Abstract

Background: Vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (vEDS) is a rare connective tissue disorder characterized by collagen type III deficiency, predisposing to spontaneous arterial, uterine, and intestinal ruptures. While intestinal complications are recognized in vEDS, intestinal failure (IF) secondary to these complications is a rare and potentially life-threatening occurrence. This study aimed to describe the clinical presentation, surgical management, and outcomes of pediatric patients with IF secondary to vEDS and to provide a comprehensive review of the limited existing literature on this challenging clinical scenario. Methods: This study comprises a case series of pediatric patients with IF due to vEDS complications and a comprehensive literature review. Clinical data were collected from medical records, including age at diagnosis, surgical history, complications, nutritional status, and long-term outcomes. A literature review was performed to identify studies reporting gastrointestinal complications, surgical outcomes in pediatric vEDS patients, and cases of intestinal failure. Results: Two pediatric patients with vEDS and IF were included. Both patients experienced intestinal perforations and surgical complications and required long-term parenteral nutrition (PN). One patient required PN for 18 months before achieving enteral autonomy, while the other remains dependent. The literature review included four articles and revealed a high risk of complications, including anastomotic leaks, fistulae, and recurrent perforations, in patients with vEDS undergoing intestinal surgery. Delayed diagnosis of vEDS was common. Conclusions: Intestinal complications in pediatric patients with vEDS can lead to severe short bowel syndrome and long-term PN dependence. Early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach are crucial for optimizing patient care and minimizing complications.

1. Introduction

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (EDS) encompasses a diverse group of inherited connective tissue disorders, each characterized by distinct genetic abnormalities affecting the synthesis and structure of collagen, a fundamental protein for the body’s connective tissues [1,2,3,4]. These disorders affect various types of collagen or the proteins that process them, leading to a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. Among the diverse subtypes of EDS, vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (vEDS) (phenotype MIM number 130050), historically known as type IV EDS, distinguishes itself as a particularly rare and potentially life-threatening condition [3]. Its rarity is underscored by an estimated prevalence ranging from 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 150,000 individuals, accounting for approximately 4% of all EDS cases [1,3,5,6]. This subtype’s severity stems from its specific genetic origin: mutations within the COL3A1 gene (Gene/Locus MIM number 120180). This gene provides the blueprint for type III procollagen, a crucial building block of type III collagen, which is particularly abundant and vital in the structural integrity of blood vessel walls, the supporting framework of hollow organs (such as the intestines and uterus), and other critical connective tissues [5,6,7,8,9]. The consequences of COL3A1 mutations are profound. Individuals with vEDS experience impaired production of normal type III procollagen, leading to the production of abnormal or insufficient amounts of this critical protein. This deficiency in properly formed type III collagen compromises the structural integrity and resilience of connective tissues throughout the body, resulting in the hallmark characteristic of significant tissue fragility. This fragility manifests most severely in the increased vulnerability of blood vessels to aneurysm formation, dissection, and rupture, as well as the increased risk of organ rupture, including the intestines, uterus, and spleen [5,6,7,8,9]. This systemic weakness can also affect other connective tissues, contributing to joint hypermobility, skin translucency, and easy bruising, although these features are often less prominent than the vascular complications [5,6,7,8,9]; Table 1.

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria for vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Adapted from the 2017 International Classification of Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes [10].

The clinical presentation of vEDS is multifaceted. Cutaneous manifestations often include thin, translucent skin, a propensity for easy bruising, prominent superficial veins, and challenges with wound healing [1,7]. The most significant concern in vEDS lies in the potential for life-threatening vascular and gastrointestinal complications, such as arterial and venous aneurysms, arterial dissections, and spontaneous ruptures of vital organs, such as the colon and uterus [1,7]. Other clinical features may include joint hypermobility, musculoskeletal pain, delayed puberty, and a range of gastrointestinal complications [1,7].

Genetic counseling is crucial for families affected by vEDS because vEDS is an autosomal dominant condition. Genetic counseling provides families with information about the inheritance pattern, the risks of recurrence, and the options for genetic testing. It also allows families to discuss the implications of a vEDS diagnosis, including the potential for serious complications and the importance of ongoing medical management. Genetic counselors can provide emotional support and help families make informed decisions about family planning.

