Valgus Arthritic Knee Responds Better to Conservative Treatment than the Varus Arthritic Knee

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

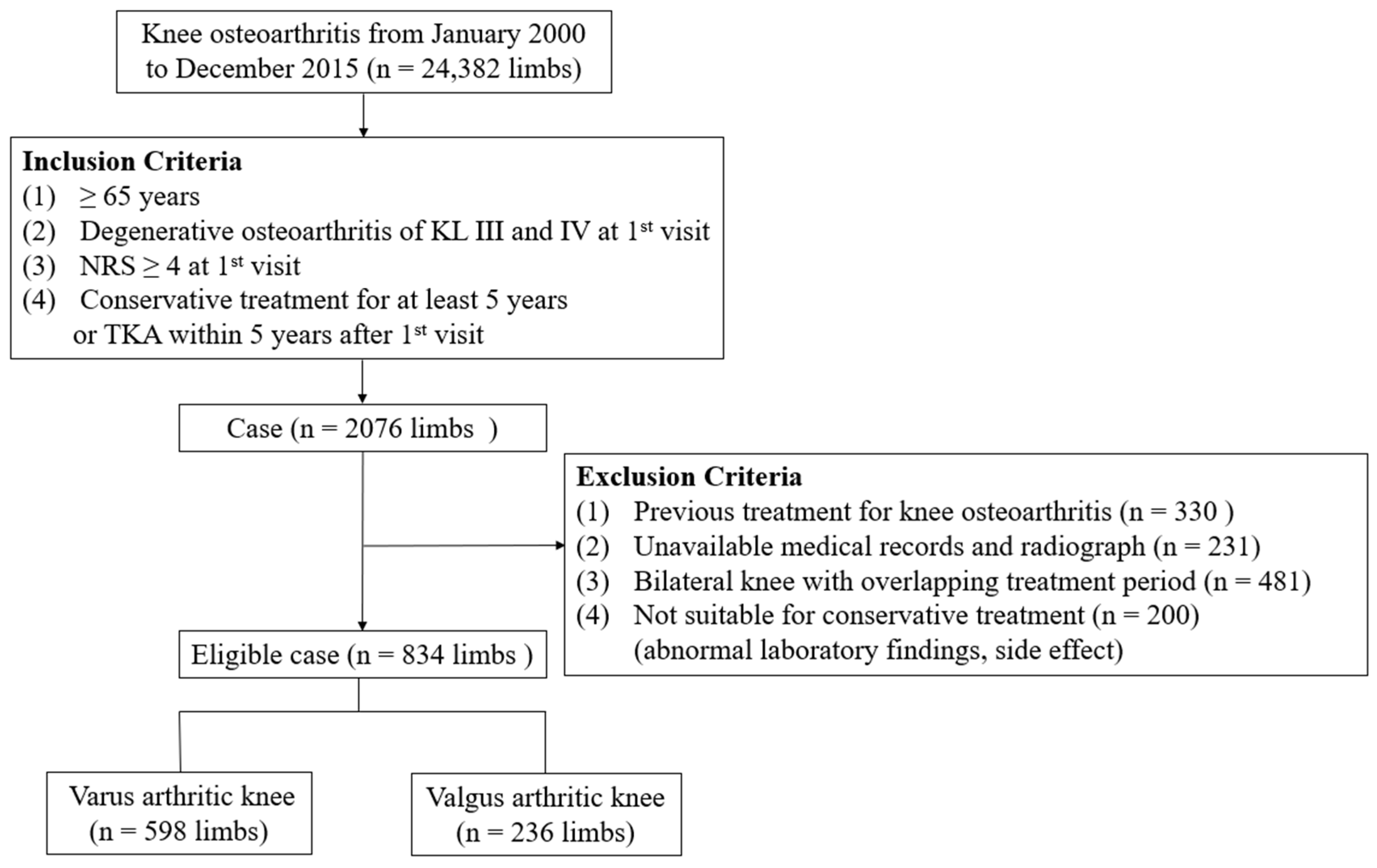

2.1. Participants

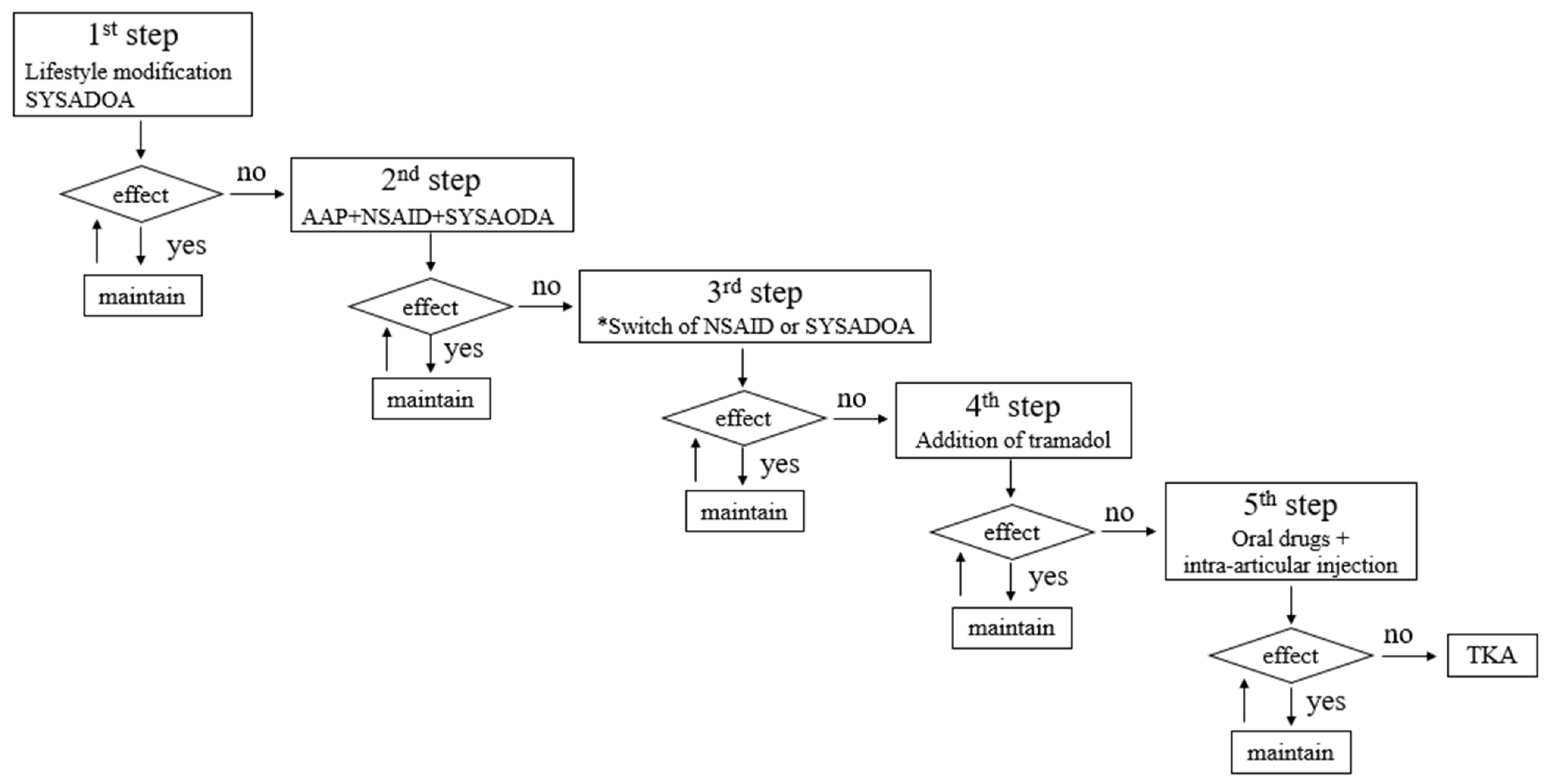

2.2. Patient Treatment Protocol

2.3. Radiographic Examination

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

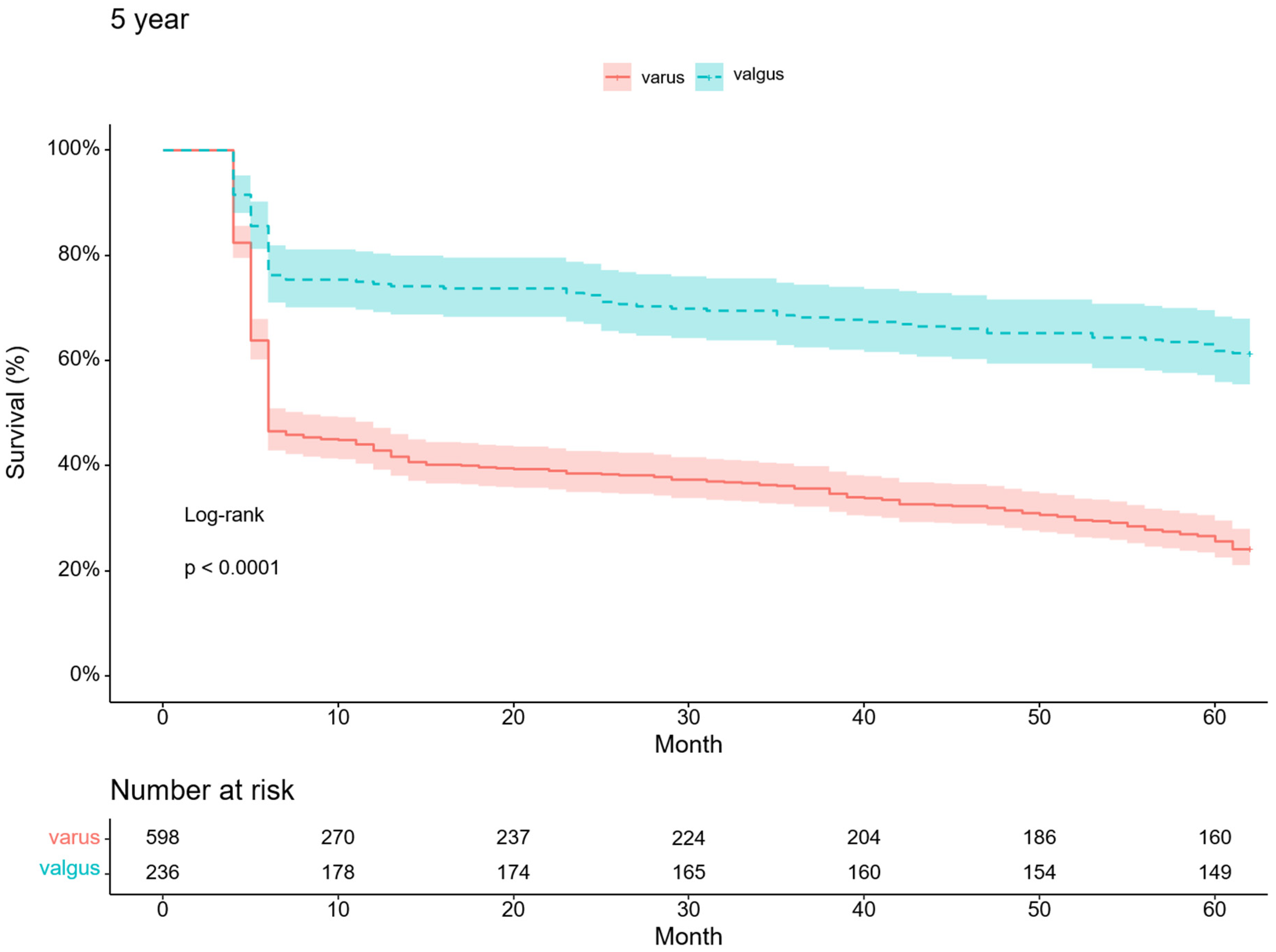

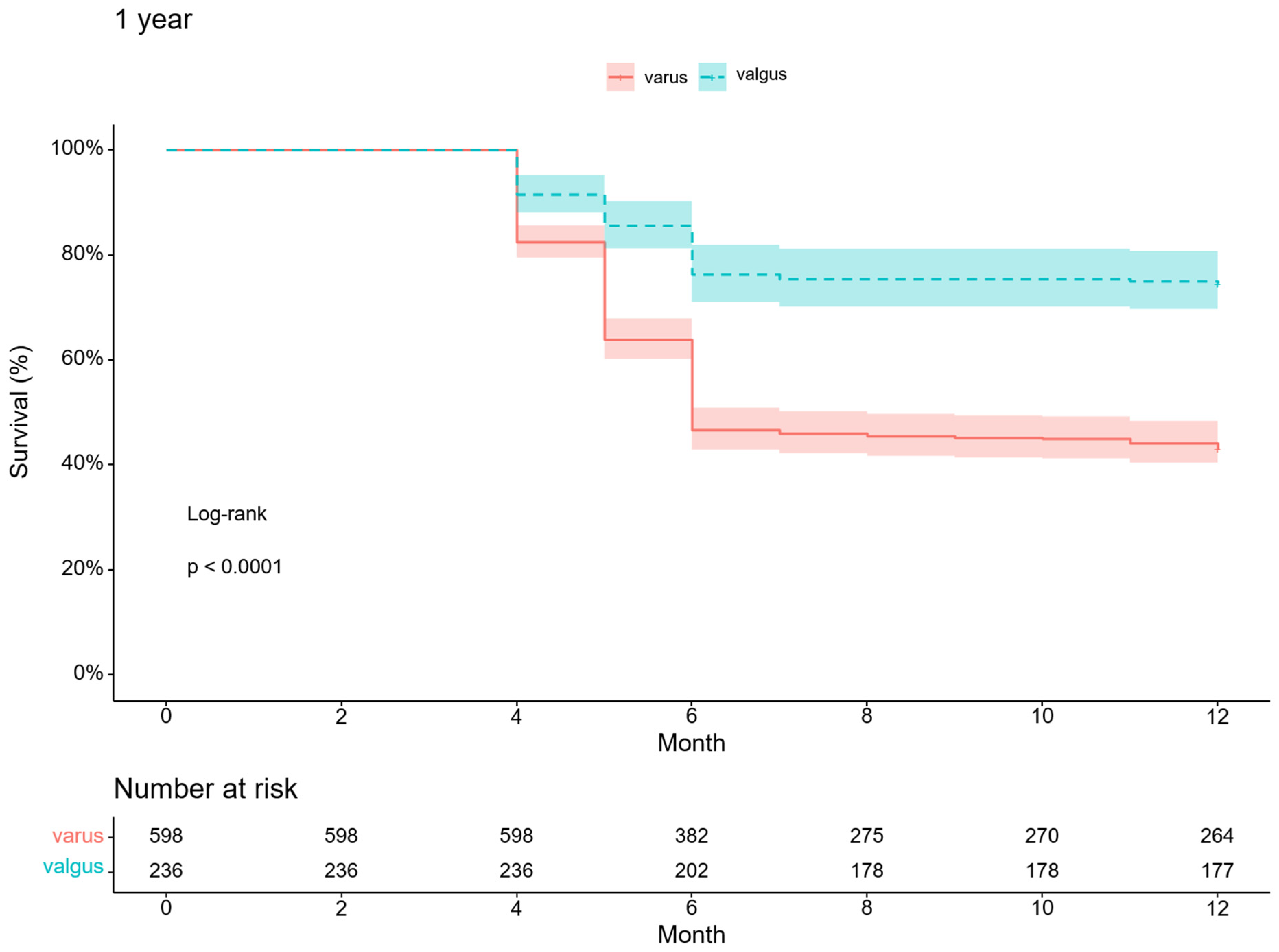

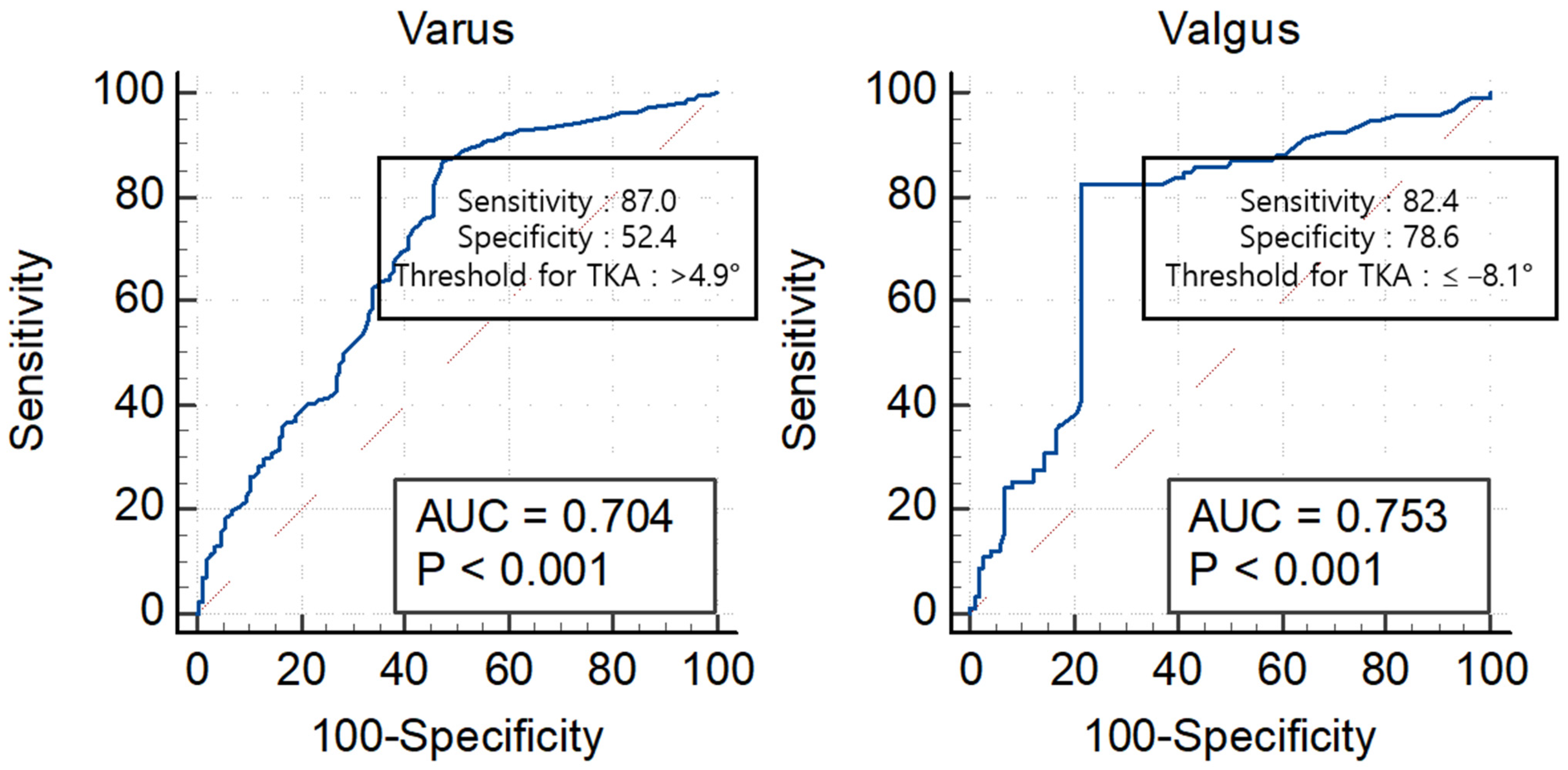

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, J.A.; Yu, S.; Chen, L.; Cleveland, J.D. Rates of Total Joint Replacement in the United States: Future Projections to 2020-2040 Using the National Inpatient Sample. J. Rheumatol. 2019, 46, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.W.; Kang, S.B.; Chang, C.B.; Moon, S.Y.; Lee, Y.K.; Koo, K.H. Current Trends and Projected Burden of Primary and Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty in Korea Between 2010 and 2030. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, R.B.; Maloney, W.J.; Wright, J.G. An AOA critical issue. The outcome of the outcomes movement. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2004, 86, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Gross, D.; Lane, N.E.; Lu, N.; Wang, M.; Zeng, C.; Yang, T.; Lei, G.; Choi, H.K.; Zhang, Y. Risk factor heterogeneity for medial and lateral compartment knee osteoarthritis: Analysis of two prospective cohorts. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2019, 27, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, R.; Rosso, F.; Cottino, U.; Dettoni, F.; Bonasia, D.E.; Bruzzone, M. Total knee arthroplasty in the valgus knee. Int. Orthop. 2014, 38, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Chmiel, J.S.; Almagor, O.; Felson, D.; Guermazi, A.; Roemer, F.; Lewis, C.E.; Segal, N.; Torner, J.; Cooke, T.D.V.; et al. The role of varus and valgus alignment in the initial development of knee cartilage damage by MRI: The MOST study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Song, J.; Dunlop, D.; Felson, D.; Lewis, C.E.; Segal, N.; Torner, J.; Cooke, T.D.V.; Hietpas, J.; Lynch, J.; et al. Varus and valgus alignment and incident and progressive knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1940–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, F.; Leitl, S.; Waugh, W. The distribution of load across the knee. A comparison of static and dynamic measurements. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1980, 62, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, G.M.; van Tol, A.W.; Bergink, A.P.; Belo, J.N.; Bernsen, R.M.; Reijman, M.; Pols, H.A.P.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A. Association between valgus and varus alignment and the development and progression of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, M.; Felson, D.T.; Guermazi, A.; Roemer, F.W.; Wang, K.; Crema, M.D.; Lynch, J.A.; Sharma, L.; Segal, N.A.; Lewis, C.E.; et al. Risk factors for medial meniscal pathology on knee MRI in older US adults: A multicentre prospective cohort study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 1733–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Song, J.; Felson, D.T.; Cahue, S.; Shamiyeh, E.; Dunlop, D.D. The role of knee alignment in disease progression and functional decline in knee osteoarthritis. JAMA 2001, 286, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellgren, J.H.; Lawrence, J.S. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1957, 16, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snijders, G.F.; den Broeder, A.A.; van Riel, P.L.; Straten, V.H.; de Man, F.H.; van den Hoogen, F.H.; van den Ende, C.H.M.; NOAC Study Group. Evidence-based tailored conservative treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis: Between knowing and doing. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2011, 40, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths-Jones, W.; Chen, D.B.; Harris, I.A.; Bellemans, J.; MacDessi, S.J. Arithmetic hip-knee-ankle angle (aHKA): An algorithm for estimating constitutional lower limb alignment in the arthritic patient population. Bone Jt. Open 2021, 2, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Cui, J.; Xie, K.; Jiang, X.; He, Z.; Du, J.; Chu, L.; Qu, X.; Ai, S.; Sun, Q.; et al. Association between knee alignment, osteoarthritis disease severity, and subchondral trabecular bone microarchitecture in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2020, 22, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steadman, J.R.; Briggs, K.K.; Matheny, L.M.; Ellis, H.B. Ten-year survivorship after knee arthroscopy in patients with Kellgren-Lawrence grade 3 and grade 4 osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthroscopy 2013, 29, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandrekar, J.N. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 1315–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biau, D.J.; Kernéis, S.; Porcher, R. Statistics in brief: The importance of sample size in the planning and interpretation of medical research. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008, 466, 2282–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.E.; Howie, C.R.; MacDonald, D.; Biant, L.C. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: A prospective study of 1217 patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2010, 92, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, A.; Lee, G.C. Establishing Realistic Patient Expectations Following Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2015, 23, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, W.B.; Al-Dadah, O. Conservative treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A review of the literature. World J. Orthop. 2022, 13, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriacchi, T.P. Dynamics of knee malalignment. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 1994, 25, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzner, I.; Bender, A.; Dymke, J.; Duda, G.; von Roth, P.; Bergmann, G. Mediolateral force distribution at the knee joint shifts across activities and is driven by tibiofemoral alignment. Bone Jt. J. 2017, 99b, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felson, D.T.; Niu, J.; Gross, K.D.; Englund, M.; Sharma, L.; Cooke, T.D.; Guermazi, A.; Roemer, F.W.; Segal, N.; Goggins, J.M.; et al. Valgus malalignment is a risk factor for lateral knee osteoarthritis incidence and progression: Findings from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study and the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lengsfeld, M.; Rudig, L.; von Issendorff, W.D.; Koebke, J. Significance of shape differences between medial and lateral knee joint menisci for functional change of position. Unfallchirurgie 1991, 17, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.F.; Hubbard, J.B. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Knee Lateral Meniscus; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Tampa, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pinskerova, V.; Samuelson, K.M.; Stammers, J.; Maruthainar, K.; Sosna, A.; Freeman, M.A. The knee in full flexion: An anatomical study. J Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2009, 91, 830–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedunchezhiyan, U.; Varughese, I.; Sun, A.R.; Wu, X.; Crawford, R.; Prasadam, I. Obesity, Inflammation, and Immune System in Osteoarthritis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 907750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.S.; Wilkie, W.A.; Remily, E.A.; Dávila Castrodad, I.M.; Jean-Pierre, M.; Jean-Pierre, N.; Gbadamosi, W.A.; Halik, A.K.; Delanois, R.E. The Rise of Obesity among Total Knee Arthroplasty Patients. J. Knee Surg. 2022, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intra-Observer Reliability | Inter-Observer Reliability | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HKA | 0.952 (0.910–0.975) | 0.948 (0.900–0.973) | p < 0.001 |

