1. Introduction

Positron emission tomography (PET) is an outstanding instrument for the quantification and localization of physiological as well as pathophysiological activities and processes

in vivo which were analyzed by tracing the appropriate biochemical fundamentals [

1]. The basics of PET rely on the coincidental detection of annihilation photons in nearly 180° originating from positrons of the parent radionuclide inside the tracer [

2]. Measurements and quantifications of the tracer distribution were accelerated noninvasively in living organisms. For that purpose, fluorine-18 produced by a cyclotron was chosen as the ideal radionuclide due to its favorable half-life. Furthermore, the low positron energy and short ranges in tissues lead to high image resolution [

3]. However, tracers for PET imaging purposes are restricted by the kind of fluorinated molecules that researchers can prepare.

In principle, radiolabeling of biologically active compounds and especially high molecular weight compounds like peptides, proteins and antibodies with fluorine-18 still represents a considerable challenge and has therefore generated immense interest. As a result of harsh reaction conditions for the direct introduction of fluorine-18 at high specific activity levels, novel radiolabeling strategies comprising fluorine-18-containing prosthetic groups, also referred as

18F-labeling building blocks, are necessary. Due to this fact and due to the multitude of functional groups found in bioactive macromolecules, a labeling strategy has to be developed for almost every one of these compounds. To overcome the above mentioned obstacles, bioorthogonal click-labeling reactions were developed and successfully applied to allow the selective introduction of fluorine-18 under mild conditions, with high radiochemical yields (RCY) and high specific activity (A

S) [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

The concept of bioorthogonal syntheses refers to all reactions which can proceed inside of living systems without any interference with native biochemical processes. Several requirements have to be fulfilled for a reaction to be considered as bioorthogonal [

9]. First and most prominently, selective reactions should be applied to avoid side-reactions with other functional groups found in the biological starting compounds. Both functional groups of the participating reaction partners must be inert to the residual biological moieties and should only react with each other. Secondly, the resulting covalent bond should be strong and chemically inert to biological reactions, and, in addition, it should not affect the (native) biological behavior of the desired molecule. Thirdly, the reaction should benefit from fast reaction kinetics in the case that covalent ligations are achieved prior to probe metabolism and clearance and the reaction must be run on the time scale of cellular processes to prevent biological side reactions. This point is especially important both for the work with short-living positron emitters and further for an application of

in vivo pre-targeting strategies. At least, the non-toxicity of the reaction partner as well as catalysts are of high importance for

in vivo applications, and the reaction should proceed under biological conditions taking into account pH, aqueous environments, and temperature.

Giving consideration to the criteria of bioorthogonal reactions, Kolb, Finn and Sharpless [

10,

11] defined the click chemistry as a

“set of powerful, highly reliable, and selective reactions for the rapid synthesis of useful new compounds and combinatorial libraries” and pointed out the following requirements for click reactions: modularity, wideness in scope, very high yielding, stereospecificity (but not necessarily enantioselectivity) and simple product isolation (separation from harmless by-products by non-chromatographic methods). In addition to these criteria, these reactions should proceed using simple reaction conditions (solvent free or solvents like water) including simply accessible starting materials, and the final product has to be stable under physiological conditions [

12]. Selected examples of click chemistry reactions are pointed out in

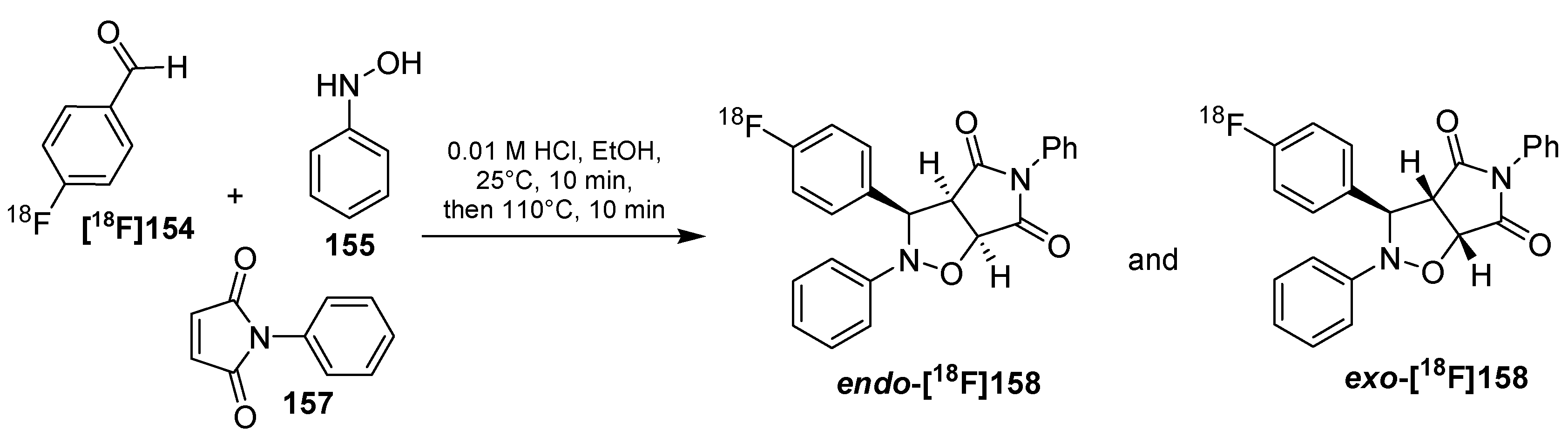

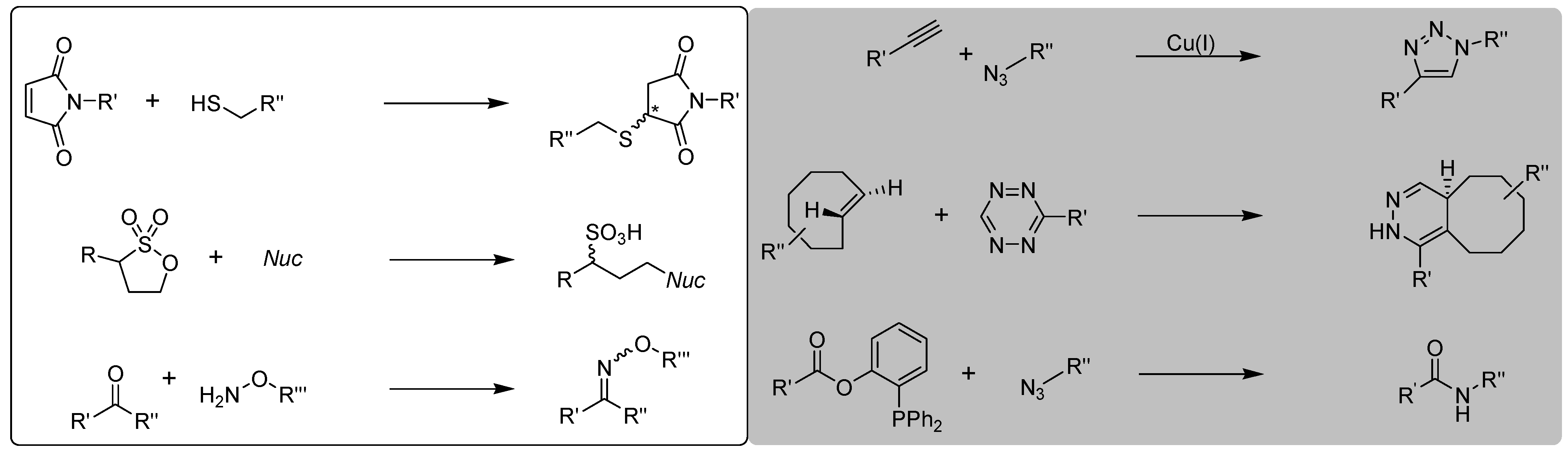

Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Selected examples of chemical conjugations associated with click chemistry. All reactions highlighted in grey fulfill the bioorthogonality criteria.

Scheme 1.

Selected examples of chemical conjugations associated with click chemistry. All reactions highlighted in grey fulfill the bioorthogonality criteria.

In recent years, the terms “bioorthogonal reactions” and “click chemistry” have entered into the field of radiochemistry and radiopharmacy. Bioorthogonal reactions in general, and click chemistry in particular, are generic terms for a set of labeling reactions, which make use of several selective and modular building blocks and enable chemoselective ligations to radiolabel biologically relevant compounds. In this context, the Cu(I)-mediated triazole formation from azides and terminal alkynes according to the 1,3-dipolar Huisgen cycloaddition is a particularly powerful ligation reaction, due to its high degree of specificity and the biocompatibility of both starting materials. In the same way, the strain promoted Huisgen click-reaction as well as both variants of the Staudinger Ligation were applied. The absence of catalysts makes these reactions together with the inverse Diels-Alder tetrazine-click reaction tremendously attractive for radiolabeling purposes. Neither azides nor phosphanes, alkenes or tetrazines react with other functional groups commonly present in biopolymers like peptides or proteins. Hence, there is no need for protective group chemistry. Moreover, the desired linking moieties (triazoles, amides or cyclooctapyridazines) are metabolically stable under physiological conditions. As a consequence, click chemistry is a very attractive approach for the design and synthesis of novel potent radiotracers for molecular imaging purposes.

3. Cu-Catalyzed 1,3-Dipolar Huisgen Cycloaddition

1893 was the year of birth of the 1,3-dipolar Huisgen cycloaddition as Arthur Michael described for the first time the preparation of 1,2,3-triazoles from phenylazide and dimethyl but-2-ynedioate [

29]. The reaction of hydrogen azide with acetylene to give the corresponding 1,2,3-triazole was first described by Dimroth and Fester 17 years later [

30]. Based on this work, Huisgen investigated and specified the character of this reaction as a 1,3-dipolar addition in 1963 [

31]. Arbitrary alkynes are used as first reaction partners and serve as dipolarophiles in this reaction. Azides as second reaction partners are ambivalent compounds only describable as zwitterions in an all-octet formula. The driving force for the formation of triazoles in particular is the disappearance of the charges in the azide [

32].

Normally, organic azides react with alkynes at high temperatures to give 1,2,3-triazoles in the Huisgen cycloaddition with formation of both 1,4- and 1,5-disubstituted regioisomers. In 2002, the groups of Sharpless

et al. [

33] and Meldal

et al. [

34] independently introduced a revolutionary innovation into the field of 1,3-dipolar Huisgen cycloaddition due to the application of Cu(I)-species as catalyst. The so called

copper-catalyzed

azide

alkyne

cycloaddition (CuAAC) proceeds faster, delivers the respective 1,4-isomer exclusively and can be performed at ambient temperatures. Both groups assumed a mechanism in which Cu(I) coordinates first to the terminal alkyne forming a copper(I)acetylide. Computer calculations confirmed these presumptions and predicted a non-concerted mechanism through a six-membered copper(III) metallacycle [

35]. Newer findings using continuous-flow analysis cannot exclude a primary addition of the Cu(I) to the azide moiety [

36]. Nowadays, Worrel

et al. have suggested a new mechanism discovered by utilizing

63Cu-enriched catalysts. Thus, two copper atoms are incorporated in the catalytic cycle [

37] as seen in

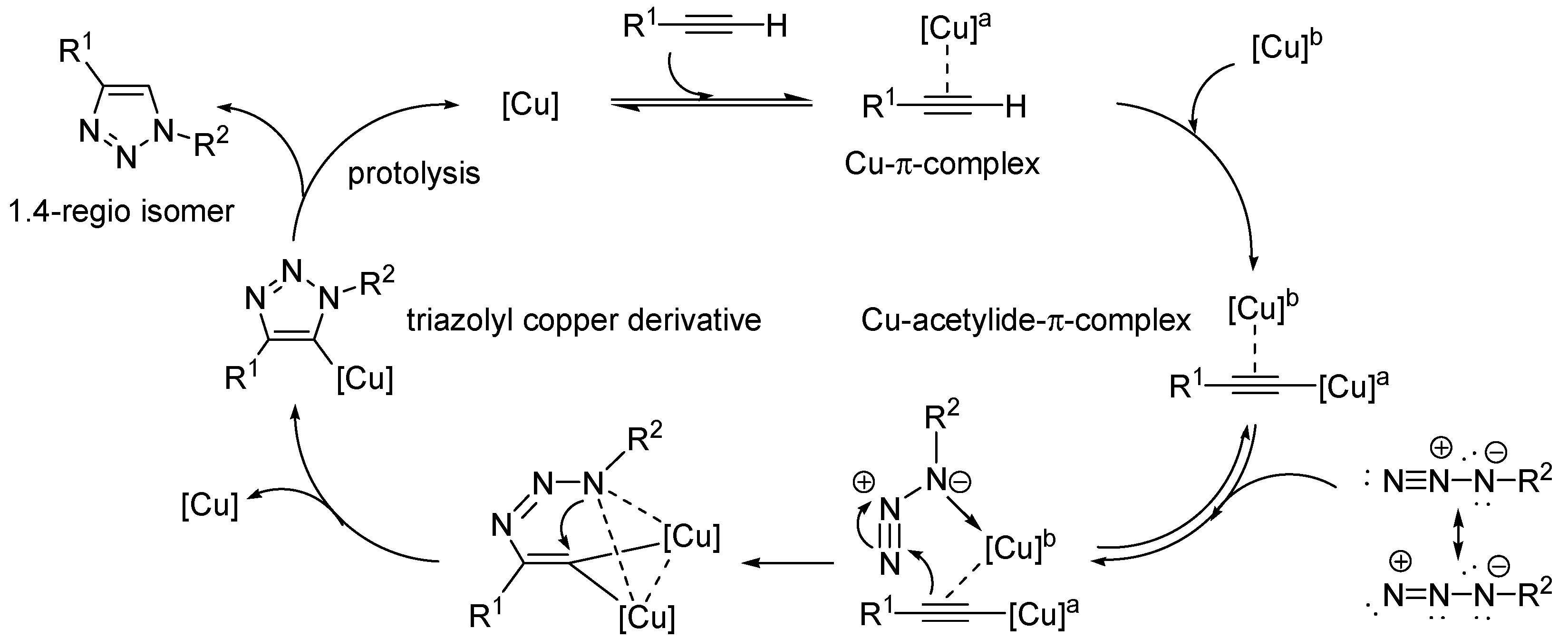

Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism of the copper-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar Huisgen cycloaddition (CuAAC) catalyzed by two copper atoms.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism of the copper-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar Huisgen cycloaddition (CuAAC) catalyzed by two copper atoms.

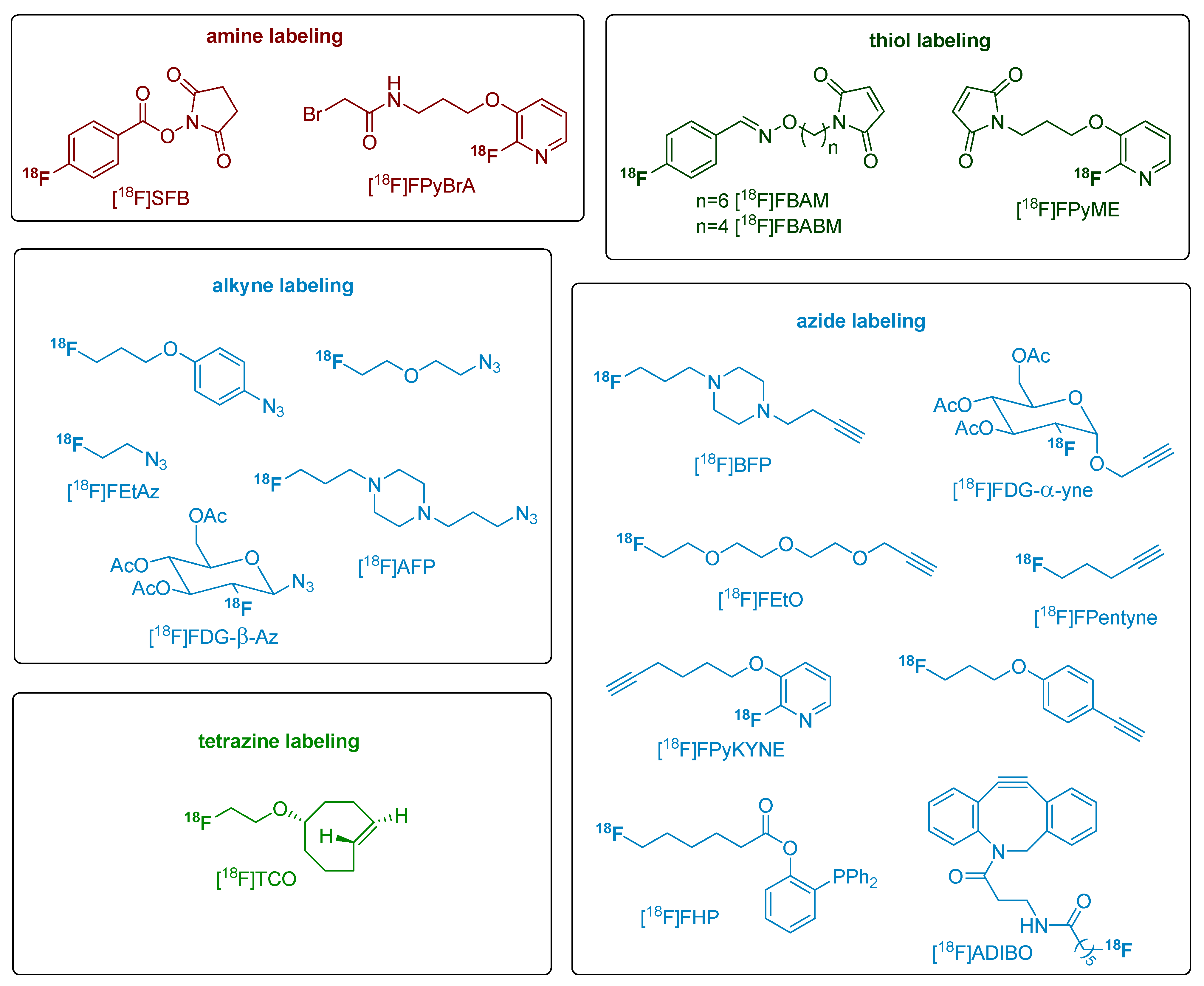

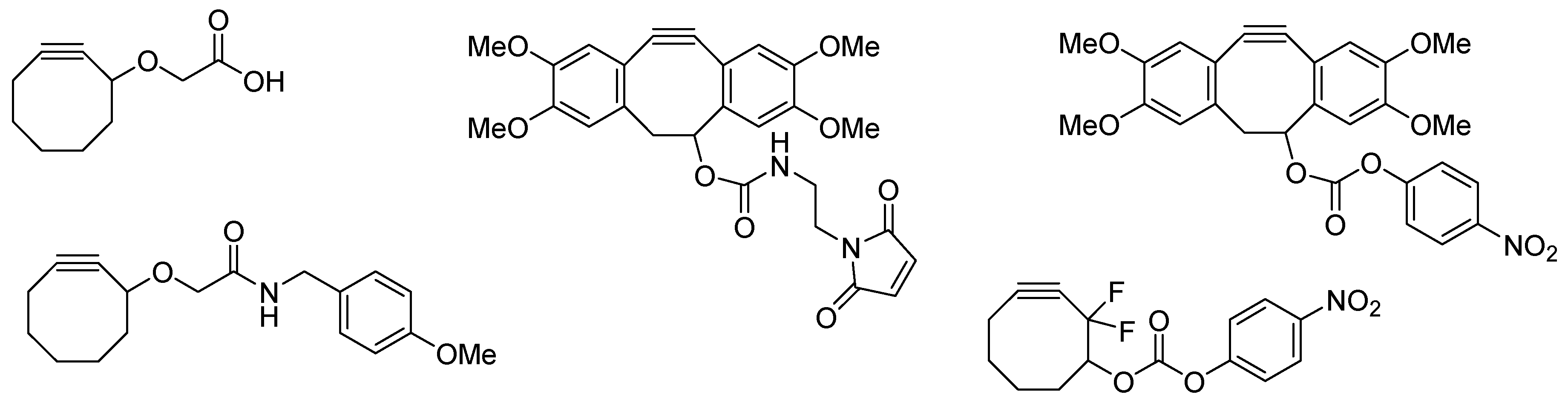

Scheme 3.

A selection of various conventional and bioorthogonal labeling building blocks for the incorporation of fluorine-18.

Scheme 3.

A selection of various conventional and bioorthogonal labeling building blocks for the incorporation of fluorine-18.

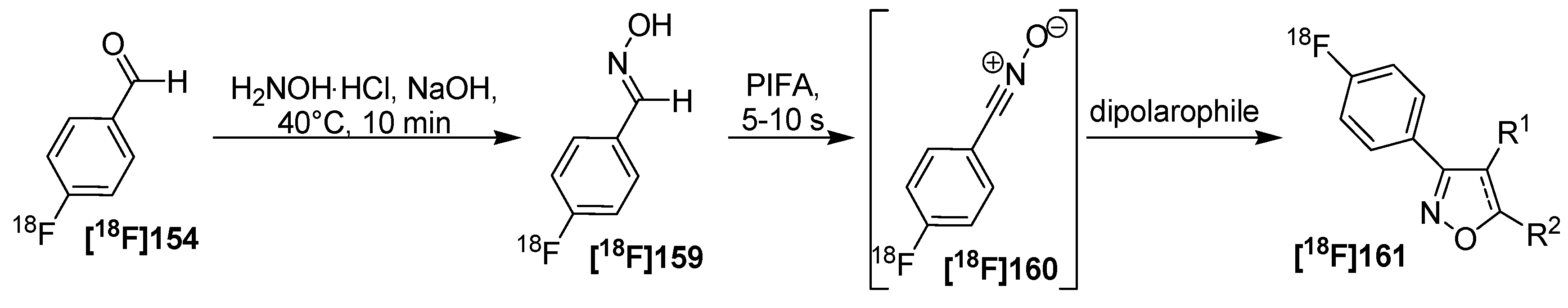

As a result of its favorable properties and reaction conditions, the CuAAC has gained enormous popularity and has been applied in diverse fields of chemistry [

38]. Since 2006, the CuAAC is introduced for labeling purposes of biologically and pharmacologically relevant molecules with fluorine-18 (

Scheme 3). Up until now, over 60 works have been published using this 1,3-dipolar Huisgen cycloaddition for

18F-labeling of small organic compounds, peptides, oligonucleotides, proteins and nanoparticles which were partially used for PET studies [

5,

6,

39,

40]. The first application of click chemistry for the design and synthesis of radiometal-based radiotracers to form novel multidentate triazole ligand scaffolds for an efficient chelation of the

99mTc(CO)

3 core was reported by the group of Schibli in 2006 [

41]. In 2008, the first application of the CuAAC for the introduction of carbon-11 using [

11C]methyl azide was published by Schirrmacher and co-workers [

42].

The bioorthogonality of both functional groups used in the Huisgen cycloaddition makes this reaction to connect

18F-containing building blocks to sensitive bioactive molecules like peptides or proteins highly attractive. Problematically, copper is known to be cytotoxic towards prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. It is reported that viruses and oligonucleotides are damaged or destroyed in its presence [

43]. Other side effects that it is associated with include hepatitis, Alzheimer’s disease or neurological disorders. Therefore, it is of enormous importance for

in vivo applications to remove the copper completely from the desired radiotracer or to develop copper-free, bioorthogonal alternatives [

44].

