Additional Value of Patient-Reported Symptom Monitoring in Cancer Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

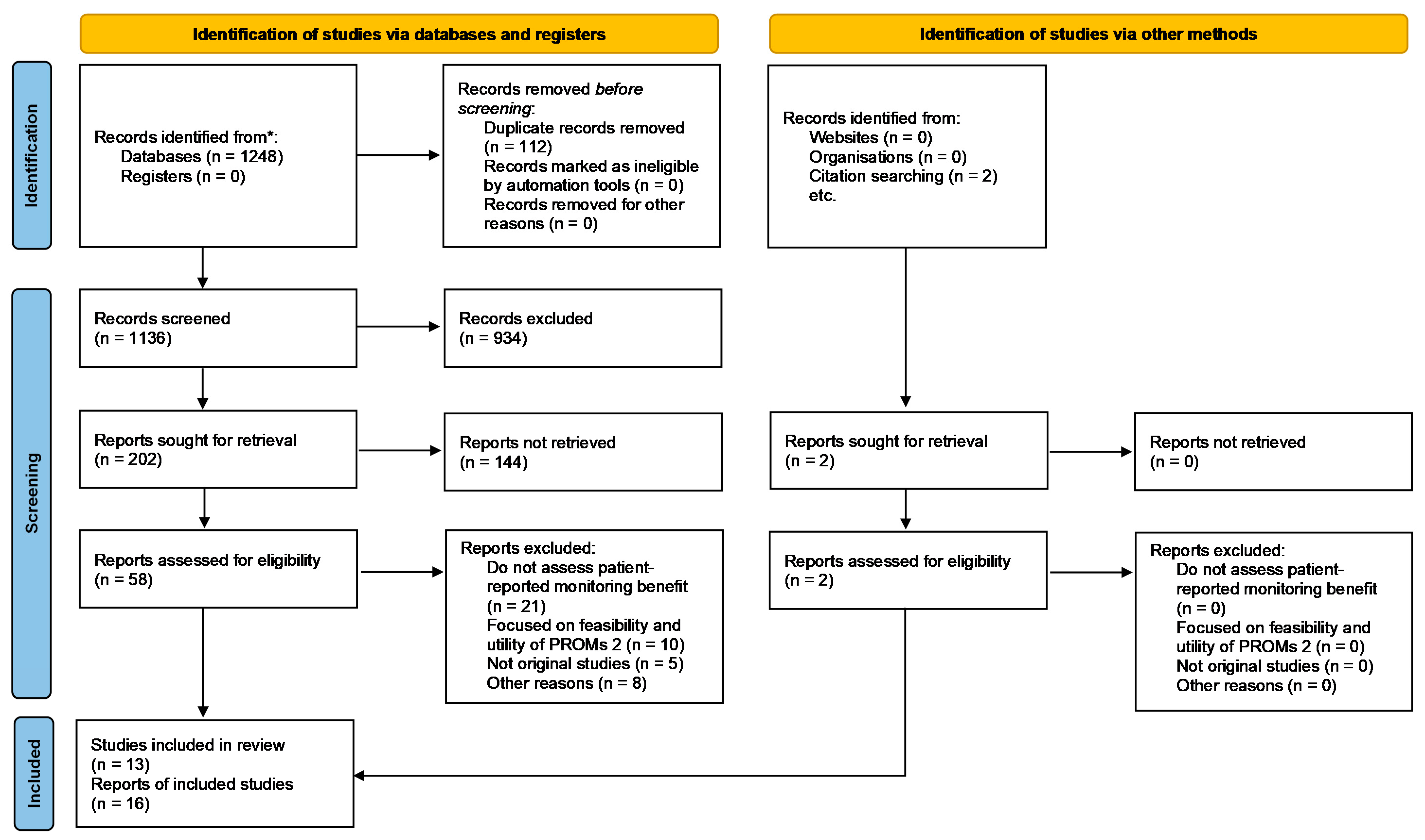

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Design

2.2. Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. General Results

| Author and Year of Publication, Country | Type of Study (a), Comparators (b) | Study Aim | Cancer Type; Sample Size | Patient-Reported Symptoms Assessed, Instrument Used and Frequency | Type of Outcome Evaluated | Summary of Results | Main Conclusion | Study Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbera et al. [28], 2020, Canada | (a) Observational retrospective cohort. (b) Cancer patients exposed (patients must have completed at least one assessment during the study) vs. not exposed to ESAS | To examine the effect of ESAS exposure on cancer patients’ overall survival | Different types of cancer (most prevalent: prostate [17.4%], breast [14.5%] and hematology [13.4%]). N = 257,786 (n = 128,893 patients exposed to ESAS matched to 128 893 cancer patients not exposed). | ESAS symptoms (pain, tiredness, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite loss, well-being, and shortness of breath). Collected before a patient’s visit via a touch screen kiosk and discussed during the clinical encounter. | Clinical outcome: probability of survival at 1, 3, and 5 years. | Probability of survival at 1 year: 81.9% vs. 76.4% Probability of survival at 3 years: 68.3% vs. 66.1% Probability of survival at 5 years: 61.9% vs. 61.4% All comparisons p < 0.0001 | Patients’ exposure to ESAS collection is associated with improved survival in cancer patients | 17/22 (STROBE) |

