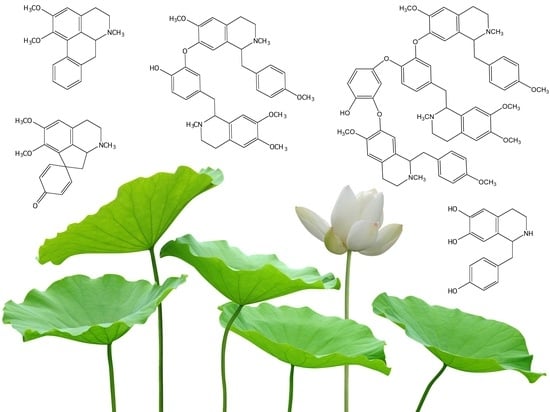

Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids Biosynthesis in Sacred Lotus

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Occurrence of BIAs in Sacred Lotus

2.1. 1-Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids

2.2. Aporphines

2.3. Bisbenzylisoquinolines

3. Stereochemistry of BIAs Biosynthesis in Nelumbo nucifera

4. BIA biosynthetic Genes and Enzymes in the Sacred Lotus

4.1. Norcoclaurine Synthase

4.2. Methyltransferases

4.3. Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenases

4.4. Other Enzymes

4.5. Functional Characterization

4.6. Regulation and Localization of BIA Biosynthesis in Sacred Lotus

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ming, R.; VanBuren, R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, M.; Han, Y.; Li, L.T.; Zhang, Q.; Kim, M.J.; Schatz, M.C.; Campbell, M.; et al. Genome of the long-living sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.). Genome Biol. 2013, 14, R41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Sun, F.; Shi, C.; Liu, X.; Peng, J.; Chen, W.; Huang, X.; Cheng, S.; et al. The sacred lotus genome provides insights into the evolution of flowering plants. Plant J. 2013, 76, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xue, J.; Dong, W.; Cheng, T.; Zhou, S. Nelumbonaceae: Systematic position and species diversification revealed by the complete chloroplast genome. J. Syst. Evol. 2012, 50, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.R.; Guautam, L.N.S.; Adhikari, D.; Karki, R. A comprehensive review on chemical profiling of Nelumbo nucifera: Potential for drug development. Phytother Res. 2017, 31, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ushimaru, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Amano, T.; Katayama, M.; Tanaka, S.; Tsuji, H. Chloroplasts in seeds and dark-grown seedlings of lotus. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, N.M.; Miller, R.E.; Watling, J.R.; Robinson, S.A. Synchronicity of thermogenic activity, alternative pathway respiratory flux, AOX protein content, and carbohydrates in receptacle tissues of sacred lotus during floral development. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koch, K.; Bhushan, B.; Jung, Y.C.; Barthlott, W. Fabrication of artificial Lotus leaves and significance of hierarchical structure for superhydrophobicity and low adhesion. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen-Miller, J.; Mudgett, M.B.; Schopf, J.W.; Clarke, S.; Berger, R. Exceptional seed longevity and robust growth: Ancient sacred lotus from China. Am. J. Bot. 1995, 82, 1367–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen-Miller, J.; Aung, L.H.; Turek, J.; Schopf, J.W.; Tholandi, M.; Yang, M.; Czaja, A. Centuries-old viable fruit of sacred lotus Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn var China Antique. Trop. Plant Biol. 2013, 6, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Mukherjee, D.; Maji, A.K.; Rai, S.; Heinrich, M. The sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera)—Phytochemical and therapeutic profile. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2009, 61, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Yi, D.D.; Guo, J.L.; Xiang, Z.X.; Deng, L.F.; He, L. Nuciferine, extracted from Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., inhibits tumor-promoting effect of nicotine involving Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in non-small cell lung cancer. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 165, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.J.; Lee, S.K.; Park, K.K.; Son, S.H.; Kim, K.R.; Chung, W.Y. Liensinine and nuciferine, bioactive components of Nelumbo nucifera, inhibit the growth of breast cancer cells and breast cancer-associated bone loss. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 1583185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Q.; Li, R.; Li, H.Y.; Cao, Y.B.; Bai, M.; Fan, X.J.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, S. Identification of the anti-tumor activity and mechanisms of nuciferine through a network pharmacology approach. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2016, 37, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ma, C.; Li, G.; He, Y.; Xu, B.; Mi, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z. Pronuciferine and nuciferine inhibit lipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by activating the AMPK signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2015, 136, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morikawa, T.; Kitagawa, N.; Tanabe, G.; Ninomiya, K.; Okugawa, S.; Motai, C.; Kamei, I.; Yoshikawa, M.; Lee, I.