Intestinal complications represent a significant clinical challenge for individuals with vEDS. Spontaneous gastrointestinal perforation, primarily involving the colon, has been identified as a major digestive complication in this population [2]. Importantly, these intestinal manifestations often serve as the initial presentation of this syndrome, typically occurring in adulthood [2,5]. Consequently, in pediatric patients presenting initially with gastrointestinal manifestations of vEDS but lacking a prior diagnosis, the level of clinical suspicion may be relatively low, potentially delaying appropriate diagnosis and increasing the risk of further complications.

Surgical procedures often lead to severe complications such as anastomotic leaks, fistulae, and peritonitis. These complications can rarely result in short bowel syndrome and the subsequent need for long-term parenteral nutrition (PN). Isolated cases of intestinal failure have been documented in the medical literature; their occurrence remains relatively infrequent, particularly within the pediatric population [2,5,7,11].

Intestinal failure in pediatric vEDS is a rarely reported complication, highlighting the need for further research and clinical experience sharing. This article details our institution’s management of two such cases through our specialized multidisciplinary intestinal rehabilitation program and presents a literature review of the few published reports.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Retrospective Analysis

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted at the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires in Argentina, examining pediatric patients diagnosed with vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (vEDS) who developed intestinal failure (IF) between January 2000 and December 2022. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, ensuring adherence to ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects. All data were anonymized and handled with strict confidentiality to protect patient privacy.

2.2. Patient Selection

The study population consisted of all pediatric patients (defined as individuals aged 18 years or younger at the time of IF diagnosis) diagnosed with vEDS and developing IF secondary to gastrointestinal complications. Patients were included if they met both of the following criteria:

- Confirmed Diagnosis of vEDS. This was established through either of the following:

- Clinical Diagnosis: Based on established diagnostic criteria for vEDS, including clinical features such as thin, translucent skin, easy bruising, joint hypermobility, and a history of vascular or organ rupture, as assessed by a qualified medical geneticist or other experienced clinician.

- Genetic Confirmation: Identification of a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in the COL3A1 gene through genetic testing using standard techniques such as Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing.

- Development of Intestinal Failure: IF was defined according to the European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN) criteria as the condition in which the digestive tract is unable to absorb sufficient nutrients and/or fluids to meet the body’s needs, requiring PN to maintain health and growth.

Patients were excluded if they displayed any of the following criteria:

- They did not meet the diagnostic criteria for vEDS.

- They developed IF due to causes other than gastrointestinal complications of vEDS.

- They had incomplete medical records with insufficient data for analysis.

2.3. Data Collection

A comprehensive data collection process was implemented to gather detailed information on the included patients. Data were retrospectively extracted from the electronic medical records of Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires. A standardized data extraction form was used to ensure consistency and completeness of data collection. The following variables were collected: demographic information (age at vEDS diagnosis, age at IF diagnosis, sex, ethnicity), clinical presentation (initial presenting symptoms of vEDS, including any gastrointestinal manifestations, other vEDS-related complications), surgical history, and long-term outcomes, including clinical evolution (surgical and medical complications and the possibility of intestinal transit reconstruction), nutritional status (intestinal sufficiency or parenteral nutrition dependency), time of parenteral nutrition usage.

2.4. Literature Review

A review of the literature was conducted using the PubMed database. The search focused on identifying all studies (including case series and case reports) related to vEDS and IF. The search terms used were “Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome” [MeSH Terms] AND (“Intestinal Failure” [MeSH Terms] OR “Short Bowel Syndrome” [MeSH Terms] OR “Parenteral Nutrition” [MeSH Terms]). Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts for relevance based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data from the literature review were synthesized narratively. A descriptive analysis was performed, including frequency of reported complications, categorization of surgical approaches, and a thematic analysis of reported outcomes. Due to the limitations of the data, a meta-analysis was not conducted.

