navazio, L.; Tolomio, C.; Mariani, P. Cellulose in algal cell wall, an “in situ” localization. Eur. J. Histochem. 2001, 45, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmingson, J.Á.; Nelson, W.A. Cell wall polysaccharides are informative in Porphyra species taxonomy. J. Appl. Phycol. 2002, 14, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, X. Porphyra species: A mini-review of its pharmacological and nutritional properties. J. Med. Food 2016, 19, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, D.T.; Ouriques, L.C.; Bouzon, Z.L.; Simioni, C. Effects of high nitrate concentrations on the germination of carpospores of the red seaweed Pyropia acanthophora var. brasiliensis (Rhodophyta, Bangiales). Hydrobiologia 2020, 847, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F.L.; Bonomi-Barufi, J.; Celis-Plá, P.S.; Nitschke, U.; Arenas, F.; Connan, S.; Abreu, M.H.; Malta, E.J.; Conde-Álvarez, R.; Chow, F.; et al. Short-term effects of increased CO2, nitrate and temperature on photosynthetic activity in Ulva rigida (Chlorophyta) estimated by different pulse amplitude modulated fluorometers and oxygen evolution. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, F.L.; Celis-Plá, P.S.; Martínez, B.; Korbee, N.; Trilla, A.; Arenas, F. Yield losses and electron transport rate as indicators of thermal stress in Fucus serratus (Ochrophyta). Algal Res. 2019, 41, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F.L.; Salles, S.; Aguilera, J.; Jiménez, C.; Mercado, J.; Viñegla, B.; Flores-Moya, A.; Altamirano, M. Effects of solar radiation on photoinhibition and pigmentation in the red alga Porphyra leucosticta. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1997, 151, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häder, D.P.; Gröniger, A.; Hallier, C.; Lebert, M.; Figueroa, F.L.; Jiménez, C. Photoinhibition by visible and ultraviolet radiation in the red macroalga Porphyra umbilicalis. Plant Ecol. 2000, 145, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F.L.; Gómez, I. Photoacclimation to solar UV radiation in red macroalgae. J. Appl. Phycol. 2001, 13, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hydrophilic Compounds | Conchocelis Phase | Blade Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Phycoerythrin (PE) | 2.00 ± 0.32 | 1.96 ± 0.33 |

| Phycocyanin (PC) | 0.65 ± 0.09 | 0.89 ± 0.17 |

| PE:PC | 3.08 ± 0.10 * | 2.20 ± 0.36 |

| Soluble Total Phenols | 1.34 ± 0.13 | 15.93 ± 1.48 * |

| Soluble Proteins | 0.84 ± 0.11 | 1.39 ± 0.16 * |

| Soluble Total Carbohydrates | 76.16 ± 3.62 * | 49.25 ± 2.63 |

| ABTS test | 4.45 ± 0.72 | 23.37 ± 1.68 * |

| MAAs (mg·g−1 DW) | Conchocelis Phase | Blade Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Palythine | - | 0.01 ± 0.0001 |

| Shinorine | 0.02 ± 0.001 | 1.20 ± 0.31 * |

| Porphyra-334 | - | 19.04 ± 4.48 |

| Total MAAs | 0.02 | 20.25 |

| Photosynthetic Parameters | Conchocelis Phase | Blade Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Fv/Fm | 0.490 ± 0.02 | 0.656 ± 0.03 * |

| αETR | 0.04 ± 0.002 | 0.06 ± 0.004 |

| EkETR | 43.16 ± 2.95 | 153.34 ± 12.13 * |

| EoptETR | 193.72 ± 18.78 | 542.34 ± 8.06 * |

| EoptETR—EkETR | 144.09 ± 10.99 | 388.87 ± 11.71 * |

| NPQmax | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 1.43 ± 0.29 * |

| EkNPQ | 634.23 ± 24.76 * | 336.36 ± 21.04 |

| EkNPQ—EkETR | 591.07 ± 32.12 * | 182.90 ± 20.77 |

| Photosynthetic Parameters | Conchocelis Phase | Blade Phase |

|---|---|---|

| ETR12C,124B | 0.46 ± 0.11 | 4.92 ± 0.22 * |

| EDR12C,124B | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 8.09 ± 0.21 * |

| ETR12C,124B:EDR12C, 124B | 0.46 | 0.61 |

| ETR110C,625B | 1.68 ± 0.25 | 8.48 ± 0.33 * |

| EDR110C,625B | 11.61 ± 0.40 | 59.47 ± 1.13 * |

| ETR110C,625B:EDR110C, 625B | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| ETR873C,1492B | 1.08 ± 0.20 | 6.49 ± 0.17 * |

| EDR873C,1492B | 113.27 ± 11.15 | 158.71 ± 10.11 * |

| ETR873C,1492B:EDR873C,1492B | 0.01 | 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira, D.T.; Figueroa, F.L. Photobiological and Biochemical Characterization of Conchocelis and Blade Phases from Porphyra linearis (Rhodophyta, Bangiales). Phycology 2025, 5, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5010009

Pereira DT, Figueroa FL. Photobiological and Biochemical Characterization of Conchocelis and Blade Phases from Porphyra linearis (Rhodophyta, Bangiales). Phycology. 2025; 5(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5010009

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira, Débora Tomazi, and Félix L. Figueroa. 2025. "Photobiological and Biochemical Characterization of Conchocelis and Blade Phases from Porphyra linearis (Rhodophyta, Bangiales)" Phycology 5, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5010009

APA StylePereira, D. T., & Figueroa, F. L. (2025). Photobiological and Biochemical Characterization of Conchocelis and Blade Phases from Porphyra linearis (Rhodophyta, Bangiales). Phycology, 5(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5010009