-J.; Muraoka, O. Quantitative determination of alkaloids in lotus flower (flower buds of Nelumbo nucifera) and their melanogenesis inhibitory activity. Molecules 2016, 21, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, S.; Nakashima, S.; Tanabe, G.; Oda, Y.; Yokota, N.; Fujimoto, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Sukama, R.; Ohta, T.; Ogawa, K.; et al. Alkaloid constitutens from flower buds and leaves of sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera, Nymphaeaceae) with melanogenesis inhibitory activity in B16 melanoma cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.M.; Kao, C.L.; Wu, H.M.; Li, W.J.; Huang, C.T.; Li, H.T.; Chen, C.Y. Antioxidant and anticancer aporphine alkaloids from the leaves of Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. cv. Rosa-plena. Molecules 2014, 19, 17829–17838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnihotri, V.K.; ElSohly, H.N.; Khan, S.I.; Jacob, M.R.; Joshi, V.C.; Smillie, T.; Khan, I.A.; Walker, L.A. Constituents of Nelumbo nucifera leaves and their antimalarial and antifungal activity. Phytochem. Lett. 2008, 1, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.Q. Cardiovascular pharmacological effects of bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloid derivatives. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2002, 23, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Poornima, P.; Weng, C.F.; Padma, V.V. Neferine, an alkaloid from lotus seed embryo, inhibits human lung cancer cell growth by MAPK activation and cell cycle arrest. Biofactors 2014, 40, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.S.; Kim, H.M.; Yadunandam, A.K.; Kim, N.H.; Jung, H.A.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Kim, G.D. Neferine isolated from Nelumbo nucifera enhances anti-cancer activities in Hep3B cells: Molecular mechanisms of cell cycle arrest, ER stress induced apoptosis and anti-angiogenic response. Phytomedicine 2013, 20, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Lu, S.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Tian, X.; Wei, J.J.; Shao, C.; Liu, Z. Neferine induces autophagy of human ovarian cancer cells via p38 MAPK/ JNK activation. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 8721–8729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, T.; Li, B.; Liu, T.; Wang, R.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Gong, Y.; Shao, C. Isoliensinine induces apoptosis in triple-negative human breast cancer cells through ROS generation and p38 MAPK/JNK activation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nishimura, K.; Horii, S.; Tanahashi, T.; Sugimoto, Y.; Yamada, J. Synthesis and pharmacological activity of alkaloids from embryo of lotus, Nelumbo nucifera. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 61, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, J.; Facchini, P.J. Alkaloid biosynthesis: Metabolism and trafficking. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 735–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadler, R.; Kutchan, T.M.; Zenk, M.H. (S)-Norcoclaurine is the central intermediate in benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 1083–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagel, J.M.; Facchini, P.J. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloid metabolism: A century of discovery and a brave new word. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 647–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagel, J.M.; Mandal, R.; Han, B.; Han, J.; Dinsmore, D.R.; Borchers, C.H.; Wishart, D.S.; Facchini, P.J. Metabolome analysis of 20 taxonomically related benzylisoquinoline alkaloid-producing plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagel, J.M.; Morris, J.S.; Lee, E.J.; Desgagné-Penix, I.; Bross, C.D.; Chang, L.; Chen, X.; Farrow, S.C.; Zhang, Y.; Soh, J.; et al. Transcriptome analysis of 20 taxonomically related benzylisoquinoline alkaloid-producing plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudoin, G.A.W.; Facchini, P.J. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in opium poppy. Planta 2014, 240, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liscombe, D.K.; MacLeod, B.P.; Loukanina, N.; Nandi, O.I.; Facchini, P.J. Evidence for the monophyletic evolution of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in angiosperms. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2501–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Zhu, L.; Fang, T.; Vimolmangkang, S.; Yang, D.; Ogutu, C.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y. Analysis of isoquinoline alkaloid composition and wound-induced variation in Nelumbo using HPLC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Fang, J.; Li, S. Determination of lotus leaf alkaloids by solid phase extraction combined with high performance liquid chromatography with diode array and tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Lett. 2013, 46, 2846–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimolmangkang, S.; Deng, X.; Owiti, A.; Meelaph, T.; Ogutu, C.; Han, Y. Evolutionary origin of the NCSI gene subfamily encoding norcoclaurine synthase is associated with the biosynthesis of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids in plants. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, M.; Jiang, M.; Ying, X.; Cui, Q.; Han, Y.; Hou, Y.; Gao, J.; Bai, G.; Luo, G. Identification and comparison of anti-inflammatory ingredients from different organs of Lotus Nelumbo by UPLC/Q-TOF and PCA coupled with a NF-κB reporter gene assay. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshiyama, H.; Ohkuma, H.; Kawaguchi, H.; Hsü, H.Y.; Chen, Y.P. Isolation of 1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-6,7-dihydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (demethylcoclaurine), an active alkaloid from Nelumbo nucifera. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1970, 18, 2564–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwada, Y.; Aoshima, A.; Ikeshiro, Y.; Chen, Y.-P.; Furukawa, H.; Itoigawa, M.; Fujioka, T.; Mishashi, K.; Cosentino, L.M.; Morris-Natschke, S.L.; et al. Anti-HIV benzylisoquinoline alkaloids and flavonoids from the leaves of Nelumbo nucifera, and structure-activity correlations with related alkaloids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Yang, R.; Guan, Z.; Chen, A.; Li, W. Ultra-performance LC separation and quadrupole time-of-flight MS identification of major alkaloids in plumula nelumbinis. Phytochem. Anal. 2014, 25, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.; Lee, Y.I.; Jin, D. Determination of R-(+)-higenamine enantiomer in Nelumbo nucifera by high-performance liquid chromatography with a fluorescent chiral tagging reagent. Microchem. J. 2010, 96, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.C.; Nguyen, T.D.; Tran, H.; Stuppner, H.; Ganzera, M. Analysis of alkaloids in lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.) leaves by non-aqueous capillary electrophoresis using ultraviolet and mass spectrometric detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1302, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunitomo, J.; Yoshikawa, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Inmori, Y.; Isor, K. Alkaloids from Nelumbo nucifera. Phytochemistry 1973, 12, 699–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ka, S.M.; Kuo, Y.C.; Ho, P.J.; Tsai, P.Y.; Hsu, Y.J.; Tsai, W.J.; Lin, Y.L.; Shen, C.C.; Chen, A. (S)-armepavine from Chinese medicine improves experimental autoimmune crescentic glomerulonephritis. Rheumatology 2010, 49, 1840–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, X.; Qi, J.; Yu, B. Simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analysis of flavonoids and alkaloids from the leaves of Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. using high-performance liquid chromatography with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2016, 39, 2499–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grienke, U.; Mair, C.E.; Saxena, P.; Baburin, I.; Scheel, O.; Ganzera, M.; Schuster, D.; Hering, S.; Rollinger, J.M. Human ether-à-go-go related gene (hERG) channel blocking aporphine alkaloids from lotus leaves and their quantitative analysis in dietary weight loss supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 5634–5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, A.; Saitoh, T.; Tani, K.; Uchigaki, M.; Sugimoto, Y.; Yamada, J.; Nakajima, H.; Ohshiro, H.; Sun, S.; Tanahashi, T. Bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids from Nelumbo nucifera. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 59, 947–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.M.; Sun, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, J.L.; Xiao, M.; Zhu, M.S. Isolation and identification of a tribenzylisoquinoline alkaloid from Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn, a novel potential smooth muscle relaxant. Fitoterapia 2017, 124, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Lian, Z.; Peng, X.; Li, Z.; Zhu, H. Applications of Higenamine in pharmacology and medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 196, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.P.; Tsai, W.J.; Shen, C.C.; Lin, Y.L.; Liao, J.F.; Chen, C.F.; Kuo, Y.C. Inhibition of (S)-armepavine from Nelumbo nucifera on autoimmune disease of MRL/MpJ-lpr/lpr mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 531, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, L.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Feng, J.; Liu, Y. Digital gene expression analysis provides insight into the transcript profile of the genes involved in aporphine alkaloid biosynthesis in lotus (Nelumbo nucifera). