4-(1H-Pyrazol-1-yl) Benzenesulfonamide Derivatives: Identifying New Active Antileishmanial Structures for Use against a Neglected Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

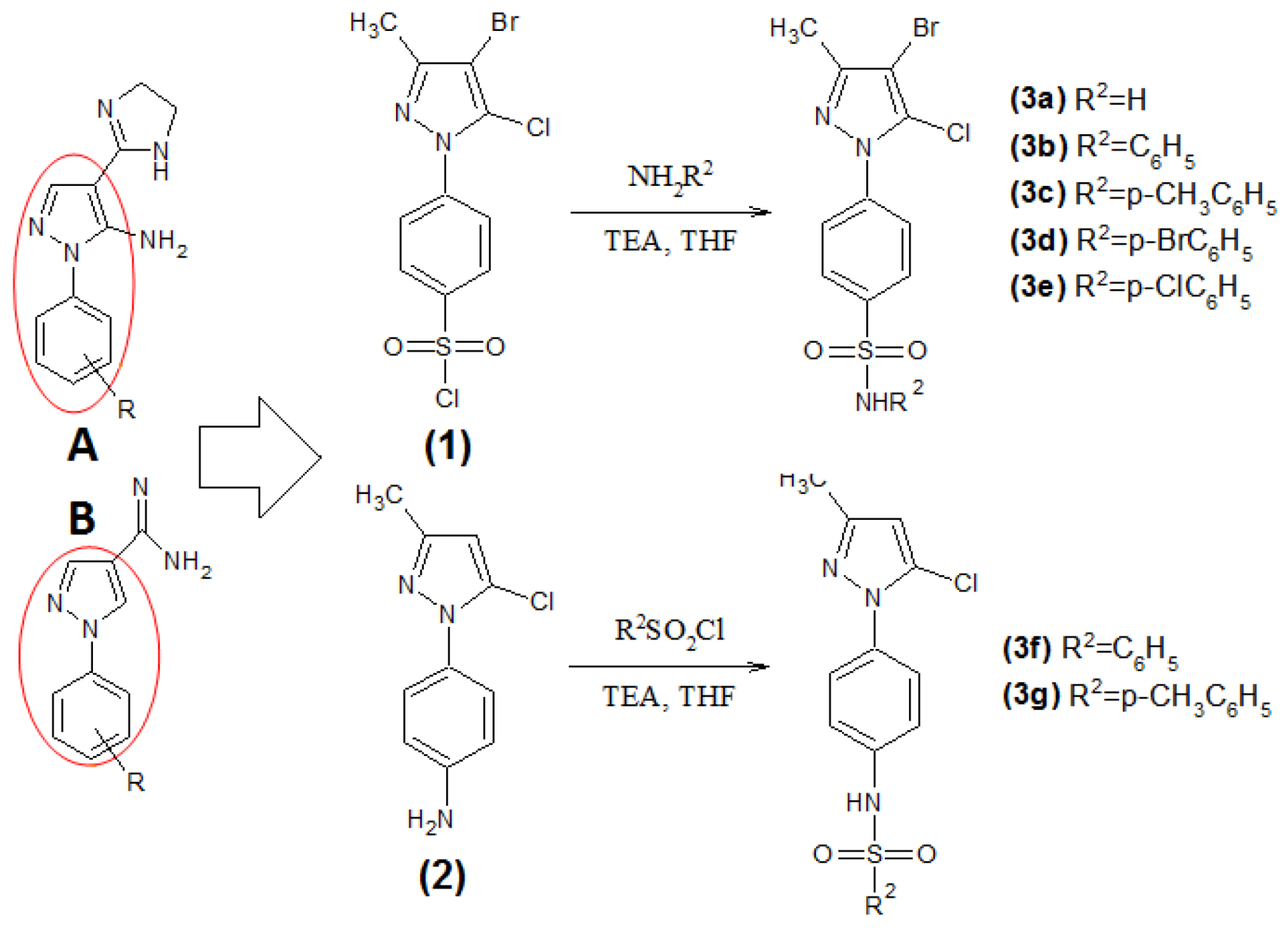

2.1. Chemistry

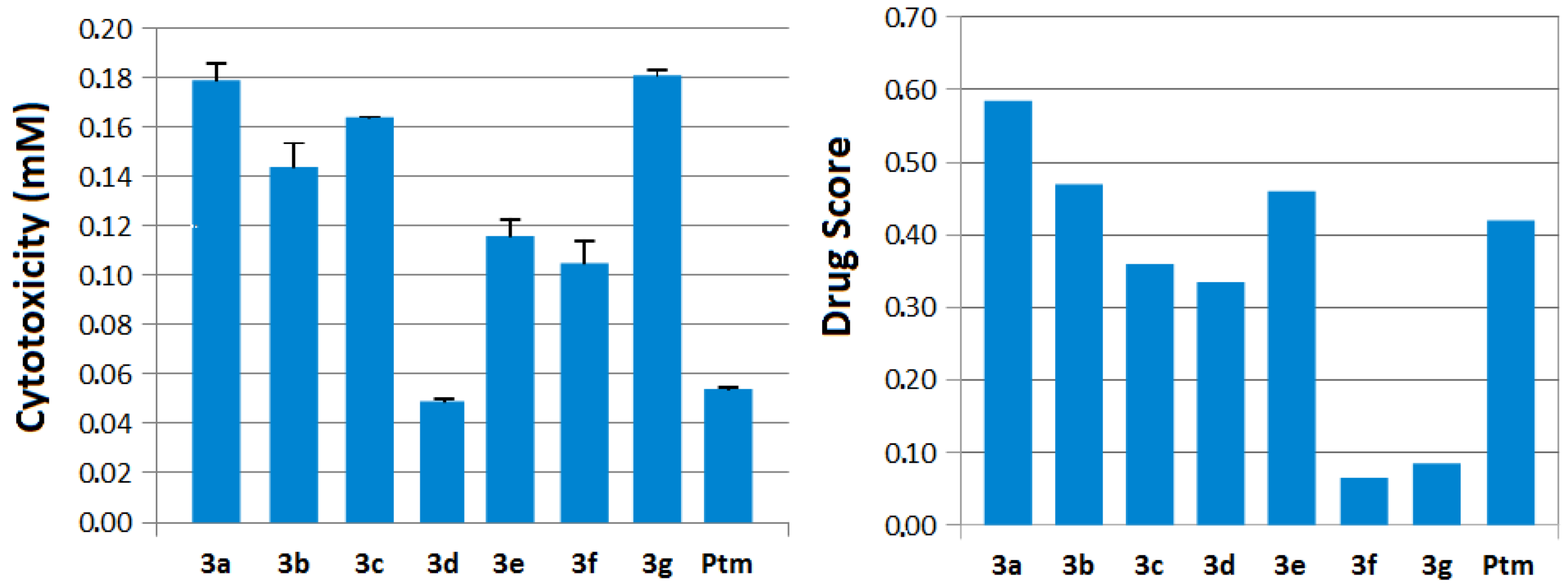

2.2. Biological Evaluation

| Compound | Antileishmanial activity | LUMO (Ev) | Dipole (Debye) | Lipinski “rule of five” | ||||||

| (IC50 = mM) a,b | ||||||||||

| Leishmania infantum | S.I c | Leishmania amazonensis | S.I c | MW | clogP | HBA | HBD | |||

| 3a | 0.228 ± 0.19 | 0.78 | 0.228 ± 0.33 | 0.78 | −1.61 | 4.61 | ||||

| 3b | 0.059 ± 0.01 | 2.44 | 0.070 ± 0.02 | 2.05 | −1.67 | 4.53 | 426.72 | 3.27 | 4 | 1 |

| 3c | 0.123 ± 0.05 | 1.33 | 0.318 ± 0.59 | 0.51 | −1.63 | 4.80 | 440.75 | 3.58 | 4 | 1 |

| 3d | 0.099 ± 0.08 | 0.49 | 0.075 ± 0.01 | 0.65 | −1.79 | 3.69 | 505.62 | 3.97 | 4 | 1 |

| 3e | 0.065 ± 0.04 | 1.78 | 0.072 ± 0.05 | 1.61 | −1.77 | 3.75 | 461.17 | 3.88 | 4 | 1 |

| 3f | 0.138 ± 0.11 | 0.76 | 0.153 ± 0.22 | 0.68 | −1.29 | 4.84 | 347.83 | 2.57 | 4 | 1 |

| 3g | 0.149 ± 0.12 | 1.21 | 0.136 ± 0.054 | 1.33 | −1.18 | 5.24 | 361.85 | 2.88 | 4 | 1 |

