Paclitaxel’s Mechanistic and Clinical Effects on Breast Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Breast Cancer from the View of Prevalence and Intrinsic Subtypes

3. Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer

4. Paclitaxel: Fundamental Drug in Chemotherapy and Novel Advances in its Application

4.1. The Origin of Paclitaxel

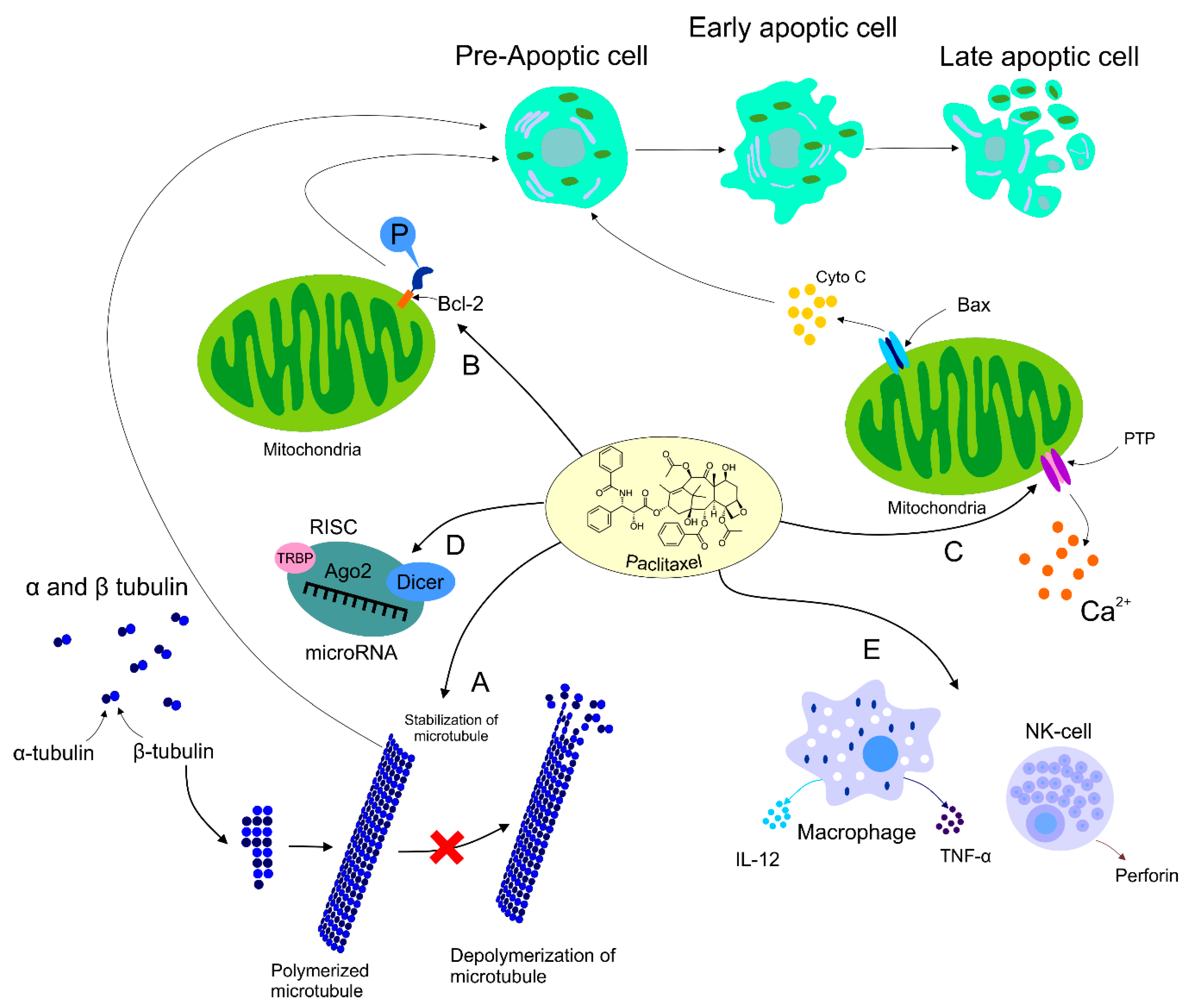

4.2. Paclitaxel’s Mechanism of Action

4.3. Paclitaxel’s Effect on HER2+ Breast Cancer

4.4. Dose Ranges Administered

4.5. Breast Tumor Resistance to Paclitaxel

4.6. Paclitaxel’s Side Effects

4.7. Albumin-Bound Paclitaxel and Comparison with Its Conventional Alternative

5. Novel Insights into the Application of Paclitaxel in Clinical Practice

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clatici, V.G.; Voicu, C.; Voaides, C.; Roseanu, A.; Icriverzi, M.; Jurcoane, S. Diseases of civilization—Cancer, diabetes, obesity and acne—The implication of milk, IGF-1 and mTORC1. Mædica 2018, 13, 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Mathers, C.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.W.S.; Wu, M.; Cho, W.C.S.; To, K.K.W. Recent advances in the treatment of breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abotaleb, M.; Kubatka, P.; Caprnda, M.; Varghese, E.; Zolakova, B.; Zubor, P.; Opatrilova, R.; Kruzliak, P.; Stefanicka, P.; Büsselberg, D. Chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer: An update. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 101, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vici, P.; Viola, G.; Rossi, S.; Botti, C.; Vitucci, C.; Sergi, D.; Ferranti, F.R.; Saracca, E.; Di Lauro, L.; Corsetti, S.; et al. Optimal sequence of anthracyclines and taxanes as adjuvant breast cancer treatment. Clin. Ter. 2008, 159, 453–456. [Google Scholar]