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.; Facchini, P.J. Isolation and characterization of reticuline N-methyltransferase involved in biosynthesis of the aporphine alkaloid magnoflorine in opium poppy. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 23416–23427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.; Hagel, J.M.; Facchini, P.J. Isolation and characterization of O-methyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of glaucine in Glaucium flavum. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilari, A.; Franceschini, S.; Bonamore, A.; Arenghi, F.; Botta, B.; Macone, A.; Pasquo, A.; Bellucci, L.; Boffi, A. Structural basis of enzymatic (S)-norcoclaurine biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkner, H.; Schweimer, K.; Matecko, I.; Rosch, P. Conformation, catalytic site, and enzymatic mechanism of the PR10 allergen-related enzyme norcoclaurine synthase. Biochem. J. 2008, 413, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.J.; Facchini, P. Norcoclaurine synthase is a member of the pathogenesis-related 10/Bet v1 protein family. Plant Cell. 2010, 22, 3489–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Lee, E.J.; Chang, L.; Facchini, P.J. Genes encoding norcoclaurine synthase occur as tandem fusions in the Papaveraceae. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lichman, B.R.; Sula, A.; Pesnot, T.; Hailes, H.C.; Ward, J.M.; Keep, N.H. Structural evidence for the dopamine-first mechanism of norcoclaurine synthase. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 5274–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luk, L.Y.; Bunn, S.; Liscombe, D.K.; Facchini, P.J.; Tanner, M.E. Mechanistic studies on norcoclaurine synthase of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis: An enzymatic Pictet-Spengler reaction. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 10153–10161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanani, N.; Facchini, P.J. Purification and characterization of norcoclaurine synthase. The first committed enzyme in benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 33878–33883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanani, N.; Liscombe, D.K.; Facchini, P.J. Molecular cloning and characterization of norcoclaurine synthase, an enzyme catalyzing the first committed step in benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis. Plant J. 2004, 40, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kato, E.; Iwata, R.; Kawabata, J. Synthesis and detailed examination of spectral properties of (S)- and (R)-Higenamine 4′-O-β-d-Glucoside and HPLC analytical conditions to distinguish the diastereomers. Molecules 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Zhao, L.; Fang, T.; Xiong, Y.; Ogutu, C.; Yang, D.; Vimolmangkang, S.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y. Investigation of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthetic pathway and its transcriptional regulation in lotus. Hortic. Res. 2018, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meelaph, T.; Kobtrakul, K.; Chansilpa, N.N.; Han, Y.; Rani, D.; De-Eknamkul, W.; Vimolmangkang, S. Coregulation of biosynthetic genes and transcription factors for aporphine-type alkaloid production in wounded lotus provides insight into the biosynthetic pathway of nuciferine. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 8794–8802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Kang, Y.J.; Park, M.K.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Seo, H.G.; Lee, J.H.; Hye Sook, Y.C.; Shin, J.S.; Lee, H.W.; et al. Enantiomers of higenamine inhibit LPS-induced iNOS in a macrophage cell line and improve the survival of mice with experimental endotoxemia. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2006, 6, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, P.F.; Kutchan, T.M. Molecular cloning and heterologous expression of a cDNA encoding berbamunine synthase, a C-O phenol-coupling cytochrome P450 from the higher plant Berberis stolonifera. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA 1995, 92, 2071–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin, A.Y.; Giustini, C.; Graindorge, M.; Matringe, M.; Dumas, R. Crystal structure of norcoclaurine-6-O-methyltransferase, a key rate-limiting step in the synthesis of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. Plant J. 2016, 87, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrow, S.C.; Hagel, J.M.; Beaudoin, G.A.; Burns, D.C.; Facchini, P.J. Stereochemical inversion of (S)-reticuline by a cytochrome P450 fusion in opium poppy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, S.; Peng, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Cao, R.; Salse, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Xia, Q.; Quan, Z.; et al. Improving Nelumbo nucifera genome assemblies using high-resolution genetic maps and BioNano genome mapping reveals ancient chromosome rearrangements. Plant J. 2018, 94, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Lin, Q.; Yang, M.; Yang, P.; Ming, R.; Yu, Q.; Wang, K. Chromosome nomenclature and cytological characterization of sacred lotus. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2017, 153, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.R.; Schuler, M.A. Cytochrome P450 genes from the sacred lotus genome. Trop. Plant Biol. 2013, 6, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liscombe, D.K.; Louie, G.V.; Noel, J.P. Architectures, mechanisms and molecular evolution of natural product methyltransferases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012, 29, 1238–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.R.; Chen, X.; Lang, D.E.; Ng, K.K.S.; Facchini, P.J. Heterodimeric O-methyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of noscapine in opium poppy. Plant J. 2018, 95, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.R. The cytochrome P450 homepage. Hum. Genom. 2009, 4, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikezawa, N.; Iwasa, K.; Sato, F. Molecular cloning and characterization of CYP80G2, a cytochrome P450 that catalyzes an intramolecular C-C phenol coupling of (S)-reticuline in magnoflorine biosynthesis, from cultured Coptis japonica cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 8810–8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastmalchi, M.; Park, M.R.; Morris, J.S.; Facchini, P.J. Family portraits: The enzymes behind benzylisoquinoline alkaloid diversity. Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurkok, T.; Ozhuner, E.; Parmaksiz, I.; Özcan, S.; Turktas, M.; Ipek, A.; Demirtas, I.; Okay, S.; Unver, T. Functional characterization of 4′OMT and 7OMT genes in BIA biosynthesis. Front Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, T.; Tamura, K.I.; Fujii, N.; Morishige, T.; Sato, F. Overexpression of Coptis japonica norcoclaurine 6-O-methyltransferase overcomes the rate-limiting step in benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in cultured Eschscholzia californica. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007, 48, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.S.; Miller, J.A.C.; Chitty, J.A.; Fist, A.J.; Gerlach, W.L.; Larkin, P.J. Metabolic engineering of morphian alkaloids by over-expression and RNAi suppression of salutaridinol 7-O-acetyltransferase in opium poppy. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2008, 6, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagoz, Y.; Gurkok, T.; Zhang, B.; Unver, T. Manipulating the biosynthesis of bioactive compound alkaloids for next-generation metabolic engineering in opium poppy using CRISP-Cas 9 genome editing technology. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, T.T.T.; Facchini, P.J. Characterization of three O-methyltransferases involved in noscapine biosynthesis in opium poppy. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desgagné-Penix, I.; Facchini, P.J. Systematic silencing of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthetic genes reveals the major route to papaverine in opium poppy. Plant J. 2012, 72, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kato, N.; Dubouzet, E.; Kokabu, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Taniguchi, Y.; Dubouzet, J.G.; Yazaki, K.; Sato, F. Identification of a WRKY protein as a transcriptional regulator of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in Coptis japonica. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007, 48, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Motomura, Y.; Sato, F. CjbHLH1 homologs regulate sanguinarine biosynthesis in Eschscholzia californica cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.J.; Hagel, J.M.; Facchini, P.J. Role of the phloem in the biochemistry and ecophysiology of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid metabolism. Front Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esau, K.; Kosakai, H. Laticifers in Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.: Distribution and structure. Ann. Bot. 1975, 39, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanani, N.; Alcantara, J.; Bourgault, R.; Zulak, K.G.; Facchini, P.J. The role of phloem sieve elements and laticifers in the biosynthesis and accumulation of alkaloids in opium poppy. Plant J. 2006, 47, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Hagel, J.M.; Chang, L.; Tucker, J.E.; Shiigi, S.A.; Yelpaala, Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Estrada, R.; Colbeck, J.; Enquist-Newman, M.; et al. A pathogenesis-related 10 protein catalyzes the final step in thebaine biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Alkaloid | Formula | Enantiomer | Organ | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-BENZYLISOQUINOLINE | |||||

