Advancing Revolving Funds for the Sustainable Development of Rural Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Specification

1.2. Aim of Research/Research Questions

- What are the particular challenges for the ARF in promoting the sustainable development of rural regions?

- What are the essential features and mechanisms of the ARF?

- What are the most important design aspects for the ARF in rural regions?

- What are the key input parameters for the financial modelling of the ARF for rural regions?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Theory of Spatial Organisms

2.2. New Institutional Economics, Barriers and Incentive Schemes

2.3. Existing Fund Models

- The mobilisation of additional resources and investments (public and private funds, leverage effect);

- Risk diversification by spreading the fund resources over several projects;

- Increased pressure for efficiency due to repayment obligation;

- Sustainable fund returns allow continuous investments;

- Periodic review of projects (target/actual checks);

- Use of skills from public and private shareholders, including the financial sector.

- Lower appeal due to persistently low interest rates on the capital markets;

- The easier management of existing subsidy-based programs for municipalities;

- The need to implement new administrative structures and knowledge of urban development funds on the public administration side;

- A lack of compatibility between urban development support and funds;

- A lack of economies of scale due to rather small project sizes;

- High administrative and accounting costs (ERDF funds);

- The difficult pre-financing of ERDF resources (reimbursement principle) in tight budget situations; this may partially be offset by interest income from the fund.

- Independent fund management made it possible to better meet local needs.

- The establishment of a holding fund made it possible to set up new funds where necessary and to integrate them into different political fields of action.

- Small capital volumes mitigate reservations regarding the decision between subsidy or fund.

- The opportunity to re-use the fund capital without European restrictions is recognised.

- The integration of private actors proved to be difficult, although JESSICA called for it: the governance structure should be designed to be easily manageable so that private capital is combined with fund resources only at the project level.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Initial Research Phase

- The investment needs of the ARF;

- The organisational structures of the ARF;

- Financing the ARF.

3.2. Research Approach

3.3. Background

3.3.1. Heterogeneity of Rural Regions

3.3.2. Building Stock

3.3.3. Building Owners

3.3.4. Residential Markets

4. Results

4.1. Postulated Features of ARF Mechanism

- The reduction of land use in rural regions, especially for residential development under the conditions of demographic change;

- Strengthening the development of the centre and the sustainable preservation of the historical building fabric; the revitalisation of the centre through mixed and new use;

- The adaptation of the settlement area to demographic development with new forms of housing and land layouts;

- The more efficient use of funding;

- The strengthening of regional cooperation and a responsible society;

- Accounting for interdependencies and synergies of spatial organisms/social systems.

4.2. Essential Mechanisms of ARF

- Mode A: The ARF buys and refurbishes a property—for example, by order of a municipality. Therefore, the ARF itself acts as a developer and resells the property. In this case, one classic and one more complex procedure can be distinguished. The regular way is sale to the ARF and resale by the ARF after refurbishment to a new owner. Another way could be that the seller keeps shares, resulting in an owner community with an ARF or, later, even in a cooperative with new owners or ARFs. As long as the ARF holds the shares it needs to be capable of acting in and maintaining the interests of the regional settlement development, this is appropriate. The sellers can reinvest their income in other ARF projects and reduce their cluster risk by the distribution of their investments. Simultaneously, the ARF offers a possibility to invest in the regional housing market and can strengthen identification with the region as a spatial organism/social system. In both cases of this mode, it must be ensured that land transfer tax is charged only once to avoid an unwanted barrier. If necessary, contractual arrangements must be adjusted in comparison to redevelopment agencies.

- Mode B: No urban development intervention/activation is needed, and the ARF acts as a creditor. In contrast to regular credit programs, the ARF can additionally assume responsibility for a refurbishment, if the financial burdens for owners are too high or owners are not rated creditworthy (e.g., due to the age of the owner). The owner repays the loan within a fixed period. The ARF secures the credit and its interest in sustainable settlement development in the region through mortgages. Problems arising through foreclosures can be avoided, and the ARF regains ownership for a fixed price.

- Mode C: The ARF acts as an active mediator—regarding usufruct right. Owners contribute their land to the ARF and thus support a sustainable densification of settlement structures [37]. The ARF promotes the vacant sites, qualifies them and reduces or eliminates encumbrances. If needed, the ARF supports future users with expert advice and know-how.