- Kellokumpu-Lehtinen, P.; Tuunanen, T.; Asola, R.; Elomaa, L.; Heikkinen, M.; Kokko, R.; Järvenpää, R.; Lehtinen, I.; Maiche, A.; Kaleva-Kerola, J.; et al. Weekly paclitaxel—An effective treatment for advanced breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33, 2623–2627. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vuuren, R.J.; Visagie, M.H.; Theron, A.E.; Joubert, A.M. Antimitotic drugs in the treatment of cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 76, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrogan, B.T.; Gilmartin, B.; Carney, D.N.; McCann, A. Taxanes, microtubules and chemoresistant breast cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1785, 96–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuyoshi, S.; Shimada, K.; Nakamura, M.; Ishida, E.; Konishi, N. Bcl-2 phosphorylation has pathological significance in human breast cancer. Pathobiol. J. Immunopathol. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 73, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Avila, A.; Gollahon, L. Paclitaxel induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells through different calcium—Regulating mechanisms depending on external calcium conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 2672–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanderley, C.W.; Colon, D.F.; Luiz, J.P.M.; Oliveira, F.F.; Viacava, P.R.; Leite, C.A.; Pereira, J.A.; Silva, C.M.; Silva, C.R.; Silva, R.L.; et al. Paclitaxel reduces tumor growth by reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages to an M1- profile in a TLR4-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 5891–5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panis, C.; Pavanelli, W.R. Cytokines as mediators of pain-related process in breast cancer. Mediators Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 129034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudo, T.; Nitta, M.; Saya, H.; Ueno, N.T. Dependence of paclitaxel sensitivity on a functional spindle assembly checkpoint. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 2502–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Tian, W.; He, H.; Chen, F.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z. Downregulation of miR-200c-3p contributes to the resistance of breast cancer cells to paclitaxel by targeting SOX2. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 3821–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Sato, N.; Yanai, K.; Akiyoshi, T.; Nagai, S.; Wada, J.; Koga, K.; Mibu, R.; Nakamura, M.; Katano, M. Enhancement of Paclitaxel-induced apoptosis by inhibition of mitogen-activated protein Kinase pathway in colon cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Mahtani, R.L.; Parisi, M.; Glück, S.; Ni, Q.; Park, S.; Pelletier, C.; Faria, C.; Braiteh, F. Comparative effectiveness of early-line nab-paclitaxel vs. paclitaxel in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A US community-based real-world analysis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, K.; Steel, C.M.; Dixon, J.M. Breast cancer—Epidemiology, risk factors, and genetics. BMJ 2000, 321, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, J.L.; Horn-Ross, P.L. Breast cancer: Magnitude of the problem and descriptive epidemiology. Epidemiol. Rev. 1993, 15, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; van Jaarsveld, M.T.M.; Hollestelle, A.; Prager-van der Smissen, W.J.C.; Heine, A.A.J.; Boersma, A.W.M.; Liu, J.; Helmijr, J.; Ozturk, B.; Smid, M.; et al. miRNA expression profiling of 51 human breast cancer cell lines reveals subtype and driver mutation-specific miRNAs. Breast Cancer Res. BCR 2013, 15, R33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turashvili, G.; Brogi, E. Tumor heterogeneity in breast cancer. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubor, P.; Kubatka, P.; Dankova, Z.; Gondova, A.; Kajo, K.; Hatok, J.; Samec, M.; Jagelkova, M.; Krivus, S.; Holubekova, V.; et al. miRNA in a multiomic context for diagnosis, treatment monitoring and personalized management of metastatic breast cancer. Future Oncol. Lond. Engl. 2018, 14, 1847–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, T.; Sudo, C.; Ogawara, H.; Toyoshima, K.; Yamamoto, T. The product of the human c-erbB-2 gene: A 185-kilodalton glycoprotein with tyrosine kinase activity. Science 1986, 232, 1644–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Iqbal, N. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) in Cancers: Overexpression and Therapeutic Implications. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/mbi/2014/852748/ (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- Yao, Y.; Chu, Y.; Xu, B.; Hu, Q.; Song, Q. Risk factors for distant metastasis of patients with primary triple-negative breast cancer. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, I.; Topcul, M. Triple negative breast cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 2427–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guney Eskiler, G.; Cecener, G.; Egeli, U.; Tunca, B. Triple negative breast cancer: New therapeutic approaches and BRCA status. APMIS 2018, 126, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jung, W.H.; Koo, J.S. Differences in autophagy-related activity by molecular subtype in triple-negative breast cancer. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. Oncodevelopmental Biol. Med. 2012, 33, 1681–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afghahi, A.; Telli, M.L.; Kurian, A.W. Genetics of triple-negative breast cancer: Implications for patient care. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2016, 40, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimelis, H.; LaDuca, H.; Hu, C.; Hart, S.N.; Na, J.; Thomas, A.; Akinhanmi, M.; Moore, R.M.; Brauch, H.; Cox, A.; et al. Triple-negative breast cancer risk genes identified by multigene hereditary cancer panel testing. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yersal, O. Biological subtypes of breast cancer: Prognostic and therapeutic implications. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 5, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheang, M.C.U.; Chia, S.K.; Voduc, D.; Gao, D.; Leung, S.; Snider, J.; Watson, M.; Davies, S.; Bernard, P.S.; Parker, J.S.; et al. Ki67 index, HER2 status, and prognosis of patients with luminal B breast cancer. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 736–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perou, C.M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; van de Rijn, M.; Rees, C.A.; Eisen, M.B.; Ross, D.T.; Pergamenschikov, A.; Williams, C.F.; Zhu, S.X.; Lee, J.C.F.; et al. Distinctive gene expression patterns in human mammary epithelial cells and breast cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 9212–9217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widodo, I.; Dwianingsih, E.; Anwar, S.; Triningsih, F.; Utoro, T.; Aryandono, T.; Soeripto. Prognostic value of clinicopathological factors for indonesian breast carcinomas of different molecular subtypes. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Goodspeed, A.; Heiser, L.M.; Gray, J.W.; Costello, J.C. Tumor-derived cell lines as molecular models of cancer pharmacogenomics. Mol. Cancer Res. 2016, 14, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Cheng, H.; Bai, Z.; Li, J. Breast cancer cell line classification and its relevance with breast tumor subtyping. J. Cancer 2017, 8, 3131–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, D.L.; Speirs, V. Choosing the right cell line for breast cancer research. Breast Cancer Res. BCR 2011, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neve, R.M.; Chin, K.; Fridlyand, J.; Yeh, J.; Baehner, F.L.; Fevr, T.; Clark, L.; Bayani, N.; Coppe, J.-P.; Tong, F.; et al. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell 2006, 10, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charafe-Jauffret, E.; Ginestier, C.; Monville, F.; Finetti, P.; Adélaïde, J.; Cervera, N.; Fekairi, S.; Xerri, L.; Jacquemier, J.; Birnbaum, D.; et al. Gene expression profiling of breast cell lines identifies potential new basal markers. Oncogene 2006, 25, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kao, J.; Salari, K.; Bocanegra, M.; Choi, Y.-L.; Girard, L.; Gandhi, J.; Kwei, K.A.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; Wang, P.; Gazdar, A.F.; et al. Molecular profiling of breast cancer cell lines defines relevant tumor models and provides a resource for cancer gene discovery. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, K.; Dvorkin-Gheva, A.; Hallett, R.M.; Wu, Y.; Hassell, J.; Pond, G.R.; Levine, M.; Whelan, T.; Bane, A.L. Claudin-low breast cancer; clinical & pathological characteristics. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168669. [Google Scholar]