| Basch et al. [19], 2017, USA (research letter) | (a) Randomized clinical trial. (b) Patients at patient-reported symptom monitoring vs. usual care | To compare overall survival associated with electronic patient-reported symptom monitoring vs. usual care in cancer patients | Cancer patients initiating chemotherapy for solid metastatic tumors (various types). N = 766 patients (n = 441 intervention arm vs. n = 325 control arm). | Twelve symptoms (appetite loss, constipation, cough, diarrhea, dyspnea, dysuria, fatigue, hot flashes, nausea, pain, neuropathy, and vomiting) Symptoms were collected at or between visits via a web-based questionnaire platform (computer-experienced patients) or free standing. computer kiosks (computer-inexperienced patients). The system included email alerts to the treating oncologist | Clinical outcome: median overall survival | Median follow-up: 7 years (IQR, 6.5–7.8) Median overall Survival: 31.2 months (95% CI, 24.5–39.6) vs. 26.0 months (95% CI, 22.1–30.9) (difference, 5.2 months; p = 0.03) | Integration of patient-reported symptoms into the routine care of patients with metastatic cancer was associated with increased survival compared with usual care. | - |

| Denis et al. [23], 2019, France (research letter) | (a) Randomized clinical trial. (b) Patient-reported symptom monitoring vs. usual care | To compare overall survival associated with electronic patient-reported symptom monitoring vs. usual care in cancer patients | Patients with advanced nonprogressive stages IIA to IV lung cancer N = 121 patients (n = 60 intervention arm vs. n = 61 control arm) | Thirteen symptoms (weight, weight variation, appetite loss, weakness, pain, cough, breathlessness, depression, fever, face swelling, lump under skin, voice changing, blood in sputum). Collected weekly in an electronic form between visits. The approach included an alert email to the treating oncologist. | Clinical outcome: median overall survival | Two years of follow-up Median overall survival: 22.5 months vs. 14.9 months (difference, 7.6 months; HR: 0.59 (95% CI, 0.37–0.96); p = 0.03) | Symptom monitoring via weekly web-based patient-reported symptom monitoring treatment for lung cancer was associated with increased survival compared with standard imaging surveillance. | - |

| Basch et al. [20], 2016, USA | (a) Randomized nonblinded, clinical trial. (b) Web-based self-reporting of symptoms vs. usual care. | To test whether systematic web-based collection of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy treatment improves HRQoL and survival, quality-adjusted survival, emergency room use, and hospitalization. | Patients with metastatic breast, genitourinary, gynecologic, or lung cancer-initiating chemotherapy. N = 766 patients (n = 411 intervention arm vs. n = 325 in control arm) | Twelve symptoms (appetite loss, constipation, cough, diarrhea, dyspnea, dysuria, fatigue, hot flashes, nausea, pain, neuropathy, and vomiting) Symptoms collected at or between visits via a web-based questionnaire platform (computer-experienced patients) or free-standing computer kiosks (computer-inexperienced patients). The system included email alerts to the treating oncologist. | Patient-reported outcome: percentage of patients with HRQoL clinically meaningful improvement (≥6 points) at six months (EuroQol EQ-5D Index) Use of resources: percentage of patients who visit the emergency room and who were hospitalized. Time receiving active cancer treatment. Clinical outcome: percentage of patients alive at one year | Patient-reported outcome (HRQoL improvement [≥6 points]): 21% vs. 11% (p < 0.001) Use of resources and: visits to the emergency room (34% vs. 41%; p = 0.02), hospitalizations (45% vs. 49%; p = 0.08), time receiving treatment (mean of 8.2 months (range 0–49) vs. 6.3 months (range 0–41), respectively (p = 0.002) Clinical outcome: 75% vs. 69% patients alive at one year (difference 6%; p = 0.05) | Symptom self-reporting engages patients as active participants and may improve the experience, efficiency, and outcomes of care | 30/30 (CONSORT) |