4.3. Design Aspects of ARF

4.3.1. Governance

4.3.2. Eligibility

4.3.3. Communication and Incentive Schemes

4.4. Input Parameters and Financial Modeling of Regional Funds

4.4.1. Overhead and Other Costs

4.4.2. Financing Sources and Fund Volume

4.4.3. Legal Parameters

4.4.4. Revolving Part, Interest Rate, Repayment Periods and Fund Term

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings and Implications

- The ARF is to have a regional focus. This is a novelty for spatial development but is necessary, especially for intelligent rural regions. For example, the housing needs in rural regions are usually not locally but regionally oriented [40]. The regional orientation also helps to avoid intraregional competition for those willing to build. In order to be able to deal with individual factors, which can vary from region to region, the ARF should also not have a supra-regional orientation. Regional funds can be governed by a holding fund.

- Another novelty is that the ARF no longer has a sectoral approach. It can invest in buildings of any use type as well as in surroundings and infrastructure.

- The ARF combines public and private capital from owners and other, in particular, locally rooted, investors and stakeholders.

- The revolving principle offers the possibility of empowering settlement development through refluxes of funds with a permanent—or at least long-lasting—instrument that sustainably increases communities’ scope for action.

- The ARF strategy or basis for action should not, as in the past, be based on defined measures or bundles of measures in a firmly defined area. Rather, regional funds could be established in all possible regions, each with their own characteristics. Furthermore, it is not subject to a specific funding program or funding logic. This differentiates the concept from common action-based funding. Previous approaches, at least in Europe, were always tailored to model regions. The ARF is designed as a general model.

- The ARF enables the value preservation of existing building substance and promotes building culture as well as energetic refurbishments. It contributes to affordable housing in rural regions.

- The ARF strengthens regional economies and crafts. The approach and the supporting structures strengthen the municipalities and regional cooperation, since the municipalities are permanently involved not only in setting and developing priorities but also in applying and implementing the instrument.

5.2. Need for Ongoing Research

- Is a minimum size for regions required to introduce the ARF?

- What is the distribution of tasks, and which decision-making and consultative bodies within the supporting structure(s) are necessary?

- What professional support for the technical/organisational processing of the fund may be necessary?

- How should buildings and land in regional funds be managed?

- Which property types should the fund primarily address (differentiation from the free property market)?

- To what extent are temporary interim uses possible for buildings and land in regional funds?

- How can processes and modes of operation for the ARF be meaningfully operationalised?

- What are the potential economic, social and ecological impacts of the ARF in rural regions?

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country/City | Targets and Measures | Level of Funding | Financing Source | Allocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands/ Den Haag (FED; ED) | (a) Promotion of energy efficiency (b) Urban development projects | (a) EUR 4 m (b) EUR 4 m | - | Credits below market level |

| Portugal/Porto (REENERGI.CHP) | Promotion of urban (and energy) renovation in the historic city centre | EUR 40 m | - | Mix of credits and grants |

| UK/Manchester (Evergreen Fund) | Revitalisation of properties and areas for commercial development | GBP 60 m | - | Credits below and at market level |

| Poland/Posen (Wielkopolska Fund) | Real estate development and refurbishment in the commercial and office space segment, depending on social impact | EUR 66 m | EUR 51 m ERDF resources, EUR 15 m public co-financing | Credits below the market level determined according to social criteria |

| Latvia/Riga (state-owned fund) | Improving energy efficiency in buildings | EUR 40 m | EUR 30 m ERDF resources, EUR 4 m from City of Riga | Credits below the market level, discounts if targets are achieved, supplemented by grants |

| Spain/Sevilla (AC JESSICA) | Urban development projects | EUR 40 m | ERDF and funding of the BBVA (Spanish credit institution) | Credits below market level and equity participation |

Appendix B

- Gerd BauerDirector of Housing Promotion, Thüringer Aufbaubank, Erfurt in Thuringia

- Frank BaumgartenManaging Director, Stiftung Landleben, Kirchheilingen in Thuringia

- Joachim BleeckPresident, State Association Thuringia House, Dwelling and Grounds Owners, Rudolstadt in Thuringia

- Petra EndersCounty Commissioner, Ilm-Kreis, Arnstadt in Thuringia

- Andreas JacobManaging Director, FIRU mbH, Kaiserslautern in Rhineland-Palatinate

- Thomas KlepelHead of Nature Park Dübener Heide, Bad Düben in Saxony

- Andre KnappDepartment Head, Rhön-Rennsteig-Sparkasse, Meiningen in Thuringia

- Ulrich KurtzMayor, Steinach, Steinach in Thuringia

- Florian LangguthManager, SPRINT—wissenschaftliche Politikberatung, Darmstadt in Hesse

- Christian LöffelholzThuringia Ministry for Infrastructure and Agriculture (TMIL), Erfurt in Thuringia