- Shewach, D.S.; Kuchta, R.D. Introduction to cancer chemotherapeutics. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2859–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falzone, L.; Salomone, S.; Libra, M. Evolution of cancer pharmacological treatments at the turn of the third millennium. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beane, O.S.; Darling, L.E.O.; Fonseca, V.C.; Darling, E.M. Disparate response to methotrexate in stem versus non-stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2016, 12, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson-Arbor, K.; Dubey, R. Doxorubicin. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso, V.; Manzione, L.; Silvestris, N. Role of liposomal anthracyclines in breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2007, 18 (Suppl. 6), vi70–vi73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Teves, S.S.; Kemp, C.J.; Henikoff, S. Doxorubicin, DNA torsion, and chromatin dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1845, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jasra, S.; Anampa, J. Anthracycline use for early stage breast cancer in the modern era: A review. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2018, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Aranda, M.; Redondo, M. Protein Kinase targets in breast cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Si, W.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, P.; Han, C.; You, J.H.; Linghu, R.X.; Jiao, S.C.; Yang, J.L. Capecitabine maintenance therapy in patients with recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2013, 46, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ayoub, N.M.; Al-Shami, K.M.; Yaghan, R.J. Immunotherapy for HER2-positive breast cancer: Recent advances and combination therapeutic approaches. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2019, 11, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lumachi, F.; Luisetto, G.; Basso, S.; Basso, U.; Brunello, A.; Camozzi, V. Endocrine therapy of breast cancer. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Kwon, G.S. Epothilone B-based 3-in-1 polymeric micelle for anticancer drug therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 518, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shetty, N.; Gupta, S. Eribulin drug review. South Asian J. Cancer 2014, 3, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yardley, D.A. Taxanes in the elderly patient with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2015, 7, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- A’Hern, R.P.; Jamal-Hanjani, M.; Szász, A.M.; Johnston, S.R.D.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Roylance, R.; Swanton, C. Taxane benefit in breast cancer—A role for grade and chromosomal stability. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Long, D.; Yu, T.; Chen, X.; Liao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Lin, X. Vinblastine differs from Taxol as it inhibits the malignant phenotypes of NSCLC cells by increasing the phosphorylation of Op18/stathmin. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 2481–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, B.A. How Taxol/paclitaxel kills cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 2677–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, V.; Goodman, J. From taxol to Taxol: The changing identities and ownership of an anti-cancer drug. Med. Anthropol. 2002, 21, 307–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Raza, K.; Kaushik, L.; Malik, R.; Arora, S.; Katare, O.P. Role of colloidal drug delivery carriers in Taxane-mediated chemotherapy: A review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 5127–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, R.E.; Hartwell, J.T. Search for plant sources of anticancer drugs. Morris Arbor. Bull 1969, 20, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, V.; Goodman, J. Cancer chemotherapy, biodiversity, public and private property: The case of the anti-cancer drug taxol. Soc. Sci. Med. 1982 1999, 49, 1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, R.A.; Kim, H.B.; Somoza, C.; Liang, F.; Biediger, R.J.; Boatman, P.D.; Shindo, M.; Smith, C.C.; Kim, S. First total synthesis of taxol. 2. Completion of the C and D rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 1599–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stierle, A.; Strobel, G.; Stierle, D. Taxol and taxane production by Taxomyces andreanae, an endophytic fungus of Pacific yew. Science 1993, 260, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackett, D.; Fojo, T. Taxanes. Cancer Chemother. Biol. Response Modif. 1997, 17, 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Schiff, P.B.; Fant, J.; Horwitz, S.B. Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by taxol. Nature 1979, 277, 665–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowinsky, E.K.; Cazenave, L.A.; Donehower, R.C. Taxol: A novel investigational antimicrotubule agent. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990, 82, 1247–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.A.; Vallee, R.B. Temperature-dependent reversible assembly of taxol-treated microtubules. J. Cell Biol. 1987, 105, 2847–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brabander, M.; Geuens, G.; Nuydens, R.; Willebrords, R.; De Mey, J. Taxol induces the assembly of free microtubules in living cells and blocks the organizing capacity of the centrosomes and kinetochores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 5608–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jordan, M.A.; Toso, R.J.; Thrower, D.; Wilson, L. Mechanism of mitotic block and inhibition of cell proliferation by taxol at low concentrations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 9552–9556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jordan, M.A.; Wilson, L. Microtubules and actin filaments: Dynamic targets for cancer chemotherapy. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1998, 10, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, B.H.; Fairchild, C.R. Paclitaxel inhibits progression of mitotic cells to G1 phase by interference with spindle formation without affecting other microtubule functions during anaphase and telephase. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 4355–4361. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakakou, P.; Robey, R.; Fojo, T.; Blagosklonny, M.V. Low concentrations of paclitaxel induce cell type-dependent p53, p21 and G1/G2 arrest instead of mitotic arrest: Molecular determinants of paclitaxel-induced cytotoxicity. Oncogene 2001, 20, 3806–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tran, T.-A.; Gillet, L.; Roger, S.; Besson, P.; White, E.; Le Guennec, J.-Y. Non-anti-mitotic concentrations of taxol reduce breast cancer cell invasiveness. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 379, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetti, D.; Zhang, B.; Fan, C.; Mo, C.; Lee, B.H.; Wei, K. Low dose of paclitaxel combined with XAV939 attenuates metastasis, angiogenesis and growth in breast cancer by suppressing Wnt signaling. Cells 2019, 8, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blagosklonny, M.V.; Giannakakou, P.; el-Deiry, W.S.; Kingston, D.G.; Higgs, P.I.; Neckers, L.; Fojo, T. Raf-1/bcl-2 phosphorylation: A step from microtubule damage to cell death. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Haldar, S.; Basu, A.; Croce, C.M. Bcl2 is the guardian of microtubule integrity. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Y.H.; Yang, Y.; Tornos, C.; Singh, B.; Perez-Soler, R. Paclitaxel-induced apoptosis is associated with expression and activation of c-Mos gene product in human ovarian carcinoma SKOV3 cells. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 3633–3640. [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny, M.V.; Fojo, T. Molecular effects of paclitaxel: Myths and reality (a critical review). Int. J. Cancer 1999, 83, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, S.; Chintapalli, J.; Croce, C.M. Taxol induces bcl-2 phosphorylation and death of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 1253–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrado, A.M.; Liu, L.; Bhalla, K. Bcl-xL overexpression inhibits progression of molecular events leading to paclitaxel-induced apoptosis of human acute myeloid leukemia HL-60 cells. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Blajeski, A.L.; Kottke, T.J.; Kaufmann, S.H. A multistep model for Paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cell lines. Exp. Cell Res. 2001, 270, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofir, R.; Seidman, R.; Rabinski, T.; Krup, M.; Yavelsky, V.; Weinstein, Y.; Wolfson, M. Taxol-induced apoptosis in human SKOV3 ovarian and MCF7 breast carcinoma cells is caspase-3 and caspase-9 independent. Cell Death Differ. 2002, 9, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Varbiro, G.; Veres, B.; Gallyas, F.; Sumegi, B. Direct effect of Taxol on free radical formation and mitochondrial permeability transition. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 31, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, J.F.; Pilkington, M.F.; Schell, M.J.; Fogarty, K.E.; Skepper, J.N.; Taylor, C.W.; Thorn, P. Paclitaxel affects cytosolic calcium signals by opening the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 6504–6510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Asghari, F.; Haghnavaz, N.; Shanehbandi, D.; Khaze, V.; Baradaran, B.; Kazemi, T. Differential altered expression of let-7a and miR-205 tumor-suppressor miRNAs in different subtypes of breast cancer under treatment with Taxol. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. Off. Organ Wroclaw Med. Univ. 2018, 27, 941–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tao, W.-Y.; Liang, X.-S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.-Y.; Pang, D. Decrease of let-7f in low-dose metronomic paclitaxel chemotherapy contributed to upregulation of thrombospondin-1 in breast cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 11, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Javeed, A.; Ashraf, M.; Riaz, A.; Ghafoor, A.; Afzal, S.; Mukhtar, M.M. Paclitaxel and immune system. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. Off. J. Eur. Fed. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 38, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, I.; Cherdyntseva, N.; Liu, T.; Patysheva, M.; Rakina, M.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Interaction of tumor-associated macrophages and cancer chemotherapy. OncoImmunology 2019, 8, e1596004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Emens, L.A.; Jaffee, E.M. Leveraging the activity of tumor vaccines with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 8059–8064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, J.; Ismail, M.; Riley, C.; Askham, J.; Morgan, R.; Melcher, A.; Pandha, H. Differential effects of Paclitaxel on dendritic cell function. BMC Immunol. 2010, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kubo, M.; Morisaki, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Tasaki, A.; Yamanaka, N.; Nakashima, H.; Kuroki, H.; Nakamura, K.; Nakamura, M.; Katano, M. Paclitaxel probably enhances cytotoxicity of natural killer cells against breast carcinoma cells by increasing perforin production. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. CII 2005, 54, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Jing, T.; Liu, B.; Yao, J.; Tan, M.; McDonnell, T.J.; Hung, M.C. Overexpression of ErbB2 blocks Taxol-induced apoptosis by upregulation of p21Cip1, which inhibits p34Cdc2 kinase. Mol. Cell 1998, 2, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.F.; Thor, A.D.; Dressler, L.G.; Weaver, D.; Edgerton, S.; Cowan, D.; Broadwater, G.; Goldstein, L.J.; Martino, S.; Ingle, J.N.; et al. HER2 and response to paclitaxel in node-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baselga, J.; Seidman, A.D.; Rosen, P.P.; Norton, L. HER2 overexpression and paclitaxel sensitivity in breast cancer: Therapeutic implications. Oncol. Williston Park N Y 1997, 11 (Suppl. 2), 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny, M.V.; Schulte, T.W.; Nguyen, P.; Mimnaugh, E.G.; Trepel, J.; Neckers, L. Taxol induction of p21WAF1 and p53 requires c-raf-1. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 4623–4626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Winer, E.P.; Berry, D.A.; Woolf, S.; Duggan, D.; Kornblith, A.; Harris, L.N.; Michaelson, R.A.; Kirshner, J.A.; Fleming, G.F.; Perry, M.C.; et al. Failure of higher-dose paclitaxel to improve outcome in patients with metastatic breast cancer: cancer and leukemia group B trial 9342. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 2061–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielmann, M. Taxol (Paclitaxel) in patients with metastatic breast carcinoma who have failed prior chemotherapy: Interim results of a multinational study. Oncology 1994, 51, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparano, J.A.; Wang, M.; Martino, S.; Jones, V.; Perez, E.A.; Saphner, T.; Wolff, A.C.; Sledge, G.W.; Wood, W.C.; Davidson, N.E. Weekly paclitaxel in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1663–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, L.; Munzone, E.; Capri, G.; Fulfaro, F.; Tarenzi, E.; Villani, F.; Spreafico, C.; Laffranchi, A.; Caraceni, A.; Martini, C. Paclitaxel by 3-hour infusion in combination with bolus doxorubicin in women with untreated metastatic breast cancer: High antitumor efficacy and cardiac effects in a dose-finding and sequence-finding study. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 1995, 13, 2688–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, A.D.; Hudis, C.A.; Albanell, J.; Albanel, J.; Tong, W.; Tepler, I.; Currie, V.; Moynahan, M.E.; Theodoulou, M.; Gollub, M.; et al. Dose-dense therapy with weekly 1-hour paclitaxel infusions in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 3353–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamounas, E.P.; Bryant, J.; Lembersky, B.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Sedlacek, S.M.; Fisher, B.; Wickerham, D.L.; Yothers, G.; Soran, A.; Wolmark, N. Paclitaxel after doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide as adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer: Results from NSABP B-28. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3686–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samec, M.; Liskova, A.; Kubatka, P.; Uramova, S.; Zubor, P.; Samuel, S.M.; Zulli, A.; Pec, M.; Bielik, T.; Biringer, K.; et al. The role of dietary phytochemicals in the carcinogenesis via the modulation of miRNA expression. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 1665–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolaney, S.M.; Barry, W.T.; Dang, C.T.; Yardley, D.A.; Moy, B.; Marcom, P.K.; Albain, K.S.; Rugo, H.S.; Ellis, M.; Shapira, I.; et al. Adjuvant Paclitaxel and Trastuzumab for node-negative, HER2-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burstein, H.J.; Harris, L.N.; Gelman, R.; Lester, S.C.; Nunes, R.A.; Kaelin, C.M.; Parker, L.M.; Ellisen, L.W.; Kuter, I.; Gadd, M.A.; et al. Preoperative therapy with trastuzumab and paclitaxel followed by sequential adjuvant doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide for HER2 overexpressing stage II or III breast cancer: A pilot study. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichman, B.S.; Seidman, A.D.; Crown, J.P.; Heelan, R.; Hakes, T.B.; Lebwohl, D.E.; Gilewski, T.A.; Surbone, A.; Currie, V.; Hudis, C.A. Paclitaxel and recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor as initial chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993, 11, 1943–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, Y.; Xue, J.; Huang, S.; Xiu, B.; Su, Y.; Wang, W.; Guo, R.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Shao, Z.; et al. CapG promotes resistance to paclitaxel in breast cancer through transactivation of PIK3R1/P50. Theranostics 2019, 9, 6840–6855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Vo, T.; Hajar, A.