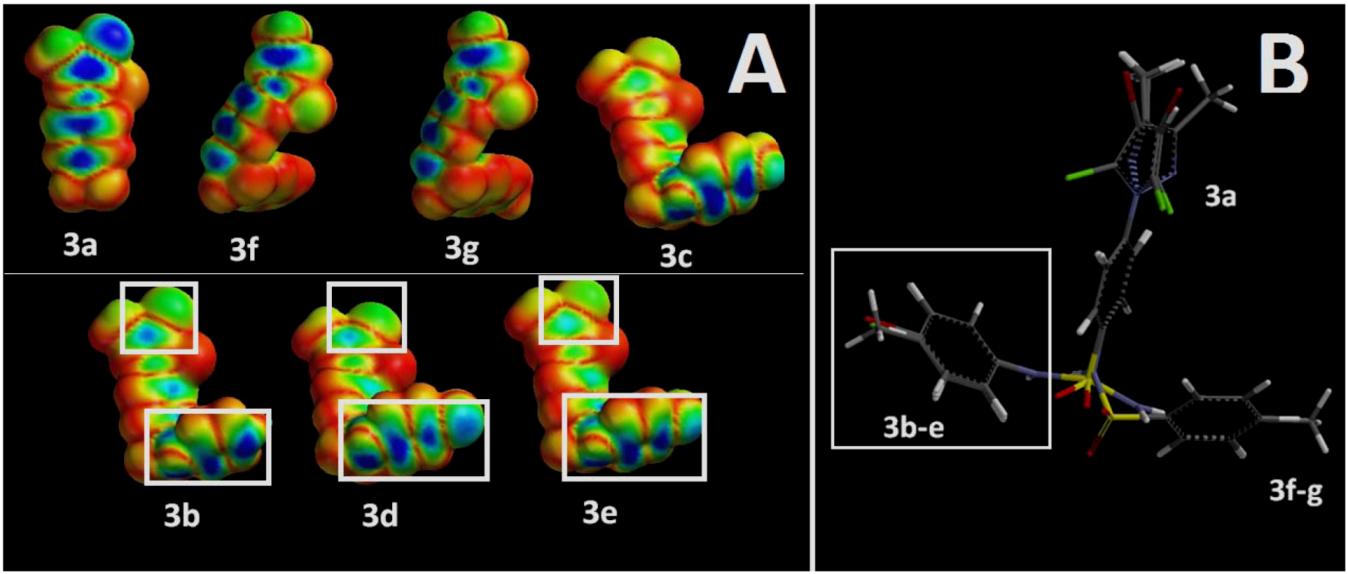

2.3. Molecular Modeling Data

3. Experimental

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. General

3.1.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of 4-(1H-Pyrazol-1-yl)benzenesulfonamides 3a–g

3.2. Pharmacology

3.2.1. In Vitro AntiLeishmanial Drug Assay

3.2.2. Animals

3.2.3. In Vitro Cytotoxicity

3.2.4. Molecular Modeling Studies:

3.2.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Conflict of Interest

Acknowledgements

References

- Alvar, J.; Vélez, I.; Bern, C.; Herrero, M.; Desjeux, P.; Cano, J.; Jannin, J.; den Boer, M.; the WHO Leishmaniasis Control Team. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One 2012, 7, e35671. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO), Organization Control of the Leishmaniases; World Health Organization Technical Report 2010, Number 949; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 1–186.

- Leon, L.L.; Barral, A.; Machado, G.M.C.; Grimaldi, G., Jr. Antigenic differences among Leishmania amazonensis isolates and their relationship clinical forms of the disease. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo. Cruz 1992, 87, 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, S.L.; Olliaro, P. Leishmaniasis chemotherapy-challenges and opportunities. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17, 1478–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, J.V.; Werbovetz, K.A. New antileishmanial candidates and lead compounds. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charret, K.S.; Rodrigues, R.F.; Bernardino, A.M.; Gomes, A.O.; Carvalho, A.V.; Canto-Cavalheiro, M.M.; Leon, L.; Amaral, V.F. Effect of the oral treatment with pyrazole carbohydrazides derivatives in the murine infection by Leishmania amazonensis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 80, 568–573. [Google Scholar]