| Nipp et al. [21], 2019, USA | (a) Randomized controlled trial (secondary analysis). (b) Usual care vs. patient-reported symptom monitoring | To explore whether age moderates the effects of an electronic symptom monitoring intervention on patients’ QoL, health care utilization, and survival outcomes. | Patients with metastatic genitourinary (32.0%), gynecologic (23.1%), or breast cancer (17.7%) initiating chemotherapy. N = 766 patients (n = 411 intervention arm g vs. n = 325 control arm) | Twelve common symptoms (appetite loss, constipation, cough, diarrhea, dyspnea, dysuria, fatigue, hot flashes, nausea, pain, neuropathy, and vomiting) Symptoms collected at or between visits via a web-based questionnaire platform (computer-literate patients) or free-standing computer kiosks (computer illiterate patients). The system included email alerts to the treating oncologist. | Effect of age (patients <70 versus ≥70 years at enrollment) on HRQoL (EuroQol EQ-5D Index); use of resources (hospitalization, emergency room visit) and survival | Patients’ age did not moderate the effects on QoL or time to first hospitalization. Median time to emergency room visit (young patients): 50.73 months for usual care vs. 21.72 months for patient-reported symptoms, p = 0.016 Decreased hazard for death for patient-reported symptoms monitoring (HR = 0.76, p = 0.011) among younger patients | Among patients with advanced cancer, age moderated the effects of an electronic symptom monitoring intervention on the risk of ER visits and survival | 18/30 (CONSORT) |

| Patel et al. [29], 2019, USA | (a) Observational study. Cancer registry (prospective and retrospective design) (b) Usual care (historical cohort) vs. Lay health worker (LHW)-led symptom screening intervention | To evaluate the effect of a LHW-led symptom screening intervention on satisfaction, self-reported overall and mental health, health care use, total costs, and survival. | Patients with stage 3 or 4 solid tumors or hematologic malignancies who were receiving care in a community oncology practice (most prevalent: gastrointestinal [27.4%], breast [20.5%] and genitourinary [16.7%]). N = 288 patients (n = 186 intervention arm vs. n = 102 control arm) | ESAS symptoms (pain, tiredness, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite loss, well-being, and shortness of breath). Symptoms were collected by a LHW (weekly for high-risk and monthly for low-risk patients) by telephone. A physician assistant reviewed symptoms daily and notified the oncology provider. | Patient-reported outcome: patients’ satisfaction with care (question no. 18) and self-reported health status (questions no. 23 and 24) of the Medicare Advantage and Prescription Drug Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. Use of resources: emergency department visits, hospital admissions, (including readmissions and intensive care unit hospitalizations), and the use of hospice services. Median cost per patient (12 months) Clinical outcome: survival during follow-up (12 months) | Patient-reported outcomes: satisfaction improvement (OR = 1.35; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.63; p = 0.002), overall health (OR: 2.23; 95% CI, 1.49 to 3.32; p = 0.001), mental or emotional Health (OR = 2.22; 95% CI: 1.46 to 3.38; p = 0.001) after 5 months postdiagnosis. Use of resources and: visits to the emergency room (0.61 [SD: 0.98] vs. 0.92 [SD: 1.53]; p = 0.03), hospitalizations (0.72 [SD: 0.96] vs. 1.02 [SD:1.44]; p = 0.03). Median total costs: €13,915.0 (IQR: €5301.3–€31,342.1) intervention vs. €20,903 (€10,308.2–€37,537.9) usual care (p = 0.01). Clinical outcome: 39% intervention vs. 28% usual care patients had died during 12-month follow-up (HR = 1.21; 95% CI, 0.78 to 1.87; p = 0.86) | The LHW-led symptom screening intervention among patients with advanced stages of cancer was associated with improved patient-reported outcomes, no differences in survival, and reduced acute care use and total health care costs. | 18/22 (STROBE) |

| De Raaf et al. [24], 2013, The Netherlands | (a) Randomized non-blinded controlled trial (b) Protocolized patient-tailored treatment (PPT) of physical symptoms vs. care as usual (CAU) | To investigate whether monitoring of physical symptoms coordinated by a nurse has a more favorable effect on fatigue severity than the symptom management included in the standard oncologic care of patients with advanced cancer. | Patients with solid malignancies in palliative care and fatigued Most prevalent: breast (36.8%), gastrointestinal (30.9%) and urogenital cancer (15.8%) N = 152 patients (n = 76 in the PPT vs. n = 76 in CAU) | Nine symptoms (pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, lack of appetite, shortness of breath, cough, and dry mouth) Collected during meetings with the nurse specialist at the outpatient clinic. When patients rated a certain symptom ≥ 4 (from 0 to 10), the nurses asked the oncologist to start an appropriate treatment using specific protocols. | Patient-reported outcome: fatigue (MFI scores at T1 = 1 month; T2 = 2 months; T3 = 3 months after random assignment). Influence of fatigue on daily life (BFI-I). Anxiety and depressed mood (HADS). | Patient-reported outcome: MFI scores: T1 (mean difference, −0.84 [SE: 0.31]; p = 0.007), T2 (mean difference, −1.14 [SE: 0.40]; p = 0.005), T3 (mean difference, −0.90 [SE, 0.50]; p = 0.07). Interference of fatigue with daily life: the PPT group reported a decrease in the interference of fatigue with daily life (maximal effect size, 0.64; p < 0.001) Anxiety: anxiety decreased in the PPT group as compared with the CAU group (maximal effect size, 0.32; p = 0.001 | In fatigued patients with advanced cancer, nurse-led monitoring and protocolized treatment of physical symptoms are effective in alleviating fatigue | 29/30 (CONSORT) |

