Herbal Medicine for Pain Management: Efficacy and Drug Interactions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

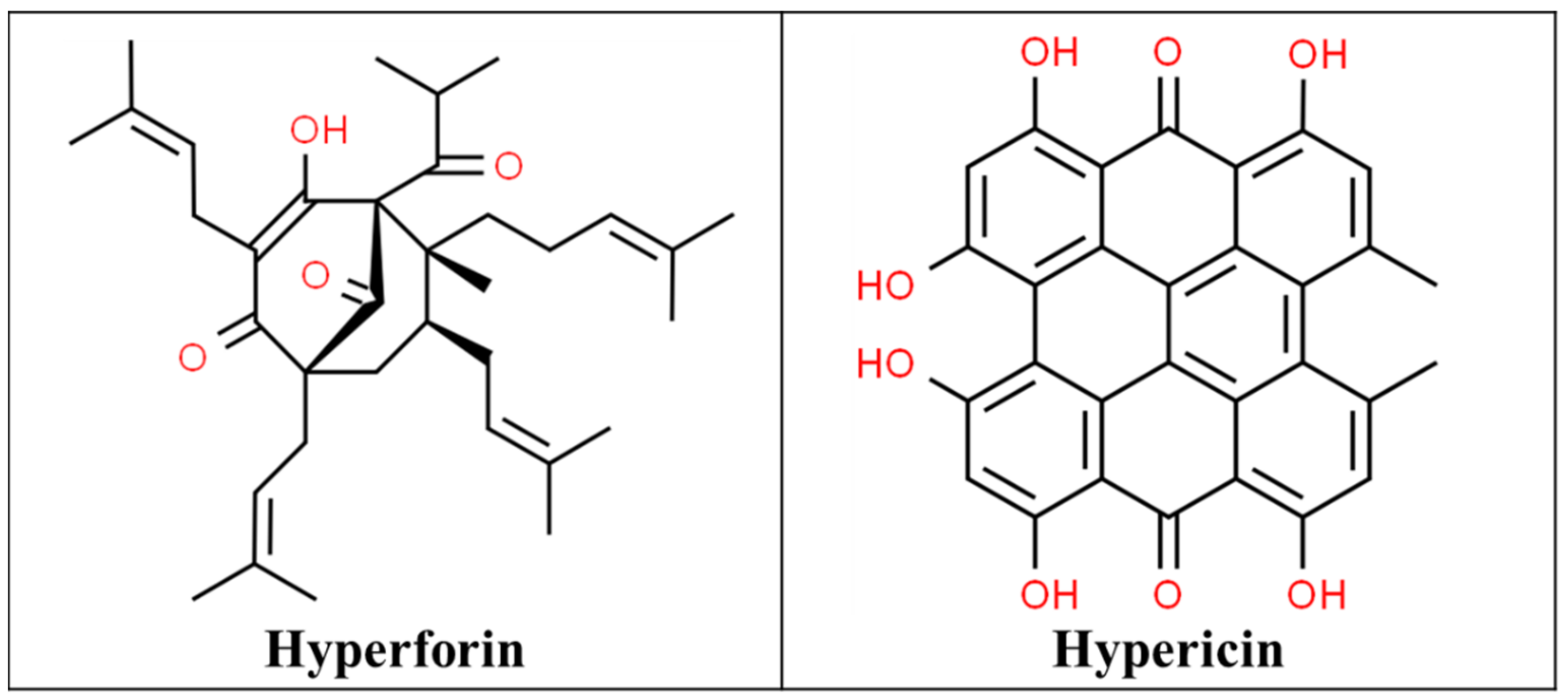

3.1. St John’s Wort

3.2. Ginger

3.3. Turmeric

3.4. Omega-3 Fatty Acids

3.5. Capsaicin

3.6. Thunder God Vine

3.7. Butterbur

3.8. Feverfew

3.9. Willow Bark

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eisenberg, D.M.; Davis, R.B.; Ettner, S.L.; Appel, S.; Wilkey, S.; van Rompay, M.; Kessler, R.C. Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990–1997: Results of a Follow-up National Survey. JAMA 1998, 280, 1569–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gentz, B.A. Alternative Therapies for the Management of Pain in Labor and Delivery. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 44, 704–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, E.; Willoughby, M.; Weihmayr, T.H. Nine Possible Reasons for Choosing Complementary Medicine. Perfusion 1995, 11, 356–359. [Google Scholar]

- NCCIH. Nonpharmacologic Management of Pain; NCCIH: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nahin, R.L.; Barnes, P.M.; Stussman, B.J.; Bloom, B. Costs of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (Cam) and Frequency of Visits to Cam Practitioners: United States, 2007. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2009, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, D.K.; Ernst, E. Complementary and Alternative Approaches to the Treatment of Persistent Musculoskeletal Pain. Clin. J. Pain 2004, 20, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hexaresearch. Global Herbal Medicine Market Size, Value, 2014–2024; Hexaresearch: Pune, MH, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, J.K.; Mihaliak, K.; Kroenke, K.; Bradley, J.; Tierney, W.M.; Weinberger, M. Use of Complementary Therapies for Arthritis among Patients of Rheumatologists. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 131, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budavari, S. The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals, 11th ed.; Merck: Rahway, NJ, USA, 1989; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, P.J.; Kam, P.C. The Peri-Operative Implications of Herbal Medicines. Anaesthesia 2002, 57, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetrow, C.W.; Avila, J.R. The Complete Guide to Herbal Medicines; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- CSID:16736597. Hyperforin. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.16736597.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- CSID:4444511. Hypericin. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.4444511.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Gordon, J.B. Ssris and St.John’s Wort: Possible Toxicity? Am. Fam. Phys. 1998, 57, 950. [Google Scholar]

- Gillman, P.K. Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors, Opioid Analgesics and Serotonin Toxicity. Br. J. Anaesth 2005, 95, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vasilchenko, E.A. Analgesic Action of Flavonoids of Rhododendron Luteum Sweet, Hypericum Perforatum L.; Lespedeza Bicolor Turcz, and L. Hedysaroids (Pall.). Kitag Rastit. Resur. 1986, 22, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, J.H.; Hudgins, J.C.; Paice, J.A. Use of Herbal Therapies to Relieve Pain: A Review of Efficacy and Adverse Effects. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2005, 6, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc. Duragesic (Fentanyl) Prescribing Information; Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc.: Titusville, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoz Canada Inc. Codeine Phosphate Injection [Product Monograph]; Sandoz Canada Inc.: Boucherville, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zogenix Inc. Zohydro Er (Hydrocodone Bitartrate) [Prescribing Information]; Zogenix Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen, T.H.; Hagelberg, N.M.; Saari, T.I.; Neuvonen, M.; Laine, K.; Neuvonen, P.J.; Olkkola, K.T. St John’s Wort Greatly Reduces the Concentrations of Oral Oxycodone. Eur. J. Pain 2010, 14, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, C.; Chao, W.; Costa, D.; Rusie-Seamon, E.; Weissner, W.; Woods, J. Clinical Evidence of Herb-Drug Interactions: A Systematic Review by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. Curr. Drug. Metab 2008, 9, 1063–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loughren, M.J.; Kharasch, E.D.; Kelton-Rehkopf, M.C.; Syrjala, K.L.; Shen, D.D. Influence of St. John’s Wort on Intravenous Fentanyl Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Clinical Effects: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesthesiology 2020, 132, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galeotti, N.; Farzad, M.; Bianchi, E.; Ghelardini, C. Pkc-Mediated Potentiation of Morphine Analgesia by St. John’s Wort in Rodents and Humans. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 124, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltoniemi, M.A.; Saari, T.I.; Hagelberg, N.M.; Laine, K.; Neuvonen, P.J.; Olkkola, K.T. St John’s Wort Greatly Decreases the Plasma Concentrations of Oral S-Ketamine. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 26, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clewell, A.; Barnes, M.; Endres, J.R.; Ahmed, M.; Ghambeer, D.K. Efficacy and Tolerability Assessment of a Topical Formulation Containing Copper Sulfate and Hypericum Perforatum on Patients with Herpes Skin Lesions: A Comparative, Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2012, 11, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sindrup, S.H.; Madsen, C.; Bach, F.W.; Gram, L.F.; Jensen, T.S. St. John’s Wort Has No Effect on Pain in Polyneuropathy. Pain 2001, 91, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeotti, N. Hypericum Perforatum (St John’s Wort) Beyond Depression: A Therapeutic Perspective for Pain Conditions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 200, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, B.; Kiefer, D.; Rabago, D. Assessing the Risks and Benefits of Herbal Medicine: An Overview of Scientific Evidence. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 1999, 5, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Langner, E.; Greifenberg, S.; Gruenwald, J. Ginger: History and Use. Adv. Ther. 1998, 15, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fischer-Rasmussen, W.; Kjaer, S.K.; Dahl, C.; Asping, U. Ginger Treatment of Hyperemesis Gravidarum. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1991, 38, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, E.; Pittler, M.H. Efficacy of Ginger for Nausea and Vomiting: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Br. J. Anaesth. 2000, 84, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, K.L.; Ammit, A.J.; Tran, V.H.; Duke, C.C.; Roufogalis, B.D. Gingerols and Related Analogues Inhibit Arachidonic Acid-Induced Human Platelet Serotonin Release and Aggregation. Thromb. Res. 2001, 103, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, K.L.; Lutz, R.B. Alternative therapies: Ginger. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2000, 57, 945–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.D.; Oconnor, P.J. Acute Effects of Dietary Ginger on Quadriceps Muscle Pain During Moderate-Intensity Cycling Exercise. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2008, 18, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.D.; O’Connor, P.J. Acute Effects of Dietary Ginger on Muscle Pain Induced by Eccentric Exercise. Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, 1620–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.D.; Herring, M.P.; Hurley, D.J.; O’Connor, P.J. Ginger (Zingiber Officinale) Reduces Muscle Pain Caused by Eccentric Exercise. J. Pain 2010, 11, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, R.; Posadzki, P.; Watson, L.K.; Ernst, E. The Use of Ginger (Zingiber Officinale) for the Treatment of Pain: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Pain Med. 2011, 12, 1808–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- CSID:391126. (+)-[6]-Gingerol. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.391126.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Backon, J. Ginger as an Antiemetic: Possible Side Effects Due to Its Thromboxane Synthetase Activity. Anaesthesia 1991, 46, 705–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, K.C. Aqueous Extracts of Onion, Garlic and Ginger Inhibit Platelet Aggregation and Alter Arachidonic Acid Metabolism. Biomed. Biochim. Acta 1984, 43, S335–S346. [Google Scholar]