3. Results

Two pediatric patients with vEDS and intestinal failure were included in the study. Both patients were male and of Latin/Caucasian ethnicity. The initial clinical presentation was at 4 and 13 years of age. Initially, both patients were treated at other hospitals for acute abdominal conditions but were subsequently referred to our institution for specialized management of surgical complications and intestinal failure. In both patients, there was no known family history of vEDS or related connective tissue disorders.

The first patient, a 13-year-old male, presented with suspected acute appendicitis and underwent an appendectomy at another hospital. Postoperatively, he developed spontaneous jejunal perforation, leading to emergency laparotomy and the creation of a jejunostomy. Three months later, an attempt was made to close the stoma. However, multiple postoperative complications ensued, including anastomotic leakage, spontaneous perforations of the ileum and duodenum, and the development of multiple enterocutaneous fistulae. These complications necessitated extensive intestinal resections, resulting in a jejunostomy performed at 80 cm distal to the duodeno-jejunal junction and dependence on long-term PN. No bleeding complications were observed. Although genetic testing was precluded by resource constraints, the patient’s distinctive facial features and extensive medical history strongly supported a clinical diagnosis of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.

This patient fulfilled one major criterion (spontaneous intestinal perforation) and five minor criteria for vEDS, including thin and translucent skin, easy bruising, characteristic facial features, hypermobility of small joints, and tendon/muscle rupture (evident during postoperative recovery).

Eight years after diagnosis, a second episode of spontaneous duodenal perforation and fistula occurred. Management focused on wound care and fistula control using vacuum-assisted closure, and octreotyde was indicated, with a successful outcome. Despite surgical attempts, the patient’s family declined further interventions due to the high risk of complications. Eleven years after the initial diagnosis, the patient remains on home PN with a stable clinical course over the past three years. He has type 1 short bowel syndrome with a high-output proximal jejunostomy and a low-output second remaining enterocutaneous fistula.

The second patient, a 4-year-old male, was initially diagnosed with acute appendicitis. An appendectomy was performed. However, postoperatively, the patient developed complications, including a spontaneous perforation of the sigmoid colon. Subsequently, multiple jejunal perforations occurred, requiring several surgical interventions. To manage the complications and optimize enteral nutrition, a jejunostomy was created at 100 cm from the duodeno-jejunal junction. Clinical suspicion for vEDS arose during the postoperative course due to the unusual pattern of multiple bowel perforations. Subsequent genetic testing confirmed a mutation in the COL3A1 gene (c.1662 + 1G > A variant), confirming the molecular diagnosis of vEDS.

This patient met one major criterion (spontaneous intestinal perforation) and four minor criteria, including thin and translucent skin, easy bruising, characteristic facial features, and hypermobility of small joints.