| Diplock et al. [30], 2019, Canada | (a) Prospective observational study (b) Cancer patients screened prior to and after ESAS implementation | To assess the impact of implementing ESAS screening on HRQoL and patient satisfaction with care in ambulatory oncology patients. | Ambulatory oncology patients. Most prevalent: breast (25.4%), hematologic oncology (16.8%) and head and neck cancer (16.4%) N = 268 patients (n = 160 prior to ESAS site implementation vs. n = 108 after ESAS implementation) | ESAS symptoms (pain, tiredness, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite loss, well-being, and shortness of breath). ESAS was collected via a touch screen kiosk (at baseline (T1), and two weeks later (T2)) | Patient-reported outcome: HRQoL (EORTC-QLQ-C30). Patients’ satisfaction with care (PMH/PSQ-MD-24 and EORTC-OUTPATSAT35 RT and CT) | No significant differences between HRQoL and satisfaction outcomes from the matched non-ESAS and ESAS groups (at T1 and T2) Nausea and Vomiting punctuations significantly decreased over time: mean 10.75 (SD: 19.40) prior to ESAS, mean 7.44 (SD: 12.96) at T1 and mean 8.13 (SD: 14.64) at T2 Constipation: mean 28.08 (SD: 32.23) prior to ESAS, mean 13.28 (SD: 21.51) at T1 and mean 10.60 (SD: 18.50) at T2 | There was no impact of early-ESAS screening on HRQoL or satisfaction outcomes | 16/22 (STROBE) |

| Baratelli et al. [31], 2019, Italy | (a) Observational, prospective cohort (b) Usual care vs. patient-reported symptoms | To compare two groups of patients: a first group, visited using the usual modality of toxicity and symptoms collection and management, and a second group, visited after the introduction of patient-based assessment of symptoms and toxicities in routine clinical practice | Cancer patients receiving active anti-cancer treatment as outpatients. Most prevalent colorectal cancer (32.7%), lung cancer (19.9%), and pancreatic cancer (14.7%) N = 211 (n = 119 usual care vs. n = 92 patient-reported symptoms patients) | Thirteen symptoms (mouth problems, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, dyspnea, skin problems, nail problems, itching, hand/foot problems, fatigue, pain, and other issues) Symptoms collected by a nurse before each visit and were paper based. They were delivered to the physician, who could consult them before the visit. | Patient-reported outcome: HRQoL (mean change from baseline to 1 month of (EORTC-QLQ-C30) scores) | Patient-reported outcome: mean change from baseline of global QoL was −1.68 (SE: 1.88) for usual care vs. 2.54 (SE: 2.32) in patient-reported symptoms (p = 0.004). | Introduction of patient-reported symptom monitoring in clinical practice produced a significant QoL improvement compared to the traditional modality of visit. | 17/22 (STROBE) |

| Strasser et al. [25] 2016, Switzerland | (a) Multicenter cluster randomized clinical trial (b) Patient-reported symptoms and monitoring vs. usual care | To test the effects of the E-MOSAIC intervention (patient-reported symptoms and monitoring) in patients with incurable cancer getting a new line of chemotherapy with palliative intent. | Patients received anticancer treatment with palliative intent Most prevalent non-small-cell lung cancer. (18.9%), colorectal cancer (14.4%) and breast cancer (10.2%) N = 264 (n= 119 usual care vs. n = 145 patient-reported symptoms patients) | ESAS symptoms, and three additional outcomes (estimated nutritional intake, body weight change, and Karnofsky performance) Electronic patient-reported symptoms collected weekly. In the intervention group, longitudinal monitoring sheet was printed and was immediately given to the oncologists. | Patient-reported outcome: HRQoL (mean change from baseline to 6 weeks of (G-QoL) scores for EORTC-QLQ-C30; difference between the arms) | Patient-reported outcome: the difference in HRQoL between arms was 6.84 (−1.65, 15.33) (p = 0.1) in favor of the intervention arm | Monitoring of patient symptoms, clinical syndromes, and their management clearly reduced patients’ symptoms, and QoL (although the difference was not statistically significant) | 30/30 (CONSORT) |

