General

All materials (reagents and solvents) were purchased from Laboratoire MAT and Aldrich and used without further purification. Compound characterizations have been performed by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard in CDCl3 on a Brüker ARX 400MHz spectrometer located at the Centre Regional de RMN, by IR-FTIR using a Perkin-Elmer spectrometer, and Elemental analysis was performed by the Laboratoire d’analyse élémentaire of the University of Montreal with a Fisons Instrument, model EA 1108 CHN. The samples were imaged using an AFM Digital Instruments mounted with a Nanoprobe RTESPE7 for mode tapping-air, on mica sheets.

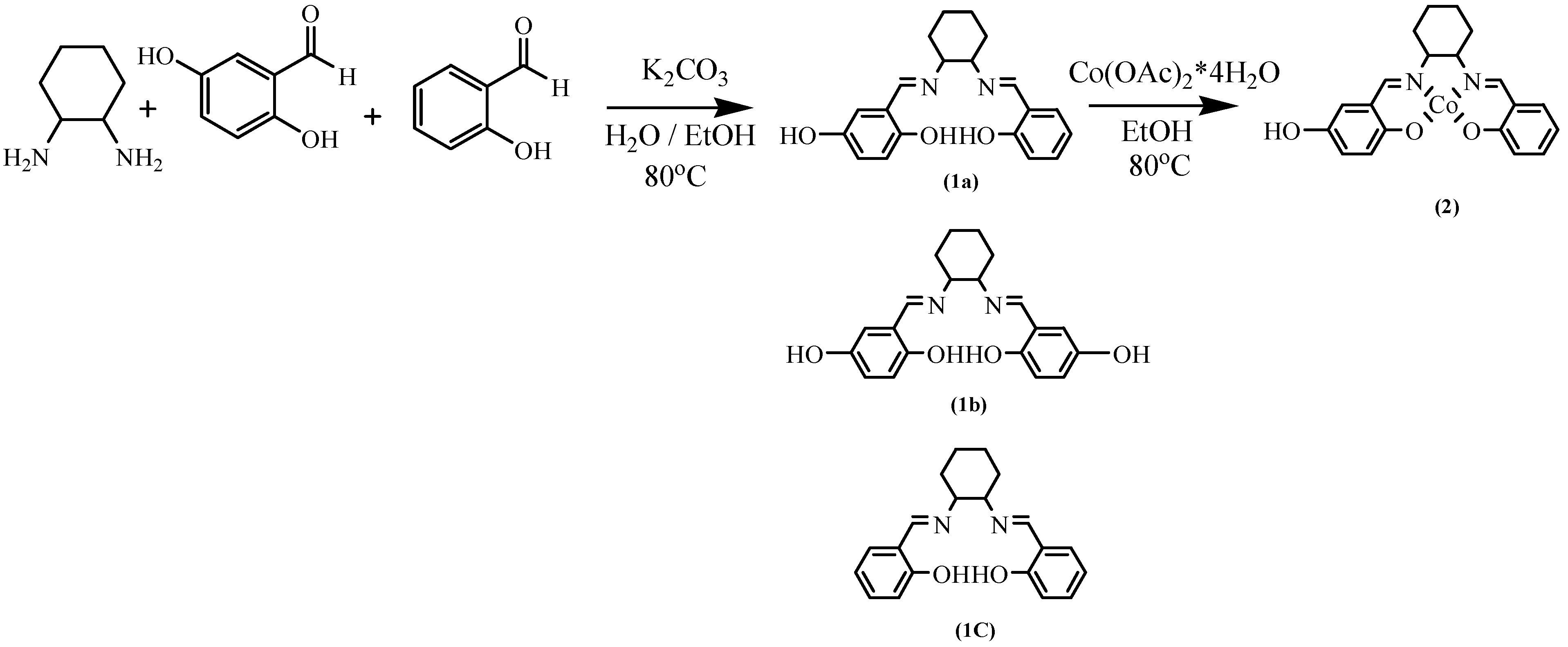

Synthesis of (R,R)-N,N’-bis(2,5-dihydroxysalicylidene)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane (

1a)