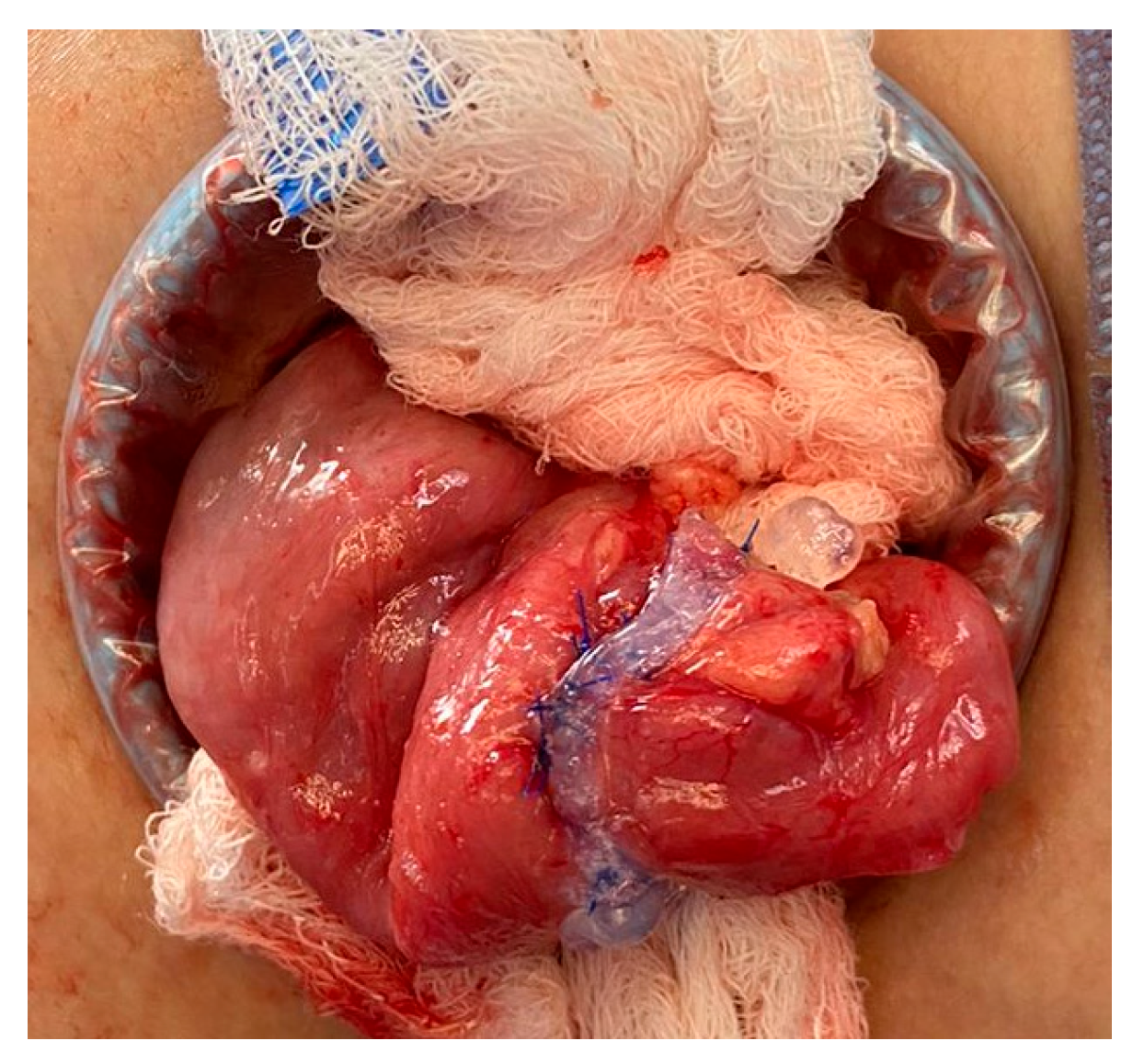

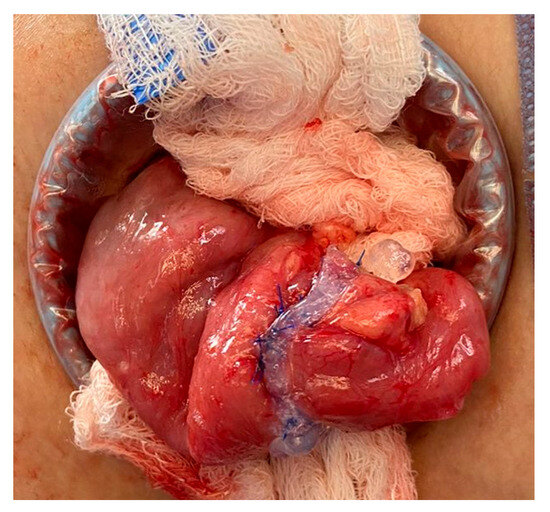

After 18 months of multidisciplinary management of his short bowel syndrome within an intestinal rehabilitation program, a stoma closure procedure was scheduled. Technical modifications to the usual management in similar cases included delicate bowel handling maneuvers, a double-layer anastomosis, use of fibrin sealants, and the avoidance of fast-track postoperative management. No bleeding complications were observed; Figure 1. Enteral autonomy was gradually re-established, and the patient was able to suspend PN.

Figure 1.

Double-line anastomosis and fibrin sealant usage.