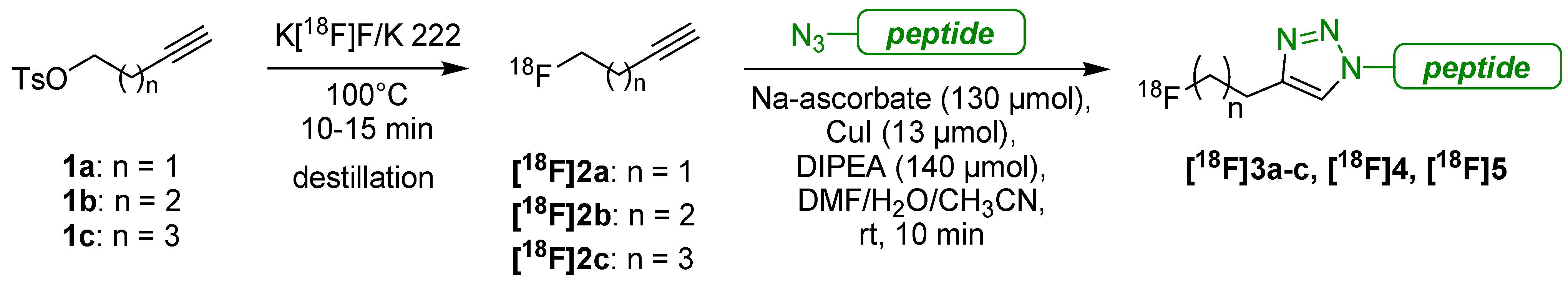

The first application of the CuAAC in the field of fluorine-18-radiochemistry and -radiopharmacy was published by Marik and Sutcliffe in 2006. They described the synthesis of three

18F-containing alkynes

[18F]2a–c with different chain lengths for the radiolabeling of azide-functionalized peptides [

45]. For this purpose, three tosylated alkynes

1a–c were treated with [

18F]fluoride/K

2CO

3/K 222 in acetonitrile at 100 °C (

Scheme 4). Due to their fugacity,

[18F]2a–c were purified by co-distillation with acetonitrile into a second vial which was cooled down to −78 °C. It was figured out that the formation of

2b resulted in the highest radiochemical yield (RCY) of 81% and radiochemical purity (RCP) of 98%. Subsequently, an azide-functionalized model peptide with amino acid sequence YGGFL was radiolabeled with

[18F]2a–c under CuAAC conditions within 10 min.

[18F]3b was obtained with the highest yield (97%) after optimizations. In addition, two other peptides

[18F]4 (97%) and

[18F]5 (99%) were prepared; the results are shown in

Table 1. All peptides were obtained with A

S > 35GBq/μmol after isolation using a C18 Sep-Pak extraction. Unreacted building blocks

[18F]2a–c were evaporated together with the eluent to yield all

18F-labeled peptides in excellent radiochemical purity. It was also mentioned that the use of bipyridine or bathophenanthroline based ligands for the copper species further improve the yields.

Scheme 4.

Radiolabeling and distillation procedure followed by the CuAAC according to conditions published by Meldal

et al. [

34].

Scheme 4.

Radiolabeling and distillation procedure followed by the CuAAC according to conditions published by Meldal

et al. [

34].

Table 1.

Results of the radiolabeling with [18F]2a–c.

Table 1.

Results of the radiolabeling with [18F]2a–c.

| Building block | Resulting [18F]fluoropeptide | Yield [%] | Purity [%] |

|---|

| [18F]2a | (18F-alkyne, n = 1)-YGGFL

[18F]3a | 54 | 95 |

| [18F]2b | (18F-alkyne, n = 2)-YGGFL

[18F]3b | 97 | 98 |

| [18F]2c | (18F-alkyne, n = 3)-YGGFL

[18F]3c | 62 | 99 |

| [18F]2b | AGDLHVLR-Ebes-Lys-(18F-alkyne, n = 2)

[18F]4 | 97 | 81 |

| [18F]2b | (18F-alkyne, n = 2)-AGDLHVLR

[18F]5 | 99 | 87 |

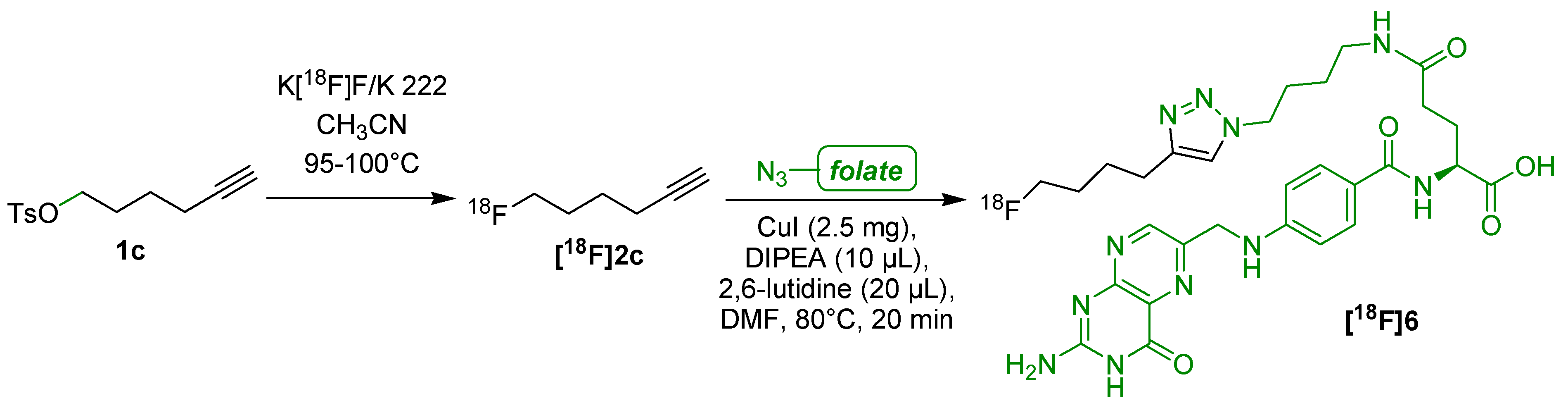

Next, Ross

et al. applied the CuAAC for the synthesis of

18F-labeled folic acid derivative

[18F]6 using 6-[

18F]fluorohexyne (

[18F]2c) [

46]. After an overall synthesis time of approx. 90 min (

Scheme 5), the isolated product

[18F]6 was obtained in a RCY of 25–35%, with a RCP > 99% and a A

S of 160 ± 70 GBq/μmol. Afterwards,

[18F]6 was applied to mice bearing a folate receptor(FR)-expressing KB tumor. Activity accumulation in KB tumors at 45 min p.i. amounted to 3.13% ± 0.83 ID/g. Strong hepatobiliary excretion of the lipophilic tracer led to elevated accumulation (16.53% ID/g) of the activity in the abdominal region.

Scheme 5.

18F-labeled folic acid derivative [18F]6.

Scheme 5.

18F-labeled folic acid derivative [18F]6.

In 2008, Hausner

et al. used

18F-pentyne

[18F]2b for the radiolabeling of a α

vβ

6 specific peptide A20FMDV2 [

47] and compared it with solid-phase radiolabeling using 4-[

18F]fluorobenzoic acid [

18F]FBA as well as 2-[

18F]fluoropropionic acid [

18F]FPA. In addition to that case, effects of these labeling moieties on PET imaging and pharmacokinetics were evaluated. In conclusion, the [

18F]FBA-labeled peptide was obtained in 22 ± 4% RCY and the [

18F]FPA-incorporated peptide was prepared in 13 ± 3% RCY. In contrast, labeling using

[18F]2b resulted in only 10% RCY for the respective labeled peptide. Therefore, conventional labeling on solid support should be preferred for longer peptides. Additionally, male athymic nude mice bearing α

vβ

6-positive and α

vβ

6-negative (control) cell xenografts were employed for biodistribution studies. The click-labeled peptide shows similar tumor uptake but a different metabolism than ulterior

18F-labeled peptides.

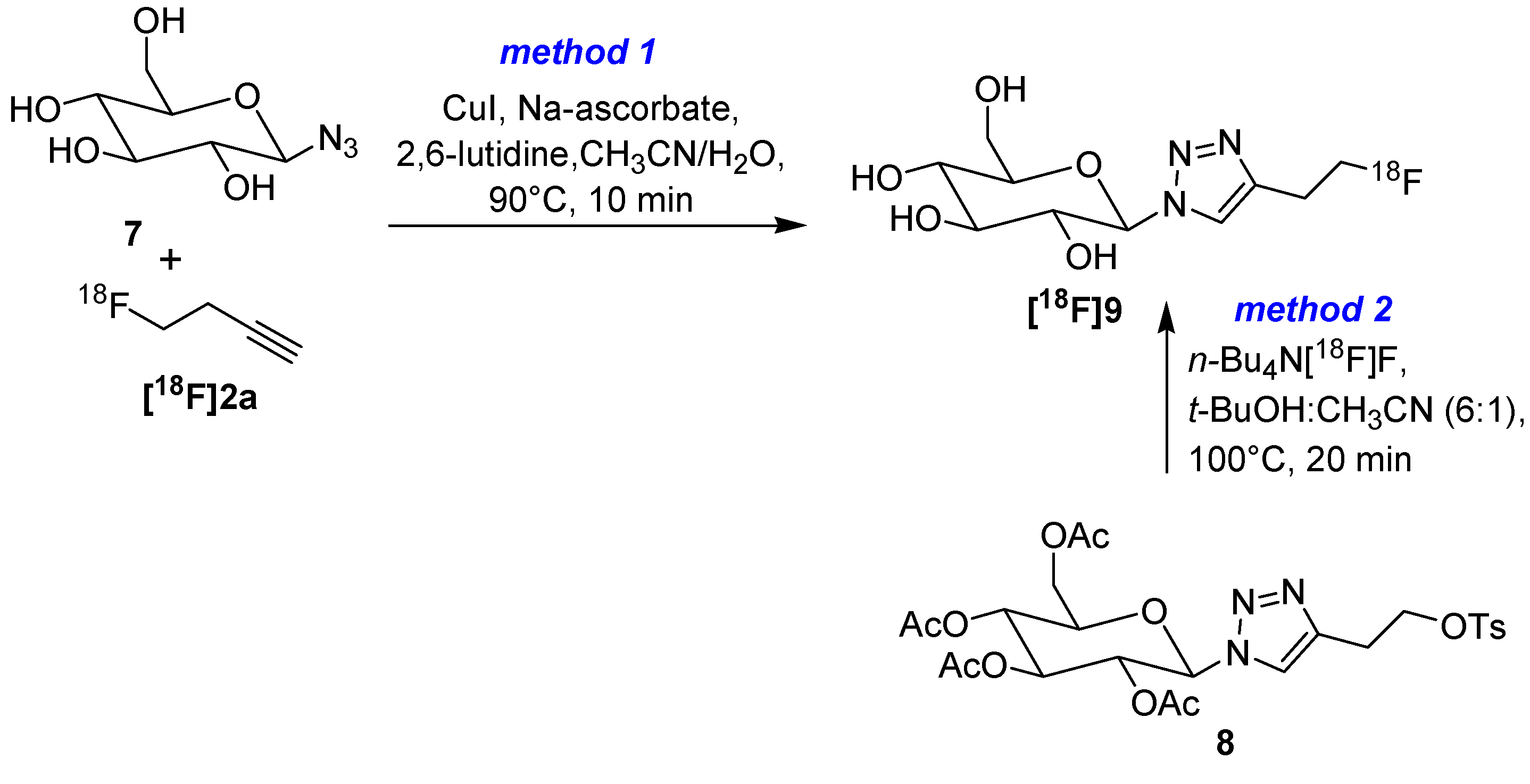

In the same year, Kim

et al. compared a two-step click labeling approach (method 1) with a direct radiofluorination (method 2) for the labeling of β-azido-

d-glucose (

7) as alternative for a radiolabeling with [

18F]FDG (

Scheme 6) [

48]. For method 1 (click approach), 4-[

18F]fluoro-1-butyne (

[18F]2a) was prepared from the appropriate tosylate precursor and was co-distilled into a second vial containing glucopyranosyl azide

7, CuI, sodium ascorbate and 2,6-lutidine as base. Stirring at 90 °C for 10 min, followed by HPLC purification ensued glucose derivative

[18F]9 with a RCY of 30% (d.c.).

Scheme 6.

Comparison of conventional nucleophilic labeling with click approach.

Scheme 6.

Comparison of conventional nucleophilic labeling with click approach.

Method 2: Tosylate precursor 8 was radiolabeled under conventional conditions with [18F]fluoride in a mixture of acetonitrile and tert-butanol (v:v = 1:6). [18F]9 was obtained in a RCY of 21% (d.c.) after subsequent removal of acetyl groups with sodium methanolate in methanol and HPLC purification. Surprisingly, the achieved AS for the click approach was higher (59.9 GBq/µmol) compared to the conventional approach (23.5 GBq/µmol). Further, in vitro evaluation demonstrated that a triazole moiety at the C1 position of [18F]9 is tolerated neither by the hexokinase nor by the Glut-1 transporter. A slight uptake of [18F]9 in tumor cells (0.2%) could not be blocked.

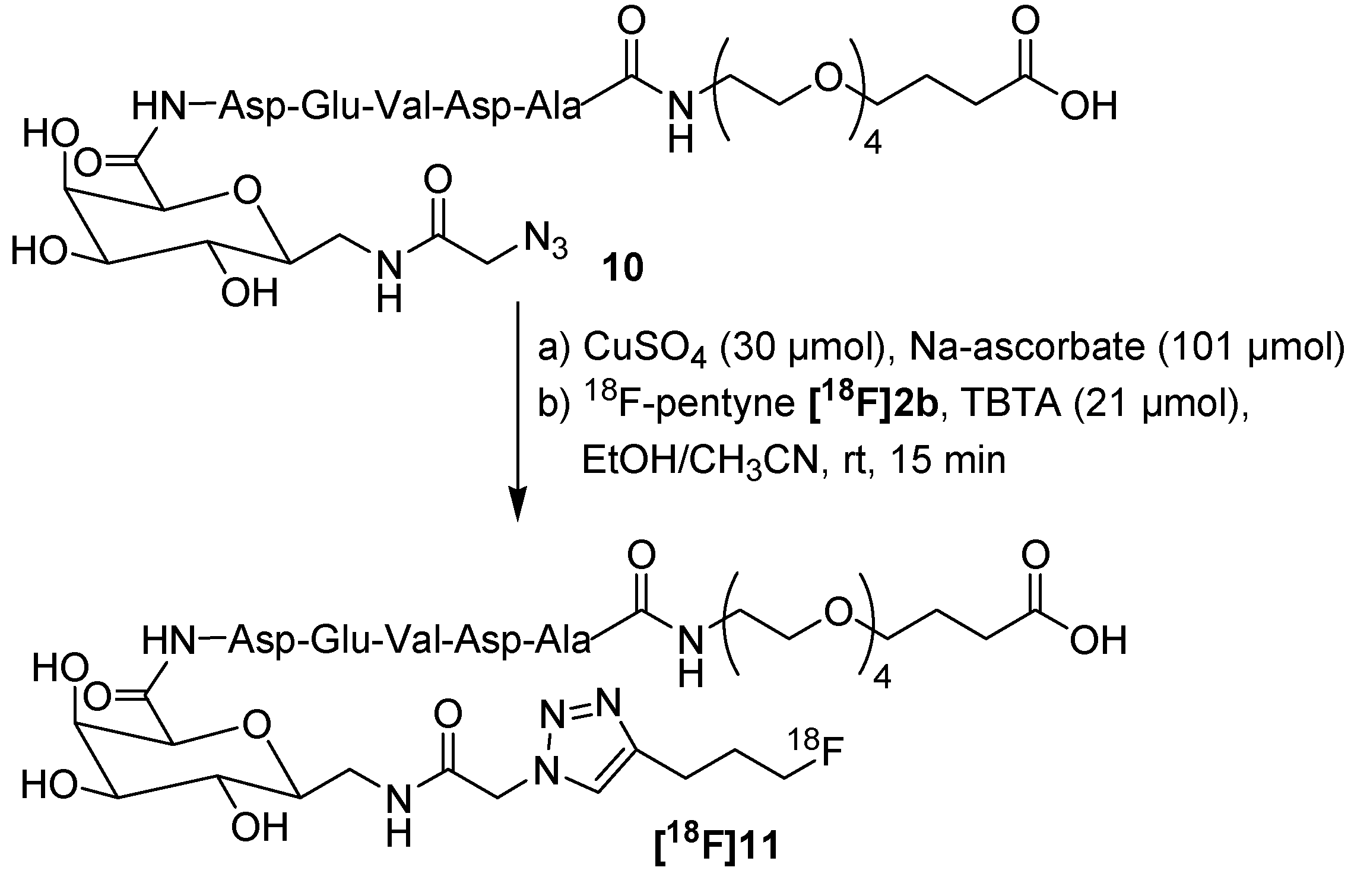

Based on previous studies of Marik and Sutcliffe [

45], Kim

et al. further evaluated 4-[

18F]fluoro-1-butyne (

[18F]2a) as synthon for

18F-click radiolabeling with various azido compounds [

49]. They pointed out, that the conditions of the nucleophilic substitution of butyne precursor

1a with K[

18F]F delivered a by-product (

Scheme 7) in a remarkable percentage which was evidenced as vinyl acetylene (

9) among the desired

18F-butyne

[18F]2a (approx. ratio of

9 and

[18F]2a 79:21 in

t-BuOH and 87:13 in acetonitrile) while the same reaction using pentyne

1b exclusively resulted

18F-pentyne

[18F]2b. Thus, they underscored the thesis that alkyne-precursors with chain lengths longer than four carbon atoms are better synthons for the preparation of

18F-alkyne building blocks due to the suppression of elimination as a side-reaction.

Scheme 7.

Formation of vinyl acetylene (9).

Scheme 7.

Formation of vinyl acetylene (9).

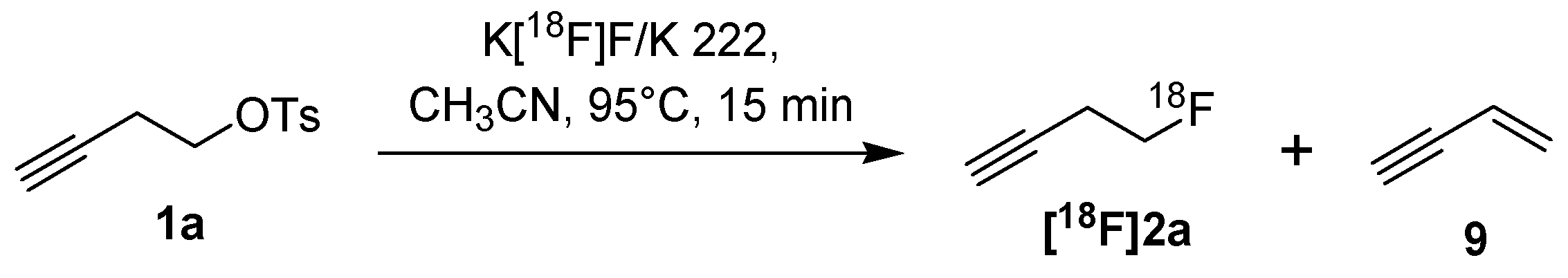

Later, Zhang

et al. presented an automated synthesis route for

18F-pentyne

[18F]2b which was then applied for

18F-labeling of an apoptosis marker (

Scheme 8) [

50].

[18F]2b was obtained with a RCY of 51% and was automatically distilled into a second vial containing the peptide precursor

10. The conversion of

18F-pentyne

[18F]2b into

18F-peptide

[18F]11 amounts nearly 99% after a total synthesis time of 70 min (RCY: 21.0 ± 4.5%, RCP > 99%, A

S = 870 GBq/μmol). A549 lung cells were utilized for an

in vitro evaluation. After treatment with carboplatin, the A549 cell uptake of

18F-peptide

[18F]11 was found to be 0.86 ± 0.04% together with a cell apoptosis rate of 10.23 ± 2.43%. In contrast, the cell uptake of untreated control cells was found to be 0.06 ± 0.01% (cells apoptosis rate = 1.02 ± 0.31%). From this point of view,

18F-peptide

[18F]11 could be a promising candidate for future apoptosis imaging.

Scheme 8.

Automated synthesis of 18F-labeled peptide [18F]11 for apoptosis imaging.

Scheme 8.

Automated synthesis of 18F-labeled peptide [18F]11 for apoptosis imaging.

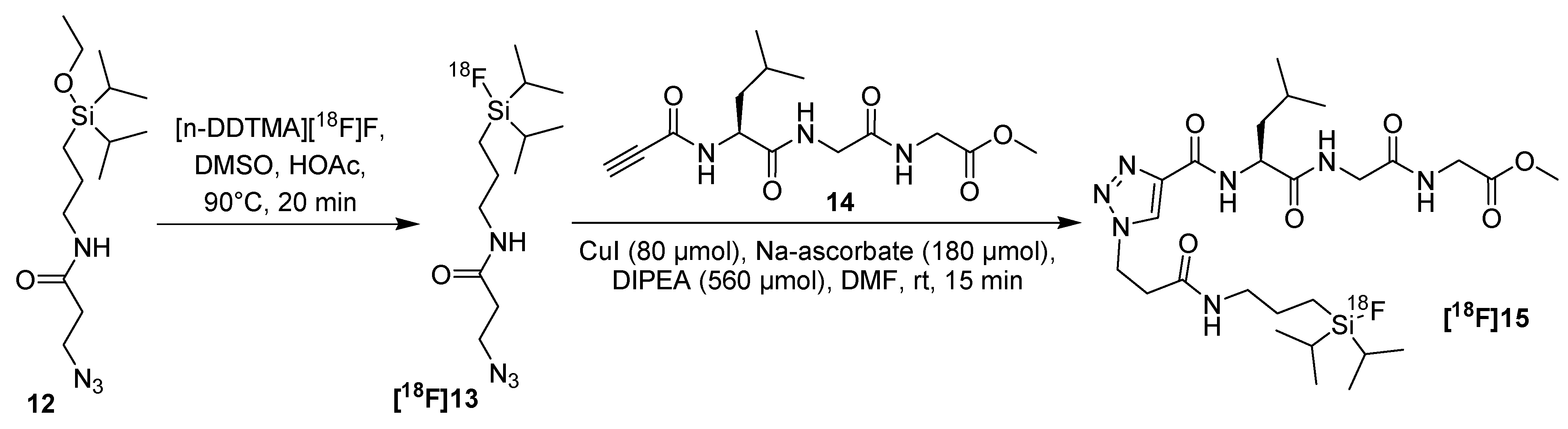

In 2011, Balentova

et al. presented an interesting work concerning the

18F-labeling of alkyne functionalized model peptide

14 under CuAAC-conditions utilizing a novel and

18F-Si-based azide

[18F]13 [

51]. In general, the high affinity of fluorine for silicon allows a facile introduction of fluorine-18 under mild conditions as well. For this purpose, precursor

12 was prepared and labeled with

n-dodecyltrimethylammonium [

18F]fluoride in DMSO at 90 °C for 20 min (RCY 64% for

[18F]13, d.c.). Subsequently, labeling of peptide

14 was accomplished at ambient temperature for 15 min using CuI, sodium ascorbate and DIEA as base. Peptide

[18F]15 was obtained in 75% RCY (d.c.) and with a RCP > 97% (

Scheme 9).