- Backon, J. Ginger: Inhibition of Thromboxane Synthetase and Stimulation of Prostacyclin: Relevance for Medicine and Psychiatry. Med. Hypotheses 1986, 20, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaes, L.P.; Chyka, P.A. Interactions of Warfarin with Garlic, Ginger, Ginkgo, or Ginseng: Nature of the Evidence. Ann. Pharm. 2000, 34, 1478–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Montserrat-de la Paz, S.; Garcia-Gimenez, M.D.; Quilez, A.M.; de la Puerta, R.; Fernandez-Arche, A. Ginger Rhizome Enhances the Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Nociceptive Effects of Paracetamol in an Experimental Mouse Model of Fibromyalgia. Inflammopharmacology 2018, 26, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepahvand, R.; Esmaeili-Mahani, S.; Arzi, A.; Rasoulian, B.; Abbasnejad, M. Ginger (Zingiber Officinale Roscoe) Elicits Antinociceptive Properties and Potentiates Morphine-Induced Analgesia in the Rat Radiant Heat Tail-Flick Test. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 1397–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.B.; dos Santos Rodrigues, A.M.; Fernandes Rodrigues, D.; dos Santos, L.C.; Teixeira, A.L.; Versiani Matos Fereira, A. Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial of Ginger ( Zingiber Officinale Rosc.) Addition in Migraine Acute Treatment. Cephalalgia 2019, 39, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondanelli, M.; Riva, A.; Morazzoni, P.; Allegrini, P.; Faliva, M.A.; Naso, M.; Miccono, A.; Peroni, G.; Agosti, I.D.; Perna, S. The Effect and Safety of Highly Standardized Ginger (Zingiber Officinale) and Echinacea (Echinacea Angustifolia) Extract Supplementation on Inflammation and Chronic Pain in Nsaids Poor Responders. A Pilot Study in Subjects with Knee Arthrosis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cady, R.K.; Schreiber, C.P.; Beach, M.E.; Hart, C.C. Gelstat Migraine (Sublingually Administered Feverfew and Ginger Compound) for Acute Treatment of Migraine When Administered During the Mild Pain Phase. Med. Sci. Monit. 2005, 11, PI65–PI69. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, R.D.; Marcussen, K.C. Effects of a Ginger Extract on Knee Pain in Patients with Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44, 2531–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliddal, H.; Rosetzsky, A.; Schlichting, P.; Weidner, M.S.; Andersen, L.A.; Ibfelt, H.H.; Christensen, K.; Jensen, O.N.; Barslev, J. A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-over Study of Ginger Extracts and Ibuprofen in Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2000, 8, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.X.; Barrett, B.; Kwekkeboom, K.L. Efficacy of Oral Ginger (Zingiber Officinale) for Dysmenorrhea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid. Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016, 2016, 6295737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, P.B. Ginger (Zingiber Officinale) as an Analgesic and Ergogenic Aid in Sport: A Systemic Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2980–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, M.J.; Kumar, S. The Clinical Effectiveness of Ginger (Zingiber Officinale) in Adults with Osteoarthritis. JBI Libr. Syst. Rev. 2008, 6, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahbaie, P.; Sun, Y.; Liang, D.Y.; Shi, X.Y.; Clark, J.D. Curcumin Treatment Attenuates Pain and Enhances Functional Recovery after Incision. Anesth. Analg. 2014, 118, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Shin, T.J.; Choi, J.M.; Seo, K.S.; Kim, H.J.; Yoon, T.G.; Lee, Y.S.; Han, H.; Chung, H.J.; Oh, Y.; et al. Antinociceptive Curcuminoid, Kms4034, Effects on Inflammatory and Neuropathic Pain Likely Via Modulating Trpv1 in Mice. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 111, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bright, J.J. Curcumin and Autoimmune Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007, 595, 425–451. [Google Scholar]

- Kalluru, H.; Kondaveeti, S.S.; Telapolu, S.; Kalachaveedu, M. Turmeric Supplementation Improves the Quality of Life and Hematological Parameters in Breast Cancer Patients on Paclitaxel Chemotherapy: A Case Series. Complement Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 41, 101247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CSID:839564. Curcumin. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.839564.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Asher, G.N.; Spelman, K. Clinical Utility of Curcumin Extract. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2013, 19, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Keihanian, F.; Saeidinia, A.; Bagheri, R.K.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. Curcumin, Hemostasis, Thrombosis, and Coagulation. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 4497–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leksiri, S.; Hasriadi, P.; Wasana, W.D.; Vajragupta, O.; Rojsitthisak, P.; Towiwat, P. Co-Administration of Pregabalin and Curcumin Synergistically Decreases Pain-Like Behaviors in Acute Nociceptive Pain Murine Models. Molecules 2020, 25, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, E.-J.; Efferth, T.; Panossian, A. Curcumin Downregulates Expression of Opioid-Related Nociceptin Receptor Gene (Oprl1) in Isolated Neuroglia Cells. Phytomedicine 2018, 50, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paz-Campos, M.A.; Ortiz, M.I.; Pina, A.E.C.; Zazueta-Beltran, L.; Castaneda-Hernandez, G. Synergistic Effect of the Interaction between Curcumin and Diclofenac on the Formalin Test in Rats. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, N.; Joshi, R.; Hota, D.; Chakrabarti, A. Evaluation of Antihyperalgesic Effect of Curcumin on Formalin-Induced Orofacial Pain in Rat. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haroyan, A.; Mukuchyan, V.; Mkrtchyan, N.; Minasyan, N.; Gasparyan, S.; Sargsyan, A.; Narimanyan, M.; Hovhannisyan, A. Efficacy and Safety of Curcumin and Its Combination with Boswellic Acid in Osteoarthritis: A Comparative, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Appelboom, T.; Maes, N.; Albert, A. A New Curcuma Extract (Flexofytol(R)) in Osteoarthritis: Results from a Belgian Real-Life Experience. Open Rheumatol. J. 2014, 8, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke-Okoro, U.J.; Raffa, R.B.; Pergolizzi, J.V., Jr.; Breve, F.; Taylor, R., Jr. Nema Research Group. Curcumin in Turmeric: Basic and Clinical Evidence for a Potential Role in Analgesia. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2018, 43, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gaffey, A.; Slater, H.; Porritt, K.; Campbell, J.M. The Effects of Curcuminoids on Musculoskeletal Pain: A Systematic Review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement Rep. 2017, 15, 486–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, K.; Sahy, W.; Beckett, R.D. Efficacy of Curcuma for Treatment of Osteoarthritis. J. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2017, 22, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daily, J.W.; Yang, M.; Park, S. Efficacy of Turmeric Extracts and Curcumin for Alleviating the Symptoms of Joint Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. J. Med. Food 2016, 19, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tokuyama, S.; Nakamoto, K. Unsaturated Fatty Acids and Pain. Biol. Pharm. Bull 2011, 34, 1174–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun-Edelstein, C.; Mauskop, A. Foods and Supplements in the Management of Migraine Headaches. Clin. J. Pain 2009, 25, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- GlaxoSmithKline. Lovaza (Omega-3-Acid Ethyl Esters) [Prescribing Information]; GlaxoSmithKline: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, M.K.; Ashmore, J.H.; Harris, K.A.; Vogelaar, J.L.; Pottala, J.V.; Sprehe, M.; Harris, W.S. Effects of Omega-3 Acid Ethyl Esters and Aspirin, Alone and in Combination, on Platelet Function in Healthy Subjects. Thromb. Haemost 2008, 100, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodnight, S.H., Jr.; Harris, W.S.; Connor, W.E. The Effects of Dietary Omega 3 Fatty Acids on Platelet Composition and Function in Man: A Prospective, Controlled Study. Blood 1981, 58, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CSID:393682. Eicosapentanoic Acid. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.393682.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- CSID:393183. Docosahexaenoic Acid. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.393183.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Escudero, G.E.; Romanuk, C.B.; Toledo, M.E.; Olivera, M.E.; Manzo, R.H.; Laino, C.H. Analgesia Enhancement and Prevention of Tolerance to Morphine: Beneficial Effects of Combined Therapy with Omega-3 Fatty Acids. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Lara, C.A.; Ortiz, M.I.; Rodriguez-Ramos, F.; Chavez-Pina, A.E. Synergistic Interaction between Docosahexaenoic Acid and Diclofenac on Inflammation, Nociception, and Gastric Security Models in Rats. Drug Dev. Res. 2018, 79, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Lira, A.G.; Rodriguez-Ramos, F.; Ortiz, M.I.; Castaneda-Hernandez, G.; Chavez-Pina, A.E. Supra-Additive Interaction of Docosahexaenoic Acid and Naproxen and Gastric Safety on the Formalin Test in Rats. Drug Dev. Res. 2017, 78, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Lira, A.G.; Rodriguez-Ramos, F.; Chavez-Pina, A.E. Synergistic Antinociceptive Effect and Gastric Safety of the Combination of Docosahexaenoic Acid and Indomethacin in Rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2014, 122, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Tovar, J.; Blanca, M.; Garcia, A.; Gonzalez, J.; Gutierrez, S.; Paniagua, A.; Prieto, M.J.; Ramallo, L.; Llanos, L.; Duran, M. Preoperative Administration of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Postoperative Pain and Acute-Phase Reactants in Patients Undergoing Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1588–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustberg, M.B.; Orchard, T.S.; Reinbolt, R.; Andridge, R.; Pan, X.; Belury, M.; Cole, R.; Logan, A.; Layman, R.; Ramaswamy, B.; et al. Randomized Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial of Omega 3 Fatty Acids for Prevention of Aromatase Inhibitor-Induced Musculoskeletal Pain. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 2018, 167, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershman, D.L.; Unger, J.M.; Crew, K.D.; Awad, D.; Dakhil, S.R.; Gralow, J.; Greenlee, H.; Lew, D.L.; Minasian, L.M.; Till, C.; et al. Randomized Multicenter Placebo-Controlled Trial of Omega-3 Fatty Acids for the Control of Aromatase Inhibitor-Induced Musculoskeletal Pain: Swog S0927. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1910–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.D.; Nowacki, N.B.; Arseneau, L.; Eitel, M.; Hum, A. Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Neuropathic Pain: Case Series. Clin. J. Pain 2010, 26, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroon, J.C.; Bost, J.W. Omega-3 Fatty Acids (Fish Oil) as an Anti-Inflammatory: An Alternative to Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs for Discogenic Pain. Surg. Neurol. 2006, 65, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomer, A.; Kasey, S.; Connor, W.E.; Clark, S.; Harker, L.A.; Eckman, J.R. Reduction of Pain Episodes and Prothrombotic Activity in Sickle Cell Disease by Dietary N-3 Fatty Acids. Thromb. Haemost. 2001, 85, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojcikowski, K.; Vigar, V.J.; Oliver, C.J. New Concepts of Chronic Pain and the Potential Role of Complementary Therapies. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2020, 26, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulrazaq, M.; Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. Effect of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Arthritic Pain: A Systematic Review. Nutrition 2017, 39–40, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prego-Dominguez, J.; Hadrya, F.; Takkouche, B. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Phys. 2016, 19, 521–535. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, R.J.; Katz, J. A Meta-Analysis of the Analgesic Effects of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Supplementation for Inflammatory Joint Pain. Pain 2007, 129, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capsaicin. Neuropathic Pain: Playing with Fire. Prescrire Int. 2010, 19, 153–155. [Google Scholar]

