Abstract

Lung cancer is listed as the most fatal type of cancer around the world. ERG, a transcription factor, is an ETS family member protein. It is involved in Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT), metastasis and DNA repair defects. Etoposide is a chemotherapeutic agent used in treatment of a variety of different cancer types, including lung cancer. Moreover, Etoposide has been tested alone and in combination with other drugs in order to inhibit DNA synthesis and exhibit antitumor activity. The purpose of this study is to examine the effect of Etoposide treatment on ERG transfected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell line, H358.

1. Introduction

Cancer is characterized by unrestrained growth and spread of abnormal cells. Lung carcinoma is listed as the number one cause of cancer death in the world and categorized into two major groups: small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is observed in about 20% of all lung carcinomas, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is observed in about 80–85% of all lung cancers [1].

ERG transcription factor belongs to ETS family, which is associated with regulation of gene expression profiles affecting proliferation, migration and epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) [2]. EMT is a biological process whereby epithelial cells acquire migratory and invasive properties of mesenchymal cells. However, in cancer, EMT is involved in tumor progression, invasion and metastasis [3].

Previous studies demonstrated that high expression of ERG transcription factor in prostate cancer is related with motility and invasion [4]. Furthermore, ERG is shown to be included in pathway aberrations of DNA repair mechanism [5]. Etoposide is an anticancer agent that has the ability to break the double stranded DNA and prevent repair mechanism through interaction with topoisomerase II [6]. Etoposide is widely used alone or in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents in different cancer types including lung cancer [7].

In this current study, effect of Etoposide is analysed in H358 cell line transfected with the ERG transcription factor.

2. Materials and Methods

H358 cell line was obtained from the American Tissue and Cell Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were cultivated in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Wisent, Saint-Jean-Baptiste, QC, Canada) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5%CO2. Etoposide (purity ≥ 98%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in DMSO, the final concentration on DMSO was 0.1% in all experiments.

ERG plasmid (pERG) and Empty Vector plasmid (pEV) were transferred into competent E. coli TOP10 cells through heat shock transformation procedure. Transformation is followed by plasmid DNA isolation by using PureLink® HiPure Plasmid Midiprep kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The presence and size of individual plasmids were confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Before transfection, cell number and transfection agent to DNA ratio optimizations were performed. A day before transfection, 5 × 105–9 × 105 cells were seeded in dishes for 70–90% confluency and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with 5%CO2. The following day, Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and DNA plasmid were mixed and diluted in OptiMEM (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) with 2:1 ratio ((transfection agent (µL): DNA (µg)) and added to the cells. Cells were then incubated for 48 h. Following incubation, total RNA was isolated using PureLink RNA isolation kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The total RNA concentration and purity values were determined using MultiScan GO Microplate Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Transfection was confirmed by monitoring the expression level of the ERG gene in qRT-PCR using iTaqTM Universal SYBR® Green One-Step kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

For cell proliferation assay, ERG transfected cells were trypsinized and seeded at a density of 5 × 103–1 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h. The cells were then treated with different concentrations of Etoposide for 48 h. After treatment, WST-1 reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well and absorbance (420–480 nm) was measured using MultiScan GO Microplate Spectrophotometer. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of Etoposide was calculated using GraphPad Prism software program.