| Kneuertz et al. [32], 2020, USA | (a) Observational prospective pilot study (b) One arm | To understand the utility of a mobile application platform to engage patients whilst gathering data on patient compliance, perioperative experience and satisfaction. | Patients diagnosed with lung cancer who were scheduled for robotic surgery N = 50 patients | Post-discharge recovery assessment of pain, anxiety and mood. Social role functioning and return to work Collected daily (pain, anxiety and mood) and at days 14 and 30 post-discharge (social role functioning and return to work) through a mobile application. The care team had access to patients’ reports. | Patient-reported outcome: satisfaction with their hospital stay (ad-hoc questionnaire) | Patient-reported outcome: 77.4% of patients gave the highest-ranking (“excellent”) for the care received, and 93.5% reported they would recommend the hospital to others based on their experience | A mobile device platform may serve as an effective mechanism to record perioperative patient-reported symptoms and satisfaction while facilitating patient-provider engagement in perioperative care. | 17/22 (STROBE) |

| Riis et al. [26], 2020, Denmark | (a) Pilot randomized controlled trial. (b) standard follow-up care vs. individualized follow-up care | To evaluate the patients’ satisfaction with the care provided when using electronic patient-reported symptom monitoring to individualize follow-up care in women with early breast cancer receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. | Postmenopausal women with early breast cancer receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. N = 134 (n = 64 standard follow-up care vs. n = 60 individualized follow-up care) | Quality of life (EORTC QLQ-C30), including three symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and pain), and six single items (appetite loss, diarrhea, dyspnea, constipation, insomnia, financial impact) Collected every third month over a two-year period electronically. The principal investigator monitored incoming questionnaires. | Patient-reported outcomes: satisfaction with the care provided as measured by four items from the PEQ. Secondary outcomes were use of consultations and adherence to treatment (collected every third month over a two-year period. | Satisfaction with follow-up care and adherence: no statistically significant differences between standard follow-up care vs. individualized follow-up care. Use of resources: patients in standard care attended 4.3: (CI 3.9–4.7) consultations each vs. 2.1 (CI: 1.6–2.6) in patients attending individualized care (p < 0.001). | A significant reduction in consultations was observed for the group attending individualized care without compromising the patients’ satisfaction, quality of life, or adherence to treatment | 24/30 (CONSORT) |

| Nipp et al. [27], 2019, USA | (a) Nonblinded, pilot randomized controlled trial. (b) Usual care vs. patient-reported symptom monitoring. | To assess the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of symptom monitoring for improving symptom burden and health care utilization among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. | Hospitalized patients with advanced cancer admitted to oncology service. Most prevalent: gastrointestinal (36.6%), lung (22%) and head and neck cancer (10%) N = 150 patients (n = 75 in the patient-reported symptoms monitoring vs. n = 75 in usual care arm) | Physical symptoms (pain, fatigue, drowsiness, nausea, appetite loss, dyspnea, constipation, and diarrhea) Psychological symptoms (depression, anxiety, and well-being) Collected daily using tablet computers. Study staff presented patients’ reports each day to the clinical staff. | Use of resources and cost outcomes: hospital length of stay, time to first unplanned readmission within 30 days. | No significant difference in patients’ hospital length of stay (B = 0.16, 95% CI: −1.67–1.99; p = 0.862). Patients assigned to symptom monitoring had a lower risk of readmissions (HR = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.37–1.26; p = 0.224). | Intervention patients had lower readmission risk, although this difference was not significant. | 27/30 (CONSORT) |

| Howell et al. [33], 2020, Canada | (a) Observational prospective study (b) Usual care vs. patient-reported symptom monitoring | To determine if there was a difference in relative rates for emergency department visits and hospitalizations for the iPEHOC (Improving Patient Experience and Health Outcomes Collaborative intervention) exposed population compared with contemporaneous controls | Different types of cancer. Most prevalent: prostate cancer (16%), breast cancer (14.9%), and gynecological cancer (8.7%) N = 129,797 (pre-intervention n = 70,854 and intervention group n = 58,943) | The iPEHOC intervention included patient-reported symptoms collection through an electronic system in addition to clinicians’ and patients’ educational interventions. ESAS symptoms (pain, tiredness, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite loss, well-being, and shortness of breath) In addition, Brief Pain Inventory, the Cancer Fatigue Scale, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder, and the PHQ-9 | Use of resources and cost outcomes: emergency department visits, hospitalization rates and drug prescriptions for each clinic (expressed as difference in difference (DID) approach). | Use of resources: DID = −0.223 in the RR for emergency department visits for the intervention compared with controls over time (0.947, CI 0.900–0.996). There was also lower DID in palliative care visits (−0.0097), psychosocial oncology visits (−0.0248) and antidepressant prescriptions in the exposed population compared with controls. | Facilitating uptake of patient-reported symptoms data may impact healthcare utilization. | 19/22 (STROBE) |