- Babbar, S.; Marier, J.F.; Mouksassi, M.S.; Beliveau, M.; Vanhove, G.F.; Chanda, S.; Bley, K. Pharmacokinetic Analysis of Capsaicin after Topical Administration of a High-Concentration Capsaicin Patch to Patients with Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. Ther. Drug. Monit. 2009, 31, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasvang, E.K.; Hansen, J.B.; Malmstrom, J.; Asmussen, T.; Gennevois, D.; Struys, M.M.; Kehlet, H. The Effect of Wound Instillation of a Novel Purified Capsaicin Formulation on Postherniotomy Pain: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Anesth. Analg. 2008, 107, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Predel, H.G.; Ebel-Bitoun, C.; Peil, B.; Weiser, T.W.; Lange, R. Efficacy and Safety of Diclofenac + Capsaicin Gel in Patients with Acute Back/Neck Pain: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Study. Pain Ther. 2020, 9, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huygen, F.; Kern, K.U.; Perez, C. Expert Opinion: Exploring the Effectiveness and Tolerability of Capsaicin 179 Mg Cutaneous Patch and Pregabalin in the Treatment of Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. J. Pain Res. 2020, 13, 2585–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSID:1265957. Capsaicin. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.1265957.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Noto, C.; Pappagallo, M.; Szallasi, A. Ngx-4010, a High-Concentration Capsaicin Dermal Patch for Lasting Relief of Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2009, 10, 702–710. [Google Scholar]