| 1 | Norcoclaurine | C16H17NO3 | (+)-R and (−)-S | L, E | [36,37,38,39] |

| 2 | Coclaurine | C17H19NO3 | (+)-R | L, E, F | [15,37,38] |

| 3 | N-Methylcoclaurine | C18H21NO3 | (−)-R | L, E, F | [15,37,38] |

| 4 | Norarmepavine | C18H21NO3 | (+)-R | F | [15,40] |

| 5 | N-Methylisococlaurine | C18H21NO3 | NS | L, E | [38,41] |

| 6 | 6-Demethyl-4′-O-methyl-N-methylcoclaurine | C18H21NO3 | NS | E | [38] |

| 7 | Armepavine | C19H23NO3 | (−)-R and (+)-S | L, E, S | [15,38,40,42] |

| 8 | 4′-O-Methyl-N-methylcoclaurine | C19H23NO3 | NS | E | [38] |

| 9 | 4′-O-Methylarmepavine | C20H25NO3 | NS | L | [43] |

| 10 | Lotusine | C19H24NO3+ | NS | E | [38] |

| 11 | Isolotusine | C19H24NO3+ | NS | E | [38] |

| APORPHINE | |||||

| 12 | Caaverine | C17H17NO2 | (−)-R | L | [17,40] |

| 13 | Asimilobine | C17H17NO2 | (−)-R | L, F | [15,17,44] |

| 14 | Lirinidine | C18H19NO2 | (−)-R | L, F | [16] |

| 15 | O-Nornuciferine | C18H19NO2 | (−)-R | L, F | [16,17,35] |

| 16 | N-Nornuciferine | C18H19NO2 | (−)-R | L, E, F | [16,17,38] |

| 17 | Nuciferine | C19H21NO2 | (−)-R | L, E, F | [15,17,35,38] |

| 18 | Anonaine | C17H15NO2 | (−)-R | L, F | [17,32] |

| 19 | Roemerine | C18H17NO2 | (−)-R | L, F | [17,18,32,35] |

| 20 | Dehydronuciferine | C19H19NO2 | N/A | L, R | [16,32,41] |

| 21 | Dehydroanonaine | C17H13NO2 | N/A | L | [41] |

| 22 | Dehydroroemerine | C18H15NO2 | N/A | L | [41] |

| 23 | Pronuciferine | C19H21NO3 | (+)-R and (−)-S | L, E, F | [16,38,40,43] |

| 24 | 7-Hydroxydehydronuciferine | C19H19NO3 | N/A | L | [17] |

| 25 | Lysicamine | C18H13NO3 | N/A | L, F | [16] |

| 26 | Liriodenine | C17H9NO3 | N/A | L | [17] |

| BISBENZYLISOQUINOLINE | |||||

| 27 | Nelumboferine | C36H40N2O6 | NS | E, LS | [32,45] |

| 28 | Liensinine | C37H42N2O6 | 1R,1′R | L, E, F, LS | [32,35,44,46] |

| 29 | Isoliensinine | C37H42N2O6 | 1R,1′S | E | [35,46] |

| 30 | Neferine | C38H44N2O6 | 1R,1′S | E, LS | [32,35,46] |

| 31 | 6-Hydroxynorisoliensinine | C36H40N2O6 | NS | E | [38] |

| 32 | N-Norisoliensinine | C36H40N2O6 | NS | E | [38] |

| 33 | Nelumborine | C36H40N2O6 | NS | E | [45] |

| TRIBENZYLISOQUINOLINE | |||||

| 34 | Neoliensinine | C63H70N3O10 | 1R,1′S,1″R | E | [46] |

| Class | Enzyme | Isoforms | Substrate | Product | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pictet-Spenglerase | NCS | NCS1 (KT963033) a | Dopamine 4-HPAA | Norcoclaurine | [34] |

| NCS3 (KT963034) a | |||||

| NCS4 (KT963035) a | |||||

| NCS5 (KU234431) a | |||||

| NCS7 (KU234432) a | |||||

| O-Methyltransferase | 6OMT | 6OMT1 (MG517493) a | Norcoclaurine | Coclaurine | [49,61,62] |

| 6OMT2 (MG517492) a | |||||

| 6OMT3 (MG517491) a | |||||

| 6OMT4 (MG517490) a | |||||

| 7OMT | 7OMT1 (NNU20903) b | Coclaurine | Norarmepavine | [61] | |

| 7OMT2 (NNU04966) b | |||||

| 7OMT3 (NNU09736) b | |||||

| 4′OMT | 4′OMT1 (NNU15801) b | N-Methylcoclaurine | 4′-O-methyl-N-methylcoclaurine | [49] | |

| 4′OMT2 (NNU15809) b | |||||

| 4′OMT3 (NNU24728) b | |||||

| 4′OMT4 (NNU25948) b | |||||

| N-Methyltransferase | CNMT | CNMT1 (MG517494) a | Coclaurine | N-Methylcoclaurine | [49,61,62] |

| CNMT3 (MG517495) a | |||||

| Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase | CYP80A | CYP80A (NNU21373) b | N-Methylcoclaurine | Nelumboferine | [61] |

| CYP80G | CYP80G (NNU21372) b | N-Methylcoclaurine | Lirinidine | [49,61,62] | |

| CYP719A | CYP719A22 (XM010268782) a | Lirinidine | Roemerine | [61,69] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Menéndez-Perdomo, I.M.; Facchini, P.J. Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids Biosynthesis in Sacred Lotus. Molecules 2018, 23, 2899. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23112899

Menéndez-Perdomo IM, Facchini PJ. Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids Biosynthesis in Sacred Lotus. Molecules. 2018; 23(11):2899. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23112899

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenéndez-Perdomo, Ivette M., and Peter J. Facchini. 2018. "Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids Biosynthesis in Sacred Lotus" Molecules 23, no. 11: 2899. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23112899