| Lizee et al. [22] 2019, France | (a) Economic evaluation based on the data from a multicenter randomized clinical trial (b) Usual care vs. patient-reported symptom monitoring | To assess and compare the overall cost of surveillance in the patient-reported symptom monitoring and control arms. To assess the cost-effectiveness of this surveillance based on web-based patient-reported symptom monitoring, compared to conventional surveillance. | Patients with advanced non-progressive stages IIA to IV lung cancer N = 121 patients (n = 60 in the patient-reported symptoms monitoring vs. n = 61 in the usual care arm) | Thirteen symptoms (weight, weight variation, appetite loss, weakness, pain, cough, breathlessness, depression, fever, face swelling, lump under skin, voice changing, blood in sputum). Collected weekly by patients in an electronic form. The PRO system automatically triggered an alert email to the Treating. | Use of resources and cost outcomes: average annual cost per patient, including the following use of resources (consultation, imaging, trip, conventional follow-up (including the e-PRO system-related costs in the experimental arm)) Cost–utility analysis (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per life-year gained and per QALY) | Use of resources: average annual cost of surveillance follow-up was (€2828.1/year/patient) compared to control (€1129.2/year/patient). The patient-reported symptom monitoring approach presented an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of €10,500.9 per life-year gained and €18,107.9 per QALY (cost-effective) | Surveillance of lung cancer patients using web-based patient-reported symptom monitoring reduced the follow-up costs and represented a cost-effective strategy. | 23/24 (CHEERS) |

| Nixon et al. [34] 2018, Canada | (a) Economic evaluation based on the data from a randomized nonblinded, clinical trial (b) Usual care vs. patient-reported symptom monitoring | To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of a patient reported outcome tool for symptom monitoring in patients undergoing treatment for advanced or metastatic cancer compared to standard of care symptom monitoring from the perspective of the public payer in Alberta. | Patients with metastatic solid tumors receiving systemic therapy | Twelve symptoms (appetite loss, constipation, cough, diarrhea, dyspnea, dysuria, fatigue, hot flashes, nausea, pain, neuropathy, and vomiting) Symptoms collected at or between visits via a web-based questionnaire platform (computer-experienced patients) or free-standing computer kiosks (computer-inexperienced patients). The system included email alerts to the treating oncologist. | Cost–utility analysis (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per life-year gained and per QALY) | The patient-reported symptom monitoring approach presented an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of €7575.9 per QALY (cost-effective) | The use of a PRO tool for symptom monitoring yields a cost per QALY of €7575.9 that would be considered a good value for money at the typically accepted Canadian standard of $50,000 (€28,163.2) per QALY | 21/24 (CHEERS) |

3.2. Impact of Patient-Reported Symptoms on Health Outcomes

3.2.1. Overall Survival

3.2.2. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

3.2.3. Patient-Reported Satisfaction

3.2.4. Patient-Reported Fatigue

3.2.5. Adherence

3.2.6. Economic Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Other Implications of Patient-Reported Symptom Monitoring