- Galvez, R.; Navez, M.L.; Moyle, G.; Maihofner, C.; Stoker, M.; Ernault, E.; Nurmikko, T.J.; Attal, N. Capsaicin 8% Patch Repeat Treatment in Nondiabetic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: A 52-Week, Open-Label, Single-Arm, Safety Study. Clin. J. Pain 2017, 33, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankowski, C.; Poole, C.D.; Ernault, E.; Thomas, R.; Berni, E.; Currie, C.J.; Treadwell, C.; Calvo, J.I.; Plastira, C.; Zafeiropoulou, E.; et al. Effectiveness of the Capsaicin 8% Patch in the Management of Peripheral Neuropathic Pain in European Clinical Practice: The Ascend Study. BMC Neurol. 2017, 17, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zis, P.; Bernali, N.; Argira, E.; Siafaka, I.; Vadalouka, A. Effectiveness and Impact of Capsaicin 8% Patch on Quality of Life in Patients with Lumbosacral Pain: An Open-Label Study. Pain Phys. 2016, 19, E1049–E1053. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C.M.; Diamond, E.; Schmidt, W.K.; Kelly, M.; Allen, R.; Houghton, W.; Brady, K.L.; Campbell, J.N. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Injected Capsaicin for Pain in Morton’s Neuroma. Pain 2016, 157, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haanpaa, M.; Cruccu, G.; Nurmikko, T.J.; McBride, W.T.; Axelarad, A.D.; Bosilkov, A.; Chambers, C.; Ernault, E.; Abdulahad, A.K. Capsaicin 8% Patch Versus Oral Pregabalin in Patients with Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. Eur. J. Pain 2016, 20, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raber, J.M.; Reichelt, D.; Gruneberg-Oelker, U.; Philipp, K.; Stubbe-Drager, B.; Husstedt, I.W. Capsaicin 8% as a Cutaneous Patch (Qutenza): Analgesic Effect on Patients with Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2015, 115, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maihofner, C.G.; Heskamp, M.L. Treatment of Peripheral Neuropathic Pain by Topical Capsaicin: Impact of Pre-Existing Pain in the Quepp-Study. Eur. J. Pain 2014, 18, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, J.M.; Ringsted, T.K.; Petersen, M.; Sommer, C.; Uceyler, N.; Werner, M.U. A Capsaicin (8%) Patch in the Treatment of Severe Persistent Inguinal Postherniorrhaphy Pain: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoper, J.; Helfert, S.; Heskamp, M.L.; Maihofner, C.G.; Baron, R. High Concentration Capsaicin for Treatment of Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: Effect on Somatosensory Symptoms and Identification of Treatment Responders. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2014, 30, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maihofner, C.; Heskamp, M.L. Prospective, Non-Interventional Study on the Tolerability and Analgesic Effectiveness over 12 Weeks after a Single Application of Capsaicin 8% Cutaneous Patch in 1044 Patients with Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: First Results of the Quepp Study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2013, 29, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, G.; Backonja, M.; Rauck, R.; Webster, L.R.; Tobias, J.K.; Vanhove, G.F. Ngx-4010, a Capsaicin 8% Dermal Patch, Administered Alone or in Combination with Systemic Neuropathic Pain Medications, Reduces Pain in Patients with Postherpetic Neuralgia. Clin. J. Pain 2012, 28, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, L.R.; Peppin, J.F.; Murphy, F.T.; Lu, B.; Tobias, J.K.; Vanhove, G.F. Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of Ngx-4010, Capsaicin 8% Patch, in an Open-Label Study of Patients with Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2011, 93, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartrick, C.T.; Pestano, C.; Carlson, N.; Hartrick, S. Capsaicin Instillation for Postoperative Pain Following Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Preliminary Report of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Parallel-Group, Placebo-Controlled, Multicentre Trial. Clin. Drug Investig. 2011, 31, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrubasik, S.; Weiser, T.; Beime, B. Effectiveness and Safety of Topical Capsaicin Cream in the Treatment of Chronic Soft Tissue Pain. Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, 1877–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cianchetti, C. Capsaicin Jelly against Migraine Pain. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2010, 64, 457–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winocur, E.; Gavish, A.; Halachmi, M.; Eli, I.; Gazit, E. Topical Application of Capsaicin for the Treatment of Localized Pain in the Temporomandibular Joint Area. J. Orofac. Pain 2000, 14, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- McCleane, G. Topical Application of Doxepin Hydrochloride, Capsaicin and a Combination of Both Produces Analgesia in Chronic Human Neuropathic Pain: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000, 49, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.; CLoprinzi, L.; Kugler, J.; Hatfield, A.K.; Miser, A.; Sloan, J.A.; Wender, D.B.; Rowland, K.M.; Molina, R.; Cascino, T.L.; et al. Phase Iii Placebo-Controlled Trial of Capsaicin Cream in the Management of Surgical Neuropathic Pain in Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 2974–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeri, M.; Beneforti, P.; Benaim, G.; Maggi, C.A.; Lecci, A.; Turini, D. Intravesical Capsaicin for Treatment of Severe Bladder Pain: A Randomized Placebo Controlled Study. J. Urol. 1996, 156, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Henderson, M.; Nadoolman, W.; Duffy, V.; Cooper, D.; Saberski, L.; Bartoshuk, L. Oral Capsaicin Provides Temporary Relief for Oral Mucositis Pain Secondary to Chemotherapy/Radiation Therapy. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 1995, 10, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, D.; Bertelli, G.; Gozza, A.; Forno, G.G. Treatment of the Post-Mastectomy Pain Syndrome with Topical Capsaicin. Pain 1993, 54, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, S.; Rice, A.S.; Cole, P.; Tan, T.; Moore, R.A. Topical Capsaicin (High Concentration) for Chronic Neuropathic Pain in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 1, CD007393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mou, J.; Paillard, F.; Turnbull, B.; Trudeau, J.; Stoker, M.; Katz, N.P. Qutenza (Capsaicin) 8% Patch Onset and Duration of Response and Effects of Multiple Treatments in Neuropathic Pain Patients. Clin. J. Pain 2014, 30, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laslett, L.L.; Jones, G. Capsaicin for Osteoarthritis Pain. Prog. Drug. Res. 2014, 68, 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, L.; Moore, R.A.; Derry, S.; Edwards, J.E.; McQuay, H.J. Systematic Review of Topical Capsaicin for the Treatment of Chronic Pain. BMJ 2004, 328, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiao, J.; Tang, X.; Gong, X.; Yin, H.; Jiang, Q.; Wei, C. Effect of Cream, Prepared with Tripterygium Wilfordii Hook F and Other Four Medicinals, on Joint Pain and Swelling in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Double-Blinded, Randomized, Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2019, 39, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Canter, P.H.; Lee, H.S.; Ernst, E. A Systematic Review of Randomised Clinical Trials of Tripterygium Wilfordii for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Phytomedicine 2006, 13, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, J.; Dai, S.M. A Chinese Herb Tripterygium Wilfordii Hook F in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Mechanism, Efficacy, and Safety. Rheumatol. Int. 2011, 31, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, M.; Gagnier, J.J.; Chrubasik, S. Herbal Therapy for Treating Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2, CD002948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Dong, Y.; Jin, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, J.; Shi, J.; Li, J. The Novel and Potent Anti-Depressive Action of Triptolide and Its Influences on Hippocampal Neuroinflammation in a Rat Model of Depression Comorbidity of Chronic Pain. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 64, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qiao, Y.; Yang, R.S.; Zhang, C.K.; Wu, H.H.; Lin, J.J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, T.; Li, Y.Q.; Dong, Y.L.; et al. The Synergistic Effect of Treatment with Triptolide and Mk-801 in the Rat Neuropathic Pain Model. Mol. Pain 2017, 13, 1744806917746564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CSID:97099. Triptolide. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.97099.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- CSID:109405. Celastrol. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.109405.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Ren, J.; Zhu, C.; Fu, J.; Lin, D.; Qiu, Y. Celastrol Attenuates Inflammatory and Neuropathic Pain Mediated by Cannabinoid Receptor Type 2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 13637–13648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Guo, F.; Luo, Y.C.; Zhu, J.P.; Wang, J.L. Efficacy of Tripterygium Glycosides Tablet in Treating Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015, 34, 1831–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M. Herbal Treatment of Headache. Headache 2012, 52 (Suppl. 2), 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benemei, S.; de Logu, F.; Puma, S.L.; Marone, I.M.; Coppi, E.; Ugolini, F.; Liedtke, W.; Pollastro, F.; Appendino, G.; Geppetti, P.; et al. The Anti-Migraine Component of Butterbur Extracts, Isopetasin, Desensitizes Peptidergic Nociceptors by Acting on Trpa1 Cation Channel. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 2897–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CSID:4444859. Petasin. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.4444859.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- CSID:4477154. Isopetasin. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.4477154.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Anderson, N.; Borlak, J. Hepatobiliary Events in Migraine Therapy with Herbs-the Case of Petadolex, a Petasites Hybridus Extract. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bigal, M.E.; Krymchantowski, A.V.; Rapoport, A.M. Prophylactic Migraine Therapy: Emerging Treatment Options. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2004, 8, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, O.; Mauskop, A. Nutraceuticals in Acute and Prophylactic Treatment of Migraine. Curr. Treat Options Neurol. 2016, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, R.E.; Beuthin, J.; Granetzke, L. Complementary and Integrative Medicine for Episodic Migraine: An Update of Evidence from the Last 3 Years. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2019, 23, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, A.; Sweet, B.V. Butterbur: An Alternative Therapy for Migraine Prevention. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2010, 67, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiebich, B.L.; Grozdeva, M.; Hess, S.; Hull, M.; Danesch, U.; Bodensieck, A.; Bauer, R. Petasites Hybridus Extracts in Vitro Inhibit Cox-2 and Pge2 Release by Direct Interaction with the Enzyme and by Preventing P42/44 Map Kinase Activation in Rat Primary Microglial Cells. Planta Med. 2005, 71, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pothmann, R.; Danesch, U. Migraine Prevention in Children and Adolescents: Results of an Open Study with a Special Butterbur Root Extract. Headache 2005, 45, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipton, R.B.; Gobel, H.; Einhaupl, K.M.; Wilks, K.; Mauskop, A. Petasites Hybridus Root (Butterbur) Is an Effective Preventive Treatment for Migraine. Neurology 2004, 63, 2240–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, H.C.; Rahlfs, V.W.; Danesch, U. The First Placebo-Controlled Trial of a Special Butterbur Root Extract for the Prevention of Migraine: Reanalysis of Efficacy Criteria. Eur. Neurol. 2004, 51, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, W.; Schmidramsl, H. An Extract of Petasites Hybridus Is Effective in the Prophylaxis of Migraine. Altern. Med. Rev. 2001, 6, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CSID:4976071. Parthenolide. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.4976071.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Sato, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Takahashi, S.; Kumagai, T.; Nagata, K. Development of a Highly Reproducible System to Evaluate Inhibition of Cytochrome P450 3a4 Activity by Natural Medicines. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 18, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cady, R.K.; Goldstein, J.; Nett, R.; Mitchell, R.; Beach, M.E.; Browning, R. A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study of Sublingual Feverfew and Ginger (Lipigesic M) in the Treatment of Migraine. Headache 2011, 51, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, H.C.; Pfaffenrath, V.; Schnitker, J.; Friede, M.; Zepelin, H.H.H. Efficacy and Safety of 6.25 Mg T.I.D. Feverfew Co2-Extract (Mig-99) in Migraine Prevention--a Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicentre, Placebo-Controlled Study. Cephalalgia 2005, 25, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffenrath, V.; Diener, H.C.; Fischer, M.; Friede, M.; Zepelin, H.H.H.; Investigators. The Efficacy and Safety of Tanacetum Parthenium (Feverfew) in Migraine Prophylaxis--a Double-Blind, Multicentre, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Dose-Response Study. Cephalalgia 2002, 22, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattrick, M.; Heptinstall, S.; Doherty, M. Feverfew in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Double Blind, Placebo Controlled Study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1989, 48, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wider, B.; Pittler, M.H.; Ernst, E. Feverfew for Preventing Migraine. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, CD002286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shara, M.; Stohs, S.J. Efficacy and Safety of White Willow Bark (Salix Alba) Extracts. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, B.; Ludtke, R.; Selbmann, H.K.; Kotter, I.; Tschirdewahn, B.; Schaffner, W.; Heide, L. Efficacy and Tolerability of a Standardized Willow Bark Extract in Patients with Osteoarthritis: Randomized Placebo-Controlled, Double Blind Clinical Trial. Phytother. Res. 2001, 15, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biegert, C.; Wagner, I.; Ludtke, R.; Kotter, I.; Lohmuller, C.; Gunaydin, I.; Taxis, K.; Heide, L. Efficacy and Safety of Willow Bark Extract in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis: Results of 2 Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trials. J. Rheumatol. 2004, 31, 2121–2130. [Google Scholar]