. To a solution of potassium carbonate (7 g, 50 mmol) and trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane (2.6 mL, 21 mmol) in water (20 mL) was added ethanol (65 mL) at room temperature. The resulting mixture was stirred until the reflux temperature (80 ˚C). A solution of 2,5-dihydroxybenzaldehyde (2.9 g, 21 mmol) and salicylidene (1.7 mL, 21 mmol) in ethanol (30 mL) was then added dropwise to the above reaction mixture. Stirring was continued for 14 h at reflux temperature. After the mixture was cooled to room temperature, the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. The mixture was extracted four times with ethyl acetate and water. The organic fractions were combined and the solvent was reduced to few milititer by rotary evaporation. Then, this solution was added to hexane (1 L) to isolate compound

1a from the two others. The precipitate was collected to yield 1.52 g of yellow powder (

Scheme 1); IR (KBr, cm

-1) 3305, 2932, 2857, 1637, 1490, 1272, 1154, 1039, 948 and 794;

1H-NMR (DMSO-D) δ (ppm)1.5- 2.0 (m, 8 H, -CH

2-, cyclohexane), 3.3 (m, 2 H, -CHR-, cyclohexane, 6.6 (t, 2 H, ArH), 6.8 (d, 2 H, ArH), 7.1 (d, 2 H, ArH), 7.2 (t, 1 H, ArH), 8.2 (s, 2 H, -C

H=N-);

13C-NMR (DMSO-D) δ (ppm) 25 (-CH

2-, cyclohexane), 34 (-

CH

2-CHR-, cyclohexane), 73 (-CH

2-

CHR-CHR-, cyclohexane), 117.1(CH-

CH-C(OH)

1-), 117.4 (CR-

CH-C(OH)-), 119 (CH-

CH-C(OH)external-), 121 (-

CR=CH-C(OH)-), 150 (=

C(OH)

5 -), 154 (=

C(OH)internal-) and 166 (-N=

CH-); Elemental analysis calculated: C, 71.2%; H, 6.3%; N, 8.3%. Found: C, 71.3%; H, 7.0%; N, 8.7%.

Synthesis of (R,R)-N,N’-bis(2,5-dihydroxysalicylidene)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane cobalt (

2). A reaction flask containing cobalt acetate tetrahydrate (2.4 g, 10 mmol) in ethanol (50 mL) was warmed gently to reflux temperature (80˚C). To this warm solution was added drop wise a solution of

1 (1.1 g, 3.2 mmol) in ethanol (25mL). The reaction mixture was stirred and heated at reflux for 14 h. The mixture was then cooled to ambient temperature, and 500 mL of water is added. The polymer precipitated and was filtered on Büchner to yield 0.94g (74%) of a red powder (

Scheme 1); IR (KBr, cm

-1) 3400, 2939, 2359, 1619, 1548, 1438, 1278, 1213, 1028 and 819; Elemental analysis calculated: C, 60.9%; H, 4.8%; N, 7.1%. Found: C, 60.0%; H, 5.6%; N, 5.4%.