| KL grade | 0.998 (0.997–0.999) | 0.973 (0.948–0.986) | p < 0.001 |

| 1st Visit | Varus Arthritic Knee (n = 598) | Valgus Arthritic Knee (n = 236) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variable | |||

| Age (years) | 74.5 ± 8.4 | 73.3 ± 9.4 | 0.400 * |

| Gender (female/male) | 343/255 | 142/94 | 0.154 † |

| Height (cm) | 159.5 ± 9.0 | 160.2 ± 8.8 | 0.699 * |

| Weight (kg) | 65.5 ± 12.0 | 67.0 ± 12.0 | 0.113 * |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 ± 3.5 | 26.1 ± 3.5 | 0.100 * |

| Laterality (Rt/Lt) | 288/310 | 124/111 | 0.138 † |

| Onset of symptom (months) | 34.7 ± 14.3 | 36.1 ± 25.3 | 0.897 * |

| NRS (scale) | 6.7 ± 2.3 | 6.1 ± 2.1 | 0.689 * |

| Radiographic variable | |||

| KL grade (III/IV) | 380/218 | 155/81 | 0.563 * |

| HKA | 6.4 ± 4.8 | −6.5 ± 3.7 | <0.001 * |

| Survival Probability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthritic Knee | 1-year | 2-year | 3-year | 4-year | 5-year |

| Varus (n = 598) (n, %) | 257 (43) | 231 (38.6) | 214 (35.8) | 189 (31.6) | 145 (24.2) |

| Valgus (n = 236) (n, %) | 176 (74.6) | 171 (72.5) | 161 (68.2) | 154 (65.3) | 145 (61.4) |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.; Yoon, J.; Chang, C. Valgus Arthritic Knee Responds Better to Conservative Treatment than the Varus Arthritic Knee. Medicina 2023, 59, 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59040779

Lee S, Choi Y, Lee J, Lee H, Yoon J, Chang C. Valgus Arthritic Knee Responds Better to Conservative Treatment than the Varus Arthritic Knee. Medicina. 2023; 59(4):779. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59040779

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, SeungHoon, YunSeong Choi, JaeHyuk Lee, HeeDong Lee, JungRo Yoon, and ChongBum Chang. 2023. "Valgus Arthritic Knee Responds Better to Conservative Treatment than the Varus Arthritic Knee" Medicina 59, no. 4: 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59040779

APA StyleLee, S., Choi, Y., Lee, J., Lee, H., Yoon, J., & Chang, C. (2023). Valgus Arthritic Knee Responds Better to Conservative Treatment than the Varus Arthritic Knee. Medicina, 59(4), 779. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59040779