3. Results

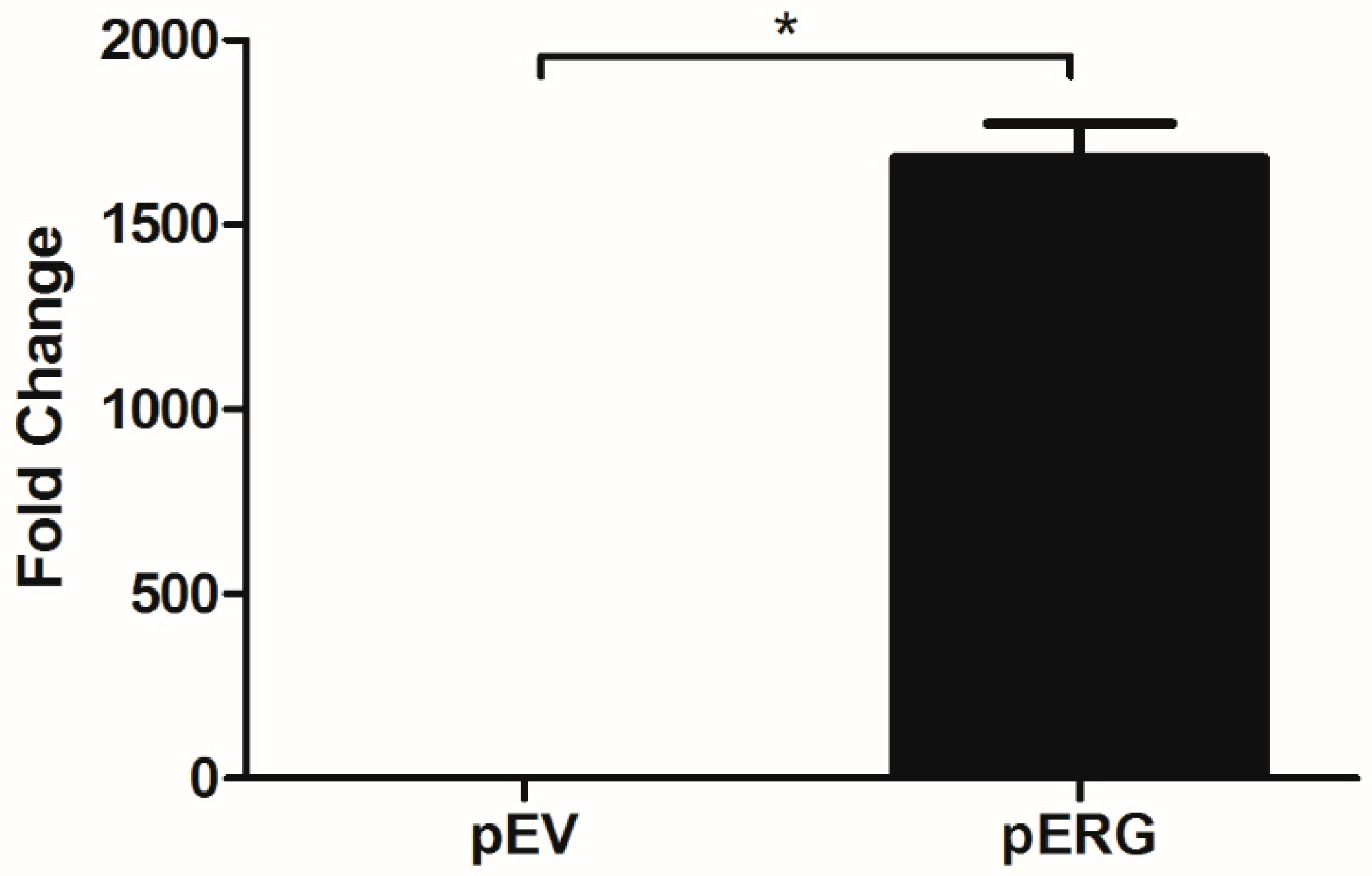

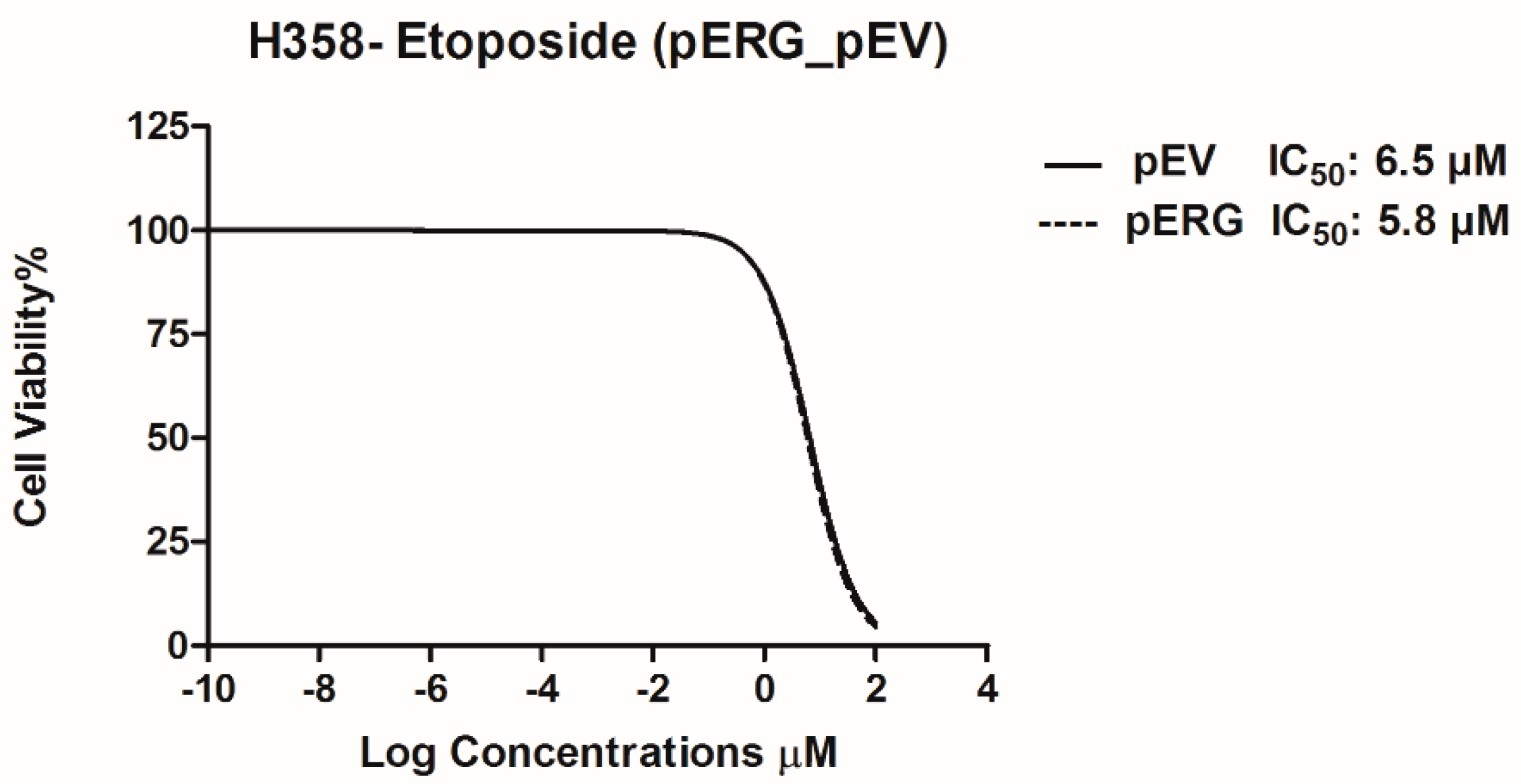

In this study, effect of Etoposide is analysed in H358 cell line overexpressing the ERG transcription factor. In the first step, ERG gene expression in H358 cells was shown to increase ~1700 fold after transfection with the pERG plasmid (Figure 1). The effect of Etoposide on cell proliferation in ERG transfected H358 cell line was analysed using WST-1 Cell Proliferation Assay Kit. The IC50 value of Etoposide on ERG overexpressing H358 cell line was 5.8 µM, whereas the IC50 value of Etoposide on the same cells with basal ERG expression level (transfected with the empty vector) was 6.5 µM. According to this data, Etoposide did not show any significant effect on cell proliferation of ERG overexpressing H358 cells (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Expression analysis of ERG in H358 cell line transfected with pEV and pERG plasmids using qRT-PCR (*: p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

IC50 graphs of pERG and pEV transfected H358 cell line after treatment with Etoposide.

4. Discussion

Several studies have been conducted to examine the possibility of targeting DNA repair pathways in cancer cells. Recent studies have shown that ERG transcription factor promotes cancer progression and is involved in DNA repair mechanism due to the formation of genomic rearrangements in prostate cancer cells [8]. Etoposide is a chemotherapeutic drug that targets DNA repair mechanisms. Based on this information, it was aimed to analyse the possible effects of Etoposide treatment on ERG overexpressing H358 NSCLC cells. The data obtained from this study did not provide any significant effect of Etoposide treatment on proliferation states of H358 NSCLC cells with high and basal level of ERG expression.

Author Contributions