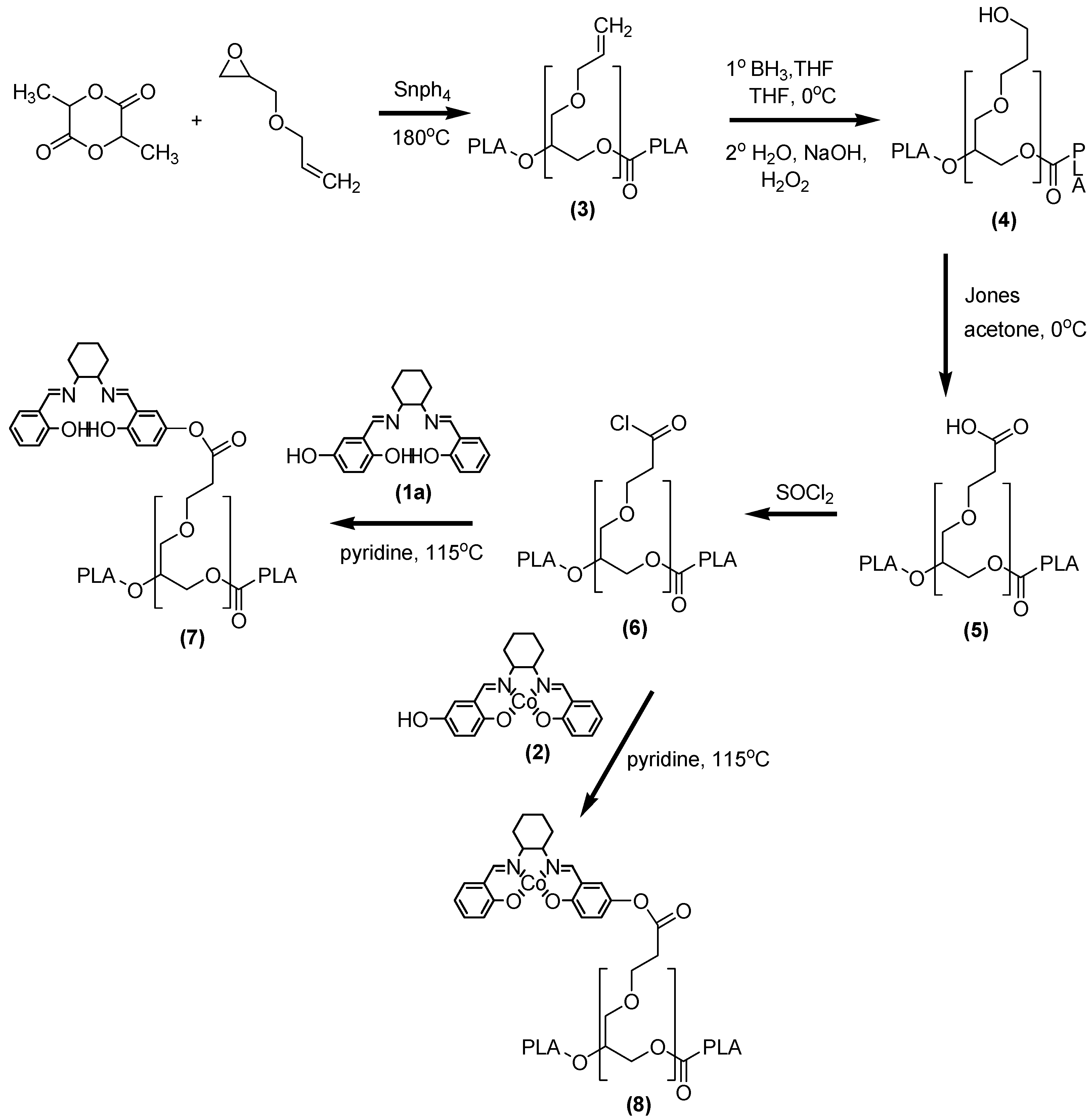

Synthesis of PLA alkene 1% polymer (

3). To remove all water from the regents, the dilactide (21.5 g, 149 mmol) and the tetraphenyletin (7.7 mg, 0.02 mmol) is dissolved in toluene then the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation and the reagents were dried under vacuum in the reaction flask. The glycidyl ether (0.36 mL, 3 mmol) was added, warmed and stirred to 180 ˚C under argon atmosphere for 6h. After this, the mixture was cooled to ambient temperature. To wash the gum, the mixture was dissolved in 50 mL of ethyl acetate and then 100 mL of water were added. The organic solvent was removed by rotary evaporation and the polymer precipitated in water. The water was thrown out to obtain the polymer. The mixture was washed three times and dried under vacuum to yield 20.8g (95%) of a white polymer (

Scheme 2);

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ (ppm)1.5 (m, 3 H, CH

3) and 5.2 (m, 1 H, CH);

13C-NMR (DMSO-D) δ (ppm) 69 (CH

3), 169 (CH). Elemental analysis calculated: C, 50.2%; H, 5.6%, Found: C, 49.7%; H, 6.0%.

Synthesis of PLA alcohol 1% polymer (

4). To dissolve PLA alkene (19.9 g, 2.7 mmol), THF (300 mL) was added at 0 ˚C then 1M NH

3 in THF (3 mL, 3 mmol) was added The mixture was stirred for 2 h at 0 ˚C. Then water (25 mL), 3N NaOH (25 mL) and H

2O

2 (30 %, 25 mL) were added. After 1h, water (300 mL) was added. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation, then the precipitate was washed using the same method described for

3. The polymer is dried under vacuum to give 14.9g (75%) of a white polymer (

Scheme 2);

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ (ppm) 1.5 (m, 3 H, CH

3) and 5.2 (m, 1 H, CH);

13C‑NMR (DMSO-D) δ (ppm) 69, 169; Elemental analysis calculated: C, 50%; H, 5.6%, Found: C, 49.4%; H, 5.8%.