- CSID:388601. D-(−)-Salicin. Available online: http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.388601.html (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Oketch-Rabah, H.A.; Marles, R.J.; Jordan, S.A.; Dog, T.L. United States Pharmacopeia Safety Review of Willow Bark. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 1192–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebe, W. Herbal Medication: Potential for Adverse Interactions with Analgesic Drugs. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2002, 27, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uehleke, B.; Muller, J.; Stange, R.; Kelber, O.; Melzer, J. Willow Bark Extract Stw 33-I in the Long-Term Treatment of Outpatients with Rheumatic Pain Mainly Osteoarthritis or Back Pain. Phytomedicine 2013, 20, 980–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, A.M.; Wegener, T. Willow Bark Extract (Salicis Cortex) for Gonarthrosis and Coxarthrosis--Results of a Cohort Study with a Control Group. Phytomedicine 2008, 15, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrubasik, S.; Kunzel, O.; Model, A.; Conradt, C.; Black, A. Treatment of Low Back Pain with a Herbal or Synthetic Anti-Rheumatic: A Randomized Controlled Study. Willow Bark Extract for Low Back Pain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001, 40, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vlachojannis, J.E.; Cameron, M.; Chrubasik, S. A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Willow Bark for Musculoskeletal Pain. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Journal and Year of Publication | Type of Study | Number of Patients, Duration of Study | Study Groups, Active Agent and Placebo Dosage | Key Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Studies | |||||

| Loughren, M.J. et al. | Anesthesiology 2020 | Randomized parallel-group clinical trial | 16 human volunteers, 35 days study, 21 days of treatment, 12 h follow up after intravenous fentanyl administration | Healthy volunteers receiving SJW tablet 300 mg thrice daily (n = 8) versus placebo tablet (n = 8) | SJW does not alter fentanyl pharmacodynamics or clinical effects, likely does not affect hepatic clearance or blood-brain barrier efflux. Taking SJW will likely not respond differently to intravenous fentanyl for analgesia or anesthesia [23]. |

| Galeotti, N. et al. | Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 2014 | Clinical trial with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures | 8 human volunteers, 170 rodents, 5 days treatment, up to 1 h follow up | Rodents (adult male Swiss albino mice and rats), healthy male volunteers receiving oral morphine co-administered with SJW 300 mg tablets or morphine alone | A low dose of SJW significantly potentiated oral 10 mg morphine’s analgesic effect in humans and rodents [24]. |

| Peltoniemi, M. A. et al. | Fundamental and Clinical Pharmacology 2012 | Placebo-controlled, randomized, cross-over clinical trial | 12 healthy nonsmoking volunteers, 14 days SJW phase and 14 days placebo phase with 4 weeks interval, 24 h follow up | Oral SJW 300 mg versus placebo, six women and six men | SJW decreased the exposure to oral S-ketamine but was not associated with significant changes in the analgesic or behavioral effects of ketamine. Usual doses of S-ketamine if used concomitantly with SJW may become ineffective [25]. |

| Clewell, A. et al. | Journal of Drugs in Dermatology 2012 | Prospective, randomized, multi-centered, comparative, open-label clinical study | 149 (120 participants received treatment), 14 days treatment and follow up | Patients with active HSV-1 and HSV-2 lesions receiving single use of Dynamiclear formulation (n = 61), and patients receiving repeat topical 5% Acyclovir (n = 59) | A single application of topical formulation containing hypericum perforatum and copper sulfate is helpful in the management of burning and stinging sensation, erythema, vesiculation, and acute pain caused by HSV-1 and HSV-2 lesions in adults [26]. |

| Nieminen, T. H. et al. | European Journal of Pain (London, England) 2010 | Placebo-controlled, randomized, cross-over clinical trial | 12 healthy, non-smoking volunteers, 15 days SJW phase and 15 days control phase with 4 weeks interval, up to 48 h follow up | 6 women and 6 men, oral SJW 300 mg versus placebo thrice daily | SJW significantly decreased the plasma concentrations of oral oxycodone 15 mg and also the self-reported drug effect. This may be of clinical significance in chronic pain management [21]. |

| Sindrup, S. H. Et al. | Pain 2001 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled and cross-over | 54 (47 patients completed the study), 2 treatment period of 5 weeks duration | Oral SJW (2700 µg total hypericin daily, n = 27)) versus placebo tablet (n = 27), up to 6 paracetamol 500 mg tablets could be used daily as escape medication | There was a trend of lower total pain score with oral SJW compared to the placebo group. However, none of the volunteers’ pain ratings were significantly changed by SJW as compared to placebo. Complete, good, or moderate pain relief was reported by nine patients taking SJW and two with placebo. In conclusion, SJW does not have a significant effect on pain due to polyneuropathy [27]. |

| Review Article | |||||

| Galeotti, N. | Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2017 | Review Article | - | Preclinical animal, in vivo and in vitro studies, clinical trials with dental pain | Preclinical animal studies showed the potential of low doses SJW dry extracts to induce antinociception, mitigate acute and chronic hyperalgesic states, and to augment opioid analgesia. Clinical studies showed SJW is promising in dental pain conditions. SJW analgesia appears at low doses (5–100 mg/kg), decreasing the risk of herbal–drug interactions caused by hyperforin, a potent CYP enzymes inducer [28]. |

| Author | Journal and Year of Publication | Type of Study | Number of Patients, Duration of Study | Study Groups, Active Agent and Placebo Dosage | Key Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Studies | |||||

| Martins, L. B. et al. | Cephalalgia: an International Journal of Headache 2018 | Double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial | 60 patients, 2 h session, up to 48 h follow-up | Emergency room patients suffering from migraine headaches received 400 mg of ginger extract capsules (5% active gingerols or 20 mg, n = 30) or placebo (cellulose, n = 30), in addition to an intravenous ketoprofen 100 mg | Patients treated with ginger and NSAIDs for migraine attacks had significantly better clinical responses [46]. |

| Rondanelli, M. et al. | Natural Product Research 2017 | Prospective trial | 15 patients, 30 days treatment and follow up | 13 women and 2 men with chronic inflammation, pain due to knee arthrosis and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs NSAIDs poor responders receiving highly standardized ginger 25 mg and Echinacea 5 mg extract supplementation | A decrease in 0.52 cm in knee circumference (p < 0.01), SF-36 (p < 0.05), and a significant improvement of 12.27 points was observed for Lysholm scale score (p < 0.05) [47]. |

| Black, C. D. et al. | The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society 2010 | Double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized experiments | Study 1: 34 patients Study 2: 40 patients, 11 consecutive days for each study | Study 1: 2 g of Raw ginger (n = 17) versus placebo (n = 17) Study 2: 2 g of heat-treated ginger supplementation (n = 20) versus placebo (n = 20) on muscle pain | Patients taking daily raw and heat-treated ginger had a moderate-to-large reduction in muscle pain following exercise-induced muscle injury. Ginger has hypoalgesic effects in patients with osteoarthritis and is an effective pain reliever [37]. |

| Black, C. D. et al. | Phytotherapy Research: PTR 2010 | Double-blind, cross-over design | 27 patients, 3 consecutive days | 13 men and 15 women receiving 2 g of ginger or 2 g of placebo (white flour) 24 h and 48 h after exercise | Ingestion of a single 2 g dose of ginger does not lessen inflammation, dysfunction, and eccentric exercise-induced muscle pain. However, ginger may decrease day-to-day muscle pain progression [36]. |

| Black, C. D. et al. | International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 2008 | Double-blind, crossover design | 25 patients, 1 day preliminary testing and 2 days of experimental testing | 10 men and 15 women receiving 2 g dose of oral ginger or 2 g placebo (flour) | Consumption of ginger had no clinically or statistically significant effect on perceptions of muscle pain during exercise compared with placebo [35]. |

| Cady, R. K. et al. | Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research 2005 | Open-label study | 29 patients, one session with 24 h follow up | 24 females and 5 males with a history of migraines receiving two 2 mL sublingual doses of GelStat Migraine (3× feverfew, 2× ginger) 5 min apart, second treatment could be used between 60 min and 24 hr, subjects were also allowed to take usual migraine therapy 2 hr after initial dose of study medication | Administration of sublingual ginger and feverfew compound (GelStat Migraine) early during the mild headache phase is effective as a first-line abortive treatment for acute migraine [48]. |

| Altman, R. D. et al. | Arthritis and Rheumatism 2001 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, parallel-group, 6-week study trial | 261 (247 patients completed the study), 6 weeks of treatment and follow up | Patients receiving ginger extract (255 mg of EV.EXT 77, n = 130) versus patients receiving placebo capsules (coconut oil, n = 131) twice daily, Acetaminophen was permitted as rescue medication | The highly purified and standardized ginger extract had a statistically significant moderate effect on reducing symptoms of knee osteoarthritis with a good safety profile (mostly mild gastrointestinal adverse events in the ginger extract group) [49]. |

| Bliddal, H. et al. | Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2000 | Randomized, controlled, double blind, double dummy, cross-over study | 75 (56 patients completed the study), 3 treatment periods of 3 weeks each. | 15 men and 41 women with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee receiving ginger extract (170 mg EV.ext-33) versus placebo versus ibuprofen 400 mg thrice daily, Acetaminophen maximum 3 gr daily as rescue drug | In the first period of treatment before cross-over, a statistically significant effect of the ginger extract was demonstrated by explorative statistical methods. However, a significant difference was not observed in the study as a whole [50]. |