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Parissenti, A.M.; Brindley, D.N.; Wang, Z. Multiple mechanisms underlying acquired resistance to taxanes in selected docetaxel-resistant MCF-7 breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Li, J.; Yan, Y.; Wu, W. Sulforaphane metabolites reduce resistance to paclitaxel via microtubule disruption. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Němcová-Fürstová, V.; Kopperová, D.; Balušíková, K.; Ehrlichová, M.; Brynychová, V.; Václavíková, R.; Daniel, P.; Souček, P.; Kovář, J. Characterization of acquired paclitaxel resistance of breast cancer cells and involvement of ABC transporters. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2016, 310, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, S.; Ling, V. The MDR superfamily of genes and its biological implications. Important Adv. Oncol. 1994, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, D.; Yan, M.; Kamran, M.; Liu, Q.; Xu, B. Aurora kinase A stabilizes FOXM1 to enhance paclitaxel resistance in triple-negative breast cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 6442–6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khongkow, P.; Gomes, A.R.; Gong, C.; Man, E.P.S.; Tsang, J.W.-H.; Zhao, F.; Monteiro, L.J.; Coombes, R.C.; Medema, R.H.; Khoo, U.S.; et al. Paclitaxel targets FOXM1 to regulate KIF20A in mitotic catastrophe and breast cancer paclitaxel resistance. Oncogene 2016, 35, 990–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rouzier, R.; Rajan, R.; Wagner, P.; Hess, K.R.; Gold, D.L.; Stec, J.; Ayers, M.; Ross, J.S.; Zhang, P.; Buchholz, T.A.; et al. Microtubule-associated protein tau: A marker of paclitaxel sensitivity in breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8315–8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Magee, P.; Shi, L.; Garofalo, M. Role of microRNAs in chemoresistance. Ann. Transl. Med. 2015, 3, 332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Hua, T.; You, X.; Lou, J.; Yang, X.; Tang, N. Effects of MiR-107 on the chemo-drug sensitivity of breast cancer cells. Open Med. 2019, 14, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Cheng, J.; Cao, X.; Surowy, H.; Burwinkel, B. Blood-based DNA methylation as biomarker for breast cancer: A systematic review. Clin. Epigenetics 2016, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lv, K.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Yu, J.; Liu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Dong, M.; Teng, R.; Wu, L.; Fu, P.; et al. Lin28 mediates paclitaxel resistance by modulating p21, Rb and Let-7a miRNA in breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-K.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Y.-Y.; Zhao, P.; Bian, Z.-J. MicroRNA-22 suppresses breast cancer cell growth and increases Paclitaxel sensitivity by targeting NRAS. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasham, A.; Mehta, S.Y.; Fitzgerald, S.J.; Woolley, A.G.; Hearn, J.I.; Hurley, D.G.; Ruza, I.; Algie, M.; Shelling, A.N.; Braithwaite, A.W.; et al. A novel EGR-1 dependent mechanism for YB-1 modulation of paclitaxel response in a triple negative breast cancer cell line: EGR-1-dependent mechanism for YB-1 modulation. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nestal de Moraes, G.; Ji, Z.; Fan, L.Y.-N.; Yao, S.; Zona, S.; Sharrocks, A.D.; Lam, E.W.-F. SUMOylation modulates FOXK2-mediated paclitaxel sensitivity in breast cancer cells. Oncogenesis 2018, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, R.; Wang, S.; Dong, Z. Paclitaxel: new uses for an old drug. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2014, 8, 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Marupudi, N.I.; Han, J.E.; Li, K.W.; Renard, V.M.; Tyler, B.M.; Brem, H. Paclitaxel: A review of adverse toxicities and novel delivery strategies. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2007, 6, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Kawano, I. Iwase Nab-paclitaxel for the treatment of breast cancer: Efficacy, safety, and approval. Onco Targets Ther. 2011, 4, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ma, P.; Mumper, R.J. Paclitaxel nano-delivery systems: A comprehensive review. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2013, 4, 1000164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vishnu, P.; Roy, V. Safety and efficacy of Nab-Paclitaxel in the treatment of patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Basic Clin. Res. 2011, 5, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, F.E. Paclitaxel (TAXOL®): Side effects and patient education issues. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 1993, 9, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdat, L.; Papadopoulos, K.; Lange, D.; Leuin, S.; Kaufman, E.; Donovan, D.; Frederick, D.; Bagiella, E.; Tiersten, A.; Nichols, G.; et al. Reduction of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy with glutamine. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2001, 7, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Flatters, S.J.L.; Bennett, G.J. Ethosuximide reverses paclitaxel- and vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Pain 2004, 109, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta-Chung, C.; Zyting, C.; Ling-Ming, T.; Tzeon-Jye, C.; Ruey-Kuen, H.; Wei-Shu, W.; Chueh-Chuan, Y.; Muh-Hwa, Y.; Liang-Tsai, H.; Jin-Hwang, L.; et al. Paclitaxel in a novel formulation containing less Cremophor EL as first-line therapy for advanced breast cancer: A phase II trial. Investig. New Drugs 2005, 23, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowinsky, E.K.; McGuire, W.P.; Guarnieri, T.; Fisherman, J.S.; Christian, M.C.; Donehower, R.C. Cardiac disturbances during the administration of taxol. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 1991, 9, 1704–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, M.R.; Sageman, W.S.; Scott, R.H.; Billingham, M.E.; Bowden, R.E.; Kernoff, R.S.; Snidow, G.H.; Daniels, J.R. Acute and chronic cardiovascular effects of doxorubicin in the dog: The cardiovascular pharmacology of drug-induced histamine release. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1980, 2, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, R.M.; Bouvet, M. Nanoparticle albumin-bound-paclitaxel: A limited improvement under the current therapeutic paradigm of pancreatic cancer. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2015, 16, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roy, V.; LaPlant, B.R.; Gross, G.G.; Bane, C.L.; Palmieri, F.M.; North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Phase II trial of weekly nab (nanoparticle albumin-bound)-paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel) (Abraxane) in combination with gemcitabine in patients with metastatic breast cancer (N0531). Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2009, 20, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, N.; Trieu, V.; Yao, Z.; Louie, L.; Ci, S.; Yang, A.; Tao, C.; De, T.; Beals, B.; Dykes, D.; et al. Increased antitumor activity, intratumor paclitaxel concentrations, and endothelial cell transport of cremophor-free, albumin-bound paclitaxel, ABI-007, compared with cremophor-based paclitaxel. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iglesias, J. Nab-Paclitaxel (Abraxane®): An albumin-bound cytotoxic exploiting natural delivery mechanisms into tumors. Breast Cancer Res. BCR 2009, 11, S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aapro, M.S.; Von Minckwitz, G. Molecular basis for the development of novel taxanes in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. 2008, 6, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Cao, J.; Wang, L.; Cao, E.; Wang, B.; et al. Caveolin-1 expression predicts efficacy of weekly nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic breast cancer in the phase II clinical trial. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, A.; Yuan, P.; Du, F.; Hong, R.; Ding, X.; Shi, X.; Fan, Y.; Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; Ma, F.; et al. SPARC overexpression in primary tumors correlates with disease recurrence and overall survival in patients with triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 76628–76634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Trieu, V.; Damascelli, B.; Soon-Shiong, P. SPARC expression correlates with tumor response to albumin-bound Paclitaxel in head and neck cancer patients. Transl. Oncol. 