Synthesis of PLA acid 1% polymer (

5). To dissolve

4 (8.4 g, 1.15 mmol), THF (500 mL) was added at 0 ˚C. Then Jones mixture: CrO

3 (0.23 g, 2.30 mmol), H

2SO

4 (0.23 mL) and water (0.70 mL) was added in this order. The mixture is stirred for 3 h at 0 ˚C then isopropyl alcohol (30 mL) and HCl (1N, 500 mL) were added. The solvent is removed by rotary evaporation. The precipitate was washed as described for

3. The polymer is dried under vacuum to give 7.8g (93%) of white polymer (

Scheme 2);

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ (ppm) 1.5 (m, 3 H, CH

3) and 5.2 (m, 1 H, CH);

13C-NMR (DMSO-D) δ (ppm) 70 (CH

3), 169 (CH); Elemental analysis calculated: C, 50%; H, 5.6%, Found: C, 49.5%; H, 6.0%.

Synthesis of PLA acyl chloride 1% polymer (

6). A reaction flask containing

5 (2 g, 0.27 mmol) in SOCL

2 (25mL) is stirred at ambient temperature for 2h. After this time, the solvent is removed by rotary evaporation. The precipitate is collected to give 1.23 g (61%) of white polymer (

Scheme 2); IR (KBr, cm

-1) 3050, 1750, 1454, 1363, 1350, 1225, 1100 and 867;

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ (ppm)1.5 (m, 3 H, CH

3) and 5.2 (m, 1 H, CH);

13C-NMR (DMSO-D) δ (ppm) 69 (CH

3), 169 (CH); Elemental analysis calculated: C, 49.8%; H, 5.6%, Found: C, 51.1%; H, 5.9%.

Synthesis of PLA-(R,R)-N,N’-bis(2,5-dihydroxysalicylidene)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane polymer (

7). A reaction flask containing

1a (3 mg, 0.009 mmol) and

6 (1.5 g, 0.2 mmol) in pyridine (20 mL) is stirred and warmed gently to reflux (115 ˚C) for 3h. After this time, the mixture is cooled to ambient temperature. To the mixture was added water (50 mL). The precipitated polymer is filtered and collected to give 1.5 g (99%) of white polymer (

Scheme 2); IR (KBr, cm

-1) 3000. 2980, 1750, 1600, 1450, 1369, 1200, 1188, 1085 and 866;

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ (ppm) 1.5 (m, 3 H, CH

3) and 5.2 (m, 1 H, CH);

13C-NMR (DMSO-D) δ (ppm) 70 (CH

3), 169 (CH).

Synthesis of PLA-(R,R)-N,N’-bis(2,5-dihydroxysalicylidene)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane cobalt polymer (

8)

. A reaction flask containing

2 (209 mg, 0.5 mmol) and

6 (1.9 g, 0.3 mmol) in pyridine (20 mL) is stirred and warmed gently to reflux (115 ˚C) for 2h. After 2h, the mixture is cooled to ambient temperature. To the mixture is added water (50 mL). The precipitated polymer is filtered and collected to give 1.5 g (74%) of beige polymer (

Scheme 2); IR (KBr, cm

-1) 3000. 2980, 1750, 1600, 1450, 1369, 1200, 1188, 1085 and 866;

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ (ppm) 1.5 (m, 3 H, CH

3) and 5.2 (m, 1 H, CH);

13C‑NMR (DMSO-D) δ (ppm) 70 (CH

3), 169 (CH); Elemental analysis calculated: C, 50.5%; H, 5.5%; N, 0.3%. Found: C, 49.1%; H, 5.8%; N, 0.2%.