- Kobets, T.; Grekov, I.; Lipoldova, M. Leishmaniasis: Prevention, parasite detection and treatment. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 1443–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Sundar, S. Leishmaniasis: Vaccine candidates and perspectives. Vaccine 2012, 30, 3834–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaerschot, M.; Doncker, S.; Rijal, S.; Maes, L.; Dujardin, J.-C.; Decuypere, S. Antimonial resistence in Leishmania donovani is associated with increased in vivo parasite burden. PLoS One 2011, 6, e23120. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Brazil. Casos confirmados de leishmaniose visceral Segundo UF de residências, Brasil grandes regiões e unidades federadas. 2008. Available online: http://portal.saude.gov.br/arquivos/pdf/casos_lv.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2011).

- Bernardino, A.M.R.; Gomes, A.O.; Charret, K.S.; Machado, G.M.; Canto-Cavalheiro, M.M.; Leon, L.L.; Amaral, V.F. Synthesis and leishmanial activities of 1-(4-X-phenyl)-N'-[(4-Y-phenyl)methyllene]-1H-pyrazole-4-carbohydrazides. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 41, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.S.; Gomes, A.O.; Bernardino, A.M.R.; Souza, M.C.; Khan, M.A.; Brito, M.A.; Castro, H.C.; Abreu, P.A.; Rodrigues, C.R.; Léo, R.M.M.; et al. Synthesis and antileishmanial activity of new 1-aryl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboximidamides derivatives. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2011, 22, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.S.; Oliveira, M.L.V.; Bernardino, A.M.R.; Léo, R.M.; Amaral, V.F.; Carvalho, F.T.; Leon, L.L.; Canto-Cavalheiro, M.M. Synthesis and antileishmanial evaluation of 1-aryl-4-(4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)-1H-pyrazole derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 7451–7454. [Google Scholar]

- Fustero, S.; Sánchez-Reselló, M.; Barrio, P.; Simón-Fuentes, A. From 2000 to id 2010: A fruitful decade for the synthesis of pyrazoles. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6984–7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.B.; Patel, J.N.; Lilakar, J.D. Sulfonamides of 2-[(2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino]phenyl acetoxyacetic acid and their antibacterial studies. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2010, 67, 351–359. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, B.; Vozzolo, L.; Mok, B.; Lee, C.C.; Fitzmaurice, R.J.; Caddick, S.; Fassati, A. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by isoxazolidine and isoxazole sulfonamides. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2010, 75, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.E.; Joussef, A.C.; Pacheco, L.K.; Silva, D.G.; Steindel, M.; Rebelo, R.A. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of leishmanicidal and trypanocidal activities of N-quinolin-8-yl-arylsulfonamides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 7553–7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao-Ramos, P.; Galiana-Roselló, C.; Dea-Ayuela, M.A.; González-Alvarez, M.; Veja, C.; Rolón, M.; Pérez-Serrano, J.; Bolás-Fernández, F.; González-Rosende, M.E. Nuclease activity and ultrastructural effects of new sulfonamides with anti-leishmanial and trypanocidal activities. Parasitol. Int. 2012, 61, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dea-Ayuela, M.A.; Castillo, E.; Gonzalez-Alvarez, M.; Veja, C.; Rolón, M.; Bolás-Fernández, F.; Borrás, J.; González-Rosende, M.E. In vivo and in vitro anti-leishmanial activities of 4-nitro-N-pyrimidin and N-pyrazin-2-ylbenzenesulfonamides, and N2-(4-nitrophenyl)-N1-Propylglycinamide. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 7449–7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.M.T.; Castro, H.C.; Brito, M.A.; Andrighetti-Fröhner, C.R.; Magalhães, U.; Oliveira, K.N.; Gaspar-Silva, D.; Pacheco, L.K.; Joussef, A.C.; Steindel, M.; et al. Leishmania amazonensis growth inhibitors: Biological and theoretical features of sulfonamide 4-methoxychalcone derivatives. J. Curr. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, T.M.; Morais-Braga, M.F.; Saraiva, A.A.; Rolón, M.; Veja, C.; de Arias, A.R.; Costa, J.G.; Menezes, I.R.; Coutinho, H.D. Evaluation of the anti-Leishmania activity of ethanol extract and fractions of the leaves from Pityrogramma calomelanos (L.) link. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.; Pires, P.; Dinis, A.M.; Santos-Rosa, M.; Alves, V.; Salgueiro, L.; Cavaleiro, C.; Sousa, M.C. Monoterpenic aldehydes as potential anti-Leishmania agents: Activity of Cymbopogon citratus and citral on L. infantum, L. tropica and L. major. Exp. Parasitol. 2012, 130, 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho, G.S.; Machado, P.A.; de Paula, D.T.; Coimbra, E.S.; da Silva, A.D. Synthesis, Cytotoxicity, and Antileishmanial Activity of N,N'-Disubistituted Ethylenediamine and Imidazolidine Derivatives. Sci. World. J. 2010, 10, 1723–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, F.T.; Lainson, R.; Crescente, J.A.; de Souza, A.A.; Campos, M.B.; Gomes, C.M.; Laurenti, M.D.; Corbett, C.E. A prospective study on the dynamics of the clinical and immunological evolution of human Leishmania (L.) infantum chagasi infection in the Brazilian. Amazon region. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 104, 529–535. [Google Scholar]