| Review Articles | |||||

| Chen, C. X. et al. | Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: eCAM 2016 | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) | 598 | Women with dysmenorrhea taking oral ginger (750–2500 mg daily) versus placebo or active treatment (ibuprofen, NSAIDs, mefenamic acid, zinc, or progressive muscle relaxation) | Oral ginger can be an effective treatment for menstrual pain in dysmenorrhea. However, due to the small number of studies, high heterogeneity across trials, and poor methodological quality of the studies the findings need to be interpreted with caution [51]. |

| Wilson, P. B. | Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2015 | Systematic review of randomized trials (6 analgesic and 8 ergogenic articles) | Analgesic: 175 Ergogenic Aid: 106 | Randomized crossovers or parallel receiving ginger (2–4 gr daily) or placebo | Taking ginger over 1–2 weeks may reduce pain from prolonged running and eccentric resistance exercise. However, its safety and efficacy as an analgesic for a wide range of athletic endeavors need to be further studied [52]. |

| Terry, R. et al. | Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2011 | Systematic review (7 articles) | 481 | Human adults suffering from any pain condition, taking oral Z. officinale, treatment against a comparison condition | Seven published articles, reporting eight trials were included in the review and assessed using the Jaded scale. The use of Z. officinale for the treatment of pain cannot be recommended at present due to a paucity of well-conducted trials [38]. |

| Leach, M. J. et al. | JBI Library of Systematic Reviews 2008 | Systemic review of 3 randomized clinical trials | 680 | Patients with osteoarthritis receiving ginger versus placebo versus ibuprofen | The evidence for administration of ginger in adults with osteoarthritis of the knee and/or hip is weak, due to significant heterogeneity between the studies. It is recommended to improve the research design, instrumentation, and ginger dosage, which may help to demonstrate the safe and effective use of ginger in patients with osteoarthritis [53]. |

| Author | Journal and Year of Publication | Type of Study | Number of Patients, Duration of Study | Study Groups, Active Agent and Placebo Dosage | Key Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Studies | |||||

| Haroyan, A. et al. | BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2018 | Three-arm, parallel-group, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial | 201 patients, 12 weeks treatment and follow up | Patients receiving Curamin 500 mg capsules (n = 67) versus Curamed 500 mg capsules (curamin combined with boswellic acid, n = 66) versus placebo capsules (500 mg excipients, n = 68) thrice daily | Administration of curcumin complex or its combination with boswellic acid for twelve-weeks reduces pain-related symptoms in patients with osteoarthritis compared to placebo. Curcumin in combination with boswellic acid is more effective presumably due to synergistic effect [65]. |

| Appelboom, T. et al. | The Open Rheumatology Journal 2014 | Retrospective observational study | 820 patients, 6 months of treatment and up to 6 months follow up after treatment | Patients with joint problems treated with the curcumin preparation Flexofytol® (42 mg curcumin, 739 were using 2 capsules two times daily and 81 took 2 capsules 3 times daily) | Flexofytol® is a potential nutraceutical for patients with joint problems, with great tolerance and rapid effect for pain, articular mobility, and quality of life [66]. |

| Kalluru, H. et al. | Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 2020 | Prospective, consecutive case series | 60 patients, 21 days treatment | Breast cancer patients receiving combination of turmeric supplementation 2 g daily and paclitaxel chemotherapy | Turmeric supplementation improved quality of life scores and led to clinically relevant and statistically significant improvement in global health status, symptom scores (fatigue, nausea, vomiting, pain, appetite loss, insomnia), and hematological parameters [57]. |

| Review Articles | |||||

| Eke-Okoro, U. J. et al. | Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2018 | Systemic review of pre-clinical and clinical studies | 921 | Observational or turmeric versus placebo or active controls | Turmeric (curcumin) may be used as a sole analgesic or as a combination of opioid, NSAIDs, or paracetamol (acetaminophen) sparing strategies [67]. |

| Gaffey, A. et al. | JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports 2017 | Thirteen studies both experimental and epidemiological study designs including RCTs, non-RCTs, quasi-experimental and before and after studies | 1101 | Patients with musculoskeletal pain receiving curcuminoids versus placebo versus NSAIDs versus curcuminoid-containing herbomineral mixtures versus placebo or active controls | In musculoskeletal pain conditions, there is insufficient evidence to recommend administration of curcuminoids to relieve pain and improve function. This is due to limitations caused by the small number of relevant studies, small sample sizes, variability in study quality, short interventional durations, gender-bias toward females, and lack of long-term data extraction [68]. |

| Perkins, K. et al. | Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine 2017 | Review of 8 clinical trials | 874 | Observational or turmeric versus placebo or active controls | Published clinical trials demonstrate similar efficacy of Curcuma formulations compared to NSAIDs and potentially to glucosamine in treating osteoporosis symptoms. While there was statistical significance in the majority of the studies, due to major study limitations and the small magnitude of the effect, the validity of the results are questionable and further rigorous studies are needed before recommending Curcuma as an effective therapy for knee osteoarthritis [69]. |

| Daily, J. W. et al. | Journal of Medicinal Food 2016 | Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials | 1874 | Patients receiving turmeric extract versus placebo or active controls | The studies provide evidence for the efficacy of about 1000 mg/day of curcumin in treating arthritis. However, due to the insufficient total number of RCTs in this analysis, the methodological quality of the primary studies, and total sample size, a definitive conclusion can not be made. Further rigorous and larger studies are required to confirm the efficacy of turmeric in treating arthritis [70]. |

| Author | Journal and Year of Publication | Type of Study | Number of Patients, Duration of Study | Study Groups, Active Agent and Placebo Dosage | Key Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Studies | |||||

| Ruiz-Tovar, J. et al. | Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2018 | Prospective randomized clinical trial | 40 patients, treatment was started 10 days up to 8 h before surgery, 30 days follow up after surgery | Patients receiving a preoperative balanced energy high-protein (10 g/100 mL) formula (control group, n = 20) and patients receiving the same preoperative nutritional formula enriched with O3FA (2 g EPA/400 mL) (experimental group, n = 20) | A preoperative diet enriched with O3FA is associated with reduced postoperative pain, decreased postoperative levels of C-reactive protein, and a greater preoperative weight loss in patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass [82]. |

| Lustberg, M. B. et al. | Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2018 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 44 (35 women completed the study), 24 weeks treatment and follow up | Comparing 4.3 g/day of n-3 PUFA supplements (n = 22) versus placebo (mixture of fats and oils, n = 22) | High-dose n-3 PUFA supplementation taken concomitantly with aromatase inhibitors (AIs) is well tolerated and feasible in postmenopausal breast cancer. However, the mean pain severity scores using the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) for joint symptoms did not change significantly by time or treatment arm. Further studies are needed to evaluate its efficacy in preventing joint symptoms [83]. |

| Hershman, D. L. et al. | Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2015 | Randomized multicenter placebo-controlled trial | 249 patients, 24 weeks treatment and follow up | 3.3 g/day O3FA (n = 122) versus placebo (blend of soybean and corn oil, n = 127) | There were a considerable (>50%) and sustained improvement in aromatase inhibitor arthralgia for both O3FAs and placebo but based on BPI-SF scores there was no meaningful difference between the groups [84]. |

| Ko, G. D. et al. | The Clinical Journal of Pain 2010 | Clinical series | 5 patients, up to 19 months of treatment and follow up | Five patients receiving high oral doses of omega-3 fish oil (2400–7200 mg/day) | There was improved function and clinically significant pain reduction up to 19 months after treatment initiation. Therefore, O3FAs may be beneficial in treating neuropathic pain in patients with cervical radiculopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, fibromyalgia, and burn injury. Further studies with RCTs in a more specific neuropathic pain population are required [85]. |

| Maroon, J. C. et al. | Surgical Neurology 2006 | Prospective study | 250 patients, average of 75 days treatment, one month follow up | Patients who had nonsurgical neck or back pain receiving a total of 1200 mg/day of omega-3 EFAs | Taking O3FA supplement demonstrated equivalent effect in reducing arthritic pain compared to NSAIDs. O3FA fish oil supplements are a safer alternative to NSAIDs in treating nonsurgical neck or back [86]. |

| Tomer, A. et al. | Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2001 | Double-blind, controlled clinical trial | 20 patients, 1 year treatment and follow up | O3FA (0.1 g/kg/day, n = 5) versus olive oil (0.25 g/kg/day, n = 5) versus asymptomatic control group without sickle cell disease (n = 10) | Dietary n-3FAs reduce the frequency of pain episodes in sickle cell disease likely by reducing prothrombotic activity [87]. |

| Review Articles | |||||

| Wojcikowski, K. et al. | Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 2018 | Review of literature | - | Patients with chronic pain | There are several complementary therapies that may be effective in reducing chronic pain or the need for analgesics. Some of these therapies include O3FAs, curcumin, and capsaicin. Multimodal individualized treatment for each patient is recommended [88]. |

| Abdulrazaq, M. et al. | Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 2017 | Review article of 18 RCTs | 1143 | Patients receiving omega-3 PUFAs versus placebo or active controls | Omega-3 PUFAs may decrease pain associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Doses of 3 to 6 g/day have a greater effect. However, Due to the limitations found in the reviewed RCTs including small populations and short study periods, further research is needed [89]. |