Scheme 9.

18F-labeling of alkyne-functionalized model peptide 14 utilizing 18F-Si-based azide [18F]13.

Scheme 9.

18F-labeling of alkyne-functionalized model peptide 14 utilizing 18F-Si-based azide [18F]13.

Problematic, the thermodynamically stable F-Si bond is known to be hydrolyzed in water under physiological conditions unless there are no bulky alkyl groups attached to the silicon. Unfortunately, 18F-Si-labeled peptide [18F]15 as well as the building block [18F]13 had a low hydrolytic half-life (<13 min) in buffers at different pH values. The silicon fluorine bond is not enough stabilized by the presence of the two isopropyl groups.

3.1. 18Fluoro-PEGX-Derivatives

This part of the review deals with PEGylated 18F-labeled building blocks. In general, PEGylation describes the process of covalent connection of polyethylene glycol (PEG) moieties to drugs or therapeutic compounds. These compounds are “masked” from the host’s immune system and the water solubility of hydrophobic derivatives is enhanced. Due to the increase of the size its circulatory time is often prolonged by reducing renal clearance.

The main advantage of PEGylated

18F-labeled building blocks is their reduced volatility compared to the smaller counterparts. Hence, these compounds are easier to handle and the corresponding bioconjugates show a higher blood clearance which is important for

in vivo studies. In 2007, Sirion

et al. presented a set of four various

18F-labeled building blocks

[18F]16 to

[18F]19 for the labeling of molecules using the CuAAC (

Scheme 10) [

52],

[18F]19 contains a PEG-like moiety. In the first step, all mesylate precursors were reacted with [

18F]fluoride in

t-BuOH at 100 °C for 20 min in the presence of TBAHCO

3 to obtain the corresponding [

18F]acetylenes

[18F]16 to

[18F]19 with RCY ≥ 90%. Further, these building blocks are thermally stable, nearly nonvolatile, and are therefore suitable for one-pot, two-step syntheses.

Scheme 10.

Building blocks evaluated by Sirion and co-workers.

Scheme 10.

Building blocks evaluated by Sirion and co-workers.

In the next step, different functionalized biomolecule-like compounds were successfully labeled within 10 min with an excellent

18F-conversion of 97–100%. Small non-polar organic compounds needed longer reaction times (30 min) and resulted in limited

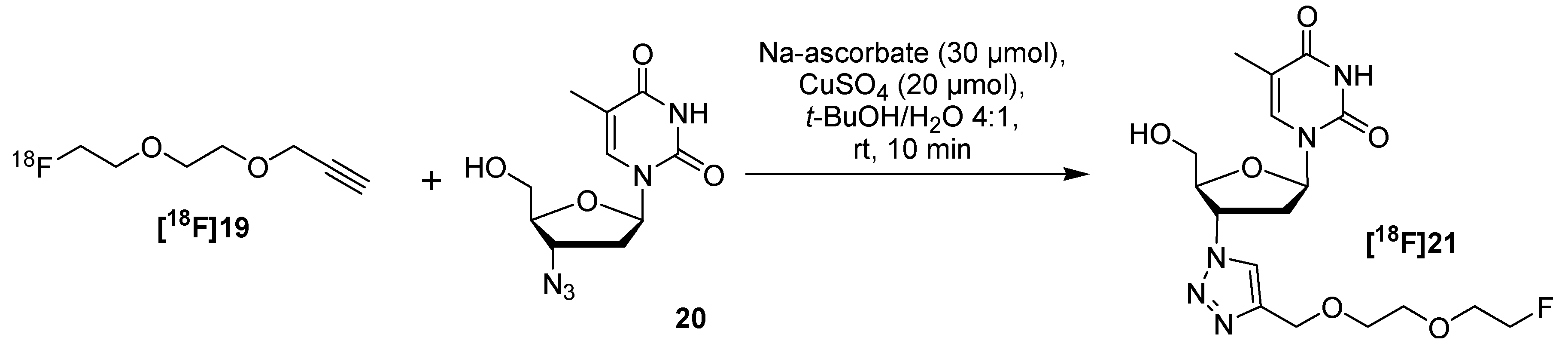

18F-conversion up to 71%. In most of the cases, the two-step reaction was completed within 40 min from the end of bombardment. The sample labeling reaction of azide functionalized deoxythymidine

20 utilizing alkyne

[18F]19 is pointed out in

Scheme 11.

Scheme 11.

18F-labeling of azide functionalized thymidine derivative utilizing [18F]19.

Scheme 11.

18F-labeling of azide functionalized thymidine derivative utilizing [18F]19.

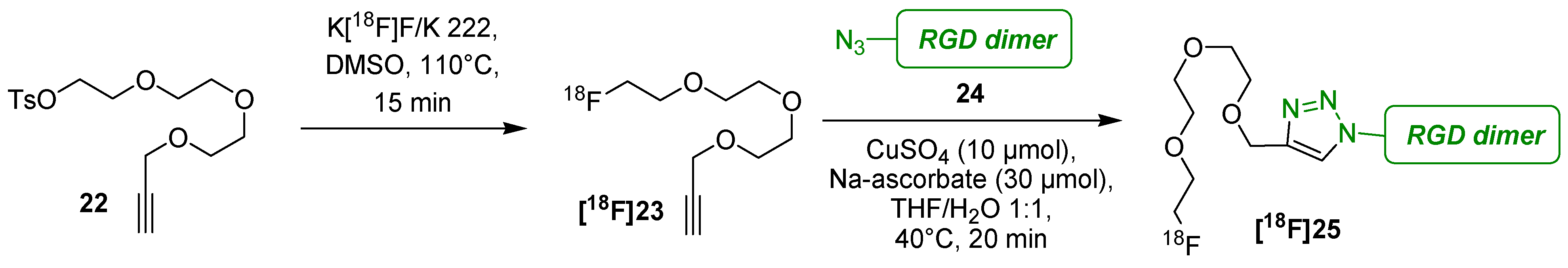

Li

et al. described the preparation of [

18F]FPTA-RGD

2 [18F]25 which was labeled with 3-(2-(2-(2-[

18F]-fluoroethoxy)-ethoxy)ethoxy)prop-1-yne (

18F-PEG

3) (

[18F]23) [

53]. This labeling building block

[18F]23 was obtained in a non decay-corrected yield of 65.0 ± 1.9% from

22. To increase the affinity the RGD moiety was twice connected to a glutamate which was further functionalized with azide. The major advantage of the click approach was the shortening of the labeling time compared to the conventional labeling with [

18F]SFB from 180 min to 110 min combined with an increase of the RCY to 53.8% (d.c.) for [

18F]FPTA-RGD

2 [18F]25 (

Scheme 12).

In vivo evaluations of

[18F]25 using athymic nude mice bearing a U87MG tumor demonstrated a lower α

vβ

3-integrin affinity in contrast to other

18F-labeled RGD peptides due to the relatively long PEG

3 moiety.

Scheme 12.

18F-labeling of an azide functionalized RGD-dimer utilizing a 18F-PEG3-alkyne.

Scheme 12.

18F-labeling of an azide functionalized RGD-dimer utilizing a 18F-PEG3-alkyne.

In 2009, the group of Devaraj

et al. used the same

18F-building block

18F-PEG

3 [18F]23 for the preparation of

18F-CLIO – a fluorine-18-containing trimodal nanoparticle [

54]. The basis of this particle consists of an aminated cross-linked dextran iron oxide (CLIO) decorated with diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid. The advantage of

18F-CLIO was the ability of a triple detection by PET, fluorescence molecular tomography as well as magnetic resonance imaging. The

18F-nanoparticle was prepared as briefly follows:

18F-PEG

3 [18F]23 was added to the azido-CLIO in a PBS buffer. This mixture was then treated with CuSO

4/bathophenanthrolinedisulfonic acid (BPDS, as disodium salt) and sodium ascorbate in distilled water. The reaction mixture was incubated for 40 min at 40 °C and filtrated to remove the resulting

18F-CLIO from unreacted

18F-PEG

3 with a RCY of 58% (d.c.).

First evaluations of 18F-CLIO suspended in the agar phantom pointed out a detection threshold of 0.025 µg Fe/mL for PET-CT imaging. This is approximately 200 times lower than by T2*-weighted MR imaging. The lowest observed concentration of the nanoparticles by MRI was 5 µg Fe/mL (15), demonstrating a PET detection threshold 200 times more sensitive than MRI at current specific activities. A high in vivo stability for 18F-CLIO was demonstrated due to the low renal and bladder uptake, no excretion via the kidneys was observed.

In 2011, Gill and Marik used optimized conditions and switched the bioorthogonal functionalities for radiolabeling of

N-alkynylated peptide

28 (4-pentynoyl-Val-Asp-Asn-Lys-Phe-Asn-Lys-Glu-Nle-Gln-Asn-Ala-Tyr-Ala-Ile-Glu-Ile-Ala-Leu-Leu-Pro-Asn-NH

2) using

18F-PEG

3-azide

[18F]27 (

Scheme 13) [

55]. After purification by HPLC,

18F-labeled peptide

[18F]29 could be obtained with RCY of 31% and a A

S = 1.44 GBq/µmol. The removal of BPDS was difficult using solid phase extraction (SPE) which lowered the chemical purity. Therefore, optimized reaction conditions without BPDS provided 96% conversion after 60 °C for 10 min when using 1.6 µmol Cu(CH

3CN)

4PF

6 and 10 nmol of

28 at high concentrations (125 µL). Noteworthy, a maximum A

S and RCP were only obtainable when

28 was quantitatively converted to

18F-labeled peptide

[18F]29 due to their similar molar mass and retention times in HPLC and SPE. Furthermore, the copper source should be considered very crucial, since PF

6- can lower the A

S due to an isotopic exchange.

In 2012, Lee

et al. used the same

18F-PEG

3-azide

[18F]27 for the radiolabeling of ZnO nanoparticles (20 nm) in order to observe their behavior and accumulation in organic tissues after oral administration using PET [

56].

18F-labeling of ZnO particles resulted in A

S = 0.73 MBq/mg and RCP > 95%. PET images indicated that

18F and

18F-ethoxyazide showed radioactivity in the bone and bladder 3 h after oral administration, whereas radioactivity for

18F-labeled ZnO nanoparticles was seen only in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. At 5 h post-administration, biodistribution studies demonstrate that

18F-labeled ZnO nanoparticles showed radioactivity in the lung, liver and kidney including the GI tract.

Scheme 13.

18F-labeling of an alkyne functionalized peptide 28 utilizing 18F-PEG3-azide [18F]27.

Scheme 13.

18F-labeling of an alkyne functionalized peptide 28 utilizing 18F-PEG3-azide [18F]27.

3.2. [18F]Fluoroethylazide

[

18F]Fluoroethylazide–

18F-FEA (

[18F]33) is certainly the most popular building block for radiolabeling purposes using the CuAAC. The first approach was evaluated and applied by Glaser and Årstad in 2007 [

57]. 2-Azidoethyl-4-toluenesulfonate (

32) was used as starting material and the subsequent nucleophilic fluorination with anhydrous n.c.a. K 222, K[

18F]F in acetonitrile at 80 °C for 15 min yielded the desired azide

[18F]33 (RCY = 55%, d.c.). The isolation was done by distillation. The reaction sequence for

18F-FEA

[18F]33 is pointed out in

Scheme 14.

Scheme 14.

Reaction sequence for the preparation of (18F-FEA) [18F]33.

Scheme 14.

Reaction sequence for the preparation of (18F-FEA) [18F]33.

In most of the cases, the isolation of

[18F]33 was accomplished by co-distillation with acetonitrile. Notably, tosylate

32 is also co-distilled when using higher temperatures (>90 °C), and

32 reacts with the alkyne precursor as well in the subsequent labeling step. At temperatures below 90 °C the transfer of tosylate

32 to the cooled receiver vial was negligible, but the distillation time had to be extended [

58]. Next, the somewhat difficult handling due to the volatility of the building block during the radiosynthesis brought different reaction set-ups in order to make the handling of

18F-FEA

[18F]33 easier. Up to now, the [

18F]FEA-synthesis and the following labeling step with the respective alkyne were transferred into a remotely controlled module using a cooling trap [

58].

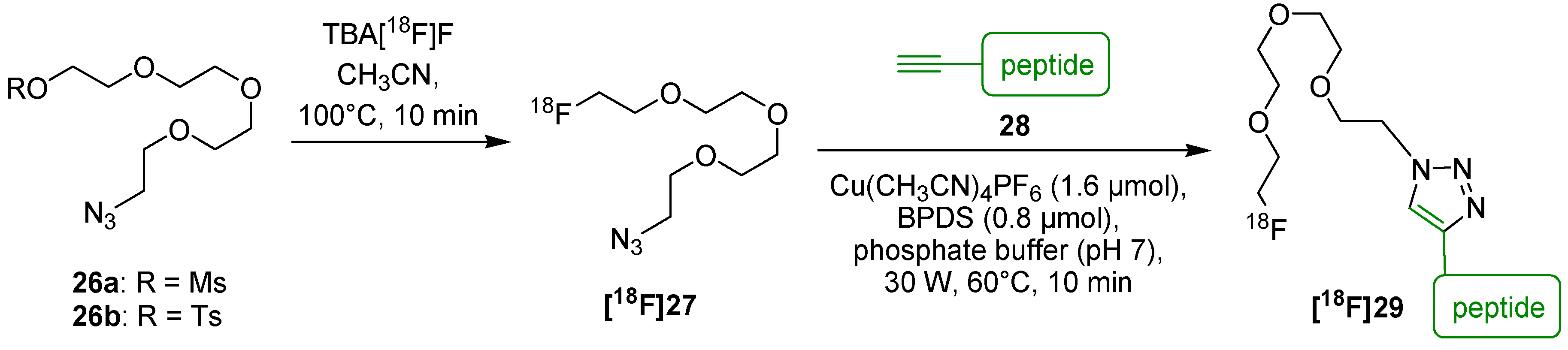

The convenient and fast access of

18F-FEA

[18F]33 led to multitude of radiotracers, e.g., for the imaging of apoptosis with [

18F]MitoPhos_01

[18F]34 [

59] or isatine derivatives like [

18F]ICMT-11

[18F]35 [

60,

61] connected with a GMP-applicable automated synthesis [

62]. Furthermore, tracers for proliferation like [

18F]deoxyuridine

[18F]36 [

63] or [

18F]FOT and [

18F]FTT

[18F]37a,b [

64] were developed.

18F-labeled quinazoline derivatives

[18F]38 and

[18F]39 for the EGFR activity imaging were prepared [

58,

65]. [

18F]FET-G-TOCA

[18F]40 for the somatostatin receptor [

66], [

18F]haloethylsulfoxides like

[18F]41 [

67] and six

18F-labeled nitroaromates based on [

18F]MISO [

68] to visualize hypoxia were evaluated. Further, it is possible to address the α

vβ

3 receptor with

18F-containing RGD peptides e.g.,

[18F]42a,b [

69,

70,

71]. [

18F]AFETP

[18F]43 was introduced as a tracer for the imaging of brain tumors [

72] and mouse DBT glioma [

73]. Galante

et al. used

18F-FEA

[18F]33 for the radiofluorination of a series of 6-halopurines in a one-pot automated synthesis approach [

74]. They used the copper chelator bathophenanthrolinedisulfonate to accelerate the cycloaddition reaction. An overview of all these tracers is given in

Scheme 15.

Scheme 15.

Overview of radiotracers prepared by CuAAC with 18F-FEA [18F]33.

Scheme 15.

Overview of radiotracers prepared by CuAAC with 18F-FEA [18F]33.

The last approach using [

18F]fluoroethylazide (

[18F]33) was published by Jia

et al. in 2013 [

75]. This group demonstrated the simultaneous labeling of various alkynes with

18F-FEA

[18F]33 in a one-pot procedure. In general, two or more different alkynes were mixed in a DMF-solution together with CuSO

4 and sodium ascorbate. Afterwards, a solution of

[18F]33 in acetonitrile was added, the resulting mixture was shaken at 60 °C for 15 min and then analyzed/purified via HPLC after filtration. This procedure is pointed out in

Scheme 16. Importantly, an appropriate HPLC separation system has to be developed for the separation of the resulting tracers prior the radiolabeling.

Scheme 16.

The technical route of the multiple labeling procedure.

Scheme 16.

The technical route of the multiple labeling procedure.

In 2012 Glaser

et al. reported, that

18F-FEA

[18F]33 is able to be reduced to give

18F-fluoroethylamine by the use of copper wire under acidic conditions, which could be a reason for the sometimes low RCY in click reactions [

76]. Another approach published by Zhou

et al. in 2012 used

18F-FEA

[18F]33 for the synthesis of a [

18F]SFB analog [

77]. They pointed out that base labile NHS-esters tolerate the “click” conditions well. Moreover, the resulting compound can be prepared in a shorter synthesis time (~ 35 min) in contrast to [

18F]SFB (70 min) and in a higher RCY.

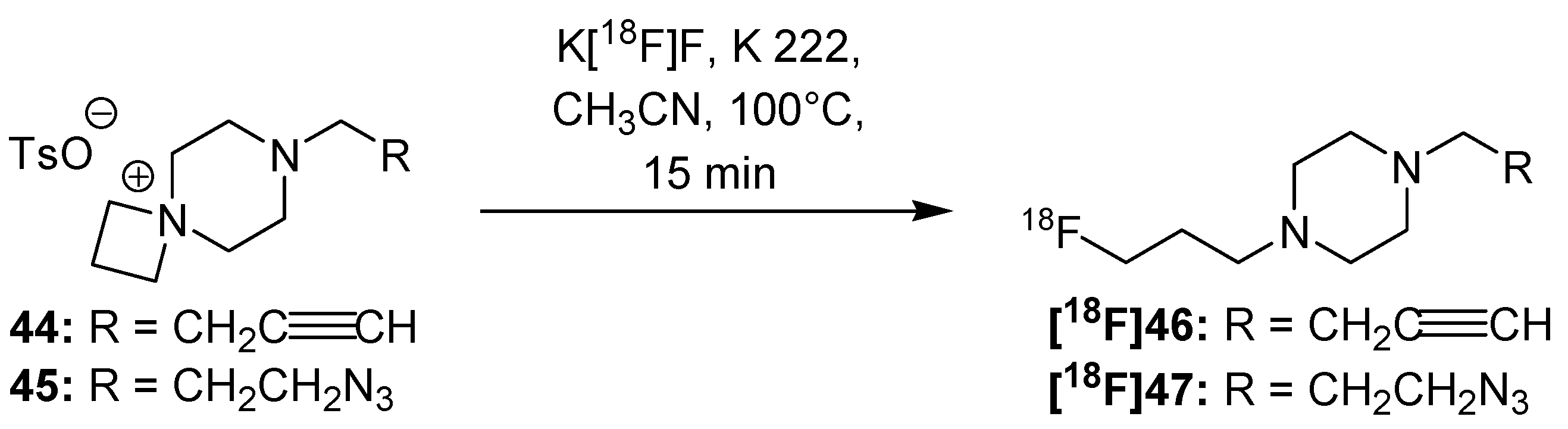

Two novel and universally applicable building blocks BFP

[18F]46 and AFP

[18F]47 were prepared by Pretze

et al. in 2013 (

Scheme 17) [

78]. In addition to the Huisgen-click reaction, it is also possible to apply the Staudinger Ligation as well for radiolabeling purposes when using [

18F]AFP

[18F]47. Furthermore, an automated module synthesis was evaluated for both building blocks. The introduction of spiro salts

44 and

45 as precursors led to a simplified separation and purification from the resulting building blocks via elution using RP18 or Si cartridges in a short timespan.

Scheme 17.

Preparation of BFP [18F]46 and AFP [18F]47.

Scheme 17.

Preparation of BFP [18F]46 and AFP [18F]47.

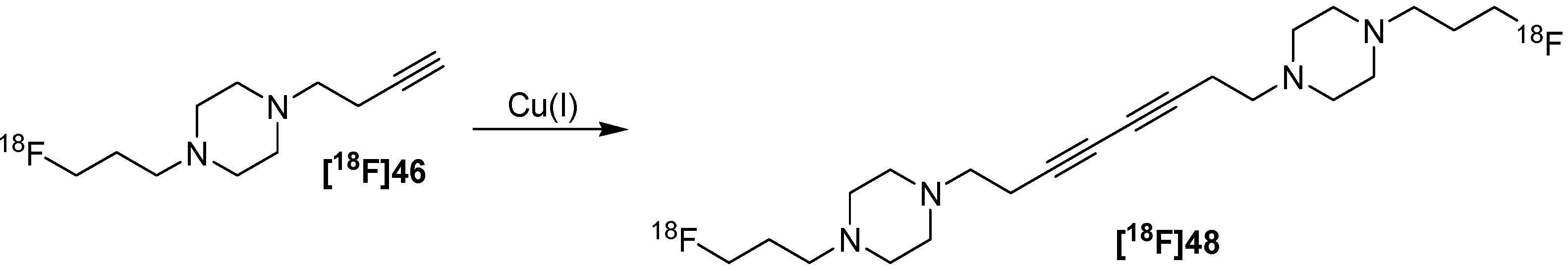

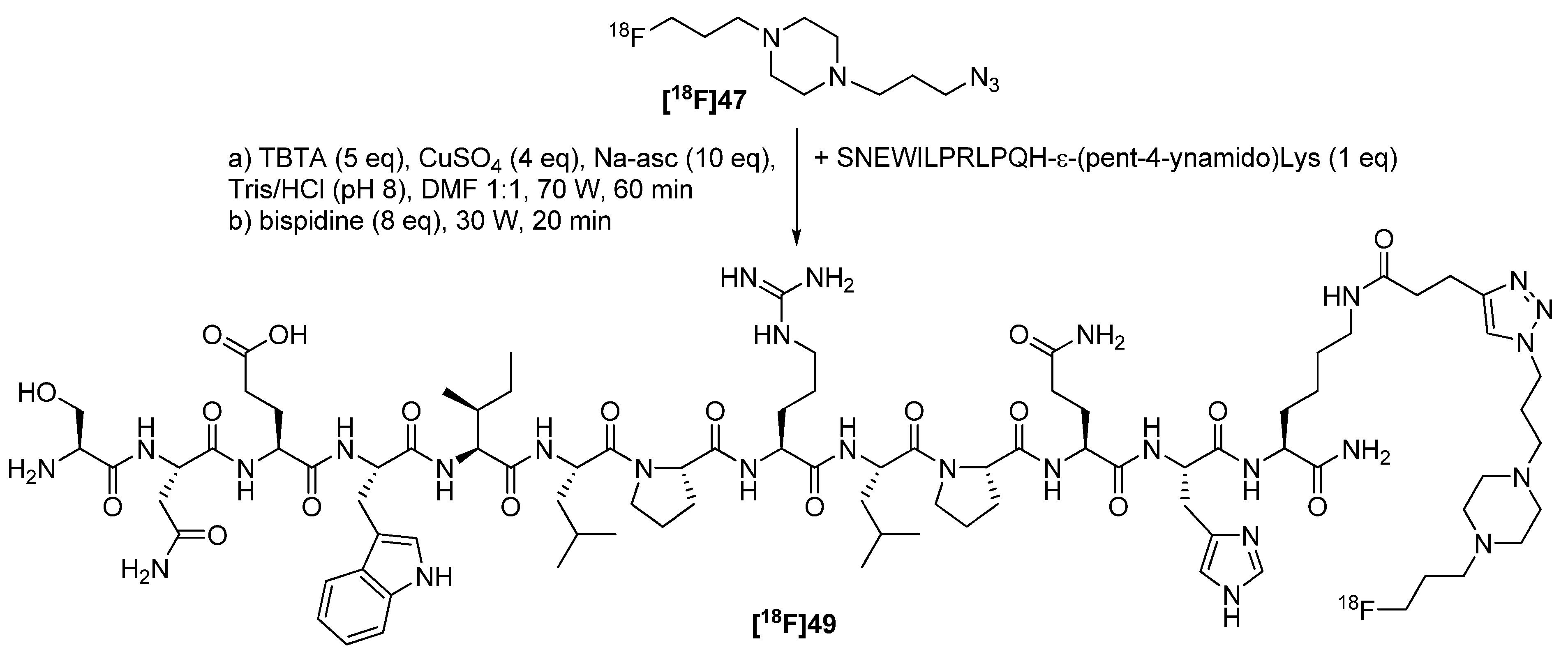

Both building blocks

[18F]46 and

[18F]47 were used for the radiolabeling of azide as well as alkyne functionalized peptides with SNEW sequence for an imaging of the EphB2 receptor [

79]. Problematically, Glaser coupling was observed as a side reaction using [

18F]BFP

[18F]46 for the labeling of peptides (

Scheme 18). To overcome this fact, [

18F]AFP

[18F]47 was used instead and the labeling procedure was accomplished on resin (

Scheme 19). A second important fact is the removal of the copper. It was found that the copper forms strong complexes with this kind of peptides. For this reason, Cu-containing peptides do not behave like “normal” peptides. To fix this obstacle, bispidine [

80], a strong chelating agent, was used to wash the resin after the click reaction, while other chelating agents failed.