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henry, D.H.; Viswanathan, H.N.; Elkin, E.P.; Traina, S.; Wade, S.; Cella, D. Symptoms and treatment burden associated with cancer treatment: Results from a cross-sectional national survey in the U.S. Support. Care Cancer 2008, 16, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromme, E.K.; Eilers, K.M.; Mori, M.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Beer, T.M. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 3485–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugsand, E.A.; Sprangers, M.A.; Bjordal, K.; Skorpen, F.; Kaasa, S.; Klepstad, P. Health care providers underestimate symptom intensities of cancer patients: A multicenter European study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, B.C.; Aschebrook-Kilfoy, B.; White, M.G.; Applewhite, M.K.; Kaplan, S.P.; Angelos, P.; Kaplan, E.L.; Grogan, R.H. Quality of life in thyroid cancer-assessment of physician perceptions. J. Surg. Res. 2018, 226, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.E.; Angen, M.; Cullum, J.; Goodey, E.; Koopmans, J.; Lamont, L.; MacRae, J.H.; Martin, M.; Pelletier, G.; Robinson, J.; et al. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer. 2004, 90, 2297–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleeland, C.S. Cancer-related symptoms. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2000, 10, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R.; Haddad, F.G.; Kourie, H.R.; Kattan, J. Electronic patient-reported outcomes: A revolutionary strategy in cancer care. Future Oncol. 2017, 13, 2397–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Riis, C.L.; Bechmann, T.; Jensen, P.T.; Coulter, A.; Steffensen, K.D. Are patient-reported outcomes useful in post-treatment follow-up care for women with early breast cancer? A scoping review. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2019, 10, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotronoulas, G.; Kearney, N.; Maguire, R.; Harrow, A.; Di Domenico, D.; Croy, S.; MacGillivray, S. What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1480–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, D.; Molloy, S.; Wilkinson, K.; Green, E.; Orchard, K.; Wang, K.; Liberty, J. Patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer clinical practice: A scoping review of use, impact on health outcomes, and implementation factors. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1846–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ou, L.; Hollis, S.J. A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organisations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graupner, C.; Kimman, M.L.; Mul, S.; Slok, A.H.; Claessens, D.; Kleijnen, J.; Dirksen, C.D.; Breukink, S.O. Patient outcomes, patient experiences and process indicators associated with the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in cancer care: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available online: http:training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v5.1/ (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int. J. Surg. 2011, 9, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; Strobe Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, W163–W194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Husereau, D.; Drummond, M.; Petrou, S.; Carswell, C.; Moher, D.; Greenberg, D.; Augustovski, F.; Briggs, A.H.; Mauskopf, J.; Loder, E. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2013, 14, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group (CCEMG), Evidence for Polilcy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre). CCEMG -EPPI -Centre Cost Converter. Available online: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/default.aspx (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Basch, E.; Deal, A.M.; Dueck, A.C.; Scher, H.I.; Kris, M.G.; Hudis, C.; Schrag, D. Overall Survival Results of a Trial Assessing Patient-Reported Outcomes for Symptom Monitoring During Routine Cancer Treatment. JAMA 2017, 318, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basch, E.; Deal, A.M.; Kris, M.G.; Scher, H.I.; Hudis, C.A.; Sabbatini, P.; Rogak, L.; Bennett, A.V.; Dueck, A.C.; Atkinson, T.M.; et al. Symptom Monitoring With Patient-Reported Outcomes During Routine Cancer Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipp, R.D.; Horick, N.K.; Deal, A.M.; Rogak, L.J.; Fuh, C.; Greer, J.A.; Dueck, A.C.; Basch, E.; Temel, J.S.; El-Jawahri, A. Differential effects of an electronic symptom monitoring intervention based on the age of patients with advanced cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizée, T.; Basch, E.; Trémolières, P.; Voog, E.; Domont, J.; Peyraga, G.; Urban, T.; Bennouna, J.; Septans, A.L.; Balavoine, M.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Web-Based Patient-Reported Outcome Surveillance in Patients With Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, F.; Basch, E.; Septans, A.L.; Bennouna, J.; Urban, T.; Dueck, A.C.; Letellier, C. Two-Year Survival Comparing Web-Based Symptom Monitoring vs. Routine Surveillance Following Treatment for Lung Cancer. JAMA 2019, 321, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Raaf, P.J.; de Klerk, C.; Timman, R.; Busschbach, J.J.; Oldenmenger, W.H.; van der Rijt, C.C. Systematic monitoring and treatment of physical symptoms to alleviate fatigue in patients with advanced cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, F.; Blum, D.; Von Moos, R.; Cathomas, R.; Ribi, K.; Aebi, S.; Betticher, D.; Hayoz, S.; Klingbiel, D.; Brauchli, P.; et al. The effect of real-time electronic monitoring of patient-reported symptoms and clinical syndromes in outpatient workflow of medical oncologists: E-MOSAIC, a multicenter cluster-randomized phase III study (SAKK 95/06). Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riis, C.L.; Jensen, P.T.; Bechmann, T.; Möller, S.; Coulter, A.; Steffensen, K.D. Satisfaction with care and adherence to treatment when using patient reported outcomes to individualize follow-up care for women with early breast cancer—A pilot randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncol. 2020, 59, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nipp, R.D.; El-Jawahri, A.; Ruddy, M.; Fuh, C.; Temel, B.; D’Arpino, S.M.; Cashavelly, B.J.; Jackson, V.A.; Ryan, D.P.; Hochberg, E.P.; et al. Pilot randomized trial of an electronic symptom monitoring intervention for hospitalized patients with cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019, 30, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barbera, L.; Sutradhar, R.; Seow, H.; Mittmann, N.; Howell, D.; Earle, C.C.; Li, Q.; Thiruchelvam, D. The impact of routine Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) use on overall survival in cancer patients: Results of a population-based retrospective matched cohort analysis. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 7107–7115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.I.; Ramirez, D.; Agajanian, R.; Agajanian, H.; Bhattacharya, J.; Bundorf, K.M. Lay Health Worker-Led Cancer Symptom Screening Intervention and the Effect on Patient-Reported Satisfaction, Health Status, Health Care Use, and Total Costs: Results From a Tri-Part Collaboration. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e19–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diplock, B.D.; McGarragle, K.M.; Mueller, W.A.; Haddad, S.; Ehrlich, R.; Yoon, D.H.A.; Cao, X.; Al-Allaq, Y.; Karanicolas, P.; Fitch, M.I.; et al. The impact of automated screening with Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) on health-related quality of life, supportive care needs, and patient satisfaction with care in 268 ambulatory cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baratelli, C.; Turco, C.G.C.; Lacidogna, G.; Sperti, E.; Vignani, F.; Marino, D.; Zichi, C.; De Luca, E.; Audisio, M.; Ballaminut, D.; et al. The role of patient-reported outcomes in outpatients receiving active anti-cancer treatment: Impact on patients’ quality of life. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 4697–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneuertz, P.J.; Jagadesh, N.; Perkins, A.; Fitzgerald, M.; Moffatt-Bruce, S.D.; Merritt, R.E.; D’Souza, D.M. Improving patient engagement, adherence, and satisfaction in lung cancer surgery with implementation of a mobile device platform for patient reported outcomes. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 6883–6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, D.; Li, M.; Sutradhar, R.; Gu, S.; Iqbal, J.; O’Brien, M.A.; Seow, H.; Dudgeon, D.; Atzema, C.; Earle, C.C.; et al. Integration of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) for personalized symptom management in “real-world” oncology practices: A population-based cohort comparison study of impact on healthcare utilization. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 4933–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon NAS, E.; Clement, F.; Verma, S.; Manns, B. Cost-effectiveness of symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment. J. Cancer Policy 2018, 15, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijpers, W.; Groen, W.G.; Loos, R.; Oldenburg, H.S.; Wouters, M.W.; Aaronson, N.K.; van Harten, W.H. An interactive portal to empower cancer survivors: A qualitative study on user expectations. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 2535–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mooney, K.H.; Beck, S.L.; Friedman, R.H.; Farzanfar, R. Telephone-linked care for cancer symptom monitoring: A pilot study. Cancer Pract. 2002, 10, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.A.; Klasnja, P.; Hartzler, A.; Unruh, K.T.; Pratt, W. Probing the benefits of real-time tracking during cancer care. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2012, 2012, 1340–1349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mark, T.L.; Fortner, B.; Johnson, G. Evaluation of a tablet PC technology to screen and educate oncology patients. Support. Care Cancer 2008, 16, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, E.E.; Keding, A.; Awad, N.; Hofmann, U.; Campbell, L.J.; Selby, P.J.; Brown, J.M.; Velikova, G. Impact of patient-reported outcomes in oncology: A longitudinal analysis of patient-physician communication. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2910–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, G.; Keding, A.; Harley, C.; Cocks, K.; Booth, L.; Smith, A.B.; Wright, P.; Selby, P.J.; Brown, J.M. Patients report improvements in continuity of care when quality of life assessments are used routinely in oncology practice: Secondary outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 2381–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lynch, J.; Goodhart, F.; Saunders, Y.; O’Connor, S.J. Screening for psychological distress in patients with lung cancer: Results of a clinical audit evaluating the use of the patient Distress Thermometer. Support. Care Cancer 2010, 19, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Inclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Population | Cancer patients (any type and stage) |

| Intervention | Patient-reported symptom monitoring, regardless of the modality: paper-based or electronic |

| Comparator | - |

| Outcome | Health results as clinical (e.g., survival), patient-reported (e.g., HRQoL, general perception or feelings of well-being, satisfaction), or economic (use of healthcare resources, costs, cost-effectiveness) outcomes |

| Study Design | Original articles |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lizán, L.; Pérez-Carbonell, L.; Comellas, M. Additional Value of Patient-Reported Symptom Monitoring in Cancer Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cancers 2021, 13, 4615. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13184615

Lizán L, Pérez-Carbonell L, Comellas M. Additional Value of Patient-Reported Symptom Monitoring in Cancer Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cancers. 2021; 13(18):4615. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13184615

Chicago/Turabian StyleLizán, Luís, Lucía Pérez-Carbonell, and Marta Comellas. 2021. "Additional Value of Patient-Reported Symptom Monitoring in Cancer Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature" Cancers 13, no. 18: 4615. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13184615

APA StyleLizán, L., Pérez-Carbonell, L., & Comellas, M. (2021). Additional Value of Patient-Reported Symptom Monitoring in Cancer Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cancers, 13(18), 4615. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13184615