2009, 2, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blum, J.L.; Savin, M.A.; Edelman, G.; Pippen, J.E.; Robert, N.J.; Geister, B.V.; Kirby, R.L.; Clawson, A.; O’Shaughnessy, J.A. Phase II study of weekly albumin-bound Paclitaxel for patients with metastatic breast cancer heavily pretreated with Taxanes. Clin. Breast Cancer 2007, 7, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montana, M.; Ducros, C.; Verhaeghe, P.; Terme, T.; Vanelle, P.; Rathelot, P. Albumin-bound Paclitaxel: The benefit of this new formulation in the treatment of various cancers. J. Chemother. 2011, 23, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, A.; Tatibana, A.; Suzuki, N.; Hirata, M.; Oishi, Y.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Murata, Y.; Nagayama, A.; Iwata, Y.; Okamoto, Y. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of upfront weekly nanoparticle albumin-bound Paclitaxel for HER2-negative breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 6481–6488. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, M.; Chacón, J.I.; Antón, A.; Plazaola, A.; García-Martínez, E.; Seguí, M.A.; Sánchez-Rovira, P.; Palacios, J.; Calvo, L.; Esteban, C.; et al. Neoadjuvant therapy with weekly nanoparticle albumin-bound Paclitaxel for luminal early breast cancer patients: Results from the NABRAX study (GEICAM/2011-02), a multicenter, non-randomized, phase II trial, with a companion biomarker analysis. Oncologist 2017, 22, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Takashima, T.; Kawajiri, H.; Nishimori, T.; Tei, S.; Nishimura, S.; Yamagata, S.; Tokunaga, S.; Mizuyama, Y.; Sunami, T.; Tezuka, K.; et al. Safety and efficacy of low-dose nanoparticle albumin-bound Paclitaxel for HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ibrahim, N.K.; Samuels, B.; Page, R.; Doval, D.; Patel, K.M.; Rao, S.C.; Nair, M.K.; Bhar, P.; Desai, N.; Hortobagyi, G.N. Multicenter phase II trial of ABI-007, an albumin-bound paclitaxel, in women with metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 6019–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradishar, W.J.; Tjulandin, S.; Davidson, N.; Shaw, H.; Desai, N.; Bhar, P.; Hawkins, M.; O’Shaughnessy, J. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound Paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 7794–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianni, L.; Mansutti, M.; Anton, A.; Calvo, L.; Bisagni, G.; Bermejo, B.; Semiglazov, V.; Thill, M.; Chacon, J.I.; Chan, A.; et al. Comparing neoadjuvant nab-Paclitaxel vs. Paclitaxel both followed by Anthracycline regimens in women with ERBB2/HER2-negative breast cancer-the Evaluating Treatment With Neoadjuvant Abraxane (ETNA) trial: A randomized phase 3 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, Z.-Q.; Yan, K.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Yuan, T.; Wang, T.; Zheng, J. Magnetic Janus particles as a multifunctional drug delivery system for paclitaxel in efficient cancer treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 104, 110001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Hu, H.; Yan, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhou, K.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, N. Construction and in vitro and in vivo evaluation of folic acid-modified nanostructured lipid carriers loaded with paclitaxel and chlorin e6. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 569, 118595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efferth, T.; Saeed, M.E.M.; Mirghani, E.; Alim, A.; Yassin, Z.; Saeed, E.; Khalid, H.E.; Daak, S. Integration of phytochemicals and phytotherapy into cancer precision medicine. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 50284–50304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jadhav, N.R.; Nadaf, S.J.; Lohar, D.A.; Ghagare, P.S.; Powar, T.A. Phytochemicals formulated as nanoparticles: Inventions, recent patents and future prospects. Recent Pat. Drug Deliv. Formul. 2017, 11, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, T.; Xu, Z.; Sun, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Luo, C.; Wang, M. HPA aptamer functionalized paclitaxel-loaded PLGA nanoparticles for enhanced anticancer therapy through targeted effects and microenvironment modulation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 117, 109121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, C.; Mu, S.; Xue, W.; Ma, D. A chemotherapeutic self-sensibilized drug carrier delivering paclitaxel for the enhanced chemotherapy to human breast MDA-MB-231 cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 181, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, L.O.F.; Fernandes, R.S.; Castro, L.; Reis, D.; Cassali, G.D.; Evangelista, F.; Loures, C.; Sabino, A.P.; Cardoso, V.; Oliveira, M.C.; et al. Paclitaxel-loaded folate-coated pH-sensitive liposomes enhance cellular uptake and antitumor activity. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 3477–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, P.; Nagesh, P.K.B.; Hatami, E.; Wagh, S.; Dan, N.; Tripathi, M.K.; Khan, S.; Hafeez, B.B.; Meibohm, B.; Chauhan, S.C.; et al. Tannic acid-inspired paclitaxel nanoparticles for enhanced anticancer effects in breast cancer cells. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 535, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, J.-S.; Cho, C.-W. A multifunctional lipid nanoparticle for co-delivery of paclitaxel and curcumin for targeted delivery and enhanced cytotoxicity in multidrug resistant breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 30369–30382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Narayanan, S.; Mony, U.; Vijaykumar, D.K.; Koyakutty, M.; Paul-Prasanth, B.; Menon, D. Sequential release of epigallocatechin gallate and paclitaxel from PLGA-casein core/shell nanoparticles sensitizes drug-resistant breast cancer cells. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2015, 11, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabri, T.; Imran, M.; Aziz, A.; Rao, K.; Kawish, M.; Irfan, M.; Malik, M.I.; Simjee, S.U.; Arfan, M.; Shah, M.R. Design and synthesis of mixed micellar system for enhanced anticancer efficacy of Paclitaxel through its co-delivery with Naringin. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2019, 45, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, J.; Rezazadeh, M.; Mashayekhi, M.; Rostami, M.; Jahanian-Najafabadi, A. A novel mixed polymeric micelle for co-delivery of paclitaxel and retinoic acid and overcoming multidrug resistance: Synthesis, characterization, cytotoxicity, and pharmacokinetic evaluation. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2018, 44, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megerdichian, C.; Olimpiadi, Y.; Hurvitz, S.A. Nab-Paclitaxel in combination with biologically targeted agents for early and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2014, 40, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, K.L.; Goolsby, G.L.; Wahl, A.F. Cytotoxicity of the anticancer agents cisplatin and taxol during cell proliferation and the cell cycle. Int. J. Cancer 1994, 57, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kops, G.J.P.L.; Foltz, D.R.; Cleveland, D.W. Lethality to human cancer cells through massive chromosome loss by inhibition of the mitotic checkpoint. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8699–8704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vinothini, K.; Rajendran, N.K.; Ramu, A.; Elumalai, N.; Rajan, M. Folate receptor targeted delivery of paclitaxel to breast cancer cells via folic acid conjugated graphene oxide grafted methyl acrylate nanocarrier. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 110, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| BC type | BC subtype [35] | Immunohistochemical profile [36] | Cancer cell line [35] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal | Luminal A | ER+, PR+, HER2−, Ki67 low expression | BT483, CAMA1, HCC712, EFM19, HCC1428, HCC712, IBEP2, KPL1, LY2, MCF7, MDAMB134, MDAMB134VI, MDAMB175, MDAMB175VII, MDAMB415, T47D, ZR751, ZR75B |