Scheme 18.

Glaser coupling with [18F]BFP [18F]46 as side reaction.

Scheme 18.

Glaser coupling with [18F]BFP [18F]46 as side reaction.

Scheme 19.

Radiolabeling of a SNEW peptide using [18F]AFP [18F]47.

Scheme 19.

Radiolabeling of a SNEW peptide using [18F]AFP [18F]47.

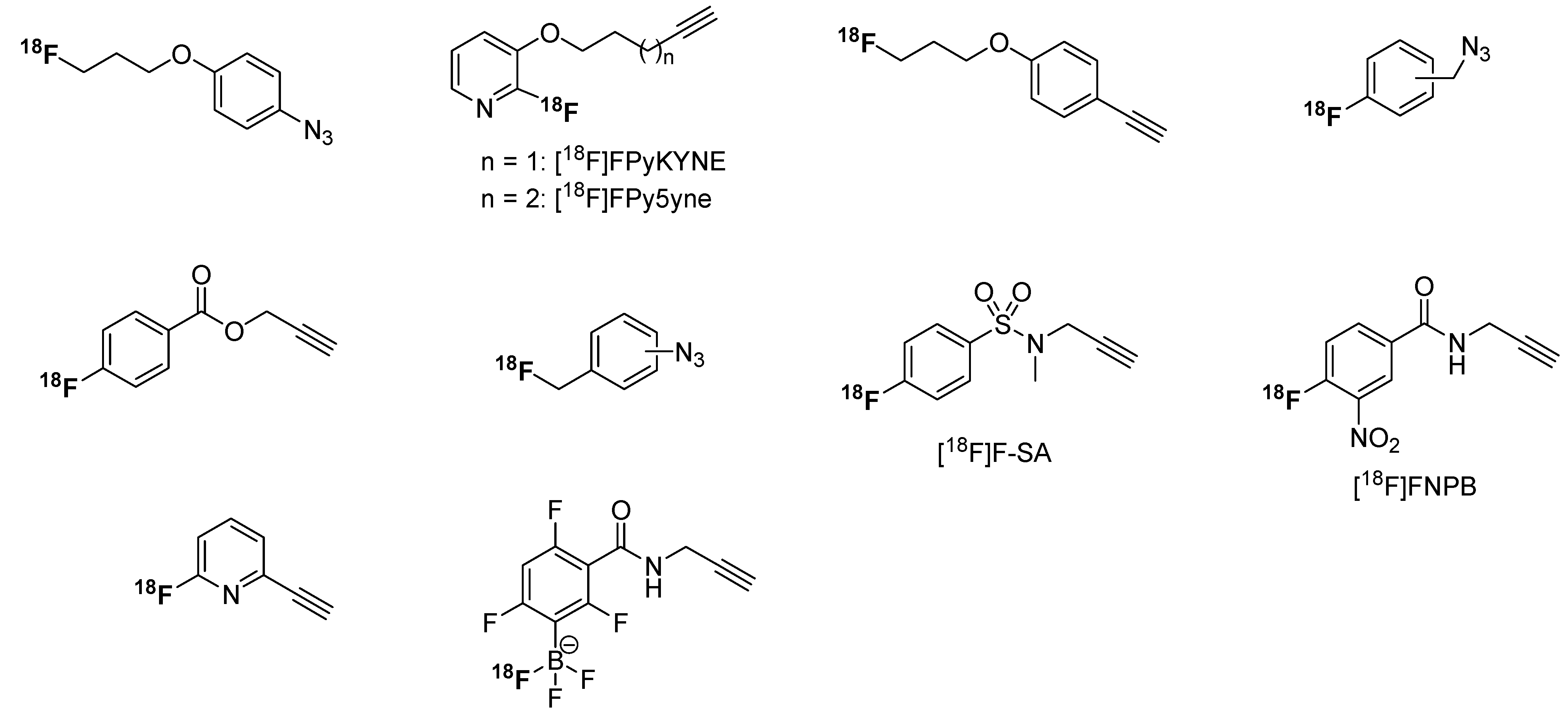

3.3. 18Fluoro-Aryl Building Blocks

The

18F-labeling of aryl precursors is a common task for radiochemists. In general, fluoroaryl compounds possess a higher metabolic stability

in vivo than fluoroalkyl moieties due to the fluorine bound to the sp

2-carbon atom. In most cases, the radiolabeled products show a higher lipophilicity due to the aryl moiety and therefore play a key role in the design of lipophilic radiotracers. A multitude of different aryl click building blocks were evaluated in the past. An overview is shown in

Scheme 20.

Scheme 20.

Overview of [18F]fluoroaryl building blocks.

Scheme 20.

Overview of [18F]fluoroaryl building blocks.

The first approach for the radiofluorination of biomolecules utilizing the sulfonamide-based alkyne 4-[

18F]fluoro-

N-(prop-2-ynyl)benzamide–[

18F]F-SA (

[18F]51) as

18F-labeling building block was presented by Ramenda

et al. in 2007 [

81]. [

18F]F-SA

[18F]51 was synthesized within 80 min including HPLC purification with RCY of 32 ± 5% (RCP > 95%, A

S = 120–570 GBq/µmol) in a remotely controlled module. Next,

[18F]51 was applied for the radiolabeling of an azide functionalized neurotensin(8-13); the labeled peptide was obtained with a RCY = 66% as determined by radio-HPLC. The

in vitro binding affinity (IC

50) of

18F-neurotensin(8-13) derivative was determined to be 66 nM.

Furthermore, the same building block [

18F]F-SA

[18F]51 was applied for

18F-labeling of azide-functionalized human serum albumin (HSA)

52 [

82].

18F-Labeled HSA

[18F]53 was purified via size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and was obtained with a RCY of 55% in a total synthesis time of 120 min starting from [

18F]fluoride (

Scheme 21). Finally, metabolite analyses of

18F-HSA

[18F]53 were accomplished using nude mice. After 120 min, most of the activity was found in the gall bladder, intestines and in the bladder. The half-life of blood activity of

[18F]53 was calculated to be 31 min. Further, the introduction of the azide residue into HSA and subsequent the radiolabeling has significantly altered the structural and functional integrity of HSA.

Scheme 21.

Preparation of [18F]51 and subsequent radiolabeling of HSA 52.

Scheme 21.

Preparation of [18F]51 and subsequent radiolabeling of HSA 52.

In 2013, the same group extended their repertoire and presented the radiolabeling of an azide-modified phosphopeptide (H-Met-Gln-Ser-pThr-Pro-Leu-OH) and an

l-oligonucleotide (17-mer

l-RNA: 5’-CCGCACCGCACAGCCGC-3’) with [

18F]F-SA

[18F]51 [

83]. They pointed out that the lipophilicity (logP 1.7) of [

18F]F-SA

[18F]51 allows radiolabeling in aqueous solutions. After the click reaction, the

18F-phosphopeptide was obtained in 73 to 77% RCY at low precursor amounts (100–400 µg). Additionally, the

18F-labeled oligonucleotide was isolated in 44% RCY as determined by radio-HPLC after 20 min click-reaction time.

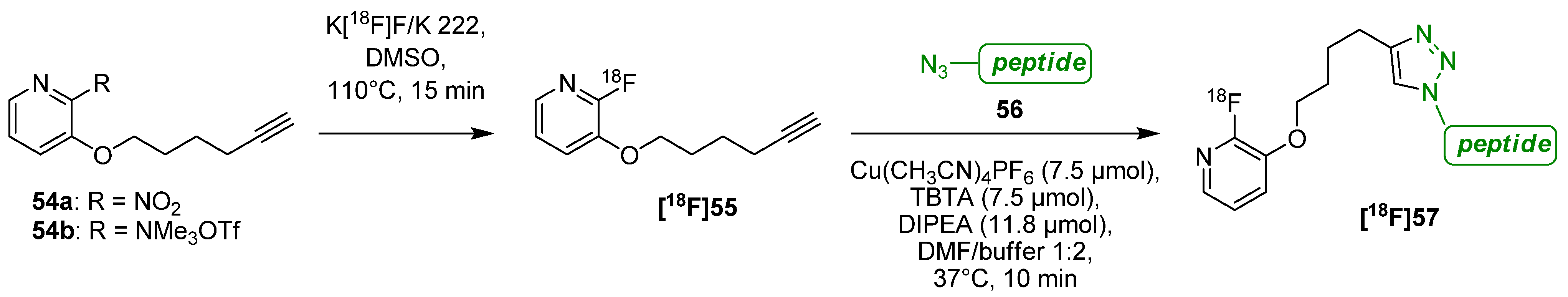

The first approach for radiolabeling with pyridine-based

18F-heteroaryl building blocks was presented by Inkster

et al. in 2008 [

84]. For this purpose, 2-[

18F]fluoro-3-(hex-5-ynyloxy)pyridine–[

18F]FPy5yne (

[18F]55) was prepared via nucleophilic (hetero-)aromatic substitution from either the corresponding 2-nitro or 2-trimethylammonium pyridine

54a,b. Both precursors delivered

[18F]55 in a high RCY of > 90% after 15 min synthesis time and 110 °C in DMSO or acetonitrile. Further, model peptide N

3-(CH

2)

4-CO-Tyr-Lys-Arg-Ile-OH

56 was treated with

[18F]55 under click-conditions to obtain

[18F]57 in a RCY of 18.7% (d.c.) within a total preparation time of 160 min (start of synthesis). Tris(benzyltriazolylmethyl)amine (TBTA) was used as stabilizing agent for Cu(I). Results are summarized in

Scheme 22.

Scheme 22.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]FPy5yne [18F]55 and CuAAC with model peptide 56.

Scheme 22.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]FPy5yne [18F]55 and CuAAC with model peptide 56.

Furthermore, [

18F]FPy5yne

[18F]55 was applied for the first radiofluorination of an azide-functionalized DNA analog [

85]. For that reason, a 5’-azide-modified DNA sequence antisense to

mdr1 mRNA was prepared and treated with

[18F]55 in the presence of TBTA and 2,6-lutidine instead of DIPEA.

18F-Labeled DNA sequence was isolated with 24.6% ± 0.5% RCY (d.c., after EOB) in a shortest preparation time of 276 min from start of synthesis. The copper source was CuBr (99.9999% purity). The DNA sequence antisense to mRNA transcribed by the

mdr1 gene could be used for imaging of breast cancer.

Moreover, the group of Valdivia

et al. presented an approach for the synthesis of 2-[

18F]fluoro-3-pent-4-yn-1-yloxypyridine–[

18F]FPyKYNE which is one CH

2 group shorter than the aforementioned [

18F]FPy5yne

[18F]55. An automated synthesis procedure was evaluated for [

18F]FPyKYNE and the subsequent radiolabeling of an RGD peptide. The labeled peptide was obtained in a total RCY of 12–18% with a RCP > 99% after 125 min in a two-step, two-reactor process [

86].

Finally, 6-[

18F]fluoro-2-ethynylpyridine

[18F]59 was prepared as the third heteroaromatic example from the corresponding bromo precursor

58 within 10 min at 130°C with a RCY of 27.5 ± 6.6% (d.c.) with high RCP ≥ 98% by Daumar

et al. in 2012 [

87]. A

d-amino acid analogue of WT-pHLIP and an

l-amino acid peptide K-pHLIP were used, both functionalized at the

N-terminus with 6-azidohexanoic acid. The subsequent click-labeling was performed at 70 °C in a mixture of water and ethanol using Cu-acetate and sodium ascorbate (

Scheme 23). [

18F]-

d-WT-pHLIP

[18F]61a and [

18F]-

l-K-pHLIP

[18F]61b were obtained with RCYs between 5−20% after HPLC purification in a total reaction time of 85 min including the formulation for the biological evaluation.

In vitro stability tests in human and mouse plasma revealed high stability. After 120 min, 65% of

[18F]61a and 85% of

[18F]61b remained intact. PET imaging and biodistribution studies in LNCaP and PC-3 xenografted mice revealed pH-dependent tumor retention.

Scheme 23.

18F-labeling procedure for two pHLIP peptide analogs [18F]61a and [18F]61b.

Scheme 23.

18F-labeling procedure for two pHLIP peptide analogs [18F]61a and [18F]61b.

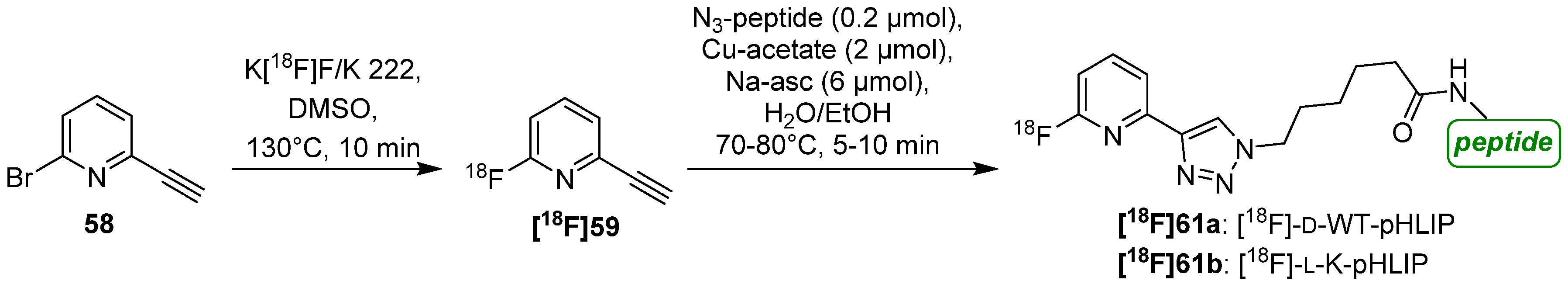

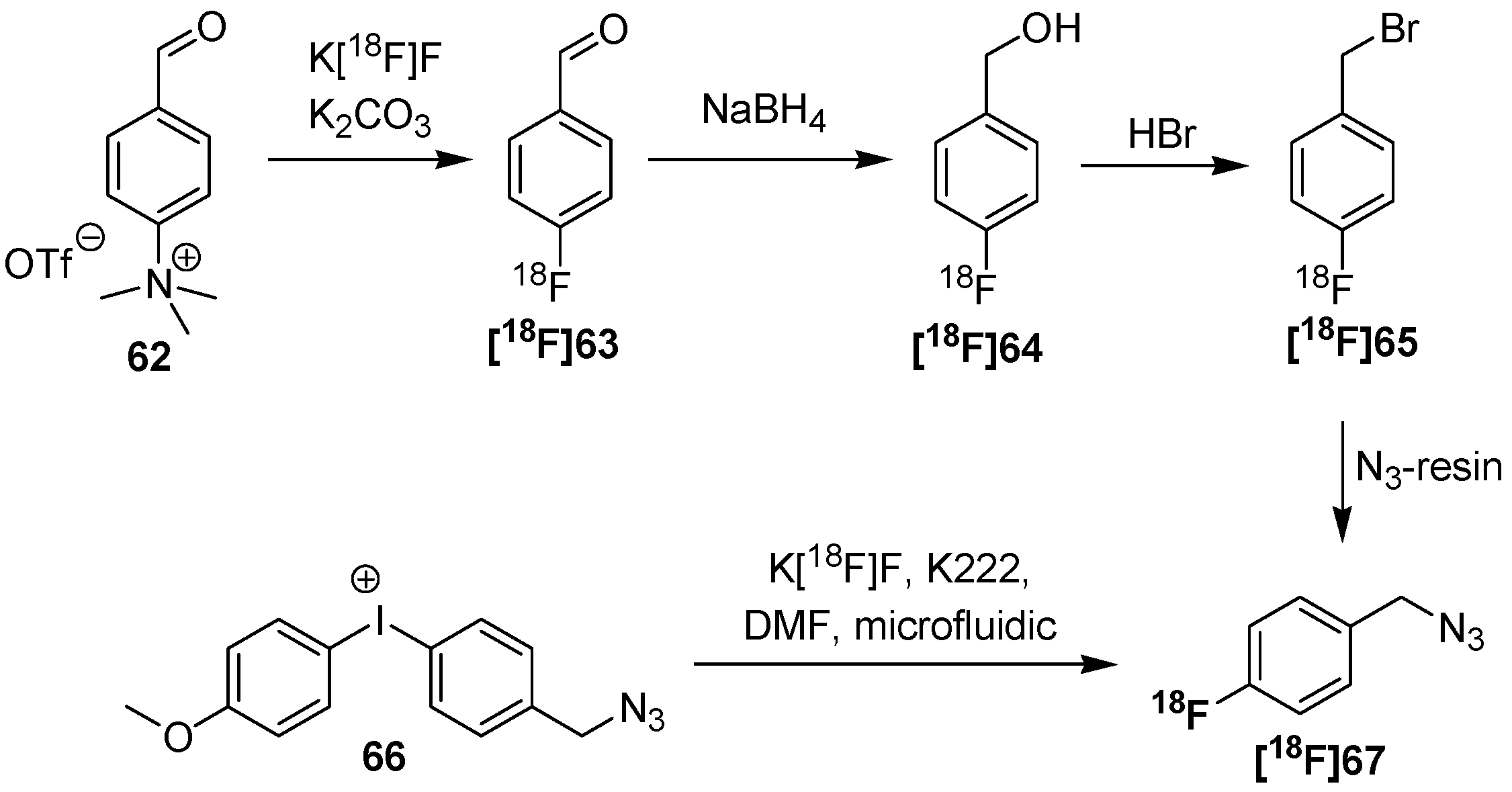

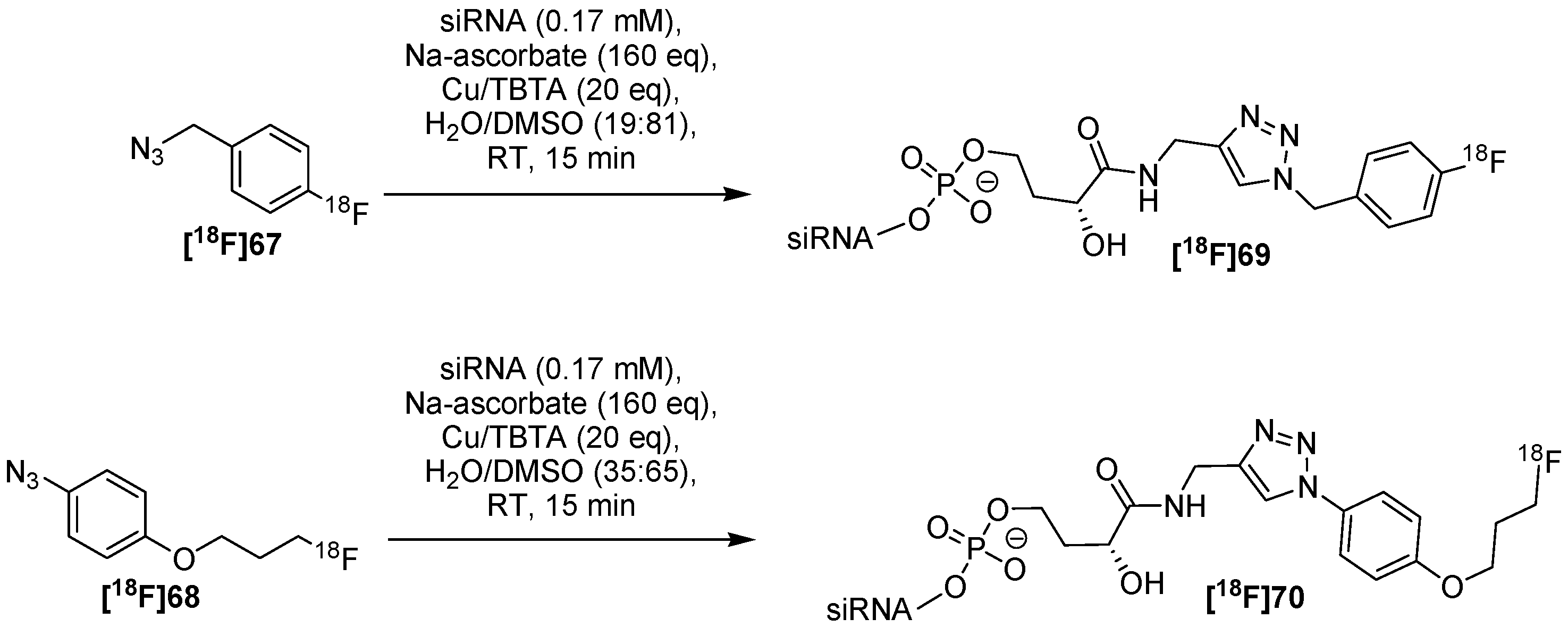

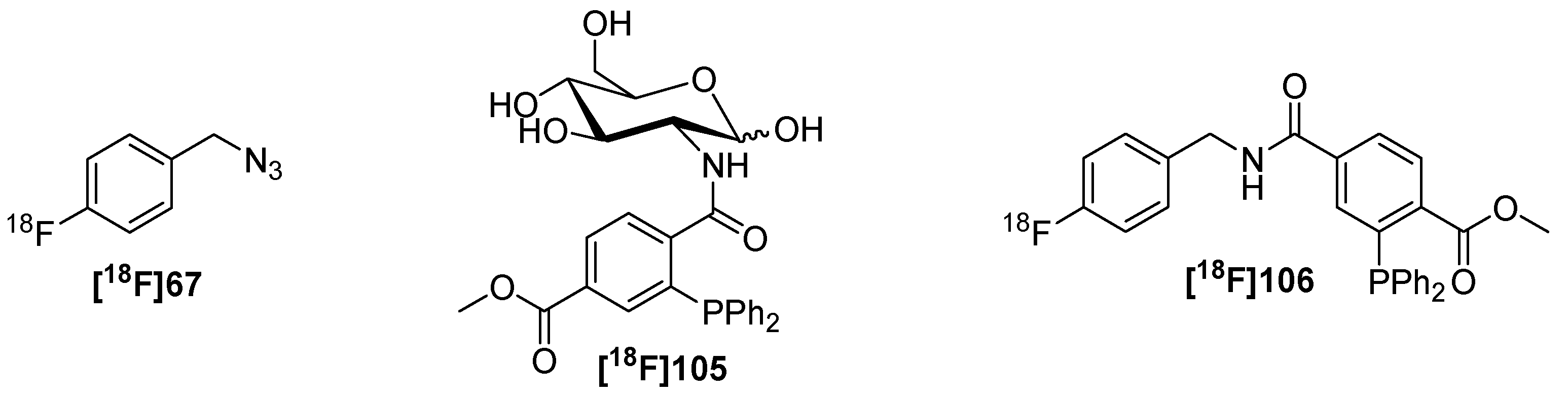

Next, two approaches for the preparation of (azidomethyl)-[

18F]fluorobenzenes like

[18F]67 were presented by Thonon

et al. [

88] and Chun

et al. [

89] (

Scheme 24). The first group used a four-step synthesis path starting from 4-trimethylammonium benzaldehyde (

62). Fluorine-18 was introduced in the first step followed by reduction of the aldehyde

[18F]63, conversion into the bromo compound

[18F]65 and final functionalization with azide. 34% RCY (d.c.) of

[18F]67 could be obtained within 75 min starting from [

18F]fluoride. The second group used a single step strategy. Thus, diaryliodonium salts like

66 were introduced as precursor. Electron-rich aryl moieties, such as a 4-methoxyphenyl or 2-thienyl, are generally known to direct the [

18F]fluoride into the other relatively electron-deficient ring of this diaryliodonium salt [

90]. Each precursor was subjected to labeling with [

18F]fluoride (n.c.a.) in the microfluidic device. The respective building blocks were obtained after 94−188 s in high RCY’s (35−45% for

[18F]67) (d.c.) whereas the by-product was only formed in <3%.