- Free Patent On Line. Sulfonamide-substituted fused 7-membered ring compounds, their use as a medicament, and pharmaceutical preparations comprising them. Available online: http://www.freepatentsonline.com/6908947.html (accessed on 15 January 2006).

- Andrighetti-Frohner, C.R.; de Oliveira, K.N.; Gaspar-Silva, D.; Pacheco, L.K.; Joussef, A.C.; Steindel, M.; Simões, C.M.; de Souza, A.M.; Magalhaes, U.O.; Afonso, I.F.; et al. Synthesis, biological evaluation and SAR of sulfonamide 4-methoxychalcone derivatives with potential antileishmanial activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 755–763. [Google Scholar]

- Parise-Filho, R.; Pasqualoto, K.F.; Magri, F.M.; Ferreira, A.K.; da Silva, B.A.; Damião, M.C.; Tavares, M.T.; Azevedo, R.A.; Auada, A.V.; Polli, M.C.; et al. Dillapiole as Antileishmanial Agent: Discovery, Cytotoxic Activity and Preliminary SAR Studies of Dillapiole Analogues. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim) 2012, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canto-Cavalheiro, M.M.; Echevarria, A.; Araujo, C.A.; Bravo, M.F.; Santos, L.H.; Jansen, A.M.; Leon, L.L. The potential effects of new synthetic drugs against Leishmania amazonensis and Trypanosoma cruzi. Microbios 1997, 90, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schetz, J.A. Structure-Activity Relationships. xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference 2007, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, D.F.V. Frontier orbitals in chemical and biological activity: Quantitative relationships and mechanistic implications. Drug Metab. Rev. 1999, 31, 755–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P. Experimental and computacional approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. J. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 46, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Not available.

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Marra, R.K.F.; Bernardino, A.M.R.; Proux, T.A.; Charret, K.S.; Lira, M.-L.F.; Castro, H.C.; Souza, A.M.T.; Oliveira, C.D.; Borges, J.C.; Rodrigues, C.R.; et al. 4-(1H-Pyrazol-1-yl) Benzenesulfonamide Derivatives: Identifying New Active Antileishmanial Structures for Use against a Neglected Disease. Molecules 2012, 17, 12961-12973. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules171112961

Marra RKF, Bernardino AMR, Proux TA, Charret KS, Lira M-LF, Castro HC, Souza AMT, Oliveira CD, Borges JC, Rodrigues CR, et al. 4-(1H-Pyrazol-1-yl) Benzenesulfonamide Derivatives: Identifying New Active Antileishmanial Structures for Use against a Neglected Disease. Molecules. 2012; 17(11):12961-12973. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules171112961

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarra, Roberta K. F., Alice M. R. Bernardino, Tathiane A. Proux, Karen S. Charret, Marie-Luce F. Lira, Helena C. Castro, Alessandra M. T. Souza, Cesar D. Oliveira, Júlio C. Borges, Carlos R. Rodrigues, and et al. 2012. "4-(1H-Pyrazol-1-yl) Benzenesulfonamide Derivatives: Identifying New Active Antileishmanial Structures for Use against a Neglected Disease" Molecules 17, no. 11: 12961-12973. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules171112961