| Luminal B (Luminal-HER2+) | ER+, HER2+, PR−, or Ki67 high expression | BSMZ, BT474, EFM192A, MDAMB330, MDAMB361, UACC812, ZR7527, ZR7530 | |

| TNBC | Basal-like | ER−, PR−, HER2− | BT20, CAL148, DU4475, EMG3, HCC1143, HCC1187, HCC1599, HCC1806, HCC1937, HCC2157, HCC3153, HCC70, HMT3522, KPL-3C, MA11, MDAMB435, MDAMB436, MDAMB468, MFM223, SUM185PE, SUM229PE |

| Claudin-low [37,38,39] | ER−, PR−, HER2−, claudin 3−, claudin 4−, claudin 7− and E-cadherin [40] | BT549, CAL120, CAL51, CAL851, HCC1395, HCC1739, HCC38, HDQ-P1, Hs578T, MDAMB157, MDAMB231, SKBR7, SUM102PT, SUM1315M02, SUM149PT, SUM159PT | |

| Non-hormonal related HER2+ | HER2 | ER−, PR−, HER2+ over-expression | AU565, HCC1008, HCC1569, HCC1954, HCC202, HCC2218, HH315, HH375, KPL-4, MDAMB453, OCUB-F, SKBR3, SKBR5, SUM190PT, SUM225CWN, UACC893 |