Scheme 24.

Comparison between labeling of trimethylammonium precursors and diaryliodonium salts.

Scheme 24.

Comparison between labeling of trimethylammonium precursors and diaryliodonium salts.

The group of Thonon

et al. [

88] used

[18F]67 for subsequent click labeling of a 4-ethynyl-l-phenylalanine-containing peptide. For this purpose, the click-conditions were optimized and the ligation reaction was finished in less than 15 min. Later in 2011, the same group presented a general method for the labeling of siRNA [

91]. Two complementary building blocks 1-(azidomethyl)-4-[

18F]fluorobenzene

[18F]67 and 1-azido-4-(3-[

18F]fluoropropoxy)benzene

[18F]68 have been produced with 41% and 35% RCY (d.c.), respectively. The whole labeling procedure takes 120 min with a RCY of 15 ± 5% (d.c.) for both pure [

18F]siRNA derivatives

[18F]69 and

[18F]70 (

Scheme 25).

Scheme 25.

Labeling procedure of siRNA [18F]69 and [18F]70.

Scheme 25.

Labeling procedure of siRNA [18F]69 and [18F]70.

In 2012, Flagothier

et al. investigated the influence of the linkers connected to the oligonucleotides and presented a new alkyne-functionalized linker for siRNA [

92]. For subsequent labeling purposes,

[18F]67 was prepared in 45 min with 84% RCY using a remotely controlled device (GE Fastlab

®). The siRNA concentration was used in a low concentration of about 10

-5 M and represents an important advantage of the method considering the high cost of this precursor. [

18F]siRNA was prepared under the same conditions as pointed out by Mercier

et al. [

91] in a comparable RCY of 12%.

Next, two further labeling building blocks based on the 4-[

18F]fluorobenzoate skeleton were developed. First, propargyl 4-[

18F]fluorobenzoate–[

18F]PFB was prepared by the group of Vaidyanathan

et al. from the respective trimethylammonium precursor in a RCY of 58 ± 31% (d.c.) within 15 min. Afterwards, several model compounds and a transglutaminase-reactive peptide (RCY = 37 ± 31%) were labeled using [

18F]PFB [

93]. The second approach consists of the preparation of 4-[

18F]fluoro-3-nitro-

N-2-propyn-1-yl-benzamide – [

18F]FNPB published by Li

et al. in 2012 [

94]. [

18F]FNPB was synthesized with a RCY of 58% (A

S > 350 GBq/µmol, RCP > 98%) within 40 min.

In vitro stability tests using mouse plasma revealed no radiodefluorination over 2 h. Afterwards, three different azide-modified peptides were labeled with RCYs between 87 and 93%.

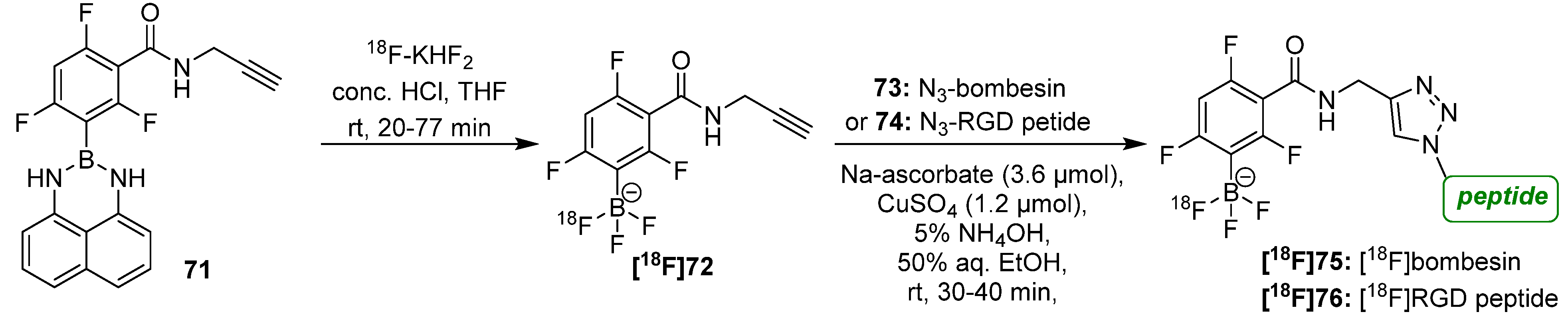

Further, an unconventional and promising approach was introduced by Li

et al. in 2013 consisting of a radiolabeling procedure using alkyne functionalized aryltrifluoroborate

[18F]72 and either azide-modified bombesin

73 or RGD peptide

74 [

95,

96]. Advantageously, arylboronates like

71 capture [

18F]fluoride directly and rapidly under aqueous conditions (20 min, 20–40°C, pH 2–3, then quench to pH 7.5) under formation of a water-soluble, non-coordinating aryltrifluoroborate anion

[18F]72 that is highly polar (logP < −4). The alkyne-[

18F]ArBF

3− [18F]72 was subsequently conjugated to both peptides within 25 min without need for prior work-up in this two-step one-pot procedure (

Scheme 26).

Scheme 26.

Arylboronate [18F]72 used for radiofluorination purposes.

Scheme 26.

Arylboronate [18F]72 used for radiofluorination purposes.

Later, the specific activity for the building block as well as for the labeled peptides was improved. This was possible due to the stoichiometry of the introduction of n.c.a. [

18F]fluoride into the precursor. Investigations to determine the A

S were done using a rhodamine-N

3 conjugate. After this improvement, it was possible to prepare alkyne-[

18F]ArBF

3− [18F]72 with a A

S = 148 GBq/μmol and the resulting RGD peptide

[18F]76 with a A

S = 444 GBq/μmol. The tumor-uptake and corresponding good PET imaging of both peptides was accompanied by a three times higher A

S which was statistically verified [

97].

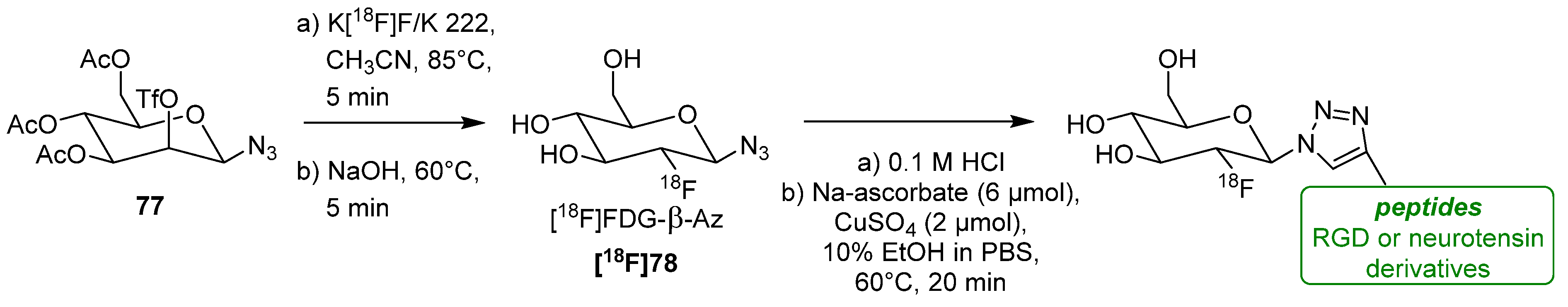

3.4. 18Fluoro-Gluco-Derivatives

The glycosylation of peptides represents an important tool for the enhancement of their

in vivo behavior like blood clearance and stability. For this reason, labeling building blocks based on carbohydrates for the glycosylation of potential radiotracers using the CuAAC were evaluated by Maschauer and Prante in 2009 [

98]. In this context, different α- and β-anomeric azides and alkynes were designed for radiolabeling purposes. They demonstrated that the radiolabeling of triflated precursors with fluorine-18 proceed better when using β-anomeric derivatives like

77 (RCY of

[18F]78 was 71 ± 10%). Afterwards, a proof-of-principle reaction of the

18F-building block

[18F]78 was accomplished by labeling Fmoc-

l-propargylglycine with a RCY of 60% for unprotected building block and a RCY of 76% for the peracetylated building block.

Finally in 2010, they applied

[18F]78 as the building block with the highest RCY to label different peptide moieties like RGD or neurotensin derivatized with

l-propargylglycine (

Scheme 27). RCYs ranged from 17 to 20% and A

S = 55–210 GBq/µmol were obtained for the labeled conjugates in a total synthesis time of 75 min [

99]. Furthermore,

in vivo investigations with the [

18F]FGlc-RGD peptide were carried out using U87MG-bearing mice. Because of the glycosylation they had a better blood clearance and stability in α

vβ

3-integrin expressing tumors. The specific tumor uptake of [

18F]FGlc-RGD was 0.49% ID/g (60 min p.i.).

Scheme 27.

Preparation of mannopyranosyl azide 77 and subsequent 18F-glycosylation with [18F]78.

Scheme 27.

Preparation of mannopyranosyl azide 77 and subsequent 18F-glycosylation with [18F]78.

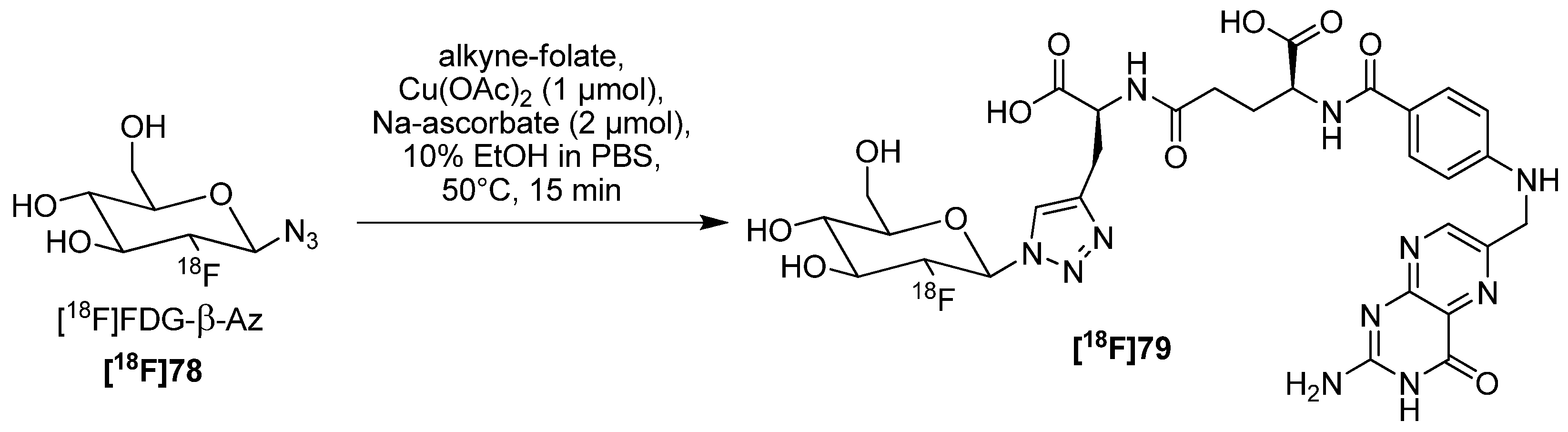

In 2012, Fischer

et al. adapted this method to label a novel folic acid conjugate in order to image the folate receptor, which is overexpressed in various tumor entities [

100]. After 3 h of synthesis, [

18F]fluorodeoxyglucosyl folate

[18F]79 was obtained in RCY = 5−25% (d.c.), with a A

S = 90 ± 38 GBq/μmol and a RCP > 95% (

Scheme 28). The biodistribution and PET imaging studies in KB tumor-bearing mice showed a high and specific uptake of the radiotracer in FR-positive tumors (10.03 ± 1.12% ID/g, 60 min p.i.) and kidneys (42.94 ± 2.04% ID/g, 60 min p.i.).

Scheme 28.

18F-glycosylation of a folate derivative.

Scheme 28.

18F-glycosylation of a folate derivative.

4. Strain-Promoted Huisgen Cycloaddition

Strain-promoted and copper-free variants of the Huisgen cycloaddition of cyclic alkynes with azides are of great interest as powerful tools in reagent/catalyst-free bioconjugations. This type of reaction was applied especially for labeling purposes on living cells or

in vivo studies due to the mild reaction conditions and the bioorthogonal character expressed by a high specificity and selectivity. Advantageously, the use of cytotoxic Cu(I) was not mandatory in contrast to the CuAAC. Cyclooctyne is the smallest stable cyclic alkyne and has a high reaction potential to react with azides as demonstrated by Blomquist and Liu in 1953 [

101] and by Wittig and Krebs in 1961 [

102]. The first connection of this type of click-reaction with cyclooctyne connected with a biological application was recognized by Agard

et al. in 2004 [

103].

With the entry of copper-free 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions in radiopharmacy, several strain-promoted systems, such as cyclooctynes and dibenzocyclooctynes, have been developed for the incorporation of fluorine-18. Additionally, a few examples of radiometal labeling were reported [

104].

In general, two strategies were pointed out. The first comprises the preparation of fluorine-18-containing cyclooctyne derivatives which were applied for radiolabeling of azide-functionalized molecules of interest. Alongside, 18F-azide building blocks were synthesized and used for the labeling of cyclooctyne-bearing bioactive compounds. In general, two regioisomers are obtained in both strategies of this reaction which could indicate a different biological behavior in certain circumstances depending on the remaining molecule residue.

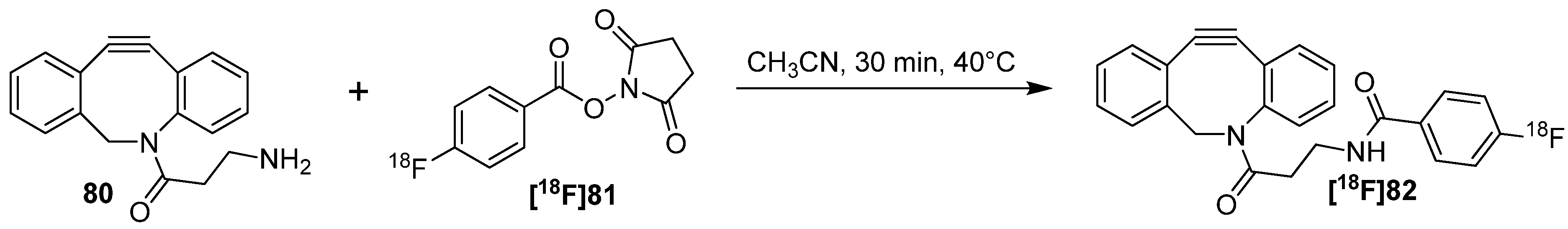

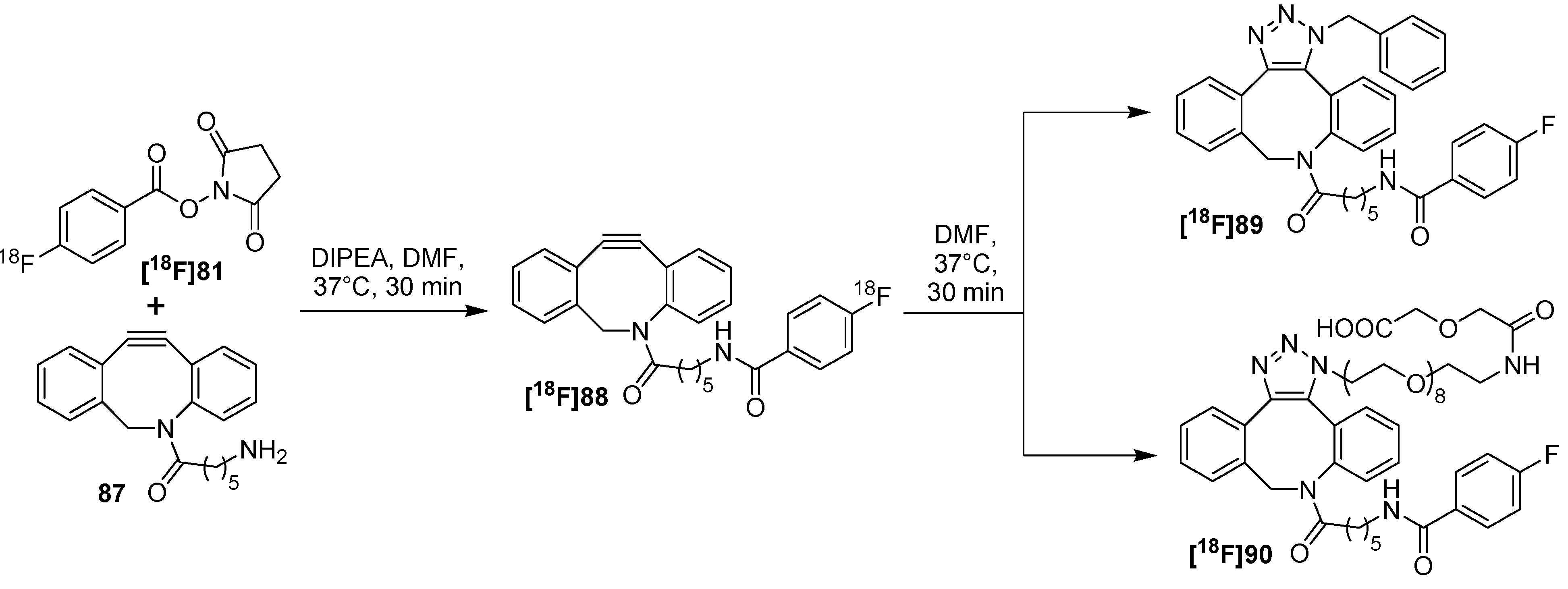

The first example of a biological application in combination with

18F-radiolabeling was published in 2011 by Bouvet

et al. [

105]. Thus, a fluorine-18-labeled aza-dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) building block

[18F]82 was synthesized through acylation of commercially available

N-(3-amino-propionyl)-5,6-dihydro-11,12-didehydrodibenzo-[

b,

f]azocine (

80) with

N-succinimidyl 4-[

18F]fluoro-benzoate–[

18F]SFB (

[18F]81) (

Scheme 29). For this purpose, amino compound

80 and [

18F]SFB

[18F]81 were dissolved in acetonitrile and reacted for 30 min at 40 °C monitored by radio-HPLC. After separation using semipreparative radio-HPLC, cyclooctyne

[18F]82 was obtained with a RCY of 85% and a RCP > 95%. To determine the

in vivo stability of

[18F]82, metabolite analyses was performed using Balb/C mice. After 60 min p.i., 60% of compound

[18F]82 was still intact. Further, dynamic small animal PET studies showed rapid clearance of [

18F]FB-DBCO

[18F]82 from the blood (blood clearance half-life: 53 s) and from most other tissues and organs. Most activity was found in the bladder, gall bladder and intestines.

Scheme 29.

[18F]Fluorobenzoate-functionalization of DBCO 80.

Scheme 29.

[18F]Fluorobenzoate-functionalization of DBCO 80.

Subsequently, various azide-functionalized sample molecules and bioactive compounds of interest like carbohydrates and geldanamycine were conjugated and radiolabeled with

[18F]82 (for an overview see

Scheme 30). For the preparation of the non-radioactive references, 1.5 to 2.0 equiv. of respective azides were treated with 1 equiv. of FB-DBCO. All reactions resulted in the formation of two distinct regioisomers (1,4- and 1,5-triazole regioisomer). Products were isolated using HPLC-purification; but in some cases both regioisomers were not separable. Five different reaction conditions were tested for the radiolabeling procedure with

[18F]82 (a: methanol, room temperature, 15 min; b: phosphate buffer, 40 °C, 30 min; c: 3.50% bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution in water, room temperature, 60 min; d: DMSO/water (1/1), 40 °C, 60 min.; e: water, 40 °C, 30 min) and all tracers were obtained in 69−98% RCY (determined by radio-TLC).

Scheme 30.

Scope of the labeling reaction with [18F]80.

Scheme 30.

Scope of the labeling reaction with [18F]80.

Furthermore, the work of Carpenter

et al. was focused on the synthesis of a new

18F-labeled cyclooctyne building block [

106] based on ADIBO which was recently synthesized by Popik

et al. [

107]. They used a 6-aminohexamido spacer and [

18F]SFB

[18F]81 for the introduction of fluorine-18 into the building block. After purification via a C

18-SPE cartridge, the

18F-labeled cyclooctyne

[18F]88 was obtained in 64 ± 15% RCY and > 80% RCP. As proof-of-principle, the following click-reaction was tested with benzyl azide and an azido-functionalized PEGylated acid at 37 °C in DMF to form the two regioisomers (ratio 1:1)

[18F]89 (74% RCY after 1 h) and

[18F]90 (64% after 2 h) (

Scheme 31). HPLC-purified cyclooctyne

[18F]88 and triazoles

[18F]89 and

[18F]90 showed no decomposition or radiolysis over 6 h. Moreover, the stability of these products in PBS/saline buffer as well as in rat serum was tested. After 1 h, over 98% of intact radiotracer was found for both in rat serum. Additionally, formulations of both radiotracers were stable over 4 h in buffer.