| Prego-Dominguez, J. et al. | Pain Physician 2016 | Meta-analysis, systematic review | 985 | Patients receiving O3FA or olive oil | Omega-3 PUFA supplementation can moderately improve chronic pain, mostly due to dysmenorrhea. More studies on the preventive potential of PUFA supplementation is needed [90]. |

| Goldberg, R. J. et al. | Pain 2007 | Meta-analysis of 17 RCTs | 823 | Patients receiving Omega-3 PUFA or olive oil | Omega-3 PUFA supplementation for at least 3 months demonstrated improvement in joint pain caused by rheumatoid arthritis, or joint pain secondary to inflammatory bowel disease, and dysmenorrhea [91]. |

| Author | Journal and Year of Publication | Type of Study | Number of Patients, Duration of Study | Study Groups, Active Agent and Placebo Dosage | Key Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Studies | |||||

| Galvez, R. et al. | The Clinical Journal of Pain 2017 | Prospective, open-label, observational study | 306 patients, repeat treatments and follow up over 52 weeks | Patients with posttraumatic or postsurgical nerve injury, postherpetic neuralgia, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) associated distal sensory polyneuropathy, or other peripheral neuropathic pain receiving </= 6 capsaicin 8% patch with retreatment at 9 to 12 week intervals | Capsaicin 8% patch is well-tolerated with a variable alteration in sensory function and nominal risk for complete sensory loss [99]. |

| Mankowski, C. et al. | BMC Neurology 2017 | Cohort, open-label, observational, multicenter, European non-interventional study | 429 (420 patients received at least one treatment), </= 52 weeks treatment and followup | Patients with non-diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy (PNP) received up to 4 capsaicin 8% patch (179 mg of capsaicin) per treatment (at least 90 days interval) | Capsaicin 8% patch is effective, generally well-tolerated, and can result in sustained pain relief, significant improvement in overall health status and quality of life [100]. |

| Zis, P. et al. | Pain Physician 2016 | Prospective open-label study | 90 patients, single treatment and follow up at 2, 8, and 12 weeks | Patients with lumbosacral pain received capsaicin 8% patch | Treatment with capsaicin 8% patch resulted in substantial neuropathic pain relief and improved quality of life. The results should be further evaluated in a prospective randomized placebo-controlled study [101]. |

| Campbell, C. M. et al. | Pain 2016 | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study | 58 patients, single treatment, 4 weeks follow up | A single capsaicin 0.1 mg dose (n = 30) versus placebo (n = 28) injected into the region of the Morton’s neuroma | A trend toward significance was found in the second and third week. In the capsaicin-treated group, there was a reduction in oral analgesics and improvement in functional interference scores. Based on the findings, injection of capsaicin in painful intermetatarsal neuroma is an effective treatment [102]. |

| Haanpaa, M. et al. | European Journal of Pain (London, England) 2016 | Open-label, randomized, multicenter, non-inferiority trial. | 629 (559 patients received study medication), 8 weeks follow up | Patients received either the capsaicin 8% patch (1 to 4 patches, n = 282) or an optimized dose of oral pregabalin (75 mg/day up to 600 mg/day, n = 277) | Capsaicin 8% patch resulted in a faster onset of action, fewer systematic adverse events, greater treatment satisfaction, and non-inferior pain relief compared to an optimized dose of pregabalin in patients with PNP [103]. |

| Raber, J. M. et al. | Acta Neurologica Belgica 2015 | Clinical trial | 37 patients received single treatment, observed 4 weeks prior to 12 weeks post administration | Patients suffering from painful, distal symmetric polyneuropathy for an average of 5 years. Single application of the capsaicin 8% cutaneous patch (Qutenza™) | The capsaicin 8% cutaneous patch resulted in a substantial relief of neuropathic pain, a prolongation of sleep mainly in patients with HIV infection, decreased oral pain medication consumption, and a resumption of social activities [104]. |

| Maihofner, C. G. et al. | European Journal of Pain (London, England) 2014 | Prospective multicenter RCT | 1063 (1044 patients evaluated for effectiveness), single application, 12 weeks follow up | Non-diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathic pain. single application of capsaicin 8% cutaneous patch | The highest treatment response was observed with the capsaicin 8% cutaneous patch in patients suffering from peripheral neuropathic pain of fewer than 6 months. This shows early initiation of topical treatment is recommended [105]. |

| Bischoff, J. M. et al. | PLoS One 2014 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 46 patients, 3 months follow up | Patients suffering from inguinal post-herniorrhaphy pain received either an inactive placebo patch (n = 22) or a capsaicin 8% patch (n = 24) | A trend toward pain improvement was observed in patients treated with capsaicin 8% patch after 1 month, but there were no significant differences in pain relief between the capsaicin and placebo group [106]. |

| Hoper, J. et al. | Current Medical Research and Opinion 2014 | Prospective non-interventional trial | 1044 patients (822 patients completed the pain-DETECT questionaire at baseline, 571 completed questionaire at baseline and week 12), 12 weeks follow-up | Patients with peripheral neuropathic pain treated with capsaicin 8% cutaneous patch. Single application of up to 4 patches, applied 30 min for feet or 60 min other body parts. | Applying topical capsaicin 8% in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain effectively reduced sensory abnormalities. Completion of the pain-DETECT questionnaire was optional and therefore the data was incomplete and not available for all patients. Further studies are needed to confirm these results [107]. |

| Maihofner, C. et al. | Current Medical Research and Opinion 2013 | Prospective, non-interventional study | 1040 patients, single application, 12 weeks follow up | Patients with peripheral neuropathic pain received single capsaicin 8% patch application of up to 4 patches | Application of capsaicin 8% patch is safe and effective. Because there was no control group, a comparison of the study results with that of therapeutic alternatives is not justified [108]. |

| Irving, G. et al. | The Clinical Journal of Pain 2012 | Double blind, randomized controlled studies | 1127 patients, single 60 min treatment, 12 weeks follow up | Patients suffering from postherpetic neuralgia on at least 1 systemic neuropathic pain medication: 302 patients received capsaicin 8% patch and 250 control (capsaicin, 0.04%). Patients not on systemic neuropathic pain medication: 295 received capsaicin 8% patch and 280 control | A single capsaicin 8% patch for 60-min reduces postherpetic neuralgia for up to 12-weeks regardless of concomitant use of systemic neuropathic pain medication [109]. |

| Webster, L. R. et al. | Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2011 | Open-label, randomized, uncontrolled clinical trial | 117 patients, 12 weeks follow up | Patients were pre-treated with one of three 4% lidocaine topical anesthetics (Topicaine Gel, or Betacaine Enhanced Gel 4, or L.M.X.4,) followed by single capsaicin 8% patch application for 60- or 90- min | Applying capsaicin 8% patch with any of the three topical anesthetics was well-tolerated, generally safe, and reduced pain over 12 weeks in patients with postherpetic neuralgia and painful diabetic neuropathy [110]. |

| Hartrick, C. T. et al. | Clinical Drug Investigation 2011 | Randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, double-blind study | 14 patients, 42 days follow up | Patients received direct instillation of capsaicin 15 mg (Anesiva 4975, n = 7) or placebo (n = 7) into the surgical site immediately prior to total knee arthroplasty wound closure, postoperative IV morphine for 24 hr and oral oxycodone as rescue medication were provided | While patients receiving capsaicin had higher BMIs, they had comparable or better pain scores, longer-lasting effect, improved active range of motion at 14 days, less opioid use in the first 3 postoperative days, and less pruritis which likely is related to the opioid-sparing effect [111]. |

| Chrubasik, S. et al. | Phytotherapy Research: PTR 2010 | Randomized double-blind multicenter study | 281 patients treated (only 130 included in analysis), 3 weeks of treatment and follow up | Patients receiving capsaicin 0.05% cream (Finalgon ® CPDWarmecreme, n = 140) or placebo (n = 141) | Capsaicin cream is effective and well-tolerated in patients with chronic soft tissue pain and patients with chronic back pain compared to the placebo group [112]. |

| Cianchetti, C | International Journal of Clinical Practice 2010 | Single-blinded placebo-controlled cross-over study | 23 patients, 30 min follow up after application of treatment | 20 females and 3 males with painful arteries in absence of migraine attack receiving topical capsaicin 0.1% or vaseline jelly | While the number of patients was small, results show topical capsaicin is effective in relieving arterial pain during and in the absence of migraine attacks [113]. |

| Aasvang, E. K. et al. | Anesthesia and Analgesia 2008 | Single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | 41 patients, Single treatment, 4 weeks follow up | Adult male patients receiving wound instillation of 1000 mcg of ultra-purified capsaicin (ALGRX 4975, n = 20) after open mesh groin hernia repair versus placebo (water, n = 21) | The study analysis showed during the first 3–4 days after inguinal hernia repair, capsaicin has superior analgesia compared to placebo [94]. |

| Predel, H.-G. et al. | Pain and Therapy 2020 | Randomized, double-blind, controlled, multicenter, parallel group trial | 746 patients, treated twice daily for 5 days, 6 days follow up | Patients with acute back or neck pain were treated with topical diclofenac 2% + capsaicin 0.075% (n = 225), diclofenac 2% (n = 223), capsaicin 0.075% (n = 223) or placebo (n = 75) | Capsaicin alone and capsaicin + diclofenac showed superior benefit compared with placebo. However, diclofenac alone demonstrated efficacy comparable with placebo, and therefore its addition to capsaicin added no increased pain relief over capsaicin alone [95]. |