| Condition | Administration Schedule | Concentration Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjuvant therapy with doxorubicin (node-positive or high-risk node-negative BC) | Every 3 weeks | 175 mg/m2 IV perfusion over 3 h (4 courses) | [97] |

| Weekly | 80 mg/m2 IV perfusion over 1 h (12 courses) | [98] | |

| Failure of neoadjuvant therapy (MBC or relapse within 6 months of neoadjuvant therapy) | Every 3 weeks | 175 mg/m2 IV perfusion over 3 h | [97] |

| Untreated MBC | Every 3 weeks (max. of 8 cycles) | 200 mg/m2 IV infusion over 3 h + total dose of 480 mg/m2 doxorubicin 25 mg oral prednisone pre-treatment (12 h before treatment) 10 mg intramuscular chlorpheniramine + 300 mg intravenous cimetidine (both 30 min before PTX) | [99] |

| Neoadjuvant Drug Combination | Patient Eligibility | Concentration Range | Efficacy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTX after Doxorubicin + Cyclophosphamide | Node-positive BC with resected adenocarcinoma | 60 mg/m2 doxorubicin + 600 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide (IV infusion for 30 min to 2 h every 21 days, −4 cycles +4 cycles of 225 mg/m2 PTX (day 1 of each cycle) | PTX + doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide: ↑ DFS by 17% Acceptable toxicity | [101] |

| PTX + Bevacizumab | MBC patients with/without previous hormonal therapy or adjuvant chemotherapy | 90 mg/m2 PTX (day 1, 8, 15 every 4 weeks) + 10 mg/kg (day 1 and 15) | ↑ progression-free survival (in comparison to PTX alone) ↑ frequency of hypertension, proteinuria, headache, cerebrospinal ischemia | [102] |

| PTX + Ttrastuzumab | Breast adenocarcinoma patients (tumor no larger than 3 cm, node-negative, min. LVEF of 50%, adequate hematopoietic and liver function) | 80 mg/m2 PTX for 12 weeks + 4 mg/kg trastuzumab (day 1) → 2 mg/kg weekly (12 doses) | 98.7% disease-free survival 99.2% 3-year rate of recurrence-free survival (95%CI) 2.92% of patients reported adverse effects | [103] |

| PTX + Trastuzumab then post-operative Doxorubicin + Cyclophosphamide | Stage II or III BC patients | Dexamethasone pretreatment (20 mg) + diphenhydramine (12 and 6 h before treatment) and H2-blocker (50 mg) Trastuzumab (one-time loading dose 4 mg/kg) → weekly 2 mg/kg IV infusion for 11 weeks + 175 mg/m2 of IV PTX over 3 h (every 3 weeks, 4 cycles) 2–5 weeks post-op: doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide | 75% clinical response with 18% complete pathologic response Stage 3 tumors responded more than stage 2 tumors | [104] |

| PTX + rhG-CSF | BC patients (last radiation therapy at least 4 weeks prior to chemotherapy) | 250 mg/m2 of IV PTX (for 24 h every 21 days, dose adjusted to granulocyte and platelet nadirs) 5 μg/kg/d of rhG-CSF (subcutaneously on day 3 through 10/cycle) | CR—12% of patients PR—50% of patients Inverse correlation between response and median age of patients Minimal toxic effects | [105] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abu Samaan, T.M.; Samec, M.; Liskova, A.; Kubatka, P.; Büsselberg, D. Paclitaxel’s Mechanistic and Clinical Effects on Breast Cancer. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 789. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9120789

Abu Samaan TM, Samec M, Liskova A, Kubatka P, Büsselberg D. Paclitaxel’s Mechanistic and Clinical Effects on Breast Cancer. Biomolecules. 2019; 9(12):789. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9120789

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbu Samaan, Tala M., Marek Samec, Alena Liskova, Peter Kubatka, and Dietrich Büsselberg. 2019. "Paclitaxel’s Mechanistic and Clinical Effects on Breast Cancer" Biomolecules 9, no. 12: 789. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9120789

APA StyleAbu Samaan, T. M., Samec, M., Liskova, A., Kubatka, P., & Büsselberg, D. (2019). Paclitaxel’s Mechanistic and Clinical Effects on Breast Cancer. Biomolecules, 9(12), 789. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9120789