E.K. and G.B. conceived and designed the experiments and wrote the paper; S.A., B.S. and G.B. analysed the data.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) [grant number 1001-114S428 (PI: Gülay Bulut)].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zappa, C.; Mousa, S.A. Non-small cell lung cancer: Current treatment and future advances. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2016, 5, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.P.; Watson, D.K. ETS transcription factors: Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes as therapeutic targets for prostate cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2008, 8:1, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Bueno, G.; Portillo, F.; Cano, A. Transcriptional regulation of cell polarity in EMT and cancer. Oncogene 2008, 27, 6958–6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahim, S.; Beauchamp, E.M.; Kong, Y.; Brown, M.L.; Toretsky, J.A.; Uren, A. YK-4-279 inhibits ERG and ETV1 mediated prostate cancer cell invasion. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo, J.; Boysen, G.; Barbieri, C.E.; Bryant, H.E.; Castro, E.; Nelson, P.S.; Olmos, D.; Pritchard, C.C.; Rubin, M.A.; de Bono, J.S. DNA Repair in Prostate Cancer: Biology and Clinical Implications. Eur. Urol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezonja, R.; Knez, L.; Cufer, T.; Mrhar, A. Oral Treatment with Etoposide in Small Cell Lung Cancer—Dilemmas and Solutions. Radiol. Oncol. 2013, 47, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faivre, C.; El Cheikh, R.; Barbolosi, D.; Barlesi, F. Mathematical optimisation of the cisplatin plus etoposide combination for managing extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Li, X.; Baek, G.; Ramanand, S.G.; Sharp, A.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, W.; Welti, J.; Rodrigues, D.N.; Dolling, D.; Figueiredo, I.; et al. BRD4 Promotes DNA Repair and Mediates the Formation of TMPRSS2-ERG Gene Rearrangements in Prostate Cancer. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 796–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).