- Rolf Novy-HuyHead of Stiftung trias, Hattingen in North Rhine-Westphalia

- Dr. Annelie ReiterAuthority for Agriculture and the Reorganisation of Land (ALF), Meiningen in Thuringia

- Prof. Stefan RettichProfessor at School of Architecture/University Bremen, Member of the Advisory Council IBA Thuringia

- Ulla SchauberManaging Director, Stadtstrategen, Weimar in Thuringia

- Johann ScheiblhuberBranch Manager, Deutsche Kreditbank, Erfurt in Thuringia

- Udo SchillingVice County Commissioner, Wartburgkreis, Bad Salzungen in Thuringia

- Prof. Martin zur NeddenHead of Deutsches Insititut für Urbanistik (DIFU), Berlin

References

- Leimgruber, W.; Chang, C.D. Rural Areas Between Regional Needs and Global Challenges. In Transformation in Rural Space, 4th ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.; He, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zeng, S.; Xiao, L. Optimizing the spatial organization of rural settlements based on life quality. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larina, T.; Kibataeva, A. Housing market in rural areas of Russia: Developmental factors and problems of study. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 341, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, A. The Drivers of Supply and Demand in Australia’s Rural and Regional Centres. 2011. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/30681445.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Kötter, T.; Linke, H.J. Vom Wachstum zur Schrumpfung—Ein Beitrag zum neuen Planungsverständnis für Städte und Dörfer im demografischen Wandel. Zfv Z. Geodäsie Geoinf. Landmanag. 2013, 2013, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, A. Stadtentwicklungsfonds im Rahmen der JESSICA-Initiative; BMVBS-Online-Publikation. 2011. Available online: https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/veroeffentlichungen/ministerien/bmvbs/bmvbs-online/2011/DL_ON142011.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Siebert, R. Social Change and Trends in Rural Areas. In Agricultural Transformation and Land Use in Central and Eastern Europe; Goetz, S.J., Jaksch, T., Eds.; Routledge: Milton, UK, 2018; pp. 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mensing, K. Revitalisierung des Immobilienbestandes in Klein- und Mittelstädten durch einen revolvierenden Stadtentwicklungsfonds. In Stadtentwicklungsfonds. Ein Neues Instrument zur Unterstützung Nachhaltiger Stadtentwicklung? Nischwitz, G., Andreas, V., Eds.; Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung: Hannover, Germany, 2019; pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Schleiter, L.-W. Historische, Gesellschaftliche und Ökonomische Grundlagen der Immobilien-Projektentwicklung oder Staats-, Stadt- und Immobilienentwicklung; Müller: Köln, Germany, 2000; pp. 329–330. ISBN 978-3932687549. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Social Systems; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0804726252. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, R. Essays on New Institutional Economics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-3319141541. [Google Scholar]

- Ménard, C.; Shirley, M.M. Handbook of New Institutional Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 21–69. ISBN 978-3540776604. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, S. Institutional Economics. An Introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 5–37. ISBN 978-1108473248. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge. Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness; Yale Univ. Press: New Haven, Connecticut, 2008; pp. 1–81. ISBN 978-0143115267. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2012; pp. 109–199. ISBN 978-0141033570. [Google Scholar]

- Achtnicht, M.; Madlener, R. Factors Influencing German House Owners’ Preferences on Energy Retrofits; ZEW, Zentrum für Europ. Wirtschaftsforschung: Mannheim, Germany, 2012; pp. 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Abreu, M.I.; Oliveira, R.; Lopes, J. Attitudes and Practices of Homeowners in the Decision-making Process for Building Energy Renovation. Procedia Eng. 2017, 172, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieß, I. Handlungsmotive, -Hemmnisse und Zielgruppen für eine Energetische Gebäudesanierung: Ergebnisse einer standardisierten Befragung von Eigenheimsanierern. Available online: https://edocs.tib.eu/files/e01fb10/625755685.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Klöckner, C.A.; Nayum, A. Specific Barriers and Drivers in Different Stages of Decision-Making about Energy Efficiency Upgrades in Private Homes. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renz, I.; Hacke, U. The multi-dimensionality of decisions on energetic refurbishment: Results of a qualitative study covering different types of property owners. In Proceedings of the EECE 2017 Summer Study on Energy Efficiency, Presqu’île de Giens, France, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 2043–2052. [Google Scholar]