In 2013, the same group evaluated an integrin α

vβ

6-specific peptide and labeled it with fluorine-18 using this click-chemistry approach on the basis of the previously shown results. For that purpose, peptide N

3-PEG

7-A20FMDV2 (

91) was yielded after azide-modification and preparation via solid-phase peptide synthesis [

108]. Peptide

91 selectively targets the integrin α

vβ

6-receptor which is located at the cell surface and has been identified as a prognostic indicator for several cancer entities [

109,

110].

Scheme 31.

Labeling scheme for the labeling with [18F]88.

Scheme 31.

Labeling scheme for the labeling with [18F]88.

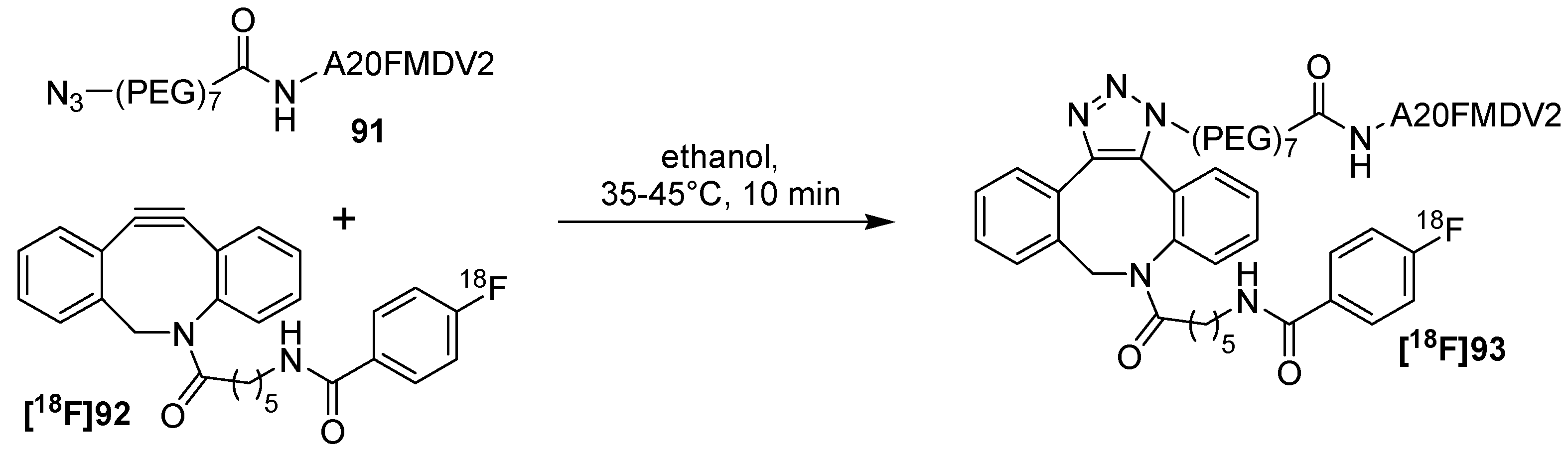

The click-reaction for the preparation of radiolabeled peptide

[18F]93 was performed in ethanol by treating peptide-precursor

91 with building block

[18F]92 for 10 min at 35–45°C (

Scheme 32). After HPLC-purification,

[18F]93 was obtained as a regioisomeric mixture with 11.9% RCY (based on

[18F]92) with > 99% RCP and with a A

S of 68 ± 25 GBq/μmol. The nonradioactive standard

[19F]93 was prepared from HPLC-purified [

19F]FBA-C6-ADIBO

[19F]92 and N

3-PEG

7-A20FMDV2 (

91) in 69% yield. Thus, equimolar amounts of the azide and the alkyne were combined in DMF and stirred at rt. Next, the

in vitro stability of

[18F]93 was tested. After 60 min 94.6% of the tracer remained stable in rat serum, but after 2 h 80% of intact tracer was found. Cell binding studies of

[18F]93 revealed a strong α

vβ

6-targeted binding (DX3puroβ6 cells, 15 min: 43.2% binding).

In vivo studies using a mouse model demonstrated low binding to the DX3puroβ6-tumor (1 h: 0.47 ± 0.28% ID/g, 4 h: 0.14 ± 0.09% ID/g) and clearing from the bloodstream resulted via the renal and hepatobiliary routes. These results can be explained with the undesirable effects on pharmacokinetics which were expressed by the high lipophilicity and the large size of the labeling prosthetic group.

Scheme 32.

Labeling of N3-PEG7-A20FMDV2 (91) with [18F]FBA-C6-ADIBO [18F]92.

Scheme 32.

Labeling of N3-PEG7-A20FMDV2 (91) with [18F]FBA-C6-ADIBO [18F]92.

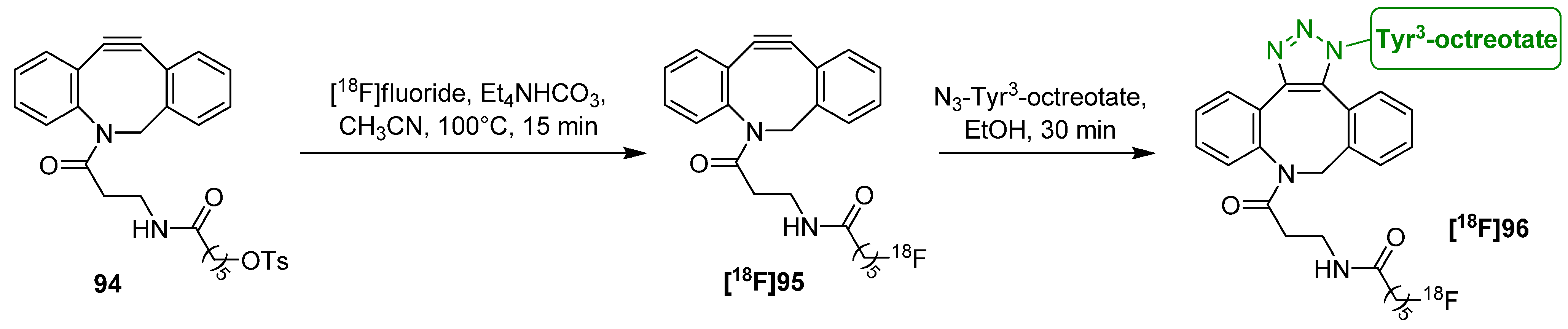

The next publication regards the preparation of [

18F]ADIBO

[18F]95 by direct radiolabeling with [

18F]fluoride [

111]. Thus, ADIBO was modified with a 6-tosyloxyhexanoyl residue. Labeling was carried out via nucleophilic introduction of [

18F]fluoride in the presence of Et

4NHCO

3 in acetonitrile at 100 °C for 15 min. [

18F]ADIBO

[18F]95 was obtained in a RCY of 65%. Subsequent radiolabeling of an azide-functionalized Tyr

3-octreotate (TATE) peptide was accomplished in ethanol. More than 95% of

[18F]95 was converted into

[18F]96 after 30 min (

Scheme 33).

Scheme 33.

Preparation of [18F]ADIBO [18F]95 and labeling of Tyr3-octreotate.

Scheme 33.

Preparation of [18F]ADIBO [18F]95 and labeling of Tyr3-octreotate.

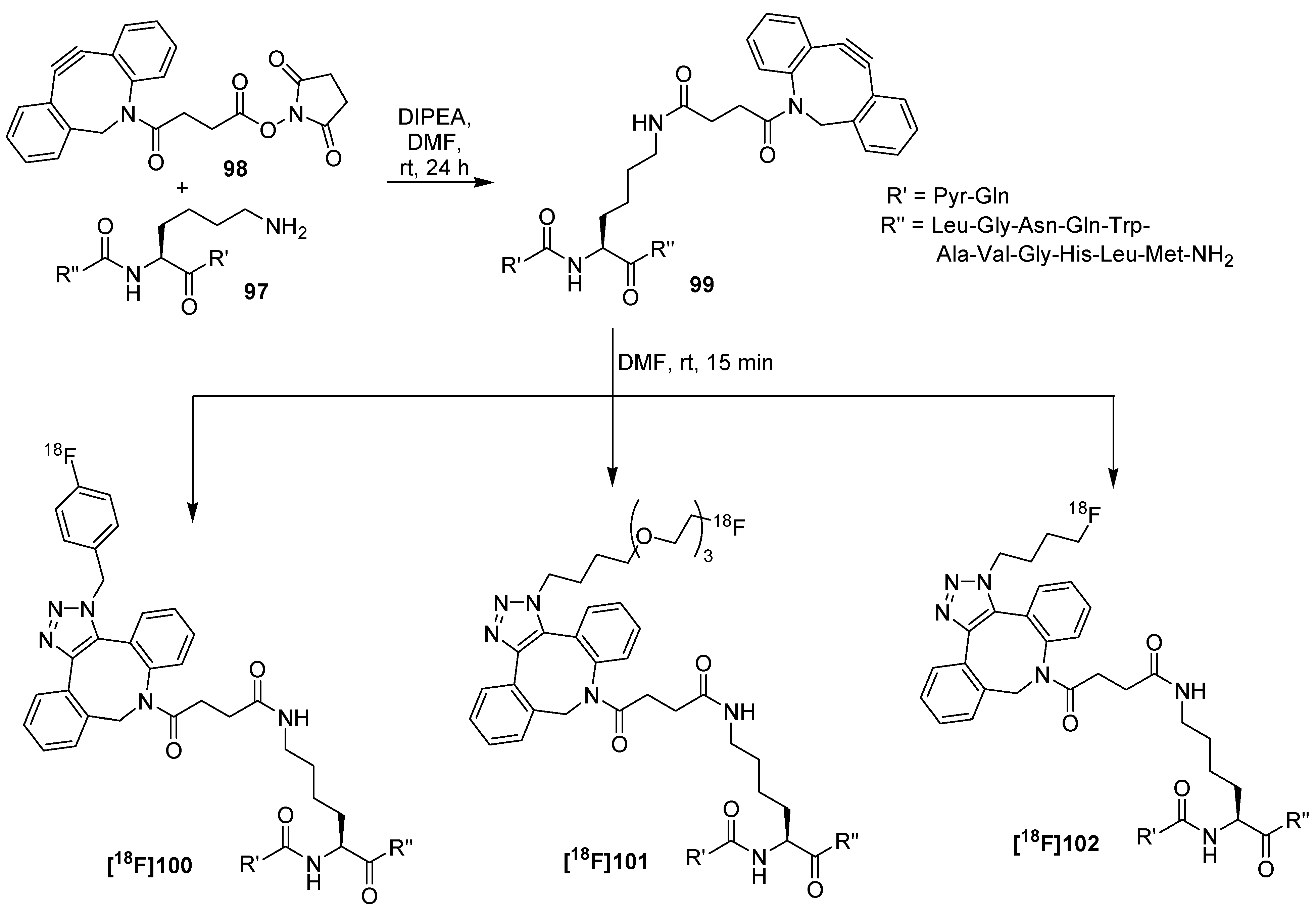

All following works used a change of functionalities to

18F-labeled azides which underwent a click-reaction with different cyclooctynes connected to the bioactive molecule of interest. The advantage of labeled azides is their versatile applicability. They can be used for Cu-mediated click-reaction, the variants of the Staudinger Ligation and for copper-free click reaction with cyclooctyne. To demonstrate the versatility, the group of Campbell-Verduyn

et al. [

112] modified lys[

3]-bombesin

97 with aza-dibenzocyclooctyne

98 which was previously functionalized with a succinimidyl ester. Resulting peptide

99 was then reacted with three different fluorine-18-containing azides at room temperature for 15 min in DMF with radiochemical yields of 19−37% (

Scheme 34). The binding affinities of these labeled bombesin-derivatives to gastrin-releasing peptide receptors were determined using human PC3 prostate cancer cells which revealed a high affinity despite the modifications (IC

50 values: 29 nM to 40 nM).

Scheme 34.

Preparation of Aza-DBCO-bombesin 99 and radiolabeling with three 18F-building blocks.

Scheme 34.

Preparation of Aza-DBCO-bombesin 99 and radiolabeling with three 18F-building blocks.

In 2012, Evans and co-workers demonstrated that CFC reactions can be carried out between [

18F]fluoroethylazide (

[18F]33) and five derivatives with different cyclooctyne scaffolds as pointed out in

Scheme 35 [

113]. The process of radiolabeling was optimized. Highest RCYs were obtained when using acetonitrile as solvent, a reaction time of 15 min, and a temperature of 90 °C. In addition, the biological behavior of

[18F]33 was analyzed using BALB/c nude mice.

Scheme 35.

Cyclooctyne moieties for the radiolabeling with [18F]fluoroethylazide ([18F]33).

Scheme 35.

Cyclooctyne moieties for the radiolabeling with [18F]fluoroethylazide ([18F]33).

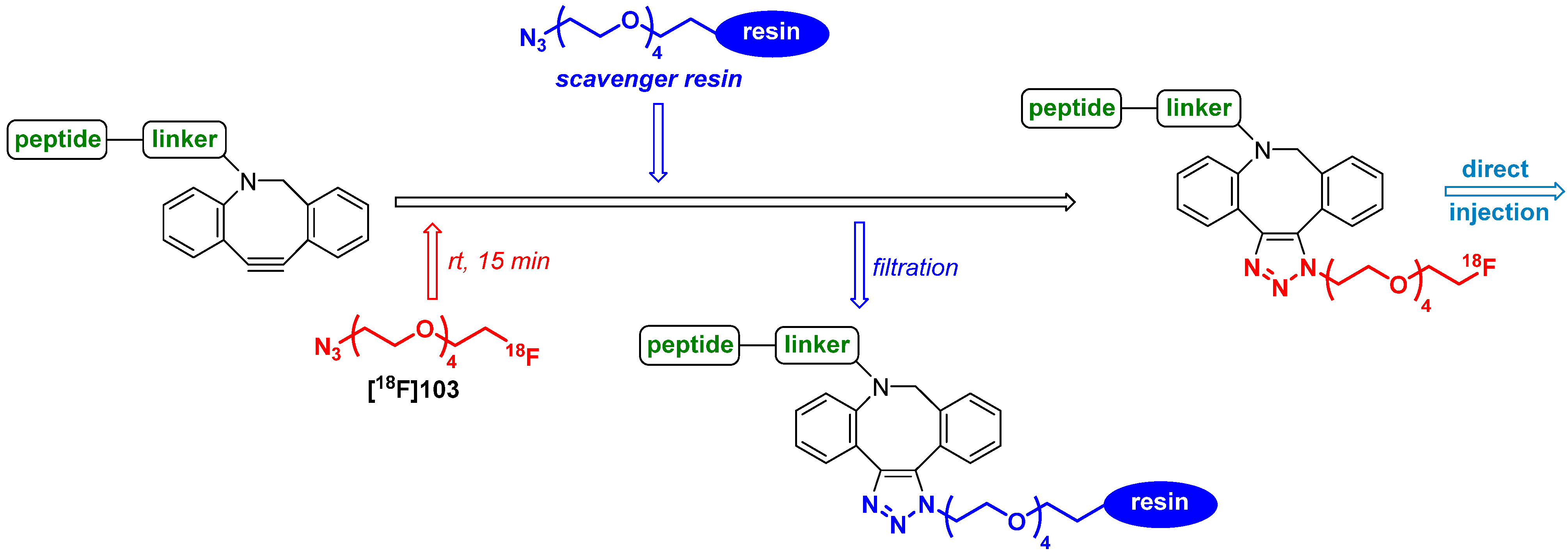

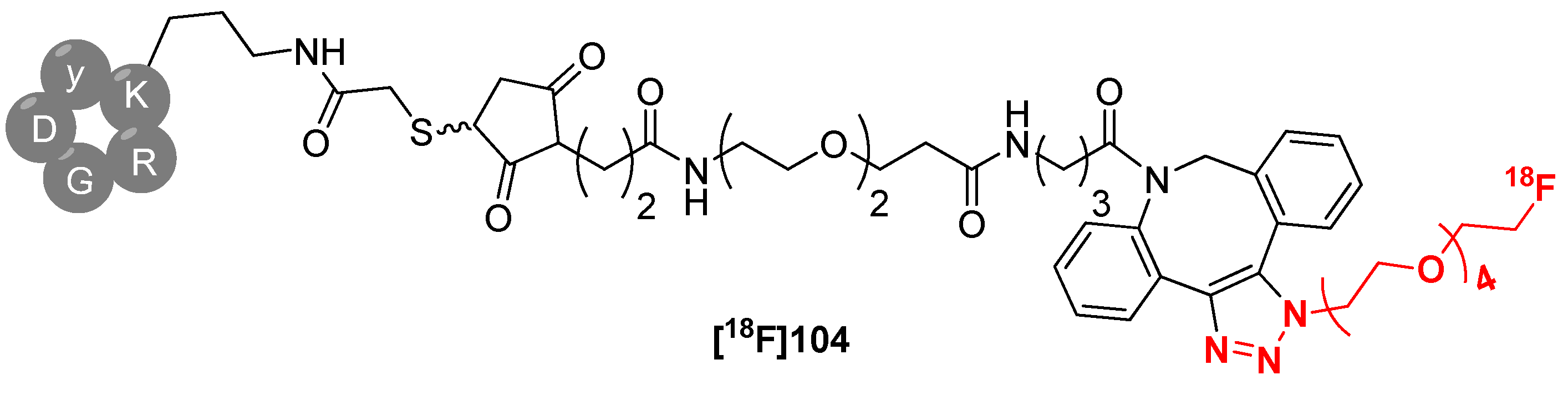

The group of Kim

et al. presented a protocol for the radiolabeling of peptides with fluorine-18 under physiological reaction conditions [

114]. Four fluorine-18-labeled biologically active peptides for tumor targeting such as cyclic Arg-Gly-Asp (cRGD) peptide, bombesin (BBN), c-Met binding peptide (cMBP) and apoptosis targeting peptide (ApoPep) were employed for this purpose. Advantageously, the resulting

18F-peptides were provided as direct injectable solutions without any HPLC purification and/or formulation processes due to the application of a novel azide-functionalized scavanger resin after the labeling procedure. The remaining cyclooctyne precursor was cached with the azide-functionalized resin for purification purposes; the overview is given in

Scheme 36.

Scheme 36.

Overview of the general labeling and purification procedure.

Scheme 36.

Overview of the general labeling and purification procedure.

In the first step, the desired peptides (cyclic Arg-Gly-Asp (cRGD) peptide, bombesin (BBN), c-Met binding peptide (cMBP) and apoptosis targeting peptide (ApoPep)) were modified with the cyclooctyne moiety. The next step involved the radiolabeling with

[18F]103 in an ethanol/water mixture (v/v = 1/1) at ambient temperature for 15 min. Afterwards, the azide-functionalized scavenger resin was added and the mixture maintained for 20 min to allow the remaining ADIBO-peptide to conjugate with the resin. After filtration and washing of the resin with PBS solution, all peptides were produced within approx. 35 min total reaction time in 92% RCY (d.c. for

[18F]104) with > 98% of RCP as a direct injectable solution for further studies without any HPLC purification. cRGD-ADIBOT-

18F

[18F]104 was shown as a representative example in

Scheme 37.

Scheme 37.

cRGD-ADIBOT-18F [18F]104.

Scheme 37.

cRGD-ADIBOT-18F [18F]104.

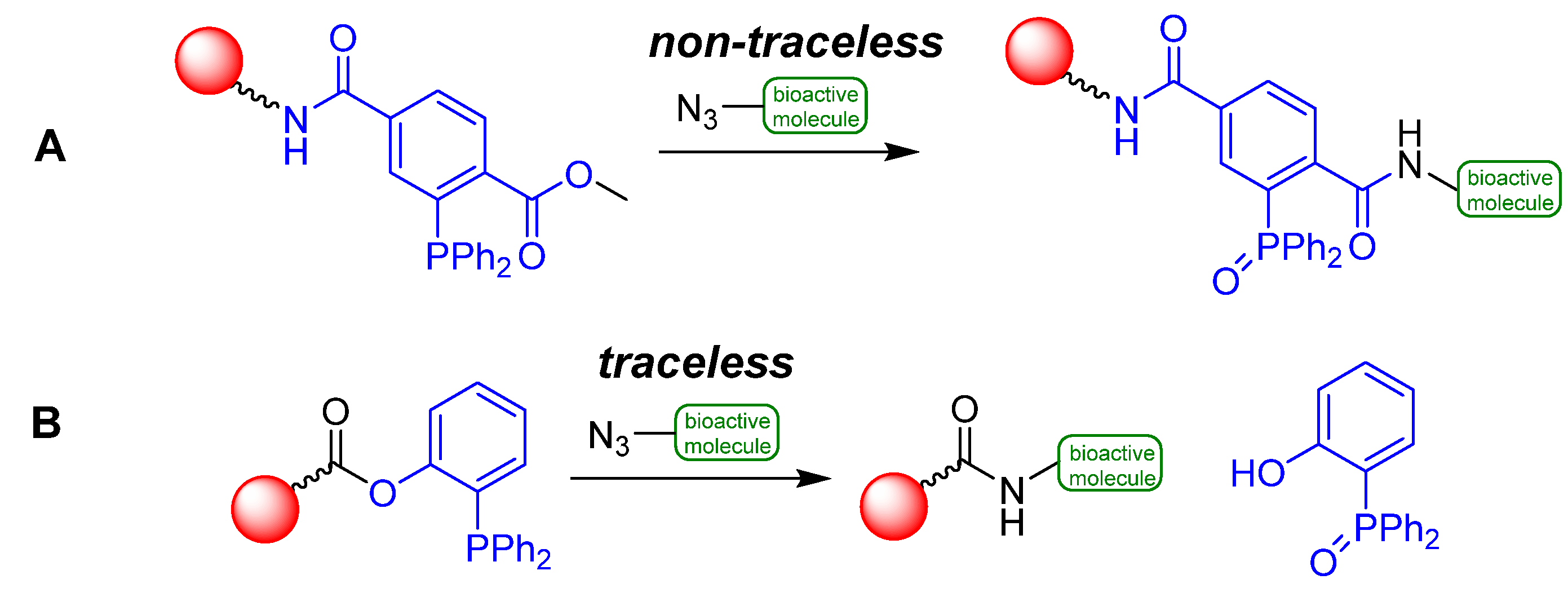

5. Staudinger Ligation

In 1919, Hermann Staudinger and Jules Meyer investigated the reaction of organic azides with phosphane derivatives [

115]. Phosphane imines and elemental nitrogen were obtained from that reaction under absence of water. When water was added, the respective primary amines were yielded. This reaction is known as Staudinger reduction [

116]. Conjugations with the respective phosphane imines are possible to execute using other electrophiles like carbonyl compounds instead of water. Based on these results, ligation reactions were developed which allow a bioorthogonal conjugation between azide functionalized molecules and phosphane species [

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123,

124]. Two versions of this ligation type are known [

125]. The non-traceless variant was introduced by Bertozzi

et al. in the year 2000 [

126]. Modified therephtalate compounds with a diphenylphosphanyl residue serve as fundament of this reaction. These modified phosphanes were reacted with organic azides and led to the desired ligation products after hydrolysis. Notably, the formed ligation product still contains the phosphane species which is oxidized during the reaction (

Scheme 38: path

A).