| Winocur, E. et al. | Journal of Orofacial Pain 2000 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | 30 patients, 4 weeks topical application 4 times daily with follow up at end of each week | Patients with unilateral pain in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) area received capsaicin 0.025% cream (n = 17) or its vehicle (placebo, n = 13) to the painful TMJ area | There was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and placebo groups. The factor of time had a major effect on the non-specific improvement of the assessed parameters and the placebo effect had an important role in treating the patients with TMJ pain [114]. |

| McCleane, G. | British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2000 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | 200 (151 patients provided results), 4 weeks treatment and follow up | Patients applied topical 3.3% doxepin (n = 41), 0.025% capsaicin (n = 33), placebo (aqueous cream, n = 41), or 3.3% doxepin/ 0.025% capsaicin cream (n = 36) thrice daily | Overall pain was substantially reduced by 0.025% capsaicin, 3.3% doxepin and also their combination. The combination of doxepin, and capsaicin resulted in more rapid onset and analgesia. Capsaicin substantially decreased sensitivity and shooting pain [115]. |

| Ellison, N. et al. | Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 1997 | Placebo-controlled trial | 99 patients, four times daily treatment for 16 weeks, weekly questionnaires as follow up | All patients with postsurgical neuropathic pain receiving 8 weeks of the placebo cream versus 8 weeks of 0.075% capsaicin cream | Topical capsaicin cream significantly reduces postsurgical neuropathic pain after the first 8 weeks. It was preferred over placebo by a three-to-one margin [116]. |

| Lazzeri, M. et al. | The Journal of Urology 1996 | Prospective randomized trial | 36 patients, twice weekly treatment for 1 month, 6 months follow up | Patients receiving 10 microM intravesical capsaicin (n = 18) or placebo (n = 18) | While intravesical instillation of capsaicin was effective on frequency and nocturia in patients with the hypersensitive disorder, its effect on pain score compared to placebo was not confirmed. Possibly higher doses of capsaicin can be effective in pain control and neurological bladder disease [117]. |

| Berger, A. et al. | Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 1995 | Pilot study | 11 patients, 4–6 candies over 2–4 days, 20 min follow ups after each treatment | 6 women and five men with oral mucositis pain caused by cancer therapy received oral capsaicin (0.002–0.003 g) in a candy (taffy) vehicle | Oral capsaicin in a candy vehicle resulted in significant pain reduction. The pain relief for most patients was not complete and temporary [118]. |

| Dini, D et al. | Pain 1993 | Open-label trial | 21 (19 evaluable patients), 3 times daily treatment for 2 months, 3 months follow up | Patients with post-mastectomy pain syndrome receiving topical 0.025% capsaicin treatment | Topical capsaicin 0.025% resulted in the disappearance of all symptoms in 2 patients and a significant reduction in 11 patients. Further experimental and clinical research is recommended [119]. |

| Review Articles | |||||

| Derry, S et al. | The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017 | Systematic review of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies | 2488 | Patients with neuropathic pain receiving high-concentration (5% or more) topical capsaicin versus placebo control or 0.04% topical capsaicin as an ‘active’ placebo to help maintain blinding | Patients with HIV neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and painful diabetic neuropathy experienced moderate or substantial pain relief from high-concentration topical capsaicin compared to the control group. High-concentration capsaicin for chronic pain has similar effects to other therapies. These results should be reviewed with caution as the quality of the evidence was moderate or very low [120]. |

| Mou, J. et al. | The Clinical Journal of Pain 2014 | Meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, controlled studies | 1313 | Patients received 8% capsaicin patch (Qutenza) or a control 0.04% capsaicin patch. | Capsaicin 8% patch is effective in a high number of patients suffering from various neuropathic indications, such as postherpetic neuralgia and HIV neuropathy. Its analgesic effect starts within a few days and lasts for an average of 5 months [121]. |

| Laslett, L. L. et al. | Progress in Drug Research 2014 | Systematic review of five double-blind RCTs and one case-crossover trial of topical capsaicin | - | Topical capsaicin treatment (0.025 to 0.075% formulations) in patients with osteoarthritis versus placebo | Topical capsaicin applied four times daily in patients with clinical or radiologically diagnosed osteoarthritis and at least moderate pain results in moderately effective pain relief up to 20 weeks regardless of the application site and dosage. Topical capsaicin was well tolerated [122]. |

| Mason, L. et al. | BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2004 | Systematic review, meta-analysis of RCTs | 1024 | Adults with chronic pain from neuropathic or musculoskeletal conditions receiving topical capsaicin (0.025 to 0.075% formulations) with placebo or another treatment | Topical capsaicin has poor to moderate efficacy in treating musculoskeletal or neuropathic chronic pain. However, it can be used as a sole therapy or an adjunct in patients who are intolerant or unresponsive to other treatments [123]. |

| Author | Journal and Year of Publication | Type of Study | Number of Patients, Duration of Study | Study Groups, Active Agent and Placebo Dosage | Key Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Study | |||||

| Jiao J, et al. | Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2019 | Double-blinded, randomized, placebo controlled clinical trial | 70 patients, 4 weeks of treatment and follow-up | Patients with active rheumatoid arthritis including pain and swelling receiving TwHF cream twice a day (n = 35) versus placebo (n = 35). The TwHF cream prescription contains TwHF, Chuanxiong, liquid adjuvant Ruxiang and liquid adjuvant Moyao in proportion 4:4:2:2:1; the raw herbs dose is 4 g/mL. | The patients receiving TwHF had improvement of joint tenderness and swelling compared to the placebo group. It can be effective and safe for a patient with active rheumatoid arthritis for short-term use [124]. |

| Review Articles | |||||

| Li H, et al. | Clinical Rheumatology 2015 | Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs | 807 | Patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) receiving Tripterygium glycosides tablets (an extract of TwHF) | Based on the meta-analysis of the moderate quality clinical trials, Tripterygium glycosides tablets were not effective in treating AS [133]. |

| Cameron, M. et al. | The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011 | Systematic review | 23 | Tripterygium wilfordii to placebo and one to sulfasalazine | While T. wilfordii products can reduce some of the rheumatoid arthritis symptoms, its oral use is associated with several mild to moderate adverse effects. The adverse effects resolved after the intervention stopped [127]. |

| Canter, P. H. et al. | Phytomedicine: International Journal of Phytotherapy and Phytopharmacology 2006 | Systematic review | 105 | Patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving Tripterygium wilfordii or placebo | While T. wilfordii has beneficial effects in reducing rheumatoid arthritis symptoms, due to its association with serious adverse events, we cannot recommend its use [125]. |

| Author | Journal and Year of Publication | Type of Study | Number of Patients, Duration of Study | Study Groups, Active Agent and Placebo Dosage | Key Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pothmann, R. et al. | Headache 2005 | Multicenter prospective open-label study | 108 patients, 4 months of treatment and follow-up | Patients between the ages of 6 and 17, suffering from migraine for at least 1 year. Patients received 50 to 150 mg of the butterbur root extract depending on age for 4 months. Capsules contain extract (drug:extract radio 28:44) with a minimum of 15% petasins and pyrrolizidine alkaloids removed. | The study demonstrated that butterbur root extract is effective and well tolerated migraine prophylaxis in children and teenagers with a low rate of adverse events [144]. |

| Lipton, R. B. et al. | Neurology 2004 | Three-arm, parallel-group, randomized trial | 245 patients, 4 months of treatment and follow-up | Patient with migraine received oral Petasites extract 75 mg (n = 77), or 50 mg (n = 79), or placebo (n = 77) twice a day | Petasites extract 75 mg twice a day is well tolerated and more effective than placebo in preventing migraine. Petasites 50 mg twice a day is not significantly more effective compared to placebo [145]. |

| Diener, H. C. et al. | European Neurology 2004 | Independent reanalysis of a randomized, placebo-controlled parallel-group study | 60 patients, 12 weeks of treatment and follow-up | 33 patients treated with two butterbur capsules 25 mg twice a day and 27 patients with placebo | 45% of patients receiving butterbur capsules had improvement in migraine frequency of equal or more than 50% compared to 15% of the placebo group. This small study demonstrates butterbur can be effective and well-tolerated for migraine prophylaxis [146]. |

| Grossman, W. et al. | Alternative Medicine Review: a Journal of Clinical Therapeutic 2001 | Randomized, group-parallel, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical study | 60 patients, 12 weeks of treatment and follow-up | Patients received either Petadolex (a special Petasites hybridus extract, each capsule containing 25 mg of a CO2 extract of Petasites hybridus, n = 33) or placebo (n = 27) at a dosage of two capsules twice a day | There was a statistically significant decrease in the frequency of migraine attacks in patients receiving Petadolex compared to placebo. It was exceptionally well-tolerated with no adverse events reported. Petasites hybridus can be used as a prophylactic treatment for migraines [147]. |

| Author | Journal and Year of Publication | Type of Study | Number of Patients, Duration of Study | Study Groups, Active Agent and Placebo Dosage | Key Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Studies | |||||