Regarding the literature review, the initial database search using the terms “Ehlers-Danlos” AND (“intestinal failure” OR “short bowel” OR “parenteral nutrition”) yielded 11 articles (10 after duplicates removal). After screening titles and abstracts and reviewing full texts, four articles met the inclusion criteria for this review. Of these, two were case reports describing patients with vESD and IF. One case report described a 15-year-old patient, representing the only pediatric case identified in the literature [7]. The other case report involved a 41-year-old patient [10]. The remaining two articles were literature reviews that discussed cases of intestinal complications in vEDS, and these reviews referenced and mentioned the case reports described above, but did not report any new or additional cases [2,5]. Six articles were excluded for the following reasons: four articles focused on intestinal motility disorders in EDS, and two articles discussed anesthetic considerations in EDS. This review highlights the scarcity of pediatric data in the published literature regarding intestinal failure in EDS, with only one pediatric case identified.

4. Discussion

The cases presented describe two patients with severe gastrointestinal complications of vascular EDS requiring complex surgical interventions, leading to short bowel syndrome and intestinal failure. These cases provide an opportunity to review common and infrequent gastroenterological complications of vEDS and best practices when caring for these patients in the pediatric population, in the hope of improving the timely recognition and treatment of this rare disease.

The limited evidence base underscores the need for further research in this area. The reliance on case reports and the absence of larger studies represent significant limitations in the current understanding of this condition. The findings of this review will be discussed in relation to the cases presented in this study, exploring both similarities and any unique aspects observed.

While gastrointestinal complications are well-described in adults with vEDS, with 25% of index patients experiencing a first complication by the age of 20 years and over 80% by the age of 40 [4], there remains a significant paucity of information regarding their presentation and management in the pediatric population. Importantly, gastrointestinal manifestations can be the initial clinical presentation of vEDS in some cases [8]. Due to the rarity of the condition and the lack of specific early diagnostic markers, the diagnosis is frequently delayed [5,8]. Physicians, and especially surgeons, may lack critical information about the patient’s underlying connective tissue disorder. This can significantly impact decision-making, potentially leading to suboptimal treatment strategies and increased risks of complications due to the inherent tissue fragility associated with vEDS.

Although the diagnosis may be overlooked at initial presentation, certain clinical features should raise the suspicion of vEDS. These include typical facial characteristics, a family history of easy bruising, excessive joint laxity, vascular, uterine, or colonic rupture, and spontaneous pneumothorax [5,7,8]. Also, when an intestinal perforation occurs without a clear cause, especially in young patients, the possibility of vEDS should be strongly considered [2]. Spontaneous bowel perforations in young patients should raise concern for an underlying connective tissue disorder, such as vascular EDS, as this is a common first presentation (described in 21% of the patients) [2,6]. In our two patients, initial acute abdominal symptoms were assumed to be appendicitis, needing reintervention for poor clinical postoperative outcomes or surgical complications. This diagnosis delay motivated repeated operations with more tissue damage and the appearance of new intestinal lesions.

Surgeons and gastroenterologists who perform procedures on patients with vEDS must exercise extreme caution, minimizing tissue handling and manipulation due to the inherent tissue fragility [8]. Specific intraoperative risks, such as the propensity for patients with EDS to bleed, cervical spine subluxation during endotracheal intubation, and the potential risk of arterial injury during surgery and central line insertion, should be carefully considered and discussed [5]. Postoperative complications such as anastomotic leakage, enterocutaneous fistulas, stoma problems, severe intra-abdominal adhesions, wound dehiscence, infections, and incisional hernias are also common due to poor tissue quality [5,6,8,12].

Even though short bowel syndrome has been rarely reported in pediatric vEDS, its potential occurrence should be considered given the high risk of intestinal complications. Every surgical decision should prioritize minimizing the risk of bowel resection and the development of short bowel syndrome. Both of our cases presented with intestinal failure secondary to high-output stomas. Although the total remaining bowel length in the first case is unknown, and long enough in the second case, both of them remained dependent on PN for a long period of time, and the care received in the context of the multidisciplinary intestinal rehabilitation program warranted the avoidance of complications during the “waiting” period.

Management of colonic or intestinal perforations in vEDS remains challenging, with no consensus on the optimal surgical approach. Strategies employed include primary repair, primary repair with defunctioning stoma, Hartmann’s procedure, and total abdominal colectomy with either an end-ileostomy or ileorectal anastomosis [2,3,5,12]. Studies have shown higher rates of reperforation after partial colectomy with anastomosis compared to Hartmann’s procedure [2,5].