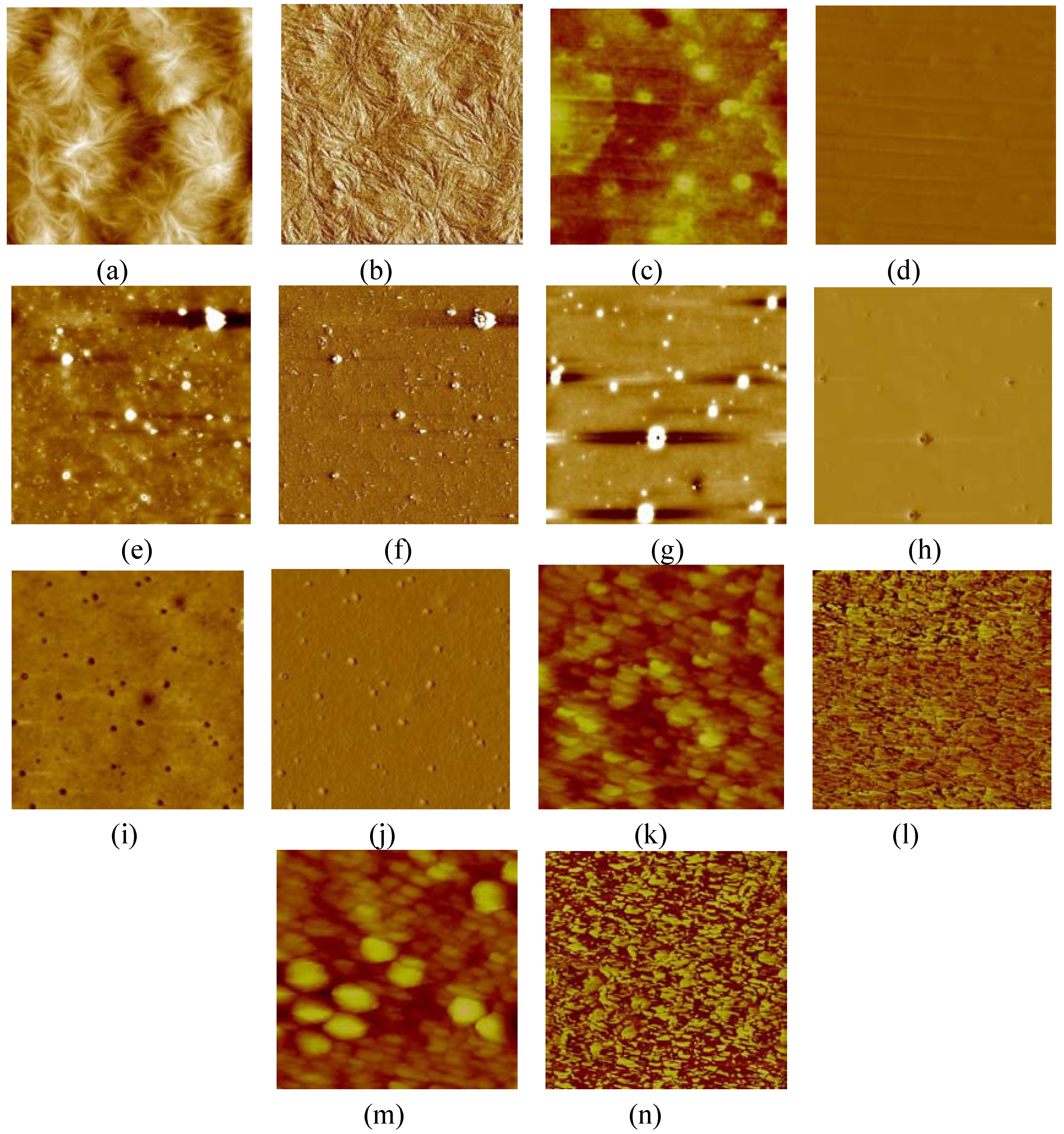

AFM study. AFM was performed on CS-PLA (8) and on SB-PLA (7), on not oriented and oriented film and on the DNA-CS-PLA complex. To obtain a non-oriented film: dissolve the polymer (0.1 g) with chloroform (5 mL). Place a drop of the polymer solution on mica and wait until complete evaporation of solvent. To obtain an oriented film: dissolve the polymer (0.1 g) in chloroform (5 mL) and add water (5mL) to the polymer solution. At this step, we observe a film at the interface of both layers. Cautiously get the film with the mica sheet to obtain the grafted hydrophilic part on top.

AFM study of DNA complexed to cationic polymer. Add calf thymus DNA (0.01 g), having a high polymeric weight, to 400 mM ammonium acetate (50 mL) and 10mM of MgCl2 (50 mL). Adjust the pH to 7.0 with NaOH. Put a drop of this solution on mica sheet and dry it in oven for 50 minutes. Wash the mica sheet, dip it in a mixture of 50:50 water-ethanol three times then in 100% ethanol to remove salt. Dry it before AFM testing.

Complexing DNA with cationic polymer. Dissolve cationic polymer (0.1 g) in chloroform (5 mL). Take DNA solution (2 mL), adjust to pH 7.0 as before and add cationic polymer (2 mL). The resulting solution was vortexed for two minutes and a drop was deposited on a mica sheet. The sample was dried before AFM testing.