Scheme 38.

Variants of the Staudinger Ligation.

Scheme 38.

Variants of the Staudinger Ligation.

In the same year, the traceless variant of the Staudinger Ligation was independently and simultaneously developed by Raines and co-workers [

127] and the group of Bertozzi [

128]. In this case, organic azides were used as starting material as well. In contrast to the non-traceless ligation, phosphanes were introduced which are functionalized in the

ortho-position relative to the phosphorus on one of the aromatic rings. The phosphane oxide residue which is formed during the reaction is excluded and both reaction partners are connected exclusively via a native amide (peptide) bond (

Scheme 38: path

B). Therefore, this reaction type is often adapted in peptide syntheses [

129,

130]. Both ligations proceed in a wide pH range using organic or aqueous solvents.

The non-traceless Staudinger Ligation is seldom used for radiolabeling purposes with fluorine-18. To date, only one application is known. In 2006, the preparation of a fluorine-18 containing phosphane and the ligation to an azide containing carbohydrate was described [

131] as shown in

Scheme 39. In this case, the labeled glucose derivative served as an alternative for [

18F]FDG and the application for the pretarget PET imaging of cancer was designated.

Scheme 39.

Building blocks for the radiolabeling using the non-traceless Staudinger Ligation.

Scheme 39.

Building blocks for the radiolabeling using the non-traceless Staudinger Ligation.

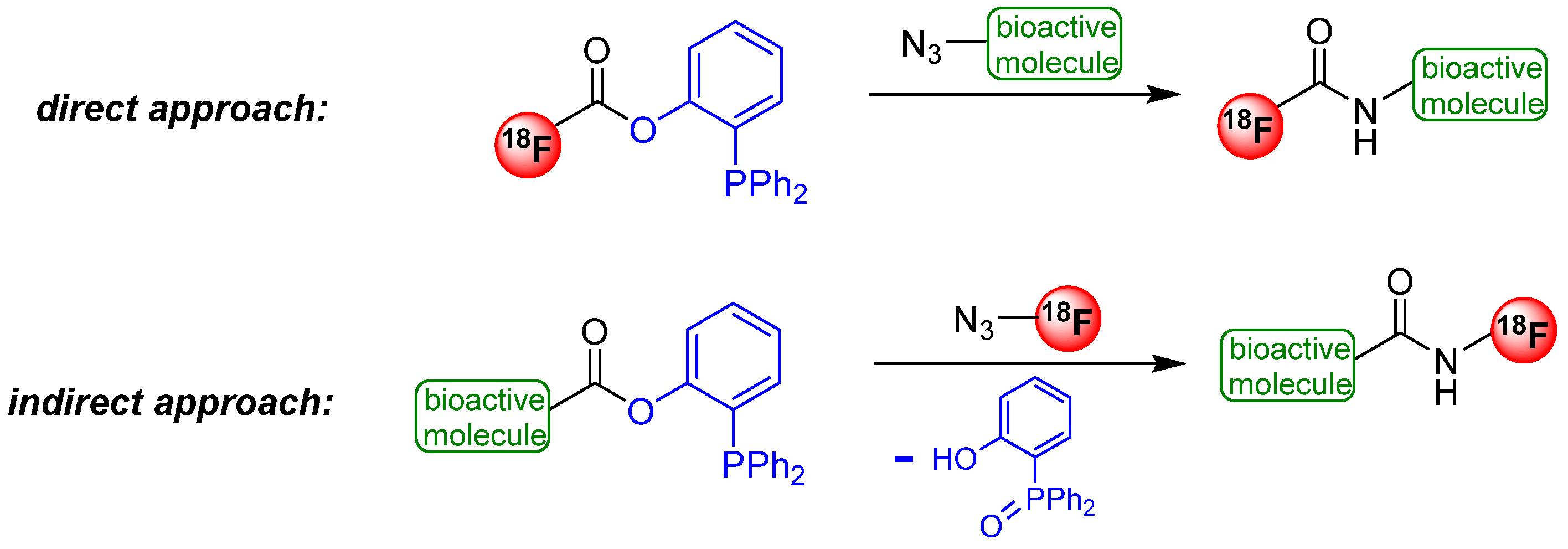

In contrast to the non-traceless variant, several examples for the traceless Staudinger Ligation were published in the past. In general, two strategies were pointed out depending on the incorporation of fluorine-18 into the starting material. In the first case, phosphanes were evaluated containing the fluorine-18. For this purpose, biologically active molecules were modified with azide (direct approach). In the second case, the phosphane residue was introduced into the biologically active molecule and the fluorine-18 was connected to an azide functionalized molecule (indirect approach). Both ways are introduced in

Scheme 40.

Scheme 40.

Direct and indirect approach of the traceless Staudinger Ligation.

Scheme 40.

Direct and indirect approach of the traceless Staudinger Ligation.

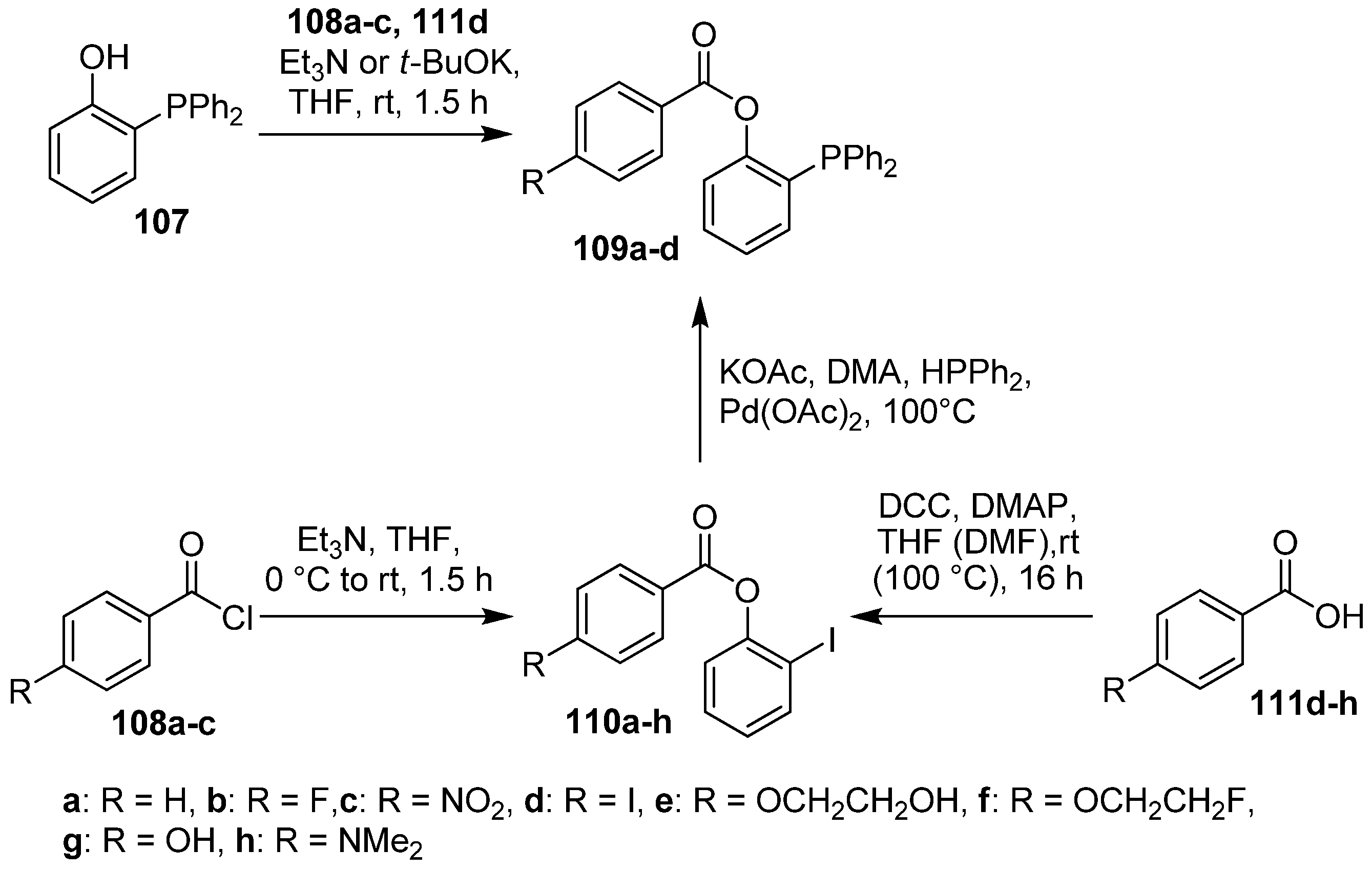

The direct approach was intensively investigated by Mamat and co-workers starting in 2009 [

132]. For that purpose, phosphanes with various benzoate residues functionalized in the

para-position were prepared [

133]. Hence, two reaction paths were developed. First, the conventional esterification of phosphanol

107 with benzoyl chlorides

108a–

c in the presence of a base or via Steglich esterification (for

111d) delivered the substituted phosphanes

109a–

d (yield: 38−92%). However, application of these reaction conditions sometimes led to low yields of the desired phosphanes or the formation of by-products. Due to this fact, functionalized 4-iodophenyl derivatives

110a-h were applied as an alternative. Phosphanes

109a–h were obtained in 58−89% yield from the Pd-catalyzed cross coupling of

110a–h with diphenylphosphane (HPPh

2); the findings are summarized in

Scheme 41. This approach should serve as a possibility for the introduction of the 4-[

18F]fluorobenzoate moiety (alternatively for [

18F]SFB), but without success.

Scheme 41.

Preparation of various phosphane building blocks.

Scheme 41.

Preparation of various phosphane building blocks.

Scheme 42.

Radiofluorinations with [18F]114 using the traceless Staudinger Ligation.

Scheme 42.

Radiofluorinations with [18F]114 using the traceless Staudinger Ligation.

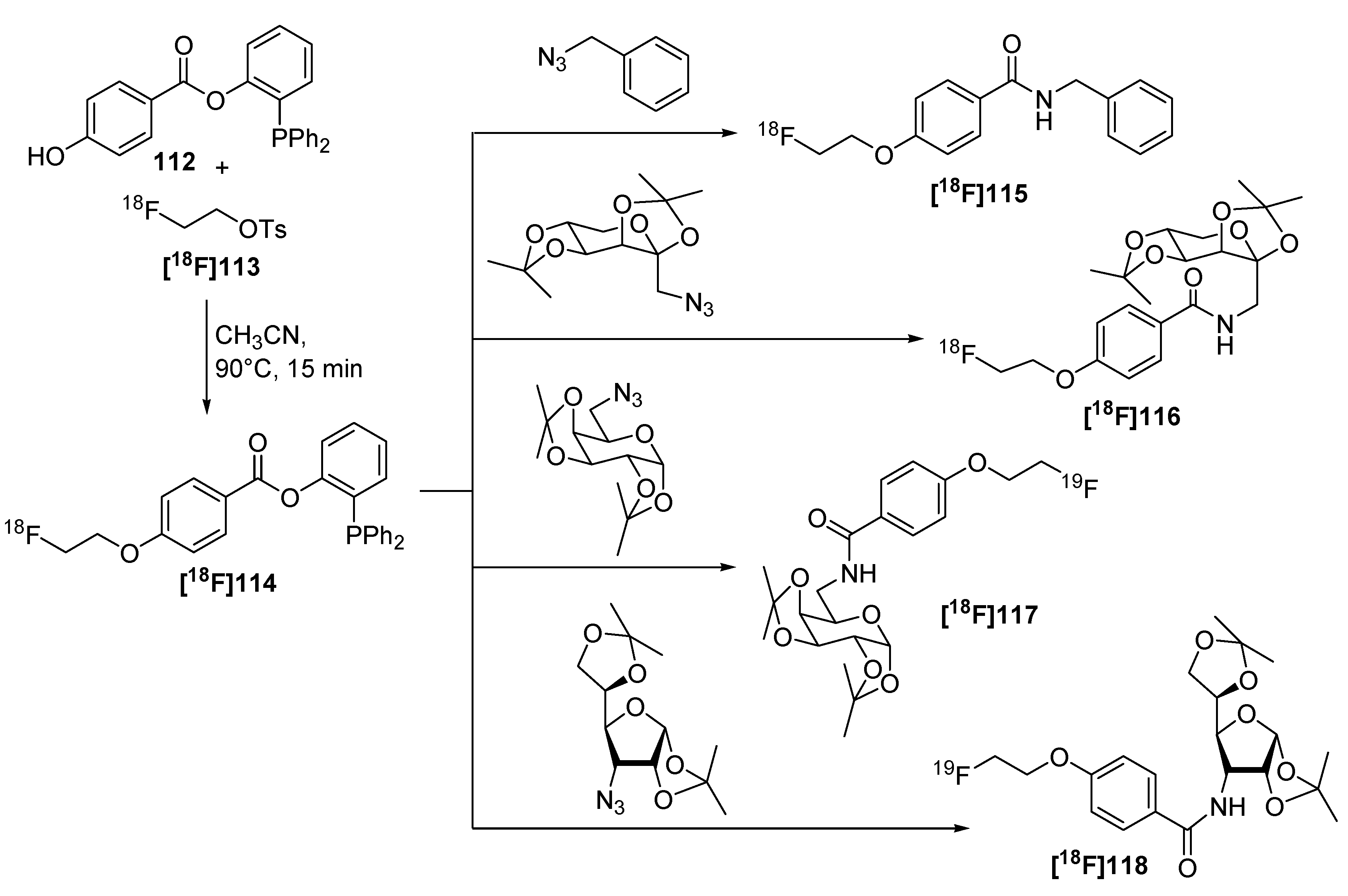

Later, a different labeling strategy was evaluated [

134] based on 2-(diphenylphosphano)phenyl 4-hydroxybenzoate (

112) which was reacted with 2-[

18F]fluoroethyl tosylate (

[18F]113) to yield the desired phosphane

[18F]114. In the second step, the respective azide was added to yield the desired radiotracer. This reaction was carried out as a three-step/one-pot procedure starting from ethylene ditosylate as seen in

Scheme 42. The phosphane precursor was added in a one-pot two-step procedure after the generation of

[18F]113 to yield the labeled phosphane species. Subsequently, the respective azido compound was added for labeling purposes within the Staudinger Ligation to yield

[18F]115-[18F]118 (17−21% RCY, d.c.).

Notably, a two-step sequence was required for the preparation of the

18F-containing phosphane which generally lowers the RCY as well as the A

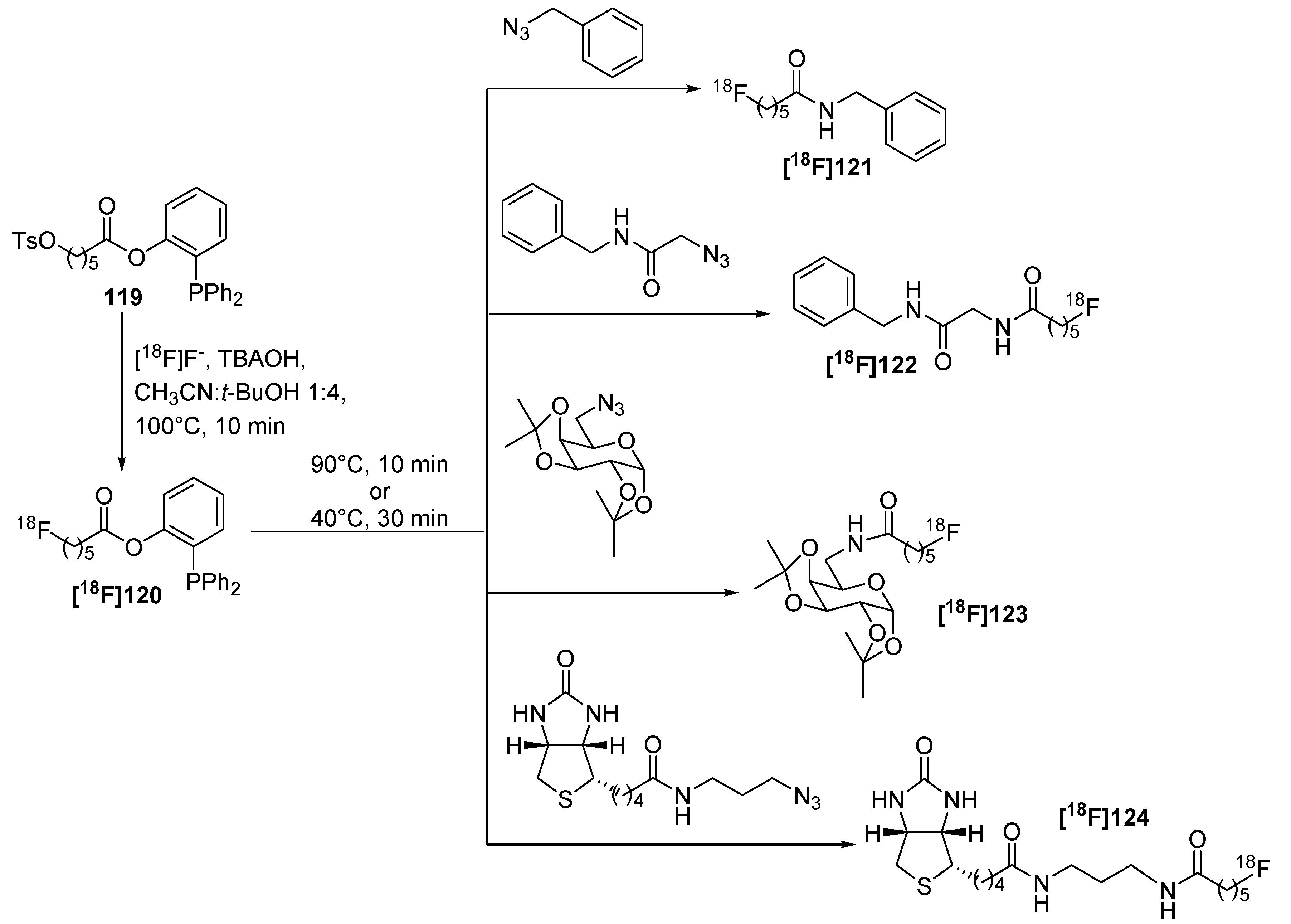

S of the final tracers. For this purpose, a one-step approach for the preparation of fluorine-18 containing phosphane building blocks like

[18F]120 (RCY = 65%, d.c.) was developed based on aliphatic phosphanyl esters [

135,

136]. A chain length of five carbon atoms was chosen for precursor

119. Different bases as well as fluorination agents and solvents were evaluated for optimization. The best results were obtained using [

18F]fluoride in the presence of TBAOH which was used as base in a mixture of acetonitrile/

t-BuOH (v/v = 1:4) [

25] for 10 min at 100 °C using 21 mg of precursor

119. Several model compounds

[18F]118-[18F]121 including a carbohydrate moiety and (+)-biotin were first azide functionalized and subsequently labeled using the traceless Staudinger Ligation (

Scheme 43) with RCYs from 12 to 31% (d.c.).

Scheme 43.

One pot preparation of phosphane building block [18F]120 and subsequent radiolabeling of azide functionalized molecules using the traceless Staudinger Ligation.

Scheme 43.

One pot preparation of phosphane building block [18F]120 and subsequent radiolabeling of azide functionalized molecules using the traceless Staudinger Ligation.

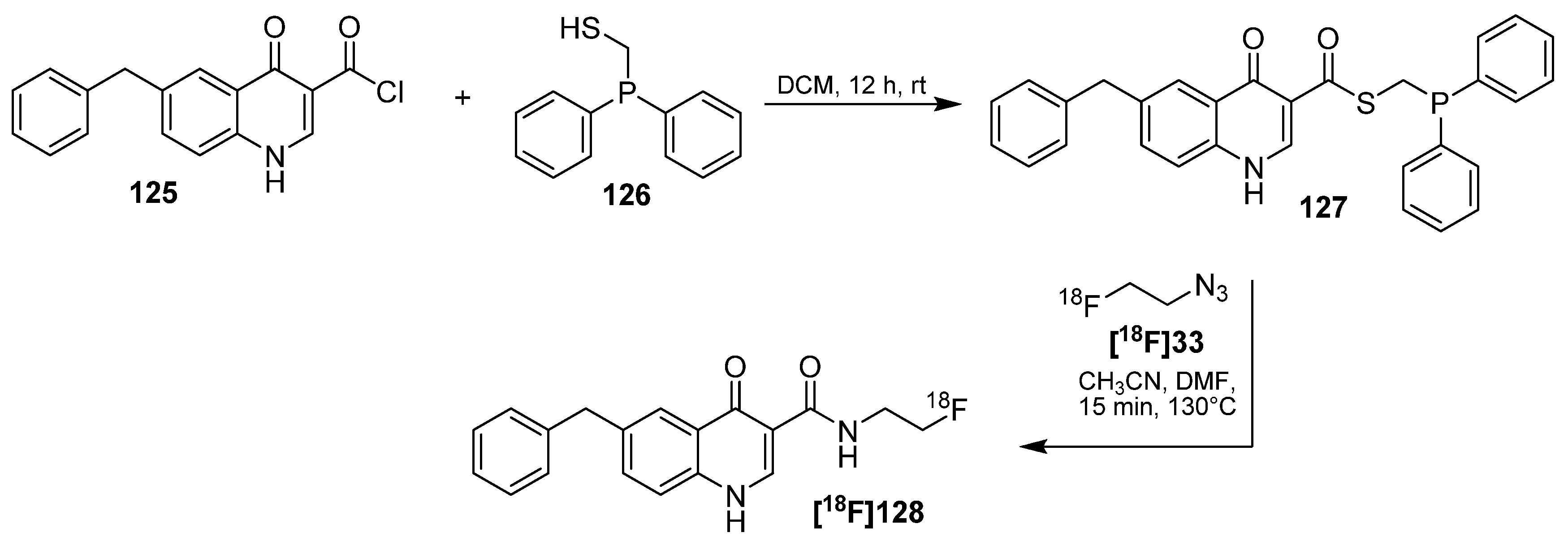

In 2010, Gaeta

et al. reported the preparation and radiolabeling of GABA

A receptor binding 4-quinolones with K

i from 0.7 to 3.7 nM [

137]. For this purpose, the bioactive site of molecule

125 was modified and (diphenylphosphino)methanethiol moiety

126 was introduced (indirect approach). For the radiolabeling, 2-[

18F]fluoroethyl azide (

[18F]33) was applied as the labeling building block. The following Staudinger Ligation was accomplished in a mixture of acetonitrile and DMF for 15 min at 130 °C and

[18F]128 was obtained after purification using preparative HPLC with 75% RCY (30–50 MBq, not d.c.) and a A

S = 0.9 GBq/μmol (radiochemical purity > 95%); see

Scheme 44. Biological data showed that only a modest fraction of the compound crossed the blood–brain barrier, with peak uptake no greater than 0.12% of the injected dose (0.11% ID/g).