- Beillan, V. Barriers and drivers to energy-efficient renovation in the residential sector. Empirical findings from five European countries. In Energy Efficiency First: The Foundation of a Low-Carbon Society: ECEEE 2011 Summer Study, Proceedings of the Conference Proceedings, Belambra Presqu’île de Giens, France, 6–11 June 2011; Lindström, T., Ed.; ECEEE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011; pp. 1083–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Stieß, I.; Dunkelberg, E. Objectives, barriers and occasions for energy efficient refurbishment by private homeowners. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nischwitz, G.; Andreas, V. Stadtentwicklungsfonds. Ein neues Instrument zur Unterstützung nachhaltiger Stadtentwicklung? Einführung. In Stadtentwicklungsfonds. Ein Neues Instrument zur Unterstützung Nachhaltiger Stadtentwicklung? Nischwitz, G., Andreas, V., Eds.; Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung: Hannover, Germany, 2019; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bötel, A. Evaluation RWB-EFRE 2007–2013. In Thematische Studie zur Konzeption Neuer Finanzierungsinstrumente; Rambøll Management Consulting GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, A. Stadtentwicklungsfonds in Deutschland; ExWoSt-Informationen; BBSR: Bonn, Germany, 2011; pp. 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- IPU. Revolvierender Siedlungsfonds. In Dokumentation IBA Werkstatt Revolvierender Siedlungsfonds; Internationale Bauausstellung Thüringen: Apolda, Germany, 2016; pp. 8–26. [Google Scholar]

- Franzen, N.; Hahne, U.; Hartz, A.; Kühne, O.; Schafranski, F.; Spellerberg, A.; Zeck, H. Herausforderung Vielfalt—Ländliche Räume im Struktur- und Politikwandel; Akad. Für Raumforschung und Landesplanung: Hannover, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Urban-Rural Typology, by NUTS 3. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/RCI/#?vis=urbanrural.urb_typology&lang=en (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Destatis. Census. 2011. Available online: https://ergebnisse.zensus2011.de/?locale=en (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Infoportal Zukunft.Land. Anteil Ein- und Zweifamilienhäuser. Available online: www.landatlas.de/wohnen/ein_zwei.html (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Infoportal Zukunft.Land. Anteil Wohnungsleerstand. Available online: www.landatlas.de/wohnen/leerstand.html (accessed on 1 September 2020).