Some authors advocate for a more aggressive approach, suggesting that total abdominal colectomy with an end-ileostomy may be the safest option for patients with known vEDS to prevent further colonic perforation [3,8]. However, the leak rate of ileorectal anastomosis in this population can be as high as 50%, highlighting the significant risks associated with this approach [5].

Successful outcomes have been reported using different surgical strategies. Duthie et al. described a successful case of laparoscopic management of colonic perforation in a pediatric patient [5,11]. This highlights the potential for minimally invasive approaches in select cases. Also, perioperative bleeding represents a significant concern in vEDS. Desmopressin use has been described by Mast et al. as a potential strategy for reducing perioperative bleeding in these patients [13].

For wound healing and enterocutaneous fistulas, some authors recommend a trial of nonoperative conservative therapy, limiting surgical intervention to life-threatening situations. Still, 98% of the surgical procedures reported in this population are emergent surgeries [5]. Elective surgeries such as stoma takedown should be approached with extreme caution and careful patient and family counseling due to the risk of repeat colonic perforation [5,8]. In the case we operated on, several meetings for discussion of potential risks with the patient and his family were needed before scheduling surgery.

It is crucial to acknowledge that the recommendations described above must be applied with extreme caution and careful consideration in pediatric patients with vEDS, as reported in the cases. In the first place, pediatric patients possess unique characteristics and risks that must be carefully distinguished from the adult population. Secondly, patients with intestinal failure, regardless of their underlying disease, are at significant risk for complications associated with long-term PN, including vascular thrombosis, catheter-related infections, and liver damage. In this context, surgeries aimed at improving intestinal continuity, such as ostomy closure and reconstruction of the gastrointestinal tract, can be fundamental to improving quality of life and reducing the long-term morbidity associated with PN dependence. In addition, optimizing nutritional status in the perioperative period may limit the contribution of malnutrition to poor outcomes [11]. Therefore, the decision to avoid or postpone surgeries, or to resect the colon to prevent perforations, requires careful and individualized consideration in the pediatric population with intestinal failure. Balancing the risks and benefits of surgical intervention in this unique patient group is crucial.

Long-term management of patients with vEDS and IF demands a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach involving a coordinated team of specialists, including gastroenterologists, surgeons, nutritionists, geneticists, and mental health professionals. A cornerstone of care for these patients, particularly those with short bowel syndrome, is nutritional support. PN becomes a necessity to ensure adequate caloric intake, macro- and micronutrient provision, and maintenance of growth and development. However, long-term PN carries its own set of risks, including catheter-related infections, central venous thrombosis, and liver complications. The use of semi-permanent vascular catheters, essential for PN delivery, may introduce a heightened risk of vascular complications in these already vulnerable patients. Given the inherent fragility of blood vessels in vEDS, the insertion and maintenance of these catheters require meticulous technique and vigilant monitoring for signs of thrombosis, infection, or other vascular compromise. Beyond nutritional support, ongoing surveillance for vEDS-related complications is paramount. This includes regular imaging studies to monitor for the development or progression of aneurysms or other vascular abnormalities. Given that these patients are already at increased risk for vascular events, the added stress of catheterizations and the potential for catheter-related complications further underscores the importance of careful monitoring and proactive management. Furthermore, the psychological impact of living with a chronic, life-threatening condition like vEDS, coupled with the challenges of managing intestinal failure and long-term PN, can be significant. Therefore, access to mental health support, including therapy and counseling, is essential to address anxiety, depression, and other emotional challenges. Finally, optimizing quality of life is a central goal. This involves not only managing physical symptoms but also supporting the patient’s social and emotional well-being. Regular follow-up with specialists, open communication between the medical team and the family, and a focus on individualized care are essential for achieving the best possible long-term outcomes for children and adults with vEDS and intestinal failure.

The present report has several limitations, mainly due to the small sample size. Although the review of the existing literature was not systematically performed, no significant published experience in children with vEDS and bowel complications with intestinal failure was found. The issues discussed above are only intended to give the reader more information, but should not be generalized to all patients.