Ex vivo autoradiographic analysis of prefrontal cortex, striatum and thalamus slices indicated significant differential binding of

[18F]128 consistent with the distribution of GABA

A receptors.

Scheme 44.

Preparation and radiolabeling of quinolone-based precursor 127.

Scheme 44.

Preparation and radiolabeling of quinolone-based precursor 127.

A second work was published in 2011 by the group of Gouverneur

et al. [

138] using a similar strategy with 2-[

18F]fluoroethyl azide (

[18F]33) as labeling agent and phosphane functionalized biologically active molecules

129–133 (indirect approach). In this case, various amino acid derivatives were labeled as shown in

Table 2 [labeling conditions: (A) THF/H

2O (4/1), 120 °C, 15 min; (B) DMF/H

2O (6/1), 120 °C, 15 min].

Table 2.

Scope of the labeling reaction under Staudinger conditions.

The purification step of this labeling reaction was improved using fluorous solid phase extraction (FSPE). For this purpose, derivative

132 was prepared with a fluorous tag [

139] (C

4F

9 chain on the aromatic ring of the phosphane) attached onto the phosphino fragment. Adversely, this compound was faster oxidized to the corresponding phosphine than the non fluorous counterpart. Thus, the purification step of

132 was done under absence of air. The following Staudinger Ligation with 2-fluoroethyl azide using standard conditions led to the formation of

136 in 27% yield after purification of the reaction mixture using FSPE [

140]. The decrease in isolated yield could be attributed to the propensity of the phosphane precursor

132 towards oxidation. The radiofluorination was performed in acetonitrile using [

18F]

–/K

+/K 222 followed by FSPE to separate 2-[

18F]fluoroethyl azide (

[18F]33) (A

S~10 GBq/mmol) from the excess fluorous precursor

132, no distillation was necessary. Pleasingly, the labelling of both the non-fluorous and fluorous alanine precursor

131 and

132 with 2-[

18F]fluoroethyl azide (

[18F]33) in DMF–H

2O (6 : 1) at 120°C for 15 min afforded

[18F]136 in an excellent RCY of >95% (entries 3–4,

Table 2). The purification using FSPE for the labeling of

132 led to an improvement, but HPLC was still necessary to obtain an analytically pure sample due to the breakthrough of fluorous material into the fluorophobic eluted fraction.

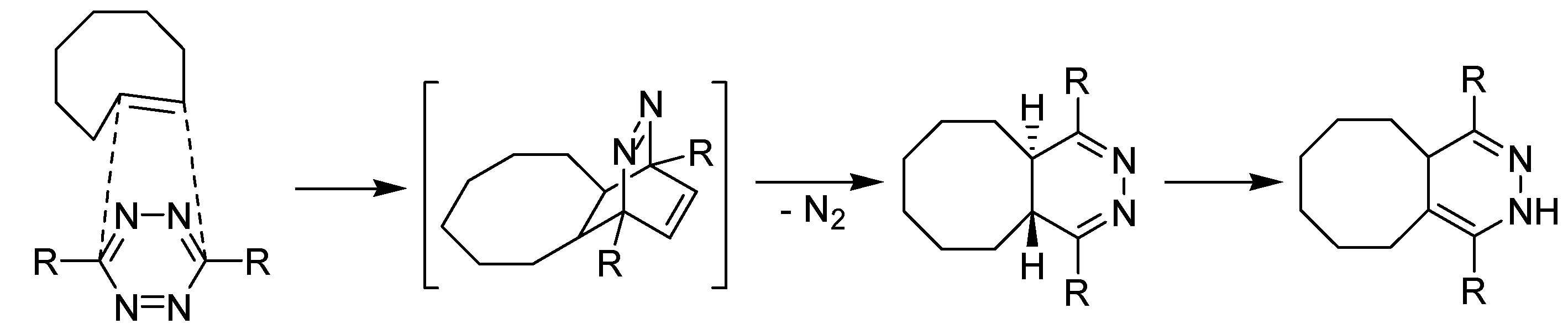

6. Tetrazine-Click

Investigated first by the group of Fox and co-workers, the tetrazine ligation is a fast bioconjugation method based on inverse-electron-demand Diels−Alder reactions [

141], a proposed mechanism is pointed out in

Scheme 45. The main advantage of this kind of reaction involves the unusually fast reaction rates (

k2 = 2,000 M

−1·s

−1, solvent MeOH/water: 9/1) without need for catalysis. A further advantage is the non-reversibility due to the loss of elemental nitrogen, in contrast to most other Diels-Alder reactions. These reactions tolerate a broad range of functionality and proceed with high yield in organic solvents, water, buffer, cell media, or lysate. This fast reactivity enables protein modification at low concentration. The resulting cycloocta[

d]pyridazines were obtained as conjugation products from the cycloaddition of

s-tetrazine and

trans-cyclooctene derivatives. Mechanistically, the tetrazine ligation proceeds in two steps. An inverse-demand Diels-Alder reaction occurs followed by a retro-Diels-Alder reaction to eliminate nitrogen gas.

Scheme 45.

Proposed reaction mechanism of the tetrazine-click reaction.

Scheme 45.

Proposed reaction mechanism of the tetrazine-click reaction.

Based on computational work by Bach,

E-cyclooctene has a highly twisted double bond resulting in a strain energy of 17.9 kcal/mol compared to

Z-cyclooctenes or cyclooctane [

142]. Based on these results, highly strained

trans-derivatives were used as reactive dienophiles. Further, 3,6-diaryl-s-tetrazines serve as dienes which have been substituted in order to resist immediate reaction with water. The fact that the reaction is not only tolerant of water is also important especially for fast radiolabeling reactions. It has also been found that the rate increases in aqueous media. In addition, norbornenes were introduced as dienophiles at second order rates on the order of 1 M

−1·s

−1 in aqueous media. The labeling of live cells [

143,

144,

145] or polymer coupling [

146,

147] were prominent examples of an application of this kind of conjugation reaction. Alongside, an elegant work concerning the radiolabeling of peptides using

111In-DOTA were published by Robillard [

148] and a modular strategy for the preparation of

64Cu and

89Zr radiometalated antibodies was previously published [

149].

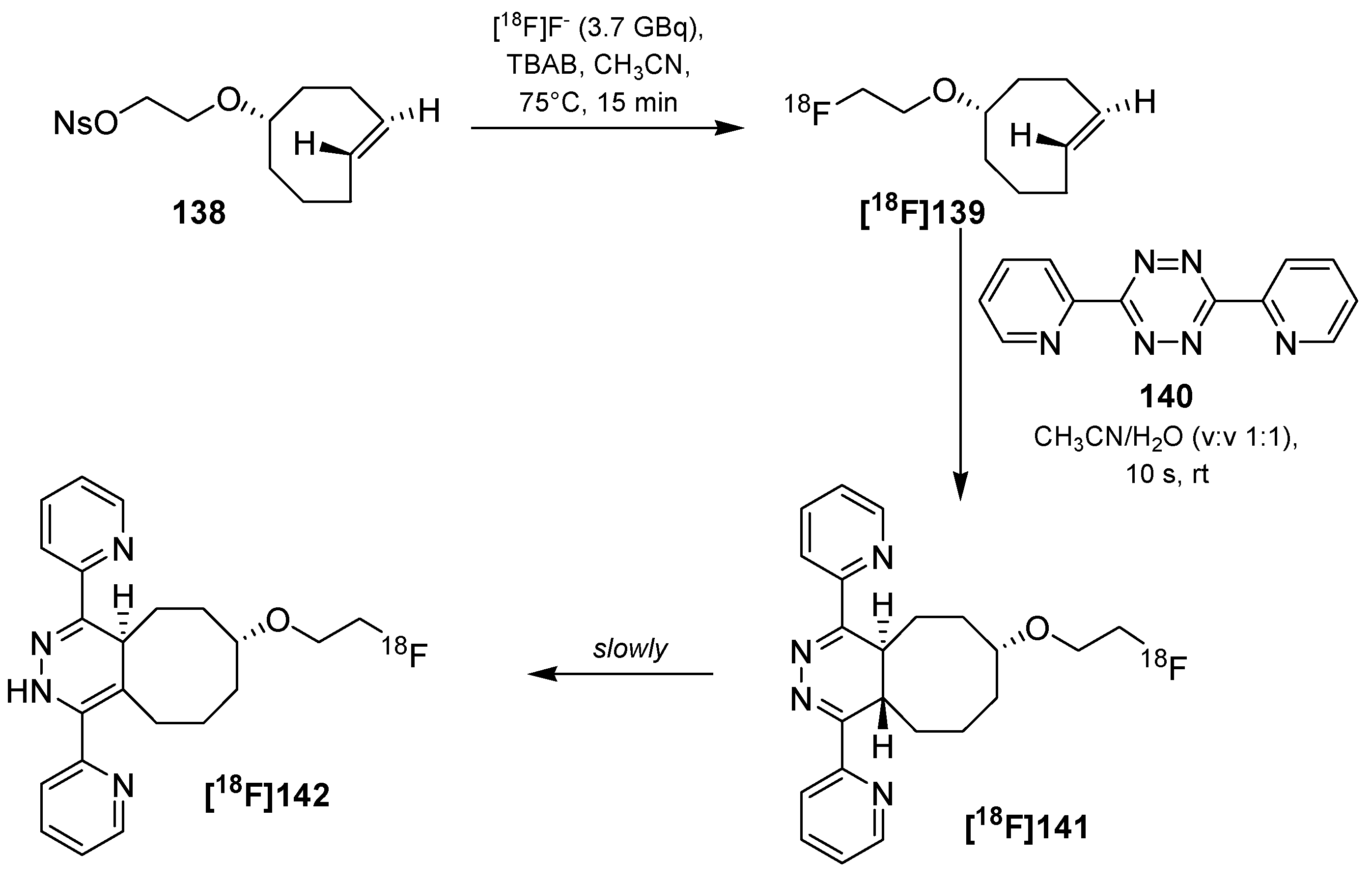

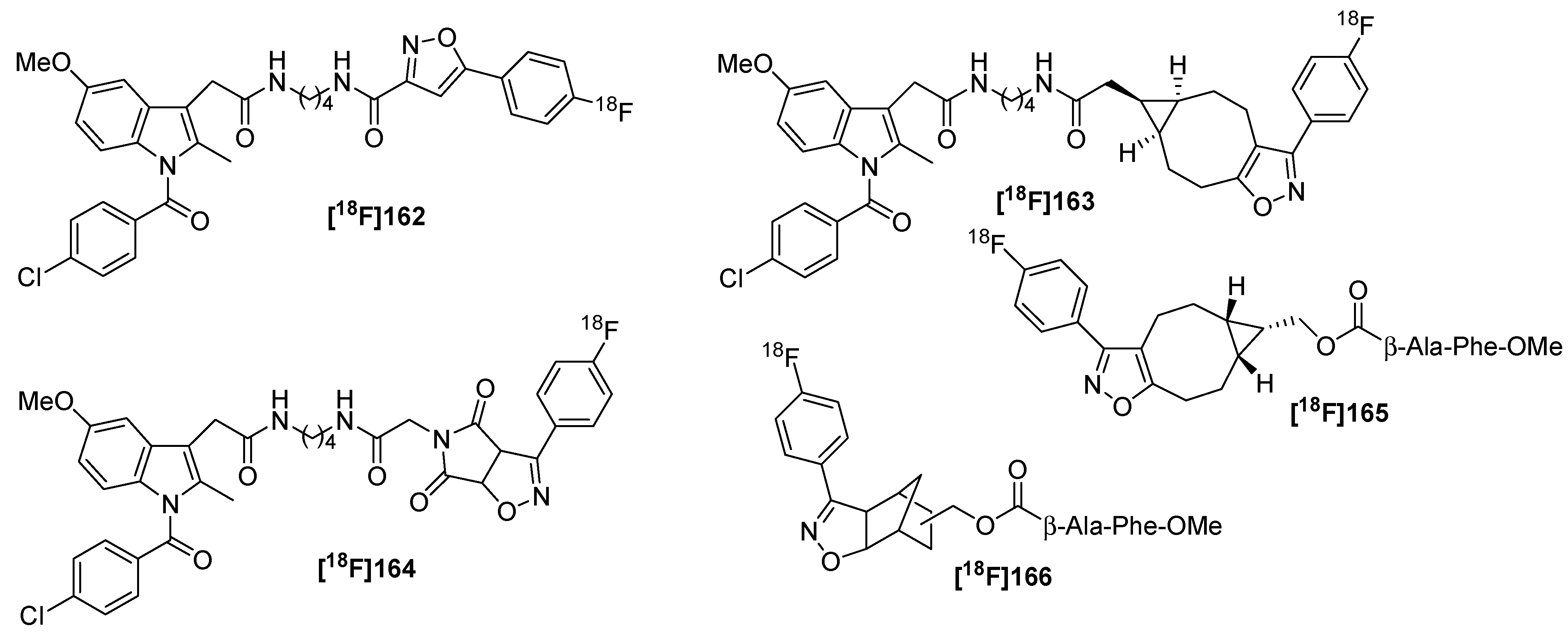

One of the first studies to apply the tetrazine-click reaction for radiofluorinations was achieved in the year 2010 by the group of Fox and co-workers (

Scheme 46) [

150]. First, they tried to label tetrazine derivatives with fluorine-18 for a conjugation with the

trans-cyclooctene containing bioactive molecule. The instability of the tetrazines (RCY~1%) prompted the group to change the functionalities. Thus, [

18F]TCO

[18F]139 as fluorine-18-containing cyclooctene derivative was prepared (RCY 71%) from the respective nosylate precursor

138 in a reaction time of 15 min.

[18F]139 was then used for the conjugation with the tetrazine containing sample molecule

140 within 10 s of mixing at ambient temperature with a RCY > 98%.

Scheme 46.

First example of the tetrazine-click reaction.

Scheme 46.

First example of the tetrazine-click reaction.

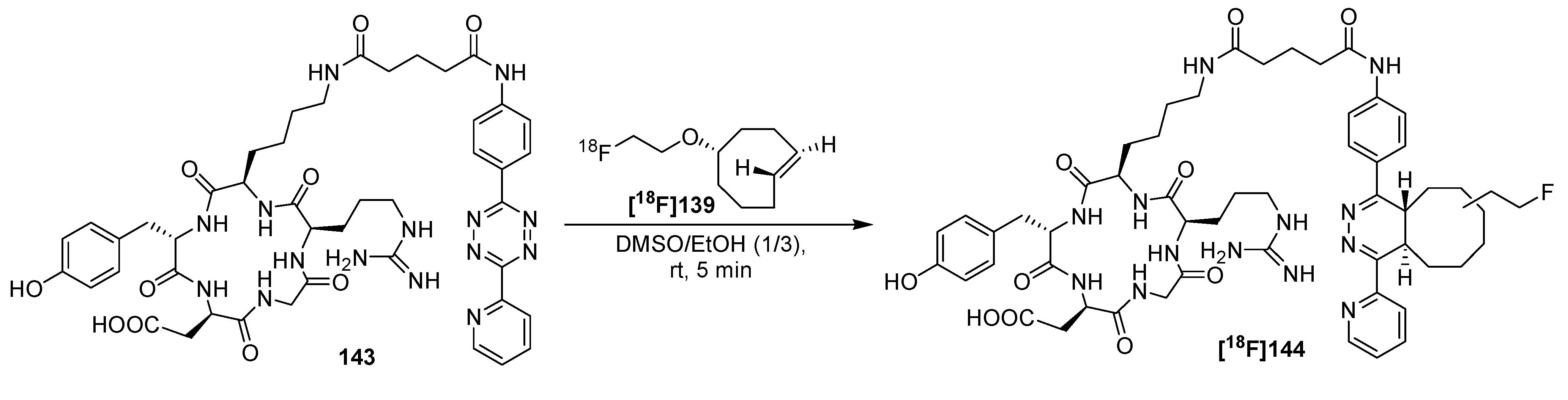

Scheme 47.

Labeling of tetrazine-modified RGD peptide 143 using [18F]139.

Scheme 47.

Labeling of tetrazine-modified RGD peptide 143 using [18F]139.

Based on these results, a cyclic RGD peptide was developed as an α

vβ

3 targeted PET tracer [

151]. Tetrazine-RGD conjugate

143 was prepared as the precursor by treatment of c(RGDyK) with a NHS-ester. Radiolabeling was done with [

18F]TCO

[18F]139 at ambient temperature for 5 min in a mixture of DMSO and EtOH (1/3). [

18F]RGD-tracer

[18F]144 was obtained in >95% RCY (based on

[18F]139), see

Scheme 47. microPET analyses using a U87MG xenograft model showed a tumor uptake of 4.4%ID/g after 1 h. Blocking experiments revealed a specific binding to integrin α

vβ

3.

Next, the tetrazine residue was functionalized with a maleimide moiety for the radiolabeling of other cyclic RGD peptides without lysine residue [

152]. Two strategies were evaluated for that purpose. In the first, the tetrazine-maleimide linker was conjugated with a cysteine-modified RGD peptide and finally labeled with [

18F]TCO

[18F]139. The labeled peptide was obtained in > 95% RCP with a A

S of approx. 111 to 222 GBq/µmol. To compare the efficiency of this ligation type, [

18F]TCO

[18F]139 was directly reacted with the maleimide functionalized tetrazine. The original RGD peptide was then treated with this conjugate; however, this reaction proceeded within 20 min whereas the first labeling way took only 5 min. In addition, a higher peptide concentration was mandatory for the second way. MicroPET studies of U87MG tumor-bearing mice showed an uptake of

18F-RGD

[18F]144 of approx. 2% ID/g in the tumor which is comparable with the previous findings of this group.

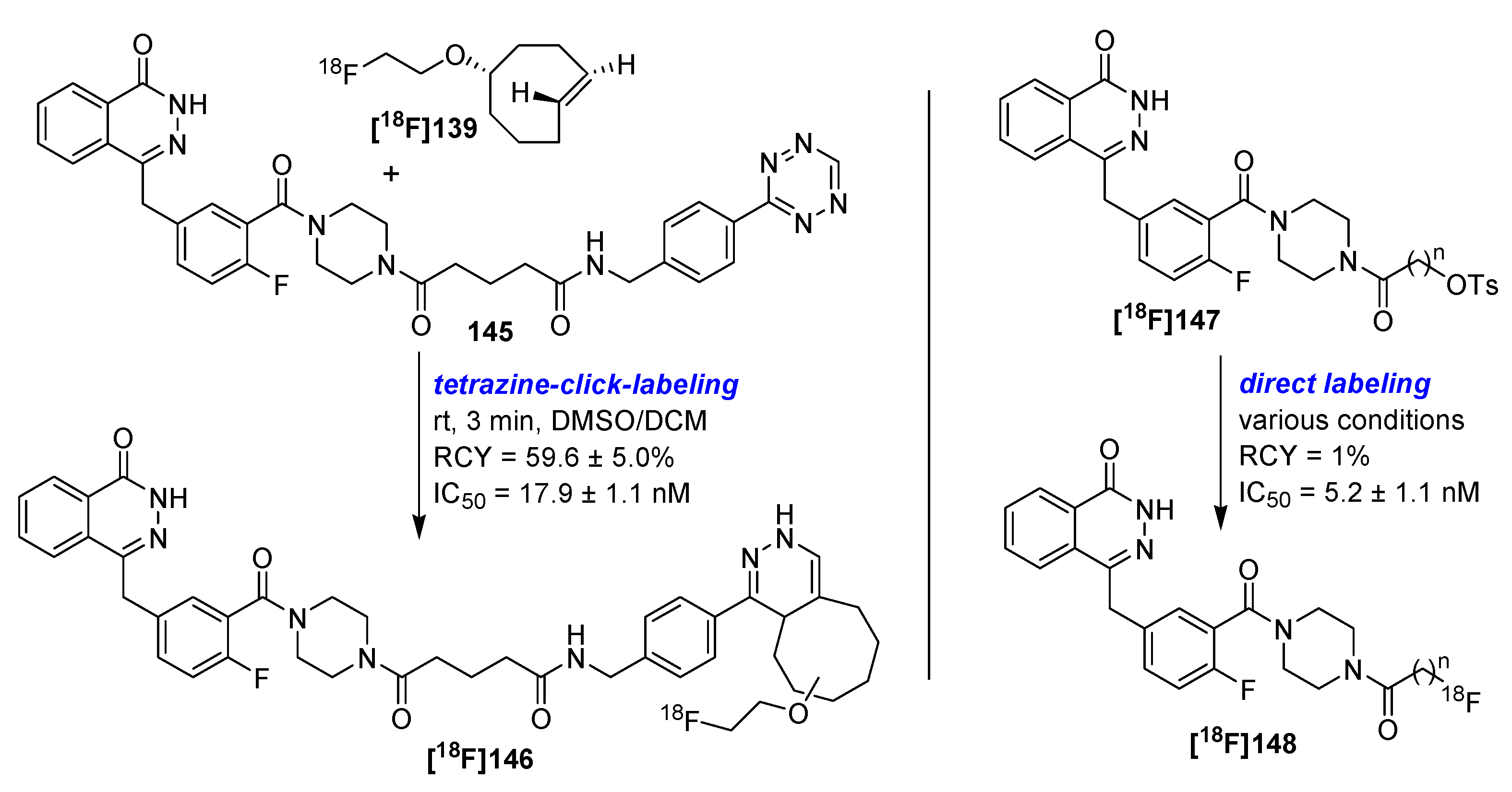

Next, based on previous work [

153], the syntheses and

in vivo imaging of two

18F-labeled PARP1 inhibitors were presented by Reiner

et al. in 2011 [

154,

155]. In the first publication, they compared the conventional direct nucleophilic introduction of [

18F]fluoride with the click-labeling using [

18F]TCO

[18F]139. For this purpose, a fully automated synthesis (41 min) of [

18F]TCO

[18F]139 was developed which yielded the building block in 44.7 ± 7.8% RCY (d.c., > 93% RCP, conditions: [

18F]fluoride,

n-Bu

4NHCO

3, 90 °C). Subsequent radiofluorination with tetrazine

145 was accomplished in a DMSO/DCM solution for 3 min.

[18F]146 was provided in 59.6 ± 5.0% RCY (d.c., n = 3, RCP > 96%) after HPLC purification. In contrast, the direct radiofluorination of

147 delivered

[18F]148 in only 1% RCY. Next, the target affinity of both tracers was studied. Thus, a colorimetric assay was employed to measure PARP1 activity with the result that

[18F]148 had an IC

50 of 5.2 ± 1.1 nM whereas the clicked product

[18F]146 had an IC

50 of 17.9 ± 1.1 nM. This results show impressively the dependence of the introduced moiety on the affinity of a molecule (

Scheme 48).

Scheme 48.

Comparison between conventional and tetrazine-click labeling.

Scheme 48.

Comparison between conventional and tetrazine-click labeling.

An improvement was done regarding the purification of the resulting radiotracer

[18F]146 from the precursor

145 [

156]. A magnetic TCO resin was developed and used for a subsequent incubation after the radiolabeling step. The following separation was done using a magnet. An overview was pointed out in

Scheme 49. This method was applied to successfully remove the excess of precursor

145 and to avoid lengthy HPLC purifications. After separation of the magnetic resin, the radiotracer

[18F]146 was obtained in 92 ± 0.4% RCY (d.c.).

Scheme 49.