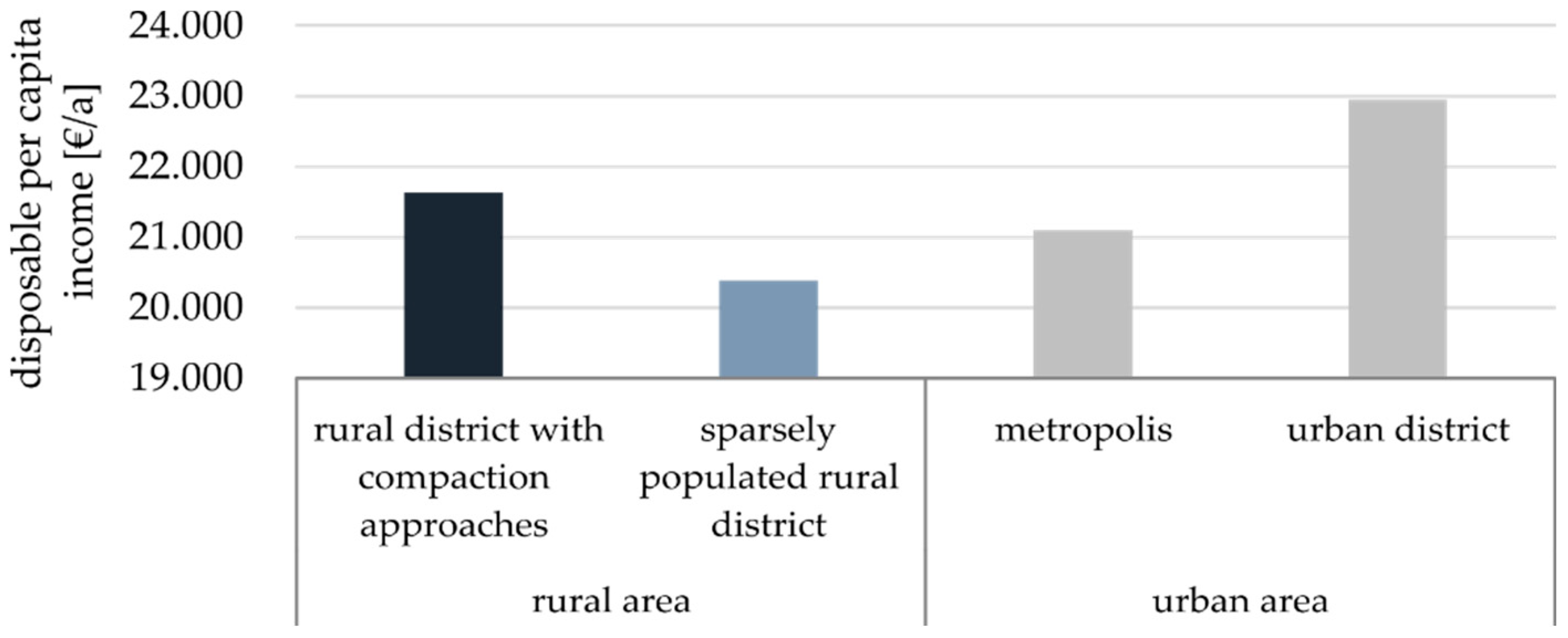

- Maretzke, S. Regionale Disparitäten des Einkommens in Deutschland. In Armut im Ländlichen Raum? Analysen und Initiativen zu einem Tabu-Thema; Hanns-Seidel-Stiftung: München, Germany, 2015; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg. Verfügbares Einkommen Privater Haushalte. Available online: https://www.statistik-bw.de/VGRdL/tbls/R0B0.jsp?tbl=R2B3 (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Bouzarovski, S.; Petrova, S. A global perspective on domestic energy deprivation: Overcoming the energy poverty–fuel poverty binary. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 10, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohr-Zänker, R. Wohnungsmärkte im Wandel; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Hannover, Germany, 2014; pp. 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Westermeier, C.; Grabka, M.M. Zunehmende Polarisierung der Immobilienpreise in Deutschland bis 2030; DIW-Wochenbericht: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 451–459. [Google Scholar]

- Patti, D.; Polyak, L. Funding the Cooperative City. Community Finance and the Economy of Civic Spaces. 2017. Available online: https://www.stiftung-trias.de/fileadmin/media/publikationen/2017_trias_Funding-the-Cooperative-City.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Roberts, B.H. Rural Urbanization and the Development of Small and Intermediate Towns. Reg. Dev. Dialogue 2014, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Crow, H. Factors Influencing Rural Migration Decisions in Scotland: An Analysis of the Evidence; Scottish Government Social Research: Edinburgh, UK, 2010; pp. 18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, S. Housing market dynamics in rural and regional Australia. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual Pacific Rim Real Estate Society Conference, Adelaide, Australia, 15–18 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leßmann, C.; Schirwitz, B. Revolvierende Fonds als Instrument zur Neuausrichtung der Förderpolitik. In ifo Dresden Berichtet; ifo Dresden: Dresden, Germany, 2008; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

| Barriers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Socio-Economic | Constructional | Informational |

| Insufficient liquidity and credit rating | Life situation (age, income, etc.) | Protection of historical monuments | Negative reports |

| Investor-user dilemma | Reservations concerning preparatory work | Concern about structural damage | Lack of technological/economical knowledge |

| Long payback period | Preference for visible values | Planning and implementation too difficult | Adverse third-party influence |

| Complex grant application | Practiced habits | Fear of aesthetic limitations | Insufficient quality of advice |

| Emotional aspects/biases (e.g., concern/fear, affect, anchoring, lock-in, and sunk costs fallacy) | |||

| Lack of information/lack of knowledge/information asymmetries | |||

| Disposable per Capita Income | Mortgage Lending Rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1%/a | 3%/a | 5%/a | 12%/a | ||

| Borrowing Potential | 20,000 €/a | 94,345 € | 78,620 € | 66,558 € | 41,365 € |

| 21,000 €/a | 96,703 € | 80,585 € | 68,222 € | 42,399 € | |

| 21,500 €/a | 99,062 € | 82,551 € | 69,886 € | 43,434 € | |

| 22,000 €/a | 101,421 € | 84,516 € | 71,550 € | 44,468 € | |

| 22,500 €/a | 103,779 € | 86,482 € | 73,214 € | 45,502 € | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wasser, N.-M.; Ruhstorfer, P.; Kurzrock, B.-M. Advancing Revolving Funds for the Sustainable Development of Rural Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8455. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208455

Wasser N-M, Ruhstorfer P, Kurzrock B-M. Advancing Revolving Funds for the Sustainable Development of Rural Regions. Sustainability. 2020; 12(20):8455. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208455

Chicago/Turabian StyleWasser, Nils-Magnus, Philipp Ruhstorfer, and Björn-Martin Kurzrock. 2020. "Advancing Revolving Funds for the Sustainable Development of Rural Regions" Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8455. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208455

APA StyleWasser, N.-M., Ruhstorfer, P., & Kurzrock, B.-M. (2020). Advancing Revolving Funds for the Sustainable Development of Rural Regions. Sustainability, 12(20), 8455. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208455