5. Conclusions

This article presents two cases of pediatric patients with vEDS who developed intestinal failure and dependence on long-term PN, and the only other two cases reported in the literature so far. These cases underscore the significant challenges associated with managing gastrointestinal complications in this rare but potentially life-threatening condition.

In the pediatric population, the decision-making process regarding surgical interventions must be carefully individualized, considering the potential benefits and risks in the context of long-term outcomes. While aggressive surgical approaches, such as total colectomy, may be considered to prevent future perforations, the high rate of complications associated with these procedures, particularly in the pediatric population with intestinal failure, necessitates a cautious and individualized approach.

The management of pediatric patients with vEDS and intestinal failure requires a multidisciplinary approach involving pediatricians, surgeons, gastroenterologists, geneticists, and nutritionists. Early diagnosis and close monitoring are crucial for optimizing patient outcomes. Further research is needed to better understand the natural history of gastrointestinal complications in pediatric vEDS, develop evidence-based treatment guidelines, and improve long-term outcomes for these patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.P. and P.A.L. Methodology: C.P. and P.A.L. Investigation: C.P. and P.A.L. Writing—original draft preparation: C.P. Writing—review and editing: C.P., P.A.L., V.B. and C.I. Supervision: P.A.L. Validation: P.A.L., V.B. and C.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for retrospective study.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EDS | Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome |

| vEDS | Vascular Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome |

| IF | Intestinal Failure |

| PN | Parenteral Nutrition |

| AD | Autosomal Dominant |

| AR | Autosomal Recessive |

References

- Fuchs, J.R.; Fishman, S.J. Management of spontaneous colonic perforation in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2004, 39, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Masri, H.; Loong, T.H.; Meurette, G.; Podevin, J.; Zinzindohoue, F.; Lehur, P.A. Bowel perforation in type IV vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. A systematic review. Tech. Coloproctol. 2018, 22, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burcharth, J.; Rosenberg, J. Gastrointestinal surgery and related complications in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: A systematic review. Dig. Surg. 2012, 29, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepin, M.; Schwarze, U.; Superti-Furga, A.; Byers, P.H. Clinical and genetic features of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, the vascular type. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speake, D.; Dvorkin, L.; Vaizey, C.J.; Carlson, G.L. Management of colonic complications of type IV Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: A systematic review and evidence-based management strategy. Colorectal Dis. 2020, 22, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adham, S.; MZinzindohoué, F.; Jeunemaitre, X.; Frank, M. Natural History and Surgical Management of Colonic Perforations in Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: A Retrospective Review. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2019, 62, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemrani, B.; McLeod, E.; Rogers, E.; Lawrence, J.; Feldman, D.; Evans, V.; Shalley, H.; Bines, J. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: An Unusual Cause of Chronic Intestinal Failure in a Child. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, e14–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sceats, L.A.; Sukerkar, P.A.; Raghavan, S.S.; Esmaeili Shandiz, A.; Shelton, A.; Kin, C. Fragility of Life: Recurrent Intestinal Perforation Due to Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 2120–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, P.H.; Belmont, J.; Black, J.; De Backer, J.; Frank, M.; Jeunemaitre, X.; Johnson, D.; Pepin, M.; Robert, L.; Sanders, L.; et al. Diagnosis, natural history, and management in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2017, 175, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malfait, F.; Francomano, C.; Byers, P.; Belmont, J.; Berglund, B.; Black, J.; Bloom, L.; Bowen, J.M.; Brady, A.F.; Burrows, N.P.; et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2017, 175, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berney, T.; La Scala, G.; Vettorel, D.; Gumowski, D.; Hauser, C.; Frileux, P.; Ambrosetti, P.; Rohner, A. Surgical pitfalls in a patient with type IV Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and spontaneous colonic rupture. Report of a case. Dis. Colon Rectum 1994, 37, 1038–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duthie, G.; Singh, M.; Jester, I. Laparoscopic management of colonic complications in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2012, 47, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mast, K.J.; Nunes, M.E.; Ruymann, F.B.; Kerlin, B.A. Desmopressin responsiveness in children with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome associated bleeding symptoms. Br. J. Haematol. 2009, 144, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).